- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G39 - Other

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H42 - Publicly Provided Private Goods

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H74 - State and Local Borrowing

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K11 - Property Law

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L83 - Sports; Gambling; Recreation; Tourism

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M40 - General

- M41 - Accounting

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Blog Series

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Review of Corporate Finance Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, 1. what happened and when, 2. cause and effect: the causes of the crisis and its real effects, 3. was this a liquidity crisis or an insolvency/counterparty risk crisis, 4. the real effects of the crisis, 5. the policy responses to the crisis, 6. conclusion, the financial crisis of 2007–2009: why did it happen and what did we learn.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Anjan V. Thakor, The Financial Crisis of 2007–2009: Why Did It Happen and What Did We Learn?, The Review of Corporate Finance Studies , Volume 4, Issue 2, September 2015, Pages 155–205, https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfv001

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This review of the literature on the 2007–2009 crisis discusses the precrisis conditions, the crisis triggers, the crisis events, the real effects, and the policy responses to the crisis. The precrisis conditions contributed to the housing price bubble and the subsequent price decline that led to a counterparty-risk crisis in which liquidity shrank due to insolvency concerns. The policy responses were influenced both by the initial belief that it was a market-wide liquidity crunch and the subsequent learning that insolvency risk was a major driver. I suggest directions for future research and possible regulatory changes.

In its analysis of the crisis, my testimony before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission drew the distinction between triggers and vulnerabilities. The triggers of the crisis were the particular events or factors that touched off the events of 2007–2009—the proximate causes, if you will. Developments in the market for subprime mortgages were a prominent example of a trigger of the crisis. In contrast, the vulnerabilities were the structural, and more fundamental, weaknesses in the financial system and in regulation and supervision that served to propagate and amplify the initial shocks. Chairman Ben Bernanke, April 13, 2012 1 1 Bernanke, B. S. “Some Reflections on the Crisis and the Policy Response.” Speech at the Russell Sage Foundation and the Century Foundation Conference on “Rethinking Finance,” New York, April 13, 2012.

Financial crises are a centuries-old phenomena (see Reinhart and Rogoff 2008 , 2009 , 2014 ), and there is a substantial literature on the subject (e.g., Allen and Gale 1998 , 2000 ; Diamond and Dybvig 1983 ; Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny 2015 ; Gorton 2010 ; Thakor forthcoming ). Despite this familiarity, the financial crisis of 2007–2009 came as a major shock that is widely regarded as the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression of the 1930s, and rightly so. The crisis threatened the global financial system with total collapse, led to the bailouts of many large uninsured financial institutions by their national governments, caused sharp declines in stock prices, followed by smaller and more expensive loans for corporate borrowers as banks pulled back on their long-term and short-term credit facilities, and caused a decline in consumer lending and lower investments in the real sector. 2 For a detailed account of these events, see the excellent review by Brunnermeier (2009) .

Atkinson, Luttrell, and Rosenblum (2013) estimate that the financial crisis cost the United States an estimated 40% to 90% of one year’s output, an estimated $6 to $14 trillion, the equivalent of $50,000 to $120,000 for every U.S. household. Even these staggering estimates may be conservative. The loss of total U.S. wealth from the crisis—including human capital and the present value of future wage income—is estimated in this paper to be as high as $15 to $30 trillion, or 100%–190% of 2007 U.S. output. The wide ranges in these estimates reflect uncertainty about how long it will take the output of the economy to return to noninflationary capacity levels of production.

As Lo (2012) points out, we do not have consensus on the causes of the crisis. This survey discusses the various contributing factors. I believe that a combination of global macroeconomic factors and U.S. monetary policy helped to create an environment in which financial institutions enjoyed a long period of sustained profitability and growth, which elevated perceptions of their skills in risk management (see Thakor 2015a ), possibly increased bullishness in a non-Bayesian manner (e.g., Gennaioli, Shleifor, and Vishny 2015 ), and encouraged financial innovation. The financial innovation was driven by advances in information technology that helped make all sorts of securities marketable, spurred the growth of the subprime mortgage market, and made banking more intertwined with markets (see Boot 2014 ; Boot and Thakor 2014 ).

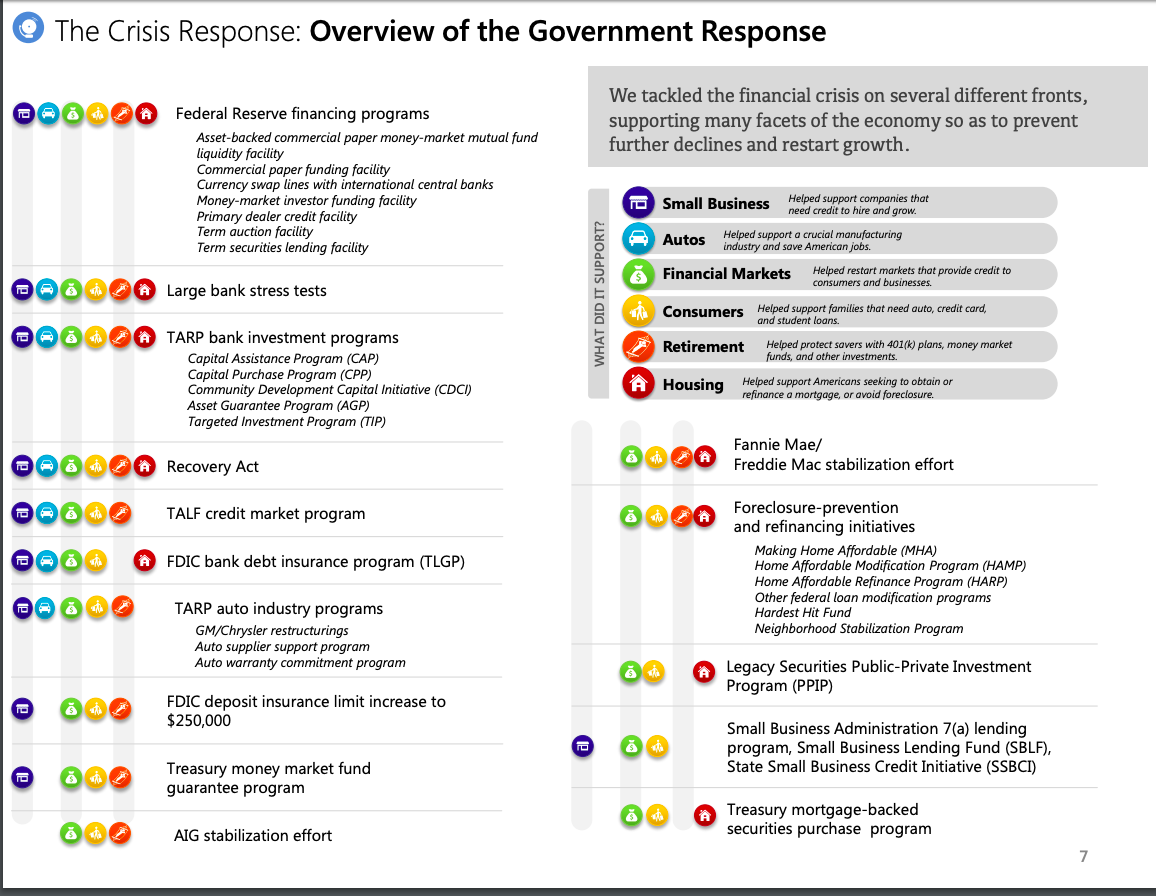

These innovative securities led to higher risks in the industry, 3 and eventually these risks led to higher-than-expected defaults, causing the securities to fall out of favor with investors, precipitating a crisis (e.g., Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny 2012 ). The early signs of the crisis came in the form of withdrawals by investors/depositors and sharp increases in risk premia and collateral requirements against secured borrowing. These developments were interpreted by U.S. regulators and the government as indications of a market-wide liquidity crisis, so most of the initial regulatory and government initiatives to stanch the crisis took the form of expanded liquidity facilities for a variety of institutions and ex post extension of insurance for (a prior uninsured) investors. As the crisis continued despite these measures, there was growing recognition that the root cause of the liquidity stresses seemed to be counterparty risk and institution-specific insolvency concerns linked to the downward revisions in the assessments of the credit qualities of subprime mortgages and many asset-backed securities. This then led to additional regulatory initiatives targeted at coping with counterparty risk. It is argued that some of the government initiatives—despite their temporary nature and their effectiveness—have created the expectation of future ad hoc expansions of the safety net to uninsured sectors of the economy, possibly creating various sorts of moral hazard going forward. This crisis is thus a story of prior regulatory beliefs about underlying causes of the crisis being heavily influenced by historical experience (especially the Great Depression that many believe was prolonged by fiscal tightening by the government and inadequate liquidity provision by the central bank), 4 followed by learning that altered these beliefs, and the resulting innovations in regulatory responses whose wisdom is likely to be the subject of ongoing debate and research.

