The What: Defining a research project

During Academic Writing Month 2018, TAA hosted a series of #AcWriChat TweetChat events focused on the five W’s of academic writing. Throughout the series we explored The What: Defining a research project ; The Where: Constructing an effective writing environment ; The When: Setting realistic timeframes for your research ; The Who: Finding key sources in the existing literature ; and The Why: Explaining the significance of your research . This series of posts brings together the discussions and resources from those events. Let’s start with The What: Defining a research project .

Before moving forward on any academic writing effort, it is important to understand what the research project is intended to understand and document. In order to accomplish this, it’s also important to understand what a research project is. This is where we began our discussion of the five W’s of academic writing.

Q1: What constitutes a research project?

According to a Rutgers University resource titled, Definition of a research project and specifications for fulfilling the requirement , “A research project is a scientific endeavor to answer a research question.” Specifically, projects may take the form of “case series, case control study, cohort study, randomized, controlled trial, survey, or secondary data analysis such as decision analysis, cost effectiveness analysis or meta-analysis”.

Hampshire College offers that “Research is a process of systematic inquiry that entails collection of data; documentation of critical information; and analysis and interpretation of that data/information, in accordance with suitable methodologies set by specific professional fields and academic disciplines.” in their online resource titled, What is research? The resource also states that “Research is conducted to evaluate the validity of a hypothesis or an interpretive framework; to assemble a body of substantive knowledge and findings for sharing them in appropriate manners; and to generate questions for further inquiries.”

TweetChat participant @TheInfoSherpa , who is currently “investigating whether publishing in a predatory journal constitutes blatant research misconduct, inappropriate conduct, or questionable conduct,” summarized these ideas stating, “At its simplest, a research project is a project which seeks to answer a well-defined question or set of related questions about a specific topic.” TAA staff member, Eric Schmieder, added to the discussion that“a research project is a process by which answers to a significant question are attempted to be answered through exploration or experimentation.”

In a learning module focused on research and the application of the Scientific Method, the Office of Research Integrity within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services states that “Research is a process to discover new knowledge…. No matter what topic is being studied, the value of the research depends on how well it is designed and done.”

Wenyi Ho of Penn State University states that “Research is a systematic inquiry to describe, explain, predict and control the observed phenomenon.” in an online resource which further shares four types of knowledge that research contributes to education, four types of research based on different purposes, and five stages of conducting a research study. Further understanding of research in definition, purpose, and typical research practices can be found in this Study.com video resource .

Now that we have a foundational understanding of what constitutes a research project, we shift the discussion to several questions about defining specific research topics.

Q2: When considering topics for a new research project, where do you start?

A guide from the University of Michigan-Flint on selecting a topic states, “Be aware that selecting a good topic may not be easy. It must be narrow and focused enough to be interesting, yet broad enough to find adequate information.”

Schmieder responded to the chat question with his approach.“I often start with an idea or question of interest to me and then begin searching for existing research on the topic to determine what has been done already.”

@TheInfoSherpa added, “Start with the research. Ask a librarian for help. The last thing you want to do is design a study thst someone’s already done.”

The Utah State University Libraries shared a video that “helps you find a research topic that is relevant and interesting to you!”

Q2a: What strategies do you use to stay current on research in your discipline?

The California State University Chancellor’s Doctoral Incentive Program Community Commons resource offers four suggestions for staying current in your field:

- Become an effective consumer of research

- Read key publications

- Attend key gatherings

- Develop a network of colleagues

Schmieder and @TheInfoSherpa discussed ways to use databases for this purpose. Schmieder identified using “journal database searches for publications in the past few months on topics of interest” as a way to stay current as a consumer of research.

@TheInfoSherpa added, “It’s so easy to set up an alert in your favorite database. I do this for specific topics, and all the latest research gets delivered right to my inbox. Again, your academic or public #librarian can help you with this.” To which Schmieder replied, “Alerts are such useful advancements in technology for sorting through the myriad of material available online. Great advice!”

In an open access article, Keeping Up to Date: An Academic Researcher’s Information Journey , researchers Pontis, et. al. “examined how researchers stay up to date, using the information journey model as a framework for analysis and investigating which dimensions influence information behaviors.” As a result of their study, “Five key dimensions that influence information behaviors were identified: level of seniority, information sources, state of the project, level of familiarity, and how well defined the relevant community is.”

Q3: When defining a research topic, do you tend to start with a broad idea or a specific research question?

In a collection of notes on where to start by Don Davis at Columbia University, Davis tells us “First, there is no ‘Right Topic.’”, adding that “Much more important is to find something that is important and genuinely interests you.”

Schmieder shared in the chat event, “I tend to get lost in the details while trying to save the world – not sure really where I start though. :O)” @TheInfoSherpa added, “Depends on the project. The important thing is being able to realize when your topic is too broad or too narrow and may need tweaking. I use the five Ws or PICO(T) to adjust my topic if it’s too broad or too narrow.”

In an online resource , The Writing Center at George Mason University identifies the following six steps to developing a research question, noting significance in that “the specificity of a well-developed research question helps writers avoid the ‘all-about’ paper and work toward supporting a specific, arguable thesis.”

- Choose an interesting general topic

- Do some preliminary research on your general topic

- Consider your audience

- Start asking questions

- Evaluate your question

- Begin your research

USC Libraries’ research guides offer eight strategies for narrowing the research topic : Aspect, Components, Methodology, Place, Relationship, Time, Type, or a Combination of the above.

Q4: What factors help to determine the realistic scope a research topic?

The scope of a research topic refers to the actual amount of research conducted as part of the study. Often the search strategies used in understanding previous research and knowledge on a topic will impact the scope of the current study. A resource from Indiana University offers both an activity for narrowing the search strategy when finding too much information on a topic and an activity for broadening the search strategy when too little information is found.

The Mayfield Handbook of Technical & Scientific Writing identifies scope as an element to be included in the problem statement. Further when discussing problem statements, this resource states, “If you are focusing on a problem, be sure to define and state it specifically enough that you can write about it. Avoid trying to investigate or write about multiple problems or about broad or overly ambitious problems. Vague problem definition leads to unsuccessful proposals and vague, unmanageable documents. Naming a topic is not the same as defining a problem.”

Schmieder identified in the chat several considerations when determining the scope of a research topic, namely “Time, money, interest and commitment, impact to self and others.” @TheInfoSherpa reiterated their use of PICO(T) stating, “PICO(T) is used in the health sciences, but it can be used to identify a manageable scope” and sharing a link to a Georgia Gwinnett College Research Guide on PICOT Questions .

By managing the scope of your research topic, you also define the limitations of your study. According to a USC Libraries’ Research Guide, “The limitations of the study are those characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from your research.” Accepting limitations help maintain a manageable scope moving forward with the project.

Q5/5a: Do you generally conduct research alone or with collaborative authors? What benefits/challenges do collaborators add to the research project?

