An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Ethnobiol Ethnomed

Quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation and molecular confirmation of medicinal plants used by the Manobo tribe of Agusan del Sur, Philippines

Mark lloyd g. dapar.

1 The Graduate School and Research Center for the Natural and Applied Sciences, University of Santo Tomas, España Boulevard, 1015 Manila, Philippines

3 Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Universitätsstr. 30, 95440 Bayreuth, Germany

Grecebio Jonathan D. Alejandro

2 College of Science, University of Santo Tomas, España Boulevard, 1015 Manila, Philippines

Ulrich Meve

Sigrid liede-schumann, associated data.

The authors declare that sequencing data of 24 species identified supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary information files.

The Philippines is renowned as one of the species-rich countries and culturally megadiverse in ethnicity around the globe. However, ethnopharmacological studies in the Philippines are still limited especially in the most numerous ethnic tribal populations in the southern part of the archipelago. This present study aims to document the traditional practices, medicinal plant use, and knowledge; to determine the relative importance, consensus, and the extent of all medicinal plants used; and to integrate molecular confirmation of uncertain species used by the Agusan Manobo in Mindanao, Philippines.

Quantitative ethnopharmacological data were obtained using semi-structured interviews, group discussions, field observations, and guided field walks with a total of 335 key informants comprising of tribal chieftains, traditional healers, community elders, and Manobo members of the community with their medicinal plant knowledge. The use-report (UR), use categories (UC), use value (UV), cultural importance value (CIV), and use diversity (UD) were quantified and correlated. Other indices using fidelity level (FL), informant consensus factors (ICF), and Jaccard’s similarity index (JI) were also calculated. The key informants’ medicinal plant use knowledge and practices were statistically analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics.

This study enumerated the ethnopharmacological use of 122 medicinal plant species, distributed among 108 genera and belonging to 51 families classified in 16 use categories. Integrative molecular approach confirmed 24 species with confusing species identity using multiple universal markers (ITS, mat K, psb A- trn H, and trn L-F). There was strong agreement among the key informants regarding ethnopharmacological uses of plants, with ICF values ranging from 0.97 to 0.99, with the highest number of species (88) being used for the treatment of abnormal signs and symptoms (ASS). Seven species were reported with maximum fidelity level (100%) in seven use categories. The correlations of the five variables (UR, UC, UV, CIV, and UD) were significant ( r s ≥ 0.69, p < 0.001), some being stronger than others. The degree of similarity of the three studied localities had JI ranged from 0.38 to 0.42, indicating species likeness among the tribal communities. Statistically, the medicinal plant knowledge among respondents was significantly different ( p < 0.001) when grouped according to education, gender, social position, occupation, civil status, and age but not ( p = 0.379) when grouped according to location. This study recorded the first quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation coupled with molecular confirmation of medicinal plants in Mindanao, Philippines, of which one medicinal plant species has never been studied pharmacologically to date.

Documenting such traditional knowledge of medicinal plants and practices is highly essential for future management and conservation strategies of these plant genetic resources. This ethnopharmacological study will serve as a future reference not only for more systematic ethnopharmacological documentation but also for further pharmacological studies and drug discovery to improve public healthcare worldwide.

Introduction

The application of traditional medicine has gained renewed attention for the use of traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine (TCAM) in the developing and industrialized countries [ 1 , 2 ]. Conventional drugs these days may serve as effective medicines and therapeutics, but some rural communities still prefer natural remedies to treat selected health-related problems and conditions. Medicinal plants have long been used since the prehistoric period [ 3 ], but the exact time when the use of plant-based drugs has begun is still uncertain [ 4 ]. The WHO has accounted about 60% of the world’s population relying on traditional medicine and 80% of the population in developing countries depend almost entirely on traditional medical practices, in particular, herbal remedies, for their primary health care [ 5 ]. Estimates for the numbers of plant species used medicinally worldwide include 35,000–70,000 [ 6 ] with 7000 in South Asia [ 7 ] comprising ca. 6500 in Southeast Asia [ 8 , 9 ]. In the Philippines, more than 1500 medicinal plants used by traditional healers have been documented [ 10 ], and 120 plants have been scientifically validated for safety and efficacy [ 11 ]. Of all documented Philippine medicinal plants, the top list of medicinal plants used for TCAM has been enumerated by [ 12 ]. Most of these Philippine medicinal plants have been evaluated to scientifically validate folkloric claims like the recent studies of [ 13 – 20 ].

Because of the increasing demand for drug discovery and development of medicinal plants, the application of a quantitative approach in ethnobotany [ 21 ] and ethnopharmacology [ 22 ] has been rising continuously in the last few decades including multivariate analysis [ 23 ]. However, few studies of quantitative ethnobotanical research were conducted despite the rich plant biodiversity and cultural diversity in the Philippines. In particular, the Ivatan community in Batan Island of Luzon [ 24 ] and the Ati Negrito community in Guimaras Island of Visayas [ 21 ] have been documented, while Mindanao has remained less studied. Despite the richness of indigenous knowledge in the Philippines, few ethnobotanical studies have been conducted and published [ 25 ].

The Philippines is culturally megadiverse in diversity and ethnicity among indigenous peoples (IPs) embracing more than a hundred divergent ethnolinguistic groups [ 26 , 27 ] with known specific identity, language, socio-political systems, and practices [ 28 ]. Of these IPs, 61% are mainly inhabiting Mindanao, followed by Luzon with 33%, and some groups in Visayas (6%) [ 29 ]. One of these local people and minorities is the indigenous group of Manobo , inhabiting several areas only in Mindanao. They are acknowledged to be the largest Philippine ethnic group occupying a wide area of distribution than other indigenous communities like the Bagobo, Higaonon, and Atta [ 30 ]. The Manobo (“river people”) was the term named after the “Mansuba” which means river people [ 19 ], coined from the “man” (people) and the “suba” (river) [ 31 ]. Among the provinces dwelled by the Manobo , the province of Agusan del Sur is mostly inhabited by this ethnic group known as the Agusan Manobo . The origin of Agusan Manobo is still uncertain and immemorial; however, they are known to have Butuano, Malay, Indonesian, and Chinese origin occupying mountain ranges and hinterlands in the province of Agusan del Sur [ 32 ].

Manobo indigenous peoples are clustered accordingly, occupying areas with varying dialects and some aspects of culture due to geographical separation. Their historic lifestyle and everyday livelihood are rural agriculture and primarily depend on their rice harvest, root crops, and vegetables for consumption [ 33 ]. Some Agusan Manobo are widely dispersed in highland communities above mountain drainage systems, indicating a suitable area for their indigenous medicinal plants in the province [ 34 ]. Every city or municipality is governed with a tribal chieftain known as the “Datu” (male) or “Bae” (female) with his or her respective tribal healer “Babaylan” and the tribal leaders “Datu” of each barangay (village) leading their community. Their tribe has passed several challenges over the years but has still maintained to conserve and protect their ancestral domain to continually sustain their cultural traditions, practices, and values up to this present generation. This culture implies that there is rich medicinal plant knowledge in the traditional practices of Agusan Manobo , but their indigenous knowledge has not been systematically documented. Furthermore, there are no comprehensive ethnobotanical studies of medicinal plants used among the Manobo tribe in the Philippines to date.

Documenting the ethnomedicinal plant use and knowledge, and molecular confirmation of species using integrative molecular approach will help in understanding the true identity of medicinal plants in the treatment of health-related problems of the people of Agusan del Sur. This will also help the entire Agusan Manobo community to implement conservation priorities of their indigenous plant species. Furthermore, the provincial government of Agusan del Sur may enforce the proper utilization of their plant resources from IPs. Ideas and knowledge about ethnomedicinal use and practices of medicinal plants give credence to the traditional methods and preparation of herbal medicine by ethnic groups.

Despite the limited funds and qualified personnel in the region, it is very relevant to recognize the role of ethnopharmacology and species identification in the conservation of these plant genetic resources with medicinal properties. With the introduction of the application of molecular barcodes for species identification by [ 35 ], the problem of unauthenticated medicinal species can now be resolved [ 19 , 36 – 43 ].

Significantly, researchers have recently developed the application of ethnopharmacological study into a quantitative approach with measuring values and indices to quantify the relationship between plant species and humans [ 44 – 48 ].

This study, therefore, aims to (1) conduct quantitative ethnopharmacological documentation of traditional therapy, (2) evaluate the medicinal plant use and knowledge, and (3) utilize integrative molecular approach for species confirmation of medicinal plants used by the Manobo tribe in Agusan del Sur, Philippines.

Materials and methods

Fieldwork was conducted in the province of Agusan del Sur, Philippines (8° 30′ N 125° 50′ E), bordered from the north by Agusan del Norte, to the south by Davao del Norte, and from the west by Misamis Oriental and Bukidnon, to the east by Surigao del Sur. Agusan del Sur is bounded with mountain ranges from the eastern and western sides forming an elongated basin or valley in the center longitudinal section of the land. The province is subdivided into 13 municipalities (from the largest to smallest land area): La Paz, Esperanza, Loreto, San Luis, Talacogon, Sibagat, Prosperidad, Bunawan, Trento, Veruela, Rosario, San Francisco, and Sta. Josefa; and the only component city, the City of Bayugan (Fig. (Fig.1). 1 ). Forestland comprises almost two thirds (74%) of the province of Agusan del Sur, while alienable and disposable (A&D) areas constitute around one-third (26%) of the total land area [ 49 ]. Every city or municipality has a respective community hospital and health center with limited doctors and rural health workers. Typically, local people only visit the hospitals or health centers for surgical and obstetric emergencies. Most residents rely on their medicinal plants for disease treatment and medication due to cost and poor access to healthcare services. This study purposively covered areas of selected city and municipalities (Bayugan, Esperanza, and Sibagat) for accessibility, availability, and security reasons to barangays (villages) with Certification of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) as endorsed by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples—CARAGA Administrative Region (NCIP-CARAGA).

