- Open access

- Published: 20 October 2023

Relationship between career maturity, psychological separation, and occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates: moderating effect of registered residence type

- Jianchao Ni 1 ,

- Jiawen Zhang 2 , 3 ,

- Yumei Wang 4 ,

- Dongchen Li 5 &

- Chunmei Chen 6

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 246 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1899 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

With the slowdown of economic growth and the increasing pressure of employment competition worldwide during the normalized epidemic prevention and control, the job-hunting intention and behavior of college graduates deserve in-depth study. This study explores the relationship between the career maturity, psychological separation and occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates, and provides a theoretical basis for improving their career maturity.

A questionnaire survey was carried out on postgraduates with 584 valid data in China by using the Career Maturity Scale, Psychological Separation Scale and the Occupational Self-efficacy Scale. A structural equation model and bias-corrected self-sampling method were adopted to explore their relationship. The moderating effect of registered residence type was tested.

The results show that: (1) The higher the level of psychological separation of postgraduates, the higher their career maturity. (2) Occupational self-efficacy plays a mediating role in the process of psychological separation promoting career maturity. (3) The registered residence type moderates the latter half of the mediating process of psychological separation, occupational self-efficacy, and career maturity. Moreover, occupational self-efficacy plays a more significant role in promoting the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence.

Conclusions

This study reveals the relationship between the career maturity, psychological separation and occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates. At the same time, it also verifies the mediating role of occupational self-efficacy and the moderating role of registered residence type. The result is helpful for postgraduates to understand the level of their career maturity and improve their career decision-making level and career development ability.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The employment of college graduates is related to people’s well-being, social stability and high-quality development. It is also an important indicator to measure the quality of talent training in colleges and universities. Career maturity, initially proposed by career guidance expert Super in the 1950s (Super, 1953), is a crucial evaluative indicator for assessing individual career development [ 1 ]. He defines career maturity as the psychological, social and physical readiness of young people to choose a career (Super, 1981) [ 2 ]. Building upon Super’s research, Crites (1978) puts forward a more mature theory on the basis of Super’s research [ 3 ]. He holds that career maturity could be used to represent the degree of individual career development and the state of preparation for making career choices. Its key factor is to have clear, rational and correct career goal design and career planning. Furthermore, Kleine et al. (2021) emphasize that career maturity refers to the ability to independently and responsibly make career decisions based on integrating oneself and the work environment [ 4 ]. In this view, career maturity represents not only the individual’s preparedness to choose a career but also their capacity to navigate and adapt to the complexities and dynamics of the work world. By integrating Super’s foundational work, Crites’ emphasis on career development, and Kleine expanded perspective on decision-making and integration, a comprehensive understanding of career maturity emerges. It encompasses the psychological, social, and physical readiness to select a career, the level of an individual's career development and preparedness for decision-making, and the ability to make autonomous and responsible career choices while integrating oneself with the work environment.

Various scholars have conducted in-depth research on career maturity. Scholars find that career maturity has a great impact on the selection of individual positions, and it is the key factor to measure college students’ employment success (Ju & Shin, 2020; Zhang et al., 2018) [ 5 , 6 ]. Tong Huijie’ (2013) studies show that career maturity could predict the probability of an individual successfully obtaining a position [ 7 ]. Moreover, it could effectively predict the job adaptation and job performance of newly recruited college students. The higher the career maturity, the easier it is for an individual to make a suitable career choice, which is correspondingly more conducive to the individual’s career success (Liu Hongxia, 2009) [ 8 ]. In addition, research has supported the idea that self-concept seems to have an effect on career maturity (Greenhaus, 1971) [ 9 ]. Helbing (1984) holds that career maturity is correlated with work orientation and a sense of personal identity [ 10 ]. Dillard (1976) indicates that the relationships between career maturity and self-concepts are relatively weak-positive [ 11 ]. Shelley (1977) concludes that as to the relationship between self-concept, self-actualization and career maturity, a positive self-concept is necessary [ 12 ].

At present, the research on career maturity mainly focuses on undergraduates. There is little research on graduate students, especially postgraduates. Compared with undergraduates, postgraduates have different psychological development and major contradiction in life. They have received a deeper level of higher education and more systematic learning and understanding of professional knowledge. Therefore, the structure, as well as the development characteristics of their career maturity might be different. Therefore, the career maturity of this group has potential value for further research. According to the “National Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Education” issued by China’s Ministry of Education, the country’s graduate enrollment has risen year by year in the past three years. Therefore, the scarcity and competitive advantage of a master’s degree in the job market is gradually decreasing, and the employment pressure they face is gradually increasing. Nowadays, the overall employment market of postgraduates has presented problems such as the mismatch between professional ability and quality with the requirements of employers, mismatch of disciplines and majors with emerging industries, unsynchronized job search and recruitment of employers, and gaps between traditional employment concepts and employment requirements in the new era (Li Jian, 2020) [ 13 ]. Some postgraduates have high expectations of salary and benefits, and are easily affected by the psychological impact of “Being unfit for a higher post but unwilling to take a lower one”, and their professional ability and as well as self-evaluation are prone to deviations, that is, some postgraduates have not yet reached their due level of career maturity. Therefore, it is important to explore the characteristics and influencing factors of postgraduates’ career maturity.

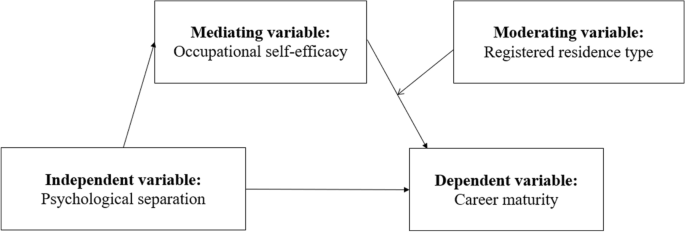

The factors that affect individual career maturity mainly include individual psychology factors (such as psychological separation, career efficacy, etc.) (Lv Aiqin et al., 2008) [ 14 ], family background factors (such as parental occupation type, family economic status, etc.) (Sun & You, 2019; Puebla, 2022) [ 15 , 16 ] and social characteristics factors (such as gender, age, registered residence, etc.) (Bae, 2017; Park & Jun, 2017) [ 17 , 18 ]. Lee & Hughey (2001) hold that a large part of the healthy development of occupation depends on the degree of psychological separation between individuals and their parents [ 19 ]. They believe that psychological separation has an important impact on career maturity. Patton et al. (2005) hold that career efficacy might affect career maturity [ 20 ]. Then, how does psychological separation affect career maturity through occupational self-efficacy? To this end, this study introduced the variable related to family factors “psychological separation”, the variable related to individual psychological factors “occupational self-efficacy”, the variable related to social characteristics factors “registered residence type”. Postgraduates are selected as the research object, and career maturity is taken as an indicator to measure the willingness and ability of personal career development. The mechanism of psychological separation, and occupational self-efficacy on postgraduates’ career maturity was discussed. The mediating effect of occupational self-efficacy and the moderating effect of registered residence registration type were clarified.

Theoretical hypotheses

Career maturity, psychological separation, and occupational self-efficacy.

