Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

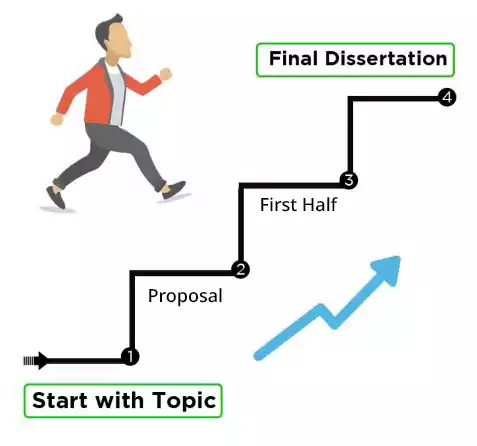

How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow

Published on November 11, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 20, 2023.

Choosing your dissertation topic is the first step in making sure your research goes as smoothly as possible. When choosing a topic, it’s important to consider:

- Your institution and department’s requirements

- Your areas of knowledge and interest

- The scientific, social, or practical relevance

- The availability of data and resources

- The timeframe of your dissertation

- The relevance of your topic

You can follow these steps to begin narrowing down your ideas.

Table of contents

Step 1: check the requirements, step 2: choose a broad field of research, step 3: look for books and articles, step 4: find a niche, step 5: consider the type of research, step 6: determine the relevance, step 7: make sure it’s plausible, step 8: get your topic approved, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about dissertation topics.

The very first step is to check your program’s requirements. This determines the scope of what it is possible for you to research.

- Is there a minimum and maximum word count?

- When is the deadline?

- Should the research have an academic or a professional orientation?

- Are there any methodological conditions? Do you have to conduct fieldwork, or use specific types of sources?

Some programs have stricter requirements than others. You might be given nothing more than a word count and a deadline, or you might have a restricted list of topics and approaches to choose from. If in doubt about what is expected of you, always ask your supervisor or department coordinator.

Start by thinking about your areas of interest within the subject you’re studying. Examples of broad ideas include:

- Twentieth-century literature

- Economic history

- Health policy

To get a more specific sense of the current state of research on your potential topic, skim through a few recent issues of the top journals in your field. Be sure to check out their most-cited articles in particular. For inspiration, you can also search Google Scholar , subject-specific databases , and your university library’s resources.

As you read, note down any specific ideas that interest you and make a shortlist of possible topics. If you’ve written other papers, such as a 3rd-year paper or a conference paper, consider how those topics can be broadened into a dissertation.

After doing some initial reading, it’s time to start narrowing down options for your potential topic. This can be a gradual process, and should get more and more specific as you go. For example, from the ideas above, you might narrow it down like this:

- Twentieth-century literature Twentieth-century Irish literature Post-war Irish poetry

- Economic history European economic history German labor union history

- Health policy Reproductive health policy Reproductive rights in South America

All of these topics are still broad enough that you’ll find a huge amount of books and articles about them. Try to find a specific niche where you can make your mark, such as: something not many people have researched yet, a question that’s still being debated, or a very current practical issue.

At this stage, make sure you have a few backup ideas — there’s still time to change your focus. If your topic doesn’t make it through the next few steps, you can try a different one. Later, you will narrow your focus down even more in your problem statement and research questions .

There are many different types of research , so at this stage, it’s a good idea to start thinking about what kind of approach you’ll take to your topic. Will you mainly focus on:

- Collecting original data (e.g., experimental or field research)?

- Analyzing existing data (e.g., national statistics, public records, or archives)?

- Interpreting cultural objects (e.g., novels, films, or paintings)?

- Comparing scholarly approaches (e.g., theories, methods, or interpretations)?

Many dissertations will combine more than one of these. Sometimes the type of research is obvious: if your topic is post-war Irish poetry, you will probably mainly be interpreting poems. But in other cases, there are several possible approaches. If your topic is reproductive rights in South America, you could analyze public policy documents and media coverage, or you could gather original data through interviews and surveys .

You don’t have to finalize your research design and methods yet, but the type of research will influence which aspects of the topic it’s possible to address, so it’s wise to consider this as you narrow down your ideas.

It’s important that your topic is interesting to you, but you’ll also have to make sure it’s academically, socially or practically relevant to your field.

- Academic relevance means that the research can fill a gap in knowledge or contribute to a scholarly debate in your field.

- Social relevance means that the research can advance our understanding of society and inform social change.

- Practical relevance means that the research can be applied to solve concrete problems or improve real-life processes.

The easiest way to make sure your research is relevant is to choose a topic that is clearly connected to current issues or debates, either in society at large or in your academic discipline. The relevance must be clearly stated when you define your research problem .

Before you make a final decision on your topic, consider again the length of your dissertation, the timeframe in which you have to complete it, and the practicalities of conducting the research.

Will you have enough time to read all the most important academic literature on this topic? If there’s too much information to tackle, consider narrowing your focus even more.

Will you be able to find enough sources or gather enough data to fulfil the requirements of the dissertation? If you think you might struggle to find information, consider broadening or shifting your focus.

Do you have to go to a specific location to gather data on the topic? Make sure that you have enough funding and practical access.

Last but not least, will the topic hold your interest for the length of the research process? To stay motivated, it’s important to choose something you’re enthusiastic about!

Most programmes will require you to submit a brief description of your topic, called a research prospectus or proposal .

Remember, if you discover that your topic is not as strong as you thought it was, it’s usually acceptable to change your mind and switch focus early in the dissertation process. Just make sure you have enough time to start on a new topic, and always check with your supervisor or department.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Formulating a main research question can be a difficult task. Overall, your question should contribute to solving the problem that you have defined in your problem statement .

However, it should also fulfill criteria in three main areas:

- Researchability

- Feasibility and specificity

- Relevance and originality

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A dissertation prospectus or proposal describes what or who you plan to research for your dissertation. It delves into why, when, where, and how you will do your research, as well as helps you choose a type of research to pursue. You should also determine whether you plan to pursue qualitative or quantitative methods and what your research design will look like.

It should outline all of the decisions you have taken about your project, from your dissertation topic to your hypotheses and research objectives , ready to be approved by your supervisor or committee.

