- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Picture Show

Daily picture show, 'black in white america:' revisiting a 1960s photo essay.

Claire O'Neill

More than 40 years after the original publication date, The J. Paul Getty Museum has reissued Black In White America , a book by photojournalist Leonard Freed. The release corresponds with a new exhibition opening later this month; "Engaged Observers: Documentary Photography Since The Sixties" showcases the work of nine renowned photographers.

In the 1960s, Freed traveled the country providing in-depth coverage of America's race issues. But, rather than gravitating to violent outbursts and moments of tension, Freed photographed weddings and football practices and church services. Curator Brett Abbott explains in the book's foreward that Freed "found that his interests lay not in recording the progress of the civil rights movement per se but in exploring the diverse, everyday lives of a community that had been marginalized for so long."

The photographs are accompanied by Freed's diary-like text. And while many of the photos lack captions, that doesn't seem to matter. Freed was less interested in each individual instance, and more concerned with capturing the essence of an issue and a culture — a time and place. Somehow, even 40 years later, the photos still feel relevant.

| Subtotal | $0 |

|---|---|

| Tax | $0 |

W. Eugene Smith: Master of the Photo Essay

100 years since the birth of W. Eugene Smith, we take a look at the work of a remarkable talent who described his approach to photography as working “like a playwright”

W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith’s membership with Magnum may have been brief, spanning the years 1955-58, but his work left left a deep impression on many of Magnum’s photographers, as it has upon the practice of photojournalism generally. Smith is regarded by many as a genius of twentieth-century photojournalism, who perfected the art of the photo essay. The following extract from Magnum Stories ( Phaidon ), serves as a pit-stop tour through his most enduring and affecting works.

With “Spanish Village” (1951), “Nurse Midwife” (1951), and his essay on Albert Schweitzer (1954), “Country Doctor” is first of a series of postwar photo essays, produced by Smith as an employee of Life magazine, that are widely regarded as archetypes of the genre. The idea to examine the life of a typical country doctor, at the time of a national shortage of GPs, was the magazine’s, not Smith’s. Though it was preconceived and pre-scripted, with a suitable doctor cast for the role before Smith got involved, he was immediately attracted to the idea of its heroic central character. He left to shoot the story the day he first heard about it – and before it was formally assigned, lest his editors decide to allocate the job to a different photographer.

Country Doctor

He described elements of his approach in an interview for Editor and Publisher later the same year:

“I made very few pictures at first. I mainly tried to learn what made the doctor tick, what his personality was, how he worked and what the surroundings were… On any long story, you have to be compatible with your subject, as I was with him.

I bear in mind that I have to have an opener and closer. Then I make a mental picture of how to fill in between these two. Sometimes, at the end of the day, I’ll lie in bed and do a sketch of the pictures I already have. Then I’ll decide what pictures I need. In this way, I can see how the job is shaping up in the layout form.

When a good picture comes along, I shoot it. Later I may find a better variation of the same shot, so I shoot all over again.”

"When a good picture comes along, I shoot it. Later I may find a better variation of the same shot, so I shoot all over again."

- w. eugene smith.

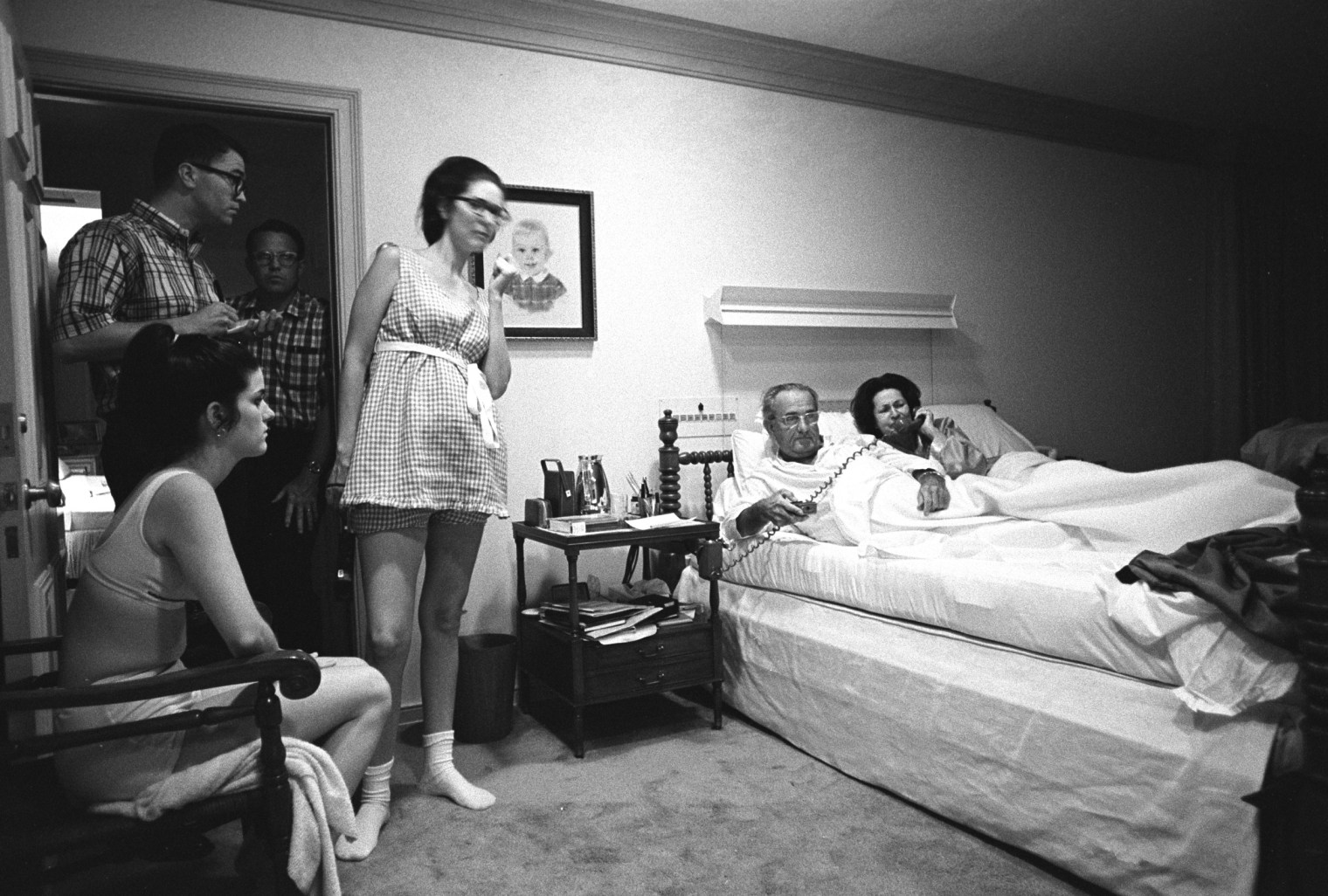

Central to his method was his seeking to fade “into the wallpaper”. De Ceriani, the subject of the story and the one constant witness to his working approach, recalled in an interview with Jim Hughes, Smith’s biographer, that after a week Smith “became this community figure. He may not have known everybody, but everybody knew who he was. And you fell into this pattern: he was going to be around, and you just didn’t let it bother you. He would always be present. He would always be in the shadows. I would make the introduction and then go about my business as if he were just a doorknob.”

Smith set about what might have been a straightforward assignment with a demanding intensity. “I never made a move where Gene wasn’t sitting there,” Ceriani explained; “I’d go to the john and he’d be waiting outside the door, so it would seem. He insisted that I call when anything happened, regardless of whether it was day or night… I would look around and Gene would be lying on the floor; shooting up, or draped over a chair. You never knew where he was going to be. And you never knew quite how or when he got there. He would produce a ladder in the most unusual places.”

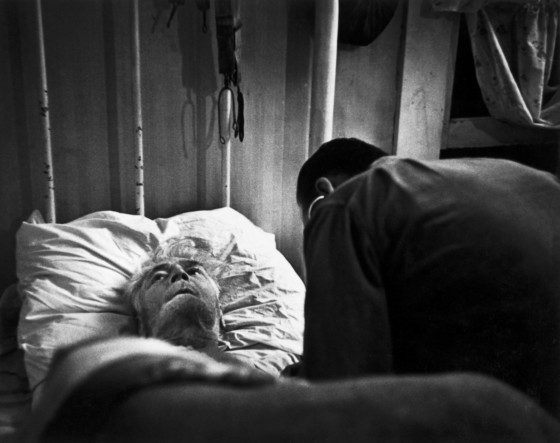

For a four-week shoot, Smith selected 200 photographs for consideration by Life , and while he clearly had some influence over the layout, he did not control it. It did not live up to his expectations; in the interview with Editor and Publisher, Smith stated that he was “depressed” thinking about just how far short it fell. It’s not clear how different it might have been had he done the layout himself. We know that the prints he made were rejected by Life ’s art director, on the grounds that they were too dark and would not reproduce well on the magazine’s pages. Smith’s vision was darker in other regards too. Photographs not featured in Life’ s layout, but reproduced or exhibited later, include a powerful series of 82-year-old Joe Jesmer being treated following a heart attack – an old man whose face terrifyingly reveals the apparent consciousness of his imminent death. Smith also chose, for his own exhibitions, troubling photographs of Thomas Mitchell prior to his leg amputation, as well as other images more baroque than those selected by Life . But the two brilliant images between which the layout hangs – his opener of the stoical doctor on his way to the surgery under a brooding sky and his closer, showing Ceriani slumped in weary reflection with coffee and cigarette – clearly reflect Smith’s won intentions for how the story should appear.

It is in the sophistication of its narrative structure that Smith’s innovation lies. In recorded conversations between Smith and photographer Bob Combs in the late 1960s, he elaborated on the ingredients of his approach (referring here to another story, “Nurse Midwife”):

“In the building of a story, I being with my own prejudices, mark them as prejudices, and start finding new thinking, the contradictions to my prejudices, What I am saying is that you cannot be objective until you try to be fair. You try to be honest and you try to be fair and maybe truth will come out.

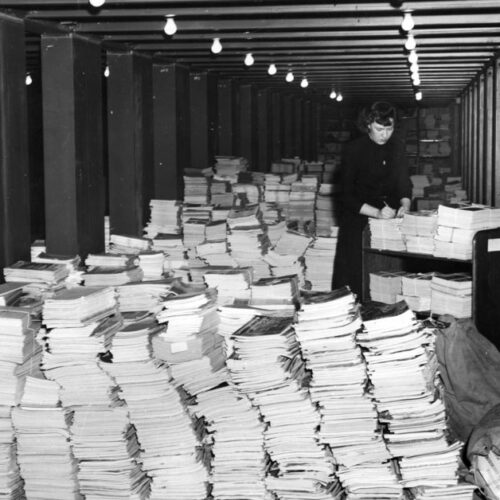

Each night, I would mark the pictures that I took, or record my thoughts, on thousands of white cards I had. I would start roughing in a layout of what pictures I had, and note how they build and what was missing in relationships.

"In the building of a story, I being with my own prejudices, mark them as prejudices, and start finding new thinking, the contradictions to my prejudices, What I am saying is that you cannot be objective until you try to be fair."

I would list the picture to take, and other things to do. It began with a beginning, but it was a much tighter and more difficult problem at the end. I’d say, ‘Well, she has this relationship to that person. I haven’t shown it. How can I take a photograph that will show that? What is this situation to other situations?’

Here it becomes really like a playwright who must know what went on before the curtain went up, and have some idea of what will happen when the curtain goes down. And along the way, as he blocks in his characters, he must find and examine those missing relationships that five the validity of interpretation to the play.

I have personally always fought very hard against ever packaging a story so that all things seem to come to an end at the end of a story. I always want to leave it so that there is a tomorrow. I suggest what might happen tomorrow – at least to say all things are not resolved, that this is life, and it is continuing.”

