| — | From | | by Langston Hughes | Separate Is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of EducationThe U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education marked a turning point in the history of race relations in the United States. On May 17, 1954, the Court stripped away constitutional sanctions for segregation by race, and made equal opportunity in education the law of the land. Brown v. Board of Education reached the Supreme Court through the fearless efforts of lawyers, community activists, parents, and students. Their struggle to fulfill the American dream set in motion sweeping changes in American society, and redefined the nation’s ideals. The end of the Civil War had promised racial equality, but by 1900 new laws and old customs created a segregated society that condemned Americans of color to second-class citizenship. As African Americans and other minority groups began the struggle for civil rights, they strengthened their own schools and fought against segregated education. Beginning in the 1930s, African American lawyers from Howard University law school and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People campaigned to dismantle constitutionally-sanctioned segregation. In the early 1950s, African Americans from five different communities across the country bravely turned to the courts to demand better educational opportunities for their children. In 1954, under the leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Supreme Court produced a unanimous decision to overturn Plessy vs. Ferguson and changed the course of American history. Today, thanks in part to the victorious struggle in the Brown case, most Americans believe that a racially integrated, ethnically diverse society and educational system is a worthy goal, though they may disagree deeply about how to achieve it. Brown v. Board of Education (1954)Primary tabs. Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down the “Separate but Equal” doctrine and outlawed the ongoing segregation in schools. The court ruled that laws mandating and enforcing racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools were “separate but equal” in standards. The Supreme Court’s decision was unanimous and felt that " separate educational facilities are inherently unequal ," and hence a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution . Nonetheless, since the ruling did not list or specify a particular method or way of how to proceed in ending racial segregation in schools, the Court's ruling i n Brown II (1955) demanded states to desegregate “ with all deliberate speed .” Background :The events relevant to this specific case first occurred in 1951, when a public school district in Topeka, Kansas refused to let Oliver Brown’s daughter enroll at the nearest school to their home and instead required her to enroll at a school further away. Oliver Brown and his daughter were black. The Brown family, along with twelve other local black families in similar circumstances, filed a class action lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education in a federal court arguing that the segregation policy of forcing black students to attend separate schools was unconstitutional. However, the U.S. District Court for the District of Kansas ruled against the Browns, justifying their decision on judicial precedent of the Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson , which ruled that racial segregation did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment 's Equal Protection Clause as long as the facilities and situations were equal, hence the doctrine known as " separate but equal ." After this decision from the District Court in Kansas, the Browns, who were represented by the then NAACP chief counsel Thurgood Marshall, appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court's ruling in Brown overruled Plessy v. Ferguson by holding that the "separate but equal" doctrine was unconstitutional for American educational facilities and public schools. This decision led to more integration in other areas and was seen as major victory for the Civil Rights Movement. Many future litigation cases used the similar argumentation methods used by Marshall in this case. While this was seen as a landmark decision, many in the American Deep South were uncomfortable with this decision. Various Southern politicians tried to actively resist or delay attempts to desegregated their schools. These collective efforts were known as the “ Massive Resistance ,” which was started by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd. Thus, in just four years after the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Supreme Court affirmed its ruling again in the case of Cooper v. Aaron , holding that government officials had no power to ignore the ruling or to frustrate and delay desegregation. See also: Oyez - Brown Revisited [Last updated in August of 2024 by the Wex Definitions Team ] - ACADEMIC TOPICS

- legal history

- civil rights

- education law

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- legal practice/ethics

- constitutional law

- group rights

- legal education and practice

- wex articles

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

- Background and case

- What is the significance of Brown v. Board of Education ?

- What was the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education ?

- When did the American civil rights movement start?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article. - Constitution Center - Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- United States Court - History - Brown v. Board of Education Re-enactment

- National Archives - Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

- Ohio State University - Origins - The Long-Term Legacies of Brown v. Board

- Public Broadcasting Service - American Experience - Brown v. Board of Education

- BlackPast - Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

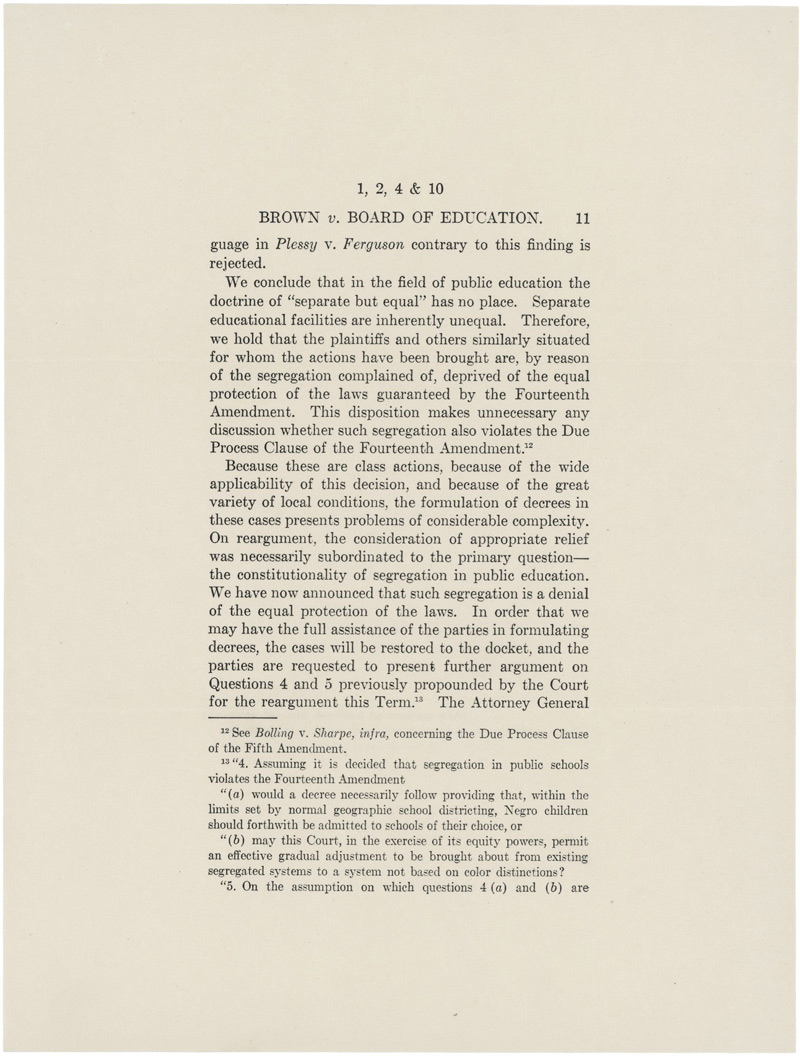

Writing for the court, Chief Justice Earl Warren argued that the question of whether racially segregated public schools were inherently unequal, and thus beyond the scope of the separate but equal doctrine, could be answered only by considering “the effect of segregation itself on public education.” Citing the Supreme Court’s rulings in Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education (1950), which recognized “intangible” inequalities between African American and all-white schools at the graduate level, Warren held that such inequalities also existed between the schools in the case before him, despite their equality with respect to “tangible” factors such as buildings and curricula. Specifically, he agreed with a finding of the Kansas district court that the policy of forcing African American children to attend separate schools solely because of their race created in them a feeling of inferiority that undermined their motivation to learn and deprived them of educational opportunities they would enjoy in racially integrated schools. This finding, he noted, was “amply supported” by contemporary psychological research. He concluded that “in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” In Bolling v. Sharpe he stated that racial segregation of schools violated due process of law, and, in a reference to the Brown ruling, noted that “it would be unthinkable that the same Constitution [which prohibits racially segregated schools] would impose a lesser duty on the Federal Government.” In a subsequent opinion on the question of relief, commonly referred to as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (II) , argued April 11–14, 1955, and decided on May 31 of that year, Warren ordered the district courts and local school authorities to take appropriate steps to integrate public schools in their jurisdictions “with all deliberate speed.” This failure to set time limits helped set the stage for years of conflicts over public school desegregation and other discriminatory practices.  Southern states largely opposed desegregation, and efforts to integrate were often highly contentious . Notably, violent protests erupted when African American teenagers (known as the Little Rock Nine ) attempted to attend a white high school in Little Rock , Arkansas , in 1957–58. Barred from entering, they were admitted only after U.S. Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower sent in U.S. troops and took command of the state’s National Guard. Arkansas’s governor responded by closing all of Little Rock’s public high schools in 1958–59. Other Southern cities followed suit, often implementing “school-choice” programs that subsidized white students’ attendance at private segregated academies, which were not covered by the Brown ruling. As a result, many Southern schools remained almost completely segregated until the late 1960s. Brown v. Board of Education is considered a milestone in American civil rights history. The case—and the efforts to undermine the decision—brought greater awareness to racial inequalities and the struggles African Americans faced. The success of Brown galvanized civil rights activists and increased efforts to end institutionalized racism throughout American society. - Name Search