Study sites (barangays) from the only city (Bayugan), and the two selected municipalities (Esperanza and Sibagat) in the province of Agusan del Sur

Sampling and interview

Fieldwork was undertaken from March 2018 to May 2019. It consisted of obtaining free prior informed consents, observing rituals, acquiring resolutions, certifications, and permits, conducting semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, plant and field observations, and medicinal plant collections in selected barangays (villages) of Bayugan, Sibagat, and Esperanza (Fig. (Fig.1). 1 ). This study was initiated in coordination with the local government unit (LGU), NCIP-LGU, and Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) of Agusan del Sur. Consultation meetings and discussions were carried out together with the concerned parties (tribal leaders, tribal healers, and NCIP officers) to discuss research intent as purely academic and to acquire mutual agreement and respect to conduct this study. As approved, the research intent was certified through resolution and certification duly signed by the tribal council of elders following the by-laws of NCIP for the welfare and protection of indigenous peoples, and finally certified by NCIP-CARAGA.

Ethnopharmacological data were collected through semi-structured interviews with Manobo key informants through purposive and snowball sampling who were certified Agusan Manobo . A sampling of these key informants was coordinated with the provincial and local government administration together with the assistance of the tribal leaders and NCIP focal persons in every city or municipality to each of the barangays in selecting those who have knowledge of their medicinal plants and practices. The respective barangay tribal leaders assisted interviews among respondents with no appointments made prior to the visits. The semi-structured questionnaire used was modified and adapted from the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) template, as suggested by the Department of Health—Philippine Institute of Traditional and Alternative Health Care (DOH-PITAHC) (see Additional file 1 ). The Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School, University of Santo Tomas (USTGS-ERC), approved the study and the questionnaire used with a valid translation to Manobo dialect ( Minanubu ) with the help of a community member and NCIP officer. It has series of questions about the common health problems encountered by the respondents; the actions undertaken to address such problems; the medicinal plants they used (local or vernacular name); the plant’s part(s) used, forms, modes, quantity or dosage, and frequency of administration; the source or transfer of knowledge; and the experienced adverse or side effects. Interviews were accompanied by nurses and allied workers as coordinated by the rural health center to verify reported diseases accurately by the informants.

Meetings and focus group discussions were also performed to review the accuracy of acquired data among the respondents with the help of guided questions among the tribal council of elders comprising the NCIP-recognized indigenous peoples mandatory representatives (IPMRs), the tribal chieftains, the tribal healers, and the respective tribal leaders of every barangay tribal communities together with the NCIP officer.

Plant collection and identification

The collection of plant specimens was conducted through guided field walks with the aid of the traditional healers, expert plant gatherers, and members within the tribal community. The plant habit, habitat, morphological characteristics, vernacular names, and some indigenous terms of their uses were documented. Leaf samples were placed in zip-locked bags containing silica gel for molecular analysis [ 50 ] in preparation for further molecular confirmation. Voucher specimens were deposited in the University of Santo Tomas Herbarium (USTH). Putative plant identification using vernacular names was compared to the reference of local names, Dictionary of Philippines Plant Names by [ 51 ]. Plant identification was assisted by Mr. Danilo Tandang, a botanist and researcher at the National Museum of the Philippines. Specimens unidentifiable by morphology were selected for molecular confirmation. All scientific names were verified and checked for spelling and synonyms and family classification using The Plant List [ 52 ], World Flora Online [ 53 ], The International Plant Names Index [ 54 ], and Tropicos [ 55 ]. The occurrence, distribution, and species identification were further verified using the updated Co’s Digital Flora of the Philippines [ 56 ].

DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

Collected plant specimens with insufficient material for identification due to lack of reproductive parts and unfamiliarity were subjected to molecular confirmation. The total genomic DNA was extracted from the silica gel-dried leaf tissues of samples following the protocols of DNeasy Plant Minikit (Qiagen, Germany). The ITS (nrDNA), mat K, trn H- psb A, and trn L-F (cpDNA) markers were used for this study. Primer information and PCR conditions used for amplification using Biometra T-personal cycler (Germany) can be found in Table Table1 1 for future parameter reference. PCR amplicons were checked on a 1% TBE agarose to inspect for the presence and integrity of DNA. Amplified products were sent to Eurofins Genomics (Germany) for DNA sequencing reactions. Sequences were then assembled and edited using Codon Code Aligner v4.1.1. All sequences were then evaluated and compared using BLAST n search query available in the GenBank ( www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ). The BLAST n method estimates the reliability of species identification as a sequence similarity search program to determine the sequence of interest [ 62 ] regardless of the age, plant part, or environmental factors of the sample [ 63 ].

Gene regions, primers and amplification protocols used for polymerase chain reaction

| Gene region | Primer name | Reference | Primer sequence (5′ ➔ 3′) | PCR Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS (ITS1, 5.8S gene, and ITS2) | F | [ ] | 5′- -3′ | 94 °C 5 min; 28 cycles of 94 °C 1 min, 48 °C 1 min, 72 °C 1 min; 72 °C 7 min; 10 °C paused |

| S R | 5′- -3′ | |||

| [ ] | 5′- -3′ | 94 °C 5 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C 1 min, 55 °C 1 min, 72 °C 1 min, 45 s; 72 °C 10 min; 10 °C paused | ||

| 5′- -3′ | ||||

| K | F F | [ ] | 5′- -3′ | 98 °C 45 s; 35 cycles of 98 °C 10 s, 52 °C 30 s, 72 °C 40 s; 72 °C 10 min; 10 °C paused |

| R R | 5′- -3′ | |||

| A- H | A F | [ ] | 5′- -3′ | 95 °C 4 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C 30 s, 55 °C 1 min, 72 °C 1 min; 72 °C 10 min; 10 °C paused |

| H R | 5′- -3′ | |||

| L-F | [ ] | 5′- -3′ | 94 °C 3 min; 30 cycles of 93 °C 1 min; 55 °C 1 min, 72 °C 2 min; 10 °C paused | |

| 5′- -3′ |

Quantitative ethnopharmacological analysis

The use-report (UR) is counted as the number of times a medicinal plant is being used in a particular purpose in each of the categories [ 21 , 24 ]. Only one use-report was counted for every time a plant was cited as being used in a specific disease or purpose and even multiple disease or purpose under the same category [ 64 ]. Multiple use-reports were counted when at least two interviewees cited the same plant for the same disease or purpose. The use value (UV) developed by [ 45 ] is used to indicate species that are considered highly important by the given population using the following formula: UV = (ΣUi)/ N , where Ui is the number of UR or citations per species and N is the total number of informants [ 47 , 48 ]. High UV implies high plant use-reports relative to its importance to the community and vice versa. However, it does not determine whether the use of the plant is for single or multiple purposes [ 21 , 24 ]. The relative importance of the plants was also determined by calculating the cultural importance value (CIV) by using the formula: CIV = Σ[(ΣUR)/ N ], where UR is the number of use-reports in use category and N is the number of informants reporting the plant [ 48 ]. The use diversity (UD) of each medicinal plant used was determined using the Shannon index of uses as calculated with the R package vegan [ 65 ].

The ICF introduced by [ 66 ] was used to analyze the degree of informants’ agreement based on their medicinal plant knowledge in each of the categories [ 21 , 24 ]. This is computed using the formula: ICF = (Nur − Nt)/(Nur − 1), where Nur is the number of UR in each category, and Nt is the number of species used for a particular category by all informants. Fidelity level (FL) developed by [ 67 ] is calculated using the formula: FL (%) = (Ip/Iu) × 100, where Ip is the number of informants who independently suggested a given species for a particular disease, and Iu is the total number of informants who mentioned the plant for any use or purpose regardless of category. The maximum value (1.00) means a high degree of informant agreement showing the effectiveness of medicinal plants in each ailment category [ 68 ]. However, a minimum value (0.00) implies no information exchange among the informants [ 69 ]. Jaccard’s similarity index (JI) by [ 70 ] was calculated to evaluate the similarity of medicinal plant species among the three studied areas. The formula of JI is represented as follows: J = C /( A + B ), where A is the number of species found in habitat a, B is the number of species found in habitat b, and C is the number of common species found in habitats a and b. The number species present in either of the habitats is given by A + B (Jaccard).

Statistical tools

The plant URs were computed and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software v.23 [ 71 ]. Descriptive and non-parametric inferential statistics Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were employed to test for significant differences at 0.01 level of significance. These two statistical analyses measure and compare the medicinal plant use and knowledge of informants when grouped according to location, education, gender, social position, occupation, civil status, and age. The basic values and indices (UR, UC, UV, CIV, UD) were correlated using the Spearman correlation coefficient to compare variables that are not distributed normally.

