Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How To Write a Manuscript? Step-by-Step Guide to Research Manuscript Writing

Getting published for the first time is a crucial milestone for researchers, especially early career academics. However, the journey starting from how to write a manuscript for a journal to successfully submitting your scientific study and then getting it published can be a long and arduous one. Many find it impossible to break through the editorial and peer review barriers to get their first article published. In fact, the pressure to publish, the high rejection rates of prestigious journals, and the waiting period for a publication decision may often cause researchers to doubt themselves, which negatively impacts research productivity.

While there is no quick and easy way to getting published, there are some proven tips for writing a manuscript that can help get your work the attention it deserves. By ensuring that you’ve accounted for and ticked the checklist for manuscript writing in research you can significantly increase the chances of your manuscript being accepted.

In this step‐by‐step guide, we answer the question – how to write a manuscript for publication – by presenting some practical tips for the same.

As a first step, it is important that you spend time to identify and evaluate the journal you plan to submit your manuscript to. Data shows that 21% of manuscripts are desk rejected by journals, with another approximately 40% being rejected after peer review 1 , often because editors feel that the submission does not add to the “conversation” in their journal. Therefore, even before you actually begin the process of manuscript writing, it is a good idea to find out how other similar studies have been presented. This will not only give you an understanding of where your research stands within the wider academic landscape, it will also provide valuable insights on how to present your study when writing a manuscript so that it addresses the gaps in knowledge and stands apart from current published literature.

The next step is to begin the manuscript writing process. This is the part that people find really daunting. Most early career academics feel overwhelmed at this point, and they often look for tips on how to write a manuscript to help them sort through all the research data and present it correctly. Experts suggest following the IMRaD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) structure that organizes research findings into logical sections and presents ideas and thoughts more coherently for readers.

- The introduction should state the research problem addressed in your study and highlight its significance in your research domain. A well-crafted introduction is a key element that will compel readers to delve further into the body of your manuscript.

- The materials and methods section should include what you did and how you conducted your research – the tools, techniques, and instruments used, the data collection methods, and details about the lab environment. Ensuring clarity in this section when writing a manuscript is critical for success.

- The results section must include complete details of the most significant findings in your study and indicate whether you were able to solve the problem outlined in the introduction. In your manuscript writing process, remember that using tables and figures will help to simplify complex data and results for readers.

- The discussion section is where you evaluate your results in the context of existing published literature, analyze the implications and meaning of your findings, draw conclusions, and discuss the impact of your research.

You can learn more about the IMRaD structure and master the art of crafting a well-structured manuscript that impresses journal editors and readers in this in-depth course for researchers , which is available free with a Researcher.Life subscription.

When writing a manuscript and putting the structure together, more often than not, researchers end up spending a lot of time writing the “meat” of the article (i.e., the Methods, Results, and Discussion sections). Consequently, little thought goes into the title and abstract, while keywords get even lesser attention.

The key purpose of the abstract and title is to provide readers with information about whether or not the results of your study are relevant to them. One of my top tips on how to write a manuscript would be to spend some time ensuring that the title is clear and unambiguous, since it is typically the first element a reader encounters. This makes it one of the most important steps to writing a manuscript. Moreover, in addition to attracting potential readers, your research paper’s title is your first chance to make a good impression on reviewers and journal editors. A descriptive title and abstract will also make your paper stand out for the reader, who will be drawn in if they know exactly what you are presenting. In manuscript writing, remember that the more specific and accurate the title, the more chances of the manuscript being found and cited. Learn the dos and don’ts of drafting an effective title with the help of this comprehensive handbook for authors , which is also available on the Researcher.Life platform.

The title and the abstract together provide readers with a quick summary of the manuscript and offer a brief glimpse into your research and its scientific implications. The abstract must contain the main premise of your research and the questions you seek to answer. Often, the abstract might be the only part of the manuscript that is read by busy editors, therefore, it should represent a concise version of your complete manuscript. The practice of placing published research papers behind a paywall means many of the database searching software programs will only scan the abstract and titles of the article to determine if the document is relevant to the search keywords the reader is using. Therefore, when writing a manuscript, it is important to write the abstract in a way that ensures both the readers and search engines will be able to find and decide if your research is relevant to their study 2 .

It would not be wrong to say that the title, abstract and keywords operate in a manner comparable to a chain reaction. Once the keywords have helped people find the research paper and an effective title has successfully captured and drawn the readers’ attention, it is up to the abstract of the research paper to further trigger the readers’ interest and maintain their curiosity. This functional advantage alone serves to make an abstract an indispensable component within the research paper format 3 that deserves your complete attention when writing a manuscript.

As you proceed with the steps to writing a manuscript, keep in mind the recommended paper length and mould the structure of your manuscript taking into account the specific guidelines of the journal you are submitting to. Most scientific journals have evolved a distinctive style, structure, and organization. One of the top tips for writing a manuscript would be to use concise sentences and simple straightforward language in a consistent manner throughout the manuscript to convey the details of your research.

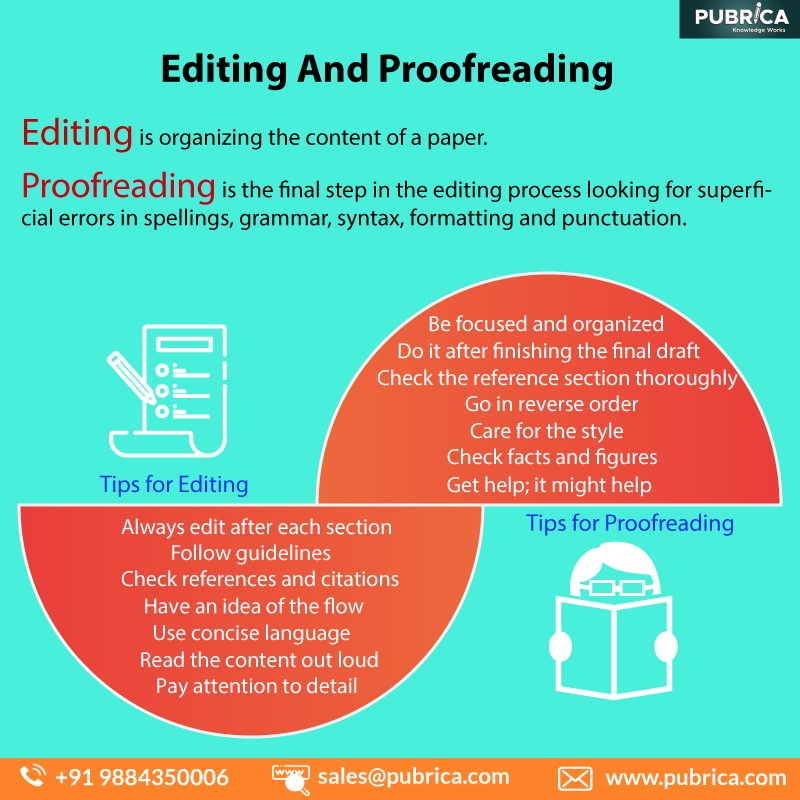

Once all the material necessary for submission has been put together, go through the manuscript with a fresh mind so that you can identify errors and gaps. According to Peter Thrower, Editor-in-Chief of Carbon , one of the top reasons for manuscript rejection is poor language comprehension. Incorrect usage of words, grammar and spelling errors, and flaws in sentence construction are certain to lead to rejection. Authors also often overlook checks to ensure a coherent transition between sections when writing a manuscript. Proofreading is, therefore, a must before submitting your manuscript for publication. Double-check the data and figures and read the manuscript out loud – this helps to weed out possible grammatical errors.

