- Philippines

The Philippines Still Hasn’t Fully Reopened Its Schools Because of COVID-19. What Is This Doing to Children?

I f 17-year-old Ruzel Delaroso needs to ask her teacher a question, she can’t simply raise her hand, much less fire off an email from the kitchen table. She has to leave the modest shack that her family calls home in Januiay, a farming town in the central Philippines, and head to an area of dense shrubbery, a 10-minute walk away. There, if she’s lucky, she can pick up a phone signal and finally ask about the math problem in the self-learning materials her mother picked up from school.

“We’re so used to our teachers always being around,” Delaroso tells TIME via the same temperamental phone connection. “But now it’s harder to communicate with them.”

Her school, Calmay National High School, is among the tens of thousands of Philippine public schools shuttered since March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Delaroso is one of 1.6 billion children affected by worldwide school closures, according to a UNESCO estimate.

But while other countries have taken the opportunity to resume in-person classes, the Philippines has lagged behind. After 20 months of pandemic prevention measures, amounting to one of the world’s longest lockdowns , only 5,000 students, in just over 100 public schools, have been allowed to go back to class in a two-month trial program—a tiny fraction of the 27 million public school students who enrolled this year. The Philippines must be one of a very few countries, if not the only country, to remain so reliant on distance learning. It has become a vast experiment in life without in-person schooling.

Read More: What It’s Like Being a Teacher During the COVID-19 Pandemic

“[Education secretary Leonor Briones] always reminds us that in the past when there were military sieges, or volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, typhoons, floods, learning continued,” says education undersecretary Diosdado San Antonio.

But has it this time? Educators fear that prolonged closure is having negative effects on students’ ability to learn, impacting their futures just a time when the country needs a young, well-educated workforce to resume the impressive economic growth it was enjoying before the pandemic hit.

Globally, COVID-19 will be impacting the mental health of children and young adolescents for years to come, UNICEF warns. School shutdowns have already been blamed for a rise in dropout rates and decreased literacy, and the World Bank estimates that the number of children aged 10 and below, from low- and middle-income countries, who cannot read simple text has risen from 53% prior to the pandemic to 70% today.

If the pilot resumption of classes passes without incident, there are hopes for a wider reopening of Philippine schools. But without it, there are fears of a lost generation .

How COVID-19 impacted Philippine education

From March 2020 to September 2021, UNICEF tallied 131 million pre-tertiary students from 11 countries who had been trying to learn at home for at least three quarters of the time that they would normally have been in school. Of that number, 66 million came from just two countries where face-to-face classes were almost completely nixed: Bangladesh and the Philippines. (Bangladesh reopened its schools in September.)

Amid the initial COVID-19 surge of March 2020—just weeks shy of the end of the academic year—the Philippines stopped in-person classes for its entire cohort of public education students, which then numbered some 24.9 million according to UNESCO. The start of the new school year in September also got pushed back, as President Rodrigo Duterte imposed a “no vaccine, no classes” policy.

When schooling finally resumed in October 2020, the education department’s solution was a blend of remote-learning options: online platforms, educational TV and radio, and printed modules. But social inequalities and the lack of resources at home to support these approaches have dealt a huge blow to many students and teachers.

A departmental report released in March 2021 found that 99% of public school students got passing marks for the first academic quarter of last year. But other surveys claim that students are being disadvantaged. Over 86% of the 1,299 students polled by the Movement for Safe, Equitable, Quality and Relevant Education said they learned less through the education department’s take-home modules—so did 66% of those using online learning and 74% using a blend of online learning and hard-copy material.

Read More: Angelina Jolie on Why We Can Let COVID-19 Derail Education

Even though she’s an academic topnotcher—getting a weighted grade average of 91 out of 100 last year—Delaroso also feels that remote learning is inferior.

At Delaroso’s high school, teacher Johnnalie Consumo, 25, has detected a lack of eagerness to study, with some parents even filling in worksheets on their child’s behalf—going by the evidence of the handwriting.

“They have a hard time forcing the kid to answer modules because the kid isn’t intimidated by their parents,” she tells TIME. “The way a teacher encourages is very different from how a parent would.”

Consumo sometimes visits the homes of under-performing students and finds that they are out doing farm work—harvesting sugar cane, say, or making charcoal—to augment a family income that has been slashed by a suffering economy and a rising unemployment rate . Exercise books have been turned in blank, she says. Or students appear to pass their modules, only for her to find that they copied the answers. The frustration is enormous.

“It’s hard on our part,” Consumo tells TIME, “because we really try our best.”

Poverty and education in the Philippines

Internet access is a huge challenge. In urban areas, instructors can give lessons over video conferencing platforms, or Facebook Live, but 52.6% of the Philippines’ 110 million people live in rural areas with unreliable connectivity. It doesn’t come cheap either: research from cybersecurity firm SurfShark found that the internet in the Philippines is among the least stable and slowest, yet the most expensive, of 79 countries surveyed.

Internet access assumes, of course, that the user has a device, but in the Philippines that’s not a given. Private polling firm Social Weather Stations found that just over 40% of students did not have any device to help them in distance learning. Of the rest, some 27% were using a device they already owned, and 10% were able to borrow one, but 12% had to buy one, with families spending an average of $172 per learner. To put it into perspective, that’s more than half the average monthly salary in the Philippines.

“Some of them don’t have cell phones,” says Marilyn Tomelden, a teacher in Quezon province, three hours away from the Philippine capital Manila, who first noticed the digital divide when many of her sixth graders were unable to comply with what she thought of as a fun homework assignment: submitting videos of themselves performing dance moves she had demonstrated in an earlier video.

“Because we’re in public school, we cannot demand that they buy phones,” Tomelden says. “They don’t have money to buy their own food, and they’re going to buy their own cell phone for learning? Which is more important to live—to eat or to study?”

Instructors need to be equipped with the right resources too. A study from the National Research Council of the Philippines found that many teachers have had to shell out their own money to support their students in remote learning.

Read More: The Long History of Vaccinating Kids in School

Government agencies do what they can to help. Earlier this year, the customs bureau donated phones and other gadgets it had confiscated to the education department for distribution to needy students. But it’s a drop in the ocean.

“It’s something that is beyond [our] capacity to address—the inequality in terms of availability of resources of learners, depending on the socioeconomic status of families,” says education undersecretary San Antonio.

Some students are so exhausted by the struggle to study remotely that they are calling for long breaks between modules. Many parents and pressure groups are going even further, demanding total academic suspension until a clearer post-pandemic education system is ironed out.

Congresswoman France Castro is a member of ACT Teachers Partylist, a political party representing the education sector. She says a complete freeze would cause more problems than it solves.

“Education is a right,” she tells TIME. “Whatever form it will be, whether blended learning or modular, it’s better to continue it than to stop.”

But in the meantime, with their workloads multiplied, it is students and teachers paying the price. Consumo, the teacher from Januiay, regularly stays up late completing the reams of new paperwork generated by the distance learning system.

“You won’t be able to sleep anymore, just thinking about the deadlines and the work that still needs to be done,” she says. “I cry over that.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at [email protected]

In last ASEAN country to reopen schools, Philippines' students fret about pandemic’s impact on their future

ADVERTISEMENT

UN Philippines 2023 Annual Report

Secretary-General's Policy Brief on Education During COVID-19 and Beyond

Key Messages

- The COVID-19 pandemic has created the largest disruption of education systems in history, affecting nearly 1.6 billion learners in all countries and all continents.

- The pandemic has exacerbated education disparities. Learning losses due to prolonged school closures threaten to erase progress made in recent decades, not least for girls and young women .

- Some 23.8 million additional children and youth (from pre-primary to tertiary) could drop out or not have access to school next year due to the pandemic’s economic impact alone.

- Education is a fundamental human right. It is the bedrock of just, equal and inclusive societies and a main driver of sustainable development. To prevent a pre-existing learning crisis from turning into a learning catastrophe, governments and the international community must step up.

- Once national or local outbreaks of the virus are under control, governments must look to reopen schools safely, listening to the voices of key stakeholders and coordinating with relevant actors, including the health community.