Note that some departments require a defense component, where you present your prospectus to your committee orally.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 20). How to Choose a Dissertation Topic | 8 Steps to Follow. Scribbr. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/dissertation-topic/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to define a research problem | ideas & examples, what is a research design | types, guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- SPECIAL COLLECTIONS

- COVID-19 Library Updates

- Make Appointment

Research 101 (A How-to Guide): Step 1. Choose a topic

- Step 1. Choose a topic

- Step 2. Get background information

- Step 3. Create a search strategy

- Step 4. Find books and e-books

- Step 5. Find articles

- Step 6. Evaluate your sources

- Step 7. Cite your sources

Step 1. Choose a Topic

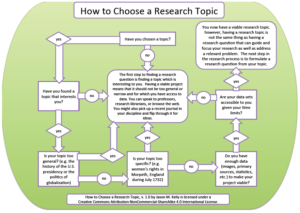

Choosing an interesting research topic can be challenging. This video tutorial will help you select and properly scope your topic by employing questioning, free writing, and mind mapping techniques so that you can formulate a research question.

Good Sources for Finding a Topic

- CQ Researcher This link opens in a new window Browse the "hot topics" on the right hand side for inspiration.

- 401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing, New York Times Great questions to consider for argumentative essays.

- ProCon.org Facts, news, and thousands of diverse opinions on controversial issues in a pro-con format.

- Room For Debate, New York Times This website, created by editorial staff from the New York Times, explores close to 1,500 news events and other timely issues. Knowledgeable outside contributors provide subject background and readers may contribute their own views. Great help for choosing a topic!

- US News & World Report: Debate Club Pro/Con arguments on current issues.

- Writing Prompts, New York Times New York Times Opinion articles that are geared toward students and invite comment.

Tips for Choosing a Topic

- Choose a topic that interests you!

- Pick a manageable topic, not too broad, not too narrow. Reading background info can help you choose and limit the scope of your topic.

- Review lecture notes and class readings for ideas.

- Check with your instructor to make sure your topic fits with the assignment.

Picking your topic IS research!

- Developing a Research Question Worksheet

Mind Mapping Tools

Mind mapping, a visual form of brainstorming, is an effective technique for developing a topic. Here are some free tools to create mind maps.

- Bubbl.us Free account allows you to save 3 mind maps, download as image or HTML, and share with others.

- Coggle Sign in with your Google account to create maps that you can download as PDF or PNG or share with others.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Step 2. Get background information >>

- Last Updated: Jul 22, 2024 3:42 PM

- URL: https://libguides.depaul.edu/research101

Scholar Speak

Choosing a research topic.

Photo of bulb by AbsolutVision , licensed under Unsplash

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Written by graduate student employees, Scholar Speak hopes to bridge the gap between the library and its students through instruction on the use of library services and resources.

Recent Posts

- Zines: Symposium, Library, and Interview May 24, 2024

- Discover Services Offered at Willis Library May 7, 2024

- Database Deep Dives: Part 2 May 2, 2024

Additional Links

Apply now Schedule a tour Get more info

Disclaimer | AA/EOE/ADA | Privacy | Electronic Accessibility | Required Links | UNT Home

Finding a Paper Topic

Introduction, current discussion and developments, working papers, academic journal articles, llm papers & sjd dissertations, faculty advisors, refining & finalizing a paper topic, getting help.

This guide is aimed at law students selecting a research paper topic. You should aim to find a specific, original topic that you find intriguing. The process for choosing a topic varies but might involve the following steps.

- Brainstorm about areas of interest. Think about interesting concepts from your courses, work history or life experience.

- Review current awareness sources like legal news, legal practice publications, or law blogs to generate more ideas and/or to identify legal developments related to your topic.

- Begin initial research using HOLLIS and Google Scholar.

- Refine your search phrases and start more specific research in academic articles and working papers. Try to zero in on current scholarly discussions on your topic.

- Reach out to potential faculty supervisors to discuss and refine the thesis statements you are considering.

Once you have finalized your topic, consider meeting with a librarian. Librarians can help you find and use targeted research sources for your specific project.

Current Awareness

Browsing and reading blogs, law firm posts, and legal news will help you generate ideas. Try some of the sources below to find current legal developments and controversies ahead of their formal analysis in traditional scholarly sources such as books or law review articles.

- Bloomberg Law Law Review Resources: Find a Topic (HLS Only) Find circuit splits, Court developments, browse developments by practice area.

- Lexis Legal News Hub (HLS Only) Legal news from Law360, Mealey's, MLex & FTCWatch.

- Westlaw Legal Blogs (HLS Only) Aggregates content from many blogs. Browse or search.

- JD Supra Content from law firms. Browse or search.

Working Papers Repositories

After browsing current awareness, digging into working papers is a good next step. Working papers (preprints) are scholarly articles not yet published or in final form. Most U.S.-based law professors deposit their scholarship in these working paper repositories. Make sure to order results by date to explore the current academic conversation on a topic.

- SSRN (Social Science Research Network) A main source for working papers in law and social sciences. Accessing it through HOLLIS will allow you to set up an individual account and subscribe to email alerts.

- Law Commons Open access working paper repository. Browse by topic, author, and institutional affiliation.

- NBER Working Papers The National Bureau of Economic Research hosts working papers related to finance, banking, and law and economics.

- OSF Preprints Multidisciplinary repository more global in scope than those listed above.

Academic Literature

As you zero in on a topic, it is time to explore the legal academic literature. If your topic is not solely legal but falls in other academic disciplines like economics, sociology, political science, etc. begin with HOLLIS and Google Scholar as you explore and refine your topic.

Law Journal Articles

- Hein Online Law Journal Library (Harvard Key) Provides pdf format for law review articles in 3200 law journals. For most, coverage is from inception. Includes a good collection of non-U.S. journals.

- Lexis+ Law Reviews and Journals (HLS Only)

- Westlaw Law Reviews & Journals (HLS Only)

- LegalTrac Topic Finder (HLS only) LegalTrac is an index (descriptions of articles) and has some full text. It is included here for its topic finder tool which allows you to put in some general topics, and then refine the terms to generate a list of linked articles.

Academic Articles, Books and Book Chapters

- HOLLIS Catalog and Articles Beyond finding the books, ebooks, and journals owned by the Harvard Library system, using HOLLIS in its default mode (Catalog & Articles) allows you to find articles from many subscription sources. Before settling on a paper topic, running some searches in HOLLIS is a must.

- Harvard Google Scholar Google Scholar limits results to scholarly research publications. Harvard Google Scholar will (usually) allow you to link through to content from Harvard-subscribed sources.

Dissertations, Theses and Papers

As you refine your topic ideas, it is often helpful to browse the titles of dissertations and papers by SJDs, LLMs, or JD students, either generally, or those which touch on your subject area. This can help you understand how people have framed their research topic in a discrete, specific way.

