- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Does More Money Really Make Us More Happy?

- Elizabeth Dunn

- Chris Courtney

A big paycheck won’t necessarily bring you joy

Although some studies show that wealthier people tend to be happier, prioritizing money over time can actually have the opposite effect.

- But even having just a little bit of extra cash in your savings account ($500), can increase your life satisfaction. So how can you keep more cash on hand?

- Ask yourself: What do I buy that isn’t essential for my survival? Is the expense genuinely contributing to my happiness? If the answer to the second question is no, try taking a break from those expenses.

- Other research shows there are specific ways to spend your money to promote happiness, such as spending on experiences, buying time, and investing in others.

- Spending choices that promote happiness are also dependent on individual personalities, and future research may provide more individualized advice to help you get the most happiness from your money.

How often have you willingly sacrificed your free time to make more money? You’re not alone. But new research suggests that prioritizing money over time may actually undermine our happiness.

- ED Elizabeth Dunn is a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia and Chief Science Officer of Happy Money, a financial technology company with a mission to help borrowers become savers. She is also co-author of “ Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending ” with Dr. Michael Norton. Her TED2019 talk on money and happiness was selected as one of the top 10 talks of the year by TED.

- CC Chris Courtney is the VP of Science at Happy Money. He utilizes his background in cognitive neuroscience, human-computer interaction, and machine learning to drive personalization and engagement in products designed to empower people to take control of their financial lives. His team is focused on creating innovative ways to provide more inclusionary financial services, while building tools to promote financial and psychological well-being and success.

Partner Center

Can Money Really Buy Happiness?

Money and happiness are related—but not in the way you think..

Updated November 10, 2023 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- More money is linked to increased happiness, some research shows.

- People who won the lottery have greater life satisfaction, even years later.

- Wealth is not associated with happiness globally; non-material things are more likely to predict wellbeing.

- Money, in and of itself, cannot buy happiness, but it can provide a means to the things we value in life.

Money is a big part of our lives, our identities, and perhaps our well-being. Sometimes, it can feel like your happiness hinges on how much cash is in your bank account. Have you ever thought to yourself, “If only I could increase my salary by 12 percent, I’d feel better”? How about, “I wish I had an inheritance. How easier life would be!” I don’t blame you — I’ve had the same thoughts many times.

But what does psychological research say about the age-old question: Can money really buy happiness? Let’s take a brutally honest exploration of how money and happiness are (and aren’t) related. (Spoiler alert: I’ve got bad news, good news, and lots of caveats.)

Higher earners are generally happier

Over 10 years ago, a study based on Gallup Poll data on 1,000 people made a big headline in the news. It found that people with higher incomes report being happier... but only up to an annual income of $75,000 (equivalent to about $90,000 today). After this point, a high emotional well-being wasn’t directly correlated to more money. This seemed to show that once a persons’ basic (and some “advanced”) needs are comfortably met, more money isn’t necessary for well-being.

But a new 2021 study of over one million participants found that there’s no such thing as an inflection point where more money doesn’t equal more happiness, at least not up to an annual salary of $500,000. In this study, participants’ well-being was measured in more detail. Instead of being asked to remember how well they felt in the past week, month, or year, they were asked how they felt right now in the moment. And based on this real-time assessment, very high earners were feeling great.

Similarly, a Swedish study on lottery winners found that even after years, people who won the lottery had greater life satisfaction, mental health, and were more prepared to face misfortune like divorce , illness, and being alone than regular folks who didn’t win the lottery. It’s almost as if having a pile of money made those things less difficult to cope with for the winners.

Evaluative vs. experienced well-being

At this point, it's important to suss out what researchers actually mean by "happiness." There are two major types of well-being psychologists measure: evaluative and experienced. Evaluative well-being refers to your answer to, “How do you think your life is going?” It’s what you think about your life. Experienced well-being, however, is your answer to, “What emotions are you feeling from day to day, and in what proportions?” It is your actual experience of positive and negative emotions.

In both of these studies — the one that found the happiness curve to flatten after $75,000 and the one that didn't — the researchers were focusing on experienced well-being. That means there's a disagreement in the research about whether day-to-day experiences of positive emotions really increase with higher and higher incomes, without limit. Which study is more accurate? Well, the 2021 study surveyed many more people, so it has the advantage of being more representative. However, there is a big caveat...

Material wealth is not associated with happiness everywhere in the world

If you’re not a very high earner, you may be feeling a bit irritated right now. How unfair that the rest of us can’t even comfort ourselves with the idea that millionaires must be sad in their giant mansions!

But not so fast.

Yes, in the large million-person study, experienced well-being (aka, happiness) did continually increase with higher income. But this study only included people in the United States. It wouldn't be a stretch to say that our culture is quite materialistic, more so than other countries, and income level plays a huge role in our lifestyle.

Another study of Mayan people in a poor, rural region of Yucatan, Mexico, did not find the level of wealth to be related to happiness, which the participants had high levels of overall. Separately, a Gallup World Poll study of people from many countries and cultures also found that, although higher income was associated with higher life evaluation, it was non-material things that predicted experienced well-being (e.g., learning, autonomy, respect, social support).

Earned wealth generates more happiness than inherited wealth

More good news: For those of us with really big dreams of “making it” and striking it rich through talent and hard work, know that the actual process of reaching your dream will not only bring you cash but also happiness. A study of ultra-rich millionaires (net worth of at least $8,000,000) found that those who earned their wealth through work and effort got more of a happiness boost from their money than those who inherited it. So keep dreaming big and reaching for your entrepreneurial goals … as long as you’re not sacrificing your actual well-being in the pursuit.

There are different types of happiness, and wealth is better for some than others

We’ve been talking about “happiness” as if it’s one big thing. But happiness actually has many different components and flavors. Think about all the positive emotions you’ve felt — can we break them down into more specifics? How about:

- Contentment

- Gratefulness

...and that's just a short list.

It turns out that wealth may be associated with some of these categories of “happiness,” specifically self-focused positive emotions such as pride and contentment, whereas less wealthy people have more other-focused positive emotions like love and compassion.

In fact, in the Swedish lottery winners study, people’s feelings about their social well-being (with friends, family, neighbors, and society) were no different between lottery winners and regular people.

Money is a means to the things we value, not happiness itself

One major difference between lottery winners and non-winners, it turns out, is that lottery winners have more spare time. This is the thing that really makes me envious , and I would hypothesize that this is the main reason why lottery winners are more satisfied with their life.

Consider this simply: If we had the financial security to spend time on things we enjoy and value, instead of feeling pressured to generate income all the time, why wouldn’t we be happier?

This is good news. It’s a reminder that money, in and of itself, cannot literally buy happiness. It can buy time and peace of mind. It can buy security and aesthetic experiences, and the ability to be generous to your family and friends. It makes room for other things that are important in life.

