- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Evaluation Research: Definition, Methods and Examples

Content Index

- What is evaluation research

- Why do evaluation research

Quantitative methods

Qualitative methods.

- Process evaluation research question examples

- Outcome evaluation research question examples

What is evaluation research?

Evaluation research, also known as program evaluation, refers to research purpose instead of a specific method. Evaluation research is the systematic assessment of the worth or merit of time, money, effort and resources spent in order to achieve a goal.

Evaluation research is closely related to but slightly different from more conventional social research . It uses many of the same methods used in traditional social research, but because it takes place within an organizational context, it requires team skills, interpersonal skills, management skills, political smartness, and other research skills that social research does not need much. Evaluation research also requires one to keep in mind the interests of the stakeholders.

Evaluation research is a type of applied research, and so it is intended to have some real-world effect. Many methods like surveys and experiments can be used to do evaluation research. The process of evaluation research consisting of data analysis and reporting is a rigorous, systematic process that involves collecting data about organizations, processes, projects, services, and/or resources. Evaluation research enhances knowledge and decision-making, and leads to practical applications.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Why do evaluation research?

The common goal of most evaluations is to extract meaningful information from the audience and provide valuable insights to evaluators such as sponsors, donors, client-groups, administrators, staff, and other relevant constituencies. Most often, feedback is perceived value as useful if it helps in decision-making. However, evaluation research does not always create an impact that can be applied anywhere else, sometimes they fail to influence short-term decisions. It is also equally true that initially, it might seem to not have any influence, but can have a delayed impact when the situation is more favorable. In spite of this, there is a general agreement that the major goal of evaluation research should be to improve decision-making through the systematic utilization of measurable feedback.

Below are some of the benefits of evaluation research

- Gain insights about a project or program and its operations

Evaluation Research lets you understand what works and what doesn’t, where we were, where we are and where we are headed towards. You can find out the areas of improvement and identify strengths. So, it will help you to figure out what do you need to focus more on and if there are any threats to your business. You can also find out if there are currently hidden sectors in the market that are yet untapped.

- Improve practice

It is essential to gauge your past performance and understand what went wrong in order to deliver better services to your customers. Unless it is a two-way communication, there is no way to improve on what you have to offer. Evaluation research gives an opportunity to your employees and customers to express how they feel and if there’s anything they would like to change. It also lets you modify or adopt a practice such that it increases the chances of success.

- Assess the effects

After evaluating the efforts, you can see how well you are meeting objectives and targets. Evaluations let you measure if the intended benefits are really reaching the targeted audience and if yes, then how effectively.

- Build capacity

Evaluations help you to analyze the demand pattern and predict if you will need more funds, upgrade skills and improve the efficiency of operations. It lets you find the gaps in the production to delivery chain and possible ways to fill them.

Methods of evaluation research

All market research methods involve collecting and analyzing the data, making decisions about the validity of the information and deriving relevant inferences from it. Evaluation research comprises of planning, conducting and analyzing the results which include the use of data collection techniques and applying statistical methods.

Some of the evaluation methods which are quite popular are input measurement, output or performance measurement, impact or outcomes assessment, quality assessment, process evaluation, benchmarking, standards, cost analysis, organizational effectiveness, program evaluation methods, and LIS-centered methods. There are also a few types of evaluations that do not always result in a meaningful assessment such as descriptive studies, formative evaluations, and implementation analysis. Evaluation research is more about information-processing and feedback functions of evaluation.

These methods can be broadly classified as quantitative and qualitative methods.

The outcome of the quantitative research methods is an answer to the questions below and is used to measure anything tangible.

- Who was involved?

- What were the outcomes?

- What was the price?

The best way to collect quantitative data is through surveys , questionnaires , and polls . You can also create pre-tests and post-tests, review existing documents and databases or gather clinical data.

Surveys are used to gather opinions, feedback or ideas of your employees or customers and consist of various question types . They can be conducted by a person face-to-face or by telephone, by mail, or online. Online surveys do not require the intervention of any human and are far more efficient and practical. You can see the survey results on dashboard of research tools and dig deeper using filter criteria based on various factors such as age, gender, location, etc. You can also keep survey logic such as branching, quotas, chain survey, looping, etc in the survey questions and reduce the time to both create and respond to the donor survey . You can also generate a number of reports that involve statistical formulae and present data that can be readily absorbed in the meetings. To learn more about how research tool works and whether it is suitable for you, sign up for a free account now.

Create a free account!

Quantitative data measure the depth and breadth of an initiative, for instance, the number of people who participated in the non-profit event, the number of people who enrolled for a new course at the university. Quantitative data collected before and after a program can show its results and impact.

The accuracy of quantitative data to be used for evaluation research depends on how well the sample represents the population, the ease of analysis, and their consistency. Quantitative methods can fail if the questions are not framed correctly and not distributed to the right audience. Also, quantitative data do not provide an understanding of the context and may not be apt for complex issues.

Learn more: Quantitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Qualitative research methods are used where quantitative methods cannot solve the research problem , i.e. they are used to measure intangible values. They answer questions such as

- What is the value added?

- How satisfied are you with our service?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your friends?

- What will improve your experience?

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

Qualitative data is collected through observation, interviews, case studies, and focus groups. The steps for creating a qualitative study involve examining, comparing and contrasting, and understanding patterns. Analysts conclude after identification of themes, clustering similar data, and finally reducing to points that make sense.

Observations may help explain behaviors as well as the social context that is generally not discovered by quantitative methods. Observations of behavior and body language can be done by watching a participant, recording audio or video. Structured interviews can be conducted with people alone or in a group under controlled conditions, or they may be asked open-ended qualitative research questions . Qualitative research methods are also used to understand a person’s perceptions and motivations.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

The strength of this method is that group discussion can provide ideas and stimulate memories with topics cascading as discussion occurs. The accuracy of qualitative data depends on how well contextual data explains complex issues and complements quantitative data. It helps get the answer of “why” and “how”, after getting an answer to “what”. The limitations of qualitative data for evaluation research are that they are subjective, time-consuming, costly and difficult to analyze and interpret.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research: The Complete Guide

Survey software can be used for both the evaluation research methods. You can use above sample questions for evaluation research and send a survey in minutes using research software. Using a tool for research simplifies the process right from creating a survey, importing contacts, distributing the survey and generating reports that aid in research.

Examples of evaluation research

Evaluation research questions lay the foundation of a successful evaluation. They define the topics that will be evaluated. Keeping evaluation questions ready not only saves time and money, but also makes it easier to decide what data to collect, how to analyze it, and how to report it.

