Notifications

No new notifications

Check this area for program updates, such as newly added or unlocked sessions

Voice Exercises for Spasmodic Dysphonia – Your Path to Improved Vocal Health

-150x150.png)

Are you or someone you know grappling with the challenges of Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD)? In this post, we'll delve into how voice exercises for Spasmodic Dysphonia, when combined with a proper Neuro-Rehabilitation protocol, can be the key to easing symptoms, enhancing your quality of life and lead you to recovery from this condition.

Example of improvement produced by following Dr. Farias’ Recovery program for Spasmodic Dysphonia:

Before following Dr. Farias’ Neuro-Rehabilitation protocol:

After following Dr. Farias’ Neuro-Rehabilitation protocol:

What is the difference between Dr. Farias’ Neuro-Rehabilitation protocol for SD and traditional voice therapy for SD?

In the realm of Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) (also know as Laryngeal Dystonia) treatment has been traditionally focused on muscle-targeted approaches through conventional voice therapy. However, the results did not achieve the expected outcomes. It’s essential to understand that SD is not solely a muscular issue; It is a neurological condition. SD involves a complex interplay of neurological factors. This is where Dr. Farias’ groundbreaking neuroplasticity-based neuro-rehabilitation for SD comes into play. This innovative approach aims to rehabilitate the underperforming neural networks at the core of this condition, addressing both vocal and non-vocal symptoms comprehensively. Through a series of progressive exercises, this method works to retune neural function and normalise the intricate processes involved in speech production. The results have been nothing short of unprecedented, offering new hope and tangible improvements for those living with SD.

Understanding Voice rehabilitation for Spasmodic Dysphonia

Voice exercises for Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) are a vital component of managing this challenging voice disorder. These exercises are designed to address the specific vocal challenges associated with SD and help individuals regain control over their voice. Whether you have abductor or adductor SD, voice exercises can be tailored to your unique needs. They focus on improving vocal function, reducing vocal strain, and enhancing vocal control, all of which contribute to an increased quality of life. Through regular practice and guidance these exercises can be an effective tool in minimising SD symptoms and improving your overall vocal health.

Start your Recovery Journey Today

Join the complete online recovery program for dystonia patients.

Strategies for Abductor SD

For those facing abductor SD, you are guided in transitioning voiceless sounds to voiced ones and articulating sounds for easier speaking. These techniques empower you to regain control over your voice.

Strategies for Adductor SD

In the case of Adductor SD, you will use strategies to produce a smoother airflow, reducing tension and strain during speaking, leading to more comfortable and effective communication.

Key Benefits of Dr. Farias Dystonia Recovery Program

- Reduced vocal strain

- Improved vocal function

- Enhanced vocal control

- Increased quality of life

Dr. Farias’ Spasmodic Dysphonia Recovery Program

Dr. Farias has developed a comprehensive set of exercises that have aided many in improving voice quality and reducing spasm frequency and severity. These exercises encompass:

- Breathing exercises

- Vocal warm-up exercises

- Voice resonance exercises

- Articulation exercises

- Fluency exercises

- Non voice related brain training, which involves: eye tracking exercises , sensory stimulation exercises, relaxation, meditation, music and sound therapy, all design to improve your brain, auditory and vocal function

Dr. Farias’ Spasmodic Dysphonia Recovery Program is a valuable asset for individuals with SD.

Don’t let SD hold you back – take action, embrace voice exercises, and embark on your journey to improved vocal health today.

- Weill Cornell Medicine

Spasmodic Dysphonia

Related articles.

- Botulinum Toxin Injections

What is spasmodic dysphonia?

Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) is a type of dystonia, a neurologic disease that causes involuntary movements. There are two main types of SD. Adductor SD (AdSD) causes the vocal folds to come together (adduct) inappropriately during voicing, and makes up about 85-90% of SD cases. Abductor SD (AbSD), on the other hand, makes the vocal folds come apart (abduct) during connected speech.

SD usually affects adults, with a typical onset of symptoms in the thirties or fourties. The cause is unknown, and there do not appear to be any behaviors or environmental factors that increase the chance of contracting SD. The disease does not show a hereditary link in the vast majority of cases.

What are the symptoms of spasmodic dysphonia?

In AdSD, the vocal folds come together too tightly during speech, causing strained, strangled breaks in the voice. In AbSD, the vocal folds part, causing breathy or soundless breaks. In both cases, the voice breaks are irregular, and the severity of the symptoms can vary from day to day, or even over the course of a single day. It is typical for anxiety to cause symptoms to be more noticeable, and tremor (or shakiness) of the voice can be an associated feature. Those with SD often report that speaking with strangers, using the telephone, or public speaking makes the voice worse.

SD, like most dystonias, is task-specific - it is only evident during one type of activity. Other laryngeal actions, like breathing and swallowing, are usually unaffected. Sometimes, the voice will even be fluent while laughing or singing, but not during connected speech. This feature, combined with the deterioration of the voice with anxiety, occasionally causes the disorder to be mistakenly attributed to psychiatric causes. SD is not a psychiatric or psychological disease, but a true neurological one.

What does spasmodic dysphonia look like?

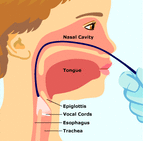

SD is a disorder of vocal fold movement, so the larynx has to be examined during voicing, and preferably during connected speech. The typical involuntary motions of the vocal folds are brief and spasm-like (hence the term “spasmodic”), and may occasionally be difficult to recognize. This is especially true if the examination is being performed with rigid endoscopy, which requires the tongue to be pulled forward. For this reason, flexible laryngoscopy through the nose is better than rigid laryngoscopy for diagnosis of SD.

Diagnosis of SD is made from a person’s description and demonstration of the problem, and from observation of the vocal folds during voicing. There is no specific finding on any test that identifies SD. Ultimately, the diagnosis is a matter of expert opinion.

How is spasmodic dysphonia treated?

There is no definitive cure for SD. Treatment is available to improve symptoms, and fortunately, that is almost always possible. It is important to understand that treatment only aims to improve symptoms, and that choosing not to get treated does not make the disease worse.