Super formally put forward the concept of career maturity. Career maturity is now at the center of career counseling and education programs in various schools, as well as being incorporated into many business, industry, and government career development programs. Career maturity is also the most commonly used outcome measure in career counseling and is widely used internationally. With the continuous development of career maturity theory, multinational researchers led by Crites, Savickas and Westbrook have discussed career maturity from different perspectives and accumulated a series of research results. Although there are various categories of career maturity nowadays, it can be generally classified into the following three points: Firstly, almost all scholars recognize the dynamic nature of career development and believe that it is a process of continuous development and advancement. Secondly, scholars’ definition of career maturity pays attention to the role of individual cognitive ability on career maturity. Third, the definition of career maturity emphasizes the individual's subjective initiative in the process of career development. This study is based on Crites’ definition of career maturity. Crites comprehensively summarizes the structure of career maturity and helps people understand their stage and development tasks in the career development process. Individuals’ career maturity is closely related to the family environment. Vondracek et al. (1986) hold that if there is variable that can predict an individual’s occupational status, this variable is the socioeconomic status of the individual’s original family [ 21 ]. Individuals’ career maturity is not only affected by the intergenerational transmission of family status, but also by the relationship with parents. The degree of individual separation from parental dependence, that is, psychological separation, will significantly affect their career maturity, which in turn affects their occupational development level (Lee & Hughey, 2001) [ 19 ]. The higher the degree of separation between adolescents and their original families, the higher the individuals’ sense of professional competence (Frank et al., 1988) [ 22 ]. Son Hyun Sook (2009) explores the relationship between career maturity and psychological separation [ 23 ]. He finds that the higher the level of individual maternal psychological separation, the higher the level of career maturity. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H1: The psychological separation of postgraduates is positively related to their career maturity.

Individuals’ career maturity is also affected by individuals’ career psychological factors, of which the influence of occupational self-efficacy is particularly prominent (Hazel, 2022) [ 24 ]. Bandura (1977) proposes a theory of self-efficacy to explain the reasons for people’s motivation in certain situations [ 25 ]. Spencer & Bandura (1987) believe that self-efficacy is individuals’ assessment of the degree of confidence in one's ability to complete a task. The results of the assessment will affect their subsequent motivations and choices [ 26 ]. Taylor & Betz (1983) propose career decision-making self-efficacy on the basis of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory [ 27 ]. They believe that career decision-making self-efficacy refers to the self-evaluation or confidence of decision-makers in the process of career decision-making in their ability to complete various tasks. Hou Chunna et al. (2013) show that sound and independent personality development (such as a sense of responsibility) would affect the development level of individual college students. This makes them have higher self-efficacy, which could be reflected in the face of career decision-making for occupational self-efficacy [ 28 ]. The “Social Cognitive Career Theory” proposed by Song & Chon (2012) suggests that the career maturity of individuals might be related to their occupational self-efficacy [ 29 ]. Individuals with high occupational self-efficacy tend to have positive expectations for their career development. This positive expectation will drive them to take measures to meet various challenges in their career. Individuals with high occupational self-efficacy have clearer career goals and are more active in exploring career self, career information and career planning (Du Rui, 2006) [ 30 ]. Empirical research also proves that occupational self-efficacy is positively related to career maturity (Abdullah, 2023) [ 31 ]. YongHee & HyunSoon (2019) show that self-encouragement and occupational self-efficacy play a complete mediating role in the relationship between adolescent peer attachment and career maturity [ 32 ]. Kim Daeyoung & Joeng Ju ri. (2018) show the mediating role of career decision-making self-efficacy between parents’ active learning participation and career maturity [ 33 ]. Zhang Hua (2008) shows that the success of the psychological separation process would also help individuals to establish independence and autonomy, and get rid of parental attachment [ 34 ]. Therefore, individuals are more likely to obtain successful experiences, a positive psychological state, a positive external environment of trust, resulting in strong self-efficacy. The positive attitude of actively pursuing success is conducive to the development of a higher sense of career choice efficacy (Ye Baojuan et al., 2020) [ 35 ]. The success of the individualization process after psychological separation is conducive to the formation of healthy occupational psychology. Positive occupational psychology is also the driving force for career maturity. Good occupational self-efficacy plays a catalytic role. Combined with the above discussion, we infer that occupational self-efficacy might be the key factor linking the psychological separation and career maturity of postgraduates. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H2: Occupational self-efficacy mediates the positive relationship between psychological separation and career maturity.

The moderating effect of registered residence type

In most countries, registered residence registration is mainly used to register the change of residence. The difference between urban and rural registered residence only exists as the difference of residence. The registered residence system is unique in China, since China implements a dual registered residence system in urban and rural areas, which links individual registered residence with specific regions, and divides registered residence into urban and rural types. The original purpose of the system was to restrict the cross-regional mobility of residents. In the long-term development, the residence registration system not only plays the role of registered residence management, but also affects various aspects of society, such as the occupation, medical care, education and social security of residents (Li Zhenjing&Zhang Linshan, 2014) [ 36 ]. The differences of registered residence have different impacts on public resources and social welfare (Jiancai Pi & Pengqing Zhang, 2016) [ 37 ]. With the rapid development of the economy in China, there are more differences in economic conditions and resource allocation among different regions. Due to the different household registered residence types of individuals, the external differences in the region tend to have influence on their career awareness, career knowledge and career attitude. Therefore, individual career maturity might have different performances in urban and rural samples. The research results around the differences in career maturity between urban and rural areas have drawn different conclusions. Chinese scholars Jia Pengfei & Chen Zhenbang (2011) find that there is no significant difference between urban and rural sources of college students’ career maturity [ 38 ]. Scholars in other counties generally believe that the career maturity of students is affected by their registered residence. Research by Alam (2016) shows that there are significant differences in career maturity between rural and urban students [ 39 ]. Junga & Yuntae (2015) find that adolescents living in cities tend to have higher career maturity. Adolescents living in rural areas have lower career maturity due to a lack of relevant social support [ 40 ]. Vibha & Ushakiran (2016) measure the career maturity of adolescents and find that the career maturity score of urban adolescents is higher than that of rural samples [ 41 ]. In addition, there are differences between urban and rural areas in individual occupational self-efficacy. The research of Conceicao et al. (2016) shows that there are significant differences between rural and urban teachers’ occupational self-efficacy [ 42 ]. Casapulla (2017) finds that in the process of participating in urban and rural services, students’ self-efficacy in providing vocational services in urban and rural areas is affected by their type of residence [ 43 ]. Students in different places of residence showed different self-efficacy in this process. To sum up, we believe that differences in registered residence attributes bring about different performances of postgraduates’ occupational self-efficacy and career maturity. The relationship between postgraduates’ occupational self-efficacy and career maturity is affected by registered residence attributes. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis H3: Registered residence type moderates the positive relationship between occupational self-efficacy and career maturity, and such relationship is stronger in rural registered residence rather than in urban registered residence.

To sum up, this study aims to study the relationship between the career maturity, psychological separation and occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates, and examine the mediating role of occupational self-efficacy and the moderating role of the registered residence type. The hypothesis model is shown in Fig. 1 .