- The gap in education financing globally could increase by 30% because of the crisis. Governments need to protect education financing in national budgets, in international development assistance and through greater cooperation on debt.

- To cope better with future crises, governments should strengthen the resilience of education systems by placing a strong focus on equity and inclusion; and on reinforce capacities for risk management. Failure to do so poses major risks to international peace and stability.

- The transformation of education systems has been stimulated and reinforced in many countries during the pandemic: innovative solutions for learning and teaching continuity have flourished.

- Responses have also highlighted major divides, beginning with the digital one. It is time to reimagine education and accelerate positive change, and ensure that education systems are more flexible, equitable, and inclusive .

- To spur global momentum around the education emergency and the need to protect and reimagine education in a post-COVID-19 world, a coalition of global organizations [i] is joining forces to launch the ‘ SaveOurFuture ’ campaign. This campaign will amplify the voices of children and young people and urge governments worldwide to recognize investment in education as critical to COVID-19 recovery.

[i] UNICEF, UNESCO, World Bank, Save the Children, Education Cannot Wait, Global Partnership for Education, Education Outcomes Fund, Education Commission, Asian Development Bank, African Development Bank.

View the Secretary-General's video statement.

Published by

Goals we are supporting through this initiative, related resources.

- Our Mission, Vision, Values, & Policies

- Our History

- Our Centenary

- Our Leadership

- Global Reach

- Accountability

- Humanitarian Response

- Health and Nutrition

- Childs' Rights & Protection

- Our Stories

- Where We Are

- Partner with Us

- Partner Bulletin

- Join Our Team

- Give to Save

- Kindness Circles

- Media Releases

- Publications

- Newsletter Signup

- Media Awards

- Get Involved

- Privacy Statement

- Legal Notice

Save the Best for Children Under the Uncertainties of COVID-19

Too many children have been denied healthcare, been torn out of school, or left in abusive homes without access to protection.

Program: Child's Rights and Protection

Type: Story

Op-ed on associated with Policy Brief: “ COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from the Asia-Pacific ”

Lessons from the Philippines:

The deadly widespread COVID-19 has brought unprecedented challenges to the world. It is not only a global public health emergency that has claimed thousands of hundreds of people’s lives, but also causes immediate and long-term economic impacts which have devastating effects on billions of households. The Philippine has become the second hardest-hit country by COVID-19 in Southeast Asia. As of early July, there are 51,754 confirmed cases and 1,314 fatalities reported. The number of confirmed cases has been increasing rapidly since June.

The most marginalized across the country– the 33 million children who make up around one-third of the Philippine population – are likely to be hit the hardest. Too many children have been denied healthcare, been torn out of school, or left in abusive homes without access to protection.

But in crisis there is also opportunity. The pandemic is a chance for regional governments to build back better, safer, and greener. In July, Save the Children set out a post-pandemic agenda for the Asia Pacific region, including the Philippines – a road map for how we can use the disruption of COVID-19 to create fairer and more inclusive societies. We believe that the virus must lead to a fundamentally different world – a new social contract between governments and people, drawing on lessons from the pandemic’s impact on all of our lives.

With the COVID-19 fatality rate of 3.37%, the Philippines has the second-highest fatality rate in Southeast Asia . The rapid spread and relative high death ratio of COVID-19 have shown the inefficiency of the healthcare system as well as insufficient public health management capacity of the Philippines. Broadly speaking, countries with well-functioning hospitals and stockpiles of crucial supplies including Personal Protective Equipment have done better in protecting their populations from the pandemic. The Philippines’ low healthcare expenditure mainly explains the low efficiency. The healthcare expenditure of the Philippines as part of the GDP has been around 4.4% for several years, much lower than the world’s average level of 9.89% . The country has also faced a shortage of vital medical supplies. “The average number of ventilators in small hospitals around the Philippines is very small compared to what is really needed,” according to a media report . Countries with better-resourced healthcare systems such as Thailand and Vietnam have done much better. For example, Thailand could provide 10,000 ventilators for a population of 70 million. The pandemic is a wake-up call for governments to target at least five percent of their GDP spending on healthcare moving forward.

The education sector has also been disrupted on an unprecedented scale, with 28,451,212 students affected in the Philippines due to the nation-wide school closures . To stem the spread of coronavirus, in early March, all educational institutions were enforced to close schools and classes have been shifted online . Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte recently said he will not allow students to go back to school until a coronavirus vaccine is available, even as some other countries resume in-person classes . However, virtual classrooms are inaccessible to those without internet connections. The pandemic has exposed the sharp digital divide in the Philippines, where most children living in rural and remote areas have no access to the internet. The Philippine’s network readiness index scores only 47.7, ranking 71 worldwide, compared with Singapore’s 82.13 , which shows that most Filipino children are not technically prepared for long-term online learning.

Internet access is becoming more than just a daily necessity but is also crucial in fulfilling a number of children’s human rights – including access to education and information. With online education likely here to stay, the Philippine government must redouble efforts to ensure that everyone can access the internet, including those in marginalized and rural communities.

The combination of lockdown and school closure has also heightened the risks of increased Violence Against Children (VAC), particularly online sexual exploitation in the Philippines. The financial and psychological pressures brought about by the pandemic have increased tensions in the home, resulting in huge spikes in calls to domestic violence hotlines in the country. Children have been particularly hard hit by what the UN has called a “shadow pandemic”, as they have been unable to access the protection services they normally would or find sanctuary and safety in schools. The Department of Justice (DOJ) Office of Cybercrime said 279,166 child sexual abuse cases have been reported from March 1 to May 24 this year, compared to 76,561 cases over the same period in 2019. The cases of internet-based sexual exploitation of children this year saw an increase of up to 264 percent, the Philippine’s DOJ pointed out .

The government leaders must use the pandemic to strengthen systems protecting children from domestic violence and other forms of abuse. They must invest in remote monitoring systems that can better detect violence against children behind closed doors in family homes. The virus has also shown that social service workers who play a crucial role in protecting children from harm must be deemed “essential” in the same way that medical doctors and nurses are.

The pandemic has wrought havoc across war-torn and wealthy societies worldwide. In the Philippines, the situation is not any better with 33 million children facing different forms of issues associated to healthcare, learning, and violence on different levels. We owe it to children to learn our lessons from the virus and create a world where they can not only stay alive with their families, but also grow and thrive.

John Hopkin University & Medicine https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html visited on July 10, 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/678279/philippines-children-as-a-percentage-of-the-population/ Coronavirus (COVID-19) death rate in countries with confirmed deaths and over 1,000 reported cases as of July 1, 2020, by country. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105914/coronavirus-death-rates-worldwide/ https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS?locations=PH-1W Ventilators for Covid-19 patients being produced by PHL experts https://businessmirror.com.ph/2020/05/01/ventilators-for-covid-19-patients-being-produced-by-phl-experts/ UNESCO, COVID-19 Impact on Education https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse COVID-19: Bangladesh shuts all educational institutions https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/covid-19-bangladesh-shuts-all-educational-institutions/1767425 Coronavirus: No vaccine, no school reopening in Philippines, Duterte says https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/no-vaccine-no-school-reopening-duterte-says Disconnected: Digital divide may jeopardize human rights https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/05/18/disconnected-digital-divide-may-jeopardize-human-rights.html Online child sexual abuse in Philippines triple during COVID-19 lockdown http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-05/25/c_139087053.htm

Related Links:

- COVID-19 Pandemic Lessons from Asia Pacific

- Help Keep Children and Their Families Safe from COVID-19

More stories from our programs

Students Actively Campaign Against Online Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children

Keep internet a safer place during COVID-19

WATCH: Busting myths about children with disability

The Beauty and Strength of Femininity Through the Eyes of a Child Leader

Stay up to date on how Save the Children Philippines is creating a world where every child has a safe and happy childhood

About save the children philippines.

Save the Children Philippines has been working hard every day to give Filipino children a healthy start in life, the opportunity to learn, and protection from harm. We do whatever it takes for and with children to positively transform their lives and the future we share.