All of these policy interventions were ex post measures to deal with a series of unexpected events. But what about the ex ante regulatory initiatives that could have made this crisis less likely? The discussion of the causal events in Section 2 sheds light on what could have occurred before 2006, but a more extensive discussion of how regulation can enhance banking stability appears in Thakor (2014) . In a nutshell, it appears that what we witnessed was a massive failure of societal risk management, and it occurred because a sustained period of profitable growth in banking created a false sense of security among all; the fact that banks survived the bursting of the dotcom bubble further reinforced this belief in the ability of banks to withstand shocks and survive profitably. This led politicians to enact legislation to further the dream of universal home ownership that may have encouraged risky bank lending to excessively leveraged consumers. 5 Moreover, it caused banks to operate with less capital than was prudent and to extend loans to excessively leveraged consumers, caused rating agencies to underestimate the true risks, and led investors to demand unrealistically low risk premia. Two simple regulatory initiatives may have created a less crisis-prone financial system—significantly raising capital requirements in the commercial and shadow banking systems during the halcyon precrisis years and putting in place regulatory mechanisms—either outright proscriptions or price-based inducements—to ensure that banks focused on originating and securitizing only those mortgages that involved creditworthy borrowers with sufficient equity. This is perhaps twenty-twenty hindsight, but some might even dispute that these are the right conclusions to draw from this crisis. If so, what did we really learn?

There is a sense that this crisis simply reinforced old lessons learned from previous crises and a sense that it revealed new warts in the financial system. Reinhart and Rogoff’s (2009) historical study of financial crises reveals a recurring pattern—most financial crises are preceded by high leverage on the balance sheets of financial intermediaries and asset price booms. Claessens and Kodres (2014) identify two additional “common causes” that seem to play a role in crises: financial innovation that creates new instruments whose returns rely on continued favorable economic conditions (e.g., Fostel and Geanakoplos 2012 ), and financial liberalization and deregulation. Given that these causes go back centuries, one must wonder whether, as a society, we simply do not learn or whether the perceived benefits of the precrisis economic boom are deemed to be large enough to make the occasional occurrence of crises one worth bearing.

Numerous valuable new lessons have emerged as well—insolvency and counterparty risk concerns were primary drivers of this crisis, the shadow banking sector was highly interconnected with the banking system and thus a major influence on the systemic risk of the financial system, high leverage contributes to an endogenous increase in systemic risk (especially when it occurs simultaneously on the balance sheets of consumers as well as financial institutions), and piecemeal regulation of depository institutions in a highly fragmented regulatory structure that leaves the shadow banking system less regulated makes it easy for financial institutions to circumvent microprudential regulation and engage in financial innovation, some of which increases systemic risk. Moreover, state and federal regulators implement similar regulations in different ways (see Agarwal et al. 2014 ), adding to complexity in the implementation of regulation and elevating uncertainty about the responses of regulated institutions to these regulations. And, finally, compensation practices and other aspects of corporate culture in financial institutions may have encouraged fraud (see Piskorski, Seru, and Witkin forthcoming ), adding another wrinkle to the conditions that existed prior to the crisis.

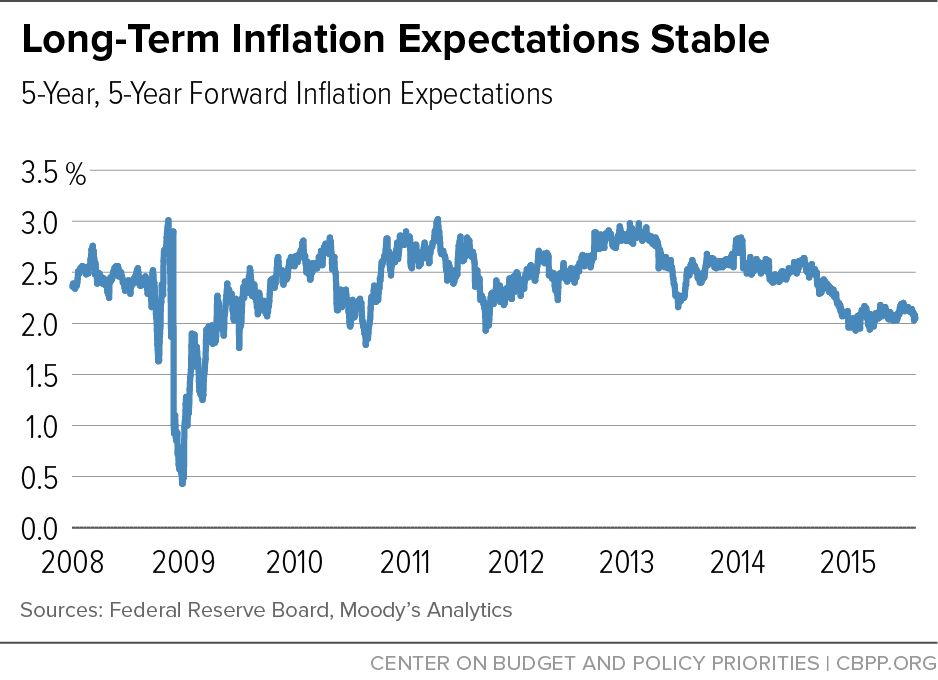

However, it is also clear that our learning is far from complete. The pursuit of easy-money monetary policies in many countries seems to reflect the view that liquidity is still a major impediment and that these policies are needed to facilitate continued growth-stimulus objectives, but it is unlikely that such policies will help allay concerns about insolvency and counterparty risks, at least as a first-order effect. The persistence of low-interest rate policies encourage banks to chase higher yields by taking higher risks, thereby increasing the vulnerability of the financial system to future crises. And the complexity of regulations like Dodd-Frank makes the reactions of banks—that seek novel ways to lighten their regulatory burden—to these regulations more uncertain. All this means that some of the actions of regulators and central banks may inadvertently make the financial system more fragile rather than less.

This retrospective look at the 2007–2009 crisis also offers some ideas for looking ahead. Three specific ideas are discussed in Section 5 and previewed here: First, the research seems to indicate that higher levels of capital in banking would significantly enhance financial stability, with little, if any, adverse impact on bank value. However, much of our research on this issue is qualitative and does not lend itself readily to calibration exercises that can inform regulators how high to set capital requirements. The section discusses some recent research that has begun to calculate the level of optimal capital requirements. We need more of this kind of research. Second, there needs to be more normative research on the optimal design of the regulatory infrastructure. Most research attention has been focused on the optimal design of regulations, but we need more research on the kinds of regulatory institutions needed to implement simple and effective regulations consistently, without the tensions created by multiple regulators with overlapping jurisdictions. Third, beyond executive compensation practices, 6 we have virtually no research on culture in banking. 7 Yet, managerial misconduct—whether it is excessive risk taking or information misrepresentation to clients—is a reflection of not only compensation incentives but also the corporate culture in banking. This area is sorely in need of research.