You could request colleagues or fellow researchers to go through your manuscript before submission but, if they are not experts in the same field, they may miss out on errors. In such cases, you may want to consider using professional academic editing services to help you improve sentence structure, grammar, word choice, style, logic and flow to create a polished manuscript that has a 24% greater chance of journal acceptance 4.

Once you are done writing a manuscript as per your target journal, we recommend doing a comprehensive set of submission readiness checks to ensure your paper is structurally sound, complete with all the relevant sections, and is devoid of language errors. Most importantly, you need to check for any accidental or unintentional plagiarism – i.e., not correctly citing, paraphrasing or quoting another’s work – which is considered a copyright infringement by the journal, can not only lead to rejection, but also stir up trouble for you and cause irreversible damage to your reputation and career. Also make sure you have all the ethical declarations in place when writing a manuscript, such as conflicts of interest and compliance approvals for studies involving human or animal participants.

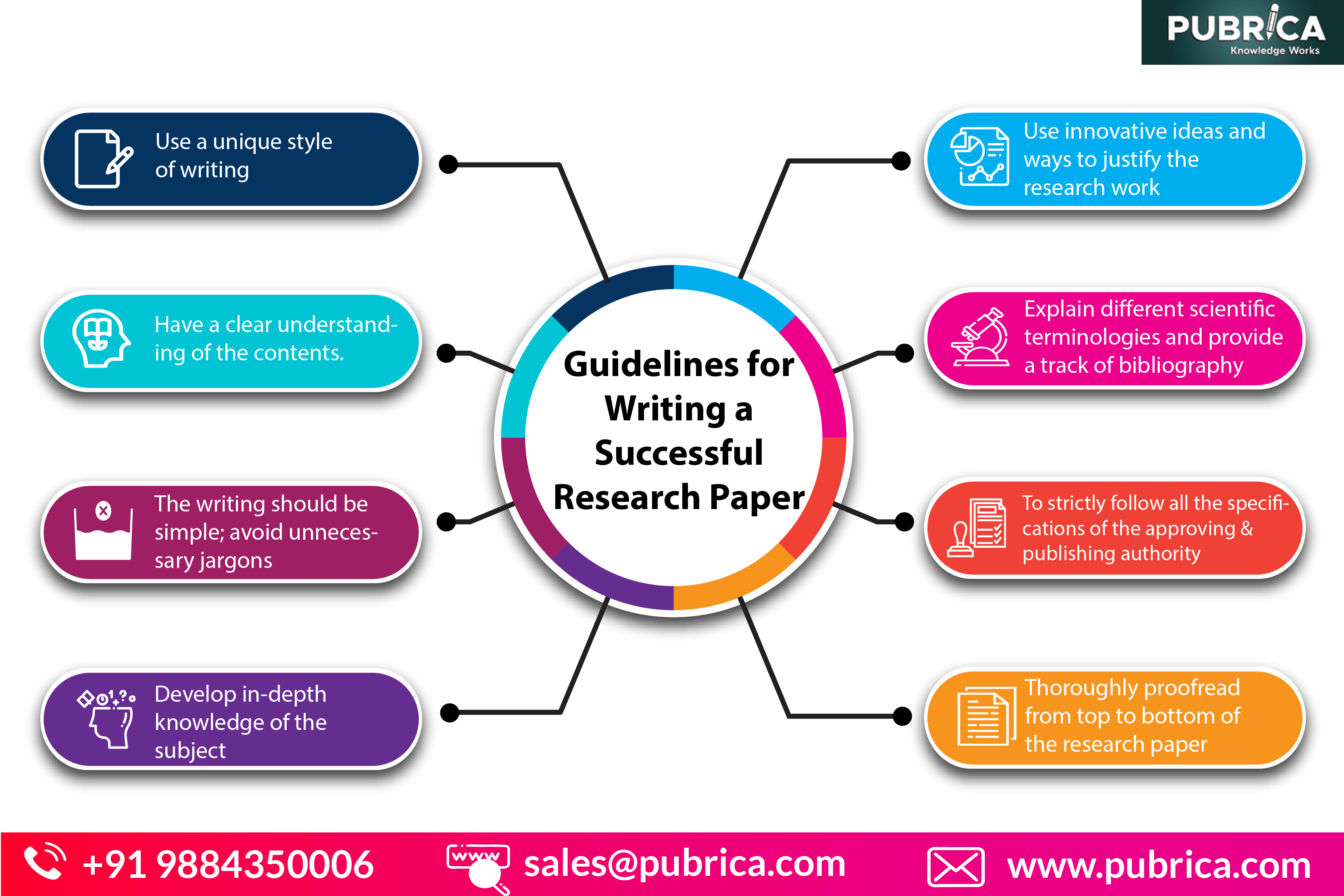

To conclude, whenever you find yourself wondering – how to write a manuscript for publication – make sure you check the following points:

- Is your research paper complete, optimized and submission ready?

- Have all authors agreed the content of the submitted manuscript?

- Is your paper aligned with your target journals publication policies?

- Have you created a winning submission package, with all the necessary details?

- Does it include a persuasive cover letter that showcases your research?

Writing a manuscript and getting your work published is an important step in your career as it introduces your research to a wide audience. If you follow our simple manuscript writing guide, you will have the base to create a winning manuscript, with a great chance at acceptance. If you face any hurdles or need support along the way, be sure to explore these bite-sized learning modules on research writing , designed by researchers, for researchers. And once you have mastered the tips for writing a research paper, and crafting a great submission package, use the comprehensive AI-assisted manuscript evaluation to avoid errors that lead to desk rejection and optimize your paper for submission to your target journal.

- Helen Eassom, 5 Options to Consider After Article Rejection. The Wiley Network. Retrieved from https://www.wiley.com/network/researchers/submission-and-navigating-peer-review/5-options-to-consider-after-article-rejection

- Jeremy Dean Chapnick, The abstract and title page. AME Medical Journal, Vol 4, 2019. Retrieved from http://amj.amegroups.com/article/view/4965/html

- Velany Rodrigues, How to write an effective title and abstract and choose appropriate keywords. Editage Insights, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.editage.com/insights/how-to-write-an-effective-title-and-abstract-and-choose-appropriate-keywords

- New Editage Report Shows That Pre-Submission Language Editing Can Improve Acceptance Rates of Manuscripts Written by Non-Native English-Speaking Researchers. PR Newswire, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-editage-report-shows-that-pre-submission-language-editing-can-improve-acceptance-rates-of-manuscripts-written-by-non-native-english-speaking-researchers-300833765.html#https%3A%2F%2Fwww.prnewswire.com%3A443

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What is Thematic Analysis and How to Do It (with Examples)

What Skills are Required for Academic Writing

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- About This Blog

- Official PLOS Blog

- EveryONE Blog

- Speaking of Medicine

- PLOS Biologue

- Absolutely Maybe

- DNA Science

- PLOS ECR Community

- All Models Are Wrong

- About PLOS Blogs

A Brief Guide To Writing Your First Scientific Manuscript

I’ve had the privilege of writing a few manuscripts in my research career to date, and helping trainees write them. It’s hard work, but planning and organization helps. Here’s some thoughts on how to approach writing manuscripts based on original biomedical research.

Getting ready to write

Involve your principal investigator (PI) early and throughout the process. It’s our job to help you write!

Write down your hypothesis/research question. Everything else will be spun around this.

Gather your proposed figures and tables in a sequence that tells a story. This will form the basis of your Results section. Write bulleted captions for the figures/tables, including a title that explains the key finding for each figure/table, an explanation of experimental groups and associated symbols/labels, and details on biological and technical replicates and statements (such as “one of four representative experiments are shown.”)

