- Corpus ID: 43910248

The case study as a type of qualitative research

- Adrijana Biba Starman

- Published 2013

384 Citations

The qualitative report the, including rigor and artistry in case study as a strategic qualitative methodology, advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language, the complex research method in the qualitative analysis, qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects, strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research methods, from a case to a case study—and back, or on the search for everyman in biographical research, combining ideal types of performance and performance regimes, critical thinking skills and their impacts on elementary school students, live projects: a mixed-methods exploration of existing scholarship, 20 references, case study as a research strategy: some ambiguities and opportunities, what is a case study and what is it good for.

- Highly Influential

Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation for Novice Researchers

Five misunderstandings about case-study research, a typology for the case study in social science following a review of definition, discourse, and structure.

- 13 Excerpts

Encyclopedia of case study research

Case studies and theory development in the social sciences, research design: qualitative and quantitative approaches, kvalitativno raziskovanje na pedagoškem področju, case study research in practice, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Transformative Design – Methods, Types, Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

One-to-One Interview – Methods and Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

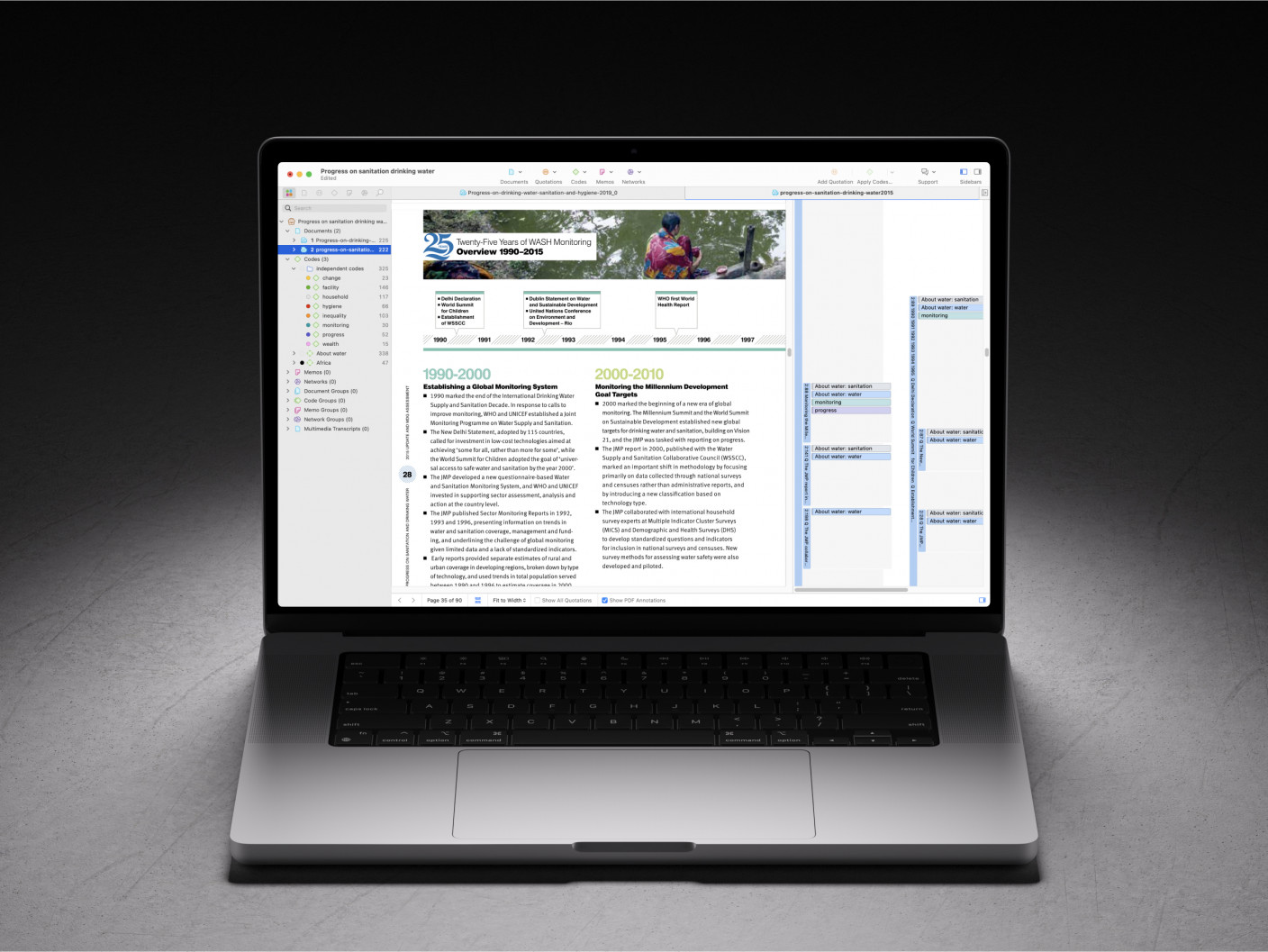

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved September 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Libr Assoc

- v.107(1); 2019 Jan

Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type

The purpose of this editorial is to distinguish between case reports and case studies. In health, case reports are familiar ways of sharing events or efforts of intervening with single patients with previously unreported features. As a qualitative methodology, case study research encompasses a great deal more complexity than a typical case report and often incorporates multiple streams of data combined in creative ways. The depth and richness of case study description helps readers understand the case and whether findings might be applicable beyond that setting.