In fact, the researchers in that lottery winner study used statistical approaches to benchmark how much happiness winning $100,000 brings in the short-term (less than one year) and long-term (more than five years) compared to other major life events. For better or worse, getting married and having a baby each give a bigger short-term happiness boost than winning money, but in the long run, all three of these events have the same impact.

What does this mean? We make of our wealth and our life what we will. This is especially true for the vast majority of the world made up of people struggling to meet basic needs and to rise out of insecurity. We’ve learned that being rich can boost your life satisfaction and make it easier to have positive emotions, so it’s certainly worth your effort to set goals, work hard, and move towards financial health.

But getting rich is not the only way to be happy. You can still earn health, compassion, community, love, pride, connectedness, and so much more, even if you don’t have a lot of zeros in your bank account. After all, the original definition of “wealth” referred to a person’s holistic wellness in life, which means we all have the potential to be wealthy... in body, mind, and soul.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A.. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. . Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2010.

Killingsworth, M. A. . Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year .. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021.

Lindqvist, E., Östling, R., & Cesarini, D. . Long-run effects of lottery wealth on psychological well-being. . The Review of Economic Studies. 2020.

Guardiola, J., González‐Gómez, F., García‐Rubio, M. A., & Lendechy‐Grajales, Á.. Does higher income equal higher levels of happiness in every society? The case of the Mayan people. . International Journal of Social Welfare. 2013.

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. . Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. . Journal of personality and social psychology. 2010.

Donnelly, G. E., Zheng, T., Haisley, E., & Norton, M. I.. The amount and source of millionaires’ wealth (moderately) predict their happiness . . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2018.

Piff, P. K., & Moskowitz, J. P. . Wealth, poverty, and happiness: Social class is differentially associated with positive emotions.. Emotion. 2018.

Jade Wu, Ph.D., is a clinical health psychologist and host of the Savvy Psychologist podcast. She specializes in helping those with sleep problems and anxiety disorders.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Sticking up for yourself is no easy task. But there are concrete skills you can use to hone your assertiveness and advocate for yourself.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

More Proof That Money Can Buy Happiness (or a Life with Less Stress)

When we wonder whether money can buy happiness, we may consider the luxuries it provides, like expensive dinners and lavish vacations. But cash is key in another important way: It helps people avoid many of the day-to-day hassles that cause stress, new research shows.

Money can provide calm and control, allowing us to buy our way out of unforeseen bumps in the road, whether it’s a small nuisance, like dodging a rainstorm by ordering up an Uber, or a bigger worry, like handling an unexpected hospital bill, says Harvard Business School professor Jon Jachimowicz.

“If we only focus on the happiness that money can bring, I think we are missing something,” says Jachimowicz, an assistant professor of business administration in the Organizational Behavior Unit at HBS. “We also need to think about all of the worries that it can free us from.”

The idea that money can reduce stress in everyday life and make people happier impacts not only the poor, but also more affluent Americans living at the edge of their means in a bumpy economy. Indeed, in 2019, one in every four Americans faced financial scarcity, according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The findings are particularly important now, as inflation eats into the ability of many Americans to afford basic necessities like food and gas, and COVID-19 continues to disrupt the job market.

Buying less stress

The inspiration for researching how money alleviates hardships came from advice that Jachimowicz’s father gave him. After years of living as a struggling graduate student, Jachimowicz received his appointment at HBS and the financial stability that came with it.

“My father said to me, ‘You are going to have to learn how to spend money to fix problems.’” The idea stuck with Jachimowicz, causing him to think differently about even the everyday misfortunes that we all face.

To test the relationship between cash and life satisfaction, Jachimowicz and his colleagues from the University of Southern California, Groningen University, and Columbia Business School conducted a series of experiments, which are outlined in a forthcoming paper in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science , The Sharp Spikes of Poverty: Financial Scarcity Is Related to Higher Levels of Distress Intensity in Daily Life .

Higher income amounts to lower stress

In one study, 522 participants kept a diary for 30 days, tracking daily events and their emotional responses to them. Participants’ incomes in the previous year ranged from less than $10,000 to $150,000 or more. They found:

- Money reduces intense stress: There was no significant difference in how often the participants experienced distressing events—no matter their income, they recorded a similar number of daily frustrations. But those with higher incomes experienced less negative intensity from those events.

- More money brings greater control : Those with higher incomes felt they had more control over negative events and that control reduced their stress. People with ample incomes felt more agency to deal with whatever hassles may arise.

- Higher incomes lead to higher life satisfaction: People with higher incomes were generally more satisfied with their lives.

“It’s not that rich people don’t have problems,” Jachimowicz says, “but having money allows you to fix problems and resolve them more quickly.”

Why cash matters

In another study, researchers presented about 400 participants with daily dilemmas, like finding time to cook meals, getting around in an area with poor public transportation, or working from home among children in tight spaces. They then asked how participants would solve the problem, either using cash to resolve it, or asking friends and family for assistance. The results showed:

- People lean on family and friends regardless of income: Jachimowicz and his colleagues found that there was no difference in how often people suggested turning to friends and family for help—for example, by asking a friend for a ride or asking a family member to help with childcare or dinner.

- Cash is the answer for people with money: The higher a person’s income, however, the more likely they were to suggest money as a solution to a hassle, for example, by calling an Uber or ordering takeout.

While such results might be expected, Jachimowicz says, people may not consider the extent to which the daily hassles we all face create more stress for cash-strapped individuals—or the way a lack of cash may tax social relationships if people are always asking family and friends for help, rather than using their own money to solve a problem.

“The question is, when problems come your way, to what extent do you feel like you can deal with them, that you can walk through life and know everything is going to be OK,” Jachimowicz says.

Breaking the ‘shame spiral’

In another recent paper , Jachimowicz and colleagues found that people experiencing financial difficulties experience shame, which leads them to avoid dealing with their problems and often makes them worse. Such “shame spirals” stem from a perception that people are to blame for their own lack of money, rather than external environmental and societal factors, the research team says.

“We have normalized this idea that when you are poor, it’s your fault and so you should be ashamed of it,” Jachimowicz says. “At the same time, we’ve structured society in a way that makes it really hard on people who are poor.”

For example, Jachimowicz says, public transportation is often inaccessible and expensive, which affects people who can’t afford cars, and tardy policies at work often penalize people on the lowest end of the pay scale. Changing those deeply-engrained structures—and the way many of us think about financial difficulties—is crucial.

After all, society as a whole may feel the ripple effects of the financial hardships some people face, since financial strain is linked with lower job performance, problems with long-term decision-making, and difficulty with meaningful relationships, the research says. Ultimately, Jachimowicz hopes his work can prompt thinking about systemic change.