Despite noting that the majority of his research efforts have been solo, Schmieder did identify benefits to collaboration including “brainstorming, division of labor, speed of execution” and challenges of developing a shared vision, defining roles and responsibilities for the collaborators, and accepting a level of dependence on the others in the group.

In a resource on group writing from The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, both advantages and pitfalls are discussed. Looking to the positive, this resource notes that “Writing in a group can have many benefits: multiple brains are better than one, both for generating ideas and for getting a job done.”

Yale University’s Office of the Provost has established, as part of its Academic Integrity policies, Guidance on Authorship in Scholarly or Scientific Publications to assist researchers in understanding authorship standards as well as attribution expectations.

In times when authorship turns sour , the University of California, San Francisco offers the following advice to reach a resolution among collaborative authors:

- Address emotional issues directly

- Elicit the problem author’s emotions

- Acknowledge the problem author’s emotions

- Express your own emotions as “I feel …”

- Set boundaries

- Try to find common ground

- Get agreement on process

- Involve a neutral third party

Q6: What other advice can you share about defining a research project?

Schmieder answered with question with personal advice to “Choose a topic of interest. If you aren’t interested in the topic, you will either not stay motivated to complete it or you will be miserable in the process and not produce the best results from your efforts.”

For further guidance and advice, the following resources may prove useful:

- 15 Steps to Good Research (Georgetown University Library)

- Advice for Researchers and Students (Tao Xie and University of Illinois)

- Develop a research statement for yourself (University of Pennsylvania)

Whatever your next research project, hopefully these tips and resources help you to define it in a way that leads to greater success and better writing.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Please note that all content on this site is copyrighted by the Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Individual articles may be reposted and/or printed in non-commercial publications provided you include the byline (if applicable), the entire article without alterations, and this copyright notice: “© 2024, Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Originally published on the TAA Blog, Abstrac t on [Date, Issue, Number].” A copy of the issue in which the article is reprinted, or a link to the blog or online site, should be mailed to Kim Pawlak P.O. Box 337, Cochrane, WI 54622 or Kim.Pawlak @taaonline.net.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Pharmacol Pharmacother

- v.4(2); Apr-Jun 2013

The critical steps for successful research: The research proposal and scientific writing: (A report on the pre-conference workshop held in conjunction with the 64 th annual conference of the Indian Pharmaceutical Congress-2012)

Pitchai balakumar.

Pharmacology Unit, Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Semeling, 08100 Bedong. Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia

Mohammed Naseeruddin Inamdar

1 Department of Pharmacology, Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

2 Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, USA

An interactive workshop on ‘The Critical Steps for Successful Research: The Research Proposal and Scientific Writing’ was conducted in conjunction with the 64 th Annual Conference of the Indian Pharmaceutical Congress-2012 at Chennai, India. In essence, research is performed to enlighten our understanding of a contemporary issue relevant to the needs of society. To accomplish this, a researcher begins search for a novel topic based on purpose, creativity, critical thinking, and logic. This leads to the fundamental pieces of the research endeavor: Question, objective, hypothesis, experimental tools to test the hypothesis, methodology, and data analysis. When correctly performed, research should produce new knowledge. The four cornerstones of good research are the well-formulated protocol or proposal that is well executed, analyzed, discussed and concluded. This recent workshop educated researchers in the critical steps involved in the development of a scientific idea to its successful execution and eventual publication.

INTRODUCTION

Creativity and critical thinking are of particular importance in scientific research. Basically, research is original investigation undertaken to gain knowledge and understand concepts in major subject areas of specialization, and includes the generation of ideas and information leading to new or substantially improved scientific insights with relevance to the needs of society. Hence, the primary objective of research is to produce new knowledge. Research is both theoretical and empirical. It is theoretical because the starting point of scientific research is the conceptualization of a research topic and development of a research question and hypothesis. Research is empirical (practical) because all of the planned studies involve a series of observations, measurements, and analyses of data that are all based on proper experimental design.[ 1 – 9 ]

The subject of this report is to inform readers of the proceedings from a recent workshop organized by the 64 th Annual conference of the ‘ Indian Pharmaceutical Congress ’ at SRM University, Chennai, India, from 05 to 06 December 2012. The objectives of the workshop titled ‘The Critical Steps for Successful Research: The Research Proposal and Scientific Writing,’ were to assist participants in developing a strong fundamental understanding of how best to develop a research or study protocol, and communicate those research findings in a conference setting or scientific journal. Completing any research project requires meticulous planning, experimental design and execution, and compilation and publication of findings in the form of a research paper. All of these are often unfamiliar to naïve researchers; thus, the purpose of this workshop was to teach participants to master the critical steps involved in the development of an idea to its execution and eventual publication of the results (See the last section for a list of learning objectives).

THE STRUCTURE OF THE WORKSHOP

The two-day workshop was formatted to include key lectures and interactive breakout sessions that focused on protocol development in six subject areas of the pharmaceutical sciences. This was followed by sessions on scientific writing. DAY 1 taught the basic concepts of scientific research, including: (1) how to formulate a topic for research and to describe the what, why , and how of the protocol, (2) biomedical literature search and review, (3) study designs, statistical concepts, and result analyses, and (4) publication ethics. DAY 2 educated the attendees on the basic elements and logistics of writing a scientific paper and thesis, and preparation of poster as well as oral presentations.

The final phase of the workshop was the ‘Panel Discussion,’ including ‘Feedback/Comments’ by participants. There were thirteen distinguished speakers from India and abroad. Approximately 120 post-graduate and pre-doctoral students, young faculty members, and scientists representing industries attended the workshop from different parts of the country. All participants received a printed copy of the workshop manual and supporting materials on statistical analyses of data.

THE BASIC CONCEPTS OF RESEARCH: THE KEY TO GETTING STARTED IN RESEARCH

A research project generally comprises four key components: (1) writing a protocol, (2) performing experiments, (3) tabulating and analyzing data, and (4) writing a thesis or manuscript for publication.

Fundamentals in the research process

A protocol, whether experimental or clinical, serves as a navigator that evolves from a basic outline of the study plan to become a qualified research or grant proposal. It provides the structural support for the research. Dr. G. Jagadeesh (US FDA), the first speaker of the session, spoke on ‘ Fundamentals in research process and cornerstones of a research project .’ He discussed at length the developmental and structural processes in preparing a research protocol. A systematic and step-by-step approach is necessary in planning a study. Without a well-designed protocol, there would be a little chance for successful completion of a research project or an experiment.