Evaluation research questions must be developed and agreed on in the planning stage, however, ready-made research templates can also be used.

Process evaluation research question examples:

- How often do you use our product in a day?

- Were approvals taken from all stakeholders?

- Can you report the issue from the system?

- Can you submit the feedback from the system?

- Was each task done as per the standard operating procedure?

- What were the barriers to the implementation of each task?

- Were any improvement areas discovered?

Outcome evaluation research question examples:

- How satisfied are you with our product?

- Did the program produce intended outcomes?

- What were the unintended outcomes?

- Has the program increased the knowledge of participants?

- Were the participants of the program employable before the course started?

- Do participants of the program have the skills to find a job after the course ended?

- Is the knowledge of participants better compared to those who did not participate in the program?

MORE LIKE THIS

Customer Experience Lessons from 13,000 Feet — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Aug 20, 2024

Insight: Definition & meaning, types and examples

Aug 19, 2024

Employee Loyalty: Strategies for Long-Term Business Success

Jotform vs SurveyMonkey: Which Is Best in 2024

Aug 15, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Privacy Policy

Home » Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and Methods

Table of Contents

Evaluating Research

Definition:

Evaluating Research refers to the process of assessing the quality, credibility, and relevance of a research study or project. This involves examining the methods, data, and results of the research in order to determine its validity, reliability, and usefulness. Evaluating research can be done by both experts and non-experts in the field, and involves critical thinking, analysis, and interpretation of the research findings.

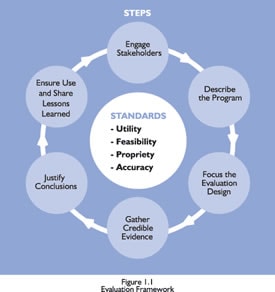

Research Evaluating Process

The process of evaluating research typically involves the following steps:

Identify the Research Question

The first step in evaluating research is to identify the research question or problem that the study is addressing. This will help you to determine whether the study is relevant to your needs.

Assess the Study Design

The study design refers to the methodology used to conduct the research. You should assess whether the study design is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce reliable and valid results.

Evaluate the Sample

The sample refers to the group of participants or subjects who are included in the study. You should evaluate whether the sample size is adequate and whether the participants are representative of the population under study.

Review the Data Collection Methods

You should review the data collection methods used in the study to ensure that they are valid and reliable. This includes assessing the measures used to collect data and the procedures used to collect data.

Examine the Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis refers to the methods used to analyze the data. You should examine whether the statistical analysis is appropriate for the research question and whether it is likely to produce valid and reliable results.

Assess the Conclusions

You should evaluate whether the data support the conclusions drawn from the study and whether they are relevant to the research question.

Consider the Limitations

Finally, you should consider the limitations of the study, including any potential biases or confounding factors that may have influenced the results.

Evaluating Research Methods

Evaluating Research Methods are as follows:

- Peer review: Peer review is a process where experts in the field review a study before it is published. This helps ensure that the study is accurate, valid, and relevant to the field.

- Critical appraisal : Critical appraisal involves systematically evaluating a study based on specific criteria. This helps assess the quality of the study and the reliability of the findings.

- Replication : Replication involves repeating a study to test the validity and reliability of the findings. This can help identify any errors or biases in the original study.

- Meta-analysis : Meta-analysis is a statistical method that combines the results of multiple studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic. This can help identify patterns or inconsistencies across studies.

- Consultation with experts : Consulting with experts in the field can provide valuable insights into the quality and relevance of a study. Experts can also help identify potential limitations or biases in the study.

- Review of funding sources: Examining the funding sources of a study can help identify any potential conflicts of interest or biases that may have influenced the study design or interpretation of results.

Example of Evaluating Research

Example of Evaluating Research sample for students:

Title of the Study: The Effects of Social Media Use on Mental Health among College Students

Sample Size: 500 college students

Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling

- Sample Size: The sample size of 500 college students is a moderate sample size, which could be considered representative of the college student population. However, it would be more representative if the sample size was larger, or if a random sampling technique was used.

- Sampling Technique : Convenience sampling is a non-probability sampling technique, which means that the sample may not be representative of the population. This technique may introduce bias into the study since the participants are self-selected and may not be representative of the entire college student population. Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to other populations.

- Participant Characteristics: The study does not provide any information about the demographic characteristics of the participants, such as age, gender, race, or socioeconomic status. This information is important because social media use and mental health may vary among different demographic groups.

- Data Collection Method: The study used a self-administered survey to collect data. Self-administered surveys may be subject to response bias and may not accurately reflect participants’ actual behaviors and experiences.

- Data Analysis: The study used descriptive statistics and regression analysis to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics provide a summary of the data, while regression analysis is used to examine the relationship between two or more variables. However, the study did not provide information about the statistical significance of the results or the effect sizes.

Overall, while the study provides some insights into the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students, the use of a convenience sampling technique and the lack of information about participant characteristics limit the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the use of self-administered surveys may introduce bias into the study, and the lack of information about the statistical significance of the results limits the interpretation of the findings.

Note*: Above mentioned example is just a sample for students. Do not copy and paste directly into your assignment. Kindly do your own research for academic purposes.

Applications of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the applications of evaluating research:

- Identifying reliable sources : By evaluating research, researchers, students, and other professionals can identify the most reliable sources of information to use in their work. They can determine the quality of research studies, including the methodology, sample size, data analysis, and conclusions.

- Validating findings: Evaluating research can help to validate findings from previous studies. By examining the methodology and results of a study, researchers can determine if the findings are reliable and if they can be used to inform future research.

- Identifying knowledge gaps: Evaluating research can also help to identify gaps in current knowledge. By examining the existing literature on a topic, researchers can determine areas where more research is needed, and they can design studies to address these gaps.

- Improving research quality : Evaluating research can help to improve the quality of future research. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies, researchers can design better studies and avoid common pitfalls.

- Informing policy and decision-making : Evaluating research is crucial in informing policy and decision-making in many fields. By examining the evidence base for a particular issue, policymakers can make informed decisions that are supported by the best available evidence.

- Enhancing education : Evaluating research is essential in enhancing education. Educators can use research findings to improve teaching methods, curriculum development, and student outcomes.

Purpose of Evaluating Research

Here are some of the key purposes of evaluating research:

- Determine the reliability and validity of research findings : By evaluating research, researchers can determine the quality of the study design, data collection, and analysis. They can determine whether the findings are reliable, valid, and generalizable to other populations.