“People who are poor should feel like they have some control over their lives, too. Why is that a luxury we only afford to rich people?” Jachimowicz says. “We have to structure organizations and institutions to empower everyone.”

[Image: iStockphoto/mihtiander]

Related reading from the Working Knowledge Archives

Selling Out The American Dream

- 25 Jun 2024

- Research & Ideas

Rapport: The Hidden Advantage That Women Managers Bring to Teams

- 11 Jun 2024

- In Practice

The Harvard Business School Faculty Summer Reader 2024

How transparency sped innovation in a $13 billion wireless sector.

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- 27 Jun 2016

These Management Practices, Like Certain Technologies, Boost Company Performance

- Social Psychology

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Happiness Economics: Can Money Buy Happiness?

It only costs a small amount, a slight risk, with the possibility of a substantial reward.

But will it make you happy? Will it give you long-lasting happiness?

Undoubtedly, there will be a temporary peak in happiness, but will all your troubles finally fade away?

That is what we will investigate today. We explore the economics of happiness and whether money can buy happiness. In this post, we will start by broadly exploring the topic and then look at theories and substantive research findings. We’ll even have a look at previous lottery winners.

For interested readers, we will list interesting books and podcasts for further enjoyment and share a few of our own happiness resources.

Ka-ching: Let’s get rolling!

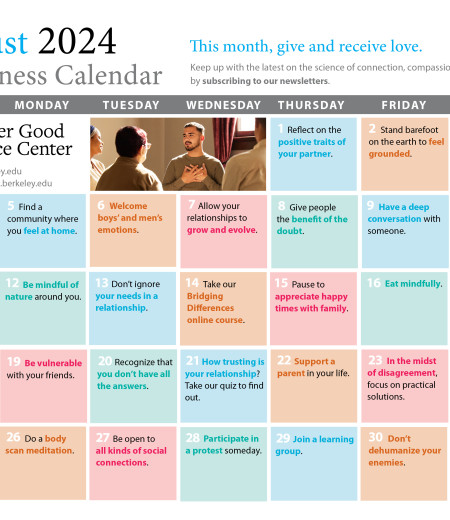

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

This Article Contains

What is happiness economics, theory of the economics of happiness, can money buy happiness 5 research findings, 6 fascinating books and podcasts on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Happiness economics is a field of economics that recognizes happiness and wellbeing as important outcome measures, alongside measures typically used, such as employment, education, and health care.

Economics emphasizes how specific economic/financial characteristics affect our wellbeing (Easterlin, 2004).

For example, does employment result in better health and longer lifespan, among other metrics? Do people in wealthier countries have access to better education and longer life spans?

In the last few decades, there has been a shift in economics, where researchers have recognized the importance of the subjective rating of happiness as a valuable and desirable outcome that is significantly correlated with other important outcomes, such as health (Steptoe, 2019) and productivity (DiMaria et al., 2020).

Broadly, happiness is a psychological state of being, typically researched and defined using psychological methods (Diener et al., 2003). We often measure it using self-report measures rather than objective measures that are less vulnerable to misinterpretation and error.

Including happiness in economics has opened up an entirely new avenue of research to explore the relationship between happiness and money.

Andrew Clark (2018) illustrates the variability in the term happiness economics with the following examples:

- Happiness can be a predictor variable, influencing our decisions and behaviors.

- Happiness might be the desired outcome, so understanding how and why some people are happier than others is essential.

However, the connection between our behavior and happiness must be better understood. Even though “being happy” is a desired outcome, people still make decisions that prevent them from becoming happier. For example, why do we choose to work more if our work does not make us happier? Why are we unhappy even if our basic needs are met?

An example of how happiness can influence decision-making

Sometimes, we might choose not to maximize a monetary or financial gain but place importance on other, more subjective outcomes.

Here’s a hypothetical example to illustrate: If faced with two jobs — one that pays well but will bring no joy and another that pays less but will bring much joy — some people would prefer to maximize their happiness over financial gain.

If this decision were evaluated using a utility framework where the only valued outcomes were practical, then the decision would seem irrational. However, this scenario suggests that psychological outcomes, such as the experience of happiness, are as crucial as other socio-economic outcomes.

Economists recognize that subjective wellbeing , or happiness, is an essential characteristic and sometimes a desirable outcome that can motivate our decision-making.

In the last few decades, economics has shifted to include happiness as a measurable and vital part of general wellbeing (Graham, 2005).

The consequence is that typical economic questions now also look at the impact of employment, finances, and other economic metrics on the subjective rating and experience of happiness at individual and country levels.

Happiness is such a vital outcome in society and economic activity that it must be involved in policy making. The subjective measure of happiness is as important as other typical measures used in economics.

Many factors can contribute to happiness. In this post, we consider the role of money. The relationship between happiness, or subjective wellbeing, and money is often assumed to be positive: More money means greater happiness.

However, the relationship between money and happiness is paradoxical: More money does not necessarily guarantee happiness (Graham, 2005; Killingsworth et al., 2023).

According to Killingsworth (as cited in Berger, 2023, para 16) “Money is just one of the many determinants of happiness. […] Money is not the secret to happiness, but it can probably help a bit.”

Indeed, happiness seems to be affected not just by how much money we have, but also how that amount compares to our peers (Clark et al., 2008), how we spend it (Van Boven & Gilovich, 2003), and the fact that even when the amount goes up, we eventually get used it (Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012).

This may be at odds with our everyday lived experience. Most of us choose to work longer hours or multiple jobs so that we make more money. However, what is the point of doing this if more money does not necessarily lead to the same amount of more happiness? Why do we seem to think that more money will make us happier?

History of the economics of happiness

The relationship between economics and happiness originated in the early 1970s. Brickman and Campbell (1971, as cited in Brickman et al., 1978) first argued that the typical outcomes of a successful life, such as wealth or income, had no impact on individual wellbeing.

Easterlin (1974) expanded these results and showed that although wealthier people tend to be happier than poor people in the same country, the average happiness levels within a country remained unchanged even as the country’s overall wealth increased.

The inconsistent relationship between happiness and income and its sensitivity to critical income thresholds make this topic so interesting.

There is some evidence that wealthier countries are happier than others, but only when comparing the wealthy with the poor (Easterlin, 1974; Graham, 2005).

As countries become wealthier, citizens report higher happiness, but this relationship is strongest when the starting point is poverty. Above a certain income threshold, happiness no longer increases (Diener et al., 1993).

Interestingly, people tend to agree on the amount of money needed to make them happy; but beyond a certain value, there is little increase in happiness (Haesevoets et al., 2022).

Measurement challenges

Measuring happiness accurately and reliably is challenging. Researchers disagree on what happiness means.