- Proquest Dissertations and Theses (Harvard Key) Dissertations and theses from many academic institutions but does not include any HLS SJD dissertations or LL.M. papers from recent years.

- HLS Dissertations, Theses, and JD Papers Guide to finding HLS student papers in the library's collection using HOLLIS. (Print format up to 2023, electronic format in 2024 and thereafter).

- Global ETD Search (Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations) Global repository of theses and dissertations.

Tips on Finding a Faculty Advisor

HLS LL.M. papers require faculty supervision. Discussing your topic with a potential faculty supervisor can be an important step in solidifying your topic ideas.

- HLS Faculty Directory Search or browse by area of interest or name. Faculty supervisors must have a teaching appointment during the semester in which the paper is to be turned in.

- HLS Course Catalog Determine who is currently teaching in a particular subject area.

- HLS Faculty Bibliography This collective list of publications of the HLS faculty can be searched and limited by date.

Tips for Refining a Topic

As you’ve browsed blogs, news, law reviews and other LL.M. papers, you have hopefully arrived at some topic ideas that are original and will hold your continued interest. It is also important to refine your paper topic to a discrete, narrow idea. To make sure your topic is sufficiently narrow, please see the resources included in the HLS Graduate Program Writing Resources Canvas Site . See especially:

- The Six-Point Exercise in the module “Developing Your Proposal and Drafting Your Paper”

- Worksheets for Senior Thesis Writers and Others in the module “Recommended Materials on Writing”

- Archetypal Legal Scholarship: A Field Guide, 63 J. Legal Educ. 65 (2013) HLS Prof. Minow's article defines the different types of papers in the legal literature. It is helpful to read her framework as you finalize your paper topic.

- Academic Legal Writing: Law Review Articles, Student Notes, Seminar Papers, and Getting on Law Review UCLA Prof. Eugene Volokh's book on legal writing.

- Choosing a Claim (Excerpt from above book.) This is a publicly available excerpt of the book. Chapter begins on p. 25 of this pdf.

Contact Us!

Ask Us! Submit a question or search our knowledge base.

Chat with us! Chat with a librarian (HLS only)

Email: [email protected]

Contact Historical & Special Collections at [email protected]

Meet with Us Schedule an online consult with a Librarian

Hours Library Hours

Classes View Training Calendar or Request an Insta-Class

Text Ask a Librarian, 617-702-2728

Call Reference & Research Services, 617-495-4516

- Last Updated: May 30, 2024 12:13 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/law/findingapapertopic

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

info This is a space for the teal alert bar.

notifications This is a space for the yellow alert bar.

Research Process

- Brainstorming

- Explore Google This link opens in a new window

- Explore Web Resources

- Explore Background Information

- Explore Books

- Explore Scholarly Articles

- Narrowing a Topic

- Primary and Secondary Resources

- Academic, Popular & Trade Publications

- Scholarly and Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Grey Literature

- Clinical Trials

- Evidence Based Treatment

- Scholarly Research

- Database Research Log

- Search Limits

- Keyword Searching

- Boolean Operators

- Phrase Searching

- Truncation & Wildcard Symbols

- Proximity Searching

- Field Codes

- Subject Terms and Database Thesauri

- Reading a Scientific Article

- Website Evaluation

- Article Keywords and Subject Terms

- Cited References

- Citing Articles

- Related Results

- Search Within Publication

- Database Alerts & RSS Feeds

- Personal Database Accounts

- Persistent URLs

- Literature Gap and Future Research

- Web of Knowledge

- Annual Reviews

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- Finding Seminal Works

- Exhausting the Literature

- Finding Dissertations

- Researching Theoretical Frameworks

- Research Methodology & Design

- Tests and Measurements

- Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publication

- Learn the Library This link opens in a new window

Finding a Research Topic

Which step of the research process takes the most time?

A. Finding a topic B. Researching a topic C. Both

How did you answer the above question? Do you spend most of your efforts actually researching a topic, or do you spend a lot of time and energy finding a topic? Ideally, you’ll want to spend fairly equal amounts of effort on both. Finding an appropriate and manageable topic can sometimes be just as hard as researching a topic.

A good research topic will have a body of related research which is accessible and manageable. Identifying a topic with these characteristics at the beginning of the research process will ultimately save you time.

Finding a research topic that is interesting, relevant, feasible, and worthy of your time may take substantial effort so you should be prepared to invest your time accordingly. Considering your options, doing some background work on each option, and ultimately settling on a topic that is manageable will spare you many of the frustrations that come from attempting research on a topic that, for whatever reason, may not be appropriate.

Remember that as you are searching for a research topic you will need to be able to find enough information about your topic(s) in a book or scholarly journal. If you can only find information about your topic(s) in current event sources (newspapers, magazines, etc.) then the topic might be too new to have a large body of published scholarly information. If this is the case, you may want to reconsider the topic(s).

So how do you find a research topic? Unfortunately there’s no directory of topics that you pick and choose from, but there are a few relatively easy techniques that you can use to find a relevant and manageable topic. A good starting point may be to view the Library's Resources for Finding a Research Topic Workshop below.

The sub-pages in this section (on the left-hand menu) offer various tips for where and how to locate resources to develop your research topic. And for additional information on selecting a research topic, see the resources below.

- Defining a Topic - SAGE Research Methods

- Develop My Research Idea - Academic Writer Note: You MUST create an Academic Writer account AND start a paper in order to access this tool. Once you have done so, open a paper and click Research Lab Book in the left navigation menu.

- The Process for Developing Questions - ASC Guide

Finding & Staying Current on a Research Topic Webinar

This webinar will introduce you to resources which can be used to locate potential topics for a research paper or dissertation, including websites, reference books, and scholarly articles.

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Brainstorming >>

- Last Updated: Jul 19, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchprocess

© Copyright 2024 National University. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy | Consumer Information

- Boston University Libraries

Choosing a Research Topic

- Starting Points

Where to Find Ideas

Persuasive paper assignments, dissertations and theses.

- From Idea to Search

- Make It Manageable

If you are starting a research project and would like some help choosing the best topic, this guide is for you. Start by asking yourself these questions:

What does your instructor require? What interests you? What information sources can support your research? What is doable in the time you have?

While keeping these questions in mind, find suggestions in this guide to select a topic, turn that topic into a database search, and make your research manageable. You will also find more information in our About the Research Process guide.

Whether your instructor has given a range of possible topics to you or you have to come up with a topic on your own, you could benefit from these activities:

Consult Course Materials If a reading, film, or other resource is selected by your instructor, the subject of it is important to the course. You can often find inspiration for a paper in these materials.

