Should drugs be legalized? Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Incensed by the steadily growing number of deaths, crime and corruption created by illicit drug trade and use in the recent years, a number of persons drawn from both the government and the private sector have been calling for the legalization of drugs to curb the problems associated with the abuse and trade in drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana.

They argue that such a move would do more than any single act or policy in removing the biggest of society’s social and political problems. However, these calls are unfortunate and could throw an already grave problem completely out of hand. If examined carefully, it becomes clear that legalization of drugs would not bring a solution to any of the problems associated with drug abuse.

Proponents of the move to legalize argue that drug use should be an individual’s choice and the government should not control it in any way. This argument has two key shortcomings. First, we cannot just do anything we want with our bodies, just the same way a person cannot walk down the street naked, or say anything we want anywhere. The government has to step in at some point. Drug use is obviously more harmful than these two inconceivable acts.

Secondly, when people opt to do “whatever they want” with their bodies, such as drug use, it not only affects them, but also those around them (DEA, 2003). To put it practically, a driver who is ‘high’ on drugs puts the life of others on the road in danger. Such a person cannot operate machinery or even tend for their children and families as required of them. Therefore, the argument that every one has a right to do whatever they want with their bodies is simply misplaced.

Proponents of the debate to legalize drugs argue that this move will discourage drug use, citing a report by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction that the Dutch are the lowest users of cannabis. They attribute this to Netherlands’ soft stance on drugs which permits cannabis sale at coffee shops and the possession of not more than 5 grams of cannabis. However, this is a shallow argument.

The Dutch government’s soft policy on marijuana use has created a much bigger problem: the differentiation of markets between hard drug users and dealers (heroin, cocaine and amphetamines) and soft drug users (marijuana) (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, 2001).

Consequently, the number of marijuana users has fallen as most people have resorted to hard drugs, making the country a criminal center for illegal artificial drug manufacture, especially ecstasy, in addition to becoming a home for the production and export of marijuana breeds that have been reported to be ten times higher than normal (DEA, 2003). Besides, a 2001 study in Australia that found that prohibition deters drug abuse (NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, 2001).

Drug laws are very important in keeping these harmful substances out of reach of children. As long as drugs laws are put in place, the prices will continue to be higher, beyond the reach of most underage persons and even youths. The link between pricing and rate of drug use among young adults is evident in alcohol and drug use.

Studies show that high prices of alcohol and cigarettes result into decline in use of the substances (DEA, 2003). In addition, legalization of drugs would encourage sellers to recruit children sellers who can easily convince their peers to use the substances, hence increasing drug penetration into society. As long as drugs are not legalized, such a move is very unlikely, or can occur only in small scales.

DEA (U.S. Department of Justice: Drug Enforcement Administration). (2003 ). Speaking out against Drug Legalization . Web.

NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. (2001). Does prohibition deter cannabis use? Web.

- Minor and Major Arguments on Legalization of Marijuana

- Leadership and Power in Political Theories

- Marijuana and Its Economic Value in the USA

- Cannabis Smoking in Canada

- How New York Would Benefit From Legalized Medical Marijuana

- Problems with Bureaucracy

- Contemporary Examples of Fascist Thoughts

- Revolution's Positive Effects

- Crime Prevention Programs in the State of California

- Fundamental Right to Live: Abolish the Death Penalty

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 12). Should drugs be legalized? https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-drugs-be-legalized/

"Should drugs be legalized?" IvyPanda , 12 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/should-drugs-be-legalized/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Should drugs be legalized'. 12 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Should drugs be legalized?" October 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-drugs-be-legalized/.

1. IvyPanda . "Should drugs be legalized?" October 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-drugs-be-legalized/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Should drugs be legalized?" October 12, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/should-drugs-be-legalized/.

You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

Should drugs be legalized? Legalization pros and cons

Source: Composite by G_marius based on Chuck Grimmett's image

Should drugs be legalized? Why? Is it time to lift the prohibition on recreational drugs such as marijuana and cocaine? Can we stop drug trafficking? if so what would be the best way to reduce consumption?

Public health problem

Drugs continue to be one of the greatest problems for public health . Although the consumption of some substances has declined over time, new drugs have entered the market and become popular. In the USA, after the crack epidemic, in the 80s and early 90s, and the surge of methamphetamine, in the 90s and early 21st century, there is currently a prescription opioid crisis . The number of casualties from these opioids, largely bought in pharmacies, has overtaken the combined deaths from cocaine and heroine overdose. There are million of addicts to these substances which are usually prescribed by a doctor. This is a relevant twist to the problem of drugs because it shows that legalization or criminalization may not always bring the desire solution to the problem of drug consumption. On the other hand there is also evidence of success in reducing drug abuse through legal reform. This is the case of Portuguese decriminalization of drug use, which has show a dramatic decrease in drug related crime, overdoses and HIV infections.

History of prohibition of drugs

There are legal recreational drugs , such as alcohol and tobacco , and other recreational drugs which are prohibited. The history of prohibition of drugs is long. Islamic Sharia law, which dates back to the 7th century, banned some intoxicating substances, including alcohol. Opium consumption was later prohibited in China and Thailand. The Pharmacy Act 1868 in the United Kingdom was the first modern law in Europe regulating drug use. This law prohibited the distribution of poison and drugs, and in particular opium and derivates. Gradually other Western countries introduced laws to limit the use of opiates. For instance in San Francisco smoking opium was banned in 1875 and in Australia opium sale was prohibited in 1905 . In the early 20th century, several countries such as Canada, Finland, Norway, the US and Russia, introduced alcohol prohibitions . These alcohol prohibitions were unsucessful and lifted later on. Drug prohibitions were strengthened around the world from the 1960s onward. The US was one of the main proponents of a strong stance against drugs, in particular since Richad Nixon declared the "War on Drugs ." The "War on Drugs" did not produced the results expected. The demand for drugs grew as well as the number of addicts. Since production and distribution was illegal, criminals took over its supply. Handing control of the drug trade to organized criminals has had disastrous consequences across the globe. T oday, drug laws diverge widely across countries. Some countries have softer regulation and devote less resources to control drug trafficking, while in other countries the criminalization of drugs can entail very dire sentences. Thus while in some countries recreational drug use has been decriminalized, in others drug traficking is punished with life or death sentences.

Should drugs be legalized?

In many Western countries drug policies are considered ineffective and decriminalization of drugs has become a trend. Many experts have provided evidence on why drugs should be legal . One reason for legalization of recreational drug use is that the majority of adicts are not criminals and should not be treated as such but helped in other ways. The criminalization of drug users contributes to generating divides in our societies. The "War on Drugs" held by the governments of countries such as USA , Mexico, Colombia, and Indonesia, created much harm to society. Drug related crimes have not always decline after a more intolerant government stance on drugs. Prohibition and crime are often seen as correlated.

T here is also evidence of successful partial decriminalization in Canada, Switzerland, Portugal and Uruguay. Other countries such as Ireland seem to be following a similar path and are planning to decriminalize some recreational drugs soon. Moreover, The United Nations had a special session on drugs on 2016r, UNGASS 2016 , following the request of the presidents of Colombia, Mexico and Guatemala. The goal of this session was to analyse the effects of the war on drugs. explore new options and establish a new paradigm in international drug policy in order to prevent the flow of resources to organized crime organizations. This meeting was seen as an opportunity, and even a call, for far-reaching drug law reforms. However, the final outcome failed to change the status quo and to trigger any ambitious reform.