DSWD License No.: DSWD-SB-L-00008-2024 Coverage: Regions I, II, III, IV-A, IV-MIMAROPA, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, CARAGA, CAR, and NCR Period: February 16, 2024 – February 17, 2027

Follow and Connect with Us

Join the conversation.

Donate today!

+63-929-754-3066, +63-966-216-2368 and (+632) 8852-7283 (8852-SAVE) [email protected]

- © Save the Children Philippines

DSWD Authority/Solicitation Permit No. DSWD-SB-SP-00068-2020/Area of Coverage: Nationwide DSWD License Number: DSWD-SB-RL-00036-2017

Navigate to:

- DLSMHSI Home

- DLSMHSI Academics

- DLSUMC

- DLSMHSI Research

- Cavite line: (6346) 481-8000 | Manila line: (632) 8988-3100 | Go to MyDLSMHSI |

About DLSMHSI Academics

- Administrators

- List of Academic Collegiate and Departmental Administrators

- List of Academic Administrators SY 2020-2021

- A-Team Online Publication SY 2022-2023

- Calendar of Activities S.Y. 2022-2023

- Downloadable Forms

- Contact Information

DLSMHSI is a premier higher education institution committed to teaching and forming future medical and health allied professionals who will have the commitment and dedication to become catalysts of the spiritual, social, and economic transformation of our country.

- College of Medicine

- College of Allied Sciences

- College of Medical Imaging and Therapy

- College of Medical Laboratory Science

- College of Nursing

- Dr. Mariano Que College of Pharmacy

- College of Rehabilitation Sciences

- College of Dentistry

Senior High School

- Graduate Studies in Medical and Health Sciences

- Special Health Sciences Senior High School

High School

- Special Health Sciences High School

- Course Offerings

- Process and Procedures

- DLSMHSI Entrance Exam

- Campus Tour

- Calendar of Activities

- DLSMHSI International Partners

Potential students will be properly guided before, during, and after their application for admissions. The admission process and procedure are clearly and completely presented to inform all applicants of the step by step process so their applications are done expeditiously.

Learn More . .

- The Registrar

- Scholarship

Romeo P. Ariniego, MD, AFSC Library

- About RPAMDAFSC Library

- Library Units and Services

- Policies and Procedures

- Online Resources

- GreenPrints

- Research Guides

- Journals Locator

- Reservation of Learning Cubes

- Student Affairs

- Privacy Policy

Academics sends messages of hope, inspiration and solidarity amidst COVID-19 pandemic

June 3, 2020 | 10:32 am

Home / A-Team On-Line Publication / Academics sends messages of hope, inspiration and solidarity amidst COVID-19 pandemic

“I won’t let the Academic Community succumb to this COVID-19 pandemic. Learning continues. Teaching continues. Academic Service support continues. Staff support continues. Our operations continue for Learning knows no boundaries. Together, and by association, we shall all prevail”.

Juanito O. Cabanias, LPT, MAE, PhD Vice Chancellor for Academics

“At the end of the day all we need is hope and strength. Hope that it will eventually get better and strength to hold on till it does”. And while we are waiting; whatever hardship, challenges, indecisions and fears that we are facing, we just remember that these too shall pass and by the grace of God we will overcome. To our students we hope that they continue to trust us that what we do today will define what kind of health professionals they will all be in the future. We promise that excellence will still be part of everything that we do for them and our community. Just remember that tomorrow is still full of wonderful possibilities for all of us here in DLSMHSI.”

Alicia P. Catabay, RPh, MSc, PhD Dean, College of Pharmacy

“We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” Oscar Wilde As a Lasallian community, may we continue to reach out to those who may have forgotten the light that shines above. There’s light in this darkness; all we need is to look up.”

Sigfredo B. Mata, RPh Vice Dean, College of Pharmacy

“Spanish flu (1918-1920); Asian flu (1957-1958); Hong Kong flu (1968-1969); H1N1/09 flu (2009-2010);

Which have lost an outrageous number of lives.

Then, COVID-19 (this too shall pass). Four words that may have given hope and resurrection to millions, then and now.

Life may be short, but God made sure it is wide and tall”

Jose Antonio P. Amistad, MD, FPSA Dean, The Student Affairs

“St. John Baptist de La Salle believes that education gives hope and opportunity for people. And so, during this time of COVID-19 uncertainty, let us remember that we were chosen to continue the mission of St. La Salle in nurturing the young, through education, especially those who had little hope for educational advancement due to COVID-19 pandemic.”

Marlon G. Gado, RL, MLIS Director, Center for Innovative Education and Technology Integration

“Weak? Tired? Feel like giving up? Take heart…We have Someone greater than all these challenges.

Isaiah 40:28-29, 31 says, “….The everlasting God, the Lord, The Creator of the ends of the earth, Neither faints nor is weary…. He gives power to weak, And to those who have no might He increases strength…. ….those who wait on the Lord Shall renew their strength;”

Maria Corazon E. Gurango, MD, MPH, FPAFP Director, Center for Community Engagement and Health Development Program

“This pandemic has caused anxieties, fears, and uncertainties. But we are capable, strong, and resilient. We may not be able to control the situation but we can control ourselves: our thoughts, actions, and choices. We can rise above these challenging times and continue our mission and ministry together as one Lasallian community.”

Efren M. Torres, Jr., RL, MLIS Director, Romeo P. Ariniego, MD, AFSC Library

“The COVID-19 pandemic brings new challenges unfolding each week, compelling us to re-configure our academic strategies with urgency but with uncertainty, and oftentimes beyond our capacity to cope. We must not lose hope, and as one community in Christ, continue with our mission inspired by John Baptist De La Salle.”

Lemuel A. Asuncion, OTRP OT Chair, Clinical Education College of Rehabilitation Sciences

“The Lord gives His toughest battles to His strongest soldiers”.

The greatest weapon we can have today is guarding ourselves with faith and prayer. May this situation help us realize that the Lord is always with us and will never leave us.”

Jion P. Dimson, RMT, MSMLS Chair, Student Development and Activities Department, The Student Affairs

“As Lasallians in these time of pandemia, let us compose ourselves as mature, responsible, and self-disciplined individuals minding our health and safety, as well as our academic responsibilities in achieving our full potentials. By simply staying at home and doing worthwhile things, we are expressing our reverence for life.”

Roberto L. Cruz III, RN, MAN Chair, Student Discipline and Security Department The Student Affairs

“As Lasallians we still continue to serve our partner communities despite the threats of COVID-19 along our way because nothing can stop our great desire to improve the health of our communities. We will continue to empower the people in the community for heath equity and for God’s greater glory!”

Jose Marcelo K. Madlansacay, MDC Chair, Community Service-Learning Projects Center for Community Engagement and Health Development Program

“The challenges of COVID-19 may seem unnerving yet, it can be an opportunity for growth and positive changes. May we strive to be hopeful, courageous and resilient despite the adversities we have to face. Let us draw strength from each other as we pray for healing around the world.”

Ma. Sheila Q. Ricalde, MAEd, RPm, RGC Vice Chair, Student Life The Student Affairs

“You are capable to handle this. I BELIEVE IN YOU. This health crisis can be overwhelming and that is PERFECTLY NORMAL. You may not think and/or feel at your best this time but THAT IS OKAY. YOU can still be a beacon of hope amidst this pandemic.”

Cesar M. Lago, MAEd, RGC Vice Chair, Student Success The Student Affairs

COVID-19: A Blessing?!

“COVID-19 can be considered as a blessing in disguise. Because of it, many have changed. All the busy streets were emptied, all the malls were closed, all were required to stay home. Everyone started to help one another, family ties were strengthened, everybody started again to turn to God and pray, pollution was lessened and Mother Earth started to recuperate. Let’s look on the brighter side. Stay well Lasallians!”

Jose Royce P. Aledia, RGC Chair, Student Wellness and Guidance and Counseling Department The Student Affairs

“As we face this time of uncertainty, the COVID-19 pandemic, do not forget that God is with us, we have to intensify our faith, be mindful that protection from sickness must begin within us, always wear mask, wash our hands frequently and observe distancing, take care not only our physical health but also our mental health. Keep safe everyone!”