The financial crisis of 2007–2009 was the culmination of a credit crunch that began in the summer of 2006 and continued into 2007. 8 Most agree that the crisis had its roots in the U.S. housing market, although I will later also discuss some of the factors that contributed to the housing price bubble that burst during the crisis. The first prominent signs of problems arrived in early 2007, when Freddie Mac announced that it would no longer purchase high-risk mortgages, and New Century Financial Corporation, a leading mortgage lender to risky borrowers, filed for bankruptcy. 9 Another sign was that during this time the ABX indexes—which track the prices of credit default insurance on securities backed by residential mortgages—began to reflect higher expectations of default risk. 10

While the initial warning signs came earlier, most people agree that the crisis began in August 2007, with large-scale withdrawals of short-term funds from various markets previously considered safe, as reflected in sharp increases in the “haircuts” on repos and difficulties experienced by asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) issuers who had trouble rolling over their outstanding paper. 11

Causing this stress in the short-term funding markets in the shadow banking system during 2007 was a pervasive decline in U.S. house prices, leading to concerns about subprime mortgages. 12 As indicated earlier, the ABX index reflects these concerns at the beginning of 2007 (see Benmelech and Dlugosz 2009 ; Brunnermeier 2009 ; Gorton and Metrick 2012 ). The credit rating agencies (CRAs) downgraded asset-backed financial instruments in mid-2007. 13 The magnitude of the rating actions—in terms of the number of securities affected and the average downgrade—in mid-2007 appeared to surprise investors. 14 Benmelech and Dlugosz (2009) show that a large number of structured finance securities were downgraded in 2007–2008, and the average downgrade was 5–6 notches. This is substantially higher than the historical average. For example, during the 2000–2001 recession, when one-third of corporate bonds were downgraded, the average downgrade was 2–3 notches.

Consequently, credit markets continued to tighten. The Federal Reserve opened up short-term lending facilities and deployed other interventions (described later in the paper) to increase the availability of liquidity to financial institutions. But this failed to prevent the hemorrhaging, as asset prices continued to decline.

In early 2008, institutional failures reflected the deep stresses that were being experienced in the financial market. Mortgage lender Countrywide Financial was bought by Bank of America in January 2008. And then in March 2008, Bear Stearns, the sixth largest U.S. investment bank, was unable to roll over its short-term funding due to losses caused by price declines in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). Its stock price had a precrisis fifty-two-week high of $133.20 per share, but plunged precipitously as revelations of losses in its hedge funds and other businesses emerged. JP Morgan Chase made an initial offer of $2 per share for all the outstanding shares of Bear Stearns, and the deal was consummated at $10 per share when the Federal Reserve stepped in with a financial assistance package.

The problems continued as IndyMac, the largest mortgage lender in the United States, collapsed and was taken over by the federal government. Things worsened as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (with ownership of $5.1 trillion of U.S. mortgages) became sufficiently financially distressed and were taken over by the government in September 2008. The next shock was when Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, failing to raise the capital it needed to underwrite its downgraded securities. On the same day, AIG, a leading insurer of credit defaults, received $85 billion in government assistance, as it faced a severe liquidity crisis. The next day, the Reserve Primary Fund, a money market fund, “broke the buck,” causing a run on these funds. Interbank lending rates spiked.

On September 25, 2008, savings and loan giant, Washington Mutual, was taken over by the FDIC, and most of its assets were transferred to JP Morgan Chase. 15 By October, the cumulative weight of these events had caused the crisis to spread to Europe. In October, global cooperation among central banks led them to announce coordinated interest rate cuts and a commitment to provide unlimited liquidity to institutions. However, there were also signs that this was being recognized as an insolvency crisis. So the liquidity provision initiatives were augmented by equity infusions into banks. By mid-October, the U.S. Treasury had invested $250 billion in nine major banks.

The crisis continued into 2009. By October, the unemployment rate in the United States rose to 10%.

Although there is some agreement on the causes of the crisis, there are disagreements among experts on many of the links in the causal chain of events. We begin by providing in Figure 1 a pictorial depiction of the chain of events that led to the crisis and then discuss each link in the chain.

The chain of events leading up to the crisis

2.1 External factors and market incentives that created the house price bubble and the preconditions for the crisis

In the many books and articles written on the financial crisis, various authors have put forth a variety of precrisis factors that created a powder keg just waiting to be lit. Lo (2012) provides an excellent summary and critique of twenty-one books on the crisis. He observes that there is no consensus on which of these factors were the most significant, but we will discuss each in turn.

2.1.1 Political factors

Rajan (2010) reasons that economic inequities had widened in the United States due to structural deficiencies in the educational system that created unequal access for various segments of society. Politicians from both parties viewed the broadening of home ownership as a way to deal with this growing wealth inequality—a political proclivity that goes back at least to the 19th century Homestead Act—and therefore undertook legislative initiatives and other inducements to make banks extend mortgage loans to a broader borrower base by relaxing underwriting standards, and this led to riskier mortgage lending. 16 The elevated demand for houses pushed up house prices and led to the housing price bubble. In this view, politically motivated regulation was a contributing factor in the crisis.

This point has been made even more forcefully by Kane (2009 , forthcoming ) who argues that, for political reasons, most countries (including the United States) establish a regulatory culture that involves three elements: (1) politically directed subsidies to selected bank borrowers, (2) subsidized provision of implicit and explicit repayment guarantees to the creditors of banks, and (3) defective government monitoring and control of the problems created by the first two elements. These elements, Kane (2009) argues, undermine the quality of bank supervision and produce financial crises.

Perhaps these political factors can explain the very complicated regulatory structure for U.S. banking. Agarwal et al. (2014) present evidence that regulators tend to implement identical rules inconsistently because they have different institutional designs and potentially conflicting incentives. For U.S. bank regulators, they show that federal regulators are systematically tougher and tend to downgrade supervisory ratings almost twice as frequently as state supervisors for the same bank. These differences in regulatory “toughness” increase the effective complexity of regulations and impede the implementation of simple regulatory rules, making the response of regulated institutions to regulations less predictable than in theoretical models and generating another potential source of financial fragility.

A strikingly different view of political influence lays the blame on deregulation motivated by political ideology. Deregulation during the 1980s created large and powerful financial institutions with significant political clout to block future regulation, goes the argument presented by Johnson and Kwak (2010) . This “regulatory capture” created a crisis-prone financial system with inadequate regulatory oversight and a cozy relationship between government and big banks.

2.1.2 Growth of securitization and the OTD model

It has been suggested that the desire of the U.S. government to broaden ownership was also accompanied by monetary policy that facilitated softer lending standards by banks. In particular, an empirical study of Euro-area and U.S. Bank lending standards by Maddaloni and Paydro (2011) finds that low short-term interest rates (generated by an “easy money” monetary policy) lead to softer standards for household and business loans. Moreover, this softening is amplified by the originate-to-distribute (OTD) model of securitization, 17 weak supervision over bank capital, and a lax monetary policy. 18 These conditions thus made it attractive for commercial banks to expand mortgage lending in the period leading to the crisis and for investment banks to engage in warehouse lending using nonbank mortgage lenders. Empirical evidence also has been provided that the OTD model encouraged banks to originate risky loans in ever increasing volumes. Purnanandam (2011) documents that a one-standard-deviation increase in a bank’s propensity to sell off its loans increases the default rate by about 0.45 percentage points, representing an overall increase of 32%.

The effect of these developments in terms of the credit that flowed into the housing market to enable consumers to buy homes was staggering. 19 Total loan originations (new and refinanced loans) rose from $500 billion in 1990 to $2.4 trillion in 2007, before declining to $900 billion in the first half of 2008. Total amount of mortgage loans outstanding increased from $2.6 to $11.3 trillion over the same period. Barth et al. (2009) show that the subprime share of home mortgages grew from 8.7% in 1995 to a peak of 13.5% in 2005.