Generate a bulleted outline of the major points for each section of the manuscript. This depends on the journal, but typically, and with minor variations: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion. Use Endnote, Reference Manager, Mendeley, or other citation software to start inserting references to go with bullets. Decide from the beginning what word processing software you’ll use (Word, Google Docs, etc.). Google Docs can be helpful for maintaining a single version of the manuscript, but citation software often doesn’t play well with Google Docs (whereas most software options can automatically update citation changes in Word). Here’s what should go in each of these sections:

Introduction: What did you study, and why is it important? What is your hypothesis/research question?

Methods: What techniques did you use? Each technique should be its own bullet, with sub-bullets for key details. If you used animal or human subjects, include a bullet on ethics approval. Important methodologies and materials, i.e., blinding for subjective analyses, full names of cell lines/strains/reagents and your commercial/academic sources for them.

Results: What were your findings? Each major finding should be its own bullet, with sub-bullets going into more detail for each major finding. These bullets should refer to your figures.

Discussion: Summarize your findings in the context of prior work. Discuss possible interpretations. It is important to include a bullet describing the limitations of the presented work. Mention possible future directions.

Now read the entire outline (including the figures). Is it a complete story? If so, you’re ready to prepare for submission. If not, you should have a good idea of what it will take to finish the manuscript.

Writing your manuscript

You first need to decide where you want to submit your manuscript. I like to consider my ideal target audience. I also like to vary which journals I publish in, both to broaden the potential readers of my papers and to avoid the appearance of having an unfair “inside connection” to a given journal. Your academic reputation is priceless.

Once you’ve chosen your journal, look at the journal’s article types. Decide which article type you would like to submit and reformat your outline according to the journal’s standards (including citation style).

Convert your outline (including the figure captions) to complete sentences. Don’t focus on writing perfect prose for the first draft. Write your abstract after the first draft is completed. Make sure the manuscript conforms to the target journal’s word and figure limits.

Discuss all possible authors with your PI. If the study involved many people, create a table of possible authors showing their specific contributions to the manuscript. (This is helpful to do in any case as many journals now require this information.) Assigning authorship is sometimes complicated, but keep in mind that the Acknowledgements can be used to recognize those who made minor contributions (including reading the manuscript to provide feedback). “Equal contribution” authorship positions for the first and last authors is a newer option for a number of journals. An alternative is to generate the initial outline or first draft with the help of co-authors. This can take a lot more work and coordination, but may make sense for highly collaborative and large manuscripts.

Decide with your PI who will be corresponding author. Usually you or the PI.

Circulate the manuscript draft to all possible authors. Thank them for their prior and ongoing support. Inform your co-authors where you would like to send the manuscript and why. Give them a reasonable deadline to provide feedback (minimum of a few weeks). If you use Microsoft Word, ask your co-authors to use track changes.

Collate comments from your co-authors. The Combine Documents function in Word can be very helpful. Consider reconciling all comments and tracked changes before circulating another manuscript draft so that co-authors can read a “clean” copy. Repeat this process until you and your PI (and co-authors) are satisfied that the manuscript is ready for submission.

Some prefer to avoid listing authors on manuscript drafts until the final version is generated because the relative contributions of authors can shift during manuscript preparation.

Submit your manuscript

Write a cover letter for your manuscript. Put it on institutional letterhead, if you are permitted by the journal’s submission system. This makes the cover letter, and by extension, the manuscript, more professional. Some journals have required language for cover letters regarding simultaneous submissions to other journals. It’s common for journals to require that cover letters include a rationale explaining the impact and findings of the manuscript. If you need to do this, include key references and a citation list at the end of the cover letter.

Most journals will require you to provide keywords, and/or to choose subject areas related to the manuscript. Be prepared to do so.

Conflicts of interest should be declared in the manuscript, even if the journal does not explicitly request this. Ask your co-authors about any such potential conflicts.

Gather names and official designations of any grants that supported the work described in your manuscript. Ask your co-authors and your PI. This is very important for funding agencies such as the NIH, which scrutinize the productivity of their funded investigators and take this into account when reviewing future grants.

It’s common for journals to allow you to suggest an editor to handle your manuscript. Editors with expertise in your area are more likely to be able to identify and recruit reviewers who are also well-versed in the subject matter of your manuscript. Discuss this with your PI and co-authors.

Likewise, journals often allow authors to suggest reviewers. Some meta-literature indicates that manuscripts with suggested reviewers have an overall higher acceptance rate. It also behooves you to have expert reviewers that can evaluate your manuscript fairly, but also provide feedback that can improve your paper if revisions are recommended. Avoid suggesting reviewers at your own institution or who have recently written papers or been awarded grants with you. Savvy editors look for these types of relationships between reviewers and authors, and will nix a suggested reviewer with any potential conflict of interest. Discuss suggested reviewers with your PI and co-authors.

On the flip side, many journals will allow you to list opposed reviewers. If you believe that someone specific will provide a negatively biased review for non-scientific reasons, that is grounds for opposing them as your manuscript’s reviewer. In small fields, it may not be possible to exclude reviewers and still undergo expert peer review. Definitely a must-discuss with your PI and co-authors.

Generate a final version of the manuscript. Most journals use online submission systems that mandate uploading individual files for the manuscript, cover letter, etc. You may have to use pdf converting software (i.e., Adobe Acrobat) to change Word documents to pdf’s, or to combine documents into a single pdf. Review the final version, including the resolution and appearance of figures. Make sure that no edges of text or graphics near page margins are cut off (Adobe Acrobat sometimes does this with Microsoft Word). Send the final version to your PI and co-authors. Revise any errors. Then submit! Good luck!

Edited by Bill Sullivan, PhD, Indiana University School of Medicine.

Michael Hsieh is the Stirewalt Scientific Director of the Biomedical Research Institute and an Associate Professor at the George Washington University, where he studies host-pathogen interactions in the urinary tract. Michael has published over 90 peer-reviewed scientific papers. His work has been featured on PBS and in the New York Times.

Your article is wonderful. just read it. you advise very correctly. I am an experienced writer. I write articles on various scientific topics. and even I took some information for myself, who I have not used before. Your article will help many novice writers. I’m sure of it. You very well described all the points of your article. I completely agree with them. most difficult to determine the target audience. Thanks to your article, everyone who needs some kind of help can get it by reading your article. Thanks you

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name and email for the next time I comment.

Written by Jessica Rech an undergraduate student at IUPUI and coauthored by Brandi Gilbert, director of LHSI. I am an undergraduate student…

As more learning occurs online and at home with the global pandemic, keeping students engaged in learning about science is a challenge…

By Brad Parks A few years back, while driving to my favorite daily writing haunt, the local radio station spit out one…

- SpringerLink shop

Writing a journal manuscript

Publishing your results is a vital step in the research lifecycle and in your career as a scientist. Publishing papers is necessary to get your work seen by the scientific community, to exchange your ideas globally and to ensure you receive the recognition for your results. The following information is designed to help you write the best paper possible by providing you with points to consider, from your background reading and study design to structuring your manuscript and figure preparation.

By the end of the tutorial you should know on how to:

- prepare prior to starting your research

- structure your manuscript and what to include in each section

- get the most out of your tables and figures so that they clearly represent your most important results.

You will also have the opportunity to test your learning by completing a quiz at the end.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 28 February 2018

- Correction 16 March 2018

How to write a first-class paper

- Virginia Gewin 0

Virginia Gewin is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Illustration adapted from Aron Vellekoop Leon/Getty

Manuscripts may have a rigidly defined structure, but there’s still room to tell a compelling story — one that clearly communicates the science and is a pleasure to read. Scientist-authors and editors debate the importance and meaning of creativity and offer tips on how to write a top paper.

