Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2024

Uncovering the essence of diverse media biases from the semantic embedding space

- Hong Huang 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Hua Zhu 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ,

- Wenshi Liu 4 , 5 ,

- Hua Gao 5 ,

- Hai Jin 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Bang Liu 6

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 656 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1280 Accesses

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

Media bias widely exists in the articles published by news media, influencing their readers’ perceptions, and bringing prejudice or injustice to society. However, current analysis methods usually rely on human efforts or only focus on a specific type of bias, which cannot capture the varying magnitudes, connections, and dynamics of multiple biases, thus remaining insufficient to provide a deep insight into media bias. Inspired by the Cognitive Miser and Semantic Differential theories in psychology, and leveraging embedding techniques in the field of natural language processing, this study proposes a general media bias analysis framework that can uncover biased information in the semantic embedding space on a large scale and objectively quantify it on diverse topics. More than 8 million event records and 1.2 million news articles are collected to conduct this study. The findings indicate that media bias is highly regional and sensitive to popular events at the time, such as the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Furthermore, the results reveal some notable phenomena of media bias among multiple U.S. news outlets. While they exhibit diverse biases on different topics, some stereotypes are common, such as gender bias. This framework will be instrumental in helping people have a clearer insight into media bias and then fight against it to create a more fair and objective news environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is newsworthy about Covid-19? A corpus linguistic analysis of news values in reports by China Daily and The New York Times

Negativity drives online news consumption

Media bias through collocations: a corpus-based study of Egyptian and Ethiopian news coverage of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

Introduction.

In the era of information explosion, news media play a crucial role in delivering information to people and shaping their minds. Unfortunately, media bias, also called slanted news coverage, can heavily influence readers’ perceptions of news and result in a skewing of public opinion (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ; Sunstein, 2002 ). This influence can potentially lead to severe societal problems. For example, a report from FAIR has shown that Verizon management is more than twice as vocal as worker representatives in news reports about the Verizon workers’ strike in 2016 Footnote 1 , putting workers at a disadvantage in the news and contradicting the principles of fair and objective journalism. Unfortunately, this is just the tip of the media bias iceberg.

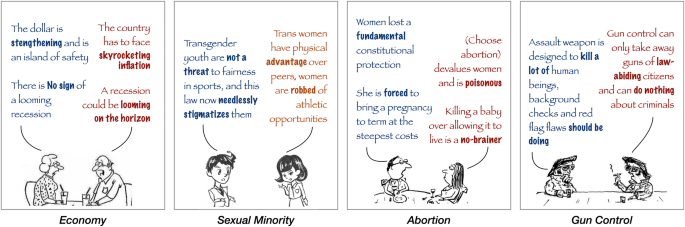

Media bias can be defined as the bias of journalists and news producers within the mass media in selecting and covering numerous events and stories (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ). This bias can manifest in various forms, such as event selection, tone, framing, and word choice (Hamborg et al. 2019 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). Given the vast number of events happening in the world at any given moment, even the most powerful media must be selective in what they choose to report instead of covering all available facts in detail (Downs, 1957 ). This selectivity can result in the perception of bias in the news coverage, whether intentional or unintentional. Academics in journalism studies attempt to explain the news selection process by developing taxonomies of news values (Galtung and Ruge, 1965 ; Harcup and O’neill, 2001 , 2017 ), which refer to certain criteria and principles that news editors and journalists consider when selecting, editing, and reporting the news. These values help determine which stories should be considered news and the significance of these stories in news reporting. However, different news organizations and journalists may emphasize different news values based on their specific objectives and audience. Consequently, a media outlet may be very keen on reporting events about specific topics while turning a blind eye to others. For example, news coverage often ignores women-related events and issues with the implicit assumption that they are less critical than men-related contents (Haraldsson and Wängnerud, 2019 ; Lühiste and Banducci, 2016 ; Ross and Carter, 2011 ). Once events are selected, the media must consider how to organize and write their news articles. At that time, the choice of tone, framing, and word is highly subjective and can introduce bias. Specifically, the words used by the authors to refer to different entities may not be neutral but instead imply various associations and value judgments (Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). As shown in Fig. 1 , the same topic can be expressed in entirely different ways, depending on a media outlet’s standpoint Footnote 2 . For example, certain “right-wing” media outlets tend to support legal abortion, while some “left-wing” ones oppose it.

The blue and red fonts represent the views of some “left-wing” and “right-wing” media outlets, respectively.

In fact, media bias is influenced by many factors: explicit factors such as geographic location, media position, editorial guideline, topic setting, and so on; obscure factors such as political ideology (Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ; MacGregor, 1997 ; Merloe, 2015 ), business reason (Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ; Paul and Elder, 2004 ), and personal career (Baron, 2006 ), etc. Besides, some studies also summarize these factors related to bias as supply-side and demand-side ones (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). The influence of these complex factors makes the emergence of media bias inevitable. However, media bias may hinder readers from forming objective judgments about the real world, lead to skewed public opinion, and even exacerbate social prejudices and unfairness. For example, the New York Times supports Iranian women’s saying no to hijabs in defense of women’s rights Footnote 3 while criticizing the Chinese government’s initiative to encourage Uyghur women to remove hijabs and veils Footnote 4 . Besides, the influence of news coverage on voter behavior is a subject of ongoing debate. While some studies indicate that slanted news coverage can influence voters and election outcomes (Bovet and Makse, 2019 ; DellaVigna and Kaplan, 2008 ; Grossmann and Hopkins, 2016 ), others suggest that this influence is limited in certain circumstances (Stroud, 2010 ). Fortunately, research on media bias has drawn attention from multiple disciplines.

In social science, the study of media bias has a long tradition dating back to the 1950s (White, 1950 ). So far, most of the analyses in social science have been qualitative, aiming to analyze media opinions expressed in the editorial section (e.g., endorsements (Ansolabehere et al. 2006 ), editorials (Ho et al. 2008 ), ballot propositions (Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015a )) or find out biased instances in news articles by human annotations (Niven, 2002 ; Papacharissi and de Fatima Oliveira, 2008 ; Vaismoradi et al. 2013 ). Some researchers also conduct quantitative analysis, which primarily involves counting the frequency of specific keywords or articles related to certain issues (D’Alessio and Allen, 2000 ; Harwood and Garry, 2003 ; Larcinese et al. 2011 ). In particular, there are some attempts to estimate media bias using automatic tools (Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ), and they commonly rely on text similarity and sentiment computation (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010 ; Gentzkow et al. 2006 ; Lott Jr and Hassett, 2014 ). In summary, social science research on media bias has yielded extensive and effective methodologies. These methodologies interpret media bias from diverse perspectives, marking significant progress in the realm of media studies. However, these methods usually rely on manual annotation and analysis of the texts, which requires significant manual effort and expertise (Park et al. 2009 ), thus might be inefficient and subjective. For example, in a quantitative analysis, researchers might devise a codebook with detailed definitions and rules for annotating texts, and then ask coders to read and annotate the corresponding texts (Hamborg et al. 2019 ). Developing a codebook demands substantial expertise. Moreover, the standardization process for text annotation is subjective, as different coders may interpret the same text differently, thus leading to varied annotations.

In computer science, research on social media is extensive (Lazaridou et al. 2020 ; Liu et al. 2021b ; Tahmasbi et al. 2021 ), but few methods are specifically designed to study media bias (Hamborg et al. 2019 ). Some techniques that specialize in the study of media bias focus exclusively on one type of bias (Huang et al. 2021 ; Liu et al. 2021b ; Zhang et al. 2017 ), thus not general enough. In natural language processing (NLP), research on the bias of pre-trained models or language models has attracted much attention (Qiang et al. 2023 ), aiming to identify and reduce the potential impact of bias in pre-trained models on downstream tasks (Huang et al. 2020 ; Liu et al. 2021a ; Wang et al. 2020 ). In particular, some studies on pre-trained word embedding models show that they have captured rich human knowledge and biases (Caliskan et al. 2017 ; Grand et al. 2022 ; Zeng et al. 2023 ). However, such works mainly focus on pre-trained models rather than media bias directly, which limits their applicability to media bias analysis.

