Have Fun With History

Common Sense by Thomas Paine – Significance and Influence

“Common Sense” by Thomas Paine is a timeless and influential pamphlet that played a pivotal role in shaping the course of history.

Published in 1776 during the American Revolution, Paine’s persuasive writing and revolutionary ideas captivated the minds of the American colonists, sparking a fervent call for independence from British rule.

This brief exploration delves into the significance of “Common Sense,” its impact on the American Revolution, its role in fostering unity among the colonies, and its enduring influence on political thought both in the United States and beyond.

The Significance of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

1. advocated for american independence.

“Common Sense” was a groundbreaking pamphlet published by Thomas Paine in 1776, during a critical time in American history. Paine’s central argument was for the complete independence of the American colonies from British rule.

Also Read: Thomas Paine Timeline

He eloquently and passionately challenged the notion of a hereditary monarchy and questioned the legitimacy of the British monarchy’s authority over the distant colonies.

Paine argued that it was only natural for the American people to govern themselves, free from the control of a distant and unresponsive government across the Atlantic.

2. Played a crucial role in the American Revolution

The publication of “Common Sense” had an extraordinary impact on the American Revolution. At the time of its release, there was considerable debate within the colonies regarding the path they should take in response to British policies.

Also Read: Thomas Paine Facts

Paine’s pamphlet struck a chord with the general public, as it presented a compelling case for outright independence. The pamphlet was widely read and discussed, reaching people from all walks of life, including ordinary citizens, soldiers, and political leaders.

“Common Sense” helped galvanize public sentiment and mobilized support for the revolutionary cause. It provided a clear and powerful argument for why breaking away from British rule was not only justified but necessary for the preservation of liberty and self-determination.

3. Influenced the formation of the United States as a democratic republic

Beyond advocating for independence, “Common Sense” also laid out Paine’s vision for a new form of government for the American colonies.

Paine promoted the idea of a democratic republic, where the power to govern would be vested in the hands of the people, rather than in the hands of a monarch or ruling elite.

His ideas helped to shape the thinking of the Founding Fathers, such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, who played instrumental roles in drafting the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

Paine’s call for a government based on the consent of the governed and the protection of individual rights echoed throughout the founding documents of the United States, making a lasting impact on the country’s political structure and principles.

4. Written in a clear and accessible style

One of the key reasons for the immense impact of “Common Sense” was Thomas Paine’s ability to convey complex political ideas in a clear and straightforward manner.

Unlike many other political writings of the time, which were often dense and filled with formal language, Paine wrote in simple and accessible prose. He deliberately used everyday language that could be easily understood by common people, ensuring that his arguments reached a wide audience.

This approach was revolutionary in itself, as it made political discourse more inclusive and helped bridge the gap between the educated elite and ordinary citizens.

Paine’s writing style set a precedent for future political communication, emphasizing the importance of clarity and accessibility in conveying ideas to the masses.

5. Widely distributed throughout the American colonies

Despite the limited means of communication and printing technology in the 18th century, “Common Sense” achieved remarkable distribution and dissemination.

Paine initially published the pamphlet anonymously, but its authorship was soon revealed. It was printed and distributed in various cities and towns throughout the American colonies.

Due to its affordable price and easy-to-read format, many copies were sold and shared among people from all walks of life.

The pamphlet’s widespread availability ensured that its message reached a vast audience and contributed to its significant influence on public opinion. Paine’s work also inspired others to write responses and engage in a broader public debate about independence and self-governance.

6. Popularized republican ideology

“Common Sense” played a crucial role in popularizing republican ideals among the American colonists. Paine argued for a government based on the consent of the governed and advocated for the abolishment of monarchy and aristocracy.

He proposed a representative democracy, where elected officials would act in the best interest of the people and uphold their rights and freedoms. Paine’s promotion of these republican principles resonated with many colonists who were seeking a new and just form of government.

His ideas reinforced the belief that the power to govern should come from the people themselves, not from a distant and unaccountable monarchy.

This popularization of republican ideology helped solidify the concept of sovereignty residing with the people and contributed to the formation of democratic institutions in the emerging United States.

7. Contributed to the drafting of the Declaration of Independence

The ideas presented in “Common Sense” had a profound influence on the thinking of the Founding Fathers, many of whom were already sympathetic to the cause of independence. Thomas Paine’s arguments reinforced their beliefs and provided additional support for the case for separation from Britain.

Some of Paine’s language and concepts found their way into the drafting of the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted on July 4, 1776.

Notably, the Declaration emphasized the principles of natural rights, the consent of the governed, and the right to alter or abolish an oppressive government, ideas that were already prominent in “Common Sense.”

While Paine himself was not directly involved in the drafting of the Declaration, his pamphlet played a significant role in shaping the intellectual climate that led to its creation.

8. Fostered unity among the American colonies

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, the thirteen colonies were diverse in terms of their backgrounds, economies, and political structures. They did not always see eye-to-eye on matters of governance and resistance to British policies.

“Common Sense” helped bridge these divides and fostered a sense of unity among the colonies. By providing a coherent argument for independence and republican government, Paine encouraged the colonies to work together in their struggle against British rule.

The pamphlet made the case that the shared cause of independence was more important than any regional differences or disagreements. As a result, “Common Sense” played a vital role in consolidating the colonies’ efforts and building a collective sense of identity that would prove crucial during the American Revolution.

9. Enduring influence on political thought

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” remains an enduring and celebrated work in the history of political thought. Its impact extended far beyond the American Revolution.

The pamphlet’s articulation of democratic principles, advocacy for independence, and criticisms of monarchy and tyranny have continued to inspire generations of thinkers, politicians, and activists around the world.

Paine’s ideas on the rights of individuals and the legitimacy of government have become foundational concepts in political theory and have shaped discussions on governance, liberty, and democracy for centuries. “Common Sense” stands as a testament to the power of persuasive writing and the ability of one individual to profoundly influence the course of history.

10. Inspired independence movements worldwide

Beyond its impact on the American Revolution and the formation of the United States, “Common Sense” had a broader influence on the global stage. Translations and excerpts of the pamphlet spread to other countries, inspiring independence movements and political revolutions in various parts of the world.

Paine’s ideas on the rights of people to govern themselves and the need to challenge oppressive authority resonated with individuals and groups seeking freedom and self-determination in different contexts. “Common Sense” became a symbol of the transformative power of ideas, inspiring movements for liberty and independence throughout the ages and across continents.

America in Class Lessons

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, 1776

By Wason, Marianne (NHC Assistant Director of Education Programs, Online Resources, 1997–2014)

By January 1776, the American colonies were in open rebellion against Britain. Their soldiers had captured Fort Ticonderoga, besieged Boston, fortified New York City, and invaded Canada. Yet few dared voice what most knew was true — they were no longer fighting for their rights as British subjects. They weren’t fighting for self-defense, or protection of their property, or to force Britain to the negotiating table. They were fighting for independence. It took a hard jolt to move Americans from professed loyalty to declared rebellion, and it came in large part from Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. Not a dumbed-down rant for the masses, as often described, Common Sense is a masterful piece of argument and rhetoric that proved the power of words.