Smith refers to working “like a playwright”. Elsewhere he compared his work to composing music, but perhaps it is the literary reference that is most relevant to “Country Doctor”. His doctor is the emblematic hero of a drama that unfolds through several episodes – literally, acts. His opening and closing tableaux have all the content of soliloquies: single moments loaded with psychological detail and environmental description that frame the play. Unlike the experience of a play in the theatre where we watch it once, from beginning to end – we read the magazine essay back and first, at the very least reviewing the images again once we have read through it. The details of the doctor’s actions lend weight to the opening and closing portraits, and vice versa, so that the depth of its characterization reveals itself across the images as a group. It would not work if it were not wholly believable as a record of a real man, and real events. As such, its strength and its place in the history of the genre lies in the manner in which it combines a record of reality within an effective dramatic structure; in short, as a human drama.

Smith’s essay-making technique was not something he developed independently of the media that published his pictures. It began with essays produced in the early 1940s for Parade , where photographers were encouraged to experiment with story structure (without the tight scripting Smith later encountered at Life magazine) and where stories often focused on an attractive central character achieving worthwhile goals against formidable odds. Although Smith is on record as being in constant struggle with Life over its scripts – as well as its layouts, the selection of photographs, and the darkness of his prints – it seems appropriate to view his achievement as the product of a dialogue with the needs and practices of the magazine. The battles were over the details of particular decisions rather than over the mission or purpose. In fact, Smith wholly identified with the Life formula, taking and refining it to a new level of sophistication.

After Smith left life in 1954 – after several prior resignations, his final departure was over the editorial slant given to his essay on Albert Schweitzer – he embarked on his ambitious Pittsburgh essay. Working for the first time outside the framework of a magazine, with only a small advance from a book publisher, and encouraged by Magnum’s reassurance that he would find a worthwhile return from serial sales of independently executed essays, he believed that he was positioned to produce his best work yet. He wrote to his brother that he Pittsburgh essay would “influence journalism from now on”, and described in an application for a Guggenheim Fellowship that he “would recreate as does the playwright, as does the good historian – I would evoke in the beholder an experience that is Pittsburgh.”

It did not really work. Becoming a landmark in the ambition of the photo essay, and including some of his strongest photographs, the Pittsburgh essay nevertheless failed to be the symphony in photographs for which Smith strove, After four years of work, it was finally published in the small-format Popular Photography Annual of 1959 , run as a sequence of “spread tapestries” – as he described his intended layout to the editor of Life . He titled the essay Labyrinthian Walk, indicating the story was less about the city than a portrait of himself locked in a life-or-death struggle with a mythical demon. Although he himself was responsible for the layout, he judged it a failure. The dream – or necessity – of Magnum failed also. He did only two minor assignments in the time he was a member, and he left completely broke, his family in poverty, with Magnum itself smarting from the investment it too had ploughed into the Pittsburgh project.

After the “Country Doctor” story was published, Smith declared that he was “still searching for the truth, for the answer to how to do a picture story”. Later, in 1951, he stated in a letter to Life editor Ed Thompson, “Journalism, idealism and photography are three elements that must be integrated into a whole before my work can be of complete satisfaction to me.” In 1974, 20 years after embarking on the Pittsburgh essay, Smith was vindicated with the triumphant artistic and journalistic success of “Minamata”, his story about the deformed victims of the pollution by the Chisso chemical plant in Japan. The story became a new paradigm for the possibilities of photojournalism, in part because of its unambiguous moral purpose.

Theory & Practice

Henri Cartier-Bresson: Principles of a Practice

Henri cartier-bresson, explore more.

Arts & Culture

Bitcoin Nation

Thomas dworzak.

Magnum On Set: Charlie Chaplin’s Limelight

The Battle of Saipan

W. Eugene Smith’s Warning to the World

In Pictures: 75 Years Since the Start of the Pacific War

Magnum photographers.

The Pacific War: 1942-1945

Past Square Print Sale

Conditions of the Heart: on Empathy and Connection in Photography

The New York Times

Magazine | the rooms they left behind, the rooms they left behind.

Photographs by MITCH EPSTEIN DEC. 21, 2016

After the deaths of these 10 notable people, The New York Times photographed their private spaces — as they left them.

Photo Essay

Quiet places.

Reno’s mother began building the family home, near the Florida Everglades, in 1949, long before Miami’s suburban sprawl crept into the area. Reno moved here at age 14, and — apart from stints in Tallahassee and as U.S. Attorney General — lived here for the rest of her life. The bed and other antiques once belonged to her maternal grandparents. ‘‘I don’t know how old they are,’’ says her sister, Maggy Hurchalla, ‘‘but I’ve known them for as long as I remember, and I just turned 76.’’

Across the length of 2016, the photographer Mitch Epstein — known for making careful large-format images that draw rich meaning out of places and objects — arranged to visit the living and working spaces of some of the monumental figures we lost this year. The goal was to arrive not long after each person’s death, in those days when a person’s spirit can still seem palpable somewhere among their rooms and their things — as in his photograph of the writer Jim Harrison’s studio, where the items on a bedside table seem as if they were set down only moments ago.

As he took in each space and created these subtle, multilayered photographs, Epstein was especially struck by the number of rooms that felt like places of freedom, with each figure creating his or her own unique interior world. “They’re not just spaces,” he says. “They’re actually sanctuaries. That’s the word that comes to mind.” TEXT BY NITSUH ABEBE

Marisol’s sculpture, with its Pop Art vibrancy and folk-art intimacy, made her a one-name celebrity in the 1960s art world, and she purchased her TriBeCa loft and studio in 1979, before the neighborhood’s rapid redevelopment. With shades drawn, the stillness of this sitting area now stands in contrast to the bustle and gleam outside. In the center is a flat file for smaller drawings; at left, a preliminary drawing for the 1989 sculpture ‘‘John, Washington and Emily Roebling Crossing the Brooklyn Bridge for the First Time.’’

‘‘He also had an upright bicycle out there,’’ says Shandling’s friend Bruce Grayson of this nook in the comedian’s Brentwood home. But Shandling’s great love was boxing: He co-owned a gym in Santa Monica and sparred, when in good health, multiple times a week. In interviews, he’d compare the sport to his career in comedy. ‘‘It’s getting over that fear,’’ Grayson says. ‘‘He used to make that metaphor all the time — boxing taught him how to bob and weave onstage, to be agile and not get back on his heels.’’’

After a stroke in 2009, the self-taught artist began working in the back of Dial Metal Patterns of Bessemer, Ala., a fabrication company owned by two of his sons. Dial, who grew up in the Depression-era South, spent much of his adult life laboring in factories and used industrial materials and other castoffs in many of his artworks. When his sons first opened the studio after Dial’s death, unfinished work still hung under fluorescent lights on one of the pressed-wood walls.

‘‘Jim liked naps,’’ says Joyce Harrington Bahle, who assisted the celebrated writer for 37 years — hence the bed in the small writing studio he kept behind his Montana home. On one wall hangs ‘‘A Correlated History of Earth,’’ charting the planet’s development over 4.5 billion years; on another, a painting, by Harrison’s friend Jill Eggers, of a thicket. Bahle says Harrison always saw thickets as places of refuge. Outside, looking out toward the Absaroka mountains, is the solitary bench where he liked to begin each workday.

It was some months after the musician’s death that this photo was taken, in the Galaxy Room of his Paisley Park Studios — a lounge space attached to the studio’s production facilities. The astronomical images are painted on the walls and lit by blacklights in the ceiling fixtures; throughout the studio space are copious candles, incense burners and other mood-setting flourishes.

Wiesel’s home study in Manhattan is packed with plenty of mundane, familiar needs — books and files, staplers and tape dispensers, papers and pens — but here, the eye is drawn to a sacred object: Wiesel’s personal Torah scroll, housed in its own bookshelf cabinet.

‘‘I always felt when I was visiting that I was getting to hang out with Edward and be in this great museum at the same time,’’ says Sam Rudy, Albee’s longtime friend and publicist. The playwright was a passionate collector of art, and filled his Manhattan loft with countless pieces — like Walt Kuhn’s ‘‘Helen’’ (1929), the striking portrait seen here. This nook was where Albee read and took phone calls; Rudy also recalls arriving for appointments and finding the ‘‘notoriously punctual’’ writer on his worn leather chair, jacket draped over one knee, ‘‘in full waiting mode.’’ ‘‘There was always tremendous still and quiet and calm in the loft,’’ he says, “except when there was a party. It was not unlike a museum in that regard.’’

The historian and anthropologist — one of the last living people to have spoken with anyone present before the Battle of the Little Bighorn — kept a second office in the garage of his home on the Crow Indian Reservation. The items and archives inside track both the history of the Crow Tribe of Montana and the life of Medicine Crow himself. Portraits on the left depict Crow warriors and leaders, including Bull Chief, Medicine Crow’s great-grandfather, believed to have been born in 1825. A single bare bulb hangs over the desk.

The Connecticut home where Wilder spent the last decades of his life was owned first by his third wife, Gilda Radner, who left it to him after her death. He and his next wife, Karen B. Wilder, made many renovations, including some whimsical designs in the garden. This past May, as Wilder struggled with Alzheimer’s disease, a tree sculptor was invited to leave this portrait on the grounds, working in concert with the actor himself. ‘‘Really,’’ his widow says, ‘‘it was the last artistic collaboration of his life.’’

Mitch Epstein is a fine-art photographer based in New York City. His forthcoming book, “Rocks and Clouds,” will be published by Steidl in the spring.

What you learn when you ride shotgun with the former attorney general.

C entral Florida is the in-between you make go away by pressing a little harder on the gas. Orange groves at dusk, sky full of pastel color, and Janet Reno is driving the car, a rental. It’s 2002, Reno is running for governor of Florida, and I’ve spent days riding shotgun with her, reporting for this magazine, accompanying her to various campaign events — most of them populated by older women, bright and warm women with structures of freshly coifed hair, who fawn over Janet Reno, who knew her mother, an investigative reporter for The Miami News. To them, Janet Reno is the daughter who left Florida to fix America, serving eight controversial years as attorney general under Bill Clinton, and has now returned to fix the Sunshine State.

Edgar Mitchell

An astronaut goes to the moon and makes it most of the way back.

There is a photograph of the astronaut Edgar Mitchell emerging from the Apollo 14 capsule, a ragged cone of scorched metal and shredded foil bobbing in the South Pacific 880 miles off the coast of American Samoa. A wetsuit-clad Navy swimmer is helping him out of the access hatch and into an inflatable raft. Mitchell, dressed in an olive-drab flight suit and a biological mask, steadies himself with his left hand on the door frame. He is 40, with the receding hairline and blandly gentle affect of a family dentist. It is Feb. 9, 1971, and he has just had an epiphany.

Late at night, she offered advice to the anxious and the lovelorn.

You had to have a little bit of patience and a lot of luck to catch Miss Cleo. She appeared on TV only late at night, after the second round of reruns and right before the white fuzz took over the screen. Miss Cleo was usually sitting at a table, draped in a glorious amount of fabrics, a stack of tarot cards in front of her, candles and incense burning behind her. “You have questions, I have the answers,” she would intone knowingly in her Jamaican patois, before singing out the words that would become her signature catchphrase: “Call me now!”

David Bowie

Extracts from an endless list of reasons to appreciate an endlessly restless artist.

... and it is a collaboration that makes me additionally thankful for this splendid enigma: What did you and Eno chat about in between takes? Your favorite Hammer films? Is a hot dog a sandwich, yes or no?

Jack T. Chick

The fundamentalist zealot whose cartoons also inspired underground comics.

He drew inspiration from a painting he kept on display in his studio, a depiction of souls plummeting into hell — a constant reminder of the multitudes that even his pen, wielded by a cartoonist for Christ, could not save from eternal fire. Still, Jack T. Chick did what he could, illustrating and mass-marketing his palm-size booklets that told different stories with the same message: If you do not accept Jesus Christ as your savior, you are hellbound.