- Browse Legal Issues

- Browse Law Firms

Brown v. Board of Education Case SummaryBy Joseph Fawbush, Esq. | Legally reviewed by Ally Marshall, Esq. | Last reviewed May 12, 2020 Legally ReviewedThis article has been written and reviewed for legal accuracy, clarity, and style by FindLaw’s team of legal writers and attorneys and in accordance with our editorial standards . Fact-CheckedThe last updated date refers to the last time this article was reviewed by FindLaw or one of our contributing authors . We make every effort to keep our articles updated. For information regarding a specific legal issue affecting you, please contact an attorney in your area . Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka is one of the most celebrated decisions in U.S. Supreme Court history. Its main holding that segregated schools are inherently unequal (and therefore unconstitutional) was both an important legal precedent and a decision with a huge social impact. Background and Facts of the CaseThe case was the culmination of decades of work by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall, of the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund, had worked to integrate schools through the courts since the 1930s. Thurgood Marshall, who went on to become the first black Supreme Court justice, argued the case on behalf of the NAACP and the plaintiffs. They argued that keeping black students separate from white students violated the equal protection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown v. Board of Education was a consolidated case, meaning that several related cases were combined to be heard before the Supreme Court. The NAACP had helped families in Delaware, South Carolina, Washington, D.C., and Kansas challenge the constitutionality of all-white schools. The representative plaintiff in the case was Oliver Brown, a pastor in Topeka, Kansas. He tried to enroll his daughter in a white school that was closer to the Brown's home. The school board refused. The NAACP chose the Brown family because they perceived them to be the most sympathetic plaintiff. That is why the case is called Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, even though the case involved plaintiffs in multiple states. Most simply refer to it as Brown v. Board . The Supreme Court took the relatively unusual step in Brown v. Board of hearing oral arguments twice, once in 1953 and again in 1954. The second round of oral arguments was almost entirely about the circumstances of the Fourteenth Amendment's passage and its intended effect on public education. The Fourteenth AmendmentA full understanding of the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board requires some background knowledge of the Fourteenth Amendment , as well as cases interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment in the context of school integration up to that point. The states ratified the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It was one of three Reconstruction-era Amendments passed to give civil and legal rights to black citizens and former slaves after the Civil War. Part of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." These are the due process and equal protection clauses, respectively. Plessy v. Ferguson and the Separate but Equal DoctrineIf black Americans were entitled to equal protection of the laws since 1868, how was school segregation legal? In Plessy v. Ferguson , decided in 1896, the Supreme Court held that laws keeping black and other minority populations apart from the white population did not violate the equal protection clause, provided minorities had equivalent facilities and services. This became known as the “separate but equal" doctrine, and it was the law throughout the first half of the 20 th century. It meant that there could be "whites only" drinking fountains, for example, provided that there was also a drinking fountain nearby for minorities. Fighting Back Against PlessyBy the time the Supreme Court decided Brown in 1954, courts had already begun to chip away at the main holding in Plessy . Even as early as 1938, the Supreme Court held in Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada that if a state offers a legal education, it must be offered to students of any race. That means if there is only one law school, for example, then that law school must admit black students. Most notably, in 1950, the Supreme Court held in McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education that a graduate school could not force a black student to sit alone in class, at the library, and in the cafeteria. That holding did not explicitly invalidate Plessy , however. The Lower Courts' DecisionsDespite a few cases on their side, the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board were fighting against a significant history of laws and court decisions promoting segregation. This was the predominant reason why the plaintiffs lost in lower courts. For example, in Kansas the lower court agreed with the plaintiffs that segregation harmed black children. However, the district court held that black schools had equivalent facilities and teachers, and so white schools could continue to refuse admittance to black students. In other words, the district court did not invalidate Plessy v. Ferguson . In Delaware, the district court did not invalidate Plessy either, but still held that white schools had to accept black students because black schools in the state were of lower quality. It would take the Supreme Court to overturn its own precedent set in Plessy . That is exactly what the NAACP and the families in Brown were arguing for in 1954. As it turned out, they had a Supreme Court that was receptive to their arguments. The Warren CourtChief Justice Earl Warren presided over the Supreme Court in 1954. President Eisenhower had appointed Justice Warren to the bench in 1953, so the Chief Justice was relatively new to the position at the time Brown was decided. However, as a two-term governor of California and a vice presidential running mate, he was no stranger to the public eye. While Brown remains one of the Warren Court's most prominent decisions, it was by no means the only significant civil rights case the court decided. The Warren Court is responsible for the Miranda warning and the one person, one vote rule, to give just two examples. The Decision in BrownIt was Chief Justice Warren, writing for a unanimous court, who penned the famous line that “in the field of public education the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place." The court explicitly overturned Plessy , finding that segregation in schools violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The school board had argued that at the time it was enacted, the states that ratified the Fourteenth Amendment did not intend for it to prohibit school segregation. This is what's known as an "originalist" reading of the Constitution. The Warren Court, despite asking at length about the history and circumstances of the Fourteenth Amendment, ultimately did not use an originalist reading of the Constitution in its decision. Instead, Justice Warren calls an examination of the history of the Fourteenth Amendment “at best, inconclusive" regarding the Amendment's intended effect on public schools. “We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation," the Chief Justice wrote. And segregated schools, the Supreme Court justices agreed, affected the hearts and minds of black children “in a way unlikely ever to be undone." Because segregated schools were inherently unequal, there could be no such thing as "separate but equal" and Plessy was finally overturned. What the Brown Decision Did Not DoThe court, having held that segregated schools violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, did not examine whether it also violated the due process clause. And while impactful, the decision in Brown was not as expansive as it might at first appear. The decision did not declare all segregated public facilities to be unconstitutional. Its holding was limited to schools. Nor did the court give a date for schools to comply with the decision. The rather limited holding also meant that the Supreme Court needed to issue a subsequent decision on school integration just a year later. In 1955, the Warren Court again took up school integration in a case now known as Brown II . In that decision, the Warren Court left it up to the states to determine when and how to integrate schools, provided they did so “with all deliberate speed." This vague direction led to many states and school districts dragging their feet to integrate schools. School integration did not begin for many black children until the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and integration and racial inequality in schools remain much-discussed issues to this day. Brown v. Board's Lasting ImpactFew people now question whether the Warren Court reached the right decision in Brown. However, the underlying legal argument - whether an “originalist" reading of the Constitution should be used to decide current social issues of national importance, or whether the court should take into account current-day circumstances and thought – remains controversial. Still, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka is an important case, and not just for ending segregation in education. It was used as precedent to overturn other laws mandating or permitting segregation. And while racial inequality in America's schools continues, Brown v. Board helped to spark the civil rights movement, and began a long journey toward a more equal educational system in America. Read the full decision on FindLaw.  More On SCOTUSLearn about the nation's highest court and its most famous decisions. Read more > Helpful Links- U.S. Constitution

