- Alternatives

9 Creative Problem Solving Examples to Solve Real Interview Questions

Jane Ng • 11 January, 2024 • 11 min read

Are you preparing for an interview where you'll need to demonstrate your creative problem solving skills? Being able to think on your feet and discuss real examples of innovative issue resolution is a key strength many employers seek.

To get a deeper understanding of this skill and prepare for related interview questions, let's dive into creative problem solving examples in today's post.

From questions about approaching challenges in a methodical way to those asking you to describe an unconventional solution you proposed, we'll cover a range of common problem solving-focused interview topics.

Table of Contents

What is creative problem solving, benefits of having creative problem solving skills, #1. how do you approach a new problem or challenge , #2. what radical new or different ways to approach a challenge, #3. can you give an example of a time when you came up with a creative solution to a problem, #4. can you recall a time you successfully managed a crisis, #5. can you name three common barriers to creativity and how you overcome each of them, #6. have you ever had to solve a problem but didn't have all the necessary information about it before and what have you done, #7. what do you do when it seems impossible to find the right solution to a problem, #8. how do you know when to deal with the problem yourself or ask for help , #9. how do you stay creative, tips to improve your creative problem solving skills, final thoughts, frequently asked questions, more tips with ahaslides.

Check out more interactive ideas with AhaSlides

- Six Thinking Hats

- Creative Thinking Skills

- Coaching in the workplace examples

- Decision-making examples

Looking for an engagement tool at work?

Gather your mate by a fun quiz on AhaSlides. Sign up to take free quiz from AhaSlides template library!

As the name implies, Creative Problem Solving is a process of creating unique and innovative solutions to problems or challenges. It requires coming up with out-of-the-box ideas instead of the traditional way of doing things. It involves a combination of thinking differently, figuring out what's best, seeing things from different angles, and seizing new opportunities or generating ideas.

And remember, the goal of creative problem solving is to find practical, effective, and unique solutions that go beyond conventional (and sometimes risky, of course).

Need more creative problem solving examples? Continue reading!

As a candidate, having creative problem solving skills can bring several benefits, including:

- Increase employability: Employers are looking for individuals who aren't stuck in a rut but can think critically, solve problems, and come up with creative solutions—things that work more efficiently, and save more time and effort. Showing off your skills can make you a more attractive candidate and increase your chances of getting hired.

- Improve decision-making: They help you to approach problems from different angles and make better decisions.

- Increase adaptability : The ability to find creative solutions can help you adapt to change and tackle new challenges effectively.

- Improve performance: Solving problems in innovative ways can lead to increased productivity, performance, and efficiency.

In the explosive growth of generative AI world, it's considered one of the most important soft skills for employees. Head to the next part to see problem solving interview questions with answers👇

9 Creative Problem Solving Interview Questions and Answers

Here are some creative problem solving examples of interview questions, along with sample answers:

This is the time when you should show the interviewer your way of doing, your way of thinking.

Example answer: "I start by gathering information and understanding the problem thoroughly. I then brainstorm potential solutions and consider which ones have the most potential. I also think about the potential risks and benefits of each solution. From there, I select the best solution and create a plan of action to implement it. I continuously evaluate the situation and make adjustments as needed until the problem is solved."

This question is a harder version of the previous one. It requires innovative and unique solutions to a challenge. The interviewer wants to see if you can have different approaches to problem-solving. It's important to remember that not necessarily giving the best answer but showing your ability to think creatively and generate new ideas.

Example answer: "A completely different way to approach this challenge could be to collaborate with a company or organization outside of our industry. This could provide a fresh perspective and ideas. Another approach might be to involve employees from different departments in the problem-solving process, which can lead to cross-functional solutions and bring in a wide range of ideas and perspectives and more diverse points."

The interviewer needs more concrete proof or examples of your creative problem-solving skills. So answer the question as specifically as possible, and show them specific metrics if available.

Sample answer: "I'm running a marketing campaign, and we're having a hard time engaging with a certain target audience. I was thinking about this from a different perspective and came up with an idea. The idea was to create a series of interactive events so that the customers could experience our products uniquely and in a fun way. The campaign was a huge success and exceeded its goals in terms of engagement and sales."

Interviewers want to see how you handle high-pressure situations and solve problems effectively.

Example answer: "When I was working on a project, and one of the key members of the team was suddenly unavailable because of an emergency. This put the project at risk of being delayed. I quickly assessed the situation and made a plan to reassign tasks to other team members. I also communicated effectively with the client to ensure they were aware of the situation and that we were still on track to meet our deadline. Through effective crisis management, we were able to complete the project tasks on time and without any major hitches."

This is how the interviewer gauges your perspective and sets you apart from other candidates.

Example answer: "Yes, I can identify three common barriers to creativity in problem solving. First, the fear of failure can prevent individuals from taking risks and trying new ideas. I overcome this by accepting failure as a learning opportunity and encouraging myself to experiment with new ideas.

Second, limited resources such as time and finances can reduce creativity. I overcome this by prioritizing problem-solving in my schedule and finding the best cost-effective tools and methods. Lastly, a lack of inspiration can hinder creativity. To overcome this, I expose myself to new experiences and environments, try new hobbies, travel, and surround myself with people with different perspectives. I also read about new ideas and tools, and keep a journal to record my thoughts and ideas."

Having to deal with a "sudden" problem is a common situation you will encounter in any work environment. Employers want to know how you deal with this inconvenience reasonably and effectively.

Example answer: " In such cases, I proactively reach out and gather information from different sources to better understand the situation. I talk to stakeholders, research online, and use my experience and knowledge to fill in any gaps. I also asked clarifying questions about the problem and what information was missing. This allows me to form a holistic view of the problem and work towards finding a solution, even when complete information is not available."

Employers are looking for candidates problem solving, creativity, and critical thinking skills. The candidate's answers can also reveal their problem-solving strategies, thinking ability, and resilience in the face of challenges.

Example answer: "When I have to face a problem that I can't seem to solve, I take a multi-step approach to overcome this challenge. Firstly, I try to reframe the problem by looking at it from a different angle, which can often lead to new ideas and insights. Secondly, I reach out to my colleagues, mentors, or experts in the field for their perspectives and advice. Collaborating and brainstorming with others can result in new solutions.

Thirdly, I take a break, by stepping away from it and doing something completely different to clear my mind and gain a new perspective. Fourthly, I revisit the problem with a fresh mind and renewed focus. Fifthly, I consider alternative solutions or approaches, trying to keep an open mind and explore unconventional options. Finally, I refine the solution and test it to guarantee it meets the requirements and effectively solves the problem. This process allows me to find creative and innovative solutions, even when the problem seems difficult to solve."

In this question, the interviewer wants to get a clearer picture of your ability to assess situations, be flexible when solving problems, and make sure you can work independently as well as in a team.

Example answer: "I would assess the situation and determine if I have the skills, knowledge, and resources needed to solve the problem effectively. If the problem is complex and beyond my ability, I will seek help from a colleague or supervisor. However, if I can afford it and deal with the problem effectively, I'll take it on and handle it myself. However, my ultimate goal is still to find the best solution to the problem on time. "

If you're working in creative fields, a lot of interviewer will ask this question since it's a common problem to have "creative block" among working professionals. They would therefore want to know different methods you had done to go back to the flow.

Example answer: "I immerse myself in broad subjects to spark new connections. I read widely, observe different industries, and expose myself to art/music for perspective. I also brainstorm regularly with diverse groups because other viewpoints fuel my creativity. And I maintain a record of ideas—even far-fetched ones—because you never know where innovations may lead. An eclectic approach helps me solve problems in novel yet practical ways."

Here are some tips to help your creative problem-solving skills:

- Practice active listening and observation: Pay attention to the details around you and actively listen to what others are saying.

- Broaden your perspective: Seek out new experiences and information that can expand your thinking and help you approach problems from new angles.

- Teamwork: Working with others can lead to diverse perspectives and help you generate more creative solutions.

- Stay curious: Keep asking questions to maintain a curious and open-minded attitude.

- Use visualization and mind mapping: These tools can help you see problems in a new light and think about potential solutions in a more organized manner.

- Take care of mental health: Taking breaks and engaging in relaxing activities can help you stay refreshed and avoid burnout.

- Embrace failure: Don't be afraid to try new ways and experiment with different solutions, even if they don't work out.

Hopefully, this article has provided helpful creative problem solving examples and prepared you well to score points with the recruiters. If you want to improve your's creative problem-solving skills, it's important to embrace a growth mindset, accept failure, think creatively, and collaborate with others.

And don't forget to be creative with AhaSlides public templates library !

What is a good example of problem-solving for interview?

When you answer the interviewer's question, make sure to use this approach: clearly defining the problem, gathering relevant data, analyzing causes, proposing a creative solution, tracking impacts, and quantifying the results.

What is a creative approach to problem solving?

Defer judgment. When brainstorming ideas, don't immediately dismiss any suggestions no matter how strange they may seem. Wild ideas can sometimes lead to breakthrough solutions.

A writer who wants to create practical and valuable content for the audience

Tips to Engage with Polls & Trivia

More from AhaSlides

12 Powerful Creative Problem-Solving Techniques That Work

No one likes the feeling of being stuck.

It creates internal tension. That tension seeks resolution.

Thankfully, there are many creative problem-solving techniques for resolving this tension and revealing new solutions.

In this guide, we’ll explore 12 creative ways to solve problems with a variety of techniques, tools, and methods that be used for personal use and in the workplace.

Let’s dive in…

How to Approach Creative Problem-Solving Techniques

All of the creative problem-solving techniques discussed below work some of the time .

While it’s fine to have a favorite “go-to” creative problem-solving technique, the reality is each problem has some unique elements to it.

The key to is mix and match various techniques and methodologies until you get a workable solution.

When faced with a difficult challenge, try a combination of the problem-solving techniques listed below.

The Power of Divergent Thinking

Creativity is everyone’s birthright.

One study with 1,500 participants, found that 98 percent of children around the age of five qualify as geniuses. 1 George Land and Beth Jarman, Breakpoint and Beyond , 1998.

That is, virtually all children are gifted with divergent thinking— the ability to see many possible answers to a question.

For example, how many uses can you think of for a paper clip?

The average adult might offer 10 to 15 answers. Those skilled in divergent thinking divine closer to 200 answers.

Yet, something happens along the way because by adulthood, how many people score at the genius level? Only 2 percent!

That is, we see a complete inversion: from 98% being geniuses in early childhood to only 2% in adulthood.

What causes this debilitating drop in creativity?

According to creativity researcher Sir Ken Robinson, the answer is our schooling. 2 Sir Ken Robinson, Do schools kill creativity? TED Talk , 2006. Through 13 years of “education” our innate creativity is stripped out of us!

Conditioning Yourself for Creative Solutions

So to improve the efficacy of these creative problem-solving techniques, it helps to re-condition ourselves to use divergent thinking.

The key is to learn how to remove our prior conditioning and restore our natural creative abilities. You’ll notice that many of the creative problem-solving techniques below help us do just that.