Pedals the Bear

By walking on two legs, he made us rethink the divide between human and animal.

In 2003, the State of New Jersey allowed a black-bear hunt for the first time in 33 years. The resulting controversy, still smoldering today, seemed irresolvable: Depending on whom you asked, the hunt was either sadistic blood sport or noble tradition. Two sociologists, Dave Harker and Diane C. Bates, scrutinized 10 years of clashing regional newspaper editorials and letters to the editor and concluded that the two sides did not even seem to be arguing about the same animal. Actual bears had been replaced by “competing social constructions” of bears. Those in favor of the hunt imagined the animals as “menacing threats” that needed to be controlled; those against saw them as docile and benevolent creatures that just wanted to “live in peace.”

William A. Del Monte

What do we lose when the final survivor of a mass disaster dies?

When the shaking stopped on April 18, 1906, William A. Del Monte’s mother bundled him in a tablecloth and carried him out of the house and into the street, where her husband waited in a buckboard wagon. Amid San Francisco’s chaos — broken water and gas mains, shattered windows, twisted telegraph wires, six-foot chasms in the fissured earth — a horse began hauling the family from their North Beach neighborhood to the ferry terminal by the Embarcadero. Dawn was breaking. Small fires were beginning to burn. Houses, tipped diagonally, seemed on the verge of collapse. The city’s power was down, and its supplies of fresh water were mostly gone.

B. 1944 & 1953

Frank sinatra jr. & ricci martin.

When you sing well — but not as well as your dad.

In 1963, the 19-year-old Frank Sinatra Jr. sang with the Tommy Dorsey band, just as his father had two decades before, though now Dorsey was seven years dead and The New York Times referred to the musicians performing under his name as a “ghost band that has become the nucleus of a ghost show.” The younger Sinatra was praised for how close his mannerisms and phrasing were to his father’s, but he was damned for lacking his father’s “creative presence.”

Natalie Cole

Every time she hit it big, something knocked her down.

T he song came gushing out like an open hydrant on a hot summer day, but for Natalie Cole, it was a complicated kind of high. Minutes before she heard her breakthrough hit, “This Will Be,” on the radio for the first time in 1975, she had scored a heroin fix and was tripping down 113th Street in Harlem. Drugs were a recent mainstay; she started using heavily in college, during the substance-fueled psychedelic era (she still managed to get her degree, in psychology). Music, meanwhile, was her birthright — after all, she was the daughter of Nat King Cole, one of the most beloved singers of the 20th century. Growing up in the exclusive Hancock Park section of Los Angeles, she could wander into the living room and find the likes of Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Sinatra gathered round the family piano. Now that she had a big hit of her own, fame was proving to be a stronger stimulant. She kicked heroin, married one of her producers, had a son, had more hits, appeared on “The Tonight Show.”

Kimbo Slice

A sports star is born in brawls.

In the online video that started Kimbo Slice on his way to bare-knuckle fame in 2003, two heavily muscled black men, each smooth-headed and stripped to the waist, square off in a backyard in Florida. Behind them you can see a grill, a satellite dish, palm trees. The web address of a porn site appears on the screen. Kimbo lowers his guard and taunts his opponent, Big D, who strikes Kimbo’s heedlessly exposed chin with no visible effect. Kimbo lands a blow that drops Big D to all fours in the sere grass. Staggering to his feet, Big D holds out open hands in a pacific gesture and says, “Chill, dawg, just chill.”

Zerka Moreno

She had little doubt that acting out experiences and feelings could save people — and help with child-raising.

When Zerka Moreno gave birth to her son, Jonathan, in 1952, she saw his arrival as a “golden opportunity.” How much more fun and creative might his life be, she wondered, if he were raised using therapeutic techniques like role-playing or talking to an empty chair? Each was pioneered by J.L. Moreno, Zerka’s husband and the founder of psychodrama, a form of therapy in which people act out their experiences and feelings in an effort to gain insight or achieve catharsis.

Antonin Scalia

He claimed objectivity when it came to originalism, but he was a skeptic about science.

I n 1981, the Louisiana Legislature passed a law that forbade public schools to teach evolution without also instructing students on “creation science.” The Creationism Act was challenged in court for breaching the constitutional wall between church and state, in a case that reached the Supreme Court in 1986. For seven justices, the decision involved a simple constitutional question. They saw the law as an effort to force religious belief into the science curriculum, and they struck it down.

Josephine Del Deo

She fought to preserve public land – and also some tarpaper shacks.

One day in the summer of 1953, Josephine Couch went with her boyfriend, Salvatore Del Deo, on an overnight trip to the dunes outside Provincetown. They’d been invited by a friend, a former chorus girl who went by Frenchie Chanel, to stay with her at her tar-paper shack by the water. That day, amid the compass grass and rose hips, Josephine, 27, felt the rest of the world vanish: Birds cried, but the white noise of surf and wind enforced a hush. At night, the moonlight caused the dunes to glow. Josephine fell asleep in the arms of Salvatore, whom she married that fall, to the cooing of a dove.

Ruth Hubbard

She was grateful simply to be a female biologist — until she got mad about needing to be grateful.

She was lucky , she believed, to be taught by “Harvard’s great men.” At 17, Ruth Hoffman was freshly enrolled at Radcliffe, the women’s college affiliated with Harvard, and keen on studying biochemistry. It was 1941. The two institutions had separate campuses but shared a faculty. Harvard professors lectured their male students and were then obliged to repeat it all to the smaller, all-female classes at Radcliffe. That teaching women was a chore, even an insult, was something Hoffman read on their faces. Her professors did little, she felt, to hide their disdain.

Sirdeaner Walker

Her son’s suicide turned her into an activist.

At 11, a boy is a dangerously ideal target for bullying: His horizons are limited, his sensitivity is ripe, his reactions are hot.

His talent — and his persona — may have been heaven-sent.

F amous and influential musicians die every year, but 2016 was bewildering. David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Prince, Leon Russell, Phife Dawg ... it’s as if we walked out to look at the stars and found major constellations gone. Who had even gotten over Lou Reed yet?

Afeni Shakur

Long after her son was killed, she became a source of comfort for other grieving mothers.

On the second day of the first Circle of Mothers retreat, in 2014, Afeni Shakur approached the stage to speak to the assembled crowd. Some days, it felt as if America was brimming with grieving mothers, so the event’s founder, Sybrina Fulton, wanted to gather many of them together in the hope that they could help one another move forward. Her son, Trayvon Martin, was shot and killed two years earlier. Shakur’s son, the rapper Tupac Shakur, had been dead for almost 20 years.

Katherine Dunn

She couldn’t have guessed how passionately misfits would embrace ‘‘Geek Love.’’

Carnival proprietors taking drugs and poisons to intentionally breed baby freaks: That’s the unvarnished core of Katherine Dunn’s third novel, 1989’s “Geek Love.” The Binewski Carnival Fabulon needs a boost, and Aloysius and Crystal Lil Binewski hatch this twisted plan to turn things around. Lil births a boy with flippers, beautiful Siamese-twin sisters joined at the waist, an albino dwarf hunchback and a boy with telekinetic powers. It hardly sounds like a universal cipher, the kind of humanist tale that attracts readers over time. Yet somehow this strange, singular book has spent the 27 years since its publication doing just that, speaking clear and true to a certain kind of reader.

Alisa Bellettini

The outsider whose “House of Style” brought high fashion to a generation of clueless teenagers.

The year 1989 was a good time to be 13 and have your MTV. The channel gave you the recipes for being chicer, more alternative, more you; for being gayer, blacker, more confrontational; for being cooler , basically. Perhaps it was your meal plan: “Yo! MTV Raps” for breakfast, “120 Minutes” for a midnight snack. And for dessert, “House of Style.”

Dana Raphael

Investigating why American women did — and did not — breast-feed.

On the 7:02 a.m. commuter train from Fairfield, Conn., to Manhattan, a woman with scarlet lipstick and chestnut hair slid beside a businessman reading his newspaper. “May I ask you a question?” she said. “What do you think about breast-feeding?” This was the mid-1950s. The woman was Dana Raphael, an anthropologist, a protégée of Margaret Mead and an outspoken feminist who, a decade before Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique,” refused to take her husband’s name and shunned the conventional wedding her mother planned. She initially also had no intention of following the de rigueur practice of bottle feeding. But after she tried but mostly failed to nurse her firstborn son, she began an anthropological quest that would end up spanning decades: Why was breast-feeding more successful in some cultures than in others?

Muhammad Ali

A fighter who showed us confidence — beautiful, astonishing, superheroic, infectious levels of confidence.

T here’s a story about Muhammad Ali that might have been lost to history, disappearing among all the other Ali esoterica, but for The Los Angeles Times photographer Boris Yaro. On Monday, Jan. 19, 1981, Yaro heard reports of a suicidal jumper on the radio. His editor wasn’t interested, but Yaro drove over to Los Angeles’s Miracle Mile regardless, where he found a young black man in flared jeans and a hoodie, perched on an office-building fire escape nine floors above.

She was an inspiration to female journalists, even middle schoolers.

Role models often appear with a thunderclap, a bright flash on a dark horizon, but can feel remote and evaporate just as quickly. Gwen Ifill was different. I didn’t know her, but I did get to know her influence, how it entered the lives of my students, especially girls and young women of color, whom I taught in Newark, N.J. For those like Jephtane Sophie Sabin and Isabel Evans, who watched Ifill on PBS over many years and eventually had the opportunity to meet her, Ifill created a warm and welcoming climate in which their aspirations had the chance to take root. Her impact wasn’t instant but played out slowly over time, like the rain of a wet season.

B. 1928 & 1940

Jacques rivette & abbas kiarostami.

Born years (and worlds) apart, they were philosophers of cinema.

Jacques Rivette’s “Out 1” — a 12-hour film, completed in 1971 and all but impossible to see in its entirety until very recently — begins with an extended sequence that combines artlessness and high artifice. The members of an experimental theater troupe (one of two such entities in the film) participate in an exercise that consists of writhing and squirming on the floor while wordlessly moaning and keening. It’s the primordial soup from which the film’s elaborate and elusive narrative will evolve, a reminder that every story begins in chaos and noise. Cinema, like other art forms, imposes a capricious kind of order on the mess of human experience, and “Out 1” illustrates this principle with a characteristically Rivetteian blend of intellectual rigor and anarchic whimsy.

Michel Butor

A pioneer of the French new novel, he wrote in just about every genre.

When you hear that a writer you first came to know in your youth is still writing in his advanced old age, you are at first surprised, as though he has risen from the tomb to write the poem you are reading. Then, once you absorb this fact, you go on to believe, quite illogically, that he will not die after all — certainly not soon.

Coca Crystal

An idiosyncratic host who brought surrealism to public-access TV.

For nearly 20 years, Coca Crystal’s weekly public-access show began with her smoking a joint. The show’s title was a scrap of messy poetry, as unwieldy as the program itself: “If I Can’t Dance, You Can Keep Your Revolution.” It was a no-fi interview show featuring scribbled title cards and minor downtown celebrities; regular guests included a singing dog and a disheveled poet who recited his work in a tapioca-thick mumble. She dedicated one episode to “the second anniversary of the first nonstop balloon crossing of North America.” The show isn’t easy to characterize, but Crystal probably described it best: “an hour of talk, telephone and technical failure.” Every episode ended with her dancing to groovy music — a little shoulder sway, some finger snaps.

Pat Summitt

She made her statement about the power of women by relentlessly pursuing every victory.

D uring a Final Four basketball game against the University of North Carolina, on April 1, 2007, Pat Summitt, the coach of the University of Tennessee Lady Vols basketball team, found her team down by 12 points with 8:18 to go. She was fuming — her gold rings were dented from being banged on the parquet floor. Summitt was a screamer. She loved to win. Over 38 years at Tennessee, she won 1,098 games — more than any other coach in N.C.A.A. Division 1 history. She also understood winning as a far more potent and radical act than even the most rabid male football fans would understand while pounding their painted chests.