- Is a broad topic presented? You can focus on a specific aspect of that topic. For example, if your class viewed a film on poverty in the United States, you could look at poverty in a specific city or explore how poverty affects Americans of a specific gender, ethnic group, or age range.

- Are experts presented, quoted, or cited? Look up their work in BU Libraries Search or Google Scholar .

Use Background Sources If you've identified one or more topics you'd like to investigate further, look them up in an encyclopedia, handbook, or other background information source. Here are some good places to start.

Online version of Encyclopædia Britannica along Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary and Thesaurus, magazines and periodicals and other reference sources.

- Oxford Reference This link opens in a new window Published by Oxford University Press, it is a fully-indexed, cross-searchable database containing dictionaries, language reference and subject reference works.

Explore the Scholarly Literature Ask your instructor or a librarian to guide you to the top journals in the field you're studying. Scanning the tables of contents within these journals will provide some inspiration for your research project. As a bonus, each of the articles in these journals will have a bibliography that will lead you to related articles, books, and other materials.

Ask a Librarian We are here to help you! You can request a consultation or contact us by email or through our chat service . We can help you identify what interests you, where to find more about it, and how to narrow the topic to something manageable in the time you have.

If your assignment entails persuading a reader to adopt a position, you can conduct your research in the same way you would with any other research project. The biggest mistake you can make, however, is choosing a position before you start your research. Instead, the information you consult should inform your position. Researching before choosing a position is also much easier; you will be able to explore all sides of a topic rather than limiting yourself to one.

If you would like examples of debates on controversial topics, try these resources:

Covers the most current and controversial issues of the day with summaries, pros and cons, bibliographies and more. Provides reporting and analysis on issues in the news, including issues relating to health, social trends, criminal justice, international affairs, education, the environment, technology, and the economy.

- New York Times: Room for Debate Selections from the New York Times' opinion pages.

- ProCon.org Created by Britannica, this site exposes readers to two sides of timely arguments. Each article includes a bibliography of suggested resources.

If you are writing a dissertation or thesis, you will find more specialized information at our Guide for Writers of Theses and Dissertations .

If you would like to find published dissertations and theses, please use this database:

This database contains indexing and abstracts of American doctoral dissertations accepted at accredited institutions since 1861 and a selection from other countries. Masters level theses are included selectively.

- Next: From Idea to Search >>

- Last Updated: Jul 16, 2024 9:04 AM

- URL: https://library.bu.edu/choosing-a-topic

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Find a Topic for Your Research Paper

Last Updated: September 12, 2023 References

This article was co-authored by Matthew Snipp, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . C. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. This article has been viewed 97,276 times.

Sometimes, finding a topic for a research paper can be the most challenging part of the whole process. When you're looking out at a field brimming with possibilities, it's easy to get overwhelmed. Lucky for you, we here at wikiHow have come up with a list of ways to pick that topic that will take you from the more vague brainstorming all the way to your specific, perfectly focused research question and thesis.

Review your course materials.

- If your textbook has discussion questions at the end of each chapter, these can be great to comb through for potential research paper topic ideas.

- Look at any recommended reading your instructor has suggested—you might find ideas there as well.

Search hot issues in your field of study.

- Think about current events that touch on your field of study as well. For example, if you're writing a research paper for a sociology class, you might want to write something related to race in America or the Black Lives Matter movement.

- Other instructors in the same department or field might also have ideas for you. Don't be afraid to stop in during their office hours and talk or send them an email, even if you've never had them for a class.

Go for a walk to get your brain going.

- If you want to walk with a friend and discuss topic ideas as you walk, that can help too. Sometimes, you'll come up with new things when you can bounce your ideas off someone else.

Ask your family or friends for input.

- People who aren't really familiar with the general subject you're researching can be helpful too! Because they aren't making many assumptions, they might bring up something you'd overlooked or not thought about before.

Free-write on topic ideas to find your passion.

- Having a personal interest in the topic will keep you from getting bored. You'll do better research—and write a better paper—if you're excited about the topic itself.

Read background information on your favorites.

- Ideally, based on your background research, you'll be able to choose one of the topics that interests you the most. If you still can't narrow it down, keep reading!

- Even though you wouldn't want to use them as sources for your actual paper, sources like Wikipedia can be excellent for getting background information about a topic.

Identify important words to use as keywords.

- For example, if you've chosen environmental regulations as a topic, you might also include keywords such as "conservation," "pollution," and "nature."

Do preliminary research using your keywords.

- Your results might also suggest other keywords you can search to find more sources. Searching for specific terminology used in articles you find often leads to other articles.

- Check the bibliography of any papers you find to pick up some other sources you might be able to use.

Limit a broad topic.

- For example, suppose you decided to look at race relations in the US during the Trump administration. If you got too many results, you might narrow your results to a single US city or state.

- Keep in mind how long your research paper will ultimately be. For example, if there's an entire book written on a topic you want to write a 20-page research paper on, it's probably too broad.

Expand a topic that's too narrow.

- For example, suppose you wanted to research the impact of a particular environmental law on your hometown, but when you did a search, you didn't get any quality results. You might expand your search to encompass the entire state or region, rather than just your hometown.

Do more in-depth research to fine-tune your topic.

- For example, you might do an initial search and get hundreds of results back and decide your topic is too broad. Then, when you limit it, you get next to nothing and figure out you've narrowed it too much, so you have to broaden it a little bit again.

- Stay flexible and keep going until you've found that happy medium that you think will work for your paper.

Formulate the question you'll answer in your paper.

- For example, your research question might be something like "How did environmental regulations affect the living conditions of people living near paper mills?" This question covers "who" (people living near paper mills), "what" (living conditions), "where" (near paper mills), and "why" (environmental regulations).

Build a list of potential sources.

- At this point, your list is still a "working" list. You won't necessarily use all the sources you find in your actual paper.

- Building a working list of sources is also helpful if you want to use a source and can't immediately get access to it. If you have to get it through your professor or request it from another library, you have time to do so.

Develop your thesis.

- For example, suppose your research question is "How did environmental regulations affect the living conditions of people living near paper mills?" Your thesis might be something like: "Environmental regulations improved living conditions for people living around paper mills."

- As another example, suppose your research question is "Why did hate crimes spike in the US from 2017 to 2020?" Your thesis might be: "A permissive attitude towards racial supremacy caused a spike in hate crimes in the US from 2017 to 2020."