Hypothetical model of the mediating effect of occupational self-efficacy and the moderating effect of registered residence type

Data collection

On the basis of ensuring the scientific design of the survey, considering the feasibility of the design and the principle of economy and effectiveness, this study adopts the convenient sampling method. Samples are taken from easily available subjects. This method is fast, simple, easy to obtain and cost-effective (Henry, 1990) [ 44 ]. By this method, a survey of postgraduates from different regions and levels of universities in China such as Xiamen University, Guangxi University (the source universities are widely distributed) was carried out and 600 questionnaires were collected by our research team. The questionnaire was mainly a paper version, supplemented by an electronic version, and data were collected synchronously through a combination of online and offline. The online questionnaire is distributed by using the website of Wenjuanxing ( https://www.wjx.cn/ ) to forward the questionnaire to the group and invite students to fill in the form of red packets. The offline questionnaire is distributed by giving small gifts to students. After sorting, 584 valid questionnaires were finally obtained, 16 invalid questionnaires with characteristics such as short filling time, missing data, and suspected insincere answers were excluded, and the effective recovery rate of the questionnaire was 97.33%. The study is only a questionnaire survey and does not involve human clinical trials or animal experiments, which conforms to ethical standards.

Research tools

Career maturity scale.

The master graduates’ career maturity questionnaire was used to measure the postgraduates’ career maturity (Wang Yumei, 2020) [ 45 ]. 18 typical items (with the sample items such as: “I know what kind of work I like”, “I can describe the main work contents of the occupation I am interested in” etc.) were selected to measure the career choice ability, career choice attitude, career choice knowledge of postgraduates, aiming to reflect the various abilities of postgraduates in the process of career choice. The 18 questions were graded on a 4-point scale: "1 = very inconsistent", "2 = relatively inconsistent", "3 = relatively consistent", and "4 = very consistent". The higher the score, the higher the degree of agreement. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on the scale, and the fitting index parameters were obtained as follows: χ 2 /df (ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom) = 2.361, CFI (Comparative Fit Index) = 0.972, IFI (Incremental Fit Index) = 0.972, GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) = 0.952, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) = 0.048. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.943, which showed good consistency and the measurement results were valid. The 18 items were summed up and averaged to obtain the variable of career maturity, which was used to represent the career maturity of postgraduates. The higher the score, the higher the degree of career maturity.

Psychological separation scale

The psychological separation questionnaire was used to measure the degree of psychological separation of postgraduates (Wu Huiqing, 2012) [ 46 ]. This questionnaire has been used and proved to be effective. Although this questionnaire is designed for undergraduates’ psychological separation, psychological separation is a relatively stable concept, which is applicable to people of different ages and different educational levels. Both undergraduates and postgraduates are in a relatively similar environment, facing similar pressures and challenges. And currently, there are no other psychological separation scales more suitable for postgraduates. Therefore, this questionnaire still has reference value in measuring the psychological separation of postgraduates. In a practical study, selecting all the items might lead to the scale being too long, increasing the time, cognitive burden and discomfort of the subjects, thus affecting the quality of their responses. Some questions are less difficult or lack differentiation. Therefore, on the premise of ensuring the reliability and validity of the measurement, eliminating some items can improve the differentiation of the scale. In this study, a total of 8 typical items (with the sample items such as: “I feel especially in need of comfort when I encounter setbacks”, “I seek support when making decisions or plans” etc.) were selected from emotion separation, attitude separation and behavior separation respectively, and the corresponding items could effectively reflect the concept to be measured, help to improve the validity of the scale and reduce measurement errors. Each question adopted a 4-point scale: "1 = very inconsistent", "2 = relatively inconsistent", "3 = relatively consistent", and "4 = very consistent". The higher the score, the higher the degree of agreement. The CFA was performed on the scale, and the parameters were obtained as follows: χ 2 /df = 1.419, CFI = 0.997, IFI = 0.997, GFI = 0.993, RMSEA = 0.027. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.869, which showed good consistency and the measurement results were valid. The 8 items were summed up and averaged to obtain the variable of psychological separation, which was used to represent the degree of psychological separation of postgraduates. The higher the score, the higher the degree of psychological separation.

Occupational self-efficacy scale

The occupational self-efficacy scale was used to measure the occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates (Schyns & Collani, 2002) [ 47 ]. According to the actual situation of postgraduates in China, 9 typical items (with the sample items such as: “I have a way of getting what I want even if others are against me”, “It's easy for me to stick to my ideals and achieve my goals” etc.) were finally retained to measure the degree of self-confidence of postgraduates in completing corresponding professional behaviors and achieving career goals. The 9 questions were graded on a 4-point scale: "1 = very inconsistent", "2 = relatively inconsistent", "3 = relatively consistent", and "4 = very consistent". The higher the score, the higher the degree of agreement. The CFA was performed on the scale, and the parameters were obtained as follows: χ 2 /df = 1.345, CFI = 0.998, IFI = 0.998, GFI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.024. The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.901, which showed good consistency and the measurement results were valid. The 9 items were summed up and averaged to obtain the variable of occupational self-efficacy, which was used to represent the degree of the occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates. The higher the score, the higher the degree of occupational self-efficacy.

Statistical analysis

Consideration was given to the possibility of common method bias arising from the use of self-report data collection. Therefore, the procedure of this study was controlled by an anonymous survey and reverse scoring of some questions. At the same time, Harman’s single-factor test was used to test the data for common method bias. The results showed that there were 4 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the total variance explained by the first common factor was 35.63%, which was less than the critical value of 40%. Therefore, the data in this study did not have the problem of common method bias (Zhou Hao&Long Lirong, 2004) [ 48 ]. SPSS26.0 was used for reliability analysis, confirmatory factor analysis and correlation analysis. The macro PROCESS of SPSS procedure was used to test the hypothesis of the moderated mediation model.

Research results

The basic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 . The distribution of samples in demographic variables is relatively balanced, showing good representativeness.

Correlation analysis between main variables

Correlation analysis was carried out on the main variables for the career maturity, occupational self-efficacy and psychological separation. Considering that the main variables were continuous, the Pearson correlation coefficient test was used. The results in Table 2 showed that the psychological separation, occupational self-efficacy and career maturity were positively correlated. Psychological separation was positively correlated with occupational self-efficacy ( r = 0.26, p < 0.01), and positively correlated with career maturity ( r = 0.19, p < 0.01). Occupational self-efficacy was positively correlated with career maturity ( r = 0.67, p < 0.01).

The relationship between psychological separation and career maturity: a moderated mediation test

The test of the research hypothesis refers to the procedure of Wen Zhonglin’s moderated mediation test (Wen Zhonglin, 2014) [ 49 ]. The mediation model is constructed and the moderating variables are introduced to explore the model. According to this judgment standard, this section examines the moderating effect of registered residence type on the mediating process of "psychological separation, occupational self-efficacy, and career maturity". Control variables such as major, whether the only child and gender type were virtualized.

