- Department of Economic and Social Affairs Social Inclusion

- Meet our Director

- Milestones for Inclusive Social Development.

- Second World Summit For Social Development 2025

- World Summit For Social Development 1995

- 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

- Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

- UN Common Agenda

- International Days

- International Years

- Social Media

- Second World Summit 2025

- World Summit 1995

- Social Development Issues

- Cooperatives

- Digital Inclusion

- Employment & Decent Work

- Indigenous Peoples

- Poverty Eradication

- Social Inclusion

- Social Protection

- Sport for Development & Peace

- Commission for Social Development (CSocD)

- Conference of States Parties to the CRPD (COSP)

- General Assembly Second Committee

- General Assembly Third Committee

- Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Ageing

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII)

- Publications

- World Social Report

- World Youth Report

- UN Flagship Report On Disability And Development

- State Of The World’s Indigenous Peoples

- Policy Briefs

- General Assembly Reports and Resolutions

- ECOSOC Reports and Resolutions

- UNPFII Recommendations Database

- Capacity Development

- Civil Society

- Expert Group Meetings

The impact of COVID-19 on sport, physical activity and well-being and its effects on social development

Introduction

Sport is a major contributor to economic and social development. Its role is well recognized by Governments, including in the Political Declaration of the 2030 Agenda, which reflects on “the contribution sports make to the empowerment of women and of young people, individuals and communities, as well as to health, education and social inclusion objectives.”

Since its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread to almost all countries of the world. Social and physical distancing measures, lockdowns of businesses, schools and overall social life, which have become commonplace to curtail the spread of the disease, have also disrupted many regular aspects of life, including sport and physical activity. This policy brief highlights the challenges COVID-19 has posed to both the sporting world and to physical activity and well-being, including for marginalized or vulnerable groups. It further provides recommendations for Governments and other stakeholders, as well as for the UN system, to support the safe reopening of sporting events, as well as to support physical activity during the pandemic and beyond.

The impact of COVID-19 on sporting events and the implications for social development

To safeguard the health of athletes and others involved, most major sporting events at international, regional and national levels have been cancelled or postponed – from marathons to football tournaments, athletics championships to basketball games, handball to ice hockey, rugby, cricket, sailing, skiing, weightlifting to wrestling and more. The Olympics and Paralympics, for the first time in the history of the modern games, have been postponed, and will be held in 2021.

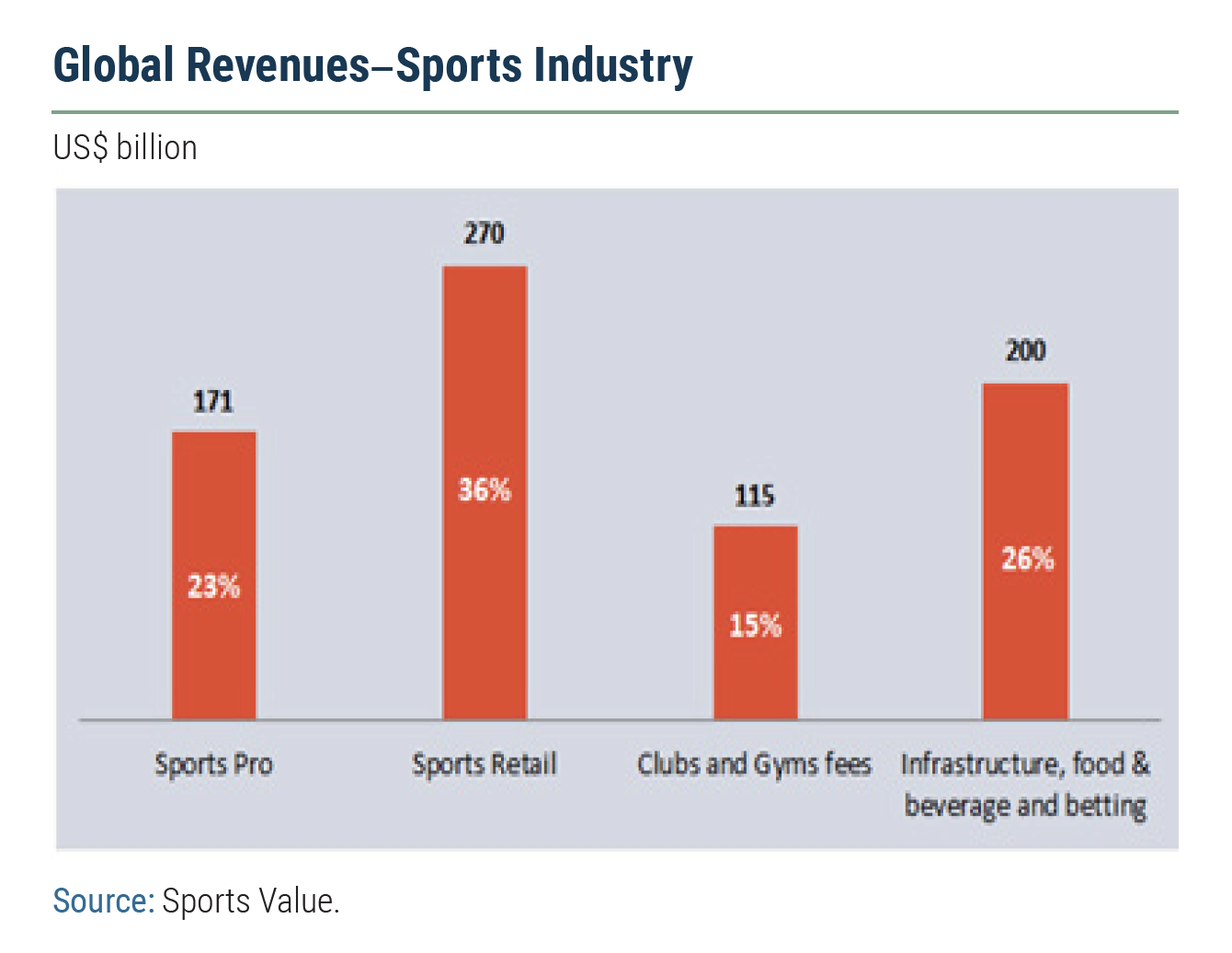

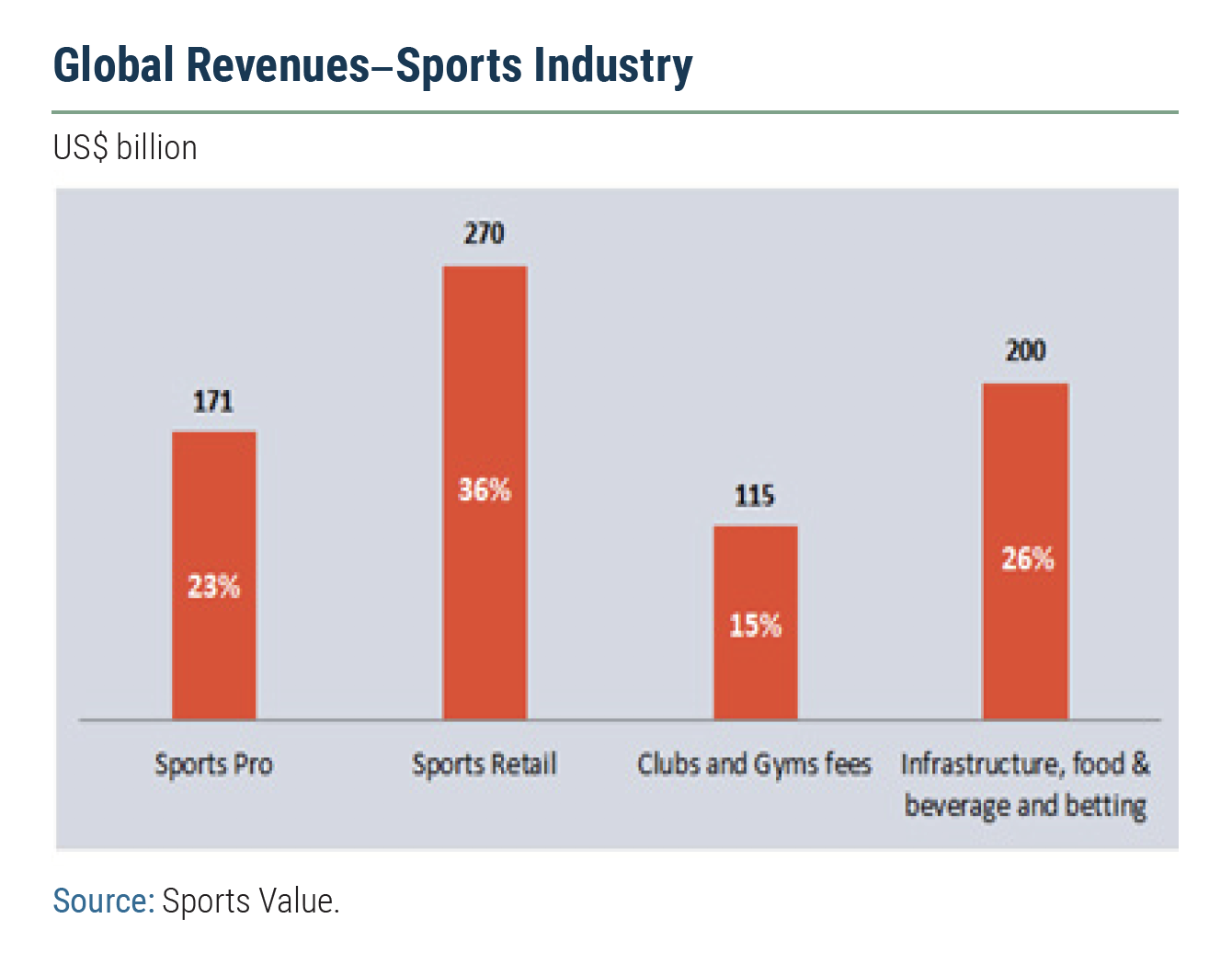

The global value of the sports industry is estimated at US$756 billion annually. In the face of COVID-19, many millions of jobs are therefore at risk globally, not only for sports professionals but also for those in related retail and sporting services industries connected with leagues and events, which include travel, tourism, infrastructure, transportation, catering and media broadcasting, among others. Professional athletes are also under pressure to reschedule their training, while trying to stay fit at home, and they risk losing professional sponsors who may not support them as initially agreed.