2.1.3 Financial innovation

Prior to the financial crisis, we witnessed an explosion of financial innovation for over two decades. One contributing factor was information technology, which made it easier for banks to develop tradable securities and made commercial banks more intertwined with the shadow banking system and with financial markets. But, of course, apart from information technology, there had to be economic incentives for banks to engage in innovation. Thakor (2012) develops an innovation-based theory of financial crises, which starts with the observation that financial markets are very competitive, so with standard financial products—those whose payoff distributions everybody agrees on—it is hard for financial institutions to have high profit margins. This encourages the search for new financial products, especially those whose creditworthiness not everybody agrees on. The lack of unanimity of the investment worth of the new financial products limits how competitive the market for those products will be and allows the offering institutions to earn high initial profits. 20

But such new products are also riskier by virtue of lacking a history. The reason is that it is not only competitors who may disagree that these are products worthy of investment but also the financiers of the institutions offering these products, and there is a paucity of historical data that can be relied upon to eliminate the disagreement. When this happens, short-term funding to the innovating institutions will not be rolled over, and a funding crisis ensues. The explosion of new asset-backed securities created by securitization prior to the crisis created an ideal environment for this to occur.

This view of how financial innovation can trigger financial crises is also related to Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny’s (2012) model in which new securities—with tail risks that investors ignore—are oversupplied to meet high initial demand and then dumped by investors when a recognition of the risks induces a flight to safety. Financial institutions are then left holding these risky securities.

These theories explain the 2007–2009 crisis, as well as many previous crises. For example, perhaps the first truly global financial crisis occurred in 1857 and was preceded by significant financial innovation to enable investments by British and other European banks in U.S. railroads and other assets.

2.1.4 U.S. monetary policy

Taylor (2009) argues that the easy-money monetary policy followed by the U.S. Federal Reserve, especially in the six or seven years prior to the crisis, was a major contributing factor to the price boom and subsequent bust that led to the crisis. Taylor (2009) presents evidence that monetary policy was too “loose fitting” during 2007–2009 in the sense that actual interest rate decisions fell well below what historical experience would suggest policy should be based on the Taylor rule. 21

Taylor (2009) shows that these unusually low interest rates, a part of a deliberate monetary policy choice by the Federal Reserve, accelerated the housing boom and thereby ultimately led to the housing bust. The paper presents a regression to estimate the empirical relationship between the interest rate and housing starts, showing that there was a high positive correlation between the intertemporal decline in interest rates during 2001–2007 and the boom in the housing market. Moreover, a simulation to see what would have happened in the counterfactual event that the Taylor rule interest rate policy had been followed indicates that we would not have witnessed the same housing boom that occurred in reality. And without a housing boom, there would be no bubble to burst and no crisis.

The impact of low interest rates on housing prices was amplified by the incentives the low interest rate environment provided for lenders to make riskier (mortgage) loans. When the central bank keeps interest loans low for so long, it pushes down banks’ net interest margins, and one way for banks to respond is to elevate these margins by taking on more risk. This induced banks to increase the borrower pool by lending to previously excluded high-risk borrowers, further fueling the housing price boom.

It was not only the U.S. central bank that followed an easy-money policy and experienced a housing boom. In Europe, deviations from the Taylor rule varied in size across countries due to differences in inflation and GDP growth. The country with the largest deviation from the rule was Spain, and it had the biggest boom in housing, as measured by the change in housing investment as a share of GDP. Austria had the smallest deviation from the rule and also experienced the smallest change in housing investment as a share of GDP.

Taylor (2009) notes that there was apparently coordination among central banks to follow this easy-money policy. A significant fraction of the European Central Bank (ECB) interest rate decisions can be explained by the influence of the Federal Reserve’s interest rate decisions.

2.1.5 Global economic developments

Jagannathan, Kapoor, and Schaumburg (2013) have pointed to developments in the global economy as a contributing factor. In the past two decades, the global labor market has been transformed, with emerging-market countries—most notably China—accounting for an increasing percentage of global GDP. The opening up of emerging-market economies, combined with centrally controlled exchange rates to promote exports, has led to the accumulation of large amounts of savings in these countries. And the lack of extensive social safety nets means that these savings have not been depleted by elevated domestic consumption. Rather, the savers have sought to invest in safe assets, resulting in huge inflows of investments in the United States in assets like Treasury bonds and AAA-rated mortgages. When coupled with the easy-money monetary policy pursued in the United States over roughly the same time period, the result was a very large infusion of liquidity into the United States and Western Europe, which contributed to exceptionally low mortgage interest rates.

This would normally lead to an increase in inflation as more money is available to purchase goods and services. However, the rise of emerging-market economies meant that companies like Wal-Mart, IBM, and Nike could move procurement, manufacturing, and a variety of back-office support services to these countries with lower labor costs. Consequently, core inflation stayed low in the west and put little pressure on central banks to reverse their easy-money monetary policies.

It is argued that the flood of this “hot money” found its way into real estate, increasing demand for housing, and pushing house prices to unprecedented levels.

2.1.6 Misaligned incentives

There are many who have suggested misaligned incentives also played a role. The argument goes as follows. Financial institutions, especially those that viewed themselves as too big to fail (TBTF), took excessive risks because de jure safety-net protection via deposit insurance and de facto safety-net protection due to regulatory forbearance stemming from the reluctance to allow such institutions to fail. 22 Such risk taking was permitted due to lax oversight by regulators whose incentives were not aligned with those of taxpayers. 23 Moreover, “misguided” politicians facilitated this with their overzealous embrace of unregulated markets. 24 This is also the essence of the report of the U.S. government’s Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC). 25

The risk taking was a part of the aggressive growth strategies of banks. These strategies were pursued to elevate net interest margins that were depressed by the prevailing low-interest-rate monetary policy environment, as discussed earlier. Banks grew by substantially increasing their mortgage lending, which provided increased “throughput” for investment banks to securitize these mortgages and create and sell securities that enhanced these banks’ profits, with credit rating agencies being viewed as complicit due to their willingness to assign high ratings to structured finance products. 26 This increase in financing was another facilitating factor in pushing up home prices. The presence of government safety nets also created incentives for banks to pursue high leverage, as the credit ratings and market yields of bank debt remained less sensitive to leverage increases than for nonfinancial firms. 27 Combined with riskier asset portfolio strategies, this increased the fragility of banks. Moreover, reputational concerns may have also played a role. Thakor (2005) develops a theory in which banks that have extended loan commitments overlend during economic booms and high stock price periods, sowing the seeds of a subsequent crisis. The prediction of the theory that there is overlending by banks during the boom that precedes the crisis seems to be supported by the data. There is also evidence of managerial fraud and other misconduct that may have exacerbated the misalignment of incentives at the bank level. Piskorski, Seru, and Witkin (2014) provide evidence that buyers of mortgages received false information about the true quality of assets in contractual disclosures made by selling intermediaries in the nonagency market. They show that misrepresentation incentives became stronger as the housing market boomed, peaking in 2006. What is somewhat surprising is that even reputable intermediaries were involved in misrepresentation, suggesting that managerial career concerns were not strong enough to deter this sort of behavior. 28 Consequently, the element of surprise on the part of investors when true asset qualities began to be revealed was likely greater than it would have been absent the fraud and may have added to the precipitous decline in liquidity during the crisis.

