Understanding Journal Publication Fees: A Compact Guide

Table of contents.

As someone who works on academic publishing, I often get a popular question, especially from young and aspiring researchers:

The article discusses the cost of publishing in an academic journal, delving into journal publishing models, revenue generation methods of publishers, and why some publishers charge high journal publication fees that deter authors from submitting.

Introduction to Journal Publishing

Academic journal publishing is an essential part of the scholarly communication process. Its primary purpose is disseminating research findings, ideas, and theories to the global community of scholars, researchers, and practitioners.

By publishing their work in academic journals, authors contribute to the existing body of knowledge in their respective fields, stimulate further research, and advance human understanding.

A publisher running a scholarly journal needs to cover operation costs. These costs cover system maintenance (manuscript management system), archiving host, editorial services, editorial remuneration, salary, bills, etc. Institutional academic publishers may get (some) funding, whereas commercial publishers need to fork money to cover the overhead.

The total cost can vary significantly between journals and depending on the chosen publishing model. Where the journal publishing fees are concerned, this financial aspect of journal publishing can influence an author’s decision on where to submit their work.

When considering journal publication fees and cost, it’s crucial to understand its importance, purpose, and associated costs. These costs enable journals to maintain high editorial standards, manage the peer review process, and ensure the work’s accessibility to readers worldwide.

While these costs may sometimes seem high, they’re integral to ensuring the quality, integrity, and accessibility of published research. Therefore, it’s essential for authors to factor them into their publishing decisions.

Understanding Journal Publishing Models

Delving into the world of journal publishing, you’ll encounter two primary models: traditional and open access. Remember that we are probably talking about more than 30,000 academic journals worldwide.

Traditional Publishing Model

The traditional publishing model, which has existed for centuries, operates on a subscription-based system. In this setup, readers or their institutions pay a fee (subscription) to access the content of the journals. The subscription mechanism has been the primary publishing model, but the number continues declining as many have adopted the open access model.

The revenue from these subscriptions covers production costs, peer review management, and distribution. Authors may or may not be charged to publish in these types of journals, but even when they are, the fees are generally lower than those of open access journals.

Open Access Publishing Model

However, there is a catch.

In between the traditional subscription and open access models, there is the hybrid model, in which a journal offers both options.

Impact on Journal Publication Fees

The choice between traditional and open access models fundamentally influences the cost of publishing. As mentioned earlier, traditional publishing often incurs fewer upfront costs for the authors as reader subscriptions primarily cover the expenses.

Ultimately, the decision of where to publish—and thus how much to pay—lies in the hands of researchers and their institutions. It’s a balancing act between affordability, academic recognition, and the desire for research to reach as broad an audience as possible.

Who Do Publishers Incur Journal Publication Fees?

The cost of publishing a research paper often raises eyebrows, especially among first-time authors. You might ask, “Why do I have to pay to share my hard-earned knowledge with others?” The answer lies in the intricate process that your manuscript goes through before it gets published. This process involves several quality control steps, all meticulously managed by the journal.

Peer Review and Editorial Services

The cornerstone of academic publishing is the peer review process. It ensures that the research being circulated is high quality, robust, and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. Organizing a thorough, unbiased peer review is no small task. Journals must engage experts in the relevant field, often multiple, and manage their feedback efficiently to maintain the integrity of the review process.

In addition to peer review, there are other editorial services like copy-editing, proofreading and typesetting. These processes help refine the language, correct errors, and format the manuscript as per the journal’s guidelines. The outcome is a polished, professional-looking article that reflects well on the author and the journal.

System Management and Digital Hosting

Beyond editorial work , journals also shoulder the responsibility of maintaining a stable digital platform for hosting published articles. This includes developing and updating the online submission system, managing the website, and ensuring 24/7 access to their digital archives. These technical aspects require significant ongoing investment.

Maintaining Quality and Integrity

All these processes collectively play a pivotal role in maintaining the quality and integrity of the published work. By paying the publishing fee, you’re essentially contributing to this meticulous system designed to uphold the highest standards of academic integrity. It’s an assurance that experts are scrutinizing your work, presented professionally, and hosted on a reliable platform.

While the cost may seem daunting initially, consider it an investment towards ensuring that your research reaches your community in the best possible manner. It’s about valuing the rigorous process that safeguards the reputation of scholarly research.

Decoding the Journal Publication Fee Structure

Detailed breakdown of typical journal publishing fees.

Firstly, there is the cost of handling and processing the manuscript. This involves initial assessment, coordinating the peer review process, and editing the manuscript to meet the journal’s guidelines. These processes require skilled professionals who must be paid for their time and expertise.

A reputable journal also uses a reliable manuscript management system from a third party. This also incurs additional costs. When I was handling the journal department, maintaining the manuscript management system incurred one of the highest costs.

Thirdly, there’s the cost of dissemination and archiving. The final article must be hosted on a website, distributed to various databases, and often printed and shipped to libraries or individual subscribers. Plus, the published article needs to be stored and made accessible indefinitely, which also incurs ongoing costs.

Why Some Publishers Charge High Journal Publication Fees to Publish

The fees charged by different journals can vary widely. Some journals charge high publishing fees because they offer more services or higher quality services. For example, they might employ more experienced editors, have more rigorous peer review processes, or provide more extensive marketing and distribution of published articles.

Furthermore, the prestige of a journal can also play a role in its pricing. Publishing in a highly respected journal can significantly increase a researcher’s reputation and career prospects so that these journals can afford higher fees.

It’s also worth noting that open access journals generally charge higher journal publishing fees than traditional subscription-based journals, as they don’t generate revenue from subscriptions or paywalls. We’ll explore this further in the next section.

Open Access Journal Fees

Understanding open access journal publication fees.

The fees or the amount required to publish a paper in open access journals vary widely. Typically, these fees, known as Article Processing Charges (APCs), range from $100-$900 (lower tier), $1000-$5,000 (mid-tier) and over $6,000 (higher tier).

APCs cover the costs of peer review, editorial work, online hosting, and archiving. Additionally, some journals levy charges for supplementary materials, figures, or color pages. It’s important for authors to thoroughly investigate these charges before submitting them to an open access journal.

The Pros and Cons of Open Access Fees

This can particularly appeal to researchers working on time-sensitive or highly relevant topics. Moreover, some studies have suggested that open access articles are more likely to be cited, which could boost your academic profile.

However, the high APCs can present a significant barrier to some researchers, particularly those without institutional support or access to funding. This raises concerns about the accessibility and equity of open access publishing.

Considering these benefits and drawbacks, the decision to publish in an open access journal ultimately depends on your circumstances and research goals. When making this choice, it’s crucial to consider the immediate financial cost and the potential long-term impacts on your research visibility and reputation.

Strategies to Manage Journal Publication Fees

As an academic researcher, you might be troubled by the steep costs of publishing your findings in scholarly journals. But don’t worry. There are several ways through which these costs can be managed effectively. This section will provide practical tips and advice to help you navigate the financial aspects of journal publishing.

Tips for Authors to Afford Publication Costs

Besides grants, many publishers offer waivers or discounts on journal publication fees. These waivers are typically need-based and may be offered to researchers from low-income countries or those experiencing financial hardship. It’s always a good idea to check the journal’s policy on fee waivers before submission.

Finally, while it might not sound like the most glamorous option, choosing lower-cost journals for publication is also a viable strategy. Many reputable publishers charge reasonable journal publication fees without compromising the quality of peer review or exposure.

Balance Between Journal Publication Fees and Prestige

Remember, the main goal of publishing research is to contribute to your field and boost your academic reputation. Hence, the prestige of the journal should also be taken into account.

Publishing in a prestigious journal ensures a wider audience for your work and adds weight to your academic portfolio. Therefore, it’s essential to strike a balance between cost and prestige. If a prestigious academic publisher charges higher journal publication fees, consider it an investment in your academic career and look for ways to secure funding or waivers.

Conclusion: Making Informed Decisions about Journal Publication Fees

As we reach the conclusion of this enlightening journey through the intricacies of journal publication fees, let’s recap the essential insights.