Keep your message clear

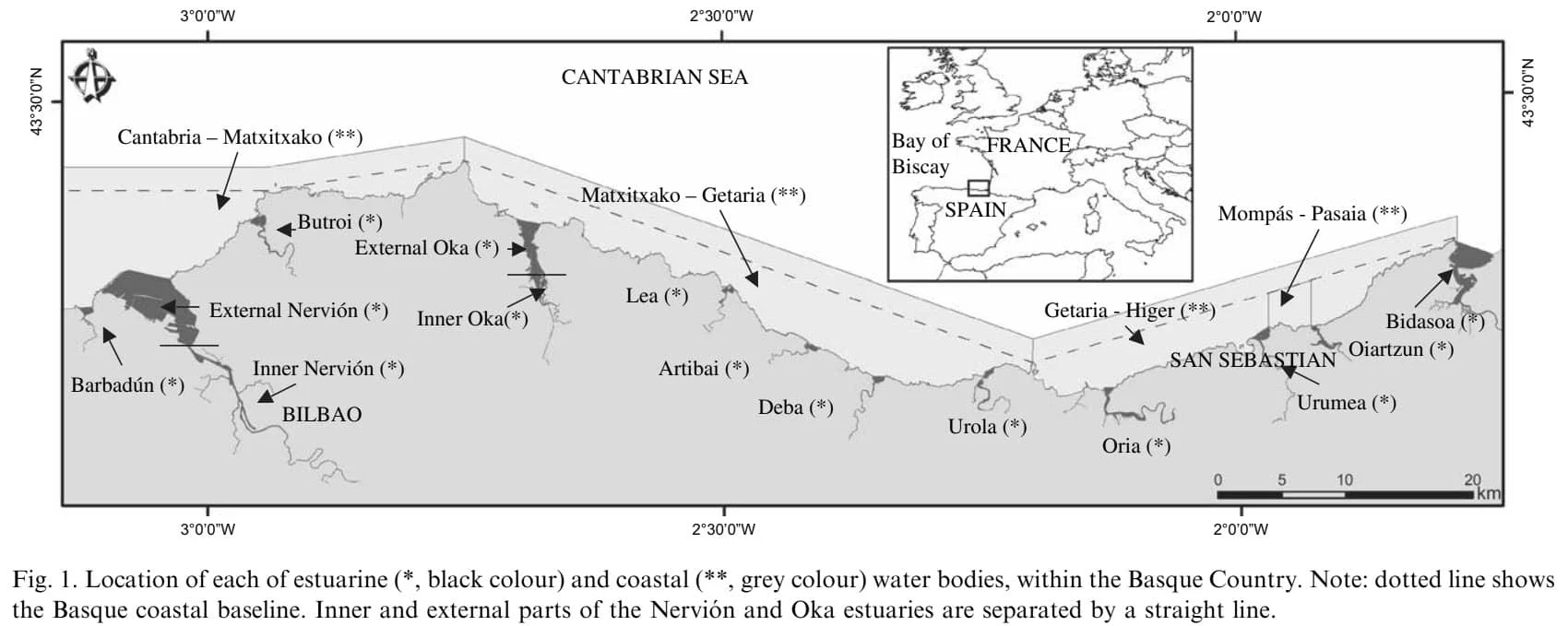

Angel Borja, marine scientist at AZTI-Tecnalia, a producer of sustainable business services and goods, Pasaia, Spain; journal editor; author of a series on preparing a manuscript .

Think about the message you want to give to readers. If that is not clear, misinterpretations may arise later. And a clear message is even more important when there is a multidisciplinary group of authors, which is increasingly common. I encourage groups to sit together in person and seek consensus — not only in the main message, but also in the selection of data, the visual presentation and the information necessary to transmit a strong message.

The most important information should be in the main text. To avoid distraction, writers should put additional data in the supplementary material.

Countless manuscripts are rejected because the discussion section is so weak that it’s obvious the writer does not clearly understand the existing literature. Writers should put their results into a global context to demonstrate what makes those results significant or original.

There is a narrow line between speculation and evidence-based conclusions. A writer can speculate in the discussion — but not too much. When the discussion is all speculation, it’s no good because it is not rooted in the author’s experience. In the conclusion, include a one- or two-sentence statement on the research you plan to do in the future and on what else needs to be explored.

Create a logical framework

Brett Mensh, scientific adviser, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Research Campus, Ashburn, Virginia; consultant, science communications.

Structure is paramount. If you don’t get the structure right, you have no hope.

I co-wrote a paper ( B. Mensh and K. Kording PLoS Comput. Biol. http://doi.org/ckqp; 2017 ) that lays out structural details for using a context–content–conclusion scheme to build a core concept. It is one of the most highly tweeted papers so far. In each paragraph, the first sentence defines the context, the body contains the new idea and the final sentence offers a conclusion. For the whole paper, the introduction sets the context, the results present the content and the discussion brings home the conclusion.

It’s crucial to focus your paper on a single key message, which you communicate in the title. Everything in the paper should logically and structurally support that idea. It can be a delight to creatively bend the rules, but you need to know them first.

You have to guide the naive reader to the point at which they are ready to absorb what you did. As a writer, you need to detail the problem. I won’t know why I should care about your experiment until you tell me why I should.

State your case with confidence

Dallas Murphy, book author, New York City; instructor, writing workshops for scientists in Germany, Norway and the United States.

Clarity is the sole obligation of the science writer, yet I find constantly that the ‘What’s new’ element is buried. Answering one central question — What did you do? — is the key to finding the structure of a piece. Every section of the manuscript needs to support that one fundamental idea.

There is a German concept known as the ‘red thread’ , which is the straight line that the audience follows from the introduction to the conclusion. In science, ‘What’s new and compelling?’ is the red thread. It’s the whole reason for writing the paper. Then, once that’s established, the paragraphs that follow become the units of logic that comprise the red thread.

Scientific authors are often scared to make confident statements with muscularity. The result is turgid or obfuscatory writing that sounds defensive, with too many caveats and long lists — as if the authors are writing to fend off criticism that hasn’t been made yet. When they write for a journal gatekeeper rather than for a human being, the result is muddy prose.

Examples such as this are not uncommon: “Though not inclusive, this paper provides a useful review of the well-known methods of physical oceanography using as examples various research that illustrates the methodological challenges that give rise to successful solutions to the difficulties inherent in oceanographic research.” Why not this instead: “We review methods of oceanographic research with examples that reveal specific challenges and solutions”?

And if the prose muddies the science, the writer has not only failed to convey their idea, but they’ve also made the reader work so hard that they have alienated him or her. The reader’s job is to pay attention and remember what they read. The writer’s job is to make those two things easy to do. I encourage scientists to read outside their field to better appreciate the craft and principles of writing.

Beware the curse of ‘zombie nouns’

Zoe Doubleday, ecologist, University of Adelaide, Australia; co-author of a paper on embracing creativity and writing accessible prose in scientific publications.

Always think of your busy, tired reader when you write your paper — and try to deliver a paper that you would enjoy reading yourself.

Why does scientific writing have to be stodgy, dry and abstract? Humans are story-telling animals. If we don’t engage that aspect of ourselves, it’s hard to absorb the meaning of what we’re reading. Scientific writing should be factual, concise and evidence-based, but that doesn’t mean it can’t also be creative — told in a voice that is original — and engaging ( Z. A. Doubleday et al. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32, 803–805; 2017 ). If science isn’t read, it doesn’t exist.