- U.S. Federal Court System

- Law Students

Popular Directory Searches- Constitutional Law

- Civil Rights

- Discrimination

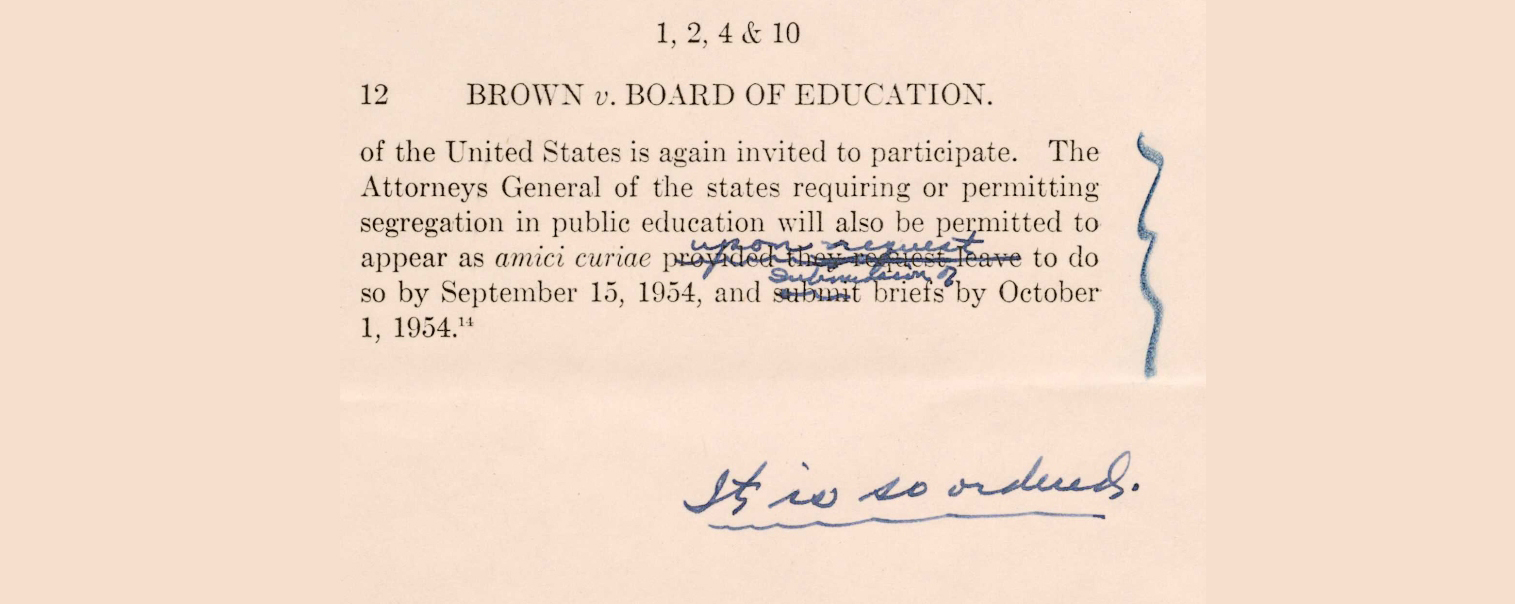

Thank you for subscribing! FindLaw Newsletters Stay up-to-date with FindLaw's newsletter for legal professionalsThe email address cannot be subscribed. Please try again. Learn more about FindLaw’s newsletters, including our terms of use and privacy policy. Brown v. Board of Education: AnnotatedThe 1954 Supreme Court decision, based on the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, declared that “separate but equal” has no place in education.  The US Supreme Court’s decision in the case known colloquially as Brown v. Board of Education found that the “[t]he ‘separate but equal ’ doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education.” The Plessy case, decided in 1896, had found that the segregation laws which created “separate but equal” accommodations for Black Americans, specific to transportation but applicable generally, were not a violation of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Segregation in education had been challenged throughout the first half of the twentieth century, and rulings in a number coalesced to propel Brown to the level of the Supreme Court to address segregation in all public schools.  Weekly NewsletterGet your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday. Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message. Below is an annotation of the opinion, with relevant scholarship covering the legal, social and education history leading up to and after the decision. As always, the supporting research is free to read and download.  The red J indicates free access to the linked research on JSTOR . ____________________________________________________________________________  SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Brown v. Board of Education, 347 US 483 (1954) (USSC+) Argued December 9, 1952 Reargued December 8, 1953 Decided May 17, 1954 APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS* Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment —even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. (a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. (b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. (c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. (d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal. (e) The “separate but equal” doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537, has no place in the field of public education. (f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court. These cases come to us from the States of Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. They are premised on different facts and different local conditions, but a common legal question justifies their consideration together in this consolidated opinion. In each of the cases, minors of the Negro race, through their legal representatives, seek the aid of the courts in obtaining admission to the public schools of their community on a nonsegregated basis. In each instance, they had been denied admission to schools attended by white children under laws requiring or permitting segregation according to race. This segregation was alleged to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment. In each of the cases other than the Delaware case, a three-judge federal district court denied relief to the plaintiffs on the so-called “separate but equal” doctrine announced by this Court in Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 US 537 . Under that doctrine, equality of treatment is accorded when the races are provided substantially equal facilities, even though these facilities be separate. In the Delaware case , the Supreme Court of Delaware adhered to that doctrine, but ordered that the plaintiffs be admitted to the white schools because of their superiority to the Negro schools. The plaintiffs contend that segregated public schools are not “equal” and cannot be made “equal,” and that hence they are deprived of the equal protection of the laws. Because of the obvious importance of the question presented, the Court took jurisdiction. Argument was heard in the 1952 Term, and reargument was heard this Term on certain questions propounded by the Court. Reargument was largely devoted to the circumstances surrounding the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It covered exhaustively consideration of the Amendment in Congress, ratification by the states, then-existing practices in racial segregation, and the views of proponents and opponents of the Amendment. This discussion and our own investigation convince us that, although these sources cast some light, it is not enough to resolve the problem with which we are faced. At best, they are inconclusive. The most avid proponents of the post-War Amendments undoubtedly intended them to remove all legal distinctions among “all persons born or naturalized in the United States.” Their opponents, just as certainly, were antagonistic to both the letter and the spirit of the Amendments and wished them to have the most limited effect. What others in Congress and the state legislatures had in mind cannot be determined with any degree of certainty. An additional reason for the inconclusive nature of the Amendment’s history with respect to segregated schools is the status of public education at that time. In the South, the movement toward free common schools, supported by general taxation, had not yet taken hold . Education of white children was largely in the hands of private groups. Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states. Today, in contrast, many Negroes have achieved outstanding success in the arts and sciences, as well as in the business and professional world. It is true that public school education at the time of the Amendment had advanced further in the North, but the effect of the Amendment on Northern States was generally ignored in the congressional debates. Even in the North, the conditions of public education did not approximate those existing today. The curriculum was usually rudimentary; ungraded schools were common in rural areas; the school term was but three months a year in many states, and compulsory school attendance was virtually unknown. As a consequence, it is not surprising that there should be so little in the history of the Fourteenth Amendment relating to its intended effect on public education. In the first cases in this Court construing the Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all state-imposed discriminations against the Negro race. The doctrine of “separate but equal” did not make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson , supra, involving not education but transportation. American courts have since labored with the doctrine for over half a century. In this Court, there have been six cases involving the “separate but equal” doctrine in the field of public education. In Cumming v. County Board of Education , 175 US 528 , and Gong Lum v. Rice , 275 US 78 , the validity of the doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white students were denied to Negro students of the same educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada , 305 US 337 ; Sipuel v. Oklahoma , 332 US 631; Sweatt v. Painter , 339 US 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , 339 US 637 . In none of these cases was it necessary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter , supra, the Court expressly reserved decision on the question whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inapplicable to public education. In the instant cases, that question is directly presented. Here, unlike Sweatt v. Painter , there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other “tangible” factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education. In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws. Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. It is required in the performance of our most basic public responsibilities, even service in the armed forces. It is the very foundation of good citizenship . Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race , even though the physical facilities and other “tangible” factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does. In Sweatt v. Painter , supra, in finding that a segregated law school for Negroes could not provide them equal educational opportunities, this Court relied in large part on “those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school.” In McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents , supra, the Court, in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate school be treated like all other students, again resorted to intangible considerations: “…his ability to study, to engage in discussions and exchange views with other students, and, in general, to learn his profession.” Such considerations apply with added force to children in grade and high schools. To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone. The effect of this separation on their educational opportunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to rule against the Negro plaintiffs: Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law , for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction of law, therefore, has a tendency to [retard] the educational and mental development of negro children and to deprive them of some of the benefits they would receive in a racial[ly] integrated school system . Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson , this finding is amply supported by modern authority. Any language in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected. We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal . Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Because these are class actions, because of the wide applicability of this decision, and because of the great variety of local conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases presents problems of considerable complexity . On reargument, the consideration of appropriate relief was necessarily subordinated to the primary question—the constitutionality of segregation in public education. We have now announced that such segregation is a denial of the equal protection of the laws. In order that we may have the full assistance of the parties in formulating decrees, the cases will be restored to the docket, and the parties are requested to present further argument on Questions 4 and 5 previously propounded by the Court for the reargument this Term The Attorney General of the United States is again invited to participate. The Attorneys General of the states requiring or permitting segregation in public education will also be permitted to appear as amici curiae upon request to do so by September 15, 1954, and submission of briefs by October 1, 1954. It is so ordered. * Together with No. 2, Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, argued December 9–10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953; No. 4, Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al. , on appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, argued December 10, 1952, reargued December 7–8, 1953, and No. 10, Gebhart et al. v. Belton et al. , on certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware, argued December 11, 1952, reargued December 9, 1953. [Transcript available from the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/brown-v-board-of-education ] Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.  JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR. Get Our NewsletterMore stories.  - A Selection of Student Confessions

- The Bawdy House Riots of 1668

Policing the Holocaust in ParisRecent posts. - Finding Caves on the Moon Is Great. On Mars? Even Better.

- Back to School

Support JSTOR DailySign up for our weekly newsletter. - Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits states from segregating public school students on the basis of race. This marked a reversal of the "separate but equal" doctrine from Plessy v. Ferguson that had permitted separate schools for white and colored children provided that the facilities were equal. Based on an 1879 law, the Board of Education in Topeka, Kansas operated separate elementary schools for white and African-American students in communities with more than 15,000 residents. The NAACP in Topeka sought to challenge this policy of segregation and recruited 13 Topeka parents to challenge the law on behalf of 20 children. In 1951, each of the families attempted to enroll the children in the school closest to them, which were schools designated for whites. Each child was refused admission and directed to the African-American schools, which were much further from where they lived. For example, Linda Brown, the daughter of the named plaintiff, could have attended a white school several blocks from her house but instead was required to walk some distance to a bus stop and then take the bus for a mile to an African-American school. Once the children had been refused admission to the schools designated for whites, the NAACP brought the lawsuit. They were unsuccessful at the trial court level, where the 1896 Supreme Court precedent in Plessy v. Ferguson was found to be decisive. Even though the trial court agreed that educational segregation had a negative effect on African-American children, it applied the standard of Plessy in finding that the white and African-American schools offered sufficiently equal quality of teachers, curricula, facilities, and transportation. Since the NAACP did not challenge the details of those findings, it essentially cast the appeal as a direct challenge to the system imposed by Plessy. When the Supreme Court heard the appeal, it combined Brown with four other cases addressing parallel issues in South Carolina, Virginia, Delaware, and Washington, D.C. The NAACP was responsible for bringing each of these lawsuits, and it had lost on each of them at the trial court level except the Delaware case of Gebhart v. Belton. Brown stood apart from the others in the group as the only case that challenged the separate but equal doctrine on its face. The others were based on assertions of gross inequality, which would have violated the standard in Plessy as well. - Earl Warren (Author)

- Hugo Lafayette Black

- Stanley Forman Reed

- Felix Frankfurter

- William Orville Douglas

- Robert Houghwout Jackson

- Harold Hitz Burton

- Tom C. Clark

- Sherman Minton

Supreme Court opinions are rarely unanimous, and it appears that Justice Frankfurter deliberately argued for a re-hearing to stall the case while the Court built a consensus behind its decision. This was designed to prevent proponents of segregation from using dissents to build future challenges to Brown. Despite the eventual unanimity, the judges had a wide range of views. Reed and Clark were not opposed to segregation per se, while Frankfurter and Jackson were hesitant to issue a bold decision that might be difficult to enforce. (Jackson and Reed initially planned to write a dissent together.) Douglas, Black, Burton, and Minton were relatively ready to overturn Plessy from the outset, however, as was Chief Justice Warren. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appointment of Warren to replace former Chief Justice Frederick Moore Vinson, who died in September 1953, thus may have played a crucial role in how events unfolded. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican-American children into California schools. Warren based much of his opinion on information from social science studies rather than court precedent. This was understandable because few decisions existed on which the Court could rely, yet it would draw criticism for its non-traditional approach. The decision also used language that was relatively accessible to non-lawyers because Warren felt that it was necessary for all Americans to understand its logic. This decision ranks among the most dramatic issued by the Supreme Court, in part due to Warren's insistence that the Fourteenth Amendment gave the Court the power to end segregation even without Congressional authority. Like the use of non-legal sources to justify his reasoning, Warren's "activist" view of the Court's role remains controversial to the current day. The illegality of segregation does not, however, and a series of later decisions were implemented to try to force states to comply with Brown. Unfortunately, the reality is that this decision's vision of complete desegregation has not been achieved in many areas of the U.S., and the problems of enforcement that Jackson identified have proven difficult to solve. U.S. Supreme CourtBrown v. Board of Education of Topeka Argued December 9, 1952 Reargued December 8, 1953 Decided May 17, 1954* Segregation of white and Negro children in the public schools of a State solely on the basis of race, pursuant to state laws permitting or requiring such segregation, denies to Negro children the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment -- even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors of white and Negro schools may be equal. Pp. 486-496. (a) The history of the Fourteenth Amendment is inconclusive as to its intended effect on public education. Pp. 489-490. (b) The question presented in these cases must be determined not on the basis of conditions existing when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted, but in the light of the full development of public education and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Pp. 492-493. (c) Where a State has undertaken to provide an opportunity for an education in its public schools, such an opportunity is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. P. 493. (d) Segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race deprives children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities, even though the physical facilities and other "tangible" factors may be equal. Pp. 493-494. (e) The "separate but equal" doctrine adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , has no place in the field of public education. P. 495. (f) The cases are restored to the docket for further argument on specified questions relating to the forms of the decrees. Pp. 495-496. - Opinions & Dissents