Integrative molecular confirmation

Selected plant samples unidentifiable by morphology were subjected to an integrative molecular identification approach as previously recommended by [ 42 ] for accurate species identification of plant samples. Selected plant samples were compared with the available morphological characteristics, interview data on vernacular names and traditional knowledge, determining scientific names based on reference of local names using the Dictionary of Philippines Plant Names by [ 51 ], and utilizing multiple molecular markers, ITS (nrDNA), mat K, trn H- psb A, and trn L-F (cpDNA) for sequencing and BLAST matching. Two sequence similarity-based methods using BLAST [ 72 ] were applied for molecular confirmation. BLAST similarity-based identification was adapted from the study of [ 42 ] with a slight modification. This identification involved using the simple method taking the top hits and optimized approach. All successfully sequenced samples were sequentially queried using megablast [ 72 ] online at NCBI nucleotide BLAST against the nucleotide database. For the simple method, all top hits within a 5-point deviation down of the max score were considered. If the max score (− 5 points) showed only a single species, then a species level identification was assigned. On the other hand, if the max score (− 5 points) showed several species but similar genus, then a genus level identification was assigned. However, if the max score (− 5 points) showed multiple species in several genera of the same family, then a family level identification was assigned. In addition, within a 5-point deviation down of the max score, the highest max score and the highest percent identity were also determined. From the top 5 hits down of the max score, an optimized method using the formula, [max score (query cover/identity)], was calculated.

The integrative molecular confirmation combined the simple and optimized BLAST-based sequence matching results with reference of local names, and comparative morphology. As a result, all species identity and generic and familial affinity were further confirmed from the recorded occurrence and distribution of putative species in the study area based on the updated Co's Digital Flora of the Philippines [ 56 ].

Demography of Informants

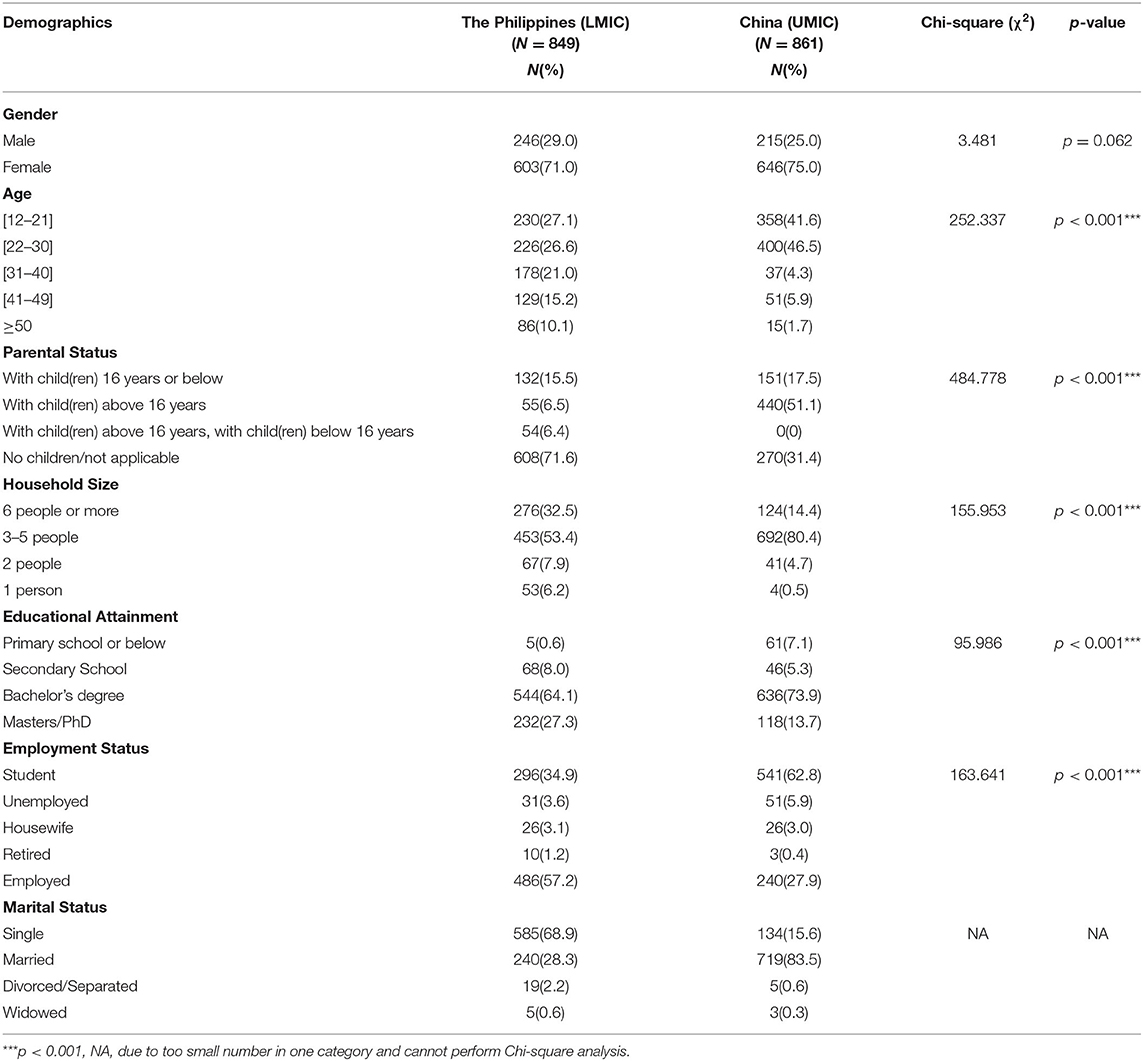

A total of 335 Agusan Manobo key informants (more than 10% of the total Manobo population of selected barangays) including traditional healers, leaders, council, and members were interviewed comprised with 106 female and 229 male individuals in an age range from 18–87 years old (median age of 42 years). We considered key informants those who are certified Agusan Manobo and knowledgeable with their medicinal plant uses and practices, may it be tribal officials, elders, and members of the community. Demographics by location, educational level, gender, social position, occupation, civil status, and age of participants are summarized in Table Table2 2 .

Sociodemographic profile of the Manobo key informants in Sibagat, Esperanza, and Bayugan City, Agusan del Sur

| Category | Subcategory | No. of informants | % of informants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Bayugan City | 150 | 44.8 |

| Sibagat | 90 | 26.9 | |

| Esperanza | 95 | 28.4 | |

| Education level | Primary | 57 | 17.0 |

| Secondary | 167 | 49.9 | |

| Higher education | 111 | 33.1 | |

| Gender | Male | 229 | 31.6 |

| Female | 106 | 68.4 | |

| Social Position | Tribal chieftain (Datu) | 45 | 13.4 |

| Tribal healer | 3 | 0.90 | |

| Tribal IPMR | 6 | 1.80 | |

| Tribal leader | 31 | 9.30 | |

| NCIP focal person | 4 | 1.20 | |

| council of elders | 7 | 2.10 | |

| members | 239 | 71.3 | |

| Occupation | Farming | 205 | 61.2 |

| Animal husbandry | 47 | 14.0 | |

| Employed | 49 | 14.6 | |

| Unemployed | 16 | 4.80 | |

| Others | 18 | 5.40 | |

| Civil Status | Single | 187 | 55.8 |

| Married | 133 | 39.7 | |

| Others | 15 | 4.50 | |

| Age | 18–34 years old | 142 | 42.4 |

| 35–49 years old | 103 | 30.7 | |

| 50–65 years old | 53 | 15.8 | |

| More than 65 years | 37 | 11.0 |

Medicinal plant knowledge of Agusan Manobo

The majority of the respondents (90.45%) cited their acquisition of medicinal plant knowledge from their parents. They also mentioned other sources of knowledge like fellow tribe band (67.76%), relatives (64.48%), community (61.49%), and through self-discovery (47.76%). However, the descriptive and inferential statistics revealed varying factors affecting the medicinal plant knowledge among the sampled key informants.

When grouped according to location, there was no significant difference on their medicinal plant knowledge as revealed in Kruskal-Wallis test ( p = 0.379) where the city of Bayugan had the highest number of UR (Md = 112, n = 150), followed by the two municipalities, Esperanza (Md = 111, n = 95) and Sibagat (Md = 108, n = 90). These results showed an exchange of information on these adjacent localities among the Manobo community might it be the council of elders and members who are medicinal plant gatherers, peddlers, and traders.

However, when grouped according to education, respondents who had secondary level as their highest educational attainment (Md = 116, n = 167) showed the topmost medicinal plant knowledge when compared to primary (Md = 105, n = 57) and tertiary (Md = 92, n = 111) as revealed by the highly significant difference presented in Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results implied that respondents who finished tertiary were more educated with modern medicine and highly acquainted with commercial drugs available over-the-counter for immediate treatment and therapy of their health problems. On the other hand, members with lower educational levels had more medicinal plant knowledge, and most traditional healers, gatherers, and peddlers finished at most on the secondary level.

When grouped according to gender, non-parametric tests revealed that men (Md = 116, n = 229) had more medicinal plant knowledge than women (Md = 104, n = 106), as demonstrated by the significant difference in both Mann-Whitney U test ( p < 0.001) and Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). It can be observed that men had more medicinal plant knowledge in Agusan Manobo culture, an observation supported by the fact that in two of the three selected localities, the tribal healers were males, and most of the tribal officials were also males. These results revealed contrary to the previous statistical findings of [ 21 ] in the Ati culture of Visayas where women were more knowledgeable than men because they were more involved in medicinal plant gathering and peddling, and women also played a big role in caring for their sick children.