2.1.7 Success-driven skill inferences

One weakness in the misaligned-incentives theory is that it fails to explain the timing of the crisis of 2007–2009. After all, these incentives have been in place for a long time, so why did they become such a big problem in 2007 and not before? Thakor (forthcoming) points out that there are numerous perplexing facts about this crisis that cannot be readily explained by the misaligned incentives story of the crisis, and thus, as important as misaligned incentives were, they cannot be the whole story of the crisis. For example, the financial system was flush with liquidity prior to the crisis, but then liquidity declined sharply during the crisis. Why? Moreover, the recent crisis followed a long period of high profitability and growth for the financial sector, and during those good times, there was little warning of the onset and severity of the crisis from any of the so-called “watchdogs” of the financial system-rating agencies, regulators, and creditors of the financial system. 29

If misaligned incentives were the major cause of the crisis, then one would expect a somewhat different assessment of potential risks from the one expressed above. Thakor (2015a) develops a theory of risk management over the business cycle to explain how even rational inferences can weaken risk management and sow the seeds of a crisis. 30 The idea is as follows. Suppose that there is a high probability that economic outcomes—most notably the probabilities of loan defaults—are affected by the skills of bankers in managing credit risk and a relatively small probability that these outcomes are purely exogenous, that is, driven solely by luck or factors beyond the control of bankers. Moreover, there is uncertainty and intertemporal learning about the probability that outcomes are purely exogenous. Banks initially make relatively safe loans because riskier (potentially more profitable) loans are viewed as being too risky and hence not creditworthy. Suppose that these safe loans successfully pay off over time. As this happens, everybody rationally revises upward their beliefs about the abilities of banks to manage (credit) risk. Moreover, because aggregate defaults are low, the probability that outcomes are purely exogenous is also revised downward. Consequently, it becomes possible for banks to finance riskier loans. And if these successfully pay off, then even riskier loans are financed. This way, increased risk taking in banking continues unabated, and no one talks about an impending crisis.

Eventually, even though the probability of the event is low, it is possible that a large number of defaults will occur across banks in the economy. At this stage, investors revise their beliefs about the skills of bankers, as well as beliefs about the probability that outcomes are purely exogenous. Because beliefs about bankers’ skills were quite high prior to the occurrence of large aggregate defaults, investors infer with a relatively high probability that outcomes are indeed driven by luck. This causes beliefs about the riskiness of loans to move sharply in the direction of prior beliefs. And since only relatively safe loans could be financed with these prior beliefs, the sudden drop in beliefs about the risk-management abilities of banks causes investors to withdraw funding for the loans that are suddenly viewed as being “excessively risky.” This theory predicts that when there is a sufficiently long period of high profitability and low loan defaults, then bank risk-taking increases and that a financial crisis occurs only when its ex ante probability is being viewed as being sufficiently low.

2.1.8 The diversification fallacy

Prior to the crisis, many believed that diversification was a cure-all for all sorts of risks. In particular, by pooling (even subprime) mortgages from various geographies and then issuing securities against these pools that were sold into the market, it was believed that the benefits of two kinds of diversification were achieved: geographic diversification of the mortgage pool and then the holding of claims against these pools by diversified investors in the capital market. However, many of these securities were being held by interconnected and systemically important institutions that operated in the financial market, so what the process actually did was to concentrate risk on the balance sheets of institutions in a way that created greater systemic risk. Clearly, advances in information technology and financial innovation were facilitating factors in these developments.

2.2 Housing prices respond to external factors and market incentives

As a consequence of the factors just discussed, house prices in the United States experienced significant appreciation prior to the crisis, especially during the period 1998–2005. The Case-Shiller U.S. national house price index more than doubled between 1987 and 2005, with a significant portion of the appreciation occurring after 1998. Further supporting empirical evidence that there was a housing price bubble is the observation that the ratio of house prices to renting costs appreciated significantly around 1999. 31 See Figure 2 .

Ratio of home prices to rents

Source: Federal Reserve Board: Flow of Funds, Bureau of Economic Analysis: National Income and Product Accounts, and Cecchetti (2008) .

2.3 Leverage and consumption rise to exacerbate the problem

The housing price bubble permitted individuals to engage in substantially higher consumption, fueled by a decline in the savings rate as well as additional borrowing using houses as collateral (see Mian and Sufi 2014 ). U.S. households, feeling rich in an environment of low taxes, low interest rates, easy credit, expanded government services, cheap consumption goods, and rising home prices, went on a consumption binge, letting their personal savings rate drop below 2%, for the first time since the Great Depression. 32 Jagannathan, Kapoor, and Schaumburg (2013) note that the increase in U.S. household consumption during this period was striking; per capita consumption grew steadily at the rate of $1,994 per year during 1980–1999, but then experienced a big jump to approximately $2,849 per year from 2001 to 2007. “Excess consumption,” defined as consumption in excess of wages and salary accruals and proprietors’ income, increased by almost 230% from 2000 to 2007. See Figure 3 .

U.S. household consumption, wages, and excess consumption

All numbers are in 1980 dollar per household. Source: Jagannathan, Kapoor, and Schaumburg (2013) .

Some of this higher consumption was financed with higher borrowing, which was supported by rising home prices. Indeed, the simplest way to convert housing wealth into consumption is to borrow. As the value of residential real estate rose, mortgage borrowing increased even faster. Figure 4 shows this phenomenon—home equity fell from 58% of home value in 1995 to 52% of home value by 2007. 33

Evolution of equity and borrowing in residential real estate

Source: Federal Reserve Flow of Funds and Cecchetti (2008) .

This increase in consumer leverage, made possible by the housing price bubble, had a significant role in the crisis that was to come. Mian and Sufi (2009) show that the sharp increase in mortgage defaults during the crisis was significantly amplified in subprime ZIP codes, or ZIP codes with a disproportionately large share of subprime borrowers as of 1996. They show that, during 2002–2005, the subprime ZIP codes experienced an unprecedented relative growth in mortgage credit, despite significantly declining relative income growth—and in some cases declining absolute income growth—in these neighborhoods. Mian and Sufi (2009) also note that this was highly unusual in that 2002–2005 is the only period in the past eighteen years during which personal income and mortgage credit growth were negatively correlated. 34

The notion that the housing price bubble and its subsequent collapse were due to a decoupling of credit flow from income growth has recently been challenged by Adelino, Schoar, and Severino (2015) . Using data on individual mortgage transactions rather than whole zip codes, they show that the previous findings were driven by a change in borrower composition, i.e., higher-income borrowers buying houses in areas where house prices go up. They conclude that middle-income and high-income borrowers contributed most significantly to the house price bubble and then the subsequent defaults after 2007.

What made the situation worse is that this increase in consumer leverage—and that too by those who were perhaps least equipped to handle it—was also accompanied by an increase in the leverage of financial institutions, especially investment banks and others in the shadow banking system, which turned out to be the epicenter of the crisis. 35 This made these institutions fragile and less capable of handling defaults on consumer mortgages and sharp declines in the prices of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) than they would have been had they been not as thinly capitalized.

The observation that high leverage in financial institutions contributed to the 2007–2009 crisis is sometimes challenged on the grounds that commercial banks were well above the capital ratios required by regulation prior to the start of the crisis. For example, based on a study of bank holding companies (BHCs) during 1992–2006, Berger et al. (2008) document that banks set their target capital levels substantially above well-capitalized regulatory minima and operated with more capital than required by regulation. However, such arguments overlook two important points. First, U.S. investment banks, which were at the epicenter of the subprime crisis, had much lower capital levels than BHCs. Second, it is now becoming increasingly clear that regulatory capital requirements have both been too low to deal with systemic risk issues and also been too easy to game within the risk-weighting framework of Basel I and Basel II. Moreover, the flexibility afforded by Basel II to permit institutions to use internal models to calculate required capital may explain the high leverage of investment banks.

Another argument to support the idea that higher capital in banking would not have helped much is that the losses suffered during the crisis by many institutions far exceeded any reasonable capital buffer they could have had above regulatory capital requirements. The weakness in this argument is that it fails to recognize that the prescription to have more capital in banking is not just based on the role of capital in absorbing actual losses before they threaten the deposit insurance fund but also on the incentive effects of capital on the risk management choices of banks. Indeed, it is the second role that is typically emphasized more in the research on this subject, and it has to do with influencing the probabilities of hitting financial insolvency states, rather than how much capital can help once the bank is in one of those states.