It is not the norm in economics to measure happiness by directly asking a participant how happy they are; instead, happiness is inferred through:

- Subjective wellbeing (Clark, 2018; Easterlin, 2004)

- A combination of happiness and life satisfaction (Bruni, 2007)

Furthermore, happiness can refer to an acute psychological state, such as feeling happy after a nice meal, or a lasting state similar to contentment (Nettle, 2005).

Researchers might use different definitions of happiness and ways to measure it, thus leading to contradictory results. For example, happiness might be used synonymously with subjective wellbeing and can refer to several things, including life satisfaction and financial satisfaction (Diener & Oishi, 2000).

Given the complex relationship between money and happiness, there are many potential reasons wealthier nations are not happier overall than poorer nations and that increasing the wealth of poorer nations does not guarantee that their happiness will increase too. So then, what could be done to increase happiness?

Download 3 Free Happiness Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover authentic happiness and cultivate subjective well-being.

Download 3 Free Happiness Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

What is the relationship between income/wealth and happiness? To answer that question, we looked at studies to see where and how money improves happiness, but we’ll also consider the limitations to the positive effect of income.

Money buys access; jobs boost happiness

Overwhelming evidence shows that wealth is correlated with measures of wellbeing.

Wealthier people have access to better healthcare, education, and employment, which in turn results in higher life satisfaction (Helliwell et al., 2012). A certain amount of wealth is needed to meet basic needs, and satisfying these needs improves happiness (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995).

Increasing happiness through improved quality of life is highest for poor households, but this is explained by the starting point. Access to essential services improves the quality of life, and in turn, this improves measures of wellbeing.

Most people gain wealth through employment; however, it is not just wealth that improves happiness; instead, employment itself has an important association with happiness. Happiness and employment are also significantly correlated with each other (Helliwell et al., 2021).

Lockdown on happiness

The World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2021) reports that unemployment increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this was accompanied by a marked decline in happiness and optimism.

The pandemic also changed how we evaluated certain aspects of our lives; for example, the relationship between income and happiness declined. After all, what is the use of money if you can’t spend it? In contrast, the association between happiness and having a partner increased (Helliwell et al., 2021).

Wealthier states smile more, but is it real?

If we took a snapshot of happiness and a country’s wealth, we would find that richer countries tend to have happier populations than poorer countries.

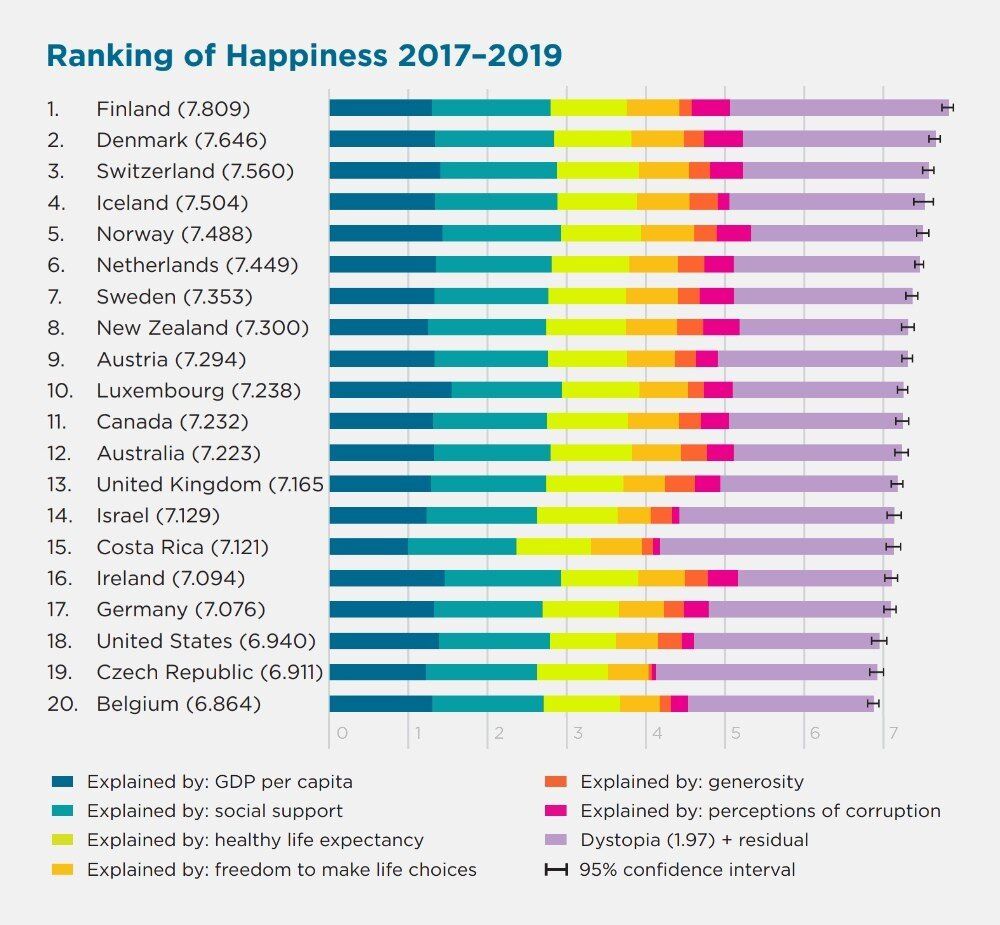

For example, based on the 2021 World Happiness Report, the top five happiest countries — which are also wealthy countries — are Finland, Iceland, Denmark, Switzerland, and the Netherlands (Helliwell et al., 2021).

In contrast, the unhappiest countries are those that tend to be emerging markets or have a lower gross domestic product (GDP), e.g., Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and India (Graham, 2005; Helliwell et al., 2021).

At face value, this makes sense: Poorer countries most likely have other factors associated with them, e.g., higher unemployment, more crime, and less political stability. So, based on this cross-sectional data, a country’s wealth and happiness levels appear to be correlated. However, over a more extended period, the relationship between happiness and GDP is nil (Easterlin, 2004).

That is, the subjective wellbeing of a population does not increase as a country becomes richer. Even though the wealth of various countries worldwide has increased over time, the overall happiness levels have not increased similarly or have remained static (Kahneman et al., 2006). This is known as a happiness–income paradox.

Easterlin (2004) posits four explanations for this finding:

- Societal and individual gains associated with increased wealth are concentrated among the extremely wealthy.

- Our degree of happiness is informed by how we compare to other people, and this relative comparison does not change as country-wide wealth increases.

- Happiness is not limited to only wealth and financial status, but is affected by other societal and political factors, such as crime, education, and trust in the government.

- Long-term satisfaction and contentment differ from short-term, acute happiness.