Research topic

The first and the foremost difficult task in research is to identify a topic for investigation. The research topic is the keystone of the entire scientific enterprise. It begins the project, drives the entire study, and is crucial for moving the project forward. It dictates the remaining elements of the study [ Table 1 ] and thus, it should not be too narrow or too broad or unfocused. Because of these potential pitfalls, it is essential that a good or novel scientific idea be based on a sound concept. Creativity, critical thinking, and logic are required to generate new concepts and ideas in solving a research problem. Creativity involves critical thinking and is associated with generating many ideas. Critical thinking is analytical, judgmental, and involves evaluating choices before making a decision.[ 4 ] Thus, critical thinking is convergent type thinking that narrows and refines those divergent ideas and finally settles to one idea for an in-depth study. The idea on which a research project is built should be novel, appropriate to achieve within the existing conditions, and useful to the society at large. Therefore, creativity and critical thinking assist biomedical scientists in research that results in funding support, novel discovery, and publication.[ 1 , 4 ]

Elements of a study protocol

Research question

The next most crucial aspect of a study protocol is identifying a research question. It should be a thought-provoking question. The question sets the framework. It emerges from the title, findings/results, and problems observed in previous studies. Thus, mastering the literature, attendance at conferences, and discussion in journal clubs/seminars are sources for developing research questions. Consider the following example in developing related research questions from the research topic.

Hepatoprotective activity of Terminalia arjuna and Apium graveolens on paracetamol-induced liver damage in albino rats.

How is paracetamol metabolized in the body? Does it involve P450 enzymes? How does paracetamol cause liver injury? What are the mechanisms by which drugs can alleviate liver damage? What biochemical parameters are indicative of liver injury? What major endogenous inflammatory molecules are involved in paracetamol-induced liver damage?

A research question is broken down into more precise objectives. The objectives lead to more precise methods and definition of key terms. The objectives should be SMART-Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-framed,[ 10 ] and should cover the entire breadth of the project. The objectives are sometimes organized into hierarchies: Primary, secondary, and exploratory; or simply general and specific. Study the following example:

To evaluate the safety and tolerability of single oral doses of compound X in normal volunteers.

To assess the pharmacokinetic profile of compound X following single oral doses.

To evaluate the incidence of peripheral edema reported as an adverse event.

The objectives and research questions are then formulated into a workable or testable hypothesis. The latter forces us to think carefully about what comparisons will be needed to answer the research question, and establishes the format for applying statistical tests to interpret the results. The hypothesis should link a process to an existing or postulated biologic pathway. A hypothesis is written in a form that can yield measurable results. Studies that utilize statistics to compare groups of data should have a hypothesis. Consider the following example:

- The hepatoprotective activity of Terminalia arjuna is superior to that of Apium graveolens against paracetamol-induced liver damage in albino rats.

All biological research, including discovery science, is hypothesis-driven. However, not all studies need be conducted with a hypothesis. For example, descriptive studies (e.g., describing characteristics of a plant, or a chemical compound) do not need a hypothesis.[ 1 ]

Relevance of the study

Another important section to be included in the protocol is ‘significance of the study.’ Its purpose is to justify the need for the research that is being proposed (e.g., development of a vaccine for a disease). In summary, the proposed study should demonstrate that it represents an advancement in understanding and that the eventual results will be meaningful, contribute to the field, and possibly even impact society.

Biomedical literature

A literature search may be defined as the process of examining published sources of information on a research or review topic, thesis, grant application, chemical, drug, disease, or clinical trial, etc. The quantity of information available in print or electronically (e.g., the internet) is immense and growing with time. A researcher should be familiar with the right kinds of databases and search engines to extract the needed information.[ 3 , 6 ]

Dr. P. Balakumar (Institute of Pharmacy, Rajendra Institute of Technology and Sciences, Sirsa, Haryana; currently, Faculty of Pharmacy, AIMST University, Malaysia) spoke on ‘ Biomedical literature: Searching, reviewing and referencing .’ He schematically explained the basis of scientific literature, designing a literature review, and searching literature. After an introduction to the genesis and diverse sources of scientific literature searches, the use of PubMed, one of the premier databases used for biomedical literature searches world-wide, was illustrated with examples and screenshots. Several companion databases and search engines are also used for finding information related to health sciences, and they include Embase, Web of Science, SciFinder, The Cochrane Library, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, Scopus, and Google Scholar.[ 3 ] Literature searches using alternative interfaces for PubMed such as GoPubMed, Quertle, PubFocus, Pubget, and BibliMed were discussed. The participants were additionally informed of databases on chemistry, drugs and drug targets, clinical trials, toxicology, and laboratory animals (reviewed in ref[ 3 ]).

Referencing and bibliography are essential in scientific writing and publication.[ 7 ] Referencing systems are broadly classified into two major types, such as Parenthetical and Notation systems. Parenthetical referencing is also known as Harvard style of referencing, while Vancouver referencing style and ‘Footnote’ or ‘Endnote’ are placed under Notation referencing systems. The participants were educated on each referencing system with examples.

Bibliography management

Dr. Raj Rajasekaran (University of California at San Diego, CA, USA) enlightened the audience on ‘ bibliography management ’ using reference management software programs such as Reference Manager ® , Endnote ® , and Zotero ® for creating and formatting bibliographies while writing a manuscript for publication. The discussion focused on the use of bibliography management software in avoiding common mistakes such as incomplete references. Important steps in bibliography management, such as creating reference libraries/databases, searching for references using PubMed/Google scholar, selecting and transferring selected references into a library, inserting citations into a research article and formatting bibliographies, were presented. A demonstration of Zotero®, a freely available reference management program, included the salient features of the software, adding references from PubMed using PubMed ID, inserting citations and formatting using different styles.

Writing experimental protocols

The workshop systematically instructed the participants in writing ‘ experimental protocols ’ in six disciplines of Pharmaceutical Sciences.: (1) Pharmaceutical Chemistry (presented by Dr. P. V. Bharatam, NIPER, Mohali, Punjab); (2) Pharmacology (presented by Dr. G. Jagadeesh and Dr. P. Balakumar); (3) Pharmaceutics (presented by Dr. Jayant Khandare, Piramal Life Sciences, Mumbai); (4) Pharmacy Practice (presented by Dr. Shobha Hiremath, Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru); (5) Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry (presented by Dr. Salma Khanam, Al-Ameen College of Pharmacy, Bengaluru); and (6) Pharmaceutical Analysis (presented by Dr. Saranjit Singh, NIPER, Mohali, Punjab). The purpose of the research plan is to describe the what (Specific Aims/Objectives), why (Background and Significance), and how (Design and Methods) of the proposal.

The research plan should answer the following questions: (a) what do you intend to do; (b) what has already been done in general, and what have other researchers done in the field; (c) why is this worth doing; (d) how is it innovative; (e) what will this new work add to existing knowledge; and (f) how will the research be accomplished?

