25 Great Nonfiction Essays You Can Read Online for Free

Alison Doherty

Alison Doherty is a writing teacher and part time assistant professor living in Brooklyn, New York. She has an MFA from The New School in writing for children and teenagers. She loves writing about books on the Internet, listening to audiobooks on the subway, and reading anything with a twisty plot or a happily ever after.

View All posts by Alison Doherty

I love reading books of nonfiction essays and memoirs , but sometimes have a hard time committing to a whole book. This is especially true if I don’t know the author. But reading nonfiction essays online is a quick way to learn which authors you like. Also, reading nonfiction essays can help you learn more about different topics and experiences.

Besides essays on Book Riot, I love looking for essays on The New Yorker , The Atlantic , The Rumpus , and Electric Literature . But there are great nonfiction essays available for free all over the Internet. From contemporary to classic writers and personal essays to researched ones—here are 25 of my favorite nonfiction essays you can read today.

“Beware of Feminist Lite” by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The author of We Should All Be Feminists writes a short essay explaining the danger of believing men and woman are equal only under certain conditions.

“It’s Silly to Be Frightened of Being Dead” by Diana Athill

A 96-year-old woman discusses her shifting attitude towards death from her childhood in the 1920s when death was a taboo subject, to World War 2 until the present day.

“Letter from a Region in my Mind” by James Baldwin

There are many moving and important essays by James Baldwin . This one uses the lens of religion to explore the Black American experience and sexuality. Baldwin describes his move from being a teenage preacher to not believing in god. Then he recounts his meeting with the prominent Nation of Islam member Elijah Muhammad.

“Relations” by Eula Biss

Biss uses the story of a white woman giving birth to a Black baby that was mistakenly implanted during a fertility treatment to explore racial identities and segregation in society as a whole and in her own interracial family.

“Friday Night Lights” by Buzz Bissinger

A comprehensive deep dive into the world of high school football in a small West Texas town.

“The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Coates examines the lingering and continuing affects of slavery on American society and makes a compelling case for the descendants of slaves being offered reparations from the government.

“Why I Write” by Joan Didion

This is one of the most iconic nonfiction essays about writing. Didion describes the reasons she became a writer, her process, and her journey to doing what she loves professionally.

“Go Gentle Into That Good Night” by Roger Ebert

With knowledge of his own death, the famous film critic ponders questions of mortality while also giving readers a pep talk for how to embrace life fully.

“My Mother’s Tongue” by Zavi Kang Engles

In this personal essay, Engles celebrates the close relationship she had with her mother and laments losing her Korean fluency.

“My Life as an Heiress” by Nora Ephron

As she’s writing an important script, Ephron imagines her life as a newly wealthy woman when she finds out an uncle left her an inheritance. But she doesn’t know exactly what that inheritance is.

“My FatheR Spent 30 Years in Prison. Now He’s Out.” by Ashley C. Ford

Ford describes the experience of getting to know her father after he’s been in prison for almost all of her life. Bridging the distance in their knowledge of technology becomes a significant—and at times humorous—step in rebuilding their relationship.

“Bad Feminist” by Roxane Gay

There’s a reason Gay named her bestselling essay collection after this story. It’s a witty, sharp, and relatable look at what it means to call yourself a feminist.

“The Empathy Exams” by Leslie Jamison

Jamison discusses her job as a medical actor helping to train medical students to improve their empathy and uses this frame to tell the story of one winter in college when she had an abortion and heart surgery.

“What I Learned from a Fitting Room Disaster About Clothes and Life” by Scaachi Koul

One woman describes her history with difficult fitting room experiences culminating in one catastrophe that will change the way she hopes to identify herself through clothes.

“Breasts: the Odd Couple” by Una LaMarche

LaMarche examines her changing feelings about her own differently sized breasts.

“How I Broke, and Botched, the Brandon Teena Story” by Donna Minkowitz

A journalist looks back at her own biased reporting on a news story about the sexual assault and murder of a trans man in 1993. Minkowitz examines how ideas of gender and sexuality have changed since she reported the story, along with how her own lesbian identity influenced her opinions about the crime.

“Politics and the English Language” by George Orwell

In this famous essay, Orwell bemoans how politics have corrupted the English language by making it more vague, confusing, and boring.

“Letting Go” by David Sedaris

The famously funny personal essay author , writes about a distinctly unfunny topic of tobacco addiction and his own journey as a smoker. It is (predictably) hilarious.

“Joy” by Zadie Smith

Smith explores the difference between pleasure and joy by closely examining moments of both, including eating a delicious egg sandwich, taking drugs at a concert, and falling in love.

“Mother Tongue” by Amy Tan

Tan tells the story of how her mother’s way of speaking English as an immigrant from China changed the way people viewed her intelligence.

“Consider the Lobster” by David Foster Wallace

The prolific nonfiction essay and fiction writer travels to the Maine Lobster Festival to write a piece for Gourmet Magazine. With his signature footnotes, Wallace turns this experience into a deep exploration on what constitutes consciousness.

“I Am Not Pocahontas” by Elissa Washuta

Washuta looks at her own contemporary Native American identity through the lens of stereotypical depictions from 1990s films.

“Once More to the Lake” by E.B. White

E.B. White didn’t just write books like Charlotte’s Web and The Elements of Style . He also was a brilliant essayist. This nature essay explores the theme of fatherhood against the backdrop of a lake within the forests of Maine.

“Pell-Mell” by Tom Wolfe

The inventor of “new journalism” writes about the creation of an American idea by telling the story of Thomas Jefferson snubbing a European Ambassador.

“The Death of the Moth” by Virginia Woolf

In this nonfiction essay, Wolf describes a moth dying on her window pane. She uses the story as a way to ruminate on the lager theme of the meaning of life and death.

You Might Also Like

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is Nonfiction: Definition and Examples

Sarah Oakley

Table of Contents

What is nonfiction, is nonfiction a genre, what is a nonfiction book example, how prowritingaid can help you write nonfiction.

Nonfiction writing has become one of the most popular genres of books published today. Most nonfiction books are about modern day problems, science, or details of actual events and lives.

If you’re looking for informative writing made up of factual details rather than fiction, nonfiction is a great option. It serves to develop your knowledge about different topics, and it helps you learn about real events.

In this article, we’ll explain what nonfiction is, what to expect from the nonfiction genre, and some examples of nonfiction books.

If you’re considering writing a book, and you can’t decide between fiction or nonfiction , it helps to know exactly what nonfiction is first.

Similarly, if you want to indulge in some self-development, and you decide to read some books, you’ll need to know what to look for in a nonfiction book to ensure you’re reading factual content.

Nonfiction Definition

To define the word nonfiction, we can break it down into two parts. “Non” is a prefix that means the absence of something. “Fiction” means writing that features ideas and elements purely from the author’s imagination.

Therefore, when you put those two definitions together, it suggests nonfiction is the absence of writing that comes from someone’s imagination. To put it in a better way, nonfiction is about facts and evidence rather than imaginary events and characters who don’t exist.

Nonfiction Meaning

As nonfiction writing sounds like the opposite of fiction writing, you might think nonfiction is all true and objective, but that’s not the case. While nonfiction writing contains factual elements, such as real people, concepts, and events, it’s not always objectively true accounts.

A lot of nonfiction writing is opinionated or biased discussions about the subject of the writing.

For example, you might be a football expert, and you want to write a book about the top goal scorers of 2022. Your piece could be objective and discuss exactly who scored the most goals in 2022, or you could add some opinions and discuss who scored the best goals or who performed the best on the pitch.

Opinions make nonfiction books more unique to the author, as it sounds more authentic and human because we all have our own thoughts and feelings about things.