Kahneman et al. (2006) provide an alternative explanation centered on the method typically used by researchers. Specifically, they argue that the order of the questions asked to measure happiness and how these questions are worded have a focusing effect. Through the question, the participant’s attention to their happiness is sharpened — like a lens in a camera — and their happiness needs to be over- or underestimated.

Kahneman et al. (2006) also point out that job advancements like a raise or a promotion are often accompanied by an increase in salary and work hours. Consequently, high-paying jobs often result in less leisure time available to spend with family or on hobbies and can cause more unhappiness.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Not all that glitters is gold

Extensive research explored whether a sudden financial windfall was associated with a spike in happiness (e.g., Sherman et al., 2020). The findings were mixed. Sometimes, having more money is associated with increased life satisfaction and improved physical and mental health.

This boost in happiness, however, is not guaranteed, nor is it long. Sometimes, individuals even wish it had never happened (Brickman et al., 1978; Sherman et al., 2020).

Consider lottery winners. These people win sizable sums of money — typically more extensive than a salary increase — large enough to impact their lives significantly. Despite this, research has consistently shown that although lottery winners report higher immediate, short-term happiness, they do not experience higher long-term happiness (Sherman et al., 2020).

Here are some reasons for this:

- Previous everyday activities and experiences become less enjoyable when compared to a unique, unusual experience like winning the lottery.

- People habituate to their new lifestyle.

- A sudden increase in wealth can disrupt social relationships among friends and family members.

- Work and hobbies typically give us small nuggets of joy over a more extended period (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 2005). These activities can lose their meaning over a longer period, resulting in more unhappiness (Sherman et al., 2020; Brickman et al., 1978).

Sherman et al. (2020) further argue that lottery winners who decide to quit their job after winning, but do not fill this newly available time with some type of meaningful hobby or interest, are also more likely to become unhappy.

Passive activities do not provide the same happiness as work or hobbies. Instead, if lottery winners continue to take part in activities that give them meaning and require active engagement, then they can avoid further unhappiness.

Happiness: Is it temperature or climate?

Like most psychological research, part of the challenge is clearly defining the topic of investigation — a task made more daunting when the topic falls within two very different fields.

Nettle (2005) describes happiness as a three-tiered concept, ranging from short-lived but intense on one end of the spectrum to more abstract and deep on the other.

The first tier refers to transitory feelings of joy, like when one opens up a birthday present.

The second tier describes judgments about feelings, such as feeling satisfied with your job. The third tier is more complex and refers to life satisfaction.

Across research, different definitions are used: Participants are asked about feelings of (immediate) joy, overall life satisfaction, moments of happiness or satisfaction, and mental wellbeing . The concepts are similar but not identical, thus influencing the results.

Most books on happiness economics are textbooks. Although no doubt very interesting, they’re not the easy-reading books we prefer to recommend.

Instead, below you will find a range of books written by economists that explore happiness. These should provide a good springboard on the overall topic of happiness and what influences it, in case any of our readers want to pick up a more in-depth textbook afterward.

If you have a happiness book you would recommend, please let us know in the comments section.

1. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science – Richard Layard

Richard Layard, a lead economist based in London, explores in his book if and how money can affect happiness.

Layard does an excellent job of introducing topics from various fields and framing them appropriately for the reader.

The book is aimed at readers from varying academic and professional backgrounds, so no experience is needed to enjoy it.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Happiness by Design: Change What You Do, Not How You Think – Paul Dolan

This book has a more practical spin. The author explains how we can use existing research and theories to make small changes to increase our happiness.

Paul Dolan’s primary thesis is that practical things will have a bigger effect than abstract methods, and we should change our behavior rather than our thinking.

The book is a quick read (airport-perfect!), and Daniel Kahneman penned the foreword.

3. The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed and Happiness – Morgan Housel

This book is not necessarily about happiness economics, but it is close enough to the overall theme that it is worth mentioning.

Since most people are concerned with making more money, this book helps teach the reader why we make the decisions we do and how we make better decisions about our money.

This book is a worthwhile addition to any bookcase if you are interested in the relationship between finances and psychology in general.

4. Happiness: The Science Behind Your Smile – Daniel Nettle

If you are interested in happiness overall, then we recommend Happiness: The Science Behind Your Smile by Daniel Nettle, a professor of behavioral science at Newcastle University.

In this book, he takes a scientific approach to explaining happiness, starting with an in-depth exploration of the definition of happiness and some of its challenges.

The research that he presents comes from various fields, including social sciences, medicine, neurobiology, and economics.

Because of its small size, this book is perfect for a weekend away or to read on a plane.

5 & 6. Prefer to listen rather than read?

One of our favorite podcasts is Intelligence2, where leading experts in a particular field gather to debate a particular topic.

This show’s host, Dr. Laurie Santos, argues that we can increase our happiness by not hoarding our money for ourselves but by giving it to others instead. If you are interested in this episode , or any of the other episodes in the Happiness Lab podcast series, then head on over to their page.

There are several resources available at PositivePsychology.com for our readers to use in their professional and personal development.

In this section, you’ll find a few that should supplement any work on happiness and economics. Since the undercurrent of the topic is whether happiness can be improved through wealth, a few resources look at happiness overall.

Valued Living Masterclass

Although knowledge is power, knowing that money does not guarantee happiness does not mean that clients will suddenly feel fulfilled and satisfied with their lives.

For this reason, we recommend the Valued Living Masterclass , for professionals to help their clients find meaning in their lives. Rather than keeping up with the Joneses or chasing a high-paying job, professionals can help their clients connect with their inner meaning (i.e., their why ) as a way to find meaning and gain happiness.

Three free exercises

If you want to try it out before committing, look at the Meaning & Valued Living exercise pack , which includes three exercises for free.

Recommended reading

Read our post on Success Versus Happiness for further information on balancing happiness with success, in any domain . This topic is poignant for readers who conflate happiness and success, and will guide readers to better understand their relationship and how the two terms influence each other.

For readers who wonder about altruism , you would find it interesting that rather than hoarding, you can increase your happiness through volunteering and donating. In this post, the author, Dr. Jeremy Sutton, does a fabulous job of approaching altruism from various fields and provides excellent resources for further reading and real-life application.

Our last recommendation is for readers who want to know more about measuring subjective wellbeing and happiness . The post lists various tests and apps that can measure happiness and the overall history of how happiness was measured and defined. This is a good starting point for researchers or clinicians who want to explore happiness economics professionally.

17 happiness exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop strategies to boost their wellbeing, this collection contains 17 validated happiness and wellbeing exercises . Use them to help others pursue authentic happiness and work toward a life filled with purpose and meaning

17 Exercises To Increase Happiness and Wellbeing

Add these 17 Happiness & Subjective Well-Being Exercises [PDF] to your toolkit and help others experience greater purpose, meaning, and positive emotions.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

As you’ve seen in our article, the evidence overwhelmingly clarifies that money does not guarantee more happiness … well, long-term happiness.