Single-institution descriptive reports of library activities are often labeled by their authors as “case studies.” By contrast, in health care, single patient retrospective descriptions are published as “case reports.” Both case reports and case studies are valuable to readers and provide a publication opportunity for authors. A previous editorial by Akers and Amos about improving case studies addresses issues that are more common to case reports; for example, not having a review of the literature or being anecdotal, not generalizable, and prone to various types of bias such as positive outcome bias [ 1 ]. However, case study research as a qualitative methodology is pursued for different purposes than generalizability. The authors’ purpose in this editorial is to clearly distinguish between case reports and case studies. We believe that this will assist authors in describing and designating the methodological approach of their publications and help readers appreciate the rigor of well-executed case study research.

Case reports often provide a first exploration of a phenomenon or an opportunity for a first publication by a trainee in the health professions. In health care, case reports are familiar ways of sharing events or efforts of intervening with single patients with previously unreported features. Another type of study categorized as a case report is an “N of 1” study or single-subject clinical trial, which considers an individual patient as the sole unit of observation in a study investigating the efficacy or side effect profiles of different interventions. Entire journals have evolved to publish case reports, which often rely on template structures with limited contextualization or discussion of previous cases. Examples that are indexed in MEDLINE include the American Journal of Case Reports , BMJ Case Reports, Journal of Medical Case Reports, and Journal of Radiology Case Reports . Similar publications appear in veterinary medicine and are indexed in CAB Abstracts, such as Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine and Veterinary Record Case Reports .

As a qualitative methodology, however, case study research encompasses a great deal more complexity than a typical case report and often incorporates multiple streams of data combined in creative ways. Distinctions include the investigator’s definitions and delimitations of the case being studied, the clarity of the role of the investigator, the rigor of gathering and combining evidence about the case, and the contextualization of the findings. Delimitation is a term from qualitative research about setting boundaries to scope the research in a useful way rather than describing the narrow scope as a limitation, as often appears in a discussion section. The depth and richness of description helps readers understand the situation and whether findings from the case are applicable to their settings.

CASE STUDY AS A RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Case study as a qualitative methodology is an exploration of a time- and space-bound phenomenon. As qualitative research, case studies require much more from their authors who are acting as instruments within the inquiry process. In the case study methodology, a variety of methodological approaches may be employed to explain the complexity of the problem being studied [ 2 , 3 ].