However, not everyone is convinced about the need of decriminalization of recreational drugs. Some analysts point to several reasons why drugs should not be legalized and t he media have played an important role in shaping the public discourse and, indirectly, policy-making against legalization. For instance, t he portrayal of of the issue in British media, tabloids in particular, has reinforced harmful, dehumanising stereotypes of drug addicts as criminals. At the moment the UK government’s response is to keep on making illegal new recreational drugs. For instance, Psychoactive Substances Bill aims at criminalizing legal highs . Those supporting the bill argue that criminalization makes more difficult for young people to have access to these drugs and could reduce the number of people who get addicted.

List of recreational drugs

This is the list of recreational drugs (in alphabetic order) which could be subject to decriminalization in the future:

- Amfetamines (speed, whizz, dexies, sulph)

- Amyl nitrates (poppers, amys, kix, TNT)

- Cannabis (marijuana, hash, hashish, weed)

- Cocaine (crack, freebase, toot)

- Ecstasy (crystal, MDMA, E)

- Heroin (H, smack, skag, brown)

- Ketamine (K, special K, green)

- LSD (acid, paper mushrooms, tripper)

- Magic mushrooms (mushies, magics)

- Mephedrone (meow meow, drone, m cat)

- Methamfetamines (yaba, meth, crank, glass)

- Painkillers, sedatives and tranquilizers (chill pills, blues, bricks)

Pros and cons of legalization of drugs

These are some of the most commonly argued pros of legalization :

- Government would see the revenues boosted due to the money collected from taxing drugs.

- Health and safety controls on these substances could be implemented, making recreational drugs less dangerous.

- Facilitate access for medicinal use. For instance cannabis is effective treating a range of conditions. Other recreational drugs could be used in similar ways.

- Personal freedom. People would have the capacity to decide whether they experiment with drugs without having to be considered criminals or having to deal with illegal dealers.

- Criminal gangs could run out of business and gun violence would be reduced.

- Police resources could be used in other areas and help increase security.

- The experience of decriminalization of drugs in some countries such as Portugal and Uruguay, has led to a decrease in drug related problems.

Cons of decriminalizing drug production, distribution and use:

- New users for drugs. As in the case of legal recreational drugs, decriminalization does not imply reduction in consumption. If these substances are legal, trying them could become "more normal" than nowadays.

- Children and teenagers could more easily have access to drugs.

- Drug trafficking would remain a problem. If governments heavily tax drugs, it is likely that some criminal networks continue to produce and smuggle them providing a cheaper price for consumers.

- The first few countries which decide to legalize drugs could have problems of drug tourism.

- The rate of people driving and having accidents due drug intoxication could increase.

- Even with safety controls, drugs would continue to be a great public health problem and cause a range of diseases (damamge to the brain and lungs, heart diseases, mental health conditions).

- People may still become addicts and die from legalized drugs, as in America's opioid crisis.

What do think, should recreational drugs be legalized or decriminalized? Which of them? Is legalising drugs being soft on crime? Is the prohibition on drugs making the work of the police more difficult and diverting resources away from other more important issues? Join the discussion and share arguments and resources on the forum below .

Watch these videos on decriminalization of drugs

Vote to see result and collect 1 XP. Your vote is anonymous. If you change your mind, you can change your vote simply by clicking on another option.

Voting results

New to netivist?

Join with confidence, netivist is completely advertisement free. You will not receive any promotional materials from third parties.

Or sign in with your favourite Social Network:

Join the debate

In order to join the debate you must be logged in.

Already have an account on netivist? Just login . New to netivist? Create your account for free .

Report Abuse and Offensive language

Was there any kind of offensive or inappropriate language used in this comment.

If you feel this user's conduct is unappropriate, please report this comment and our moderaters will review its content and deal with this matter as soon as possible.

NOTE: Your account might be penalized should we not find any wrongdoing by this user. Only use this feature if you are certain this user has infringed netivist's Terms of Service .

Our moderators will now review this comment and act accordingly. If it contains abusive or inappropriate language its author will be penalized.

Posting Comment

Your comment is being posted. This might take a few seconds, please wait.

Error Posting Comment

error.

We are having trouble saving your comment. Please try again .

Most Voted Debates

| Rank | |

|---|---|

Start a Debate

Would you like to create a debate and share it with the netivist community? We will help you do it!

Found a technical issue?

Are you experiencing any technical problem with netivist? Please let us know!

Help netivist

Help netivist continue running free!

Please consider making a small donation today. This will allow us to keep netivist alive and available to a wide audience and to keep on introducing new debates and features to improve your experience.

- What is netivist?

- Entertainment

- Top Debates

- Top Campaigns

- Provide Feedback

Follow us on social media:

Share by Email

There was an error...

Email successfully sent to:

Join with confidence, netivist is completely advertisement free You will not recive any promotional materials from third parties

Join netivist

Already have a netivist account?

If you already created your netivist account, please log in using the button below.

If you are new to netivist, please create your account for free and start collecting your netivist points!

You just leveled up!

Congrats you just reached a new level on Netivist. Keep up the good work.

Together we can make a difference

Follow us and don't miss out on the latest debates!

Why all drugs should be legal. (Yes, even heroin.)

Prohibition has huge costs

- Newsletter sign up Newsletter

We've come a long way since Reefer Madness . Over the past two decades, 16 states have de-criminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana, and 22 have legalized it for medical purposes. In November 2012, Colorado and Washington went further, legalizing marijuana under state law for recreational purposes. Public attitudes toward marijuana have also changed; in a November 2013 Gallup Poll , 58 percent of Americans supported marijuana legalization.

Yet amidst these cultural and political shifts, American attitudes and U.S. policy toward other drugs have remained static. No state has decriminalized, medicalized, or legalized cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamine. And a recent poll suggests only about 10 percent of Americans favor legalization of cocaine or heroin. Many who advocate marijuana legalization draw a sharp distinction between marijuana and "hard drugs."

That's understandable: Different drugs do carry different risks, and the potential for serious harm from marijuana is less than for cocaine, heroin, or methamphetamine. Marijuana, for example, appears incapable of causing a lethal overdose, but cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine can kill if taken in excess or under the wrong circumstances.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But if the goal is to minimize harm — to people here and abroad — the right policy is to legalize all drugs, not just marijuana.

In fact, many legal goods cause serious harm, including death. In recent years, about 40 people per year have died from skiing or snowboarding accidents ; almost 800 from bicycle accidents; several thousand from drowning in swimming pools ; more than 20,000 per year from pharmaceuticals ; more than 30,000 annually from auto accidents ; and at least 38,000 from excessive alcohol use .

Few people want to ban these goods, mainly because while harmful when misused, they provide substantial benefit to most people in most circumstances.

The same condition holds for hard drugs. Media accounts focus on users who experience bad outcomes, since these are dramatic or newsworthy. Yet millions risk arrest, elevated prices, impurities, and the vagaries of black markets to purchase these goods, suggesting people do derive benefits from use.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

That means even if prohibition could eliminate drug use, at no cost, it would probably do more harm than good. Numerous moderate and responsible drug users would be worse off, while only a few abusive users would be better off.

And prohibition does, in fact, have huge costs, regardless of how harmful drugs might be.

First, a few Economics 101 basics: Prohibiting a good does not eliminate the market for that good. Prohibition may shrink the market, by raising costs and therefore price, but even under strongly enforced prohibitions, a substantial black market emerges in which production and use continue. And black markets generate numerous unwanted side effects.