- Copy Citation

Get free summaries of new US Supreme Court opinions delivered to your inbox! - Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

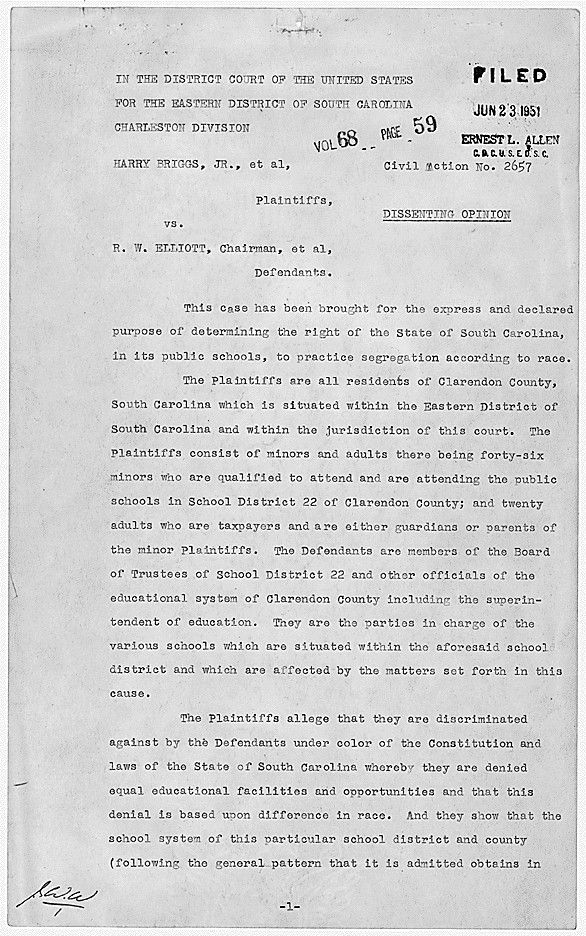

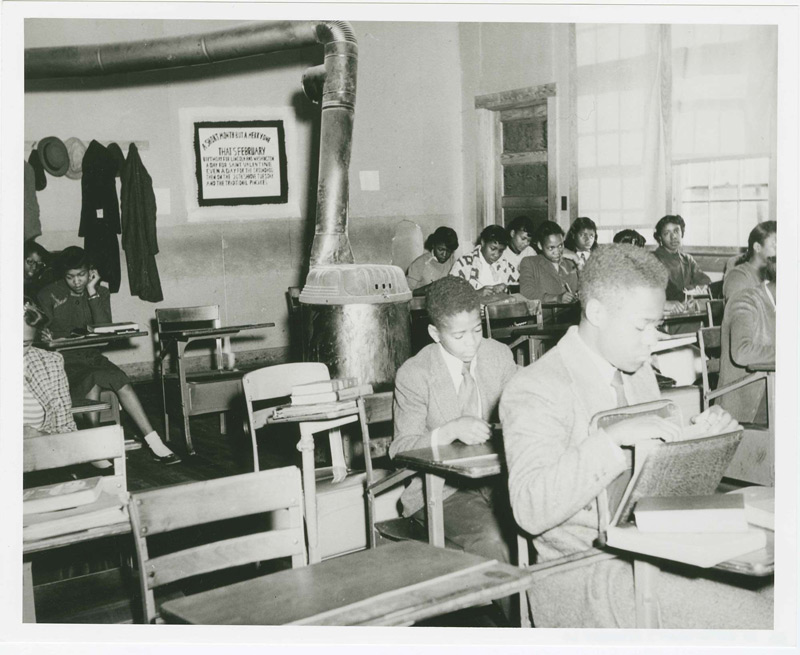

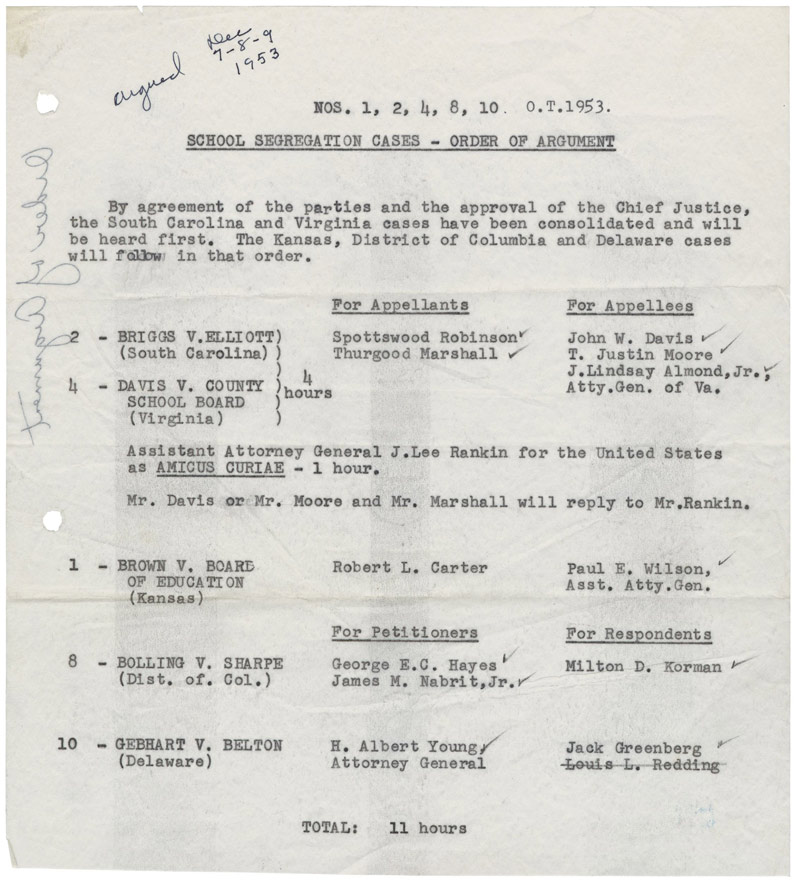

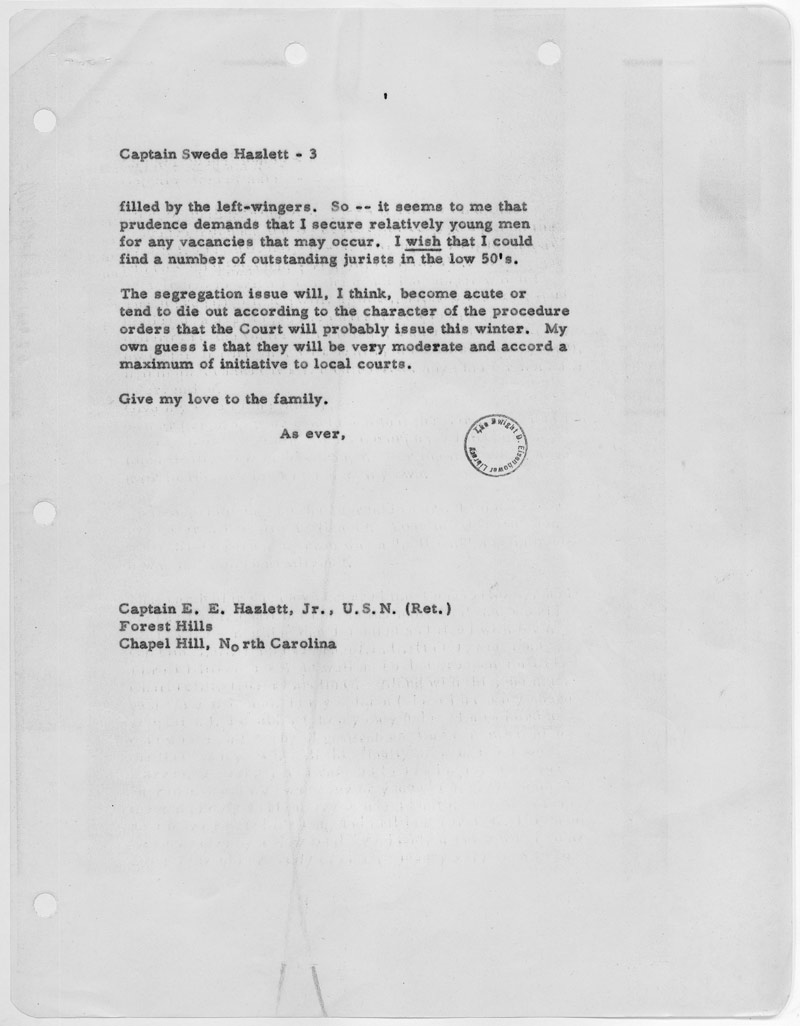

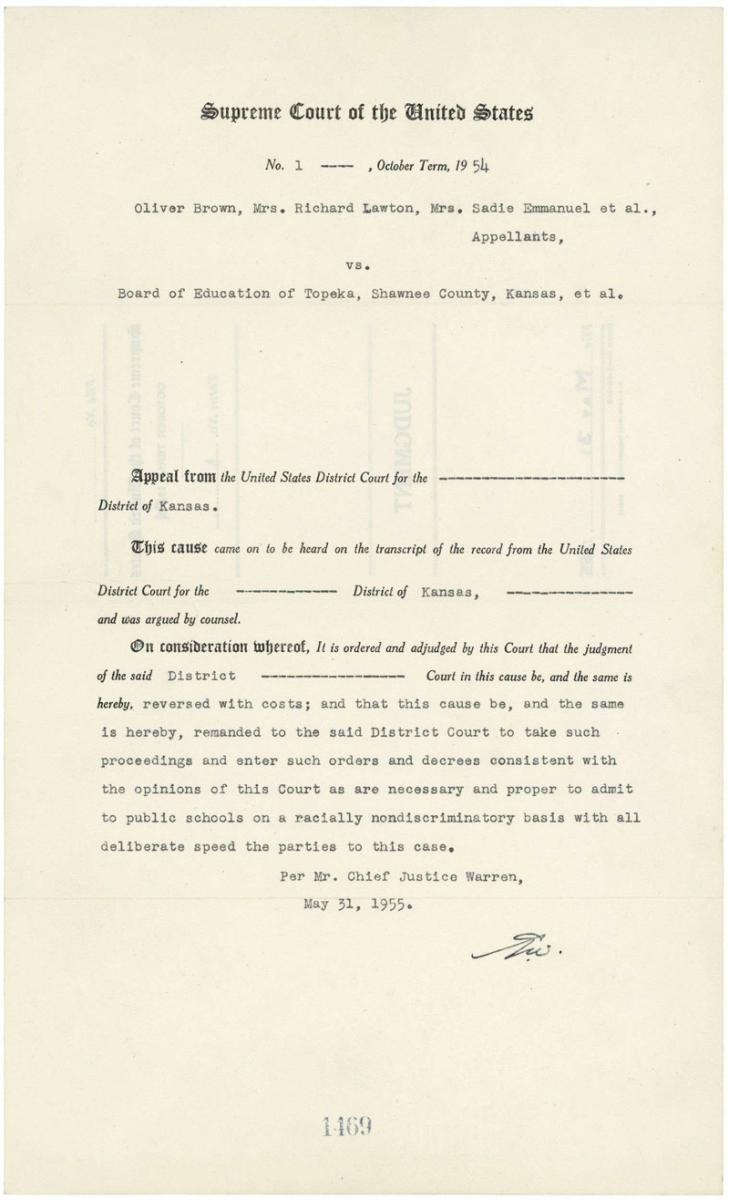

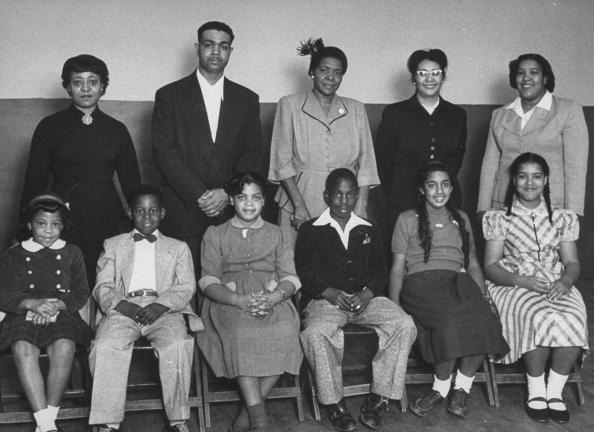

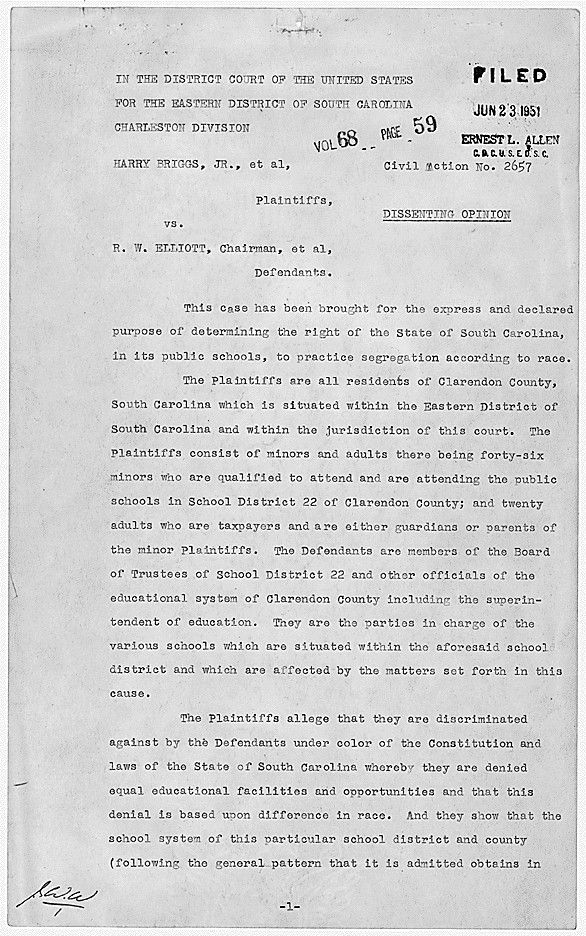

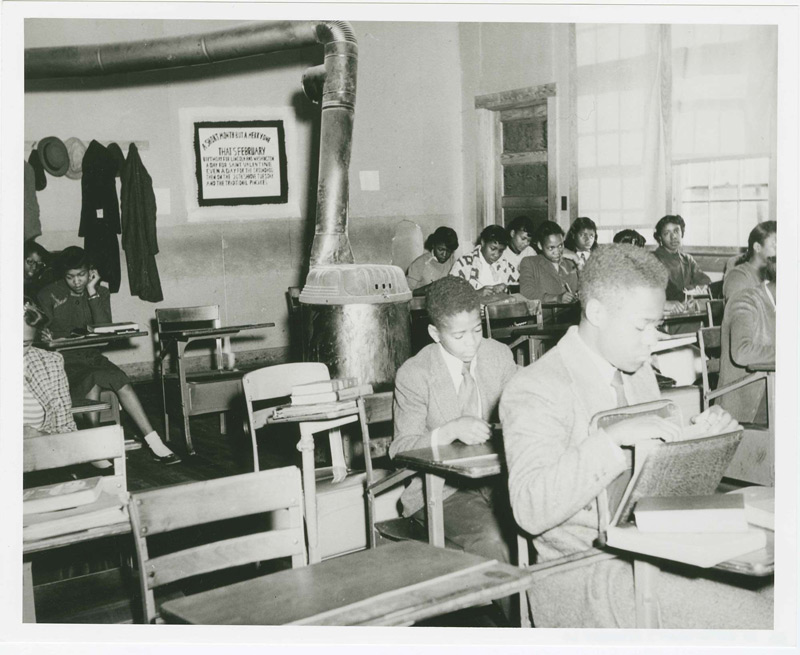

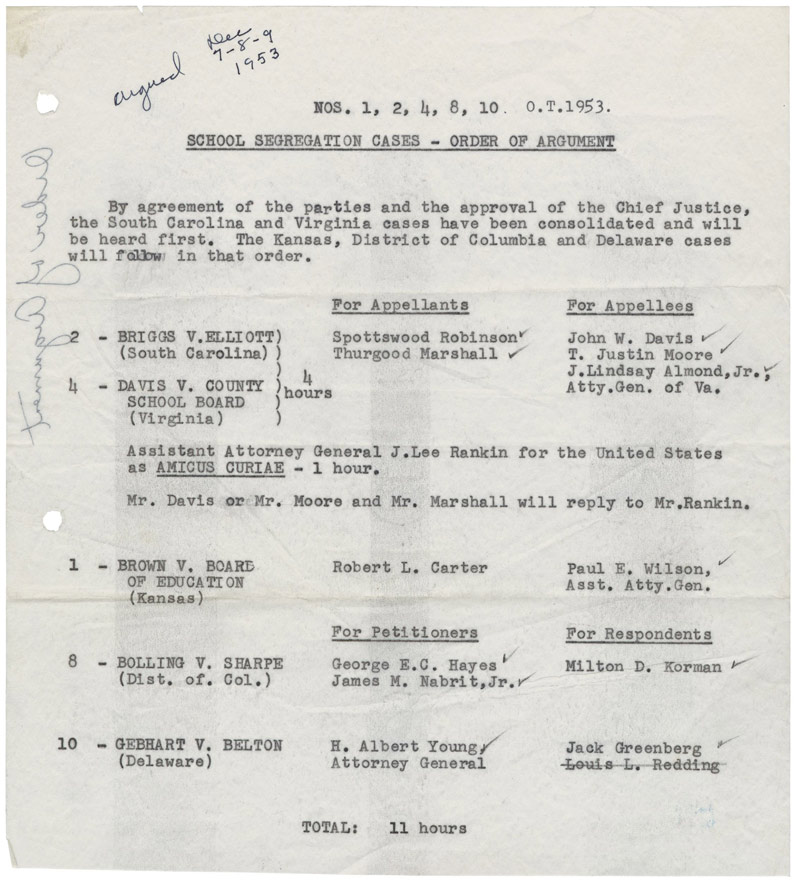

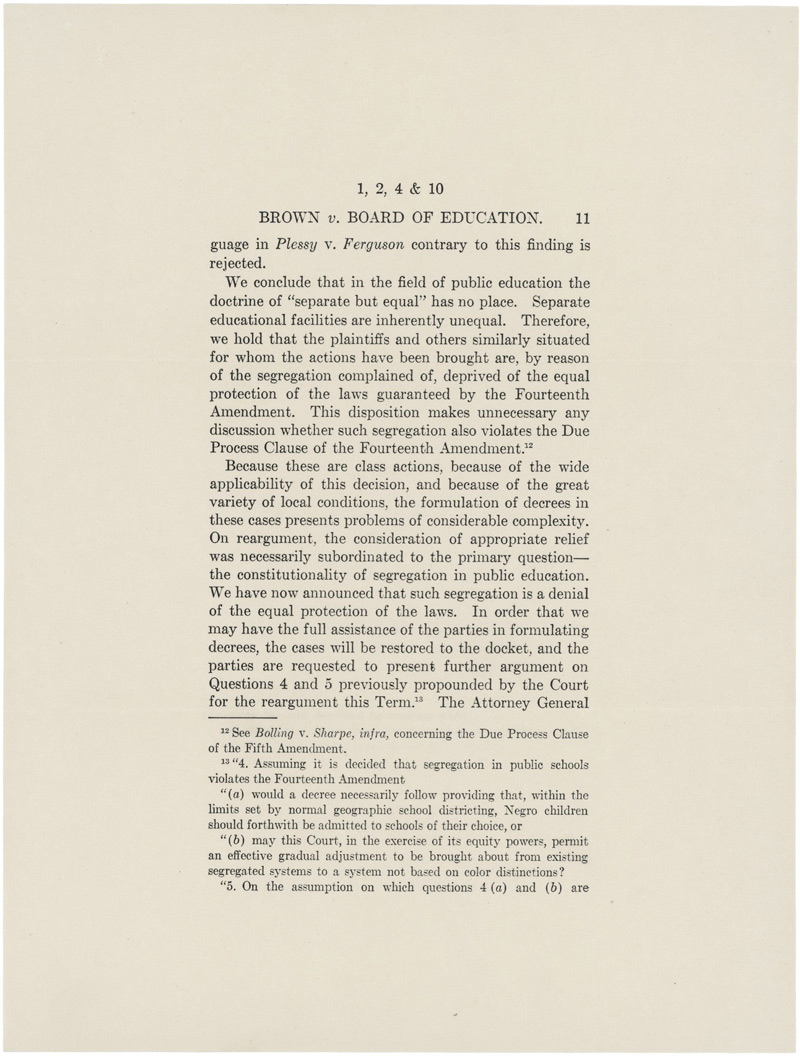

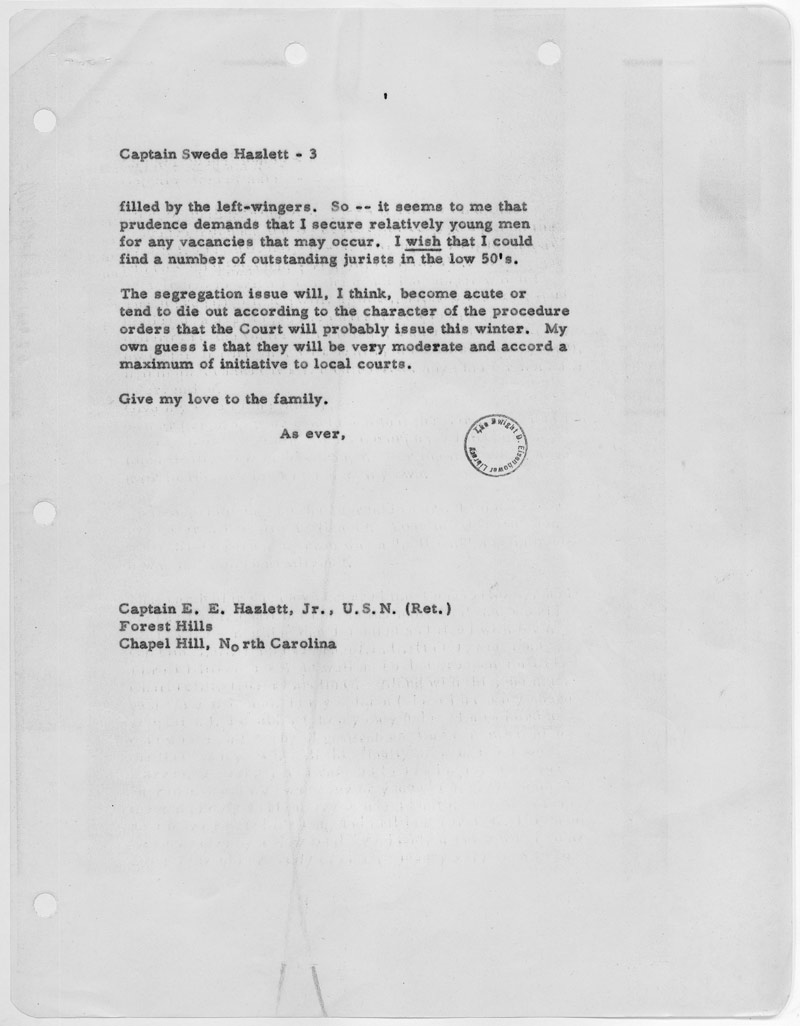

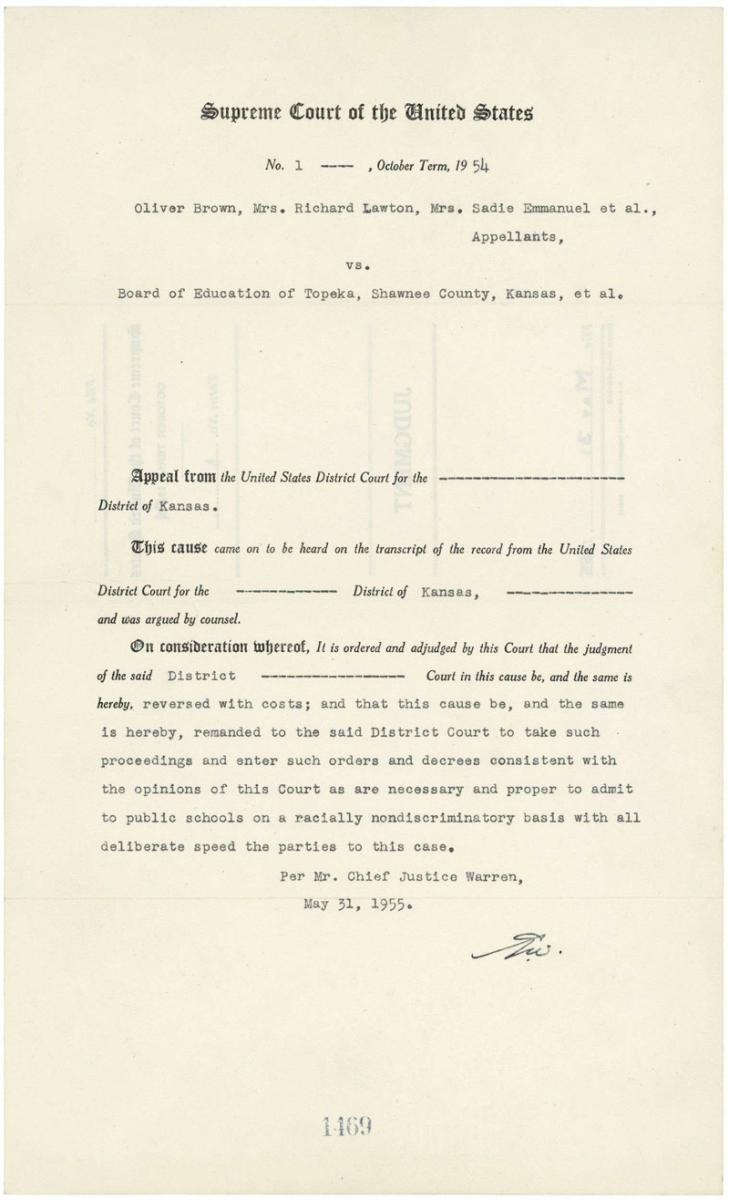

Some case metadata and case summaries were written with the help of AI, which can produce inaccuracies. You should read the full case before relying on it for legal research purposes. Brown v. Board of EducationThe case that transformed america. On May 17, 1954, a decision in the Brown v. Board of Education case declared the “separate but equal” doctrine unconstitutional. The landmark Brown v. Board decision gave LDF its most celebrated victory in a long, storied history of fighting for civil rights and marked a defining moment in US history. The decision in Brown v. Board remains a defining moment in U.S. history. The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education occurred after a hard-fought, multi-year campaign to persuade all nine justices to overturn the “separate but equal” doctrine that their predecessors had endorsed in the Court’s infamous 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. This campaign was conceived in the 1930s by Charles Hamilton Houston, then Dean of Howard Law School, and brilliantly executed in a series of cases over the next two decades by his star pupil, Thurgood Marshall–the man who became Legal Defense Fund’s first Director-Counsel and a Supreme Court Justice. Brown v. Board of Education itself was not a single case, but rather a coordinated group of five lawsuits against school districts in Kansas, South Carolina, Delaware, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. PHOTO: Students and their parents who initiated the landmark Civil Rights lawsuit 'Brown V Board of Education,' Topeka, Kansas, 1953, Pictured are, front row, from left, students, Vicki Henderson, Donald Henderson, Linda Brown James Emanuel, Nancy Todd, and Katherine Carper; back row, from left, parents Zelma Henderson, Oliver Brown, Sadie Emanuel, Lucinda Todd, and Lena Carper. (Photo by Carl Iwasaki/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images) To litigate these cases, Thurgood Marshall recruited the nation’s best attorneys , including Robert Carter, Jack Greenberg , Constance Baker Motley , Spottswood Robinson, Oliver Hill, Louis Redding, Charles and John Scott, Harold R. Boulware, James Nabrit, and George E.C. Hayes. These LDF lawyers were assisted by a brain trust of legal scholars, including future federal district court judges Louis Pollack and Jack Weinstein, along with William Coleman, the first Black person to serve as a Supreme Court law clerk. Their argument was clear: The 14th Amendment to the Constitution guarantees equal protection of the laws, and racial segregation violates that principle. The lawyers marshalled expert witnesses to prove what most of us take for granted today, that state-enforced racial segregation in education “deprives [Black children] of equal status in the school community…destroys their self-respect, denies them full opportunity for democratic social development [and]…stamps [them] with a badge of inferiority.” LDF relied upon research by historians like John Hope Franklin, and the work of social science researchers like June Shagaloff. Ms. Shagaloff was brought on staff by Marshall because he felt that chronicling the impact of segregation on children and families was critical to the success of LDF’s