Leading authors diverge in their definitions of case study, but a qualitative research text introduces case study as follows:

Case study research is defined as a qualitative approach in which the investigator explores a real-life, contemporary bounded system (a case) or multiple bound systems (cases) over time, through detailed, in-depth data collection involving multiple sources of information, and reports a case description and case themes. The unit of analysis in the case study might be multiple cases (a multisite study) or a single case (a within-site case study). [ 4 ]

Methodologists writing core texts on case study research include Yin [ 5 ], Stake [ 6 ], and Merriam [ 7 ]. The approaches of these three methodologists have been compared by Yazan, who focused on six areas of methodology: epistemology (beliefs about ways of knowing), definition of cases, design of case studies, and gathering, analysis, and validation of data [ 8 ]. For Yin, case study is a method of empirical inquiry appropriate to determining the “how and why” of phenomena and contributes to understanding phenomena in a holistic and real-life context [ 5 ]. Stake defines a case study as a “well-bounded, specific, complex, and functioning thing” [ 6 ], while Merriam views “the case as a thing, a single entity, a unit around which there are boundaries” [ 7 ].

Case studies are ways to explain, describe, or explore phenomena. Comments from a quantitative perspective about case studies lacking rigor and generalizability fail to consider the purpose of the case study and how what is learned from a case study is put into practice. Rigor in case studies comes from the research design and its components, which Yin outlines as (a) the study’s questions, (b) the study’s propositions, (c) the unit of analysis, (d) the logic linking the data to propositions, and (e) the criteria for interpreting the findings [ 5 ]. Case studies should also provide multiple sources of data, a case study database, and a clear chain of evidence among the questions asked, the data collected, and the conclusions drawn [ 5 ].

Sources of evidence for case studies include interviews, documentation, archival records, direct observations, participant-observation, and physical artifacts. One of the most important sources for data in qualitative case study research is the interview [ 2 , 3 ]. In addition to interviews, documents and archival records can be gathered to corroborate and enhance the findings of the study. To understand the phenomenon or the conditions that created it, direct observations can serve as another source of evidence and can be conducted throughout the study. These can include the use of formal and informal protocols as a participant inside the case or an external or passive observer outside of the case [ 5 ]. Lastly, physical artifacts can be observed and collected as a form of evidence. With these multiple potential sources of evidence, the study methodology includes gathering data, sense-making, and triangulating multiple streams of data. Figure 1 shows an example in which data used for the case started with a pilot study to provide additional context to guide more in-depth data collection and analysis with participants.

Key sources of data for a sample case study

VARIATIONS ON CASE STUDY METHODOLOGY

Case study methodology is evolving and regularly reinterpreted. Comparative or multiple case studies are used as a tool for synthesizing information across time and space to research the impact of policy and practice in various fields of social research [ 9 ]. Because case study research is in-depth and intensive, there have been efforts to simplify the method or select useful components of cases for focused analysis. Micro-case study is a term that is occasionally used to describe research on micro-level cases [ 10 ]. These are cases that occur in a brief time frame, occur in a confined setting, and are simple and straightforward in nature. A micro-level case describes a clear problem of interest. Reporting is very brief and about specific points. The lack of complexity in the case description makes obvious the “lesson” that is inherent in the case; although no definitive “solution” is necessarily forthcoming, making the case useful for discussion. A micro-case write-up can be distinguished from a case report by its focus on briefly reporting specific features of a case or cases to analyze or learn from those features.

DATABASE INDEXING OF CASE REPORTS AND CASE STUDIES

Disciplines such as education, psychology, sociology, political science, and social work regularly publish rich case studies that are relevant to particular areas of health librarianship. Case reports and case studies have been defined as publication types or subject terms by several databases that are relevant to librarian authors: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ERIC. Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA) does not have a subject term or publication type related to cases, despite many being included in the database. Whereas “Case Reports” are the main term used by MEDLINE’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and PsycINFO’s thesaurus, CINAHL and ERIC use “Case Studies.”

Case reports in MEDLINE and PsycINFO focus on clinical case documentation. In MeSH, “Case Reports” as a publication type is specific to “clinical presentations that may be followed by evaluative studies that eventually lead to a diagnosis” [ 11 ]. “Case Histories,” “Case Studies,” and “Case Study” are all entry terms mapping to “Case Reports”; however, guidance to indexers suggests that “Case Reports” should not be applied to institutional case reports and refers to the heading “Organizational Case Studies,” which is defined as “descriptions and evaluations of specific health care organizations” [ 12 ].