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies: Evaluating research helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of research studies, including potential biases, confounding factors, and limitations. This information can help researchers to design better studies in the future.

- Inform evidence-based decision-making: Evaluating research is crucial in informing evidence-based decision-making in many fields, including healthcare, education, and public policy. Policymakers, educators, and clinicians rely on research evidence to make informed decisions.

- Identify research gaps : By evaluating research, researchers can identify gaps in the existing literature and design studies to address these gaps. This process can help to advance knowledge and improve the quality of research in a particular field.

- Ensure research ethics and integrity : Evaluating research helps to ensure that research studies are conducted ethically and with integrity. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines to protect the welfare and rights of study participants and to maintain the trust of the public.

Characteristics Evaluating Research

Characteristics Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Research question/hypothesis: A good research question or hypothesis should be clear, concise, and well-defined. It should address a significant problem or issue in the field and be grounded in relevant theory or prior research.

- Study design: The research design should be appropriate for answering the research question and be clearly described in the study. The study design should also minimize bias and confounding variables.

- Sampling : The sample should be representative of the population of interest and the sampling method should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Data collection : The data collection methods should be reliable and valid, and the data should be accurately recorded and analyzed.

- Results : The results should be presented clearly and accurately, and the statistical analysis should be appropriate for the research question and study design.

- Interpretation of results : The interpretation of the results should be based on the data and not influenced by personal biases or preconceptions.

- Generalizability: The study findings should be generalizable to the population of interest and relevant to other settings or contexts.

- Contribution to the field : The study should make a significant contribution to the field and advance our understanding of the research question or issue.

Advantages of Evaluating Research

Evaluating research has several advantages, including:

- Ensuring accuracy and validity : By evaluating research, we can ensure that the research is accurate, valid, and reliable. This ensures that the findings are trustworthy and can be used to inform decision-making.

- Identifying gaps in knowledge : Evaluating research can help identify gaps in knowledge and areas where further research is needed. This can guide future research and help build a stronger evidence base.

- Promoting critical thinking: Evaluating research requires critical thinking skills, which can be applied in other areas of life. By evaluating research, individuals can develop their critical thinking skills and become more discerning consumers of information.

- Improving the quality of research : Evaluating research can help improve the quality of research by identifying areas where improvements can be made. This can lead to more rigorous research methods and better-quality research.

- Informing decision-making: By evaluating research, we can make informed decisions based on the evidence. This is particularly important in fields such as medicine and public health, where decisions can have significant consequences.

- Advancing the field : Evaluating research can help advance the field by identifying new research questions and areas of inquiry. This can lead to the development of new theories and the refinement of existing ones.

Limitations of Evaluating Research

Limitations of Evaluating Research are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Evaluating research can be time-consuming, particularly if the study is complex or requires specialized knowledge. This can be a barrier for individuals who are not experts in the field or who have limited time.

- Subjectivity : Evaluating research can be subjective, as different individuals may have different interpretations of the same study. This can lead to inconsistencies in the evaluation process and make it difficult to compare studies.

- Limited generalizability: The findings of a study may not be generalizable to other populations or contexts. This limits the usefulness of the study and may make it difficult to apply the findings to other settings.

- Publication bias: Research that does not find significant results may be less likely to be published, which can create a bias in the published literature. This can limit the amount of information available for evaluation.

- Lack of transparency: Some studies may not provide enough detail about their methods or results, making it difficult to evaluate their quality or validity.

- Funding bias : Research funded by particular organizations or industries may be biased towards the interests of the funder. This can influence the study design, methods, and interpretation of results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Tables in Research Paper – Types, Creating Guide...

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing...

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

- Evaluation Research Design: Examples, Methods & Types

As you engage in tasks, you will need to take intermittent breaks to determine how much progress has been made and if any changes need to be effected along the way. This is very similar to what organizations do when they carry out evaluation research.

The evaluation research methodology has become one of the most important approaches for organizations as they strive to create products, services, and processes that speak to the needs of target users. In this article, we will show you how your organization can conduct successful evaluation research using Formplus .

What is Evaluation Research?

Also known as program evaluation, evaluation research is a common research design that entails carrying out a structured assessment of the value of resources committed to a project or specific goal. It often adopts social research methods to gather and analyze useful information about organizational processes and products.

As a type of applied research , evaluation research typically associated with real-life scenarios within organizational contexts. This means that the researcher will need to leverage common workplace skills including interpersonal skills and team play to arrive at objective research findings that will be useful to stakeholders.

Characteristics of Evaluation Research

- Research Environment: Evaluation research is conducted in the real world; that is, within the context of an organization.

- Research Focus: Evaluation research is primarily concerned with measuring the outcomes of a process rather than the process itself.

- Research Outcome: Evaluation research is employed for strategic decision making in organizations.

- Research Goal: The goal of program evaluation is to determine whether a process has yielded the desired result(s).

- This type of research protects the interests of stakeholders in the organization.

- It often represents a middle-ground between pure and applied research.

- Evaluation research is both detailed and continuous. It pays attention to performative processes rather than descriptions.

- Research Process: This research design utilizes qualitative and quantitative research methods to gather relevant data about a product or action-based strategy. These methods include observation, tests, and surveys.

Types of Evaluation Research

The Encyclopedia of Evaluation (Mathison, 2004) treats forty-two different evaluation approaches and models ranging from “appreciative inquiry” to “connoisseurship” to “transformative evaluation”. Common types of evaluation research include the following:

- Formative Evaluation

Formative evaluation or baseline survey is a type of evaluation research that involves assessing the needs of the users or target market before embarking on a project. Formative evaluation is the starting point of evaluation research because it sets the tone of the organization’s project and provides useful insights for other types of evaluation.

- Mid-term Evaluation

Mid-term evaluation entails assessing how far a project has come and determining if it is in line with the set goals and objectives. Mid-term reviews allow the organization to determine if a change or modification of the implementation strategy is necessary, and it also serves for tracking the project.

- Summative Evaluation

This type of evaluation is also known as end-term evaluation of project-completion evaluation and it is conducted immediately after the completion of a project. Here, the researcher examines the value and outputs of the program within the context of the projected results.

Summative evaluation allows the organization to measure the degree of success of a project. Such results can be shared with stakeholders, target markets, and prospective investors.

- Outcome Evaluation

Outcome evaluation is primarily target-audience oriented because it measures the effects of the project, program, or product on the users. This type of evaluation views the outcomes of the project through the lens of the target audience and it often measures changes such as knowledge-improvement, skill acquisition, and increased job efficiency.