First, we delved into the world of journal publishing models, distinguishing between traditional and open access models, both of which impact the journal publication fees differently.

These services play an instrumental role in maintaining the quality and integrity of published work, ensuring that the scientific community continues to operate on a foundation of rigorous, reliable research.

A comprehensive breakdown of typical journal publication fees was delivered, elucidating why some journals charge higher fees for their publishing services.

Importantly, we also shared practical strategies to manage journal publication fees. Tips ranged from acquiring grants and waivers to selecting lower-cost journals without compromising the prestige associated with your chosen publication. Balancing these factors effectively can alleviate the financial burden while preserving your academic reputation.

Call-to-Action

We encourage you, as authors, to carefully weigh all these factors when deciding where to publish your research. Remember, knowledge is power. The more informed you are about the nuances of journal publishing, the better equipped you’ll be to make decisions that align with your financial capabilities and academic goals.

Keep exploring, keep questioning, and keep publishing. Your contribution to the world of knowledge is invaluable.

3 thoughts on “Understanding Journal Publication Fees: A Compact Guide”

Leave a comment cancel reply.

You need to be logged in to access this feature. Click “Confirm” to log in to your existing account or create a new account.

Become Membership Confirmation

You must purchase an AGU membership to complete this session. Click on confirm to purchase.

Leaving AGU

You are redirecting to an external site. Are you sure you want to continue?

We are experiencing difficulty processing your payment. Please do not refresh the page or submit again.

Contact our Member Service Center for help at [email protected] , or 800.966. 2481 (toll-free in North America), or +1 202.462.6900.

- Leadership and Governance

- Publish with AGU

- Explore Meetings

- Learn and Develop

- Share and Advocate

- College of Fellows

- AGU Connect

Welcome to AGU's new digital experience

Learn more about our digital vision.

Check out current highlights for the new platform and what's coming in the future. We're continuously improving the experience with your feedback!

Important Short Cuts

Important links, interesting articles.

Seismic Sensors in Orbit

Publication fees

AGU is committed to inclusive and equitable scientific publishing. All accepted papers will be published regardless of the author’s ability to pay publication fees. Depending on the journal, there are 3 types of fees that might be associated with the publication of your paper: Base Publication Fee, Excess Page Fee (for overlength articles), or Open Access Article Processing Charge (OA APC). Details on these fees are provided below. If you need any assistance, please contact [email protected] .

To ensure availability of funding is not a barrier to publication, AGU provides various funding options for our authors, including waivers. The options are detailed on our Funding Options page. The funding options vary depending on the type of journal you choose: hybrid subscription journals (authors are not required to publish as Open Access) or fully gold Open-Access journals (all articles are published as Open Access).

Base Publication Fees

Base Publication Fees are flat fees for papers up to a certain amount of publication units (PU) and are submitted to AGU’s hybrid subscription journals. Overlength papers incur Excess Page Fees (see section below).

The formula for PU = number of words/500 + number of figures + number of tables. Articles exceeding a certain amount of PUs incur excess page fees.

Word count includes abstract, acknowledgements, text (and in-text citations), figure captions, table captions, and appendices. Equations count as one word no matter the size. Equations are not copyedited.

Word count excludes title, author list and affiliations, key words, key points, plain language summary, table text, open research section, references, and supporting information. Supporting information is not copyedited.

Base publication fees and excess page fees are waived for authors publishing their articles as Open Access. Commentaries, Introductions, Viewpoints, Comments, and Replies are free to publish.

Excess page fees

Longer papers are permitted in all journals except Geophysical Research Letters (GRL).

Overlength papers incur excess page fees in addition to the base publication fee due to increased editorial and production costs.

Excess Page Fees apply for papers with more than 25 PUs with the exception of review articles which incur excess page fees after 30 PUs

Open Access Article Processing Charges (OA APCs)

As a part of our mission, AGU is focused on making science available to the widest possible audience. Open Access removes subscription paywalls, which means that more people will have access to your research so they can actively cite, read, and share data with the least possible restrictions. Authors (or their institutions or funders) pay an Open Access Article Processing Charge (APC) and retain copyright of their article which they can publish under a Creative Commons license (choosing among CC-BY, CC-BY-NC, CC-BY-ND, or CC-BY-NC-ND).

For authors choosing to publish as Open Access, there are no base publication fees or excess page fees. The APCs for AGU journals are listed in the tables below.

Publication Fees Tables

See tables below for Base Publication Fees, Excess Page Fees, and Open Access Article Processing Charges (APCs). For funding options and waivers, visit our Funding Options page for publication fees.

AGU Hybrid Subscription Journals

|

|

|

|

*Base Publication and Excess Page Fees are waived for authors publishing their articles as Open Access. Information on taxes and licensing can be found on the Wiley website linked on the individual APCs below. |

|

| $0 | $125 |

|

|

| $1,000 | $125 |

|

|

| $0 | $125 |

|

|

| $1,000 | $125 |

|

|

| $0 | $0 |

|

|

| $0 | $125 |

|

AGU Fully Gold Open Access Journals

There are no Base Publication Fee or Excess Page Fees for publishing in AGU’s fully gold Open Access journals.

|

|

*Information on taxes and licensing can be found on the Wiley website linked on the individual APCs below. |

|

|

|

|

| Practice Reports and Reviews: Project Reports: |

|

|

Data Article and Method paper types receive a 50% discount |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| WRR will be Fully Open Access in January 2024. For more information, including funding options for publication fees and waivers, please visit the |

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

Elsevier Policies

Transparent price setting.

Elsevier publishes journal articles under two separate models to suit author preferences:

Subscription articles funded by payments for reading made by subscribing individuals or institutions

Open access articles funded by payments for publishing made by authors, their institution or funding bodies, commonly known as Article Publishing Charges (APCs)

We calculate pricing for each of these models separately. Subscription prices are set excluding open access articles; in other words, open access articles are not factored in when setting subscription prices. This fundamental principle is enshrined in our strict no double dipping policy (see below).

At Elsevier, we publish more articles and at higher quality relative to other major publishers, yet our average list price per subscription article remains lower (by 2-3 times) than that of others. Since 2010, the number of articles submitted to Elsevier journals grew by 11%, and the volume of subscription articles published increased by 5% (compound average growth rate 2010-2021). Our average list price per subscription article grew by just 0.2% over that time (2011-2021) across our entire portfolio of journals.