- Keep in mind, you don't have to prove that your thesis is correct. Proving that your thesis was wrong can make for an even more compelling research paper, especially if your thesis follows conventional wisdom.

Expert Q&A

- If you've been given a list of topics but you come up with something different that you want to do, don't be afraid to talk to your instructor about it! The worst that will happen is that they'll make you choose something from the list instead. [11] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185905

- ↑ https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/08/how-steve-jobs-odd-habit-can-help-you-brainstorm-ideas.html

- ↑ https://emory.libanswers.com/faq/44525

- ↑ https://emory.libanswers.com/faq/44524

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/research_papers/choosing_a_topic.html

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Jimmy Bhatt

Oct 17, 2020

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Selecting a Research Topic: Refine your topic

- Refine your topic

- Background information & facts

Narrow your topic's scope

Too much information? Make your results list more manageable. Less, but more relevant, information is key. Here are some options to consider when narrowing the scope of your paper:

- Theoretical approach : Limit your topic to a particular approach to the issue. For example, if your topic concerns cloning, examine the theories surrounding of the high rate of failures in animal cloning.

- Aspect or sub-area : Consider only one piece of the subject. For example, if your topic is human cloning, investigate government regulation of cloning.

- Time : Limit the time span you examine. For example, on a topic in genetics, contrast public attitudes in the 1950's versus the 1990's.

- Population group : Limit by age, sex, race, occupation, species or ethnic group. For example, on a topic in genetics, examine specific traits as they affect women over 40 years of age.

- Geographical location : A geographic analysis can provide a useful means to examine an issue. For example, if your topic concerns cloning, investigate cloning practices in Europe or the Middle East.

Broaden your topic

Not finding enough information? Think of related ideas, or read some background information first. You may not be finding enough information for several reasons, including:

- Your topic is too specific . Generalize what you are looking for. For example: if your topic is genetic diversity for a specific ethnic group in Ghana, Africa, broaden your topic by generalizing to all ethnic groups in Ghana or in West Africa.

- Your topic is too new for anything substantive to have been written. If you're researching a recently breaking news event, you are likely to only find information about it in the news media. Be sure to search databases that contain articles from newspapers. If you are not finding enough in the news media, consider changing your topic to one that has been covered more extensively.

- You have not checked enough databases for information . Search Our Collections to find other databases in your subject area which might cover the topic from a different perspective. Also, use excellent searching techniques to ensure you are getting the most out of every database.

- You are using less common words or too much jargon to describe your topic. Use a thesaurus to find other terms to represent your topic. When reading background information, note how your topic is expressed in these materials. When you find citations in an article database, see how the topic is expressed by experts in the field.

Once you have a solid topic, formulate your research question or hypothesis and begin finding information.

If you need guidance with topic formulation, Ask Us ! Library staff are happy to help you focus your ideas.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Background information & facts >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2021 2:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

How to Select a Research Topic: A Step-by-Step Guide

by Antony W

June 6, 2024

Learning how to select a research topic can be the difference between failing your assignment and writing a comprehensive research paper. That’s why in this guide we’ll teach you how to select a research topic step-by-step.

You don’t need this guide if your professor has already given you a list of topics to consider for your assignment . You can skip to our guide on how to write a research paper .

If they have left it up to you to choose a topic to investigate, which they must approve before you start working on your research study, we suggest that you read the process shared in this post.

Choosing a topic after finding your research problem is important because:

- The topic guides your research and gives you a mean to not only arrive at other interesting topics but also direct you to discover new knowledge

- The topic you choose will govern what you say and ensures you keep a logical flow of information.

Picking a topic for a research paper can be challenging and sometimes intimidating, but it’s not impossible. In the following section, we show you how to choose the best research topic that your instructor can approve after the first review.

How to Select a Research Topic

Below are four steps to follow to find the most suitable topic for your research paper assignment:

Step 1: Consider a Topic that Interests You

If your professor has asked you to choose a topic for your research paper, it means you can choose just about any subject to focus on in your area of study. A significant first step to take is to consider topics that interest you.

An interesting topic should meet two very important conditions.

First, it should be concise. The topic you choose should not be too broad or two narrow. Rather, it should be something focused on a specific issue. Second, the topic should allow you to find enough sources to cite in the research stage of your assignment.

The best way to determine if the research topic is interesting is to do some free writing for about 10 minutes. As you free write, think about the number of questions that people ask about the topic and try to consider why they’re important. These questions are important because they will make the research stage easier for you.

You’ll probably have a long list of interesting topics to consider for your research assignment. That’s a good first step because it means your options aren’t limited. However, you need to narrow down to only one topic for the assignment, so it’s time to start brainstorming.

Step 2: Brainstorm Your Topics

You aren’t doing research at this stage yet. You are only trying to make considerations to determine which topic will suit your research assignment.

The brainstorming stage isn’t difficult at all. It should take only a couple of hours or a few days depending on how you approach.

We recommend talking to your professor, classmates, and friends about the topics that you’ve picked and ask for their opinion. Expect mixed opinions from this audience and then consider the topics that make the most sense. Note what topics picked their interest the most and put them on top of the list.

You’ll end up removing some topics from your initial list after brainstorming, and that’s completely fine. The goal here is to end up with a topic that interests you as well as your readers.

Step 3: Define Your Topics

Check once again to make sure that your topic is a subject that you can easily define. You want to make sure the topic isn’t too broad or too narrow.

Often, a broad topic presents overwhelming amount of information, which makes it difficult to write a comprehensive research paper. A narrow topic, on the other hand, means you’ll find very little information, and therefore it can be difficult to do your assignment.

The length of the research paper, as stated in the assignment brief, should guide your topic selection.

Narrow down your list to topics that are:

- Broad enough to allows you to find enough scholarly articles and journals for reference

- Narrow enough to fit within the expected word count and the scope of the research

Topics that meet these two conditions should be easy to work on as they easily fit within the constraints of the research assignment.

Step 4: Read Background Information of Selected Topics

You probably have two or three topics by the time you get to this step. Now it’s time to read the background information on the topics to decide which topic to work on.

This step is important because it gives you a clear overview of the topic, enabling you to see how it relates to broader, narrower, and related concepts. Preliminary research also helps you to find keywords commonly used to describe the topic, which may be useful in further research.

It’s important to note how easy or difficult it is to find information on the topic.

Look at different sources of information to be sure you can find enough references for the topic. Such periodic indexes scan journals, newspaper articles, and magazines to find the information you’re looking for. You can even use web search engines. Google and Bing are currently that best options to consider because they make it easy for searchers to find relevant information on scholarly topics.