Major sporting organisations have shown their solidarity with efforts to reduce the spread of the virus. For example, FIFA has teamed up with the World Health Organisation (WHO) and launched a ‘Pass the message to kick out coronavirus’ campaign led by well-known football players in 13 languages, calling on people to follow five key steps to stop the spread of the disease focused on hand washing, coughing etiquette, not touching one’s face, physical distance and staying home if feeling unwell. Other international sport for development and peace organizations have come together to support one another in solidarity during this time, for example, through periodic online community discussions to share challenges and issues. Participants in such online dialogues have also sought to devise innovative solutions to larger social issues, for example, by identifying ways that sporting organisations can respond to problems faced by vulnerable people who normally participate in sporting programmes in low income communities but who are now unable to, given restriction to movement.

The closure of education institutions around the world due to COVID-19 has also impacted the sports education sector, which is comprised of a broad range of stakeholders, including national ministries and local authorities, public and private education institutions, sports organizations and athletes, NGOs and the business community, teachers, scholars and coaches, parents and, first and foremost, the – mostly young – learners. While this community has been severely impacted by the current crisis, it can also be a key contributor to solutions to contain and overcome it, as well as in promoting rights and values in times of social distancing.

As the world begins to recover from COVID-19, there will be significant issues to be addressed to ensure the safety of sporting events at all levels and the well-being of sporting organizations. In the short term, these will include the adaptation of events to ensure the safety of athletes, fans and vendors, among others. In the medium term, in the face of an anticipated global recession, there may also be a need to take measures to support participation in sporting organizations, particularly for youth sports.

The impact of COVID-19 on physical activity and well-being

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has resulted in closure of gyms, stadiums, pools, dance and fitness studios, physiotherapy centres, parks and playgrounds. Many individuals are therefore not able to actively participate in their regular individual or group sporting or physical activities outside of their homes. Under such conditions, many tend to be less physically active, have longer screen time, irregular sleep patterns as well as worse diets, resulting in weight gain and loss of physical fitness. Low-income families are especially vulnerable to negative effects of stay at home rules as they tend to have sub-standard accommodations and more confined spaces, making it difficult to engage in physical exercise.

The WHO recommends 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity per week. The benefits of such periodic exercise are proven very helpful, especially in times of anxiety, crisis and fear. There are concerns therefore that, in the context of the pandemic, lack of access to regular sporting or exercise routines may result in challenges to the immune system, physical health, including by leading to the commencement of or exacerbating existing diseases that have their roots in a sedentary lifestyle.

Lack of access to exercise and physical activity can also have mental health impacts, which can compound stress or anxiety that many will experience in the face of isolation from normal social life. Possible loss of family or friends from the virus and impact of the virus on one’s economic wellbeing and access to nutrition will exacerbate these effects.

For many, exercising at home without any equipment and limited space can still be possible. For those whose home life can involve long periods of sitting, there may be options to be more active during the day, for example by stretching, doing housework, climbing stairs or dancing to music. In addition, particularly for those who have internet access, there are many free resources on how to stay active during the pandemic. Physical fitness games, for example, can be appealing to people of all ages and be used in small spaces. Another important aspect of maintain physical fitness is strength training which does not require large spaces but helps maintain muscle strength, which is especially important for older persons or persons with physical disabilities.

The global community has adapted rapidly by creating online content tailored to different people; from free tutorials on social media, to stretching, meditation, yoga and dance classes in which the whole family can participate. Educational institutions are providing online learning resources for students to follow at home.

Many fitness studios are offering reduced rate subscriptions to apps and online video and audio classes of varying lengths that change daily. There are countless live fitness demonstrations available on social media platforms. Many of these classes do not require special equipment and some feature everyday household objects instead of weights.

Such online offerings can serve to increase access to instructors or classes that would otherwise be inaccessible. However, access to such resources is far from universal, as not everyone has access to digital technologies. For individuals in poorer communities and in many developing countries, access to broadband Internet is often problematic or non-existent. The digital divide has thus not only an impact on distance banking, learning or communication, but also on benefitting from accessing virtual sport opportunities. Radio and television programmes that activate people as well as distribution of printed material that encourages physical activity are crucial in bridging the digital divide for many households living in precarious conditions. Young people are particularly affected by social and physical distancing, considering sport is commonly used as a tool to foster cooperation and sportsmanship, promote respectful competition, and learn to manage conflict. Without sport, many young people are losing the support system that such participation provided. Currently some organizations, and schools have begun using virtual training as a method for leagues, coaches and young people to remain engaged in sport activities while remaining in their homes.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The COVID-19 pandemic has had and will continue to have very considerable effects on the sporting world as well as on the physical and mental well-being of people around the world. The following recommendations seek to both support the safe re-opening of sporting events and tournaments following the pandemic, as well as to maximize the benefits that sport and physical activity can bring in the age of COVID-19 and beyond.

The impact of COVID-19 on sporting events

1. sporting federations and organizations..

Governments and intergovernmental organizations may provide sports federations, clubs and organizations around the world with guidance related to safety, health, labour and other international standards and protocols that would apply to future sport events and related safe working conditions. This would allow all stakeholders to work cooperatively as a team with the objective to address the current challenges and to facilitate future sports events that are safe and enjoyable for all.

2. Professional sport ecosystem.

The sport ecosystem, comprising of producers, broadcasters, fans, businesses, owners and players among others, need to find new and innovative solutions to mitigate the negative effects of COVID19 on the world of sport. This includes finding ways to engage with fans in order to ensure safe sport events in the future while maintaining the workforce, creating new operating models and venue strategies.

1. Supporting physical activity.

Governments should work collaboratively with health and care services, schools and civil society organizations representing various social groups to support physical activity at home. Enhancing access to online resources to facilitate sport activities where available should be a key goal in order to maintain social distancing. However, low-tech and no-tech solutions must also be sought for those who currently lack access to the internet. Creating a flexible but consistent daily routine including physical exercise every day to help with stress and restlessness is advisable.

2. Research and policy guidance.

The United Nations system, through its sports policy instruments and mechanisms such as the Intergovernmental Committee for Physical Education and Sport,7 as well as through its research and policy guidance should support Governments and other stakeholders to ensure effective recovery and reorientation of the sports sector and, at the same time, strengthen the use of sports to achieve sustainable development and peace. Scientific research and higher education will also be indispensable pillars to inform and orient future policies.

3. Technical cooperation and capacity development.

Governments, UN entities and other key stakeholders should ensure the provision of capacity development and technical cooperation services to support the development and implementation of national policies and approaches for the best use of sport to advance health and well-being, particularly in the age of COVID-19.

4. Outreach and awareness raising.

Governments, the United Nations and the sporting community, including the sporting education community, should disseminate WHO and other guidance on individual and collective measures to counter the pandemic. Measures must be taken to reach communities that have limited access to the Internet and social media and that can be reached through cascading the sport education pyramid from the national/ministerial level down to the provincial/municipal level, from the national physical education inspector down to the teacher, from the national sport federation down to the clubs. In turn, escalating the pyramid provides for important feedback to identify needs and share specific solutions. Athletes, while deeply affected by the pandemic, remain key influencers to ensure that – especially young – audiences understand risks and respect guidance.

5. Promoting positive social attitudes and behaviour.

Sport education is a powerful means to foster physical fitness, mental well-being, as well as social attitudes and behaviour while populations are locked down. International rights and values based sport education instruments and tools, such as the International Charter of Physical Education, Physical Activity and Sport, the Quality Physical Education Policy package and the Values Education through Sport toolkit remain highly relevant references to ensure that the many online physical activity modules that are being currently deployed comply with gender equality, non-discrimination, safety and quality standards.

Read the full UN DESA policy brief on “The impact of COVID-19 on sport, physical activity and well-being and its effects on social development”.

The UN DESA COVID-19 policy briefs can be found at bit.ly/UNDESACovid .

- Search Search

| Format | |

|---|---|

| BibTeX | View Download |

| MARCXML | View Download |

| TextMARC | View Download |

| MARC | View Download |

| DublinCore | View Download |

| EndNote | View Download |

| NLM | View Download |

| RefWorks | View Download |

| RIS | View Download |

Browse Subjects

- Sustainable Development Goals

Advertisement

Effects of the lockdown period on the mental health of elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review

- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2022

- Volume 18 , pages 1187–1199, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Vittoria Carnevale Pellino 1 , 2 ,

- Nicola Lovecchio 3 ,

- Mariangela V. Puci 4 ,

- Luca Marin 1 , 5 , 6 ,

- Alessandro Gatti 1 ,

- Agnese Pirazzi 1 ,

- Francesca Negri 1 ,

- Ottavia E. Ferraro 4 &

- Matteo Vandoni 1

5163 Accesses

13 Citations

Explore all metrics

This review aimed to assess the effects of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on mental health to elite athletes. The emotional background influenced their sport career and was examined by questionnaires.