Black markets increase violence because buyers and sellers can't resolve disputes with courts, lawyers, or arbitration, so they turn to guns instead. Black markets generate corruption, too, since participants have a greater incentive to bribe police, prosecutors, judges, and prison guards. They also inhibit quality control, which causes more accidental poisonings and overdoses.

What's more, prohibition creates health risks that wouldn't exist in a legal market. Because prohibition raises heroin prices, users have a greater incentive to inject because this offers a bigger bang for the buck. Plus, prohibition generates restrictions on the sale of clean needles (because this might "send the wrong message"). Many users therefore share contaminated needles, which transmit HIV, Hepatitis C, and other blood-borne diseases. In 2010, 8 percent of new HIV cases in the United States were attributed to IV drug use.

Prohibition enforcement also encourages infringements on civil liberties, such as no-knock warrants (which have killed dozens of innocent bystanders) and racial profiling (which generates much higher arrest rates for blacks than whites despite similar drug use rates). It also costs a lot to enforce prohibition, and it means we can't collect taxes on drugs; my estimates suggest U.S. governments could improve their budgets by at least $85 billion annually by legalizing — and taxing — all drugs. U.S. insistence that source countries outlaw drugs means increased violence and corruption there as well (think Columbia, Mexico, or Afghanistan).

The bottom line: Even if hard drugs carry greater health risks than marijuana, rationally, we can't ban them without comparing the harm from prohibition against the harms from drugs themselves. In a society that legalizes drugs, users face only the negatives of use. Under prohibition, they also risk arrest, fines, loss of professional licenses, and more. So prohibition unambiguously harms those who use despite prohibition.

It's also critical to analyze whether prohibition actually reduces drug use; if the effects are small, then prohibition is virtually all cost and no benefit.

On that question, available evidence is far from ideal, but none of it suggests that prohibition has a substantial impact on drug use. States and countries that decriminalize or medicalize see little or no increase in drug use. And differences in enforcement across time or place bear little correlation with uses. This evidence does not bear directly on what would occur under full legalization, since that might allow advertising and more efficient, large-scale production. But data on cirrhosis from repeal of U.S. Alcohol Prohibition suggest only a modest increase in alcohol consumption.

To the extent prohibition does reduce use drug use, the effect is likely smaller for hard drugs than for marijuana. That's because the demands for cocaine and heroin appear less responsive to price. From this perspective, the case is even stronger for legalizing cocaine or heroin than marijuana; for hard drugs, prohibition mainly raises the price, which increases the resources devoted to the black market while having minimal impact on use.

But perhaps the best reason to legalize hard drugs is that people who wish to consume them have the same liberty to determine their own well-being as those who consume alcohol, or marijuana, or anything else. In a free society, the presumption must always be that individuals, not government, get to decide what is in their own best interest.

Sign up to get The Weekly Wonk, New America's digital magazine, delivered to your inbox each Thursday here .

More from The Weekly Wonk ...

- Putin's Machiavellian moment

- What's different this time

- College and the common core

The Week Recommends Traveling in September means more room to explore

By Catherine Garcia, The Week US Published 4 September 24

In depth Schools have long been desegregated, but historically Black colleges and universities are still filling a need in the United States

By Theara Coleman, The Week US Published 4 September 24

Speed Read Linda Sun, the former aide to Kathy Hochul, has been accused of spying for the Chinese government

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published 4 September 24

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Advertise With Us

The Week is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

Drug Legalization?: Time for a real debate

Subscribe to governance weekly, paul stares ps paul stares.

March 1, 1996

- 11 min read

Whether Bill Clinton “inhaled” when trying marijuana as a college student was about the closest the last presidential campaign came to addressing the drug issue. The present one, however, could be very different. For the fourth straight year, a federally supported nationwide survey of American secondary school students by the University of Michigan has indicated increased drug use. After a decade or more in which drug use had been falling, the Republicans will assuredly blame the bad news on President Clinton and assail him for failing to carry on the Bush and Reagan administrations’ high-profile stand against drugs. How big this issue becomes is less certain, but if the worrisome trend in drug use among teens continues, public debate about how best to respond to the drug problem will clearly not end with the election. Indeed, concern is already mounting that the large wave of teenagers—the group most at risk of taking drugs—that will crest around the turn of the century will be accompanied by a new surge in drug use.

As in the past, some observers will doubtless see the solution in much tougher penalties to deter both suppliers and consumers of illicit psychoactive substances. Others will argue that the answer lies not in more law enforcement and stiffer sanctions, but in less. Specifically, they will maintain that the edifice of domestic laws and international conventions that collectively prohibit the production, sale, and consumption of a large array of drugs for anything other than medical or scientific purposes has proven physically harmful, socially divisive, prohibitively expensive, and ultimately counterproductive in generating the very incentives that perpetuate a violent black market for illicit drugs. They will conclude, moreover, that the only logical step for the United States to take is to “legalize” drugs—in essence repeal and disband the current drug laws and enforcement mechanisms in much the same way America abandoned its brief experiment with alcohol prohibition in the 1920s.

Although the legalization alternative typically surfaces when the public’s anxiety about drugs and despair over existing policies are at their highest, it never seems to slip off the media radar screen for long. Periodic incidents—such as the heroin-induced death of a young, affluent New York City couple in 1995 or the 1993 remark by then Surgeon General Jocelyn Elders that legalization might be beneficial and should be studied—ensure this. The prominence of many of those who have at various times made the case for legalization—such as William F. Buckley, Jr., Milton Friedman, and George Shultz—also helps. But each time the issue of legalization arises, the same arguments for and against are dusted off and trotted out, leaving us with no clearer understanding of what it might entail and what the effect might be.

As will become clear, drug legalization is not a public policy option that lends itself to simplistic or superficial debate. It requires dissection and scrutiny of an order that has been remarkably absent despite the attention it perennially receives. Beyond discussion of some very generally defined proposals, there has been no detailed assessment of the operational meaning of legalization. There is not even a commonly accepted lexicon of terms to allow an intellectually rigorous exchange to take place. Legalization, as a consequence, has come to mean different things to different people. Some, for example, use legalization interchangeably with “decriminalization,” which usually refers to removing criminal sanctions for possessing small quantities of drugs for personal use. Others equate legalization, at least implicitly, with complete deregulation, failing in the process to acknowledge the extent to which currently legally available drugs are subject to stringent controls.

Unfortunately, the U.S. government—including the Clinton administration—has done little to improve the debate. Although it has consistently rejected any retreat from prohibition, its stance has evidently not been based on in- depth investigation of the potential costs and benefits. The belief that legalization would lead to an instant and dramatic increase in drug use is considered to be so self-evident as to warrant no further study. But if this is indeed the likely conclusion of any study, what is there to fear aside from criticism that relatively small amounts of taxpayer money had been wasted in demonstrating what everyone had believed at the outset? Wouldn’t such an outcome in any case help justify the continuation of existing policies and convincingly silence those—admittedly never more than a small minority—calling for legalization?

A real debate that acknowledges the unavoidable complexities and uncertainties surrounding the notion of drug legalization is long overdue. Not only would it dissuade people from making the kinds of casual if not flippant assertions—both for and against—that have permeated previous debates about legalization, but it could also stimulate a larger and equally critical assessment of current U.S. drug control programs and priorities.

First Ask the Right Questions

Many arguments appear to make legalization a compelling alternative to today’s prohibitionist policies. Besides undermining the black-market incentives to produce and sell drugs, legalization could remove or at least significantly reduce the very problems that cause the greatest public concern: the crime, corruption, and violence that attend the operation of illicit drug markets. It would presumably also diminish the damage caused by the absence of quality controls on illicit drugs and slow the spread of infectious diseases due to needle sharing and other unhygienic practices. Furthermore, governments could abandon the costly and largely futile effort to suppress the supply of illicit drugs and jail drug offenders, spending the money thus saved to educate people not to take drugs and treat those who become addicted.

