Tourism Extension

- Destination Leadership Resources

Sustainable Tourism Case Studies

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

The Sustainable Tourism Case Studies Clearinghouse aims to provide examples of how the tourism industry is addressing a variety of challenges – from workforce housing to coastal degradation. NC State University students have designed these case studies to highlight solutions from tourism destinations across the United States and around the world, so community leaders and tourism stakeholders can adapt solutions to fit the unique challenges of their destination.

NC State students want to know what sustainable tourism challenges you are facing. Solutions to these challenges will be shared in the NC State Extension Sustainable Tourism Case Study Clearinghouse. Share the challenges you’d like solutions for HERE with a brief survey .

Photo: NC State University

Case Studies

- Voluntary Visitor Fee Programs (2024)

- Policies and Planning Strategies for Tourism Workforce Housing (2023)

- Use of Oyster Reefs to Reduce Coastal Degradation in Tourism Destination Communities (2023)

Current Student Researchers

The development of these case studies are supported with the NC State College of Natural Resource’s Lighthouse Fund for Sustainable Tourism.

Share this Article

- Blogs @Oregon State University

Oregon Sea Grant Sustainable Tourism

Http://seagrant.oregonstate.edu/tourism.

Sustainable Tourism Case Studies

Innovative and promising practices in sustainable tourism..

Innovative and promising practices in sustainable tourism. Edited by Nicole Vaugeous, Miles Phillips, Doug Arbogast and Patrick Brouder

The intent of this volume is to provide an opportunity for academics, extension professionals, industry stakeholders and community practitioners to reflect, discuss and share the innovative approaches that they have taken to develop sustainable tourism in a variety of different contexts. This volume includes nine cases from across North and Central America reaching from Hawaii in the west to New England in the east and from Quebec in the north to Costa Rica in the south. Case studies are a valuable way to synthesize and share lessons learned and they help to create new knowledge and enhanced applications in practice. There are two main audiences for this volume: 1) faculty and students in tourism related academic programs who will benefit from having access to current case studies that highlight how various stakeholders are approaching common issues, opportunities and trends in tourism, and 2) extension agents and practitioners who will gain important insights from the lessons learned in the current case study contexts. Volume 1 in its entirety: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16372 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8748

DESCRIPTION

Introduction…………………………..3

- Indigenous Tourism and Reconciliation: The Case of Kitcisakik Cultural Immersions……………….7

- Hawaii Ecotourism Association’s Sustainable Tour Certification Program: Promoting Best Practices to Conserve a Unique Place ……22

- Transdisciplinary University Engagement for Sustainable Tourism Planning…………………..38

- Expanding Agritourism In Butte County, California ………………..58

- Recreation Economies and Sustainable Tourism: Mountain Biking at Kingdom Trail Association in Vermont …………………..76

- Kentucky Trail Town Program: Facilitating communities capitalizing on adventure tourism for community and economic development…………….94

- Enhanced performance and visitor satisfaction in artisan businesses: A case study of the evaluation of the Économusée® model in British Columbia…112

- Reverse Osmosis: Cultural Sensitivity Training in the Costa Rican Luxury Ecolodge Setting………………….130

- Stakeholder Engagement and Collaborative Corridor Management: The Case of New Hampshire Route 1A/1B Byway Corridor ………..152

Volume 1 in its entirety: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16372 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8748

- Arellano et al.: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16677 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-9041

- Cox: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16676 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-9040

- Eades et al.: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16675 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-9039

- Hardesty et al.: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16616 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8982

- Kelsey et al.: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16614 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8981

- Koo: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16585 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8953

- Predyk & Vaugeois: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16584 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8952

- Nowaczek: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16530 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8900

- Robertson: https://viurrspace.ca/handle/10613/16529 ; DOI: 10.25316/IR-8899

Contact Info

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

21 Communities in Sustainable Tourism Development – Case Studies

From the book sustainable tourism dialogues in africa.

- Roniance Adhiambo and Leonard Akwany

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Chapters in this book (32)

- Get involved

A sustainable tourism model transforms economic development: the Egypt case study

Yomna Mohamed, Head of Experimentation

September 12, 2022

Egypt is a world-renowned touristic destination. Tell someone you are visiting Egypt, and the pictures immediately come into focus: the iconic pyramids of Giza, with the mysterious Sphinx standing guard; the beautiful beaches along the coast, warm and inviting; the vibrant and bustling bazaars, infused with the legacy of the pharaohs, teeming with the rich cultures of its people.

As the top destination for tourists visiting North Africa, how might Egypt evolve its tourism industry into a sustainable engine for economic development – particularly as the world emerges from the pandemic? More fundamentally, might tourism sector provide an opportunity to rethink the development model capable of withstanding & thriving in the context of interlinked, largely unpredictable and fast-moving crises – from food security and changing climate, to rapid inflation, polarization, economic downturn & inequality?

This is the critical question facing UNDP Egypt, one of nine country offices selected by UNDP’s Strategic Innovation Unit to join the second cohort of Deep Demonstrations, an initiative financed by the Government of Denmark.

In this post, we detail the context for tourism in Egypt, consider emerging trends in the economic model, and share progress to date in shaping broader system transformation.

The Egyptian Context

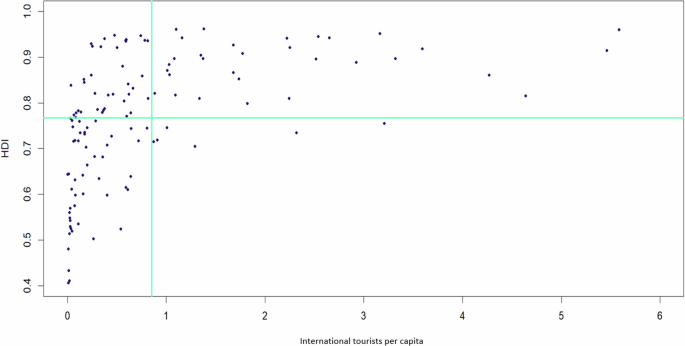

Egypt is best characterized as a Low-Cost Mass Tourism Magnet. According to the IMF , the tourism industry employed 10 percent of the population and contributed to about 12 percent of GDP pre-pandemic. Egypt ranks first in Africa, fifth in MENA, and 51 st globally in the travel and tourism development index (TTDI). It is a top performer in the MENA region with regards to environmental sustainability (31), natural and cultural resources (33), and business and cultural travel (22). With over 100 million in population, Egypt is both a prime destination for nature-based activities and a home to rich cultural diversity.