Irene B. Maliksi, RN Chair, Student Health and Safety Department The Student Affairs

“There is light at the end of the tunnel, a rainbow after the rain and every cloud has a silver lining. Despite the pandemic, we, the Non-Teaching Personnel, will continue to support the administration in fulfilling the mission set forth by our Founder, St. John Baptist De La Salle. Together we will fight. Forever, we stand as ONE.”

Leslie V. Brito Administrative Assistant, College of Medical Laboratory Science

“Congratulations, graduating class of 2020! We might not have experienced the momentous march of our graduation, yet. Our victory should set blaze in our hearts and actions, not doused even by COVID-19. As the Wolff’s law says, “Strengthened under force of pressure, and overtime will become stronger to resist it.””

Christ Don E. Apuntar President, DLSMHSI Institutional Student Council

“As we face this global health crisis that causes major upheaval, we encounter challenges and become anxious about what’s going to happen. But surely, the presence of the Lord provides us hope of healing and certainty of the future. All you need to do is pray and strengthen your faith in Him! He will never leave us. He is our Emmanuel (God with us).”

“Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me”. —Psalms 23:4

Joren B. Fernecita President, College of Medicine Student Council

“We all know the dangers brought about by this pandemic, but worry less since everything is going to be alright. I do believe that we just need to have faith in God to overcome this. He will be the one to give us hope and strength to hold on until it gets better.”

Renee E. Andal President, College of Pharmacy Student Council

“To everyone, these are trying times but never forget to have faith in God and always seek guidance from Him. Always remember to stay safe and healthy. Let us fight this pandemic as One La Salle!

To our front liners, going above and beyond the call of duty is the essence of heroism. Some have fallen, but a lot more are continuing the fight. Heavy sacrifices have been, and continually being made. Words cannot capture the gratitude we wish to convey. But still, thank you front liners, heroes all, in every sense of the word.”

Christian Derik L. Aquino President, College of Humanities and Sciences Student Council

“COVID-19 has changed our way of living and has transformed us to something we have never imagined. This pandemic has affected all of us. As we face more challenges along our way, let us all be determined to keep on learning despite the hindrances. None of us can say with certainty when will it be safe…when will we get back to normal…when will this be over. Let not fear hold us back and may our faith help us triumph over this unseen enemy.

Stay safe. As Lasallians, We are One in this battle!”

Neil Vincent D. Guyamin President, College of Medical Imaging and Therapy Student Council

“As we face an invisible enemy, let’s take this opportunity to come together with clasped hands to pray for each and everyone’s safety. COVID-19 might have changed our way of viewing things, yet let’s be thankful for the life we have. At times like these, you may feel anxious; but do remember that you matter. You are not alone. We will bounce back and will continue to fight this pandemic as One Lasallian Family.”

Maria Veronica Louise C. Cabubas President, College of Medical Laboratory Science Student Council

“This COVID-19 pandemic has taught us a lot of things. We became closer to our family, realize the importance of our healthcare workers, and reflect that no one is safe unless you follow the guidelines set by our government. Even though we are far from its end, it is vital for us to always know that there is hope. That someday, we will see the light and overcome this darkness.

We shall conquer this together, Animo La Salle!”

Marvin Jay C. Salvador President, College of Nursing Student Council

“During his time, the Founder faced adversaries not too different from ours – poverty, hunger, sickness, corruption. He fully surrendered the work to God and succeeded. Likewise, let us remain steadfast in faith, bringing light to those who feel lost in the dark. Let us be vigilant whilst being empathetic to protect and nurture the weak and the weary. As we go through this pandemic, encourage a neighbor, check on a friend, hug a family member, donate to an organization, pray for the world; hope grows from the service we give – small or big. God will win the battle for us and we will call it our victory.”

Lizzy Jane Niquole Y. Ricardo President, College of Rehabilitation Sciences Student Council

“Yesterday is history, tomorrow is a mystery, today is a gift of God, which is why we call it the present.” ― Bill Keane

“Every day is a blessing and we should not forget to thank God for it. In this time of crisis, we need to strengthen our faith in Him and believe that this will soon be over. There’s no such thing as too much praying after all, for He can get us through this pandemic.”