Thankfully, divergent thinking is a skill and we can develop it like a muscle. So the more we use divergent thinking, the more second nature it becomes.

For this reason, when you’re presented with personal, professional, or business-related problems, celebrate them as an opportunity to exercise your creative abilities.

12 Powerful Creative Problem-Solving Techniques

Now, we’re going to cover 12 creative problem-solving techniques with examples that you can apply right away to get results.

These creative problem-solving methods are:

- Use “What If” Scenarios

- Focus on Quantity Over Quality

- Switch Roles

- Use the Six Thinking Hats Technique

- Explore Different Contexts

- Take a 30,000-Foot View

- Ask Your Subconscious

- Mind Map Your Problem

- Adopt a Beginner’s Mind

- Alter Your State of Consciousness

- Find Your Center

Then, we’ll quickly review a series of problem-solving tools you can experiment with.

1 – Use “What If” Scenarios

Use “what if?” questions to project different scenarios into the future.

In A Whack on the Side of the Head , Roger Von Oech, says,

“In the imaginative phase, you ask questions such as: What if? Why not? What rules can we break? What assumptions can we drop? How about if we looked at this backwards? Can we borrow a metaphor from another discipline? The motto of the imaginative phase is: Thinking something different.”

Using this creative problem-solving technique challenges you to allow your mind to play out different scenarios without judgment or criticism .

(Judgment always comes after the creative problem-solving process—not before.)

2 – Focus on Quantity Over Quality

Creativity research shows that focusing on generating more ideas or solutions instead of on the quality of the ideas ultimately produces better results. 3 Paulus, Paul & Kohn, Nicholas & ARDITTI, LAUREN. (2011). Effects of Quantity and Quality Instructions on Brainstorming. The Journal of Creative Behavior. 45. 10.1002/j.2162-6057.2011.tb01083.x .

This phenomenon is known as the “Equal-Odds rule.” Nobel laureate Linus Pauling instinctively suggested a similar process: 4 The Evening Sentinel , Priestley Award Winner Says Deployment of ABM’s “Silly”, Start Page 1, Quote Page 6, Column 1, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. March 28, 1969.

I was once asked ‘How do you go about having good ideas?’ and my answer was that you have a lot of ideas and throw away the bad ones.

When I used to facilitate meetings and brainstorming sessions with leadership teams in large organizations, this was an invaluable creative problem-solving technique. By consciously focusing on generating more ideas first instead of evaluating the quality of the ideas, you avoid shifting into a critical mindset that often stops the ideation process.

3 – Switch Roles

Our minds tend to get locked in habitual patterns, leading to what’s called “paradigm blindness.” Another related term is the “curse of knowledge,” a common cognitive bias observed in so-called “experts” in their field. 5 Hinds, Pamela J. (1999). “The curse of expertise: The effects of expertise and debiasing methods on prediction of novice performance”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 5 (2): 205–221. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.5.2.205 . S2CID 1081055

This cognitive bias is another illustration of how divergent thinking was conditioned out of us during our formative years.

Switching roles helps us “wear a different hat” where we momentarily shift away from our conditioning.

For example, if you have a marketing-related problem, try putting on an engineer’s hat—or even a gardener’s hat. If you have a problem as an entrepreneur, put yourself in the customer’s mindset. See the world from their point of view.

The idea is to shift your perspective so you can approach the problem from a new angle. Your ability to shift perspectives quickly—without privileging any one perspective—doesn’t only help you solve problems. It also helps you become a stronger leader .

4 – Use the Six Thinking Hats Technique

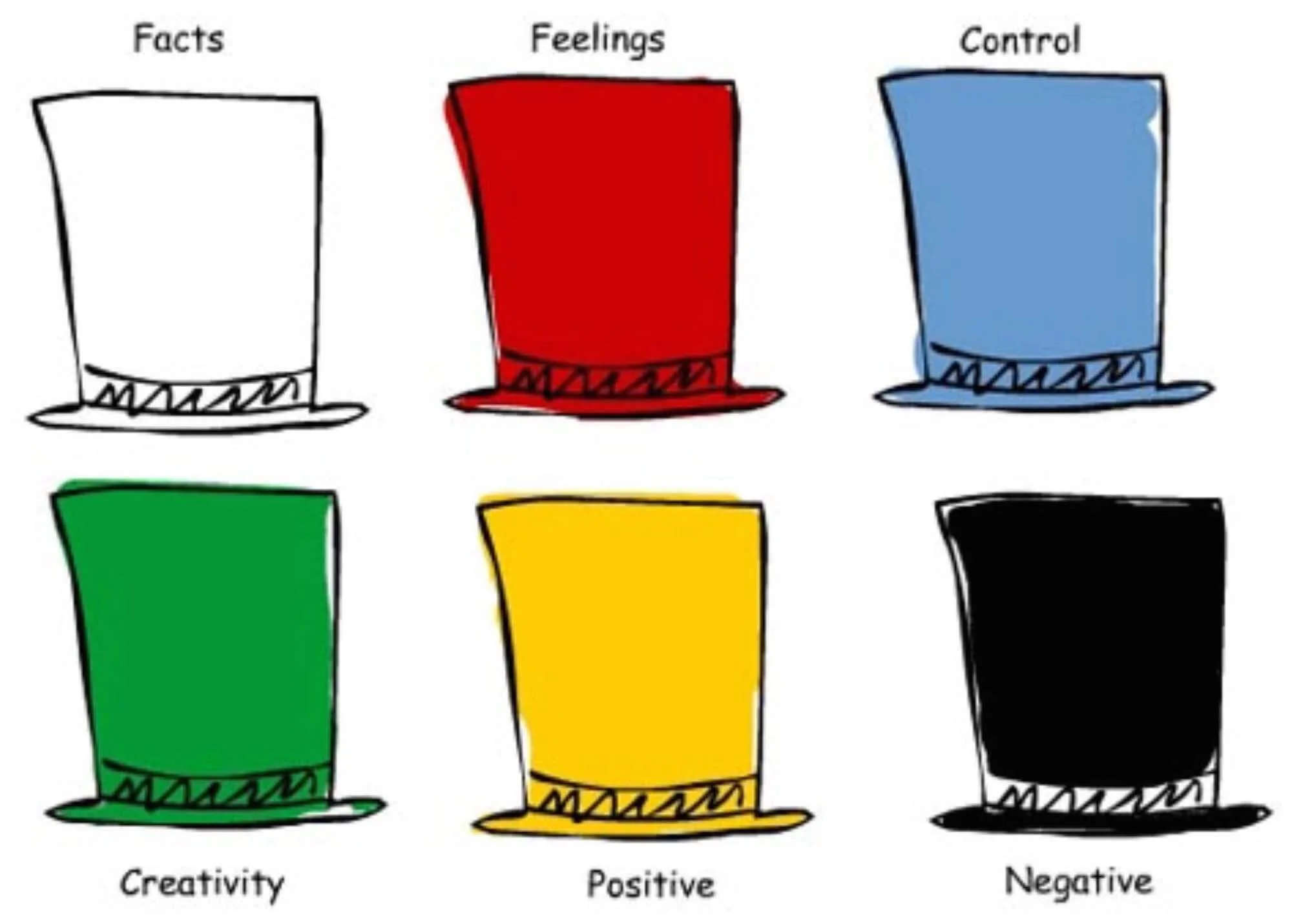

Speaking of hats, creativity researcher Edward de Bono developed an effective creative problem-solving technique called the Six Thinking Hats.

The Six Thinking Hats provides you and your team with six different perspectives to utilize when tackling a problem. (You can use these six hats on your own too.)

Each hat serves a different function. For creative problem solving, you start with the blue hat to clearly define the problem.

You then move to the white hat where you outline all of the existing and known data regarding the issue. Next, you put on the green hat and generate as many ideas as you can (similar to the “quantity over quality” technique above).

Then, you put on the yellow hat, which represents what de Bono calls “value sensitivity.” The yellow hat is used to build on the ideas generated from the green hat phase. Finally, you put on the black hat to evaluate your solutions and play Devil’s Advocate.

The Six Thinking Hats is an excellent technique for group brainstorming and creative problem-solving.

5 – Explore Different Contexts

Many problems arise because we neglect to zoom out from the problem and examine the larger context.

For example, long-term investments are often based on an “investment thesis.” This thesis might be based on trends in the market, consumer demands, brand recognition, dominant market share, strength in innovation, or a combination of factors. But sometimes the assumptions you base your thesis on are wrong.

So if you’re facing a problem at home or work, examine your assumptions.

If sales are down, for example, instead of revisiting your sales strategy investigate the context of your overall industry:

- Has your industry changed?

- Is your business disconnected from your customer’s needs?

- Is your product or service becoming obsolete?

We can often find creative solutions to our problems by shifting the context.

6 – Take a 30,000-Foot View

Often, when we’re stuck in a problem, it’s because we’re “missing the forest for the trees.”

Zoom out and take a “30,000-foot view” of the situation. See your problem from above with a detached, neutral mindset. Take an expansive viewpoint before narrowing in on the specific problem.

This problem-solving technique is another variation of changing the context.

Sometimes you’ll find this to be a powerful creative problem-solving technique where the right solution spontaneously presents itself. (You’ll think to yourself: Why didn’t I see this before? )

7 – Walk Away

Most often, the best problem-solving technique is to stop trying to solve it —and walk away.

Yet, our minds often don’t like this technique. The mind likes to be in control. And walking away means letting go of control.

I spent five years researching creative geniuses trying to better understand the source of inspiration for a book I was writing years ago. 6 Scott Jeffrey, Creativity Revealed: Discovering the Source of Inspiration , 2008.

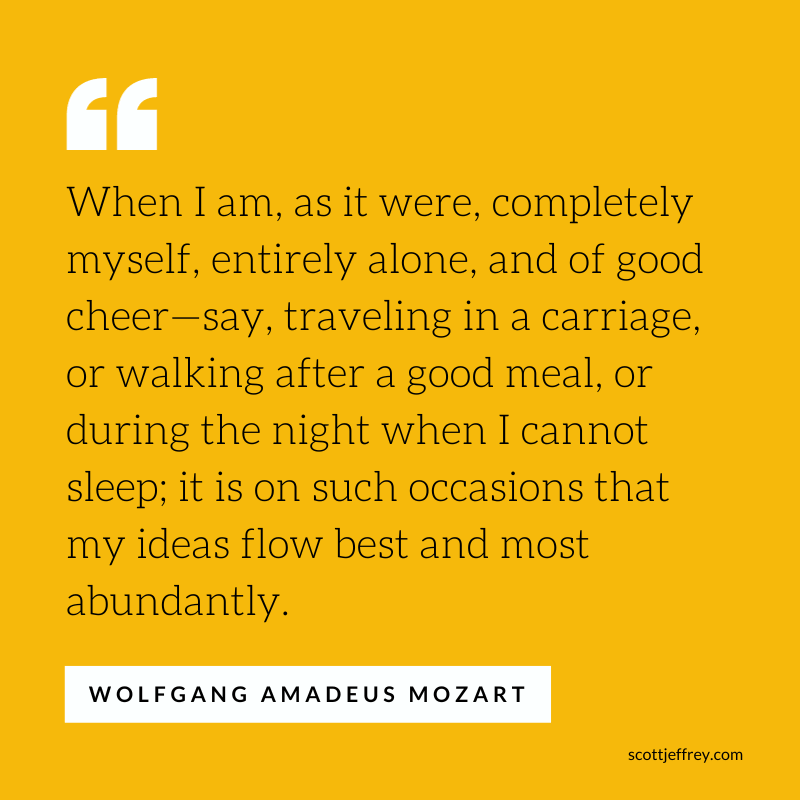

In studying dozens of creative geniuses, from Mozart to William Blake, a clear pattern emerged.