Firstly, the mediating effect of occupational self-efficacy between psychological separation and career maturity was tested under the control of major, whether the only child and gender type. The specific results were shown in Table 3 below. The results showed that psychological separation had a significant promoting effect on career maturity (β = 0.195, t = 4.721, p < 0.001), which passed the 99.9% significance level test, Therefore, hypothesis 1 was supported. Psychological separation also had a promoting effect on occupational self-efficacy (β = 0.26, t = 6.410, p < 0.001), which also passed the 99.9% significance level test. Referring to the idea of Wen Zhonglin’s mediation effect test, it can be considered that occupational self-efficacy played a mediating role between psychological separation and career maturity. It was a complete mediator, that was, the proportion of the mediation effect was 100%. Therefore, occupational self-efficacy mediated the relationship between psychological separation and career maturity, and Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Secondly, in order to further verify the mediating effect of occupational self-efficacy, the bootstrap sampling method (1000 times of sampling) was adopted to obtain the bootstrap test results of the mediating effect, which were arranged in Table 4 below. The results showed that the 95% confidence interval of the indirect effect did not contain 0, and the 95% confidence interval of the direct effect contained 0, that was, the indirect effect existed, the direct effect did not exist, and the occupational self-efficacy played a complete mediating role.

Again, model 14 in the macro PROCESS of SPSS plug-in compiled by Hayes (2012) (model 14 assumes that the second half of the indirect effect in the mediation model is moderated, which is in line with our hypothesis expectations) is used. Hayes developed the plugin PROCESS based on SPSS for mediating and moderating effect analysis. Process is a plug-in that specializes in mediating and moderating effects analysis, providing more than 70 models, the analysis process needs to select the corresponding model, set the corresponding independent variables, dependent variables, mediating or moderating variables, which can facilitate the operation and analysis of mediation models, moderated mediation models, etc. The moderating effect of registered residence type was tested under the control of major, whether the only child and gender, and the following Table 5 was obtained. The results showed that psychological separation significantly promoted occupational self-efficacy (β = 0.260, t = 6.410, p < 0.001), and occupational self-efficacy significantly promoted career maturity (β = 0.771, t = 17.655, p < 0.001). The complete mediation of occupational self-efficacy between psychological separation and career maturity was still valid. There was a positive relationship between registered residence type and career maturity (β = 0.113, t = 1.696, p < 0.1), and the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence was higher than that of postgraduates with urban registered residence. The interaction item of occupational self-efficacy and registered residence type was significant in the model (β = -0.209, t = -3.42, p < 0.001), that was, the interaction item between occupational self-efficacy and registered residence type could significantly affect career maturity. Therefore, registered residence type moderated the relationship between occupational self-efficacy and career maturity.

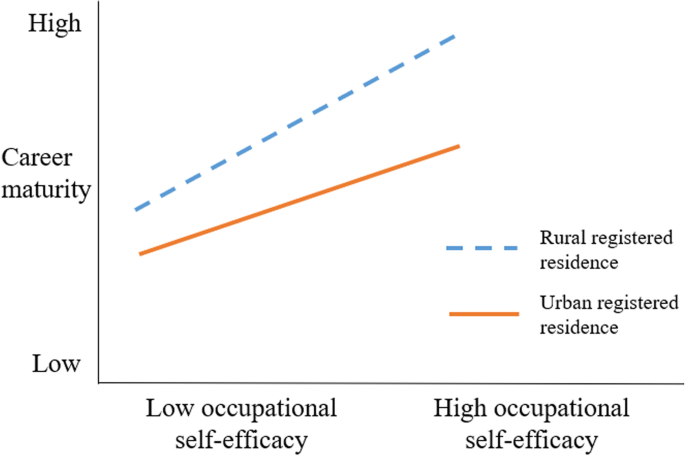

Finally, in order to more vividly interpret the moderating effect of registered residence type on occupational self-efficacy and career maturity, the research subjects were grouped according to registered residence type. A simple slope test was performed to obtain Fig. 2 below. The results showed that occupational self-efficacy played a positive role in promoting the career maturity of postgraduates (all slopes were greater than 0). In general, at all stages of occupational self-efficacy, the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence was higher than that of postgraduates with urban registered residence. With the rise of occupational self-efficacy, the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence increased faster. In fact, the rate of career maturity improvement of postgraduates with urban registered residence was slower than that of postgraduates with rural registered residence. This indicates that the occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates with rural registered residence had a stronger role in promoting their career maturity. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

The moderating effect of registered residence type on occupational self-efficacy and career maturity

In this study, we constructed and tested a moderated mediation model to examine the moderating effect of registered residence type on the mediating process of “psychological separation, occupational self-efficacy, and career maturity”. The results showed that the moderating variable “registered residence type” had a significant moderating effect on the mediating path.

Firstly, the results of correlation analysis and structural equation analysis proved that the positive effect of psychological separation on career maturity was significant and robust. This is consistent with previous research results. Previous studies showed that there was a close relationship between psychological separation and career maturity. Lopez & Andrews (2014) found that the degree of separation between children and families had a significant impact on individuals’ career decision-making, and a better level of psychological separation might reduce the difficulty of individuals’ career decision-making [ 50 ]. Zhang Xinyong et al. (2014) pointed out in their research that the more able an individual was to take responsibility in the event of a conflict with parents, the higher their level of career maturity [ 51 ]. Therefore, college educators or psychological consultants should focus on strengthening the psychological counseling work for postgraduates. Guide them to achieve emotional, attitude and behavioral independence on the premise of maintaining emotional contact with their parents, and promoting their career maturity.

Secondly, the results of the mediation effect test showed that psychological separation not only directly promoted the career maturity of postgraduates, but also promoted the occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates. Moreover, it could indirectly affect career maturity through occupational self-efficacy. Occupational self-efficacy played a completely mediating role between psychological separation and career maturity. This was consistent with the previous studies. The research of Kang & Hyun-Wook (2016) showed that psychological separation had a positive effect on individuals’ occupational self-efficacy[ 52 ]. Chen Yuaner & Ma Xiaoqin (2016) found that the two dimensions of occupational self-efficacy, occupational cognition and occupational value, had a positive role in promoting career maturity [ 53 ]. Gao Shanchuan & Sun Shijin (2005) found that the influence of occupational self-efficacy on individual career maturity was not only reflected in a direct role, but also played an indirect role [ 54 ]. The research of Liu Yang et al. (2022) on the career maturity of college students showed that occupational self-efficacy played a mediating role between their craftsman psychology and career maturity, that was, craftsman psychology could indirectly predict career maturity through occupational self-efficacy [ 55 ]. Psychological separation could positively promote career maturity, but there were various factors that affect career maturity, such as occupational self-efficacy, and career maturity was a dynamic change process (Betz et al., 1981) [ 56 ]. Occupational self-efficacy could help individuals achieve more positive results in the process of job hunting. Specifically, individuals with high occupational self-efficacy were more confident in achieving career goals. They could objectively and comprehensively conduct self-analysis and evaluation, and have a more objective understanding of their personality traits, abilities, interests, etc. (Li Zhengwei et al., 2010) [ 57 ]. In addition, they could position their career direction more accurately and their career goals were clearer (Ochs & Roessler, 2004) [ 58 ]. At the same time, they were usually more involved in the process of career selection, and were able to explore and learned more actively (Blustein, 1989) [ 59 ]. They collected occupational and industry information related to their career goals to have a more comprehensive understanding of professional knowledge and positions. They could timely understand and discover the needs and changes of the occupational environment (Qu Kejia et al., 2015) [ 60 ], flexibly respond to difficulties encountered in the process of career selection, and be willing to adjust the target appropriately according to the actual situation (Savickas et al., 2002) [ 61 ]. Therefore, individuals with high occupational self-efficacy would have more confidence in their careers, have more active job-seeking behaviors, have stronger career decision-making abilities, and have a higher level of career maturity. Colleges and universities could formulate scientific career planning courses according to the development law of occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates. Through cultivating good career self-efficacy of postgraduates, the career development level of postgraduates can be improved.