Political Science / History / Education Studies / American Revolution / American History / Rhetoric / Primary Sources /

- USHistory.org

Common Sense

- The American Crisis

- The Rights of Man

- Age of Reason

by Thomas Paine

Published in 1776, Common Sense challenged the authority of the British government and the royal monarchy. The plain language that Paine used spoke to the common people of America and was the first work to openly ask for independence from Great Britain.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

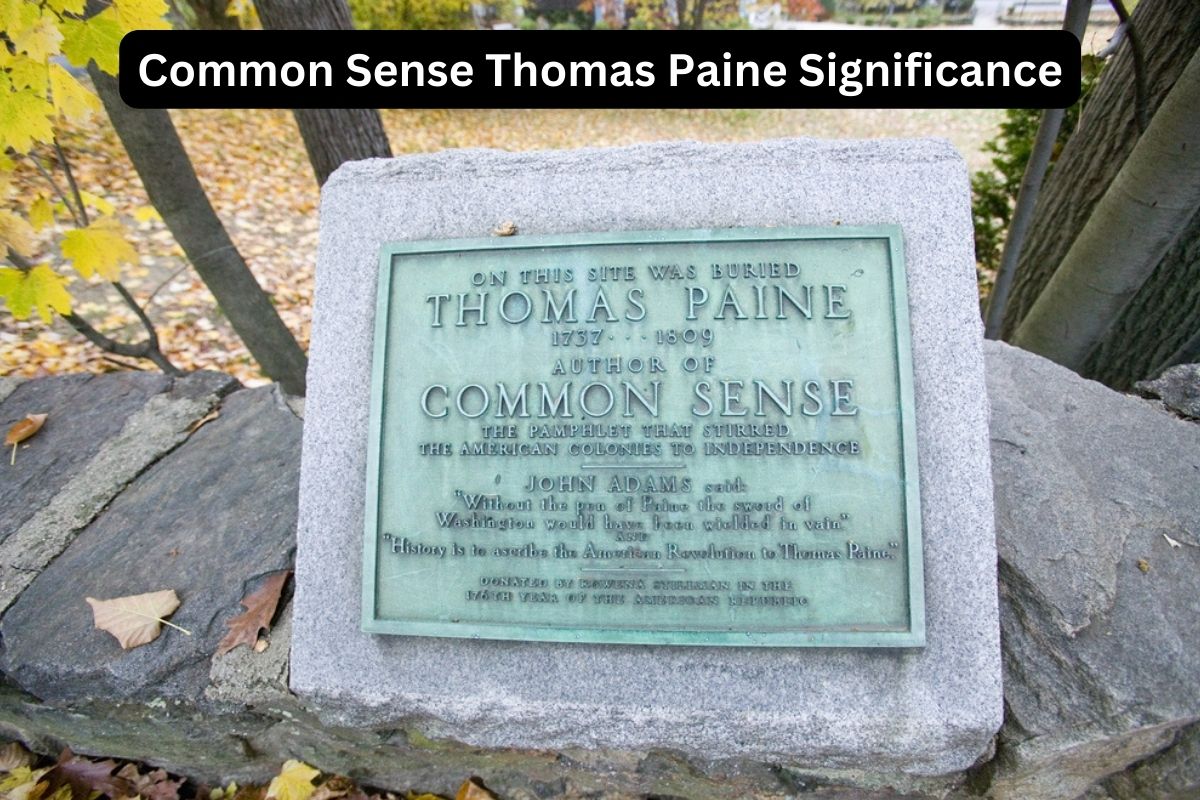

January 10 marks the anniversary of the publication of Thomas Paine’s influential Common Sense in 1776.

On January 10, 1776, an obscure immigrant published a small pamphlet that ignited independence in America and shifted the political landscape of the patriot movement from reform within the British imperial system to independence from it.

One hundred twenty thousand copies sold in the first three months in a nation of three million people, making Common Sense the best-selling printed work by a single author in American history up to that time.

Never before had a personally written work appealed to all classes of colonists. Never before had a pamphlet been written in an inspiring style so accessible to the “common” folk of America.

A government of our own is our natural right…Ye that oppose independence now, ye know not what ye do; ye are opening a door to eternal tyranny, by keeping vacant the seat of government.

Common Sense made a clear case for independence and directly attacked the political, economic, and ideological obstacles to achieving it. Paine relentlessly insisted that British rule was responsible for nearly every problem in colonial society and that the 1770s crisis could only be resolved by colonial independence. That goal, he maintained, could only be achieved through unified action.

Hard-nosed political logic demanded the creation of an American nation. Implicitly acknowledging the hold that tradition and deference had on the colonial mind, Paine also launched an assault on both the premises behind the British government and on the legitimacy of monarchy and hereditary power in general. Challenging the King’s paternal authority in the harshest terms, he mocked royal actions in America and declared that “even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their own families.”

Finally, Paine detailed in the most graphic, compelling and recognizable terms the suffering that the colonies had endured, reminding his readers of the torment and trauma that British policy had inflicted upon them.

Yuval Levin on the Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left

but from the errors of other nations, let us learn wisdom, and lay hold of the present opportunity—To begin government at the right end…

Resources on Thomas Paine and Common Sense

The complete writings of thomas paine.

Project Gutenberg provides the compilation of Thomas Paine’s writings online, including Common Sense , The American Crisis , Rights of Man , and the controversial The Age of Reason . Shorter pieces include private letters to Thomas Jefferson and a letter criticizing the American government and George Washington .

Thomas Paine Friends, Inc.

Thomas Paine Friends, Inc., an association dedicated to an increased public awareness of Paine’s political contributions, provides several articles and resources for further reading on this lesser known founder.

Jon Katz on Paine’s Life and Influence on Journalism

In an article for Wired , Jon Katz provides a narrative of Thomas Paine’s life and argues that Paine should be recognized as the moral father of the internet and a pioneer of journalism.

John Adams on Thomas Paine

Although Common Sense proved to be an influential piece of American political thought, John Adams did not think much of it, nor of its author: “The Arguments in favor of Independence I liked very well: but one third of the Book was filled with Arguments from the old Testament, to prove the Unlawfulness of Monarchy, and another Third, in planning a form of Government, for the separate States in One Assembly, and for the United States, in a Congress.”

How The American Crisis Saved the Revolution

Common Sense may be the best-known of Paine’s writings, but another of his pamphlets, The American Crisis , was critical in rallying the patriots to a victory at Trenton in late 1776. Paine’s The American Crisis contains the famous quote: “ These are the times that try men’s souls : The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph .”

In addition to the audacity and timeliness of its ideas, Common Sense compelled the American people because it resonated with their firm belief in liberty and determined opposition to injustice. The message was powerful because it was written in relatively blunt language that colonists of different backgrounds could understand.

Paine, despite his immigrant status, was on familiar terms with the popular classes in America and the taverns, workshops, and street corners they frequented. His writing was replete with the kind of popular and religious references they readily grasped and appreciated. His strident indignation reflected the anger that was rising in the American body politic. His words united elite and popular strands of revolt, welding the Congress and the street into a common purpose.

As historian Scott Liell argues in Thomas Paine, Common Sense, and the Turning Point to Independence : “[B]y including all of the colonists in the discussion that would determine their future, Common Sense became not just a critical step in the journey toward American independence but also an important artifact in the foundation of American democracy” (20).