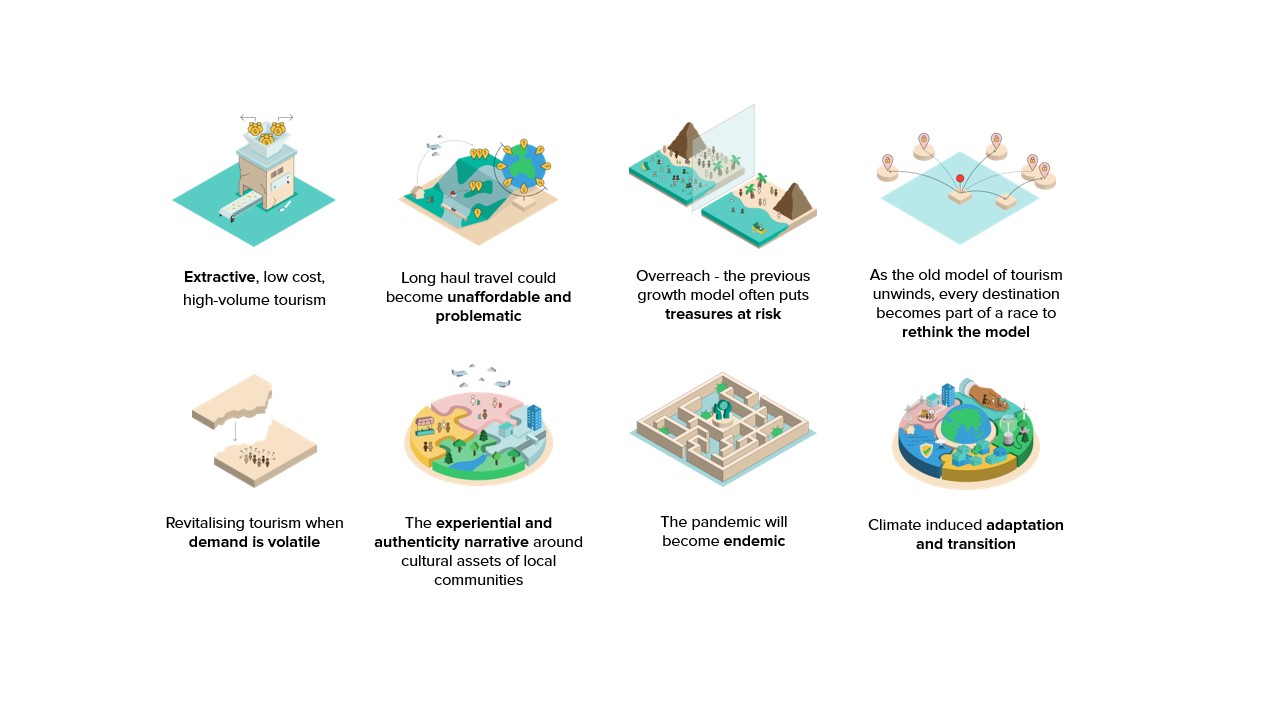

While the pandemic has definitely been an accelerant, the combination of economic factors and new norms that underpin global tourism raise fundamental questions about long-term viability (see fig 1). Even as the global airline industry recovers from the pandemic, the costs of long-haul travel have become increasingly unaffordable – not only in the rising price of fuel but also in its contributions to climate change. The unexpected benefits of lockdown, improved environments and ecosystems, have countries questioning whether they want to return to the risky, crowded, over-reaching pre-pandemic world. And COVID-19 has magnified the vulnerability of local communities who already do not benefit from unsustainable tourism.

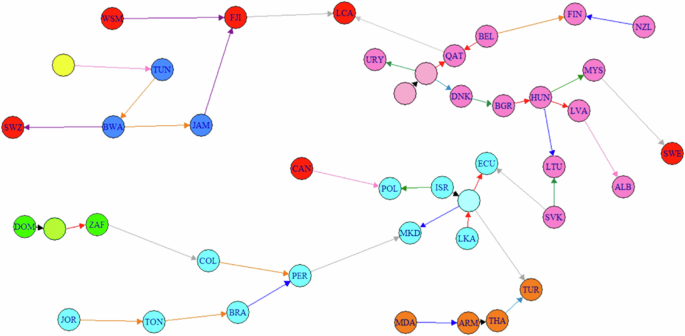

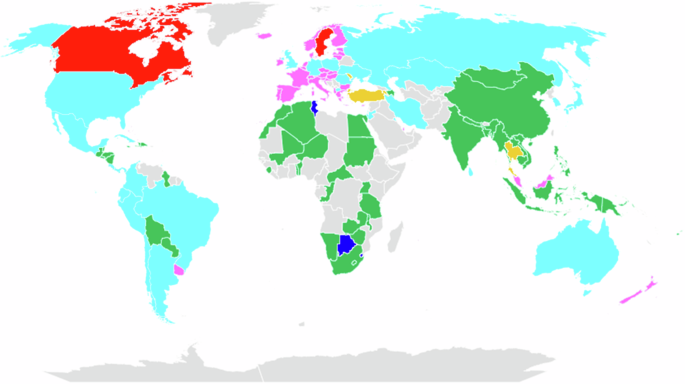

fig 1. Macro Trends, or the Opportunity Space for Change

This requires rethinking the model entirely. The circumstances call for collective effort that transforms the system to one based on sustainability, resilience, and putting local communities first.

Looking at the adjacent possible and entry points for unlocking systems transformation

In response, UNDP Egypt has embarked on a journey to rethink the tourism model and develop a portfolio of policy options on sustainable tourism that align with national priorities.

This approach relies not on a singular discrete intervention but a full system-wide transformation. The adaptive framework is designed to continuously learn from experience and detect new opportunities or needs in the system. A portfolio-based approach serves as a dynamic repository of strategic ideas that frame policy, an investment pipeline for funders, and a coordinating mechanism for relevant stakeholders.

In order to design this portfolio, it is necessary to start with strategic intent. This involves three specific actions –

1. Create a shared vision at the national level:

This frames the possibilities for a transformative agenda and mobilizes stakeholders to build sustainable, innovative tourism in Egypt. A critical mindset shift is seeing investment in the population and nature as an investment in tourism, where tourism becomes an entry point for rethinking the country’s existing development paradigms.

2. Reimagine a tourism industry that benefits all:

These include activities that strengthen climate resilience and deliver sustainable benefits to local communities at the forefront.

3. Expand the diversity of business models:

By focusing on innovative and integrated experiences for tourists, Egypt can accelerate and drive sustainable growth in the industry.

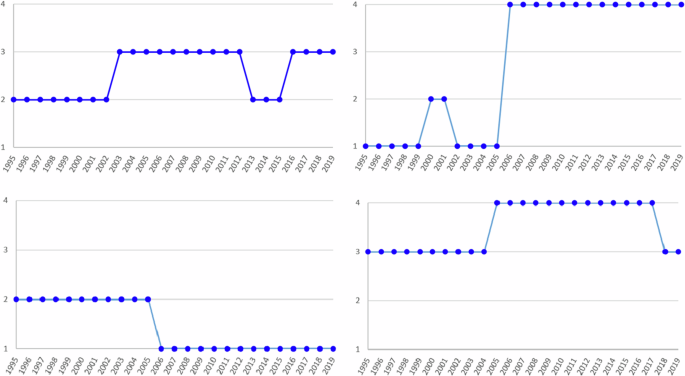

Informed by this strategic intent, existing models, and portfolio ambitions, we have identified three main shifts to create in conjunction with our partners and stakeholders, showcased in fig 2.

fig 2. Three Shifts in the Model

As innovation advisors, we have learned to trust the process. Through this system transformation framework, two parallel but complementary pathways have emerged –

1. Continuously exploring and deeply learning the needs and opportunities in the system; and

2. Identifying key policy options that accelerate the investment pipeline

We are taking these shifts and translating them into specific and coherent offers to be pursued with partners. A sample of these is shown in fig 3.

fig 3. Three Shifts, in Practice

A system transformation is premised on collective action and stakeholder engagement around a coherent approach. In this deep demonstration on sustainable tourism, we embarked on a journey to learn about the problem space, design a portfolio of policy options, and activate a set of evidence-based interventions.

We have yet to determine where best to introduce this portfolio of interventions, but we invite all potential partners to learn alongside and act with us as we work together to make tourism a sustainable economic engine in Egypt.

Tourism and Hospitality Trends and Sustainable Development: Emerging Issues in the Digital Era

- First Online: 28 August 2024

Cite this chapter

- Emmanuel Ndhlovu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2339-3068 4 ,

- Kaitano Dube ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7482-3945 4 &

- Catherine Muyama Kifworo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5581-2258 4

15 Accesses

This chapter introduces the book Tourism and Hospitality for Sustainable Development—Volume Two: Emerging Trends and Global Issues by summarising the key aspects covered by the chapters that make up the volume. This chapter argues that the emergence of new trends in the tourism industry and the pursuit of sustainable development have been accompanied by the advent of digital technology emerging from the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). There have been, however, concerns about the implications of novel technologies for pressing global concerns such as the environment, labour market, energy utilisation, and global poverty. However, studies that comprehensively problematise these aspects either do not exist or are still in their embryonic stages. As a result, our understanding of tourism and hospitality trends and sustainable development in the digitalisation era and the various issues accompanying the digitalisation wave remains limited. In seeking to close this gap, the chapters in this volume explore the trends and emerging issues in the global tourism and hospitality industry in the era of digitalisation. The current introductory chapter revisits some conceptual and practical debates on the usefulness of digitalisation in the industry. This is achieved by referring to various sources from grey and academic literature. This is meant to provide a background discussion of the chapters contained in the book. The chapter also outlines the sections and chapters in the book.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abdou, A. H., Hassan, T. H., & El Dief, M. M. (2020). A description of green hotel practices and their role in achieving sustainable development. Sustainability, 12 , 9624. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229624

Article Google Scholar

Abiola-Oke, E. (2020). Destination branding by the brand of hotel. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, 8 (3), 100–107.