We included original studies that investigated psychological outcomes in elite athletes during COVID-19 lockdown. Sixteen original studies ( n = 4475 participants) were analyzed.

The findings showed that COVID-19 has an impact on elite athletes’ mental health and was linked with stress, anxiety and psychological distress. The magnitude of the impact was associated with athletes’ mood state profile, personality and resilience capacity.

The lockdown period impacted also elite athletes’ mental health and training routines with augmented anxiety but with fewer consequences than the general population thanks to adequate emotion regulation and coping strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health in sports: a review

Depressive symptoms among Olympic athletes during the Covid-19 pandemic

The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The outbreak of SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19) and the ongoing pandemic caused a public health concern all over the world with health, social, and economic negative consequences [ 1 , 2 ]. To limit the spread of the virus, governments were forced to impose lockdown measures with the “stay at home” imperative. Everyday life changed all over the world: social-distancing, mask-wearing, limited travel, leisure activity, and non-essential activities stopped [ 3 ]. These restrictions affected the entire population promoting sedentary behavior and inactive lifestyle [ 4 , 5 ], which led to acute and long-term physical [ 6 ] and mental disorders, such as acute stress disorder, exhaustion, irritability, insomnia, poor concentration, indecisiveness, fear, and anxiety [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For these reasons, several researchers and studies implemented and provided specific recommendations for general population health [ 2 , 10 ] and fitness [ 11 ] to better cope COVID-19 period. The sports contest was not excluded from the protective measures against pandemic and, at every level, it was affected by an extraordinary period with the closure of training facilities, and the interdiction of training both for amateurs and elite athletes until all sports’ competitions postponement (e.g. Olympic Games) or cancelation [ 7 , 8 ]. Even if the priority remains the limitation of contagion, the imposed restrictions did not allow athletes to follow their training and competitive routines, because they were forced to train at home, on their own, and often with no trainers supervision. For this reason, specific suggestions have also been provided for elite and professional athletes [ 12 ] to maintain health, optimal body composition, specific routine exercise, physical conditioning, to encourage a safe return to training and competitions, and to avoid psychological distress (according to the American Psychology Association dictionary, “a set of painful mental and physical symptoms that are associated with normal fluctuations of mood in most people”) [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Previous studies showed that a long-term detraining, of at least eight weeks as a similar effect due to COVID-19 forced to stop, leads to a marked decline in maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max), endurance capacity, and muscle strength and power with a reduction of electromyography activity (EMG) that reflects reduced muscle activation [ 17 ]. All these declines in athletes’ physical condition have been shown to significantly increase the risk of injuries, fear of return to competition, and psychological distress [ 18 ]. Moreover, in this last period, many athletes have reported challenges and issues connected to social isolation, like career disruption or uncertainty of contract status, and ambiguity of the qualification process, which could be additional stressors and could increase psychological distress, affecting the training and the performance of the athletes [ 19 , 20 ]. Consequently, the awareness of stress and anxiety outcomes became relevant for sports specialists, coaches, and sports psychologists to help athletes to maintain focus, motivation, coping strategies and find, organize, and plan the best strategies for return to competition without fears.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, an elite athlete encountered a lot stressors during the career [ 21 ], the COVID-19 restrictions seems to have amplified all the stressors with negative consequences on the mental health of athletes. Unfortunately, the present literature does not seem to clarify the possible causes and effects of COVID-19 restrictions on athletes. So, the present narrative review aims to describe how the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown influenced the mental health of elite athletes. Specifically, the primary objective of this review is to identifies the common psychological distress and stress responses on elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, our research aims to identify factors, either positive or negative, related to psychological distress in elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Search strategy

The study was conducted up to 24th November 2021 through computerized research in the databases PubMed, Scopus, SportDiscus and Web-of-Science for papers published in English in peer-reviewed journals providing information related to mental health of athletes during COVID-19 lockdown.

The following search terms were used: (coronavirus OR COVID-19 OR lockdown OR isolation) AND (sport competition OR sport participation OR training) AND (elite athletes OR athletes OR collegiate athletes) AND (mental health OR psychological distress) AND (COVID-19 OR elite athlete OR mental health). Finally, the reference lists of the studies were manually checked to identify potentially eligible studies not found by the electronic searches. Two reviewers independently: (a) screened the title and abstract of each reference to determine potentially relevant studies, and copies of the screened documents were obtained; (b) subsequently, reviewed them in detail to identify articles that met the inclusion criteria. Third reviewer solved discrepancies between reviewers in the studies selection.

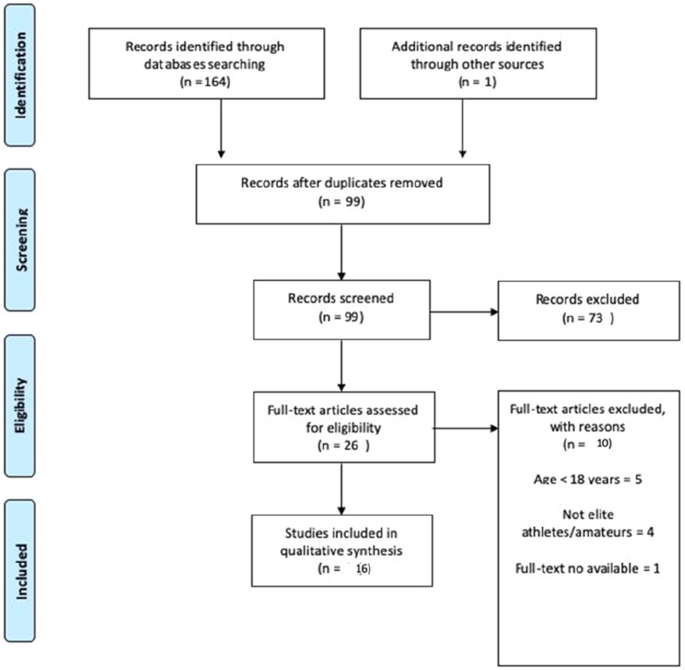

Study selection criteria

Research articles were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) studies with full-text available and had to investigated mental health in athletes with elite or professional or international/national status older than 18 years old pre and during COVID-19 pandemic; the elite status of the athletes was given to the athletes with at least 5-day per week training and participation into national and international sport-specific competitions; (2) studies had to specify the duration of lockdown period; (3) studies had to assess psychobiological factors through valid and reliable tools/questionnaires or showed full questions and scored. Finally, we excluded narrative reviews, abstracts, editorial or commentaries, letters to the editors and case reports and studies that investigated athletes under quarantine or ongoing COVID-19 infection. Flow chart of included studies is shown in Fig. 1 . All the main findings was synthetized through a narrative approach [ 22 ].