- Appreciative Enquiry

Appreciative inquiry is a type of evaluation research that pays attention to result-producing approaches. It is predicated on the belief that an organization will grow in whatever direction its stakeholders pay primary attention to such that if all the attention is focused on problems, identifying them would be easy.

In carrying out appreciative inquiry, the research identifies the factors directly responsible for the positive results realized in the course of a project, analyses the reasons for these results, and intensifies the utilization of these factors.

Evaluation Research Methodology

There are four major evaluation research methods, namely; output measurement, input measurement, impact assessment and service quality

- Output/Performance Measurement

Output measurement is a method employed in evaluative research that shows the results of an activity undertaking by an organization. In other words, performance measurement pays attention to the results achieved by the resources invested in a specific activity or organizational process.

More than investing resources in a project, organizations must be able to track the extent to which these resources have yielded results, and this is where performance measurement comes in. Output measurement allows organizations to pay attention to the effectiveness and impact of a process rather than just the process itself.

Other key indicators of performance measurement include user-satisfaction, organizational capacity, market penetration, and facility utilization. In carrying out performance measurement, organizations must identify the parameters that are relevant to the process in question, their industry, and the target markets.

5 Performance Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the cost-effectiveness of this project?

- What is the overall reach of this project?

- How would you rate the market penetration of this project?

- How accessible is the project?

- Is this project time-efficient?

- Input Measurement

In evaluation research, input measurement entails assessing the number of resources committed to a project or goal in any organization. This is one of the most common indicators in evaluation research because it allows organizations to track their investments.

The most common indicator of inputs measurement is the budget which allows organizations to evaluate and limit expenditure for a project. It is also important to measure non-monetary investments like human capital; that is the number of persons needed for successful project execution and production capital.

5 Input Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- What is the budget for this project?

- What is the timeline of this process?

- How many employees have been assigned to this project?

- Do we need to purchase new machinery for this project?

- How many third-parties are collaborators in this project?

- Impact/Outcomes Assessment

In impact assessment, the evaluation researcher focuses on how the product or project affects target markets, both directly and indirectly. Outcomes assessment is somewhat challenging because many times, it is difficult to measure the real-time value and benefits of a project for the users.

In assessing the impact of a process, the evaluation researcher must pay attention to the improvement recorded by the users as a result of the process or project in question. Hence, it makes sense to focus on cognitive and affective changes, expectation-satisfaction, and similar accomplishments of the users.

5 Impact Evaluation Research Questions Examples

- How has this project affected you?

- Has this process affected you positively or negatively?

- What role did this project play in improving your earning power?

- On a scale of 1-10, how excited are you about this project?

- How has this project improved your mental health?

- Service Quality

Service quality is the evaluation research method that accounts for any differences between the expectations of the target markets and their impression of the undertaken project. Hence, it pays attention to the overall service quality assessment carried out by the users.

It is not uncommon for organizations to build the expectations of target markets as they embark on specific projects. Service quality evaluation allows these organizations to track the extent to which the actual product or service delivery fulfils the expectations.

5 Service Quality Evaluation Questions

- On a scale of 1-10, how satisfied are you with the product?

- How helpful was our customer service representative?

- How satisfied are you with the quality of service?

- How long did it take to resolve the issue at hand?

- How likely are you to recommend us to your network?

Uses of Evaluation Research

- Evaluation research is used by organizations to measure the effectiveness of activities and identify areas needing improvement. Findings from evaluation research are key to project and product advancements and are very influential in helping organizations realize their goals efficiently.

- The findings arrived at from evaluation research serve as evidence of the impact of the project embarked on by an organization. This information can be presented to stakeholders, customers, and can also help your organization secure investments for future projects.

- Evaluation research helps organizations to justify their use of limited resources and choose the best alternatives.

- It is also useful in pragmatic goal setting and realization.

- Evaluation research provides detailed insights into projects embarked on by an organization. Essentially, it allows all stakeholders to understand multiple dimensions of a process, and to determine strengths and weaknesses.

- Evaluation research also plays a major role in helping organizations to improve their overall practice and service delivery. This research design allows organizations to weigh existing processes through feedback provided by stakeholders, and this informs better decision making.

- Evaluation research is also instrumental to sustainable capacity building. It helps you to analyze demand patterns and determine whether your organization requires more funds, upskilling or improved operations.

Data Collection Techniques Used in Evaluation Research

In gathering useful data for evaluation research, the researcher often combines quantitative and qualitative research methods . Qualitative research methods allow the researcher to gather information relating to intangible values such as market satisfaction and perception.

On the other hand, quantitative methods are used by the evaluation researcher to assess numerical patterns, that is, quantifiable data. These methods help you measure impact and results; although they may not serve for understanding the context of the process.

Quantitative Methods for Evaluation Research

A survey is a quantitative method that allows you to gather information about a project from a specific group of people. Surveys are largely context-based and limited to target groups who are asked a set of structured questions in line with the predetermined context.

Surveys usually consist of close-ended questions that allow the evaluative researcher to gain insight into several variables including market coverage and customer preferences. Surveys can be carried out physically using paper forms or online through data-gathering platforms like Formplus .

- Questionnaires

A questionnaire is a common quantitative research instrument deployed in evaluation research. Typically, it is an aggregation of different types of questions or prompts which help the researcher to obtain valuable information from respondents.

A poll is a common method of opinion-sampling that allows you to weigh the perception of the public about issues that affect them. The best way to achieve accuracy in polling is by conducting them online using platforms like Formplus.

Polls are often structured as Likert questions and the options provided always account for neutrality or indecision. Conducting a poll allows the evaluation researcher to understand the extent to which the product or service satisfies the needs of the users.

Qualitative Methods for Evaluation Research

- One-on-One Interview

An interview is a structured conversation involving two participants; usually the researcher and the user or a member of the target market. One-on-One interviews can be conducted physically, via the telephone and through video conferencing apps like Zoom and Google Meet.

- Focus Groups

A focus group is a research method that involves interacting with a limited number of persons within your target market, who can provide insights on market perceptions and new products.

- Qualitative Observation

Qualitative observation is a research method that allows the evaluation researcher to gather useful information from the target audience through a variety of subjective approaches. This method is more extensive than quantitative observation because it deals with a smaller sample size, and it also utilizes inductive analysis.

- Case Studies

A case study is a research method that helps the researcher to gain a better understanding of a subject or process. Case studies involve in-depth research into a given subject, to understand its functionalities and successes.