A major challenge in studying media bias is that the evaluation of media bias is highly subjective because individuals have varying evaluation criteria for bias. Take political bias as an example, a story that one person views as neutral may appear to be left-leaning or right-leaning by someone else. To address this challenge, we develop an objective and comprehensive media bias analysis framework. We study media bias from two distinct but highly relevant perspectives: the macro level and the micro level. From the macro perspective, we focus on the event selection bias of each media, i.e., the types of events each media tends to report on. From the micro perspective, we focus on the bias introduced by media in the choice of words and sentence construction when composing news articles about the selected events.

In news articles, media outlets convey their attitudes towards a subject through the contexts surrounding it. However, the language used by the media to describe and refer to entities may not be purely neutral descriptors but rather imply various associations and value judgments. According to the cognitive miser theory in psychology, the human mind is considered a cognitive miser who tends to think and solve problems in simpler and less effortful ways to avoid cognitive effort (Fiske and Taylor, 1991 ; Stanovich, 2009 ). Therefore, faced with endless news information, ordinary readers will tend to summarize and remember the news content simply, i.e., labeling the things involved in news reports. Frequent association of certain words with a particular entity or subject in news reports can influence a media outlet’s loyal readers to adopt these words as labels for the corresponding item in their cognition due to the cognitive miser effect. Unfortunately, such a cognitive approach is inadequate and susceptible to various biases. For instance, if a media outlet predominantly focuses on male scientists while neglecting their female counterparts, some naive readers may perceive scientists to be mostly male, leading to a recognition bias in their perception of the scientist and even forming stereotypes unconsciously over time. According to the “distributional hypothesis” in modern linguistics (Firth, 1957 ; Harris, 1954 ; Sahlgren, 2008 ), a word’s meaning is characterized by the words occurring in the same context as it. Here, we simplify the complex associations between different words (or entities/subjects) and their respective context words into co-occurrence relationships. An effective technique to capture word semantics based on co-occurrence information is neural network-based word embedding models (Kenton and Toutanova, 2019 ; Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ).

Word embedding models represent each word in the vocabulary as a vector (i.e., word embedding) within the word embedding space. In this space, words that frequently co-occur in similar contexts are positioned close to each other. For instance, if a media outlet predominantly features male scientists, the word “scientist” and related male-centric terms, such as “man” and “he” will frequently co-occur. Consequently, these words will cluster near the word “scientist” in the embedding space, while female-related words occupy more distant positions. This enables us to evaluate the media outlet’s gender bias concerning the term “scientist” by comparing the embedding distances between “scientist” and words associated with both males and females. This approach aligns closely with the Semantic Differential theory in psychology (Osgood et al. 1957 ), which gauges an individual’s attitudes toward various concepts, objects, and events using bipolar scales constructed from adjectives with opposing semantics. In this study, to identify media bias from news articles, we first define two sets of words with opposite semantics for each topic to develop media bias evaluation scales. Then, we quantify media bias on each topic by calculating the embedding distance difference between a target word (e.g., scientist) and these two sets of words (e.g., female-related words and male-related words) in the word embedding space.

Compared with the bias in news articles, event selection bias is more obscure, as only events of interest to the media are reported in the final articles, while events deliberately ignored by the media remain invisible to the public. Similar to the co-occurrence relationship between words mentioned earlier, two media outlets that frequently select and report on the same events should exhibit similar biases in event selection, as two words that occur frequently in the same contexts have similar semantics. Therefore, we refer to Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA (Deerwester et al. 1990 )) and generate vector representation (i.e., media embedding) for each media via truncated singular value decomposition (Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 )). Essentially, a media embedding encodes the distribution of the events that a media outlet tends to report on. Therefore, in the media embedding space, media outlets that often select and report on the same events will be close to each other due to similar distributions of the selected events. If a media outlet shows significant differences in such a distribution compared to other media outlets, we can conclude that it is biased in event selection. Inspired by this, we conduct clustering on the media embeddings to study how different media outlets differ in the distribution of selected events, i.e., the so-called event selection bias.

These two methodologies, designed for micro-level and macro-level analysis, share a fundamental similarity: both leverage data-driven embedding models to represent each word or media outlet as a distinctive vector within the embedding space and conduct further analysis based on these vectors. Therefore, in this study, we integrate both methodologies into a unified framework for media bias analysis. We aim to uncover media bias on a large scale and quantify it objectively on diverse topics. Our experiment results show that: (1) Different media outlets have different preferences for various news events, and those from the same country or organization tend to share more similar tastes. Besides, the occurrence of international hot events will lead to the convergence of different media outlets’ event selection. (2) Despite differences in media bias, some stereotypes, such as gender bias, are common among various media outlets. These findings align well with our empirical understanding, thus validating the effectiveness of our proposed framework.

Data and methods

The first dataset is the GDELT Mention Table, a product of the Google Jigsaw-backed GDELT project Footnote 5 . This project aims to monitor news reports from all over the world, including print, broadcast, and online sources, in over 100 languages. Each time an event is mentioned in a news report, a new row is added to the Mention Table (See Supplementary Information Tab. S1 for details). Given that different media outlets may report on the same event at varying times, the same event can appear in multiple rows of the table. While the fields GlobalEventID and EventTimeDate are globally unique attributes for each event, MentionSourceName and MentionTimeDate may differ. Based on the GlobalEventID and MentionSourceName fields in the Mention Table, we can count the number of times each media outlet has reported on each event, ultimately constructing a “media-event” matrix. In this matrix, the element at ( i , j ) denotes the number of times that media outlet j has reported on the event i in past reports.

As a global event database, GDELT collects a vast amount of global events and topics, encompassing news coverage worldwide. However, despite its widespread usage in many studies, there are still some noteworthy issues. Here, we highlight some of the issues to remind readers to use it more cautiously. Above all, while GDELT provides a vast amount of data from various sources, it cannot capture every event accurately. It relies on automated data collection methods, and this could result in certain events being missed. Furthermore, its algorithms for event extraction and categorization cannot always perfectly capture the nuanced context and meaning of each event, which might lead to potential misinterpretations.

The second dataset is built on MediaCloud Footnote 6 , an open-source platform for research on media ecosystems. MediaCloud’s API enables the querying of news article URLs for a given media outlet, which can then be retrieved using a web crawler. In this study, we have collected more than 1.2 million news articles from 12 mainstream US media outlets in 2016-2021 via MediaCloud’s API (See Supplementary Information Tab. S2 for details).

Media bias estimation by media embedding

Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA (Deerwester et al. 1990 )) is a well-established technique for uncovering the topic-based semantic relationships between text documents and words. By performing truncated singular value decomposition (Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 )) on a “document-word” matrix, LSA can effectively capture the topics discussed in a corpus of text documents. This is accomplished by representing documents and words as vectors in a high-dimensional embedding space, where the similarity between vectors reflects the similarity of the topics they represent. In this study, we apply this idea to media bias analysis by likening media and events to documents and words, respectively. By constructing a “media-event” matrix and performing Truncated SVD, we can uncover the underlying topics driving the media coverage of specific events. Our hypothesis posits that media outlets mentioning certain events more frequently are more likely to exhibit a biased focus on the topics related to those events. Therefore, media outlets sharing similar topic tastes during event selection will be close to each other in the embedding space, which provides a good opportunity to shed light on the media’s selection bias.