Laryngeal injections of botulinum toxin are the main therapy for SD. Voice therapy, psychological, psychiatric, and medical treatment alone have not proven useful in controlling SD symptoms.

Botulinum toxin has been used to treat SD since 1984. The principle behind treatment is to weaken the muscles that are behind the inappropriate motion. In the case of AdSD, these are the muscles that bring the vocal folds together, and in AbSD, the muscles that bring the vocal folds apart. The injection is performed through the skin of the neck as an office procedure. Afterwards, patients can usually go on with normal activities of their day.

Over the last 30 years, many surgeons have tried to treat SD by cutting or modifying the nerve supply to the larynx, or by altering the anatomy of the larynx. Early results have been encouraging, but, for complex reasons having to do with the brain abnormality underlying dystonia, the disorder can return. Most of these surgical procedures involve some degree of irreversible destruction of laryngeal function, and may remain unable to mitigate symptoms in the long-term. Currently, surgery is a second-choice treatment, best reserved for those in whom botulinum toxin injections are not possible or ineffective. Other invasive techniques, such as laryngeal stimulation implants, have been proposed to minimize the impact of SD symptoms, but they remain investigational at this time with no definitive evidence of effectiveness.

More information can be obtained from the National Spasmodic Dysphonia Association and the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation .

Sean Parker Institute for the Voice Weill Cornell Medical College 240 E 59th Street New York, NY 10022 Map it

Spasmodic Dysphonia and Essential Vocal Tremor

Spasmodic dysphonia and essential vocal tremor are neurological voice disorders that are often misunderstood and misdiagnosed. They can be mistaken for simple voice strain. Duke laryngologists -- ear, nose, and throat (ENT) doctors who specialize in voice disorders -- and speech-language pathologists are experts in diagnosing spasmodic dysphonia and essential vocal tremor. We offer customized treatments and therapy to help you find relief.

Please check your filter options and try again.

About Spasmodic Dysphonia

Spasmodic dysphonia causes involuntary spasms of the vocal cords (also known as vocal folds). It can make your voice sound hoarse, jerky, quivering, strangled, tight, or breathy, sometimes to the point where it is difficult to speak. The vocal spasms are due to a faulty connection between a nerve and the muscle that controls your larynx (voice box).

There are two types of spasmodic dysphonia. Some people have characteristics of both.

- Abductor spasmodic dysphonia occurs when the vocal cords spasm open, which results in a breathy voice that can sound like a whisper.

- Adductor spasmodic dysphonia occurs when the vocal cords spasm shut, which causes a strained and strangled voice.

While there is currently no cure, our laryngologists and speech-language pathologists can offer a combination of proven treatments and voice therapy to alleviate and manage your symptoms.

Related Conditions and Treatments

- Voice Disorders

- Voice Evaluation

Voice Therapy

About essential vocal tremor.

Essential vocal tremor is also an involuntary voice disorder, and it can cause rhythmic voice shaking. The voice of someone with essential vocal tremor might sound labored, unstable, and as if they are nervous. Whereas spasmodic dysphonia specifically affects the vocal cords, vocal tremor can involve muscles in the throat and those used for breathing and articulation, such as the tongue, jaw, and palate. Some people may have both essential vocal tremor and spasmodic dysphonia, so accurate diagnosis by skilled voice experts is crucial to making sure you receive appropriate treatment.

Duke Health offers locations throughout the Triangle. Find one near you.

Comprehensive Evaluation

We will assess how you use your voice and what it sounds like. When spasmodic dysphonia or essential vocal tremor is suspected, your speech-language pathologist will complete a detailed evaluation of your speaking patterns, with a particular focus on the signs of spasmodic dysphonia or tremor. Your laryngologist will evaluate the role of any medical conditions that can cause voice changes, such as surgeries or recent illness. We will perform a head and neck examination and a visual examination of your voice box.

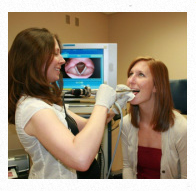

Videolaryngostroboscopy

Videolaryngostroboscopy is essential for reaching an accurate diagnosis and determining the best treatment for your voice. This detailed visual exam helps us evaluate how your vocal cords vibrate while you make sounds. A tiny camera attached to a small tube called an endoscope is inserted through your nose and allows us to see your vocal cords and larynx (voice box). A flashing strobe light simulates slow motion video, and the camera captures images of your vocal cords. The exam takes about a minute. Your nose may be sprayed with topical anesthetic for your comfort.

Botulinum Toxin (Botox) Injection

A laryngologist injects botulinum toxin (Botox) into the vocal cord through the neck or mouth. This temporarily weakens overactive vocal cord muscles to allow you to speak more easily and clearly.

If the injection approach is through the neck, a neurologist provides electromyographic (EMG) guidance. This detects electrical activity in the muscle and helps ensure accurate placement of the injection. Repeat injections are usually needed every four to six months.

If the injection approach is through the mouth, a speech-language pathologist will assist by directing an endoscope through the nose and into the throat. This allows the laryngologist to visualize the voice box and ensure accurate placement of the injection. Repeat injections are usually needed every eight to twelve weeks.

Medications

Although Botox is often considered the gold standard of treatment for spasmodic dysphonia, there are also some oral medications that can lessen the symptoms. Specific medications can also provide some relief of vocal tremor symptoms.

A speech-language pathologist guides you through vocal exercises to improve your breathing, reduce throat strain, and minimize your symptoms. Depending on the severity of your condition, voice therapy can be used alone or with Botox injections (and/or medication).

Duke University Hospital is proud of our team and the exceptional care they provide. They are why we are once again recognized as the best hospital in North Carolina, and nationally ranked in 11 adult and 10 pediatric specialties by U.S. News & World Report for 2024–2025.

Why Choose Duke

A Team of Experts Your care team will include laryngologists with advanced training and years of experience in diagnosing and treating spasmodic dysphonia and essential vocal tremor. They work closely with speech-language pathologists who are specially trained to evaluate and treat people with voice problems and have expertise in managing neurological voice disorders.