Adding opinions can also make nonfiction books more interesting for readers, as you can be more controversial or use exaggeration to increase reader engagement. Many readers like to pick up books that challenge their thoughts about certain topics.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

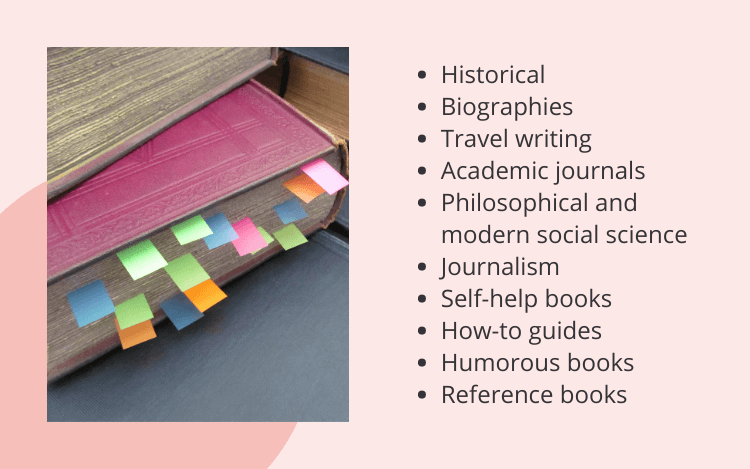

Nonfiction is a genre, but it’s more of an umbrella term for several reference and factual genres. When you’re in the nonfiction section of a bookstore or library, you’ll find the books in categories based on the overall theme or topic of the book.

There are several categories of nonfiction:

Biographies, autobiographies, and memoirs

Travel writing and travel guides

Academic journals

Philosophical and modern social science

Journalism and news media

Self-help books

How-to guides

Humorous books

Reference books

Historical, academic, reference, philosophical, and social science books often focus on factual representations of information about specific subjects, events, and key ideas. The tone of these books is often more formal, though there are some informal examples available.

Biography , memoir, travel writing, humor, and self-help books are creative nonfiction. This means they’re based on true events and stories, but the writer uses a lot more creative freedom to tell stories and pass on information about what they have learned from life.

Readers often criticize journalism and news media for not being objectively truthful when telling people about events. However, almost all journalism is biased or opinionated in one way or another. Therefore, it’s good to read from multiple different sources for your news updates.

If you want to read nonfiction to get an idea of what it’s like, we’ve got several examples of great nonfiction books for you to check out.

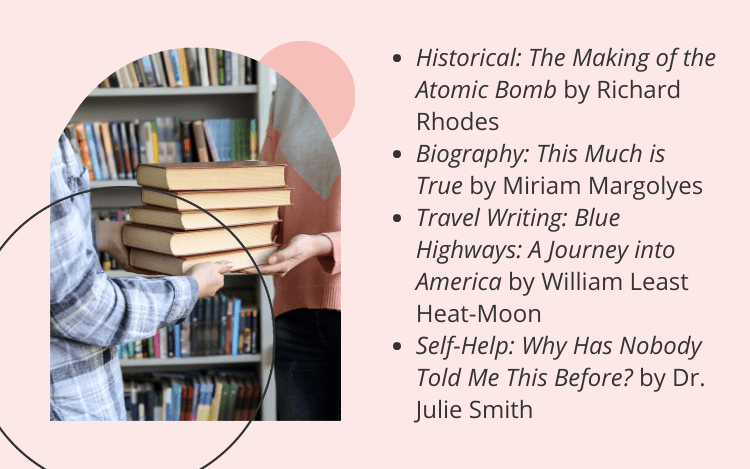

Historical : The Making of the Atomic Bomb by Richard Rhodes

Biography : This Much is True by Miriam Margolyes

Travel Writing : Blue Highways: A Journey into America by William Least Heat-Moon

Philosophical : The Alignment Problem: How Can Machines Learn Human Values? By Brian Christian

Self-Help : Why Has Nobody Told Me This Before? By Dr. Julie Smith

Humor : What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions by Randall Munroe

If you want to write nonfiction, you can use ProWritingAid to ensure you avoid publishing a manuscript full of grammatical errors. Whether you’re looking for a second pair of eyes catching quick fixes as you write, or a full analysis of your manuscript once it’s written, ProWritingAid has you covered.

You can use the Realtime checker to see suggested improvements to your writing as you’re working. If you use the in-tool learning features as well, you’ll see fewer suggestions as you write because it’ll essentially train you to become a better writer.

If you’re more of a full-blown analysis editor, try using the Readability report to see suggestions highlighting where you can improve your writing to ensure more readers can understand what you’re saying. Readability is important if you want to reach more readers who have different levels of reading comprehension.

Another great report you can use for nonfiction writing is the Transitions report. Transitions are the words that show cause and effect within your writing. If you want your reader to follow your points and arguments, you need to include plenty of transitions to improve the flow of your writing.

Now that you know what nonfiction means and how ProWritingAid can help you produce a great nonfiction book, try nonfiction writing , and see how fun it is to share your knowledge and opinions with the world. Just don’t forget to check your work is factual and relevant.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Defining Nonfiction Writing

Andersen Ross / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Etymology : From the Latin, "not" + "shaping, feigning"

Pronunciation : non-FIX-shun

Nonfiction is a blanket term for prose accounts of real people, places, objects, or events. This can serve as an umbrella encompassing everything from Creative Nonfiction and Literary Nonfiction to Advanced Composition , Expository Writing , and Journalism .

Types of nonfiction include articles , autobiographies , biographies , essays , memoirs , nature writing , profiles , reports , sports writing , and travel writing .

Observations

- "I see no reason why the word [ artist ] should always be confined to writers of fiction and poetry while the rest of us are lumped together under that despicable term 'Nonfiction'— as if we were some sort of remainder. I do not feel like a Non-something; I feel quite specific. I wish I could think of a name in place of 'Nonfiction.' In the hope of finding an antonym , I looked up 'Fiction' in Webster and found it defined as opposed to 'Fact, Truth, and Reality.' I thought for a while of adopting FTR, standing for Fact, Truth, and Reality, as my new term." (Barbara Tuchman, "The Historian as Artist," 1966)

- "It's always seemed odd to me that nonfiction is defined, not by what it is , but by what it is not . It is not fiction. But then again, it is also not poetry, or technical writing or libretto. It's like defining classical music as nonjazz ." (Philip Gerard, Creative Nonfiction . Story Press, 1996)

- "Many writers and editors add 'creative' to 'nonfiction' to mollify this sense of being strange and other, and to remind readers that creative nonfiction writers are more than recorders or appliers of reason and objectivity. Certainly, many readers and writers of creative nonfiction recognize that the genre can share many elements of fiction." (Jocelyn Bartkevicius, "The Landscape of Creative Nonfiction," 1999)

- "If nonfiction is where you do your best writing or your best teaching of writing, don't be buffaloed into the idea that it's an inferior species. The only important distinction is between good writing and bad writing." (William Zinsser, On Writing Well , 2006)

- The Common Core State Standards (US) and Nonfiction "One central concern is that the Core reduces how much literature English teachers can teach. Because of its emphasis on analysis of information and reasoning, the Core requires that 50 percent of all reading assignments in elementary schools consist of nonfiction texts . That requirement has sparked outrage that masterpieces by Shakespeare or Steinbeck are being dropped for informational texts like 'Recommended Levels of Insulation' by the Environmental Protection Agency." ("The Common Core Backlash." The Week , June 6, 2014)

- What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- A Look at the Roles Characters Play in Literature

- Are Literature and Fiction the Same?

- A List of Every Nobel Prize Winner in English Literature

- Stream of Consciousness Writing

- John McPhee: His Life and Work

- Third-Person Point of View

- How to Summarize a Plot

- Using Flashback in Writing

- Translation: Definition and Examples

- What Does Critical Reading Really Mean?

- Motifs in Fiction and Nonfiction

- Creative Nonfiction

- literary present (verbs)

Picturing the Personal Essay: A Visual Guide

A design professor from Denmark once drew for me a picture of the creative process, which had been the subject of his doctoral dissertation. “Here,” he said. “This is what it looks like”:

Nothing is wasted though, said the design professor, because every bend in the process is helping you to arrive at your necessary structure. By trying a different angle or creating a composite of past approaches, you get closer and closer to what you intend. You begin to delineate the organic form that will match your content.