Study selection flow-chart

Descriptive and methodological characteristics of the studies

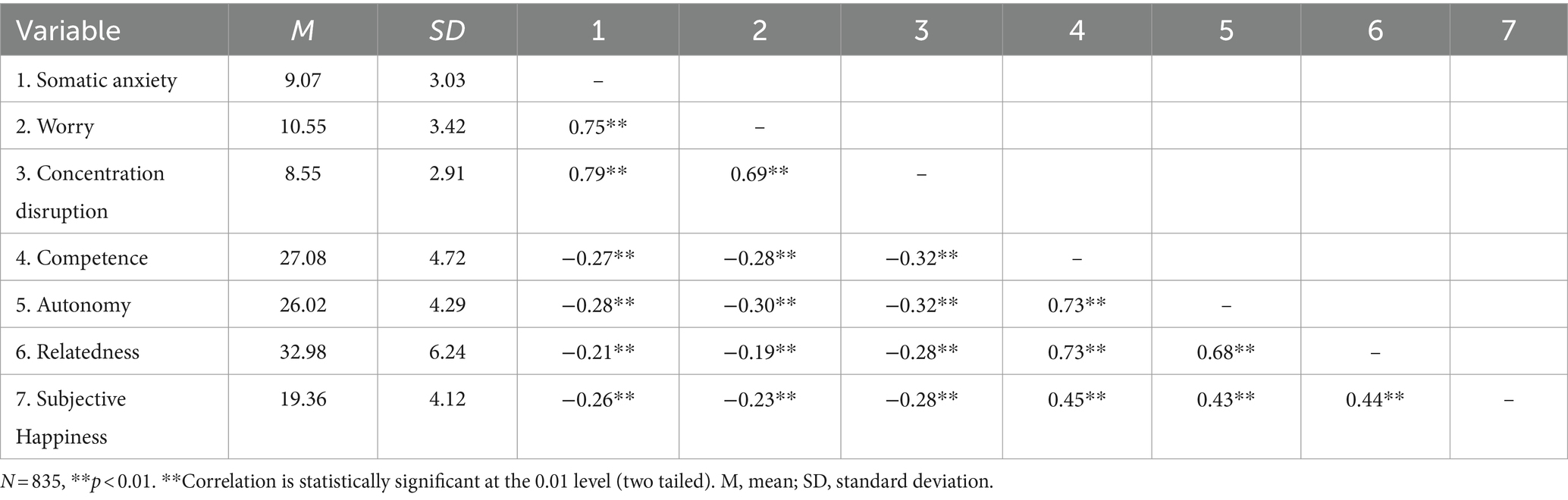

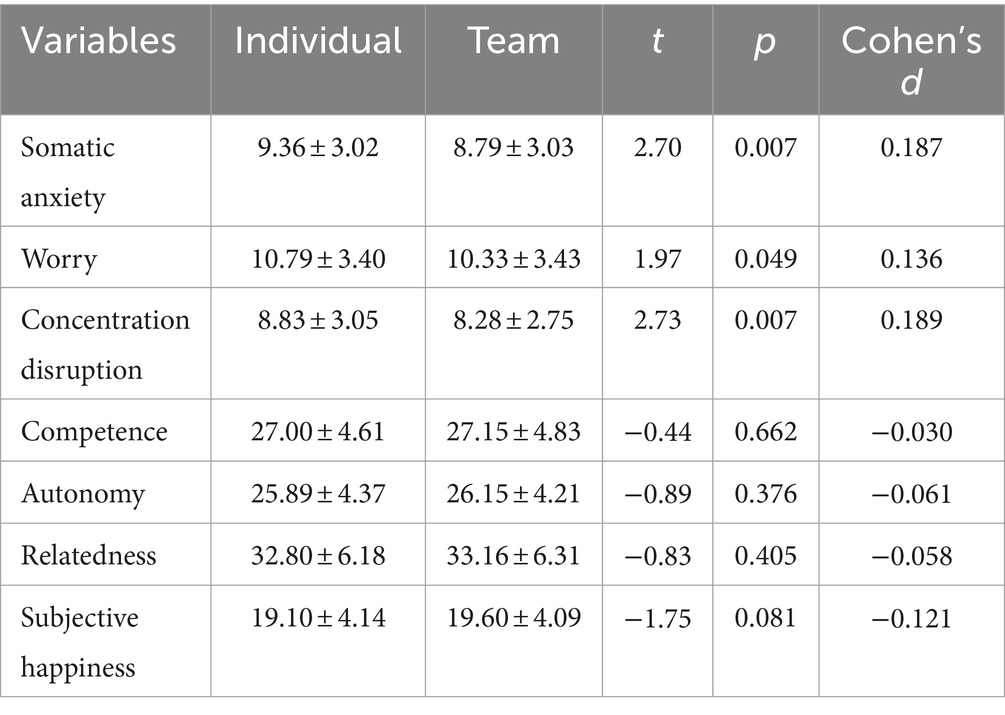

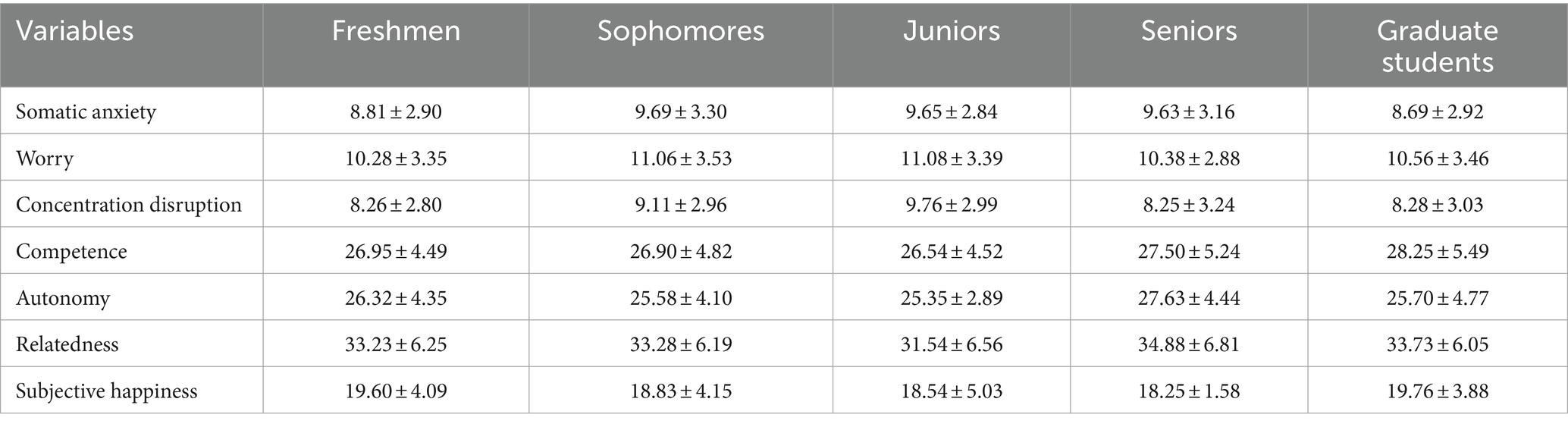

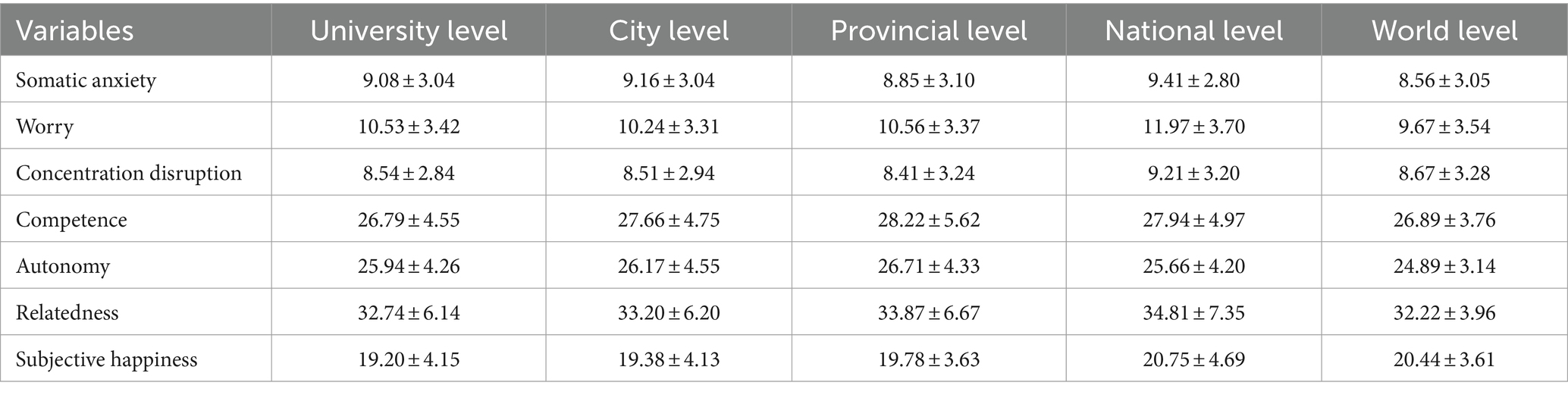

The characteristics of the included studies were summarized in Table 1 . After the screening, sixteen studies were included in this review; four were carried out in Italy, three in Spain, one in the United States, one in France, one in Portugal, one in Estonian, one in Sweden, one in Iran, one in Australia, one in Poland and one in South Africa. All studies had cross-sectional designs. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, all studies’ data were collected online through specific survey platforms ( n = 11), mails or WhatsApp ( n = 2), professional networks ( n = 3). Data collection was conducted between 9th March 2020 and 31st August 2020 during the initial phases of COVID-19 lockdown. All the studies recruited athletes in specific clusters (national and international level, Olympic qualifiers, professionals). Of sixteen studies, eight focused explicitly only on elite athletes, while seven studies were conducted both in amateur and elite athletes and then the subjects' outcomes were analyzed separately. The last one includes athlete affiliate to national federation, coaches and managers. Of sixteen studies, thirteen focused on participants aged 18 or older while three studies reported data also for < 18 years old; this data were excluded from the analysis. In total, 4475 elite athletes were surveyed, where the sample size of each study varied from 57 to 692 participants. All the studies reported gender distribution of the whole sample but only four studies specified gender distribution for elite athletes. In terms of the measured outcomes, fourteen studies used validated questionnaires while two studies used tools developed by authors. Of the sixteen studies that employed standardized measures nine reported reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for their samples, which was satisfactory from α = 0.66 to α = 0.93.

Mental health outcomes, coping strategies, resilience and athletes’ motivation

As shown in Table 1 , mental health outcomes examined by the studies included depression ( n = 6), anxiety ( n = 4), stress and psychological distress ( n = 5). Depression was investigated through DASS-21 ( n = 2) with non-pathological conditions found, and a specific questionnaire provided by authors ( n = 1) reported that most of 50% of athletes felt depressed. Depression was also investigated through PHQ-9 and GA by two studies. Anxiety was investigated by four studies, two connected to lockdown restrictions and two related to return to sport. Clemente-Suarez et al. [ 23 ] reported higher level of anxiety in Olympic athletes but in line with non-pathological conditions (through STAI short form); Leguizamo et al. [ 24 ] reported greater anxiety (through STAI-T) due to uncertainty of competition calendar. Ruffault et al. [ 25 ] reported higher level of cognitive anxiety in particular in public self-focus. Mehrsafar et al. [ 26 ] showed significant positive correlations between COVID-19 anxiety and somatic competitive anxiety, cognitive competitive anxiety, and competition response. Hakansson et al. [ 27 ] underlined that depression and anxiety were associated with feeling worse during the COVID-19 pandemic and with concern over one’s own sports future while Mehrsafar et al. [ 26 ] showed significant positive correlations between COVID-19 anxiety and somatic competitive anxiety and competition. In general, females showed higher levels of cognitive and physiological anxiety and lower scores of perceived controls. Stress and psychological distress were investigated by six studies. Di Fronso et al. [ 28 ] reported a high level of perceived stress. In this study [ 28 ], females reported higher levels of perceived stress. Furthermore, the higher levels of perceived stress was connected to higher dysfunctional and lower functional states and females reported greater levels of dysfunctional states than males. Different studies [ 24 , 27 , 29 , 30 ] measured the common symptoms related to stress and reported an increased level of stress symptoms especially in female athletes. Coping strategies ( n = 1) and resilience ( n = 1) were also investigated. Leguizamo et al. [ 24 ] reported that athletes often use coping strategies to react to situations. In the lockdown period, even if the stress perception increased, athletes that used coping strategies showed lower consequences. Emotional calming and cognitive structuring were the predominant strategies to cope with lockdown. Mon-Lopez et al. [ 31 ] reported that athletes’ resilience decreased with higher training intensity. Resilience became a positive predictor of perceived effort during training. Also, Szczypińska et al. [ 32 ] highlighted the importance of using adapted coping strategies to reduce stress and improve the mood state with positive reframing instead self-blaming strategy.