Our happiness is relative since we compare ourselves to other people, and over time, as we become accustomed to our wealth, we lose all the happiness gains we made.

Money can ease financial and social difficulties; consequently, it can drastically improve people’s living conditions, life expectancy, and education.

Improvements in these outcomes have a knock-on effect on the overall experience of one’s life and the opportunities for one’s family and children. Nevertheless, better opportunities do not guarantee happiness.

Our intention with this post was to illustrate some complexities surrounding the relationship between money and happiness.

Knowing that money does not guarantee happiness, we recommend less expensive methods to improve one’s happiness:

- Spend time with friends.

- Cultivate hobbies and interests.

- Stay active and eat healthy.

- Try to live a meaningful life.

- Give some love (go smooch your partner or tickle your dog’s belly).

Diamonds might be a girl’s best friend, but money is a fair weather one, at best.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free .

- Berger, M. W. (2023, March 28). Does money buy happiness? Here’s what the research says . Knowledge at Wharton. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/does-money-buy-happiness-heres-what-the-research-says/

- Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 36 (8), 917.

- Bruni, L. (2007). Handbook on the economics of happiness . Edward Elgar.

- Clark, A. E. (2018). Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next? Review of Income and Wealth , 64 (2), 245–269.

- Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature , 46 (1), 95–144.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Abuhamdeh, S., & Nakamura, J. (2005). Flow. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 598–608). Guilford Publications.

- Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research , 28 , 195–223.

- Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. Culture and Subjective Well-Being , 185 , 218.

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology , 54 , 403–425.

- DiMaria, C. H., Peroni, C., & Sarracino, F. (2020). Happiness matters: Productivity gains from subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies , 21 (1), 139–160.

- Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). Academic Press.

- Easterlin, R. A. (2004). The economics of happiness. Daedalus , 133 (2), 26–33.

- Graham, C. (2005). The economics of happiness. World Economics , 6 (3), 41–55.

- Haesevoets, T., Dierckx, K., & Van Hiel, A. (2022). Do people believe that you can have too much money? The relationship between hypothetical lottery wins and expected happiness. Judgment and Decision Making , 17 (6), 1229–1254.

- Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (Eds.) (2012). World happiness report . The Earth Institute, Columbia University.

- Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., Sachs, J. D., & Neve, J. E. D. (2021). World happiness report 2021 .

- Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2006). Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science , 312 (5782), 1908–1910.

- Killingsworth, M. A., Kahneman, D., & Mellers, B. (2023). Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 120 (10), Article e2208661120.

- Nettle, D. (2005). Happiness: The science behind your smile . Oxford University Press.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). The challenge of staying happier: Testing the hedonic adaptation prevention model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 38 (5), 670–680.

- Sherman, A., Shavit, T., & Barokas, G. (2020). A dynamic model on happiness and exogenous wealth shock: The case of lottery winners. Journal of Happiness Studies , 21 , 117–137.

- Steptoe, A. (2019). Happiness and health. Annual Review of Public Health , 40 , 339–359.

- Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85 (6), 1193–1202.

- Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research , 34 , 33–68.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Embracing JOMO: Finding Joy in Missing Out

We’ve probably all heard of FOMO, or ‘the fear of missing out’. FOMO is the currency of social media platforms, eager to encourage us to [...]

The True Meaning of Hedonism: A Philosophical Perspective

“If it feels good, do it, you only live once”. Hedonists are always up for a good time and believe the pursuit of pleasure and [...]

Hedonic vs. Eudaimonic Wellbeing: How to Reach Happiness

Have you ever toyed with the idea of writing your own obituary? As you are now, young or old, would you say you enjoyed a [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (54)

- Coaching & Application (54)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (50)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (18)

- Mindfulness (41)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (31)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (42)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (25)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (33)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (37)

- Theory & Books (45)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (59)

3 Happiness Exercises Pack [PDF]

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Does More Money Make You Happier? Yes, But It's Complicated

Research says it can help, but there are a few caveats...

Verywell Mind / Getty Images

Why We Think Money Might Buy Happiness

The relationship between money and happiness.

- Limitations

- The Role Money Plays

- Finding Happiness Beyond Money

We've all heard the phrase: “Money can't buy happiness.” But how true is this, exactly? Growing up poor in rural Idaho, I often took comfort in this idea, reassuring myself that those with more money weren't necessarily any happier than I was. But sometimes I wondered: Am I just fooling myself?

Of course, money can't replace the deep joy and meaning we find in relationships and experiences. But there's no denying that financial security feels pretty darn good.

“Money can bring about happiness or a sense of satisfaction that can feel like happiness because it allows security and reduces constant financial anxiety and fear,” explains Sarah Whitmire , LPC-S, ATR-BC, a licensed professional counselor and founder of Whitmire Counseling and Supervision.

A Look Ahead

Many mental health experts will point out that money alone is no guarantee of happiness. Other factors like relationships, purpose, and personal growth have a more powerful impact.

But money does have some effect on happiness. How much? Keep reading on to learn more about this connection and whether a few extra dollars in your wallet truly translates to a joyful heart or if the key to happiness is something money can't buy.

When you think of happiness, things like friends, family, and life’s simple pleasures often come to mind—not money. So, where does the idea that money can buy happiness come from?

According to Kanchi Wijesekera , PhD, a licensed clinical psychologist and clinical director of the Milika Center for Therapy & Resilience , the origin of this idea is multifaceted. She notes that poverty itself is associated with more stress and a higher risk for mental health issues .

“There are some caveats, but it can be harder to feel happy when you're living under the chronic stress of poverty and all it entails,” she says. “You may not have the same time and energy to invest into your well-being as if you were to be financially well-off.”

She stresses that this doesn’t mean people with less financial means aren’t happy or can’t be happy. But it can be more challenging to feel happy compared to someone well-off.

Kristin Anderson , LCSW, a licensed psychotherapist and founder of Madison Square Psychotherapy , notes that the idea that money can buy happiness is often deeply engrained in many societies.

“These societies often equate financial success with a good life, and it can be easy to get caught up in that idea,” she says. “It’s the idea that financial resources can provide security, comfort, and opportunities, which are all associated with happiness.”

While money certainly does allow people to afford necessities that can improve their quality of life, such as healthcare and education, Anderson says these are no guarantee of greater happiness.

Money can enhance our living conditions, but it does not guarantee genuine happiness, which often comes from personal fulfillment, relationships, and emotional well-being.

Whitmire explains that modern consumer culture has a role in creating this idea. By promoting the idea that buying goods and services can make us happier, we’re more likely to believe that having more equals being more fulfilled.