litigation. Her historical and social science research played a key role in LDF’s preparation for the successful Brown v. Board arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court. Psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark’s now-famous doll experiments were also central to LDF’s success in Brown v. Board. The experiments demonstrated the impact of segregation on black children. In presenting three to seven-year-old children with four dolls, identical except for color, Clark found Black children were led to believe that Black dolls were inferior to white dolls and, by extension, that they were inferior to their white peers. The Supreme Court cited Clark’s 1950 paper in its Brown decision and acknowledged it implicitly in the following passage: “To separate [African-American children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.” The Doll TestIn the 1940s, pioneering psychologists Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark designed and conducted a series of experiments known as “the doll tests” to study the psychological effects of segregation on Black children. After the five cases were heard together by the Court in December 1952, the outcome remained uncertain. The Court ordered the parties to answer a series of questions about the specific intent of the congressmen and senators who framed the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and about the Court’s power to dismantle segregation. The Court then scheduled another oral argument in December 1953. Wrapping up his presentation to the Court in that second hearing, Marshall emphasized that segregation was rooted in the desire to keep “the people who were formerly in slavery as near to that stage as is possible.” Even with powerful arguments from Marshall and other LDF attorneys, it took another five months for the newly appointed Chief Justice Earl Warren’s behind-the-scenes lobbying to yield a unanimous decision. Recognizing the controversial nature of its decision, the Court waited another year to issue an order enforcing the decision in Brown II . Even then, the Court was unwilling to establish a firm timetable for dismantling segregation. It ruled only that public schools desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” LDF Clients and Lawyers Risked Their Lives for this FightBlack women and girls were the voices behind the school desegregation movement since the beginning, but have often been relegated to the footnotes of history. in the kansas case that became brown v. board, all but one of the plaintiffs were women. black women and girls bravely took action to transform the american educational system and bring an end to segregation. Unfortunately, desegregation was neither deliberate nor speedy. In the face of fierce and often violent “ massive resistance ,” LDF sued hundreds of school districts across the country to vindicate the promise of Brown . It was not until LDF’s subsequent victories in Green v. County School Board (1968) and Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971) that the Supreme Court issued mandates that segregation be dismantled “root and branch,” outlined specific factors to be considered to eliminate effects of segregation, and ensured that federal district courts had the authority to do so. Even today, the work of Brown is far from finished . Over 200 school desegregation cases remain open on federal court dockets; LDF alone has nearly 100 of these cases. The legal victory in Brown did not transform the country overnight, and much work remains. But striking down segregation in the nation’s public schools provided a major catalyst for the civil rights movement, making possible advances in desegregating housing, public accommodations, and institutions of higher education. The decision gave hope to millions of Americans by permanently discrediting the legal rationale