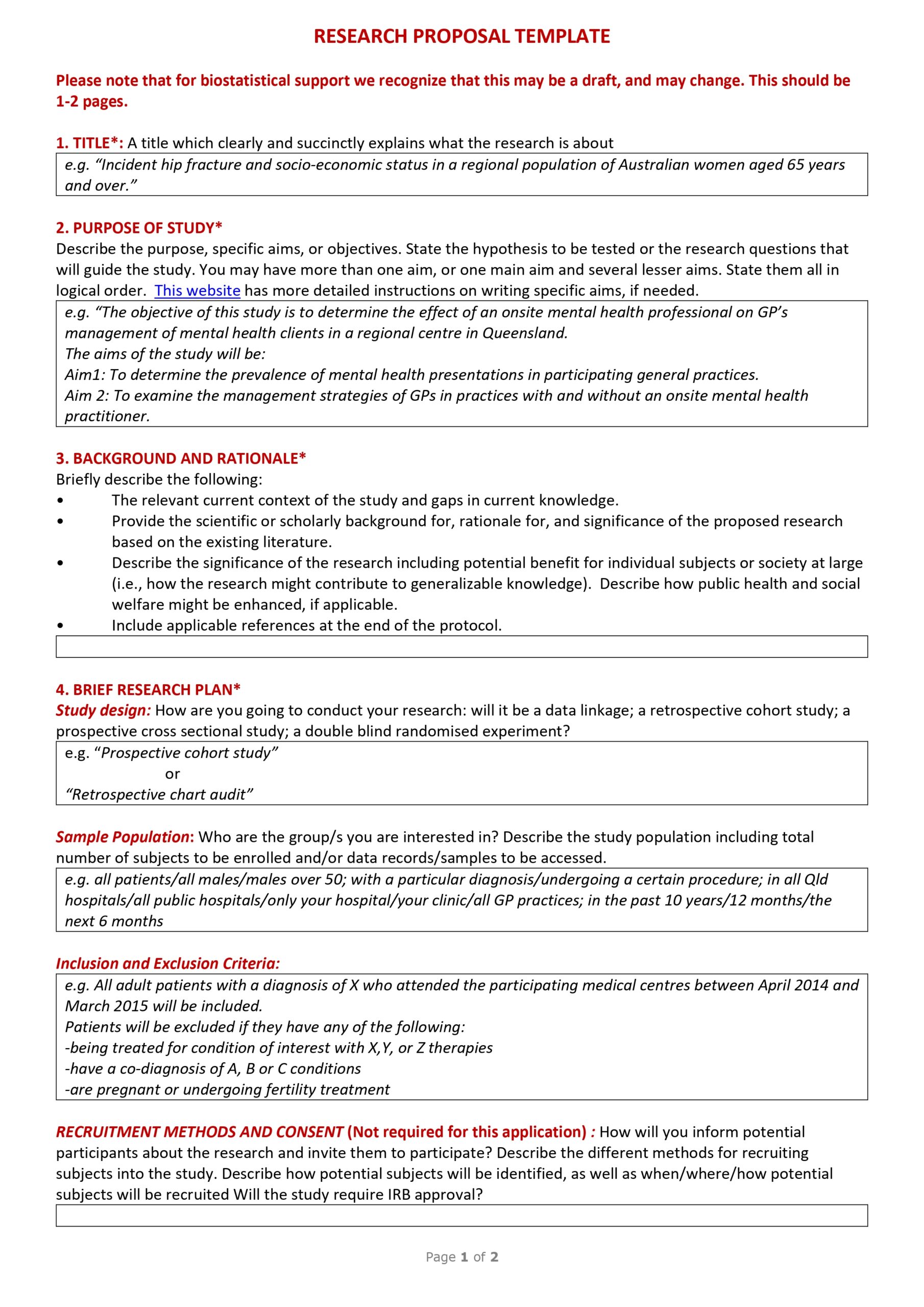

In general, the format used by the faculty in all subjects is shown in Table 2 .

Elements of a research protocol

Biostatistics

Biostatistics is a key component of biomedical research. Highly reputed journals like The Lancet, BMJ, Journal of the American Medical Association, and many other biomedical journals include biostatisticians on their editorial board or reviewers list. This indicates that a great importance is given for learning and correctly employing appropriate statistical methods in biomedical research. The post-lunch session on day 1 of the workshop was largely committed to discussion on ‘ Basic biostatistics .’ Dr. R. Raveendran (JIPMER, Puducherry) and Dr. Avijit Hazra (PGIMER, Kolkata) reviewed, in parallel sessions, descriptive statistics, probability concepts, sample size calculation, choosing a statistical test, confidence intervals, hypothesis testing and ‘ P ’ values, parametric and non-parametric statistical tests, including analysis of variance (ANOVA), t tests, Chi-square test, type I and type II errors, correlation and regression, and summary statistics. This was followed by a practice and demonstration session. Statistics CD, compiled by Dr. Raveendran, was distributed to the participants before the session began and was demonstrated live. Both speakers worked on a variety of problems that involved both clinical and experimental data. They discussed through examples the experimental designs encountered in a variety of studies and statistical analyses performed for different types of data. For the benefit of readers, we have summarized statistical tests applied frequently for different experimental designs and post-hoc tests [ Figure 1 ].

Conceptual framework for statistical analyses of data. Of the two kinds of variables, qualitative (categorical) and quantitative (numerical), qualitative variables (nominal or ordinal) are not normally distributed. Numerical data that come from normal distributions are analyzed using parametric tests, if not; the data are analyzed using non-parametric tests. The most popularly used Student's t -test compares the means of two populations, data for this test could be paired or unpaired. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) is used to compare the means of three or more independent populations that are normally distributed. Applying t test repeatedly in pair (multiple comparison), to compare the means of more than two populations, will increase the probability of type I error (false positive). In this case, for proper interpretation, we need to adjust the P values. Repeated measures ANOVA is used to compare the population means if more than two observations coming from same subject over time. The null hypothesis is rejected with a ‘ P ’ value of less than 0.05, and the difference in population means is considered to be statistically significant. Subsequently, appropriate post-hoc tests are used for pairwise comparisons of population means. Two-way or three-way ANOVA are considered if two (diet, dose) or three (diet, dose, strain) independent factors, respectively, are analyzed in an experiment (not described in the Figure). Categorical nominal unmatched variables (counts or frequencies) are analyzed by Chi-square test (not shown in the Figure)

Research and publication ethics

The legitimate pursuit of scientific creativity is unfortunately being marred by a simultaneous increase in scientific misconduct. A disproportionate share of allegations involves scientists of many countries, and even from respected laboratories. Misconduct destroys faith in science and scientists and creates a hierarchy of fraudsters. Investigating misconduct also steals valuable time and resources. In spite of these facts, most researchers are not aware of publication ethics.

Day 1 of the workshop ended with a presentation on ‘ research and publication ethics ’ by Dr. M. K. Unnikrishnan (College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal University, Manipal). He spoke on the essentials of publication ethics that included plagiarism (attempting to take credit of the work of others), self-plagiarism (multiple publications by an author on the same content of work with slightly different wordings), falsification (manipulation of research data and processes and omitting critical data or results), gift authorship (guest authorship), ghostwriting (someone other than the named author (s) makes a major contribution), salami publishing (publishing many papers, with minor differences, from the same study), and sabotage (distracting the research works of others to halt their research completion). Additionally, Dr. Unnikrishnan pointed out the ‘ Ingelfinger rule ’ of stipulating that a scientist must not submit the same original research in two different journals. He also advised the audience that authorship is not just credit for the work but also responsibility for scientific contents of a paper. Although some Indian Universities are instituting preventive measures (e.g., use of plagiarism detecting software, Shodhganga digital archiving of doctoral theses), Dr. Unnikrishnan argued for a great need to sensitize young researchers on the nature and implications of scientific misconduct. Finally, he discussed methods on how editors and peer reviewers should ethically conduct themselves while managing a manuscript for publication.

SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATION: THE KEY TO SUCCESSFUL SELLING OF FINDINGS

Research outcomes are measured through quality publications. Scientists must not only ‘do’ science but must ‘write’ science. The story of the project must be told in a clear, simple language weaving in previous work done in the field, answering the research question, and addressing the hypothesis set forth at the beginning of the study. Scientific publication is an organic process of planning, researching, drafting, revising, and updating the current knowledge for future perspectives. Writing a research paper is no easier than the research itself. The lectures of Day 2 of the workshop dealt with the basic elements and logistics of writing a scientific paper.

An overview of paper structure and thesis writing

Dr. Amitabh Prakash (Adis, Auckland, New Zealand) spoke on ‘ Learning how to write a good scientific paper .’ His presentation described the essential components of an original research paper and thesis (e.g., introduction, methods, results, and discussion [IMRaD]) and provided guidance on the correct order, in which data should appear within these sections. The characteristics of a good abstract and title and the creation of appropriate key words were discussed. Dr. Prakash suggested that the ‘title of a paper’ might perhaps have a chance to make a good impression, and the title might be either indicative (title that gives the purpose of the study) or declarative (title that gives the study conclusion). He also suggested that an abstract is a succinct summary of a research paper, and it should be specific, clear, and concise, and should have IMRaD structure in brief, followed by key words. Selection of appropriate papers to be cited in the reference list was also discussed. Various unethical authorships were enumerated, and ‘The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship’ was explained ( http://www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html ; also see Table 1 in reference #9). The session highlighted the need for transparency in medical publication and provided a clear description of items that needed to be included in the ‘Disclosures’ section (e.g., sources of funding for the study and potential conflicts of interest of all authors, etc.) and ‘Acknowledgements’ section (e.g., writing assistance and input from all individuals who did not meet the authorship criteria). The final part of the presentation was devoted to thesis writing, and Dr. Prakash provided the audience with a list of common mistakes that are frequently encountered when writing a manuscript.

The backbone of a study is description of results through Text, Tables, and Figures. Dr. S. B. Deshpande (Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India) spoke on ‘ Effective Presentation of Results .’ The Results section deals with the observations made by the authors and thus, is not hypothetical. This section is subdivided into three segments, that is, descriptive form of the Text, providing numerical data in Tables, and visualizing the observations in Graphs or Figures. All these are arranged in a sequential order to address the question hypothesized in the Introduction. The description in Text provides clear content of the findings highlighting the observations. It should not be the repetition of facts in tables or graphs. Tables are used to summarize or emphasize descriptive content in the text or to present the numerical data that are unrelated. Illustrations should be used when the evidence bearing on the conclusions of a paper cannot be adequately presented in a written description or in a Table. Tables or Figures should relate to each other logically in sequence and should be clear by themselves. Furthermore, the discussion is based entirely on these observations. Additionally, how the results are applied to further research in the field to advance our understanding of research questions was discussed.

Dr. Peush Sahni (All-India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi) spoke on effectively ‘ structuring the Discussion ’ for a research paper. The Discussion section deals with a systematic interpretation of study results within the available knowledge. He said the section should begin with the most important point relating to the subject studied, focusing on key issues, providing link sentences between paragraphs, and ensuring the flow of text. Points were made to avoid history, not repeat all the results, and provide limitations of the study. The strengths and novel findings of the study should be provided in the discussion, and it should open avenues for future research and new questions. The Discussion section should end with a conclusion stating the summary of key findings. Dr. Sahni gave an example from a published paper for writing a Discussion. In another presentation titled ‘ Writing an effective title and the abstract ,’ Dr. Sahni described the important components of a good title, such as, it should be simple, concise, informative, interesting and eye-catching, accurate and specific about the paper's content, and should state the subject in full indicating study design and animal species. Dr. Sahni explained structured (IMRaD) and unstructured abstracts and discussed a few selected examples with the audience.

Language and style in publication

The next lecture of Dr. Amitabh Prakash on ‘ Language and style in scientific writing: Importance of terseness, shortness and clarity in writing ’ focused on the actual sentence construction, language, grammar and punctuation in scientific manuscripts. His presentation emphasized the importance of brevity and clarity in the writing of manuscripts describing biomedical research. Starting with a guide to the appropriate construction of sentences and paragraphs, attendees were given a brief overview of the correct use of punctuation with interactive examples. Dr. Prakash discussed common errors in grammar and proactively sought audience participation in correcting some examples. Additional discussion was centered on discouraging the use of redundant and expendable words, jargon, and the use of adjectives with incomparable words. The session ended with a discussion of words and phrases that are commonly misused (e.g., data vs . datum, affect vs . effect, among vs . between, dose vs . dosage, and efficacy/efficacious vs . effective/effectiveness) in biomedical research manuscripts.

Working with journals

The appropriateness in selecting the journal for submission and acceptance of the manuscript should be determined by the experience of an author. The corresponding author must have a rationale in choosing the appropriate journal, and this depends upon the scope of the study and the quality of work performed. Dr. Amitabh Prakash spoke on ‘ Working with journals: Selecting a journal, cover letter, peer review process and impact factor ’ by instructing the audience in assessing the true value of a journal, understanding principles involved in the peer review processes, providing tips on making an initial approach to the editorial office, and drafting an appropriate cover letter to accompany the submission. His presentation defined the metrics that are most commonly used to measure journal quality (e.g., impact factor™, Eigenfactor™ score, Article Influence™ score, SCOPUS 2-year citation data, SCImago Journal Rank, h-Index, etc.) and guided attendees on the relative advantages and disadvantages of using each metric. Factors to consider when assessing journal quality were discussed, and the audience was educated on the ‘green’ and ‘gold’ open access publication models. Various peer review models (e.g., double-blind, single-blind, non-blind) were described together with the role of the journal editor in assessing manuscripts and selecting suitable reviewers. A typical checklist sent to referees was shared with the attendees, and clear guidance was provided on the best way to address referee feedback. The session concluded with a discussion of the potential drawbacks of the current peer review system.

Poster and oral presentations at conferences

Posters have become an increasingly popular mode of presentation at conferences, as it can accommodate more papers per meeting, has no time constraint, provides a better presenter-audience interaction, and allows one to select and attend papers of interest. In Figure 2 , we provide instructions, design, and layout in preparing a scientific poster. In the final presentation, Dr. Sahni provided the audience with step-by-step instructions on how to write and format posters for layout, content, font size, color, and graphics. Attendees were given specific guidance on the format of text on slides, the use of color, font type and size, and the use of illustrations and multimedia effects. Moreover, the importance of practical tips while delivering oral or poster presentation was provided to the audience, such as speak slowly and clearly, be informative, maintain eye contact, and listen to the questions from judges/audience carefully before coming up with an answer.