Journal article price

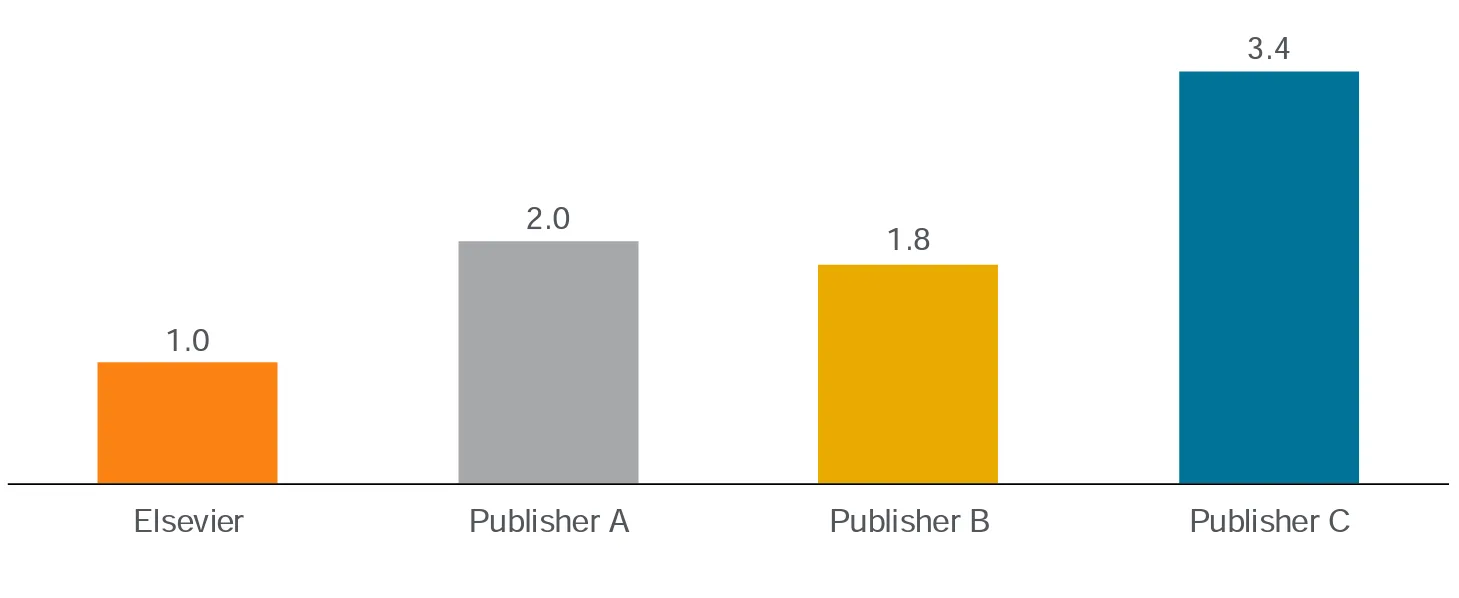

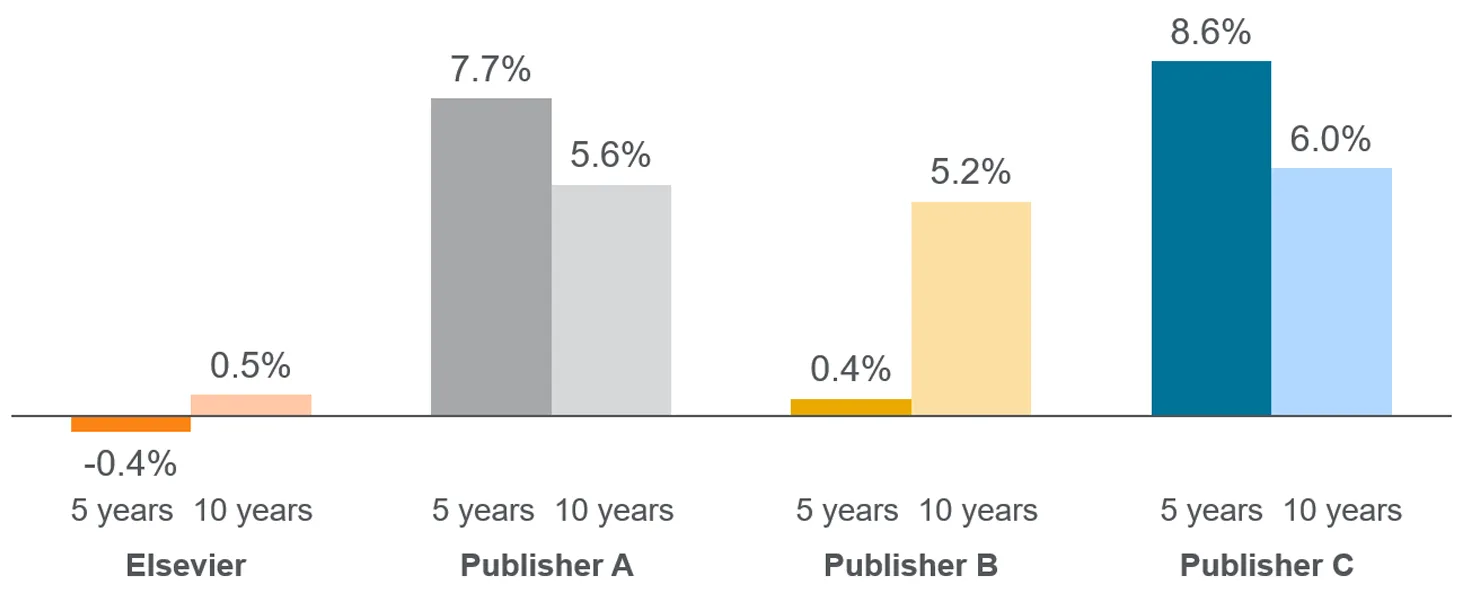

Average list price per subscription article Indexed weighted average of list prices for 2021 subscription year versus articles published in 2021 taking Elsevier as baseline (Source: Publisher websites, Scopus data)

Average list price per subscription article over time 5-year (2017-2021) and 10-year (2012-2021) compound annual growth rates (Source: Publisher websites, Scopus data)

Key facts on article growth, value and quality opens in new tab/window

Frequently asked questions on pricing

What do fees pay for.

The fees that authors pay help to support the extensive work that goes into the editorial review, peer review and publishing process that ensures research is reliable and helps to accelerate progress for society

Our 2,700 journals enhance the record of scientific knowledge by applying high standards of quality in everything they publish and ensuring trusted research can be accessed, shared and built upon by others. In 2021, we received 2.5 million research papers from authors. These were carefully reviewed by our 2,000-strong in-house editorial teams in collaboration with 29,000 editors and 1.4 million expert reviewers around the world, resulting in over 600,000 articles being enhanced, indexed, published and promoted following a peer review.

Can you be more transparent in what you charge?

We are constantly striving to be more transparent in all aspects of what Elsevier does, including pricing. We try to support requests for information within the bounds of financial reporting requirements and competition rules.

How are we transparent for authors?

We provide the price of publishing gold open access on each journal homepage and in

a central list opens in new tab/window

During the publication process, we automatically notify authors who are entitled to free or discounted gold open access, for example where there is an agreement with their institution or funder

During the publication process, we automatically notify authors who are entitled to free or discounted gold open access because they are in a lower- or middle-income country — our APC waiver policy explains this process

How are we transparent for librarians?

We provide a range of information on our website opens in new tab/window about our pricing competitiveness; how our pricing corresponds to quality; and publishing model uptake across subscription and open access

We publicly announce significant agreements, including our open access pilots

We provide a list of our journal subscription prices

We describe the process we follow to calculate list prices

We describe the process to ensure we do not double dip

We also show the number of articles that are published gold open access, and the number which are financed through subscriptions, on each journal homepage, to allow librarians to validate this

Do you double dip, i.e., charge for the same article twice?

We do not ‘double dip’. We can be reimbursed for an article in two ways — through an Article Publishing Charge (APC) to publish the article and make it available to read by everyone, or a subscription fee to pay for reading the article. We either charge for publishing an article or reading an article but we never charge for the same article twice. We have a strict no double-dipping policy.

How do you help authors who cannot afford to pay to be published?

As part of our commitment to inclusion and diversity in science, we believe it is critical to support researchers from low and middle-income countries to publish gold open access, if they wish to do so. When publishing in fully open access journals, we fully waive all open access charges for authors from 69 countries ( Group A opens in new tab/window ) and give a 50% discount for authors from 57 countries ( Group B opens in new tab/window ).

We offer a choice of journals with open access publishing charges ranging from $150 to $9,900. We will also consider requests for accommodations on a case by case basis for authors who are required to publish open access but do not have the financial means to do so. We provide high-quality subscription publishing options in our journals, so authors always have a choice of how they publish.

If more authors are publishing gold open access, why don’t you reduce your subscription fees?

Subscription fees are based on a range of factors, including the volume of subscription articles, the quality of a journal, journal usage and market and competitive considerations. When calculating subscription prices, we only take into account subscription articles; the number of articles published gold open access has no bearing on the way we set subscription fees.

We publish more articles and at higher quality relative to other major publishers, yet our average list price per subscription article remains lower (by 2-3 times) than that of others. Since 2010, the number of articles submitted to Elsevier journals grew by 11%, and the volume of subscription articles published increased by 5% (compound average growth rate 2010-2021). Our average list price per subscription article grew by just 0.2% over that time (2011-2021) across our entire portfolio.

See here for more information on Elsevier article volumes, value and quality.

Article Publishing Charges (APCs)

Irrespective of the publishing model chosen by the author, our goal is to ensure articles are published as quickly as possible, subject to appropriate quality controls, and widely disseminated.

Where an author has chosen to publish open access, which typically involves the payment of an article publishing charge (APC) by the author, their institution or funding body, we make their article freely available immediately upon publication on ScienceDirect in perpetuity with the author’s chosen user license attached to it.