Finally, the moderated mediation effect test showed that registered residence type played a moderating role between occupational self-efficacy and career maturity. The results showed that the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence was higher than that of postgraduates with urban registered residence, which was consistent with the research results of He Weijie et al. (2022) [ 62 ]. However, the results are inconsistent with Junga & Yuntae (2015) [ 40 ], Vibha & Ushakiran (2016) [ 41 ]. Occupational self-efficacy not only played a positive role in promoting the career maturity of postgraduates, but also the magnitude of this effect varied among postgraduates with different registered residence types. Occupational self-efficacy had a more significant role in promoting the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence. With the rise of occupational self-efficacy, the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence increased faster than that of postgraduates with urban registered residence. The reason might be as follows: The long-term urban–rural dual policy in China has resulted in a social and economic imbalance between rural and urban areas. Due to the influence of the economy, family cultural structure, parental education methods, etc., compared with urban registered residence postgraduates, rural registered residence postgraduates are more likely to show insufficient confidence and inferiority. This also affects the career choice of urban and rural postgraduates to some extent. For example, rural registered residence postgraduates might reduce their career opportunities, and they are less likely to enter the government organs and state-owned enterprises, engage in elite occupations and obtain high-income industries than urban registered residence postgraduates. From the perspective of social capital, this phenomenon is directly related to the lack of social capital owned by rural registered residence postgraduates. Bourdieu Pierre (1980) holds that social capital means that when a person has a certain kind of lasting relationship network, the relationship network composed of people who are familiar with each other means the resources he or she actually or potentially owns [ 63 ]. Yu Hui & Hu Zixiang (2019) believe that young people’s career choice is also influenced by strong relational social capital, especially strong relational capital of talent [ 64 ]. Individuals with better family conditions often rely on strong family social relationship capital to obtain employment opportunities. However, strong family social relationship capital will gradually develop into weak relationships over time, while individual social capital will gradually show strong relationship over time. Most urban registered residence postgraduates have better social capital than rural registered residence postgraduates, this kind of social capital is mainly provided by the previous generation, which has been a fact. For rural registered residence postgraduates, the lack of abundant social capital makes them pay more attention to the accumulation of psychological capital, so they are more independent, hard-working, especially focus on the improvement of occupational self-efficacy, that is, they do not rely too much on the power of social capital. The belief in achieving career goals is an internal drive. Those rural registered residence postgraduates who have a strong belief in achieving career goals have a stronger motivation for career exploration and more career exploration behaviors. They are more fully prepared to collect career information and formulate career goals, and dare to face challenges in career development. They have a clear grasp of their professional abilities. Career maturity will also be higher. However, urban registered residence postgraduates are generally more confident because of their relatively favorable family environment and educational conditions. Their belief in achieving career goals has a weaker influence on their career maturity level. Therefore, occupational self-efficacy has a greater role in promoting the career maturity of rural registered residence postgraduates.

As research on career maturity mainly focuses on undergraduate students, there is little research on postgraduates. This study further enriches the research field of career maturity. Based on Crites’ career maturity theory, this paper uses occupational self-efficacy to explain the mechanism of psychological separation on career maturity, clarifies the logical relationship between postgraduates’ psychological separation and career maturity, and explores the mediating effect of occupational self-efficacy and the moderating effect of registered residence type. It further supplements and enriches the relevant theoretical research on career maturity, and provides theoretical support for the targeted career planning education of postgraduates, improving and enhancing the level of postgraduates’ career development. Meanwhile, this paper still has the following limitations: Firstly, this study uses cross-sectional data, so we couldn’t see the trend of time changes, and the impact of time effects on the conclusion is ignored. Secondly, due to the limitations of the questionnaire design, the measurement of some variables might not be precise enough to cover all aspects of the relevant concepts, and there might still be omissions. Third, limited by familiarity with the relevant topics, there might be omissions in the selection of control variables, which might have a certain impact on the research conclusions. Finally, although this paper uses a robust test mechanism for mediating and moderating effects, it fails to explore the causal mechanism in-depth and lacks the identification of causal relationships. Therefore, future related research can be improved from the following aspects: Firstly, expand the scope of the study, strive to include more types of schools as the sampling frame, and select the final sample by random sampling, so as to ensure a completely random data as much as possible and avoid bias in model estimation due to sampling error. Meanwhile, strive to collect data for the same sample for multiple years, so as to control the impact of time effects on the relevant variables of the sample, and obtain a more robust and reliable research conclusion. Secondly, improve the design of the questionnaire and strive to design a more realistic scale to ensure more accurate measurement. At the same time, increase the control variables in the questionnaire to include some demographic characteristics and social structure characteristics, so as to avoid the estimation error caused by various dependent variables. Third, improve the research method and use the model that can identify the causal mechanism to discuss the relationship between the research objects, so as to ensure that the obtained regression relationship is accurate and reliable.

The results show that: (1) Psychological separation has a significant positive effect on the occupational self-efficacy and career maturity of postgraduates. The higher the level of psychological separation, the higher the level of career maturity of postgraduates. Occupational self-efficacy also has a significant positive effect on the career maturity of postgraduates. (2) Occupational self-efficacy plays a complete mediating role between the psychological separation and career maturity of postgraduates. Psychological separation not only affects the career maturity of postgraduates directly, but also has an indirect effect on career maturity through occupational self-efficacy, and this indirect effect has a 100% mediating effect. (3) Registered residence type plays a moderating role between occupational self-efficacy and career maturity. Occupational self-efficacy not only has a positive predictive effect on the career maturity of postgraduates, but also the magnitude of this effect varies among postgraduates with different registered residence types. Occupational self-efficacy has a more significant role in promoting the career maturity of postgraduates with rural registered residence.

In summary, the level of career maturity not only reflects the employability of postgraduates, but also reflects their future career development, and is an important factor affecting the quality of postgraduate employment. The analysis of the characteristics and influencing mechanism of postgraduates’ career maturity will help postgraduates understand the level of their own career maturity, explore and plan their own career as early as possible, and improve their career decision-making level and career development ability. At the same time, it is also helpful for colleges and universities to provide more targeted employment guidance, improve the efficiency and effectiveness of counseling and guidance, and provide implementation direction for the improvement of postgraduates’ career maturity, so as to help postgraduates alleviate their employment anxiety and achieve high-quality employment.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Super DE. A theory of vocational development. Am Psychol. 1953;8(5):185–90.

Google Scholar

Super DE, Knasel EG. Career development in adulthood: some theoretical problems and a possible solution. Br J Guid Couns. 1981;9(2):194–201.

Crites JO. The career maturity inventory. Monterey, CA: California Test Bureau/McGraw-Hill; 1978.

Kleine AK, Schmitt A, Wisse B. Students’ career exploration: A meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 2021;131:103645.

Ju HK, Shin HS. Exploring barriers and facilitators for successful transition in new graduate nurses: a mixed methods study - sciencedirect. J Prof Nurs. 2020;36(6):560–8.

Zhang LY, Chen MR, Zeng XQ, Wang XQ. The relationship between professional identity and career maturity among pre-service kindergarten teachers: the mediating effect of learning engagement. Open J Soc Sci. 2018;6(6):167–86.