How to Formplus Online Form Builder for Evaluation Survey

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create your evaluation survey by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on “Create Form ” to begin.

- Edit Form Title

Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Evaluation Research Survey”.

Click on the edit button to edit the form.

Add Fields: Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for surveys in the Formplus builder.

Edit fields

Click on “Save”

Preview form.

- Form Customization

With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options

Formplus offers multiple form sharing options which enables you to easily share your evaluation survey with survey respondents. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages.

You can send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Conducting evaluation research allows organizations to determine the effectiveness of their activities at different phases. This type of research can be carried out using qualitative and quantitative data collection methods including focus groups, observation, telephone and one-on-one interviews, and surveys.

Online surveys created and administered via data collection platforms like Formplus make it easier for you to gather and process information during evaluation research. With Formplus multiple form sharing options, it is even easier for you to gather useful data from target markets.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- characteristics of evaluation research

- evaluation research methods

- types of evaluation research

- what is evaluation research

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Formal Assessment: Definition, Types Examples & Benefits

In this article, we will discuss different types and examples of formal evaluation, and show you how to use Formplus for online assessments.

What is Pure or Basic Research? + [Examples & Method]

Simple guide on pure or basic research, its methods, characteristics, advantages, and examples in science, medicine, education and psychology

Assessment vs Evaluation: 11 Key Differences

This article will discuss what constitutes evaluations and assessments along with the key differences between these two research methods.

Recall Bias: Definition, Types, Examples & Mitigation

This article will discuss the impact of recall bias in studies and the best ways to avoid them during research.

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Find My Rep

You are here

Evaluation Research Methods

- Elliot Stern - FAcSS, Emeritus Professor of Evaluation Research, University of Lancaster, UK

- Description

This collection offers a complete guide to evaluations research methods. It is organized in four volumes.

Volume 1 focuses on foundation issues and includes sections on the rationale for evaluation, central methodological debates, the role of theory and applying values, criteria and standards.

Volume 2 examines explaining through evaluation and covers sections on experimentation and causal inference, outcomes and inputs, socio-economic indicators, economics and cost benefit approaches and realist methods.

Volume 3 addresses qualitative methods and includes sections on case studies, responsive, developmental and accompanying evaluation, participation and empowerment, constructivism and postmodernism and multi-criteria and classificatory methods.

Volume 4 concentrates on evaluation to improve policy with sections on performance management, systematic reviews, institutionalization and utilization and policy learning and design.

The collection offers a unique and unparalleled guide to this rapidly expanding research method. It demonstrates how method and theory are applied in policy and strategy and will be an invaluable addition to any social science library.

Elliot Stern is the editor of Evaluation: the International Journal of Theory, Research and Practic e, and works both as an independent consultant. He was previously Principal Advisor for evaluation studies at the Tavistock Institute, London. VOLUME ONE PART ONE: FOUNDATIONS ISSUES IN EVALUATION SECTION ONE: TYPOLOGIES AND PARADIGMS Michael Scriven The Logic of Evaluation and Evaluation Practice George Julnes and Melvin M Mark Evaluation as Sensemaking Knowledge Construction in a Realist World

Preview this book

Select a purchasing option, related products.

Research Evaluation

- First Online: 23 June 2020

Cite this chapter

- Carlo Ghezzi 2

1034 Accesses

1 Citations

- The original version of this chapter was revised. A correction to this chapter can be found at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_7

This chapter is about research evaluation. Evaluation is quintessential to research. It is traditionally performed through qualitative expert judgement. The chapter presents the main evaluation activities in which researchers can be engaged. It also introduces the current efforts towards devising quantitative research evaluation based on bibliometric indicators and critically discusses their limitations, along with their possible (limited and careful) use.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Change history

19 october 2021.

The original version of the chapter was inadvertently published with an error. The chapter has now been corrected.

Notice that the taxonomy presented in Box 5.1 does not cover all kinds of scientific papers. As an example, it does not cover survey papers, which normally are not submitted to a conference.

Private institutions and industry may follow different schemes.

Adler, R., Ewing, J., Taylor, P.: Citation statistics: A report from the international mathematical union (imu) in cooperation with the international council of industrial and applied mathematics (iciam) and the institute of mathematical statistics (ims). Statistical Science 24 (1), 1–14 (2009). URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/20697661

Esposito, F., Ghezzi, C., Hermenegildo, M., Kirchner, H., Ong, L.: Informatics Research Evaluation. Informatics Europe (2018). URL https://www.informatics-europe.org/publications.html

Friedman, B., Schneider, F.B.: Incentivizing quality and impact: Evaluating scholarship in hiring, tenure, and promotion. Computing Research Association (2016). URL https://cra.org/resources/best-practice-memos/incentivizing-quality-and-impact-evaluating-scholarship-in-hiring-tenure-and-promotion/

Hicks, D., Wouters, P., Waltman, L., de Rijcke, S., Rafols, I.: Bibliometrics: The leiden manifesto for research metrics. Nature News 520 (7548), 429 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/520429a . URL http://www.nature.com/news/bibliometrics-the-leiden-manifesto-for-research-metrics-1.17351

Parnas, D.L.: Stop the numbers game. Commun. ACM 50 (11), 19–21 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1145/1297797.1297815 . URL http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1297797.1297815

Patterson, D., Snyder, L., Ullman, J.: Evaluating computer scientists and engineers for promotion and tenure. Computing Research Association (1999). URL https://cra.org/resources/best-practice-memos/incentivizing-quality-and-impact-evaluating-scholarship-in-hiring-tenure-and-promotion/

Saenen, B., Borrell-Damian, L.: Reflections on University Research Assessment: key concepts, issues and actors. European University Association (2019). URL https://eua.eu/component/attachments/attachments.html?id=2144

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dipartimento di Elettronica, Informazione e Bioingegneria, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Carlo Ghezzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carlo Ghezzi .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ghezzi, C. (2020). Research Evaluation. In: Being a Researcher. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_5

Published : 23 June 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-45156-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-45157-8

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Contact Us (315) 303-2040

Evaluation Market Research

Discover expert insights, methodologies, and strategies to make informed business and stay ahead in your industry with evaluation research.

Request a Quote Read the Blog

- Market Research Company Blog

What is Evaluation Research? + [Methods & Examples]

by Emily Taylor

Posted at: 2/20/2023 1:30 PM

Every business and organization has goals.

But, how do you know if the time, money, and resources spent on strategies to achieve these goals are working?