Dr. Wijesekera notes that our own hard-wired tendencies help fuel these beliefs. Even when we are comfortable, we might think we’d be even happier if we just had a little bit more , whether it’s a new car, a better job, or a bigger house. (Hint: it doesn't).

Money alone doesn’t bring happiness , but researchers have found evidence supporting the connection between financial security and increased happiness and well-being.

According to a 2010 study, higher income does indeed help increase subjective life satisfaction as money can help alleviate emotional pain associated with challenging life events like divorce and poor health. Other research supports the link between financial security and happiness. In fact, studies show that security is particularly connected to happiness in societies where financial instability is more common.

A recent 2023 study has added another layer to this age-old debate by suggesting that higher income levels are connected to increased happiness.

The study found that happiness increases don't plateau once you hit a certain income. Instead, these benefits continue to grow, albeit at a slower pace.

That said, researchers do note that money isn’t the only factor contributing to happiness. But money undoubtedly plays a huge in creating security, access to resources, and growth opportunities, all of which impact your overall well-being.

The Limitations of Money in Achieving Happiness

It’s tempting to think that earning a bigger paycheck will be the secret to a fulfilling life. But try not to hinge your happiness on your bank account. Having more money may help increase happiness, yes, but can also bring about diminishing returns if the pursuit of extra cash affects your quality of life.

Studies suggest that beyond a certain income threshold—often cited around $75,000 to $100,000 annually—the additional happiness gains from extra income begin to level off. A boost in salary can make a big difference if you are struggling with basic needs. But you’re less likely to notice the extra income if you are already comfortable or doing well.

We like to think that money solves all our problems, but the pursuit of financial rewards can be more harmful than good, especially if it costs us healthy relationships and social connections. Sure, having extra cash would be great, but if it means sacrificing meaningful connections with others, are the benefits even worth it?

Our emotional health and well-being thrive on strong relationships and social interactions. What good are financial rewards if they're overshadowing your relationships and experiences?

I know money solves a lot of problems, but it can't buy a sense of purpose and meaning. Think of it like this: if your job is financially rewarding but emotionally draining, burnout is inevitable. You can't appreciate all your hard work and reap the financial benefits if you're emotionally and mentally exhausted. And no amount of money can make your brain or body feel any less tired.

The Role of Money in Different Aspects of Life

The ability to afford what we want and need is often linked to a higher quality of life. Feeling financially secure can reduce anxiety since you’re less worried about how you’ll pay for life’s expected and unexpected expenses.

“We know financial stability also affords improved access to healthcare, leisure activities, and opportunities for personal growth, all of which contribute to better mental and emotional well-being,” Dr. Wijesekera says.

Financial stress can leave you in a constant state of fight or flight mode , she adds. Access to more money and resources shifts you from survivor mode into a space where you can focus on hobbies, friends, or things that make you happy.

Not having to worry about money allows someone to think about their mental health. They have time and an advantage to think about how they are feeling and doing. They do not have a survivalist mentality and can spend time thinking about their pursuits and how they can thrive.

In other words, not having to stress about money is what contributes to happiness the most.

“Imagine the difference between constantly feeling stressed about finances versus having peace of mind knowing your needs are met,” Anderson says. “While money itself is not a direct source of happiness, the security it provides can create a more stable environment for mental health to flourish.”

While it’s important to recognize the relationship between money and happiness, it’s not a silver bullet. True happiness comes from the often intangible things money can’t guarantee including happy relationships, a sense of purpose, and feeling connected to a community.

Strategies for Finding Happiness Beyond Money

There’s no question that financial security can offer comfort and ease stress, but it’s also true that the things that bring us happiness are immaterial.

Some research-backed ways to bring more happiness to your life (that, fortunately, don’t cost money):

Cultivate Positive Relationships

Research has consistently shown that having strong, supportive relationships is essential for mental health and life satisfaction. One 2023 study, in particular, found a significant positive relationship between social support and increased happiness.

Focus on cultivating stronger relationships with your family, friends, and community to gain greater emotional support and a sense of belonging . “Engaging in meaningful interactions and shared activities with loved ones can create lasting memories and strengthen bonds, leading to a sense of fulfillment and happiness that material possessions often cannot match,” Whitmire says.

Dr. Wijesekera suggests building a supportive social network by participating in free community events, joining support groups, or volunteering.

Find Meaning and Purpose

Pursuing a sense of purpose and meaning in your life can also play a pivotal role in your happiness and life satisfaction.

Interestingly, some research suggests that feeling a sense of purpose might be connected to financial success as well. In one study, people who felt a sense of purpose in their work earned more money than those who felt their work lacked meaning. (Of course, earning more might also help make your work feel more meaningful, too).

Some experiences like hobbies, volunteer work, and engaging activities can help you find purpose. Dr. Wijesekera suggests exploring inexpensive or free hobbies such as drawing, reading library books, and cooking new recipes. Being open to new experiences can bring a profound sense of fulfillment and meaning that will ultimately help you feel happier.

Practice Gratitude

Gratitude can be a powerful antidote to feelings of sadness and negativity. That’s because regularly reflecting on the things you love and appreciate can help shift your focus away from what might be lacking. Research has found that gratitude interventions such as gratitude journaling increase positive moods, subjective happiness, and life satisfaction.

“Taking time each day to appreciate the good things in your life, big or small, can shift your focus from what you lack to what you have,” Anderson says. “By acknowledging the positive aspects of your life, you can significantly boost your mood and overall well-being.”

Tip From a Clinical Psychologist

Practicing habits such as maintaining a gratitude journal, verbal affirmations, giving thanks, or reflecting on daily blessings can reduce stress and profoundly elevate one's well-being.

Practice Mindfulness and Other Self-Care Strategies

Mindfulness and other self-care practices are powerful tools for fostering better emotional well-being. Mindfulness centers on being fully present and engaged in the present moment without worrying about the past or future.

One study found that mindfulness was associated with various positive outcomes including higher levels of happiness and decreased anxiety and depression. Other self-care activities like meditation , exercise, and adequate sleep are also low-cost or free ways to enhance happiness.

Dr. Wijesekera recommends trying free apps or online videos to learn meditation techniques. She also says that simple mindfulness exercises like deep breathing and mindful walking can be beneficial.

Spending Time in Nature

Dr. Wijesekera recommends spending time outdoors in nature to help alleviate some of the physiological effects of stress. She points to research on the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku or “ forest bathing .” This report found that spending just 20 minutes walking outdoors can lower your heart rate, blood pressure, and cortisol levels (a stress hormone).

“Visit local parks, hiking trails, or beaches, which are often free,” she says. “Gardening, even in small spaces or community gardens, can also be a low-cost way to connect with nature.”