However, what is typically portrayed as a fairly straightforward process of lifting prohibitionist controls to reap these putative benefits would in reality entail addressing an extremely complex set of regulatory issues. As with most if not all privately and publicly provided goods, the key regulatory questions concern the nature of the legally available drugs, the terms of their supply, and the terms of their consumption (see page 21).

What becomes immediately apparent from even a casual review of these questions—and the list presented here is by no means exhaustive—is that there is an enormous range of regulatory permutations for each drug. Until all the principal alternatives are clearly laid out in reasonable detail, however, the potential costs and benefits of each cannot begin to be responsibly assessed. This fundamental point can be illustrated with respect to the two central questions most likely to sway public opinion. What would happen to drug consumption under more permissive regulatory regimes? And what would happen to crime?

Relaxing the availability of psychoactive substances not already commercially available, opponents typically argue, would lead to an immediate and substantial rise in consumption. To support their claim, they point to the prevalence of opium, heroin, and cocaine addiction in various countries before international controls took effect, the rise in alcohol consumption after the Volstead Act was repealed in the United States, and studies showing higher rates of abuse among medical professionals with greater access to prescription drugs. Without explaining the basis of their calculations, some have predicted dramatic increases in the number of people taking drugs and becoming addicted. These increases would translate into considerable direct and indirect costs to society, including higher public health spending as a result of drug overdoses, fetal deformities, and other drug-related misadventures such as auto accidents; loss of productivity due to worker absenteeism and on-the-job accidents; and more drug-induced violence, child abuse, and other crimes, to say nothing about educational impairment.

Advocates of legalization concede that consumption would probably rise, but counter that it is not axiomatic that the increase would be very large or last very long, especially if legalization were paired with appropriate public education programs. They too cite historical evidence to bolster their claims, noting that consumption of opium, heroin, and cocaine had already begun falling before prohibition took effect, that alcohol consumption did not rise suddenly after prohibition was lifted, and that decriminalization of cannabis use in 11 U.S. states in the 1970s did not precipitate a dramatic rise in its consumption. Some also point to the legal sale of cannabis products through regulated outlets in the Netherlands, which also does not seem to have significantly boosted use by Dutch nationals. Public opinion polls showing that most Americans would not rush off to try hitherto forbidden drugs that suddenly became available are likewise used to buttress the pro-legalization case.

Neither side’s arguments are particularly reassuring. The historical evidence is ambiguous at best, even assuming that the experience of one era is relevant to another. Extrapolating the results of policy steps in one country to another with different sociocultural values runs into the same problem. Similarly, within the United States the effect of decriminalization at the state level must be viewed within the general context of continued federal prohibition. And opinion polls are known to be unreliable.

More to the point, until the nature of the putative regulatory regime is specified, such discussions are futile. It would be surprising, for example, if consumption of the legalized drugs did not increase if they were to become commercially available the way that alcohol and tobacco products are today, complete with sophisticated packaging, marketing, and advertising. But more restrictive regimes might see quite different outcomes. In any case, the risk of higher drug consumption might be acceptable if legalization could reduce dramatically if not remove entirely the crime associated with the black market for illicit drugs while also making some forms of drug use safer. Here again, there are disputed claims.

Opponents of more permissive regimes doubt that black market activity and its associated problems would disappear or even fall very much. But, as before, addressing this question requires knowing the specifics of the regulatory regime, especially the terms of supply. If drugs are sold openly on a commercial basis and prices are close to production and distribution costs, opportunities for illicit undercutting would appear to be rather small. Under a more restrictive regime, such as government-controlled outlets or medical prescription schemes, illicit sources of supply would be more likely to remain or evolve to satisfy the legally unfulfilled demand. In short, the desire to control access to stem consumption has to be balanced against the black market opportunities that would arise. Schemes that risk a continuing black market require more questions—about the new black markets operation over time, whether it is likely to be more benign than existing ones, and more broadly whether the trade-off with other benefits still makes the effort worthwhile.

The most obvious case is regulating access to drugs by adolescents and young adults. Under any regime, it is hard to imagine that drugs that are now prohibited would become more readily available than alcohol and tobacco are today. Would a black market in drugs for teenagers emerge, or would the regulatory regime be as leaky as the present one for alcohol and tobacco? A “yes” answer to either question would lessen the attractiveness of legalization.

What about the International Repercussions?

Not surprisingly, the wider international ramifications of drug legalization have also gone largely unremarked. Here too a long set of questions remains to be addressed. Given the longstanding U.S. role as the principal sponsor of international drug control measures, how would a decision to move toward legalizing drugs affect other countries? What would become of the extensive regime of multilateral conventions and bilateral agreements? Would every nation have to conform to a new set of rules? If not, what would happen? Would more permissive countries be suddenly swamped by drugs and drug consumers, or would traffickers focus on the countries where tighter restrictions kept profits higher? This is not an abstract question. The Netherlands’ liberal drug policy has attracted an influx of “drug tourists” from neighboring countries, as did the city of Zurich’s following the now abandoned experiment allowing an open drug market to operate in what became known as “Needle Park.” And while it is conceivable that affluent countries could soften the worst consequences of drug legalization through extensive public prevention and drug treatment programs, what about poorer countries?

Finally, what would happen to the principal suppliers of illicit drugs if restrictions on the commercial sale of these drugs were lifted in some or all of the main markets? Would the trafficking organizations adapt and become legal businesses or turn to other illicit enterprises? What would happen to the source countries? Would they benefit or would new producers and manufacturers suddenly spring up elsewhere? Such questions have not even been posed in a systematic way, let alone seriously studied.

Irreducible Uncertainties

Although greater precision in defining more permissive regulatory regimes is critical to evaluating their potential costs and benefits, it will not resolve the uncertainties that exist. Only implementation will do that. Because small-scale experimentation (assuming a particular locality’s consent to be a guinea pig) would inevitably invite complaints that the results were biased or inconclusive, implementation would presumably have to be widespread, even global, in nature.

Yet jettisoning nearly a century of prohibition when the putative benefits remain so uncertain and the potential costs are so high would require a herculean leap of faith. Only an extremely severe and widespread deterioration of the current drug situation, nationally and internationally—is likely to produce the consensus—again, nationally and internationally that could impel such a leap. Even then the legislative challenge would be stupendous. The debate over how to set the conditions for controlling access to each of a dozen popular drugs could consume the legislatures of the major industrial countries for years.

None of this should deter further analysis of drug legalization. In particular, a rigorous assessment of a range of hypothetical regulatory regimes according to a common set of variables would clarify their potential costs, benefits, and trade- offs. Besides instilling much-needed rigor into any further discussion of the legalization alternative, such analysis could encourage the same level of scrutiny of current drug control programs and policies. With the situation apparently deteriorating in the United States as well as abroad, there is no better time for a fundamental reassessment of whether our existing responses to this problem are sufficient to meet the likely challenges ahead.

Governance Studies

David R. Holtgrave, Regina LaBelle, Vanda Felbab-Brown

September 3, 2024

Nicole Gastala, Harold Pollack, Vanda Felbab-Brown

August 27, 2024

Stuart M. Butler

August 23, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

Should the United States Decriminalize the Possession of Drugs?