Bill Cunningham

‘I just wish I could do what he does.’

“Ran into Bill Cunningham on his bike, I just wish I could do what he does, just go everywhere and take pictures all day.” From “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” entry dated Thursday, May 17, 1984

Reader Stories

The lives they loved.

As part of the magazine’s annual The Lives They Lived issue, we invited readers to contribute a photograph and a story of someone close to them who died this year.

More on NYTimes.com

Advertisement

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

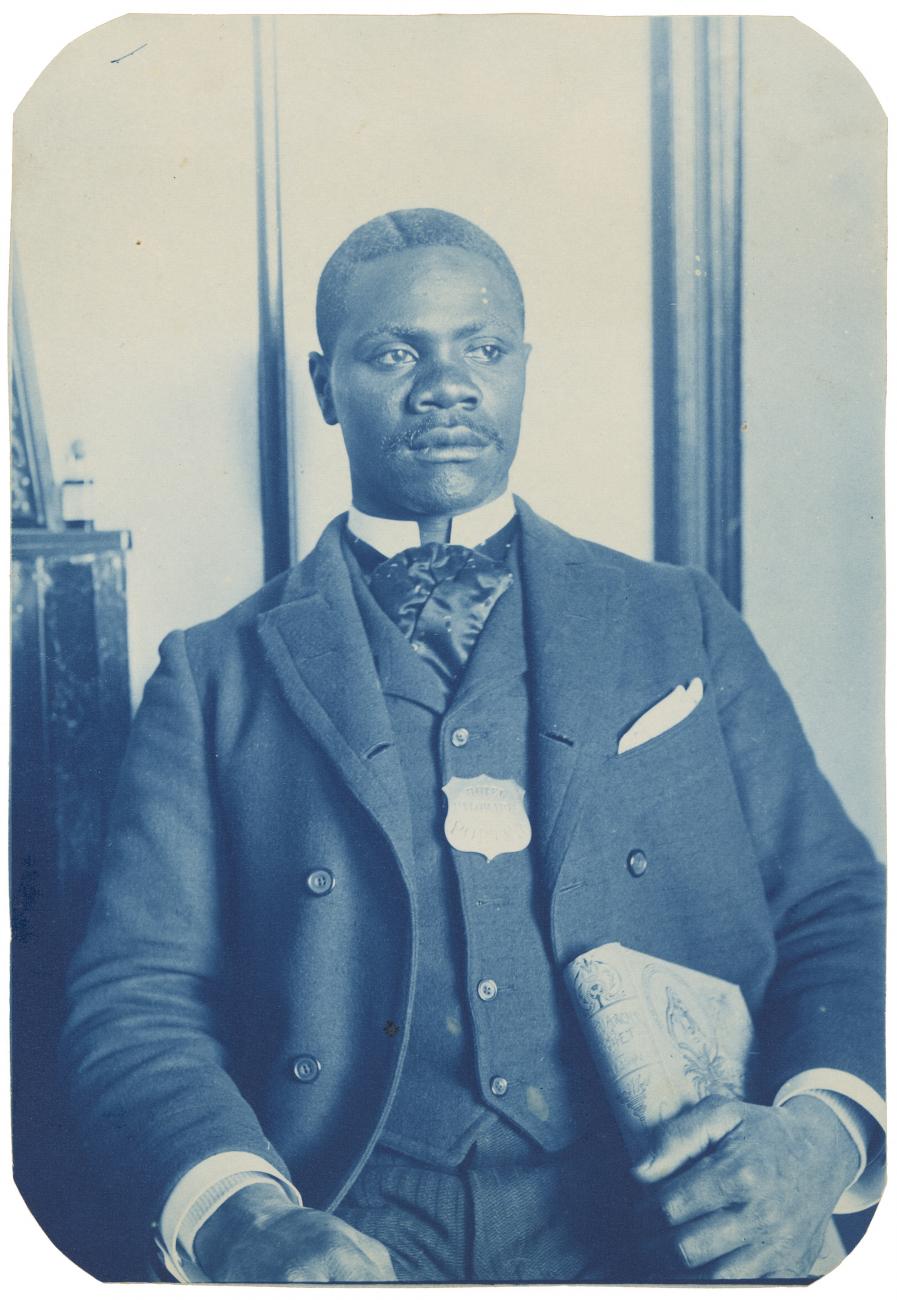

African Americans at Work

From enslaved workers in the 19th century to agricultural, industrial, and professional workers in the 20th and 21st centuries, African Americans have always been a vital part of the American workforce. The photographs from the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture below document African Americans at work from the 1860s to today.

Before and During the Civil War

Few photographic images of early American workplaces exist. After all, photography was not invented (in France) until the 1820s, was not introduced in America until the 1840s, and did not become an affordable amateur hobby until the 1880s. Most photographs of African Americans at work before and during the Civil War depict enslaved or recently emancipated workers on farms or plantations

No. 24: A Plantation Scene In South Carolina , ca. 1860. Photograph by S.T. Souder.

Women and children in a cotton field, 1860s. Photograph by J.H. Aylsworth.

Enslaved women and their children near Alexandria, Virginia, December 2, 1861, to March 10, 1862. Photograph by James E. Larkin.

Charleston Slave Hire Badges

From 1800 to 1865 in Charleston, North Carolina, slave hire badges were worn by enslaved individuals who were hired out by their enslavers to work for others. The enslaver paid an annual fee for the badge, providing revenue for the city of Charleston. Wages earned by the enslaved were often kept by the enslaver, but sometimes were shared with the enslaved. The badges served to identify those African Americans who were allowed to move about the city and to ensure that they only worked at jobs for which they were qualified, thus limiting competition with white workers. While some enslaved individuals learned skilled trades (“Mechanic”) useful to their enslavers in the plantation economy, a more common occupation was “House Servant.” These badges were public symbols of the hiring out system which allowed enslavers to allow their slaves a sense of autonomy, while maintaining control over them and profiting from their labor.

![photo essay 1960s A square copper slave badge set on point with clipped corners with die stamped and engraved text on the recto reading "CHARLESTON / No. [engraved] 103 / [stamped] FISHER / 1812".](https://nmaahc.si.edu/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2023-08/2016_166_23_001.jpg?itok=7haHWAqV)

Charleston slave badge from 1812 for Fisher No. 103.

Charleston slave badge from 1811 for Porter No. 27.

Charleston slave badge from 1800 for House Servant No. 354.

![photo essay 1960s This is a square metal slave badge with clipped corners. On the recto is text that reads ”CHARLESTON [stamped]” across the top. Under that is “1816 [stamped] / MECHANIC [stamped] / No. [stamped] 39 [punched] .”](https://nmaahc.si.edu/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2023-08/2022_5_31_001.jpg?itok=_-JdT4ty)

Charleston slave badge from 1816 for Mechanic No. 39.

Civil War Soldiers

During the Civil War , approximately 179,000 African American men served in the Union Army as U.S. Colored Troops and over 20,000 in the Union Navy. Although Black soldiers were involved in forty major battles and hundreds of skirmishes—and 16 were awarded the Medal of Honor—a disproportionate amount of Black soldiers were assigned work as laborers, digging ditches, building fortifications, and burying the dead.

Carte-de-visite of a sailor named Jim, late 19th century.

Tintype of a Civil War soldier, 1861–1865.

Photograph of members of the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, 1863–1865.

Colored Pickets on Duty Near Dutch Gap , 1864.

The Era of Jim Crow

The American nation was fundamentally changed—reconstructed—by three major social process in the century following the emancipation of four million enslaved individuals and the end of the Civil War. Each of these processes of change took decades to be completed and each changed the world of work for both Black and white workers.

First, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution—the so-called Reconstruction Amendments—abolished slavery across the nation, established the notion of “due process of law,” defined citizenship to include everyone born in the United States, extended voting rights to all Black men, and empowered the federal government to protect these rights for all citizens. Newly emancipated African Americans quickly understood that they needed to participate in both the federal legislative system and the court system to enlarge and protect their employment opportunities as integral to their civil rights. While some African Americans found success as professionals in the areas of law, education, and business, by far the great majority were forced into restrictive labor contracts as sharecroppers, while some were even forced into labor as convicts.

W. A. Neely's blacksmith shop in Laurinburg, North Carolina, January 1, 1910.

Four unidentified men in cooks’ uniforms on a porch, 1941–43.

J. J. Cotten Barbershop, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, ca. 1910.

Convict Labor

According to the Prison Policy Initiative , the United States houses more prisoners than any other country, of whom 38.5% are Black. Within these prisons, many are forced to work, contributing to a multibillion-dollar industry. Yet this form of labor is not included in official employment statistics of Black workers, causing a sector of Black labor to be heavily ignored.

After the passage of the 13th Amendment, involuntary servitude was abolished, “except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Soon after, states began passing laws, known as Black Codes, leading to mass incarceration of Black individuals. The system of convict leasing, where prisoners or prisons could legally be purchased to perform labor, began shortly after the Civil War. In some cases, this led to prisoners working on the same lands and for people that previously enslaved them. The impacts of these systems cannot be understated—in 1898, 73% of Alabama’s annual state revenue reportedly came from convict leasing. Many protested and spoke out against this system, calling it slavery under a different name.

Convict leasing was abolished in all states by the 1930s. However, with the fall of one form of prison labor came a new one—chain gangs. This form of incarcerated labor involved having chains wrapped around the ankles of multiple prisoners while they worked, ate, and slept outside of prison walls. These incarcerated workers labored at gunpoint or risked whipping—leading again to many protesting its use. By the 1950s, chain gangs were abolished in all states due to its violation of the 8th Amendment's “cruel and unusual punishment” clause.

Today, prison labor continues to be prevalent. In 1934, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order #6917 to establish the Federal Prison Industries, now called UNICOR. This program allows the use of incarcerated labor for the government. Incarcerated workers in prison, jails, and even immigration centers work to support their operations and maintenance of prisons. They also work in state-run prison factories, producing common goods and services.

Convict laborers at Swannanoa Cut, Asheville, North Carolina, ca. 1885. Photograph by Thomas H. Lindsey.

The second fundamental change in African American labor came through the laws and social customs that reinforced white supremacy and a system of “separate but equal” segregation—Jim Crow society. This also created a new hierarchy of occupations: those that were reserved for whites and those open to Black citizens.

Two unidentified women in uniform with toddler, Port Gibson, Mississippi, 1940. Photograph by Marion Post Wolcott.

Beautician brushing an unidentified women’s hair in salon chair, mid-20th century. Photograph by Rev. Henry Clay Anderson.

Grocery Store, 14th & U Streets , ca. 1945. Photograph by Robert H. McNeill.

Barbershop , ca. 1945. Photograph by Robert H. McNeill.

Pullman Porters

Pullman Porters occupied a coveted position in Black communities in the late 19th and early 20th century. These workers, typically Black men, would assist with luggage, maintain sleeping quarters, and serve passengers in the Pullman Palace Car Company’s luxury sleeping cars. The pay was higher than most other employers at the time, travel was possible, and many were able to move on to better jobs in hotels and restaurants.

However, the position did not come without discrimination and racism. George Pullman wanted Black porters, specifically those who were formerly enslaved, because he believed they would work under harsh conditions and would attend to every need of passengers. Porters were often called “boy” or “George” instead of their own names, and they were commonly berated or harassed by customers in the cars.

The Pullman maids were a lesser-known employee of the company: Black women who would clean Pullman cars and cater to guests. They typically worked with women, the elderly, and the infirmed. They often received lower wages from tips than Pullman Porters who worked in cars with businessmen and politicians.

Pullman Porter T.R. Joseph in uniform, ca. 1930s.