Latest Technology and Treatments We use sophisticated technology designed to enhance your treatment's accuracy and effectiveness.

Coordinated Care Because spasmodic dysphonia and essential vocal tremor are neurological conditions, we may also partner with Duke Health neurologists to ensure you receive the best therapies to minimize your symptoms and improve your voice.

Active Research to Advance Care Our ongoing research ensures you receive the best, most up-to-date care for your spasmodic dysphonia and essential vocal tremor.

The Voice Foundation

Advancing understanding of the voice through interdisciplinary research & education , philadelphia, new york, los angeles, cleveland, boston, paris, lebanon, brazil, china, japan, india , mexico.

Overview | Understanding the Disorder | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Treatment

Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) A voice disorder resulting from involuntary movements (spasms) of the voice box muscles.

Dystonia A nervous system problem that causes involuntary movement; dystonia is not a psychological problem; SD is a type of dystonia

Adductor SD (Ad-SD) Spasms in muscles that close vocal folds, which interrupt speech and cause strained or strangled voice breaks

Abductor SD (Ab-SD) Spasms in muscles that open vocal folds, which interrupt speech and cause breathy or soundless voice breaks

In Brief Spasmodic dysphonia is a voice disorder resulting from involuntary movements (or spasms) of the voice box muscles. These spasms interrupt normal voice (dysphonia) in “abrupt spurts” with a strained, strangled voice, with breathy, soundless voice, or with a mixture of both.

- Spasmodic: spasms or involuntary movements

- Dysphonia: abnormal voice

A Neurological Disease SD is a type of dystonia, a disorder of the central nervous system that causes involuntary movement of the vocal folds during voice production. SD is not a psychiatric or psychological disease. Swallowing and breathing, the other important functions of the voice box, are almost never affected.

Three Types of Spasmodic Dysphonia

Type 1 : Adductor SD (80% to 95% of cases) What Happens : Vocal folds come together (close) tightly at the wrong time during speech, making it difficult to produce voice How the Voice Sounds: Strained, strangled breaks while speaking

Type 2: Abductor SDM What Happens: Vocal folds move apart (open) at the wrong time during speech, causing air leaks How the Voice Sounds: Breathy or soundless breaks while speaking

Type 3: Mixed SD What Happens: Combination of abductor and adductor SD How the Voice Sounds: Sometimes strained, strangled breaks; sometimes breathy or soundless breaks

Unknown Cause, but Treatment Can Improve Voice Problem For spasmodic dysphonia, like all dystonias:

- The cause is unknown

- There is no specific test for diagnosis

- There is no known cure–but treatment can and does improve symptoms

Mainstay of Treatment Botulinum toxin injections into muscles of the voice box can alleviate symptoms – although relief is only temporary. Treatments are usually repeated approximately every three months.

Outlook on Treatment In almost every case of spasmodic dysphonia, symptoms can be improved with treatment.

Patient education material presented here does not substitute for medical consultation or examination, nor is this material intended to provide advice on the medical treatment appropriate to any specific circumstances.

All use of this site indicates acceptance of our Terms of Service

Now Loading

- Women's Health

- Men's Health

- Sexual Health

- Reproductive Health

- Child Health

- Healthy Living

- Mental Health

- Brain Health

- Hormonal and Metabolic Health

- Heart Health

- Cancer Care

- Skin Health

- Bone Joint and Muscle Health

- Kidney and Urinary Tract Health

- Liver Health

- Lung (Pulmonary) Health

- Digestive Disorders

- Ear Nose and Throat Health

- Infections and Infectious Diseases

- Immune Disorders and Management

- Blood Disorders

- Injuries and Poisoning

- Older People's Health

- Mouth and Dental Disorders

- Nutrition Essentials

- Health Fundamentals and Special Topics

- Drugs and Medication

- Alternative Medicine

- Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders

- Laryngeal Disorders

- Spasmodic Dysphonia

Spasmodic Dysphonia Treatment Options: Medications, Speech Therapy, and Surgery

Introduction to spasmodic dysphonia.

Spasmodic dysphonia is a voice disorder characterized by involuntary spasms or contractions of the muscles in the larynx, also known as the voice box. These spasms can cause interruptions in speech and affect the quality of the voice. The exact cause of spasmodic dysphonia is unknown, but it is believed to be related to a neurological condition. It is more common in women and typically develops between the ages of 30 and 50.

The symptoms of spasmodic dysphonia can vary in severity and may include strained or strangled speech, voice breaks or pauses, a tight or squeezed voice quality, and difficulty speaking for extended periods. These symptoms can significantly impact daily life, making it challenging to communicate effectively and causing social and emotional distress.

Seeking treatment for spasmodic dysphonia is crucial as it can help improve voice quality and alleviate the associated difficulties. While there is no cure for this condition, various treatment options are available to manage the symptoms and enhance vocal function. It is important to consult with a healthcare professional specializing in voice disorders to determine the most suitable treatment approach based on individual needs and preferences.

Medications for Spasmodic Dysphonia

Medications are one of the treatment options available for managing spasmodic dysphonia. Two common medications used for this condition are botulinum toxin injections and oral medications.

Botulinum toxin injections, such as Botox, are often the first line of treatment for spasmodic dysphonia. This medication works by temporarily paralyzing the muscles responsible for the spasms in the vocal cords. By blocking the nerve signals that cause the muscles to contract, botulinum toxin injections can help reduce muscle spasms and improve voice quality. The effects of the injections typically last for a few months, after which the treatment needs to be repeated.

While botulinum toxin injections can be effective in managing spasmodic dysphonia, they do come with potential side effects. Some common side effects include temporary breathiness, swallowing difficulties, and a weak voice. These side effects are usually temporary and resolve on their own.