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

Common Sense and the political thought of Thomas Paine

Seth Cotlar, “Thomas Paine in the Atlantic Historical Imagination.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Seth Cotlar, Tom Paine’s America: The Rise and Fall of Trans-Atlantic Radicalism in the Early Republic . (University of Virginia Press, 2011)

Seth Cotlar, “Tom Paine’s Readers and the Making of Democratic Citizens in the Age of Revolutions.” ( Thomas Paine: Common Sense for the Modern Era , San Diego State University Press, 2007)

Armin Mattes, “Paine, Jefferson, and the Modern Ideas of Democracy and the Nation.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Eric Nelson, “Hebraism and the Republican Turn of 1776: A Contemporary Account of the Debate over Common Sense.” ( The William and Mary Quarterly 70.4, October 2013)

Peter Onuf (editor), Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions . (University of Virginia Press, 2014)

William Parsons, “Of Monarchs and Majorities: Thomas Paine’s Problematic and Prescient Critique of the U.S. Constitution. ” ( Perspectives on Political Science 43.2, 2014)

Gordon Wood, “The Radicalism of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine Considered.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

Michael Zuckert, “Two paths from Revolution: Jefferson, Paine and the Radicalization of Enlightenment Thought.” ( Paine and Jefferson in the Age of Revolutions , University of Virginia Press, 2013)

…But where says some is the King of America? I’ll tell you Friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal Brute of Britain. Yet that we may not appear to be defective even in earthly honors, let a day be solemnly set apart for proclaiming the charter; let it be brought forth placed on the divine law, the word of God; let a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.

If you are a JMC Scholar who’s published on the Fourteenth Amendment and would like your work included here

Stay up to date with the jack miller center.

Sign up for one of our newsletters!

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : January 10

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Thomas Paine publishes “Common Sense”

On January 10, 1776, writer Thomas Paine publishes his pamphlet “Common Sense,” setting forth his arguments in favor of American independence. Although little used today, pamphlets were an important medium for the spread of ideas in the 16th through 19th centuries.

Originally published anonymously, “Common Sense” advocated independence for the American colonies from Britain and is considered one of the most influential pamphlets in American history. Credited with uniting average citizens and political leaders behind the idea of independence, “Common Sense” played a remarkable role in transforming a colonial squabble into the American Revolution .

At the time Paine wrote “Common Sense,” most colonists considered themselves to be aggrieved Britons. Paine fundamentally changed the tenor of colonists’ argument with the crown when he wrote the following: “Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither they have fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still.”

Paine was born in England in 1737 and worked as a corset maker in his teens and, later, as a sailor and schoolteacher before becoming a prominent pamphleteer. In 1774, Paine arrived in Philadelphia and soon came to support American independence. Two years later, his 47-page pamphlet sold some 500,000 copies, powerfully influencing American opinion. Paine went on to serve in the U.S. Army and to work for the Committee of Foreign Affairs before returning to Europe in 1787. Back in England, he continued writing pamphlets in support of revolution. He released “The Rights of Man,” supporting the French Revolution in 1791-92, in answer to Edmund Burke’s famous “Reflections on the Revolution in France” (1790). His sentiments were highly unpopular with the still-monarchal British government, so he fled to France, where he was later arrested for his political opinions. He returned to the United States in 1802 and died in New York in 1809.

Also on This Day in History January | 10

This Day in History Video: What Happened on January 10

First meeting of the United Nations

League of nations instituted, gusher signals new era of u.s. oil industry, president harding orders u.s. troops home from germany, president johnson asks for more funding for vietnam war.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

FDR introduces the lend‑lease program

Outlaw frank james born in missouri, aol‑time warner merger announced, avalanche kills thousands in peru, world’s cheapest car debuts in india.

The American Revolution Reader

Primary source: thomas paine calls for american independence, 1776.

Common Sense is a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–76 that inspired people in the Thirteen Colonies to declare and fight for independence from Great Britain in the summer of 1776. The pamphlet explained the advantages of and the need for immediate independence in clear, simple language. It was published anonymously on January 10, 1776, at the beginning of the American Revolution and became an immediate sensation. It was sold and distributed widely and read aloud at taverns and meeting places.

Washington had it read to all his troops, which at the time had surrounded the British army in Boston. In proportion to the population of the colonies at that time (2.5 million), it had the largest sale and circulation of any book published in American history. As of 2006, it remains the all-time best selling American title.

Common Sense presented the American colonists with an argument for freedom from British rule at a time when the question of whether or not to seek independence was the central issue of the day. Paine wrote and reasoned in a style that common people understood. Forgoing the philosophical and Latin references used by Enlightenment era writers, he structured Common Sense as if it were a sermon, and relied on Biblical references to make his case to the people. He connected independence with common dissenting Protestant beliefs as a means to present a distinctly American political identity. Historian Gordon S. Wood described Common Sense as “the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era.”

Thoughts of the present state of American Affairs

The sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ‘Tis not the affair of a city, a country, a province, or a kingdom, but of a continent of at least one eighth part of the habitable globe. ‘Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected, even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed time of continental union, faith and honor. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; The wound will enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

By referring the matter from argument to arms, a new æra for politics is struck; a new method of thinking hath arisen. All plans, proposals, &c. prior to the nineteenth of April, i. e. to the commencement of hostilities, are like the almanacks of the last year; which, though proper then, are superceded and useless now. Whatever was advanced by the advocates on either side of the question then, terminated in one and the same point, viz. a union with Great-Britain; the only difference between the parties was the method of effecting it; the one proposing force, the other friendship; but it hath so far happened that the first hath failed, and the second hath withdrawn her influence.

As much hath been said of the advantages of reconciliation, which, like an agreeable dream, hath passed away and left us as we were, it is but right, that we should examine the contrary side of the argument, and inquire into some of the many material injuries which these colonies sustain, and always will sustain, by being connected with, and dependant on Great-Britain. To examine that connexion and dependance, on the principles of nature and common sense, to see what we have to trust to, if separated, and what we are to expect, if dependant.

I have heard it asserted by some, that as America hath flourished under her former connexion with Great-Britain, that the same connexion is necessary towards her future happiness, and will always have the same effect. Nothing can be more fallacious than this kind of argument. We may as well assert that because a child has thrived upon milk, that it is never to have meat, or that the first twenty years of our lives is to become a precedent for the next twenty. But even this is admitting more than is true, for I answer roundly, that America would have flourished as much, and probably much more, had no European power had any thing to do with her. The commerce, by which she hath enriched herself are the necessaries of life, and will always have a market while eating is the custom of Europe.

But she has protected us, say some. That she hath engrossed us is true, and defended the continent at our expence as well as her own is admitted, and she would have defended Turkey from the same motive, viz. the sake of trade and dominion.

Alas, we have been long led away by ancient prejudices, and made large sacrifices to superstition. We have boasted the protection of Great-Britain, without considering, that her motive was interest not attachment; that she did not protect us from our enemies on our account, but from her enemies on her own account, from those who had no quarrel with us on any other account, and who will always be our enemies on the same account. Let Britain wave her pretensions to the continent, or the continent throw off the dependance, and we should be at peace with France and Spain were they at war with Britain. The miseries of Hanover last war ought to warn us against connexions.

It hath lately been asserted in parliament, that the colonies have no relation to each other but through the parent country, i. e. that Pennsylvania and the Jerseys, and so on for the rest, are sister colonies by the way of England; this is certainly a very round-about way of proving relationship, but it is the nearest and only true way of proving enemyship, if I may so call it. France and Spain never were, nor perhaps ever will be our enemies as Americans, but as our being the subjects of Great-Britain.

But Britain is the parent country, say some. Then the more shame upon her conduct. Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families; wherefore the assertion, if true, turns to her reproach; but it happens not to be true, or only partly so, and the phrase parent or mother country hath been jesuitically adopted by the king and his parasites, with a low papistical design of gaining an unfair bias on the credulous weakness of our minds. Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither have they fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still.

In this extensive quarter of the globe, we forget the narrow limits of three hundred and sixty miles (the extent of England) and carry our friendship on a larger scale; we claim brotherhood with every European Christian, and triumph in the generosity of the sentiment.