One of the principal problems with writing a manuscript is that your individual voice is stamped out. Writers can be stigmatized by mentors, manuscript reviewers or journal editors if they use their own voice. Students tell me they are inspired to write, but worry that their adviser won’t be supportive of creativity. It is a concern. We need to take a fresh look at the ‘official style’ — the dry, technical language that hasn’t evolved in decades.

Author Helen Sword coined the phrase ‘zombie nouns’ to describe terms such as ‘implementation’ or ‘application’ that suck the lifeblood out of active verbs. We should engage readers’ emotions and avoid formal, impersonal language. Still, there’s a balance. Don’t sensationalize the science. Once the paper has a clear message, I suggest that writers try some vivid language to help to tell the story. For example, I got some pushback on the title of one of my recent papers: ‘ Eight habitats, 38 threats, and 55 experts: Assessing ecological risk in a multi-use marine region ’. But, ultimately, the editors let me keep it. There’s probably less resistance out there than people might think.

Recently, after hearing me speak on this topic, a colleague mentioned that she had just rejected a review paper because she felt the style was too non-scientific. She admitted that she felt she had made the wrong decision and would try to reverse it.

Prune that purple prose

Peter Gorsuch, managing editor, Nature Research Editing Service, London; former plant biologist.

Writers must be careful about ‘creativity’. It sounds good, but the purpose of a scientific paper is to convey information. That’s it. Flourishes can be distracting. Figurative language can also bamboozle a non-native English speaker. My advice is to make the writing only as complex as it needs to be.

That said, there are any number of ways of writing a paper that are far from effective. One of the most important is omitting crucial information from the methods section. It’s easy to do, especially in a complicated study, but missing information can make it difficult, if not impossible, to reproduce the study. That can mean the research is a dead end.

It’s also important that the paper’s claims are consistent with collected evidence. At the same time, authors should avoid being over-confident in their conclusions.

Editors and peer reviewers are looking for interesting results that are useful to the field. Without those, a paper might be rejected. Unfortunately, authors tend to struggle with the discussion section. They need to explain why the findings are interesting and how they affect a wider understanding of the topic. Authors should also reassess the existing literature and consider whether their findings open the door for future work. And, in making clear how robust their findings are, they must convince readers that they’ve considered alternative explanations.

Aim for a wide audience

Stacy Konkiel, director of research and education at Altmetric, London, which scores research papers on the basis of their level of digital attention.

There have been no in-depth studies linking the quality of writing to a paper’s impact, but a recent one ( N. Di Girolamo and R. M. Reynders J. Clin. Epidemiol. 85, 32–36; 2017 ) shows that articles with clear, succinct, declarative titles are more likely to get picked up by social media or the popular press.

Those findings tie in with my experience. My biggest piece of advice is to get to the point. Authors spend a lot of time setting up long-winded arguments to knock down possible objections before they actually state their case. Make your point clearly and concisely — if possible in non-specialist language, so that readers from other fields can quickly make sense of it.

If you write in a way that is accessible to non-specialists, you are not only opening yourself up to citations by experts in other fields, but you are also making your writing available to laypeople, which is especially important in the biomedical fields. My Altmetric colleague Amy Rees notes that she sees a trend towards academics being more deliberate and thoughtful in how they disseminate their work. For example, we see more scientists writing lay summaries in publications such as The Conversation , a media outlet through which academics share news and opinions.

Nature 555 , 129-130 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02404-4

Interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 16 March 2018 : This article should have made clear that Altmetric is part of Digital Science, a company owned by Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which is also the majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature. Nature Research Editing Services is also owned by Springer Nature.

Related Articles

We are junior scientists from emerging economies — the world needs more researchers like us solving global problems

Career Column 26 JUL 24

Why you should perform a premortem on your research

Career Column 24 JUL 24

Science must protect thinking time in a world of instant communication

Editorial 24 JUL 24

Retraction notices are getting clearer — but progress is slow

News 26 JUL 24

So you got a null result. Will anyone publish it?

News Feature 24 JUL 24

Hijacked journals are still a threat — here’s what publishers can do about them

Nature Index 23 JUL 24

Stadtman Investigator Search 2024-2025

Stadtman Investigator Search 2024-2025 Deadline: September 30, 2024 The National Institutes of Health, the U.S. government’s premier biomedical and...

Bethesda, Maryland

National Institute of Health- Office of Intramural Research

Research Manager, Open Access

The Research Manager is a great opportunity for someone with experience of policy and open access to join Springer Nature.

London, Berlin or New York (Hybrid Working)

Springer Nature Ltd

Postdoctoral Research Scientist

Computational Postdoctoral Research Scientist in Neurodegenerative Disease

New York City, New York (US)

Columbia University Department of Pathology

Associate or Senior Editor (Chemical Engineering), Nature Sustainability

Associate or Senior Editor (Chemical engineering), Nature Sustainability Locations: New York, Philadelphia, Berlin, or Heidelberg Closing date: Aug...

Postdoctoral Research Scientist - Mouse Model

The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Center for Precision Psychiatry & Mental Health is seeking a Postdoctoral Research Scientist for the Mouse Model.

Columbia University Irving Medical Center / Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