Finally, three studies investigated the motivation to continue training ( n = 1) or related to return to sport competition ( n = 2). Pillay et al. [ 33 ] reported that 55% of investigated athletes struggled to keep motivated to the training. Jagim et al. reported that 67% of investigated athletes had a reduction of level of training motivation with also lower training satisfaction. Ruffault et al. [ 25 ] reported that elite athletes had significant higher scores of external regulations of extrinsic motivation to return to sport.

Athletes’ profile mood state and personality

To determine possible repercussions on mental health related to specific athletes’ profile and personality, five studies investigated the mood state profile ( n = 2), athletes’ personality ( n = 1) and perfectionism ( n = 1). Leguizamo et al. [ 24 ] reported an ideal mood profile investigated, in line with the iceberg profile [ 34 ] in which the vigor factor is higher than other factors. These results was also confirmed by Szczypińska et al. [ 32 ] and Mon-Lopez et al. [ 31 ] Clemente-Suarez et al. [ 23 ] showed that a predominant of neuroticism personality in athletes led to a worse perception of confinement with higher impact on performance and training routines. Leguizamo et al. [ 24 ] also reported high level of perfectionism in elite athletes, in line with existing literature that was associated with higher performance [ 35 ].

COVID-19 emotional reactions

To cope with unique situations caused by COVID-19 lockdown, six studies investigated specific event impact on athlete’s emotion ( n = 1), acceptance ( n = 1) and emotion regulation ( n = 2). Di Cagno et al. [ 36 ] reported increased level of hyperarousal activation. In particular, females showed high scores on self-perceived stress as well as in the emotional avoidance-response behavior. Parm et al. [ 30 ] and Clemente-Suarez [ 23 ] reported higher scores of psychological inflexibility that lead to greatest negative feelings. Costa et al. [ 37 ] investigated individual differences in cognitive regulation and found that elite athletes in general had higher levels of “acceptance”, male showed higher levels of “planning” and “blame others” while females showed higher values of “putting things into perspectives” and “rumination”. Mon-Lopez et al. [ 31 ] showed that the athletes’ emotional intelligence impacted on training conditions and capacity to react to specific situations. In particular, the use of emotion became a positive predictor of perceived effort and number of training days.

Moreover, three studies investigated individual perceptions about COVID-19 with no-validated questionnaires. Clemente-Suarez et al. [ 23 ] found that elite athletes had high perception of social alarm, perceived a lack of support from institutions and had repercussions on training routines. Jagim et al. [ 38 ] highlighted a decrease in QoL due to lack of in-person support and social interaction with self-reported overall state of mental well-being approximately at a score of 50 on a scale 0–100. Pillay et al. [ 33 ] reported that 31% of investigated athletes felt unsure to return to sport because they were worried about the spread of virus.

This narrative review aimed to assess the effects of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on the mental health of elite athletes, identifying common psychological repercussions and their correlates. The overall findings of this review showed that the lockdown imposed by COVID-19 pandemic impacted elite athletes’ mental health. Due to the unique situations, many authors reported increased level of stress, anxiety and psychological distress in general population, primary connected to long period of quarantine, lack of social contact and fear of contract the virus. Athletes’ population seems to have reported less impact of these factors than the general population probably thanks to the capacity to react to adverse events and the use of adequate coping strategies [ 25 , 33 ]. The first model used in sports psychology was the Model of Sports Injuries [ 39 , 40 ] that with the similarity in the interruption of activity and the inherent uncertainty of the return to normal sports conditions reproduces a condition comparable to COVID-19 stop for lockdown. This model added other outcomes such as self-efficacy and environmental factors to anxiety and stress factors [ 41 ]. Generally, the authors reported increased level of stress due to the uncertainty of COVID-19 spread, the disarray of calendar competitions with repercussion on physical fitness and training sessions. Even if, augmented levels of stress and anxiety were found by different authors, they did not highlight the presence of any pathological conditions. Leguizamo et al. [ 24 ] showed negative correlations between the use of coping strategies in athletes, mainly on cognitive restructuring and emotional calming, and the emotional states commonly identified as negative, such as depression, stress and anxiety. Clemente-Suarez et al. [ 23 ] confirmed low-to-no impact of confinement on anxiety levels of Olympic athletes thanks to the larger experience of high-performance athletes in coping with competition-related anxiety and the existence of higher cognitive resources. Contradictory, Szczypińska et al. [ 32 ] showed that not all the coping strategies used by the athletes had positive effects on their mental health, in fact they showed that behavioral disengagement and self-blaming had negative effect on the mood of athletes. Additionally, results were found by Ruffault et al. [ 25 ] where the measure of anxiety was contextualized to return to sport. The results showed that athletes with higher levels of anxiety also recorded higher scores of controlled motivations. This is in line with Self-Determination Theory returning to sport to avoid threats or to get external rewards is associated with anticipatory thoughts that lead to cognitive anxiety [ 42 ]. Authors noted that investigated athletes self-reported changed to their training frequency, time spent doing training activities, motivation to train, enjoyment from training, training effort compared to pre-COVID-19 activities. These changes were predominately associated with the cessation of in-person organized team practices, coach–athletes social interaction and impossibilities to use common training facilities as part of the COVID-19 lockdown measures. The self-reported decrease in perceived training intensity could reduce an athlete’s state of physical readiness when a return to sport is possible. The increased risk of future injuries is another major concern related to proper physical training for sport and compete again. A previous study reported that the lack of adequate preparatory strength and conditioning period led to detraining effects and predisposed athletes to a greater risk of injuries during explosive activities [ 43 ]. Nevertheless, athletes who followed training programs during lockdown period (either developed by their staff or by other sources) were less anxious, perceived more control, and were more intrinsically motivated to return to sport after the confinement period. This is in line with theoretical models of return to sport in the context of sport injury [ 44 ]. In fact, continuing to train, keeping in contact with the staff or other athletes, having daily goals and activities, are optimal conditions for being confident in the return to sport with a lower loss in performance and the pleasure of practicing sport and competing again [ 45 ].

As previously reported, the athletes’ profile, personality and ability to regulate emotions could play a fundamental role in the prevention of mental health impairments and to react to adverse events. Elite athletes showed a complex motivation profile, with both high controlled and autonomous regulations. This is in line with a recent analysis of motivational processes in Olympic medalists that highlighted elite athletes’ influence from external factors [ 46 ]. The restrained environment linked with the COVID-19 lockdown could have enhanced this perception of external control such as fear of the loss of financial support and contracts. Many authors [ 24 , 31 , 32 ], highlighted that mood sates profile such as Vigor was the highest, clearly indicating that athletes did not experience a decrease in their “energy perception” during lockdown and the ability to maintain a positive reframing help them to cope with COVID-19 situations. These traits matched with the so-called “Iceberg profile” always associated with high performance in athletes [ 47 ]. In fact, Clemente-Suarez et al. [ 23 ] stated that athletes presented a high perception of social alarm, but the concern about COVID-19 pandemic was medium, probably because of the high control perception and personal care to avoid contagion. Additionally, correlation analysis showed that neuroticism personalities perceived that confinement produced negative impact in the subjective performance with repercussion on training routines and perceived lack of institutional support. The negative emotions associated to this personality trait may cause a poor adaptive behavior during the confinement situation [ 48 ]. On the contrary, openness trait presented higher control and personnel care perceptions, more adaptive behavior to the confinement than the neuroticism ones. In this line, the psychological inflexibility showed to be related with poor adaptive responses to the confinement led to high negative perception of sport performance, training routines and feeling of more loneliness. Psychological inflexibility is a factor that has been related to worse states of health and less contextual adaptability [ 49 ]. For this reason, psychological training has proven to be relevant in elite athletes to maintain a positive mood and more flexible and adequate coping strategies that are fundamental parameters to achieve high sport performance [ 50 , 51 , 52 ].