Or, if they’re even worth it?

Evaluation research is a great way to answer these common questions as it measures how effective a specific program or strategy is.

In this post, we’ll cover what evaluation research is, how to conduct it, the benefits of doing so, and more.

Article Contents

- Definition of evaluation research

- The purpose of program evaluation

- Evaluation research advantages and disadvantages

- Research evaluation methods

- Examples and types of evaluation research

- Evaluation research questions

Evaluation Research: Definition

Evaluation research, also known as program evaluation, is a systematic analysis that evaluates whether a program or strategy is worth the effort, time, money, and resources spent to achieve a goal.

Based on the project’s objectives, the study may target different audiences such as:

- Stakeholders

- Prospective customers

- Board members

The feedback gathered from program evaluation research is used to validate whether something should continue or be changed in any way to better meet organizational goals.

The Purpose of Program Evaluation

The main purpose of evaluation research is to understand whether or not a process or strategy has delivered the desired results.

It is especially helpful when launching new products, services, or concepts.

That’s because research program evaluation allows you to gather feedback from target audiences to learn what is working and what needs improvement.

It is a vehicle for hearing people’s experiences with your new concept to gauge whether it is the right fit for the intended audience.

And with data-driven companies being 23 times more likely to acquire customers, it seems like a no-brainer.

As a result of evaluation research, organizations can better build a program or solution that provides audiences with exactly what they need.

Better yet, it’s done without wasting time and money figuring out new iterations before landing on the final product.

Evaluation Research Advantages & Disadvantages

In this section, our market research company dives more into the benefits and drawbacks of conducting research evaluation methods.

Understanding these pros and cons will help determine if it’s right for your business.

Advantages of Evaluation Research

In many instances, the pros of program evaluation outweigh the cons.

It is an effective tool for data-driven decision-making and sets organizations on a clear path to success.

Here are just a few of the many benefits of conducting research evaluation methods.

Justifies the time, money, and resources spent

First, evaluation research helps justify all of the resources spent on a program or strategy.

Without evaluation research, it can be difficult to promote the continuation of a costly or time-intensive activity with no evidence it’s working.

Rather than relying on opinions and gut reactions about the effectiveness of a program or strategy, evaluation research measures levels of effectiveness through data collected.

Identifies unknown negative or positive impacts of a strategy

Second, program research helps users better understand how projects are carried out, who helps them come to fruition, who is affected, and more.

These finer details shed light on how a program or strategy affects all facets of an organization.

As a result, you may learn there are unrealized effects that surprise you and your decision-makers.

Helps organizations improve

The research can highlight areas of strengths (i.e., factors of the program/strategy that should not be changed) and weaknesses (i.e., factors of the programs/strategy that could be improved).

Disadvantages of Evaluation Research

Despite its many advantages, there are still limitations and drawbacks to evaluation research.

Here are a few challenges to keep in mind before moving forward.

It can be costly

The cost of market research varies based on methodology, audience type, incentives, and more.

For instance, a focus group will be more expensive than an online survey.

Though, I’ll also make the argument that conducting evaluation research can save brands money down the line from investing in something that is a dud.

Poor memory recall

Many research evaluation methods are dependent on feedback from customers, employees, and other audiences.

If the study is not conducted right after a process or strategy is implemented, it can be harder for these audiences to remember their true opinions and feelings on the matter.

Therefore, the data might be less accurate because of the lapse in time and memory.

Research Evaluation Methods

Evaluation research can include a mix of qualitative and quantitative methods depending on your objectives.

A market research company , like Drive Research , can design an approach to best meet your goals, objectives, and budget for a successful study.

Below we share different approaches to evaluation research.

But, here is a quick graphic that explains the main differences between qualitative and quantitative research methodologies .

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative evaluation research aims to measure audience feedback.

Metrics quantitative market research often measures include:

- Level of impact

- Level of awareness

- Level of satisfaction

- Level of perception

- Expected usage

- Usage of competitors

In addition to other metrics to gauge the success of a program or strategy.

This type of evaluation research can be done through online surveys or phone surveys.

Online surveys

Perhaps the most common form of quantitative research , online surveys are extremely effective for gathering feedback.

They are commonly used for evaluation research because they offer quick, cost-effective, and actionable insights.

Typically, the survey is conducted by a third-party online survey company to ensure anonymity and limit bias from the respondents.

The market research firm develops the survey, conducts fieldwork, and creates a report based on the results.

For instance, here is the online survey process followed by Drive Research when conducting program evaluations for our clients.

Phone surveys

Another way to conduct evaluation research is with phone surveys .

This type of market research allows trained interviewers to have one-on-one conversations with your target audience.

Oftentimes they range from 15 to 30-minute discussions to gather enough information and feedback.

The benefit of phone surveys for program evaluation research is that interviewers can ask respondents to explain their answers in more detail.

Whereas, an online survey is limited to multiple-choice questions with pre-determined answer options (with the addition of a few open ends).

Though, online surveys are much faster and more cost-effective to complete.

Recommended Reading: What is the Most Cost-Effective Market Research Methodology?

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative evaluation research aims to explore audience feedback.

Factors quantitative market research often evaluates include:

- Areas of satisfaction

- Areas of weaknesses

- Recommendations

This type of exploratory evaluation research can be completed through in-depth interviews or focus groups.

It involves working with a qualitative recruiting company to recruit specific types of people for the research, developing a specific line of questioning, and then summarizing the results to ensure anonymity.

For instance, here is the process Drive Research follows when recruiting people to participate in evaluation research.

Focus groups

If you are considering conducting qualitative evaluation research, it’s likely that focus groups are your top methodology of choice.

Focus groups are a great way to collect feedback from targeted audiences all at once.

It is also a helpful methodology for showing product markups, logo designs, commercials, and more.

Though, a great alternative to traditional focus groups is online focus groups .

Remote focus groups can reduce the costs of evaluation research because it eliminates many of the fees associated with in-person groups.

For instance, there are no facility rental fees.

Plus, recruiting participants is cheaper because you can cast a wider net being that they can join an online forum from anywhere in the country.

In-depth interviews (IDIs)

Similar to focus groups, in-depth interviews gather tremendous amounts of information and feedback from target consumers.

In this setting though, interviewers speak with participants one-on-one, rather than in a group.

This level of attention allows interviewers to expand on more areas of what satisfies and dissatisfies someone about a product, service, or program.

Additionally, it eliminates group bias in evaluation research.

This is because participants are more comfortable providing honest opinions without being intimidated by others in a focus group.