Whether it is the incentive effect or the direct risk-absorption effect of capital or a combination, the key question for policy makers is “does higher capital increase the ability of banks to survive a financial crisis?” Berger and Bouwman (2013) document that commercial banks with higher capital have a greater probability of surviving a financial crisis and that small banks with higher capital are more likely to survive during normal times as well. This is also consistent with Gauthier, Lehar, and Souissi (2012) , who provide evidence that capital requirements based on banks’ contributions to the overall risk of the banking system can reduce the probability of failure of an individual bank and that of a systemic crisis by 25%. Even apart from survival, higher capital appears to facilitate bank performance. Beltratti and Stulz (2012) show that large banks with higher precrisis tier-one capital (i.e., at the end of 2006) had significantly higher stock returns during the crisis. 36

There is also evidence of learning that speaks—albeit indirectly—to this issue. Calomiris and Nissim (2014) find that how the stock market views leverage has also changed as a result of the crisis. They document that while the market rewarded higher leverage with high market values prior to the crisis, leverage has become associated with lower values during and after the crisis.

2.4 Risky lending and diluted screening add fuel to the fire

In Ramakrishnan and Thakor’s (1984) theory of financial intermediation, a raison d’etre for banks is specialization in screening borrowers with a priori unknown default risk (see also Allen 1990 ; Bhattacharya and Thakor 1993 ; Coval and Thakor 2005 ; Millon and Thakor 1985 ). This paves the way for banks to provide a host of relationship banking services (see Boot and Thakor 2000 ). Thus, if these screening incentives are affected by the business model banks use to make loans, it has important implications. Keys et al. (2010) provide empirical evidence indicating that securitization may have weakened the incentives of banks to screen the borrowers whose loans had a high likelihood of being securitized. There is also additional evidence that during the dramatic growth of the subprime (securitized) mortgage market, the quality of the market declined significantly. Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) document that the quality of loans deteriorated for six consecutive years prior to the crisis. 37 The fact that lenders seemed aware of the growing default risk of these loans is suggested by the higher rates lenders charged borrowers as the decade prior to the crisis progressed. For a similar decrease in the quality of the loan (e.g., a higher loan-to-value ratio), a loan made early in the decade was associated with a smaller interest rate increase than a loan made late in the decade. Thus, even though lenders may have underestimated the credit risks in their loans, Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) note that they do seem to have been aware that they were making discernibly riskier loans. 38

There is also evidence that these lenders took steps to shed some of these elevated risks from their balance sheets. Purnanandam (2011) shows that from the end of 2006 until the beginning of 2008, originators of loans tended to sell their loans, collect the proceeds, and then use them to originate new loans and repeat the process. The paper also shows that banks with high involvement in the OTD market during the precrisis period originated excessively poor-quality mortgages, and this result cannot be explained by differences in observable borrower quality, geographical location of the property, or the cost of capital for high-OTD and low-OTD banks. This evidence suggests that the OTD model induced originating banks to have weaker incentives to screen borrowers before extending loans in those cases in which banks anticipated that the loans would be securitized. However, this effect is stronger for banks with lower capital, suggesting that capital strengthens the screening incentives of banks. 39

2.5 The bubble bursts to set the stage for the crisis

Most accounts of the financial crisis attribute the start of the crisis to the bursting of the housing price bubble and the fact that the failure of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 signaled a dramatic deepening of the crisis. But exactly what caused the housing price bubble to burst? Most papers tend to gloss over this issue.

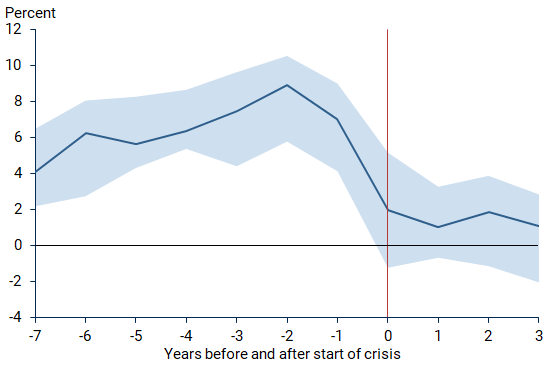

Some papers cite evidence that run-ups in house prices are a commonplace occurrence prior to the start of a crisis. 40 But they do not explain what caused the bubble to burst. However, we can get some insights into what happened by scrutinizing the dynamics of loan defaults in relation to initial home price declines and how this fueled larger subsequent price declines, causing the bubble to burst. Home prices reached their peak in the second quarter of 2006. Holt (2009) points out that initial decline in home prices from that peak was a rather modest 2% from the second quarter of 2006 to the fourth quarter of 2006.

With prime mortgages held by creditworthy borrowers, such a small decline is unlikely to lead to a large number of defaults, and especially not defaults that are highly correlated across geographic regions of the United States. The reason is that these borrowers have 20% of equity in the home when they buy the home, so a small price drop does not put the mortgage “under water” and threaten to trigger default.

Not so with subprime mortgages. Even the small decline in home prices pushed these highly risky borrowers over the edge. Foreclosure rates increased by 43% over the last two quarters of 2006 and increased by a staggering 75% in 2007 compared with 2006, as documented by Liebowitz (2008) . Homeowners with adjustable rate mortgages that had low teaser rates to attract them to buy homes were hit the hardest. The drop in home prices meant that they had negative equity in their homes (since many of them put no money down in the first place), and when their rates adjusted upward, they found themselves hard pressed to make the higher monthly mortgage payments. 41 As these borrowers defaulted, credit rating agencies began to downgrade mortgage-backed securities. This tightened credit markets, pushed up interest rates, and accelerated the downward price spiral, eventually jeopardizing the repayment ability of even prime borrowers. From the second quarter of 2006 to the end of 2007, foreclosure rates for fixed-rate mortgages increased by about 55% for prime borrowers and by about 80% for subprime borrowers. Things were worse for those with adjustable-rate mortgages—their foreclosure rates increased by much higher percentages for prime and subprime borrowers, as noted by Liebowitz (2008) .

2.6 Liquidity shrinks as the crisis begins to set in

Before the crisis, the shadow banking sector of the U.S. economy had experienced dramatic growth. This was significant because the shadow banking system is intricately linked with the “official” insured banking system and supported by the government by backup guarantees. For example, insured banks write all sorts of put options sold to shadow banks and also are financed in part by the shadow banking system. If an insured bank defaults on an insured liability in the shadow banking system, it tempts the government to step in and “cover” shadow banks to “protect” the insured bank. One notable aspect of the shadow banking system is its heavy reliance on short-term debt, mostly repurchase agreements (repos) and commercial paper. As Bernanke (2010) notes, repo liabilities of U.S. broker dealers increased dramatically in the four years before the crisis. The IMF (2010) estimates that total outstanding repo in U.S. markets at between 20% and 30% of U.S. GDP in each year from 2002 to 2007, with even higher estimates for the European Union—a range of 30% to 50% of EU GDP per year from 2002 to 2007.

A repo transaction is essentially a “collateralized” deposit. 42 The collateral used in repo transactions consisted of Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities (MBS), commercial paper, and similar highly liquid securities. As news about defaults on mortgages began to spread, concerns about the credit qualities of MBS began to rise. The bankruptcy filings of subprime mortgage underwriters and the massive downgrades of MBS by the rating agencies in mid-2007 created significant downward revisions in perceptions of the credit qualities of many types of collateral being used in repo transactions (as well as possibly the credit-screening investments and abilities of originators of the underlying mortgages) and caused repo haircuts to spike significantly. This substantially diminished short-term borrowing capacity in the shadow banking sector.