Guidelines and design to scientific poster presentation. The objective of scientific posters is to present laboratory work in scientific meetings. A poster is an excellent means of communicating scientific work, because it is a graphic representation of data. Posters should have focus points, and the intended message should be clearly conveyed through simple sections: Text, Tables, and Graphs. Posters should be clear, succinct, striking, and eye-catching. Colors should be used only where necessary. Use one font (Arial or Times New Roman) throughout. Fancy fonts should be avoided. All headings should have font size of 44, and be in bold capital letters. Size of Title may be a bit larger; subheading: Font size of 36, bold and caps. References and Acknowledgments, if any, should have font size of 24. Text should have font size between 24 and 30, in order to be legible from a distance of 3 to 6 feet. Do not use lengthy notes

PANEL DISCUSSION: FEEDBACK AND COMMENTS BY PARTICIPANTS

After all the presentations were made, Dr. Jagadeesh began a panel discussion that included all speakers. The discussion was aimed at what we do currently and could do in the future with respect to ‘developing a research question and then writing an effective thesis proposal/protocol followed by publication.’ Dr. Jagadeesh asked the following questions to the panelists, while receiving questions/suggestions from the participants and panelists.

- Does a Post-Graduate or Ph.D. student receive adequate training, either through an institutional course, a workshop of the present nature, or from the guide?

- Are these Post-Graduates self-taught (like most of us who learnt the hard way)?

- How are these guides trained? How do we train them to become more efficient mentors?

- Does a Post-Graduate or Ph.D. student struggle to find a method (s) to carry out studies? To what extent do seniors/guides help a post graduate overcome technical difficulties? How difficult is it for a student to find chemicals, reagents, instruments, and technical help in conducting studies?

- Analyses of data and interpretation: Most students struggle without adequate guidance.

- Thesis and publications frequently feature inadequate/incorrect statistical analyses and representation of data in tables/graphs. The student, their guide, and the reviewers all share equal responsibility.

- Who initiates and drafts the research paper? The Post-Graduate or their guide?

- What kind of assistance does a Post-Graduate get from the guide in finalizing a paper for publication?

- Does the guide insist that each Post-Graduate thesis yield at least one paper, and each Ph.D. thesis more than two papers, plus a review article?

The panelists and audience expressed a variety of views, but were unable to arrive at a decisive conclusion.

WHAT HAVE THE PARTICIPANTS LEARNED?

At the end of this fast-moving two-day workshop, the participants had opportunities in learning the following topics:

- Sequential steps in developing a study protocol, from choosing a research topic to developing research questions and a hypothesis.

- Study protocols on different topics in their subject of specialization

- Searching and reviewing the literature

- Appropriate statistical analyses in biomedical research

- Scientific ethics in publication

- Writing and understanding the components of a research paper (IMRaD)

- Recognizing the value of good title, running title, abstract, key words, etc

- Importance of Tables and Figures in the Results section, and their importance in describing findings

- Evidence-based Discussion in a research paper

- Language and style in writing a paper and expert tips on getting it published

- Presentation of research findings at a conference (oral and poster).

Overall, the workshop was deemed very helpful to participants. The participants rated the quality of workshop from “ satisfied ” to “ very satisfied .” A significant number of participants were of the opinion that the time allotted for each presentation was short and thus, be extended from the present two days to four days with adequate time to ask questions. In addition, a ‘hands-on’ session should be introduced for writing a proposal and manuscript. A large number of attendees expressed their desire to attend a similar workshop, if conducted, in the near future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully express our gratitude to the Organizing Committee, especially Professors K. Chinnasamy, B. G. Shivananda, N. Udupa, Jerad Suresh, Padma Parekh, A. P. Basavarajappa, Mr. S. V. Veerramani, Mr. J. Jayaseelan, and all volunteers of the SRM University. We thank Dr. Thomas Papoian (US FDA) for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The opinions expressed herein are those of Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Food and Drug Administration

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

What is a Research Design? Definition, Types, Methods and Examples

By Nick Jain

Published on: September 8, 2023

Table of Contents

What is a Research Design?

10 types of research design, top 16 research design methods, research design examples.

A research design is defined as the overall plan or structure that guides the process of conducting research. It is a critical component of the research process and serves as a blueprint for how a study will be carried out, including the methods and techniques that will be used to collect and analyze data. A well-designed research study is essential for ensuring that the research objectives are met and that the results are valid and reliable.

Key elements of research design include:

- Research Objectives: Clearly define the goals and objectives of the research study. What is the research trying to achieve or investigate?

- Research Questions or Hypotheses: Formulating specific research questions or hypotheses that address the objectives of the study. These questions guide the research process.

- Data Collection Methods: Determining how data will be collected, whether through surveys, experiments, observations, interviews, archival research, or a combination of these methods.

- Sampling: Deciding on the target population and selecting a sample that represents that population. Sampling methods can vary, such as random sampling, stratified sampling, or convenience sampling.

- Data Collection Instruments: Developing or selecting the tools and instruments needed to collect data, such as questionnaires, surveys, or experimental equipment.

- Data Analysis: Defining the statistical or analytical techniques that will be used to analyze the collected data. This may involve qualitative or quantitative methods , depending on the research goals.

- Time Frame: Establishing a timeline for the research project, including when data will be collected, analyzed, and reported.

- Ethical Considerations: Addressing ethical issues, including obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of data, and adhering to ethical guidelines.

- Resources: Identifying the resources needed for the research , including funding, personnel, equipment, and access to data sources.

- Data Presentation and Reporting: Planning how the research findings will be presented and reported, whether through written reports, presentations, or other formats.

There are various research designs, such as experimental, observational, survey, case study, and longitudinal designs, each suited to different research questions and objectives. The choice of research design depends on the nature of the research and the goals of the study.

A well-constructed research design is crucial because it helps ensure the validity, reliability, and generalizability of research findings, allowing researchers to draw meaningful conclusions and contribute to the body of knowledge in their field.

Understanding the intricate tapestry of research design is pivotal for steering your investigations toward unparalleled success. Dive deep into the realm of methodologies, where precision meets impact, and craft tailored approaches to illuminate every research endeavor.

1. Experimental Research Design: Mastering Controlled Trials

Delve into the heart of experimentation with Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). By randomizing participants into experimental and control groups, RCTs meticulously assess the efficacy of interventions or treatments, establishing clear cause-and-effect relationships.

2. Quasi-Experimental Research Design: Bridging the Gap Ethically

When randomness isn’t feasible, embrace the pragmatic alternative of Non-equivalent Group Designs. These designs allow ethical comparison across multiple groups without random assignment, ensuring robust research conduct.