Oral medications, such as anticholinergic drugs, may also be prescribed to help control the symptoms of spasmodic dysphonia. These medications work by blocking the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which is involved in muscle contractions. By reducing the activity of acetylcholine, oral medications can help relax the muscles in the vocal cords and alleviate spasms. However, the effectiveness of oral medications can vary from person to person, and they may not be suitable for everyone.

It's important to note that medications alone may not provide complete relief from spasmodic dysphonia. They are often used in combination with other treatments, such as speech therapy or surgery, to achieve optimal results. Additionally, the choice of medication and dosage should be determined by a healthcare professional based on the individual's specific needs and medical history.

Speech Therapy for Spasmodic Dysphonia

Speech therapy plays a crucial role in managing spasmodic dysphonia by helping individuals improve their voice control and reduce spasms. The goal of speech therapy is to teach patients techniques and exercises that can be used to regain control over their voice and minimize the impact of spasms.

One common technique used in speech therapy for spasmodic dysphonia is called 'voice therapy.' This technique focuses on retraining the muscles involved in voice production to reduce spasms and improve overall vocal quality. Voice therapy may involve exercises such as vocal warm-ups, relaxation techniques, and specific vocal exercises targeting the affected muscles.

Another technique used in speech therapy is 'breathing exercises.' These exercises aim to improve breath support and control, which can help reduce the severity of spasms. By learning proper breathing techniques, individuals with spasmodic dysphonia can better manage their voice and reduce strain on the vocal cords.

In addition to voice and breathing exercises, speech therapists may also use 'resonance exercises' to help individuals with spasmodic dysphonia. Resonance exercises focus on adjusting the placement of sound in the vocal tract to achieve a more balanced and controlled voice. These exercises can improve vocal resonance and reduce strain on the vocal cords.

Finding a qualified speech therapist is essential for effective management of spasmodic dysphonia. It is recommended to seek a speech therapist who specializes in voice disorders and has experience working with individuals with spasmodic dysphonia. Referrals from healthcare professionals or support groups can be helpful in finding a qualified therapist.

To maintain progress outside of therapy sessions, patients can practice the techniques and exercises taught by the speech therapist on a regular basis. Consistency is key in improving voice control and reducing spasms. Patients should also follow any additional recommendations provided by the speech therapist, such as vocal hygiene practices and lifestyle modifications.

Speech therapy, when combined with other treatment options such as medications or surgery, can significantly improve the quality of life for individuals with spasmodic dysphonia. It provides them with the tools and strategies to manage their symptoms and regain control over their voice.

Surgery for Spasmodic Dysphonia

Surgery can be considered as a treatment option for spasmodic dysphonia when other conservative measures like medications and speech therapy have not provided satisfactory results. One surgical procedure that has shown promise in treating spasmodic dysphonia is selective laryngeal denervation-reinnervation (SLDR) surgery.

SLDR surgery aims to rewire the nerves responsible for vocal cord movement in order to reduce spasms and improve voice quality. During the procedure, the surgeon identifies the nerves causing the spasms and selectively denervates them. Then, the denervated muscles are reinnervated with nerves from other areas of the body, such as the neck or chest, which are not affected by spasmodic dysphonia.

The goal of SLDR surgery is to restore more normal nerve function and reduce the severity of spasms. However, it is important to note that this surgery is not a cure for spasmodic dysphonia and may not completely eliminate symptoms.

Like any surgical procedure, SLDR surgery carries potential risks. These may include infection, bleeding, damage to surrounding structures, and changes in voice quality. It is crucial for patients to have a thorough discussion with their healthcare provider about the potential benefits and risks of surgery before making a decision.

The recovery process after SLDR surgery can vary from patient to patient. Some individuals may experience immediate improvement in voice quality, while others may require a period of adjustment. It is common to experience temporary hoarseness or changes in voice following surgery, but these usually resolve over time.

In conclusion, surgery, specifically SLDR surgery, can be an option for individuals with spasmodic dysphonia who have not found relief with other treatments. It aims to rewire the nerves responsible for vocal cord movement and reduce spasms. However, it is important to carefully consider the potential risks and benefits of surgery and have realistic expectations about the outcomes. Consulting with a qualified healthcare professional is essential in making an informed decision about surgical intervention for spasmodic dysphonia.

Frequently asked questions

Anton Fischer

Related articles, view all articles, understanding spasmodic dysphonia: causes, symptoms, and treatment options, living with spasmodic dysphonia: coping strategies and support, how to diagnose spasmodic dysphonia: tests and evaluation, tips for managing spasmodic dysphonia symptoms in everyday life, spasmodic dysphonia in children: signs, diagnosis, and treatment, the link between spasmodic dysphonia and anxiety: understanding the connection, natural remedies for soothing vocal cord contact ulcers, tips for vocal health: preventing and managing vocal cord polyps, laryngitis vs. pharyngitis: what's the difference, surgical options for vocal cord paralysis: what you need to know, laryngitis and acid reflux: understanding the connection, causes of laryngitis: understanding the common triggers, best authors.

Recent articles

Exploring career opportunities with relaxation techniques certification, how to maintain certification in relaxation techniques, certification options for different relaxation techniques, the role of training in enhancing relaxation techniques skills, is certification necessary for practicing relaxation techniques, what to expect from a relaxation techniques training course.

- Billing Information

- Community Engagement

- Emory Clinic

- Insurance Information

- Medical Records

- Medical Professionals

- News & Media

- Patient Portal

- Patients & Visitors

- Find a Provider

- Find a Location

- Centers & Programs

- ACL Program

- Adult Psychiatry

- Bariatric Centers & Weight Loss

- Brain Health

- Digestive Diseases

- Employer Health Solutions

- Joint & Cartilage Preservation Center

- Endocrinology

- General Surgery

- Heart & Vascular

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Laboratories

- Mental Health Services

- Obstetrics & Prenatal Care

- Orthopaedics, Sports & Spine

- Physical Therapy & Rehabilitation

- Primary Care (Family, Internal, Geriatrics)

- Radiology & Imaging

- Reproductive Health

- Sleep Center

- Transgender Care

- Urgent Care

- Vein Center

- Veterans Program

- Clinical Trials

- Financial Assistance

- Financial Clearance Policy

- Guest Services

- Language Interpretation Services

- LGBTQIA Cultural Competency

- Medicare Resources

- Mission & Values

- MyChart Patient Portal Help

- No Suprises Act Disclosure

- Non-Discrimination Policy

- Online Bill Pay

- Patient Privacy & Rights

- Patient Relations

- Price Transparency

- Visitor Policy

- Advanced Practice Provider Opportunities

- Nursing Opportunities

- View All Open Opportunities

- Benefits That Matter

- Emory Healthcare Communities

- Emory Healthcare Team Members Log In

- Nursing Residency

- Working at Emory

Spasmodic Dysphonia

Anatomy of the condition.