The ABCP market fell by $350 billion in the second half of 2007. Many of these programs required backup support from their sponsors to cover this shortfall. As the major holders of ABCPs, MMFs were adversely affected, and when the Reserve Primary Fund broke the buck, ABCP yields rose for outstanding paper. Many shrinking ABCP programs sold their underlying assets, putting further downward pressure on prices. 43 All of these events led to numerous MMFs requiring assistance from their sponsors to avoid breaking the buck.

Many of these events seemed to have market-wide implications. The failure of Lehman Brothers was followed by larger withdrawals from money-market mutual funds (MMFs) after the Reserve Primary Funds, a large MMF, “broke the buck.” The ABCP market also experienced considerable stress. By July 2007, there was $1.2 trillion of ABCP outstanding, with the majority of the paper held by MMFs. 44 Issuers of commercial paper were unable in many cases to renew funding when a portion of the commercial paper matured, and some have referred to this as a “run.” 45 As Figure 5 shows, things deteriorated quite dramatically in this market beginning August 2007.

Runs on asset-based commercial paper programs

Source: Covitz, Liang, and Suarez (2013) .

The stresses felt by MMFs were a prominent feature of the crisis. The run experienced by the Reserve Primary Fund spread quickly to other funds and led to investors redeeming over $300 billion within just a few days after the failure of Lehman Brothers. This was a surprise at the time it occurred because MMFs have been traditionally regarded as relatively safe. The presumption was that, given this perception of safety, these large-scale withdrawals represented some sort of market-wide liquidity crisis, and this is perhaps why the U.S. government decided to intervene by providing unlimited insurance to all MMF depositors; this was an ad hoc ex post move since there was no formal insurance scheme in place for MMF investors. While the move stopped the hemorrhaging for MMFs, it also meant an ad hoc expansion of the government safety net to a $3 trillion MMF industry.

Determining the nature of this crisis is important for how we interpret the evidence and what we learn from it. The two dominant views of what caused this crisis are (1) illiquidity and (2) insolvency. It is often claimed that the financial crisis that caused the Great Depression was a liquidity crisis, and the Federal Reserve’s refusal to act as a Lender of Last Resort in March 1933 caused the sequence of calamitous events that followed. 46 Thus, determining what caused this crisis and improving our diagnostic ability to assess the underlying nature of future crises based on this learning would be very valuable.

The loss of short-term borrowing capacity and the large-scale withdrawals from money-market funds discussed in the previous section have been viewed by some as a systemic liquidity crisis, but there is some disagreement about whether this was a market-wide liquidity crunch or an institution-specific increase in concerns about solvency risk that caused liquidity to shrink for some banks, but not for others. That is, one viewpoint is that when people realized that MBS were a lot riskier than they thought, liquidity dried up across the board because it was hard for an investor to determine which MBS was of high quality and which was not. The reason for this difficulty is ascribed to the high level of asymmetric information and opaqueness in MBS arising from the opacity of the underlying collateral and the multiple steps in the creation of MBS—from the originations of multiple mortgages to their pooling and then to the specifics of the tranching of this pool. So when bad news arrived about mortgage defaults, there was a (nondiscriminating) market-wide effect. See Gorton (2010) for this interpretation of the data.

A theoretical argument supporting the idea that this was a liquidity crisis is provided by Diamond and Rajan (2011) . In their model, banks face the prospect of a random exogenous liquidity shock at a future date before loans mature, at which time they may have to sell their assets in a market with a limited number of “experts” who can value the assets correctly. The assets may thus have to be sold at fire-sale prices, and the bank may face insolvency as a result. This may cause depositors to run the bank, causing more assets to be dumped and a further price decline. They argue that those with access to cash can therefore purchase assets at very low prices and enjoy high returns, causing holders of cash to demand high returns today and inducing banks to hold on to illiquid assets; this exacerbates the future price decline and illiquidity. Moreover, illiquidity means lower lending initially.

While the liquidity view focuses on the liability side of the bank’s balance sheet—the inability of banks to roll over short-term funding when hit with a liquidity shock—the insolvency view focuses on shocks to the asset side. It says that when the quality of a bank’s assets was perceived to be low, lenders began to reduce the credit they were willing to extend to the bank. According to this view, the crisis was a collection of bank-specific events, and not a market-wide liquidity crunch. Banks with the biggest declines in asset quality perceptions were the ones experiencing the biggest funding shortages.

While one can argue that the underlying causes discussed in the previous section can be consistent with either viewpoint of the crisis and the end result is the same regardless of which viewpoint is correct—banks face dramatically reduced access to liquidity—the triggering events, the testable predictions, and the appropriate policy interventions are all different. In this section I will discuss the differences with respect to the triggering events and testable predictions. I will discuss what the existing empirical evidence has to say and also suggest new empirical tests that can focus more sharply on distinguishing between these viewpoints. Note that empirically distinguishing between these two viewpoints is quite challenging because of the endogeneity created by the relationship between solvency and liquidity risks. A market-wide liquidity crunch can lead to fire sales (e.g., Shleifer and Vishny 2011 ) that can depress asset prices, diminish financing capacity, and lead to insolvency. And liquidity crunches are rarely sunspot phenomena—they are typically triggered by solvency concerns. 47

3.1 The triggering events

If a liquidity shortage caused this crisis, then what could be identified as triggering events? The Diamond and Rajan (2011) model suggests that a sharp increase in the demand for liquidity by either the bank’s depositors or borrowers could provide the liquidity shock that could trigger a crisis. In the data one should observe this in the form of a substantial increase in deposit withdrawals at banks as well as a significant increase in loan commitment takedowns by borrowers prior to the crisis.

If this was an insolvency crisis, then the trigger for the crisis should be unexpectedly large defaults on loans or asset-backed securities that cause the risk perceptions of investors to change substantially. This is implied by the theories developed in the papers of Gennaioli, Shleifer, and Vishny (2012) and Thakor ( 2012 , 2015a , forthcoming ). I will use these different triggering events when I discuss how empirical tests might be designed in future research.

3.2 The testable predictions

If this was a liquidity crisis, then all institutions that relied on short-term debt should have experienced funding declines and engaged in fire sales during the crisis. 48 If this was an insolvency crisis, then only those banks whose poor operating performance (e.g., higher-than-expected default-related losses) should have experienced declines in funding and lending.

If this was a liquidity crisis, then it would have been preceded by large deposit withdrawals and/or large loan commitment takedowns (both representing liquidity shocks) at banks. 49 If this was an insolvency crisis, it would have been preceded by deteriorating loan/asset quality at banks.

If this was a liquidity crisis, it would have affected banks with all capital structures (within the range of high-leverage capital structures observed in practice). 50 If this was an insolvency crisis, its adverse effect would be significantly greater for banks with lower capital ratios.

If this was a liquidity crisis (with a substantial increase in the expected return on holding cash), then borrowing costs would have increased regardless of the collateral offered. If this was an insolvency crisis, then borrowing costs would depend on the collateral offered, and the spread between the costs of unsecured and secured borrowing would increase significantly prior to and during the crisis.