3. Observational Research Design: Capturing Real-world Dynamics

Capture snapshots of reality with Cross-Sectional Studies, unraveling intricate relationships and disparities between variables in a single moment. Embark on longitudinal journeys with Longitudinal Studies, tracking evolving trends and patterns over time.

4. Descriptive Research Design: Unveiling Insights Through Data

Plunge into the depths of data collection with Survey Research, extracting insights into attitudes, characteristics, and opinions. Engage in profound exploration through Case Studies, dissecting singular phenomena to unveil profound insights.

5. Correlational Research Design: Navigating Interrelationships

Traverse the realm of correlations with Correlational Studies, scrutinizing interrelationships between variables without inferring causality. Uncover insights into the dynamic web of connections shaping research landscapes.

6. Ex Post Facto Research Design: Retroactive Revelations

Explore existing conditions retrospectively with Retrospective Exploration, shedding light on potential causes where variable manipulation isn’t feasible. Uncover hidden insights through meticulous retrospective analysis.

7. Exploratory Research Design: Pioneering New Frontiers

Initiate your research odyssey with Pilot Studies, laying the groundwork for comprehensive investigations while refining research procedures. Blaze trails into uncharted territories and unearth groundbreaking discoveries.

8. Cohort Study: Chronicling Evolution

Embark on longitudinal expeditions with Cohort Studies, monitoring cohorts to elucidate the evolution of specific outcomes over time. Witness the unfolding narrative of change and transformation.

9. Action Research: Driving Practical Solutions

Collaboratively navigate challenges with Action Research, fostering improvements in educational or organizational settings. Drive meaningful change through actionable insights derived from collaborative endeavors.

10. Meta-Analysis: Synthesizing Knowledge

Combine perspectives gleaned from various studies through Meta-Analyses, providing a comprehensive panorama of research discoveries.

By honing in on the nuances of each research design and aligning your content with strategic SEO principles, you can ascend to the zenith of search engine rankings and establish your authority in the domain of research methodology.

Learn more: What is Research?

Research design methods refer to the systematic approaches and techniques used to plan, structure, and conduct a research study. The choice of research design method depends on the research questions, objectives, and the nature of the study. Here are some key research design methods commonly used in various fields:

1. Experimental Method

Controlled Experiments: In controlled experiments, researchers manipulate one or more independent variables and measure their effects on dependent variables while controlling for confounding factors.

2. Observational Method

Naturalistic Observation: Researchers observe and record behavior in its natural setting without intervening. This method is often used in psychology and anthropology.

Structured Observation: Observations are made using a predetermined set of criteria or a structured observation schedule.

3. Survey Method

Questionnaires: Researchers collect data by administering structured questionnaires to participants. This method is widely used for collecting quantitative research data.

Interviews: In interviews, researchers ask questions directly to participants, allowing for more in-depth responses. Interviews can take on structured, semi-structured, or unstructured formats.

4. Case Study Method

Single-Case Study: Focuses on a single individual or entity, providing an in-depth analysis of that case.

Multiple-Case Study: Involves the examination of multiple cases to identify patterns, commonalities, or differences.

5. Content Analysis

Researchers analyze textual, visual, or audio data to identify patterns, themes, and trends. This method is commonly used in media studies and social sciences.

6. Historical Research

Researchers examine historical documents, records, and artifacts to understand past events, trends, and contexts.

7. Action Research

Researchers work collaboratively with practitioners to address practical problems or implement interventions in real-world settings.

8. Ethnographic Research

Researchers immerse themselves in a particular cultural or social group to gain a deep understanding of their behaviors, beliefs, and practices.

9. Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Surveys

Cross-sectional surveys collect data from a sample of participants at a single point in time.

Longitudinal surveys collect data from the same participants over an extended period, allowing for the study of changes over time.

10. Meta-Analysis

Researchers conduct a quantitative synthesis of data from multiple studies to provide a comprehensive overview of research findings on a particular topic.

11. Mixed-Methods Research

Combines qualitative and quantitative research methods to provide a more holistic understanding of a research problem.

12. Grounded Theory

A qualitative research method that aims to develop theories or explanations grounded in the data collected during the research process.

13. Simulation and Modeling

Researchers use mathematical or computational models to simulate real-world phenomena and explore various scenarios.

14. Survey Experiments

Combines elements of surveys and experiments, allowing researchers to manipulate variables within a survey context.

15. Case-Control Studies and Cohort Studies

These epidemiological research methods are used to study the causes and risk factors associated with diseases and health outcomes.

16. Cross-Sequential Design

Combines elements of cross-sectional and longitudinal research to examine both age-related changes and cohort differences.

The selection of a specific research design method should align with the research objectives, the type of data needed, available resources, ethical considerations, and the overall research approach. Researchers often choose methods that best suit the nature of their study and research questions to ensure that they collect relevant and valid data.

Learn more: What is Research Objective?

Research designs can vary significantly depending on the research questions and objectives. Here are some examples of research designs across different disciplines:

- Experimental Design: A pharmaceutical company conducts a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test the efficacy of a new drug. Participants are randomly assigned to two groups: one receiving the new drug and the other a placebo. The company measures the health outcomes of both groups over a specific period.

- Observational Design: An ecologist observes the behavior of a particular bird species in its natural habitat to understand its feeding patterns, mating rituals, and migration habits.

- Survey Design: A market research firm conducts a survey to gather data on consumer preferences for a new product. They distribute a questionnaire to a representative sample of the target population and analyze the responses.

- Case Study Design: A psychologist conducts a case study on an individual with a rare psychological disorder to gain insights into the causes, symptoms, and potential treatments of the condition.

- Content Analysis: Researchers analyze a large dataset of social media posts to identify trends in public opinion and sentiment during a political election campaign.

- Historical Research: A historian examines primary sources such as letters, diaries, and official documents to reconstruct the events and circumstances leading up to a significant historical event.

- Action Research: A school teacher collaborates with colleagues to implement a new teaching method in their classrooms and assess its impact on student learning outcomes through continuous reflection and adjustment.

- Ethnographic Research: An anthropologist lives with and observes an indigenous community for an extended period to understand their culture, social structures, and daily lives.

- Cross-Sectional Survey: A public health agency conducts a cross-sectional survey to assess the prevalence of smoking among different age groups in a specific region during a particular year.

- Longitudinal Study: A developmental psychologist follows a group of children from infancy through adolescence to study their cognitive, emotional, and social development over time.

- Meta-Analysis: Researchers aggregate and analyze the results of multiple studies on the effectiveness of a specific type of therapy to provide a comprehensive overview of its outcomes.

- Mixed-Methods Research: A sociologist combines surveys and in-depth interviews to study the impact of a community development program on residents’ quality of life.

- Grounded Theory: A sociologist conducts interviews with homeless individuals to develop a theory explaining the factors that contribute to homelessness and the strategies they use to cope.

- Simulation and Modeling: Climate scientists use computer models to simulate the effects of various greenhouse gas emission scenarios on global temperatures and sea levels.