It is pleasant to observe by what regular gradations we surmount the force of local prejudice, as we enlarge our acquaintance with the world. A man born in any town in England divided into parishes, will naturally associate most with his fellow parishioners (because their interests in many cases will be common) and distinguish him by the name of neighbour; if he meet him but a few miles from home, he drops the narrow idea of a street, and salutes him by the name of townsman; if he travel out of the county, and meet him in any other, he forgets the minor divisions of street and town, and calls him countryman; i. e. county-man; but if in their foreign excursions they should associate in France or any other part of Europe, their local remembrance would be enlarged into that of Englishmen. And by a just parity of reasoning, all Europeans meeting in America, or any other quarter of the globe, are countrymen; for England, Holland, Germany, or Sweden, when compared with the whole, stand in the same places on the larger scale, which the divisions of street, town, and county do on the smaller ones; distinctions too limited for continental minds. Not one third of the inhabitants, even of this province, are of English descent. Wherefore I reprobate the phrase of parent or mother country applied to England only, as being false, selfish, narrow and ungenerous.

But admitting, that we were all of English descent, what does it amount to? Nothing. Britain, being now an open enemy, extinguishes every other name and title: And to say that reconciliation is our duty, is truly farcical. The first king of England, of the present line (William the Conqueror) was a Frenchman, and half the Peers of England are descendants from the same country; wherefore, by the same method of reasoning, England ought to be governed by France.

Much hath been said of the united strength of Britain and the colonies, that in conjunction they might bid defiance to the world. But this is mere presumption; the fate of war is uncertain, neither do the expressions mean any thing; for this continent would never suffer itself to be drained of inhabitants, to support the British arms in either Asia, Africa, or Europe.

Besides, what have we to do with setting the world at defiance? Our plan is commerce, and that, well attended to, will secure us the peace and friendship of all Europe; because, it is the interest of all Europe to have America a free port. Her trade will always be a protection, and her barrenness of gold and silver secure her from invaders.

I challenge the warmest advocate for reconciliation, to shew, a single advantage that this continent can reap, by being connected with Great Britain. I repeat the challenge, not a single advantage is derived. Our corn will fetch its price in any market in Europe, and our imported goods must be paid for buy them where we will.

But the injuries and disadvantages we sustain by that connection, are without number; and our duty to mankind at large, as well as to ourselves, instruct us to renounce the alliance: Because, any submission to, or dependance on Great-Britain, tends directly to involve this continent in European wars and quarrels; and sets us at variance with nations, who would otherwise seek our friendship, and against whom, we have neither anger nor complaint. As Europe is our market for trade, we ought to form no partial connection with any part of it. It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions, which she never can do, while by her dependance on Britain, she is made the make-weight in the scale on British politics.

Europe is too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace, and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain. The next war may not turn out like the last, and should it not, the advocates for reconciliation now will be wishing for separation then, because, neutrality in that case, would be a safer convoy than a man of war. Every thing that is right or natural pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ‘TIS TIME TO PART. Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America, is a strong and natural proof, that the authority of the one, over the other, was never the design of Heaven. The time likewise at which the continent was discovered, adds weight to the argument, and the manner in which it was peopled encreases the force of it. The Reformation was preceded by the discovery of America, as if the Almighty graciously meant to open a sanctuary to the persecuted in future years, when home should afford neither friendship nor safety.

The authority of Great-Britain over this continent, is a form of government, which sooner or later must have an end: And a serious mind can draw no true pleasure by looking forward, under the painful and positive conviction, that what he calls “the present constitution” is merely temporary. As parents, we can have no joy, knowing that this government is not sufficiently lasting to ensure any thing which we may bequeath to posterity: And by a plain method of argument, as we are running the next generation into debt, we ought to do the work of it, otherwise we use them meanly and pitifully. In order to discover the line of our duty rightly, we should take our children in our hand, and fix our station a few years farther into life; that eminence will present a prospect, which a few present fears and prejudices conceal from our sight.

- Introduction to Common Sense. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Sense_%28pamphlet%29 . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Excerpt from Common Sense. Provided by : Wikisource. Located at : https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Common_Sense . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Ohio State navigation bar

- BuckeyeLink

- Search Ohio State

Common Sense: Thomas Paine and American Independence

Lesson plan.

Core Theme:

Grade: , ohio academic content standards:, primary source used:, summary: , estimated duration of lesson:, instructional steps:.

2. Pass out the

Post Assessment

Estimated duration of lesson: , summary of lesson:, instructional steps of lesson: , post assessment: .

Open Yale Courses

You are here, hist 116: the american revolution, - common sense.

This lecture focuses on the best-selling pamphlet of the American Revolution: Thomas Paine’s Common Sense , discussing Paine’s life and the events that led him to write his pamphlet. Published in January of 1776, it condemned monarchy as a bad form of government, and urged the colonies to declare independence and establish their own form of republican government. Its incendiary language and simple format made it popular throughout the colonies, helping to radicalize many Americans and pushing them to seriously consider the idea of declaring independence from Britain.

Lecture Chapters

- Introduction: Voting on Voting

- On Paine's Burial

- Colonial Mindset during the Second Continental Congress

- Serendipity and Passion: The Early Life of Thomas Paine

- Major Arguments and Rhetorical Styles in "Common Sense"