Preparing Dinner in the Dining Car Kitchen , mid-20th century.

Pullman Porter James Bryant in uniform, 1973.

Historically, a major sector of work for Black women was midwifery . This practice included caring for mothers and infants during childbirth. Black midwives often used tactics derived from African tradition and were seen very highly in their communities. Midwives were also incredibly important to enslaved communities, as they could keep records of ancestry and community ties. After the Civil War, Black midwives continued to be incredibly important, especially in rural Southern states. Notably, they did not just work for Black mothers, they also supported white mothers in their communities.

With the medicalization of childbirth, the practices of midwives began to be questioned and delegitimized. Maternal and infant mortality rates began to rise, and many blamed midwives. However, midwives had fewer instances of maternal and infant mortality than medical doctors. The passage of the Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Protection Act of 1921 made traditional midwifing more difficult with increased regulations, mandatory trainings, and supervision necessary to continue working in the field. Black midwives were often being taught by nurses with less training than themselves.

While leading to better health outcomes of mothers and infants, these regulations led to increased barriers for Black midwives to work in professional maternal healthcare. In particular, requirements to receive state licensing became an obstacle for many. In 2021, only 7% of certified nurse-midwives and certified midwives were Black . Some believe that these historical systemic barriers to Black midwives have contributed to the prominent Black maternal mortality rate seen today

Midwife standing next to woman in bed with bassinet to her left, mid-20th century. Photograph by Rev. Henry Clay Anderson.

Collection of the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Robert Galbraith, © 1987 Robert Galbraith

Midwife Susie Carey, 1940–1953.

The third change in Black labor that came about during the Jim Crow Era was the Industrial Revolution. This transition from a rural, agricultural society to an urban, industrial one, was driven by new technologies in manufacturing, agriculture, transportation, and communication, that created entirely new occupations and work processes.

Workers outside the Grendel Textile Mill, 1923–1924.

Student working a printing press, ca. 1935. Photograph by Lewis Wickes Hine.

Workers at the International Harvester tractor works, 1946–1948. From the series The Way of Life of the Northern Negro. Photograph by Wayne F. Miller.

Postal Workers

The United States Postal Service (USPS) plays an important role in Black labor history. As of 2022, almost 29% of the USPS was Black, making it one of the top employers of African Americans in the United States. The history of Black workers in the postal service can be traced to the institution of slavery, with many enslaved persons working as transportation contractors. However, rebellions in Haiti sparked fear in Southern whites, leading to Congress prohibiting African American mail carriers in the postal service until 1865. During the Civil War, the first known Black post office clerk was appointed, William Cooper Nell, in Boston, Massachusetts. He is also believed to be the first Black civilian employee of the federal government.

In 1914, the Civil Service Commission issued a new order requiring applicants for federal jobs to submit a photograph. These policies led to the founding of the National Alliance of Postal and Federal Employees (NAPFE) an independent, African American controlled labor union with a mission to eliminate discrimination and injustice in the federal service. The 1940s saw the passage of Executive Order #8802, which created the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC) to oversee claims of discrimination. By the 1960s, Black representation in the Postal Service was seen at higher leadership levels, with the three biggest post offices in the country having Black Postmasters. In 1971, the Postal Service adopted an Equal Employment Opportunity policy, which aided in the recruitment of minority and female applicants to the organization. Today, the USPS has the highest median annual and hourly wage within the top ten occupations with the highest proportions of Black workers. The wage gap is also narrower among postal workers than in the private sector.

A postal worker sorting mail into cubby holes, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1950. Photograph by Charles “Teenie” Harris.

A mailman outside of Rev. H.C. Anderson's photo shop, mid-20th century. Photograph by Rev. Henry Clay Anderson.

The Post-Civil Rights Era

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics , in 2019, 29% of employed Black Americans worked in education and health services. Another 10% worked in retail trade and 10% in leisure and hospitality. Less than 1% worked in mining, gas, and oil and barely 2% in agriculture, forestry, and fishing.

Architect Norma Sklarek reviewing plans, ca. 1979. Photograph by Jasmin Photo.

Photograph of flight attendant Casey Grant working mid-flight on a 757, 1985–1987.

Bob Johnson, President and founder Black Entertainment Television, in his Georgetown office in the early days of B.E.T evolution , June 5, 1981. Photograph by Milton Williams.

We still have much to learn about the world of work that African Americans have faced over the past four centuries and how it has changed. Until the 20th century, agriculture occupied over 90% of Black workers and now it occupies less than 1%. The causes are many: civil rights activism, affirmative action policies, educational opportunities, entrepreneurial energy, international competition, and the shift from industrial to digital and finance capitalism.

As these photos demonstrate, it is too easy to simply apply labels: “agricultural worker,” “domestic worker,” “skilled tradesman,” “unskilled labor,” “professional,” “union worker.” African Americans are and have been an integral part of the American workforce for centuries.

VIEW PHOTOGRAPHS OF AFRICAN AMERICANS AT WORK

Written by Bill Pretzer, Senior Curator of History; Amira Dehmani, Summer 2023 Stanford in Government Afrofuturism Curatorial Intern; and Douglas Remley, Rights & Publications Manager. Published on September 1, 2023

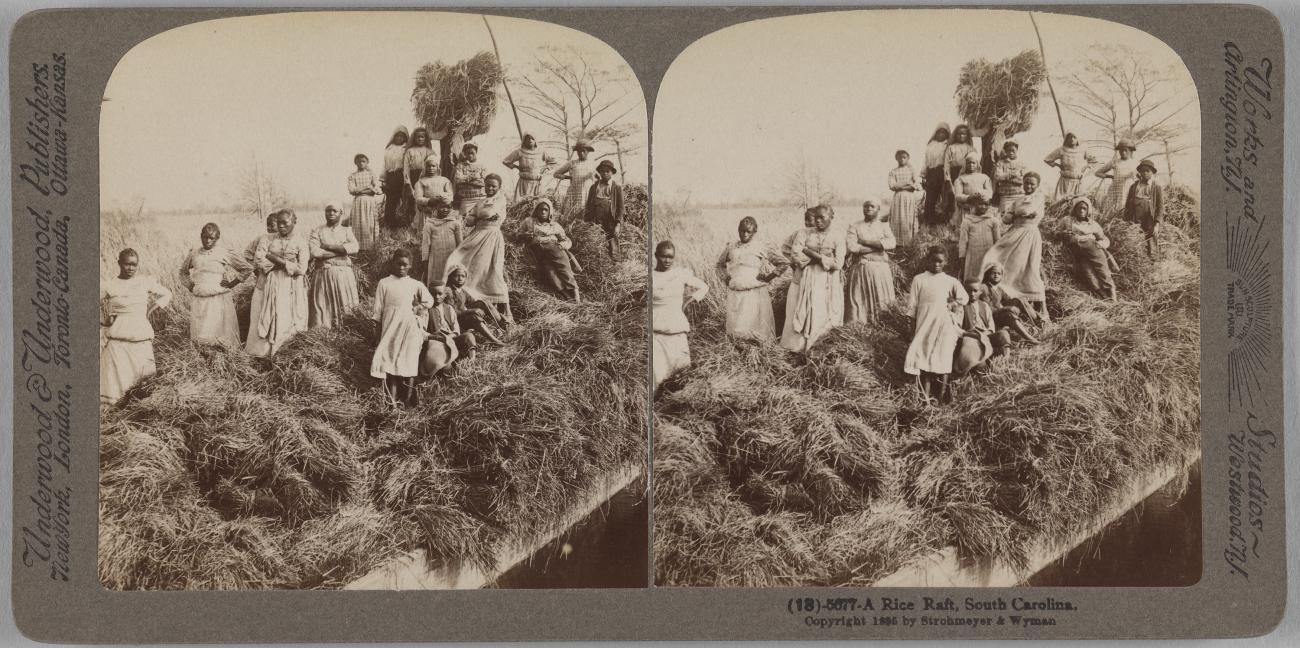

A Rice Raft, South Carolina

A Rice Raft, South Carolina , captured 1895; printed 1904. Photograph by Strohmeyer & Wyman. Published by Underwood & Underwood.

A woman with plow and oxen, Alabama

A woman with plow and oxen, Alabama, ca. 1875. Photograph by Russell Bros.

A Black nurse with two white children

A Black nurse with two white children, mid- to late 19th century.

Picking Strawberries, Plant City, Florida

PICKING STRAWBERRIES, PLANT CITY, FLA. , 1946.

Weighing cotton, Thomasville, Georgia

No. 44, Weighing Cotton , ca. 1895. From the series Views of Thomasville and Vicinity . Photograph by A. W. Möller.

A store clerk with a customer, Harlem, New York

A store clerk with a customer, Harlem, New York. Photograph by Lloyd W. Yearwood.

Councilwoman Hilda Mason in her office, Washington, D. C.

Washington D. C. Councilwoman at Large Hilda Mason of the D. C. Statehood Party in her office in the District Building , July 25, 1983. Photograph by Milton Williams.

Men outside the United Steelworkers of America, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Men outside the United Steelworkers of America, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, August 1946. Photograph by Charles "Teenie" Harris.

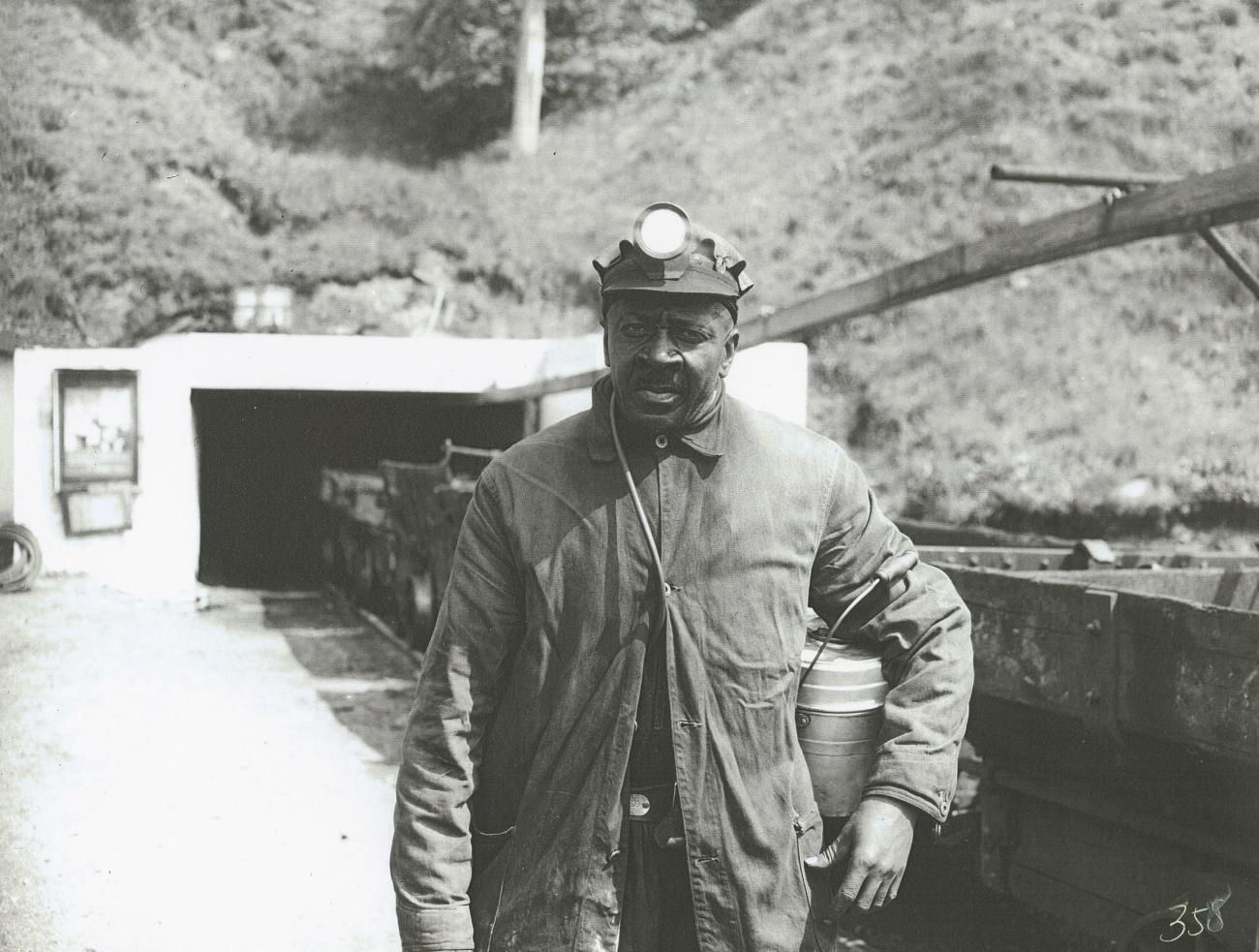

A coal miner, Library, Pennsylvania

A coal miner, Library, Pennsylvania, ca. 1947. Photograph by Charles "Teenie" Harris.