Also, knowledge of the participants when grouped according to social position varied significantly, as revealed by the Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results showed that the tribal healers remained the most knowledgeable (Md = 189, n = 3), followed by the Manobo tribal officials (Md = 172, n = 93) with more medicinal plant knowledge when compared to other members of the community (Md = 104, n = 239). The medicinal plant knowledge also varied among the Manobo tribal officials, namely tribal leaders (Md = 178, n = 31), tribal IPMRs (Md = 177, n = 6), tribal chieftains (Md = 172, n = 45), Manobo tribal council of elders (Md = 164, n = 7), and Manobo NCIP focal persons (Md = 160, n = 4).

When grouped according to the occupation, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test also significantly revealed ( p < 0.001) that informants with occupation in farming (Md = 118, n = 205) and animal husbandry (Md = 116, n = 47) had more medicinal plant knowledge compared to employed (Md = 98, n = 49) and unemployed (Md = 96, n = 16) informants. These results suggested that Manobo people working in line with agriculture were more exposed to medicinal plant knowledge. They were farming crops or raising animals in hinterlands and mountainous areas where most medicinal plants were located. Also, when grouped according to civil status, married informants (Md = 136, n = 147) showed higher medicinal plant knowledge than single ones (Md = 92, n = 188) as revealed by the very high significant difference in both Mann-Whitney U test ( p < 0.001) and Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results implied that married respondents were more exposed during community gatherings, which involved discussions about medicinal plants with regard to their uses and applications. Exchange of information could be observed when couples were present during the scheduled tribal meetings.

Finally, when grouped according to age, descriptive and inferential statistics revealed that respondents from the age group of more than 65 years old had the highest medicinal plant knowledge (Md = 173, n = 37), followed by 50–65 years old (Md = 155, n = 53), 35–49 years old (Md = 102, n = 103), and 18–24 years old (Md = 96, n = 142), as revealed by the highly significant difference manifested in Kruskal-Wallis test ( p < 0.001). These results corresponded to our expectation because older informants most likely had more knowledge of medicinal plant uses and practices based on their long-term experience. These results may also imply that younger generations were becoming more acquainted and educated with modern therapeutic treatment making them more reluctant in their traditional medicinal plant practices like gathering and peddling. This transforming awareness, social, and cultural experiences could influence their medicinal plant interest, traditional knowledge, and attitudes among the Agusan Manobo . Younger generations are becoming more privileged to be educated as part of the government scholarship programs for indigenous communities resulting in migration to urban communities.

Medicinal plants used

A total of 122 reported medicinal plant species belonging to 108 genera and 51 families were classified in 16 use categories, as shown in Tables Tables3 3 and and4. 4 . All informants interviewed agreed about the healing power of medicinal plants, but only 58.5% of the informants use medicinal plants to treat their health conditions. While some respondents (30.75%) directly relied on seeking for tribal healers in their community, still all these Babaylans utilized their known medicinal plants for immediate treatment and therapy. The Agusan Manobo community believed that the combined healing gift and prayers of their Babaylans could increase the healing potential of their medicinal plants. However, the minority (10.75%) of the key informants depended on seeing a medical practitioner and allied health workers in the treatment of their health conditions at a nearby hospital or health center.

Use-reports (URs), use values (UVs), and informant consensus factors (ICFs) in every use category (UC).

| UC No. | UC names and abbreviations | Reported diseases or uses under each UC | No. of use-report | % of all use-reports | No. of species | % of all species | UV | ICF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diseases caused by bacterial, viral, and parasitic infections (BVP) | Ascariasis, chicken pox, herpes simplex, scabies, jaundice (hepatitis), mumps (parotitis), athlete's foot, warts, amoebiasis, white spot (tinea flava), impetigo, measles, colds (influenza), dengue fever, malaria, typhoid fever, ringworm | 3588 | 8.70 | 61 | 9.49 | 3.04 | 0.98 |

| 2 | Tissue growth problems (TGP) | Cancer, cyst, tumor (myoma) | 991 | 2.40 | 18 | 2.80 | 0.95 | 0.98 |

| 3 | Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic (ENM) | Diabetes, tonic, beriberi, hormonal imbalance, goiter | 1367 | 3.31 | 36 | 5.60 | 1.03 | 0.97 |

| 4 | Diseases of the nervous system (DNS) | Migraine, Parkinson's disease, nervous breakdown (depression, anxiety, mental stress, nervousness) | 239 | 0.58 | 7 | 1.09 | 0.19 | 0.97 |

| 5 | Diseases of the eye (EYE) | Sore eyes, cataract, eye problem (blurred vision, conjunctivitis, eye infection) | 308 | 0.75 | 8 | 1.24 | 0.25 | 0.98 |

| 6 | Diseases of the ear (EAR) | Ear congestion, ear infection, discharging ear (otorrhea) | 410 | 0.99 | 8 | 1.24 | 0.36 | 0.98 |

| 7 | Diseases of the circulatory system (DCS) | Anemia, hypertension, varicose veins, heart problem (enlargement), internal bleeding, hemorrhage | 1333 | 3.23 | 31 | 4.82 | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| 8 | Diseases of the respiratory system (DRS) | Asthma, pneumonia, emphysema, pulmonary tuberculosis, nasal congestion, lung nodule, cough, cough with phlegm, respiratory disease complex (rhinitis, tracheitis, bronchitis), sore throat (tonsillitis) | 3896 | 9.44 | 67 | 10.42 | 2.66 | 0.98 |

| 9 | Diseases of the digestive system (DDS) | Constipation, diarrhea, stomach trouble (dysentery, stomachache, bloating), vomiting (nausea), peptic ulcer, toothache, gum swelling, indigestion (dyspepsia), mouth sore (canker sore), stomach acidity (gastritis), swollen/bleeding gums (gingivitis), pancreatitis, liver problem (fatty liver), hemorrhoids, appetite enhancer | 6322 | 15.33 | 82 | 12.75 | 4.64 | 0.99 |

| 10 | Diseases of the skin (DOS) | Boils (furuncle/carbuncle), skin eruptions, skin rashes and itchiness (eczema, dermatitis), psoriasis, pimple and acne, hair loss, dandruff | 2563 | 6.21 | 40 | 6.22 | 2.10 | 0.99 |

| 11 | Musculoskeletal system and connective tissue problems (MCP) | Joint pain (arthritis, gout), rheumatism, sprain, tendon mass nodule, swollen muscles/swellings, muscle pain | 2597 | 6.30 | 42 | 6.53 | 2.23 | 0.98 |

| 12 | Genito-urinary problems (GUP) | Urination difficulty, kidney stones, kidney problem (high uric acid and creatinine), urinary bladder swelling, dysmenorrhea, delayed or irregular menstruation, urinary tract infection | 2358 | 5.72 | 39 | 6.07 | 1.72 | 0.98 |

| 13 | Uses in pregnancy to delivery, maternal and infant care (PMI) | Pregnancy (impotence and sterility), abortifacient, labor and delivery enhancer, childbirth tool, miscarriage, maternal care, postpartum care and recovery, new-born baby care, milk production enhancer | 1914 | 4.64 | 40 | 6.22 | 1.25 | 0.98 |

| 14 | Abnormal signs and symptoms (ASS) | Abdominal pain, backache, body ache, headache, fever, weakness and fatigue (asthenia), baby teething, child sleeplessness, malaise and fatigue, “pasmo” (cramp and spasm), “bughat” (relapse), skin numbness (paresthesia), dizziness and fainting, body chills, gas pain and flatulence, hangover | 8133 | 19.72 | 88 | 13.69 | 5.84 | 0.99 |

| 15 | Other problems of external causes (OEC) | Allergy, burns, cuts and wounds, fracture and dislocation, bruises and contusions, animal bites (snake, dog), insect bites (mosquito, wasp, scorpion), poisoning, contacts with plant or animal parts | 5023 | 12.18 | 70 | 10.89 | 3.98 | 0.99 |

| 16 | Other uses (OTU) | Circumcision antiseptic and anesthetic | 205 | 0.50 | 6 | 0.93 | 0.27 | 0.98 |