- "Common Sense's" Popularity and Founders' Reactions

- Social Impact of the Pamphlet and Conclusion

| Transcript | Audio | Low Bandwidth Video | High Bandwidth Video |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Today we are going to be discussing certainly one of the biggest bestsellers in early American history, and that’s Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Before I plunge in to I am going to answer the question that was asked from this section of the room on Tuesday, about how do you vote on voting — the little brain teaser of the Continental Congress. And I found the answer to this question. Okay. So the answer to the question is: they actually had a pretty animated debate in the Continental Congress on the whole voting question, and some people said it should be according to population and some said, ‘Well, you should put property in with population,’ and some people said one colony, one vote. And with — after apparently arguing for quite some time, what they realized was they actually really didn’t have an orderly way to figure out population and property worth, [laughter] and so they ultimately just decided one colony, one vote, [laughs] — like, that’s all we can do. And they were really concerned because they didn’t want that to be a precedent. They were all worried that they’d be setting a precedent for all time. So when they wrote it down in the minutes, they said, we’re deciding one colony, one vote, but not with the idea that it will be a precedent for all time. Of course, it then becomes a precedent for Congress under the Articles of Confederation. But the answer to the question — how did they vote? — is apparently someone made a motion — ‘I make a motion that we just do the one colony, one vote thing’ — and people just voted on the motion as a group. So that is the answer to the question: How do you vote on voting? I had not thought about it before and yet historians have addressed it so there you go so — Okay. That is the answer to the question. On to which really, truly unquestionably was a bestseller. It actually sold over 120,000 copies in its first few months in print, and a little bit later in the lecture I’m going to give you a sense of how that compares with how some other things might have sold in this time period. You’ll really get a sense of what kind of a bestseller this was. And certainly many scholars consider it to be the most brilliant political pamphlet of the Revolution, not necessarily for the subtlety of its argument but certainly for the way in which it’s argued, and I’ll talk more about that in the course of the lecture. So what we’re going to be looking at is the pamphlet itself and what specifically made it so remarkable. And then we’re also going to look some at its author, Thomas Paine, who he was and how he came to produce this influential pamphlet. But I actually want to begin with something that I just — in my head when I think about Thomas Paine I think about this, so I feel like I can’t start this lecture without discussing it. And that has to do with the death of Thomas Paine or actually, to be more accurate, the body of Thomas Paine. Okay. It’s one of the sad ironies of history that this person who — all through this lecture I’m going to be talking about the great influence of his pamphlet, had this great influence throughout the Revolution — and he actually died pretty much poor and not very much liked by Americans of all political stripes, more having to do with his politics later in his life than what he was doing during the Revolution, but he was not a happy camper in the years of his death. But the most horrifying thing about Paine’s death has to do with the question of his body. Okay. So Paine first asked about being buried in a Quaker cemetery, and the Quakers weren’t very excited about that because they were not really hoping to have that cemetery become a tourist attraction so that didn’t work. So he basically ended up at first being buried on his small farm in upstate New York. A few years later a newspaper editor named William Cobbett decided that what he was going to do was disinter the body and take it back to England, and then in England they would set up a memorial to Thomas Paine. This was his plan. So he did. He disinterred the body; he went on a boat; he and dead-body Paine went sailing back to England. Got back to England, raised the issue and apparently did not get very much support for the idea of a memorial of some kind. At this point it gets a little sad. Okay. So not knowing what else to do — and why at this point he didn’t think to bury him someplace else, I don’t know — but apparently he had the bones put in a trunk and kept them on his farm for a while. Okay. So, body of Paine sitting on his farm in England. Then he died — Mr. Cobbett died and the trunk and Paine was passed on to his son, and then his son I guess went into debt in some way and his belongings began to get auctioned off and the person doing the auctioning didn’t want to have anything to do with auctioning off a body. Like, I’ve never auctioned off a body before, I don’t want anything to do with this — and basically Paine’s corpse disappeared. We really do not know where Thomas Paine is. Truly, there was a trunk and it had Paine in it and then it vanished. And I went searching today before I gave this lecture, trying to figure out like — okay, maybe there’s been a recent development in the search for Thomas Paine, the corpse, and no actually. Although I did discover that in 2001 there was a society that wanted to create some kind of memorial here in America and they decided that they were going to try to trace the body so they set out trying to trace the body. What they found was, all over the world are people who claim to have a piece of Thomas Paine, right? Well, his skull might be in Australia but his leg — that might be in England. So the sort of — the horrifying end to Thomas Paine is his body disappeared and perhaps little pieces of Thomas Paine are floating around as little relics all over the world. So that’s Paine’s sort of weird ending, certainly not the kind of ending that you would wish for the person who has written the pamphlet we’re going to be talking about today. And we are given that — what he ended up writing was so influential and so different from much of what was being written at this time. Now as I said at the outset, it’s not the great subtleties of its argument that made it stand out. And in fact its popularity was due to the very things that were its greatest strengths: the fact that it was passionate, the fact that it had a really simple style, that it spoke to the common man, that it captured and completely overturned prevailing colonial ideas about the relationship between the mother country and the American colonies. As someone wrote at the time, Paine spoke a language which the colonists had felt, but not thought. One of the remarkable things about the pamphlet is that it was written by a somewhat bankrupt English corset-maker a mere fourteen months after he had arrived in America from England. Basically speaking, Paine knew relatively little about colonial affairs when he decided to write it. He wasn’t really an established writer. He had done writing before. I’ll talk a little bit about this today, but he wasn’t this sort of well-known and established writer. He wrote some for newspapers. And actually the idea for the pamphlet initially wasn’t really his. He wrote it at the encouragement of Dr. Benjamin Rush. I mentioned that in the first lecture, and I’m going to come back to that too. So Paine is relatively new to the colonies, not really an established writer, so how is it that he ends up writing this pamphlet? Well, more than anything else it actually was Paine’s experience of events in the colonies between 1775 and 1776 that inspired what he wrote. Now let’s look for a moment at — to see here what Paine is experiencing in that year before he wrote the pamphlet. What is happening around him. I’m going to talk about this really briefly here because I’ll be talking in more detail about this on Tuesday, but one thing I will mention here very briefly is, part of what happens between 1775 and 1776 is the meeting of the Second Continental Congress. And that actually begins meeting in the spring of 1775. I’ll talk about the details of the Congress Tuesday. For now, I’ll just talk about the general mindset. For one thing, no colony instructed its delegates to this Second Continental Congress to work for independence. That was not the agenda. Delegates were pretty much still acting under the assumption that they were trying to force Parliament or the King or someone to acknowledge their liberties and redress their grievances, and the overall assumption still was that balance had been thrown off within the British constitution and it needed to be rebalanced. So they’re talking about trying to figure out a way of balancing things, maybe a new balance, but they’re not talking about throwing the entire system aside. Actually, in the minds of many at the time they probably were thinking, why destroy what had for a very long time been one of the most successful political empires in the world. John Adams noted in his diary at the opening of the Second Continental Congress that at what he called an “elegant supper” at the opening of the Congress, many representatives and their friends toasted, quote, “the Union of Britain and the Colonies on a constitutional foundation.” Okay. So that’s what they’re hoping for as this Congress opens. As an example of this initial mindset of the Congress — again more about this Tuesday — moderates attempted one last stab at some kind of basic reconciliation with the Crown, and they issued what came to be known as the Olive Branch Petition. It failed for a number of reasons — again more next week — one of the most basic reasons being the King refused to read the Olive Branch Petition, which pretty much is the way to guarantee the failure of a petition. By doing that, the King basically gave some credence to the views of the more radical members of the Continental Congress, and radicals got even more credence on August 23, 1775, when the King issued a proclamation that declared the colonies to be in rebellion, and then made plans to send 20,000 British troops to the colonies, including Prussian mercenaries. Okay, a big change in things, much more detail Tuesday, but this is important to the setting of So the King ignores the Olive Branch Petition. He’s sending troops, not just any troops but literally hired guns, right? — foreign hired guns to go to the colonies. So the colonies have now been