The remarkable thing about personal essays, which openly mimic this exploratory process, is that they can be so quirky in their “shape.” No diagram matches the exact form that evolves, and that is because the best essayists resist predictable approaches. They refuse to limit themselves to generic forms, which, like mannequins, can be tricked out in personal clothing. Nevertheless, recognizing a few basic underlying structures may help an essay writer invent a more personal, more unique form. Here, then, are several main options.

Narrative with a lift

Take, for example, Jo Ann Beard’s essay “The Fourth State of Matter.” The narrator, abandoned by her husband, is caring for a dying dog and going to work at a university office to which an angry graduate student has brought a gun. The sequence of scenes matches roughly the unfolding of real events, but there is suspense to pull us along, represented by questions we want answered. In fact, within Beard’s narrative, two sets of questions, correlating to parallel subplots, create a kind of double tension. When the setting is Beard’s house, we wonder, “Will she find a way to let go of the dying dog, not to mention her failing marriage?” And when she’s at work, we find ourselves asking, “What about the guy with the gun? How will he impact her one ‘safe place’?”

One interesting side note: trauma, which is a common source for personal essays, can easily cause an author to get stuck on the sort of plateau Kittredge described. Jo Ann Beard, while clearly wrestling with the immobilizing impact of her own trauma, found a way to keep the reader moving both forward and upward, until the rising tension reached its inevitable climax: the graduate student firing his gun. I have seen less-experienced writers who, by contrast, seem almost to jog in place emotionally, clutching at a kind of post-traumatic scar tissue.

The whorl of reflection

Let’s set aside narrative, though, since it is not the only mode for a personal essay. In fact, most essays are more topical or reflective, which means they don’t move through time in a linear fashion as short stories do.

One of the benefits of such a circling approach is that it seems more organic, just like the mind’s creative process. It also allows for a wider variety of perspectives—illuminating the subject from multiple angles. A classic example would be “Under the Influence,” Scott Russell Sanders’s essay about his alcoholic father. Instead of luring us up the chronological slope of plot, Sanders spirals around his father’s drinking, leading us to a wide range of realizations about alcoholism: how it gets portrayed in films, how it compares to demon-possession in the Bible, how it results in violence in other families, how it raises the author’s need for control, and even how it influences the next generation through his workaholic over-compensation. We don’t read an essay like this out of plot-driven suspense so much as for the pleasure of being surprised, again and again, by new perspective and new insight.

The formal limits of focus

My own theory is that most personal essayists, because of a natural ability to extrapolate, do not struggle to find subjects to write about. Writer’s block is not their problem since their minds overflow with remembered experiences and related ideas. While a fiction writer may need to invent from scratch, adding and adding, the essayist usually needs to do the opposite, deleting and deleting. As a result, nonfiction creativity is best demonstrated by what has been left out. The essay is a figure locked in a too-large-lump of personal experience, and the good essayist chisels away all unnecessary material.

Virginia Woolf’s “Street Haunting” is an odd but useful model. She limits that essay to a single evening walk in London, ostensibly taken to buy a pencil. I suspect Woolf gave herself permission to combine incidents from several walks in London, but no matter. The essay feels “brought together” by the imposed limits of time and place.

As it happens, “Street Haunting” is also an interesting prototype for a kind of essay quite popular today: the segmented essay. Although the work is unified by the frame of a single evening stroll, it can also be seen as a combination of many individual framed moments. If we remove the purpose of the journey—to find a pencil—the essay falls neatly into a set of discrete scenes with related reveries: a daydreaming lady witnessed through a window, a dwarfish woman trying on shoes, an imagined gathering of royalty on the other side of a palace wall, and eventually the arguing of a married couple in the shop where Woolf finally gets her pencil.

Dipping into the well

Our attention to thematic unity brings up one more important dynamic in most personal essays. Not only do we have a horizontal movement through time, but there is also a vertical descent into meaning. As a result, essayists will often pause the forward motion to dip into a thematic well.

In fact, Berry uses several of these loops of reflective commentary, and though they seem to be digressions, temporarily pulling the reader away from the forward flow of the plot, they develop an essential second layer to the essay.

Braided and layered structures

Want an example? Look at Judith Kitchen’s three-page essay “Culloden,” which manages to leap back and forth quite rapidly, from a rain-pelted moor in 18th-century Scotland to 19th-century farms in America to the blasted ruins of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the author’s birthday. The sentences themselves suggest the impressionistic effect that Kitchen is after, being compressed to fragments, rid of the excess verbiage we expect in formal discourse: “Late afternoon. The sky hunkers down, presses, like a lover, against the land. Small sounds. A far sheep, faint barking. . . .” And as the images accumulate, layer upon layer, we begin to feel the author’s fundamental mood, a painful awareness of her own inescapable mortality. We begin to encounter the piece on a visceral level that is more intuitive than rational. Like a poem, in prose.

Coming Full Circle

First of all, endings are related to beginnings. That’s why many essays seem to circle back to where they began. Annie Dillard, in her widely anthologized piece “Living Like Weasels,” opens with a dried-out weasel skull that is attached, like a pendant, to the throat of a living eagle—macabre proof that the weasel was carried aloft to die and be torn apart. Then, at the end of the essay, Dillard alludes to the skull again, stating, “I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you.”

See how deftly Dillard accomplishes this effect simply by positing one last imagined or theoretical possibility—a way of life she hopes to master, that we ourselves might master: “Seize it and let it seize you up aloft even, till your eyes burn out and drop; let your musky flesh fall off in shreds, and let your very bones unhinge and scatter, loosened over fields, over fields and woods, lightly, thoughtless, from any height at all, from as high as eagles.” Yes, the essay has come full circle, echoing the opening image of the weasel’s skull, but it also points away, beyond itself, to something yet to be realized. The ending both closes and opens at the same time.

All diagrams rendered by Claire Bascom. An earlier version of this essay appeared in Volume I, issue 1 of The Essay Review .

This essay is fabulously This essay is fabulously useful! I’ll be showing it to my creative writing students semester after semester, I’m sure. I appreciate the piece’s clarity and use of perfect examples.

I love the succinct diagrams and cited writing examples. Very instructive and useful as A.P. comments above. I also loved that I had read the Woolf journey to buy a pencil–one of my favorite essays because it is such a familiar experience–that of observing people.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundamentals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

What Is Nonfiction? Definition & Famous Examples

What is nonfiction, and why does it matter to know its definition?

Consider this: you want to write a book about your life, but you’re unsure if it will be listed as fiction or nonfiction .

Why would a book about your life be fiction, you ask?

Well, while some authors prefer to base their stories strictly on reality, other writers choose to draw from true events while infusing the story with creative liberties. When people see a book listed as nonfiction, they assume that everything in it actually happened and is completely accurate – to the best of the author’s knowledge.

Conversely, when a book, movie, or series says “based on true events,” there is a lot of room for interpretations, exaggerations, and even completely made-up characters and parts of the story.

Need A Nonfiction Book Outline?

To get clear about this genre, I first ask (and answer) the question, what is nonfiction? Then, I explain how you can confirm a book is nonfiction, list popular subgenres and types of nonfiction books, share three classic characteristics of nonfiction books, and highlight a few famous nonfiction authors. So, are you ready?

This guide answers “what is nonfiction?” and more:

First, what is nonfiction .

A nonfiction book is one based on true events and as factually correct as possible. It presents true information, real events, or documented accounts of people, places, animals, concepts, or phenomena. There is no place for fictional characters or exaggerations in this genre.

But that doesn’t mean it won’t read like fiction. There are plenty of people who have such a fascinating or unbelievable story to tell that it doesn’t feel real. The Prince Harry memoir comes to mind. It has everything that you might find in a fantasy novel – except it really happened. A real-life prince? Yes. War, drama, and family conflict? Yes. A movie star wife? Also yes.