Google Scholar

Abouzeid, N. (2022). The impact of digitalization on Tourism sustainability: Comparative study between selected developed and developing countries. In Second International Conference on Advanced Research on Management, Economics, and Accounting , 18–20 February 2022,

Ada, N., Kazancoglu, Y., Sezer, M. D., Ede-Senturk, C., Ozer, I., & Ram, M. (2021). Analyzing barriers of circular food supply chains and proposing industry 4.0 solutions. Sustainability, 13 , 6812. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126812

Aithal, P. S. (2021). Ideal technology and its realization. In P. S. In Aithal (Ed.), Ideal systems, ideal technology, and their realization opportunities using ICCT & Nanotechnology (pp. 83–216). Srinivas Publication.

Alalwan, A. A. (2020). Mobile food ordering apps: An empirical study of the factors affecting customer e-satisfaction and continued intention to reuse. International Journal of Information Management, 50 , 28–44.

Anggadwita, G., Luturlean, B. S., Ramadani, V., & Ratten, V. (2017). Socio-cultural environments and emerging economy entrepreneurship: Women entrepreneurs in Indonesia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9 (1), 85–96.

Antwi, C. O., Chong-jun, F., Ihnatushchenko, N., Aboagye, M. O., & Xu, H. (2020). Does the nature of airport terminal service activities matter? Processing and nonprocessing service quality, passenger affective image and satisfaction. Journal of Air Transport Management, 89 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101869

Arun, T. M., Kaur, P., Ferraris, A., & Dhir, A. (2021). What motivates the adoption of green restaurant products and services? A systematic review and future research agenda. Business Strategy and Environment , 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2755

Barykin, E. S., de la Poza, E., Khalid, B., Kapustina, I. V., Kalinina, O. V., & Iqbal, K. M. J. (2021). Tourism industry: Digital transformation. In Handbook of research on future opportunities for technology management education . IGI Publisher.

Bayram, A. (2021). Renting cars and trucks. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-7287-0.ch005

Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Our common future: Report of the world commission on environment and development . UN-Dokument A/42/427.

Brusiltseva, H., & Akhmedova, O. (2019). Transport service as a component of the tourism industry development of Ukraine. SHS Web of Conferences, 67 (02001), 1–6.

Budnyk, V., & Lernichenko, K. (2019). Urban passenger water transport: Operating within public-private partnership (international research and case study). Economic Annals-XXI, 178 (7–8), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.21003/ea.V178-07

Carnicelli, S., Drummond, S., & Anderson, H. (2020). Making the connection using action research: Serious leisure and the Caledonian Railway. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 16 , 615–631.

Chakamera, C., & Pisa, N. (2021). Relationship between air passenger transport, Tourism and real gross domestic product in Africa: A longitudinal mediation analysis. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 10 (4), 1200–1214.

Chowdhury, S., Åkesson, M., & Thomsen, M. (2021). Service innovation in digitalized product platforms: An illustration of the implications of generativity on remote diagnostics of public transport buses. Technology in Society, 65 , 101589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101589

Christou, P., Similidou, A., & Stylianou, M. C. (2020). Tourists’ perceptions regarding the use of anthropomorphic robots in tourism and hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32 (11), 3665–3683.

De Gasperi, A. (2021). Sustainable tourism development. Regional Formation and Development Studies, 3 (8), 157–166.

de la Feria, R., & Maffini, G. (2021). The impact of digitalisation on personal income taxes. British Tax Review, 2021 (2), 154–168.

Dragan, W., & Gierczak, D. (2020). Former border railway stations in central and Eastern Europe: Revitalization of a problematic cultural heritage in Poland. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 19 , 851–867.

Dube, K., & Mearns, K. (2019). Tourism and recreational potential of green building a case study of Hotel Verde Cape Town. In G. Nhamo & V. Mjimba (Eds.), The green building evolution (pp. 200–219). African Institute of South Africa.

Dube, K. (2022). South African hotels and hospitality industry response to climate change- induced water insecurity under the sustainable development goals banner. In Naddeo, V., Choo, K., & M. Ksibi (Eds.), Water-Energy-Nexus in the Ecological Transition. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation . p. 249–252. Springer Nature.

Durajczyk, P., & Drop, N. (2021). Possibilities of using inland navigation to improve efficiency of urban and interurban freight transport with the use of the river information services (RIS) system—Case study. Energies, 14 , 7086.

Eskerod, P., Hollensen, S., Morales-Contreras, M. F., & Arteaga-Ortiz, J. (2019). Drivers for pursuing sustainability through IoT technology within high-end hotels-an exploratory study. Sustainability (Switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195372

Ferreira, J. J., Ratten, V., & Dana, L. P. (2017). Knowledge spillover-based strategic entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13 (1), 161–167.

Filho, W. L., Ng, A. W., Sharif, A., Janová, J., Özuyar, P. G., Hemani, C., Heyes, G., Njau, D., & Rampasso, I. (2022). Global tourism, climate change and energy sustainability: Assessing carbon reduction mitigating measures from the aviation industry. Sustainability Science . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01207-x

Filimonau, V., & Naumova, E. (2020). The blockchain technology and the scope of its application in hospitality operations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87 , 1–8.

Friedrich, J., Stahl, J., Hoogendoorn, G., & Fitchett, J. M. (2020). Exploring climate change threats to beach tourism destinations: Application of the Hazard–Activity Pairs methodology to South Africa. American Meteorological Society, 12 , 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-19-0133.1

Gierczak-Korzeniowska, B. (2020). Tourist and business models in the mobility of customers using car rental services. Geography and Tourism, 8 (2), 29–39.

Guan, H., Liu, H., & Saadé, R. G. (2022). Analysis of carbon emission reduction in international civil aviation through the lens of shared triple bottom line value creation. Sustainability, 14 , 8513.

Kayumovich, K. O. (2020). Prospects of digital tourism development. Economics, 1 (44).

Kindzule-Millere, I., & Zeverte-Rivza, S. (2022). Digital transformation in tourism: Opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference “ECONOMIC SCIENCE FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT” No 56 Jelgava, LLU ESAF, 11–13 May 2022, pp. 476–486. https://doi.org/10.22616/ESRD.2022.56.047478

Koçak, E., Ulucak, R., & Ulucak, Z. S. (2020). The impact of tourism developments on CO2 emissions: An advanced panel data estimation. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33 , 100611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100611

La, J., Bil, C., & Heiets, I. (2021). Impact of digital technologies on airline operations. Transportation Research Procedia, 56 , 63–70.

Liutikas, D. (2023). Post-COVID-19 tourism: Transformations of travelling experience. In K. Dube, G. Nhamo, & M. P. Swart (Eds.), COVID-19, Tourist destinations and prospects for recovery Volume one: A global perspective (pp. 277–301). Springer Nature.

Chapter Google Scholar

Molchanova, K. (2020). A review of digital technologies in aviation industry. Logistics and Transport, 47–48 , 69–77.

Moon, H. G., Lho, H. L., & Han, H. (2021). Self-check-in kiosk quality and airline non-contact service maximization: How to win air traveller satisfaction and loyalty in the post-pandemic world? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38 , 383–398.

Mudasir, N., Ghausee, S., & Stanikzai, H. U. R. (2020). A review of ecotourism and its economic, environmental and social impact. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 7 (8), 1739–1743.

Narayan, R., Gehlot, A., Singh, R., Akram, S. V., Priyadarshi, N., & Twala, B. (2022). Hospitality feedback system 4.0: Digitalization of feedback system with integration of industry 4.0 enabling technologies. Sustainability, 14 , 12158.

Ndhlovu, E., & Dube, K. (2023). Challenges of radical technological transition in the restaurant industry within developing countries. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 12 (1), 156–170.

Niedzielski, P., Durajczyk, P., & Drop, N. (2021). Utilizing the RIS system to improve the efficiency of inland waterway transport companies. Procedia Computer Science, 192 , 4853–4864.

Oke, A. E., Aigbavboa, C. O., & Raphiri, M. M. (2017). Students’ satisfaction with hostel accommodations in higher education institutions. Journal of Engineering, Design and Technology, 15 (5), 652–666.

Ouariti, O. Z., & Jebrane, E. M. (2020). The impact of transport infrastructure on tourism destination attractiveness: A case study of Marrakesh City, Morocco. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 9 (2), 1–18.