Studies included in this review reported gender differences in the mental health of elite athletes highlighting the importance of using a gender-based psychological training. In fact, Fiorilli et al. [ 29 ] showed that female athletes had higher levels than males, designed to assess current subjective distress. These results are also confirmed by Parm et al. [ 30 ], which showed that females had higher distress in COVID-19 period than males. Additionally, Costa et al. [ 37 ], found that cognitive emotion regulation strategies showed specific gender differences as previously highlighted [ 53 ], with women reporting to use more “rumination” and “catastrophizing”. The reason of these behaviors could be found in the tendency of women to express their emotions more than men [ 54 ], and this period of social isolation might have been an obstacle to this expressivity. Also, response styles theory assumptions [ 55 ] could explain tendency for women to ruminate when experiencing negative mood or circumstances, whereas men tend to distract themselves. This rumination can, in turn, increase the possibility to remain in a negative mood and perceive the circumstances as impacting mind and body, with increased anxiety [ 56 ]. Women emerged also as being more able to put things into perspective, whereas men used more the cognitive strategy of planning (i.e., to think about what steps to take and how to handle the negative event). These differences are novel in literature, as the CERQ has not yet reached widespread use in the sporting field. Moreover, elite athletes scored higher values in “planning” and “acceptance”, and lower values in “self-blame”, is in line with Ashfar et al. [ 57 ]. Also, elite athletes have emerged as having better strategies to emotionally cope with stressful situations [ 58 ]. Indeed, Di Cagno et al. [ 36 ] reported that women showed higher avoidance levels than males. Contrariwise, male athletes used social contacts to resolve stressful situations such as the sports activity withdrawal. Shuer and Dietrich [ 59 ] found that avoidance could be a psychological defense to actively remove unpleasant thoughts and situations. Athletes are often familiar to the use of dissociative strategies to separate life problems from their performance. This approach, defined as “compartmentalization”, could have masked the presence of the psychological symptoms in female athletes [ 60 ].

We are conscious that this study had some limitations. First, we were able to analyze only sixteen papers of the initial ninety-nine, only those were eligible according to the criteria. However, the results are of possible interest for future lines of study and intervention in the psychological field. Second, this review considered only studies published in English language, such that relevant studies conducted in non-English samples have been omitted. Finally, we did not find relevant information about the Paralympic elite athletes. In fact, in this study, we analyzed papers focused on mental health and psychological distress in athletes during the lockdown period, starting from our results new research should study the best coping strategies for athletes to deal with stressors. COVID-19 consequences remain unclear and the pandemic continues to be a matter of concern for both the public and the scientific community, so our study could be a starting point to include athletes’ mental health evaluation after a COVID-19 diagnosis.

Even if all the studies that we evaluated reported athletes higher perceived stress level, anxiety and psychological distress, the majority of participants were not substantially affected by the lockdown restrictions. The sports practice, in which athletes usually deal with stressful situations, such as competitive events, leads to achieve useful skills to manage anxiety and self-control in daily life. The athletes’ repeated exposure to exercise may have led to a stress response system adaptation and a negative cognitive appraisal. Elite athletes invest more in sport life and are able to better cope with stressful and uncertain situations [ 61 ]. Additionally, anxiety reduction techniques such as breathing exercises for physiological anxiety or mental exposure using imagery for cognitive anxiety may be taught to athletes with high anxiety [ 62 ]. Consequently, they may be able to transfer these skills from sport to the other life domains even during challenging times. Nevertheless, our review highlights the importance for coaches and physicians to keep under attention the level of stress and anxiety in elite athletes exacerbated from COVID-19 pandemic because these stressors can negatively influence the athletes’ performance and life. Sport psychologists and multidisciplinary interventions had to be implemented to early identify negative stressors and to help athletes to cope with these negative events to continue their careers and training in a safety way.

Armitage R, Nellums LB (2020) COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health 5:e256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Assaloni R, Pellino VC, Puci MV, Ferraro OE, Lovecchio N, Girelli A, Vandoni M (2020) Coronavirus disease (Covid-19): how does the exercise practice in active people with type 1 diabetes change? A preliminary survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 166:108297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108297

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Marroquín B, Vine V, Morgan R (2020) Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Res 293:113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

Tornaghi M, Lovecchio N, Vandoni M, Chirico A, Codella R (2021) Physical activity levels across COVID-19 outbreak in youngsters of Northwestern Lombardy. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 61:971–976. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.20.11600-1

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Vandoni M, Codella R, Pippi R, Carnevale Pellino V, Lovecchio N, Marin L, Silvestri D, Gatti A, Magenes VC, Regalbuto C et al (2021) Combatting sedentary behaviors by delivering remote physical exercise in children and adolescents with obesity in the COVID-19 era: a narrative review. Nutrients 13:4459. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13124459

Calcaterra V, Iafusco D, Pellino VC, Mameli C, Tornese G, Chianese A, Cascella C, Macedoni M, Redaelli F, Zuccotti G et al (2021) “CoVidentary”: an online exercise training program to reduce sedentary behaviours in children with type 1 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Transl Endocrinol 25:100261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100261

Pons J, Ramis Y, Alcaraz S, Jordana A, Borrueco M, Torregrossa M (2020) Where did all the sport go? Negative impact of COVID-19 lockdown on life-spheres and mental health of Spanish young athletes. Front Psychol 11:3498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.611872

Article Google Scholar

Samuel RD, Tenenbaum G, Galily Y (2020) The 2020 coronavirus pandemic as a change-event in sport performers’ careers: conceptual and applied practice considerations. Front Psychol 11:2522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567966

Woods JA, Hutchinson NT, Powers SK, Roberts WO, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Radak Z, Berkes I, Boros A, Boldogh I, Leeuwenburgh C et al (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sports Med Health Sci 2:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2020.05.006

Hammami A, Harrabi B, Mohr M, Krustrup P (2020) Physical activity and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): specific recommendations for home-based physical training. Manag Sport Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1757494

Natalucci V, Carnevale Pellino V, Barbieri E, Vandoni M (2020) Is It important to perform physical activity during coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19)? Driving action for a correct exercise plan. Front Public Health 8:602020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.602020

Jukic I, Calleja-González J, Cos F, Cuzzolin F, Olmo J, Terrados N, Njaradi N, Sassi R, Requena B, Milanovic L et al (2020) Strategies and solutions for team sports athletes in isolation due to COVID-19. Sports. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports8040056

APA Dictionary of Psychology Definition of Psychological Distress. https://dictionary.apa.org/psychological-distress . Accesed 23 Dec 2021

Sarto F, Impellizzeri FM, Spörri J, Porcelli S, Olmo J, Requena B, Suarez-Arrones L, Arundale A, Bilsborough J, Buchheit M et al (2020) Impact of Potential physiological changes due to COVID-19 home confinement on athlete health protection in elite sports: a call for awareness in sports programming. Sports Med 50:1417–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01297-6

Elliott N, Martin R, Heron N, Elliott J, Grimstead D, Biswas A (2020) Infographic. Graduated return to play guidance following COVID-19 infection. Br J Sports Med 54:1174–1175. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102637

Mohr M, Nassis GP, Brito J, Randers MB, Castagna C, Parnell D, Krustrup P (2020) Return to elite football after the COVID-19 lockdown. Manag Sport Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1768635

Fikenzer S, Fikenzer K, Laufs U, Falz R, Pietrek H, Hepp P (2020) Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on endurance capacity of elite handball players. J Sports Med Phys Fit. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.20.11501-9

Stokes KA, Jones B, Bennett M, Close GL, Gill N, Hull JH, Kasper AM, Kemp SPT, Mellalieu SD, Peirce N et al (2020) Returning to play after prolonged training restrictions in professional collision sports. Int J Sports Med 41:895–911. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1180-3692

Grupe DW, Nitschke JB (2013) Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:488–501. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3524

Schinke R, Papaioannou A, Henriksen K, Si G, Zhang L, Haberl P (2020) Sport psychology services to high performance athletes during COVID-19. Int J Sport Exercis Psychol 18:269–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1754616

Arnold R, Fletcher D (2012) A research synthesis and taxonomic classification of the organizational stressors encountered by sport performers. J Sport Exerc Psychol 34:397–429. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.34.3.397

Rodgers M, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Roberts H, Britten N, Popay J (2009) Testing methodological guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: effectiveness of interventions to promote smoke alarm ownership and function. Evaluation 15:49–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389008097871

Clemente-Suárez VJ, Fuentes-García JP, de la Vega Marcos R, Martínez Patiño MJ (2020) Modulators of the personal and professional threat perception of olympic athletes in the actual COVID-19 crisis. Front Psychol 11:1985. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01985

Leguizamo F, Olmedilla A, Núñez A, Verdaguer FJP, Gómez-Espejo V, Ruiz-Barquín R, Garcia-Mas A (2021) Personality, coping strategies, and mental health in high-performance athletes during confinement derived from the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health 8:924. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.561198

Ruffault A, Bernier M, Fournier J, Hauw N (2020) Anxiety and motivation to return to sport during the French COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol 11:3467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.610882

Mehrsafar AH, Moghadam Zadeh A, Jaenes Sánchez JC, Gazerani P (2021) Competitive anxiety or coronavirus anxiety? The psychophysiological responses of professional football players after returning to competition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology 129:105269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105269

Håkansson A, Jönsson C, Kenttä G (2020) Psychological distress and problem gambling in elite athletes during COVID-19 restrictions—a web survey in top leagues of three sports during the pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:E6693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186693

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

di Fronso S, Costa S, Montesano C, Gruttola FD, Ciofi EG, Morgilli L, Robazza C, Bertollo M (2020) The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on perceived stress and psychobiosocial states in Italian athletes. Int J Sport Exercis Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1802612

Fiorilli G, Grazioli E, Buonsenso A, Di Martino G, Despina T, Calcagno G, di Cagno A (2021) A national COVID-19 quarantine survey and its impact on the Italian sports community: implications and recommendations. PLoS One 16:e0248345. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248345

Parm Ü, Aluoja A, Tomingas T, Tamm A-L (2021) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on estonian elite athletes: survey on mental health characteristics, training conditions, competition possibilities, and perception of supportiveness. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:4317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084317

Mon-López D, de la Rubia Riaza A, Hontoria Galán M, Refoyo Roman I (2020) The impact of Covid-19 and the effect of psychological factors on training conditions of handball players. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186471