PsycINFO’s subject term “Case Report” is “used in records discussing issues involved in the process of conducting exploratory studies of single or multiple clinical cases.” The Methodology index offers clinical and non-clinical entries. “Clinical Case Study” is defined as “case reports that include disorder, diagnosis, and clinical treatment for individuals with mental or medical illnesses,” whereas “Non-clinical Case Study” is a “document consisting of non-clinical or organizational case examples of the concepts being researched or studied. The setting is always non-clinical and does not include treatment-related environments” [ 13 ].

Both CINAHL and ERIC acknowledge the depth of analysis in case study methodology. The CINAHL scope note for the thesaurus term “Case Studies” distinguishes between the document and the methodology, though both use the same term: “a review of a particular condition, disease, or administrative problem. Also, a research method that involves an in-depth analysis of an individual, group, institution, or other social unit. For material that contains a case study, search for document type: case study.” The ERIC scope note for the thesaurus term “Case Studies” is simple: “detailed analyses, usually focusing on a particular problem of an individual, group, or organization” [ 14 ].

PUBLICATION OF CASE STUDY RESEARCH IN LIBRARIANSHIP

We call your attention to a few examples published as case studies in health sciences librarianship to consider how their characteristics fit with the preceding definitions of case reports or case study research. All present some characteristics of case study research, but their treatment of the research questions, richness of description, and analytic strategies vary in depth and, therefore, diverge at some level from the qualitative case study research approach. This divergence, particularly in richness of description and analysis, may have been constrained by the publication requirements.

As one example, a case study by Janke and Rush documented a time- and context-bound collaboration involving a librarian and a nursing faculty member [ 15 ]. Three objectives were stated: (1) describing their experience of working together on an interprofessional research team, (2) evaluating the value of the librarian role from librarian and faculty member perspectives, and (3) relating findings to existing literature. Elements that signal the qualitative nature of this case study are that the authors were the research participants and their use of the term “evaluation” is reflection on their experience. This reads like a case study that could have been enriched by including other types of data gathered from others engaging with this team to broaden the understanding of the collaboration.

As another example, the description of the academic context is one of the most salient components of the case study written by Clairoux et al., which had the objectives of (1) describing the library instruction offered and learning assessments used at a single health sciences library and (2) discussing the positive outcomes of instruction in that setting [ 16 ]. The authors focus on sharing what the institution has done more than explaining why this institution is an exemplar to explore a focused question or understand the phenomenon of library instruction. However, like a case study, the analysis brings together several streams of data including course attendance, online material page views, and some discussion of results from surveys. This paper reads somewhat in between an institutional case report and a case study.

The final example is a single author reporting on a personal experience of creating and executing the role of research informationist for a National Institutes of Health (NIH)–funded research team [ 17 ]. There is a thoughtful review of the informationist literature and detailed descriptions of the institutional context and the process of gaining access to and participating in the new role. However, the motivating question in the abstract does not seem to be fully addressed through analysis from either the reflective perspective of the author as the research participant or consideration of other streams of data from those involved in the informationist experience. The publication reads more like a case report about this informationist’s experience than a case study that explores the research informationist experience through the selection of this case.

All of these publications are well written and useful for their intended audiences, but in general, they are much shorter and much less rich in depth than case studies published in social sciences research. It may be that the authors have been constrained by word counts or page limits. For example, the submission category for Case Studies in the Journal of the Medical Library Association (JMLA) limited them to 3,000 words and defined them as “articles describing the process of developing, implementing, and evaluating a new service, program, or initiative, typically in a single institution or through a single collaborative effort” [ 18 ]. This definition’s focus on novelty and description sounds much more like the definition of case report than the in-depth, detailed investigation of a time- and space-bound problem that is often examined through case study research.

Problem-focused or question-driven case study research would benefit from the space provided for Original Investigations that employ any type of quantitative or qualitative method of analysis. One of the best examples in the JMLA of an in-depth multiple case study that was authored by a librarian who published the findings from her doctoral dissertation represented all the elements of a case study. In eight pages, she provided a theoretical basis for the research question, a pilot study, and a multiple case design, including integrated data from interviews and focus groups [ 19 ].