Several states have voted to reform their drug laws in response to the opioid epidemic and as a way to address high rates of drug-related incarceration. What do you think of this, and other, solutions?

By Nicole Daniels and Natalie Proulx

Students in U.S. high schools can get free digital access to The New York Times until Sept. 1, 2021.

Attitudes around drugs have changed considerably over the past few decades. Voters’ approval of drug-related initiatives in several states in the Nov. 3 election made that clear:

New Jersey, South Dakota, Montana and Arizona joined 11 other states that had already legalized recreational marijuana. Mississippi and South Dakota made medical marijuana legal, bringing the total to 35. The citizens of Washington, D.C., voted to decriminalize psilocybin, the organic compound active in psychedelic mushrooms. Oregon voters approved two drug-related initiatives. One decriminalized possession of small amounts of illegal drugs including heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines. (It did not make it legal to sell the drugs.) Another measure authorized the creation of a state program to license providers of psilocybin.

What is your reaction to these measures? Do you think more states — or even the entire country — should decriminalize marijuana? What about other drugs?

In “ This Election, a Divided America Stands United on One Topic ,” Jonah Engel Bromwich writes about the growing support to decriminalize drugs in the United States:

Election night represented a significant victory for three forces pushing for drug reform for different but interlocking reasons. There is the increasingly powerful cannabis industry. There are state governments struggling with budget shortfalls, hungry to fill coffers in the midst of a pandemic. And then there are the reform advocates, who for decades have been saying that imprisonment, federal mandatory minimum sentences and prohibitive cash bail for drug charges ruin lives and communities, particularly those of Black Americans. Decriminalization is popular, in part, because Americans believe that too many people are in jails and prisons, and also because Americans personally affected by the country’s continuing opioid crisis have been persuaded to see drugs as a public health issue.

Then, Mr. Bromwich explores the history of the “war on drugs”:

President Nixon started the war on drugs but it grew increasingly draconian during the Reagan administration. Nancy Reagan’s top priority was the antidrug campaign, which she pushed aggressively as her husband signed a series of punitive measures into law — measures shaped in part by Joseph R. Biden Jr., then a senator. “We want you to help us create an outspoken intolerance for drug use,” Mrs. Reagan said in 1986. “For the sake of our children, I implore each of you to be unyielding and inflexible in your opposition to drugs.” America’s airwaves were flooded with antidrug initiatives. An ad campaign that starred a man frying an egg and claiming “this is your brain on drugs” was introduced in 1987 and aired incessantly. Numerous animal mascots took up the cause of warning children about drugs and safety, including Daren the Lion, who educated children on drugs and bullying, and McGruff the Crime Dog, who taught children to open their hearts and minds to authority figures. In 1986 Congress passed a law mandating severe prison sentences for users of crack, who were disproportionately Black . In 1989, with prison rates rising, 64 percent of Americans surveyed said that drug abuse was the most serious problem facing the United States. The focus on crack meant that when pot returned to the headlines in the 1990s, it received comparatively cozy publicity . In 1996, California voters passed a measure allowing for the use of medical marijuana. Two years later, medical marijuana initiatives were approved by voters in four more states.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

- The Legalization of Drugs: For & Against

The Legalization of Drugs: For & Against

Douglas Husak and Peter de Marneffe, The Legalization of Drugs: For & Against , Cambridge University Press, 2005, 204pp., $18.99 (pbk), ISBN 0521546869.

Reviewed by William Hawk, James Madison University

In the United States the production, distribution and use of marijuana, heroin, and cocaine are crimes subjecting the offender to imprisonment. The Legalization of Drugs , appearing in the series "For and Against" edited by R. G. Frey for Cambridge University Press, raises the seldom-asked philosophical question of the justification, if any, of imprisoning persons for drug offenses.

Douglas Husak questions the justification for punishing persons who use drugs such as marijuana, heroin, and cocaine. He develops a convincing argument that imprisonment is never morally justified for drug use. Put simply, incarceration is such a harsh penalty that drug use, generally harmless to others and less harmful to the user than commonly supposed, fails to justify it. Any legal scheme that punishes drug users to achieve another worthy goal, such as creating a disincentive to future drug users, violates principles of justice.

Peter de Marneffe contends that under some circumstances society is morally justified in punishing persons who produce and distribute heroin. He argues a theoretical point that anticipated rises in drug abuse and consequent effects on young people may justify keeping heroin production and distribution illegal. According to de Marneffe's analysis, however, harsh prison penalties currently imposed on drug offenders are unjustified.

The points of discord between Husak's and de Marneffe's positions are serious but not as telling as is their implicit agreement. Current legal practices and policies which lead to lengthy incarceration of those who produce, distribute and use drugs such as marijuana, heroin, and cocaine are not, and cannot be, morally justified. Both arguments, against imprisoning drug users and for keeping heroin production illegal, merit a broad and careful reading.

The United States has erected an enormous legal structure involving prosecution and incarceration designed to prohibit a highly pleasurable, sometimes medically indicated and personally satisfying activity, namely using marijuana, heroin, and cocaine. At the same time, other pleasure-producing drugs, such as tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine, though legally regulated for the purposes of consumer safety and under-age consumption, can be purchased over the counter. As a result, while the health and safety risks of cigarettes may be greater than those proven to accompany marijuana, one can buy cigarettes from a vending machine and but go to prison for smoking marijuana. A rational legal system, according to Husak, demands a convincing, but as yet not forthcoming, explanation of why one pleasurable drug subjects users to the risk of imprisonment while the other is accommodated in restaurants.

Drug prohibitionists must face the problem that any "health risk" argument used to distinguish illicit drugs and subject offenders to prison sentences runs up against the known, yet tolerated, health risks of tobacco, as well as the additional health risks associated with incarceration. "Social costs" arguments targeting heroin or cocaine runs up against the known, yet tolerated, social costs of alcohol, as well as the additional social costs of incarceration. Even if one were to accept that illicit drugs were more harmful or exacted greater social costs than tobacco and alcohol (and the empirical studies referred to in the text do not generally support this thesis), that difference proves insufficient to justify imprisoning producers, distributors or especially users of illicit drugs.

Decriminalizing Drug Use. Douglas Husak presents a very carefully argued case for decriminalizing drug use. He begins his philosophical argument by clarifying the concepts and issues involved. To advocate the legalization of drugs calls for a legal system in which the production and sale of drugs are not criminal offenses. (p. 3) Criminalization of drugs makes the use of certain drugs a criminal offense, i.e. one deserving punishment. To argue for drug decriminalization, as Husak does, is not necessarily to argue for legalization of drugs . Husak entertains, but cautiously rejects the notion of a system where production and sale of drugs is illegal while use is not a crime. De Marneffe advocates such a system.

Punishing persons by incarceration demands justification. Since the state's use of punishment is a severe tool and incarceration is by its nature "degrading, demoralizing and dangerous" (p. 29) we must be able to provide "a compelling reason … to justify the infliction of punishment… ." (p. 34) Husak finds no compelling reason for imprisoning drug users. After considering four standard justifications for punishing drug users Husak concludes that "the arguments for criminalization are not sufficiently persuasive to justify the infliction of punishment."