Szczypińska M, Samełko A, Guszkowska M (2021) What predicts the mood of athletes involved in preparations for Tokyo 2020/2021 Olympic Games during the Covid—19 pandemic? The role of sense of coherence, hope for success and coping strategies. J Sports Sci Med 20:421–430. https://doi.org/10.52082/jssm.2021.421

Pillay L, Janse Van Rensburg DCC, Jansen Van Rensburg A, Ramagole DA, Holtzhausen L, Dijkstra HP, Cronje T (2020) Nowhere to hide: the significant impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) measures on elite and semi-elite south african athletes. J Sci Med Sport 23:670–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.05.016

Renger R (1993) A review of the profile of mood states (POMS) in the prediction of athletic success. J Appl Sport Psychol 5:78–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209308411306

Iancheva T, Rogaleva L, Garcia-Mas A, Zafra A (2020) Perfectionism, mood states, and coping strategies of sports students from Bulgaria and Russia during the pandemic COVID-19. J Appl Sports Sci 1:22–38. https://doi.org/10.37393/JASS.2020.01.2

di Cagno A, Buonsenso A, Baralla F, Grazioli E, Di Martino G, Lecce E, Calcagno G, Fiorilli G (2020) Psychological impact of the quarantine-induced stress during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak among Italian athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17238867

Costa S, Santi G, di Fronso S, Montesano C, Di Gruttola F, Ciofi EG, Morgilli L, Bertollo M (2020) Athletes and adversities: athletic identity and emotional regulation in time of COVID-19. Sport Sci Health 16:609–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-020-00677-9

Jagim AR, Luedke J, Fitzpatrick A, Winkelman G, Erickson JL, Askow AT, Camic CL (2020) The impact of COVID-19-related shutdown measures on the training habits and perceptions of athletes in the United States: a brief research report. Front Sports Active Living 2:208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.623068

Andersen MB, Williams JM (1988) A model of stress and athletic injury: prediction and prevention. J Sport Exerc Psychol 10:294–306

Zafra A, El Garcia-Mas A (2009) Modelo Global Psicológico de Las Lesiones Deportivas [A Global Psychological Model of the Sportive Injuries]. Acción Psicológica. https://doi.org/10.5944/ap.6.2.223

García-Jiménez ME, Ruíz T, Mars L, García-Garcés P (2014) Changes in the scheduling process according to observed activity-travel flexibility. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 160:484–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.161

Ryan R, Deci E (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55:68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Chu DA, Falkel J, Ford KR, Best TM, Hewett TE (2011) Integrative training for children and adolescents: techniques and practices for reducing sports-related injuries and enhancing athletic performance. Phys Sportsmed 39:74–84. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2011.02.1854

Wiese-Bjornstal DM (2019) Psychological predictors and consequences of injuries in sport settings. In: APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology, volume 1: sport psychology, vol. 1; APA handbooks in psychology series; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US,; pp. 699–725 ISBN 143383040X.

Hogue CM (2019) The protective impact of a mental skills training session and motivational priming on participants’ psychophysiological responses to performance stress. Psychol Sport Exerc 45:101574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101574

Jordalen G, Lemyre P-N, Durand-Bush N (2020) Interplay of motivation and self-regulation throughout the development of elite athletes. Qualitat Res Sport Exercise Health 12:377–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1585388

Morgan PW (1985) Selected psychological factors limiting performance—a mental health model. Limits of Human Performance, 70–80

Harkness AR, McNulty JL, Ben-Porath YS (1995) The personality psychopathology five (PSY-5): constructs and MMPI-2 scales. Psychol Assess 7:104–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.104

Woodruff SC, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, Crowley KJ, Hindman RK, Hirschhorn EW (2014) Comparing self-compassion, mindfulness, and psychological inflexibility as predictors of psychological health. Mindfulness 5:410–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0195-9

Mummery S (2004) Caperchione physical activity: physical activity dose-response effects on mental health status in older adults. Australian New Zealand J Public Health 28:5

Belinchon-deMiguel P, Clemente-Suárez VJ (2018) Psychophysiological, body composition, biomechanical and autonomic modulation analysis procedures in an ultraendurance mountain race. J Med Syst 42:32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-017-0889-y

Belinchón-deMiguel P, Tornero-Aguilera JF, Dalamitros AA, Nikolaidis PT, Rosemann T, Knechtle B, Clemente-Suárez VJ (2019) Multidisciplinary analysis of differences between finisher and non-finisher ultra-endurance mountain athletes. Front Physiol 10:1507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01507

Balzarotti S, Biassoni F, Villani D, Prunas A, Velotti P (2016) Individual differences in cognitive emotion regulation: implications for subjective and psychological well-being. J Happiness Stud 17:125–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9587-3

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85:348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Sex Differences in Depression.; sex differences in depression.; Stanford University Press, 1990; pp. vii, 258; ISBN 0–8047-1640-4.

Hankin BL, Abramson LY (1999) Development of gender differences in depression: description and possible explanations. Ann Med 31:372–379. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853899908998794

Shirvani H, Barabari A, Keshavarz Afshar H (2015) A comparison of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in semi professional and amateur athletes. J Military Med 16(4):237–242

Polman E (2012) Self-other decision making and loss aversion. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 119:141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.06.005

Shuer ML, Dietrich MS (1997) Psychological effects of chronic injury in elite athletes. West J Med 166:104–109

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Poucher Z, Tamminen K (2017) Maintaining and managing athletic Identity among elite athletes. Revista de Psicologia del Deporte 26:63–67

Google Scholar

Pensgaard AM, Duda JL (2003) Sydney 2000: the interplay between emotions, coping, and the performance of olympic-level athletes. Sport Psychologist 17:253–267. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.17.3.253

van Dis EAM, van Veen SC, Hagenaars MA, Batelaan NM, Bockting CLH, van den Heuvel RM, Cuijpers P, Engelhard IM (2020) Long-term outcomes of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety-related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat 77:265–273. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3986

Facer-Childs ER, Hoffman D, Tran JN, Drummond SPA, Rajaratnam SMW (2021) Sleep and mental health in athletes during COVIDf19 lockdown. Sleep. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsaa261

Download references

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Laboratory of Adapted Motor Activity (LAMA)- Department of Public Health, Experimental Medicine and Forensic Science, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

Vittoria Carnevale Pellino, Luca Marin, Alessandro Gatti, Agnese Pirazzi, Francesca Negri & Matteo Vandoni

Department of Industrial Engineering, University of Tor Vergata Rome, Rome, Italy

Vittoria Carnevale Pellino

Department of Human and Social Science, University of Bergamo, Bergamo, Italy

Nicola Lovecchio

Unit of Biostatistics and Clinical Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, Experimental Medicine and Forensic Science, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy

Mariangela V. Puci & Ottavia E. Ferraro

Laboratory for Rehabilitation Medicine and Sport (LARMS), 00133, Rome, Italy

Department of Research, ASOMI College of Sciences, Marsa, 2080, Malta

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vittoria Carnevale Pellino .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval and Informed consent

This work is a review paper and it does not deserve the Ethical approval and informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised to add missing OASIS funding note.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Carnevale Pellino, V., Lovecchio, N., Puci, M.V. et al. Effects of the lockdown period on the mental health of elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Sport Sci Health 18 , 1187–1199 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-022-00964-7

Download citation

Received : 26 January 2022

Accepted : 11 May 2022

Published : 08 June 2022

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-022-00964-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Elite athletes

- Psychological distress

- Mental health

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

The impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity

A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis.

Ding, Yunxia PhD a ; Ding, Song MD b,∗ ; Niu, Jiali MD c

a Sports Industry and Leisure College, Nanjing Sport Institute, Jiangsu, China

b Department of Infection, Jingjiang People's Hospital, the Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, Jiangsu, China

c Department of Pharmacy, Jingjiang People's Hospital, the Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, Jiangsu, China.

∗Correspondence: Song Ding, No. 28, Zhongzhou Road, Jingjiang, Jiangsu 214500, China (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Abbreviation: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

How to cite this article: Ding Y, Ding S, Niu J. The impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine . 2021;100:35(e27111).

This work was funded by the 2021 Universities "Qing Lan Project" Training Objects of Jiangsu Education Department and Jiangsu Social Science Foundation (20HQ041). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approval is not required, and the review will be reported in a peer-reviewed journal.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

All the data pertaining to the present study are willing to share upon reasonable request.

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 (CCBY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

Background:

We aimed to conduct a meta-analysis to assess the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on college students’ physical activity.

Methods:

All cohort studies comparing college students undertaking physical exercise at school before the COVID-19 pandemic and physical exercise at home during the COVID-19 pandemic will be included in this review. We will use index words related to college students, physical exercise, and COVID-19 to perform literature searches in the PubMed, Medline, Embase, and CNKI databases, to include articles indexed as of June 20, 2021, in English and Chinese. Two reviewers will independently select trials for inclusion, assess trial quality, and extract information for each trial. The primary outcomes are exercise frequency, duration, intensity, and associated factors. Based on the Cochrane assessment tool, we will evaluate the risk of bias of the included studies. Revman 5.3 (the Cochrane collaboration, Oxford, UK) will be used for heterogeneity assessment, data synthesis, subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and funnel plot generation.

Result:

We will discuss the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity.

Conclusion:

Stronger evidence about the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity will be provided to better guide teaching practice.

Systematic review registration:

PROSPERO CRD42021262390.