Others about trauma, death, and struggle have less magic to them, but could be equally difficult to believe due to the difficulties encountered by the author. An example here is the Jennette McCurdy memoir , I’m Glad My Mom Died .

There are plenty of other memoir examples , but memoirs are just one answer to, “What is nonfiction?” In reality, it includes a whole host of other subgenres.

How can I tell if a book is nonfiction?

For starters, any nonfiction book should be listed as nonfiction – whether online or in a physical book store. But if you want to be sure the book you have in your hands falls in this category, here’s what you can do:

- Examine the cover. Fiction books often have more artwork on the cover and may include a character or symbolism. Meanwhile, nonfiction book covers are often (though not always), more minimalist. Some may not have any artwork or may include a picture of the author.

- Find clues in the title and subtitle. Nonfiction book titles are often much more literal and descriptive about the subject matter. Exceptions to this are memoir titles, as they might be more interpretive.

- Read the author bio. A nonfiction author bio often leads with the author’s qualifications (a degree or lived experience) and reasons for writing the book, while a fiction author bio might be more personal or speak to other books the author has written.

- Look for a preface and/or table of contents. Most nonfiction books are penned to educate or help the reader. Many of them will have a preface introducing the concept or the author’s background on the subject matter. Similarly, they’ll likely include an easy-to-navigate table of contents, similar to a textbook or educational text.

- Scan the pages for citations or a reference list. Nonfiction books are factual. Therefore, the presented information should be backed up by studies, academic papers, or other reputable sources.

- Read reviews. This is much easier if the book is listed online. But nonfiction book reviews usually use words like “transformation,” “helpful information,” and “life-changing.”

- Consider the style and tone. While any author is free to use any tone in writing , most nonfiction authors default to an educational (even if casual) tone. Memoir authors may be the exception to this one, as most personal accounts are written in the distinct tone and voice of the author.

What types of nonfiction books are there?

When posed with the question, “What is nonfiction?” it’s also worth noting the different subgenres, types of writing, and themes in books that appear in the nonfiction category.

Popular nonfiction book genres include:

- Memoir and autobiography

- Spirituality or faith

- Health and fitness

- Art and photography

- Motivational and inspirational

Each of these sub-genres includes the three characteristics of nonfiction that we’ll discuss in a bit. But before we get there, consider the different types of writing that could also appear in nonfiction:

- Narrative nonfiction

- Creative nonfiction

- Scientific works

- Historical accounts

3 purposes and characteristics of nonfiction

Now you have a strong foundation and can confidently answer the question, “What is nonfiction?” Let’s go deeper. Why do people read nonfiction? What is the purpose of a nonfiction book?

Equally as important as being able to define nonfiction is to be able to describe the characteristics that make a book an effective nonfiction piece.

1. What is nonfiction? Inspiration.

One of the primary characteristics of nonfiction is its inspirational themes. While there are many types of nonfiction, most of them find a way to weave in enough inspiration to help readers want to better themselves and lead a better life.

Whether your book focuses on a personal victory – instilling in readers the idea that “I overcame this and so can you” – or uses data to inspire readers to join the 5 a.m. Club, nonfiction is inspiration, no matter how overt.

2. What is nonfiction? Education.

Educational nonfiction exists as its own sub-genre. However, even outside of strictly educational books, nonfiction includes lessons for readers who desire to self-educate.

Need an example? James Clear’s bestseller, Atomic Habits , stands as a key example of the power nonfiction has in educating readers – while inspiring change.

3. What is nonfiction? Self-discovery.

Some of the bestselling nonfiction today acts as a guide for readers intent on self-reflection. It often uses repetition in writing to portray a theme.

In fact, at a deeper level, answering the question, “What is nonfiction?” often comes down to identifying how a particular book helps readers see parts of themselves they would not otherwise see.

Top nonfiction authors

Let’s finish this long-winded answer to “What is nonfiction?” with some concrete – and a bit famous – examples. What better way to define what a nonfiction book is than to read some of the top books in the genre? Who knows, maybe you’ll learn something along the way!

Elizabeth Gilbert

Readers know Elizabeth Gilbert for her New York Times bestsellers Eat, Pray, Love and Big Magic . She put travel memoirs – and nonfiction books – on the map in a whole new way with the former and continues to write great books to this day. Big Magic is a nonfiction book that focuses on creativity – and does so from a vulnerable perspective.

Fiction writers often create vulnerable characters. However, with nonfiction memoirs, it’s arguably more difficult. Why is this? You, the author, are often the protagonist. Whatever you reveal is likely personal.

What you can learn from her: How to write with appropriate vulnerability to connect with your readers on a more personal level.

Related: Memoir Writing Do’s and Don’ts

James Clear

Another bestselling author, James Clear, focuses on self-development through small, atomic-sized habits in his aptly-named nonfiction book, Atomic Habits. His mindset shift guides readers into self-discovery, and his writing inspires change that lasts. Within the pages of his book, you’ll find top atomic habits quotes to inspire your personal goals and habits.

Now known as one of the leaders in the self-development world, Clear didn’t start at his current success level. His personal journey further proves the results of his message.

What you can learn from him: How to provide small, actionable next steps that lead to large, impactful results.

Related: 14 Books Like Atomic Habits To Read Next

Jennette McCurdy

To say Jennette McCurdy is famous would be a massive understatement. With nine million Instagram followers and a bestselling memoir, her writing style is one to take note of.

I’m Glad My Mom Died is an evocative title that sets readers on a hilarious yet heartbreaking look at Jennette’s life, including deep-seated, personal struggles.

What you can learn from her: Balance humor and heartbreak to communicate your story with the highs and lows associated with great plots.

David Goggins

At times a polarizing figure, David Goggins’ work ethic is no joke. Known for his extreme self-discipline, stringent workout routine, and early mornings, his book, Can’t Hurt Me , has sold four million copies.

What you can learn from him: Don’t shy away from fully communicating your passion, your past as it relates to your writing, and your progress. Combining all three can help your readers in profound ways.

These iconic authors paved, and are paving, a definitive answer to the question, “what is nonfiction?” with their work:

- Svetlana Alexievich

- Frederick Douglass

- Rebecca Skloot

- Mark Twain

- Caroline Fraser

Fraser focuses on America’s beloved Laura Ingalls Wilder. Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel Prize winner is known as a landmark work of oral history. Frederick Douglass’s personal narrative tells horrific stories of overcoming with beautiful prose. Rebecca Skloot shares scientific knowledge in a way that resonates with her readers.

Mark Twain’s adventures are iconic in American history. C.S. Lewis is known for his compelling nonfiction works (as well as his original fiction plots).

These names, and many more, can provide a foundation on which to draw from as you move into ideating your draft. But you might still be asking if nonfiction is the right path for you – and your book.

Should you write a nonfiction book?

Don’t just want to know what nonfiction is but why – and how to write a nonfiction book as well? Well, can you answer any of these questions with a resounding “yes!?”

- Do you live a unique life?

- Have you overcome something life-changing or mindset-altering?

- Do you have a desire to teach a valuable lesson?

- Is there something you know due to your profession, education, or background that could help others?

- Do you want to shift from teaching one-on-one as a service provider to changing multiple people’s lives with the same amount of effort?

- Do you have a business that you want to grow?

- Are you passionate about a specific event or time in history – and want more people to learn about it?

The next time someone asks you, “What is nonfiction?” you can explain that nonfiction encompasses writing based on factual events or data – and then hand them a copy of your own book as an example!

Define nonfiction with your own book

So what is nonfiction? As you can see, it’s a lot of things. Great nonfiction is storytelling grounded on facts, written with purpose, and crafted in a creative way that readers connect with. Excited to craft your own nonfiction narrative but feeling unsure where to start? Fret not! Here are some helpful guides to get you started:

- How to Write a Biography

- How to Write a Book About Christianity

- How to Write a Psychology Book

- How to Write a Self-Help Book

Now it’s your turn to become the protagonist in your own story. Whether you choose to write a memoir or autobiography or want to share lessons learned from a less-personal perspective, it’s your turn to answer the question, “What is nonfiction?”