Examples and Types of Evaluation Research

There are different types of evaluation research based on the business and audience type.

Most commonly it is carried out for product concepts, marketing strategies, and programs.

We share a few examples of each below.

Product Evaluation Research Example

Each year, 95 percent of new products introduced to the market fail.

Therefore market research for new product development is critical in determining what could deter the success of a concept before it reaches shelves.

Lego is a great example of a brand using evaluation research for new product concepts.

In 2011 they learned 90% of their buyers were boys.

Although boys were not their sole target demographic, the brand had more products that were appealing to this audience such as Star Wars and superheroes.

To grow its audience, Lego conducted evaluation research to determine what topics and themes would entice female buyers.

With this insight, Lego launched Lego Friends. It included more details and features girls were looking for.

Marketing Evaluation Research Example

Marketing evaluation research or campaign evaluation surveys is a technique used to measure the effectiveness of advertising and marketing strategies.

An example of this would be surveying a target audience before and after launching a paid social media campaign.

Brands can determine if factors such as awareness, perception, and likelihood to purchase have changed due to the advertisements.

Recommended Reading: Advertising Testing with Market Research

Process Evaluation Research Example

Process evaluations are commonly used to understand the implementation of a new program.

It helps decision-makers evaluate how a program’s goal or outcome was achieved.

Additionally, process evaluation research quantifies how often the program was used, who benefited from the program, the resources used to implement the new process, any problems encountered, and more.

Examples of programs and processes where evaluation research is beneficial are:

- Customer loyalty programs

- Client referral programs

- Customer retention programs

- Workplace wellness programs

- Orientation of new employees

- Employee buddy programs

Evaluation Research Questions

Evaluation research design sets the tone for a successful study.

It is important to ask the right questions in order to achieve the intended results.

Product evaluation research questions include:

- How appealing is the following product concept?

- If available in a store near you, how likely are you to purchase [product]?

- Which of the following packaging types do you prefer?

- Which of the following [colors, flavors, sizes, etc.] would you be most interested in purchasing?

Marketing evaluation research questions include:

- Please rate your level of awareness for [Brand].

- What is your perception of [Brand]?

- Do you remember seeing advertisements for [Brand] in the past 3 months?

- Where did you see or hear the advertising for [Brand]? ie. Facebook, TV, radio, etc.

- How likely are you to make a purchase from [Brand]?

Process evaluation research questions include:

- Please rate your level of satisfaction with [Process].

- Please explain why you provided [Rating].

- What barriers existed to implementing [Process]?

- How likely are you to use [Process] moving forward?

- Please rate your level of agreement with the following statement: I find a lot of value in [Process].

While these are great examples of what evaluation research questions to ask, keep in mind they should be reflective of your unique goals and objectives.

Our evaluation research company can help design, program, field, and analyze your survey to assure you are using quality data to drive decision-making.

Contact Our Evaluation Research Company

Wondering if continuing an employee or customer program is still offering value to your organization? Or, perhaps you need to determine if a new product concept is working as effectively as it should be. Evaluation research can help achieve these objectives and plenty of others.

Drive Research is a full-service market research company specializing in evaluation research through surveys, focus groups, and IDIs. Contact our team by filling out the form below or emailing [email protected] .

Emily Taylor

As a Research Manager, Emily is approaching a decade of experience in the market research industry and loves to challenge the status quo. She is a certified VoC professional with a passion for storytelling.

Learn more about Emily, here .

Categories: Market Research Glossary

Need help with your project? Get in touch with Drive Research.

View Our Blog

- DOI: 10.1353/lib.2006.0050

- Corpus ID: 21005052

Evaluation Research: An Overview

- Published in Library Trends 6 September 2006

- Education, Sociology

112 Citations

A study on the development of standard indicators for college & university libraries' evaluation, quantitative research: a successful investigation in natural and social sciences, assessing the effectiveness and quality of libraries, evaluation inquiry in donor funded programmes in northern ghana: experiences of programme staff, the efficient team-driven quality scholarship model: a process evaluation of collaborative research, the context, input process, product (cipp) evaluation model as a comprehensive framework for evaluating online english learning towards the industrial revolution era 5.0, an approach to evaluating latin american university libraries, the historical development of evaluation use, assessment of effectiveness of public integrity training workshops for civil servants – a case study, duck soup and library outcome evaluation, 54 references, qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.), the development of self-assessment tool-kits for the library and information sector, benchmarking: a process for improvement., outcomes assessment in the networked environment: research questions, issues, considerations, and moving forward, evaluating the school library media center, a theory-guided approach to library services assessment, basic research methods for librarians, evaluation: a systematic approach, bridging the gulf: mixed methods and library service evaluation, building evaluation capacity: activities for teaching and training, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Understanding Evaluation Methodologies: M&E Methods and Techniques for Assessing Performance and Impact

- Learning Center

This article provides an overview and comparison of the different types of evaluation methodologies used to assess the performance, effectiveness, quality, or impact of services, programs, and policies. There are several methodologies both qualitative and quantitative, including surveys, interviews, observations, case studies, focus groups, and more…In this essay, we will discuss the most commonly used qualitative and quantitative evaluation methodologies in the M&E field.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Evaluation Methodologies: Definition and Importance

- Types of Evaluation Methodologies: Overview and Comparison

- Program Evaluation methodologies

- Qualitative Methodologies in Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E)

- Quantitative Methodologies in Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E)

- What are the M&E Methods?

- Difference Between Evaluation Methodologies and M&E Methods

- Choosing the Right Evaluation Methodology: Factors and Criteria

- Our Conclusion on Evaluation Methodologies

1. Introduction to Evaluation Methodologies: Definition and Importance

Evaluation methodologies are the methods and techniques used to measure the performance, effectiveness, quality, or impact of various interventions, services, programs, and policies. Evaluation is essential for decision-making, improvement, and innovation, as it helps stakeholders identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats and make informed decisions to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of their operations.

Evaluation methodologies can be used in various fields and industries, such as healthcare, education, business, social services, and public policy. The choice of evaluation methodology depends on the specific goals of the evaluation, the type and level of data required, and the resources available for conducting the evaluation.

The importance of evaluation methodologies lies in their ability to provide evidence-based insights into the performance and impact of the subject being evaluated. This information can be used to guide decision-making, policy development, program improvement, and innovation. By using evaluation methodologies, stakeholders can assess the effectiveness of their operations and make data-driven decisions to improve their outcomes.