We have distinguished between case reports and case studies primarily to assist librarians who are new to research and critical appraisal of case study methodology to recognize the features that authors use to describe and designate the methodological approaches of their publications. For researchers who are new to case research methodology and are interested in learning more, Hancock and Algozzine provide a guide [ 20 ].

We hope that JMLA readers appreciate the rigor of well-executed case study research. We believe that distinguishing between descriptive case reports and analytic case studies in the journal’s submission categories will allow the depth of case study methodology to increase. We also hope that authors feel encouraged to pursue submitting relevant case studies or case reports for future publication.

Editor’s note: In response to this invited editorial, the Journal of the Medical Library Association will consider manuscripts employing rigorous qualitative case study methodology to be Original Investigations (fewer than 5,000 words), whereas manuscripts describing the process of developing, implementing, and assessing a new service, program, or initiative—typically in a single institution or through a single collaborative effort—will be considered to be Case Reports (formerly known as Case Studies; fewer than 3,000 words).

Qualitative research: methods and examples

Last updated

13 April 2023

Reviewed by

Qualitative research involves gathering and evaluating non-numerical information to comprehend concepts, perspectives, and experiences. It’s also helpful for obtaining in-depth insights into a certain subject or generating new research ideas.

As a result, qualitative research is practical if you want to try anything new or produce new ideas.

There are various ways you can conduct qualitative research. In this article, you'll learn more about qualitative research methodologies, including when you should use them.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a broad term describing various research types that rely on asking open-ended questions. Qualitative research investigates “how” or “why” certain phenomena occur. It is about discovering the inherent nature of something.

The primary objective of qualitative research is to understand an individual's ideas, points of view, and feelings. In this way, collecting in-depth knowledge of a specific topic is possible. Knowing your audience's feelings about a particular subject is important for making reasonable research conclusions.

Unlike quantitative research , this approach does not involve collecting numerical, objective data for statistical analysis. Qualitative research is used extensively in education, sociology, health science, history, and anthropology.

- Types of qualitative research methodology

Typically, qualitative research aims at uncovering the attitudes and behavior of the target audience concerning a specific topic. For example, “How would you describe your experience as a new Dovetail user?”

Some of the methods for conducting qualitative analysis include:

Focus groups

Hosting a focus group is a popular qualitative research method. It involves obtaining qualitative data from a limited sample of participants. In a moderated version of a focus group, the moderator asks participants a series of predefined questions. They aim to interact and build a group discussion that reveals their preferences, candid thoughts, and experiences.

Unmoderated, online focus groups are increasingly popular because they eliminate the need to interact with people face to face.

Focus groups can be more cost-effective than 1:1 interviews or studying a group in a natural setting and reporting one’s observations.

Focus groups make it possible to gather multiple points of view quickly and efficiently, making them an excellent choice for testing new concepts or conducting market research on a new product.

However, there are some potential drawbacks to this method. It may be unsuitable for sensitive or controversial topics. Participants might be reluctant to disclose their true feelings or respond falsely to conform to what they believe is the socially acceptable answer (known as response bias).

Case study research

A case study is an in-depth evaluation of a specific person, incident, organization, or society. This type of qualitative research has evolved into a broadly applied research method in education, law, business, and the social sciences.

Even though case study research may appear challenging to implement, it is one of the most direct research methods. It requires detailed analysis, broad-ranging data collection methodologies, and a degree of existing knowledge about the subject area under investigation.

Historical model

The historical approach is a distinct research method that deeply examines previous events to better understand the present and forecast future occurrences of the same phenomena. Its primary goal is to evaluate the impacts of history on the present and hence discover comparable patterns in the present to predict future outcomes.

Oral history

This qualitative data collection method involves gathering verbal testimonials from individuals about their personal experiences. It is widely used in historical disciplines to offer counterpoints to established historical facts and narratives. The most common methods of gathering oral history are audio recordings, analysis of auto-biographical text, videos, and interviews.

Qualitative observation

One of the most fundamental, oldest research methods, qualitative observation , is the process through which a researcher collects data using their senses of sight, smell, hearing, etc. It is used to observe the properties of the subject being studied. For example, “What does it look like?” As research methods go, it is subjective and depends on researchers’ first-hand experiences to obtain information, so it is prone to bias. However, it is an excellent way to start a broad line of inquiry like, “What is going on here?”