Papatheodorou, A. (2021). A review of research into air transport and tourism: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on air transport and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, 103151, 1–17.

Park, E. (2019). The role of satisfaction on customer reuse to airline services: An application of Big Data approaches. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47 , 370–374.

Peeters, P., Gössling, S., Klijs, J., Milano, C., Novelli, M., Dijkmans, C., et al. (2018). Research for TRAN committee - Overtourism: Impact and possible policy responses . European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies.

Peira, G., Guidice, A. L., & Miraglia, S. (2022). Railway and tourism: A systematic literature review. Tourism and Hospitality, 3 (1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010005

Pellegrino, F. (2021). Transport and tourism relationship. In F. Grasso & B. S. Sergi (Eds.), Tourism in the Mediterranean Sea (pp. 241–256). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Pereira-Doel, P., Font, X., Wyles, K., & Pereira-Moliner, J. (2019). Showering smartly. A field experiment using water-saving technology to foster pro- environmental behaviour among hotel guests. E-Review of Tourism Research, 17 (3), 407–425.

Priatmoko, S., & Dávid, L. D. (2021). Winning tourism digitalization opportunity in the Indonesia CBT business. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 37 (3), 800–806.

Prideaux, B. (2023). River and canal waterways as a Tourism resource. In J. S. Chen (Ed.), Advances in hospitality and leisure (Advances in hospitality and leisure) (Vol. 18, pp. 137–153). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1745-354220220000018008

Punter, L., & Hofman, W. (2022). Digital Inland Waterway Area: Towards a Digital Inland Waterway Area. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2017-12/2017-10-dina.pdf . Accessed 11/07/2023.

Radicic, D., & Petkovi’c, S. (2023). Impact of digitalization on technological innovations in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 191 , 122474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122474

Ramachandran, V., & Ruthramathi, V. (2020). Emerging issues and challenges of technology in tourism and hospitality industry. Studies in Indian Place Names, 40 (71), 30–33.

Ratten, V., Tajeddini, K., & Merkle, T. (2020). Tourism hospitality and digital transformation: The relevance for society. In K. Tajeddini, V. Ratten, & T. Merkel (Eds.), Tourism, hospitality and digital transformation, innovation and technology Horizons (pp. 1–5). Routledge, USA/Taylor & Francis Group.

Shabrina, Z., Buyuklieva, B., & Ng, M. K. M. (2020). Short-term rental platform in the urban tourism context: Geographically weighted regression. Geographical Analysis, 53 (4), 686–707.

Shirgaokar, M. (2018). Expanding seniors’ mobility through phone apps: Potential responses from the private and public sectors. Journal of Planning Education and Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18769133

Shiwakoti, N., Hu, Q., Pang, M. K., Cheung, T. M., Xu, Z., & Jiang, H. (2022). Passengers’ perceptions and satisfaction with digital technology adopted by Airlines during COVID-19 pandemic. Future Transportation, 2 , 988–1009.

Specht, P., Balmer, J., Jovic, M., & Meyer-Larsen, N. (2022). Digital information services needed for a sustainable inland waterway transportation business. Sustainability, 14 (11), 6392.

Sun, X., Wandelt, S., & Zhang, A. (2021). Technological and educational challenges towards pandemic-resilient aviation. Transport Policy, 114 , 104–115.

Tajeddini, K., Ratten, V., & Merkle, T. (2019). Tourism hospitality and digital transformation: The relevance for society. In K. Tajeddini, V. Ratten, & T. Merkle (Eds.), Tourism, hospitality and digital Transformation: Strategic management aspects. Innovation and technology horizons . Routledge.

Tanko, M., Cheemarkurthy, H., Kihl, S. H., & Garme, K. (2019). Water transit passenger perceptions and planning factors: A Swedish perspective. Travel Behaviour and Society, 16 , 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2019.02.002

Tayo, S. S., & Omotosho, A. A. (2021). Assessment of availability, accessibility and adequacy of hostel facilities in Nigerian universities. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education, 8 (7), 17–25.

Thi Phan, L., Sue-Ching, J., & Lin, J.-C. (2021). Untangling adaptive capacity in tourism: A narrative and systematic review. Environmental Research Letters, 16 , 123001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac32fa

Tijan, E., Agatić, A., Jović, M., & Aksentijević, S. (2019). Maritime National Single Window—A prerequisite for sustainable seaport business. Sustainability, 11 , 4570.

Verberght, E., Rashed, Y., van Hassel, E., & Vanelslander, T. (2022). Modeling the impact of the River Information Services Directive on the performance of inland navigation in the ARA Rhine Region. EJTIR, 2 , 53–82.

Walton, J. K. (2020). Tourism | definition, history, types, importance, & industry | Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/tourism

Wang, M., & Mu, L. (2018). Spatial disparities of Uber accessibility: An exploratory analysis in Atlanta, USA. Computers Environment and Urban Systems, 67 , 169–175.

Wang, X., Lai, I. K. W., Zhou, Q., & Pang, Y. H. (2021). Regional travel as an alternative form of Tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts of a low-risk perception and perceived benefits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 , 9422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179422

WTTC-UNEP-UNFCCC. (2021). A net zero roadmap for travel and tourism: Proposing a new target framework for the travel and tourism sector. https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2021/WTTC_Net_Zero_Roadmap-Annex.pdf

Yiamjanya, S. (2020). Industrial heritage along railway corridor: A gear towards tourism development, a case study of Lampang Province, Thailand. E3S Web Conference, 164 , 03002.

Yiu, C. Y., & Cheung, K. S. (2021). Urban zoning for sustainable Tourism: A continuum of accommodation to Enhance City resilience. Sustainability, 13 , 7317.

Youssef, A. B., & Zeqiri, A. (2021). Hospitality industry 4.0 and climate change. Circular Economy and Sustainability . https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00141-x

Zeqiri, A., Dahmani, M., & Youssef, A. B. (2020). Digitalization of the tourism industry: What are the impacts of the new wave of technologies. Balkan Economic Review, 2 , 63–82.

Zhang, J., & Shang, Y. (2022). The influence and mechanism of digital economy on the development of the Tourism service trade—Analysis of the mediating effect of carbon emissions under the background of COP26. Sustainability, 14 , 13414. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14201341

Zlatanova, Z. (2020). Internet marketing and changes in the management and distribution of tourism companies . Publishing Complex Avangard Prima.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vaal University of Technology, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

Emmanuel Ndhlovu, Kaitano Dube & Catherine Muyama Kifworo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Emmanuel Ndhlovu

Kaitano Dube

Catherine Muyama Kifworo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ndhlovu, E., Dube, K., Kifworo, C.M. (2024). Tourism and Hospitality Trends and Sustainable Development: Emerging Issues in the Digital Era. In: Ndhlovu, E., Dube, K., Kifworo, C.M. (eds) Tourism and Hospitality for Sustainable Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63073-6_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63073-6_1

Published : 28 August 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-63072-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-63073-6

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

COMMUNITY CASE STUDY article

Toward sustainable tourism in qatar: msheireb downtown doha as a case study.

- Department of Humanities, College of Arts and Sciences, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Qatar has developed a strategy of sustainable tourism and development, which focuses on highlighting the spirit of the Qatari identity and heritage. This strategy goes hand in hand together with the line of the Qatar National Vision 2030. Hence, Msheireb Properties, which is a real estate development company and a subsidiary of Qatar Foundation, focuses in developing a sustainable tourism strategy. Thus, Qatari cultural heritage presented in the heart of the post-modern futuristic city of Msheireb through the project of Msheireb Museums that are hosted in four traditional houses. Msheireb Properties renovated the four houses in a sustainable way that aimed to create a dynamic relationship between tourism and cultural heritage. Msheireb Properties preserved models of traditional architecture through the establishment of Msheireb Museums. This article discusses the development of sustainable tourism in Qatar and the preservation of the Qatari cultural heritage and identity through the story of two museums in Msheireb, the Radwani House Museum and the Company House Museum.

Introduction

The relationship between the past and the present is vital, as the past is an integral tool for building both the present and the future. Attempts to preserve the cultural heritage of nations vary, as some societies try to highlight their cultural uniqueness from others ( Al-Saadani, 2017 ). For example, China sent a few Terracotta soldiers to an exhibition at the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, and this loan contributed to promoting the Chinese nation's legacy outside of its borders ( Qatar Museums, 2017 ). China also created a traditional dress for itself in the 1960s, to be unique from its neighbors Japan and Korea ( Lau, 2010 ).