While many nonfiction books (especially self-help) include data and stats, the stories mentioned above are not simply a collection of data but a framework that ties the following together:

- Inspiration

- Education

- Self-discovery

It’s important to define what is nonfiction as it relates to your specific writing goals . Think about the themes, topics, and characteristics you want to include in your manuscript. Consider how you want your readers to feel during and after reading your book.

Your nonfiction can mix horror and heartbreak, tragedy and triumph, failures and persistence. You can use your expertise to inspire others to health, wellness, and new levels of self-development.

Every writer has a unique perspective to share. Your viewpoint matters, and what you have to say can play a vital role in the trajectory of the nonfiction genre!

Need book writing help ? Reference the free resource below for further guidance!

Elite Author T. Lynette Yankson Teaches Perseverance in Her Children’s Book About a True Story

Children's Book, Non-Fiction

Elite Author Peder Tellefsdal Is On a Mission to Rebrand the Church with His New Book

Non-Fiction

How to Write a Biography: 11 Step Guide + Book Template

Join the community.

Join 100,000 other aspiring authors who receive weekly emails from us to help them reach their author dreams. Get the latest product updates, company news, and special offers delivered right to your inbox.

Instantly enhance your writing in real-time while you type. With LanguageTool

Get started for free

Fiction and Nonfiction: Understanding the Distinctions

Becoming a skilled writer requires knowing the different genres available. Let’s start with the basics: understanding the difference between fiction and nonfiction.

What’s the Difference Between “Fiction” and “Nonfiction”?

Fiction refers to “something created in the imagination .” Therefore, fictional writing is based on events that the author made up rather than real ones. Nonfiction is “writing that revolves around facts , real people, and events that actually occurred .”

Table of Contents

What does “fiction” mean (with examples).

What Does “Nonfiction” Mean? (With Examples)

How To Write Fiction and Nonfiction Masterpieces

An artist discerns subtle brushstrokes that look identical to the average person. They can also recognize hundreds of colors by their names. Similarly, as writers, we must be familiar with distinct types of prose, with the foundation of that knowledge being the ability to differentiate between fiction and nonfiction .

If you’ve ever been uncertain about these terms, you’re in the right place. We’ll help you get a solid grasp of what fiction and nonfiction mean by providing clear explanations and examples.

Let’s dive in!

Fiction is “written work that is invented or created in the mind.” Put differently, the narrative is imaginary and didn’t actually happen. Novels, short stories, epic poems, plays, and comic books are a few types of fiction writing.

Examples of famous fiction literature include:

Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Animal Farm by George Orwell

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

The Harry Potter Series by J.K. Rowling

Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes

Fiction can read like this:

On my way to the city of Bolognaland, I noticed that my water-fueled flying car was running low on energy. So, I stopped by the water station and filled up the tank. There, I saw the most beautiful sunset of green, turquoise, and black. As the sun set below the horizon, the two moons—Luminara and Crescelia—took their place in the night sky.

To the best of our knowledge, every single aspect of the story written above is imaginary, from Bolognaland to the two moons. However, it’s important to note that not every component of a fictional story has to be created out of thin air. For example, someone could come up with a tale about a man who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, which is an actual place in the United States. A fictional story can incorporate many components that are nonfiction .

The word fiction isn’t always used to describe a type of literature; it can also refer to anything false.

Don’t believe anything he says—it’s all fiction !

The legend of the hidden treasure has been passed down in this family for generations, but most of us think it’s fiction .

A main part of my job as a historian is to separate fact from fiction in ancient manuscripts.

“Fictional” vs. “Fictitious”

Fictional and fictitious both relate to things or people that are made up and are often used interchangeably. However, fictional typically describes something that originates from literature , movies , or other forms of storytelling , and fictitious can refer to something that is false and intended to deceive . In other words, it carries more of a negative connotation.

What Does “Nonfiction” Mean?

Nonfiction refers to “literature that is based on facts, real events, and real people.” Nonfiction writers aim to compose everything as truthfully and accurately as possible. However, sometimes authors enhance certain parts to make them more interesting, or they are required to change specific facts, like names, for privacy reasons.

Memoirs, biographies, articles, essays, and even personal journal entries are a few types of nonfiction texts.

A few examples of famous published nonfiction works include:

Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson

When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank

Educated by Tara Westover

The Hidden Life of Trees by Peter Wohlleben

Here’s a piece of nonfiction text:

Elon Musk was born in Pretoria, South Africa on June 28, 1971. His mother is Maye Musk, and his father is Errol Musk. Musk has two siblings, a younger brother named Kimbal and a younger sister named Tosca.

This text is accurate and based on facts; therefore, it is considered nonfiction . But please note that it is not exemplary of nonfiction works—they’re not all boring, rigid, and monotonous. Skilled nonfiction writers weave rhetorical devices, interesting facts, and more to keep readers engaged.

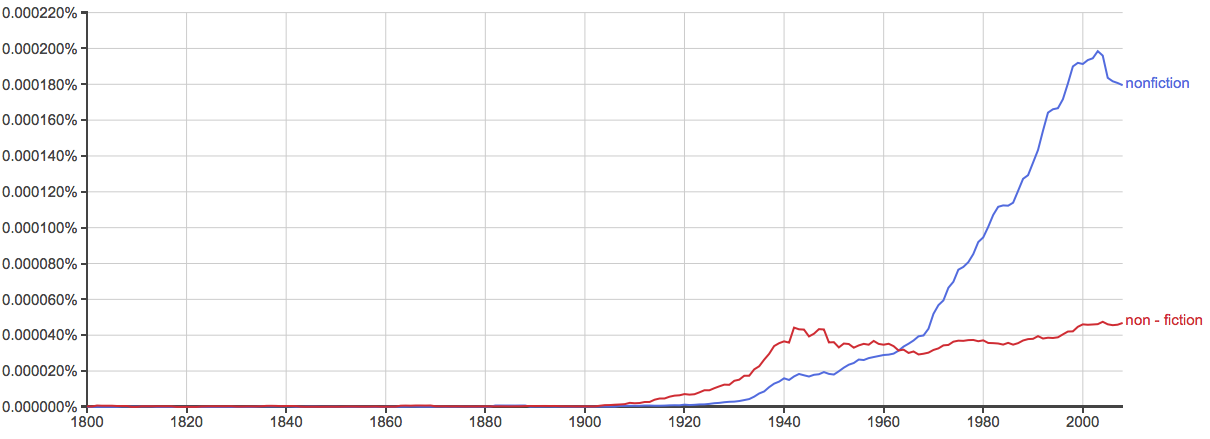

Is it “Nonfiction” or “Non-Fiction”?

This word can be spelled as a hyphenated ( non-fiction ) or non-hyphenated ( nonfiction ) compound word . The spelling depends on which English dialect you’re writing in.

In American English, nonfiction is more commonly used. Both forms are found in British English, but non-fiction is slightly more prevalent.

How To Write Fictional and Nonfictional Masterpieces

We should reiterate that fiction and nonfiction writing can overlap. That means that some fiction includes components of nonfiction and vice versa .

What’s vital to remember is that fiction writing is mostly made up of fabricated stories, whereas nonfiction writing is mostly composed of the truth.

Written masterpieces can be found in all genres, including fiction and nonfiction . When it’s time for you to work on yours, make sure you entrust LanguageTool as your writing assistant. As a multilingual, AI-driven, spell, grammar, and punctuation checker, LanguageTool rids your texts of various types of errors while ensuring you stay productive to reach your goals.

Give it a try today to start writing like the legends!

Unleash the Professional Writer in You With LanguageTool

Go well beyond grammar and spell checking. Impress with clear, precise, and stylistically flawless writing instead.

Works on All Your Favorite Services

- Thunderbird

- Google Docs

- Microsoft Word

- Open Office

- Libre Office

We Value Your Feedback

We’ve made a mistake, forgotten about an important detail, or haven’t managed to get the point across? Let’s help each other to perfect our writing.