If the crisis was indeed triggered by a liquidity shock that raised the expected return on holding cash, investors would demand a high return to lend money, regardless of how much collateral was offered. Depending on the circumstances, the “haircut” may vary, so more or less collateral may be offered, but the fact will remain that the price of obtaining liquidity will be high. By contrast, if it was an insolvency crisis, then offering collateral will diminish insolvency concerns, so one should observe a significant increase in the difference between the rates on unsecured and secured borrowing. 51

3.3 The existing empirical evidence and possible new tests

On prediction 1, the evidence seems to point to this being an insolvency crisis. Boyson, Helwege, and Jindra (2014) examine funding sources and asset sales at commercial banks, investment banks, and hedge funds. The paper hypothesizes that if liquidity dries up in the financial market, institutions that rely on short-term debt will be forced to sell assets at fire-sale prices. The empirical findings are, however, that the majority of commercial and investment banks did not experience funding declines during the crisis and did not engage in the fire sales predicted to accompany liquidity shortages. The paper does find evidence of pockets of weakness that are linked to insolvency concerns. Problems at financial institutions that experienced liquidity shortages during the crisis originated on the asset side of their balance sheets in the form of shocks to asset value. Commercial banks’ equity and asset values are documented to have been strongly affected by the levels of net charge-offs, whereas investment banks’ asset changes seemed to reflect changes in market valuation. 52

Another piece of evidence comes from MMFs. The notion that MMFs were almost as safe as money was debunked by Kacperczyk and Schnabl (2013) , who examined the risk-taking behavior of MMFs during 2007–2010. They document four noteworthy results. First, MMFs faced an increase in their opportunity to take risk starting in August 2007. By regulation, MMFs are required to invest in highly rated, short-term debt securities. Before August 2007, the debt securities MMFs could invest in were relatively low in risk, yielding no more than 25 basis points above U.S. Treasuries. However, the repricing of risk following the run on ABCP conduits in August 2007 caused this yield spread to increase to 125 basis points. The MMFs now had a significant risk choice: either invest in a safe instrument like U.S. Treasuries or in a much riskier instrument like a bank obligation.

Second, the paper documents that fund flows respond positively to higher realized yields, and this relationship is stronger after August 2007. This created strong incentives for MMFs to take higher risk to increase their yields.

Third, the MMFs did take risks, the paper finds. The funds sponsored by financial intermediaries that had more money-fund business took more risk.

Of course, this by itself does not settle the issue of whether these events were due to a liquidity shock that prompted investors to withdraw money from MMFs, turn inducing higher risk taking by fund managers, or whether the withdrawals were due to elevated risk perceptions. However, Kacperczyk and Schnabl (2010) point out that the increase in yield spreads in August 2007 had to do with the fact that outstanding ABCP fell sharply in August 2007 following news of the failure of Bear Stearns’ hedge funds that had invested in subprime mortgages and BNP Paribas’ suspension of withdrawals from its investment funds due to the inability to assess the values of mortgages held by the funds. Moreover, the massive withdrawals from MMFs from September 16–19, 2008, were triggered by the Reserve Primary Fund announcing that it had suffered significant losses on its holdings of Lehman Brothers Commercial paper. Thus, it appears that the runs suffered by MMFs were mainly due to asset risk and solvency concerns, rather than a liquidity crisis per se, even though what may have been most salient during the early stages of the crisis had the appearance of a liquidity crunch.

As for the second prediction, I am not aware of any evidence that large deposit withdrawals or commitment takedowns preceded this crisis, particularly before asset quality concerns became paramount. There is evidence, however, that loan quality was deteriorating prior to the crisis. The Demyanyk and Van Hemert (2011) evidence, as well as the evidence provided by Purnanandam (2011) , points to this. It also indicates that lenders seemed to be aware of this, which may explain the elevated counterparty risk concerns when the crisis broke.

Now consider the third prediction. There seems to be substantial evidence that banks with higher capital ratios were less adversely affected by the crisis. Banks with higher precrisis capital (1) were more likely to survive the crisis and gained market share during the crisis ( Berger and Bouwman 2013 ), (2) took less risk prior to the crisis ( Beltratti and Stulz 2012 ), and (3) exhibited smaller contractions in lending during the crisis ( Carlson, Shan, and Warusawithana 2013 ).

Turning to the fourth prediction, the empirical evidence provided by Taylor and Williams (2009) is illuminating. Taylor and Williams (2009) examine the LIBOR-OIS Spread . This spread is equal to the three-month LIBOR minus the three-month Overnight Index Swap (OIS). The OIS is a measure of what the market expects the federal funds rate to be over the three-month period comparable to the three-month LIBOR. Subtracting OIS from LIBOR controls for interest rate expectations, thereby isolating risk and liquidity effects. Figure 6 shows the behavior of this spread just before and during the crisis.

The LIBOR-OIS spread during the first year of the crisis

Source: Taylor (2009) .

The figure indicates that the spread spiked in early August 2007 and stayed high. This was a problem because the spread not only is a measure of financial stress but it affects how monetary policy is transmitted due to the fact that rates on loans and securities are indexed to LIBOR. An increase in the spread, holding fixed the OIS, increases the cost of loans for borrowers and contracts the economy. Policy makers thus have an interest in bringing down the spread. But just like a doctor who cannot effectively treat a patient if he misdiagnoses the disease, so can a central bank not bring down the spread if it does not correctly diagnose the reason for its rise in the first place.

To see whether the spread had spiked due to elevated risk concerns or liquidity problems, Taylor and Williams (2009) measured the difference between interest rates on unsecured and secured interbank loans of the same maturity and referred to this as the “unsecured-secured” spread. 53 This spread is essentially a measure of risk. They then regressed the LIBOR-OIS spread against the secured-unsecured spread and found a very high positive correlation. They concluded that the LIBOR-OIS spread was driven mainly by risk concerns and that there was little role for liquidity.

Thus, the evidence that exists at present seems to suggest that this was an insolvency/counterparty risk crisis. However, one may argue that, given the close relationship between liquidity and insolvency risks, the evidence does not necessarily provide a conclusively sharp delineation. This suggests the need for some new tests, which I now discuss.

One possible new test would be to examine international data. In countries with stronger government safety nets (especially LOLR facilities), one would expect liquidity shocks to cause less of a problem in terms of institutions being unable to replace the lost funding. So if this was a liquidity crisis, then it should have been worse in countries with weaker safety nets. On the other hand, stronger safety nets induce greater risk taking, so if this was an insolvency crisis, it should have been worse in countries with stronger safety nets.

Another test would be to look for exogenous variation to get a better handle on causality by examining whether it was the drying up of liquidity that induced price declines for mortgage-backed securities or whether it was the price declines (due to elevated risk concerns) that induced the liquidity evaporation.

A third test would be to conduct a difference-in-differences analysis to examine the changes in funding costs during the crisis for banks with different amounts of collateral. If this was a liquidity crisis, the amount of collateral should not matter much—borrowing costs should rise for all borrowers due to the higher expected returns demanded by those with liquidity available for lending. If this was an insolvency crisis, the increase in borrowing costs should be significantly negatively related to collateral since collateral has both incentive and sorting effects in addition to being a direct source of safety for the lender. This test is in the spirit of the Taylor and Williams (2009) test discussed earlier, but that test speaks to spreads at the aggregate level, whereas I am suggesting a more borrower-specific test.

While these new tests can potentially provide valuable insights, they also will be helpful in better understanding the extent to which regulatory actions and monetary policy contributed to what appears to have been an insolvency crisis. The political desire for universal home ownership led to the adoption of regulations that permitted (and possibly encouraged) riskier mortgage lending, and the easy-money monetary policies in the United States and Europe facilitated access to abundant liquidity to finance these mortgages (see Section 2). Thus, the availability of excess liquidity—rather than its paucity—may have sown the seeds for lax underwriting standards and excessively risky lending that subsequently engendered insolvency concerns. This suggests that in a sense this may be called a “liquidity crisis” after all, but one caused by too much liquidity, rather than too little. Future research could flesh out this idea theoretically, and empirical tests could focus on whether excess precrisis liquidity is causally linked to crises; see Berger and Bouwman (2014) for evidence that excess liquidity creation predicts future crises.

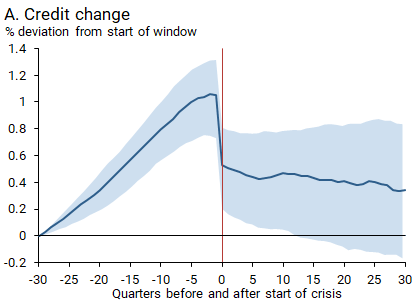

This financial crisis had significant real effects. These included lower household credit demand and lower credit supply (resulting in reduced consumer spending), as well as reduced corporate investment and higher unemployment. I now discuss each of the real effects in this section.

4.1 Credit demand effects