1 Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global pandemic [1] leading to a global shutdown that closed schools for months. [2,3] In many nations, schools were closed to students, [4] and teachers directed educational activities remotely via digital devices or homeschooling resources. [5] However, in contrast to exercising at school, home exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic was affected by various factors, [6,7] such as limited venues, family sports atmosphere, and incomplete equipment, it was difficult for college students to reach school requirements. [8–11]

To promote college students’ active participation in physical exercise and provide reference for teaching practice, we aim to conduct a meta-analysis of cohort studies to assess the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity.

2.1 Registration

This protocol was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on July 1 as CRD42021262390. In this paper, we will perform the protocol according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols guidelines. [12,13]

2.2 Inclusion criteria for considering studies

2.2.1 types of studies.

All cohort studies comparing college students undertaking physical exercise at school before the COVID-19 pandemic and physical exercise at home during the COVID-19 pandemic will be included in this review.

2.2.2 Types of participants

College students, grade 1 to 4.

2.2.3 Types of interventions

The impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity.

2.2.4 Types of outcome assessments

Any available information about the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activities will be assessed. The primary outcomes are exercise frequency, duration, intensity, and associated factors.

2.3 Search strategy

We will use index words related to college students’ physical activity and COVID-19 to perform literature searches in the PubMed, Embase, Medline, and CNKI databases, to include articles indexed as of June 20, 2021, in English and Chinese. The key search terms will be used are [“Exercises” OR “Physical Activity” OR “Activities, Physical” OR “Activity, Physical” OR “Physical Activities” OR “Exercise, Physical” OR “Exercises, Physical” OR “Physical Exercise” OR “Physical Exercises” OR “Acute Exercise” OR “Acute Exercises” OR “Exercise, Acute” OR “Exercises, Acute” OR “Exercise, Isometric” OR “Exercises, Isometric” OR “Isometric Exercises” OR “Isometric Exercise” OR “Exercise, Aerobic” OR “Aerobic Exercise” OR “Aerobic Exercises” OR “Exercises, Aerobic” OR “Exercise Training” OR “Exercise Trainings” OR “Training, Exercise” OR “Trainings, Exercise” AND “2019 novel coronavirus disease” OR “COVID19” OR “COVID-19 pandemic” OR “SARS-CoV-2 infection” OR “COVID-19 virus disease” OR “2019 novel coronavirus infection” OR “2019-nCoV infection” OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “coronavirus disease-19” OR “2019-nCoV disease” OR “COVID-19 virus infection”].

2.4 Data collection

2.4.1 selection of studies.

Two reviewers will independently select trials for inclusion. Articles will be excluded if they meet any of the following criteria: the object is not a college student, fewer than 10 students, and studies not comparing college students undertaking physical exercise at school before the COVID-19 pandemic undertaking physical exercise at home during COVID-19 pandemic. The study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1 .

2.4.2 Data and information extraction

Two authors will extract general information independently for each included trial, including the name of the first author, year, country, design, sample size, average age, and sex ratio. The third author will check all the data.

In the same manner, we will extract the data for impact assessments. For each study, we will extract the following information: exercise frequency, duration, intensity, and associated factors. We will resolve the disagreements through discussion.

2.5 Assessment of risk of bias

The review authors will independently assess the quality of the trials included in the review, in accordance with Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), by allocation concealment (selection bias); blinding (performance bias and detection bias); blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias); blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias); incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); selective reporting (reporting bias); and other bias. The fifth author will check all the data. We will use this information to evaluate quality and resolve disagreements by discussion until a consensus is reached.

2.6 Data analysis

2.6.1 assessment of heterogeneity.

We will use chi-square test and I 2 statistic to assess heterogeneity. If the heterogeneity is within the acceptable range ( P > .10, I 2 < 50%), the fixed effects model shall be used for data analysis; otherwise, the random effects model will be used.

2.6.2 Date synthesis

Two authors will extract information independently for each trial. The third author will check all the data. Review Manager 5.3 (the Cochrane collaboration, Oxford, UK) will be used to assess the risk of bias, heterogeneity, sensitivity, and subgroup analysis. We will calculate a weighted estimate across trials and interpret of the results. Statistical significance will be set at P < .05.

2.6.3 Subgroup analysis

We will perform the following subgroup analysis to explore the possible causes of high heterogeneity: grade (1, 2, 3, and 4), gender (male and female), and different counties.

2.6.4 Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis will be conducted by excluding trials one by one and observing whether the synthesis result changes significantly. If there are significant changes, we will cautiously make a decision to decide whether to merge them. If there is little change, this indicates that our synthesized result is firm.

2.7 Assessment of publication bias

If more than 10 articles are available for analysis, funnel plots will be generated to assess publication bias. A symmetrical distribution of funnel plot data indicates that there is no publication bias; otherwise, we will analyze the potential reasons for this outcome and provide a reasonable interpretation for asymmetric funnel plots.

2.8 Confidence in cumulative evidence

The Grades of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation system will be used to assess the quality of our evidence. [14] According to the grading system, the level of evidence will be rated as high, moderate, low, and very low.

3 Discussion

COVID-19 is an emerging, rapidly evolving situation that leads to global shutdown. [15] Schools were closed for months, and students took online courses at home. [16,17] It was very important to pay attention to the physical and mental health of students and to guide students in strengthening exercises. Teachers encouraged students to perform physical exercise through various methods, such as online physical education, assigning exercise assignments, and cloud competitions. However, home physical exercises rely more on students’ independent practices, and teachers lack effective monitoring. [18] The physical exercise of college students at home may not meet the standards. [19,20]

By conducting a meta-analysis of related cohort studies, we will provide the impact of COVID-19 on college students’ physical activity to better guide teaching practice.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yunxia Ding, Song Ding, Jiali Niu.

Investigation: Yunxia Ding, Song Ding, Jiali Niu.

Methodology: Yunxia Ding, Song Ding, Jiali Niu.

Software: Yunxia Ding, Jiali Niu.

Supervision: Yunxia Ding, Song Ding, Jiali Niu.

Writing – original draft: Yunxia Ding, Song Ding, Jiali Niu.

Writing – review & editing: Yunxia Ding, Song Ding, Jiali Niu.

- Cited Here |

- View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef |

- Google Scholar

- PubMed | CrossRef |

college students; coronavirus disease 2019; meta-analysis; physical activity

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

UN/DESA Policy Brief #73: The impact of COVID-19 on sport, physical activity and well-being and its effects on social development

Introduction

Sport is a major contributor to economic and social development. Its role is well recognized by Governments, including in the Political Declaration of the 2030 Agenda, which reflects on “the contribution sports make to the empowerment of women and of young people, individuals and communities, as well as to health, education and social inclusion objectives.”

Since its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic has spread to almost all countries of the world. Social and physical distancing measures, lockdowns of businesses, schools and overall social life, which have become commonplace to curtail the spread of the disease, have also disrupted many regular aspects of life, including sport and physical activity. This policy brief highlights the challenges COVID-19 has posed to both the sporting world and to physical activity and well-being, including for marginalized or vulnerable groups. It further provides recommendations for Governments and other stakeholders, as well as for the UN system, to support the safe reopening of sporting events, as well as to support physical activity during the pandemic and beyond.

The impact of COVID-19 on sporting events and the implications for social development

To safeguard the health of athletes and others involved, most major sporting events at international, regional and national levels have been cancelled or postponed – from marathons to football tournaments, athletics championships to basketball games, handball to ice hockey, rugby, cricket, sailing, skiing, weightlifting to wrestling and more. The Olympics and Paralympics, for the first time in the history of the modern games, have been postponed, and will be held in 2021.

The global value of the sports industry is estimated at US$756 billion annually. In the face of COVID-19, many millions of jobs are therefore at risk globally, not only for sports professionals but also for those in related retail and sporting services industries connected with leagues and events, which include travel, tourism, infrastructure, transportation, catering and media broadcasting, among others. Professional athletes are also under pressure to reschedule their training, while trying to stay fit at home, and they risk losing professional sponsors who may not support them as initially agreed.

Major sporting organisations have shown their solidarity with efforts to reduce the spread of the virus. For example, FIFA has teamed up with the World Health Organisation (WHO) and launched a ‘Pass the message to kick out coronavirus’ campaign led by well-known football players in 13 languages, calling on people to follow five key steps to stop the spread of the disease focused on hand washing, coughing etiquette, not touching one’s face, physical distance and staying home if feeling unwell. Other international sport for development and peace organizations have come together to support one another in solidarity during this time, for example, through periodic online community discussions to share challenges and issues. Participants in such online dialogues have also sought to devise innovative solutions to larger social issues, for example, by identifying ways that sporting organisations can respond to problems faced by vulnerable people who normally participate in sporting programmes in low income communities but who are now unable to, given restriction to movement.

The closure of education institutions around the world due to COVID-19 has also impacted the sports education sector, which is comprised of a broad range of stakeholders, including national ministries and local authorities, public and private education institutions, sports organizations and athletes, NGOs and the business community, teachers, scholars and coaches, parents and, first and foremost, the – mostly young – learners. While this community has been severely impacted by the current crisis, it can also be a key contributor to solutions to contain and overcome it, as well as in promoting rights and values in times of social distancing.

As the world begins to recover from COVID-19, there will be significant issues to be addressed to ensure the safety of sporting events at all levels and the well-being of sporting organizations. In the short term, these will include the adaptation of events to ensure the safety of athletes, fans and vendors, among others. In the medium term, in the face of an anticipated global recession, there may also be a need to take measures to support participation in sporting organizations, particularly for youth sports.

The impact of COVID-19 on physical activity and well-being