Two young men in wood shop, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Two young men in wood shop, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1930–1950. Photograph by Charles "Teenie" Harris.

A construction worker, Washington, D.C.

Construction Flag Person , 1978. Photograph by Milton Williams.

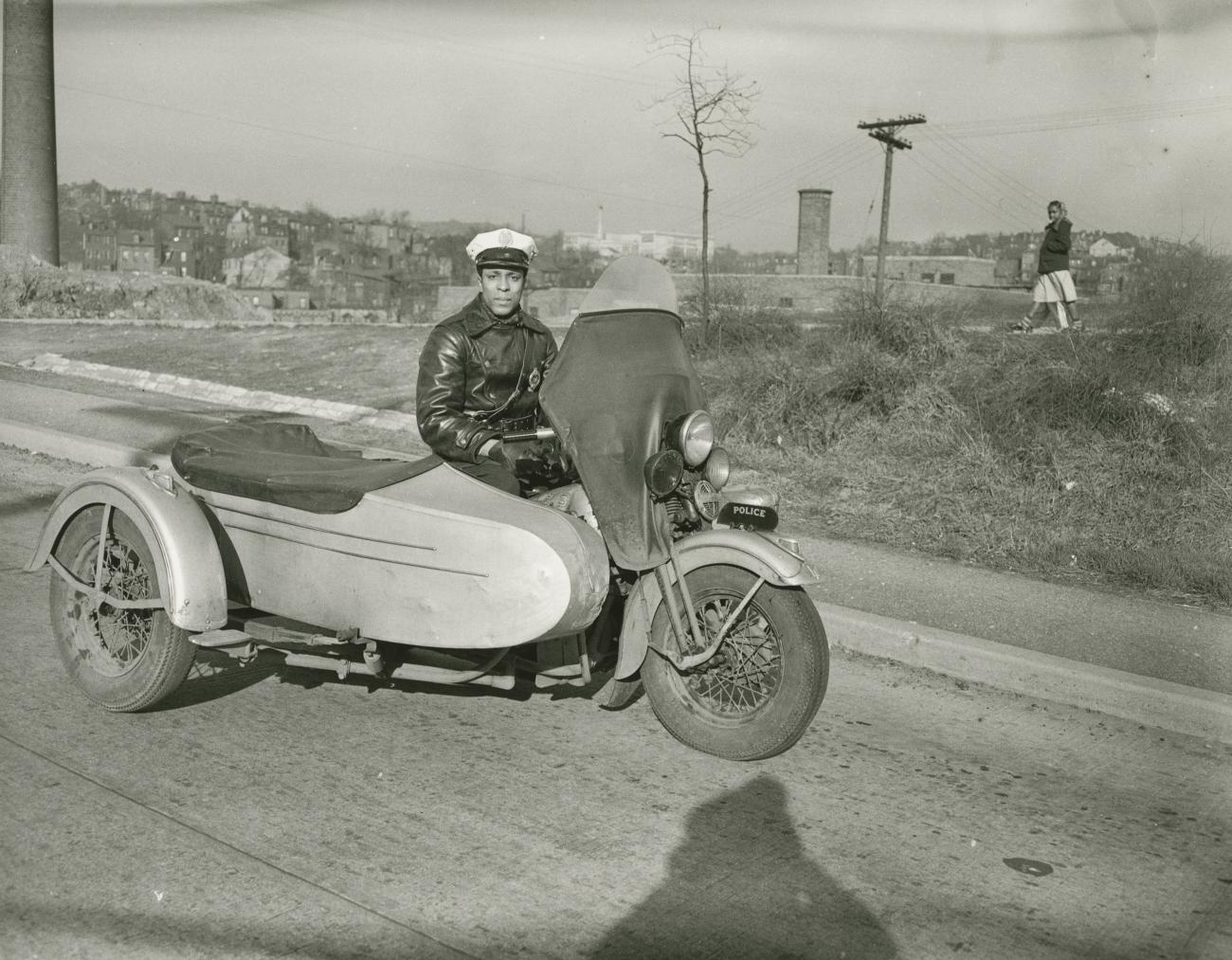

A policeman, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

A policeman in a motorcycle with a sidecar, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, mid-20th century. Photograph by Charles "Teenie" Harris.

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray, Arlington, Virginia

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray Esq. (1910-1985), civil rights lawyer and Episcopal priest was an activist who fought to dismantle segregation and end discrimination through the courts and on the streets , December 21, 1977. Photograph by Milton Williams.

Shrimpers on boat, Hilton Head Island, South Carolina

Shrimpers Eugene Orage and Diogenese Miller on boat, Hilton Head Island, SC , 2004. From the series Shadows of the Gullah Geechee . Photograph by Pete Marovich.

A construction worker, Harlem, New York

A construction worker operating a front end loader, Harlem, New York, 1987. Photograph by Lloyd W. Yearwood.

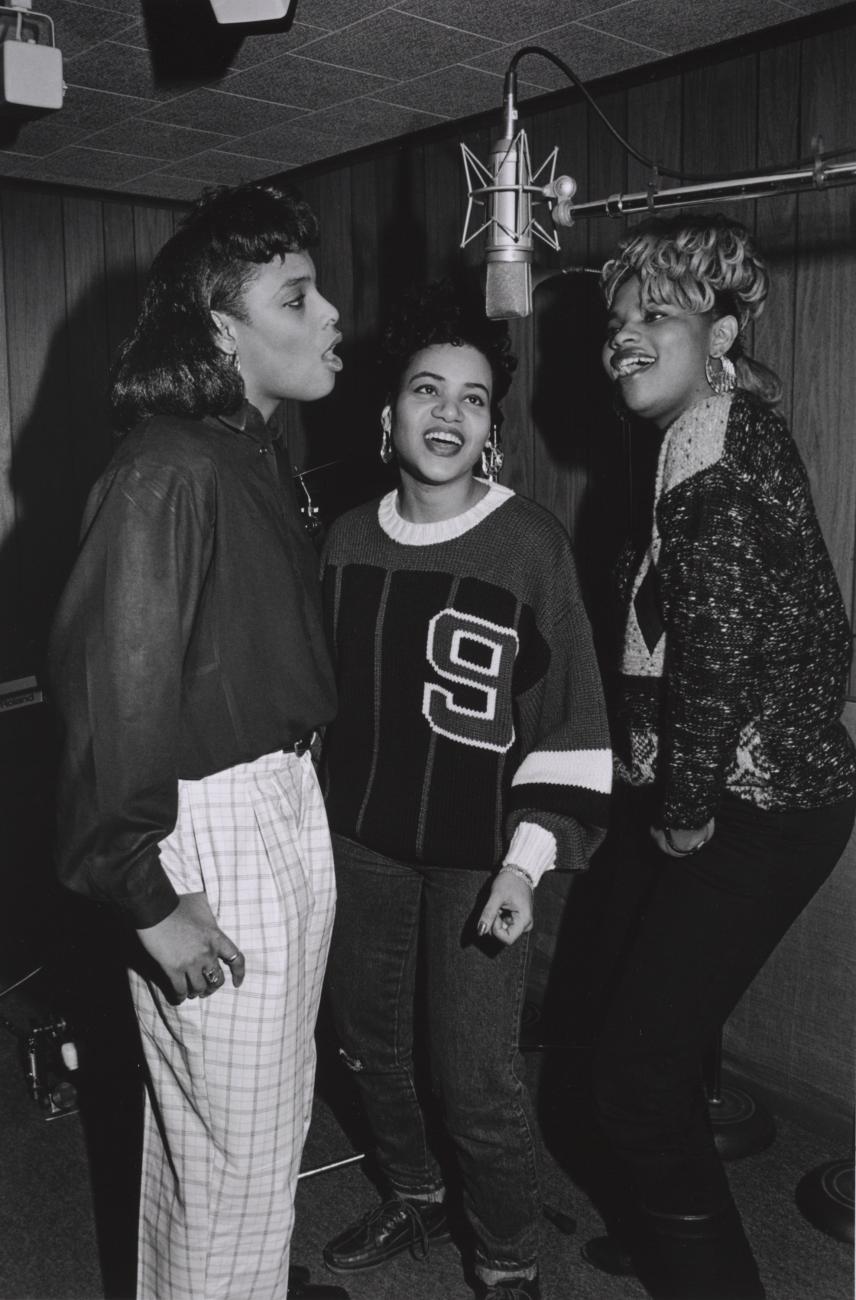

Salt-N-Pepa recording at Bayside Studios, Queens, New York

Salt-N-Pepa recording at Bayside Studios, February 6, 1989. Photograph by Al Pereira.

A porter from the Hotel Palomares, Pamona, California

A porter from the Hotel Palomares, Pamona, California, 1885–1899.

Gallery Modal

Subtitle here for the credits modal..

Photos From the Civil Rights Movement

From rosa park's arrest to the freedom rides, high museum of art.

I Am a Man/ Union Justice Now, Martin Luther King Memorial March for Union Justice and to End Racism, Memphis, Tennessee (1968/1968) by Builder Levy High Museum of Art

The High Museum of Art holds one of the most significant collections of photographs of the Civil Rights Movement. The works in this exhibition are only a small selection of the collection, which includes more than 300 photographs that document the social protest movement, from Rosa Parks’s arrest to the Freedom Rides to the tumultuous demonstrations of the late 1960s. The city of Atlanta—the birthplace of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—was a hub of civil rights activism and it figures prominently in the collection. Visionary leaders such as Dr. King, Congressman John Lewis, and former mayor Ambassador Andrew Young are featured alongside countless unsung heroes. The photographs in this collection capture the courage and perseverance of individuals who challenged the status quo, armed only with the philosophy of nonviolence and the strength of their convictions.

Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama (1956/1956) by Gordon Parks High Museum of Art

This photograph was originally published in a groundbreaking Life Magazine photo essay by Gordon Parks, which exposed Americans to the effects of racial segregation. Parks focused his attention on a multigenerational family from Alabama. His photographs captured the Thornton family’s everyday struggles to overcome discrimination.

Department Store, Mobile, Alabama (1956/1956) by Gordon Parks High Museum of Art

Gordon Parks's choice of subject matter sets his series of photographs of a family living under segregation in 1956 Alabama apart from others of the period. Rather than focusing on the demonstrations, boycotts, and brutality that characterized the battle for racial justice, Parks emphasized the prosaic details of one family’s life. His ability to elicit empathy through an emphasis on intimacy and shared human experience made them especially poignant.

Rosa Parks Being Fingerprinted, Montgomery, Alabama (1956/1956) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

This photograph was made at the time of Rosa Parks’s second arrest, and was widely reproduced in newspapers and magazines. Civil rights leaders quickly understood the power of photography to help stimulate awareness of their cause and raise funds for their effort to overthrow segregation laws.