If you’re having a hard time to find references for a topic that you’ve so far considered for your research paper, skip it and go to the next one. Doing so will go a long way to ensure you have the right topic to work on from start to finish.

Get Research Paper Writing Help

If you’ve found your research topic but you feel so stuck that you can’t proceed with the assignment without some assistance, we are here to help. With our research paper writing service , we can help you handle the assignment within the shortest time possible.

We will research your topic, develop a research question, outline the project, and help you with writing. We also get you involved in the process, allowing you to track the progress of your order until the delivery stage.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

Research Process Guide

- Step 1 - Identifying and Developing a Topic

- Step 2 - Narrowing Your Topic

- Step 3 - Developing Research Questions

- Step 4 - Conducting a Literature Review

- Step 5 - Choosing a Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

- Step 6 - Determining Research Methodology

- Step 6a - Determining Research Methodology - Quantitative Research Methods

- Step 6b - Determining Research Methodology - Qualitative Design

- Step 7 - Considering Ethical Issues in Research with Human Subjects - Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Step 8 - Collecting Data

- Step 9 - Analyzing Data

- Step 10 - Interpreting Results

- Step 11 - Writing Up Results

Step 1: Identifying and Developing a Topic

Whatever your field or discipline, the best advice to give on identifying a research topic is to choose something that you find really interesting. You will be spending an enormous amount of time with your topic, you need to be invested. Over the course of your research design, proposal and actually conducting your study, you may feel like you are really tired of your topic, however, your interest and investment in the topic will help you persist through dissertation defense. Identifying a research topic can be challenging. Most of the research that has been completed on the process of conducting research fails to examine the preliminary stages of the interactive and self-reflective process of identifying a research topic (Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). You may choose a topic at the beginning of the process, and through exploring the research that has already been done, one’s own interests that are narrowed or expanded in scope, the topic will change over time (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019). Where do I begin? According to the research, there are generally two paths to exploring your research topic, creative path and the rational path (Saunders et al., 2019). The rational path takes a linear path and deals with questions we need to ask ourselves like: what are some timely topics in my field in the media right now?; what strengths do I bring to the research?; what are the gaps in the research about the area of research interest? (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020).The creative path is less linear in that it may include keeping a notebook of ideas based on discussion in coursework or with your peers in the field. Whichever path you take, you will inevitably have to narrow your more generalized ideas down. A great way to do that is to continue reading the literature about and around your topic looking for gaps that could be explored. Also, try engaging in meaningful discussions with experts in your field to get their take on your research ideas (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). It is important to remember that a research topic should be (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020):

- Interesting to you.

- Realistic in that it can be completed in an appropriate amount of time.

- Relevant to your program or field of study.

- Not widely researched.

Dwarkadas, S., & Lin, M. C. (2019, August 04). Finding a research topic. Computing Research Association for Women, Portland State University. https://cra.org/cra-wp/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/FindingResearchTopic/2019.pdf

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

Wintersberger, D., & Saunders, M. (2020). Formulating and clarifying the research topic: Insights and a guide for the production management research community. Production, 30 . https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.20200059

- Last Updated: Jun 29, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.kean.edu/ResearchProcessGuide

- Spartanburg Community College Library

- SCC Research Guides

- Choosing a Research Topic

- What Makes a Good Research Topic?

Before diving into how to choose a research topic, it is important to think about what are some elements of a good research topic. Of course, this will depend specifically on your research project, but a good research topic will always:

- Relate to the assignment itself. Even when you have a choice for your research topic, you still want to make sure your chosen topic lines up with your class assignment sheet.

- A topic that is too broad will give you too many sources, and it will be hard to focus your research.

- A topic that is too narrow will not give you enough sources, if you can find any sources at all.

- Is debatable. This is important if you are researching a topic that you will have to argue a position for. Good topics have more than one side to the issue and cannot be resolved with a simple yes or no.

- Should be interesting to you! It's more fun to do research on a topic that you are interested in as opposed to one you are not interested in.

Remember, it is common and normal if your research topic changes as you start brainstorming and doing some background research on your topic.

Start with a General Idea

As an example, let's say you were writing a paper about issues relating to college students

- << Previous: Choosing a Research Topic

- Next: 1. Concept Mapping >>

- 1. Concept Mapping

- 2. Background Research

- 3. Narrow Your Topic / Thesis Statements

Questions? Ask a Librarian

- Last Updated: Jul 19, 2024 1:21 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sccsc.edu/chooseatopic

Giles Campus | 864.592.4764 | Toll Free 866.542.2779 | Contact Us

Copyright © 2024 Spartanburg Community College. All rights reserved.

Info for Library Staff | Guide Search

Return to SCC Website

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Choosing a Topic

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The first step of any research paper is for the student to understand the assignment. If this is not done, the student will often travel down many dead-end roads, wasting a great deal of time along the way. Do not hesitate to approach the instructor with questions if there is any confusion. A clear understanding of the assignment will allow you to focus on other aspects of the process, such as choosing a topic and identifying your audience.

A student will often encounter one of two situations when it comes to choosing a topic for a research paper. The first situation occurs when the instructor provides a list of topics from which the student may choose. These topics have been deemed worthy by the instructor; therefore, the student should be confident in the topic he chooses from the list. Many first-time researchers appreciate such an arrangement by the instructor because it eliminates the stress of having to decide upon a topic on their own.

However, the student may also find the topics that have been provided to be limiting; moreover, it is not uncommon for the student to have a topic in mind that does not fit with any of those provided. If this is the case, it is always beneficial to approach the instructor with one's ideas. Be respectful, and ask the instructor if the topic you have in mind would be a possible research option for the assignment. Remember, as a first-time researcher, your knowledge of the process is quite limited; the instructor is experienced, and may have very precise reasons for choosing the topics she has offered to the class. Trust that she has the best interests of the class in mind. If she likes the topic, great! If not, do not take it personally and choose the topic from the list that seems most interesting to you.

The second situation occurs when the instructor simply hands out an assignment sheet that covers the logistics of the research paper, but leaves the choice of topic up to the student. Typically, assignments in which students are given the opportunity to choose the topic require the topic to be relevant to some aspect of the course; so, keep this in mind as you begin a course in which you know there will be a research paper near the end. That way, you can be on the lookout for a topic that may interest you. Do not be anxious on account of a perceived lack of authority or knowledge about the topic chosen. Instead, realize that it takes practice to become an experienced researcher in any field.

For a discussion of Evaluating Sources, see Evaluating Sources of Information .