The generation procedures for media embeddings are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S1 . First, a “media-event” matrix denoted as A m × n is constructed based on the GDELT Mention Table, where m and n represent the total number of media outlets and events, respectively. Each entry A i , j represents the number of times that media i has reported on event j . Subsequently, Truncated SVD is performed on the matrix A m × n , which results in three matrices: U m × k , Σ k × k and \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) . The product of Σ k × k and \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) is represented by E k × n . Each column of E k × n corresponds to a k -dimensional vector representation for a specific media outlet, i.e., a media embedding. Specifically, the decomposition of matrix A m × n can be formulated as follows:

Equation( 1 ) defines the complete singular value decomposition of A m × n . Both \({U}_{m\times m}^{0}\) and \({({V}_{n\times n}^{0})}^{T}\) are orthogonal matrices. \({{{\Sigma }}}_{m\times n}^{0}\) is a m × n diagonal matrix whose diagonal elements are non-negative singular values of the matrix A m × n in descending order. Equation( 2 ) defines the truncated singular value decomposition (i.e., Truncated SVD) of A m × n . Based on the result of complete singular value decomposition, the part corresponding to the largest k singular values is equivalent to the result of Truncated SVD. Specifically, U m × k comprises the first k columns of the matrix \({U}_{m\times m}^{0}\) , while \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) comprises the first k rows of the matrix \({({V}_{n\times n}^{0})}^{T}\) . Additionally, the diagonal matrix Σ k × k is composed of the first k diagonal elements of \({{{\Sigma }}}_{m\times n}^{0}\) , representing the largest k singular values of A m × n . In particular, the media embedding model is defined as the product of the matrices Σ k × k and \({V}_{n\times k}^{T}\) , which has n k -dimensional media embeddings as follows:

To measure the similarity between two media embedding sets, we refer to Word Mover Distance (WMD (Kusner et al. 2015 )). WMD is designed to measure the dissimilarity between two text documents based on word embedding. Here, we subtract the optimal value of the original WMD objective function from 1 to convert the dissimilarity value into a normalized similarity score that ranges from 0 to 1. Specifically, the similarity between two media embedding sets is formulated as follows:

Let n denote the total number of media outlets, and s be an n -dimensional vector corresponding to the first media embedding set. For each i , the weight of media i in the embedding set is given by \({s}_{i}=\frac{1}{\sum_{k = 1}^{n}{t}_{i}}\) , where t i = 1 if media i is in the embedding set, and t i = 0 otherwise. Similarly, \({s}^{{\prime} }\) is another n -dimensional vector corresponding to the second media embedding set. The distance between media i and j is calculated using c ( i , j ) = ∥ e i − e j ∥ 2 , where e i and e j are the embedding representations of media i and j , respectively. The flow matrix T ∈ R n × n is used to determine how much media i in s travels to media j in \({s}^{{\prime} }\) . Specifically, T i , j ≥ 0 denotes the amount of flow from media i to media j .

Media bias estimation by word embedding

Word embedding models (Kenton and Toutanova, 2019 ; Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ) are widely used in text-related tasks due to their ability to capture rich semantics of natural language. In this study, we regard media bias in news articles as a special type of semantic and capture it using Word2Vec (Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ).

Supplementary Information Fig. S2 presents the process of building media corpora and training word embedding models to capture media bias. First, we reorganize the corpus for each media outlet by up-sampling to ensure that each media corpus contains the same number of news articles. The advantage of up-sampling is that it makes full use of the existing media corpus data, as opposed to discarding part of the data like down-sampling does. Second, we superimpose all 12 media corpora to construct a large base corpus and pre-train a Word2Vec model denoted as W b a s e based on it. Third, we fine-tune the same pre-trained model W b a s e using the specific corpus of each media outlet separately and get 12 fine-tuned models denoted as \({W}^{{m}_{i}}\) ( i = 1, 2, . . . 12).

In particular, the main objective of reorganizing the original corpora is to ensure that each corpus equivalently contributes to the pre-training process, in case a large corpus from certain media dominates the pre-trained model. As shown in Supplementary Information Tab. S2 , the largest corpus in 2016-2021 is from USA Today, which contains 295,518 news articles. Therefore, we can reorganize the other 11 media corpora by up-sampling to ensure that each of the 12 corpora has 295,518 articles. For example, as for NPR’s initial corpus, which has 14,654 news articles, we first repeatedly superimpose 295, 518//14, 654 = 20 times to get 293,080 articles and then randomly sample 295, 518%14, 654 = 2, 438 from the initial 14,654 articles as a supplement. Finally, we can get a reorganized NPR corpus with 295,518 articles.

Semantic Differential is a psychological technique proposed by (Osgood et al. 1957 ) to measure people’s psychological attitudes toward a given conceptual object. In the Semantic Differential theory, a given object’s semantic attributes can be evaluated in multiple dimensions. Each dimension consists of two poles corresponding to a pair of adjectives with opposite semantics (i.e., antonym pairs). The position interval between the poles of each dimension is divided into seven equally-sized parts. Then, given the object, respondents are asked to choose one of the seven parts in each dimension. The closer the position is to a pole, the closer the respondent believes the object is semantically related to the corresponding adjective. Supplementary Information Fig. S3 provides an example of Semantic Differential.

Constructing evaluation dimensions using antonym pairs in Semantic Differential is a reliable idea that aligns with how people generally evaluate things. For example, when imagining the gender-related characteristics of an occupation (e.g., nurse), individuals usually weigh between “man” and “woman”, both of which are antonyms regarding gender. Likewise, when it comes to giving an impression of the income level of the Asian race, people tend to weigh between “rich” (high income) and “poor” (low income), which are antonyms related to income. Based on such consistency, we can naturally apply Semantic Differential to measure a media outlet’s attitudes towards different entities and concepts, i.e., media bias.

Specifically, given a media m , a topic T (e.g., gender) and two semantically opposite topic word sets \(P={\{{p}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{K}_{1}}\) and \(\neg P={\{\neg {p}_{i}\}}_{i = 1}^{{K}_{2}}\) about topic T , media m ’s bias towards the target x can be defined as:

Here, K 1 and K 2 denote the number of words in topic word sets P and ¬ P , respectively. W m represents the word embedding model obtained by fine-tuning W b a s e using the specific corpus of media m . \(\overrightarrow{{W}_{x}^{m}}\) is the embedding representation of the word x in W m . S i m is a similarity function used to measure the similarity between two vectors (i.e., word embeddings). In practice, we employ the cosine similarity function, which is commonly used in the field of natural language processing. In particular, equation( 5 ) calculates the difference of average similarities between the target word x and two semantically opposite topic word sets, namely P and ¬ P . Similar to the antonym pairs in Semantic Differential, such two topic word sets are used to construct the evaluation scale of media bias. In practice, to ensure the stability of the results, we have repeated this experiment five times, each time with a different random seed for up-sampling. Therefore, the final results shown in Fig. 4 are the average bias values for each topic.

The idea of recovering media bias by embedding methods

We first analyzed media bias from the aspect of event selection to study which topics a media outlet tends to focus on or ignore. Based on the GDELT database, we constructed a large “media-event" matrix that records the times each media outlet mentioned each event in news reports from February to April 2022. To extract media bias information, we referred to the idea of Latent Semantic Analysis (Deerwester et al. 1990 ) and performed Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 ) on this matrix to generate vector representation (i.e., media embedding) for each media outlet (See Methods for details). Specifically, outlets with similar event selection bias (i.e., outlets that often report on events of similar topics) will have similar media embeddings. Such a bias encoded in the vector representation of each outlet is exactly the first type of media bias we aim to study.

Then, we analyzed media bias in news articles to investigate the value judgments and attitudes conveyed by media through their news articles. We collected more than 1.2 million news articles from 12 mainstream US news outlets, spanning from January 2016 to December 2021, via MediaCloud’s API. To identify media bias from each outlet’s corpus, we performed three sequential steps: (1) Pre-train a Word2Vec word embedding model based on all outlets’ corpora. (2) Fine-tune the pre-trained model by using the specific corpus of each outlet separately and obtain 12 fine-tuned models corresponding to the 12 outlets. (3) Quantify each outlet’s bias based on the corresponding fine-tuned model, combined with the idea of Semantic Differential, i.e., measuring the embedding similarities between the target words and two sets of topic words with opposite semantics (See Methods for details). An example of using Semantic Differential (Osgood et al. 1957 ) to quantify media bias is shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S4 .