Elsevier’s APCs are set on a per journal basis, fees range between approximately $200 and $10,400 US Dollars, excluding tax, with prices clearly displayed on our APC price list opens in new tab/window and on journal homepages.

Adjustments in Elsevier’s APCs are under regular review and are subject to change. We set APCs based on the following criteria which are applied to open access articles only:

Journal quality (as measured by journal quality Field Weighted Citation Impact Tier);

The journal’s editorial and technical processes;

Competitive considerations;

Market conditions;

Other revenue streams associated with the journal.

A small percentage of titles may support more than one APC, for example when a journal supports one or more article types that require different APCs.

We do not vary the APC prices for our proprietary journals based on the user license chosen by the author. However, we also publish journals on behalf of learned societies or other third parties that reserve the right to determine their own prices and pricing policies. Any deviations in pricing from Elsevier’s standard APC price list per journal will be clearly displayed on the journal’s homepage.

Download APC prices opens in new tab/window

Fee waivers to support researchers

Our goal is to effectively bridge the digital research divide and ensure that publishing in open access journals is accessible for authors in developing countries.

We grant waivers in cases of genuine need, therefore we automatically apply APC waivers or discounts to those articles in gold open access journals for which all author groups are based in a country eligible for the Research4Life program opens in new tab/window . When publishing in fully open access journals, we fully waive all APCs for authors from 69 countries ( Group A opens in new tab/window ) and give a 50% discount for authors from 57 countries ( Group B opens in new tab/window ).

If an author group from a non-Research4Life country cannot afford the APC to publish an article in a gold open access journal and they can demonstrate they had no research funding, we will consider individual waiver requests on a case-by-case basis.

Our waiving policy does not apply to hybrid journals. Authors publishing in hybrid journals can publish under the subscription model at no cost and make use of the Elsevier sharing policy .

For patients and caregivers , we will consider individual waiver requests on a case-by-case basis.

Open access agreements and funding body arrangements

Elsevier supports over 2,000 institutions globally to publish open access through transformative agreements .

We have established arrangements to help authors comply with the open access requirements of the major funding bodies and how they can be reimbursed for publication fees when publishing in Elsevier journals.

Reimbursement policy

To ensure Elsevier does not charge twice for the same article, we will fully refund an APC when alternative funding is provided for the open access article. For example, where an open access article is part of a Special Issue which is later made available in its entirety on an open access basis, such as through sponsorship by an organization, we will fully refund individual APCs paid by an author or on their behalf.

Elsevier will offer a credit for use against a future open access publication in the following circumstances:

A delay in delivering open access : When an article is not available open access on ScienceDirect by the time the issue in which the article is included is published in its final version, we will offer a credit for use against a future publication with Elsevier.

Incorrect licensing : When an article is made freely available on Science Direct in final published form but does not display the author’s chosen user license due to our error, we will offer a credit for use against a future publication with Elsevier.

No refund or credit will be offered in the following circumstances:

Article retraction or removal : Elsevier has provided publishing services. The later retraction or removal of the article is typically for reasons beyond our control, and does not detract from the publishing services provided, nor from our ongoing maintenance of the scientific record, e.g., corrections to the record.

Delays resulting from editorial decisions or author changes : These are a standard part of the publishing process.

License changes : Where an author requests a change to the user license they initially chose we will endeavor to respond to these within 5 working days.

Circumstances beyond our control : This may include, for example, where natural or other disasters prevent us from fulfilling our obligations.

Article unavailable on another platform : Elsevier’s responsibility is to ensure that the definitive published versions of articles we publish are available on ScienceDirect, or any successor platform, in ways that are accessible to all. We provide APIs to enable third party platforms to manage this process themselves, for example to identify and pull gold open access articles or to update their platforms to reflect changes subsequently made to the article, such as author license choice changes, errata, and retractions. Elsevier is not responsible for ensuring third party repositories maintain accurate metadata and full-text.

Subscription prices

Elsevier publishes subscription articles whose publication is funded by payments that are made by subscribing individuals or institutions. Subscription prices are set independent of open access articles and open access articles are not included when calculating subscription prices. Subscription prices are calculated and adjusted based on the following criteria:

Article volume

Journal quality (as measured by journal quality Field Weighted Citation Impact Tier)

Journal usage

Editorial processes

Competitive considerations

Other revenue streams such as commercial contributions from advertising, reprints and supplements

These criteria are applied only to subscription articles, not to open access articles, when setting list prices. For specific information please see our subscription price list for librarians and agents .

Purchasing options

Elsevier provides a range of purchasing options for subscription articles which are tailored for a wide variety of people. These include:

For libraries and institutions:

There are a number of subscription options available which are tailored according to the specific customer situation and reflect a number of factors. For customers who purchase collections these considerations include competitive considerations, market conditions, the number of archival rights they purchase, and agreement specific factors like agreement length, currency and payment terms. Collection prices are adjusted on an annual basis, and any adjustment is based on factors including competitive considerations, market conditions, the number, quality, and usage of subscription articles published, and on technical features and platform capabilities. Open access articles are not included in these calculations. Please find more details on pricing .

Individuals: Researchers who are not affiliated to an institution, or who would simply like convenient access to a title not available from their library, can take advantage of our personal access options. These options include credit card based transactional article sale and article rental.

Please find more information on our free and low-cost access programs .

No double dipping

Elsevier does not charge subscribers for open access articles; when calculating subscription prices, we only take into account subscription articles — we do not double dip.

Concerns around double dipping are often premised on the expectation that open access articles are replacing the number of subscription articles being published and therefore that prices should be changing to correspond to this. See here for the latest data on Elsevier article volume growth, value and quality opens in new tab/window .

List prices for journals that publish both open access and subscription articles

Adjustments in individual journal subscription list prices will be based only on criteria applied to subscription articles . Open access articles will not be considered in the individual journal list price. Similarly, the APC per journal will only be determined based on the criteria applied to open access articles .

Collections

As with journal list prices, collection prices reflect subscription articles only; they are linked to the prices of individual titles in a collection, which do not count open access articles when setting prices.

Retrospective open access

To ensure we uphold our no double dipping policy and separate calculations regarding list prices from open access articles, we do not offer authors the option to make a subscription article gold open access retrospectively after publication as a general rule.

However, we appreciate that there are sometimes exceptional circumstances and we want to assist authors where possible. In such instances, authors can make a subscription article, published in a hybrid journal, gold open access up until 31 January of the following year. For example, if the article is published in March 2022, the author can make it open access up until the 31 January 2023. This cut-off date is necessary to accurately assess the open access uptake in each individual hybrid journal for the previous year which ensures we do not charge subscribers for open access content. Please contact us to request retrospective open access or for further details opens in new tab/window .

Geographical Pricing for Open Access (GPOA) Pilot details

Elsevier is piloting a program from January 2024 to set APC prices for 143 gold open access journals according to the income level of the country of the corresponding author.

For these pilot journals we will waive the APC for corresponding authors who are based in low-income countries as classified by the World Bank as of July 2024.

For articles whose corresponding authors are based in lower-middle-countries the geo-price will be 20 percent of the APC global list price.

Corresponding authors based in upper-middle-income countries and where R&D intensity (domestic expenditure on R&D expressed as a percentage of GDP according to OECD) is below two percent are defined in three different groups based on GNI per capita and will see a different APC geo-price based on the GNI per capita of the country ranging from 45 percent to 90 percent of the APC list price.

GNI Per Capita

Country Group | From | To | APC Price |

|---|---|---|---|

Low-income | $0 | $1,145 | 0% of list price |

Lower-Middle-Income | $1,146 | $4,515 | 20% of list price |

Upper-Middle-Income: Group 1 | $4,516 | $7,679 | 45% of list price |

Upper-Middle-Income: Group 2 | $7,680 | $10,843 | 65% of list price |

Upper-Middle-Income: Group 3 | $10,844 | $14,005 | 90% of list price |

*Based on World Bank - 01 July 2024

Elsevier will use GNI per Capita ( Atlas Method) opens in new tab/window as the key indicator for determining the APC pricing tier. This is a widely used economic indicator provided by the World Bank and has proved to be a useful, easily available and annually updated indicator that is closely correlated with other, nonmonetary measures of the quality of life. The Atlas method, with three-year average exchange rates adjusted for inflation, lessens the effect of exchange rate fluctuations and abrupt changes.