A nation's heritage supports a better appreciation for the history and nobility of the state. Architectural legacies are particularly important. Architectural styles indicate the possibilities of materials and styles that were available locally or imported from the neighborhood through the trade existing at the time and what distinguishes one region from another. Analyzing the architecture, in terms of size, materials, luxury, and the age of its construction, helps illuminate the extent of the state's capabilities and economic factors during different historical periods. More importantly, the preservation of a nation's architectural heritage is a fundamental tool for ensuring sustainable tourism.

The Concept of Sustainable Tourism

According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization and United Nations Environment Program, sustainable tourism is an approach that takes full account of its present and future environmental and social impacts and economic influences while addressing the needs of the industry, visitors, and host communities. It implies that sustainable tourism focuses on sustainable practices and impacts in and by the tourism sector. The key stakeholders in the industry acknowledge its impacts, both negative and positive 1 .

In Qatar, the primary focus of sustainable tourism is to minimize the negative impacts while maximizing the positive ones. Analytically, the negative impacts on tourism to a particular destination include damages to the natural environment, overcrowding, displacement, and economic leakage. For instance, sustainable tourism resulted in massive displacement of the original inhabitants and communities in the Msheireb area before its development. Equally, due to the cost of access, some lower-class communities find it challenging to access the newly developed sites. It implies that sustainable tourism comes with a cost that different stakeholders within the immediate environment have to pay for success to achieve.

However, tourism's positive impacts on its destination include cultural heritage preservation, job creation, wildlife preservation, cultural interpretation, and landscape restoration. In its entirety, sustainable tourism takes a holistic approach that looks at the socio-cultural, environmental, and economic aspects of tourism development. It implies that for excellence to be achieved in sustainable tourism, key stakeholders must strike a balance between the three core dimensions to ensure its long-term sustainability ( Trahant, 2018 ; Waheeb and Zuhair, 2018 ).

Globally, sustainable tourism has made tourism a significant economic activity in and around protected sites, forests, museums, and other attraction points. Well-planned sustainable tourism programs can create opportunities for the visitors to experience human communities, interact with natural areas, and actively learn about the significance of local culture and conservation needs ( Pedersen, 2004 ). As such, it remains imperative to outline the triple bottom line of sustainable tourism as per the International Ecotourism Society.

Economically: Sustainable tourism works to contribute to the overall economic well-being of the immediate environment. It generates equitable and sustainable income and resources for the local community, stakeholders, and shareholders within the area. The activities involved in sustainable tourism have a direct benefit on neighbors, owners, and employees. However, there are situations where detrimental impacts could be witnessed through the displacement of communities 2 .

Environmentally: The activities of sustainable tourism have a low impact on natural resources. It strives to minimize the damage to the habitats, flora and fauna, marine resources, water, and energy. In totality, it works to benefit the overall environment and the people interacting with it.

Socially and culturally: As revealed by the International Ecotourism Society, activities involved in sustainable tourism do not harm or interfere with the culture or social structure of the community. Instead, it values and respects the norms, values, traditions, and cultures of local people. It creates a collaborative shareholding of communities, governmental institutions, individuals, tour operators, and communities in planning, developing, evaluating, and monitoring diverse roles in conservation 3 .

In totality, the conceptual exploration has shown that sustainable tourism strives to meet the needs and preferences of present host regions, tourists, and stakeholders while offering opportunities and protecting the environment and biodiversity for the future. It guarantees that sustainable management of all-natural resources is done in a manner that social, economic, and aesthetic needs are fulfilled while enhancing the vital ecological processes, cultural integrity, life support systems, and biological diversity. In the context of sustainable tourism, Qatar is one country that has focused on tourism as a cultural, economic development strategy.

As a cultural and economic development strategy, sustainable tourism strives to utilize available resources for the social, economic and aesthetic well-being of both locals and foreign tourists. It also protects resources and opportunities for future generations. It stresses safeguarding and protecting the traditions and cultural heritage of communities. It seeks to preserve historical resources for future generations by using tourism to prevent undesirable socio-economic impacts and to promote local communities socially and economically ( Vehbi, 2012 ). Sustainable tourism also encounters the contemporary needs of tourists and host countries by managing a state's resources, while preserving its cultural heritage and promoting essential ecological development ( Pedersen, 2004 ).

Qatar's Socio-Historical Transformation

Heritage plays a critical role in Qatar's socio-historical transformation as it links the people with their culture and history while offering a sense of identity. Qatar's heritage resources have been having a significant impact on tourism. Although Qatar's heritage has been a source of pride, the increased modernization of cities such as Doha has seen historical buildings, districts, and centers become victims. They are brought down and replaced with modern buildings. Even though heritage preservation still thrives in Qatar, the rapid disappearance of the historically developed fabric of the nation has been a concern as it is difficult to retain the real-feel heritage retention. It remains imperative to integrate the concept of heritage, social identity, and history when exploring sustainable tourism in Qatar ( Vehbi, 2012 ).

Historically, Qatar began being inhabited in the early fourth Century. However, much of the history is traced to the eighteenth Century after the Al-Thani family emerged as the first rulers of the nation. The desert situation of Qatar's environment affected the establishment of human settlement due to the harsh and unbearable hot climate. As a result, many opted to live along the coast with the renowned old settlement known as Al-Bidda. Around the 1800s, the Al-Thani decided to relocate to the coast, where they established Doha as the main settlement next to Al-Bidda. By 1887, it was placed as a British protectorate. To date, Doha, the capital of Qatar, has transformed with high rising physical and economic developments due to the increase in revenue from petroleum resources.

Analytically, the urbanism and architecture of Qatar provide the eminent image of the urban identity and cultural heritage transformation that has occurred in residential architecture and the built environment. Irrespective of the transformation, one concept that has remained the same is the tradition and social identity as expressed through the practices of the Qatar people. The practices are actively shared through the Islamic world and the region as a whole. Qatar's vision 2030 has worked with a core focus of embracing tourism as a critical cultural, economic development strategy. It thrives under Qatar's vision 2030's four pillars: environmental development, economic development, human development, and social development. It works to bridge the gap between the present and the future generation ( Qatar, 2019 ).

Owing to Qatar's massive development, its rich culture and heritage, history, and globally recognized growth, it has captured tourism as a cultural, economic development strategy by offering visitors an opportunity to view the beautiful contrast between the past and the future presented in a single frame. Among the most notable transformations are the rising and modern-designed technology parks, over 1,400 years of Islamic history, and integration of tradition and modernity seated side by side within the majestic desert landscapes. In order to sustain its tourism, Qatar has adopted the concept of sustainable tourism as reflected through the activities of Msheireb museums.

In 2011, Qatar launched the Qatar National Vision 2030 that provides the blueprint and guidance to its sustainable economic diversification and long-term development. The plan harbors tourism as a designated priority industry. It serves the country with opportunities to build and achieve sustainable economic growth while enhancing its natural and cultural gems. Equally, in 2014, the Qatar Tourism Authority developed the Qatar National Tourism Sector Strategy 2030 that designs the pathway through which the country will achieve sustainable development for the tourism sector by 2030. The dedication by the sustainable tourism teams through QNTSS 2030 has seen the country welcome over 9 million new visitors. More importantly, the average annual growth of the tourism sector's arrivals has grown from insignificant numbers in the 1990s to over 6% between 2012 and 2016. Such growth has been reflected with a 4.3% increase impact on total Qatar's GDP. Critically, the advancement in modern Qatar's tourism sector has proved the significant social-historical transformation of the country and the reliance on tourism as an important cultural, economic development strategy 4 .

The current state of Qatar connects the concept of sustainable tourism with the broader themes of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG Goal 8, 12, and 14 aligns with Qatar's sustainable tourism concept. SDG goal 8 strives to promote inclusive, equitable, decent work and sustainable economic growth. It works to ensure productive employment for all. Goal 12 focuses on guaranteeing responsible consumption and production. Sustainable tourism in Qatar has worked to reduce the increasing trend in toxic waste products through the adoption of technology and innovation. Equally, it has adopted the environment protection and conservation concept to maintain the value held by natural resources. Local authorities are also actively involved in the protection of natural gems to ensure that the heritage of Qatar is well-preserved ( Qatar, 2019 ).