Reasons to Criminalize Drug Use . 1) Drug users, it is claimed, should be punished in order to protect the health and well being of citizens . No doubt states are justified in protecting the health and well being of citizens. But does putting drug users in prison contribute to this worthy goal? Certainly not for those imprisoned. For those who might be deterred from using drugs the question is whether the drugs from which they are deterred by the threat of imprisonment actually pose a health risk. For one, Husak quotes research showing that currently illicit drugs do not obviously pose a greater health threat than alcohol or tobacco. For another, he quotes a statistic showing that approximately four times as many persons die annually from using prescribed medicines than die from using illegal drugs. In addition, one-fourth of all pack-a-day smokers lose ten to fifteen years of their lives but no one would entertain the idea of incarcerating smokers to further their health interests or in order to prevent non-smokers from beginning. In sum, Husak accepts that drug use poses health risks but contends that the risks are not greater than others that are socially accepted. Even if they were greater, imprisonment does not reduce, but compounds the health risks for prisoners.

2) Punishing drug users protects children . Husak here responds to de Marneffe's essay which focuses on potential drug abuse and promotes the welfare of children as a justification for keeping drug production and sale illegal. Husak finds punishing adolescent users a peculiar way to protect them. To punish one drug-using adolescent in order to prevent a non-using adolescent from using drugs is ineffective and also violates justice. Punishing adult users so that youth do not begin using drugs and do not suffer from neglect -- which is de Marneffe's position -- is not likely to prevent adolescents from becoming drug users, and even if it did, one would have to show that the harm prevented to the youth justifies imprisoning adults. Husak contends that punishing adults or youth, far from protecting youth, puts them at greater risk.

3) Some, e.g. former New York City mayor Guiliani, argue that punishing drug use prevents crime . Husak, conceding a connection between drug use and crime, turns the argument upside-down, showing how punishment increases rather than decreases crime. For one, criminalization of drugs forces the drug industry to settle disputes extra-legally. Secondly, drug decriminalization would likely lower drug costs thereby reducing economic crimes. Thirdly, to those who contend that illicit drugs may increase violence and aggression Husak responds that: a) empirical evidence does not support marijuana or heroin as causes of violence and b) empirical evidence does support alcohol, which is decriminalized, as leading to violence. Husak concludes "if we propose to ban those drugs that are implicated in criminal behavior, no drug would be a better candidate for criminalization than alcohol." (p. 70) Finally, punishing drug users likely increases crime rates since those imprisoned for drug use are released with greater tendencies and skills for future criminal activity.

4) Drug use ought to be punished because using drugs is immoral . In addition to standard philosophical objections to legal moralism, Husak contends that there is no good reason to think that recreational drug use is immoral. Drug use violates no rights. Other recreationally used drugs such as alcohol, tobacco or caffeine are not immoral. The only accounts according to which drug use is immoral are religiously based and generally not shared in the citizenry. Husak argues that legal moralism fails, and with it the attempts to justify imprisoning drug users because of health and well-being, protecting children, or reducing crime. Husak concludes, "If I am correct, prohibitionists are more clearly guilty of immorality than their opponents. The wrongfulness of recreational drug use, if it exists at all, pales against the immorality of punishing drug users." (p. 82)

Reasons to Decriminalize Drug Use. Husak's positive case for decriminalizing drug use begins with acknowledgement that drug use is or may be highly pleasurable. In addition, some drugs aid relaxation, others increase energy and some promote spiritual enlightenment or literary and artistic creativity. The simple fun and euphoria attendant to drug use should count for permitting it.

The fact that criminalization of drug use proves to be counter-productive provides Husak a set of final substantial reasons for decriminalizing use. Criminalizing drugs proves counter-productive along several different lines: 1) criminalization is aimed and selectively enforced against minorities, 2) public health risks increase because drugs are dealt on the street, 3) foreign policy is negatively affected by corrupt governments being supported solely because they support anti-drug policies, 4) a frank and open discussion about drug policy is impossible in the United States, 5) civil liberties are eroded by drug enforcement, 6) some government corruption stems from drug payoffs and 7) criminalization costs tens of billions of dollars per year.

Douglas Husak provides the conceptual clarity needed to work one's way through the various debates surrounding drug use and the law. He establishes a high threshold that must be met in order to justify the state's incarcerating someone. Having laid this groundwork Husak demonstrates that purported justifications for drug criminalization fail and that good reasons for decriminalizing drug use prevail. For persons who worry about what drug decriminalization means for children, Husak counsels that there is more to fear from prosecution and conviction of youth for using drugs than there is to fear from the drugs themselves.

Against Legalizing Drug Production and Distribution. Peter de Marneffe offers an argument against drug legalization . The argument itself is simple. If drugs are legalized, there will be more drug abuse. If there is more drug abuse that is bad. Drug abuse is sufficiently bad to justify making drug production and distribution illegal. Therefore, drugs should not be legalized. The weight of this argument is carried by the claim that the badness of drug abuse is sufficient to justify making drug production and sale illegal.

De Marneffe centers his argument on heroin. Heroin, he contends, is highly pleasurable but sharply depresses motivation to achieve worthwhile goals and meet responsibilities. Accordingly, children in an environment where heroin is legal will be subjected to neglect by heroin using parents and, if they themselves use heroin, they will be harmed by diminished motivation for achievement for the remainder of their lives. It is this later harm to the ambition and motivation of young people that, according to de Marneffe, justifies criminalizing heroin production and sale. As he puts it:

… the risk of lost opportunities that some individuals would bear as the result of heroin legalization justifies the risks of criminal liability and other burdens that heroin prohibition imposes on other individuals. The legalization of heroin would create a social environment -- call it the legalization environment -- in which some children would be at a substantially higher risk of irresponsible heroin abuse by their parents and in which some adolescents would be at a substantially higher risk of self-destructive heroin abuse. (p. 124)

Are the liberties of individual adult drug producers, distributors and users sacrificed? Yes, but this may be justified by de Marneffe's "burdens principle." According to the burdens principle, "the government violates a person's moral rights in adopting a policy that limits her liberty if and only if in adopting this policy the government imposes a burden on her that is substantially worse than the worst burden anyone would bear in the absence of this policy." (p. 159) According to this, de Marneffe claims that burdens on drug vendors or users may be justified by the prevention of harms to a particular individual or individuals. As he puts it:

What I claim in favor of heroin prohibition is that the reasons of at least one person to prefer her situation in a prohibition environment outweigh everyone else's reasons to prefer his or her situation in a legalization environment, assuming that the penalties are gradual and proportionate and other relevant conditions are met. (p. 161)

According to this view, the objective interest of a single adolescent in not losing ambition, motivation and drive justifies the imposition of burdens on other youth and adults who would prefer using drugs. Although Johnny might choose heroin use, his objective interest is for future motivation and ambition that is not harmed by heroin use.

De Marneffe's "burdens principle" seems to hold the whole society hostage to the objective liberty interests of one individual. Were this principle applied to drug producers or distributors who faced imprisonment it seems that imprisonment could not be justified. I suspect a concern for consistency here gives de Marneffe reason to make drug production and distribution illegal but without attaching harsh prison sentences for offenders. He advocates an environment where drugs are not legal, in order to protect youth against both abuse and their own choices that may cause them to become unmotivated, but recognizes that prison sentences are unjustified as a way to support such a system.

In The Legalization of Drugs the reader gets two interesting arguments. Douglas Husak makes a compelling case against punishing drug users. His position amounts to drug decriminalization with skepticism toward making drug production and sale illegal. On the other side, Peter de Marneffe justifies making drug production and sale illegal based upon the diminishment of future interests of young people. De Marneffe introduces a "burdens principle" which is likely much too strong a commitment to individual interests than could ever be realized in a civil society. In both instances, the reader is treated to arguments that effectively undermine current drug policy. The book provides philosophical argumentation that should stimulate a societal conversation about the justifiability of current drug laws.