Huijie T, Xuan L. Empirical analysis of impact factors on undergraduate village offcials’ work adjustment. Stud Psychol Behav. 2013;11(6):813–8.

Hongxia L. A study on gender differences in the career maturity of college students. China Youth Stud. 2009;07:88–91.

Greenhaus J. Self esteem as an influence on occupational choice and occupational satisfaction. J Vocat Behav. 1971;1:75–83.

Helbing J. Vocational maturity, self-concepts and identity. Appl Psychol. 1984;33(3):335–50.

Dillard JM. Relationship between career maturity and self-concepts of suburban and urban middle- and urban lower-class preadolescent black males. J Vocat Behav. 1976;9(3):311–20.

Shelley NM. Self concept, self-actualization and career maturity. California State University Northridge. 1977.

Jian Li, Yayuan Li. Qualitative research on the employment concept structure of postgraduates. J Grad Educ. 2020;2:21–6.

Aiqin Lv, Mingji W, Han L, Junqi S. career maturity and emotional intelligence: the mediation effect of self-efficacy. Acta Scie Nat Univ Pekinensis. 2008;02:271–6.

Sun AL, You S. Long-term effect of parents’ support on adolescents’ career maturity. J Career Dev. 2019;46(1):48–61.

Puebla JN. Career decisions and dilemmas of senior high school students in disadvantaged schools: towards the development of a proposed career guidance program. Int J Multidiscip Appl Bus Educ Res. 2022;3(5):888–903.

Bae SM. An analysis of career maturity among Korean youths using latent growth modeling. Sch Psychol Int. 2017;38(4):434–49.

Park SH, Jun JS. Structural relationships among variables affecting elementary school students’ career preparation behavior: Using a multi-group structural equation approach. Int Electron J Elem Educ. 2017;10(2):273–80.

Lee HY, Hughey KF. The relationship of psychological separation and parental attachment to the career maturity of college. J Career Dev. 2001;27(4):279–93.

Patton W, Creed P, Spooner-Lane R. Validation of the short form of the career development inventory - australian version with a sample of university students. Aust J Career Dev. 2005;14(3):49–59.

Vondracek FW, Lerner RM, Schulenberg JE. Career development: a life-span developmental approach. 1986.

Frank SJ, Avery CB, Laman MS. Young adults’ perceptions of their relationships with their parents: Individual differences in connectedness, competence, and emotional autonomy. Dev Psychol. 1988;24(5):729–37.

Son Hyun Sook. The effect of psychological separation from mothers and self-concept on career maturity of high school students. Korean J Commun Living Sci. 2009;20(2):291–305.

Hazel DURU. Analysis of relationships between high school students’ career maturity, career decision-making self-efficacy, and career decision-making difficulties. Int J Psychol Educ Stud. 2022;9(1):63–78.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

PubMed Google Scholar

Cahill SE, Bandura A. social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Contemp Soc J Rev. 1987;16(1):12.

Taylor Karen M, Betz NE. Applications of self-efficacy theory to the understanding and treatment of career indecision. J Vocat Behav. 1983;22(1):63–81.

Hou Chunna Wu, Lin & Liu Zhijun. A Study on the mediated effect and moderated mediate effect of college students’ family factors parental emotional warmth, intellectual-cultural orientation and conscientiousness on career decision-making self efficacy. J Psychol Sci. 2013;01:103–8.

Song Z, Chon K. General self-efficacy’s effect on career choice goals via vocational interests and person–job fit: a mediation model. Int J Hosp Manag. 2012;31(3):798–808.

Du Rui. The research on career decision-making difficulty of the undergraduate students (Master’s thesis, Central China Normal University). 2006.

Abdullah SM. The meta-analysis study: career decision making self efficacy and career maturity. Insight: Jurnal Ilmiah Psikologi. 2023;25(1):01–16. http://ejurnal.mercubuana-yogya.ac.id/index.php/psikologi/article/view/3254 .

YongHee C, HyunSoon B. The mediating effects of self encouragement and career self efficacy between peer attachment and career maturity of adolescents’. Korean Assoc Learn Center Curric Instruct. 2019;19(9):537–55.

Kim Daeyoung and Joeng Ju ri. The relationships between parental positive academic involvement and elementary school students’ career maturity: mediating effects of academic self-efficacy and career decision-making self-efficacy. Asian J Educ. 2018;19(3):601–25.

Hua Z. Research on the self-efficacy of postgraduates’ career decision-making and its influencing factors. Ideol Theor Educ. 2008;03:78–82.

Baojuan Ye, Yuan S, Liang G, Fei X, Qiang Y. The relationship between proactive personality and college students’ career maturity: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Dev Educ. 2020;03:304–10.

Zhenjing Li, Linshan Zhang. Main problems and general ideas of China’s registered residence system reform. Macroecon Manage. 2014;03:23–6.

Pi J, Zhang P. Hukou system reforms and skilled-unskilled wage inequality in China. China Econ Rev. 2016;41:90–103.

Pengfei J, Zhenbang C. Investigation and research on the development characteristics of college students’ career maturity. Sci Technol Innov Herald. 2011;14:8–9.

Alam MM. Home environment and academic self-concept as predictors of career maturity. IRA Int J Educ Multidiscip Stud. 2016;4(3):359–72.

Junga Oh, Jung Y. School adaptation on career attitude maturity of middle school students: around the difference between urban and rural areas. Korean J Youth Stud. 2015;22(9):49–77.

Sahu Vibha Rani, Agarwal Ushakiran. Study of career maturity in urban and rural adolescents. Indian J Health Wellbeing. 2016;7(12):1124–6.

Almeida CM, et al. Urban and rural preservice special education teachers’ computer use and perceptions of self-efficacy. Rural Spec Educ Quart. 2016;35(3):12–9.

Casapulla SL. Self-efficacy of osteopathic medical students in a rural-urban underserved pathway program. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2017;117(9):577–85.

Henry GT. Practical sampling ([10. Nachdr.] edtn.). Newbury Park: sage publications. ISBN; 1990. p. 978–0803929586.

Yumei Wang. Construction of career maturity model for master’s graduates. J Yibin Univ. 2020;05:89–99+109.

Wu Huiqing. Questionnaire Compilation of Undergraduate Students’ Psychological Separation (Master's thesis, Northeast Normal University). 2012.

Schyns B, Von Collani G. A new occupational self-efficacy scale and its relation to personality constructs and organizational variables. Eur J Work Organ Psy. 2002;11(2):219–41.

Hao Z, Lirong L. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv Psychol Sci. 2004;06:942–50.

Zhonglin W, Baojuan Ye. Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv Psychol Sci. 2014;05:731–45.

Lopez FG, Andrews S. Career indecision: a family systems perspective. J Couns Dev. 2014;65(6):304–7.

Xinyong Z, Caijun L, Shiyun X. Career maturity of college students and its relationship with psychological separation. Psychol Res. 2014;01:80–4.

Kang and Hyun-Wook. verification relationship among psychological separation, career decision-making self-efficacy and career preparation for physical education high school students. J Sport Leisure Stud. 2016;66:471–81.

Yuaner C, Xiaoqin Ma. Study on correlation between occupation maturity and career self-efficacy of undergraduate nursing students. Chin Nurs Res. 2016;09:1070–3.