278k Accesses

15 Citations

712 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

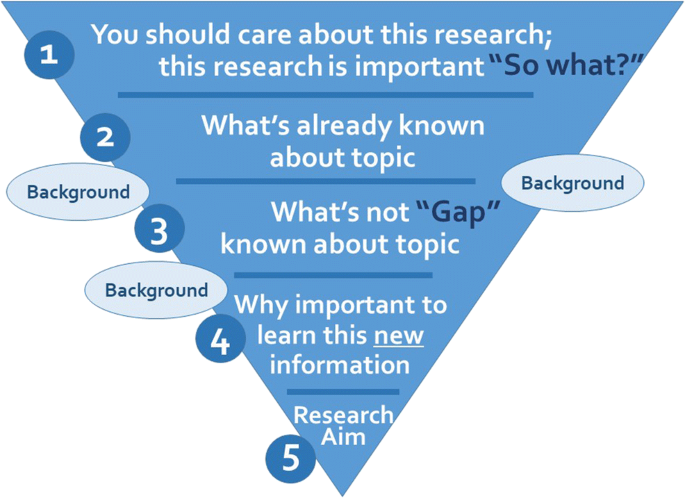

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Discussion Section

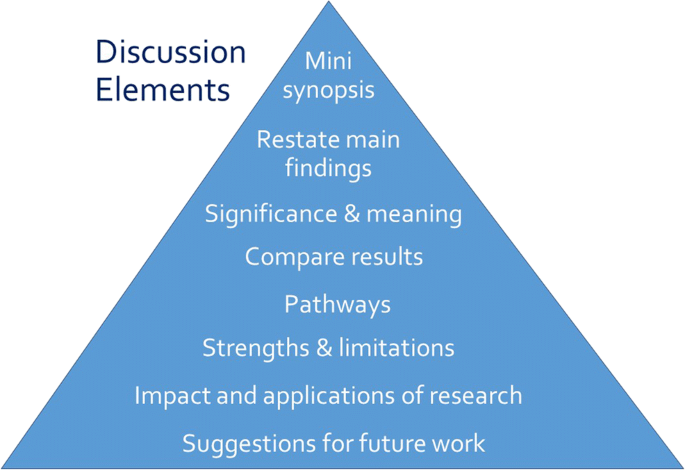

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

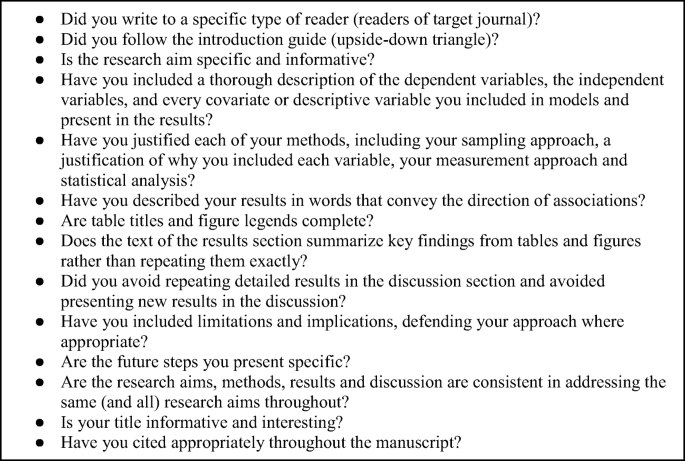

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

11 steps to structuring a science paper editors will take seriously

April 5, 2021 | 18 min read

By Angel Borja, PhD

Editor’s note: This 2014 post conveys the advice of a researcher sharing his experience and does not represent Elsevier’s policy. However, in response to your feedback, we worked with him to update this post so it reflects our practices. For example, since it was published, we have worked extensively with researchers to raise visibility of non-English language research – July 10, 2019

Update: In response to your feedback, we have reinstated the original text so you can see how it was revised. – July 11, 2019

How to prepare a manuscript for international journals — Part 2

In this monthly series, Dr. Angel Borja draws on his extensive background as an author, reviewer and editor to give advice on preparing the manuscript (author's view), the evaluation process (reviewer's view) and what there is to hate or love in a paper (editor's view).

This article is the second in the series. The first article was: "Six things to do before writing your manuscript."

When you organize your manuscript, the first thing to consider is that the order of sections will be very different than the order of items on you checklist.

An article begins with the Title, Abstract and Keywords.

The article text follows the IMRAD format opens in new tab/window , which responds to the questions below:

I ntroduction: What did you/others do? Why did you do it?

M ethods: How did you do it?

R esults: What did you find?

D iscussion: What does it all mean?

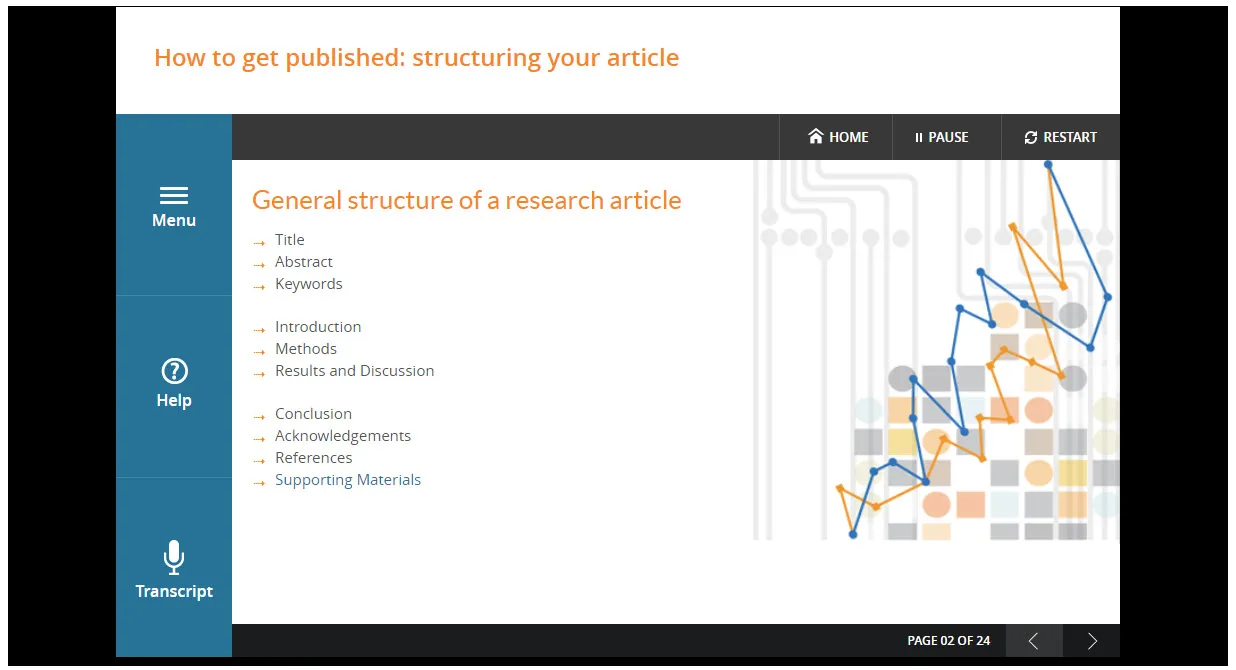

The main text is followed by the Conclusion, Acknowledgements, References and Supporting Materials.

While this is the published structure, however, we often use a different order when writing.

General strcuture of a research article. Watch a related tutorial on Researcher Academy opens in new tab/window .

Steps to organizing your manuscript

Prepare the figures and tables .

Write the Methods .

Write up the Results .

Write the Discussion . Finalize the Results and Discussion before writing the introduction. This is because, if the discussion is insufficient, how can you objectively demonstrate the scientific significance of your work in the introduction?

Write a clear Conclusion .

Write a compelling Introduction .

Write the Abstract .

Compose a concise and descriptive Title .

Select Keywords for indexing.

Write the Acknowledgements .

Write up the References .

Next, I'll review each step in more detail. But before you set out to write a paper, there are two important things you should do that will set the groundwork for the entire process.

The topic to be studied should be the first issue to be solved. Define your hypothesis and objectives (These will go in the Introduction.)

Review the literature related to the topic and select some papers (about 30) that can be cited in your paper (These will be listed in the References.)

Finally, keep in mind that each publisher has its own style guidelines and preferences, so always consult the publisher's Guide for Authors.

Step 1: Prepare the figures and tables

Remember that "a figure is worth a thousand words." Hence, illustrations, including figures and tables, are the most efficient way to present your results. Your data are the driving force of the paper, so your illustrations are critical!

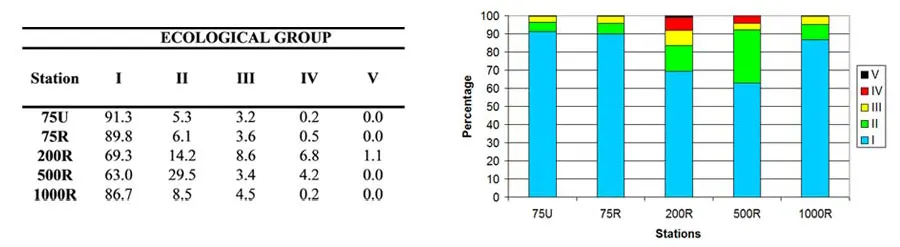

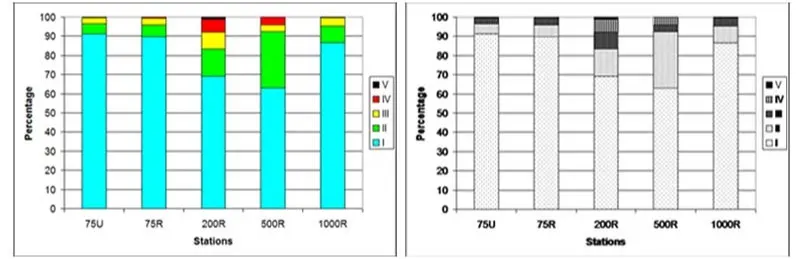

How do you decide between presenting your data as tables or figures? Generally, tables give the actual experimental results, while figures are often used for comparisons of experimental results with those of previous works, or with calculated/theoretical values (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An example of the same data presented as table or as figure. Depending on your objectives, you can show your data either as table (if you wish to stress numbers) or as figure (if you wish to compare gradients).