Medicinal plants used by the Agusan Manobo in Agusan del Sur, Philippines

| Plant no. | Scientific name | Family | Local name | Voucher no. | UR | UC | UV | CIV | UD | Disease or purpose | Parts used | Preparation and administration | Quantity or dosage | Administration frequency | Experienced adverse or side effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nees | Acanthaceae | White flower | USTH 015616 | 480 | 9 | 1.43 | 3.07 | 2.09 | Jaundice, colds, malaria; cancer; diabetes; hypertension, heart enlargement, atherosclerosis; cough, respiratory disease complex, sore throat; diarrhea, ulcer, dyspepsia, liver problem; abortifacient; fever, gas pain and flatulence | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | Can cause abortion in pregnant women |

| Boils, skin rashes and itchiness, dermatitis | Wh | E | Apply decoction as wash | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 2 | (L.) Kurz | Acanthaceae | Marvelosa or Serpentina | USTH 015622 | 583 | 6 | 1.74 | 2.90 | 1.74 | Colds; diabetes, beriberi; nervous breakdown; hypertension; diarrhea, stomachache; weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once a day for 3–5 days | None |

| 3 | L. | Amaranthaceae | Kudyapa | USTH 015589 | 211 | 9 | 0.63 | 2.75 | 2.06 | Diabetes; anemia; cough, bronchitis; dysentery, constipation; urinary tract infection; fever | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Labor and delivery enhancer | Sd | I | Drink water-infused powdered seeds | 1–3 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Boils, psoriasis, skin rashes, eczema, pimple, acne; snake and scorpion bite | Lf | E | Apply leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 4 | L. | Anacardiaceae | Mangga | USTH 015591 | 222 | 5 | 0.66 | 2.85 | 1.47 | Constipation | Fr | I | Eat fresh fruit directly | 1–3 fruits | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Cough, cough with phlegm, sore throat | Lf | I | Drink hot water-infused leaves or decoction | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Diarrhea, stomach trouble; headache | Bk | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Scabies; cuts and wounds | Bk, Lf | E | Rub crushed leaves or scraped bark | 3–5 leaves, 1 palm-sized bark | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 5 | (L.f.) Kurz | Anacardiaceae | Abihid | USTH 015599 | 372 | 4 | 1.11 | 2.33 | 1.39 | Colds; diabetes; cough; fever | Bk, Lf | I | Drink decoction of leaves and scraped bark | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day for 3 days or as needed | None |

| Colds; fever | Bk, Lf | E | Bath water-infused leaves and scraped bark | 1 pail | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 6 | L. | Annonaceae | Guyabano | USTH 015593 | 209 | 8 | 0.62 | 2.17 | 2.02 | Cancer; diabetes; hypertension; dysentery | Fr | I | Eat fresh fruit directly | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a week or as needed | In excess can cause blood viscosity |

| Ascariasis; cough; stomach trouble, stomach acidity; urination difficulty, urinary tract infection | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Skin eruptions, eczema | Lf, Sp | E | Apply leaf sap or crushed leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 7 | (Lam.) Hook.f. & Thomson | Annonaceae | Anangilan or Ilang-ilang | USTH 015577 | 358 | 7 | 1.07 | 2.47 | 1.85 | Colds; cough; stomach trouble, ulcer; fever, body chills | Bk, Lf | I | Drink decoction | 5–7 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Scabies, athlete's foot; pimple; rheumatism, swollen muscles or swellings, muscle pain; insect bites | Fl | E | Apply oil from steamed flowers | Completely on affected part | 3–5 times a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 8 | (Merr.) Steen. | Annonaceae | Talimughat taas | USTH 015558 | 198 | 3 | 0.59 | 2.08 | 0.90 | Muscle pain; labor and delivery enhancer, postpartum care and recovery; backache, body ache, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse | Bk, Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day up to 3 days or as needed | None |

| 9 | Elmer | Annonaceae | Bigo | USTH 015662 | 195 | 5 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 1.56 | Amoebiasis; hypertension; fever, weakness and fatigue | St | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Hair loss; insect bites | St, Sp | E | Apply stem sap | 1/2–1 cup | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 10 | Wall. ex G.Don | Apocynaceae | Dita | USTH 015546 | 386 | 9 | 1.15 | 2.71 | 2.04 | Tonic; ear congestion; cough; stomach trouble, toothache; urinary tract infection; abdominal pain, weakness and fatigue, hangover | Bk, Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Cuts and wounds, bruises and contusions, sprain | Lf | E | Apply crushed and heated leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Scabies, impetigo, ringworm; boils | Bk | E | Apply water-infused powdered bark | 1 glass | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Stomachache, snake bite | Bk | E | Drink local alcohol-tinctured bark | 1/2 to 1 glass | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 11 | (King & Gamble) D.J.Middleton | Apocynaceae | Lunas tag-uli | USTH 015639 | 1134 | 12 | 3.39 | 3.68 | 2.22 | Cancer; diabetes; ear infections; diarrhea, stomach trouble, ulcer, toothache; arthritis, rheumatism; pregnancy; body ache, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse; poisoning | Sp, St | I | Drink stem sap | 1–3 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Colon and prostate cancer, cyst, tumor; diabetes; hypertension; pulmonary tuberculosis; diarrhea, stomach trouble, ulcer, toothache, swollen gums; arthritis, rheumatism; impotence and sterility, postpartum care and recovery; body ache, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse, gas pain, and flatulence; sprain; poisoning | St | I | Drink local alcohol-tinctured or decocted stem | 1/2 to 1 glass | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Scabies, warts, impetigo, typhoid fever; boils, skin eruptions, skin rashes, and itchiness; arthritis, rheumatism, swellings, muscle pain; backache, body ache, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse gas pain and flatulence; allergy, burns, cuts and wounds, sprain, animal and insect bites, contacts with plants and animal parts | St | E | Apply coconut or Efficascent oil-infused stem | Completely on affected part | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 12 | Decne. | Apocynaceae | Pikot-pikot | USTH 015618 | 57 | 2 | 0.17 | 0.86 | 0.69 | Boils; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply coconut oil-infused burned and powdered leaves | Completely on affected part | As needed | None |

| 13 | Schott ex Van Houtte | Araceae | Lunas gabi | USTH 015614 | 44 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.60 | 0.00 | Allergy, cuts and wounds, snake and insect bite, poisoning | Lf, Sp, St | E | Apply stem or leaf sap | Completely on affected part | Once a day or as needed | None |

| 14 | Engl. ex Engl. & K.Krause | Araceae | Payaw | USTH 015597 | 466 | 7 | 1.39 | 2.00 | 1.83 | Colds; body ache, headache, fever | Lf, St | I/E | Sniff sliced and pounded leaf and stem or tie leaf and stem around the neck | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Tonsillitis; pregnancy, impotence and sterility, labor and delivery enhancer | Rz | I | Drink extracted juice from crushed rhizome | 1–3 cups | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Rheumatism; cuts and wounds | Rz | E | Apply extracted juice from crushed rhizome | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Hemorrhoids | Lf | E | Insert heated young leaf | 1 leaf | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 15 | L. | Araliaceae | Goto Kola | USTH 015563 | 263 | 4 | 0.78 | 1.78 | 1.39 | Diabetes; hypertension; fever | Lf | I | Eat fresh leaves directly or drink decocted leaves | 3–5 leaves; 1 cup | Once a day or as needed | In excess can cause anemia, dizziness and weakening |

| Cuts and wounds | Lf, Sp | E | Apply leaf sap or crushed leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 16 | L. | Arecaceae | Huling-huling | USTH 015610 | 42 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.69 | Breast cancer | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| 17 | Becc. | Arecaceae | Kapi | USTH 015608 | 168 | 4 | 0.50 | 1.65 | 1.28 | Hypertension; asthma; diarrhea, dyspepsia, gastritis, indigestion; arthritis, rheumatism | Rz | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None |

| 18 | (Planch. ex Rolfe) ined. | Aristolochiaceae | Salimbagat | USTH 015643 | 278 | 3 | 0.83 | 1.75 | 1.10 | Amoebiasis; cancer; toothache | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| 19 | (Schult.f.) Byng & Christenh. | Asparagaceae | Espada-espada | USTH 015647 | 78 | 2 | 0.23 | 0.67 | 0.69 | Boils; snake bite | Lf | E | Apply leaf sap or pounded leaves as poultice | 5–7 drops | As needed | None |

| 20 | (Turcz.) R.K.Jansen | Asteraceae | Lunas pilipo | USTH 015548 | 396 | 4 | 1.18 | 2.40 | 1.33 | Toothache; anesthetic | Fl | I | Apply fresh flower directly | 1–3 flowers | As needed | None |

| Skin rashes and itchiness, psoriasis; cuts and wounds; anesthetic | Fl, Lf | E | Apply crushed flower or leaves as poultice | 1–3 flowers, 5–7 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 21 | L. | Asteraceae | Albahaca | USTH 015602 | 77 | 3 | 0.23 | 1.89 | 1.10 | Abortifacient; weakness and fatigue | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 cups | Once a day or as needed | Can cause abortion in pregnant women |

| Cuts and wounds | E | Apply pounded leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | |||||||||||

| 22 | L. | Asteraceae | Helbas | USTH 015619 | 365 | 4 | 1.09 | 1.60 | 1.24 | Asthma, cough, cough with phlegm; diarrhea, dyspepsia; delayed menstruation; relapse | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | In excess can cause anemia, dizziness and weakening |

| Abdominal pain, body ache, fever, cramp, and spasm | Lf | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 23 | L. | Asteraceae | Tuway-tuway | USTH 015582 | 218 | 5 | 0.65 | 1.67 | 1.26 | Colds; diarrhea; muscle pain; backache, body ache, fever, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse, gas pain, and flatulence | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day up to 3 days or as needed | None |

| Cuts and wounds, animal and insect bites | Lf | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 24 | (L.) DC. | Asteraceae | Gabon | USTH 015573 | 412 | 6 | 1.23 | 2.60 | 1.58 | Hypertension; cough, cough with phlegm; urination difficulty; postpartum care and recovery; body ache, headache, fever, weakness and fatigue, gas pain and flatulence | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day for 3 days or as needed | None |