underpinning the racial caste system that had been endorsed or accepted by governments at all levels since the end of the nineteenth century. And its impact has been felt by every American. Learn More About Brown v. BoardThe women and girls who shaped brown v. board of education. The Girls who Shaped Brown v. Board of Education Their Untold Stories and the Sacrifices that Made Today’s Fight for Educational Equity Possible By Cara The Southern Manifesto and “Massive Resistance” to Brown The Case that Changed America Brown v. Board of Education The Southern Manifesto and “Massive Resistance” to Brown Learn More About Brown v. Board Almost The Significance of “The Doll Test”A Revealing Experiment Brown v. Board and “The Doll Test” Learn More About Brown v. Board Doctors Kenneth and Mamie Clark and “The Doll Test”  Six of the Women Behind Brown v. Board of EducationThe Case that Changed America Six of the Women Behind Brown v. Board of Education Learn More About Brown v. Board Throughout LDF’s history, women Meet the Legal Minds Behind Brown v. Board of EducationThe Case that Transformed America Brown v. Board of Education Meet the Legal Team The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education Brown v. Board of Education Reading ListThe Case that Changed America Brown v. Board of Education Reading list On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its unanimous decision in What Was Brown v. Board of Education? May 17, 1954, marks a defining moment in the history of the United States. On that day, the Copy short linkEducator Resources  Brown v. Board of EducationThe Supreme Court's opinion in the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954 legally ended decades of racial segregation in America's public schools. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement. Read more... Primary SourcesLinks go to DocsTeach , the online tool for teaching with documents from the National Archives.  Dissenting opinion in Briggs v. Elliott in which Judge Waties Waring opposed the District Court ruling that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment – he presented arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas , 6/21/1951 View in National Archives Catalog  English class at Moton High School , a school for Black students, one of several photographs entered as evidence in the case Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia , which was one of five cases that the Supreme Court consolidated under Brown v. Board of Education , ca. 1951  Order of Argument in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka during which attorneys reargued the five cases that the Supreme Court heard collectively and consolidated under the name Brown v. Board of Education , 12/1953  Page 11 of the unanimous Supreme Court ruling of 5/17/1954 in Brown v. Board of Education that state-sanctioned segregation of public schools violated the 14th Amendment, marking the end of the "separate but equal" precedent  Page 3 of a letter from President Eisenhower to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett in which the President expressed his belief that the new Warren court would be very moderate on the issue of segregation, 10/23/1954  Judgment of May 31, 1955, in Brown v. Board of Education (Brown II) – a year after the ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional – directing that schools be desegregated "with all deliberate speed" - Brown v. Board of Education Timeline

- Biographies of Key Figures

- Related Primary Sources: Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case