Dystonia is a neurological disorder which causes involuntary muscle movements. Spasmodic dysphonia is a form of dystonia. It produces involuntary spasms of the vocal folds, causing disordered speech.

There are two typical forms of spasmodic dysphonia:

- Adductor type is the most common form of spasmodic dysphonia. Abrupt, involuntary contraction of the muscles that bring the vocal folds together cause this type. It causes closure of the vocal folds. This causes broken, strained speech and a tight quality to the voice.

- Abductor type is the less common form of spasmodic dysphonia. It happens when involuntary contractions in the muscles that open the vocal folds let air escape suddenly. This causes breathy, whispery voice breaks.

There are other, less common, forms of spasmodic dysphonia. These include a combination of the two types.

Causes or Contributing Factors

Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) has no known cause. Many physicians believe a neurological disorder causes SD. Abnormal functioning of the basal ganglia structure in the brain would be to blame. Onset occurs without warning or explanation. Spasmodic dysphonia is more prevalent in women and among people between ages 40 and 50.

A halting, interrupted voice pattern is the key symptom for the adductor variety of SD. With the abductor type of SD, the voice has breathy voice breaks. When patients with SD try to control spasms, we often hear a tight or constricted sounding voice. Symptoms may improve or worsen, depending on the time of day.

The condition is hard to diagnose and is frequently misdiagnosed. the disease often mimics other conditions or speech patterns. appropriate diagnosis requires a thorough examination by an experienced team of voice specialists..

There is not a definitive test for the condition. Diagnosis depends on a combination of symptoms and evaluation by the clinical voice team.

Non-Operative Treatments

Botox offers one of the most effective treatments for spasmodic dysphonia. the drug softens and weakens vocal muscles, diminishing spasms. this treatment also reduces voice wispiness from the abductor form of the disease..

The results of Botox may vary, but the drug normally takes effect 24-48 hours after the injections. First, the voice becomes soft and breathy for a period of several days to two weeks. Then the voice should get stronger and stronger, with fewer spasms. The duration of the effect varies. Most patients see relief for three to four months before needing the next injection.

Because Botox weakens vocal muscles, an initial side effect may be difficulty swallowing. Our speech pathologists can usually train the patient in alternative swallowing techniques.

Voice relaxation techniques and other speech therapies may help reduce symptoms.

Operative Treatments

In some instances, we may recommend surgery. selective laryngeal adductor denervation reinnervation is a new surgical option. our surgeon divides the nerves to the muscles, which brings the vocal folds together. alternate neural tissue is then used to lessen the symptoms of spasmodic dysphonia., related care at emory.

- View Voice Center

Emory Healthcare news from the Emory News Center

- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

Driven to discover how the brain controls movement

School of Kinesiology

Human Sensorimotor Control Laboratory

- Proprioception and Vibro-Tactile Stimulation In Larnygeal and Cervical Dystonia

- Proprioception in Stroke

- Proprioceptive Dysfunction in Adult and Pediatric Populations

- Proprioceptive Dysfunction and Training in Parkinson's Disease

- Robotic Neurorehabilitation

- Effects of Cerebellar Dysfunction on Motor Control

- Industry Collaborations

- Publications

- Prospective Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Research Assistant

- Center for Clinical Movement Science

- Directions to Lab

Laryngeal Vibration as a Treatment for the Voice Disorder Spasmodic Dysphonia

Laryngeal Dystonia (LD) - also called spasmodic dysphonia - is a voice disorder that leads to strained or choked speech. Current therapeutic options for treating LD are very limited. LD does not respond to conventional speech therapy and is treated primarily with Botulinum toxin injections to provide temporary symptom relief. There is no cure for LD.

Vibro-tactile stimulation to treat the voice symptoms of LD

Vibro-tactile stimulation (VTS) is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique that our laboratory developed for people with LD. In a first study, supported by the National Institutes of Health, our team documented that a one-time 30-minute application of VTS over the laryngeal area can result in measurable improvements in the voice quality of people with LD. The effects of VTS are very immediate, that is, can happen within minutes. We could show that LD is associated with atypical patterns of cortical activity during voice production: (1) a reduced movement-related desynchronization of motor cortical networks, (2) an excessively large synchronization between left somatosensory and premotor cortical areas. We could further demonstrate that VTS induced a significant suppression of theta band power over the left somatosensory-motor cortex and a significant rise of gamma rhythm over right somatosensory-motor cortex . That is, there is a fast neural response to VTS observable in brain areas involved in speech production. These results have been published in the journals Clinical Neurophysiology and Scientific Reports .

A clinical trial to assess the longitudinal effects of VTS

In a second research study also funded by the National Institutes of Health, we investigated systematically the possible longer-term benefits of this approach for improving the voice symptoms of people with LD. Study participants administered VTS at home for up to 8 weeks. In addition, researchers assessed their voice quality and monitored the corresponding neurophysiological changes in the brain using electroencephalography in the laboratory at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of the VTS in-home training. The main findings were that up to 57% of participants showed a meaningful improvement in an objective voice measure (Cepstral Peak Power) or a reduction in perceived voice effort . These results inform patients and clinicians about the possible impact of this therapeutic approach. It promotes the development of wearable VTS devices that would enlarge the available therapeutic arsenal for treating voice symptoms in LD. The first findings of this longitudinal study are published in the open-access journal Frontiers of Neurology .