declared in rebellion. An army is coming. At this point the colonists realize that they need to maybe take some form of action and make some kind of military preparation, not in an aggressive way but certainly in a defensive way. Even as they began to do this and try to stock up on military supplies and engage in militia training, still a lot of colonists considered it pretty unlikely that a string of relatively weak — prosperous as they were — colonies could hope to defeat England, the most powerful nation on earth. And even if they did miraculously somehow manage to do that, certainly also most people in the colonies would have assumed that instantly, foreign powers would have come zipping over to North America and would have swallowed up these helpless little colonies, and so now instead of belonging to England they would have belonged to France or maybe Spain. So certainly things weren’t really feeling really optimistic at this moment in which things seemed to be dramatically shifting, and this is the setting in which Paine wrote In his mind, the time was right for some kind of a drastic change for the better in the American colonies and, as we’ll see, instead of just tinkering with the English constitution Paine basically turns his back on it, rejects King George III, rejects Parliament, and ultimately rejects even the idea of monarchy. So instead of centering on the British constitution, Paine based his ideas about colonial society and government on natural rights logic, arguing that the colonies should join in a new government grounded on equality. Now obviously ideas about natural rights, natural rights talk, isn’t new. Paine’s achievement was to take those kinds of ideas and in a sense give them to ordinary people. Part of what he argues in his pamphlet is: this isn’t some great high constitutional argument. This is about you and me and life in the colonies. And, as we’ll see, in method and in audience and in argument — for all of these reasons, Paine’s pamphlet had a big impact. So let’s look for a moment at who this man was who wrote this early American bestseller. Well, he was relatively poor. He was never really well off. Obviously, he was an intelligent — strikingly intelligent person. He was someone who loved to assert his own importance. He loved to brag about his great accomplishments. He loved to dominate a conversation. It’s possible towards the end of his life he may have had a drinking problem. I tried to get authoritative word on this. Probably I didn’t realize it. When I’m — I — Although I’ve taught this course before, before I give every lecture I actually go over it and kind of redo it and then I research things so before I come to class I’m actually having these random — It’s like a big game of Trivial Pursuit. Was Thomas Paine really drunk? Research, research, research. Okay. Maybe not so much. What happened to the body? Oh. We still don’t know. Okay. Okay. So I have these weird Trivial Pursuit moments in preparation for the course here. So, maybe drunk, maybe not, a slight drinking problem. Historians disagree. Either way, he was born in England in 1737. Supposedly the cottage that he was born in was literally in the shadow of a place of execution, so the dark hand of the State was looming over the cottage of Thomas Paine. He was born poor. His father was a stay-maker. Paine did go to grammar school and he liked learning, but at the age of 12 he was pulled out to be apprenticed to his father. As a young man, he had a number of different trades. None of them were enormously successful. I think for a little while he might have been a sailor. I think he was a minor officeholder. I think he was an excise man in England for a little while. In his spare time he liked to go to public lectures in London, and that’s where he met men like Benjamin Franklin. And Franklin ultimately proved important to Paine, because Paine ended up doing what a lot of sort of vaguely rootless people in England might have decided to do. He decided to try his luck in the American colonies where there seemed to be some opportunity for self-promotion, for sort of making something of yourself. But before setting off, Paine did an intelligent thing, and that is, he made an appointment with Franklin. And Franklin did an important thing. He wrote a letter of recommendation for Paine. And a letter of recommendation in this period was kind of a magical thing because, if you think about it, unlike now where there are five million ways in which we all can check on each other, there really weren’t ways in which one person knew anything about a stranger or could verify or check on who some complete stranger was. There’s a reason why the early nineteenth century is the age of the con man. Right? It’s really easy for someone to drift into town, claim to be somebody, no one has a way of checking, and then the person can drift out, taking various amounts of money and belongings with him. So letters of recommendation were kind of magical because basically they represented one person vouching their reputation for another. The person who wrote it said, ‘I’m writing this letter for Mr. Paine. I, Mr. Franklin, am writing for Mr. Paine and I’m introducing him to your attention and wish that you will introduce yourself to him and show him around Philadelphia’ — seemingly a basic statement, but Franklin was basically saying, ‘I’m — Here’s my reputation. I’m vouching for this guy so you could — you can get to know him. You can trust him because I’m recommending him.’ So it was a smart move on Paine’s part. It was a nice thing for Franklin to do, and in the letter that Franklin wrote he referred Paine to his son-in-law, Richard Bache, in Philadelphia. So Paine arrived in America in late 1774, but apparently the whole overseas passage was pretty horrible so he was pretty much out of commission until January 1775, and at that point when he was up and about, Bache offered to introduce him into the local literary and political scene. Now what happened next is a really good case for the importance of serendipity and the importance of bookstores. Okay. So Paine liked to hang out in this one local bookstore. Apparently he went there every day. Okay. That’s the local literary scene — [laughs] the bookstore — and he befriended the owner of the bookstore and the owner eventually invited Paine to be the editor of a new journal that he wanted to start, that he was calling the So Paine wrote for the for a while and he wrote a bunch of different kinds of things. He wrote fiction. He wrote essays. He wrote social commentary. As an example, he wrote a piece on British cruelty in the East Indies and Africa and against native Americans, writing, quote, “When I reflect on these [examples of cruelty] I hesitate not for a moment to believe that the Almighty will finally separate America from Britain. Call it Independence or what you will, if it is the cause of God and humanity it will go on.” Now considering — I’m going to talk a little bit more about the fact that people aren’t really talking about independence at this point, so that’s a pretty bold statement before Now one thing was noticeable about Paine’s writings. And that is that when they seemed to strike at issues of American liberty, even indirectly, even seemingly through metaphor — as in one essay that talked about British domination of India but everybody assumed India must really be the North American colonies — whenever he was referencing any of that sort of thing, sales jumped. Everyone wanted to read those essays. And ultimately it was some of those essays that brought Paine to the attention of Benjamin Rush. Rush went to that same bookstore, the magical bookstore, the center of Paine’s life. He happened to meet Paine at that same bookstore — so the moral is it’s a good thing to hang out in bookstores. And through their conversations Rush later wrote that at the time he observed that, quote, “Paine had realized the independance [sic] of the American colonies upon Great Britain” even at that time and that “he considered the measure as necessary to bring the war to a speedy and successful issue.” So he meets Paine and one of the things he notices is well, this guy’s already kind of thinking about independence. Paine himself later wrote about his opinion of the colonies upon his arrival, and he said that the thing that most struck him was how loyal the colonists were to Great Britain, and this is, Paine’s words here. “I found the disposition of the people such, that they might have been led by a thread and governed by a reed. Their suspicion was quick and penetrating, but their attachment to Britain was obstinate, and it was at that time a kind of treason to speak against it. They disliked the ministry, but they esteemed the nation.” I think that’s a really important point: “They disliked the ministry but they esteemed the nation.” “Their idea of grievance operated without resentment, and their single object was reconciliation … . I viewed the dispute as a kind of law-suit. I supposed the parties would find a way either to decide or settle it. I had no thoughts of independence or of arms. The world could not then have persuaded me that I should be either a soldier or an author.” Ultimately, it was the battle of Lexington that changed Paine’s view, and his life, as it changed that of many others. As Paine put it, “when the country, into which I had just set my foot, was set on fire about my ears, it was time to stir.” And so it’s at this point that Paine begins to tinker with the idea of writing a pamphlet. And apparently he spoke with Benjamin Rush about it, and Rush later recalled in a letter to a friend that he offered Paine one overall piece of advice at the outset of the project. He said to Paine, “there were two words which he should avoid by every means as necessary to his own safety and that of the public,” and the two words were “independence” and “republicanism.” Okay, and if you think about he didn’t listen to that advice at all. And as a matter of fact it’s impossible to know what went through Paine’s mind at that moment. He certainly — He knew the colonies were, as he put it, on fire, he knew that popular sentiment was building even against the King, but knowing his personality it’s entirely possible that if Rush said to him, ‘Whatever you do, don’t mention independence,’ that Paine’s reaction might have been well, that’s at the center of it, isn’t it? So that’s it; that’s going to be what I write about, isn’t it, and it’s going to be independence. And he might have deliberately done the precise thing he was asked not to do, and focus on the most controversial issue that seemed to be