Creative geniuses know when to walk away from the problems they are facing. They instinctively access what can be called the Wanderer archetype.

More recent studies show that deliberate “mind-wandering” supports creativity. 7 Henriksen D, Richardson C, Shack K. Mindfulness and creativity: Implications for thinking and learning. Think Skills Creat. 2020 Sep;37:100689. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100689 . Epub 2020 Aug 1. PMID: 32834868; PMCID: PMC7395604. Great ideas come to use when we’re not trying. 8 Kaplan, M. Why great ideas come when you aren’t trying. Nature (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2012.10678

Wandering and reverie are essential to the creative process because they allow us to hear our Muse. The key is knowing when to let go of trying to solve the problem. Creativity problem-solving can, in this way, become an effortless process.

8 – Ask Your Subconscious

When we’re stuck on a problem and we need a creative solution, it means our conscious mind is stuck.

It does not, however, mean that we don’t already know the answer. The creative solution is often known below our conscious awareness in what can be termed our subconscious mind, or our unconscious.

Psychiatrist Carl Jung realized that dreams are a bridge from the wisdom of our unconscious to our conscious minds. As Jungian analyst Marie-Louise von Franz explains, 9 Fraser Boa, The Way of the Dream: Conversations on Jungian Dream Interpretation With Marie-Louise Von Franz , 1994.

Dreams are the letters of the Self that the Self writes us every night.

One of the most powerful creative problem-solving techniques is to ask your subconscious mind to solve the problem you’re facing before you go to sleep. Then, keep a journal and pen on your nightstand and when you awaken, record whatever comes to mind.

This is a powerful technique that will improve with practice. It’s used by many geniuses and inventors.

Another variation of this creative problem-solving technique that doesn’t require sleeping is to ask your inner guide. I provide a step-by-step creative technique to access your inner guide here .

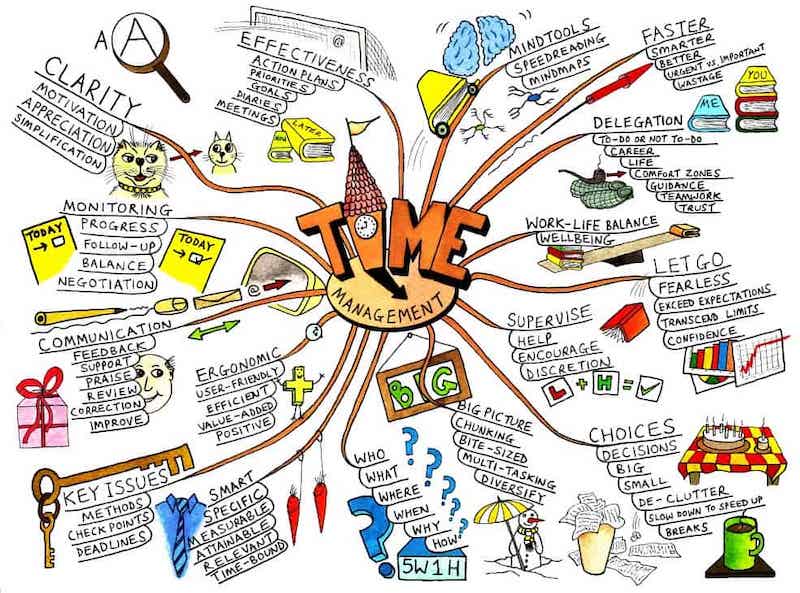

9 – Mind Map Your Problem

Another way to get unstuck in solving problems is to access the visual side of our brain. In left/right hemisphere parlance, the left brain is dominated by logic, reason, and language while the right brain is dominated by images, symbols, and feelings. (I realize that the “science” behind this distinction is now questionable, however, the concept is still useful.)

Our problems arise largely in our “thinking brain” as we tend to favor our thoughts over other modes of processing information. In the language of Jung’s Psychological Types , most of us have a dominant thinking function that rules over our feelings, intuition, and sensing functions.

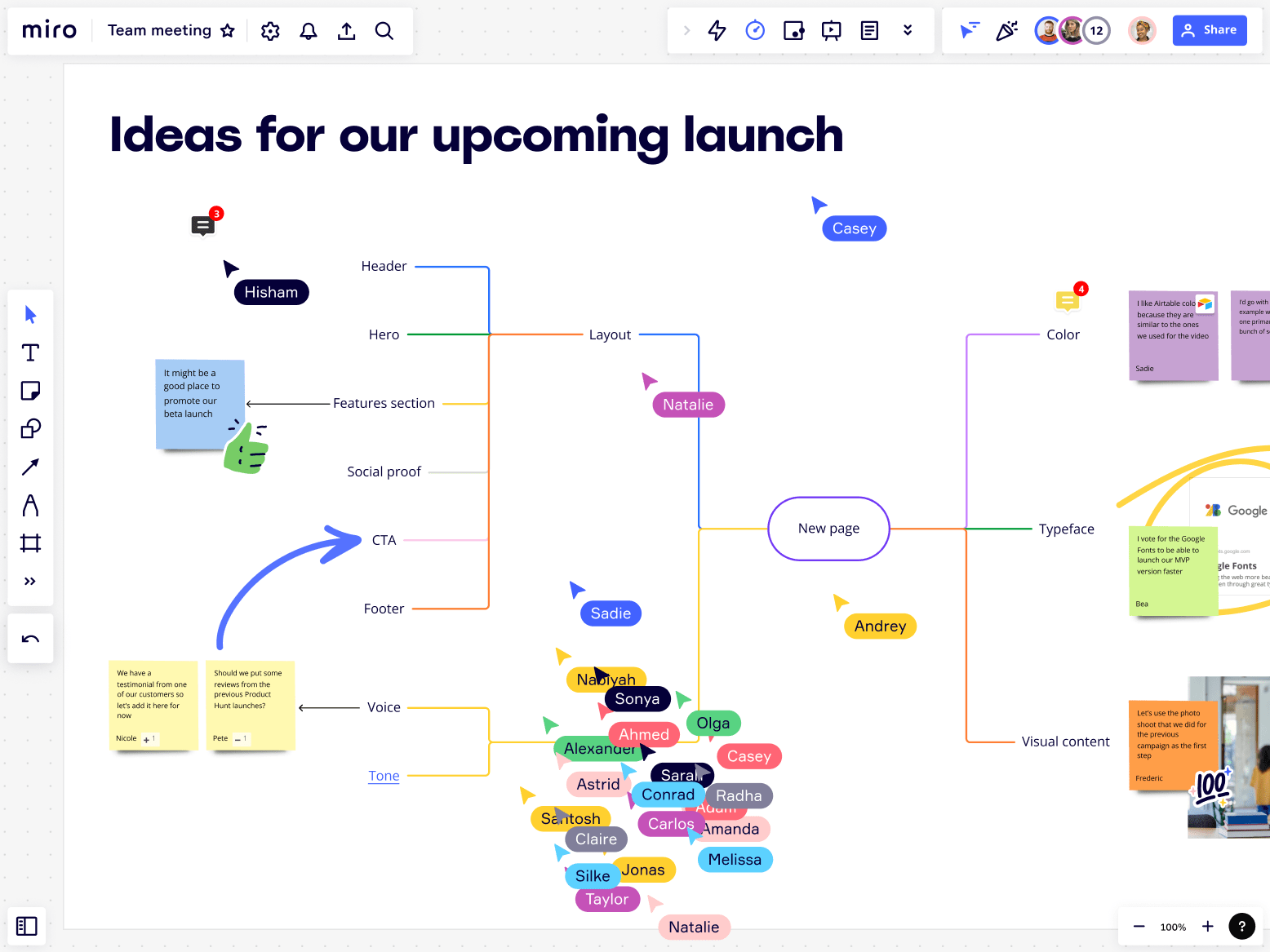

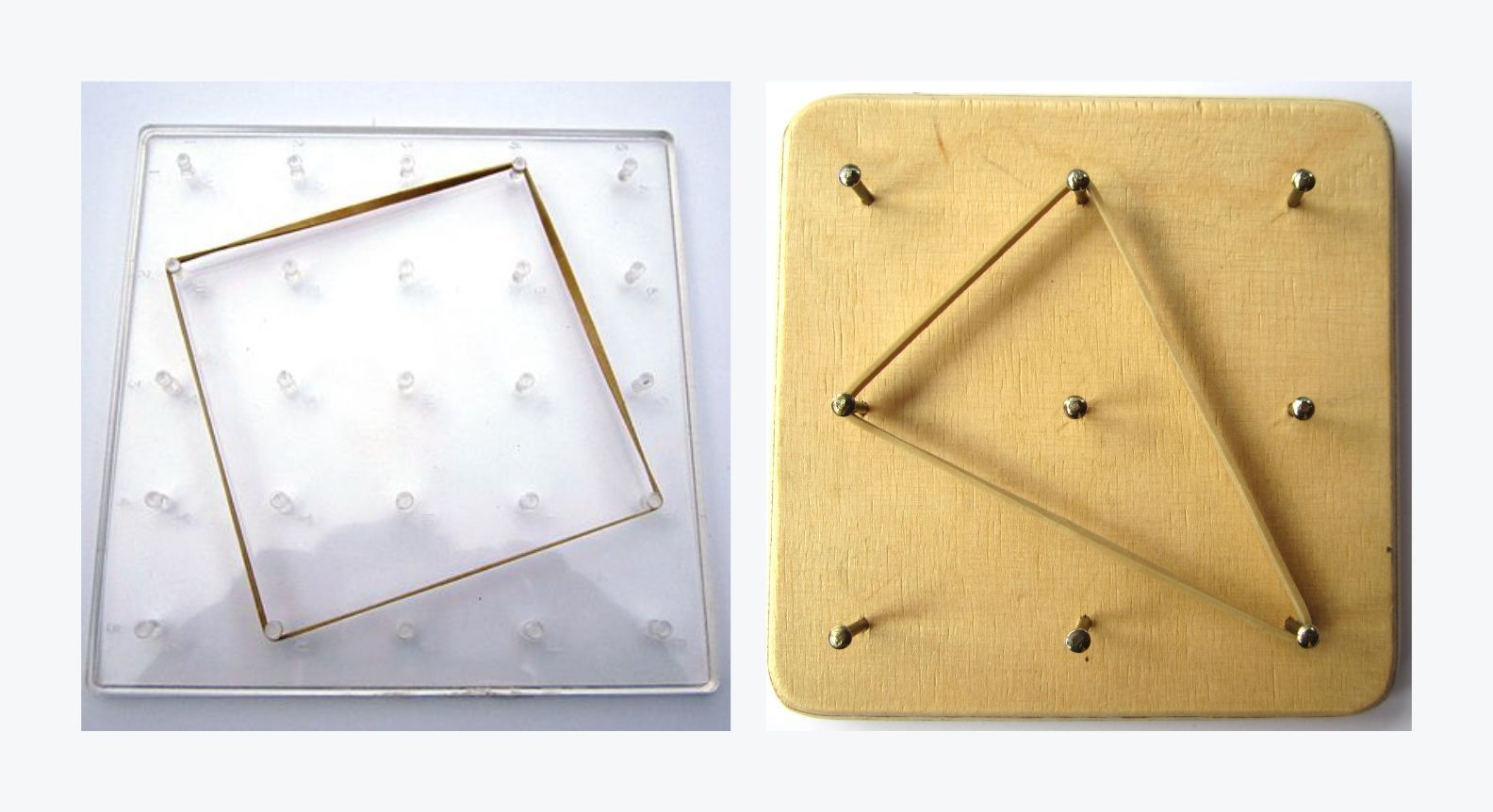

Mind mapping is a powerful creative problem-solving technique that deploys visual brainstorming.