This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03746509

Note: This clinical trial has stopped recruiting new participants.

Determining the usability of in-home application of laryngeal VTS

This study aims to get insights in how people with laryngeal dystonia can use our vibration device at home over a 2-month period. Participants follow a specific study protocol where they increased the weekly dosage of VTS over a period of 4 weeks. Participants monitored the changes in their voice and recorded their user experience. One cohort of participants taped the vibrators to the skin, while the second cohort used a wearable collar with embedded vibrators to apply laryngeal VTS.

This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov ID : NCT06111027 .

Some testimonials from study participants

When I received the vibration I noticed that it elongated the effects of the Botox I received. I did not need to return as often to my otolaryngologist for injections. K.B.

I found the VTS to be beneficial in helping to alleviate some of my SD symptoms. Further funding is necessary to develop a practical device that can be of help to other SD patients and offer an alternative to the typical Botox injections. I will be first in line to test this new VTS collar. C.M.

Life with ABSD is very challenging and extremely debilitating but having hope that there will be something to improve our situation could mean all the difference in the world. R.C.

If you want to stay updated on the latest progress, please sign up through this link: https://z.umn.edu/SDSignUp

Team members

Other members of the interdisciplinary research team include Dr. Peter Watson , a voice disorder specialist, and Dr. Yang Zhang , an expert in the analysis of cortical activity during speech. Both are faculty in the U of M Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences. Dr. George Goding from Otolaryngology represents the clinical partner in the team. He is an expert in LD and treats these patients regularly in the U of M Lion’s Voice Clinic. Dr. Divya Bhaskaran, Dr. Naveen Elangovan, and other members from HSCL complement the team.

Contact information

Dr. Jürgen Konczak, Ph.D. is the principal investigator of these studies. You can contact him at [email protected] . Ms. Shima Amini is the clinical research coordinator. She can be reached at [email protected] .

Watch webinar from Dysphonia International

- What’s Wrong with My Voice?

- How Your Voice Works

- Amplification Systems

- Type-to-Talk

- Operator-Assisted

- Personal Impact

- Relationships

- Socializing

- Self-Esteem

- Managing Stress

- Public Speaking

- Building Sensitivity

- Voice and the Workplace

- Profiles of Strength

- Causes of Voice Conditions

- Spasmodic Dysphonia

- Muscle Tension Dysphonia

- Vocal Tremor

- Vocal Cord Paralysis

- Respiratory Dystonia

- Onset and Diagnosis

- Types of SD

- Causes of SD

- Dystonia and SD

- Voice Therapy

- Botulinum Toxin Injections

- SLAD-R Surgery

- Type II Thyroplasty

- Thyroarytenoid Myectomy or Myoneurectomy

- Medications

- Other Treatment Options

- Living with SD

- Find a Voice Expert

- Future Treatments

- Healthcare Referral Directory

- Join/Update Healthcare Information

- Find Support

- Research Funding

- Participate in Research

- Brain Donation

- Research Travel Awards

- Global Dystonia Registry

- Published Research

- Calendar of Events

- Walk for Talk

- World Voice Day

- Guest Speaker Program for SLP Students

- Podcast Program

- Planned Giving – Legacy Society

- Workplace Giving

- Our Mission and Vision

- Our Leadership

- Our History

- Fiscal Information

- Award Recipients

- In Memoriam

Diagnosis of Spasmodic Dysphonia

Progression from symptom onset to the diagnosis of spasmodic dysphonia.

People with spasmodic dysphonia initially notice either a gradual or sudden onset of difficulty in speaking. They may hear breaks in their voice during production of certain words or speech sounds, breathy-sounding pauses on certain words or sounds, or a tremulous shaking of the voice. They may feel that talking requires more effort than before. Often people say that their voice sounds as if they “have a cold or laryngitis.”

The symptoms of SD can vary from mild to severe. A person’s voice can sound strained, tight, strangled, breathy, or whispery. The spasms often interrupt the sound, squeezing the voice to nothing or dropping it to a whisper. Just like with any health issue, stress can worsen the symptoms, but it is not the cause of them.

Onset is usually gradual with no obvious explanation. Symptoms occur in the absence of any structural abnormality of the larynx, such as nodules, polyps, carcinogens, or inflammation. People have described their symptoms as worsening over an approximate 18-month period and then remaining stable in severity from that point onward. Some people have reported brief periods of remission, however this is very rare and the symptoms usually return.

Getting a proper diagnosis-where to start

Spasmodic dysphonia can be difficult to diagnose because the anatomy of the larynx is normal. SD has no objective pathology that is evident through x-rays or imaging studies like a CT or MRI scan, nor can a blood test reveal any particular fault. In addition, several other voice disorders may mimic or sound similar to it.

The excessive strain and misuse of muscle tension dysphonia (MTD), the harsh strained voice of certain neurological conditions, the weak voice symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, certain psychogenic voice problems, acid reflux, or voice tremor are often confused with SD. Therefore, the best way to diagnose the problem is to find an experienced clinician with a good ear.

Getting a diagnosis can be a team effort. This is why it is important to prepare before you visit your physician and be prepared to communicate effectively. Don’t hesitate to ask any questions needed in order to fully understand your diagnosis. This applies to dealing with your initial diagnosis, the frustrations of treating your SD, and how to effectively cope.

Visiting Your Primary Care Doctor

Your visit with your primary care doctor may be frustrating. There are so many causes of vocal issues that it may require the approach of ruling out other things before settling on the correct diagnosis or being sent to a specialist. Take a list of questions to your doctor — When you are dealing with this new diagnosis it is easy to become overwhelmed and forget what you wanted to ask. Writing out your list can help. Start by prioritizing your questions and ask the questions that are most important to you first. As you ask questions and think of additional questions, jot down the new ones at the bottom of your list. Questions to ask: 1. What do you think is causing my problem? 2. What is my diagnosis? 3. Is there more than one condition that could be causing or contributing to my problem? 4. Since there are so many causes for voice issues , how certain are you with regard to this diagnosis. 5. Do I need to seek input from any other medical professionals like and ENT? If you are referred to an ENT, it would be best to seek out one that has experience with voice issues.