Shanchuan G, Shijin S. Social cognitive career theory: its research and applications. Psychol Sci. 2005;05:1263–5.

Yang L, Jie Li, Xiaomeng G, Xiaoxiao Z. Influence of craftsman psychology on career maturity of clinical medical students: the mediating role of career decision-making self-efficacy. Chin J Health Psychol. 2022;02:261–6.

Betz NE, Hackett G. The relationship of career-related self-efficacy expectations to perceived career options in college women and men. J Couns Psychol. 1981;28(5):399–410.

Li Zhengwei Fu, Jian Qiu Ying. the influencing factors of university students’ employment competitiveness: an empirical analysis. J Zhejiang Univ Technolo Soc Sci. 2010;01:30–5.

Ochs LA, Roessler RT. Predictors of career exploration intentions: a social cognitive career theory perspective. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2004;47(4):224–33.

Blustein DL. The Role of Career Exploration in the Career Decision Making of College Students. J Coll Stud Dev. 1989;30(2):111–7.

Qu Kejia Ju, Ruihua & Zhang Qingqing. The relationships among proactive personality, career decision-making self-efficacy and career exploration in college students. Psychol Dev Educ. 2015;04:445–50.

Savickas ML, Briddick WC, Watkins CE Jr. The relation of career maturity to personality type and social adjustment. J Career Assess. 2002;10(1):24–49.

He Weijie Hu, Chunmei Ge Ning. Influence of perceived social support on general normal college students’ career maturity: mediating role of professional identity. Adv Psychol. 2022;12(6):8.

Pierre B. Le. Capital social: notes provisoires. Act Rec Sci Soc. 1980;3:2–3.

Hui Yu, Zixiang Hu. Is it difficult to produce a noble son from a poor family? Qualitative research on youth Employment under the dual attribute of social capital. Chin Youth Res. 2019;12:7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants for their involvement in this study.

This study was the research results of the 2022 Annual Project of the Training and Training Center of College Ideological and Political Work Team of the Ministry of Education, PRC (Southwest Jiaotong University, SWJTUKF22-02), supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20720231076), the Research of the Young and Middle-aged Teachers' Educational Research Project (Social Science) of Fujian Provincial Education Department in 2021(JAS21710), the Research Initiation Fund of Jimei University (Q201907), Planning Project (FJ2021B211).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Education & School of Aerospace Engineering, Xiamen University, Xiamen, 361005, Fujian, China

Jianchao Ni

Silliman University, 6200, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental, Philippines

Jiawen Zhang

Xiamen Institute of Software Technology, Xiamen, 361024, Fujian, China

Institute of Education, Xiamen University, Xiamen, 361005, Fujian, China

National Immigration Administration, Beijing, 100741, China

Dongchen Li

Teachers College, Jimei University, Xiamen, Fujian, 361021, China

Chunmei Chen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NJ and WY designed the study and wrote the manuscript. LD, NJ and ZJ analyzed the data. CC, LD, ZJ and NJ modified the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Jiawen Zhang or Yumei Wang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is only a questionnaire survey and does not involve human clinical trials or animal experiments. No images or other personal or clinical details of participants are presented. All the anonymous private information collected was obtained from the acceptation of questionnaire. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Institutional Review board of Xiamen University. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing of interest

The author states that they have no competing of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ni, J., Zhang, J., Wang, Y. et al. Relationship between career maturity, psychological separation, and occupational self-efficacy of postgraduates: moderating effect of registered residence type. BMC Psychol 11 , 246 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01261-9

Download citation

Received : 20 April 2023

Accepted : 24 July 2023

Published : 20 October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01261-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Career maturity

- Psychological separation

- Occupational self-efficacy

- Postgraduates

- Registered residence type

- Mediating effect

- Moderating effect

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Mapping career patterns in research: A sequence analysis of career histories of ERC applicants

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Independent Expert, Affiliated with Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Contributed equally to this work with: Sara Connolly, Stefan Fuchs, Channah Herschberg, Brigitte Schels

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Norwich Business School, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

Affiliation Institute for Employment Research, Nuremberg, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Institute for Management Research, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute for Employment Research, Nuremberg, Germany, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Nuremberg, Germany

- Claartje J. Vinkenburg,

- Sara Connolly,

- Stefan Fuchs,

- Channah Herschberg,

- Brigitte Schels

- Published: July 29, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236252

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

22 Jun 2021: The PLOS ONE Staff (2021) Correction: Mapping career patterns in research: A sequence analysis of career histories of ERC applicants. PLOS ONE 16(6): e0253832. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253832 View correction

Despite the need to map research careers, the empirical evidence on career patterns of researchers is limited. We also do not know whether career patterns of researchers can be considered conventional in terms of steady progress or international mobility, nor do we know if career patterns differ between men and women in research as is commonly assumed. We use sequence analysis to identify career patterns of researchers across positions and institutions, based on full career histories of applicants to the European Research Council frontier research grant schemes. We distinguish five career patterns for early and established men and women researchers. With multinomial logit analyses, we estimate the relative likelihood of researchers with certain characteristics in each pattern. We find grantees among all patterns, and limited evidence of gender differences. Our findings on career patterns in research inform further studies and policy making on career development, research funding, and gender equality.

Citation: Vinkenburg CJ, Connolly S, Fuchs S, Herschberg C, Schels B (2020) Mapping career patterns in research: A sequence analysis of career histories of ERC applicants. PLoS ONE 15(7): e0236252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236252

Editor: Ting Ren, Peking University, CHINA

Received: October 25, 2019; Accepted: July 2, 2020; Published: July 29, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Vinkenburg et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Unrestricted and uncontrolled access to the complete career history data (in terms of position, institution, contract type, location etc. of all spells since PhD) compromises the confidentiality and privacy of research participants, and violates the conditions on ethics approval obtained for this study from the Ethical Committee of the European Research Council. Simplified de-identified data sets that contain minimal but relevant personal (age, gender, children, etc) and career related variables, including a career pattern denominator, are available upon request. The data sets are available through the University of East Anglia: https://people.uea.ac.uk/en/datasets/mapping-career-patterns-in-research-a-sequence-analysis-of-career-histories-of-erc-applicants(a64c76cc-da8f-4ab1-b19f-7a3b3a814d7f).html . Please contact [email protected] to explain why you need the data and purposes for which they will be used. The data will be made available through one of the beneficiaries of our ERCAREER grant, Professor Sara Connolly.

Funding: This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC https://erc.europa.eu/ ) Coordination and Support Action (CSA) [ERC-CSA-2012-317442], project acronym ERCAREER, awarded to CJV SC SF. The funder was instrumental in data collection.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist

Data on the career paths of young researchers would help […] . There is a pressing need for greater transparency about the likelihood of PhD students and postdocs following an academic career to the higher levels . […] . vn [ 1 ].