| Headache | Lf | E | Apply steamed or pounded leaves in the forehead | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Boils, skin rashes | Lf | E | Apply leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 25 | (L.) R.M.King & H.Rob. | Asteraceae | Hagonoy | USTH 015632 | 448 | 5 | 1.34 | 2.50 | 1.56 | Tumor; hemorrhage; fever | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day for 3 days or as needed | None |

| Boils; burns, cuts, and wounds | Lf | E | Apply leaf sap or crushed leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 26 | (L.) H.Rob. | Asteraceae | Kanding-kanding | USTH 015587 | 476 | 5 | 1.42 | 2.78 | 1.42 | Colds, malaria; pulmonary tuberculosis; dog bite | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Chicken pox, herpes simplex, measles; boils, skin eruptions, skin rashes and itchiness; weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm | Fl, Lf, Rt | E | Bath water-infused leaves and roots or burn leaves and roots as incense | 1 pail as bath or 1 bowl as incense | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 27 | (Link ex Spreng.) DC. | Asteraceae | Gapas-gapas bae | USTH 015666 | 208 | 3 | 0.62 | 2.25 | 1.01 | Stomachache, dyspepsia; body ache, headache, gas pain, and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Cuts and wounds | Lf, Sp | E | Apply sap or leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 28 | (Lour.) Merr. | Asteraceae | Ashitaba | USTH 015645 | 215 | 4 | 0.64 | 2.50 | 1.33 | Emphysema, cough; diarrhea, stomach trouble; kidney stones; abdominal pain | Lf | I | Drink brewed tea-prepared leaves or decoction | 3–5 cups | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| 29 | (Burm.f.) B.L.Rob. | Asteraceae | Moti-moti | USTH 015543 | 397 | 6 | 1.19 | 2.75 | 1.67 | Cough; ulcer | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None |

| Sore eyes | Lf, Sp | I | Drop leaf sap | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Skin rashes and itchiness; cuts and wounds, snake and scorpion bites; circumcision antiseptic | Lf | E | Apply leaf sap or crushed leaves as poultice | 5–7 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 30 | (Juss.) Rohr | Asteraceae | Kukog banog | USTH 015564 | 500 | 5 | 1.49 | 2.50 | 1.44 | Urination difficulty, kidney problem, urinary bladder swelling, delayed menstruation, urinary tract infection; fever, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm | Lf, Rt | I | Drink brewed tea-prepared leaves or decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Sore eyes; eczema, skin rashes, and itchiness; cuts and wounds, sprain, snake bite | Lf, Sp | E | Apply drops of leaf sap | Completely on affected part | Thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 31 | (Retz.) Sw. | Athyriaceae | Pako-pako | USTH 015545 | 212 | 5 | 0.63 | 1.92 | 1.56 | Colds; cough; diarrhea, dysentery; labor and delivery enhancer, postpartum care and recovery; body ache, headache, fever | Sh | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None |

| 32 | Warb. | Begoniaceae | Budag-budag | USTH 015654 | 85 | 2 | 0.25 | 1.33 | 0.64 | Pimple, dandruff; burns | Fl, Lf | E | Apply crushed flower and leaves as poultice | 1–3 flowers, 1–3 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 33 | (L.) Gaertn. | Bombacaceae | Doldol | USTH 015535 | 140 | 5 | 0.42 | 2.14 | 1.55 | Diabetes; pulmonary tuberculosis; diarrhea, dysentery; rheumatism, swollen muscles; snake bite | Bk, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 34 | Lam. | Boraginaceae | Alangitngit or Tsaang-Gubat | USTH 015638 | 336 | 4 | 1.00 | 2.60 | 1.39 | Diabetes; nervous breakdown; stomach acidity; food and drug allergy | Lf | I | Drink tea-prepared leaves | 1/2 to 1 cup | Once a day for 3 days or as needed | None |

| 35 | (L.) Merr. | Bromeliaceae | Pinya | USTH 015667 | 226 | 7 | 0.67 | 1.71 | 1.85 | Ascariasis, amoebiasis; cancer; diabetes; hypertension; constipation, stomach acidity | Fr | I | Eat fresh fruit directly | 1–3 slices | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Headache, fever, weakness, and fatigue | Lf, Sh | E | Apply crushed shoot or leaves as poultice | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Cancer; swellings | Lf | I/E | Drink decoction or apply decocted leaves | 3–5 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 36 | (L.) L.f. | Byttneriaceae | Samboligawn | USTH 015637 | 329 | 8 | 0.98 | 2.69 | 1.98 | Diabetes, tonic; bronchitis; stomachache; dysmenorrhea, irregular menstruation; sterility | Bk, Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Scabies; boils, skin eruptions, dermatitis; cuts and wounds | Bk, Lf | E | Apply decoction as wash | 1–3 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 37 | L. | Byttneriaceae | Bitan-ag | USTH 015631 | 146 | 6 | 0.44 | 2.50 | 1.70 | Tumor; asthma, pneumonia, cough; dyspepsia, liver problem; headache; baby teething | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Scabies; psoriasis | Lf | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 38 | (Houtt.) Stapf | Byttneriaceae | Banitlong | USTH 015649 | 265 | 4 | 0.79 | 1.76 | 1.24 | Rheumatism; backache, body ache, headache | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Canker sore; burns | Lf | E | Apply leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 39 | (L.) G.Don | Campanulaceae | Elepanteng puti | USTH 015583 | 213 | 5 | 0.64 | 1.83 | 1.56 | Toothache | Lf | I | Apply chewed or pounded leaves | 1–3 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Nervous breakdown; asthma, bronchitis; fever | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply decoction | 1 glass | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 40 | L. | Caricaceae | Kapayas laki | USTH 015668 | 659 | 6 | 1.97 | 2.92 | 1.64 | Constipation, dyspepsia; milk production enhancer | Fr | I | Eat fresh fruit directly | 1–3 slices | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Tonic; asthma; stomach problem | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Dengue fever | Lf, Sp | I | Drink leaf sap | 5–7 leaves | Thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Body ache, fever, cramp, and spasm | Lf | I | Apply crushed and heated leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 41 | (Jack) Blume | Clusiaceae/Guttiferae | Bansilay | USTH 015541 | 96 | 4 | 0.29 | 2.33 | 1.33 | Colds; cough; dysentery | Bk, Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Toothache | Lf | I | Apply chewed or pounded leaves | 3–5 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Impetigo; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply pounded leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 42 | (J.Koenig) Govaerts | Costaceae | Tambabasi or Tawasi | USTH 015578 | 744 | 8 | 2.22 | 2.58 | 2.03 | Diabetes, goiter; migraine; ear congestion; cough, lung nodule; urination difficulty, kidney problem; headache, fever | Lf, Rz | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day up to 3 days or as needed | None |

| Diarrhea, stomachache, dysentery | St | I | Drink stem sap | 1/2 cup | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Sore eyes | Lf | I | Apply leaf sap | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 43 | (Lam.) Pers. | Crassulaceae | Hanlilika | USTH 015584 | 486 | 12 | 1.45 | 2.88 | 2.21 | Diabetes; anemia, hypertension; asthma; cough; constipation, diarrhea, stomach trouble, hemorrhoids; kidney stone; labor and delivery enhancer; fever | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Herpes simplex; hemorrhoids; boils, eczema; swellings; burns, cuts and wounds, bruises and contusions, insect bites | Lf | I | Apply decocted leaves as wash | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Abdominal pain, body ache, headache, fever | Lf | E | Apply heated leaves as hot compress | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 44 | (L.) H.Pfeiff. | Cyperaceae | Busikad | USTH 015571 | 254 | 6 | 0.76 | 1.38 | 1.61 | Chicken pox, measles; cancer; cough; stomach acidity; fever, relapse, gas pain and flatulence; sprain | Wh | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Baby teething | Fl | I | Drink water-infused flower | 1/2–1 glass | Once to thrice a day | None | ||||||||||

| 45 | Oliv. | Dioscoreaceae | Banag | USTH 015537 | 540 | 6 | 1.61 | 2.36 | 1.70 | Myoma; migraine; arthritis, rheumatism; urination difficulty, urinary bladder swelling; postpartum care and recovery; headache, cramp and spasm, relapse | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day for 3 days or as needed | None |

| 46 | L. | Euphorbiaceae | Tawa-tawa | USTH 015665 | 305 | 7 | 0.91 | 2.80 | 1.85 | Colds, dengue fever; asthma; diarrhea, vomiting; fever | Wh | I | Drink decoction of whole plant except flowers | 5–7 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | In excess can cause thrombocytopenia |