Methods for choosing a topic

Thinking early leads to starting early. If the student begins thinking about possible topics when the assignment is given, she has already begun the arduous, yet rewarding, task of planning and organization. Once she has made the assignment a priority in her mind, she may begin to have ideas throughout the day. Brainstorming is often a successful way for students to get some of these ideas down on paper. Seeing one's ideas in writing is often an impetus for the writing process. Though brainstorming is particularly effective when a topic has been chosen, it can also benefit the student who is unable to narrow a topic. It consists of a timed writing session during which the student jots down—often in list or bulleted form—any ideas that come to his mind. At the end of the timed period, the student will peruse his list for patterns of consistency. If it appears that something seems to be standing out in his mind more than others, it may be wise to pursue this as a topic possibility.

It is important for the student to keep in mind that an initial topic that you come up with may not be the exact topic about which you end up writing. Research topics are often fluid, and dictated more by the student's ongoing research than by the original chosen topic. Such fluidity is common in research, and should be embraced as one of its many characteristics.

The Purdue OWL also offers a number of other resources on choosing and developing a topic:

- Understanding Writing Assignments

- Starting the Writing Process

- Invention Slide Presentation

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

113 Great Research Paper Topics

General Education

One of the hardest parts of writing a research paper can be just finding a good topic to write about. Fortunately we've done the hard work for you and have compiled a list of 113 interesting research paper topics. They've been organized into ten categories and cover a wide range of subjects so you can easily find the best topic for you.

In addition to the list of good research topics, we've included advice on what makes a good research paper topic and how you can use your topic to start writing a great paper.

What Makes a Good Research Paper Topic?

Not all research paper topics are created equal, and you want to make sure you choose a great topic before you start writing. Below are the three most important factors to consider to make sure you choose the best research paper topics.

#1: It's Something You're Interested In

A paper is always easier to write if you're interested in the topic, and you'll be more motivated to do in-depth research and write a paper that really covers the entire subject. Even if a certain research paper topic is getting a lot of buzz right now or other people seem interested in writing about it, don't feel tempted to make it your topic unless you genuinely have some sort of interest in it as well.

#2: There's Enough Information to Write a Paper

Even if you come up with the absolute best research paper topic and you're so excited to write about it, you won't be able to produce a good paper if there isn't enough research about the topic. This can happen for very specific or specialized topics, as well as topics that are too new to have enough research done on them at the moment. Easy research paper topics will always be topics with enough information to write a full-length paper.

Trying to write a research paper on a topic that doesn't have much research on it is incredibly hard, so before you decide on a topic, do a bit of preliminary searching and make sure you'll have all the information you need to write your paper.

#3: It Fits Your Teacher's Guidelines

Don't get so carried away looking at lists of research paper topics that you forget any requirements or restrictions your teacher may have put on research topic ideas. If you're writing a research paper on a health-related topic, deciding to write about the impact of rap on the music scene probably won't be allowed, but there may be some sort of leeway. For example, if you're really interested in current events but your teacher wants you to write a research paper on a history topic, you may be able to choose a topic that fits both categories, like exploring the relationship between the US and North Korea. No matter what, always get your research paper topic approved by your teacher first before you begin writing.

113 Good Research Paper Topics

Below are 113 good research topics to help you get you started on your paper. We've organized them into ten categories to make it easier to find the type of research paper topics you're looking for.

Arts/Culture

- Discuss the main differences in art from the Italian Renaissance and the Northern Renaissance .

- Analyze the impact a famous artist had on the world.

- How is sexism portrayed in different types of media (music, film, video games, etc.)? Has the amount/type of sexism changed over the years?

- How has the music of slaves brought over from Africa shaped modern American music?

- How has rap music evolved in the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of minorities in the media changed?

Current Events

- What have been the impacts of China's one child policy?

- How have the goals of feminists changed over the decades?

- How has the Trump presidency changed international relations?

- Analyze the history of the relationship between the United States and North Korea.

- What factors contributed to the current decline in the rate of unemployment?

- What have been the impacts of states which have increased their minimum wage?

- How do US immigration laws compare to immigration laws of other countries?

- How have the US's immigration laws changed in the past few years/decades?

- How has the Black Lives Matter movement affected discussions and view about racism in the US?

- What impact has the Affordable Care Act had on healthcare in the US?

- What factors contributed to the UK deciding to leave the EU (Brexit)?

- What factors contributed to China becoming an economic power?

- Discuss the history of Bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies (some of which tokenize the S&P 500 Index on the blockchain) .

- Do students in schools that eliminate grades do better in college and their careers?

- Do students from wealthier backgrounds score higher on standardized tests?

- Do students who receive free meals at school get higher grades compared to when they weren't receiving a free meal?

- Do students who attend charter schools score higher on standardized tests than students in public schools?

- Do students learn better in same-sex classrooms?

- How does giving each student access to an iPad or laptop affect their studies?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Montessori Method ?

- Do children who attend preschool do better in school later on?

- What was the impact of the No Child Left Behind act?

- How does the US education system compare to education systems in other countries?

- What impact does mandatory physical education classes have on students' health?

- Which methods are most effective at reducing bullying in schools?

- Do homeschoolers who attend college do as well as students who attended traditional schools?

- Does offering tenure increase or decrease quality of teaching?

- How does college debt affect future life choices of students?

- Should graduate students be able to form unions?

- What are different ways to lower gun-related deaths in the US?

- How and why have divorce rates changed over time?

- Is affirmative action still necessary in education and/or the workplace?

- Should physician-assisted suicide be legal?

- How has stem cell research impacted the medical field?

- How can human trafficking be reduced in the United States/world?

- Should people be able to donate organs in exchange for money?

- Which types of juvenile punishment have proven most effective at preventing future crimes?

- Has the increase in US airport security made passengers safer?

- Analyze the immigration policies of certain countries and how they are similar and different from one another.

- Several states have legalized recreational marijuana. What positive and negative impacts have they experienced as a result?

- Do tariffs increase the number of domestic jobs?

- Which prison reforms have proven most effective?

- Should governments be able to censor certain information on the internet?

- Which methods/programs have been most effective at reducing teen pregnancy?

- What are the benefits and drawbacks of the Keto diet?

- How effective are different exercise regimes for losing weight and maintaining weight loss?

- How do the healthcare plans of various countries differ from each other?

- What are the most effective ways to treat depression ?

- What are the pros and cons of genetically modified foods?

- Which methods are most effective for improving memory?

- What can be done to lower healthcare costs in the US?

- What factors contributed to the current opioid crisis?