We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

The most convincing argument for legalizing LSD, shrooms, and other psychedelics

by German Lopez

I have a profound fear of death. It’s not bad enough to cause serious depression or anxiety. But it is bad enough to make me avoid thinking about the possibility of dying — to avoid a mini existential crisis in my mind.

But it turns out there may be a better cure for this fear than simply not thinking about it. It’s not yoga, a new therapy program, or a medicine currently on the (legal) market. It’s psychedelic drugs — LSD, ibogaine, and psilocybin, which is found in magic mushrooms.

This is the case for legalizing hallucinogens. Although the drugs have gotten some media attention in recent years for helping cancer patients deal with their fear of death and helping people quit smoking, there’s also a similar potential boon for the nonmedical, even recreational psychedelic user. As hallucinogens get a renewed look by researchers, they’re finding that the substances may improve almost anyone’s mood and quality of life — as long as they’re taken in the right setting, typically a controlled environment.

This isn’t something that even drug policy reformers are comfortable calling for yet. “There’s not any political momentum for that right now,” Jag Davies, who focuses on hallucinogen research at the Drug Policy Alliance, said, citing the general public’s views of psychedelics as extremely dangerous — close to drugs like crack cocaine, heroin, and meth.

But it’s an idea that experts and researchers are taking more seriously. And while the studies are new and ongoing, and a national regulatory model for legal hallucinogens is practically nonexistent, the available research is very promising — enough to reconsider the demonization and prohibition of these potentially amazing drugs.

Hallucinogens’ potentially huge benefit: ego death

Mushroom, mushroom.

The most remarkable potential benefit of hallucinogens is what’s called “ego death,” an experience in which people lose their sense of self-identity and, as a result, are able to detach themselves from worldly concerns like a fear of death, addiction, and anxiety over temporary — perhaps exaggerated — life events.

When people take a potent dose of a psychedelic, they can experience spiritual, hallucinogenic trips that can make them feel like they’re transcending their own bodies and even time and space. This, in turn, gives people a lot of perspective — if they can see themselves as a small part of a much broader universe, it’s a lot easier for them to discard personal, relatively insignificant and inconsequential concerns about their own lives and death.

That may sound like pseudoscience. And the research on hallucinogens is so early that scientists don’t fully grasp how it works. But it’s a concept that’s been found in some medical trials, and something that many people who’ve tried hallucinogens can vouch for experiencing. It’s one of the reasons why preliminary , small studies and research from the 1950s and ‘60s found hallucinogens can treat — and maybe cure — addiction, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Charles Grob, a UCLA professor of psychiatry and pediatrics who studies psychedelics, conducted a study that gave psilocybin to late-stage cancer patients. “The reports I got back from the subjects, from their partners, from their families were very positive — that the experience was of great value, and it helped them regain a sense of purpose, a sense of meaning to their life,” he told me in 2014. “The quality of their lives notably improved.”

In a fantastic look at the research, Michael Pollan at the New Yorker captured the phenomenon through the stories of cancer patients who participated in hallucinogen trials:

Death looms large in the journeys taken by the cancer patients. A woman I’ll call Deborah Ames, a breast-cancer survivor in her sixties (she asked not to be identified), described zipping through space as if in a video game until she arrived at the wall of a crematorium and realized, with a fright, “I’ve died and now I’m going to be cremated. The next thing I know, I’m below the ground in this gorgeous forest, deep woods, loamy and brown. There are roots all around me and I’m seeing the trees growing, and I’m part of them. It didn’t feel sad or happy, just natural, contented, peaceful. I wasn’t gone. I was part of the earth.” Several patients described edging up to the precipice of death and looking over to the other side. Tammy Burgess, given a diagnosis of ovarian cancer at fifty-five, found herself gazing across “the great plain of consciousness. It was very serene and beautiful. I felt alone but I could reach out and touch anyone I’d ever known. When my time came, that’s where my life would go once it left me and that was O.K.”

But Mark Kleiman, a drug policy expert at New York University’s Marron Institute, noted that these benefits don’t apply only to terminally ill patients. The studies conducted so far have found benefits that apply to anyone : a reduced fear of death, greater psychological openness, and increased life satisfaction.

“It’s not required to have a disease to be afraid of dying,” Kleiman said. “But it’s probably an undesirable condition if you have the alternative available. And there’s now some evidence that these experiences can make the person less afraid to die.”

Kleiman added, “The obvious application is people who are currently dying with a terminal diagnosis. But being born is a terminal diagnosis. And people’s lives might be better if they live out of the valley of the shadow of death.”

Again, the current research on all of this is early, with much of the science still relying on studies from the ‘50s and ‘60s. But the most recent preliminary findings are promising enough that experts like Kleiman are cautiously considering how to build a model that would let people take these potentially beneficial drugs legally — while also acknowledging that psychedelics do pose some big risks.

The two big risks of hallucinogens: accidents and bad trips

Charles Grob, a UCLA professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, is leading the way in psychedelic research.

Hallucinogens aren’t perfectly safe, but they’re not dangerous in the way some people might think. As Grob previously told me , there’s little to no chance that someone will become addicted to psychedelics — they’re not physically addictive like heroin or tobacco, and the experiences are so demanding and draining that a great majority of people simply won’t be interested in constantly taking the drugs. He also said that hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, which can cause the disturbances widely known as “flashbacks,” is “uncommon, but you will see it, particularly among someone who has taken hallucinogens a lot.”

Kleiman drew a comparison to marijuana to explain the risks. “The risk with cannabis is, primarily, that you lose control of your cannabis taking,” he said. “The risk with LSD is primarily that you’ll do something stupid to ruin the experience, or you’ll have such a scary experience that it’ll leave you damaged. But those are safety risks rather than addiction risks.”

This gets to the two major dangers of hallucinogens: accidents and bad trips. The first risk is similar to what you’d expect from other drugs: When people are intoxicated in any way, they’re more prone to doing bad, dumb things. As Kleiman explained, “People take LSD and think they can fly and jump off buildings. It’s true that it’s a drug warrior fairy tale, but it’s also true in that it actually happens. People drop acid and run out in traffic. People do stupid shit under high doses of psychedelics.”

Bad trips are also a concern. A bad psychedelic experience can result in psychotic episodes, a lost sense of reality, and even long-term psychological trauma in very rare situations, especially among people using other drugs or with a history of mental health issues. Just like psychedelics can lead to long-term psychological benefits, they can lead to long-term psychological pain.

These risks are why not many people are seriously discussing legalizing hallucinogens in the same way the US allows alcohol or is now beginning to allow marijuana. But the potential benefits of hallucinogens are leading some experts to consider how these drugs could be legalized in some capacity.

“I think it’s a bad idea to treat hallucinogens like we treat cocaine or cannabis,” Kleiman said. “They pose different risks and offer different benefits.” He added, “But I don’t think we’re ever going to free these substances from careful legal control.”

How hallucinogens can be legalized

Drop some LSD — but maybe only in a controlled environment.

So how can you maximize the benefits and minimize the risks? The most convincing idea so far is letting people take psychedelics in a controlled setting, in which multiple participants can be watched over by trained supervisors who ensure the experience doesn’t go poorly.

So far, this is what the medical side has focused on: The typical medical trial involves doctors watching over a deathly ill patient or someone dealing with addiction who takes psilocybin. But if the concept is expanded to allow nonmedical users, then perhaps professionals who aren’t doctors but are trained in guiding someone through a trip could take up the role. “I imagine someone who has training in managing that experience, and a license, and liability insurance, and a facility,” Kleiman said.