I learned about mind mapping in the 1990s from Tony Buzan’s The Mind Map Book and used this method for many years.

In the context of problem-solving, you draw the problem in the center of the page and then start ideating and connecting ideas from the center. Think of mind mapping as a visual outline.

You don’t need to be a skilled artist to use mind mapping. Nowadays, there are also numerous apps for mind mapping including Mind Meister and Miro, but I would still recommend using a blank piece of paper and some colored pencils or markers.

10 – Adopt a Beginner’s Mind

Our early “education” conditions us with what psychologists call functional fixedness where we look at problems from a familiar viewpoint.

Numerous creative problem-solving techniques we discussed above—like switching the context, changing our roles, wearing the Six Thinking Hats, and taking a 30,000-foot view—are designed to overcome functional fixedness.

Another technique is found in Zen philosophy called a Beginner’s Mind .

With a beginner’s mind, we empty our minds and forget what we think we know. In doing so, we enter a more playful, childlike state. Instead of being serious and “attacking the problem,” we can tinker and play with different ideas and scenarios without any fears of “getting it wrong.”

It can be a liberating experience. Psychologist Abraham Maslow found that self-actualizing individuals enter a state like the Beginner’s Mind where they get fully absorbed in whatever they are doing.

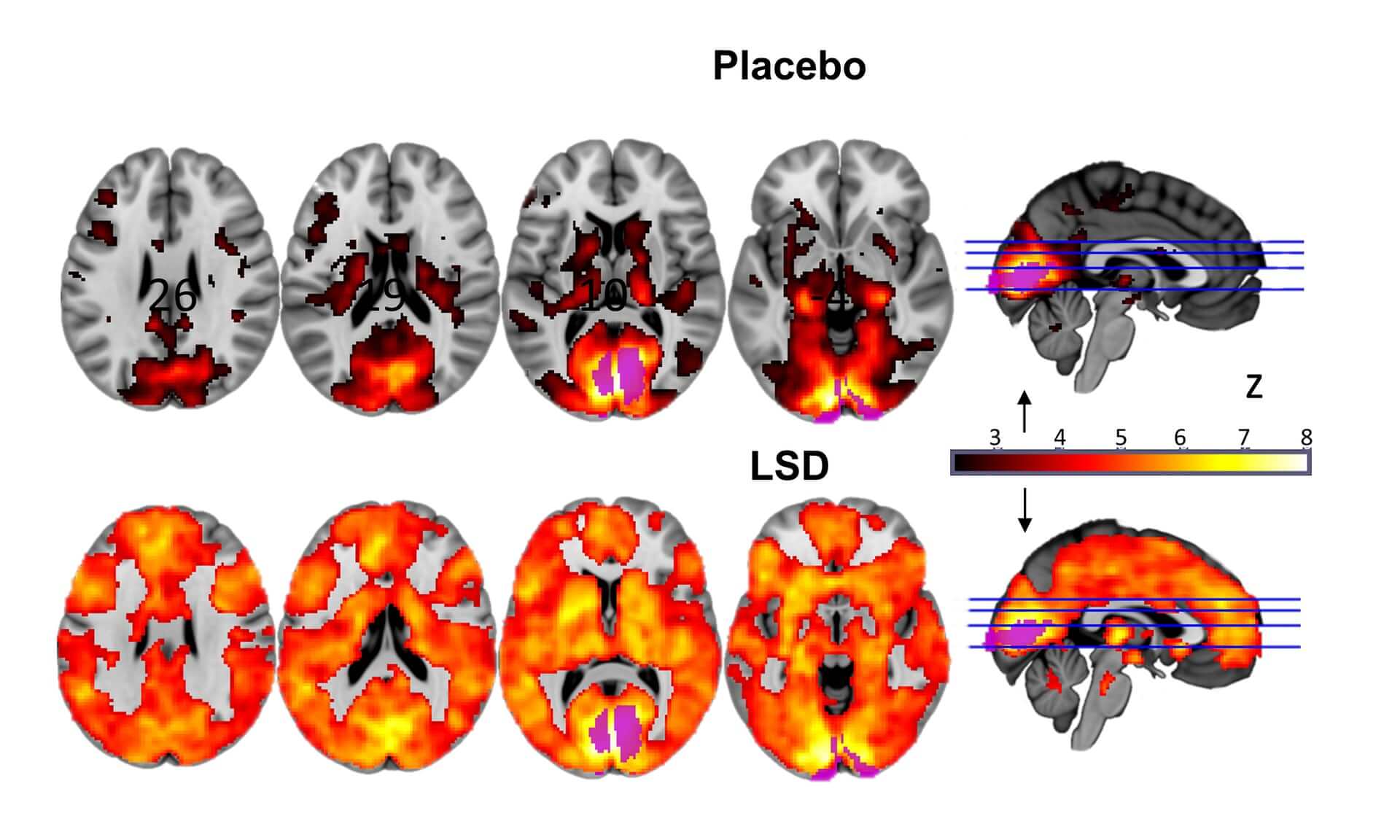

11 – Alter Your State of Consciousness

Another thing I noticed in my examination of artists and creative geniuses is that virtually all of them used various substances to alter their state of consciousness when producing creative work and solving intellectual problems .

The substances vary widely including stimulants like coffee and/or cigarettes, alcohol (like absinthe), and all manner of psychedelic substances like LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and peyote.

I’m not suggesting you should “take drugs” to solve your problems. The point is that it’s incredibly useful to alter your state of consciousness to help find creative solutions.

While using various substances is one way to accomplish this, there are many other methods like:

- Stanislav Grof’s Holotropic Breathing Technique (similar to pranayama breathing)

- The WIM Hof Method (ice cold showers)

- Brainwave entrainment programs (binaural beats and isochronic tones)

- The Silva Method (also uses brainwave entrainment)

- Kasina Mind Media System by Mindplace (light stimulation and binaural beats)

Many of these types of programs shift your brain from a beta-dominant state to an alpha-dominated state which is more conducive for creativity. See, for example, Brain Awake by iAwake Technologies.

12 – Access Your Center

Perhaps the easiest and safest way of altering your state of consciousness is via meditation . Studies show that people experience improved brainstorming and higher creativity after only twenty minutes of meditation—even if they’re inexperienced meditators. 10 Colzato, L.S., Szapora, A., Lippelt, D. et al. Prior Meditation Practice Modulates Performance and Strategy Use in Convergent- and Divergent-Thinking Problems. Mindfulness 8, 10–16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0352-9

When we’re stuck on a problem, or feeling confused about what we should do, we’re usually experiencing internal resistance. Different parts of us called archetypes hijack our minds and give us conflicting wants, beliefs, attitudes, and perspectives. These parts keep us from thinking clearly to find workable solutions.

As such, when you’re stuck, it helps to find your center first . It can also be highly beneficial to ground yourself on the earth . Both of these methods can help you quiet your mind chatter and shift into a more alpha-dominant brain pattern.

Getting in the habit of centering yourself before approaching a problem is perhaps the most powerful creative problem-solving technique. It can greatly assist you in taking a 30,000-foot view of our problem as well.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

We referenced numerous problem-solving tools in the above examples including:

- Roger von Oech’s Creative Whack Pack (a deck of cards with 64 creative strategies)

- Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats method

- Mind mapping (see Tony Buzan’s How to Mind Map or research online)

- Brainwave entrainment (download free samples on iAwake or try your luck online)

- All of the mind-altering methods under “Alter Your State of Consciousness”

If you’re looking for problem-solving tools for a business/group context, in addition to the Six Thinking Hats, you might also try:

SWOT Analysis

Brainwriting.

Let’s have a quick look at each of these tools.

SWOT analysis is an excellent tool for business owners to help them understand their competitive landscape and make important business decisions. SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. SWOT analysis is a practical strategic planning tool for businesses and it can be an effective problem-solving tool for your business.

Five Whys sometimes helps identify the root cause of the problem when it’s not clearly understood. You start by stating the problem as you understand it. Then you ask, “Why?” (For example, why is this occurring? ) As the tool’s name implies, you ask Why questions five times in total.

Brainwriting is a form of brainstorming where individuals generate ideas on their own before meeting to discuss them as a group. For a host of psychological reasons, this is often a superior way of approaching problem-solving in the workplace. Combining brainwriting with the Six Thinking Hats method can be even more powerful.

Using These Creative Problem-Solving Tools

All of the techniques and tools above represent creative problem-solving methods.

These examples illustrate that there are numerous pathways to get the answers we seek.

Some pathways, however, are more effective than others. The key is to experiment with various methods to uncover which ones work best for you .

Different methods will be more effective in different contexts.

Here, wisdom and intuition come into play. Over time, your connection with your inner guide improves and creative problem-solving becomes a more spontaneous process.

Recap: Creative Problem-Solving Techniques

Creative problem-solving is a skill based on the development of divergent thinking combined with altering our state of consciousness.

Due to our early conditioning, our “normal” waking state of consciousness is often filled with biases, limitations, blind spots, and negativity. This causes us to perceive problems rigidly.

When we get “stuck” it’s because our minds are fixed on a limited number of options.

To get “unstuck,” we just need to alter our state of consciousness and examine our problems from various perspectives, which is what the above creative problem-solving techniques are designed to do.

The more you play with these techniques, the more they become second nature to you.

You may find that each technique begins to play off the other. Then, the art and subtleties of the discovery process begin to emerge.

Enjoy solving your next problem!

How to Access Your Imagination

Peak Experiences: A Complete Guide

How to Restore Your Circadian Rhythm

About the Author

Scott Jeffrey is the founder of CEOsage, a self-leadership resource publishing in-depth guides read by millions of self-actualizing individuals. He writes about self-development, practical psychology, Eastern philosophy, and integrated practices. For 25 years, Scott was a business coach to high-performing entrepreneurs, CEOs, and best-selling authors. He's the author of four books including Creativity Revealed .