Visiting an Otolaryngologist (ENT)

Seek out an Ear Nose and Throat (ENT) doctor, or otolaryngologist, that has experience with voice issues or specializes in voice issues. You may be referred to a subspecialist called a laryngologist. Laryngology is a subspecialty within otolaryngology (ear, nose, and throat) that deals with disorders of voice, airway and swallowing. Through postgraduate fellowship training, a laryngologist has special expertise in the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to problems in these areas. This way you have a physician focused on the voice who can help get your voice issue diagnosed quickly. Check out our healthcare referral list to find someone who specializes in voice disorders. Suggested List of Questions: 1. What test will you do to diagnose the problem? How accurate is the test at diagnosing my problem? Are there other diagnostic tools available that would confirm the diagnosis? 2. Upon diagnosis, ask what is the likely course of this condition? 3. What is the most conservative approach to try first? What happens if this treatment does not work? 4. Will treatment affect the long-term outlook? 5. How will I know when I have reached my plateau? 6. What changes will I need to make? 7. What organizations/resources are available to help me with making these changes? 8. Where can I find information about clinical trials/research being conducted on SD? 9. Is there a chance that anyone else in my family may get this condition? 10. What tools are available that will help me with the tasks that are difficult for me (voice amplifiers, telephones)? 11. Are my symptoms “normal?” What if I have atypical symptoms? Do I know when a symptom is not SD? 12. Long-term outlook: Does SD progress in severity? Will it go into remission? Will treatments affect the progression? Take a companion with you to take notes – — Bringing someone for support will allow you to focus on asking the questions and understanding the answers without the pressure of having to remember every detail. Afterwards you can review the information to make sure your understanding matches that of your companion. You can also ask your doctor to send you a copy of your evaluation results and the recommended treatment options for you to review.

Visiting an Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP)

A Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) can help manage symptoms and is often used in conjunction with an ENT to confirm diagnosis. They will: 1. Work with spasms/tremor, not suppress them 2. Improve the ease and quality of voice production 3. Increase the awareness and ability to manage vocal variations An SLP will create an individualized plan, and work on techniques such as breathing control, which involves maintaining a steady flow of air from the lungs during voice production, relaxation, and pitch and loudness modifications can help improve the person’s voice. Questions to ask: 1. What can I expect from voice therapy? 2. How long should we try this before quitting? 3. Why do I need voice therapy? 4. How many SD patients have you worked with? 5. If voice therapy is working, does that mean I do not have SD? 6. Will I be able to sing (or whatever you are concerned about) again? 7. Should I use voice amplification devices? In addition, voice therapy should be considered when a person has Muscle Tension Dysphonia (MTD) along with SD. Click here to find an SLP in our Healthcare Referral Database

Visiting a Neurologist

Since some voice disorders like SD have a neurological component, an appointment with a neurologist that focuses on movement disorders, will help determine if there is a neurological component present.

What to expect during the exam

After taking the medical history, your medical professional will listen carefully to your speech to identify specific signs of SD, such as voice breaks. To help differentiate the condition and sub-type, they often ask the patient to read and speak specific phrases and sentences loaded with certain types of sounds. While additional evaluations may help to determine the diagnosis, often times, the experienced clinician expert’s perceptual analysis usually serves as the basis for making the SD diagnosis.

The physical examination continues by looking at the larynx in action. Even though the person with SD often has a normal anatomy, the physician should look at the larynx to rule out other common laryngeal disorders that can result in a hoarse voice. These include a wide variety of conditions that range from benign issues such as vocal cord nodules or polyps, to more concerning conditions such as vocal cord cancer.

One way to view the larynx is to insert a rigid endoscope, a straight, narrow metal rod containing a variety of lenses, through the mouth and toward the back of the throat while the person is saying “eeeee.” In this manner, the otolaryngologist obtains a close-up view of the structures of the larynx and the movement of the vocal folds.

Another common approach to viewing the vocal folds involves the use of a flexible endoscope. In this method, a very narrow, flexible tube with a lens is inserted through one nostril, around the back of the nose and down through the throat. This allows the doctor to evaluate the movements of the larynx while the person is speaking or singing.

Usually these endoscopic examinations are performed with a specialized flickering light called a “stroboscope,” which allows the clinician to further evaluate the rapid fine movement of the vocal folds. These evaluations can be recorded for both the clinician and patient to review after the examination.

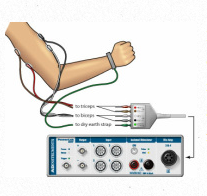

In addition to these tests, the otolaryngologist may recommend a laryngeal electromyography (EMG) test to obtain specific information about the specific muscles involved. The EMG test involves inserting a thin needle electrode through the neck into the muscles of the larynx and evaluating the electrical activity of the muscles at rest and during speaking. While some fine the EMG helpful, there are no specific types of signals that are diagnostic of only SD. With a confirmed diagnosis, the doctor can work with you to find the best course of treatment for your symptoms.

Once a diagnosis of SD is made, you should continue to take an active role in your health care. Ask questions, record the answers, get second opinions when necessary, and become fully educated about the condition and the treatment options.

Spasmodic dysphonia is estimated to affect approximately 50,000 people in North America, but this number may be inaccurate due to ongoing misdiagnosis or undiagnosed cases of the disorder. Although it can start at any time during life, SD seems to begin more often when people are middle-aged. The disorder affects women more often than men.