Whatever your choice is, no illustrations should duplicate the information described elsewhere in the manuscript.

Another important factor: figure and table legends must be self-explanatory (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Figures must be self-explanatory.

When presenting your tables and figures, appearances count! To this end:

Avoid crowded plots (Figure 3), using only three or four data sets per figure; use well-selected scales.

Think about appropriate axis label size

Include clear symbols and data sets that are easy to distinguish.

Never include long boring tables (e.g., chemical compositions of emulsion systems or lists of species and abundances). You can include them as supplementary material.

Figure 3. Don't clutter your charts with too much data.

If you are using photographs, each must have a scale marker, or scale bar, of professional quality in one corner.

In photographs and figures, use color only when necessary when submitting to a print publication. If different line styles can clarify the meaning, never use colors or other thrilling effects or you will be charged with expensive fees. Of course, this does not apply to online journals. For many journals, you can submit duplicate figures: one in color for the online version of the journal and pdfs, and another in black and white for the hardcopy journal (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Using black and white can save money.

Another common problem is the misuse of lines and histograms. Lines joining data only can be used when presenting time series or consecutive samples data (e.g., in a transect from coast to offshore in Figure 5). However, when there is no connection between samples or there is not a gradient, you must use histograms (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Use the right kind of chart for your data.

Sometimes, fonts are too small for the journal. You must take this into account, or they may be illegible to readers (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Figures are not eye charts - make them large enough too read

Finally, you must pay attention to the use of decimals, lines, etc.

Step 2: Write the Methods

This section responds to the question of how the problem was studied. If your paper is proposing a new method, you need to include detailed information so a knowledgeable reader can reproduce the experiment.

However, do not repeat the details of established methods; use References and Supporting Materials to indicate the previously published procedures. Broad summaries or key references are sufficient.

Reviewers will criticize incomplete or incorrect methods descriptions and may recommend rejection, because this section is critical in the process of reproducing your investigation. In this way, all chemicals must be identified. Do not use proprietary, unidentifiable compounds.

To this end, it's important to use standard systems for numbers and nomenclature. For example:

For chemicals, use the conventions of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry opens in new tab/window and the official recommendations of the IUPAC–IUB Combined Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature opens in new tab/window .

For species, use accepted taxonomical nomenclature ( WoRMS: World Register of Marine Species opens in new tab/window , ERMS: European Register of Marine Species opens in new tab/window ), and write them always in italics.

For units of measurement, follow the International System of Units (SI).

Present proper control experiments and statistics used, again to make the experiment of investigation repeatable.

List the methods in the same order they will appear in the Results section, in the logical order in which you did the research:

Description of the site

Description of the surveys or experiments done, giving information on dates, etc.

Description of the laboratory methods, including separation or treatment of samples, analytical methods, following the order of waters, sediments and biomonitors. If you have worked with different biodiversity components start from the simplest (i.e. microbes) to the more complex (i.e. mammals)

Description of the statistical methods used (including confidence levels, etc.)

In this section, avoid adding comments, results, and discussion, which is a common error.

Length of the manuscript

Again, look at the journal's Guide for Authors, but an ideal length for a manuscript is 25 to 40 pages, double spaced, including essential data only. Here are some general guidelines:

Title: Short and informative

Abstract: 1 paragraph (<250 words)

Introduction: 1.5-2 pages

Methods: 2-3 pages

Results: 6-8 pages

Discussion: 4-6 pages

Conclusion: 1 paragraph

Figures: 6-8 (one per page)

Tables: 1-3 (one per page)

References: 20-50 papers (2-4 pages)

Step 3: Write up the Results

This section responds to the question "What have you found?" Hence, only representative results from your research should be presented. The results should be essential for discussion.

However, remember that most journals offer the possibility of adding Supporting Materials, so use them freely for data of secondary importance. In this way, do not attempt to "hide" data in the hope of saving it for a later paper. You may lose evidence to reinforce your conclusion. If data are too abundant, you can use those supplementary materials.

Use sub-headings to keep results of the same type together, which is easier to review and read. Number these sub-sections for the convenience of internal cross-referencing, but always taking into account the publisher's Guide for Authors.

For the data, decide on a logical order that tells a clear story and makes it and easy to understand. Generally, this will be in the same order as presented in the methods section.

An important issue is that you must not include references in this section; you are presenting your results, so you cannot refer to others here. If you refer to others, is because you are discussing your results, and this must be included in the Discussion section.

Statistical rules

Indicate the statistical tests used with all relevant parameters: e.g., mean and standard deviation (SD): 44% (±3); median and interpercentile range: 7 years (4.5 to 9.5 years).

Use mean and standard deviation to report normally distributed data.

Use median and interpercentile range to report skewed data.

For numbers, use two significant digits unless more precision is necessary (2.08, not 2.07856444).

Never use percentages for very small samples e.g., "one out of two" should not be replaced by 50%.

Step 4: Write the Discussion

Here you must respond to what the results mean. Probably it is the easiest section to write, but the hardest section to get right. This is because it is the most important section of your article. Here you get the chance to sell your data. Take into account that a huge numbers of manuscripts are rejected because the Discussion is weak.

You need to make the Discussion corresponding to the Results, but do not reiterate the results. Here you need to compare the published results by your colleagues with yours (using some of the references included in the Introduction). Never ignore work in disagreement with yours, in turn, you must confront it and convince the reader that you are correct or better.

Take into account the following tips:

Avoid statements that go beyond what the results can support.

Avoid unspecific expressions such as "higher temperature", "at a lower rate", "highly significant". Quantitative descriptions are always preferred (35ºC, 0.5%, p<0.001, respectively).

Avoid sudden introduction of new terms or ideas; you must present everything in the introduction, to be confronted with your results here.

Speculations on possible interpretations are allowed, but these should be rooted in fact, rather than imagination. To achieve good interpretations think about:

How do these results relate to the original question or objectives outlined in the Introduction section?

Do the data support your hypothesis?

Are your results consistent with what other investigators have reported?

Discuss weaknesses and discrepancies. If your results were unexpected, try to explain why

Is there another way to interpret your results?

What further research would be necessary to answer the questions raised by your results?

Explain what is new without exaggerating

Revision of Results and Discussion is not just paper work. You may do further experiments, derivations, or simulations. Sometimes you cannot clarify your idea in words because some critical items have not been studied substantially.

Step 5: Write a clear Conclusion

This section shows how the work advances the field from the present state of knowledge. In some journals, it's a separate section; in others, it's the last paragraph of the Discussion section. Whatever the case, without a clear conclusion section, reviewers and readers will find it difficult to judge your work and whether it merits publication in the journal.

A common error in this section is repeating the abstract, or just listing experimental results. Trivial statements of your results are unacceptable in this section.

You should provide a clear scientific justification for your work in this section, and indicate uses and extensions if appropriate. Moreover, you can suggest future experiments and point out those that are underway.

You can propose present global and specific conclusions, in relation to the objectives included in the introduction

Step 6: Write a compelling Introduction

This is your opportunity to convince readers that you clearly know why your work is useful.

A good introduction should answer the following questions:

What is the problem to be solved?