Learn more >

Some great ideas here. I am particularly intrigued by the "walk away" idea fulfilling the wanderer archetype. While counter intuitive, in my experience, walking away lets my mind develop subconcious connections that are sometimes the best. Sort of like letting my brain do the work instead of me! Bravo!

Todd Alexander

Thanks for your comments, Todd. It seems as though he need to train and remind ourselves to "walk away" because the mind thinks it can push its way through the problem.

How many times does it take for us to "absolutely know" that answers answer themselves when we take a break from forceful problem-solving and walk into the creative nature zone?! ;) The solution presents itself when we let go.

Great Post, Scott!

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Creative Problem Solving

What is creative problem solving.

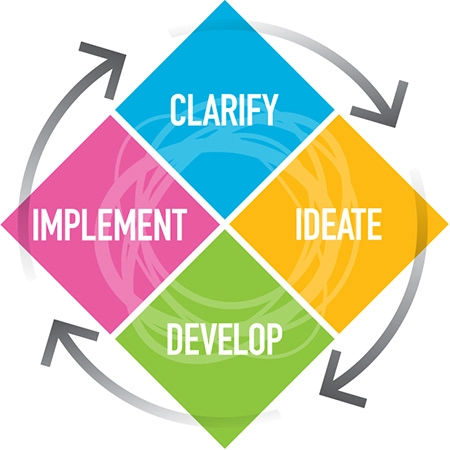

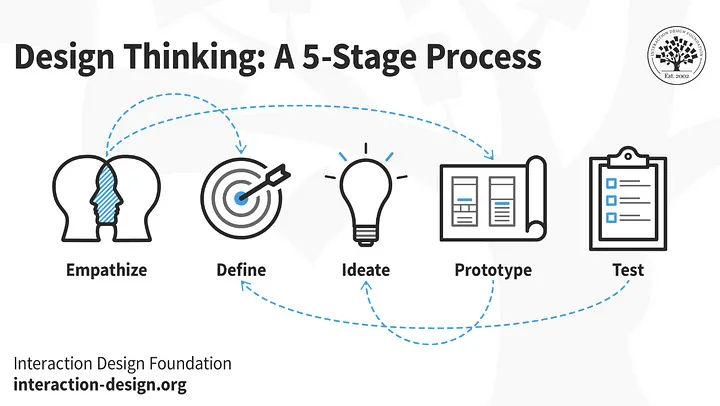

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a process that design teams use to generate ideas and solutions in their work. Designers and design teams apply an approach where they clarify a problem to understand it, ideate to generate good solutions, develop the most promising one, and implement it to create a successful solution for their brand’s users.

© Creative Education Foundation, Fair Use

Why is Creative Problem Solving in UX Design Important?

Creative thinking and problem solving are core parts of user experience (UX) design. Note: the abbreviation “CPS” can also refer to cyber-physical systems. Creative problem solving might sound somewhat generic or broad. However, it’s an ideation approach that’s extremely useful across many industries.

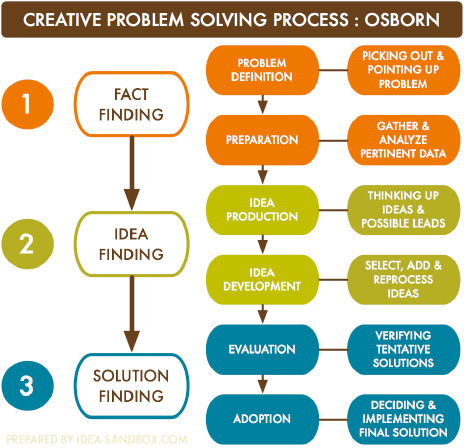

Not strictly a UX design-related approach, creative problem solving has its roots in psychology and education. Alex Osborn—who founded the Creative Education Foundation and devised brainstorming techniques—produced this approach to creative thinking in the 1940s. Along with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. It was a new, systematic approach to problem solving and creativity fostering.

Osborn’s CPS Process.

© IdeaSandbox.com, Fair Use

The main focus of the creative problem solving model is to improve creative thinking and generate novel solutions to problems. An important distinction exists between it and a UX design process such as design thinking. It’s that designers consider user needs in creative problem solving techniques, but they don’t necessarily have to make their users’ needs the primary focus. For example, a design team might trigger totally novel ideas from random stimuli—as opposed to working systematically from the initial stages of empathizing with their users. Even so, creative problem solving methods still tend to follow a process with structured stages.

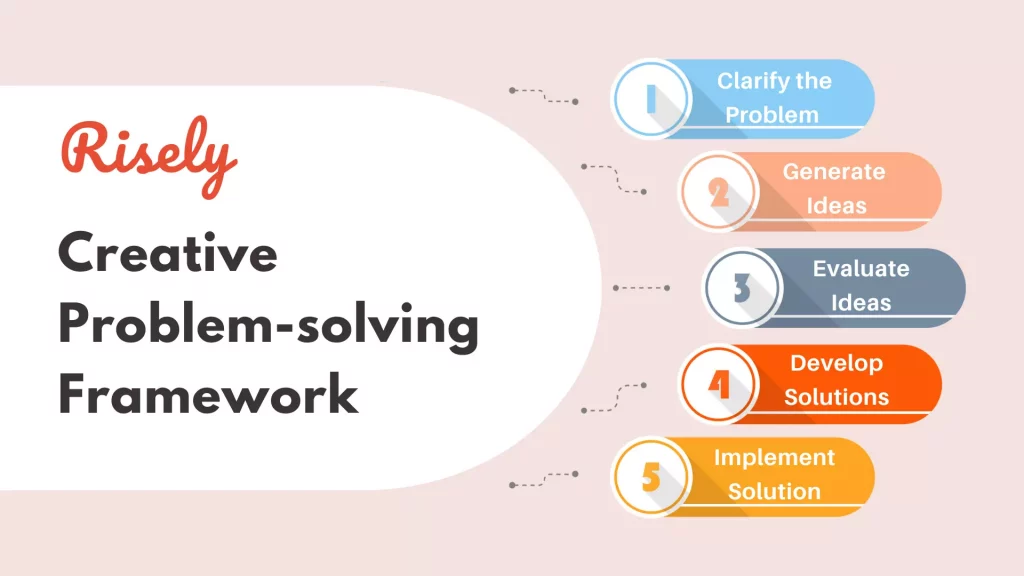

What are 4 Stages of Creative Problem Solving?

The model, adapted from Osborn’s original, typically features these steps:

Clarify: Design teams first explore the area they want to find a solution within. They work to spot the challenge, problem or even goal they want to identify. They also start to collect data or information about it. It’s vital to understand the exact nature of the problem at this stage. So, design teams must build a clear picture of the issue they seek to tackle creatively. When they define the problem like this, they can start to question it with potential solutions.

Ideate: Now that the team has a grasp of the problem that faces them, they can start to work to come up with potential solutions. They think divergently in brainstorming sessions and other ways to solve problems creatively, and approach the problem from as many angles as they can.

Develop: Once the team has explored the potential solutions, they evaluate these and find the strongest and weakest qualities in each. Then, they commit to the one they decide is the best option for the problem at hand.

Implement: Once the team has decided on the best fit for what they want to use, they discuss how to put this solution into action. They gauge its acceptability for stakeholders. Plus, they develop an accurate understanding of the activities and resources necessary to see it become a real, bankable solution.

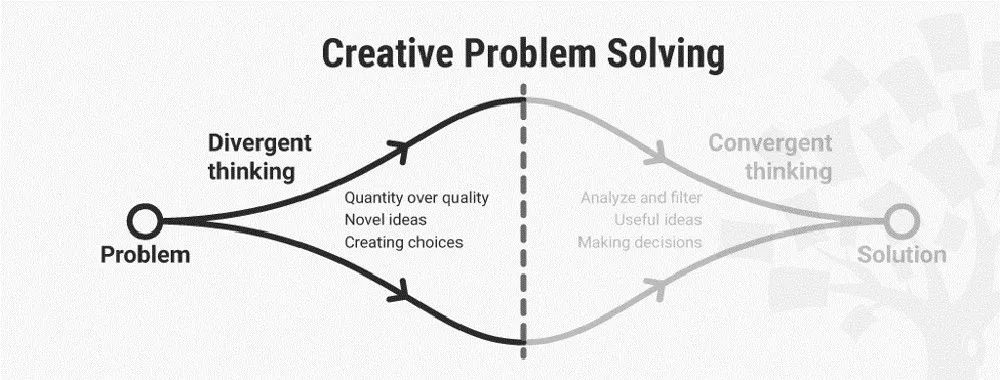

What Else does CPS Involve?

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Two keys to the enterprise of creative problem solving are:

Divergent Thinking

This is an ideation mode which designers leverage to widen their design space when they start to search for potential solutions. They generate as many new ideas as possible using various methods. For example, team members might use brainstorming or bad ideas to explore the vast area of possibilities. To think divergently means to go for:

Quantity over quality: Teams generate ideas without fear of judgment (critically evaluating these ideas comes later).

Novel ideas: Teams use disruptive and lateral thinking to break away from linear thinking and strive for truly original and extraordinary ideas.

Choice creation: The freedom to explore the design space helps teams maximize their options, not only regarding potential solutions but also about how they understand the problem itself.

Author and Human-Computer Interactivity Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains some techniques that are helpful for divergent thinking:

- Transcript loading…

Convergent Thinking

This is the complementary half of the equation. In this ideation mode, designers analyze, filter, evaluate, clarify and modify the ideas they generated during divergent thinking. They use analytical, vertical and linear thinking to isolate novel and useful ideas, understand the design space possibilities and get nearer to potential solutions that will work best. The purpose with convergent thinking is to carefully and creatively:

Look past logical norms (which people use in everyday critical thinking).

Examine how an idea stands in relation to the problem.

Understand the real dimensions of that problem.

Professor Alan Dix explains convergent thinking in this video:

What are the Benefits of Creative Problem Solving?

Design teams especially can benefit from this creative approach to problem solving because it:

Empowers teams to arrive at a fine-grained definition of the problem they need to ideate over in a given situation.

Gives a structured, learnable way to conduct problem-solving activities and direct them towards the most fruitful outcomes.

Involves numerous techniques such as brainstorming and SCAMPER, so teams have more chances to explore the problem space more thoroughly.

Can lead to large numbers of possible solutions thanks to a dedicated balance of divergent and convergent thinking.

Values and nurtures designers and teams to create innovative design solutions in an accepting, respectful atmosphere.

Is a collaborative approach that enables multiple participants to contribute—which makes for a positive environment with buy-in from those who participate.

Enables teams to work out the most optimal solution available and examine all angles carefully before they put it into action.

Is applicable in various contexts—such as business, arts and education—as well as in many areas of life in general.

It’s especially crucial to see the value of creative problem solving in how it promotes out-of-the-box thinking as one of the valuable ingredients for teams to leverage.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains how to think outside the box:

How to Conduct Creative Problem Solving Best?