The GPOA pilot methodology calculates discounts on the list APC as a percentage of the list price differently for each group of countries. To do this, we use the middle point of each group as a reference. This middle point is determined by comparing it to the starting threshold set for high-income countries by the World Bank.

Elsevier may grant additional waivers to countries where full waiver policies are currently in place for specific reasons, or in cases where Elsevier is unable to receive payments due to trade sanctions ( read more ). The article publishing charge that applies is automatically calculated as part of the submission process and will take this into consideration. If you have any further questions, please contact researcher support.

Country Groups

| ||

Afghanistan | Korea, North | South Sudan |

Burkina Faso | Liberia | Sudan |

Burundi | Madagascar | Syrian Arab Republic |

Central African Republic | Malawi | Togo |

Chad | Mali | Uganda |

Congo, Democratic Republic | Mozambique | Yemen |

Eritrea | Niger | |

Ethiopia | Rwanda | |

Gambia | Sierra Leone | |

Guinea-Bissau | Somalia | |

| ||

Angola | Jordan | Samoa |

Bangladesh | India | Sao Tome and Principe |

Benin | Kenya | Senegal |

Bhutan | Kiribati | State of Palestine |

Bolivia | Kyrgyzstan | Solomon Islands |

Cabo Verde | Lao People's Democratic Republic of | Sri Lanka |

Cambodia | Lesotho | Tanzania, the United Republic of |

Cameroon | Mauritania | Tajikistan |

Comoros | Micronesia | Timor-Leste |

Congo | Morocco | Tunisia |

Côte d'Ivoire | Myanmar | Uzbekistan |

Djibouti | Nepal | Vanuatu |

Egypt | Nicaragua | Viet nam |

Eswatini | Nigeria | Zambia |

Ghana | Pakistan | Zimbabwe |

Guinea | Papua New Guinea | |

Haiti | Philippines | |

Honduras | ||

| ||

Albania | Gabon | Namibia |

Armenia | Georgia | North Macedonia |

Azerbaijan | Guatemala | Paraguay |

Belarus | Indonesia | Peru |

Belize | Iran | South Africa |

Botswana | Iraq | Suriname |

Colombia | Jamaica | Thailand |

Ecuador | Lebanon | Tonga |

El Salvador | Libya | Turkmenistan |

Equatorial Guinea | Moldova | Tuvalu |

Fiji | Mongolia | Ukraine |

| ||

Bosnia and Herzegovina | Grenada | Serbia |

Brazil | Kazakhstan | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

Cuba | Marshall Islands | Turkey |

Dominica | Mexico | |

Dominican Republic | Montenegro | |

| ||

Argentina | Malaysia | Mauritius |

Costa Rica | Maldives | Saint Lucia |

Based on the most recent GDP per capita available (up to 2023) and the World Bank Country Groups for FY 2025, valid from the 1st of July 2024

View the list of participating journals

Understanding Submission and Publication Fees

- Research Process

- Peer Review

A number of journals charge fees to authors of one kind or another. Pre-publication fees, such as a submission fee or membership fee, are less common. Researchers are more likely to encounter post-publications fees, such as an article processing charge or page fee.

Updated on January 1, 2012

When trying to target the right journal for publication of your manuscript, it is easy to get overwhelmed by the diversity of not only journals but also potential author fees. What are all of these types of fees? Which types of journals generally charge them? When? Why?

Before addressing this slew of questions, it is important to note a common oversimplification: that traditional journals are solely based on a reader-pays model, in which institutional libraries typically pay for access to content, and that open access journals, supporting " unrestricted access and unrestricted reuse ,” are always based on an author-pays model (see our article on open access myths for more information). In other words, as an author, you may have to pay for submission to and/or publication in a subscription-based journal and may not have to do so for an open access one. The latter concept is made possible by alternative sources of revenue that cover the costs of the editorial, peer review, and publication processes, such as paywalled premium content, advertising, or subsidy by a journal's affiliated foundation or society.

Note also that for both traditional and open access publications that do entail so-called “author” charges, you may not have to pay these fees in full because of discounts related to institutional membership programs, your own society membership, or waivers of service (such as if in-house copyediting is not needed). Moreover, you may not have to pay full or even discounted fees due to waivers based on either financial hardship or your country of origin's economic status or due to coverage by your institution, department, or funder/grant; in fact, for open access publication, only 5% to 12% of fees are ever paid using personal funds.

Here, we summarize a few of the most common fees associated with manuscript submission and publication, with a focus on the pre- and post-acceptance charges that may be most relevant to you as an author. Note that all quoted price ranges are rough estimates based on a brief survey, so please check specific journals' and publishers' websites for more accurate information. These sites (e.g., PLOS and BioMed Central ) should provide up-to-date information on journals' specific fee types, discounts, and waivers. Your institution and/or funder may also be able to provide more in-depth explanations about open access mandates, if any, and cost coverage.

Pre-acceptance fees

Submission fees. Both subscription-based and open access journals may charge a fee (typically $50-125) at the time of manuscript submission to help to fund editorial and peer review administration. From an author's standpoint, these fees might deter submission due to the existence of many journals without such charges. However, submission fees thus present the advantage of decreasing competition for review and acceptance, potentially enhancing publication speed . The effect on journal quality, and therefore potentially on impact, may also be positive: the quality of submissions may increase, as only authors with confidence that they are choosing the right journal will be willing to pay a submission fee. Interestingly, it has also been posited that submission fees can increase authors' concern about the quality of peer review and the reasoning behind manuscript rejection, potentially motivating greater accountability on the part of journals.

Membership fees. The open access journal PeerJ is unique in charging a one-time membership fee ($100-350) that covers the editorial process and peer review, as well as the possible publication, of one, two, or a limitless number of manuscripts per year (depending on the level of membership). Each author on a manuscript, up to 12 authors, must pay the fee and a must contribute to the PeerJ community yearly, such as by participating in peer review. It is also possible to pay for membership after acceptance of a manuscript, but this increases the cost. Advantages of this membership approach include relatively rapid publication and avoidance of repeatedly paying pre- and post-acceptance fees. [Editor's note: PeerJ now offers a per-article price , as well.]

Post-acceptance fees

These fees either stand alone or are charged subsequent to a submission fee.

Page/color printing charges. To cover the cost of printing, and particularly color printing, certain traditional journals charge per page (often $100-250 each) and/or per color figure (about $150-1,000 each). In rare cases, supplementary materials may also incur a flat charge or a charge per item or page, with fees usually ranging from $150-500.

Publication fees. These fees, charged by certain open access journals post-acceptance, are also known as author publishing charges or article processing charges (APCs) and range from $8-3,900. APCs may be driven down by submission fees, particularly among open access journals with high rejection rates. In contrast to post-acceptance charges by traditional journals, these APCs are more often flat fees because they primarily fund peer review and online dissemination, which are length independent. In rare cases, post-acceptance, page/color-independent fees may also be billed by traditional journals (e.g., the Journal of Clinical Investigation ) without unrestricted access and/or reuse provisions. Generally, these fees provide both retrospective and prospective coverage, including of peer review management by the editorial staff or board (i.e., identifying and following up with peer reviewers), manuscript preparation (e.g., copyediting), journal production (e.g., layout), open access online publication and hosting, indexing (e.g., in PubMed), and archiving.

Be aware that “predatory” journals may take advantage of the APC-based model to receive payment in return for minimal peer review and processing, so be sure to look for warning signs and consider checking whether your target journal is listed by the Directory of Open Access Journals . A truly open access journal should also meet the two-fold requirement defined above by PLOS : “unrestricted access and unrestricted reuse,” meaning that an open access article must not only be freely accessible to readers but also freely available for copying, distribution, and derivative work, as long as the original author is acknowledged. In particular, open access articles are often associated with a CC-BY license, although certain journals may not support reuse/derivation.