Nonfiction Essay

Nonfiction essay generator.

While escaping in an imaginary world sounds very tempting, it is also necessary for an individual to discover more about the events in the real world and real-life stories of various people. The articles you read in newspapers and magazines are some examples of nonfiction texts. Learn more about fact-driven information and hone your essay writing skills while composing a nonfiction essay.

10+ Nonfiction Essay Examples

1. creative nonfiction essay.

2. Narrative Nonfiction Reflective Essay

Size: 608 KB

3. College Nonfiction Essay

Size: 591 KB

4. Non-Fiction Essay Writing

Size: 206 KB

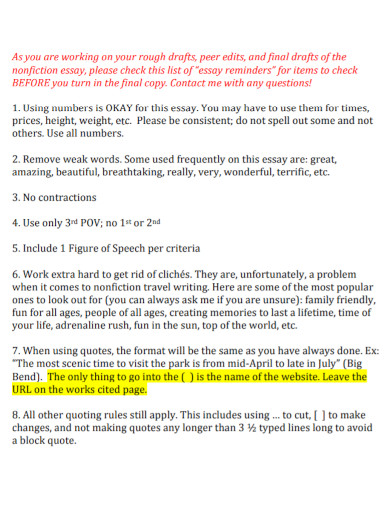

5. Nonfiction Essay Reminders

Size: 45 KB

6. Nonfiction Essay Template

Size: 189 KB

7. Personal Nonfiction Essay

Size: 51 KB

8. Teachers Nonfiction Essay

Size: 172 KB

9. Creative Nonfiction Assignment Essay

Size: 282 KB

10. Nonfiction Descriptive Essay

11. Literary Arts Nonfiction Essay

Size: 93 KB

What Is a Nonfiction Essay?

Nonfiction essay refers to compositions based on real-life situations and events. In addition, it also includes essays based on one’s opinion and perception. There are different purposes for writing this type of essay. Various purposes use different approaches and even sometimes follow varying formats. Educational and informative essays are some examples of a nonfiction composition.

How to Compose a Compelling Nonfiction Essay

When you talk about creative writing, it is not all about creating fictional stories. It also involves providing a thought-provoking narrative and description of a particular subject. The quality of writing always depends on how the writers present their topic. That said, keep your readers engaged by writing an impressive nonfiction paper.

1. Know Your Purpose

Before you start your essay, you should first determine the message you want to deliver to your readers. In addition, you should also consider what emotions you want to bring out from them. List your objectives beforehand. Goal-setting will provide you an idea of the direction you should take, as well as the style you should employ in writing about your topic on your essay paper.

2. Devise an Outline

Now that you have a target to aim for, it is time to decide on the ideas you want to discuss in each paragraph. To do this, you can utilize a blank outline template. Also, prepare an essay plan detailing the structure and the flow of the message of your essay. Ensure to keep your ideas relevant and timely.

3. Generate Your Thesis Statement

One of the most crucial parts of your introduction is your thesis statement . This sentence will give the readers an overview of what to expect from the whole document. Aside from that, this statement will also present the main idea of the essay content. Remember to keep it brief and concise.

4. Use the Appropriate Language

Depending on the results of your assessment in the first step, you should tailor your language accordingly. If you want to describe something, use descriptive language. If you aim to persuade your readers, you should ascertain to use persuasive words. This step is essential to remember for the writers because it has a considerable impact on achieving your goals.

What are the various types of nonfiction articles?

In creatively writing nonfiction essays, you can choose from various types. Depending on your topic, you can write a persuasive essay , narrative essay, biographies, and even memoirs. In addition, you can also find nonfiction essay writing in academic texts, instruction manuals, and even academic reports . Even if most novels are fiction stories, there are also several nonfictions in this genre.

Why is writing nonfiction essays necessary?

Schools and universities use nonfiction essays as an instrument to train and enhance their students’ skills in writing. The reason for this is it will help them learn how to structure paragraphs and also learn various skills. In addition, this academic essay can also be a tool for the teachers to analyze how the minds of their students digest situations.

How can I write about a nonfiction topic?

A helpful tip before crafting a nonfiction essay is to explore several kinds of this type of writing. Choose the approach and the topic where you are knowledgeable. Now that you have your lesson topic, the next step is to perform intensive research. The important part is to choose a style on how to craft your story.

Each of us also has a story to tell. People incorporate nonfiction writing into their everyday lives. Your daily journal or the letters you send your friends all belong under this category of composition. Writing nonfiction essays are a crucial outlet for people to express their emotions and personal beliefs. We all have opinions on different events. Practice writing nonfiction articles and persuade, entertain, and influence other people.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write about the influence of technology on society in your Nonfiction Essay.

Discuss the importance of environmental conservation in your Nonfiction Essay.

$ 645.00 Original price was: $645.00. $ 550.00 Current price is: $550.00.

Open to All Text-Based

$ 645.00 Original price was: $645.00. $ 550.00 Current price is: $550.00. Enroll Now

Write authentic, well-crafted personal essays in this creative nonfiction course.

If you have a story to tell, if you’re fairly confessional and believe that truth is stranger than fiction, then the creative nonfiction, personal essay writing class is for you.

Creative nonfiction and personal essay are powerhouses in the story-telling genre. They’re the volcanic marriage of real life and literary technique, and a chance to deliver our stories with sass, color and voice. By using a variety of techniques such as dialogue, scene, detail and narrative, creative non-fiction and personal essay breathe new life into the ordinary telling of our tales.

Anything is fodder for creative nonfiction; the fight you had with the supermarket check-out person, the time your brother ran you over with his bike, your first real kiss and the lessons you learned about yourself when you stopped to give change to the corner panhandler. By delving into our experiences we squeeze the marrow from our lives and explore our emotional territory, sharing and making meaning out of the ordinary events in our lives.

The ten-week class will focus on finding your voice and locating the heart of your story, as well as finding creative ways to tell these stories, edit what we have, and familiarize ourselves with non-fiction markets. There will be a weekly writing assignment, a chance to post each week and get in-depth, detailed feedback from your peers as well as feedback on five of your stories from Gretchen.

Gretchen was wonderful—positive, understanding, and helpful. She clearly put a lot of time into reading and responding to our work, and I am so thankful for that! —Kathryn Martinak

Introduction to Creative Nonfiction and Personal Writing: Course Syllabus

Each week a new writing lesson is posted and students are given a couple of assignment options as well as a deadline to turn a piece in each week. Writing lessons cover the territory of personal essay with an emphasis on voice, detail, scene, dialogue and resolve.

What is creative nonfiction and the personal essay? Personal essay is about uncovering the truth and telling our stories in our real voices. Creative Nonfiction uses elements of fiction in the telling of a true story. We use narrative combined with live voice to make the writing more melodic, more alive and more accessible.

Beginning our stories. What are we obsessed by and deeply interested in? What are the stories we must tell? Using free writing to unearth raw, unedited material and honing with diversity, melody and voice.

Week Three:

Using memories and images that burn to be told. Using the material from our lives, from our childhood to jump start story and delve in deeply.

Re-working our assignments.

Week Five:

The stories we’re afraid to tell. Writing as liberation. What aren’t we writing about? Using the hardest parts of our lives as material for story because that’s where the energy is. When we write from these places our stories come alive because we’re writing from an edge.

Truth or Fiction? How creative can the personal essay be? How much can we bend the truth? Where do the boundaries blur?

Week Seven:

week eight:.

Speaking to the dead. Who lingers in our lives and what kind of power do they hold for us? Choosing friends or relatives to write about, using their stories to tell our larger stories.

Week Nine

Critiquing the personal essay. How can we help each other tell the truth better? Setting a stage: what stays and what goes? Using the elements that are intrinsic to the telling of the story.

To market to market. Where to sell our work? Ideas and suggestions for where the writers can send their work.