Introduction

The need to map research careers is tied to policy efforts to stimulate career mobility and enhance career development for researchers [ 2 – 4 ], with the ultimate goal to strengthen innovation and the knowledge economy. However, despite some efforts to map research careers in the European context [ 5 – 9 ], exactly how research careers develop in terms of patterns or moves through positions and institutions remains largely uncharted territory [ 1 ]. Research careers are often described in terms of outcomes (i.e. publications) [ 10 ] or mobility events (i.e. international moves) [ 11 ]. Following Abbott, we view the career pattern itself as an outcome [ 12 ]. After obtaining a PhD, researchers move through job positions within and between institutions. From a holistic life course perspective, careers are not (only) marked by singular specific events but also a sequence of states that may differ in progression and timing [ 13 ]. However, details on differences in career trajectories of individual researchers are lacking [ 14 ]. Based on full career histories of European Research Council (ERC) Starting and Advanced grant applicants, we contribute to earlier studies of research careers by mapping the career patterns of men and women researchers from their PhD to more established careers. We do not start from theoretical or anecdotal assumptions about career patterns but use a relatively new analytical strategy developed to empirically capture the nature of career patterns over time and place, providing an overview of research careers in different disciplinary and national settings across Europe.

Career patterns can be interpreted as objectively observable paths of movement through occupational hierarchies [ 15 ]. However, despite the ubiquitous presence of the term “career patterns” in discourse and writings about careers in research, earlier efforts to track research careers yielded limited evidence on exactly how research careers develop over time. We often assume that researchers follow a very similar and traditional career path after obtaining their PhD degree [ 16 ]. The normative expectation of upward mobility has changed from a stylized career path [ 17 ] based on a very limited number of academic “rites of passage” (e.g. PhD defense, inaugural lecture) toward a new career model of cumulative promotions [ 18 ]. However, such expectations and assertions are rarely built on an evidence base of actual career patterns in research. Our analysis reveals how research careers develop over time, in terms of moving through positions and institutions, and whether career patterns beyond the “traditional” can be identified among researchers who apply to the ERC.

The ERC in looking for “excellence only” aims at selecting “groundbreaking” and “truly novel research” for funding [ 19 , 20 ]. By funding and thus organizing excellent science at the European level [ 21 – 23 ], the ERC extends national funding schemes with unique conditions: generous, long-term, flexible, and risk-tolerant [ 24 ]. The ERC’s prestigious individual research grants [ 20 , 25 ] are awarded based on a peer-reviewed evaluation of the quality of the principal investigator and the research proposal [ 19 ]. Similar to other grant schemes, ERC evaluators rank applications taking into account both the science and the scientist [ 26 , 27 ]. The career histories of applicants, thus, play an important role in the ERC peer review process. Previous studies have shown that funded applicants (grantees) and non-funded applicants in various research funding schemes do not differ (much) on objective quality criteria [ 28 , 29 ] and therefore we include both funded and non-funded applicants in our study. Applications to the ERC are made through a host institution, where the research will be undertaken, and there is typically an internal sorting within institutions resulting in support for only the highest quality applications [ 30 , 31 ]. We therefore argue that both the funded and non-funded applicants are among the most excellent researchers of their generation as their applications have been submitted to the most prestigious European research funding organization. Using an exploratory, empirical approach we study how the careers of these researchers develop and whether they develop in a similar manner–in accordance with the assumed traditional career path in research and matching normative expectations of upward mobility.

In addition, we study another commonly held assumption, namely that the careers of men and women in research tend to develop differently. In their initial report on research careers in Europe, ESF [ 2 ] states that “almost all obstacles and bottlenecks identified during a research career affect the careers of women scientists more severely than those of men”, with the main underlying cause of this difference being care responsibilities, which fall disproportionally to women. This assumption is found extensively in the literature and also resonates in the call for proposals sent out by the ERC gender balance thematic working group in 2011 to map “the paths and patterns, differences and similarities in the career paths of women and men ERC grantees”. Our proposal was selected by the ERC to explore gender aspects in career structures and career paths of applicants.

However, despite women’s relative underrepresentation at the highest levels in most research fields [ 32 ], and given that women ERC grantees have lower publication rates than men [ 33 ], we do not know whether women researchers’ career develop at a different speed or in a different way than men’s, nor do we know the actual impact of care responsibilities on career patterns. We therefore empirically test the likelihood of men and women following different career patterns, as well as the extent to which certain personal and institutional characteristics affected this likelihood differentially for men and women.

To map career patterns in research across disciplines around Europe, we use a specific kind of sequence analysis called Optimal Matching Analysis (OMA). OMA incorporates timing alongside transition between occupational states, offering an appropriate analytical tool for the study of careers [ 34 , 35 ]. Abbott [ 36 , 37 ] proposed using OMA, as an appropriate method for measuring life courses “as they are”, calling this descriptive approach a paradigm shift from causes to events. OMA is used to identify order in sequences by analyzing the similarity of sequences to one another and sorting them into groups of similar sequences [ 13 ]. Using data on career histories of ERC grant applicants, OMA provides insights into career patterns among early and established researchers, highlighting differences and similarities. For each grant scheme we identify patterns reflecting combinations of positional and institutional sequences, different progression logics, and movements–including leave or spells of unemployment. In distinguishing five career patterns for early and five for established researchers across Europe, we explore whether certain patterns are more common or “conventional” than others, whether some patterns are associated with greater likelihood of application success, and how gender and other personal, disciplinary, and PhD-related factors affect the likelihood and appearance of career patterns. This mapping of research career patterns should inform research policy, in terms of promoting career development, mobility, and gender equality in funding.

Career patterns in research

The origins of the construct of career patterns can be found in industrial sociology where “it was viewed, objectively, as the number, duration, and sequence of jobs in the work history of individuals” [ 38 , 39 ]. Career conventions, or general agreements on descriptions of common career patterns, are likely to be normative, in the sense that they provide prescriptions of what careers in research should look like. The notion of an ideal career in research likely translates into career conventions in terms of linearity or steady progress [ 40 ], early successes [ 41 ], institutional prestige [ 42 ], and (inter) national mobility [ 43 , 44 ].

These conventions have been surprisingly stable despite the increasing demographic diversity of those who do research and the challenges to the conventional view of research careers associated with this diversity, most notably perhaps with respect to the representation of women [ 32 , 45 , 46 ]. It is evident that career conventions matter in selection decisions (including funding). Decision makers use signals such as linearity and mobility (upward and across borders), sometimes even as a proxy for excellence [ 44 , 47 ]. Careers as represented by CVs play an important part when funding decisions are made [ 26 , 27 , 48 , 49 ] and are viewed through lenses that are affected by the context, culture, and gender of the candidate and the evaluator. Knowledge of career progress in terms of moving between positions within and across different types of institutions (e.g., universities, research institutes) is important for the evaluation of researchers’ standing and independence [ 25 ].

Despite more than a decade of efforts to track research careers across disciplinary and national contexts, conclusive answers on career patterns of researchers are missing. To gain insight into the existing empirical evidence on career patterns in research, we performed an extensive literature review (see S1 File for search strategy and detailed findings; and [ 14 ] for an earlier version of the review). From the final set of 40 peer reviewed sources, we conclude that the number of existing empirical studies that shed light on what career patterns in research “objectively” look like is very small. While many sources refer to the existence of “career patterns”, there are actually only three studies that empirically distinguish unique patterns in research based on temporal combinations of positions and institutions. Two of these use CVs to identify distinct career patterns for senior administrators in U.S. universities [ 34 , 50 ]. The third is a recent paper [ 51 ], which differentiates five early career patterns based on narratives from young academics crossing disciplinary, institutional, and national borders.