Record keeping and review

Record keeping uses existing documents and relevant data sources that can be employed for future studies. It is equivalent to visiting the library and going through publications or any other reference material to gather important facts that will likely be used in the research.

Grounded theory approach

The grounded theory approach is a commonly used research method employed across a variety of different studies. It offers a unique way to gather, interpret, and analyze. With this approach, data is gathered and analyzed simultaneously. Existing analysis frames and codes are disregarded, and data is analyzed inductively, with new codes and frames generated from the research.

Ethnographic research

Ethnography is a descriptive form of a qualitative study of people and their cultures. Its primary goal is to study people's behavior in their natural environment. This method necessitates that the researcher adapts to their target audience's setting.

Thereby, you will be able to understand their motivation, lifestyle, ambitions, traditions, and culture in situ. But, the researcher must be prepared to deal with geographical constraints while collecting data i.e., audiences can’t be studied in a laboratory or research facility.

This study can last from a couple of days to several years. Thus, it is time-consuming and complicated, requiring you to have both the time to gather the relevant data as well as the expertise in analyzing, observing, and interpreting data to draw meaningful conclusions.

Narrative framework

A narrative framework is a qualitative research approach that relies on people's written text or visual images. It entails people analyzing these events or narratives to determine certain topics or issues. With this approach, you can understand how people represent themselves and their experiences to a larger audience.

Phenomenological approach

The phenomenological study seeks to investigate the experiences of a particular phenomenon within a group of individuals or communities. It analyzes a certain event through interviews with persons who have witnessed it to determine the connections between their views. Even though this method relies heavily on interviews, other data sources (recorded notes), and observations could be employed to enhance the findings.

- Qualitative research methods (tools)

Some of the instruments involved in qualitative research include:

Document research: Also known as document analysis because it involves evaluating written documents. These can include personal and non-personal materials like archives, policy publications, yearly reports, diaries, or letters.

Focus groups: This is where a researcher poses questions and generates conversation among a group of people. The major goal of focus groups is to examine participants' experiences and knowledge, including research into how and why individuals act in various ways.

Secondary study: Involves acquiring existing information from texts, images, audio, or video recordings.

Observations: This requires thorough field notes on everything you see, hear, or experience. Compared to reported conduct or opinion, this study method can assist you in getting insights into a specific situation and observable behaviors.

Structured interviews : In this approach, you will directly engage people one-on-one. Interviews are ideal for learning about a person's subjective beliefs, motivations, and encounters.

Surveys: This is when you distribute questionnaires containing open-ended questions

Free AI content analysis generator

Make sense of your research by automatically summarizing key takeaways through our free content analysis tool.

- What are common examples of qualitative research?

Everyday examples of qualitative research include:

Conducting a demographic analysis of a business

For instance, suppose you own a business such as a grocery store (or any store) and believe it caters to a broad customer base, but after conducting a demographic analysis, you discover that most of your customers are men.

You could do 1:1 interviews with female customers to learn why they don't shop at your store.

In this case, interviewing potential female customers should clarify why they don't find your shop appealing. It could be because of the products you sell or a need for greater brand awareness, among other possible reasons.

Launching or testing a new product

Suppose you are the product manager at a SaaS company looking to introduce a new product. Focus groups can be an excellent way to determine whether your product is marketable.

In this instance, you could hold a focus group with a sample group drawn from your intended audience. The group will explore the product based on its new features while you ensure adequate data on how users react to the new features. The data you collect will be key to making sales and marketing decisions.

Conducting studies to explain buyers' behaviors

You can also use qualitative research to understand existing buyer behavior better. Marketers analyze historical information linked to their businesses and industries to see when purchasers buy more.

Qualitative research can help you determine when to target new clients and peak seasons to boost sales by investigating the reason behind these behaviors.

- Qualitative research: data collection

Data collection is gathering information on predetermined variables to gain appropriate answers, test hypotheses, and analyze results. Researchers will collect non-numerical data for qualitative data collection to obtain detailed explanations and draw conclusions.