Elizabeth Eckford Entering Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas (1957-09-05) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

One of the most iconic images of the civil rights era, this photograph shows 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford walking alone in front of Little Rock High School while being taunted by a menacing, hateful mob. Eckford was alone because she failed to receive notification that the date for desegregating the school had been postponed by a day.

National Guardsman, Montgomery Bus Station, Alabama (1961/1961) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

Members of SNCC Praying at Burned-out Church, Dawson, Georgia (1962/1962) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

March on Washington, D.C. (1963/1963) by Builder Levy High Museum of Art

Builder Levy frequently focuses on social issues, reflecting his personal commitment to causes he has embraced during his thirty-five year tenure as a teacher of at-risk adolescents in a New York inner-city school. This image documents one of the many historic marches on Washington, D.C., that took place during the civil rights era.

Cleaning the Pool, St. Augustine, Florida (1964/1964) by James Kerlin High Museum of Art

The man seen here pouring cleaning agents into a swimming pool occupied by men and women engaging in a “swim-in”, is James Brock, manager of the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida. Like most other white business owners, he banned blacks from his establishment. While the protestors floated in a pool of chemicals, off-duty policemen dove in and arrested them.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Ralph Abernathy, John's County Jail, St. Augustine, FL, 1964 (1964/1964) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

Dr. King and his fellow Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) leader Ralph Abernathy led a ten-person contingent to the Monson Motor Lodge in St. Augustine, Florida, in June 1964. King engaged the owner, James Brock, in a discussion that grew long and heated. King explained the kinds of humiliations blacks endured daily, to which Brock replied – smiling into the television cameras – “I would like to invite my many friends throughout the country to come to Monson’s. We expect to remain segregated.” The police arrived to arrest King and his group. They were held without bail in St. John’s County jail for several days.

Firemen Hosing Demonstrators, Kelly Ingram Park, Birmingham, Alabama (1963/1963) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

CORE Demonstration, Brooklyn, New York (1963/1963) by Leonard Freed High Museum of Art

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Baltimore (1964/1964) by Leonard Freed High Museum of Art

In October 1964, King learned that he had won the Nobel Peace Prize. At thirty-five he was the youngest ever recipient. On his way back from Oslo, Norway, to receive his prize he stopped off in Baltimore, where he was thronged by supporters offering congratulations on this landmark honor.

State Troopers Break Up Marchers, Selma, Alabama (1965/1965) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

Civil Rights Demonstrators and Ku Klux Klan Members Share the Same Sidewalk, Atlanta (1964/1964) by Unknown Photographer High Museum of Art

The Ku Klux Klan was picketing a newly desegregated hotel a few doors down from a segregated restaurant where a group of young civil rights workers were protesting. The lettering on a sign held by one of the young demonstrators, bearing the slogan “Atlanta’s Image is a Fraud”, has been enhanced by newsroom staff, presumably to read more effectively in newspaper print. Reflected in reverse in the storefront window behind the protestors is the signage for a Cary Grant movie being screened in a theater across the street.

Coretta King and Family around the Open Casket at the Funeral of Martin Luther King Jr., Atlanta (1968/1968) by Constantine Manos High Museum of Art

Coretta Scott King, Poor People's Campaign, Washington, D.C. (1968/1968) by Larry Fink High Museum of Art

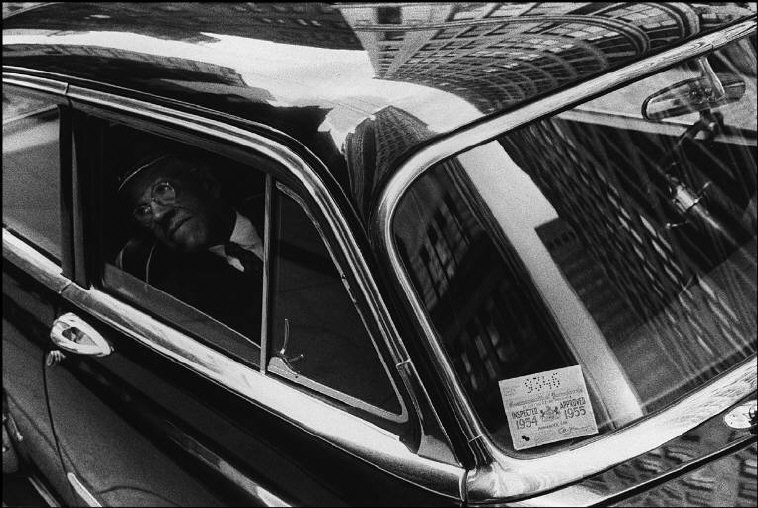

Larry Fink, best known for his portraits of high society reproduced in magazines such as Vanity Fair, was also very engaged with the civil rights cause. He was on hand in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 1968 – a month after Dr. King’s assassination - to photograph Coretta Scott King’s arrival at Resurrection City. Fink skillfully framed Mrs. King’s face in the doorjamb of the car, as she is greeted by Fred Bennette, a member of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

Garbagemen's Parade, Memphis, Tennessee (1968/1968) by Dennis Brack High Museum of Art

The tenacity and courage of members of the Civil Rights Movement - including those on both sides of the camera - continues to inspire social justice activists today. With protests and cries for equality happening across the United States, images like this one resonate more than ever.

Incredible, Innovative, and Unexpected Contemporay Furniture Designs

Bill traylor's drawings of people, animals, and events, 6 atlanta-based artists who explore place, belonging, and heritage, how iris van herpen transformed fashion, 13 contemporary artworks by atlanta-based artists.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Africa and Diaspora Studies

- African American Studies

- Arts and Leisure

- Business and Labor

- Education and Academia

- Government and Politics

- Religion and Spirituality

- Science and Medicine

- Agriculture

- Archives, Collections, and Libraries

- Art and Architecture

- Business and Industry

- Exploration, Pioneering, and Native Peoples

- Health and Medicine

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Law and Criminology

- Military and Intelligence Operations

- Miscellaneous Occupations and Realms of Renown

- Performing Arts

- Science and Technology

- Society and Social Change

- Sports and Games

- Writing and Publishing

- Before 1400: The Ancient and Medieval Worlds

- 1400–1774: The Age of Exploration and the Colonial Era

- 1775–1800: The American Revolution and Early Republic

- 1801–1860: The Antebellum Era and Slave Economy

- 1861–1865: The Civil War

- 1866–1876: Reconstruction

- 1877–1928: The Age of Segregation and the Progressive Era

- 1929–1940: The Great Depression and the New Deal

- 1941–1954: WWII and Postwar Desegregation

- 1955–1971: Civil Rights Era

- 1972–present: The Contemporary World

Photo Essay - The 1963 March on Washington

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

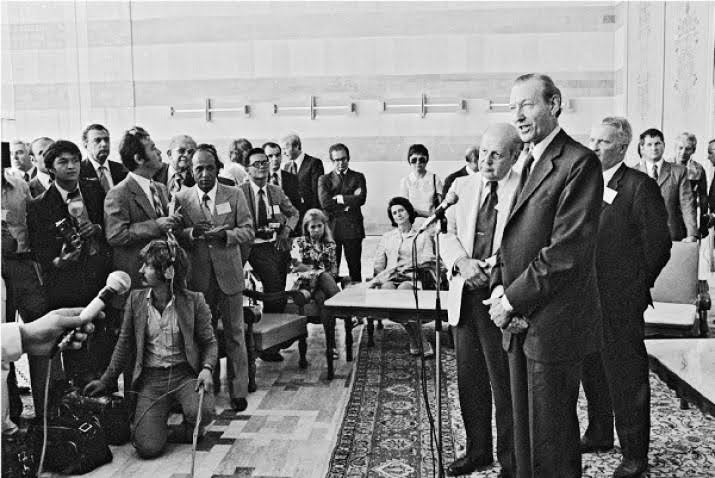

Organized by such leading lights of the American civil rights movement as Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, and A. Philip Randolph, the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom drew some quarter of a million demonstrators to the nation's capital. A landmark event among landmark events in an era of fundamental cultural and social change, the March on Washington brought the civil rights movement to a wider public consciousness and helped bring about the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Though perhaps less immediately recognizable than his more visible peers in the movement, it was Bayard Rustin (1912–1987) who was perhaps most directly responsible for organizing the massive 1963 demonstration. He's seen here in a photograph by Warren K. Leffler at a press conference concerning the March at the Statler Hotel on 27 August 1963.

This image of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was captured immediately before he delivered his classic, transformative "I Have a Dream" speech in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial on 28 August 1963.

The Calypso singer, musician, actor, and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte (b. 1927) has a long history of involvement with the American civil rights movement, including helping to fund the Freedom Rides. This photograph was taken on 28 August 1963.

James Baldwin (1924–1987), author of Go Tell It on the Mountain , poses for a photograph with the movie star Marlon Brando (1924–2004). Brando financially supported the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), and Baldwin returned from his self-imposed exile in Paris to take part in the struggle for civil rights in his native country.

Political scientist, author, and the first African American winner of the Nobel Peace Prize (1950), Dr. Ralph Johnson Bunche (1904–1971) lived a life dedicated to the principles of nonviolence and an untrammeled hope in the capacity of human beings to peacefully coexist.

Many notable entertainers performed for the crowd on the Washington Mall, among them the folk musicians Joan Baez (b. 1941) and Bob Dylan (b. 1941). For many young people of the 1960s Baez's and Dylan's music was the soundtrack of the movement.

Among his many contributions to the American civil rights movement, A. Philip Randolph (1889–1979) founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, widely considered the first African American labor union in the United States.

When Jackie Robinson (1919–1972) broke Major League baseball's color line in 1947 he forever changed the landscape of American professional sports and popular culture. He appears in this image with his son.

The multitalented Ossie Davis (1917–2005), actor, writer, and director, struggled throughout his long and dignified career to force Hollywood to change its view of African American actors and to offer them roles outside the stereotypes that had trapped earlier performers.

A member of the so-called Rat Pack with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, and others, Sammy Davis Jr. (1925–1990) helped to integrate once-segregated nightspots by refusing to perform in them.

Actress and singer, the great Lena Horne (b. 1917) spent much of her film career on the cutting-room floor, at least in the American South. Since southern theaters often refused to show scenes featuring African American performers, many of their scenes or numbers were simply edited out.

Gordon Parks' (1912-2006) photographs graced the covers of Life magazine for nearly two decades and included images of some of the civil rights movement's most important figures. Among the first mainstream African American motion picture directors, as well, Parks helmed such movies as The Learning Tree (1969) and Shaft (1971).

To those who are only familiar with the film actor Charlton Heston's (b. 1923) late political persona, in particular his role as president of the National Rifle Association and liberal bete noi , it may come as something of a surprise that in his younger days he was a strong advocate of gun control, an enemy of segregation, and an outspoken and passionate champion of civil rights for African Americans.

President John F. Kennedy (1917–1963) came slowly to the idea of advancing civil rights through mass public demonstration, fearing the reaction of southern politicians and the effect on his own political fortunes. In this image by Cecil Stoughton, the president meets with the leaders of the 1963 March.