It’s important to point out that designers should consider—and stick to—some best practices when it comes to applying creative problem solving techniques. They should also adhere to some “house rules,” which the facilitator should define in no uncertain terms at the start of each session. So, designers and design teams should:

Define the chief goal of the problem-solving activity: Everyone involved should be on the same page regarding their objective and what they want to achieve, why it’s essential to do it and how it aligns with the values of the brand. For example, SWOT analysis can help with this. Clarity is vital in this early stage. Before team members can hope to work on ideating for potential solutions, they must recognize and clearly identify what the problem to tackle is.

Have access to accurate information: A design team must be up to date with the realities that their brand faces, realities that their users and customers face, as well as what’s going on in the industry and facts about their competitors. A team must work to determine what the desired outcome is, as well as what the stakeholders’ needs and wants are. Another factor to consider in detail is what the benefits and risks of addressing a scenario or problem are—including the pros and cons that stakeholders and users would face if team members direct their attention on a particular area or problem.

Suspend judgment: This is particularly important for two main reasons. For one, participants can challenge assumptions that might be blocking healthy ideation when they suggest ideas or elements of ideas that would otherwise seem of little value through a “traditional” lens. Second, if everyone’s free to suggest ideas without constraints, it promotes a calmer environment of acceptance—and so team members will be more likely to ideate better. Judgment will come later, in convergent thinking when the team works to tighten the net around the most effective solution. So, everyone should keep to positive language and encourage improvisational tactics—such as “yes…and”—so ideas can develop well.

Balance divergent and convergent thinking: It’s important to know the difference between the two styles of thinking and when to practice them. This is why in a session like brainstorming, a facilitator must take control of proceedings and ensure the team engages in distinct divergent and convergent thinking sessions.

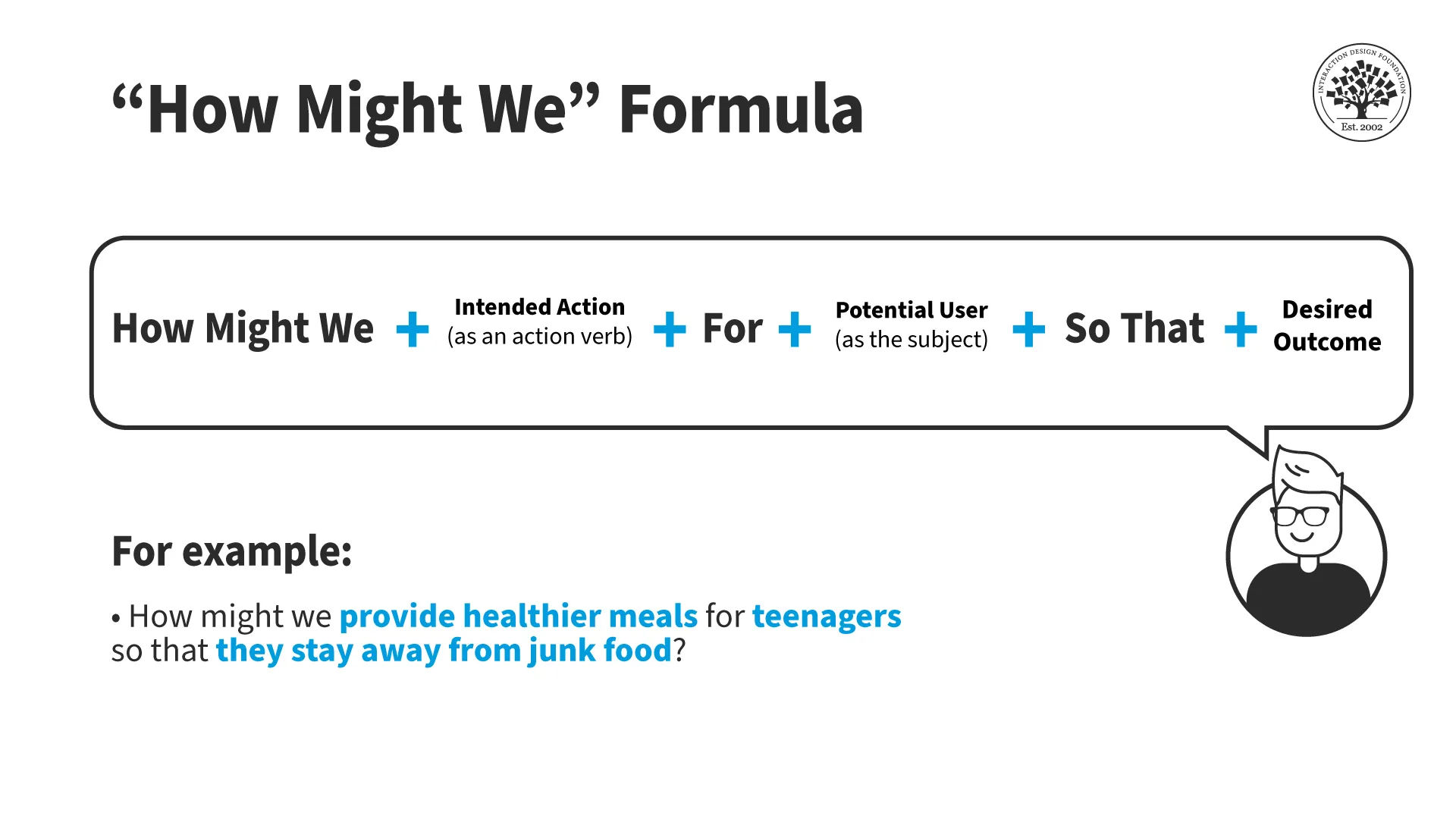

Approach problems as questions: For example, “How Might We” questions can prompt team members to generate a great deal of ideas. That’s because they’re open-ended—as opposed to questions with “yes” or “no” answers. When a team frames a problem so freely, it permits them to explore far into the problem space so they can find the edges of the real matter at hand.

UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains “How Might We” questions in this video:

Use a variety of ideation methods: For example, in the divergent stage, teams can apply methods such as random metaphors or bad ideas to venture into a vast expanse of uncharted territory. With random metaphors, a team prompts innovation by drawing creative associations. With bad ideas, the point is to come up with ideas that are weird, wild and outrageous, as team members can then determine if valuable points exist in the idea—or a “bad” idea might even expose flaws in conventional ways of seeing problems and situations.

Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas:

- Copyright holder: William Heath Robinson. Appearance time: 1:30 - 1:33 Copyright license and terms: Public domain. Link: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/William_Heath_Robinson_Inventions_-_Page_142.png

- Copyright holder: Rev Stan. Appearance time: 1:40 - 1:44 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0 Link: As yummy as chocolate teapot courtesy of Choccywoccydoodah… _ Flickr.html

- Copyright holder: Fabel. Appearance time: 7:18 - 7:24 Copyright license and terms: CC BY-SA 3.0 Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hammer_nails_smithonian.jpg

- Copyright holder: Marcus Hansson. Appearance time: 05:54 - 05:58 Copyright license and terms: CC BY 2.0 Link: https://www.flickr.com/photos/marcus_hansson/7758775386

What Special Considerations Should Designers Have for CPS?

Creative problem solving isn’t the only process design teams consider when thinking of potential risks. Teams that involve themselves in ideation sessions can run into problems, especially if they aren’t aware of them. Here are the main areas to watch:

Bias is natural and human. Unfortunately, it can get in the way of user research and prevent a team from being truly creative and innovative. What’s more, it can utterly hinder the iterative process that should drive creative ideas to the best destinations. Bias takes many forms. It can rear its head without a design team member even realizing it. So, it’s vital to remember this and check it. One team member may examine an angle of the problem at hand and unconsciously view it through a lens. Then, they might voice a suggestion without realizing how they might have framed it for team members to hear. Another risk is that other team members might, for example, apply confirmation bias and overlook important points about potential solutions because they’re not in line with what they’re looking for.

Professor Alan Dix explains bias and fixation as obstacles in creative problem solving examples, and how to overcome them:

Conventionalism

Even in the most hopeful ideation sessions, there’s the risk that some team members may slide back to conventional ways to address a problem. They might climb back inside “the box” and not even realize it. That’s why it’s important to mindfully explore new idea territories around the situation under scrutiny and not merely toy with the notion while clinging to a default “traditional” approach, just because it’s the way the brand or others have “always done things.”

Dominant Personalities and Rank Pulling

As with any group discussion, it’s vital for the facilitator to ensure that everyone has the chance to contribute. Team members with “louder” personalities can dominate the discussions and keep quieter members from offering their thoughts. Plus, without a level playing field, it can be hard for more junior members to join in without feeling a sense of talking out of place or even a fear of reprisal for disagreeing with senior members.

Another point is that ideation sessions naturally involve asking many questions, which can bring on two issues. First, some individuals may over-defend their ideas as they’re protective of them. Second, team members may feel self-conscious as they might think if they ask many questions that it makes them appear frivolous or unintelligent. So, it’s vital for facilitators to ensure that all team members can speak up and ask away, both in divergent thinking sessions when they can offer ideas and convergent thinking sessions when they analyze others’ ideas.

Premature Commitment

Another potential risk to any creativity exercise is that once a team senses a solution is the “best” one, everyone can start to shut off and overlook the chance that an alternative may still arise. This could be a symptom of ideation fatigue or a false consensus that a proposed solution is infallible. So, it’s vital that team members keep open minds and try to catch potential issues with the best-looking solution as early as possible. The key is an understanding of the need for iteration—something that’s integral to the design thinking process, for example.

Overall, creative problem solving can help give a design team the altitude—and attitude—they need to explore the problem and solution spaces thoroughly. Team members can leverage a range of techniques to trawl through the hordes of possibilities that exist for virtually any design scenario. As with any method or tool, though, it takes mindful application and awareness of potential hazards to wield it properly. The most effective creative problem-solving sessions will be ones that keep “creative,” “problem” and “solving” in sharp focus until what emerges for the target audience proves to be more than the sum of these parts.

Learn More About Creative Problem Solving

Take our course, Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

Watch our Master Class Harness Your Creativity To Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

Read our piece, 10 Simple Ideas to Get Your Creative Juices Flowing .

Go to Exploring the Art of Innovation: Design Thinking vs. Creative Problem Solving by Marcino Waas for further details.

Consult Creative Problem Solving by Harrison Stamell for more insights.

Read The Osborn Parnes Creative Problem-Solving Process by Leigh Espy for additional information.

See History of the creative problem-solving process by Jo North for more on the history of Creative Problem Solving.

Questions about Creative Problem Solving

To start with, work to understand the user’s needs and pain points. Do your user research—interviews, surveys and observations are helpful, for instance. Analyze this data so you can spot patterns and insights. Define the problem clearly—and it needs to be extremely clear for the solution to be able to address it—and make sure it lines up with the users’ goals and your project’s objectives.

You and your design team might hold a brainstorming session. It could be a variation such as brainwalking—where you move about the room ideating—or brainwriting, where you write down ideas. Alternatively, you could try generating weird and wonderful notions in a bad ideas ideation session.