| Ringworm; sore eyes; boils, skin rashes, and itchiness; cuts and wounds | Lf | I/E | Apply leaf sap or decocted leaves | 5–7 leaves | Thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 47 | L. | Euphorbiaceae | Tuba-tuba puti | USTH 015595 | 495 | 7 | 1.48 | 2.66 | 1.79 | Colds; pulmonary tuberculosis; diarrhea; arthritis, rheumatism; backache, body ache, fever, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse, gas pain, and flatulence | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Scabies, ringworm; ear infection, discharging ear; toothache; swollen muscles and swellings; cuts and wounds, fracture and dislocation, animal and insect bites | Bk, Rt | I/E | Apply decoction or pounded scraped bark as poultice | 1–3 palm-sized barks, 1/2–1 arm-sized roots | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 48 | L. | Euphorbiaceae | Tuba-tuba tapol | USTH 015586 | 810 | 9 | 2.41 | 2.83 | 1.94 | Colds, malaria, typhoid fever; pulmonary tuberculosis; diarrhea; arthritis, rheumatism; dysmenorrhea, irregular menstruation; backache, body ache, fever, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse, gas pain, and flatulence | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 leaves, 1/2–1 arm-sized roots | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Ringworm; boils, carbuncles, dermatitis; swollen muscles and swellings, muscle pain; backache, body ache, fever; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Bath or wash decocted leaves | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Scabies, ringworm; ear infection, discharging ear; toothache, mouth sore; cuts and wounds, fracture and dislocation, animal and insect bites | Bk, Rt | I/E | Apply decoction or pounded scraped bark as poultice | 1–3 palm-sized barks, 1/2–1 arm-sized roots | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 49 | (Reinw. ex Blume) Rchb. & Zoll. | Euphorbiaceae | Awom | USTH 015621 | 485 | 5 | 1.45 | 2.33 | 1.56 | Beriberi; emphysema, cough; diarrhea, stomach trouble | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Fibroma; body ache, weakness, and fatigue | Bk, Fl, Lf | E | Apply fresh or heated flower, leaves, and bark; sometimes mixed with little salt | 1–3 flowers, 1–3 leaves, 1–3 palm-sized barks | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 50.1 | Pax & Hoffm. | Euphorbiaceae | Banti puti | USTH 015633 | 202 | 3 | 0.60 | 1.77 | 1.04 | Impetigo; diarrhea, stomach trouble; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply pounded leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 50.2 | Pax & Hoffm. | Euphorbiaceae | Banti tapol | USTH 015554 | 203 | 3 | 0.61 | 1.60 | 1.04 | Impetigo; diarrhea, stomach trouble; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply pounded leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 51 | sp. | Fabaceae | Talimughat pikas | USTH 015575 | 284 | 4 | 0.85 | 1.50 | 1.22 | Rheumatism, muscle pain; delayed menstruation; labor and delivery enhancer, postpartum care and recovery; backache, body ache, weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm, relapse | Lf, St | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day up to 3 days or as needed | None |

| 52 | L. | Fabaceae | Sagay-sagay | USTH 015572 | 84 | 5 | 0.25 | 1.60 | 1.24 | Myoma; hormonal imbalance; cough; constipation; fever, weakness and fatigue, relapse | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day up to 3 days or as needed | None |

| 53 | (Jacq.) Kunth ex Steud | Fabaceae | Madre de Cacao | USTH 015620 | 153 | 6 | 0.46 | 1.83 | 1.68 | Scabies; boils, skin eruption, skin rashes, and itchiness; cuts and wounds | Lf, Sp | E | Apply leaf sap or pounded leaves as poultice | Completely on affected part | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Eczema, dermatitis; arthritis and rheumatism; burns, cuts and wounds, bruises and contusions | Bk, Rt, Sp | E | Apply sap or decocted bark or root | Completely on affected part | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Abortifacient, postpartum care, and recovery | Lf | E | Burn leaves as incense or apply heated leaves as hot compress | 3–5 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Body ache, headache, fever; fracture and dislocation, sprain | Bk | E | Apply scraped bark as poultice | 1–3 palm-sized barks | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 54 | L. | Fabaceae | Hibi-hibi or makahiya | USTH 015570 | 355 | 8 | 1.06 | 2.29 | 1.97 | Diabetes; hypertension; asthma, dysentery; urination difficulty; fever | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Baby teething | Rt | I | Drink water-infused peeled roots | 1/2 to 1 cup | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Mumps; boils; child sleeplessness, malaise, and fatigue | Sh | E | Apply hot water-infused shoots | 1/2 to 1 glass | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 55 | Baker | Fabaceae | Bahay | USTH 015625 | 522 | 5 | 1.56 | 2.36 | 1.56 | Atherosclerosis (high cholesterol) | Fr | I | Eat fresh fruit directly | 1–3 fruits | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Typhoid fever; nervous breakdown; high cholesterol; kidney problem; fever | Bk | I | Drink decoction or local alcohol-tinctured bark | 1/2 to 1 cup | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Nervousness; skin numbness | Bk, Rt | E | Apply Efficascent oil-infused bark and root | Fill a 250 ml glass bottle with bark and roots | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 56.1 | (Roxb.) Benth. | Fabaceae | Alibangbang puti | USTH 015646 | 66 | 1 | 0.20 | 1.11 | 0.00 | Internal bleeding, hemorrhage | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 56.2 | (Roxb.) Benth. | Fabaceae | Alibangbang tapol | USTH 015634 | 53 | 1 | 0.16 | 1.00 | 0.00 | Internal bleeding, hemorrhage | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 57 | R.Br. | Lamiaceae | Awoy | USTH 015661 | 378 | 4 | 1.13 | 1.50 | 1.28 | Ulcer, pancreatitis, fatty liver; weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm | Lf | I | Drink hot water-infused leaves | 1/2 to 1 cup | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Asthma | Lf | E | Burn leaves as incense | 1–3 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Swollen muscles, muscle pain; backache, body ache | Lf | E | Apply leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 58 | Lour. | Lamiaceae | Kalabo | USTH 015617 | 380 | 4 | 1.13 | 1.78 | 1.31 | Asthma, cough, cough with phlegm; dyspepsia; abdominal pain, gas pain, and flatulence | Lf | I | Eat leaves directly or drink decoction | 1/2 to 1 cup | Once to thrice a day or as needed | In excess can cause anemia, weakness, and allergy |

| Burns, bruised and contusions, insect bites | Lf | E | Apply water-infused leaves | 1–3 glasses | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 59.1 | (L.) Benth. | Lamiaceae | Mayana kanapkap | USTH 015567 | 260 | 5 | 0.78 | 1.67 | 1.47 | Anemia; asthma, pneumonia, cough; dyspepsia; gas pain and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once a day for 3–5 days or as needed | None |

| Cuts and wounds, bruises and contusions, sprain | Lf, Sp | E | Apply leaf sap or crushed leaves as poultice | 5–7 leaves | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 59.2 | (L.) Benth. | Lamiaceae | Mayana pula | USTH 015644 | 414 | 6 | 1.24 | 2.25 | 1.59 | Anemia; asthma, pneumonia, emphysema, pulmonary tuberculosis, cough; ulcer, dyspepsia; gas pain and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once a day for 3–5 days or as needed | None |

| Conjunctivitis | Lf | I | Apply decoction as drop | Completely on affected part | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Cuts and wounds, bruises and contusions, sprain | Lf | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 5–7 leaves | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 60 | Roxb. ex Sm. | Lamiaceae | Gmelina | USTH 015635 | 335 | 5 | 1.00 | 1.83 | 1.49 | Toothache, gum swelling | Lf | I | Apply chewed or pounded leaves | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None |

| Discharging ear | Fr | I | Drop extract of heated fruit | 1–3 fruits | As needed | Poisonous when eaten | ||||||||||

| Stomach bloating; maternal care; headache, gas pain and flatulence; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply leaves directly or as poultice | 1–3 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 61 | Jacq. | Lamiaceae | Sawan-sawan | USTH 015574 | 498 | 7 | 1.49 | 2.56 | 1.85 | Colds, malaria; cough; diarrhea, stomachache; new-born baby care; fever, gas pain and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink decoction or leaf sap | 3–5 glasses decoction or 1/2 cup leaf sap (adult); 1/2 cup decoction or 1 teaspoonful leaf sap (baby) | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Delayed menstruation | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Toothache; cuts and wounds | Lf | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 62 | L. | Lamiaceae | Herba buena | USTH 015669 | 174 | 6 | 0.52 | 2.71 | 1.59 | Measles; cough; diarrhea, dysentery; dysmenorrhea; headache, fever, cramp and spasm, gas pain and flatulence | Sh | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Asthma; dizziness and fainting | Lf | I | Sniff crushed leaves or leaves infused with hot water | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Toothache; headache, fever; insect bites | Lf | E | Apply chewed or crushed leaves | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 63 | L. | Lamiaceae | Sencia | USTH 015670 | 432 | 9 | 1.29 | 2.81 | 2.04 | Sinusitis, cough; stomachache, vomiting; delayed menstruation; backache, body ache, headache, fever, gas pain and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink hot water-infused leaves or decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Ringworm; ear infection and congestion; toothache | Lf | I/E | Apply leaf sap | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Muscle pain, abdominal pain; cuts and wounds, dislocation, snake bite | Lf | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | Completely on affected part | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Skin rashes and itchiness, acne; rheumatism; cuts and wounds; animal and insect bites | Lf | E | Apply decoction as wash | 5–7 leaves | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 64 | L. | Lamiaceae | Sangig | USTH 015630 | 385 | 9 | 1.15 | 2.33 | 2.09 | Cough, cough with phlegm; constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, hemorrhoids; delayed menstruation; postpartum care and recovery; headache, fever, gas pain and flatulence | Lf, Sh | I | Drink decoction or add in soup | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None |