- Analyze the history and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic .

- Are low-carbohydrate or low-fat diets more effective for weight loss?

- How much exercise should the average adult be getting each week?

- Which methods are most effective to get parents to vaccinate their children?

- What are the pros and cons of clean needle programs?

- How does stress affect the body?

- Discuss the history of the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians.

- What were the causes and effects of the Salem Witch Trials?

- Who was responsible for the Iran-Contra situation?

- How has New Orleans and the government's response to natural disasters changed since Hurricane Katrina?

- What events led to the fall of the Roman Empire?

- What were the impacts of British rule in India ?

- Was the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary?

- What were the successes and failures of the women's suffrage movement in the United States?

- What were the causes of the Civil War?

- How did Abraham Lincoln's assassination impact the country and reconstruction after the Civil War?

- Which factors contributed to the colonies winning the American Revolution?

- What caused Hitler's rise to power?

- Discuss how a specific invention impacted history.

- What led to Cleopatra's fall as ruler of Egypt?

- How has Japan changed and evolved over the centuries?

- What were the causes of the Rwandan genocide ?

- Why did Martin Luther decide to split with the Catholic Church?

- Analyze the history and impact of a well-known cult (Jonestown, Manson family, etc.)

- How did the sexual abuse scandal impact how people view the Catholic Church?

- How has the Catholic church's power changed over the past decades/centuries?

- What are the causes behind the rise in atheism/ agnosticism in the United States?

- What were the influences in Siddhartha's life resulted in him becoming the Buddha?

- How has media portrayal of Islam/Muslims changed since September 11th?

Science/Environment

- How has the earth's climate changed in the past few decades?

- How has the use and elimination of DDT affected bird populations in the US?

- Analyze how the number and severity of natural disasters have increased in the past few decades.

- Analyze deforestation rates in a certain area or globally over a period of time.

- How have past oil spills changed regulations and cleanup methods?

- How has the Flint water crisis changed water regulation safety?

- What are the pros and cons of fracking?

- What impact has the Paris Climate Agreement had so far?

- What have NASA's biggest successes and failures been?

- How can we improve access to clean water around the world?

- Does ecotourism actually have a positive impact on the environment?

- Should the US rely on nuclear energy more?

- What can be done to save amphibian species currently at risk of extinction?

- What impact has climate change had on coral reefs?

- How are black holes created?

- Are teens who spend more time on social media more likely to suffer anxiety and/or depression?

- How will the loss of net neutrality affect internet users?

- Analyze the history and progress of self-driving vehicles.

- How has the use of drones changed surveillance and warfare methods?

- Has social media made people more or less connected?

- What progress has currently been made with artificial intelligence ?

- Do smartphones increase or decrease workplace productivity?

- What are the most effective ways to use technology in the classroom?

- How is Google search affecting our intelligence?

- When is the best age for a child to begin owning a smartphone?

- Has frequent texting reduced teen literacy rates?

How to Write a Great Research Paper

Even great research paper topics won't give you a great research paper if you don't hone your topic before and during the writing process. Follow these three tips to turn good research paper topics into great papers.

#1: Figure Out Your Thesis Early

Before you start writing a single word of your paper, you first need to know what your thesis will be. Your thesis is a statement that explains what you intend to prove/show in your paper. Every sentence in your research paper will relate back to your thesis, so you don't want to start writing without it!

As some examples, if you're writing a research paper on if students learn better in same-sex classrooms, your thesis might be "Research has shown that elementary-age students in same-sex classrooms score higher on standardized tests and report feeling more comfortable in the classroom."

If you're writing a paper on the causes of the Civil War, your thesis might be "While the dispute between the North and South over slavery is the most well-known cause of the Civil War, other key causes include differences in the economies of the North and South, states' rights, and territorial expansion."

#2: Back Every Statement Up With Research

Remember, this is a research paper you're writing, so you'll need to use lots of research to make your points. Every statement you give must be backed up with research, properly cited the way your teacher requested. You're allowed to include opinions of your own, but they must also be supported by the research you give.

#3: Do Your Research Before You Begin Writing

You don't want to start writing your research paper and then learn that there isn't enough research to back up the points you're making, or, even worse, that the research contradicts the points you're trying to make!

Get most of your research on your good research topics done before you begin writing. Then use the research you've collected to create a rough outline of what your paper will cover and the key points you're going to make. This will help keep your paper clear and organized, and it'll ensure you have enough research to produce a strong paper.

What's Next?

Are you also learning about dynamic equilibrium in your science class? We break this sometimes tricky concept down so it's easy to understand in our complete guide to dynamic equilibrium .

Thinking about becoming a nurse practitioner? Nurse practitioners have one of the fastest growing careers in the country, and we have all the information you need to know about what to expect from nurse practitioner school .

Want to know the fastest and easiest ways to convert between Fahrenheit and Celsius? We've got you covered! Check out our guide to the best ways to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit (or vice versa).

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- How to Choose a PhD Research Topic

- Finding a PhD

Introduction

Whilst there are plenty of resources available to help prospective PhD students find doctoral programmes, deciding on a research topic is a process students often find more difficult.

Some advertised PhD programmes have predefined titles, so the exact topic is decided already. Generally, these programmes exist mainly in STEM, though other fields also have them. Funded projects are more likely to have defined titles, and structured aims and objectives.

Self funded projects, and those in fields such as arts and humanities, are less likely to have defined titles. The flexibility of topic selection means more scope exists for applicants to propose research ideas and suit the topic of research to their interests.

A middle ground also exists where Universities advertise funded PhD programmes in subjects without a defined scope, for example: “PhD Studentship in Biomechanics”. The applicant can then liaise with the project supervisor to choose a particular title such as “A study of fatigue and impact resistance of biodegradable knee implants”.

If a predefined programme is not right for you, then you need to propose your own research topic. There are several factors to consider when choosing a good research topic, which will be outlined in this article.

How to Choose a Research Topic

Our first piece of advice is to PhD candidates is to stop thinking about ‘finding’ a research topic, as it is unlikely that you will. Instead, think about developing a research topic (from research and conversations with advisors).

Consider several ideas and critically appraise them:

- You must be able to explain to others why your chosen topic is worth studying.

- You must be genuinely interested in the subject area.

- You must be competent and equipped to answer the research question.

- You must set achievable and measurable aims and objectives.

- You need to be able to achieve your objectives within a given timeframe.

- Your research question must be original and contribute to the field of study.

We have outlined the key considerations you should use when developing possible topics. We explore these below:

Focus on your interests and career aspirations