Hennessy M. Frani President, SHSSHS Student Council

Latest Publication

DLSMHSI posts outstanding performance in recent licensure examinations

October 30, 2022 | 9:44 am

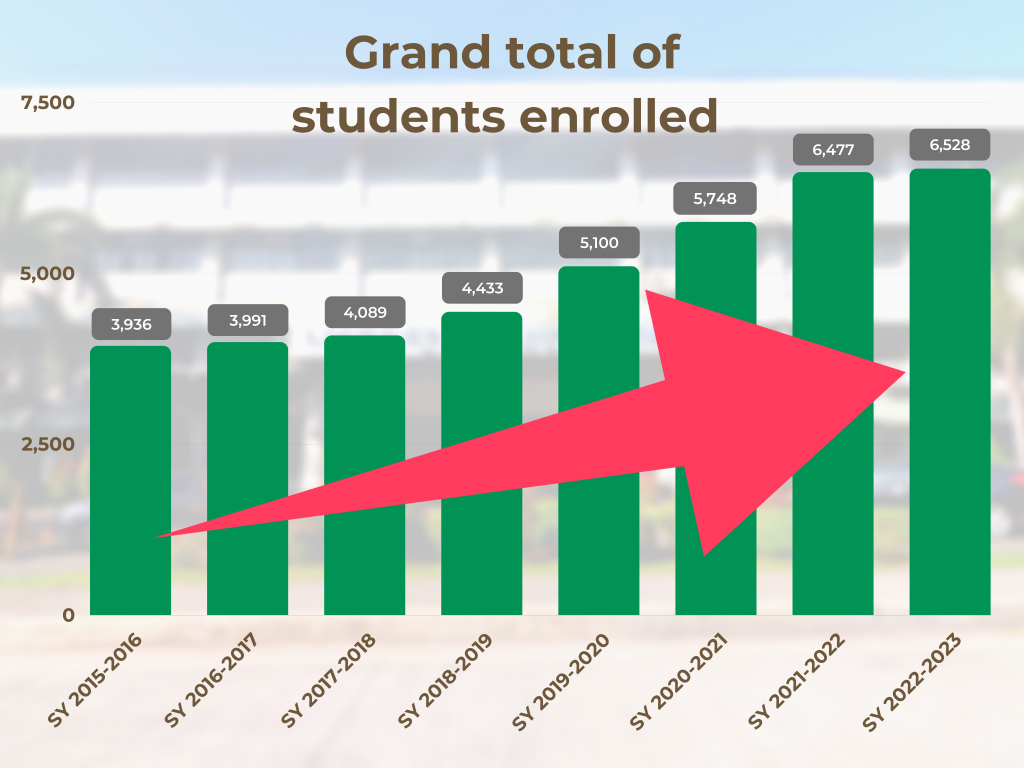

Academics posts record-high enrollment statistics in SY 2022-2023

September 30, 2022 | 2:25 pm

A-Team witnesses the State of the Academics Address 2022

August 31, 2022 | 11:41 am

CHED grants approval to three new programs of DLSMHSI

July 30, 2022 | 7:30 pm

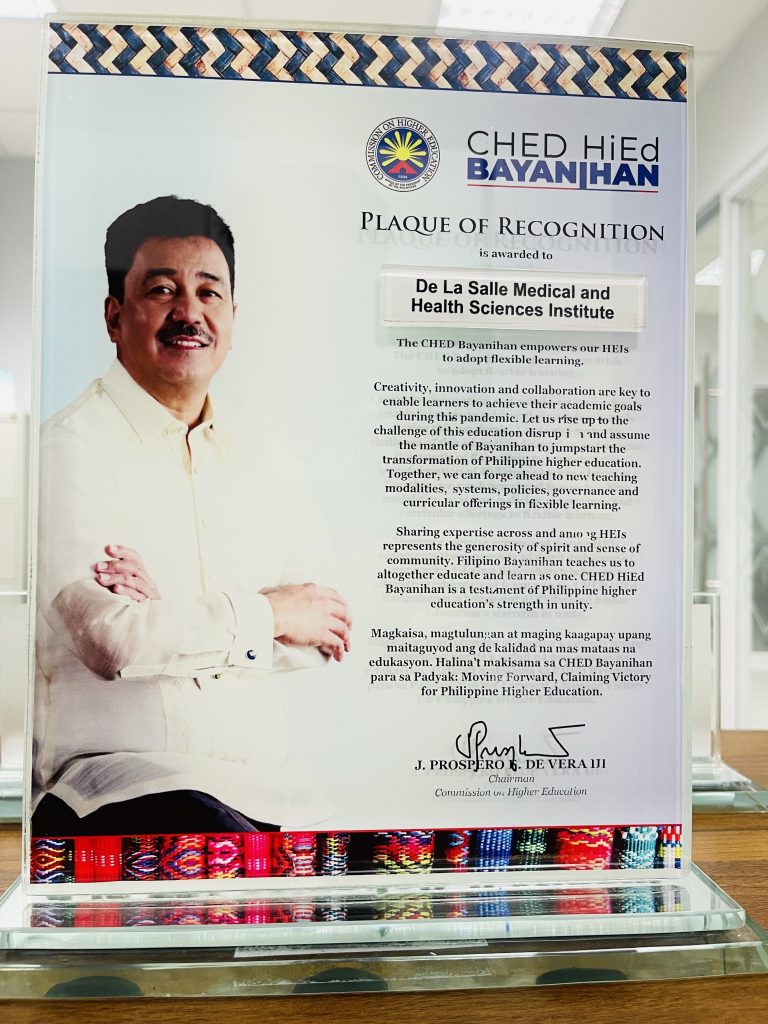

CHED recognizes DLSMHSI for supporting Hi-Ed Bayanihan Project

June 30, 2022 | 12:00 pm

DLSMHSI launches the Scholarship to Employment Program

May 31, 2022 | 2:25 pm

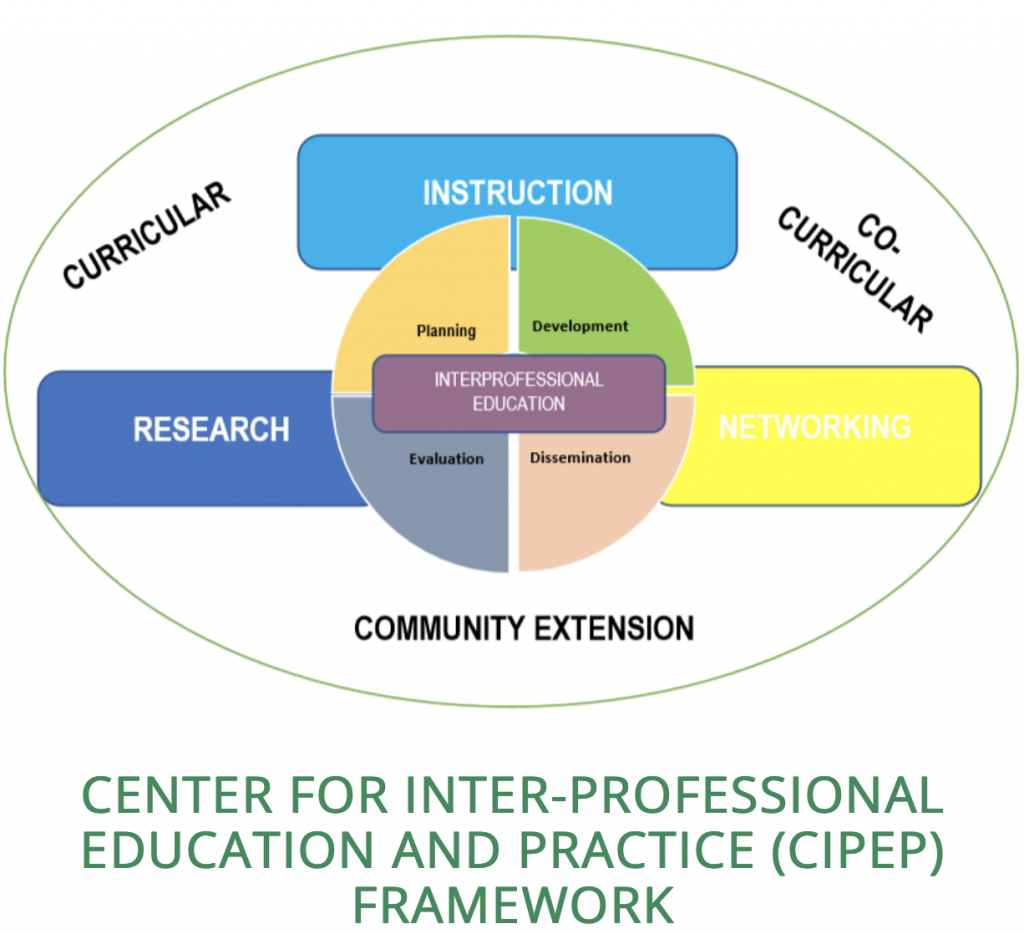

DLSMHSI implements inter-professional education and practice

April 27, 2022 | 6:21 pm

BS in Life and Health Sciences opens in SY 2022-2023

April 5, 2022 | 11:06 am

VCA bares the Academics’ Theme for 2022

March 3, 2022 | 8:54 am

DLSMHSI keeps the lead as the Best RT School in the country

January 24, 2022 | 3:01 pm

Christmas message of the Vice Chancellor for Academics

December 24, 2021 | 8:09 pm

DLSMHSI receives AUN-QA certification

November 29, 2021 | 7:46 pm

Contact Us

Send an Email

Online Student Records Application

For Online Request of Student Documents, Please Email: [email protected]

- Toggle Accessibility Statement

- Skip to Main Content

Briones, education ministers unite to ensure learning continuity amid COVID-19

PASIG CITY, June 19, 2020 – True to their mission of ensuring that learning must continue, Secretary Leonor Magtolis Briones, together with other Southeast Asian education ministers, presented their different education strategies in response to the COVID-19 global crisis during the first South East Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) Ministerial Policy e-Forum held last Thursday, June 18.

With the theme, “Education in a Post-COVID-19 World”, the first SEAMEO e-forum provided a platform for education leaders and experts to share their knowledge and solutions on how to manage the effects of COVID-19 to the education landscape in Southeast Asia.

Secretary Briones and the education ministers from Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Timor-Leste, Thailand, and Vietnam, shared their education frameworks and innovations to frame the new normal in education and laid out their preparations for the opening of classes within their respective countries. Like the Philippines, other Southeast Asian countries have also adopted modular systems to deliver education while prioritizing the safety of the learners.

Singapore, who ranked second in all subjects among 78 countries in the 2018 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), has continued to operate their schools amid the pandemic and is now starting their third term of classes.

“I think the basic choice before us is this – COVID-19 will be with us for some time, a year, and likely longer, until a vaccine is found. We cannot afford to keep schools closed for such a long time. It has a significant long-term impact on our children. It inflicts a tremendous social and human cost. Studies have shown that it can set students back for many years, even into adulthood. So we must try our best to save the school year, this and the next one, by keeping schools open but safe,” Singapore education minister Ong Ye Kung stated in his speech.

Minister Ong also mentioned that despite the challenges the education sector is facing, there were good things that came out from non-face to face strategies.

“It has been a tough period for every school system in the world. But there is a silver lining in every dark cloud. School systems in many countries have had to adjust to blended forms of learning in response to the pandemic, using the Internet, TV and even radio, as alternate platforms for students to gain access to education resources.”

The ministers also adopted a joint statement in the historic first ministerial e-forum as they shared progress made in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic and appreciated the efforts made by the educators and education stakeholders in member countries to ensure that no Southeast Asian learner is left behind especially in these unprecedented times.