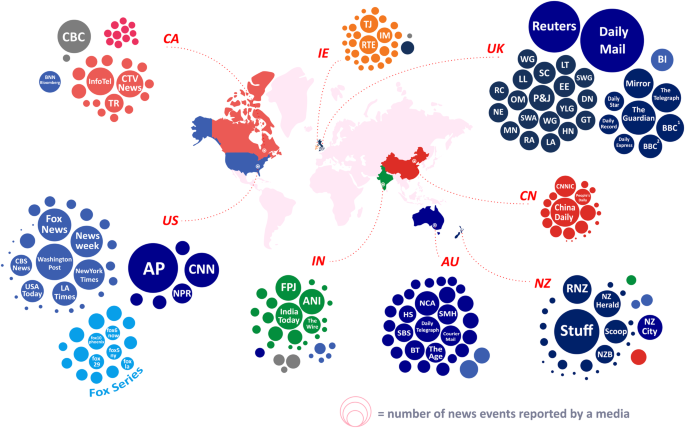

Media show significant clustering due to their regions and organizations

In this experiment, we aimed to capture and analyze the event selection bias of different media outlets based on the proposed media embedding methodology. To achieve a comprehensive analysis, we selected 247 media outlets from 8 countries ( Supplementary Information Tab. S6) , including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand-six English-speaking nations with India and China, two populous countries. For each country, we chose media outlets that were the most active during February-April 2022, with media activity measured by the quantity of news reports. We then generated embedding representations for each media outlet via Truncated SVD and performed K-means clustering (Lloyd, 1982 ; MacQueen, 1967 ) on the obtained media embedding representations (with K = 10) for further analysis. Details of the experiment are presented in the first section of the supplementary Information. Figure 2 visualizes the clustering results.

There are 247 media outlets from 8 countries: Canada (CA), Ireland (IE), United Kingdom (UK), China (CN), United States (US), India (IN), Australia (AU), and New Zealand (NZ). Each circle in the visualization represents a media outlet, with its color indicating the cluster it belongs to, and its diameter proportional to the number of events reported by the outlet between February and April 2022. The text in each circle represents the name or abbreviation of a media outlet (See Supplementary Information Tab. S6 for details). The results indicate that media outlets from the same country tend to be grouped together in clusters. Moreover, the majority of media outlets in the Fox series form a distinct cluster, indicating a high degree of similarity in their event selection bias.

First, we find that media outlets from different countries tend to form distinct clusters, signifying the regional nature of media bias. Specifically, we can interpret Fig. 2 from two different perspectives, and both come to this conclusion. On the one hand, most media outlets from the same country tend to appear in a limited number of clusters, which suggests that they share similar event selection bias. On the other hand, as we can see, media outlets in the same cluster mostly come from the same country, indicating that media exhibiting similar event selection bias tends to be from the same country. In our view, differences in geographical location lead to diverse initial event information accessibility for media outlets from different regions, thus shaping the content they choose to report.

Besides, we observe an intriguing pattern where the Associated Press (AP) and Reuters, despite their geographical separation, share similar event selection biases as they are clustered together. This abnormal phenomenon could be attributed to their status as international media outlets, which enables them to cover various global events, thus leading to extensive overlapping news coverage. In addition, 16 out of the 21 Fox series media outlets form a distinct cluster on their own, suggesting that a media outlet’s bias is strongly associated with the organization it belongs to. After all, media outlets within the same organization often tend to prioritize or overlook specific events due to shared positions, interests, and other influencing factors.

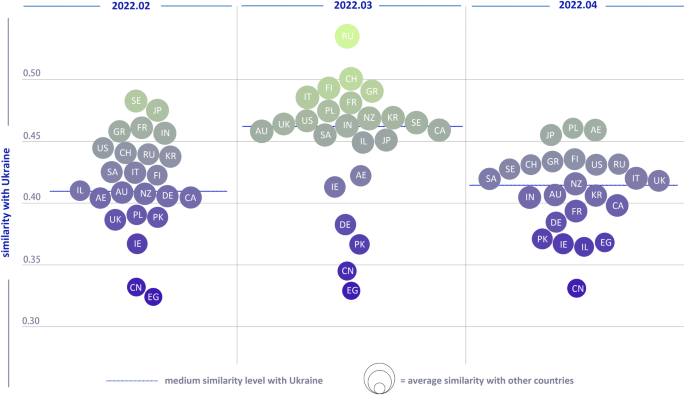

International hot topics drive media bias to converge

Previous results have revealed a significant correlation between media bias and the location of a media outlet. Therefore, we conducted an experiment to further investigate the event selection biases of media outlets from 25 different countries. To achieve this, we gathered GDELT data spanning from February to April 2022 and created three “media-event” matrices on a monthly basis. We then subjected each month’s “media-event” matrix to the same processing steps: (1) generating an embedding representation for each media outlet through matrix decomposition, (2) obtaining the embedding representation of each media outlet that belongs to each country to construct a media embedding set, and (3) calculating the similarity between every two countries (i.e., each two media embedding sets) using Word Mover Distance (WMD (Kusner et al. 2015 )) as the similarity metric (See Methods for details). Figure 3 presents the changes in event selection bias similarity amongst media outlets from different countries between February and April 2022.

The horizontal axis in this figure represents the time axis, measured in months. Meanwhile, the vertical axis indicates the event selection similarity between Ukrainian media and media from other countries. Each circle represents a country, with the font inside it representing the corresponding country’s abbreviation (see details in Supplementary Information Tab. S3) . The size of a circle corresponds to the average event selection similarity between the media of a specific country and the media of all other countries. The color of the circle corresponds to the vertical axis scale. The blue dotted line’s ordinate represents the median similarity to Ukrainian media.

We find that the similarities between Ukraine and other countries peaked significantly in March 2022. This result aligns with the timeline of the Russia-Ukraine conflict: the conflict broke out around February 22, attracting media attention worldwide. In March, the conflict escalated, and the regional situation became increasingly tense, leading to even more media coverage worldwide. By April, the prolonged conflict had made the international media accustomed to it, resulting in a decline in media interest. Furthermore, we observed that the event selection biases of media outlets in both EG (Egypt) and CN (China) differed significantly from those of other countries. Given that both countries are not predominantly English-speaking, their English-language media outlets may have specific objectives such as promoting their national image and culture, which could influence and constrain the topics that a media outlet tends to cover.

Additionally, we observe that in March 2022, the country with the highest similarity to Ukraine was Russia, and in April, it was Poland. This change can be attributed to the evolving regional situation. In March, when the conflict broke out, media reports primarily focused on the warring parties, namely Russia and Ukraine. As the war continued, the impact of the war on Ukraine gradually became the focus of media coverage. For instance, the war led to the migration of a large number of Ukrainian citizens to nearby countries, among which Poland received the most citizens of Ukraine at that time.

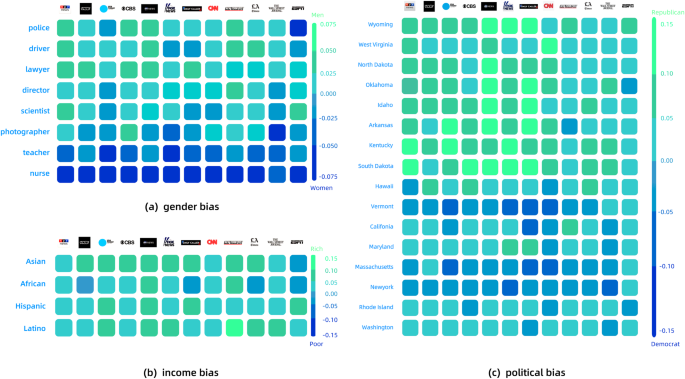

Media shows diverse biases on different topics

In this experiment, we took 12 mainstream US news outlets as examples and conducted a quantitative media bias analysis on three typical topics (Fan and Gardent, 2022 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ; Sun and Peng, 2021 ): Gender bias (about occupation); Political bias (about the American state); Income bias (about race & ethnicity). The topic words for each topic are listed in Supplementary Information Tab. S4 . These topic words are sourced from related literature (Caliskan et al. 2017 ), and search engines, along with the authors’ intuitive assessments.

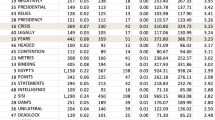

Gender bias in terms of Occupation

In news coverage, media outlets may intentionally or unintentionally associate an occupation with a particular gender (e.g., stereotypes like police-man, nurse-woman). Such gender bias can subtly affect people’s attitudes towards different occupations and even impact employment fairness. To analyze gender biases in news coverage towards 8 common occupations (note that more occupations can be studied using the same methodology), we examined 12 mainstream US media outlets. As shown in Fig. 4 a, all these outlets tend to associate “teacher” and “nurse” with women. In contrast, when reporting on “police,” “driver,” “lawyer,” and “scientist,” most outlets show bias towards men. As for “director” and “photographer,” only slightly more than half of the outlets show bias towards men. Supplementary Information Tab. S5 shows the proportion of women in the eight occupations in America according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Footnote 7 . Women’s proportions in “teacher” and “nurse” dominate, while men’s in “police,” “driver,” and “lawyer” are significantly higher. Besides, among “directors,” “scientists,” and “photographers,” the proportions of women and men are about the same. Comparing the experiment results with USCB’s statistics, we find that these media outlets’ gender bias towards an occupation is highly consistent with the actual women (or men) ratio in the occupation. Such a phenomenon highlights the potential for media outlets to perpetuate and reinforce existing gender bias in society, emphasizing the need for increased awareness and attention to media bias. Note that we reorganized the corpus of each media outlet by up-sampling during the data preprocessing process, which introduced some randomness to the experiment results (See Methods for details). Therefore, we set five different random seeds for up-sampling and repeated the experiment mentioned above five times. A two-tailed t-test on the difference between the results shown in Fig. 4 a and the results of current repeated experiments showed no significant difference ( Supplementary Information Fig. S6) .

Each column corresponds to a media outlet, and each row corresponds to a target word which usually means an entity or concept in the news text. The color bar on the right describes the value range of the bias value, with each interval of the bias value corresponding to a different color. As the bias value changes from negative to positive, the corresponding color changes from purple to yellow. Because the range of bias values differs across each topic, the color bar of different topics can also vary. The color of each heatmap square corresponds to an interval in the color bar. Specifically, the square located in row i and column j represents the bias of media j when reporting on target i. a Gender bias about eight common occupations. b Income bias about four races or ethnicities. c Political bias about the top-10 “red state” (Wyoming, West Virginia, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Idaho, Arkansas, Kentucky, South Dakota, Alabama, Texas) and the top-10 “blue state” (Hawaii, Vermont, California, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Washington, Connecticut, Illinois) according to the CPVI ranking (Ardehaly and Culotta, 2017 ). Limited by the page layout, only the top-8 results are shown here. Please refer to Supplementary Information Fig. S5 for the complete results.

Income bias in terms of Race and Ethnicity

Media coverage often discusses the income of different groups of people, including many races and ethnicities. Here, we aim to investigate whether the media outlets are biased in their income coverage, such as associating a specific race or ethnicity with rich or poor. To this end, we selected four US racial and ethnic groups as research subjects: Asian, African, Hispanic, and Latino. In line with previous studies (Grieco and Cassidy, 2015 ; Nerenz et al. 2009 ; Perez and Hirschman, 2009 ), we considered Asian and African as racial categories and Hispanic and Latino as ethnic categories. Referring to the income statistics from USCB Footnote 8 , we do not strictly distinguish these concepts and compare them together. As shown in Fig. 4 b, for the majority of media outlets, Asian is most frequently associated with the rich, with ESPN being the only exception. This anomalous finding may be attributed to ESPN’s position as a sports media, with a primary emphasis on sports that are particularly popular with Hispanic, Latino, and African-American audiences, such as soccer, basketball, and golf. Additionally, there is a significant disparity in the media’s coverage of income bias toward Africans, Hispanics, and Latinos. Specifically, the biases towards Hispanic and Latino populations are generally comparable, with both groups being portrayed as richer than African Americans in most media coverage. Referring to the aforementioned income statistics of the U.S. population, the income rankings of different races and ethnicities have remained stable from 1950 to 2020: Asians have consistently had the highest income, followed by Hispanics with the second-highest income, and African Americans with the lowest income (the income of Black Americans is used as an approximation for African Americans). It is worth noting that USCB considers Hispanic and Latino to be the same ethnicity, although there are some controversies surrounding this practice (Mora, 2014 ; Rodriguez, 2000 ). However, these controversies are not the concern of this work, so we use Hispanic income as an approximation of Latino income following USCB. Comparing our experiment results with USCB’s income statistics, we find that the media outlets’ income bias towards different races and ethnicities is roughly consistent with their actual income levels. A two-tailed t-test on the difference between the results shown in Fig. 4 b and the results of repeated experiments showed no significant difference ( Supplementary Information Fig. S7) .

Political bias in terms of Region

Numerous studies have shown that media outlets tend to publish politically biased news articles that support the political parties they favor while criticizing those they oppose (Lazaridou et al. 2020 ; Puglisi, 2011 ). For example, a report from the Red State described liberals as regressive leftists with mental health issues. Conversely, a story from Right Wing News reported that Obama’s administration was terrible (Lazaridou et al. 2020 ). Such political inclinations will hinder readers’ objective judgment of political events and affect their attitudes toward different political parties. Therefore, we analyzed the political biases of 12 mainstream US media outlets when talking about different US states, aiming to increase public awareness of such biases in news coverage. As shown in Fig. 4 c, in the reports of these media outlets, most red states lean Republican, while most blue states lean Democrat. In particular, some blue states also show a leaning toward Republicans, such as Hawaii and Maryland. Such an abnormal phenomenon can be attributed to the source of the corpus data used in this study. The corpus data, which was used to train word embedding models, spans from January 2016 to December 2021. During this period, the Republican Party was in power, with Trump serving as president from January 2017 to January 2021. Thus, the majority of the data was collected during the Republican administration. We suggest that Trump’s presidency resulted in increased media coverage of the Republican Party, thus causing some blue states to be associated more frequently with Republicans in news reports. A two-tailed t-test on the difference between the results shown in Fig. 4 c and the results of repeated experiments showed no significant difference ( Supplementary Information Fig. S8 and Fig. S9) .

Media logic and news evaluation are two important concepts in social science. The former refers to the rules, conventions, and strategies that the media follow in the production, dissemination, and reception of information, reflecting the media’s organizational structure, commercial interests, and socio-cultural background (Altheide, 2015 ). The latter refers to the systematic analysis of the quality, effectiveness, and impact of news reports, involving multiple criteria and dimensions such as truthfulness, accuracy, fairness, balance, objectivity, diversity, etc. When studying media bias issues, media logic provides a framework for understanding the rules and patterns of media operations, while news evaluation helps identify and analyze potential biases in media reports. For example, to study media’s political bias, (D’heer, 2018 ; Esser and Strömbäck, 2014 ) compare the frameworks, languages, and perspectives used by traditional news media and social media in reporting political elections, so as to understand the impact of these differences on voters’ attitudes and behaviors. However, in spite of the progress, these methods often rely on manual observation and interpretation, thus inefficient and susceptible to human bias and errors.

In this work, we propose an automated media bias analysis framework that enables us to uncover media bias on a large scale. To carry out this study, we amassed an extensive dataset, comprising over 8 million event records and 1.2 million news articles from a diverse range of media outlets (see details of the data collection process in Methods). Our research delves into media bias from two distinct yet highly pertinent perspectives. From the macro perspective, we aim to uncover the event selection bias of each media outlet, i.e., which types of events a media outlet tends to report on. From the micro perspective, our goal is to quantify the bias of each media outlet in wording and sentence construction when composing news articles about the selected events. The experimental results align well with our existing knowledge and relevant statistical data, indicating the effectiveness of embedding methods in capturing the characteristics of media bias. The methodology we employed is unified and intuitive and follows a basic idea. First, we train embedding models using real-world data to capture and encode media bias. At this step, based on the characteristics of different types of media bias, we choose appropriate embedding methods to model them respectively (Deerwester et al. 1990 ; Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ). Then, we utilize various methods, including cluster analysis (Lloyd, 1982 ; MacQueen, 1967 ), similarity calculation (Kusner et al. 2015 ), and semantic differential (Osgood et al. 1957 ), to extract media bias information from the obtained embedding models.

To capture the event selection biases of different media outlets, we employ Truncated SVD (Halko et al. 2011 ) on the “media-event” matrix to generate media embeddings. Truncated SVD is a widely used technique in NLP. In particular, LSA (Deerwester et al. 1990 ) applies Truncated SVD to the “document-word” matrix to capture the underlying topic-based semantic relationships between text documents and words. LSA assumes that a document tends to use relevant words when it talks about a particular topic and obtains the vector representation for each document in a latent topic space, where documents talking about similar topics are located near each other. By analogizing media outlets and events with documents and words, we can naturally apply Truncate SVD to explore media bias in the event selection process. Specifically, we assume that there are underlying topics when considering a media outlet’s event selection bias. If a media focuses on a topic, it will tend to report events related to that topic and otherwise ignore them. Therefore, media outlets sharing similar event selection biases (i.e., tend to report events about similar topics) will be close to each other in the latent topic space, which provides a good opportunity for us to study media bias (See Methods and Results for details).

When describing something, relevant contexts must be considered. For instance, positive and negative impressions are conveyed through the use of context words such as “diligent” and “lazy”, respectively. Similarly, a media outlet’s attitude towards something is reflected in the news context in which it is presented. Here, we study the association between each target and its news contexts based on the co-occurrence relationship between words. Our underlying assumption is that frequently co-occurring words are strongly associated, which aligns with the idea of word embedding models (Kenton and Toutanova, 2019 ; Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ), where the embeddings of frequently co-occurring words are relatively similar. For example, suppose that in the corpus of media M, the word “scientist” often co-occurs with female-related words (e.g., “woman” and “she”, etc.) but rarely with those male-related words. Then, the semantic similarities of “scientist” with female-related words should be much higher than those of male-related words in the word embedding model. Therefore, we can conclude that media M’s reports on scientists are biased towards women.

According to the theory of Semantic Differential (Osgood et al. 1957 ), the difference in semantic similarities between “scientist” and female-related words versus male-related words can serve as an estimation of media M’s gender bias. Since we have kept all settings (e.g., corpus size, starting point for model fine-tuning, etc.) the same when training word embedding models for different media outlets, the estimated bias values can be interpreted as absolute ones within the same reference system. In other words, the estimated bias values for different media outlets are directly comparable in this study, with a value of 0 denoting unbiased and a value closer to 1 or -1 indicating a more pronounced bias.

We notice that there has been literature investigating the choice of events/topics and words/frames to measure media bias, such as partisan and ideological biases (Gentzkow et al. 2015 ; Puglisi and Snyder Jr, 2015b ). However, our approach not only considers bias related to the selective reporting of events (using event embedding) but also studies biased wording in news texts (using word embedding). While the former focuses on the macro level, the latter examines the micro level. These two perspectives are distinct yet highly relevant, but previous studies often only consider one of them. For the choice of events/topics, our approach allows us to explore how they change over time. For example, we can analyze the time-changing similarities between media outlets from different countries, as shown in Fig. 3 . For the choice of words/frames, prior work has either analyzed specific biases based on the frequency of particular words (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010 ; Gentzkow et al. 2006 ), which fails to capture deeper semantics in media language or analyzed specific biases by merely aggregating the analysis results for every single article in the corpus (e.g., calculating the sentiment (Gentzkow et al. 2006 ; Lott Jr and Hassett, 2014 ; Soroka, 2012 ) of each article or its similarity with certain authorship (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2010 ; Groseclose and Milyo, 2005 ), then summing them up as the final bias value), without considering the relationships between different articles, thus lacking a holistic nature. In contrast, our method, based on word embeddings (Le and Mikolov, 2014 ; Mikolov et al. 2013 ), directly models the semantic associations between all words and entities in the corpus with a neural network, offering advantages in capturing both semantic meaning and holistic nature. Specially, we not only utilize word embedding techniques but also integrate them with appropriate psychological/sociological theories, such as the Semantic Differential theory and the Cognitive Miser theory. These theories endow our approach with better interpretability. In addition, the method we propose is a generalizable framework for studying media bias using embedding techniques. While this study has focused on validating its effectiveness with specific types of media bias, it can actually be applied to a broader range of media bias research. We will expand the application of this framework in future work.

As mentioned above, our proposed framework examines media bias from two distinct but highly relevant perspectives. Here, taking the significant Russia-Ukraine conflict event as an example, we will demonstrate how these two perspectives contribute to providing researchers and the public with a more comprehensive and objective assessment of media bias. For instance, we can gather relevant news articles and event reporting records about the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict from various media outlets worldwide and generate media and word embedding models. Then, according to the embedding similarities of different media outlets, we can judge which types of events each media outlet tends to report and select some media that tend to report on different events. By synthesizing the news reports of the selected media, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the conflict instead of being limited to the information selectively provided by a few media. Besides, based on the word embedding model and the bias estimation method based on Semantic Differential, we can objectively judge each media’s attitude towards Russia and Ukraine (e.g., whether a media tends to use positive or negative words to describe either party). Once a news outlet is detected as apparently biased, we should read its articles more carefully to avoid being misled.

In the end, despite the advantages of our framework, there are still some shortcomings that need improvement. First, while the media embeddings generated based on matrix decomposition have successfully captured media bias in the event selection process, interpreting these continuous numerical vectors directly can be challenging. We hope that future work will enable the media embedding to directly explain what a topic exactly means and which topics a media outlet is most interested in, thus helping us understand media bias better. Second, since there is no absolute, independent ground truth on which events have occurred and should have been covered, the aforementioned media selection bias, strictly speaking, should be understood as relative topic coverage, which is a narrower notion. Third, for topics involving more complex semantic relationships, estimating media bias using scales based on antonym pairs and the Semantic Differential theory may not be feasible, which needs further investigation in the future.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://github.com/CGCL-codes/media-bias .

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is also available at https://github.com/CGCL-codes/media-bias .

https://fair.org/home/when-both-sides-are-covered-in-verizon-strike-bosses-side-is-heard-more/ .

These views were extracted from reports by some mainstream US media outlets in 2022 when the Democratic Party (left-wing) was in power.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/26/world/middleeast/women-iran-protests-hijab.html .

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/08/world/asia/uighurs-veils-a-protest-against-chinas-curbs.html .

https://www.gdeltproject.org/ .

https://mediacloud.org/ .

https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm .

https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.pdf .

Altheide, DL (2015) Media logic. The international encyclopedia of political communication, pages 1–6

Ansolabehere S, Lessem R, Snyder Jr JM (2006) The orientation of newspaper endorsements in us elections, 1940–2002. Quarterly Journal of political science 1(4):393

Article Google Scholar

Ardehaly, EM, Culotta, A (2017) Mining the demographics of political sentiment from twitter using learning from label proportions. In 2017 IEEE international conference on data mining (ICDM), pages 733–738. IEEE

Baron DP (2006) Persistent media bias. Journal of Public Economics 90(1-2):1–36

Article ADS Google Scholar

Bovet A, Makse HA (2019) Influence of fake news in twitter during the 2016 us presidential election. Nature communications 10(1):1–14

Caliskan A, Bryson JJ, Narayanan A (2017) Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science 356(6334):183–186

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

D’Alessio D, Allen M (2000) Media bias in presidential elections: A meta-analysis. Journal of communication 50(4):133–156

Deerwester S, Dumais ST, Furnas GW, Landauer TK, Harshman R (1990) Indexing by latent semantic analysis. Journal of the American society for information science 41(6):391–407

DellaVigna S, Kaplan E (2008) The political impact of media bias. Information and Public Choice, page 79

Downs A (1957) An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of political economy 65(2):135–150

D’heer E (2018) Media logic revisited. the concept of social media logic as alternative framework to study politicians’ usage of social media during election times. Media logic (s) revisited: Modelling the interplay between media institutions, media technology and societal change, pages 173–194

Esser F, Strömbäck J (2014) Mediatization of politics: Understanding the transformation of Western democracies. Springer

Fan A, Gardent, C (2022) Generating biographies on Wikipedia: The impact of gender bias on the retrieval-based generation of women biographies. In Proceedings of the Conference of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL)

Firth, JR (1957) A synopsis of linguistic theory, 1930–1955. Studies in linguistic analysis

Fiske ST, Taylor SE (1991) Social cognition. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company

Galtung J, Ruge MariHolmboe (1965) The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the congo, cuba and cyprus crises in four norwegian newspapers. Journal of peace research 2(1):64–90

Gentzkow M, Shapiro JM (2010) What drives media slant? evidence from us daily newspapers. Econometrica 78(1):35–71

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Gentzkow M, Glaeser EL, Goldin C (2006) The rise of the fourth estate. how newspapers became informative and why it mattered. In Corruption and reform: Lessons from America’s economic history, pages 187–230. University of Chicago Press

Gentzkow M, Shapiro JM, Stone DF (2015) Media bias in the marketplace: Theory. In Handbook of Media Economics, volume 1, pages 623–645. Elsevier

Grand G, Blank IdanAsher, Pereira F, Fedorenko E (2022) Semantic projection recovers rich human knowledge of multiple object features from word embeddings. Nature Human Behaviour 6(7):975–987

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grieco EM, Cassidy RC (2015) Overview of race and hispanic origin: Census 2000 brief. In ’Mixed Race’Studies, pages 225–243. Routledge

Groseclose T, Milyo J (2005) A measure of media bias. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120(4):1191–1237

Grossmann, Matt and Hopkins, David A (2016) Asymmetric politics: Ideological Republicans and group interest Democrats . Oxford University Press

Halko N, Martinsson Per-Gunnar, Tropp JA (2011) Finding structure with randomness: Probabilistic algorithms for constructing approximate matrix decompositions. SIAM review 53(2):217–288

Hamborg F, Donnay K, Gipp B (2019) Automated identification of media bias in news articles: an interdisciplinary literature review. International Journal on Digital Libraries 20(4):391–415

Haraldsson A, Wängnerud L (2019) The effect of media sexism on women’s political ambition: evidence from a worldwide study. Feminist media studies 19(4):525–541

Harcup T, O’neill D (2001) What is news? galtung and ruge revisited. Journalism studies 2(2):261–280

Harcup T, O’neill D (2017) What is news? news values revisited (again). Journalism studies 18(12):1470–1488

Harris ZS (1954) Distributional structure. Word 10(2-3):146–162

Harwood TG, Garry T (2003) An overview of content analysis. The marketing review 3(4):479–498

Ho DE, Quinn KM et al. (2008) Measuring explicit political positions of media. Quarterly Journal of Political Science 3(4):353–377

Huang H, Chen Z, Shi X, Wang C, He Z, Jin H, Zhang M, Li Z (2021) China in the eyes of news media: a case study under covid-19 epidemic. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 22(11):1443–1457

Huang P-S, Zhang H, Jiang R, Stanforth R, Welbl J, Rae J, Maini V, Yogatama D, Kohli P (2020) Reducing sentiment bias in language models via counterfactual evaluation. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 65–83

Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT, pages 4171–4186, (2019)

Kusner M, Sun Y, Kolkin N, Weinberger K. From word embeddings to document distances. In International conference on machine learning, pages 957–966. PMLR, (2015)

Larcinese V, Puglisi R, Snyder Jr JM (2011) Partisan bias in economic news: Evidence on the agenda-setting behavior of us newspapers. Journal of public Economics 95(9–10):1178–1189

Lazaridou K, Löser A, Mestre M, Naumann F (2020) Discovering biased news articles leveraging multiple human annotations. In Proceedings of the 12th Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages 1268–1277

Le, Q, Mikolov, T (2014) Distributed representations of sentences and documents. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1188–1196. PMLR

Liu, R, Jia, C, Wei, J, Xu, G, Wang, L, Vosoughi, S (2021) Mitigating political bias in language models through reinforced calibration. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 35, pages 14857–14866

Liu R, Wang L, Jia, C, Vosoughi, S (2021) Political depolarization of news articles using attribute-aware word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 15th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2021)

Lloyd S (1982) Least squares quantization in pcm. IEEE transactions on information theory 28(2):129–137

Lott Jr JR, Hassett KA (2014) Is newspaper coverage of economic events politically biased? Public Choice 160(1–2):65–108

Lühiste M, Banducci S (2016) Invisible women? comparing candidates’ news coverage in Europe. Politics & Gender 12(2):223–253

MacGregor, B (1997) Live, direct and biased?: Making television news in the satellite age

MacQueen, J (1967) Classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In 5th Berkeley Symp. Math. Statist. Probability, pages 281–297

Merloe P (2015) Authoritarianism goes global: Election monitoring vs. disinformation. Journal of Democracy 26(3):79–93

Mikolov T, Chen K, Corrado GS, Dean J (2013) Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. In International Conference on Learning Representations

Mora, GC (2014) Making Hispanics: How activists, bureaucrats, and media constructed a new American. University of Chicago Press

Nerenz DR, McFadden B, Ulmer C et al. (2009) Race, ethnicity, and language data: standardization for health care quality improvement

Niven, David (2002). Tilt?: The search for media bias. Greenwood Publishing Group

Osgood, Charles Egerton, Suci, George J and Tannenbaum, Percy H (1957) The measurement of meaning. Number 47. University of Illinois Press

Papacharissi Z, de Fatima Oliveira M (2008) News frames terrorism: A comparative analysis of frames employed in terrorism coverage in US and UK newspapers. The international journal of press/politics 13(1):52–74

Park S, Kang S, Chung, S, Song, J (2009) Newscube: delivering multiple aspects of news to mitigate media bias. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, pages 443–452

Paul R, Elder L (2004) The thinkers guide for conscientious citizens on how to detect media bias & propaganda in national and world news: Based on critical thinking concepts & tools

Perez AnthonyDaniel, Hirschman C (2009) The changing racial and ethnic composition of the US population: Emerging American identities. Population and development review 35(1):1–51

Puglisi, R (2011) Being the New York times: the political behaviour of a newspaper. The BE journal of economic analysis & policy 11(1)

Puglisi R, Snyder Jr JM (2015a) The balanced US press. Journal of the European Economic Association 13(2):240–264

Puglisi, Riccardo and Snyder Jr, James M (2015b) Empirical studies of media bias. In Handbook of media economics, volume 1, pages 647–667. Elsevier

Qiang J, Zhang F, Li Y, Yuan Y, Zhu Y, Wu X (2023) Unsupervised statistical text simplification using pre-trained language modeling for initialization. Frontiers of Computer Science 17(1):171303

Rodriguez, CE (2000) Changing race: Latinos, the census, and the history of ethnicity in the United States, volume 41. NYU Press

Ross K, Carter C (2011) Women and news: A long and winding road. Media, Culture & Society 33(8):1148–1165

Sahlgren M (2008) The distributional hypothesis. Italian Journal of Disability Studies 20:33–53

Google Scholar

Soroka SN (2012) The gatekeeping function: distributions of information in media and the real world. The Journal of Politics 74(2):514–528

Stanovich KE (2009) What intelligence tests miss: The psychology of rational thought. Yale University Press

Stroud NatalieJomini (2010) Polarization and partisan selective exposure. Journal of Communication 60(3):556–576

Sun J, Peng N (2021) Men are elected, women are married: Events gender bias on wikipedia. In Proceedings of the Conference of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL)

Sunstein C (2002) The law of group polarization. Journal of Political Philosophy 10:175–195

Tahmasbi F, Schild L, Ling C, Blackburn J, Stringhini G, Zhang Y, Zannettou S (2021) “go eat a bat, chang!”: On the emergence of sinophobic behavior on web communities in the face of covid-19. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, pages 1122–1133

Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T (2013) Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & health sciences 15(3):398–405

Wang T, Lin XV, Rajani NF, McCann B, Ordonez V, Xiong, C (2020). Double-hard debias: Tailoring word embeddings for gender bias mitigation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 5443–5453

White DavidManning (1950) The “gate keeper”: a case study in the selection of news. Journalism Quarterly 27(4):383–390