Teaching Activities The "Rights in America" page on DocsTeach includes primary sources and document-based teaching activities related to how individuals and groups have asserted their rights as Americans. It includes topics such as segregation, racism, citizenship, women's independence, immigration, and more. Additional Background InformationWhile the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution outlawed slavery, it wasn't until three years later, in 1868, that the 14th Amendment guaranteed the rights of citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including due process and equal protection of the laws. These two amendments, as well as the 15th Amendment protecting voting rights, were intended to eliminate the last remnants of slavery and to protect the citizenship of Black Americans. In 1875, Congress also passed the first Civil Rights Act, which held the "equality of all men before the law" and called for fines and penalties for anyone found denying patronage of public places, such as theaters and inns, on the basis of race. However, a reactionary Supreme Court reasoned that this act was beyond the scope of the 13th and 14th Amendments, as these amendments only concerned the actions of the government, not those of private citizens. With this ruling, the Supreme Court narrowed the field of legislation that could be supported by the Constitution and at the same time turned the tide against the civil rights movement. By the late 1800s, segregation laws became almost universal in the South where previous legislation and amendments were, for all practical purposes, ignored. The races were separated in schools, in restaurants, in restrooms, on public transportation, and even in voting and holding office. Plessy v. FergusonIn 1896, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson . Homer Plessy, a Black man from Louisiana, challenged the constitutionality of segregated railroad coaches, first in the state courts and then in the U. S. Supreme Court. The high court upheld the lower courts, noting that since the separate cars provided equal services, the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was not violated. Thus, the "separate but equal" doctrine became the constitutional basis for segregation. One dissenter on the Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan, declared the Constitution "color blind" and accurately predicted that this decision would become as baneful as the infamous Dred Scott decision of 1857. In 1909 the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was officially formed to champion the modern Civil Rights Movement. In its early years its primary goals were to eliminate lynching and to obtain fair trials for Black Americans. By the 1930s, however, the activities of the NAACP began focusing on the complete integration of American society. One of their strategies was to force admission of Black Americans into universities at the graduate level where establishing separate but equal facilities would be difficult and expensive for the states. At the forefront of this movement was Thurgood Marshall, a young Black lawyer who, in 1938, became general counsel for the NAACP's Legal Defense and Education Fund. Significant victories at this level included Gaines v. University of Missouri in 1938, Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma in 1948, and Sweatt v. Painter in 1950. In each of these cases, the goal of the NAACP defense team was to attack the "equal" standard so that the "separate" standard would in turn become susceptible. Five Cases Consolidated under Brown v. Board of EducationBy the 1950s, the NAACP was beginning to support challenges to segregation at the elementary school level. Five separate cases were filed in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Delaware: - Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, et al.

- Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R.W. Elliott, et al.

- Dorothy E. Davis et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, et al.

- Spottswood Thomas Bolling et al. v. C. Melvin Sharpe et al.

- Francis B. Gebhart et al. v. Ethel Louise Belton et al.