at the very heart of the controversy that seemed to be, certainly to Paine, lurking right underneath the surface of this prevailing constitutional argument. So Paine wrote the pamphlet, he read parts of it to Rush as he did, and is published in January 1776. And I did state correctly earlier that he wanted to call it and Benjamin Rush thought was a better title, and I agree with Benjamin Rush. I like better. [00:21:54]The pamphlet — The main argument of the pamphlet did three things. So number one, it basically refuted the prevailing ideas against independence. It went one step further and demonstrated the necessity of independence and how possible it was. And it demonstrated the stupidity and utter uselessness not only of the English monarchy but just of monarchies generally. This is a radical message, and it was written in a radically simple style aimed at being accessible to a broad audience. This was all the more radical given that American independence had not really been seriously discussed by the great majority of colonists with the exception of some extreme radicals who I’ve been mentioning now and again in lectures. So let’s look for just a minute at how Paine went through the three parts of his argument — and in a sense, there’s three parts of his argument, and the pamphlet itself has three sections. And the first section of the pamphlet centers on getting people past this ongoing constitutional argument about the proper relationship between the colonies and the mother country. And to accomplish this, Paine did something amazingly bold. He just tossed aside the entire idea of focusing on the English constitution as the context for determining the fate of America, and rather than going on and on and on with the same constitutional debate, he began his pamphlet with an attack not only against King George but also against the entire idea of monarchy. And he had a couple strategic reasons for choosing to do this. First, the Crown was the last remaining emotional and political link that was really tying the colonies to the mother country. By this point, the colonists had lost faith in Parliament, so Paine certainly knew that if he could strike at this last linchpin of colonial sentiment, he could advance the cause of independence. Second, if Paine could destroy the legitimacy not only of King George but also of the idea of monarchy overall, then the English constitution’s legitimacy would suffer as well, once again hopefully opening the way for independence. And then third, I think equally important, rhetorically Paine had a really good writer’s sense of pacing, and he knew that if he opened this pamphlet with this really dramatic challenge to all of the prevailing assumptions about government, and if he turned all of these assumptions on their head, he would pull readers in to his pamphlet and in to his argument immediately and hold them there for the center of his argument, which was the second section of the pamphlet, and that is really the part that focuses on independence. Independence at this point was a topic that people didn’t discuss openly. They didn’t talk about it in public. If discussed at all, it was discussed privately among friends because basically it amounted to treason. Paine’s dramatic introduction opened the way for him to introduce this really controversial topic. If the English constitution lacked legitimacy, well, what next? And his answer obviously is: well, independence, the obvious solution. Which then brings us to the third section of the pamphlet — and that is the future. Paine concludes the pamphlet by discussing just what Americans could institute to replace the English constitution, what kind of government they might be able to construct to replace what they were stripping away. Now throughout his work Paine hammered away at old ideas and propounded new ones. He argued that America was distinct from England, that it was multicultural, that it actually was more the child of Europe than the child of England. He promoted American commerce. He promoted social mobility. He praised the innocence of the New World as compared with the corruption and decadence of the Old World. He struck at the trappings of monarchy, things like hereditary privilege and court intrigue. He was an individualist arguing that society was made of individuals who should all be able to strive for their own good. He wasn’t arguing that families or patron-client relationships should define society any longer. He depicted government as a kind of necessary evil that was prone to create bureaucracies and privilege. As he put it, “Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence,” so it’s the price we pay for being flawed beings. And he seemed to speak of an American millennium, speaking of America as God’s chosen people. Paine argued that America’s success was linked to the success of all humankind, that the American colonists could launch a worldwide democratic revolution. And, as he put it — I’ll quote it again, but I think maybe it was the first lecture that I quoted this as my sort of random inspirational sentences from random guy from the eighteenth century. This is where this comes from. It’s the statement about beginning the world anew: “[W]e have every opportunity and every encouragement before us, to form the noblest purest constitution on the face of the earth. We have it in our power to begin the world over again….The birthday of a new world is at hand.” That’s millennial talk there. The power of the pamphlet wasn’t just in its argument or in specific points of argument, but rather, it was in the way that it reversed prevailing assumptions. Paine forced readers to consider a whole new way of looking at the impending crisis — and actually at the entire imperial system. He laid bare assumptions that had led colonists to resist independence, and then by exposing these biases and holding them up to scorn, he forced people to think beyond what they had thought before. So basically the old paradigm had been: liberty can survive among brutal and self-interested men only through a balance of institutionalized forces so no one can monopolize the power of the state and rule without opposition. So monarchy, nobility, and the people have an equal right to share in the struggle for power; complexity in government in this sense is a good thing; simplicity allows for monopolization. Well, Paine argues, complexity is not a virtue in government. It simply makes it impossible to tell who is at fault. Paine charged that the complexity of the British government was designed to serve the monarchy and the nobility, that the King did nothing but wage war and hand out gifts to his followers, and that this entire idea of British constitutional-institutional balance was a fraud. Now the boldness of this message becomes clearer when you compare it with some other pamphlets of the time, many of which were aimed at exploring difficult questions — right? — constitutional issues, and then coming up with recommendations. isn’t about exploring difficult constitutional questions. It aimed to, quote, “tear the world apart.” This pamphlet did not have the kind of rational tone and lawyerly, precise logic and high scholarship that you see floating through a lot of the other pamphlets of this period. And the tone was part of why the pamphlet ended up being so effective. Paine didn’t use legal arguments. He didn’t invoke legal authorities. He assumed that his readers would have some kind of limited knowledge of the Bible. He didn’t use a lot of Latin, and if he did use Latin he tended to follow it up with an English translation. He used really straightforward syntax, a really simple vocabulary. As he himself explained it: “As it is my design to make those that can scarcely read understand, I shall therefore avoid every literary ornament, and put it in language as plain as the alphabet.” So what he wanted to write he said was, quote, “simple facts, plain arguments, and common sense.” Sometimes it was Paine’s irreverence in comparison with other pamphlet writers that made his writing seem so effective. So for example, writing about the origins of the English monarchy and William the Conqueror, Paine wrote, “no man in his senses can say that their claim under William the Conqueror is a very honorable one. A French bastard landing with an armed banditti, and establishing himself king of England against the consent of the natives, is in plain terms a very paltry rascally original.” Okay. It’s not your typical pamphlet. Sometimes he used really straightforward language just for shock value, trying to make his point by — trying to upset prevailing ideas — by saying something in a shockingly straightforward and irreverent manner. And that’s obviously going to be really effective if he was talking about the King — to use sort of shockingly irreverent language. So for example, he really tried hard to dehumanize King George III, writing for example, he has “sunk himself beneath the rank of animals, and contemptibly crawls through the world like a worm.” Okay. [laughs] That’s pretty irreverent language. “Even brutes do not devour their young.” Okay. That would have been really shocking [laughs] to someone to read at the time, that that’s a description of the King. Or he used sarcasm, as in this sentence. Now I mentioned this sentence — I don’t know — in the first — one of the early lectures. I talked about a sentence that I really liked and I accused Benjamin Rush of cutting it out of the pamphlet, and I’m here to redeem Benjamin Rush because when I looked this up today to double check on myself what I discovered was, this is actually Benjamin Rush’s favorite sentence and Benjamin Franklin struck it out. [laughs] So it was in the draft but it didn’t make the final printed copy of and this is the sentence. Okay. “A greater absurdity cannot be conceived of, than three millions of people running to their seacoast every time a ship arrives from London, to know what portion of liberty they should enjoy.” I think that’s a good sentence. I agree with Rush. I think Franklin had it wrong. I think that’s good sort of pointed sarcasm, so I’m sorry it didn’t make the final printed version. Rush is right. So sarcasm — effective — irreverence, shock value — all effective. Even just emotion, even Paine’s emotion, was effective because it was so strong, because he was so passionate, and because he was so straightforward, as in a sentence like this. “Every thing that is right or reasonable [correction: “natural”] pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, ‘TIS TIME TO PART.’” Okay, dramatic, passionate, emotional language. So all of this stuff