Overall, understanding evaluation methodologies is crucial for individuals and organizations seeking to enhance their performance, effectiveness, and impact. By selecting the appropriate evaluation methodology and conducting a thorough evaluation, stakeholders can gain valuable insights and make informed decisions to improve their operations and achieve their goals.

2. Types of Evaluation Methodologies: Overview and Comparison

Evaluation methodologies can be categorized into two main types based on the type of data they collect: qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative methodologies collect non-numerical data, such as words, images, or observations, while quantitative methodologies collect numerical data that can be analyzed statistically. Here is an overview and comparison of the main differences between qualitative and quantitative evaluation methodologies:

Qualitative Evaluation Methodologies:

- Collect non-numerical data, such as words, images, or observations.

- Focus on exploring complex phenomena, such as attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors, and understanding the meaning and context behind them.

- Use techniques such as interviews, observations, case studies, and focus groups to collect data.

- Emphasize the subjective nature of the data and the importance of the researcher’s interpretation and analysis.

- Provide rich and detailed insights into people’s experiences and perspectives.

- Limitations include potential bias from the researcher, limited generalizability of findings, and challenges in analyzing and synthesizing the data.

Quantitative Evaluation Methodologies:

- Collect numerical data that can be analyzed statistically.

- Focus on measuring specific variables and relationships between them, such as the effectiveness of an intervention or the correlation between two factors.

- Use techniques such as surveys and experimental designs to collect data.

- Emphasize the objectivity of the data and the importance of minimizing bias and variability.

- Provide precise and measurable data that can be compared and analyzed statistically.

- Limitations include potential oversimplification of complex phenomena, limited contextual information, and challenges in collecting and analyzing data.

Choosing between qualitative and quantitative evaluation methodologies depends on the specific goals of the evaluation, the type and level of data required, and the resources available for conducting the evaluation. Some evaluations may use a mixed-methods approach that combines both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis techniques to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the subject being evaluated.

3. Program evaluation methodologies

Program evaluation methodologies encompass a diverse set of approaches and techniques used to assess the effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of programs and interventions. These methodologies provide systematic frameworks for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data to determine the extent to which program objectives are being met and to identify areas for improvement. Common program evaluation methodologies include quantitative methods such as experimental designs, quasi-experimental designs, and surveys, as well as qualitative approaches like interviews, focus groups, and case studies.

Each methodology offers unique advantages and limitations depending on the nature of the program being evaluated, the available resources, and the research questions at hand. By employing rigorous program evaluation methodologies, organizations can make informed decisions, enhance program effectiveness, and maximize the use of resources to achieve desired outcomes.

Catch HR’s eye instantly?

- Resume Review

- Resume Writing

- Resume Optimization

Premier global development resume service since 2012

Stand Out with a Pro Resume

4. Qualitative Methodologies in Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E)

Qualitative methodologies are increasingly being used in monitoring and evaluation (M&E) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact and effectiveness of programs and interventions. Qualitative methodologies can help to explore the underlying reasons and contexts that contribute to program outcomes and identify areas for improvement. Here are some common qualitative methodologies used in M&E:

Interviews involve one-on-one or group discussions with stakeholders to collect data on their experiences, perspectives, and perceptions. Interviews can provide rich and detailed data on the effectiveness of a program, the factors that contribute to its success or failure, and the ways in which it can be improved.

Observations

Observations involve the systematic and objective recording of behaviors and interactions of stakeholders in a natural setting. Observations can help to identify patterns of behavior, the effectiveness of program interventions, and the ways in which they can be improved.

Document review

Document review involves the analysis of program documents, such as reports, policies, and procedures, to understand the program context, design, and implementation. Document review can help to identify gaps in program design or implementation and suggest ways in which they can be improved.

Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA)

PRA is a participatory approach that involves working with communities to identify and analyze their own problems and challenges. It involves using participatory techniques such as mapping, focus group discussions, and transect walks to collect data on community perspectives, experiences, and priorities. PRA can help ensure that the evaluation is community-driven and culturally appropriate, and can provide valuable insights into the social and cultural factors that influence program outcomes.

Key Informant Interviews

Key informant interviews are in-depth, open-ended interviews with individuals who have expert knowledge or experience related to the program or issue being evaluated. Key informants can include program staff, community leaders, or other stakeholders. These interviews can provide valuable insights into program implementation and effectiveness, and can help identify areas for improvement.

Ethnography

Ethnography is a qualitative method that involves observing and immersing oneself in a community or culture to understand their perspectives, values, and behaviors. Ethnographic methods can include participant observation, interviews, and document analysis, among others. Ethnography can provide a more holistic understanding of program outcomes and impacts, as well as the broader social context in which the program operates.

Focus Group Discussions

Focus group discussions involve bringing together a small group of individuals to discuss a specific topic or issue related to the program. Focus group discussions can be used to gather qualitative data on program implementation, participant experiences, and program outcomes. They can also provide insights into the diversity of perspectives within a community or stakeholder group .

Photovoice is a qualitative method that involves using photography as a tool for community empowerment and self-expression. Participants are given cameras and asked to take photos that represent their experiences or perspectives on a program or issue. These photos can then be used to facilitate group discussions and generate qualitative data on program outcomes and impacts.

Case Studies

Case studies involve gathering detailed qualitative data through interviews, document analysis, and observation, and can provide a more in-depth understanding of a specific program component. They can be used to explore the experiences and perspectives of program participants or stakeholders and can provide insights into program outcomes and impacts.

Qualitative methodologies in M&E are useful for identifying complex and context-dependent factors that contribute to program outcomes, and for exploring stakeholder perspectives and experiences. Qualitative methodologies can provide valuable insights into the ways in which programs can be improved and can complement quantitative methodologies in providing a comprehensive understanding of program impact and effectiveness

5. Quantitative Methodologies in Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E)

Quantitative methodologies are commonly used in monitoring and evaluation (M&E) to measure program outcomes and impact in a systematic and objective manner. Quantitative methodologies involve collecting numerical data that can be analyzed statistically to provide insights into program effectiveness, efficiency, and impact. Here are some common quantitative methodologies used in M&E:

Surveys involve collecting data from a large number of individuals using standardized questionnaires or surveys. Surveys can provide quantitative data on people’s attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and experiences, and can help to measure program outcomes and impact.

Baseline and Endline Surveys

Baseline and endline surveys are quantitative surveys conducted at the beginning and end of a program to measure changes in knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, or other outcomes. These surveys can provide a snapshot of program impact and allow for comparisons between pre- and post-program data.