Regarding the value added by submitting to APC-charging journals, a weak correlation between citation-based impact and APCs has been found for open access journals, implying that higher fees are necessitated by higher rejection rates, which in turn imply greater selectivity and prestige. However, note that this analysis did not take submission fees into account.

Conclusions

In sum, when choosing a journal for manuscript submission, the array of pre- and post-acceptance fees should not be an immediate deterrent, especially if the journal's scope and content are a good fit for your work, because of both potential fee assistance and added value. You should thus focus on asking yourself a more personalized question beyond what, who, when, and why: is the journal truly the right fit for my specific research and my own publication goals?

Michaela Panter, PhD

See our "Privacy Policy"

Secure funding for your submission fees

Use our Grant services to ensure you have the funds for all of your research needs.

- Chinese (Traditional)

- Springer Support

- Solution home

- Author and Peer Reviewer Support

- Publishing Costs

Costs of publishing in Springer Nature journal

The cost of publishing an article depends on the publishing model(s) offered by the journal.

If you wish to publish in one of our subscription based journals then in the majority of cases there is no charge. Charges may apply for colour figures or over-length articles and some journals have page charges. You can find information regarding all of these costs on the individual journal home pages.

If you wish to publish in an open access journal or an open access article in a hybrid journal , there will be an Article Processing Charge (APC) to be paid by the author or their funding institution . APC are listed on individual journal pages, either in Fees and Funding section on within Submission guidelines . Visit our Open Access Books and Journals page for additional details about open access publishing.

If you are not sure which journal to publish your article in, visit our find the right journal to submit your article page for additional details. We also provide journal author tutorials with interactive courses on our journal author academy page.

Related Articles

- Fees for publishing in an "Open Choice" Journal

- Publish an Open Access manuscript

- NIH compliant

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- News Feature

- Published: 27 March 2013

Open access: The true cost of science publishing

- Richard Van Noorden

Nature volume 495 , pages 426–429 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

45k Accesses

285 Citations

1916 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Peer review

- Research management

A Correction to this article was published on 03 July 2013

A Correction to this article was published on 10 April 2013

This article has been updated

Cheap open-access journals raise questions about the value publishers add for their money.

Michael Eisen doesn't hold back when invited to vent. “It's still ludicrous how much it costs to publish research — let alone what we pay,” he declares. The biggest travesty, he says, is that the scientific community carries out peer review — a major part of scholarly publishing — for free, yet subscription-journal publishers charge billions of dollars per year, all told, for scientists to read the final product. “It's a ridiculous transaction,” he says.

Eisen, a molecular biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, argues that scientists can get much better value by publishing in open-access journals, which make articles free for everyone to read and which recoup their costs by charging authors or funders. Among the best-known examples are journals published by the Public Library of Science (PLoS), which Eisen co-founded in 2000. “The costs of research publishing can be much lower than people think,” agrees Peter Binfield, co-founder of one of the newest open-access journals, PeerJ , and formerly a publisher at PLoS.

But publishers of subscription journals insist that such views are misguided — born of a failure to appreciate the value they add to the papers they publish, and to the research community as a whole. They say that their commercial operations are in fact quite efficient, so that if a switch to open-access publishing led scientists to drive down fees by choosing cheaper journals, it would undermine important values such as editorial quality.

These charges and counter-charges have been volleyed back and forth since the open-access idea emerged in the 1990s, but because the industry's finances are largely mysterious, evidence to back up either side has been lacking. Although journal list prices have been rising faster than inflation, the prices that campus libraries actually pay to buy journals are generally hidden by the non-disclosure agreements that they sign. And the true costs that publishers incur to produce their journals are not widely known.

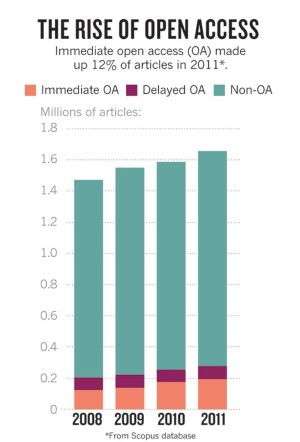

The past few years have seen a change, however. The number of open-access journals has risen steadily, in part because of funders' views that papers based on publicly funded research should be free for anyone to read. By 2011, 11% of the world's articles were being published in fully open-access journals 1 (see 'The rise of open access'). Suddenly, scientists can compare between different publishing prices. A paper that costs US$5,000 for an author to publish in Cell Reports , for example, might cost just $1,350 to publish in PLoS ONE — whereas PeerJ offers to publish an unlimited number of papers per author for a one-time fee of $299. “For the first time, the author can evaluate the service that they're getting for the fee they're paying,” says Heather Joseph, executive director of the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition in Washington DC.

The variance in prices is leading everyone involved to question the academic publishing establishment as never before. For researchers and funders, the issue is how much of their scant resources need to be spent on publishing, and what form that publishing will take. For publishers, it is whether their current business models are sustainable — and whether highly selective, expensive journals can survive and prosper in an open-access world.

The cost of publishing

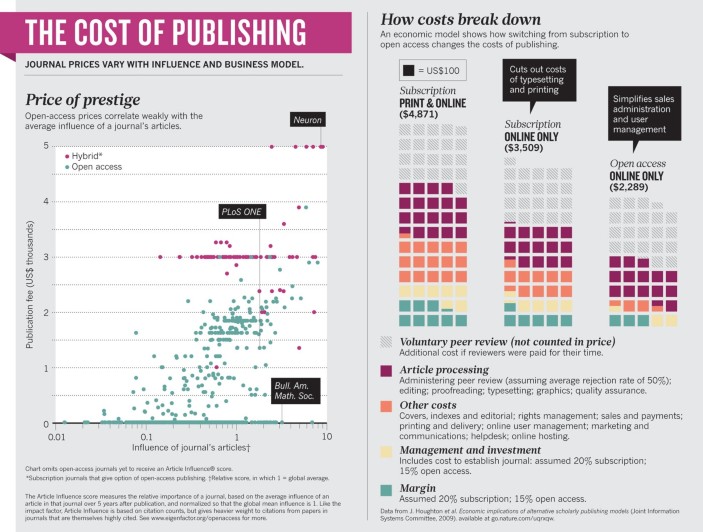

Data from the consulting firm Outsell in Burlingame, California, suggest that the science-publishing industry generated $9.4 billion in revenue in 2011 and published around 1.8 million English-language articles — an average revenue per article of roughly $5,000. Analysts estimate profit margins at 20–30% for the industry, so the average cost to the publisher of producing an article is likely to be around $3,500–4,000.

Most open-access publishers charge fees that are much lower than the industry's average revenue, although there is a wide scatter between journals. The largest open-access publishers — BioMed Central and PLoS — charge $1,350–2,250 to publish peer-reviewed articles in many of their journals, although their most selective offerings charge $2,700–2,900. In a survey published last year 2 , economist Bo-Christer Björk of the Hanken School of Economics in Helsinki and psychologist David Solomon of Michigan State University in East Lansing looked at 100,697 articles published in 1,370 fee-charging open-access journals active in 2010 (about 40% of the fully open-access articles in that year), and found that charges ranged from $8 to $3,900. Higher charges tend to be found in 'hybrid' journals, in which publishers offer to make individual articles free in a publication that is otherwise paywalled (see 'Price of prestige'). Outsell estimates that the average per-article charge for open-access publishers in 2011 was $660.

Although these fees seem refreshingly transparent, they are not the only way that open-access publishers can make money. As Outsell notes, the $660 average, for example, does not represent the real revenue collected per paper: it includes papers published at discounted or waived fees, and does not count cash from the membership schemes that some open-access publishers run in addition to charging for articles. Frequently, small open-access publishers are also subsidized, with universities or societies covering the costs of server hosting, computers and building space. That explains why many journals say that they can offer open access for nothing. One example is Acta Palaeontologica Polonica , a respected open-access palaeontology journal, the costs of which are mostly covered by government subsidies to the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw; it charges nothing for papers under 10 pages. Another is eLife , which is covered by grants from the Wellcome Trust in London; the Max Planck Society in Munich, Germany; and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Chevy Chase, Maryland. And some publishers use sets of journals to cross-subsidize each other: for example, PLoS Biology and PLoS Medicine receive subsidy from PLoS ONE , says Damian Pattinson, editorial director at PLoS ONE .