Why Take a Creative Nonfiction and Personal Essay Course with Writers.com?

- We welcome writers of all backgrounds and experience levels, and we are here for one reason: to support you on your writing journey.

- Small groups keep our online writing classes lively and intimate.

- Work through your weekly written lectures, course materials, and writing assignments at your own pace.

- Share and discuss your work with classmates in a supportive class environment.

- Award-winning instructor Gretchen Clark will offer you direct, personal feedback and suggestions on every assignment you submit.

Dive into creative nonfiction and the craft of the personal essay. Reserve your spot today!

Student feedback for gretchen clark:.

Definitely very happy with class content. Gretchen's critiques are so, so helpful. I liked the way Gretchen set up the class so that we were able to choose from many options for our assignments. We could revise an essay or write a new one. As a teacher, Gretchen is like chocolate cake with two scoops of vanilla ice cream. Can't get enough of her. I would take any class Gretchen offered. Caroline Commins

Gretchen was wonderful—positive, understanding, and helpful without being negative or overly critical. Her comments were insightful and extremely helpful to me. She clearly put a lot of time into reading and responding to our work, and I am SO thankful for that! Kathryn Martinak

This course helped me expand my understanding of what an essay can be, and encouraged me to push myself to try different forms of expression. I learned a lot from my fellow students and the instructor and received excellent feedback on my writing. I learned so much from Gretchen's lectures as well as from her comments, not only on my writing but on my fellow students' writings as well. Elizabeth Speziale

Gretchen was great. I have taken over a dozen online writing courses and this one was almost calming. Instead of feeling like I 'had' to submit work for critique, I not only wanted to, but I was anxious to read the other writers' work. Barbara Reidmiller

Gretchen seems to have a way of seeing things in my writing that I overlook; a series of details, a recurring theme, an underlying emotion I have yet to discover within myself. Her critiques are always thoughtful and thought provoking. She takes the time to read and respond carefully, challenging ideas and questioning my writing while encouraging and offering support. When I was looking for more personal and in-depth editorial critique, it was Writers.com and Gretchen that I turned to. Having taken the Personal Essay class, I knew that she would grant me the time and attention that I was seeking. She seems to have unlimited patience to answer questions and hash out ideas. Working one-on-one with her has provided me with a forum and a conversation about my writing. She is an invaluable teacher and editor.

I learned a lot and had fun doing it. We were encouraged to think and write outside the box. It made me more creative. Loved the experience. Svetlana Dietz

Gretchen has great ideas and gives coaching feedback as well as praise. It was exciting to learn about new forms in essay writing and how the form can help carry the story. The group of writers was helpful and positive in providing feedback to each others; I really enjoyed the experience of the community. Karen McCall

I was recently offered my own bi-monthly column in Blue Water Sailing magazine. Writers.com and private time working with Gretchen has certainly contributed to my work improving enough to be given that opportunity. Heather Francis, yachtkate.com

Gretchen was extremely diligent with her feedback and it felt like nothing I wrote went unnoticed. She took the pains to respond equally diligently even with the re-posted material. Her feedback made me want to write more. Mannu Kohli

I thought Gretchen was great. Despite having a lot of people in the class, I always felt that she gave full attention to her feedback on my submissions. She was always quite responsive to questions I had. I really liked her lectures and her suggested materials, I found all of those quite helpful. Allison Allen

I loved this course. Gretchen provided me with really helpful feedback and I appreciate how open she was to discussing the works in progress. I wrote ten pieces I want to keep working with and submit to journals, and want to keep playing with the form. I definitely got my money's worth and am happy with the progress I made in the course overall as a writer. Nicole Breit

Do you have a couple hours? Because that is how long it would take me to sing Gretchen's praises. Every piece she has helped me with, let's make that six, has been accepted for publication. All told, actually, I've received 11 acceptances within a relatively short time span for a writer who has just recently begun to submit her work. ... It isn't just that Gretchen is a gifted writer and teacher/editor, she possesses unusual insight. She reads with many eyes, ears, and hearts and on many different levels. She is present to the reading like a psychoanalyst is present to her patient's free associations: unbiased, unattached, letting herself be moved or struck by anything and everything. ... And she is patient and kind and even when her suggestions maddened me because they forced me to think and feel myself more deeply into my story, she was, 98% of the time, right on. ... What more can I say. I just love working with Gretchen! Pat Heim

Though Gretchen included specific assignments with each week's lecture...they were given to us as suggestions and for inspiration, but we were always free to go off on our own and write whatever caught our imaginations that week. I was also very pleasantly surprised at the high level of talent among my classmates in this course. ... Your classes allow every student to write and post something each week, not simply once or twice during the course, as other classes do. Elaine Kehoe

I thought the lectures were thoughtful and inspiring and I liked that the assignments were flexible in that I could write about anything that I wanted, but Gretchen gave us prompts for if we needed some ideas. I also liked that she provided some optional readings and referenced other books on writing, I ended up doing a lot of outside reading which was very helpful. I did feel like I learned a lot..... Gretchen was excellent. Her positive tone was just the thing to keep students in the class encouraged and motivated. She was also very willing to answer any questions students had and seemed to tailor her critique to what students were asking for, which was wonderful. Overall I felt that she was approachable and was there if I wanted to ask anything. McKenzie Long

I've taken several other on-line writing classes with other schools and this unique approach was the most interesting and challenging of all. I thought the teachers were the freshest and most thorough in the time they put into their critiques. I totally enjoyed the class. I would do something unique with these teachers again. Eve Bandler

I was very happy with both the class content and the teacher. Gretchen’s comments on my essays were insightful; she offered suggestions that I would not have thought of on my own. This was my first online writing class, and I will take another. Thank you so much! Kim Baumgaertel

Gretchen's writing and her lessons are superb and she's a great teacher. I learned a ton from her. I had never heard of the lyric essay before. Gretchen gave me a thorough understanding of it - and lots of practice. Bonnie Gold

Gretchen was great, and always available for questions/clarification. I am definitely driven by challenge, and felt that Gretchen has a good way of keeping you on your toes and helping you to consistently improve. Lessons were inspiring and assignments perfect for challenging the creative side of the brain. An advanced lyric class would be awesome! I would recommend the class to anyone interested in writing. I have signed up for several classes through November. Jenifer Patureau

I loved the class. The Lyric Essay is/was/and shall continue to be a favorte of mine now that I've taken this class. The freedom to manipulate material in new ways, soak words with lyric structure, really came through. Feedback was personal and always offered ways to take a piece to another level. Rewrites were encouraged and feedback was prompt and insighful. Keep those new classes coming so I can continue to write on your site for many years to come. Joanna Johns

This course is terrific. The lessons are creative and inspiring--just look at the lecture titles! Gretchen is smart, kind, and encouraging. Her critiques are full of insight and ideas for taking the writer a step or many steps further. I keep recommending Writers.com when I talk w/ friends. I'll be back for another class. Marge Osborn

Creative, inspiring, motivating, delightful, fun. <Gretchen's> lessons were written with so much imagination and creative juice. It just made you rub your hands together and want to dive in. She was encouraging as well. I have considered taking *this* class again! Tatyana Sussex

Gretchen's class was really great!The Lyric Essay was one of the best courses I've taken from Writers.com. I would like to take a "Lyric Essay 2" course. Caroline Commins

The class was wonderful. Couldn't have had better teachers. Wonderful about letting us veer in our own directions at times. They provided a very nurturing environment for everyone. ... Their comments were very helpful and clearly they know their stuff. ... I would absolutely take another class from either instructor. I can't give them a glowing enough review. ... This is the way you dream a class will work. David Ladd

This was my first online course, and I'm very glad I took it. I feel that the tuition was money well-spent and I emerge from this experience wiser about the subject and very much encouraged to continue my writing using techniques I learned in class. Jean Dutton

“Gretchen was wonderful—positive, understanding, and helpful without being negative or overly critical. Her comments were insightful and extremely helpful to me. She clearly put a lot of time into reading and responding to our work, and I am SO thankful for that!” —Kathryn Martinak

About Gretchen Clark

Gretchen Clark has been a freelancer for an online naming company and a creative arts mentor for at-risk teens. Her essay Pink Chrysanthemum was nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Her work has been published in The Boston Globe, Hamilton Stone Review, 94 Creations, Writer Advice, Literary Mama , Hip Mama , Flashquake , Blood Lotus , Foliate Oak , Skirt! , Word Riot , Quiet Mountain Essays , 34th Parallel , New York Family Magazine , Pithead Chapel , Switchback , Underwired , Toasted Cheese , Celia’s Roundtrip , Brevity , River Teeth , Flashquake , Tiny Lights , Ray's Road Review , Cleaver Magazine, Hippocampus , The MacGuffin, Awakenings Review, and Nailpolish Stories, among others.