No Filipino learner will be left behind amidst the crisis

As part of the Philippines’ short and long term strategies, Secretary Briones introduced the BE-LCP as a guideline for the department on how to deliver education in time of the COVID-19 pandemic while ensuring the health, safety, and welfare of all learners, teachers and personnel of DepEd.

“The first principle that we adhered to and which we are committed to, in compliance with the President’s directive is to protect the safety, health and well-being of our learners, teachers and personnel and to prevent further transmission of COVID-19. But at the same time, we want to ensure learning continuity. Our battle cry is learning must continue,” Briones said in the forum.

Another main feature of BE-LCP is the adoption of multiple learning delivery modalities, with blended learning and distance learning as major options.

Briones emphasized that online learning is only one option from the menu of learning modalities. These modalities will be offered appropriately depending on the situation of the learners’ households.

“We have come out with a variety, with menu of options, online is not the only answer, there’s a huge debate in the Philippines on how useful or whether it is really a good way of teaching learners, so we have online, we have televisions, we have radio. If all else fails, then learning modules are being printed so that these will be delivered in various pick-up points or either parents or for the village officials to distribute to the learners,” she said.

- Title & authors

Ignacio, Aris E. "Online Classes and Learning in the Philippines During the Covid-19 Pandemic." International Journal on Integrated Education , vol. 4, no. 3, 2021, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.31149/ijie.v4i3.1301 .

Download citation file:

The COVID-19 pandemic brought great disruption to all aspects of life specifically on how classes were conducted both in an offline and online modes. The sudden shift to purely online method of teaching and learning was a result of the lockdowns that were imposed by the Philippine government. While some institutions have dealt with the situation by shutting down operations, others continued to deliver instructions and lessons using the Internet and different applications that support online learning. The continuation of classes online had caused several issues from students and teachers ranging from lack of technology to mental health matters. Finally, recommendations were asserted to mitigate the presented concerns and improve the delivery of the necessary quality education to the intended learners.

Table of contents

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Philippines Returns to School, Ending One of World’s Longest Shutdowns

More than two years after Covid emptied their classrooms, students are resuming in-person learning. The lost time will be hard to make up.

By Jason Gutierrez

MANILA — Millions of students throughout the Philippines headed to school on Monday as in-person classes began to fully restart for the first time in more than two years, ending one of the world’s longest pandemic-related shutdowns in a school system already plagued by severe underinvestment.

“We could no longer afford to delay the education of young Filipinos,” said Vice President Sara Duterte, who is also the education secretary, as she toured schools in the town of Dinalupihan, about 40 miles northwest of Manila.

Even before the pandemic, the Philippines had among the world’s largest education gaps, with more than 90 percent of students unable to read and comprehend simple texts by age 10, according to the World Bank.

Schools in the Philippines have long suffered from shortages of classrooms and teachers, whose pay is low, leaving the vast numbers of poor children who cannot afford private schools and rely on the public system with inadequate teaching.

Now, after losing more than two years of in-person instruction, schools face the monumental challenge of educating many students who have fallen even further behind.

Though the Philippines offered online instruction during the pandemic, many students lacked access to computers or internet connections, and overburdened parents often found it hard to keep tabs on their children’s remote learning.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Successful COVID Campaign in Philippines Wins Accolades

- November 2, 2020

- By Stephanie Desmon

When the COVID-19 pandemic landed in the Philippines in March, it quickly became clear that there needed to be an easy way for the Department of Health to share important messages with its citizens on how to prevent the spread of the disease.

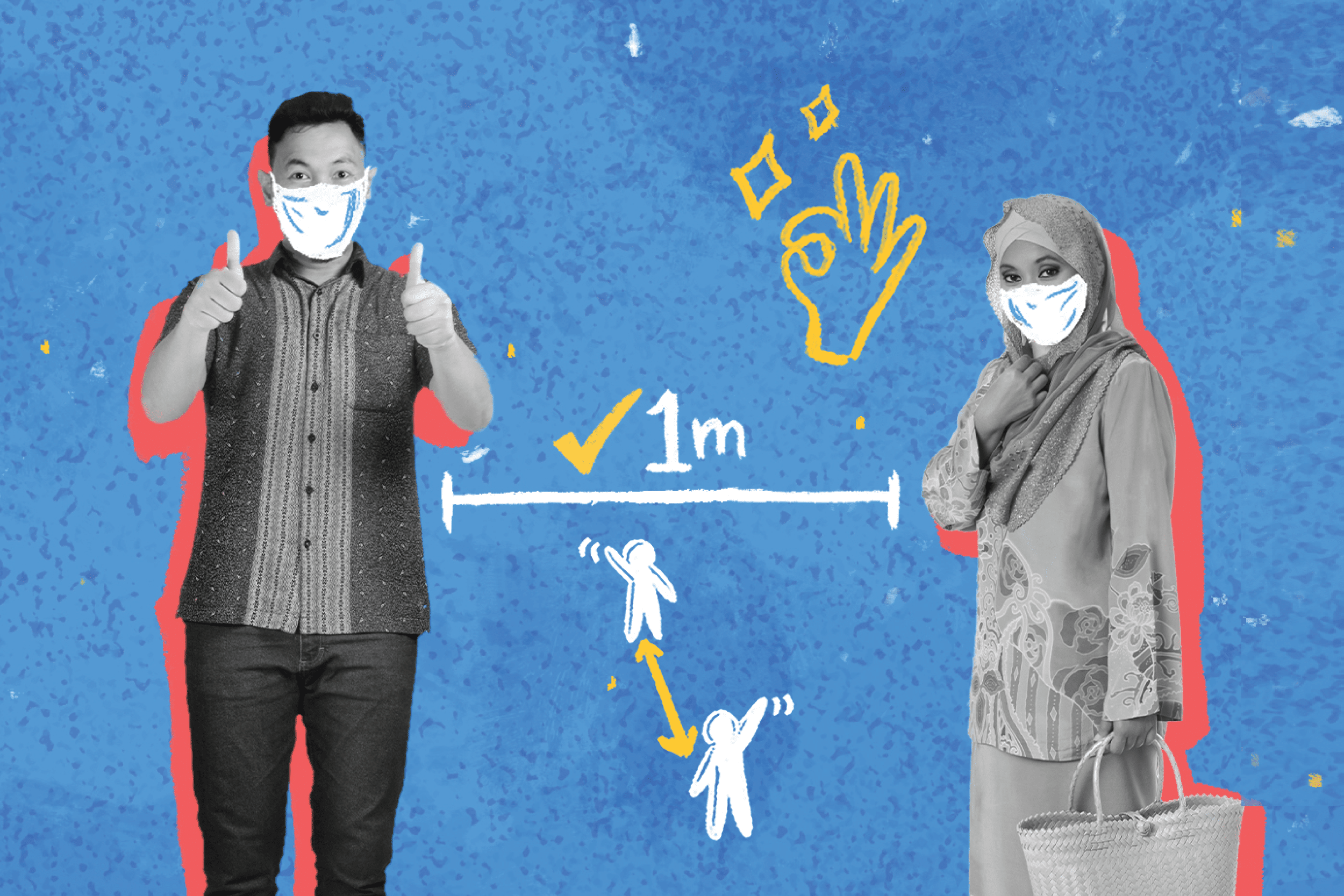

Working with the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, the Philippine Department of Health’s Healthy Pilipinas was quickly born. The Facebook page and COVID Alis sa Pamilyang Wais (“Family Smarts Keep COVID Away”) campaign went into action, sharing critical information on prevention behaviors such as handwashing, social distancing and mask wearing, as well as facts about testing, travel and much more.

The Facebook page has reached 160 million people since it started in late March. In the first month alone, the page earned 100,000 followers, with more than 270,000 new followers six months later. A single post in April reached 3.4 million people.

“The Healthy Pilipinas page is a one-stop source of credible, digestible and actionable information needed to fight the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Billie Puyat Murga, a senior program officer for social behavior change and gender, who led the effort for CCP. “The material is conveyed in a fun and conversational manner and is designed to reach household decision makers who can help protect their families.”