Additionally, the tourism sector in Qatar strives to conserve marine resources in the region. The dedication aligns with SDG goal 14 that works to conserve and sustainably utilize seas, oceans, and marine resources for guaranteed sustainable development. Through the climate change programs and initiatives, Qatar's tourism sector has attained its sustainable tourism milestones that have increased the conservation objectives and visitor footprints to its tourism areas associated with economic and financial income for the country.

As highlighted by Hmood et al. (2018) , one of the most important sources for the diversification of a country's financial income is tourism. Over the last century, the tourism industry in the world has grown rapidly. Consequently, cultural heritage tourism has become an important source of income for many nations. Investment in cultural heritage tourism has convinced many states of the importance of the preservation and utilization of their cultural heritage. Such tourism has become trendy and is a significant tool in terms of promoting sustainable development. Accordingly, countries have invested their resources to develop the country's architectural heritage and advertise their unique heritage.

Natural resources have been a game-charge in the tourism and development milestones covered by Qatar. With the discovery of oil, life in Qatar changed and developed rapidly, including the development of various professions and architectural designs, and changes in the social life and traditions of Qatari families. To illustrate such changes, four historical houses were converted into museums at Msheireb heritage downtown, located in the heart of the capital Doha. They include the Company House “bait Alshareekah,” the Radwani House, the Bin Jalmood House, and the Mohammed bin Jassim House.

This article focuses on the Company House Museum and the Radwani House Museum as examples that demonstrate Qatar's use of sustainable tourism. These historical houses present information that illustrates the life of the Qatari family in the twentieth century. This article analyses the importance of museums in bridging the gap between the past and present through their architectural heritage and the presentation of social and economic developments that occurred in Qatar in the twentieth century.

It highlights how Qatar is using sustainable tourism to preserve cultural heritage within the new development of a futuristic downtown Msheireb. It also highlights the role of Qatari museums in narrating these developments that led to the emergence of Qatar today. This article focuses on the efforts of the state to preserve its cultural heritage while modernizing and globalizing as a result of the oil industry boom.

Architectural Heritage as a Tool of Sustainable Tourism

Kabila, Jumaily, and Melnik define sustainable tourism as “a development model which administrates all of the resources for the economic, social and aesthetical needs of locals and visitors, and provides the same conditions for future generations. Most definitions of sustainable tourism emphasize the environmental, social and economic elements of tourism” ( Hmood et al., 2018 , p. 3). Architecture as a tangible heritage material plays a similar role to pieces that can be sent around the world in exhibitions. However, because architecture remains in its place, visitors can enjoy it as an outdoor gallery. To explain the importance of the contribution of architectural heritage in promoting sustainable tourism and creating income for a country, it is useful to examine the model of Vienna. In 1990, Vienna hosted approximately 3.15 million visitors, of whom ~1.1 million visited museums that reflected the city's architectural legacies. In addition, 487,000 tickets were sold to attend a theater dating back to 1870. In 2001, Vienna submitted a request to include its city center on the UNESCO World Heritage List ( Republic of Austria, 2020 ).

The city of Vienna could attract tourists because it refused to convert the architectural heritage into static, non-interactive museums. Instead, the city managed and activated these historical sites by housing local businesses in these traditional/historical buildings and obliged the residents to establish entertainment activities and programmes that engaged the public ( Republic of Austria, 2020 ).

Likewise, in Qatar, there is a growing interest in efforts to preserve the Qatari architectural heritage. The policy that the Qatari government is following in preserving the nation's architectural heritage has had a positive socio-culture impact. It offers its population the opportunity to learn about their ancestors' legacies, culture, heritage, and traditions. Meanwhile, it also creates spaces where tourists can experience and encounter the local cultural heritage. Qatar Museums (QM) protects heritage buildings and gives them new energy despite the transformation of the environment around them under the slogan “A new life for old Qatar.” QM is keen to develop sustainable tourism, which ensures that locals maintain their relationship with the past under the current transformations. Therefore, heritage experts try to develop solutions that enable them to integrate the old material heritage with the present, while making some sacrifices. Sustainable tourism is a very important element for a country like Qatar, as the state is considered a leading center in the region due to its strategic location and possession of the best aviation network in the world, Qatar Airways. The cancellation of entry permit visas for 80 countries, prepared Qatar to expect a large crowd of tourists, specifically in the year 2022 for the FIFA World Cup. The state hopes to preserve visitors' access even after the World Cup ends by establishing rules for sustainable tourism investment ( Skytrax, 2020 ). To invest in tourism, it was necessary to highlight the Qatari identity and enable it as one of the factors of tourist attractions after the end of the World Cup. The government has focused on designing buildings that highlight the Qatari architectural style, such as the cultural village of Katara, Msheireb Museums, Souq Waqif, Souq Al-Wakra, Souq Ruwais, and finally the opening of the National Museum of Qatar in 2019. Therefore, the Qatari government aspires to promote its tangible and intangible cultural heritage assets.

QM succeeded in including the historical fort of Al Zubarah on the list of the UNESCO World Heritage Organization. The next step was a plan to revive this historical place by, for example, inaugurating a tourist programme “Window on the Past” at Al Zubarah fort. The programme adopted a mechanism of breaking the deadlock by reviving activities through conducting guided tours, presenting local foods, displaying handicraft workshops, riding camels, and other traditional activities that might interest tourists ( Qatar, 2021 ). In addition, to enhance the engagement of the visitors within museums and cultural sites and to make these areas more active, some Qatari museums, such as the Museum of Islamic Art and the National Museum of Qatar, established parks and bazaars ( Museum of Islamic Arts, 2021 ). Reviving these legacies is one of the pillars of national development. Qatar's National Vision 2030 emphasizes social development, which focuses on the preservation and protection of national cultural heritage and Islamic values and identity ( Qatar Planning Statistics Authority, 2021 ). This emphasis reflects the strenuous efforts by QM to engage the community with museum practices.

Similarly, the Qatar Foundation (QF) seeks to activate and revive historical sites within post-modern Qatar through Msheireb Properties (MP). Msheireb Properties is a real estate development company and a subsidiary of QF. The company establishes ventures to support the goals of Qatar's National Vision 2030. Thus, MP focuses on the national development of innovative and sustainable projects that protect the Qatari cultural heritage. MP preserved models of traditional architecture through the establishment of Msheireb Museums. MP used a mechanism of architectural heritage documentation and sustainable tourism to enhance and enrich civic inheritance and heritage tourism without preventing modernization by renovating four historical buildings and reusing them as museums ( Msheireb Properties, 2021a ).

MP renovated the four houses in a sustainable way that aimed to create a dynamic relationship between tourism and cultural heritage. MP tried as much as possible to maintain the authenticity of the houses as a Qatari architectural inheritance. Keeping their authenticity as buildings with their collections, narratives, and roles was an essential component of their cultural importance. Heritage tourism enriches both sustainable tourism and cultural tourism, with an emphasis on maintaining natural surroundings and cultural heritage as much as possible in its original form. Heritage tourism rests on the importance of the cultural and natural environment. Such tourists prefer to visit heritage and historical sites, such as old souqs, forts, castles, museums, preserved parks, and nature reserves. They also prefer a minimum amount of environmental damage and impact ( Hmood et al., 2018 , p. 3). The renovation of those four historical houses created great opportunities for modern people to have a direct experience with the memory and intangible untold heritage and direct contact with the past. It allows the current generation to experience the places, learn about past activities and hear their ancestors' stories with all their ups and downs ( Msheireb Properties, 2021a ). This analysis of the preservation of the Qatari architectural heritage in Msheireb downtown focuses on two primary aspects. First, this preservation aimed to improve and develop the beauty and artistic features of the architectural heritage. Second, it aimed to introduce the futuristic city of Msheireb with its new architectural language in a manner that did not risk losing or harming the authentic local heritage. This approach leads to the questions, to what extent does the new Msheireb preserve the natural surroundings of the original old Msheireb? and does the current Msheireb reflect the old Msheireb downtown?