that I’m describing here, all of this rhetoric, all of this logic, all of the sort of rationale behind this pamphlet — this is popular culture but it’s not low culture. It may not have had really refined language but it had correct language. As Thomas Jefferson put it, “No writer has exceeded Paine in ease and familiarity of style, in perspicuity of expression, happiness of elucidation, and in simple and unassuming language.” Okay. By writing that, Jefferson achieved none of those things. [laughs] That’s like a really good example of how different Paine sounded, [laughs] — perspicuity of expression and happiness of elucidation. Okay, not in Jefferson does not sound like Thomas Paine. Popularity and Founder’s Reactions [00:33:47]Given all of this, the widespread popularity of the pamphlet isn’t surprising, and the first printing sold out in a few weeks. There were many re-printings, first in Pennsylvania, then in other colonies, and even ultimately in Europe. And all in all, a majority of the population of the colonies either read or received some kind of distilled version of it at their local tavern or in conversation, as presented by other people who had read it. By March of 1776, there had been 125,000 copies sold and by colonial standards that’s a mind-blowing number of copies, and here’s a way to sort of put that in context. At this period, even later, even in the 1790s, in a city like New York or Pennsylvania, a newspaper that would have been considered to have a big circulation number — like wow, that’s a really big newspaper — would have had a circulation of 1,000. Okay. So 125,000 copies is a lot of copies. That’s a pretty remarkable number. And sales were helped by the fact that the pamphlet was priced really low so that it could be bought by anyone, even the relatively poor. Now of course Paine wasn’t shy about his own accomplishments and he later told anybody who would listen that his pamphlet had enjoyed, quote, “the greatest sale that any performance [has] ever had since the use of letters.” [laughter] Okay. That’s not a modest man. It is the greatest-selling thing of all time. Okay. Okay, Tom, it’s important but come on. [laughter] Now of course not everybody cheered with the publication of There were many people who were enraged at what it dared to say about the English monarch, about the British constitution, about independence. Who was this guy anyway? Right? Who was he to promote independence? As Samuel Adams put it with actually unusual understatement for Samuel Adams — he said the pamphlet, quote, “has fretted some folks here more than a little.” It upset a lot of people. More direct criticism was issued by an English gentleman traveling in Virginia in his diary. He wrote, “A pamphlet called makes a great noise. One of the vilest things that ever was published to the world. Full of false representations, lies, calumny, and treason.” Now you may be surprised to hear that John Adams, ultimately a leading proponent of independence, did not like John Adams did not like the pamphlet. It wasn’t because of the first two parts. Right? He’s all for questioning the British constitution. He’s all for independence. That’s fine, but what really got Adams was the third section of the pamphlet, the section about what kind of government might we be able to create in the absence of the British constitution. This made Adams crazy, because to Adams and to many others at the time, good lawmakers were supposed to always be practical thinkers and they were supposed to be realistic about what a society could achieve. They were supposed to think about the realities of a society and then what would be politically possible, and this is not what he thought Paine was doing. He thought Paine was sort of blue sky, unrealistic, tossings off about possibilities, without thinking really hard about probabilities. So this is John Adams’ summary of This is true John Adams. Okay. quote, “a poor, ignorant, malicious, shortsighted, crapulous mass.” [laughs] That’s John Adams’ opinion of I have to add here for no reason except that when I was writing this I thought of it, and then this is my excuse to mention it in a lecture, and so I will. How many of you here have read Plato’s Some of you have read Plato’s Okay. John Adams really did not like Plato’s either, and for the same reasons. Right? He thought Plato was irresponsible. He hated Plato’s Jefferson was not a big fan either. He thought that — Actually, both of them thought that Plato was sort of vaporing about political ideals and not really thinking about realistic application to real people. So to these guys at this time the real challenge of what they’re doing is to match ideals and realities, and they didn’t think Plato was doing that at all. So this is what Adams [correction: Jefferson] first had to say about Plato’s : “While wading through the whimsies, the puerilities, and unintelligible jargon of this work, I laid it down often to ask myself how it could have been that the world should have so long consented to give reputation to such nonsense as this.” [laughter] Okay. He really doesn’t like Plato’s but he also just didn’t like Plato. So overall he said — he talked about how he read all of Plato’s works and he talked about oh, he had three Latin dictionaries and a German one and a French one just in case, and he worked his way through, and he said he learned only two things from all of Plato’s work. He learned, number one, that Benjamin Franklin stole an idea from Plato [laughter] — didn’t give him credit, [laughs] and number two, he learned that sneezing is a cure for the hiccups. [laughter] And he said, quote, “Accordingly, I have cured myself and all my friends of that provoking disorder, for thirty years, with a pinch of snuff.” Okay. That’s Plato to John Adams. [laughs] That’s it. So I just love that. I love that. It’s John Adams at his best. Okay. So away from Plato, back to For many people was kind of a conversion experience, and there are people that are fence sitters who maybe — might have had the makings of a radical and in reading the pamphlet or hearing of the pamphlet, they actually were radicalized by it. It was talked of everywhere. As Rush put it, “Its effects were sudden and extensive upon the American mind. It was read by public men.” It was “repeated in Clubs, spouted in schools, and in one instance delivered from the pulpit instead of a sermon, by a clergyman in Connecticut.” That’s a Connecticut moment. I’m always happy when we have little Connecticut or Yale moments. It was talked about everywhere. Its rhetoric was so powerful that for many it inspired them to stand back, examine their situation, and really loathe Britain for the first time — like oh, [laughs] I’ve never thought of loathing Britain before, but yet now I am. As George Washington wrote, was “working a wonderful change in the minds of many men.” In the end, regardless of whether one agreed or not with his argument, Paine’s pamphlet did one fundamentally important thing. He focused the prevailing colonial political conversation on independence. He lifted the argument above constitutional reckoning. He inspired others to write about the topic as well, sometimes for independence, sometimes against, but independence became now the topic to discuss. As a reader in Boston put it, “Independence a year ago could not have been publicly mentioned with impunity. Nothing else is now talked of, and I know not what can be done by Great Britain to prevent it.” Now Paine was all too happy to remind anyone who would listen about the significance of his pamphlet. He considered it his lifetime achievement. He wanted his tombstone to read “Thomas Paine, author of “ Of course, that was assuming he was going to have a tombstone which [laughter] he didn’t. [laughs] The poor guy. I didn’t think of that until this second — oh, bad irony. He said that regardless of whatever form he took in the afterlife, he would always know he had written Okay, but did cause independence? Okay. Paine clearly would have loved to tell you that it did. That’s the kind of conclusion you really can’t make, but clearly you can say it was so powerful, so widely read, so controversial that it shattered much of the psychological resistance to the idea of independence. And also on a more social level, invited an entire range of people into the political conversation that in some ways hadn’t really been included before, just by deliberately making this pamphlet available to as broad an audience as possible. And his message in a sense was fundamentally democratizing as well. Paine preached that any people can deliberate and decide how they are to be governed. And then they can act on that choice. Any people are capable of creating and implementing their own government. It’s a powerful message, and regardless of whether people agreed or disagreed about what government they should be creating, the ideas underlying that pamphlet in a sense were really revolutionary, in a sense, and certainly radicalizing, just at this moment when things are taking a turn, just at this moment when the King has declared the colonies in rebellion, and very soon we’re going to have Lexington and Concord. So you can see how we’re right at this moment where things are going to take a shift. partly timing-wise, came out at just the moment where it was going to strike and have the broadest impact. That is all I have for today. Have a good weekend. I will see you on Tuesday and we will move on to independence. We get independence next week. It’s very exciting. [end of transcript] |

COMMENTS

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Why were the battles of Lexington and Concord significant?, Why did the British army retreat from Boston in March of 1776?, What was the main effect of Thomas Paine's pamphlet, Common Sense? and more.

Who wrote Common Sense? Thomas Paine. Thomas Paine and Common Sense. A British citizen, he wrote Common Sense, published on January 1, 1776, to encourage the colonies to seek independence. It spoke out against the unfair treatment of the colonies by the British government and was instrumental in turning public opinion in favor of the Revolution.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like What was the historical significance of Thomas Paine's Common Sense?, Why was the Battle of Saratoga particularly significant in the American Revolution?, In France before the French Revolution, the Third Estate or commoner class included? and more.

Paine refuted the notion that Americans should be loyal to a mother country that he considered a bad parent. "Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families ...