PRINTED FROM OXFORD AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES CENTER (www.oxfordaasc.com). © Oxford University Press, 2022. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in Oxford Medicine Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 01 August 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

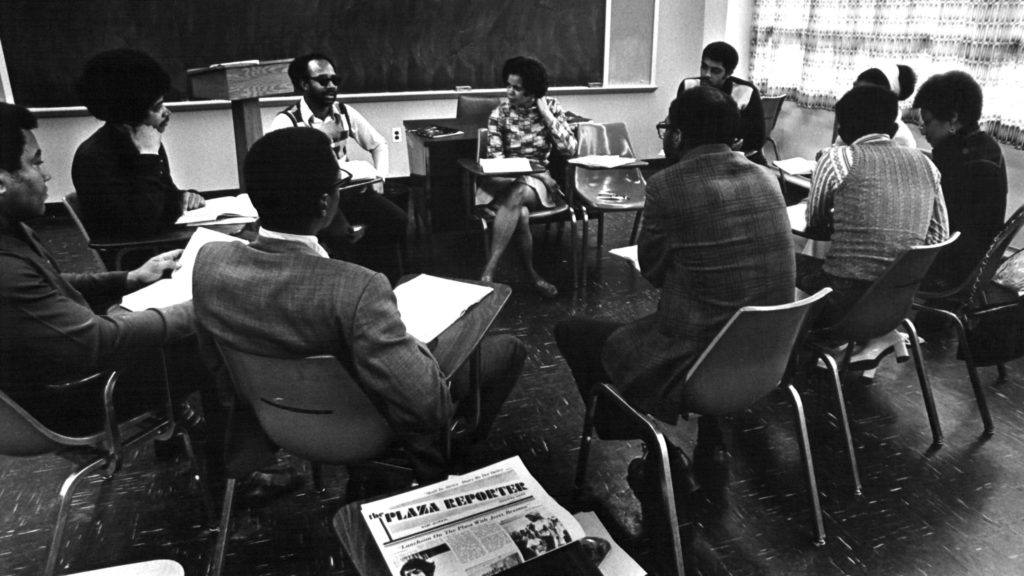

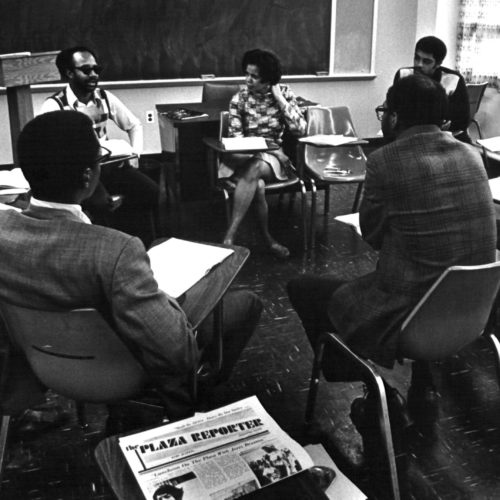

Photo Essay: Supporting Minority Enterprise in the late 1960s

In 1968, the ford foundation began to fund minority enterprise and other social investments using a new tool, the program-related investment ( pri ). the breadth of activities that pris funded extended to both inner city and rural environments..

Civil rights leader Rev. Leon Sullivan spearheaded the creation of the Progress Plaza shopping center in Philadelphia — the first minority-owned and developed shopping center in the US.

Local residents contributed the start-up capital for Progress Plaza via Sullivan’s Zion Non-Profit Charitable Trust. Ford Foundation PRI funds gave the project a final boost.

Progress Plaza included the neighborhood’s first grocery store, a much-needed addition to this area, which had been overlooked by white investors and developers.

Ford PRI funds supported the construction of a commercial center in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York.

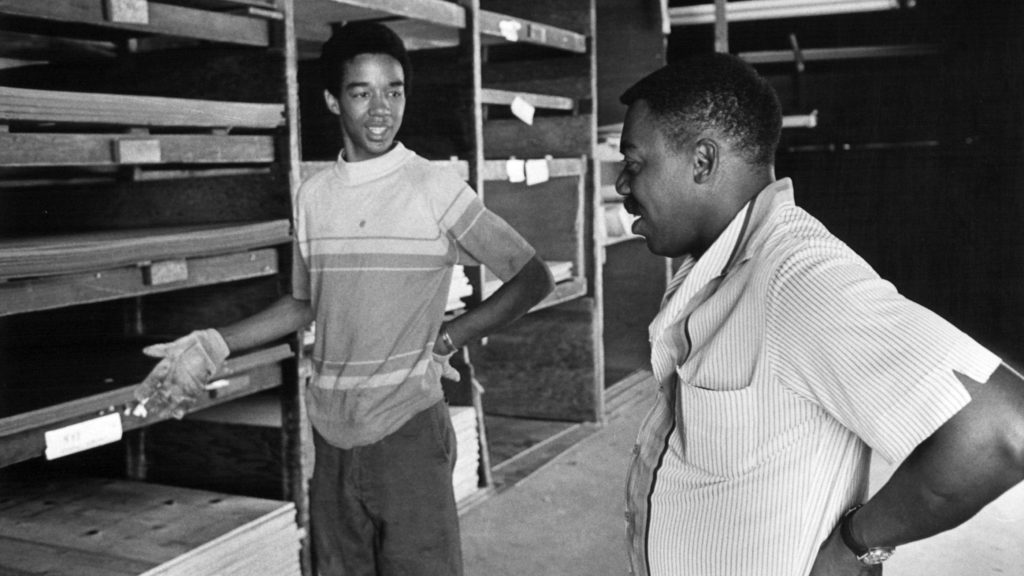

The Inner-City Business Improvement Forum financed this minority-owned lumber yard in Detroit. The Forum received $500,000 in PRI funds from Ford to create a loan pool for minority businesses.

San Francisco Gold Co. produced women’s apparel. Ford invested in the company with its PRI funds through an intermediary, the Urban National Corp.

PRIs funded manufacturing businesses such as Hubbard and Co., a hardware producer in Emeryville, California

Trans-Bay Engineers and Builders, an association of minority contractors, built this commercial building in Oakland, California with help from PRI funding.

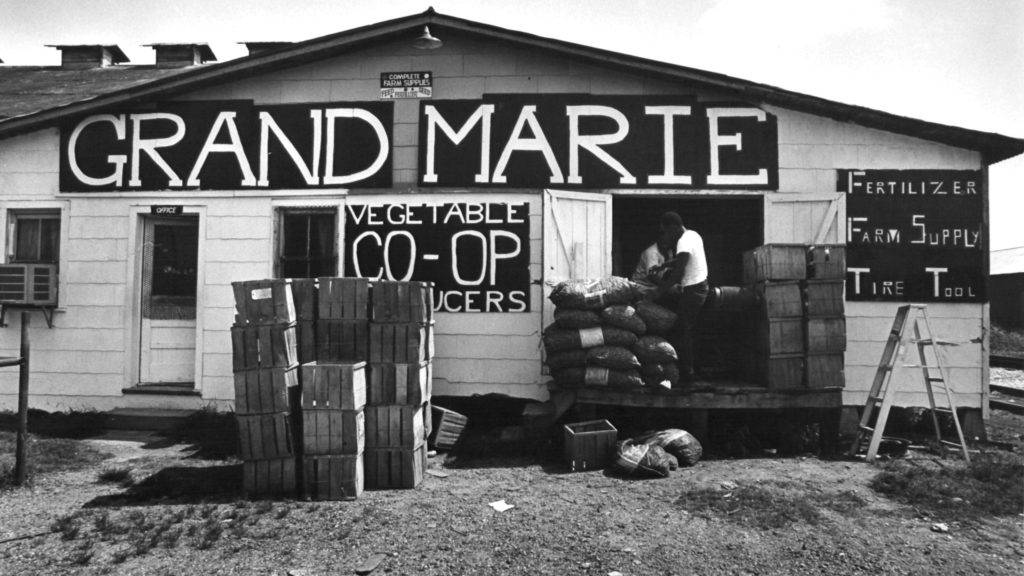

PRIs were not limited to urban initiatives. A $400,000 Ford investment in the Southern Cooperative Development Fund helped support minority-owned agricultural enterprises in the rural South.

The Grand Marie Vegetable Co-op in Lafayette, Louisiana received financial and technical support from the Southern Cooperative Development Fund.

Supporting Economic Justice? The Ford Foundation’s 1968 Experiment in Program Related Investments

How the largest US foundation began supporting market-based projects in the late 1960s.

In the fall of 2020, the Rockefeller Archive Center launched a new oral history and research project called I nvesting in the Good: Program-Related Investments and the Birth of Impact Investing . Directed by Dr. Rachel Wimpee, the assistant director of Research & Education at the Archive Center, the oral history project will include interviews with pioneers in the field. The book, coauthored by Wimpee, Eric John Abrahamson, and Alec Appelbaum will be developed as a resource for professionals and students in the fields of philanthropy, nonprofit management, and public policy.

- Civil Rights Movement

- Economic Inequality

- Financial Sustainability

- Ford Foundation

- Philanthropic Strategies

- Philanthropy & the Private Sector

- Self-Sustaining Initiatives

- United States

Explore Further

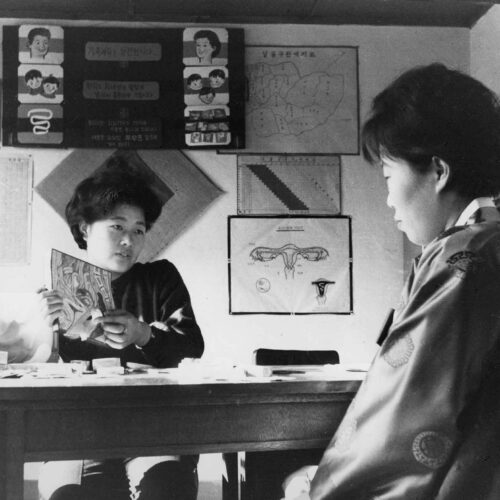

“A very small number of men control all the money and the ideas”: Women Revolutionize Population Programs in the 1970s

Women and technocratic elites clashed at the 1974 World Population Conference. At stake was women’s control over their own bodies.

New Research: Neuroscience Funding, Colorado Coal Strike, Population Control Debate, and the Politics of Crime

The reports featured in this installment draw on several personal papers as well as the archival collections of the Commonwealth Fund, the Population Council, the Rockefeller Foundation, and others.

New Research: Bat Echolocation, Women’s Reproductive Rights, Tropical Medicine, and Blanchette Rockefeller

In our New Research series, we highlight recently published reports written by researchers who have received RAC travel stipends to pursue their studies in our archival collections. In this edition of the series, the authors have studied materials in a number of collections of personal papers. They include the papers of Donald R. Griffin, Joan…

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Photography in postwar america, 1945-60.

Le Tricorne

Alexey Brodovitch

Fort Peck Dam, Montana

Margaret Bourke-White

Feet, Wall Street

Lisette Model

New York, N.Y.

Louis Faurer

Irving Penn

William Klein

Rodeo, New York City

Robert Frank

Marian Anderson, contralto, New York

Richard Avedon

Lisa Hostetler Department of Photographs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

“A photograph is not merely a substitute for a glance. It is a sharpened vision. It is the revelation of new and important facts.” This sentiment, expressed by the Photo League photographer Sid Grossman ( 1990.1139.1 ), encapsulates photography’s role in America in the 1940s and ’50s. The era saw the apotheosis of photojournalism and few photographers were unaffected by its rise, whether they joined the bandwagon or reacted against it.

Ushering the age of the image into American culture was Margaret Bourke-White’s Fort Peck Dam, Montana ( 1987.1100.25 ), which appeared on the cover of the first issue of Life magazine in November 1936. For the next three decades, magazines ( Life foremost among them) told the world’s news stories through pictures. World War II was the first major widespread conflict covered extensively by photojournalists, who earned reputations as heroes for risking their lives to visualize the events. W. Eugene Smith was perhaps the most famous postwar photographer to earn his stripes on the battlefield, and, after the war, his photo essays—a form that he perfected in stories such as “Country Doctor” (1948), “Spanish Village” (1951), and “A Man of Mercy” (on Albert Schweitzer, 1954)—were as unrelenting as his war photographs, making the viewer experience the world as the subjects did and demanding a sympathetic response. Smith’s work created this effect both through individual pictures, and by sequencing the photographs in order to create a sense of narrative through mood. His insistence on producing his own layouts made for a tempestuous relationship with the publications for whom he worked, however, and he joined the Magnum photo collective in 1955 in order to work more freely.