Msheireb the Old City

Traditionally, Msheireb means “a place to drink water,” as this town was built around a well that was generous enough to serve the whole area, which attracted the community that settled there ( Msheireb Properties, 2021b ). Historically, the town was a vibrant neighborhood that centered around Kahraba Street, which means “electricity,” an area that was the first to receive electricity in Doha. In the past, the shops were confined to the traditional souqs, or marketplaces, known to the people in Qatar, such as Souq Waqif, the internal souq and the Qaysariya souq. These souqs opened in the early morning and closed in the afternoon for a lunch break, then reopened in the afternoon until sunset only. At the beginning of the 1960s, with the acceleration of the development that began in Doha, a new market appeared with new stores that differed from the traditional souqs. These stores had glass facades, modern decorations and new imported goods displayed in elegant and attractive ways that Qataris had not previously known. In this area, modern restaurants opened and served foods that were unknown in Qatar, such as shawarma sandwiches, hummus, mutabal, mixed grills, and grilled chicken. Modern groceries and supermarkets also opened in the area. In addition, the shops in this street were open from morning until midnight. Al-Kahraba Street, or “electricity street” at that time was not only a commercial street for buying and selling but also a cultural and tourist landmark that became famous among all the countries of the region for its modernity and vitality.

Tourists from outside Qatar and locals alike toured this street, enjoying its atmosphere by walking, buying imported goods, and enjoying new options of food and drink. The movement in the street did not stop until dawn, as this street was the only outlet for people, young and old, rich and poor ( Al-Malki, 2013 ). Annually, tens of thousands of locals and visitors go to Msheireb Downtown to see and interact with the Qatari architectural aesthetic that integrates the country's sustainable and functional practices commonly known as the “Seven Steps” to protect and nurture Qatar's built and cultural heritage. A key attraction for the visitors is the close-knot pedestrian streets that reflect and foster the strong social ties held by the Qatari people.

The rapid growth of Qatar has produced some challenges, such as transforming the original identities of the state's cities and their ways of living. These transformations created a huge gap between traditional Qatari architecture and lifestyles and those in current Doha with its post-modern architecture and lifestyles. Msheireb became the site of an ambitious plan to regenerate the town ( Monocle, 2020 ). The foundation of the project began with the patronage of Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser Al-Misned, who established Msheireb Properties with an obligation to address the gap between the past and the present and revive a distinctive form of Qatari urban development. It is a redevelopment initiative that bridged the gap between Qatar's heritage and the futuristic city of Doha ( Monocle, 2020 ). Msheireb preserved its atmosphere and role as a tourist destination, where people can enjoy walking and having food and drinks. However, the architectural heritage was completely lost and replaced with new buildings and a new urban layout. Consequently, the preservation of four historical houses and their function as museums came to fill the gap of representing a part of the lifestyle that was once there at the beginning of Qatar's development.

Msheireb Museums: The Past Overlaps With the Present

Museums are of great importance in narrating stories of the social and economic life of any society, as they preserve the material evidence of those societies. Museums are among the most important means of expressing the heritage and history of civilizations and societies, as they document the lives and activities of people and the places in which they lived. They also vary in nature and specialties. Some museums specialize in art, such as the Islamic Museum in Qatar, which includes many monuments of Islamic arts, and other museums specialized in heritage, such as Msheireb Museums, which convey parts of Qatar's past.

Like museums, architectural features also highlight the identity of the state by illustrating multiple factors that relate to the development of the state of Qatar. Architecture can provide a set of facts that contribute to highlighting the state's past and knowledge of its sovereign, economic and social politics. It is from the architectural heritage and legacies of the former inhabitants that we can better understand how this society developed.

QF aims to highlight the spirit of the Qatari identity, presented in the heart of the post-modern futuristic city of Msheireb, with four traditional houses. The location of the Msheireb museums serves as a tool to document the history and architectural heritage while also documenting Qatar's economic development. Each renovated house emphasizes an original architectural feature. The first house, the Bin Jelmood House, was originally a slave house. The house acknowledges the economic, social, and cultural contributions of previously enslaved people to the improvement of human civilizations ( Msheireb Museums, 2021a ). The second house, the Radwani House, represents an integrated residence for a Qatari house. The house was built in the 1920s on a location separating the oldest districts of Doha, Al Jasra and Msheireb. The house documents the lifestyle of the Qatari family in the early twentieth century. Visiting the museum allows people to learn about everything that characterizes that period ( Msheireb Museums, 2021e ). The third house, the Company House, was once used as the headquarters for the first oil company in Qatar, the British Oil Company. The museum was developed to narrate the story of the Qatari pioneers in the petroleum industry. They assisted the transformation of Qatar into a modern society, by demonstrating remarkable dedication. The museum exhibit tells their stories in their own simple words and narrations. They describe what they endured and how they labored to provide a better future for the coming generations and the country ( Msheireb Museums, 2021b ). The fourth house, the House of Mohammed Bin Jassim, focuses on the son of the founder of modern Qatar. He devoted part of his house to serve as a medical facility, leading the state to design the nation's first hospital. The house reveals “Msheireb's traditional values as the foundations for the future development of Doha and introduces the transformation of Msheireb over time through recalling memories of its past, showcasing its present, and engaging visitors in the plans for the future” ( Msheireb Museums, 2021d ).

All of these buildings, with their various specializations and close proximity, demonstrate the center of gravity of that vital region with its ancient and modern facilities ( Msheireb Museums, 2021c ). Together, they allow the visitor to become acquainted with the patterns of Qatari architecture in the past. To make the area lively for the locals, the post-modern futuristic city of Msheireb was built, which takes inspiration from the traditional buildings of the four Msheireb museums that are considered the cultural destination of the post-modern city ( Qatar Museums, 2020 ). The challenge that MP undertook with this project was to invent an approach that balanced financial benefits with the protection of local cultural identity and nature. The preservation and presentation of cultural heritage within sustainable tourism have positive social and economic impacts. They strengthen local identity and allow local people to move forward. They also help to introduce tourism positively and raise awareness of the importance of authenticity and values ( Hmood et al., 2018 , p. 4). This challenge raises the question of how far the reinvention of Msheireb preserves and reflects Qatari social life and heritage. Reaching an answer requires reflecting on the social and economic lives of the Qataris before and after the discovery of oil.

Economic and Social Development

Before the discovery of oil, Qatari society was modest and primarily a tribal society. In addition to the tribes in the area, there were also Qatari families, who cooperated with the tribes, making the primary feature of Qatari society one of collaboration. In its economic development, Qatari society went through different stages, which affected its social life. The first stage was the era of diving, when pearling was the main economic activity for the Qatari. That period corresponded with the beginning of the emergence of Qatari society, which at the beginning of the twentieth century reached about 32,000 people, of whom 4,000 were Bedouins, and the remainder were settled residents ( Al-Zaidi, 2010 ).

The second stage was the transition from diving to the oil era, beginning in the mid-1930s. The signing of an oil concession agreement with the State of Qatar in May 1935 led to the deterioration of the diving industry. The role of tribalism declined under the new oil con concession agreement and the new professions that accompanied it.

Qatar is part of the Arabian Gulf society, culture and economy. Thus, through different eras and under different circumstances, residents of Qatar have sought a safe and stable life, focusing on earning a livelihood from the sea or on land from grazing or the life of the desert. After the discovery of oil, the course of social life changed, and Qatari society became divided into classes after it had been divided into multiple tribes.

The Role of Persian Migration in the Society

With the discovery of oil in the Arabian Gulf countries, Persian families began to immigrate to the region. At that time the region provided golden opportunities for Persian merchant families and Persian individuals seeking new economic opportunities and work. Like other Arabian Gulf countries, Qatar received an influx of Persian migrants, who came to Qatar for economic opportunities and material gain. As they integrated into the Qatari society, they identified with the locals but maintained their original language and an accent that differs from that of the prominent families in Doha ( Al-Mokh, 2019 ).

The regularity of oil wealth and the accompanying transformation process led to an increase in the state's economic activity. One of the Persian families that migrated to Qatar at the beginning of the twentieth century was the Al-Radwani family. They came to play a significant role in the social and economic life of Qatar and represent an example of a Persian family, who chose to settle in Doha during the economic and social development of the country.