There’s a wealth of techniques you can use. In any case, engage stakeholders in brainstorming sessions to bring different perspectives on board the team’s trains of thought. What’s more, you can use tools like a Problem Statement Template to articulate the problem concisely.

Take our course, Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

Watch as Author and Human-Computer Interaction Expert, Professor Alan Dix explains important points about bad ideas:

Some things you might try are: 1. Change your environment: A new setting can stimulate fresh ideas. So, take a walk, visit a different room, or work outside.

2. Try to break the problem down into smaller parts: Focus on just one piece at a time—that should make the task far less overwhelming. Use techniques like mind mapping so you can start to visualize connections and come up with ideas.

3. Step away from work and indulge in activities that relax your mind: Is it listening to music for you? Or how about drawing? Or exercising? Whatever it is, if you break out of your routine and get into a relaxation groove, it can spark new thoughts and perspectives.

4. Collaborate with others: Discuss the problem with colleagues, stakeholders, or—as long as you don’t divulge sensitive information or company secrets—friends. It can help you to get different viewpoints, and sometimes those new angles and fresh perspectives can help unlock a solution.

5. Set aside dedicated time for creative thinking: Take time to get intense with creativity; prevent distractions and just immerse yourself in the problem as fully as you can with your team. Use techniques like brainstorming or the "Six Thinking Hats" to travel around the problem space and explore a wealth of angles.

Remember, a persistent spirit and an open mind are key; so, keep experimenting with different approaches until you get that breakthrough.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains important aspects of creativity and how to handle creative blocks:

Read our piece, 10 Simple Ideas to Get Your Creative Juices Flowing .

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains the Six Thinking Hats ideation technique.

Creative thinking is about coming up with new and innovative ideas by looking at problems from different angles—and imagining solutions that are truly fresh and unique. It takes an emphasis on divergent thinking to get “out there” and be original in the problem space. You can use techniques like brainstorming, mind mapping and free association to explore hordes of possibilities, many of which might be “hiding” in obscure corners of your—or someone on your team’s—imagination.

Critical thinking is at the other end of the scale. It’s the convergent half of the divergent-convergent thinking approach. In that approach, once the ideation team have hauled in a good catch of ideas, it’s time for team members to analyze and evaluate these ideas to see how valid and effective each is. Everyone strives to consider the evidence, draw logical connections and eliminate any biases that could be creeping in to cloud judgments. Accuracy, sifting and refining are watchwords here.

Watch as Professor Alan Dix explains divergent and convergent thinking:

The tools you can use are in no short supply, and they’re readily available and inexpensive, too. Here are a few examples:

Tools like mind maps are great ways to help you visualize ideas and make connections between them and elements within them. Try sketching out your thoughts and see how they relate to each other—you might discover unexpected gems, or germs of an idea that can splinter into something better, with more thought and development.

The SCAMPER technique is another one you can try. It can help you catapult your mind into a new idea space as you Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Reverse aspects of the problem you’re considering.

The “5 Whys” technique is a good one to drill down to root causes with. Once you’ve spotted a problem, you can start working your way back to see what’s behind it. Then you do the same to work back to the cause of the cause. Keep going; usually five times will be enough to see what started the other problems as the root cause.

Watch as the Father of UX Design, Don Norman explains the 5 Whys technique:

Read all about SCAMPER in our topic definition of it.

It’s natural for some things to get in the way of being creative in the face of a problem. It can be challenging enough to ideate creatively on your own, but it’s especially the case in group settings. Here are some common obstacles:

1. Fear of failure or appearing “silly”: when people worry about making mistakes or sounding silly, they avoid taking risks and exploring new ideas. This fear stifles creativity. That’s why ideation sessions like bad ideas are so valuable—it turns this fear on its head.

2. Rigid thinking: This can also raise itself as a high and thick barrier. If someone in an ideation session clings to established ways to approach problems (and potential solutions), it can hamper their ability to see different perspectives, let alone agree with them. They might even comment critically to dampen what might just be the brightest way forward. It takes an open mind and an awareness of one’s own bias to overcome this.

3. Time pressure and resource scarcity: When a team has tight deadlines to work to, they may rush to the first workable solution and ignore a wide range of possibilities where the true best solution might be hiding. That’s why stakeholders and managers should give everyone enough time—as well as any needed tools, materials and support—to ideate and experiment. The best solution is in everybody’s interest, after all.

It takes a few ingredients to get the environment just right for creative problem solving:

Get in the mood for creativity: This could be a relaxing activity before you start your session, or a warm-up activity in the room. Then, later, encourage short breaks—they can rejuvenate the mind and help bring on fresh insights.

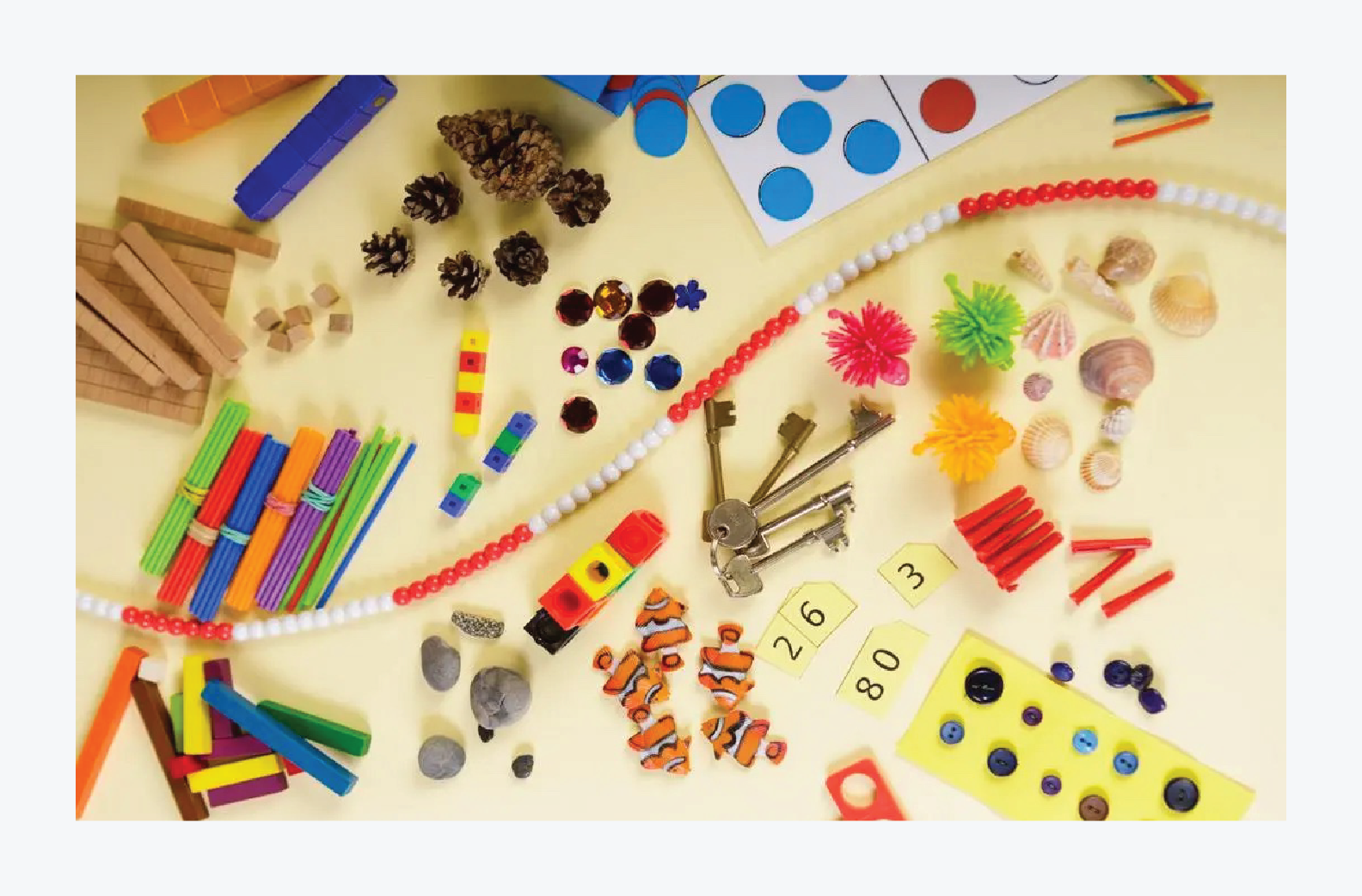

Get the physical environment just right for creating problem solving: You and your team will want a comfortable and flexible workspace—preferably away from your workstations. Make sure the room is one where people can collaborate easily and also where they can work quietly. A meeting room is good as it will typically have room for whiteboards and comfortable space for group discussion. Note: you’ll also need sticky notes and other art supplies like markers.

Make the atmosphere conducive for creative problem solving: Someone will need to play facilitator so everyone has some ground rules to work with. Encourage everyone to share ideas, that all ideas are valuable, and that egos and seniority have no place in the room. Of course, this may take some enforcement and repetition—especially as "louder" team members may try to dominate proceedings, anyway, and others may be self-conscious about sounding "ridiculous."

Make sure you’ve got a diverse team: Diversity means different perspectives, which means richer and more innovative solutions can turn up. So, try to include individuals with different backgrounds, skills and viewpoints—sometimes, non-technical mindsets can spot ideas and points in a technical realm, which experienced programmers might miss, for instance.

Watch our Master Class Harness Your Creativity To Design Better Products with Alan Dix, Professor, Author and Creativity Expert.

Ideating alone? Watch as Professor Alan Dix gives valuable tips about how to nurture creativity:

- Copyright holder: GerritR. Appearance time: 6:54 - 6:59 Copyright license and terms: CC-BY-SA-4.0 Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blick_auf_das_Dylan_Thomas_Boathouse_und_die_Trichterm%C3%BCndung_des_Taf,_Wales.jpg

Research plays a crucial role in any kind of creative problem solving, and in creative problem solving itself it’s about collecting information about the problem—and, by association, the users themselves. You and your team members need to have a well-defined grasp of what you’re facing before you can start reaching out into the wide expanses of the idea space.

Research helps you lay down a foundation of knowledge and avoid reinventing the wheel. Also, if you study existing solutions and industry trends, you’ll be able to understand what has worked before and what hasn't.

What’s more, research is what will validate the ideas that come out of your ideation efforts. From testing concepts and prototypes with real users, you’ll get precious input about your creative solutions so you can fine-tune them to be innovative and practical—and give users what they want in a way that’s fresh and successful.

Watch as UX Strategist and Consultant, William Hudson explains important points about user research:

First, it’s crucial for a facilitator to make sure the divergent stage of the creative problem solving is over and your team is on to the convergent stage. Only then should any analysis happen.

If others are being critical of your creative solutions, listen carefully and stay open-minded. Look on it as a chance to improve, and don’t take it personally. Indeed, the session facilitator should moderate to make sure everyone understands the nature of constructive criticism.

If something’s unclear, be sure to ask the team member to be more specific, so you can understand their points clearly.