For this work, the team behind Healthy Pilipinas took home a Stevie Award, which recognizes the achievements of women executives, entrepreneurs and the organizations they run in the Philippines. The award came in the category of “Best Use of Social Media – COVID-19-related Information,” which honors nominations of social media communications, deployed for or by women in 2020, to inform the public about the pandemic and how to stay safe.

CCP’s COVID work in the Philippines is part of the Breakthrough ACTION project, funded by USAID, in 22 countries to assist with communication needs key to controlling the pandemic. The efforts have reached more than a billion people since March. The Philippines has recorded nearly 360,000 COVID-19 cases and nearly 6,700 deaths, according to Johns Hopkins University .

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

Related posts.

Good Tidings for All, Today and Tomorrow

Training Program Equips Nigerian Journalists with Health Reporting Skills

Lessons Learned from Using Celebrities as Public Health Messengers

Subscribe to ccp's monthly newsletter.

Receive the latest news and updates, tools, events and job postings in your inbox every month

Privacy Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Health Promot Perspect

- v.11(3); 2021

Mental health and well-being of children in the Philippine setting during the COVID-19 pandemic

Grace zurielle c. malolos.

1 College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

Maria Beatriz C. Baron

Faith ann j. apat.

2 Matias H. Aznar Memorial College of Medicine, Cebu City, Philippines

Hannah Andrea A. Sagsagat

3 West Visayas State University-College of Medicine, La Paz, Iloilo City, Philippines

Pamela Bianca M. Pasco

Emma teresa carmela l. aportadera.

4 Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines

Roland Joseph D. Tan

5 Baguio General Hospital and Medical Center, Baguio City, Philippines

Angelica Joyce Gacutno-Evardone

6 Department of Pediatrics, Eastern Visayas Regional Medical Center, Tacloban City, Philippines

Don Eliseo Lucero-Prisno III

7 Faculty of Management and Development Studies, University of the Philippines Open University, Los Banos, Laguna, Philippines

8 Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has subjected the mental health and well-being of Filipino children under drastic conditions. While children are more vulnerable to these detriments, there remains the absence of unified and comprehensive strategies in mitigating the deterioration of the mental health of Filipino children. Existing interventions focus on more general solutions that fail to acknowledge the circumstances that a Filipino child is subjected under. Moreover, these strategies also fail to address the multilayered issues faced by a lower-middle-income country, such as the Philippines. As the mental well-being of Filipino children continues to be neglected, a subsequent and enduring mental health epidemic can only be expected for years to come.

Introduction

The Philippine Development Plan for 2017-2023 highlights that children are among the most vulnerable population groups in society, including them in strategies for risk reduction and adaptive capacity strengthening. 1 Approximately 40% of the total Philippine population is comprised of Filipinos below 18 years of age. 2 Despite having a large portion of the Philippine population declared as vulnerable, concerning issues involving them still persist and remain unaddressed.

Among Filipino children aged 5 to 15, 10% to 15% are affected by mental health problems. 3 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 16.8% of Filipino students aged 13 to 17 have attempted suicide at least once within a year before the 2015 Global School-based Student Health survey. 4 This is just one of the many indicators showing the state of mental health of these children. These statistics involving children’s mental health are concerning as childhood is a crucial period where most mental health disorders begin. Efforts should be made to identify these issues early for proper treatment in prevention of negative health and social outcomes. 4 Childhood mental and developmental disorders also frequently persist into adulthood, making it more likely for them to have compromised growth with greater need for medical and disability services and higher risk of getting involved with law enforcement agencies. 5 In this context, the COVID-19 pandemic threatens to worsen these numbers, affecting the delivery of the Philippines’ health care services, including those for children’s mental health.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, children have been subjected to multiple threats to their mental health. Adding insult to injury, several concurrent factors in the Philippine society exacerbate this. While these are experiences shared by all people regardless of age, impediments to emotional and social development are greater in children than in adults. 6 They may also be more vulnerable to developing mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. 7 Together with these circumstances and the weakened health care system, children’s vulnerability towards mental health problems may be worsened by the pandemic, leading to more new cases and exacerbating existing ones. 2

Status of mental health system for children in the Philippines

According to the National Statistics Office (NSO), mental health illnesses rank as the third most common form of morbidity among Filipinos. 8 In the assessment conducted on the Philippine mental health system, a prevalence of 16% of mental disorders among children was reported. 9 With this alarming number of cases, it is surprising to see how the Philippines is currently responding to this problem. To date, there are only five government hospitals with psychiatric facilities for children, 84 general hospitals with psychiatric units, and 46 outpatient facilities from which there are only 11 that are designated for children and adolescents. Additionally, there are only 60 child psychiatrists practicing in the Philippines, with the majority of them practicing in urban areas such as the National Capital Region. Hence, children with mental health problems who are in rural areas have less access to such services. 10

As the pandemic continues, combined with the menace of the typhoon season, thousands of children are placed in a situation where the future is uncertain. A local study showed that youth age and students are among those with significant association to a greater psychological impact due to the pandemic. 11 In addition, UNICEF also reports that children nowadays face a trifecta of threats which include direct consequences of the disease itself, interruption in essential services, and increasing poverty and inequality. All of these can lead to higher incidences of stress, anxiety, and depression. 12

General mental health implications of COVID-19 on Filipino children

The fear and anxiety of contracting the virus, the suspension of physical classes, the disruption of regular daily routine, and the decrease of social support from school peers collectively add burden to the mental well-being of children. 7 , 13 The shift to online classes increases the burden on the mental well-being of children. Excessive use of these technologies has been associated with developmental delays and has resulted in sleep schedule disruptions. 14 This situation is aggravated by the strict implementation of the confinement of children at home. Children living with preexisting mental health concerns, 13 and living in cramped households and communities face worse circumstances.

Militarization of the Philippine COVID-19 response

Aside from being regarded as one of the countries with the longest lockdown, the Philippines has also been called out by the United Nations for employing a highly militaristic approach in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. 15 Militarization may come across as threatening, because it implies a potential for violence. 16 Furthermore, few studies abroad have reported that children and adolescents may tend to view police forces as punitive figures whom they fear. 17 , 18 While these qualitative studies were conducted long before the current health crisis began, it may be possible for increased military presence in communities to exacerbate the fears already emanating from the pandemic itself; this can negatively impact a child’s psychological development. 4 Still, local evidence to confirm these associations, especially in the context of the pandemic, is lacking. Many studies have already documented the impact of lockdown on children, but none of them have looked into how the strategies for implementation may also be contributory to their mental health or well-being.

Typhoons and the mental health of Filipino children

The Philippines has been hit by 22 tropical typhoons during the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving thousands of families homeless. 19 Children who are already frightened of COVID-19 and previous tropical storms have had to relive their experience with each new typhoon that came. In addition, children in crowded evacuation centers are at increased risk of contracting diseases and experiencing gender-based violence. 20 Given how past typhoons of similar strength and destruction have caused lasting adverse mental health effects on children, 21 the same or even worse, may be expected as a result of the more recent calamities. Super typhoons Goni and Vamco have caused further disruptions in schooling and livelihood, therefore leaving more children vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic. Those who have been forced to seek refuge in evacuation centers are at an increased risk of acquiring COVID-19, among other diseases. 20

Child Labor and Abuse in the Time of COVID-19

The COVID-19 crisis caused an unprecedented reduction in economic activity and working time, thus increasing poverty. Fewer employment opportunities and lower wages drive exploitative work. Further suppression of wages induces child labor. There may be deliberate recruitment of children to cut costs and boost earnings. 22

In addition to the threats of child labor, a study entitled The Hidden Impact of COVID-19 on Children reported that violence occurred in nearly one-third (32%) of households. Lesser household incomes were associated with more reports of violence towards children. 23 According to UNICEF, the Philippine government saw a 260% increase in online child abuse reports from March-May. Many victims are first abused by their parents, who livestream sexual violence for predators in wealthy Western nations. This occurrence resulted from job and income loss and more time spent at home due to strict quarantine measures. The abuse in children occurs at an average of 2 years before being rescued. 24

Strategies Addressing the mental health implications of COVID-19 on Filipino children