Here’s how it would work: A psychedelic user would go through some sort of preparation period to make sure she knows what she’s getting into. Then she could make an appointment at a place offering these services. She would show up at this appointment, take the drug of her choice (or whatever the facility provides), and wait to allow it to kick in. As the trip occurs, a supervisor would watch over the user — not being too pushy, but making sure he’s available to guide her through any rough spots. In some studies, doctors have also prepared certain activities — a soundtrack or food, for example — that may help set the right mood and setting for someone on psychedelics. Different places will likely experiment with different approaches, including how many people can participate at once and how a room should look.

The most convincing idea so far is letting people take psychedelics in a controlled setting

Kleiman also envisions a potential system in which people can eventually graduate to using the drug solo. “It’s like Red Cross water safety instruction,” he said. “You start out, you’re a newbie. You don’t go into the pool without a trained, certified person to watch you, guide you, and keep you safe. After a while, your teacher gives you a test to certify that you’re safe to be in the water alone. And you might even get certified to become a trainer, so you can guide newbies yourself.”

If pulled off correctly, this would maximize the best possible outcomes and minimize the worst. Supervisors could help prevent accidents, and they could walk people through good and bad trips, letting users relax and get something meaningful out of the experience.

There are risks to the controlled setting. If a supervisor is poorly trained or malicious, it could lead to a horrific trip that could actually worsen someone’s mental state. This is why regulation and licensing will be crucial to getting the idea right.

Ethan Nadelmann, executive director of the Drug Policy Alliance, argued for a looser model that could, for example, allow psychedelics to be sold over the counter. “You dramatically decrease the black market. So long as you have people who have to go through some sort of gatekeeper, or who can be denied, you’re going to continue to have a black market,” Nadelmann said. “Secondly, this means the percent of consumers who got a product of known potency and purity from a reliable source would increase.”

But the black market demand for psychedelics is very small, with only 0.5 percent of Americans 12 and older in 2013 saying they used hallucinogens in the past month. So allowing over-the-counter sales would likely have a tiny benefit at best on public health and criminal groups’ profits from the black market.

The debate about which model works best will likely go on for some time, especially if different places test different approaches. There’s no doubt it will be tricky to hash out exactly how to legalize and regulate these drugs, as some states are learning with marijuana .

But if we know the benefits to public health and well-being are real, it’s irresponsible to let the potential go untapped. It may soon be time for America to seriously consider legalizing LSD, magic mushrooms, and other psychedelic drugs.

- Health Care

Most Popular

- The astonishing link between bats and the deaths of human babies

- iPad kids speak up

- Has The Bachelorette finally gone too far?

- How Russia secretly paid millions to a bunch of big right-wing podcasters

- Take a mental break with the newest Vox crossword

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Explainers

The case for and against fracking, politics aside.

From granola bars to chips, more studies are revealing that UPFs are tied to diseases like cancer and depression.

The factors that lead to tragedies like the Apalachee High School shooting are deeply ingrained in US politics, culture, and law.

Polls show a tight race. But there are other figures that can help explain where this campaign is headed.

The raids come amid escalating violence in the Palestinian territory.

The privately funded venture will test out new aerospace technology.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- In Debate Over Legalizing Marijuana, Disagreement Over Drug’s Dangers

In Their Own Words: Supporters and Opponents of Legalization

Table of contents.

- About the Survey

Survey Report

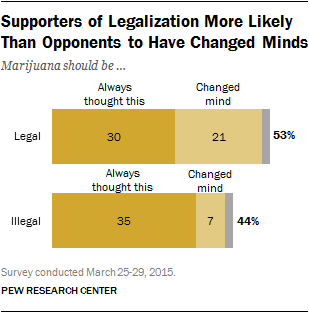

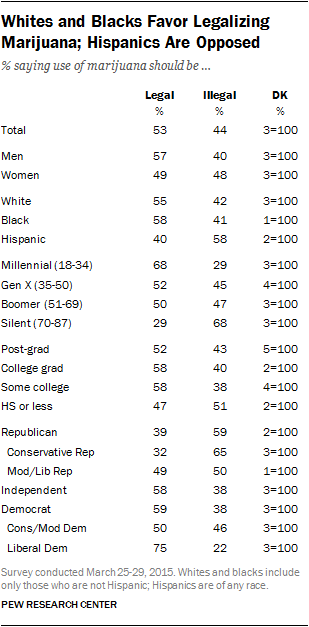

Public opinion about legalizing marijuana, while little changed in the past few years, has undergone a dramatic long-term shift. A new survey finds that 53% favor the legal use of marijuana, while 44% are opposed. As recently as 2006, just 32% supported marijuana legalization, while nearly twice as many (60%) were opposed.

Millennials (currently 18-34) have been in the forefront of this change: 68% favor legalizing marijuana use, by far the highest percentage of any age cohort. But across all generations –except for the Silent Generation (ages 70-87) – support for legalization has risen sharply over the past decade.

The latest national survey by the Pew Research Center, conducted March 25-29 among 1,500 adults, finds that supporters of legalizing the use of marijuana are far more likely than opponents to say they have changed their mind on this issue.

Among the public overall, 30% say they support legalizing marijuana use and have always felt that way, while 21% have changed their minds; they say there was a time when they thought it should be illegal. By contrast, 35% say they oppose legalization and have always felt that way; just 7% have changed their minds from supporting to opposing legalization.

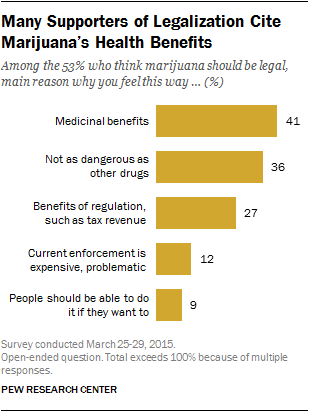

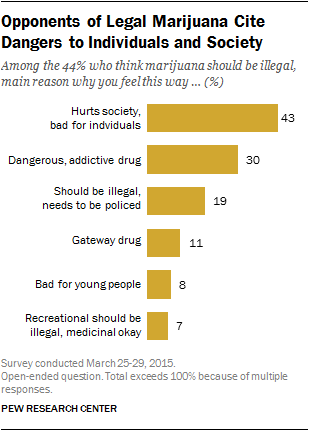

When asked, in their own words, why they favor or oppose legalizing marijuana, people on opposite sides of the issue offer very different perspectives. But a common theme is the danger posed by marijuana: Supporters of legalization mention its perceived health benefits, or see it as no more dangerous than other drugs. To opponents, it is a dangerous drug, one that inflicts damage on people and society more generally.

The most frequently cited reasons for supporting the legalization of marijuana are its medicinal benefits (41%) and the belief that marijuana is no worse than other drugs (36%) –with many explicitly mentioning that they think it is no more dangerous than alcohol or cigarettes.

With four states and Washington, D.C. having passed measures to permit the use of marijuana for personal use, 27% of supporters say legalization would lead to improved regulation of marijuana and increased tax revenues. About one-in-ten (12%) cite the costs and problems of enforcing marijuana laws or say simply that people should be free to use marijuana (9%).

Why Should Marijuana Be Legal? Voices of Supporters

Main reason you support legalizing use of marijuana…

“My grandson was diagnosed with epilepsy a year ago and it has been proven that it helps with the seizures.” Female, 69

“I think crime would be lower if they legalized marijuana. It would put the drug dealers out of business.” Female, 62

“Because people should be allowed to have control over their body and not have the government intervene in that.” Male, 18