Radwani House Museum: Social and Economic Transformation

The Radwani House in the heart of the Msheireb downtown area represents one of its historical landmarks, which summarizes Qatari folklife and its transformations since the 1920s. The traditional architecture used climate-friendly materials and took into account the local culture. It had specific restrictions that met the needs of living and did not contradict Qatari customs and traditions. The construction of the Al-Radwani House dates back to the 1920s and is located on a site that separates the two oldest neighborhoods in Doha, those of Al Jasra and Msheireb. Ali Akbar Radwani bought the house on December 5, 1936, and it remained the property of his family for more than 70 years ( Hudayb, 2020 ).

In the mid-1930s, this building underwent modifications in its design, preserving its old walls, while demolishing other parts and reusing them in new construction, a practice common at that time. The house underwent expansions and redesigns several times, and today it is one of the oldest historic houses in Doha ( Hudayb, 2020 ).

A tour of the Radwani House Museum gives an idea of how it developed over time, as well as how the traditional pattern of family life in Qatar developed. The house had an open courtyard called the “ housh ,” an important space for family gatherings.

The house displays the life of the Qatari family in the past through its Indian-style bedroom, its modest furniture, the kitchen that uses old clay pots, and household tools that were used in the production of bread and food preparation. In addition to the living room with its simple furniture, a sewing machine embodies the image of the Qatari woman who used to sew clothes for her family members ( Hudayb, 2020 ). Although the Al-Radwani House has undergone many expansions and reconstruction processes throughout its history, it has preserved the traditional pattern of Qatari houses based on the presence of a central courtyard in the middle of the house. In accordance with the prevailing traditions, the external facade of the house is windowless for the privacy of the residents, except for the “ majlis ” in which the guests were received. To preserve the privacy of the courtyard area, access to the majlis is through a corridor that begins at the main door of the house and proceeds at a 90-degree angle to makes it difficult for the guests to see the courtyard and those in it ( Hudayb, 2020 ).

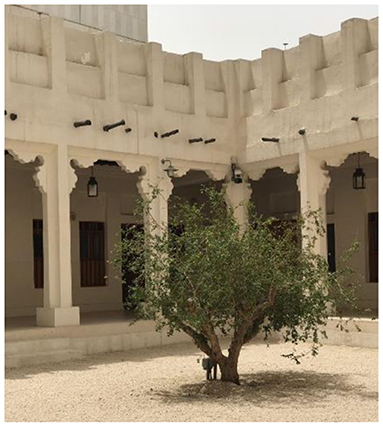

After the Radwani family moved out in 1971, the house sat deserted. In 2007, restoration work began based on archival research, interviews with people who knew the history of the house and an engineering survey to determine if it could be restored safely. The restoration process used traditional building materials and methods as much as possible, but with the adoption of modern engineering methods when necessary. For example, the stone columns and wooden lintels in the “ Liwan ” were replaced by concrete columns and steel beams to ensure the integrity of the building ( Figure 1 ) ( Al-sheeb, 2020 ). 5

Figure 1 . A traditional courtyard was a primary feature in Qatari houses that surrounded the open sitting area Liwan .

Archaeological excavations at the Radwani House were carried out in four stages:

1. Formulate objectives by studying the historical emergence of the city of Doha and how it transformed into a modern city.

2. Study maps and oral documentation of Msheireb City to understand the history of the region.

3. Begin excavations at several sites for their historical value.

4. Evaluate and analyse the data and information from the previous stages ( Al-sheeb, 2020 ). 6

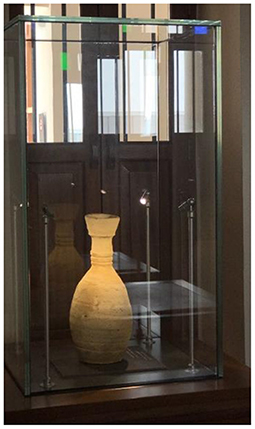

Excavations revealed ancient lighting equipment and the remains of a light bulb and located a “ Qudo ” 7 ( Figure 2 ) used for smoking tobacco with a stove to light coal. The excavations also found many children's toys, small bottles for perfumes, glass balls, a censer for oud and incense made of limestone, indicating that life in the middle of the twentieth century had begun to gain more amenities and entertainment options. Another traditional feature that the house preserved was the idea of distributing the rooms around the perimeter of the yard.

Figure 2 . Qudo is an Iranian traditional smoking tool that was brought to Qatar by Iranian immigrants and integrated into Qatari heritage.

The rooms in the house museum represent chronologically how the lifestyle changed according to the circumstances. For example, the first room reflects life in Qatar before the arrival of electricity. The second room shows the nature of daily life for the generation that immediately followed the arrival of electricity ( Al-sheeb, 2020 ). On the right side, there are indications of a bath and a well of water for daily use, as people used to bring pure water from other areas or it was sold through “ al-Kandari .” On the other side are cavities that reflect the foundations of the original building of the Radwani House ( Al-sheeb, 2020 ). 8

Heritage tourism at the Radwani House Museum embraces the preservation of identity, nostalgia needs, cultural heritage tourism, and conserving the resource from deterioration. Heritage tourism depends mostly on the cultural atmosphere and focuses on the heritage and historical values of the house ( Hmood, 2007 ). Heritage tourism makes visits to museums a pleasurable practice. This kind of tourism is concerned with the preservation and protection of the national identity and heritage and can reflect a green tourism approach. Within the museum exhibitions and collections, visitors travel in time and history. During their leisurely walk through the futuristic city of Msheireb, visitors can enter the house to find themselves suddenly in a very traditional place in old Msheireb, where they can experience Qatari traditional artifacts, activities and places that genuinely represent, and narrate the story of the people ( Hmood et al., 2018 ). The old historical house is not separated from the post-modern architecture by a space. Rather, the historical house preserved its architectural style while the post-modern surrounding spaces were developed around it. Urban protection in historical downtown Msheireb is accomplished by applying urban renewal strategies, which sustain the urban material and construction of the inherited houses and city while meeting contemporary demands ( Cohen, 2011 ). Over the years, over 80,000 visitors have entered the Radwani House Museum to celebrate and understand the Qatari heritage and culture.

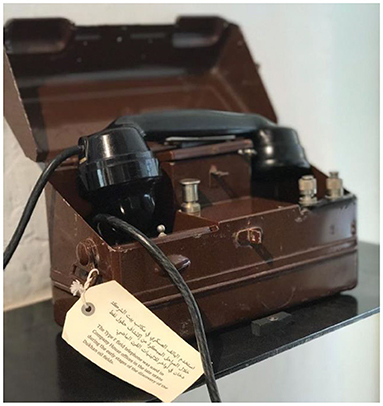

The Company House Museum: Qatar's Development

The Company House is the most important landmark in the Msheireb neighborhood. It was built by Hussain Al-Naama, the director of the Doha Port, as a home for his family. In 1935, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company rented the house was rented to serve as the headquarters of the first oil extraction company in Qatar after it was awarded a contract to explore and extract oil from the Qatari lands in the 1930s. During that time, Qatari laborers gathered outside the company's house to board trucks, which took them on arduous trips to the oil fields in the desert in Dhukhan city, ~85 km outside of Doha. 9

Before the discovery of oil, life in Qatar was different, as the professions were divided into two parts with a section for women. One of them was the profession of traditional medicine. Before the construction of modern and professional hospitals in Qatar, people relied on traditional medicine for treatment. Women treated women, helping them to give birth and treating girls and children. They treated illnesses such as sprain, bile, and measles by using medicinal herbs or cauterization with fire. The profession of sewing was called “Darze or Tailor,” and it caused a fundamental change in the life and behavior of women in Qatar. It includes sewing in all its forms ( Al-Malki, 2008 ). The profession of a street vendor, which was not limited to men, involved knocking on doors to sell what they had, including eyeliner, henna, sewing tools, etc. It is worth noting that many who engaged in this profession were immigrant women from Iran ( Al-Malki, 2008 ).

Professions for men also varied and included practitioners of traditional medicine, who used herbs to treat people, especially men, before the hospitals were established; waterers, who watered the neighborhood and brought water from wells; and bakers, who prepared bread. There were marine professions, including fishing, shipbuilding, diving, and pearling ( Al-Malki, 2008 ). Before the discovery of oil, pearling was the primary trading activity upon which Qatar's economy depended. Fishing pearls was a collective effort among the ship's crew, which might number between 10 and 40 men and occasionally more than 70, depending on the size of the ship ( Ahmed, 2014 ).