Gretchen's Courses

Long Story Short: Compressing Life into Meaningful Micro Memoirs Creative Nonfiction and the Personal Essay The Lyric Essay Block Buster: Turbocharge Your Creativity with Breakneck Writing

- Name * First Last

- Classes You're Interested In

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Reality and imagination

- Author presence

- The descriptive mode

- Expository and argumentative modes

- Modern origins

- Journalism and provocation

- Entertainment

- Philosophy and politics

- Philosophers and thinkers

- Russian essayists

- American and French writers

- Theological writers

- Changing interpretations

- Modern times

- Aphorisms and sketches

- Travel and epistolary literature

- Personal literature

nonfictional prose

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Table Of Contents

nonfictional prose , any literary work that is based mainly on fact, even though it may contain fictional elements. Examples are the essay and biography.

Defining nonfictional prose literature is an immensely challenging task. This type of literature differs from bald statements of fact, such as those recorded in an old chronicle or inserted in a business letter or in an impersonal message of mere information. As used in a broad sense, the term nonfictional prose literature here designates writing intended to instruct (but does not include highly scientific and erudite writings in which no aesthetic concern is evinced), to persuade, to convert, or to convey experience or reality through “factual” or spiritual revelation. Separate articles cover biography and literary criticism .

Nonfictional prose genres cover an almost infinite variety of themes, and they assume many shapes. In quantitative terms, if such could ever be valid in such nonmeasurable matters, they probably include more than half of all that has been written in countries having a literature of their own. Nonfictional prose genres have flourished in nearly all countries with advanced literatures. The genres include political and polemical writings, biographical and autobiographical literature, religious writings, and philosophical, and moral or religious writings.

After the Renaissance, from the 16th century onward in Europe, a personal manner of writing grew in importance. The author strove for more or less disguised self-revelation and introspective analysis, often in the form of letters, private diaries, and confessions. Also of increasing importance were aphorisms after the style of the ancient Roman philosophers Seneca and Epictetus, imaginary dialogues , and historical narratives, and later, journalistic articles and extremely diverse essays. From the 19th century, writers in Romance and Slavic languages especially, and to a far lesser extent British and American writers, developed the attitude that a literature is most truly modern when it acquires a marked degree of self-awareness and obstinately reflects on its purpose and technique. Such writers were not content with imaginative creation alone: they also explained their work and defined their method in prefaces, reflections, essays, self-portraits, and critical articles. The 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire asserted that no great poet could ever quite resist the temptation to become also a critic : a critic of others and of himself. Indeed, most modern writers, in lands other than the United States , whether they be poets, novelists, or dramatists, have composed more nonfictional prose than poetry, fiction , or drama. In the instances of such monumental figures of 20th-century literature as the poets Ezra Pound , T.S. Eliot , and William Butler Yeats , or the novelists Thomas Mann and André Gide , that part of their output may well be considered by posterity to be equal in importance to their more imaginative writing.

It is virtually impossible to attempt a unitary characterization of nonfictional prose. The concern that any definition is a limitation, and perhaps an exclusion of the essential, is nowhere more apposite than to this inordinately vast and variegated literature. Ever since the ancient Greek and Roman philosophers devised literary genres , some critics have found it convenient to arrange literary production into kinds or to refer it to modes.

Obviously, a realm as boundless and diverse as nonfictional prose literature cannot be characterized as having any unity of intent, of technique, or of style. It can be defined, very loosely, only by what it is not. Many exceptions, in such a mass of writings, can always be brought up to contradict any rule or generalization. No prescriptive treatment is acceptable for the writing of essays, of aphorisms, of literary journalism , of polemical controversy, of travel literature, of memoirs and intimate diaries. No norms are recognized to determine whether a dialogue , a confession, a piece of religious or of scientific writing, is excellent, mediocre , or outright bad, and each author has to be relished, and appraised, chiefly in his own right. “The only technique,” the English critic F.R. Leavis wrote in 1957, “is that which compels words to express an intensively personal way of feeling.” Intensity is probably useful as a standard; yet it is a variable, and often elusive , quality, possessed by polemicists and by ardent essayists to a greater extent than by others who are equally great. “Loving, and taking the liberties of a lover” was Virginia Woolf ’s characterization of the 19th-century critic William Hazlitt ’s style: it instilled passion into his critical essays. But other equally significant English essayists of the same century, such as Charles Lamb or Walter Pater , or the French critic Hippolyte Taine , under an impassive mask, loved too, but differently. Still other nonfictional writers have been detached, seemingly aloof, or, like the 17th-century French epigrammatist La Rochefoucauld, sarcastic. Their intensity is of another sort.

Prose that is nonfictional is generally supposed to cling to reality more closely than that which invents stories, or frames imaginary plots. Calling it “realistic,” however, would be a gross distortion. Since nonfictional prose does not stress inventiveness of themes and of characters independent of the author’s self, it appears in the eyes of some moderns to be inferior to works of imagination. In the middle of the 20th century an immensely high evaluation was placed on the imagination, and the adjective “imaginative” became a grossly abused cliché. Many modern novels and plays, however, were woefully deficient in imaginative force, and the word may have been bandied about so much out of a desire for what was least possessed. Many readers are engrossed by travel books, by descriptions of exotic animal life, by essays on the psychology of other nations, by Rilke’s notebooks or by Samuel Pepys’s diary far more than by poetry or by novels that fail to impose any suspension of disbelief. There is much truth in Oscar Wilde ’s remark that “the highest criticism is more creative than creation and the primary aim of the critic is to see the object as in itself it really is not.” A good deal of imagination has gone not only into criticism but also into the writing of history , of essays, of travel books, and even of the biographies or the confessions that purport to be true to life as it really happened, as it was really experienced.

The imagination at work in nonfictional prose, however, would hardly deserve the august name of “primary imagination” reserved by the 19th-century English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge to creators who come close to possessing semidivine powers. Rather, imagination is displayed in nonfictional prose in the fanciful invention of decorative details, in digressions practiced as an art and assuming a character of pleasant nonchalance, in establishing a familiar contact with the reader through wit and humour. The variety of themes that may be touched upon in that prose is almost infinite. The treatment of issues may be ponderously didactic and still belong within the literary domain. For centuries, in many nations, in Asiatic languages, in medieval Latin, in the writings of the humanists of the Renaissance, and in those of the Enlightenment, a considerable part of literature has been didactic . The concept of art for art’s sake is a late and rather artificial development in the history of culture , and it did not reign supreme even in the few countries in which it was expounded in the 19th century. The ease with which digressions may be inserted in that type of prose affords nonfictional literature a freedom denied to writing falling within other genres. The drawback of such a nondescript literature lies in judging it against any standard of perfection, since perfection implies some conformity with implicit rules and the presence, however vague, of standards such as have been formulated for comedy, tragedy, the ode, the short story and even (in this case, more honoured in the breach than the observance) the novel . The compensating grace is that in much nonfictional literature that repudiates or ignores structure the reader is often delighted with an air of ease and of nonchalance and with that rarest of all virtues in the art of writing: naturalness.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Finding Your Footing: Sub-genres in Creative Nonfiction

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.