Help Others

Anderson also recommends volunteering and finding ways to assist others in your life. “Volunteering your time or doing something kind for someone else can be incredibly rewarding,” she says. “It strengthens your sense of community and purpose, and seeing the positive impact you have on others can be a great source of happiness.”

While evidence suggests that money increases happiness, it isn’t the only thing that brings joy. Plenty of things bring fulfillment to your life that doesn’t involve boosting your financial bottom line.

Strengthening relationships, going after meaningful goals, and caring for yourself are all proven strategies for improving your happiness and well-being. Focusing on those areas can help you create a more fulfilling life, regardless of your finances.

Remember, happiness doesn't come from a single source. By incorporating these strategies into your life and building a fulfilling lifestyle, you can find joy and contentment, regardless of your financial situation.

The answer to the question of whether money can buy happiness is, well, complicated. Research shows that money can alleviate stress and improve life satisfaction. But those benefits will start to taper off after a certain point. A higher income level provides financial security and access to resources and opportunities but doesn't guarantee enduring happiness.

Happiness isn’t just about what’s in your bank account. Finding happiness is an ongoing process that involves many facets. And while there’s nothing wrong with pursuing financial well-being, don't sacrifice your mental health in the long run. Instead, find a balance between your financial pursuits and relationships and experiences. That, we say, is the best approach for unlocking lasting happiness.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 107 (38), 16489–16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Ek, C. (2017). Some causes are more equal than others? The effect of similarity on substitution in charitable giving . Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization , 136 , 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2017.01.007

Buttrick, N., & Oishi, S. (2023). Money and happiness: A consideration of history and psychological mechanisms . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 120 (13), e2301893120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2301893120

Beygi, Z., Solhi, M., Irandoost, S. F., & Hoseini, A. F. (2023). The relationship between social support and happiness in older adults referred to health centers in Zarrin Shahr, Iran . Heliyon , 9 (9), e19529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19529

Hill, P. L., Turiano, N. A., Mroczek, D. K., & Burrow, A. L. (2016). The value of a purposeful life: Sense of purpose predicts greater income and net worth . Journal of Research in Personality , 65 , 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.003

Cunha, L. F., Pellanda, L. C., & Reppold, C. T. (2019). Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: A randomized clinical trial . Frontiers in Psychology , 10 , 584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00584

Crego, A., Yela, J. R., Gómez-Martínez, M. Á., Riesco-Matías, P., & Petisco-Rodríguez, C. (2021). Relationships between mindfulness, purpose in life, happiness, anxiety, and depression: Testing a mediation model in a sample of women . International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 18 (3), 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18030925

Park, B. J., Tsunetsugu, Y., Kasetani, T., Kagawa, T., & Miyazaki, Y. (2010). The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (Taking in the forest atmosphere or forest bathing): Evidence from field experiments in 24 forests across Japan . Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine , 15 (1), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-009-0086-9

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Webinars

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

Research: Can Money Buy Happiness?

In his quarterly column, Francis J. Flynn looks at research that examines how to spend your way to a more satisfying life.

September 25, 2013

A boy looks at a toy train he received during an annual gift-giving event on Christmas Eve 2011. | Reuters/Jose Luis Gonzalez

What inspires people to act selflessly, help others, and make personal sacrifices? Each quarter, this column features one piece of scholarly research that provides insight on what motivates people to engage in what psychologists call “prosocial behavior” — things like making charitable contributions, buying gifts, volunteering one‘s time, and so forth. In short, it looks at the work of some of our finest researchers on what spurs people to do something on behalf of someone else.

In this column I explore the idea that many of the ways we spend money are prosocial acts — and prosocial expenditures may, in fact, make us happier than personal expenditures. Authors Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton discuss evidence for this in their new book, Happy Money: The Science of Smarter Spending . These behavioral scientists show that you can get more out of your money by following several principles — like spending money on others rather than yourself. Moreover, they demonstrate that these principles can be used not only by individuals, but also by companies seeking to create happier employees and more satisfying products.

According to Dunn and Norton, recent research on happiness suggests that the most satisfying way of using money is to invest in others. This can take a seemingly limitless variety of forms, from donating to a charity that helps strangers in a faraway country to buying lunch for a friend.

Witness Bill Gates and Warren Buffet, two of the wealthiest people in the world. On a March day in 2010, they sat in a diner in Carter Lake, Iowa, and hatched a scheme. They would ask America‘s billionaires to pledge the majority of their wealth to charity. Buffet decided to donate 99 percent of his, saying, “I couldn‘t be happier with that decision.”

And what about the rest of us? Dunn and Norton show how we all might learn from that example, regardless of the size of our bank accounts. Research demonstrating that people derive more satisfaction spending money on others than they do spending it on themselves spans poor and rich countries alike, as well as income levels. The authors show how this phenomenon extends over an extraordinary range of circumstances, from a Canadian college student purchasing a scarf for her mother to a Ugandan woman buying lifesaving malaria medication for a friend. Indeed, the benefits of giving emerge among children before the age of two.

Investing in others can make individuals feel healthier and wealthier, even if it means making yourself a little poorer to reap these benefits. One study shows that giving as little as $1 away can cause you to feel more flush.

Quote Investing in others can make you feel healthier and wealthier, even if it means making yourself a little poorer.

Dunn and Norton further discuss how businesses such as PepsiCo and Google and nonprofits such as DonorsChoose.org are harnessing these benefits by encouraging donors, customers, and employees to invest in others. When Pepsi punted advertising at the 2010 Superbowl and diverted funds to supporting grants that would allow people to “refresh” their communities, for example, more public votes were cast for projects than had been cast in the 2008 election. Pepsi got buzz, and the company‘s in-house competition also offering a seed grant boosted employee morale.

Could this altruistic happiness principle be applied to one of our most disputed spheres — paying taxes? As it turns out, countries with more equal distributions of income also tend to be happier. And people in countries with more progressive taxation (such as Sweden and Japan) are more content than those in countries where taxes are less progressive (such as Italy and Singapore). One study indicated that people would be happier about paying taxes if they had more choice as to where their money went. Dunn and Norton thus suggest that if taxes were made to feel more like charitable contributions, people might be less resentful having to pay them.

The researchers persuasively suggest that the proclivity to derive joy from investing in others may well be just a fundamental component of human nature. Thus the typical ratio we all tend to fall into of spending on self versus others — ten to one — may need a shift. Giving generously to charities, friends, and coworkers — and even your country — may well be a productive means of increasing well-being and improving our lives.

Research selected by Francis Flynn, Paul E. Holden Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Can we be candid how to communicate clearly and directly, directive speech vs. dialogue: how leaders communicate with clarity, balance, a dozen of our favorite insights stories of 2021, editor’s picks.

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Class of 2024 Candidates

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Marketing

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication