- DSpace@MIT Home

- MIT Libraries

- Doctoral Theses

Essays in banking and risk management

Other Contributors

Terms of use, description, date issued, collections.

Show Statistical Information

Risk Management in the Banking Sector

Introduction.

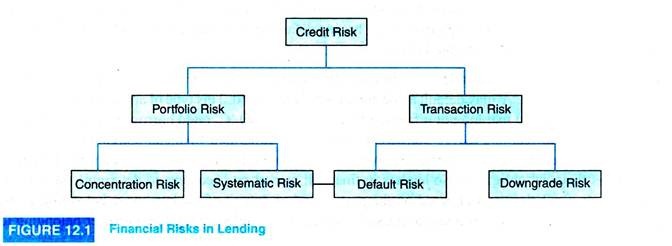

Like other businesses, Banks face multiple risks. However, due to the strategic importance of the banking sector to the economy and the government’s involvement in risk control, risk management in banking is heavier than in other industries. Understanding the real risk is critical to effective risk management. The main types of risks that banks face include credit risk, market risk, operational risk, reputational risk, and liquidity risk (Vyas & Singh, 2011). Understanding the specific risks facing a particular bank allows the management to apply various tools to effectively manage them. According to Kanchu & Kumar (2013), various models and tools are used to manage the different types of risks in the banking sector. For example, the Value at Risk Model and Stress Testing Model are widely used tools to minimize the impact of unfavorable events in the banking sector. However, each of these models has its own merits and drawbacks. This discussion analyzes the problems associated with the use of the Value at Risk Model and Stress Testing Model in managing risks in the banking sector. In addition, the discussion covers the problems associated with credit risk in measuring risk. The discussion further recommends the various ways of eliminating or reducing problems associated with the Value at Risk Model, Stress Testing Model, and Credit Risk.

Problems and Issues Associated with the Use of Value at Risk Model

By definition, the Value at Risk Model is a metric used to estimate the risk of an investment in the financial sector. According to Krause (2003), it is a statistical tool that measures the amount of potential loss that could occur over a specific period of time. The model specifically calculates the probability of losing more than a specified amount in a portfolio. This model is widely used by banks due to its simplicity. Although this model is a useful risk management metric particularly when applied appropriately, it is prone to significant measurement errors (Krause, 2003). Some of the main problems and issues associated with this model include difficulties in calculating risk for large portfolios, differences in approaches, the inability to measure worst-case loss, and giving a false sense of security (Berkowitz & O’Brien, 2002). In addition, the outcome of the Value at Risk Model is as good as the assumptions and inputs used.

Difficulties in Calculating for Large Portfolios

Calculating the Value at Risk of a portfolio not only requires the estimation of the return and volatility of individual securities but also the correlation coefficient between them (Krause, 2003). Given the growing demand for large and diversified portfolios, using the Value at Risk model to measure risk becomes extremely difficult. Thus, the higher the number of securities in a portfolio, the more difficult it is to estimate the Value at Risk.

Differences in Approaches

There are generally three methods of calculating Value at Risk of a portfolio. These methods include the historical approach, variance-covariance approach, and the Monte Carlo Simulation approach (Hendricks, 1996). Using these different methods to calculate Value at Risk of the same portfolio always leads to different results.

Inability to Measure Worst Case Loss

It is impossible to know the maximum possible loss by simply looking at the Value at Risk. For example, the worst-case loss may only be just a small percentage slightly higher than the Value at Risk, but it could be significant enough to affect the investment (Krause, 2003). Simply put, Value at Risk does not reveal anything about the maximum possible loss.

It Gives Some False Sense of Security

Using Value at Risk to assess risk exposure can be misleading. The vast majority consider Value at Risk to be the most they can lose, particularly when it is calculated with a confidence level of 99% (Berkowitz & O’Brien, 2002). The 1% loss can be so significant and this is what causes misunderstanding. The 99% confidence level in the Value at Risk model can consciously or unconsciously give people some false sense of security.

The Results are as Good as the Assumptions and Inputs Used

Like other quantitative techniques used in finance, the results of Value at Risk are as effective as the inputs and assumptions used (Berkowitz & O’Brien, 2002). For example, a common mistake when using the variance-covariance approach is the assumption of normal distribution for assets and returns from portfolios. Inputting unrealistic return distributions can result in the underestimation of risk.

Overall, Value at Risk is not always a good tool for risk measurement because it is vulnerable to significant measurement errors. However, it can be an effective risk management tool when applied properly with a clear understanding of its underlying assumptions.

Problems and Issues Associated with the Use of Stress Testing Model

The Stress Testing Model is a risk management tool that involves computer-generated and highly complicated simulation models that analyze the impacts of extreme scenarios (Stein, 2012). Simply put, the stress testing model analyzes how a financial institution’s balance sheet responds to certain situations. For instance, in times of financial uncertainties, banks and other financial institutions deploy stress testing models to study the market and analyze portfolio risk to help these institutions make an informed decision based on the results. These models rely on high-quality data to help organizations effectively identify potential risks and mitigate them. According to Basel II regulations, the purpose of stress testing in the banking sector is to establish whether a bank has sufficient capital and liquid assets to withstand stressful times (Stein, 2012). It is carried out for internal risk management as well as for regulatory purposes. UK, USA, and EU regulators, for instance, require banks to perform specific stress tests. Financial institutions are required to provide a capita plan justifying the models used as well as the results of their stress testing. If a bank does not meet the stress test requirements because of insufficient capital, then it must raise more capital by limiting the payment of dividends. Although stress tests are effective risk management tools, banks face various challenges when implementing stress testing models. According to Thun (2012), these challenges include determining how and what needs to be stressed, designing effective and meaningful scenarios, Gathering sufficient data, and communicating the results for action.

Determining How and What Needs to Be Stressed

Many banks experience problems with this initial step of determining what should be stressed. Instead of determining what to be stressed from a bank’s market and risk analysis perspective, many organizations align their efforts with market best practices or standard regulatory requirements (Thun, 2012). For example, over the last two decades, two main methods of stress testing have gained more appeal, including scenario analysis and sensitivity tests. Sensitivity tests are criticized because they assume that only a single factor like the shift in the yield curve change. Sensitivity tests, on the other hand, are easy and straightforward to execute but are criticized because they do not consider the interdependence between the risk factors.

Designing Meaningful and Effective Scenarios

A major challenge with stress testing models is designing meaningful and effective scenarios. Based on the scenario designed, the outcome of the stress test could significantly misrepresent the risks that a bank is actually exposed to (Battiston & Martinez-Jaramillo, 2018). The scenario may not be plausible or severe enough, thus it may not mitigate the bank against critical risks. Classic examples of this form of misrepresentation are the unforeseen problems that befell Franco-Belgian Bank in October 2011 and the sudden problems that the bank of Ireland faced in 2010 despite having passed stress tests outlined by the European Banking Authority regulators.

Gathering Sufficient Data

The greatest challenge that banks face is the lack of sufficient data. Specifically, data from periods of severe stress is not always available (Fell, 2006). Such information would be the basis for designing meaningful scenarios as well as understanding the link between risk drivers and macroeconomic variables. Given the relationship between various macroeconomic variables like inflation, GDP, oil prices, and GDP, gathering sufficient information allows banks to model behavior in times of stress (Fell, 2006). On the contrary, the lack of sufficient data about the macroeconomic variables leads to an unstable and weak relationship between the scenarios designed and the relevant risk factors.

Communicating the Results for Action

Efforts to design meaningful and effective stress tests are useless if communication, which is a critical aspect is missing. Internal communication, which should be in the format prescribed by the regulator is as important as external communication. For effectiveness, the stress test must be communicated clearly to everyone internally (Battiston & Martinez-Jaramillo, 2018). In addition, the stress test must be well understood, particularly by the senior managers. Furthermore, the stress tests must indicate the degree of risk exposure and the impact on the business.

Overall, even though much has been achieved over the last few decades in terms of designing an effective stress test framework, risk managers still face several challenges as mentioned above. These challenges must be addressed in order to turn stress testing models into powerful risk management tools.

Issues Associated with Credit Risk in Measuring Risks in Banking

With the recent global crisis, credit risk management remains a top priority for many banks and regulatory authorities. Although strict credit requirements like the top-down approach have been useful in mitigating economic risk, such approaches have left many financial organizations struggling to achieve effective credit risk assessment (Brown & Moles, 2014). In an attempt to implement a raft of risk strategies to improve overall performance and gain a competitive advantage, banks have to overcome a number of credit risk management challenges. According to Altman (2002), some of the main challenges associated with credit risk management include, ineffective data management, limited group-wide risk infrastructure, inefficient risk tools, and less-intuitive reporting.

Ineffective Data Management

Effective credit management requires an organization to securely gather data, analyze it, and store it securely based on a particular criterion. All databases need to be regularly updated to ensure easier retrieval as well as to avoid relying on outdated information in making decisions (Altman, 2002). Streamlining the manner in which data is gathered, analyzed, stored, and retrieved is critical to effective credit risk management. Data centralization is also important as it allows for easier analysis and modeling, which provides a clearer picture of a business or individual’s credit worthiness.

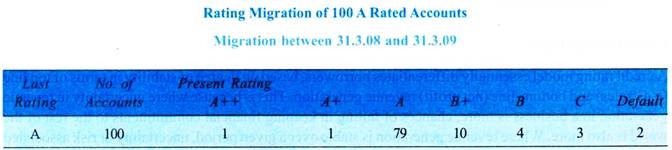

Limited Group-wide risk Infrastructure

Most often, it is not enough to evaluate the risk posed by a single individual or entity. A comprehensive and broader view of all risk measures is key to understanding the risk of a new borrower. In addition, having efficient stress testing models and capabilities is also important to ensure that an organization has an accurate assessment of risks (Cumming & Hirtle, 2001). Various rating agencies are also important as far as establishing credit scores for individuals is concerned. Banks can utilize a credit rating score system to determine default risk and make accurate credit decisions. Thus, having a 360-degree view of a financial organization’s risk that covers the entire group can create new opportunities for lending while maintaining risk at lower levels.

Insufficient Risk Tools

A broader and comprehensive scorecard should identify potential strengths and weaknesses linked to a loan. Risk analytics, for instance, took a step forward when financial institutions, particularly the bigger banks began embracing big data programs (Altman, 2002). However, small and medium banks experienced a slower adoption because of the huge investment required. With the modern risk tools being made available in the market, banks of all sizes will have access to big data in the near future. Risk analytics is considered a huge transformation that allows banks and other lending institutions to align their culture, governance, strategies, and technology in order to optimize risk management. Through optimization, banks can mitigate the risk management process, thus broadening their returns from lending.

Less-intuitive Reporting

In order to provide valuable insights, financial reports should be presented in a clear, clean, visualized, and intuitive manner. For example, eliminating irrelevant data from financial statements that only overburden analysts can help in narrowing down to the most pertinent information (Cumming & Hirtle, 2001). Using analytics requires a powerful reporting process that allows the bank to clearly visualize at the individual borrower level as well as across the organization. Thus, the lack of clear, clean, visualized, and intuitive reporting is a major hindrance to effective credit risk management.

Ways of Reducing or Eliminating Problems Raised in Part A

The various problems and issues associated with the use of the Value at Risk Model, Stress Testing Model, and credit risk can be minimized or eliminated through a range of ways as outlined below:

Addressing Issues Associated with Value at Risk Model

Despite its underlying limitations and problems, the Value at Risk Model can still be useful as long as the users understand its weaknesses. As a recommendation, Value at Risk should just be complemented with other risk management tools, particularly those that take into account the 1% worst-case that the Value at Risk Model ignores completely (Choudhry, 2011). Thus, banks should not allow the Value at Risk Model to become a false sense of security.

Addressing Issues Associated with Stress Testing Model

The results of stress testing can significantly affect the process of decision-making. For this reason, there is a need to benchmark stress test results against a bank’s appetite. Benchmarking allows a bank to review its underlying risk profile. The bank management has the responsibility of preparing strategic plans for early interventions. These strategic plans include raising more funds, suspending the payment of dividends to the shareholders, and eliminating or minimizing some business activities (Vyas & Singh, 2011). In addition, banks can ensure frequent reporting by incorporating in the company’s strategic planning the outcomes of hypothetical stress tests and scenarios, including those that are not likely to materialize.

Addressing Issues Associated with Credit Risk

The various challenges in using credit risk to evaluate risks in banking can be overcome through close monitoring, mitigation, creating relationships between different risks, and regular reporting. Mitigation involves reducing or minimizing the likelihood of uncertain events occurring (Kanchu & Kumar, 2013). Credit risk should be continually reviewed to ensure that the bank is adequately protected. Regular monitoring should be made a routine and a proactive process. Close monitoring allows banks to address emerging trends in order to establish whether or not progress is being made in mitigating credit risk. Furthermore, creating relationships between different risks, mitigation activities, and business units provide a cohesive picture of a bank (Kanchu & Kumar, 2013). These relationships help in the recognition of downstream and upstream dependencies, as well as the identification of other risks. Designing centralized controls further eliminates the probability of missing important pieces of information. Frequent reporting involves presenting regular updates regarding the way the risk management program is progressing. The information should be reported in a clear and engaging manner to attract the support of different stakeholders at the bank. Developing regular risk reports that give a dynamic view and centralize all information is step forward towards giving a broader view of the bank’s risk profile.

In summary, whether a bank is managing risks as defined by the UK, USA, EU, or other regulatory authorities, it is important to consider risk management as more than just a compliance requirement. The different risk models are designed to address the unique needs of every bank, as well as the dynamic needs of the banking industry. The Value at Risk Model and Stress Testing Model alone is not enough to sufficiently manage all risks a bank faces. To be effective, these models should be complemented with other risk management tools. In addition, understanding the weaknesses of each model helps the management to use every model selectively.

Altman, E. I. (2002). Managing credit risk: A challenge for the new millennium. Economic Notes , 31 (2), 201-214.

Battiston, S., & Martinez-Jaramillo, S. (2018). Financial networks and stress testing: Challenges and new research avenues for systemic risk analysis and financial stability implications. Journal of Financial Stability , 35 , 6-16.

Berkowitz, J., & O’Brien, J. (2002). How accurate are value‐at‐risk models at commercial banks?. The journal of finance , 57 (3), 1093-1111

Brown, K., & Moles, P. (2014). Credit risk management. K. Brown & P. Moles, Credit Risk Management , 16 .

Choudhry, M. (2011). An introduction to banking: liquidity risk and asset-liability management . John Wiley & Sons.

Cumming, C., & Hirtle, B. (2001). The challenges of risk management in diversified financial companies. Economic policy review , 7 (1).

Fell, J. (2006, November). Overview of stress testing methodologies: from micro to macro. In Powerpoint Presentation at the Korea Financial Supervisory Commission/Financial Supervisory Service-International Monetary Fund Seminar on Macroprudential Supervision Conference: Challenges for Financial Supervisors, Seoul, November (Vol. 7).

Hendricks, D. (1996). Evaluation of value-at-risk models using historical data. Economic policy review , 2 (1).

Kanchu, T., & Kumar, M. M. (2013). Risk management in banking sector–an empirical study. International journal of marketing, financial services & management research , 2 (2), 145-153.

Krause, A. (2003). Exploring the limitations of value at risk: how good is it in practice?. The Journal of Risk Finance .

Stein, R. M. (2012). The role of stress testing in credit risk management. Journal of investment management , 10 (4), 64.

Thun, C. (2012). Common Pitfalls in Stress Testing. Moody’s Analytics .

Vyas, M., & Singh, S. (2011). Risk Management in Banking Sector. BVIMR Management Edge , 4 (1).

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Related Essays

Hudson bay company, born global companies and multinational corporations, the complexity of healthcare costs in america, review and obligation of amazon website, great southern bank’s sustainability initiatives:navigating sustainability risks and opportunities in the banking sector, how to make saving a habit, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How Banks Can Finally Get Risk Management Right

- James C. Lam

SVB was a cautionary tale.

Banks have three lines of defense for managing risk — and then regulators are the fourth line of defense. In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, all four failed. If banks want to manage risk better, one good place to start is making sure a Chief Risk Officer is in place and a board-level risk committee is in place. And the people on that committee should have real experience in managing enterprise risk.

Here we go again. Banks ought to have the best risk management. But whatever safeguards were in place didn’t prevent Silicon Valley Bank from failing, destroying over $40 billion in shareholder value, and forcing unprecedented government intervention to protect depositors.

- JL James C. Lam is President, James Lam & Associates, a risk management consulting firm. Previously, he served as Partner of Oliver Wyman and chief risk officer at Fidelity Investments and GE Capital Market Services. He is the author of Implementing Enterprise Risk Management: From Methods to Applications .

Partner Center

- Open access

- Published: 03 September 2022

A literature review of risk, regulation, and profitability of banks using a scientometric study

- Shailesh Rastogi 1 ,

- Arpita Sharma 1 ,

- Geetanjali Pinto 2 &

- Venkata Mrudula Bhimavarapu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9757-1904 1 , 3

Future Business Journal volume 8 , Article number: 28 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

This study presents a systematic literature review of regulation, profitability, and risk in the banking industry and explores the relationship between them. It proposes a policy initiative using a model that offers guidelines to establish the right mix among these variables. This is a systematic literature review study. Firstly, the necessary data are extracted using the relevant keywords from the Scopus database. The initial search results are then narrowed down, and the refined results are stored in a file. This file is finally used for data analysis. Data analysis is done using scientometrics tools, such as Table2net and Sciences cape software, and Gephi to conduct network, citation analysis, and page rank analysis. Additionally, content analysis of the relevant literature is done to construct a theoretical framework. The study identifies the prominent authors, keywords, and journals that researchers can use to understand the publication pattern in banking and the link between bank regulation, performance, and risk. It also finds that concentration banking, market power, large banks, and less competition significantly affect banks’ financial stability, profitability, and risk. Ownership structure and its impact on the performance of banks need to be investigated but have been inadequately explored in this study. This is an organized literature review exploring the relationship between regulation and bank performance. The limitations of the regulations and the importance of concentration banking are part of the findings.

Introduction

Globally, banks are under extreme pressure to enhance their performance and risk management. The financial industry still recalls the ignoble 2008 World Financial Crisis (WFC) as the worst economic disaster after the Great Depression of 1929. The regulatory mechanism before 2008 (mainly Basel II) was strongly criticized for its failure to address banks’ risks [ 47 , 87 ]. Thus, it is essential to investigate the regulation of banks [ 75 ]. This study systematically reviews the relevant literature on banks’ performance and risk management and proposes a probable solution.

Issues of performance and risk management of banks

Banks have always been hailed as engines of economic growth and have been the axis of the development of financial systems [ 70 , 85 ]. A vital parameter of a bank’s financial health is the volume of its non-performing assets (NPAs) on its balance sheet. NPAs are advances that delay in payment of interest or principal beyond a few quarters [ 108 , 118 ]. According to Ghosh [ 51 ], NPAs negatively affect the liquidity and profitability of banks, thus affecting credit growth and leading to financial instability in the economy. Hence, healthy banks translate into a healthy economy.

Despite regulations, such as high capital buffers and liquidity ratio requirements, during the second decade of the twenty-first century, the Indian banking sector still witnessed a substantial increase in NPAs. A recent report by the Indian central bank indicates that the gross NPA ratio reached an all-time peak of 11% in March 2018 and 12.2% in March 2019 [ 49 ]. Basel II has been criticized for several reasons [ 98 ]. Schwerter [ 116 ] and Pakravan [ 98 ] highlighted the systemic risk and gaps in Basel II, which could not address the systemic risk of WFC 2008. Basel III was designed to close the gaps in Basel II. However, Schwerter [ 116 ] criticized Basel III and suggested that more focus should have been on active risk management practices to avoid any impending financial crisis. Basel III was proposed to solve these issues, but it could not [ 3 , 116 ]. Samitas and Polyzos [ 113 ] found that Basel III had made banking challenging since it had reduced liquidity and failed to shield the contagion effect. Therefore, exploring some solutions to establish the right balance between regulation, performance, and risk management of banks is vital.

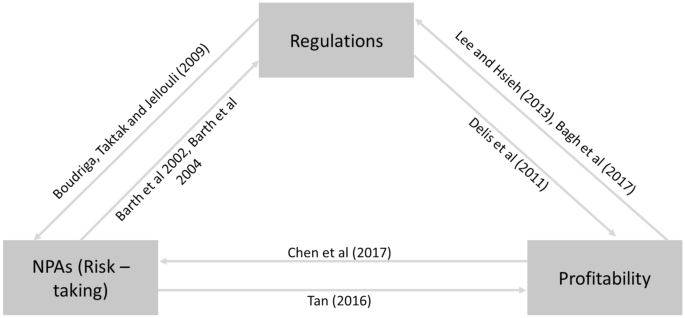

Keeley [ 67 ] introduced the idea of a balance among banks’ profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking). This study presents the balancing act of profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking) of banks as a probable solution to the issues of bank performance and risk management and calls it a triad . Figure 1 illustrates the concept of a triad. Several authors have discussed the triad in parts [ 32 , 96 , 110 , 112 ]. Triad was empirically tested in different countries by Agoraki et al. [ 1 ]. Though the idea of a triad is quite old, it is relevant in the current scenario. The spirit of the triad strongly and collectively admonishes the Basel Accord and exhibits new and exhaustive measures to take up and solve the issue of performance and risk management in banks [ 16 , 98 ]. The 2008 WFC may have caused an imbalance among profitability, regulation, and risk-taking of banks [ 57 ]. Less regulation , more competition (less profitability ), and incentive to take the risk were the cornerstones of the 2008 WFC [ 56 ]. Achieving a balance among the three elements of a triad is a real challenge for banks’ performance and risk management, which this study addresses.

Triad of Profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking). Note The triad [ 131 ] of profitability, regulation, and NPA (risk-taking) is shown in Fig. 1

Triki et al. [ 130 ] revealed that a bank’s performance is a trade-off between the elements of the triad. Reduction in competition increases the profitability of banks. However, in the long run, reduction in competition leads to either the success or failure of banks. Flexible but well-expressed regulation and less competition add value to a bank’s performance. The current review paper is an attempt to explore the literature on this triad of bank performance, regulation, and risk management. This paper has the following objectives:

To systematically explore the existing literature on the triad: performance, regulation, and risk management of banks; and

To propose a model for effective bank performance and risk management of banks.

Literature is replete with discussion across the world on the triad. However, there is a lack of acceptance of the triad as a solution to the woes of bank performance and risk management. Therefore, the findings of the current papers significantly contribute to this regard. This paper collates all the previous studies on the triad systematically and presents a curated view to facilitate the policy makers and stakeholders to make more informed decisions on the issue of bank performance and risk management. This paper also contributes significantly by proposing a DBS (differential banking system) model to solve the problem of banks (Fig. 7 ). This paper examines studies worldwide and therefore ensures the wider applicability of its findings. Applicability of the DBS model is not only limited to one nation but can also be implemented worldwide. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the publication pattern in banking using a blend of scientometrics analysis tools, network analysis tools, and content analysis to understand the link between bank regulation, performance, and risk.

This paper is divided into five sections. “ Data and research methods ” section discusses the research methodology used for the study. The data analysis for this study is presented in two parts. “ Bibliometric and network analysis ” section presents the results obtained using bibliometric and network analysis tools, followed by “ Content Analysis ” section, which presents the content analysis of the selected literature. “ Discussion of the findings ” section discusses the results and explains the study’s conclusion, followed by limitations and scope for further research.

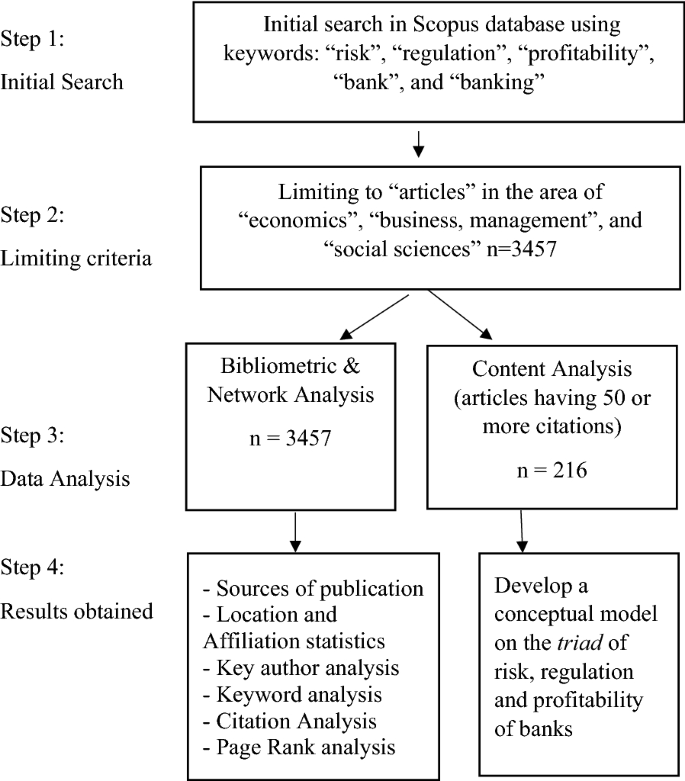

Data and research methods

A literature review is a systematic, reproducible, and explicit way of identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing relevant research produced and published by researchers [ 50 , 100 ]. Analyzing existing literature helps researchers generate new themes and ideas to justify the contribution made to literature. The knowledge obtained through evidence-based research also improves decision-making leading to better practical implementation in the real corporate world [ 100 , 129 ].

As Kumar et al. [ 77 , 78 ] and Rowley and Slack [ 111 ] recommended conducting an SLR, this study also employs a three-step approach to understand the publication pattern in the banking area and establish a link between bank performance, regulation, and risk.

Determining the appropriate keywords for exploring the data

Many databases such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus are available to extract the relevant data. The quality of a publication is associated with listing a journal in a database. Scopus is a quality database as it has a wider coverage of data [ 100 , 137 ]. Hence, this study uses the Scopus database to extract the relevant data.

For conducting an SLR, there is a need to determine the most appropriate keywords to be used in the database search engine [ 26 ]. Since this study seeks to explore a link between regulation, performance, and risk management of banks, the keywords used were “risk,” “regulation,” “profitability,” “bank,” and “banking.”

Initial search results and limiting criteria

Using the keywords identified in step 1, the search for relevant literature was conducted in December 2020 in the Scopus database. This resulted in the search of 4525 documents from inception till December 2020. Further, we limited our search to include “article” publications only and included subject areas: “Economics, Econometrics and Finance,” “Business, Management and Accounting,” and “Social sciences” only. This resulted in a final search result of 3457 articles. These results were stored in a.csv file which is then used as an input to conduct the SLR.

Data analysis tools and techniques

This study uses bibliometric and network analysis tools to understand the publication pattern in the area of research [ 13 , 48 , 100 , 122 , 129 , 134 ]. Some sub-analyses of network analysis are keyword word, author, citation, and page rank analysis. Author analysis explains the author’s contribution to literature or research collaboration, national and international [ 59 , 99 ]. Citation analysis focuses on many researchers’ most cited research articles [ 100 , 102 , 131 ].

The.csv file consists of all bibliometric data for 3457 articles. Gephi and other scientometrics tools, such as Table2net and ScienceScape software, were used for the network analysis. This.csv file is directly used as an input for this software to obtain network diagrams for better data visualization [ 77 ]. To ensure the study’s quality, the articles with 50 or more citations (216 in number) are selected for content analysis [ 53 , 102 ]. The contents of these 216 articles are analyzed to develop a conceptual model of banks’ triad of risk, regulation, and profitability. Figure 2 explains the data retrieval process for SLR.

Data retrieval process for SLR. Note Stepwise SLR process and corresponding results obtained

Bibliometric and network analysis

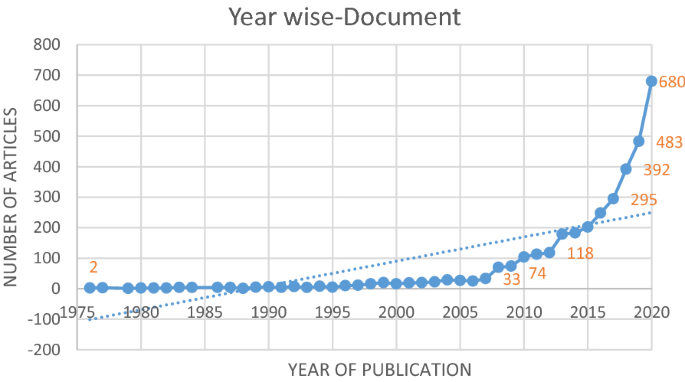

Figure 3 [ 58 ] depicts the total number of studies that have been published on “risk,” “regulation,” “profitability,” “bank,” and “banking.” Figure 3 also depicts the pattern of the quality of the publications from the beginning till 2020. It undoubtedly shows an increasing trend in the number of articles published in the area of the triad: “risk” regulation” and “profitability.” Moreover, out of the 3457 articles published in the said area, 2098 were published recently in the last five years and contribute to 61% of total publications in this area.

Articles published from 1976 till 2020 . Note The graph shows the number of documents published from 1976 till 2020 obtained from the Scopus database

Source of publications

A total of 160 journals have contributed to the publication of 3457 articles extracted from Scopus on the triad of risk, regulation, and profitability. Table 1 shows the top 10 sources of the publications based on the citation measure. Table 1 considers two sets of data. One data set is the universe of 3457 articles, and another is the set of 216 articles used for content analysis along with their corresponding citations. The global citations are considered for the study from the Scopus dataset, and the local citations are considered for the articles in the nodes [ 53 , 135 ]. The top 10 journals with 50 or more citations resulted in 96 articles. This is almost 45% of the literature used for content analysis ( n = 216). Table 1 also shows that the Journal of Banking and Finance is the most prominent in terms of the number of publications and citations. It has 46 articles published, which is about 21% of the literature used for content analysis. Table 1 also shows these core journals’ SCImago Journal Rank indicator and H index. SCImago Journal Rank indicator reflects the impact and prestige of the Journal. This indicator is calculated as the previous three years’ weighted average of the number of citations in the Journal since the year that the article was published. The h index is the number of articles (h) published in a journal and received at least h. The number explains the scientific impact and the scientific productivity of the Journal. Table 1 also explains the time span of the journals covering articles in the area of the triad of risk, regulation, and profitability [ 7 ].

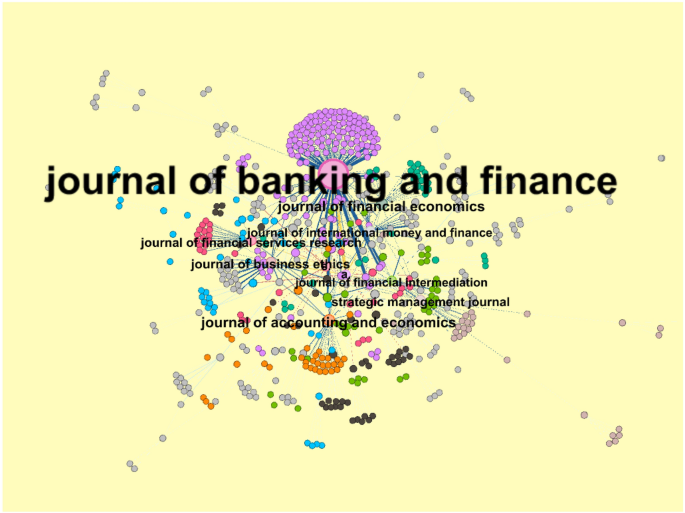

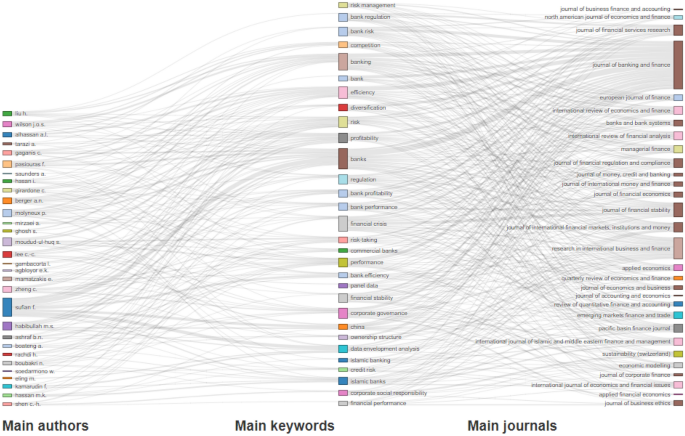

Figure 4 depicts the network analysis, where the connections between the authors and source title (journals) are made. The network has 674 nodes and 911 edges. The network between the author and Journal is classified into 36 modularities. Sections of the graph with dense connections indicate high modularity. A modularity algorithm is a design that measures how strong the divided networks are grouped into modules; this means how well the nodes are connected through a denser route relative to other networks.

Network analysis between authors and journals. Note A node size explains the more linked authors to a journal

The size of the nodes is based on the rank of the degree. The degree explains the number of connections or edges linked to a node. In the current graph, a node represents the name of the Journal and authors; they are connected through the edges. Therefore, the more the authors are associated with the Journal, the higher the degree. The algorithm used for the layout is Yifan Hu’s.

Many authors are associated with the Journal of Banking and Finance, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Journal of Financial Economics, Journal of Financial Services Research, and Journal of Business Ethics. Therefore, they are the most relevant journals on banks’ risk, regulation, and profitability.

Location and affiliation analysis

Affiliation analysis helps to identify the top contributing countries and universities. Figure 5 shows the countries across the globe where articles have been published in the triad. The size of the circle in the map indicates the number of articles published in that country. Table 2 provides the details of the top contributing organizations.

Location of articles published on Triad of profitability, regulation, and risk

Figure 5 shows that the most significant number of articles is published in the USA, followed by the UK. Malaysia and China have also contributed many articles in this area. Table 2 shows that the top contributing universities are also from Malaysia, the UK, and the USA.

Key author analysis

Table 3 shows the number of articles written by the authors out of the 3457 articles. The table also shows the top 10 authors of bank risk, regulation, and profitability.

Fadzlan Sufian, affiliated with the Universiti Islam Malaysia, has the maximum number, with 33 articles. Philip Molyneux and M. Kabir Hassan are from the University of Sharjah and the University of New Orleans, respectively; they contributed significantly, with 20 and 18 articles, respectively.

However, when the quality of the article is selected based on 50 or more citations, Fadzlan Sufian has only 3 articles with more than 50 citations. At the same time, Philip Molyneux and Allen Berger contributed more quality articles, with 8 and 11 articles, respectively.

Keyword analysis

Table 4 shows the keyword analysis (times they appeared in the articles). The top 10 keywords are listed in Table 4 . Banking and banks appeared 324 and 194 times, respectively, which forms the scope of this study, covering articles from the beginning till 2020. The keyword analysis helps to determine the factors affecting banks, such as profitability (244), efficiency (129), performance (107, corporate governance (153), risk (90), and regulation (89).

The keywords also show that efficiency through data envelopment analysis is a determinant of the performance of banks. The other significant determinants that appeared as keywords are credit risk (73), competition (70), financial stability (69), ownership structure (57), capital (56), corporate social responsibility (56), liquidity (46), diversification (45), sustainability (44), credit provision (41), economic growth (41), capital structure (39), microfinance (39), Basel III (37), non-performing assets (37), cost efficiency (30), lending behavior (30), interest rate (29), mergers and acquisition (28), capital adequacy (26), developing countries (23), net interest margin (23), board of directors (21), disclosure (21), leverage (21), productivity (20), innovation (18), firm size (16), and firm value (16).

Keyword analysis also shows the theories of banking and their determinants. Some of the theories are agency theory (23), information asymmetry (21), moral hazard (17), and market efficiency (16), which can be used by researchers when building a theory. The analysis also helps to determine the methodology that was used in the published articles; some of them are data envelopment analysis (89), which measures technical efficiency, panel data analysis (61), DEA (32), Z scores (27), regression analysis (23), stochastic frontier analysis (20), event study (15), and literature review (15). The count for literature review is only 15, which confirms that very few studies have conducted an SLR on bank risk, regulation, and profitability.

Citation analysis

One of the parameters used in judging the quality of the article is its “citation.” Table 5 shows the top 10 published articles with the highest number of citations. Ding and Cronin [ 44 ] indicated that the popularity of an article depends on the number of times it has been cited.

Tahamtan et al. [ 126 ] explained that the journal’s quality also affects its published articles’ citations. A quality journal will have a high impact factor and, therefore, more citations. The citation analysis helps researchers to identify seminal articles. The title of an article with 5900 citations is “A survey of corporate governance.”

Page Rank analysis

Goyal and Kumar [ 53 ] explain that the citation analysis indicates the ‘popularity’ and ‘prestige’ of the published research article. Apart from the citation analysis, one more analysis is essential: Page rank analysis. PageRank is given by Page et al. [ 97 ]. The impact of an article can be measured with one indicator called PageRank [ 135 ]. Page rank analysis indicates how many times an article is cited by other highly cited articles. The method helps analyze the web pages, which get the priority during any search done on google. The analysis helps in understanding the citation networks. Equation 1 explains the page rank (PR) of a published paper, N refers to the number of articles.

T 1,… T n indicates the paper, which refers paper P . C ( Ti ) indicates the number of citations. The damping factor is denoted by a “ d ” which varies in the range of 0 and 1. The page rank of all the papers is equal to 1. Table 6 shows the top papers based on page rank. Tables 5 and 6 together show a contrast in the top ranked articles based on citations and page rank, respectively. Only one article “A survey of corporate governance” falls under the prestigious articles based on the page rank.

Content analysis

Content Analysis is a research technique for conducting qualitative and quantitative analyses [ 124 ]. The content analysis is a helpful technique that provides the required information in classifying the articles depending on their nature (empirical or conceptual) [ 76 ]. By adopting the content analysis method [ 53 , 102 ], the selected articles are examined to determine their content. The classification of available content from the selected set of sample articles that are categorized under different subheads. The themes identified in the relationship between banking regulation, risk, and profitability are as follows.

Regulation and profitability of banks

The performance indicators of the banking industry have always been a topic of interest to researchers and practitioners. This area of research has assumed a special interest after the 2008 WFC [ 25 , 51 , 86 , 114 , 127 , 132 ]. According to research, the causes of poor performance and risk management are lousy banking practices, ineffective monitoring, inadequate supervision, and weak regulatory mechanisms [ 94 ]. Increased competition, deregulation, and complex financial instruments have made banks, including Indian banks, more vulnerable to risks [ 18 , 93 , 119 , 123 ]. Hence, it is essential to investigate the present regulatory machinery for the performance of banks.

There are two schools of thought on regulation and its possible impact on profitability. The first asserts that regulation does not affect profitability. The second asserts that regulation adds significant value to banks’ profitability and other performance indicators. This supports the concept that Delis et al. [ 41 ] advocated that the capital adequacy requirement and supervisory power do not affect productivity or profitability unless there is a financial crisis. Laeven and Majnoni [ 81 ] insisted that provision for loan loss should be part of capital requirements. This will significantly improve active risk management practices and ensure banks’ profitability.

Lee and Hsieh [ 83 ] proposed ambiguous findings that do not support either school of thought. According to Nguyen and Nghiem [ 95 ], while regulation is beneficial, it has a negative impact on bank profitability. As a result, when proposing regulations, it is critical to consider bank performance and risk management. According to Erfani and Vasigh [ 46 ], Islamic banks maintained their efficiency between 2006 and 2013, while most commercial banks lost, furthermore claimed that the financial crisis had no significant impact on Islamic bank profitability.

Regulation and NPA (risk-taking of banks)

The regulatory mechanism of banks in any country must address the following issues: capital adequacy ratio, prudent provisioning, concentration banking, the ownership structure of banks, market discipline, regulatory devices, presence of foreign capital, bank competition, official supervisory power, independence of supervisory bodies, private monitoring, and NPAs [ 25 ].

Kanoujiya et al. [ 64 ] revealed through empirical evidence that Indian bank regulations lack a proper understanding of what banks require and propose reforming and transforming regulation in Indian banks so that responsive governance and regulation can occur to make banks safer, supported by Rastogi et al. [ 105 ]. The positive impact of regulation on NPAs is widely discussed in the literature. [ 94 ] argue that regulation has multiple effects on banks, including reducing NPAs. The influence is more powerful if the country’s banking system is fragile. Regulation, particularly capital regulation, is extremely effective in reducing risk-taking in banks [ 103 ].

Rastogi and Kanoujiya [ 106 ] discovered evidence that disclosure regulations do not affect the profitability of Indian banks, supported by Karyani et al. [ 65 ] for the banks located in Asia. Furthermore, Rastogi and Kanoujiya [ 106 ] explain that disclosure is a difficult task as a regulatory requirement. It is less sustainable due to the nature of the imposed regulations in banks and may thus be perceived as a burden and may be overcome by realizing the benefits associated with disclosure regulation [ 31 , 54 , 101 ]. Zheng et al. [ 138 ] empirically discovered that regulation has no impact on the banks’ profitability in Bangladesh.

Governments enforce banking regulations to achieve a stable and efficient financial system [ 20 , 94 ]. The existing literature is inconclusive on the effects of regulatory compliance on banks’ risks or the reduction of NPAs [ 10 , 11 ]. Boudriga et al. [ 25 ] concluded that the regulatory mechanism plays an insignificant role in reducing NPAs. This is especially true in weak institutions, which are susceptible to corruption. Gonzalez [ 52 ] reported that firm regulations have a positive relationship with banks’ risk-taking, increasing the probability of NPAs. However, Boudriga et al. [ 25 ], Samitas and Polyzos [ 113 ], and Allen et al. [ 3 ] strongly oppose the use of regulation as a tool to reduce banks’ risk-taking.

Kwan and Laderman [ 79 ] proposed three levels in regulating banks, which are lax, liberal, and strict. The liberal regulatory framework leads to more diversification in banks. By contrast, the strict regulatory framework forces the banks to take inappropriate risks to compensate for the loss of business; this is a global problem [ 73 ].

Capital regulation reduces banks’ risk-taking [ 103 , 110 ]. Capital regulation leads to cost escalation, but the benefits outweigh the cost [ 103 ]. The trade-off is worth striking. Altman Z score is used to predict banks’ bankruptcy, and it found that the regulation increased the Altman’s Z-score [ 4 , 46 , 63 , 68 , 72 , 120 ]. Jin et al. [ 62 ] report a negative relationship between regulation and banks’ risk-taking. Capital requirements empowered regulators, and competition significantly reduced banks’ risk-taking [ 1 , 122 ]. Capital regulation has a limited impact on banks’ risk-taking [ 90 , 103 ].

Maji and De [ 90 ] suggested that human capital is more effective in managing banks’ credit risks. Besanko and Kanatas [ 21 ] highlighted that regulation on capital requirements might not mitigate risks in all scenarios, especially when recapitalization has been enforced. Klomp and De Haan [ 72 ] proposed that capital requirements and supervision substantially reduce banks’ risks.

A third-party audit may impart more legitimacy to the banking system [ 23 ]. The absence of third-party intervention is conspicuous, and this may raise a doubt about the reliability and effectiveness of the impact of regulation on bank’s risk-taking.

NPA (risk-taking) in banks and profitability

Profitability affects NPAs, and NPAs, in turn, affect profitability. According to the bad management hypothesis [ 17 ], higher profits would negatively affect NPAs. By contrast, higher profits may lead management to resort to a liberal credit policy (high earnings), which may eventually lead to higher NPAs [ 104 ].

Balasubramaniam [ 8 ] demonstrated that NPA has double negative effects on banks. NPAs increase stressed assets, reducing banks’ productive assets [ 92 , 117 , 136 ]. This phenomenon is relatively underexplored and therefore renders itself for future research.

Triad and the performance of banks

Regulation and triad.

Regulations and their impact on banks have been a matter of debate for a long time. Barth et al. [ 12 ] demonstrated that countries with a central bank as the sole regulatory body are prone to high NPAs. Although countries with multiple regulatory bodies have high liquidity risks, they have low capital requirements [ 40 ]. Barth et al. [ 12 ] supported the following steps to rationalize the existing regulatory mechanism on banks: (1) mandatory information [ 22 ], (2) empowered management of banks, and (3) increased incentive for private agents to exert corporate control. They show that profitability has an inverse relationship with banks’ risk-taking [ 114 ]. Therefore, standard regulatory practices, such as capital requirements, are not beneficial. However, small domestic banks benefit from capital restrictions.

DeYoung and Jang [ 43 ] showed that Basel III-based policies of liquidity convergence ratio (LCR) and net stable funding ratio (NSFR) are not fully executed across the globe, including the US. Dahir et al. [ 39 ] found that a decrease in liquidity and funding increases banks’ risk-taking, making banks vulnerable and reducing stability. Therefore, any regulation on liquidity risk is more likely to create problems for banks.

Concentration banking and triad

Kiran and Jones [ 71 ] asserted that large banks are marginally affected by NPAs, whereas small banks are significantly affected by high NPAs. They added a new dimension to NPAs and their impact on profitability: concentration banking or banks’ market power. Market power leads to less cost and more profitability, which can easily counter the adverse impact of NPAs on profitability [ 6 , 15 ].

The connection between the huge volume of research on the performance of banks and competition is the underlying concept of market power. Competition reduces market power, whereas concentration banking increases market power [ 25 ]. Concentration banking reduces competition, increases market power, rationalizes the banks’ risk-taking, and ensures profitability.

Tabak et al. [ 125 ] advocated that market power incentivizes banks to become risk-averse, leading to lower costs and high profits. They explained that an increase in market power reduces the risk-taking requirement of banks. Reducing banks’ risks due to market power significantly increases when capital regulation is executed objectively. Ariss [ 6 ] suggested that increased market power decreases competition, and thus, NPAs reduce, leading to increased banks’ stability.

Competition, the performance of banks, and triad

Boyd and De Nicolo [ 27 ] supported that competition and concentration banking are inversely related, whereas competition increases risk, and concentration banking decreases risk. A mere shift toward concentration banking can lead to risk rationalization. This finding has significant policy implications. Risk reduction can also be achieved through stringent regulations. Bolt and Tieman [ 24 ] explained that stringent regulation coupled with intense competition does more harm than good, especially concerning banks’ risk-taking.

Market deregulation, as well as intensifying competition, would reduce the market power of large banks. Thus, the entire banking system might take inappropriate and irrational risks [ 112 ]. Maji and Hazarika [ 91 ] added more confusion to the existing policy by proposing that, often, there is no relationship between capital regulation and banks’ risk-taking. However, some cases have reported a positive relationship. This implies that banks’ risk-taking is neutral to regulation or leads to increased risk. Furthermore, Maji and Hazarika [ 91 ] revealed that competition reduces banks’ risk-taking, contrary to popular belief.

Claessens and Laeven [ 36 ] posited that concentration banking influences competition. However, this competition exists only within the restricted circle of banks, which are part of concentration banking. Kasman and Kasman [ 66 ] found that low concentration banking increases banks’ stability. However, they were silent on the impact of low concentration banking on banks’ risk-taking. Baselga-Pascual et al. [ 14 ] endorsed the earlier findings that concentration banking reduces banks’ risk-taking.

Concentration banking and competition are inversely related because of the inherent design of concentration banking. Market power increases when only a few large banks are operating; thus, reduced competition is an obvious outcome. Barra and Zotti [ 9 ] supported the idea that market power, coupled with competition between the given players, injects financial stability into banks. Market power and concentration banking affect each other. Therefore, concentration banking with a moderate level of regulation, instead of indiscriminate regulation, would serve the purpose better. Baselga-Pascual et al. [ 14 ] also showed that concentration banking addresses banks’ risk-taking.

Schaeck et al. [ 115 ], in a landmark study, presented that concentration banking and competition reduce banks’ risk-taking. However, they did not address the relationship between concentration banking and competition, which are usually inversely related. This could be a subject for future research. Research on the relationship between concentration banking and competition is scant, identified as a research gap (“ Research Implications of the study ” section).

Transparency, corporate governance, and triad

One of the big problems with NPAs is the lack of transparency in both the regulatory bodies and banks [ 25 ]. Boudriga et al. [ 25 ] preferred to view NPAs as a governance issue and thus, recommended viewing it from a governance perspective. Ahmad and Ariff [ 2 ] concluded that regulatory capital and top-management quality determine banks’ credit risk. Furthermore, they asserted that credit risk in emerging economies is higher than that of developed economies.

Bad management practices and moral vulnerabilities are the key determinants of insolvency risks of Indian banks [ 95 ]. Banks are an integral part of the economy and engines of social growth. Therefore, banks enjoy liberal insolvency protection in India, especially public sector banks, which is a critical issue. Such a benevolent insolvency cover encourages a bank to be indifferent to its capital requirements. This indifference takes its toll on insolvency risk and profit efficiency. Insolvency protection makes the bank operationally inefficient and complacent.

Foreign equity and corporate governance practices help manage the adverse impact of banks’ risk-taking to ensure the profitability and stability of banks [ 33 , 34 ]. Eastburn and Sharland [ 45 ] advocated that sound management and a risk management system that can anticipate any impending risk are essential. A pragmatic risk mechanism should replace the existing conceptual risk management system.

Lo [ 87 ] found and advocated that the existing legislation and regulations are outdated. He insisted on a new perspective and asserted that giving equal importance to behavioral aspects and the rational expectations of customers of banks is vital. Buston [ 29 ] critiqued the balance sheet risk management practices prevailing globally. He proposed active risk management practices that provided risk protection measures to contain banks’ liquidity and solvency risks.

Klomp and De Haan [ 72 ] championed the cause of giving more autonomy to central banks of countries to provide stability in the banking system. Louzis et al. [ 88 ] showed that macroeconomic variables and the quality of bank management determine banks’ level of NPAs. Regulatory authorities are striving hard to make regulatory frameworks more structured and stringent. However, the recent increase in loan defaults (NPAs), scams, frauds, and cyber-attacks raise concerns about the effectiveness [ 19 ] of the existing banking regulations in India as well as globally.

Discussion of the findings

The findings of this study are based on the bibliometric and content analysis of the sample published articles.

The bibliometric study concludes that there is a growing demand for researchers and good quality research

The keyword analysis suggests that risk regulation, competition, profitability, and performance are key elements in understanding the banking system. The main authors, keywords, and journals are grouped in a Sankey diagram in Fig. 6 . Researchers can use the following information to understand the publication pattern on banking and its determinants.

Sankey Diagram of main authors, keywords, and journals. Note Authors contribution using scientometrics tools

Research Implications of the study

The study also concludes that a balance among the three components of triad is the solution to the challenges of banks worldwide, including India. We propose the following recommendations and implications for banks:

This study found that “the lesser the better,” that is, less regulation enhances the performance and risk management of banks. However, less regulation does not imply the absence of regulation. Less regulation means the following:

Flexible but full enforcement of the regulations

Customization, instead of a one-size-fits-all regulatory system rooted in a nation’s indigenous requirements, is needed. Basel or generic regulation can never achieve what a customized compliance system can.

A third-party audit, which is above the country's central bank, should be mandatory, and this would ensure that all three aspects of audit (policy formulation, execution, and audit) are handled by different entities.

Competition

This study asserts that the existing literature is replete with poor performance and risk management due to excessive competition. Banking is an industry of a different genre, and it would be unfair to compare it with the fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) or telecommunication industry, where competition injects efficiency into the system, leading to customer empowerment and satisfaction. By contrast, competition is a deterrent to the basic tenets of safe banking. Concentration banking is more effective in handling the multi-pronged balance between the elements of the triad. Concentration banking reduces competition to lower and manageable levels, reduces banks’ risk-taking, and enhances profitability.

No incentive to take risks

It is found that unless banks’ risk-taking is discouraged, the problem of high NPA (risk-taking) cannot be addressed. Concentration banking is a disincentive to risk-taking and can be a game-changer in handling banks’ performance and risk management.

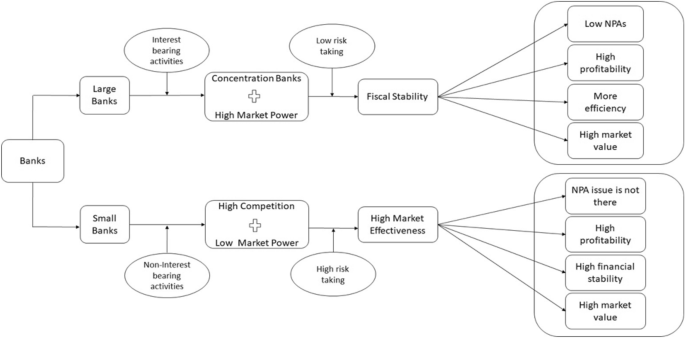

Research on the risk and performance of banks reveals that the existing regulatory and policy arrangement is not a sustainable proposition, especially for a country where half of the people are unbanked [ 37 ]. Further, the triad presented by Keeley [ 67 ] is a formidable real challenge to bankers. The balance among profitability, risk-taking, and regulation is very subtle and becomes harder to strike, just as the banks globally have tried hard to achieve it. A pragmatic intervention is needed; hence, this study proposes a change in the banking structure by having two types of banks functioning simultaneously to solve the problems of risk and performance of banks. The proposed two-tier banking system explained in Fig. 7 can be a great solution. This arrangement will help achieve the much-needed balance among the elements of triad as presented by Keeley [ 67 ].

Conceptual Framework. Note Fig. 7 describes the conceptual framework of the study

The first set of banks could be conventional in terms of their structure and should primarily be large-sized. The number of such banks should be moderate. There is a logic in having only a few such banks to restrict competition; thus, reasonable market power could be assigned to them [ 55 ]. However, a reduction in competition cannot be over-assumed, and banks cannot become complacent. As customary, lending would be the main source of revenue and income for these banks (fund based activities) [ 82 ]. The proposed two-tier system can be successful only when regulation especially for risk is objectively executed [ 29 ]. The second set of banks could be smaller in size and more in number. Since they are more in number, they would encounter intense competition for survival and for generating more business. Small is beautiful, and thus, this set of banks would be more agile and adaptable and consequently more efficient and profitable. The main source of revenue for this set of banks would not be loans and advances. However, non-funding and non-interest-bearing activities would be the major revenue source. Unlike their traditional and large-sized counterparts, since these banks are smaller in size, they are less likely to face risk-taking and NPAs [ 74 ].

Sarmiento and Galán [ 114 ] presented the concerns of large and small banks and their relative ability and appetite for risk-taking. High risk could threaten the existence of small-sized banks; thus, they need robust risk shielding. Small size makes them prone to failure, and they cannot convert their risk into profitability. However, large banks benefit from their size and are thus less vulnerable and can convert risk into profitable opportunities.

India has experimented with this Differential Banking System (DBS) (two-tier system) only at the policy planning level. The execution is impending, and it highly depends on the political will, which does not appear to be strong now. The current agenda behind the DBS model is not to ensure the long-term sustainability of banks. However, it is currently being directed to support the agenda of financial inclusion by extending the formal credit system to the unbanked masses [ 107 ]. A shift in goal is needed to employ the DBS as a strategic decision, but not merely a tool for financial inclusion. Thus, the proposed two-tier banking system (DBS) can solve the issue of profitability through proper regulation and less risk-taking.

The findings of Triki et al. [ 130 ] support the proposed DBS model, in this study. Triki et al. [ 130 ] advocated that different component of regulations affect banks based on their size, risk-taking, and concentration banking (or market power). Large size, more concentration banking with high market power, and high risk-taking coupled with stringent regulation make the most efficient banks in African countries. Sharifi et al. [ 119 ] confirmed that size advantage offers better risk management to large banks than small banks. The banks should modify and work according to the economic environment in the country [ 69 ], and therefore, the proposed model could help in solving the current economic problems.

This is a fact that DBS is running across the world, including in India [ 60 ] and other countries [ 133 ]. India experimented with DBS in the form of not only regional rural banks (RRBs) but payments banks [ 109 ] and small finance banks as well [ 61 ]. However, the purpose of all the existing DBS models, whether RRBs [ 60 ], payment banks, or small finance banks, is financial inclusion, not bank performance and risk management. Hence, they are unable to sustain and are failing because their model is only social instead of a much-needed dual business-cum-social model. The two-tier model of DBS proposed in the current paper can help serve the dual purpose. It may not only be able to ensure bank performance and risk management but also serve the purpose of inclusive growth of the economy.

Conclusion of the study

The study’s conclusions have some significant ramifications. This study can assist researchers in determining their study plan on the current topic by using a scientific approach. Citation analysis has aided in the objective identification of essential papers and scholars. More collaboration between authors from various countries/universities may help countries/universities better understand risk regulation, competition, profitability, and performance, which are critical elements in understanding the banking system. The regulatory mechanism in place prior to 2008 failed to address the risk associated with banks [ 47 , 87 ]. There arises a necessity and motivates authors to investigate the current topic. The present study systematically explores the existing literature on banks’ triad: performance, regulation, and risk management and proposes a probable solution.

To conclude the bibliometric results obtained from the current study, from the number of articles published from 1976 to 2020, it is evident that most of the articles were published from the year 2010, and the highest number of articles were published in the last five years, i.e., is from 2015. The authors discovered that researchers evaluate articles based on the scope of critical journals within the subject area based on the detailed review. Most risk, regulation, and profitability articles are published in peer-reviewed journals like; “Journal of Banking and Finance,” “Journal of Accounting and Economics,” and “Journal of Financial Economics.” The rest of the journals are presented in Table 1 . From the affiliation statistics, it is clear that most of the research conducted was affiliated with developed countries such as Malaysia, the USA, and the UK. The researchers perform content analysis and Citation analysis to access the type of content where the research on the current field of knowledge is focused, and citation analysis helps the academicians understand the highest cited articles that have more impact in the current research area.

Practical implications of the study

The current study is unique in that it is the first to systematically evaluate the publication pattern in banking using a combination of scientometrics analysis tools, network analysis tools, and content analysis to understand the relationship between bank regulation, performance, and risk. The study’s practical implications are that analyzing existing literature helps researchers generate new themes and ideas to justify their contribution to literature. Evidence-based research knowledge also improves decision-making, resulting in better practical implementation in the real corporate world [ 100 , 129 ].

Limitations and scope for future research

The current study only considers a single database Scopus to conduct the study, and this is one of the limitations of the study spanning around the multiple databases can provide diverse results. The proposed DBS model is a conceptual framework that requires empirical testing, which is a limitation of this study. As a result, empirical testing of the proposed DBS model could be a future research topic.

Availability of data and materials

SCOPUS database.

Abbreviations

Systematic literature review

World Financial Crisis

Non-performing assets

Differential banking system

SCImago Journal Rank Indicator

Liquidity convergence ratio

Net stable funding ratio

Fast moving consumer goods

Regional rural banks

Agoraki M-EK, Delis MD, Pasiouras F (2011) Regulations, competition and bank risk-taking in transition countries. J Financ Stab 7(1):38–48

Google Scholar

Ahmad NH, Ariff M (2007) Multi-country study of bank credit risk determinants. Int J Bank Financ 5(1):35–62

Allen B, Chan KK, Milne A, Thomas S (2012) Basel III: Is the cure worse than the disease? Int Rev Financ Anal 25:159–166

Altman EI (2018) A fifty-year retrospective on credit risk models, the Altman Z-score family of models, and their applications to financial markets and managerial strategies. J Credit Risk 14(4):1–34

Alvarez F, Jermann UJ (2000) Efficiency, equilibrium, and asset pricing with risk of default. Econometrica 68(4):775–797

Ariss RT (2010) On the implications of market power in banking: evidence from developing countries. J Bank Financ 34(4):765–775

Aznar-Sánchez JA, Piquer-Rodríguez M, Velasco-Muñoz JF, Manzano-Agugliaro F (2019) Worldwide research trends on sustainable land use in agriculture. Land Use Policy 87:104069

Balasubramaniam C (2012) Non-performing assets and profitability of commercial banks in India: assessment and emerging issues. Nat Mon Refereed J Res Commer Manag 1(1):41–52

Barra C, Zotti R (2017) On the relationship between bank market concentration and stability of financial institutions: evidence from the Italian banking sector, MPRA working Paper No 79900. Last Accessed on Jan 2021 https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/79900/1/MPRA_paper_79900.pdf

Barth JR, Caprio G, Levine R (2004) Bank regulation and supervision: what works best? J Financ Intermed 2(13):205–248

Barth JR, Caprio G, Levine R (2008) Bank regulations are changing: For better or worse? Comp Econ Stud 50(4):537–563

Barth JR, Dopico LG, Nolle DE, Wilcox JA (2002) Bank safety and soundness and the structure of bank supervision: a cross-country analysis. Int Rev Financ 3(3–4):163–188

Bartolini M, Bottani E, Grosse EH (2019) Green warehousing: systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. J Clean Prod 226:242–258

Baselga-Pascual L, Trujillo-Ponce A, Cardone-Riportella C (2015) Factors influencing bank risk in Europe: evidence from the financial crisis. N Am J Econ Financ 34(1):138–166

Beck T, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Levine R (2006) Bank concentration, competition, and crises: first results. J Bank Financ 30(5):1581–1603

Berger AN, Demsetz RS, Strahan PE (1999) The consolidation of the financial services industry: causes, consequences, and implications for the future. J Bank Financ 23(2–4):135–194

Berger AN, Deyoung R (1997) Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. J Bank Financ 21(6):849–870

Berger AN, Udell GF (1998) The economics of small business finance: the roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle. J Bank Financ 22(6–8):613–673

Berger AN, Udell GF (2002) Small business credit availability and relationship lending: the importance of bank organisational structure. Econ J 112(477):F32–F53

Berger AN, Udell GF (2006) A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. J Bank Financ 30(11):2945–2966

Besanko D, Kanatas G (1996) The regulation of bank capital: Do capital standards promote bank safety? J Financ Intermed 5(2):160–183

Beyer A, Cohen DA, Lys TZ, Walther BR (2010) The financial reporting environment: review of the recent literature. J Acc Econ 50(2–3):296–343

Bikker JA (2010) Measuring performance of banks: an assessment. J Appl Bus Econ 11(4):141–159

Bolt W, Tieman AF (2004) Banking competition, risk and regulation. Scand J Econ 106(4):783–804

Boudriga A, BoulilaTaktak N, Jellouli S (2009) Banking supervision and non-performing loans: a cross-country analysis. J Financ Econ Policy 1(4):286–318

Bouzon M, Miguel PAC, Rodriguez CMT (2014) Managing end of life products: a review of the literature on reverse logistics in Brazil. Manag Environ Qual Int J 25(5):564–584. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEQ-04-2013-0027

Article Google Scholar

Boyd JH, De Nicolo G (2005) The theory of bank risk taking and competition revisited. J Financ 60(3):1329–1343

Brealey RA, Myers SC, Allen F, Mohanty P (2012) Principles of corporate finance. Tata McGraw-Hill Education

Buston CS (2016) Active risk management and banking stability. J Bank Financ 72:S203–S215

Casu B, Girardone C (2006) Bank competition, concentration and efficiency in the single European market. Manch Sch 74(4):441–468

Charumathi B, Ramesh L (2020) Impact of voluntary disclosure on valuation of firms: evidence from Indian companies. Vision 24(2):194–203

Chen X (2007) Banking deregulation and credit risk: evidence from the EU. J Financ Stab 2(4):356–390

Chen H-J, Lin K-T (2016) How do banks make the trade-offs among risks? The role of corporate governance. J Bank Financ 72(1):S39–S69

Chen M, Wu J, Jeon BN, Wang R (2017) Do foreign banks take more risk? Evidence from emerging economies. J Bank Financ 82(1):20–39

Claessens S, Laeven L (2003) Financial development, property rights, and growth. J Financ 58(6):2401–2436. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6261.2003.00610.x

Claessens S, Laeven L (2004) What drives bank competition? Some international evidence. J Money Credit Bank 36(3):563–583

Cnaan RA, Moodithaya M, Handy F (2012) Financial inclusion: lessons from rural South India. J Soc Policy 41(1):183–205

Core JE, Holthausen RW, Larcker DF (1999) Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. J Financ Econ 51(3):371–406

Dahir AM, Mahat FB, Ali NAB (2018) Funding liquidity risk and bank risk-taking in BRICS countries: an application of system GMM approach. Int J Emerg Mark 13(1):231–248

Dechow P, Ge W, Schrand C (2010) Understanding earnings quality: a review of the proxies, their determinants, and their consequences. J Acc Econ 50(2–3):344–401

Delis MD, Molyneux P, Pasiouras F (2011) Regulations and productivity growth in banking: evidence from transition economies. J Money Credit Bank 43(4):735–764

Demirguc-Kunt A, Laeven L, Levine R (2003) Regulations, market structure, institutions, and the cost of financial intermediation (No. w9890). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Deyoung R, Jang KY (2016) Do banks actively manage their liquidity? J Bank Financ 66:143–161

Ding Y, Cronin B (2011) Popularand/orprestigious? Measures of scholarly esteem. Inf Process Manag 47(1):80–96

Eastburn RW, Sharland A (2017) Risk management and managerial mindset. J Risk Financ 18(1):21–47

Erfani GR, Vasigh B (2018) The impact of the global financial crisis on profitability of the banking industry: a comparative analysis. Economies 6(4):66

Erkens DH, Hung M, Matos P (2012) Corporate governance in the 2007–2008 financial crisis: evidence from financial institutions worldwide. J Corp Finan 18(2):389–411

Fahimnia B, Sarkis J, Davarzani H (2015) Green supply chain management: a review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Prod Econ 162:101–114

Financial Stability Report (2019) Financial stability report (20), December 2019. https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=946 Accesses on March 2020

Fink A (2005) Conducting Research Literature Reviews:From the Internet to Paper, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications

Ghosh A (2015) Banking-industry specific and regional economic determinants of non-performing loans: evidence from US states. J Financ Stab 20:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2015.08.004

Gonzalez F (2005) Bank regulation and risk-taking incentives: an international comparison of bank risk. J Bank Financ 29(5):1153–1184

Goyal K, Kumar S (2021) Financial literacy: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int J Consum Stud 45(1):80–105

Grassa R, Moumen N, Hussainey K (2020) Do ownership structures affect risk disclosure in Islamic banks? International evidence. J Financ Rep Acc 19(3):369–391

Haque F, Shahid R (2016) Ownership, risk-taking and performance of banks in emerging economies: evidence from India. J Financ Econ Policy 8(3):282–297

Hellmann TF, Murdock KC, Stiglitz JE (2000) Liberalization, moral hazard in banking, and prudential regulation: Are capital requirements enough? Am Econ Rev 90(1):147–165

Hirshleifer D (2001) Investor psychology and asset pricing. J Financ 56(4):1533–1597

Huang J, You JX, Liu HC, Song MS (2020) Failure mode and effect analysis improvement: a systematic literature review and future research agenda. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 199:106885

Ibáñez Zapata A (2017) Bibliometric analysis of the regulatory compliance function within the banking sector (Doctoral dissertation). Last Accessed on Jan 2021 https://riunet.upv.es/bitstream/handle/10251/85952/Bibliometric%20analysis_AIZ_v4.pdf?sequence=1

Ibrahim MS (2010) Performance evaluation of regional rural banks in India. Int Bus Res 3(4):203–211

Jayadev M, Singh H, Kumar P (2017) Small finance banks: challenges. IIMB Manag Rev 29(4):311–325

Jin JY, Kanagaretnam K, Lobo GJ, Mathieu R (2013) Impact of FDICIA internal controls on bank risk taking. J Bank Financ 37(2):614–624

Joshi MK (2020) Financial performance analysis of select Indian Public Sector Banks using Altman’s Z-Score model. SMART J Bus Manag Stud 16(2):74–87

Kanoujiya J, Bhimavarapu VM, Rastogi S (2021) Banks in India: a balancing act between profitability, regulation and NPA. Vision, 09722629211034417

Karyani E, Dewo SA, Santoso W, Frensidy B (2020) Risk governance and bank profitability in ASEAN-5: a comparative and empirical study. Int J Emerg Mark 15(5):949–969