Then, reflect on what you’ve heard. Is it valid? Something you can improve or explain? For example, in a bad ideas session, there may be an aspect of your idea that you can develop among the “bad” parts surrounding it.

So, if you can, clarify any misunderstandings and explain your thought process. Just stay positive and calm and explain things to your critic and other team member. The insights you’ve picked up may strengthen your solution and help to refine it.

Last—but not least—make sure you hear multiple perspectives. When you hear from different team members, chances are you’ll get a balanced view. It can also help you spot common themes and actionable improvements you might make.

Watch as Todd Zaki Warfel, Author, Speaker and Leadership Coach, explains how to present design ideas to clients, a valuable skill in light of discussing feedback from stakeholders.

Lateral thinking is a technique where you approach problems from new and unexpected angles. It encourages you to put aside conventional step-by-step logic and get “out there” to explore creative and unorthodox solutions. Author, physician and commentator Edward de Bono developed lateral thinking as a way to help break free from traditional patterns of thought.

In creative problem solving, you can use lateral thinking to come up with truly innovative ideas—ones that standard logical processes might overlook. It’s about bypassing these so you can challenge assumptions and explore alternatives that point you and your team to breakthrough solutions.

You can use techniques like brainstorming to apply lateral thinking and access ideas that are truly “outside the box” and what your team, your brand and your target audience really need to work on.

Professor Alan Dix explains lateral thinking in this video:

1. Baer, J. (2012). Domain Specificity and The Limits of Creativity Theory . The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46(1), 16–29. John Baer's influential paper challenged the notion of a domain-general theory of creativity and argued for the importance of considering domain-specific factors in creative problem solving. This work has been highly influential in shaping the understanding of creativity as a domain-specific phenomenon and has implications for the assessment and development of creativity in various domains.

2. Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The Standard Definition of Creativity . Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. Mark A. Runco and Gerard J. Jaeger's paper proposed a standard definition of creativity, which has been widely adopted in the field. They defined creativity as the production of original and effective ideas, products, or solutions that are appropriate to the task at hand. This definition has been influential in providing a common framework for creativity research and assessment.

1. Fogler, H. S., LeBlanc, S. E., & Rizzo, B. (2014). Strategies for Creative Problem Solving (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

This book focuses on developing creative problem-solving strategies, particularly in engineering and technical contexts. It introduces various heuristic problem-solving techniques, optimization methods, and design thinking principles. The authors provide a systematic framework for approaching ill-defined problems, generating and implementing solutions, and evaluating the outcomes. With its practical exercises and real-world examples, this book has been influential in equipping professionals and students with the skills to tackle complex challenges creatively.

2. De Bono, E. (1985). Six Thinking Hats . Little, Brown and Company.

Edward de Bono's Six Thinking Hats introduces a powerful technique for parallel thinking and decision-making. The book outlines six different "hats" or perspectives that individuals can adopt to approach a problem or situation from various angles. This structured approach encourages creative problem-solving by separating different modes of thinking, such as emotional, logical, and creative perspectives. De Bono's work has been highly influential in promoting lateral thinking and providing a practical framework for group problem solving.

3. Osborn, A. F. (1963). Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Problem-Solving (3rd ed.). Charles Scribner's Sons.

Alex F. Osborn's Applied Imagination is a pioneering work that introduced the concept of brainstorming and other creative problem-solving techniques. Osborn emphasized how important it is to defer judgment and generate a large quantity of ideas before evaluating them. This book laid the groundwork for many subsequent developments in the field of creative problem-solving, and it’s been influential in promoting the use of structured ideation processes in various domains.

Answer a Short Quiz to Earn a Gift

What is the first stage in the creative problem-solving process?

- Implementation

- Idea Generation

- Problem Identification

Which technique is commonly used during the idea generation stage of creative problem-solving?

- Brainstorming

- Prototyping

What is the main purpose of the evaluation stage in creative problem-solving?

- To generate as many ideas as possible

- To implement the solution

- To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of ideas

In the creative problem-solving process, what often follows after implementing a solution?

- Testing and Refinement

Which stage in the creative problem-solving process focuses on generating multiple possible solutions?

Better luck next time!

Do you want to improve your UX / UI Design skills? Join us now

Congratulations! You did amazing

You earned your gift with a perfect score! Let us send it to you.

Check Your Inbox

We’ve emailed your gift to [email protected] .

Literature on Creative Problem Solving

Here’s the entire UX literature on Creative Problem Solving by the Interaction Design Foundation, collated in one place:

Learn more about Creative Problem Solving

Take a deep dive into Creative Problem Solving with our course Creativity: Methods to Design Better Products and Services .

The overall goal of this course is to help you design better products, services and experiences by helping you and your team develop innovative and useful solutions. You’ll learn a human-focused, creative design process.

We’re going to show you what creativity is as well as a wealth of ideation methods ―both for generating new ideas and for developing your ideas further. You’ll learn skills and step-by-step methods you can use throughout the entire creative process. We’ll supply you with lots of templates and guides so by the end of the course you’ll have lots of hands-on methods you can use for your and your team’s ideation sessions. You’re also going to learn how to plan and time-manage a creative process effectively.

Most of us need to be creative in our work regardless of if we design user interfaces, write content for a website, work out appropriate workflows for an organization or program new algorithms for system backend. However, we all get those times when the creative step, which we so desperately need, simply does not come. That can seem scary—but trust us when we say that anyone can learn how to be creative on demand . This course will teach you ways to break the impasse of the empty page. We'll teach you methods which will help you find novel and useful solutions to a particular problem, be it in interaction design, graphics, code or something completely different. It’s not a magic creativity machine, but when you learn to put yourself in this creative mental state, new and exciting things will happen.

In the “Build Your Portfolio: Ideation Project” , you’ll find a series of practical exercises which together form a complete ideation project so you can get your hands dirty right away. If you want to complete these optional exercises, you will get hands-on experience with the methods you learn and in the process you’ll create a case study for your portfolio which you can show your future employer or freelance customers.

Your instructor is Alan Dix . He’s a creativity expert, professor and co-author of the most popular and impactful textbook in the field of Human-Computer Interaction. Alan has worked with creativity for the last 30+ years, and he’ll teach you his favorite techniques as well as show you how to make room for creativity in your everyday work and life.

You earn a verifiable and industry-trusted Course Certificate once you’ve completed the course. You can highlight it on your resume , your LinkedIn profile or your website .

All open-source articles on Creative Problem Solving

10 simple ideas to get your creative juices flowing.

- 4 years ago

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this page , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share Knowledge, Get Respect!

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this page.

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

- About us

Creative problem solving: basics, techniques, activities

Why is creative problem solving so important.

Problem-solving is a part of almost every person's daily life at home and in the workplace. Creative problem solving helps us understand our environment, identify the things we want or need to change, and find a solution to improve the environment's performance.

Creative problem solving is essential for individuals and organizations because it helps us control what's happening in our environment.

Humans have learned to observe the environment and identify risks that may lead to specific outcomes in the future. Anticipating is helpful not only for fixing broken things but also for influencing the performance of items.

Creative problem solving is not just about fixing broken things; it's about innovating and creating something new. Observing and analyzing the environment, we identify opportunities for new ideas that will improve our environment in the future.

The 7-step creative problem-solving process

The creative problem-solving process usually consists of seven steps.

1. Define the problem.

The very first step in the CPS process is understanding the problem itself. You may think that it's the most natural step, but sometimes what we consider a problem is not a problem. We are very often mistaken about the real issue and misunderstood them. You need to analyze the situation. Otherwise, the wrong question will bring your CPS process in the wrong direction. Take the time to understand the problem and clear up any doubts or confusion.

2. Research the problem.

Once you identify the problem, you need to gather all possible data to find the best workable solution. Use various data sources for research. Start with collecting data from search engines, but don't forget about traditional sources like libraries. You can also ask your friends or colleagues who can share additional thoughts on your issue. Asking questions on forums is a good option, too.

3. Make challenge questions.

After you've researched the problem and collected all the necessary details about it, formulate challenge questions. They should encourage you to generate ideas and be short and focused only on one issue. You may start your challenge questions with "How might I…?" or "In what way could I…?" Then try to answer them.

4. Generate ideas.

Now you are ready to brainstorm ideas. Here it is the stage where the creativity starts. You must note each idea you brainstorm, even if it seems crazy, not inefficient from your first point of view. You can fix your thoughts on a sheet of paper or use any up-to-date tools developed for these needs.

5. Test and review the ideas.

Then you need to evaluate your ideas and choose the one you believe is the perfect solution. Think whether the possible solutions are workable and implementing them will solve the problem. If the result doesn't fix the issue, test the next idea. Repeat your tests until the best solution is found.

6. Create an action plan.

Once you've found the perfect solution, you need to work out the implementation steps. Think about what you need to implement the solution and how it will take.

7. Implement the plan.

Now it's time to implement your solution and resolve the issue.

Top 5 Easy creative thinking techniques to use at work

1. brainstorming.

Brainstorming is one of the most glaring CPS techniques, and it's beneficial. You can practice it in a group or individually.

Define the problem you need to resolve and take notes of every idea you generate. Don't judge your thoughts, even if you think they are strange. After you create a list of ideas, let your colleagues vote for the best idea.

2. Drawing techniques

It's very convenient to visualize concepts and ideas by drawing techniques such as mind mapping or creating concept maps. They are used for organizing thoughts and building connections between ideas. These techniques have a lot in common, but still, they have some differences.

When starting a mind map, you need to put the key concept in the center and add new connections. You can discover as many joints as you can.

Concept maps represent the structure of knowledge stored in our minds about a particular topic. One of the key characteristics of a concept map is its hierarchical structure, which means placing specific concepts under more general ones.

3. SWOT Analysis

The SWOT technique is used during the strategic planning stage before the actual brainstorming of ideas. It helps you identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of your project, idea, or business. Once you analyze these characteristics, you are ready to generate possible solutions to your problem.

4. Random words

This technique is one of the simplest to use for generating ideas. It's often applied by people who need to create a new product, for example. You need to prepare a list of random words, expressions, or stories and put them on the desk or board or write them down on a large sheet of paper.

Once you have a list of random words, you should think of associations with them and analyze how they work with the problem. Since our brain is good at making connections, the associations will stimulate brainstorming of new ideas.

5. Storyboarding

This CPS method is popular because it tells a story visually. This technique is based on a step-creation process. Follow this instruction to see the storyboarding process in progress:

- Set a problem and write down the steps you need to reach your goal.

- Put the actions in the right order.

- Make sub-steps for some steps if necessary. This will help you see the process in detail.

- Evaluate your moves and try to identify problems in it. It's necessary for predicting possible negative scenarios.

7 Ways to improve your creative problem-solving skills

1. play brain games.

It's considered that brain games are an excellent way to stimulate human brain function. They develop a lot of thinking skills that are crucial for creative problem-solving.

You can solve puzzles or play math games, for example. These activities will bring you many benefits, including strong logical, critical, and analytical thinking skills.

If you are keen on playing fun math games and solving complicated logic tasks, try LogicLike online.