Image source: https://spasmodicdysphoniawku.weebly.com/evaluation.html

By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Voice Therapy Exercises Voice and/or speech therapy is one of the management options for people with spasmodic dysphonia. It can be used alone or in conjunction with treatments such as botulinum toxin injections or pre/post -surgical intervention. Voice therapy can also help with

• Always work with a speech language pathologist who is a specialized voice therapist to do techniques correctly • Engage in relaxation techniques and exercises for destressing and calming not only the mind, but decreasing tension in the body ... symptoms, not to cure a neurological disorder like spasmodic dysphonia or tremor. They

Spasmodic dysphonia is a long-term, or chronic, voice disorder. With spasmodic dysphonia, or SD, your vocal folds do not move like they should. They spasm or tighten when you talk. Your voice may sound jerky, shaky, hoarse, or tight. You may have times when you cannot make any sounds at all. You may also have times when your voice sounds normal.

Voice therapy usually lasts for 6-8 sessions over 8-10 weeks. Key elements in this treatment include reduction of excessive strain during speech, strategies for difficult speaking situations such as the phone, and education about the disorder and its effects. Voice therapy can provide a sense of control when individuals with SD better ...

Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) is a lifelong condition characterized by involuntary spasms of the vocal folds within the voice box, causing voice breaks and vocal tremors that may worsen over time. Voice characteristics include voice breaks, tremors, and strain, creating an often choppy, breathy, or shaky quality. This voice problem typically occurs ...

Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) A voice disorder resulting from involuntary movements (spasms) of the voice box muscles. Dystonia. A nervous system problem that causes involuntary movement; dystonia is not a psychological problem; SD is a type of dystonia. Adductor SD (Ad-SD) Spasms in muscles that close vocal folds, which interrupt speech and cause ...

Voice exercises for Spasmodic Dysphonia (SD) are a vital component of managing this challenging voice disorder. These exercises are designed to address the specific vocal challenges associated with SD and help individuals regain control over their voice. Whether you have abductor or adductor SD, voice exercises can be tailored to your unique needs.

What is spasmodic dysphonia?Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) is a type of dystonia, a neurologic disease that causes involuntary movements. There are two main types of SD. Adductor SD (AdSD) causes the vocal folds to come together (adduct) inappropriately during voicing, and makes up about 85-90% of SD cases. Abductor SD (AbSD), on the other hand, makes the vocal folds come apart

What is Spasmodic Dysphonia? Spasmodic dysphonia (also known as laryngeal dystonia) is a movement disorder featuring involuntary contrac-tions of the vocal cord muscles. These contractions may result in patterned "breaks" or interruptions in speech, or may give a breathy quality to the voice. Most cases of spasmodic dysphonia develop in adults.

Adductor spasmodic dysphonia occurs when the vocal cords spasm shut, which causes a strained and strangled voice. While there is currently no cure, our laryngologists and speech-language pathologists can offer a combination of proven treatments and voice therapy to alleviate and manage your symptoms.

vocal tract exercise that utilizes a straw or tube to increase subglottic pressure and ease secondary symptoms to dysphonia. Straw phonation is a cost - ... Patient reported benefit of the efficacy of speech therapy in dysphonia.Clinical Otolaryngology & Allied Sciences,23(3), 284. Meerschman, I., Van Lierde, K., Peeters, K., Meersman, E ...

Spasmodic dysphonia is a voice disorder resulting from involuntary movements (or spasms) of the voice box muscles. These spasms interrupt normal voice (dysphonia) in "abrupt spurts" with a strained, strangled voice, with breathy, soundless voice, or with a mixture of both. Spasmodic: spasms or involuntary movements. Dysphonia: abnormal voice.

Speech therapy plays a crucial role in managing spasmodic dysphonia by helping individuals improve their voice control and reduce spasms. The goal of speech therapy is to teach patients techniques and exercises that can be used to regain control over their voice and minimize the impact of spasms.

Spasmodic dysphonia, or laryngeal dystonia, is a disorder affecting the voice muscles in the larynx, also called the voice box. When you speak, air from your lungs is pushed between two elastic structures—called vocal folds—causing them to vibrate and produce your voice. In spasmodic dysphonia, the muscles inside the vocal folds spasm (make ...

Dysphonia International | 300 Park Boulevard | Suite 175 | Itasca, IL 60143 | 630-250-4504 | [email protected]

This causes broken, strained speech and a tight quality to the voice. Abductor type is the less common form of spasmodic dysphonia. It happens when involuntary contractions in the muscles that open the vocal folds let air escape suddenly. This causes breathy, whispery voice breaks. There are other, less common, forms of spasmodic dysphonia.

vocal tremor, spasmodic dysphonia, or. vocal fold paralysis. Functional —voice disorders that result from inefficient use of the vocal mechanism when the physical structure is normal, such as. vocal fatigue, muscle tension dysphonia or aphonia, diplophonia, or. ventricular phonation. Voice quality can also be affected when psychological ...

Laryngeal Dystonia (LD) - also called spasmodic dysphonia - is a voice disorder that leads to strained or choked speech. Current therapeutic options for treating LD are very limited. LD does not respond to conventional speech therapy and is treated primarily with Botulinum toxin injections to provide temporary symptom relief. There is no cure for LD.

Medical Treatment and Speech Therapy for Spasmodic Dysphonia: A Literature Review. Audiologists. Speech-Language Pathologists. Academic & Faculty. Audiology & SLP Assistants. Students. Public. Home / Evidence Maps. This literature review investigates the use of medical and/or speech interventions in individuals with spasmodic dysphonia.

When a person with SD attempts to speak, involuntary spasms in the tiny muscles of the larynx cause the voice to break up, or sound strained, tight, strangled, breathy, or whispery. The spasms often interrupt the sound, squeezing the voice to nothing in the middle of a sentence, or dropping it to a whisper. People have described their symptoms ...

Discover what speech therapy entails, its benefits, and who may benefit from it. ... or volume. The main types of voice disorders include laryngitis, spasmodic dysphonia, and vocal cord paresis. ... A person with cognitive-communication disorder can be treated using exercises to retrain discrete cognitive processes such as attention, using ...

People with spasmodic dysphonia initially notice either a gradual or sudden onset of difficulty in speaking. They may hear breaks in their voice during production of certain words or speech sounds, breathy-sounding pauses on certain words or sounds, or a tremulous shaking of the voice. They may feel that talking requires more effort than before.