Numerous strategies have been utilized to address the mental health impacts of COVID-19 on Filipinos. With the mental health implications predicted at the beginning of the pandemic, the Psychological Association of the Philippines has compiled a list of free telemedicine consultations. As of August 24, the Philippine Red Cross has also established a COVID-19 hotline with 9790 helpline volunteers to address mental health and other similar concerns. The Department of Health has also conducted nationwide campaigns in observance of the National Mental Health Week. 25

Albeit present, these interventions are limited to the general population, and strategies specific to addressing the mental health situation of children remain scarce and staggered. Compounding factors of classifying among the lower- to middle-income countries of militarization, natural disasters, and child labor and abuse have yet to be considered. In addition, it is also important to consider that happiness, with its multifactorial nature, is a vital component of an individual’s overall wellbeing. 26

The already-challenged state of mental well-being of Filipino children has been worsened by the pandemic and the lack of good mental health policies by the government. While there is increasing awareness for mental health, children-centered interventions remain deficient. Approaches must integrate commonly-known mental health effects on children with existing and anticipated Philippine societal issues. Without doing so, it may be expected that as the COVID-19 pandemic is mitigated, a mental health epidemic will replace it.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

GZCM and DELP were involved in the conception of the paper. GZCM led the writing of the manuscript and acted as corresponding author. GZCM, MBCB, FAJA, HAAS, PBMB, ETCA and RJDT wrote sections of the manuscript. AJGE and DELP reviewed and edited the initial draft of the manuscript prior to submission. All authors have reviewed and agreed to the final version of the paper.

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

Top Schools

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main Exam

- JEE Advanced Exam

- BITSAT Exam

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Advanced Cutoff

- JEE Main Cutoff

- GATE Registration 2025

- JEE Main Syllabus 2025

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- JEE Main Question Papers

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2025

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2024

- CAT 2024 College Predictor

- Top MBA Entrance Exams 2024

- AP ICET Counselling 2024

- GD Topics for MBA

- CAT Exam Date 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Result 2024

- NEET Asnwer Key 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC 2024

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam 2024

- IIMC Entrance Exam 2024

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2025

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2025

- AP OAMDC 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET DU Cut off 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet 2024

- CUET DU CSAS Portal 2024

- CUET Response Sheet 2024

- CUET Result 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- IGNOU Result 2024

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET College Predictor 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- NIRF Ranking 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET PG Counselling 2024

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

2 Minute Speech on Covid-19 (CoronaVirus) for Students

The year, 2019, saw the discovery of a previously unknown coronavirus illness, Covid-19 . The Coronavirus has affected the way we go about our everyday lives. This pandemic has devastated millions of people, either unwell or passed away due to the sickness. The most common symptoms of this viral illness include a high temperature, a cough, bone pain, and difficulties with the respiratory system. In addition to these symptoms, patients infected with the coronavirus may also feel weariness, a sore throat, muscular discomfort, and a loss of taste or smell.

10 Lines Speech on Covid-19 for Students

The Coronavirus is a member of a family of viruses that may infect their hosts exceptionally quickly.

Humans created the Coronavirus in the city of Wuhan in China, where it first appeared.

The first confirmed case of the Coronavirus was found in India in January in the year 2020.

Protecting ourselves against the coronavirus is essential by covering our mouths and noses when we cough or sneeze to prevent the infection from spreading.

We must constantly wash our hands with antibacterial soap and face masks to protect ourselves.

To ensure our safety, the government has ordered the whole nation's closure to halt the virus's spread.

The Coronavirus forced all our classes to be taken online, as schools and institutions were shut down.

Due to the coronavirus, everyone was instructed to stay indoors throughout the lockdown.

During this period, I spent a lot of time playing games with family members.

Even though the cases of COVID-19 are a lot less now, we should still take precautions.

Short 2-Minute Speech on Covid 19 for Students

The coronavirus, also known as Covid - 19 , causes a severe illness. Those who are exposed to it become sick in their lungs. A brand-new virus is having a devastating effect throughout the globe. It's being passed from person to person via social interaction.

The first instance of Covid - 19 was discovered in December 2019 in Wuhan, China . The World Health Organization proclaimed the covid - 19 pandemic in March 2020. It has now reached every country in the globe. Droplets produced by an infected person's cough or sneeze might infect those nearby.

The severity of Covid-19 symptoms varies widely. Symptoms aren't always present. The typical symptoms are high temperatures, a dry cough, and difficulty breathing. Covid - 19 individuals also exhibit other symptoms such as weakness, a sore throat, muscular soreness, and a diminished sense of smell and taste.

Vaccination has been produced by many countries but the effectiveness of them is different for every individual. The only treatment then is to avoid contracting in the first place. We can accomplish that by following these protocols—

Put on a mask to hide your face. Use soap and hand sanitiser often to keep germs at bay.

Keep a distance of 5 to 6 feet at all times.

Never put your fingers in your mouth or nose.

Long 2-Minute Speech on Covid 19 for Students

As students, it's important for us to understand the gravity of the situation regarding the Covid-19 pandemic and the impact it has on our communities and the world at large. In this speech, I will discuss the real-world examples of the effects of the pandemic and its impact on various aspects of our lives.

Impact on Economy | The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the global economy. We have seen how businesses have been forced to close their doors, leading to widespread job loss and economic hardship. Many individuals and families have been struggling to make ends meet, and this has led to a rise in poverty and inequality.

Impact on Healthcare Systems | The pandemic has also put a strain on healthcare systems around the world. Hospitals have been overwhelmed with patients, and healthcare workers have been stretched to their limits. This has highlighted the importance of investing in healthcare systems and ensuring that they are prepared for future crises.

Impact on Education | The pandemic has also affected the education system, with schools and universities being closed around the world. This has led to a shift towards online learning and the use of technology to continue education remotely. However, it has also highlighted the digital divide, with many students from low-income backgrounds facing difficulties in accessing online learning.

Impact on Mental Health | The pandemic has not only affected our physical health but also our mental health. We have seen how the isolation and uncertainty caused by the pandemic have led to an increase in stress, anxiety, and depression. It's important that we take care of our mental health and support each other during this difficult time.

Real-life Story of a Student

John is a high school student who was determined to succeed despite the struggles brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic.

John's school closed down in the early days of the pandemic, and he quickly found himself struggling to adjust to online learning. Without the structure and support of in-person classes, John found it difficult to stay focused and motivated. He also faced challenges at home, as his parents were both essential workers and were often not available to help him with his schoolwork.

Despite these struggles, John refused to let the pandemic defeat him. He made a schedule for himself, to stay on top of his assignments and set goals for himself. He also reached out to his teachers for additional support, and they were more than happy to help.

John also found ways to stay connected with his classmates and friends, even though they were physically apart. They formed a study group and would meet regularly over Zoom to discuss their assignments and provide each other with support.

Thanks to his hard work and determination, John was able to maintain good grades and even improved in some subjects. He graduated high school on time, and was even accepted into his first-choice college.

John's story is a testament to the resilience and determination of students everywhere. Despite the challenges brought on by the pandemic, he was able to succeed and achieve his goals. He shows us that with hard work, determination, and support, we can overcome even the toughest of obstacles.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Tallentex 2025 - ALLEN's Talent Encouragement Exam

Register for Tallentex '25 - One of The Biggest Talent Encouragement Exam

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

TOEFL ® Registrations 2024

Accepted by more than 11,000 universities in over 150 countries worldwide

PTE Exam 2024 Registrations

Register now for PTE & Save 5% on English Proficiency Tests with ApplyShop Gift Cards

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

Examining cost in the context of effectiveness is essential for the field of ICT in education, given the wide variation in costs... View resource

Search form

Harnessing ai speech recognition technology for educational reading assessments amid the covid-19 pandemic in the philippines [cies 2024 presentation].

Bots and online hate during the COVID-19 pandemic: case studies in the United States and the Philippines

- Research Article

- Published: 20 October 2020

- Volume 3 , pages 445–468, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Joshua Uyheng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1631-6566 1 &

- Kathleen M. Carley 1

16k Accesses