Neither PLoS nor BioMed Central would discuss actual costs (although both organizations are profitable as a whole), but some emerging players who did reveal them for this article say that their real internal costs are extremely low. Paul Peters, president of the Open Access Scholarly Publishing Association and chief strategy officer at the open-access publisher Hindawi in Cairo, says that last year, his group published 22,000 articles at a cost of $290 per article. Brian Hole, founder and director of the researcher-led Ubiquity Press in London, says that average costs are £200 (US$300). And Binfield says that PeerJ 's costs are in the “low hundreds of dollars” per article.

The picture is also mixed for subscription publishers, many of which generate revenue from a variety of sources — libraries, advertisers, commercial subscribers, author charges, reprint orders and cross-subsidies from more profitable journals. But they are even less transparent about their costs than their open-access counterparts. Most declined to reveal prices or costs when interviewed for this article.

The few numbers that are available show that costs vary widely in this sector, too. For example, Diane Sullenberger, executive editor for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC, says that the journal would need to charge about $3,700 per paper to cover costs if it went open-access. But Philip Campbell, editor-in-chief of Nature , estimates his journal's internal costs at £20,000–30,000 ($30,000–40,000) per paper. Many publishers say they cannot estimate what their per-paper costs are because article publishing is entangled with other activities. ( Science , for example, says that it cannot break down its per-paper costs; and that subscriptions also pay for activities of the journal's society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington DC.)

Scientists pondering why some publishers run more expensive outfits than others often point to profit margins. Reliable numbers are hard to come by: Wiley, for example, used to report 40% in profits from its scientific, technical and medical (STM) publishing division before tax, but its 2013 accounts noted that allocating to science publishing a proportion of 'shared services' — costs of distribution, technology, building rents and electricity rates — would halve the reported profits. Elsevier's reported margins are 37%, but financial analysts estimate them at 40–50% for the STM publishing division before tax. ( Nature says that it will not disclose information on margins.) Profits can be made on the open-access side too: Hindawi made 50% profit on the articles it published last year, says Peters.

Commercial publishers are widely acknowledged to make larger profits than organizations run by academic institutions. A 2008 study by London-based Cambridge Economic Policy Associates estimated margins at 20% for society publishers, 25% for university publishers and 35% for commercial publishers 3 . This is an irritant for many researchers, says Deborah Shorley, scholarly communications adviser at Imperial College London — not so much because commercial profits are larger, but because the money goes to shareholders rather than being ploughed back into science or education.

But the difference in profit margins explains only a small part of the variance in per-paper prices. One reason that open-access publishers have lower costs is simply that they are newer, and publish entirely online, so they don't have to do print runs or set up subscription paywalls (see 'How costs break down'). Whereas small start-ups can come up with fresh workflows using the latest electronic tools, some established publishers are still dealing with antiquated workflows for arranging peer review, typesetting, file-format conversion and other chores. Still, most older publishers are investing heavily in technology, and should catch up eventually.

Costly functions

The publishers of expensive journals give two other explanations for their high costs, although both have come under heavy fire from advocates of cheaper business models: they do more and they tend to be more selective. The more effort a publisher invests in each paper, and the more articles a journal rejects after peer review, the more costly is each accepted article to publish.

Publishers may administer the peer-review process, which includes activities such as finding peer reviewers, evaluating the assessments and checking manuscripts for plagiarism. They may edit the articles, which includes proofreading, typesetting, adding graphics, turning the file into standard formats such as XML and adding metadata to agreed industry standards. And they may distribute print copies and host journals online. Some subscription journals have a large staff of full-time editors, designers and computer specialists. But not every publisher ticks all the boxes on this list, puts in the same effort or hires costly professional staff for all these activities. For example, most of PLoS ONE 's editors are working scientists, and the journal does not perform functions such as copy-editing. Some journals, including Nature , also generate additional content for readers, such as editorials, commentary articles and journalism (including the article you are reading). “We get positive feedback about our editorial process, so in our experience, many scientists do understand and appreciate the value that this adds to their paper,” says David Hoole, marketing director at Nature Publishing Group.

The costs of research publishing can be much lower than people think.

The key question is whether the extra effort adds useful value, says Timothy Gowers, a mathematician at the University of Cambridge, UK, who last year led a revolt against Elsevier (see Nature http://doi.org/kwd ; 2012 ). Would scientists' appreciation for subscription journals hold up if costs were paid for by the authors, rather than spread among subscribers? “If you see it from the perspective of the publisher, you may feel quite hurt,” says Gowers. “You may feel that a lot of work you put in is not really appreciated by scientists. The real question is whether that work is needed, and that's much less obvious.”

Many researchers in fields such as mathematics, high-energy physics and computer science do not think it is. They post pre- and post-reviewed versions of their work on servers such as arXiv — an operation that costs some $800,000 a year to keep going, or about $10 per article. Under a scheme of free open-access 'Episciences' journals proposed by some mathematicians this January, researchers would organize their own system of community peer review and host research on arXiv, making it open for all at minimal cost (see Nature http://doi.org/kwg ; 2013 ).

These approaches suit communities that have a culture of sharing preprints, and that either produce theoretical work or see high scrutiny of their experimental work — so it is effectively peer reviewed before it even gets submitted to a publisher. But they find less support elsewhere — in the highly competitive biomedical fields, for instance, researchers tend not to publish preprints for fear of being scooped and they place more value on formal (journal-based) peer review. “If we have learned anything in the open-access movement, it's that not all scientific communities are created the same: one size doesn't fit all,” says Joseph.

The value of rejection

Tied into the varying costs of journals is the number of articles that they reject. PLoS ONE (which charges authors $1,350) publishes 70% of submitted articles, whereas Physical Review Letters (a hybrid journal that has an optional open-access charge of $2,700) publishes fewer than 35%; Nature published just 8% in 2011.

The connection between price and selectivity reflects the fact that journals have functions that go beyond just publishing articles, points out John Houghton, an economist at Victoria University in Melbourne, Australia. By rejecting papers at the peer-review stage on grounds other than scientific validity, and so guiding the papers into the most appropriate journals, publishers filter the literature and provide signals of prestige to guide readers' attention. Such guidance is essential for researchers struggling to identify which of the millions of articles published each year are worth looking at, publishers argue — and the cost includes this service.

A more-expensive, more-selective journal should, in principle, generate greater prestige and impact. Yet in the open-access world, the higher-charging journals don't reliably command the greatest citation-based influence, argues Jevin West, a biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. Earlier this year, West released a free tool that researchers can use to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of open-access journals (see Nature http://doi.org/kwh ; 2013 ).

And to Eisen, the idea that research is filtered into branded journals before it is published is not a feature but a bug: a wasteful hangover from the days of print. Rather than guiding articles into journal 'buckets', he suggests, they could be filtered after publication using metrics such as downloads and citations, which focus not on the antiquated journal, but on the article itself (see page 437).

Alicia Wise, from Elsevier, doubts that this could replace the current system: “I don't think it's appropriate to say that filtering and selection should only be done by the research community after publication,” she says. She argues that the brands, and accompanying filters, that publishers create by selective peer review add real value, and would be missed if removed entirely.

PLoS ONE supporters have a ready answer: start by making any core text that passes peer review for scientific validity alone open to everyone; if scientists do miss the guidance of selective peer review, then they can use recommendation tools and filters (perhaps even commercial ones) to organize the literature — but at least the costs will not be baked into pre-publication charges.

These arguments, Houghton says, are a reminder that publishers, researchers, libraries and funders exist in a complex, interdependent system. His analyses, and those by Cambridge Economic Policy Associates, suggest that converting the entire publishing system to open access would be worthwhile even if per-article-costs remained the same — simply because of the time that researchers would save when trying to access or read papers that were no longer lodged behind paywalls.