Zeng Y, Li Z, Chen Z, Ma H (2023) Aspect-level sentiment analysis based on semantic heterogeneous graph convolutional network. Frontiers of Computer Science 17(6):176340

Zhang Y, Wang H, Yin G, Wang T, Yu Y (2017) Social media in github: the role of@-mention in assisting software development. Science China Information Sciences 60(3):1–18

Download references

Acknowledgements

The work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62127808).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

National Engineering Research Center for Big Data Technology and System, Wuhan, China

Hong Huang, Hua Zhu & Hai Jin

Services Computing Technology and System Lab, Wuhan, China

Cluster and Grid Computing Lab, Wuhan, China

School of Computer Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Hong Huang, Hua Zhu, Wenshi Liu & Hai Jin

Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Hong Huang, Hua Zhu, Wenshi Liu, Hua Gao & Hai Jin

DIRO, Université de Montréal & Mila & Canada CIFAR AI Chair, Montreal, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HH: conceptualization, writing-review & editing, supervision; HZ: software, writing-original draft, data curation; WSL: software; HG and HJ: resources; BL: methodology, writing-review & editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hong Huang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required as the study does not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary material, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Huang, H., Zhu, H., Liu, W. et al. Uncovering the essence of diverse media biases from the semantic embedding space. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11 , 656 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03143-w

Download citation

Received : 26 February 2023

Accepted : 07 May 2024

Published : 22 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03143-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Resources & Publications

All members of the network can share their recent work on media bias here.

Most recent models are published on Huggingface

[Benchmark, GitHub] MBIB – the first Media Bias Identification Benchmark Task and Dataset Collection

[Dataset, GitHub] BABE – Bias Annotations By Experts

[Scale/Questionnaire to measure bias perception] Do You Think It’s Biased? How To Ask For The Perception Of Media Bias (A set of tested questions to assess media bias perception to be used in any bias-related research)

[Dataset, Zenodo] MBIC -A Media Bias Annotation Dataset Including Annotator Characteristics

Publications

Hinterreiter, Smi; Wessel, Martin; Schliski, Fabian; Echizen, Isao; Latoschik, Marc Erich; Spinde, Timo

NewsUnfold: Creating a News-Reading Application That Indicates Linguistic Media Bias and Collects Feedback Proceedings Article Forthcoming

In: Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM'25), AAAI, Copenhagen, Denmark, Forthcoming , (Conditionally accepted for publication) .

Abstract | Links | BibTeX | Tags: crowdsourcing , HITL , linguistic bias , media bias , news bias

- https://media-bias-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Preprint_ICWSM_25_New[...]

Hinterreiter, Smi; Spinde, Timo; Oberdörfer, Sebastian; Echizen, Isao; Latoschik, Marc Erich

News Ninja: Gamified Annotation of Linguistic Bias in Online News Journal Article Forthcoming

In: Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact., vol. 8, no. CHI PLAY, Forthcoming , (Publisher: Association for Computing Machinery. Conditionally accepted for publication) .

Abstract | Links | BibTeX | Tags: crowdsourcing , Game With A Purpose , linguistic bias , media bias , news bias

- https://media-bias-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Preprint_News_Ninja.p[...]

- doi:10.1145/3677092

Wessel, Martin; Horych, Tomas

Beyond the Surface: Spurious Cues in Automatic Media Bias Detection Proceedings Article

In: Bharathi B Bharathi Raja Chakravarthi, Paul Buitelaar (Ed.): Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity, Inclusion, pp. 21–30, Association for Computational Linguistics, 2024 .

Abstract | Links | BibTeX | Tags:

- https://aclanthology.org/2024.ltedi-1.3

Horych, Tomas; Wessel, Martin; Wahle, Jan Philip; Ruas, Terry; Wassmuth, Jerome; Greiner-Petter, Andre; Aizawa, Akiko; Gipp, Bela; Spinde, Timo

MAGPIE: Multi-Task Analysis of Media-Bias Generalization with Pre-Trained Identification of Expressions Proceedings Article

In: "Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation", 2024 .

Abstract | Links | BibTeX | Tags: dataset , multi-task learning , Transfer learning

- https://aclanthology.org/2024.lrec-main.952

Wessel, Martin; Horych, Tomas; Ruas, Terry; Aizawa, Akiko; Gipp, Bela; Spinde, Timo

Introducing MBIB - the first Media Bias Identification Benchmark Task and Dataset Collection Proceedings Article

In: Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR ’23), ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2023 , ISBN: 978-1-4503-9408-6/23/07 .

- https://media-bias-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Wessel2023Preprint.pdf

- doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3539618.3591882

Spinde, Timo; Richter, Elisabeth; Wessel, Martin; Kulshrestha, Juhi; Donnay, Karsten

What do Twitter comments tell about news article bias? Assessing the impact of news article bias on its perception on Twitter Journal Article

In: Online Social Networks and Media, vol. 37-38, pp. 100264, 2023 , ISSN: 2468-6964 .

Abstract | Links | BibTeX | Tags: Hate speech detection , media bias , Sentiment analysis , Transfer learning

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S246869642300023X

- doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.osnem.2023.100264

Spinde, Timo; Hinterreiter, Smi; Haak, Fabian; Ruas, Terry; Giese, Helge; Meuschke, Norman; Gipp, Bela

The Media Bias Taxonomy: A Systematic Literature Review on the Forms and Automated Detection of Media Bias Journal Article

In: arXiv preprint, 2023 .

Links | BibTeX | Tags:

- https://media-bias-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/spinde2023.pdf

Krieger, David; Spinde, Timo; Ruas, Terry; Kulshrestha, Juhi; Gipp, Bela

A Domain-adaptive Pre-training Approach for Language Bias Detection in News Proceedings Article

In: 2022 ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL), Cologne, Germany, 2022 .

- https://media-bias-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Krieger2022_mbg.pdf

- doi:10.1145/3529372.3530932

Zhukova, Anastasia; Hamborg, Felix; Gipp, Bela

Towards Evaluation of Cross-document Coreference Resolution Models Using Datasets with Diverse Annotation Schemes Proceedings Article

In: Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, pp. 4884–4893, European Language Resources Association, Marseille, France, 2022 .

- https://aclanthology.org/2022.lrec-1.522

Spinde, Timo; Krieger, Jan-David; Ruas, Terry; Mitrović, Jelena; Götz-Hahn, Franz; Aizawa, Akiko; Gipp, Bela

Exploiting Transformer-based Multitask Learning for the Detection of Media Bias in News Articles Proceedings Article

In: Proceedings of the iConference 2022, Virtual event, 2022 .

- https://media-bias-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Spinde2022a_mbg.pdf

- doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96957-8_20

Spinde, Timo; Jeggle, Christin; Haupt, Magdalena; Gaissmaier, Wolfgang; Giese, Helge

How do we raise media bias awareness effectively? Effects of visualizations to communicate bias Journal Article

In: PLOS ONE, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 1-14, 2022 .

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266204

- doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0266204

Haak, Fabian; Schaer, Philipp

Auditing Search Query Suggestion Bias Through Recursive Algorithm Interrogation Proceedings Article

In: WebSci '22: 14th ACM Web Science Conference 2022, ACM, 2022 .

BibTeX | Tags: bias esupol haak myown schaer

Zhukova, Anastasia; Hamborg, Felix; Donnay, Karsten; Gipp, Bela

XCoref: Cross-Document Coreference Resolution in the Wild Proceedings Article

In: Information for a Better World: Shaping the Global Future: 17th International Conference, IConference 2022, Virtual Event, February 28 – March 4, 2022, Proceedings, Part I, pp. 272–291, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2022 , ISBN: 978-3-030-96956-1 .

Abstract | Links | BibTeX | Tags: Cross-document coreference resolution , media bias , news analysis

- https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96957-8_25

- doi:10.1007/978-3-030-96957-8_25

Spinde, Timo; Plank, Manuel; Krieger, Jan-David; Ruas, Terry; Gipp, Bela; Aizawa, Akiko

Neural Media Bias Detection Using Distant Supervision With BABE - Bias Annotations By Experts Proceedings Article