| Ear congestion, infection, and discharge | Lf, Sp | I | Drop leaf sap | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Boils, skin rashes, and itchiness; arthritis, rheumatism; cuts and wounds, bruises and contusions | Lf | E | Apply decoction as wash | 3–5 leaves | Twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Toothache; cuts and wounds, snake bites | Lf, Sh | I/E | Apply crushed shoot or leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves, 1 shoot | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 65 | (Blume) Miq. | Lamiaceae | Wachichao | USTH 015550 | 513 | 6 | 1.53 | 2.96 | 1.58 | Diabetes; hypertension; diarrhea, stomachache; joint pain, gout, rheumatism; urination difficulty, kidney stones, kidney problem, urinary bladder swelling, prostate problem; labor and delivery enhancer | Fl, Lf | I | Drink brewed tea-prepared leaves or decoction of leaves and flower | 3–5 cups | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| 66 | Blanco | Lamiaceae | Abgaw | USTH 015559 | 668 | 7 | 1.99 | 2.94 | 1.79 | Colds; nasal congestion, sinusitis, cough, cough with phlegm; diarrhea, ulcer; rheumatism; postpartum care and recovery; weakness and fatigue, gas pain and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink water-infused leaves | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day for 3 days or as needed | None |

| Cuts and wounds | E | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | |||||||||||

| 67 | (Merr.) Bakh. | Lamiaceae | Kulipapa | USTH 015603 | 128 | 4 | 0.38 | 1.18 | 1.24 | Beriberi; muscle pain; labor and delivery; backache, body ache, cramp and spasm | Rt, St | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 68 | L. | Lamiaceae | Lagundi | USTH 015562 | 475 | 5 | 1.42 | 2.69 | 1.55 | Cough, cough with phlegm; ulcer; rheumatism; postpartum care and recovery; headache, gas pain and flatulence | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 1/4 glass (young leaf) or 1/2 glass (mature leaf) | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 69 | S.Vidal | Lauraceae | Kaningag | USTH 015585 | 908 | 8 | 2.71 | 3.22 | 1.93 | Amoebiasis; cancer; hypertension; cough; diarrhea, stomach trouble, ulcer, stomach acidity; kidney problem, urinary tract infection; weakness and fatigue, cramp and spasm | Bk, Br, Rt | I | Drink decoction or local alcohol-tinctured bark, stem and root | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None |

| Cuts and wounds | Bk, Br, Rt | E | Apply coconut oil-infused bark, stem and root | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 70 | (Jack) Hook.f. | Lauraceae | Loktob | USTH 015580 | 307 | 7 | 0.92 | 2.83 | 1.79 | Mumps; cyst, tumor, myoma; goiter; asthma, pneumonia, emphysema, cough; ulcer; arthritis; kidney problem, dysmenorrhea | Bk, Rt | I | Drink hot water-infused bark or decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once a day in thrice a week for 2 months or as needed | In excess can cause anemia, dizziness and weakening |

| 71 | Merr. | Lauraceae | Efficascent | USTH 015576 | 82 | 2 | 0.24 | 1.11 | 0.69 | Cough; weakness and fatigue | Sp, St | I | Drink sap from rubbed stem | 1/2 cup | Once a day or as needed | None |

| 72 | (L.) Pers. | Lythraceae | Banaba | USTH 015596 | 384 | 4 | 1.15 | 2.57 | 1.26 | Ulcer; urination difficulty, kidney stones, high uric acid, and creatinine; maternal care; backache, body ache, fever | Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 73 | L. | Malvaceae | Gapas | USTH 015553 | 283 | 3 | 0.84 | 2.14 | 0.95 | Hemorrhage; postpartum care and recovery; body ache, fever, body chills | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 1 glass | Once a day for 3 days | In excess, can cause abnormalities in lactating mothers |

| 74 | L. | Malvaceae | Eskuba laki | USTH 015601 | 768 | 8 | 2.29 | 2.55 | 1.87 | Cough; stomach trouble; kidney stone, kidney problem, prostate problem, irregular menstruation | Lf, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Chicken pox, herpes simplex, scabies; boils; swellings; backache, body ache, headache; cuts and wounds | Lf, Rt | E | Apply leaves as poultice or leaf and bark decoction as wash | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Fever | Bk | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 palm-sized barks | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 75 | L. | Malvaceae | Dupang bae | USTH 015664 | 482 | 7 | 1.44 | 2.06 | 1.80 | Stomach trouble; arthritis, rheumatism; labor and delivery, postpartum care and recovery; fever; cuts and wounds, fracture and dislocation, bruises and contusion, sprain, animal bites | Wh | I/E | Drink or apply decoction or burn as incense | 1 bowl | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Diabetes; sore throat; toothache; abdominal pain | Sh | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 76 | Sw. | Marattiaceae | Amampang | USTH 015658 | 126 | 3 | 0.38 | 1.50 | 0.87 | Muscle pain; postpartum care and recovery; backache, body ache, weakness, and fatigue, cramp and spasm | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once to thrice a day or as needed | None |

| 77 | Miq. | Melastomataceae | Tampion | USTH 015581 | 282 | 3 | 0.84 | 1.25 | 1.04 | Swollen muscles and swellings, muscle pain; gas pain and flatulence; sprain | Lf | E | Apply heated leaves as hot compress | 1–3 leaves | Once a day or as needed | None |

| 78 | L. | Melastomataceae | Hantutuknaw puti | USTH 015588 | 274 | 3 | 0.82 | 1.89 | 0.96 | Diarrhea, dysentery, stomachache, hemorrhoids; headache, fever | Sh | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Toothache; cuts and wounds | Lf | I/E | Drop or drink stem sap | 1–3 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 79 | Correa | Meliaceae | Lansones | USTH 015565 | 103 | 4 | 0.31 | 1.52 | 1.28 | Malaria; diarrhea, dysentery, dyspepsia; fever, gas pain and flatulence | Bk, Lf | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Twice a day or as needed | None |

| Insect bites | Bk | E | Apply powdered bark | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| 80 | (Burm.f.) Merr. | Meliaceae | Santol | USTH 015624 | 464 | 7 | 1.39 | 1.78 | 1.85 | Tonic; hypertension; diarrhea, dysentery; postpartum care and recovery; abdominal pain, fever | Bk, Fr, Lf | I | Drink decoction of mesocarp, leaves and scraped bark | 3–5 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None |

| Toothache | Lf | I | Apply crushed leaves as poultice | 1–3 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Boils, skin rashes and itchiness, dermatitis | Lf | E | Apply decoction as wash | 3–5 leaves | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Ringworm | Bk | E | Apply pounded scraped bark as poultice | 1–3 palm-sized barks | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 81 | (L.) Jacq. | Meliaceae | Mahogany | USTH 015671 | 334 | 9 | 1.00 | 2.29 | 2.14 | Dysmenorrhea, delayed menstruation; abortifacient; abdominal pain | Sd | I | Take powdered seed or drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once a day or as needed | Can cause abortion in pregnant women |

| Amoebiasis, malaria; cancer; tonic; hypertension; cough; diarrhea; miscarriage; fever | Bk | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 82 | (L.) Merr. | Menispermaceae | Lagtang or Abutra | USTH 015600 | 922 | 10 | 2.75 | 3.23 | 2.14 | Jaundice; tumor, myoma; diabetes, tonic; respiratory disease complex; diarrhea, dysentery, dyspepsia, ulcer, appetite enhancer; dysmenorrhea, delayed menstruation; abortifacient; fever | Rt, St | I | Drink decoction | 3–5 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | Can cause abortion in pregnant women |

| Scabies; boils, skin rashes and itchiness; cuts and wounds | Rt, St | E | Apply coconut oil-infused stem | Completely on affected part | Once or twice a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| 83 | (L.) Hook. f. & Thomson | Menispermaceae | Panyawan | USTH 015566 | 782 | 9 | 2.33 | 2.68 | 1.95 | Malaria; tonic; diarrhea, stomach trouble, vomiting, ulcer, toothache; arthritis, rheumatism; dysmenorrhea; abortifacient; abdominal pain, backache, body ache, fever | St | I | Drink local alcohol-tinctured or decocted stem | 1–3 glasses | Once or twice a day or as needed | Can cause abortion in pregnant women |

| Scabies; sore eyes; cuts and wounds | Sp, St | E | Drop stem sap | Completely on affected part | As needed | None | ||||||||||

| Arthritis, rheumatism; abortifacient; abdominal pain, body ache; gas pain and flatulence | St | E | Apply coconut oil-infused stem or stem mixed with gasoline | Completely on affected part | As needed | Can cause abortion in pregnant women | ||||||||||

| 84 | Miq | Moraceae | Kabiya | USTH 015672 | 53 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.96 | 0.00 | Headache, fever | Rt | I | Drink decoction | 1 arm-sized root | Twice a day or as needed | None |

| 85 | Elmer | Moraceae | Tobog tapol | USTH 015551 | 492 | 8 | 1.47 | 3.00 | 1.89 | Colds; diabetes; hypertension; asthma, cough, respiratory disease complex; diarrhea, stomachache; urinary tract infection; postpartum recovery, maternal care, milk production enhancer; weakness and fatigue, relapse | Bk, Rt | I | Drink decoction | 1–3 glasses | Thrice a day or as needed | None |

| Diabetes; hypertension | Fr | I | Eat fresh fruit directly | 1–3 fruits | Once a day or as needed | None | ||||||||||

| Body ache, headache, fever | Lf | E | Apply leaves as poultice | 3–5 leaves | As needed | None | ||||||||||