The path to open access

But a total conversion will be slow in coming, because scientists still have every economic incentive to submit their papers to high-prestige subscription journals. The subscriptions tend to be paid for by campus libraries, and few individual scientists see the costs directly. From their perspective, publication is effectively free.

Of course, many researchers have been swayed by the ethical argument, made so forcefully by open-access advocates, that publicly funded research should be freely available to everyone. Another important reason that open-access journals have made headway is that libraries are maxed out on their budgets, says Mark McCabe, an economist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. With no more library cash available to spend on subscriptions, adopting an open-access model was the only way for fresh journals to break into the market. New funding-agency mandates for immediate open access could speed the progress of open-access journals. But even then the economics of the industry remain unclear. Low article charges are likely to rise if more-selective journals choose to go open access. And some publishers warn that shifting the entire system to open access would also increase prices because journals would need to claim all their revenue from upfront payments, rather than from a variety of sources, such as secondary rights. “I've worked with medical journals where the revenue stream from secondary rights varies from less than 1% to as much as one-third of total revenue,” says David Crotty of Oxford University Press, UK.

Some publishers may manage to lock in higher prices for their premium products, or, following the successful example of PLoS, large open-access publishers may try to cross-subsidize high-prestige, selective, costly journals with cheaper, high-throughput journals. Publishers who put out a small number of articles in a few mid-range journals may be in trouble under the open-access model if they cannot quickly reduce costs. “In the end,” says Wim van der Stelt, executive vice president at Springer in Doetinchem, the Netherlands, “the price is set by what the market wants to pay for it.”

In theory, an open-access market could drive down costs by encouraging authors to weigh the value of what they get against what they pay. But that might not happen: instead, funders and libraries may end up paying the costs of open-access publication in place of scientists — to simplify the accounting and maintain freedom of choice for academics. Joseph says that some institutional libraries are already joining publisher membership schemes in which they buy a number of free or discounted articles for their researchers. She worries that such behaviour might reduce the author's awareness of the price being paid to publish — and thus the incentive to bring costs down.

And although many see a switch to open access as inevitable, the transition will be gradual. In the United Kingdom, portions of grant money are being spent on open access, but libraries still need to pay for research published in subscription journals. In the meantime, some scientists are urging their colleagues to deposit any manuscripts they publish in subscription journals in free online repositories. More than 60% of journals already allow authors to self-archive content that has been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication, says Stevan Harnad, a veteran open-access campaigner and cognitive scientist at the University of Quebec in Montreal, Canada. Most of the others ask authors to wait for a time (say, a year), before they archive their papers. However, the vast majority of authors don't self-archive their manuscripts unless prompted by university or funder mandates.

As that lack of enthusiasm demonstrates, the fundamental force driving the speed of the move towards full open access is what researchers — and research funders — want. Eisen says that although PLoS has become a success story — publishing 26,000 papers last year — it didn't catalyse the industry to change in the way that he had hoped. “I didn't expect publishers to give up their profits, but my frustration lies primarily with leaders of the science community for not recognizing that open access is a perfectly viable way to do publishing,” he says.

Change history

26 june 2013.

The scale on the y-axis of ‘The rise of open access’ was originally mislabelled. This has now been corrected.

05 April 2013

This article originally described David Solomon as an economist; he is a psychologist. It also wrongly defined STM as ‘science, technology and mathematics’ instead of ‘scientific, technical and medical’. These errors have been corrected.

Laakso, M. & Björk, B.-C. BMC Medicine 10 , 124 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Solomon, D. J. & Björk, B.-C. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 63 , 1485–1495 (2012).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cambridge Economic Policy Associates Activities, costs and funding flows in the scholarly communications system in the UK (Research Information Network, 2008).

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

Tweet Follow @NatureNews

Related links

Related links in nature research.

The future of publishing: A new page 2013-Mar-27

Gold on hold 2013-Feb-26

Price doesn't always buy prestige in open access 2013-Jan-22

Britain aims for broad open access 2012-Jun-19

Open access comes of age 2011-Jun-21

Nature special: The future of publishing

Related external links

Cost-effectiveness for open-access journals

A study of open-access journals using article-processing charges

Economic implications of alternative scholarly publishing models: exploring the costs and benefits

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Van Noorden, R. Open access: The true cost of science publishing. Nature 495 , 426–429 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/495426a

Download citation

Published : 27 March 2013

Issue Date : 28 March 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/495426a

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Scientific sinkhole: estimating the cost of peer review based on survey data with snowball sampling.

- Allana G. LeBlanc

- Joel D. Barnes

- Jean-Philippe Chaput

Research Integrity and Peer Review (2023)

What senior academics can do to support reproducible and open research: a short, three-step guide

- Olivia S. Kowalczyk

- Alexandra Lautarescu

- Samuel J. Westwood

BMC Research Notes (2022)

Joining the meta-research movement: A bibliometric case study of the journal Perspectives on Medical Education

- Lauren A. Maggio

- Stefanie Haustein

- Anthony R. Artino

Perspectives on Medical Education (2022)

Higher Author Fees in Gastroenterology Journals Are Not Associated with Faster Processing Times or Higher Impact

- Daniel S. Jamorabo

- Vasilios Koulouris

- Benjamin D. Renelus

Digestive Diseases and Sciences (2022)

Microwave effect: analyzing citations from classic theories and their reinventions—a case study from a classic paper in aquatic ecology—Brooks & Dodson, 1965

- Rayanne Barros Setubal

- Daniel da Silva Farias

- Reinaldo Luiz Bozelli

Scientometrics (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Search Search

- CN (Chinese)

- DE (German)

- ES (Spanish)

- FR (Français)

- JP (Japanese)

- Open science

- Booksellers

- Peer Reviewers

- Springer Nature Group ↗

Publish an article

- Roles and responsibilities

- Signing your contract

- Writing your manuscript

- Submitting your manuscript

- Producing your book

- Promoting your book

- Submit your book idea

- Manuscript guidelines

- Book author services

- Publish a book

- Publish conference proceedings

Join thousands of researchers worldwide that have published their work in one of our 3,000+ Springer Nature journals.

Step-by-step guide to article publishing

1. Prepare your article

- Make sure you follow the submission guidelines for that journal. Search for a journal .

- Get permission to use any images.

- Check that your data is easy to reproduce.

- State clearly if you're reusing any data that has been used elsewhere.

- Follow our policies on plagiarism and ethics .

- Use our services to get help with English translation, scientific assessment and formatting. Find out what support you can get .

2. Write a cover letter

- Introduce your work in a 1-page letter, explaining the research you did, and why it's relevant.

3. Submit your manuscript

- Go to the journal homepage to start the process

- You can only submit 1 article at a time to each journal. Duplicate submissions will be rejected.

4. Technical check

- We'll make sure that your article follows the journal guidelines for formatting, ethics, plagiarism, contributors, and permissions.

5. Editor and peer review

- The journal editor will read your article and decide if it's ready for peer review.

- Most articles will be reviewed by 2 or more experts in the field.

- They may contact you with questions at this point.

6. Final decision

- If your article is accepted, you'll need to sign a publishing agreement.

- If your article is rejected, you can get help finding another journal from our transfer desk team .

- If your article is open access, you'll need to pay a fee.

- Fees for OA publishing differ across journals. See relevant journal page for more information.

- You may be able to get help covering that cost. See information on funding .

- We'll send you proofs to approve, then we'll publish your article.

- Track your impact by logging in to your account

Get tips on preparing your manuscript using our submission checklist .

Each publication follows a slightly different process, so check the journal's guidelines for more details

Open access vs subscription publishing

Each of our journals has its own policies, options, and fees for publishing.

Over 600 of our journals are fully open access. Others use a hybrid model, with readers paying to access some articles.

Publishing your article open access has a number of benefits:

- Free to access and download

- Reaches a wider global audience

- 1.6x more citations

- 6x more downloads

- 4.9 average Altmetric attention (vs 2.1 subscription)

It's free to publish your article in a subscription journal, but there are fees for publishing open access articles. You'll need to check the open access fees for the journal you choose.

Learn more about open access

Get help with funding.