- Case-Control Study: Epidemiologists investigate a disease outbreak by comparing a group of individuals who contracted the disease (cases) with a group of individuals who did not (controls) to identify potential risk factors.

These examples demonstrate the diversity of research designs used in different fields to address a wide range of research questions and objectives. Researchers select the most appropriate design based on the specific context and goals of their study.

Learn more: What is Competitive Research?

Enhance Your Research

Collect feedback and conduct research with IdeaScale’s award-winning software

Elevate Research And Feedback With Your IdeaScale Community!

IdeaScale is an innovation management solution that inspires people to take action on their ideas. Your community’s ideas can change lives, your business and the world. Connect to the ideas that matter and start co-creating the future.

Copyright © 2024 IdeaScale

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

What is Research? – Purpose of Research

- By DiscoverPhDs

- September 10, 2020

The purpose of research is to enhance society by advancing knowledge through the development of scientific theories, concepts and ideas. A research purpose is met through forming hypotheses, collecting data, analysing results, forming conclusions, implementing findings into real-life applications and forming new research questions.

What is Research

Simply put, research is the process of discovering new knowledge. This knowledge can be either the development of new concepts or the advancement of existing knowledge and theories, leading to a new understanding that was not previously known.

As a more formal definition of research, the following has been extracted from the Code of Federal Regulations :

While research can be carried out by anyone and in any field, most research is usually done to broaden knowledge in the physical, biological, and social worlds. This can range from learning why certain materials behave the way they do, to asking why certain people are more resilient than others when faced with the same challenges.

The use of ‘systematic investigation’ in the formal definition represents how research is normally conducted – a hypothesis is formed, appropriate research methods are designed, data is collected and analysed, and research results are summarised into one or more ‘research conclusions’. These research conclusions are then shared with the rest of the scientific community to add to the existing knowledge and serve as evidence to form additional questions that can be investigated. It is this cyclical process that enables scientific research to make continuous progress over the years; the true purpose of research.

What is the Purpose of Research

From weather forecasts to the discovery of antibiotics, researchers are constantly trying to find new ways to understand the world and how things work – with the ultimate goal of improving our lives.

The purpose of research is therefore to find out what is known, what is not and what we can develop further. In this way, scientists can develop new theories, ideas and products that shape our society and our everyday lives.

Although research can take many forms, there are three main purposes of research:

- Exploratory: Exploratory research is the first research to be conducted around a problem that has not yet been clearly defined. Exploration research therefore aims to gain a better understanding of the exact nature of the problem and not to provide a conclusive answer to the problem itself. This enables us to conduct more in-depth research later on.

- Descriptive: Descriptive research expands knowledge of a research problem or phenomenon by describing it according to its characteristics and population. Descriptive research focuses on the ‘how’ and ‘what’, but not on the ‘why’.

- Explanatory: Explanatory research, also referred to as casual research, is conducted to determine how variables interact, i.e. to identify cause-and-effect relationships. Explanatory research deals with the ‘why’ of research questions and is therefore often based on experiments.

Characteristics of Research

There are 8 core characteristics that all research projects should have. These are:

- Empirical – based on proven scientific methods derived from real-life observations and experiments.

- Logical – follows sequential procedures based on valid principles.

- Cyclic – research begins with a question and ends with a question, i.e. research should lead to a new line of questioning.

- Controlled – vigorous measures put into place to keep all variables constant, except those under investigation.

- Hypothesis-based – the research design generates data that sufficiently meets the research objectives and can prove or disprove the hypothesis. It makes the research study repeatable and gives credibility to the results.

- Analytical – data is generated, recorded and analysed using proven techniques to ensure high accuracy and repeatability while minimising potential errors and anomalies.

- Objective – sound judgement is used by the researcher to ensure that the research findings are valid.

- Statistical treatment – statistical treatment is used to transform the available data into something more meaningful from which knowledge can be gained.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Types of Research

Research can be divided into two main types: basic research (also known as pure research) and applied research.

Basic Research

Basic research, also known as pure research, is an original investigation into the reasons behind a process, phenomenon or particular event. It focuses on generating knowledge around existing basic principles.

Basic research is generally considered ‘non-commercial research’ because it does not focus on solving practical problems, and has no immediate benefit or ways it can be applied.

While basic research may not have direct applications, it usually provides new insights that can later be used in applied research.

Applied Research

Applied research investigates well-known theories and principles in order to enhance knowledge around a practical aim. Because of this, applied research focuses on solving real-life problems by deriving knowledge which has an immediate application.

Methods of Research

Research methods for data collection fall into one of two categories: inductive methods or deductive methods.

Inductive research methods focus on the analysis of an observation and are usually associated with qualitative research. Deductive research methods focus on the verification of an observation and are typically associated with quantitative research.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a method that enables non-numerical data collection through open-ended methods such as interviews, case studies and focus groups .

It enables researchers to collect data on personal experiences, feelings or behaviours, as well as the reasons behind them. Because of this, qualitative research is often used in fields such as social science, psychology and philosophy and other areas where it is useful to know the connection between what has occurred and why it has occurred.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is a method that collects and analyses numerical data through statistical analysis.

It allows us to quantify variables, uncover relationships, and make generalisations across a larger population. As a result, quantitative research is often used in the natural and physical sciences such as engineering, biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, finance, and medical research, etc.

What does Research Involve?

Research often follows a systematic approach known as a Scientific Method, which is carried out using an hourglass model.

A research project first starts with a problem statement, or rather, the research purpose for engaging in the study. This can take the form of the ‘ scope of the study ’ or ‘ aims and objectives ’ of your research topic.

Subsequently, a literature review is carried out and a hypothesis is formed. The researcher then creates a research methodology and collects the data.

The data is then analysed using various statistical methods and the null hypothesis is either accepted or rejected.

In both cases, the study and its conclusion are officially written up as a report or research paper, and the researcher may also recommend lines of further questioning. The report or research paper is then shared with the wider research community, and the cycle begins all over again.

Although these steps outline the overall research process, keep in mind that research projects are highly dynamic and are therefore considered an iterative process with continued refinements and not a series of fixed stages.

Learn more about using cloud storage effectively, video conferencing calling, good note-taking solutions and online calendar and task management options.

Need to write a list of abbreviations for a thesis or dissertation? Read our post to find out where they go, what to include and how to format them.

Multistage sampling is a more complex form of cluster sampling for obtaining sample populations. Learn their pros and cons and how to undertake them.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

A concept paper is a short document written by a researcher before starting their research project, explaining what the study is about, why it is needed and the methods that will be used.

Choosing a good PhD supervisor will be paramount to your success as a PhD student, but what qualities should you be looking for? Read our post to find out.

Sammy is a second year PhD student at Cardiff Metropolitan University researching how secondary school teachers can meet the demands of the Digital Competence Framework.

Julia is entering the third year of a combined master’s and PhD program at Stanford University. Her research explores how to give robots the sense of touch to make them more useful for tasks such as dexterous manipulation.

Join Thousands of Students

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.