Are there any existing solutions?

Which is the best?

What is its main limitation?

What do you hope to achieve?

Editors like to see that you have provided a perspective consistent with the nature of the journal. You need to introduce the main scientific publications on which your work is based, citing a couple of original and important works, including recent review articles.

However, editors hate improper citations of too many references irrelevant to the work, or inappropriate judgments on your own achievements. They will think you have no sense of purpose.

Here are some additional tips for the introduction:

Never use more words than necessary (be concise and to-the-point). Don't make this section into a history lesson. Long introductions put readers off.

We all know that you are keen to present your new data. But do not forget that you need to give the whole picture at first.

The introduction must be organized from the global to the particular point of view, guiding the readers to your objectives when writing this paper.

State the purpose of the paper and research strategy adopted to answer the question, but do not mix introduction with results, discussion and conclusion. Always keep them separate to ensure that the manuscript flows logically from one section to the next.

Hypothesis and objectives must be clearly remarked at the end of the introduction.

Expressions such as "novel," "first time," "first ever," and "paradigm-changing" are not preferred. Use them sparingly.

Step 7: Write the Abstract

The abstract tells prospective readers what you did and what the important findings in your research were. Together with the title, it's the advertisement of your article. Make it interesting and easily understood without reading the whole article. Avoid using jargon, uncommon abbreviations and references.

You must be accurate, using the words that convey the precise meaning of your research. The abstract provides a short description of the perspective and purpose of your paper. It gives key results but minimizes experimental details. It is very important to remind that the abstract offers a short description of the interpretation/conclusion in the last sentence.

A clear abstract will strongly influence whether or not your work is further considered.

However, the abstracts must be keep as brief as possible. Just check the 'Guide for authors' of the journal, but normally they have less than 250 words. Here's a good example on a short abstract opens in new tab/window .

In an abstract, the two whats are essential. Here's an example from an article I co-authored in Ecological Indicators opens in new tab/window :

What has been done? "In recent years, several benthic biotic indices have been proposed to be used as ecological indicators in estuarine and coastal waters. One such indicator, the AMBI (AZTI Marine Biotic Index), was designed to establish the ecological quality of European coasts. The AMBI has been used also for the determination of the ecological quality status within the context of the European Water Framework Directive. In this contribution, 38 different applications including six new case studies (hypoxia processes, sand extraction, oil platform impacts, engineering works, dredging and fish aquaculture) are presented."

What are the main findings? "The results show the response of the benthic communities to different disturbance sources in a simple way. Those communities act as ecological indicators of the 'health' of the system, indicating clearly the gradient associated with the disturbance."

Step 8: Compose a concise and descriptive title

The title must explain what the paper is broadly about. It is your first (and probably only) opportunity to attract the reader's attention. In this way, remember that the first readers are the Editor and the referees. Also, readers are the potential authors who will cite your article, so the first impression is powerful!

We are all flooded by publications, and readers don't have time to read all scientific production. They must be selective, and this selection often comes from the title.

Reviewers will check whether the title is specific and whether it reflects the content of the manuscript. Editors hate titles that make no sense or fail to represent the subject matter adequately. Hence, keep the title informative and concise (clear, descriptive, and not too long). You must avoid technical jargon and abbreviations, if possible. This is because you need to attract a readership as large as possible. Dedicate some time to think about the title and discuss it with your co-authors.

Here you can see some examples of original titles, and how they were changed after reviews and comments to them:

Original title: Preliminary observations on the effect of salinity on benthic community distribution within a estuarine system, in the North Sea

Revised title: Effect of salinity on benthic distribution within the Scheldt estuary (North Sea)

Comments: Long title distracts readers. Remove all redundancies such as "studies on," "the nature of," etc. Never use expressions such as "preliminary." Be precise.

Original title: Action of antibiotics on bacteria

Revised title: Inhibition of growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by streptomycin

Comments: Titles should be specific. Think about "how will I search for this piece of information" when you design the title.

Original title: Fabrication of carbon/CdS coaxial nanofibers displaying optical and electrical properties via electrospinning carbon

Revised title: Electrospinning of carbon/CdS coaxial nanofibers with optical and electrical properties

Comments: "English needs help. The title is nonsense. All materials have properties of all varieties. You could examine my hair for its electrical and optical properties! You MUST be specific. I haven't read the paper but I suspect there is something special about these properties, otherwise why would you be reporting them?" – the Editor-in-Chief.

Try to avoid this kind of response!

Step 9: Select keywords for indexing

Keywords are used for indexing your paper. They are the label of your manuscript. It is true that now they are less used by journals because you can search the whole text. However, when looking for keywords, avoid words with a broad meaning and words already included in the title.

Some journals require that the keywords are not those from the journal name, because it is implicit that the topic is that. For example, the journal Soil Biology & Biochemistry requires that the word "soil" not be selected as a keyword.

Only abbreviations firmly established in the field are eligible (e.g., TOC, CTD), avoiding those which are not broadly used (e.g., EBA, MMI).

Again, check the Guide for Authors and look at the number of keywords admitted, label, definitions, thesaurus, range, and other special requests.

Step 10: Write the Acknowledgements

Here, you can thank people who have contributed to the manuscript but not to the extent where that would justify authorship. For example, here you can include technical help and assistance with writing and proofreading. Probably, the most important thing is to thank your funding agency or the agency giving you a grant or fellowship.

In the case of European projects, do not forget to include the grant number or reference. Also, some institutes include the number of publications of the organization, e.g., "This is publication number 657 from AZTI-Tecnalia."

Step 11: Write up the References

Typically, there are more mistakes in the references than in any other part of the manuscript. It is one of the most annoying problems, and causes great headaches among editors. Now, it is easier since to avoid these problem, because there are many available tools.

In the text, you must cite all the scientific publications on which your work is based. But do not over-inflate the manuscript with too many references – it doesn't make a better manuscript! Avoid excessive self-citations and excessive citations of publications from the same region.

As I have mentioned, you will find the most authoritative information for each journal’s policy on citations when you consult the journal's Guide for Authors. In general, you should minimize personal communications, and be mindful as to how you include unpublished observations. These will be necessary for some disciplines, but consider whether they strengthen or weaken your paper. You might also consider articles published on research networks opens in new tab/window prior to publication, but consider balancing these citations with citations of peer-reviewed research. When citing research in languages other than English, be aware of the possibility that not everyone in the review process will speak the language of the cited paper and that it may be helpful to find a translation where possible.

You can use any software, such as EndNote opens in new tab/window or Mendeley opens in new tab/window , to format and include your references in the paper. Most journals have now the possibility to download small files with the format of the references, allowing you to change it automatically. Also, Elsevier's Your Paper Your Way program waves strict formatting requirements for the initial submission of a manuscript as long as it contains all the essential elements being presented here.

Make the reference list and the in-text citation conform strictly to the style given in the Guide for Authors. Remember that presentation of the references in the correct format is the responsibility of the author, not the editor. Checking the format is normally a large job for the editors. Make their work easier and they will appreciate the effort.

Finally, check the following:

Spelling of author names

Year of publications

Usages of "et al."

Punctuation

Whether all references are included

In my next article, I will give tips for writing the manuscript, authorship, and how to write a compelling cover letter. Stay tuned!

References and Acknowledgements

I have based this paper on the materials distributed to the attendees of many courses. It is inspired by many Guides for Authors of Elsevier journals. Some of this information is also featured in Elsevier's Publishing Connect tutorials opens in new tab/window . In addition, I have consulted several web pages: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/ opens in new tab/window , www.physics.ohio-state.edu/~wilkins/writing/index.html.