While each case had its unique elements, all were brought on the behalf of elementary school children, and all involved Black schools that were inferior to white schools. Most importantly, rather than just challenging the inferiority of the separate schools, each case claimed that the "separate but equal" ruling violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The lower courts ruled against the plaintiffs in each case, noting the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of the United States Supreme Court as precedent. In the case of Brown v. Board of Education , the Federal district court even cited the injurious effects of segregation on Black children, but held that "separate but equal" was still not a violation of the Constitution. It was clear to those involved that the only effective route to terminating segregation in public schools was going to be through the United States Supreme Court. In 1952 the Supreme Court agreed to hear all five cases collectively. This grouping was significant because it represented school segregation as a national issue, not just a southern one. Thurgood Marshall, one of the lead attorneys for the plaintiffs (he argued the Briggs case), and his fellow lawyers provided testimony from more than 30 social scientists affirming the deleterious effects of segregation on Black and white children. These arguments were similar to those alluded to in the Dissenting Opinion of Judge Waites Waring in Harry Briggs, Jr., et al. v. R. W. Elliott, Chairman, et al . (shown above). These [social scientists] testified as to their study and researches and their actual tests with children of varying ages and they showed that the humiliation and disgrace of being set aside and segregated as unfit to associate with others of different color had an evil and ineradicable effect upon the mental processes of our young which would remain with them and deform their view on life until and throughout their maturity....They showed beyond a doubt that the evils of segregation and color prejudice come from early training...it is difficult and nearly impossible to change and eradicate these early prejudices however strong may be the appeal to reason…if segregation is wrong then the place to stop it is in the first grade and not in graduate colleges. The lawyers for the school boards based their defense primarily on precedent, such as the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling, as well as on the importance of states' rights in matters relating to education. Realizing the significance of their decision and being divided among themselves, the Supreme Court took until June 1953 to decide they would rehear arguments for all five cases. The arguments were scheduled for the following term. The Court wanted briefs from both sides that would answer five questions, all having to do with the attorneys' opinions on whether or not Congress had segregation in public schools in mind when the 14th amendment was ratified. The Order of Argument (shown above) offers a window into the three days in December of 1953 during which the attorneys reargued the cases. The document lists the names of each case, the states from which they came, the order in which the Court heard them, the names of the attorneys for the appellants and appellees, the total time allotted for arguments, and the dates over which the arguments took place. Briggs v. ElliottThe first case listed, Briggs v. Elliott , originated in Clarendon County, South Carolina, in the fall of 1950. Harry Briggs was one of 20 plaintiffs who were charging that R.W. Elliott, as president of the Clarendon County School Board, violated their right to equal protection under the fourteenth amendment by upholding the county's segregated education law. Briggs featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs from some of the nation's leading child psychologists, such as Dr. Kenneth Clark, whose famous doll study concluded that segregation negatively affected the self-esteem and psyche of African-American children. Such testimony was groundbreaking because on only one other occasion in U.S. history had a plaintiff attempted to present such evidence before the Court. Thurgood Marshall, the noted NAACP attorney and future Supreme Court Justice, argued the Briggs case at the District and Federal Court levels. The U.S. District Court's three-judge panel ruled against the plaintiffs, with one judge dissenting, stating that "separate but equal" schools were not in violation of the 14th amendment. In his dissenting opinion (shown above), Judge Waties Waring presented some of the arguments that would later be used by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas . The case was appealed to the Supreme Court. Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, VirginiaMarshall also argued the Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, case at the Federal level. Originally filed in May of 1951 by plaintiff's attorneys Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, the Davis case, like the others, argued that Virginia's segregated schools were unconstitutional because they violated the equal protection clause of the fourteenth amendment. And like the Briggs case, Virginia's three-judge panel ruled against the 117 students who were identified as plaintiffs in the case. (For more on this case, see Photographs from the Dorothy Davis Case .) Brown v. Board of Education of TopekaListed third in the order of arguments, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was initially filed in February of 1951 by three Topeka area lawyers, assisted by the NAACP's Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg. As in the Briggs case, this case featured social science testimony on behalf of the plaintiffs that segregation had a harmful effect on the psychology of African-American children. While that testimony did not prevent the Topeka judges from ruling against the plaintiffs, the evidence from this case eventually found its way into the wording of the Supreme Court's May 17, 1954 opinion. The Court concluded that: To separate them [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone. Bolling v. SharpeBecause Washington, D.C., is a Federal territory governed by Congress and not a state, the Bolling v. Sharpe case was argued as a fifth amendment violation of "due process." The fourteenth amendment only mentions states, so this case could not be argued as a violation of "equal protection," as were the other cases. When a District of Columbia parent, Gardner Bishop, unsuccessfully attempted to get 11 African-American students admitted into a newly constructed white junior high school, he and the Consolidated Parents Group filed suit against C. Melvin Sharpe, president of the Board of Education of the District of Columbia. Charles Hamilton Houston, the NAACP's special counsel, former dean of the Howard University School of Law, and mentor to Thurgood Marshall, took up the Bolling case. With Houston's health already failing in 1950 when he filed suit, James Nabrit, Jr. replaced Houston as the original attorney. By the time the case reached the Supreme Court on appeal, George E.C. Hayes had been added as an attorney for the petitioners, beside James Nabrit, Jr. According to the Court, due to the decision in Plessy , "the plaintiffs and others similarly situated" had been "deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment," therefore, segregation of America's public schools was unconstitutional. Belton v. GebhartThe last case listed in the order of arguments, Belton v. Gebhart , was actually two nearly identical cases (the other being Bulah v. Gebhart ), both originating in the state of Delaware in 1952. Ethel Belton was one of the parents listed as plaintiffs in the case brought in Claymont, while Sarah Bulah brought suit in the town of Hockessin, Delaware. While both of these plaintiffs brought suit because their African-American children had to attend inferior schools, Sarah Bulah's situation was unique in that she was a white woman with an adopted Black child, who was still subject to the segregation laws of the state. Local attorney Louis Redding, Delaware's only African-American attorney at the time, originally argued both cases in Delaware's Court of Chancery. NAACP attorney Jack Greenberg assisted Redding. Belton/Bulah v. Gebhart was argued at the Federal level by Delaware's attorney general, H. Albert Young. Supreme Court Rehears ArgumentsReargument of the Brown v. Board of Education cases at the Federal level took place December 7-9, 1953. Throngs of spectators lined up outside the Supreme Court by sunrise on the morning of December 7, although arguments did not actually commence until one o'clock that afternoon. Spottswood Robinson began the argument for the appellants, and Thurgood Marshall followed him. Virginia's Assistant Attorney General, T. Justin Moore, followed Marshall, and then the court recessed for the evening. On the morning of December 8, Moore resumed his argument, followed by his colleague, J. Lindsay Almond, Virginia's Attorney General. Following this argument, Assistant United States Attorney General J. Lee Rankin, presented the U.S. government's amicus curiae brief on behalf of the appellants, which showed its support for desegregation in public education. In the afternoon, Robert Carter began arguments in the Kansas case, and Paul Wilson, Attorney General for the state of Kansas, followed him in rebuttal. On December 9, after James Nabrit and Milton Korman debated Bolling , and Louis Redding, Jack Greenberg, and Delaware's Attorney General, H. Albert Young argued Gebhart , the Court recessed. The attorneys, the plaintiffs, the defendants, and the nation waited five months and eight days to receive the unanimous opinion of Chief Justice Earl Warren's court, which declared, "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place." The Warren CourtIn September 1953, President Eisenhower had appointed Earl Warren, governor of California, as the new Supreme Court chief justice. Eisenhower believed Warren would follow a moderate course of action toward desegregation. His feelings regarding the appointment are detailed in the closing paragraphs of a letter he wrote to E. E. "Swede" Hazlett, a childhood friend (shown above). On the issue of segregation, Eisenhower believed that the new Warren court would "be very moderate and accord a maximum initiative to local courts." In his brief to the Warren Court that December, Thurgood Marshall described the separate but equal ruling as erroneous and called for an immediate reversal under the 14th Amendment. He argued that it allowed the government to prohibit any state action based on race, including segregation in public schools. The defense countered this interpretation pointing to several states that were practicing segregation at the time they ratified the 14th Amendment. Surely they would not have done so if they had believed the 14th Amendment applied to segregation laws. The U.S. Department of Justice also filed a brief; it was in favor of desegregation but asked for a gradual changeover. Over the next few months, the new chief justice worked to bring the splintered Court together. He knew that clear guidelines and gradual implementation were going to be important considerations, as the largest concern remaining among the justices was the racial unrest that would doubtless follow their ruling. The Supreme Court RulingFinally, on May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren read the unanimous opinion: school segregation by law was unconstitutional (shown above). Arguments were to be heard during the next term to determine exactly how the ruling would be imposed. Just over one year later, on May 31, 1955, Warren read the Court's unanimous decision, now referred to as Brown II (also shown above). It instructed states to begin desegregation plans "with all deliberate speed." Warren employed careful wording in order to ensure backing of the full Court in his official judgment. The Brown decision was a watershed in American legal and civil rights history because it overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine first articulated in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. By overturning Plessy , the Court ended America's 58-year-long practice of legal racial segregation and paved the way for the integration of America's public school systems. Despite two unanimous decisions and careful, if not vague, wording, there was considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education . In addition to the obvious disapproving segregationists were some constitutional scholars who felt that the decision went against legal tradition by relying heavily on data supplied by social scientists rather than precedent or established law. Supporters of judicial restraint believed the Court had overstepped its constitutional powers by essentially writing new law. However, minority groups and members of the Civil Rights Movement were buoyed by the Brown decision even without specific directions for implementation. Proponents of judicial activism believed the Supreme Court had appropriately used its position to adapt the basis of the Constitution to address new problems in new times. The Warren Court stayed this course for the next 15 years, deciding cases that significantly affected not only race relations, but also the administration of criminal justice, the operation of the political process, and the separation of church and state. Parts of this text were adapted from an article written by Mary Frances Greene, a teacher at Marie Murphy School in Wilmette, IL.  - History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault