Rewiring the classroom: How the COVID-19 pandemic transformed K-12 education

Subscribe to the brown center on education policy newsletter, brian a. jacob and brian a. jacob walter h. annenberg professor of education policy; professor of economics, and professor of education - university of michigan, former brookings expert cristina stanojevich cs cristina stanojevich doctoral student - michigan state university.

August 26, 2024

- The pandemic changed K-12 classrooms through new technologies, instructional practices, and parent-teacher communications, along with an emphasis on social-emotional learning.

- Less tangibly, COVID-19 might have shifted perceptions of the value and purposes of K-12 schooling.

- The durability and effects of these changes remain unclear and will depend on how educational leaders and policymakers manage them.

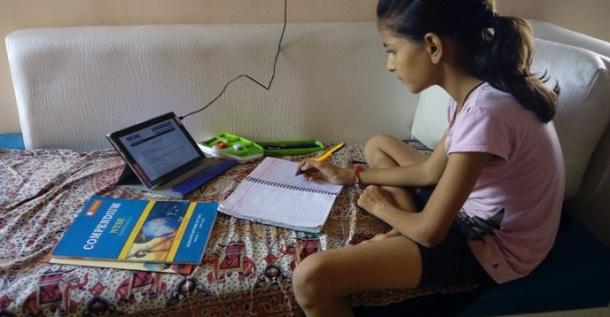

In March 2020, virtually all public school districts in the U.S. shut their doors. For the next 18 months, schooling looked like it never had before. Homes became makeshift classrooms; parents became de facto teachers. But by fall 2022, many aspects of K-12 education had returned to “normal.” Schools resumed in-person classes, extracurricular activities flourished, and mask mandates faded.

But did schools really return to what they were before the COVID-19 pandemic? Our research suggests not. We interviewed teachers, school leaders, and district administrators across 12 districts in two states, and then we surveyed a nationally representative set of veteran educators in May 2023. We found that the COVID-19 pandemic transformed K-12 education in fundamental ways.

Below, we describe how the pandemic reshaped the educational landscape in these ways and we consider the opportunities and challenges these changes present for students, educators, and policymakers.

Accelerated adoption of technology

One of the most immediate and visible changes brought about by the pandemic was the rapid integration of technology into the classroom. Before COVID-19, many schools were easing into the digital age. The switch to remote learning in March 2020 forced schools to fully embrace Learning Management Systems (LMS), Zoom, and educational software almost overnight.

When students returned to in-person classrooms, the reliance on these digital tools persisted. Over 70% of teachers in our survey report that students are now assigned their own personal device (over 80% for secondary schools). LMS platforms like Google Classroom and Schoology remain essential in many schools. An assistant superintendent of a middle-income district remarked, “Google Classroom has become a mainstay for many teachers, especially middle school [and] high school.”

The platforms serve as hubs for posting assignments, accessing educational content, and enabling communication between teachers, students, and parents. They have become popular among parents as well. One teacher, who has school-age children herself, noted :

“Whereas pre-COVID…you’re hoping and praying your kids bring home information…[now] I can go on Google classroom and be like, ‘Oh, it says you worked on Mesopotamia today. What was that lesson about?’”

Transformed instructional practices

The pandemic’s impact on student learning was profound. Reading and math scores dropped precipitously, and the gap widened between more and less advantaged students. Many schools responded by adjusting their schedules or adopting new programs. Several mentioned adopting “What I need” (WIN) or “Power” blocks to accommodate diverse learning needs. During these blocks, teachers provide individualized support to students while others work on independent practice or extension activities.

Teachers report placing greater emphasis on small-group instruction and personalized learning. They spend less time on whole-class lecture and rely more on educational software (e.g., Lexia for reading and Zearn for math) to tailor instruction to individual student needs. A third-grade teacher in a low-income district explained:

“The kids are in so many different places, Lexia is very prescriptive and diagnostic, so it will give the kids specifically what level and what skills they need. [I] have a student who’s working on Greek and Latin roots, and then I have another kid who’s working on short vowel sounds. [It’s] much easier for them to get it through Lexia than me trying to get, you know, 18 different reading lessons.”

Teachers aren’t just using technology to personalize instruction. Having spent months gaining expertise with educational software, more teachers find it natural to integrate those programs into their classrooms today. Those teachers who used ed tech before report doing so even more now. They describe using software like Flowcabulary and Prodigy to make learning more engaging, and games such as Kahoot to give students practice with various skills. Products like Nearpod let them create presentations that integrate instruction with formative assessment. Other products, like Edpuzzle, help teachers monitor student progress.

Some teachers discovered how to use digital tools to save time and improve their communications to students. One elementary teacher, for example, explains even when her students complete an assignment by hand, she has them take a picture of it and upload it to her LMS:

“I can sort them, and I can comment on them really fast. So it’s made feedback better. [I have] essentially a portfolio of all their math, rather than like a hard copy that they could lose…We can give verbal feedback. I could just hit the mic and say, ‘Hey, double check number 6, your fraction is in fifths, it needs to be in tenths.’”

Increased emphasis on social-emotional learning

The pandemic also revealed and exacerbated the social-emotional challenges that students face. In our survey, nearly 40% of teachers report many more students struggling with depression and anxiety than before the COVID-19 pandemic; over 80% report having at least a few more students struggling.

These student challenges have changed teachers’ work. When comparing how they spend class time now versus before the pandemic, most teachers report spending more time on activities relating to students’ social-emotional well-being (73%), more time addressing behavioral issues (70%), and more time getting students caught up and reviewing routines and procedures (60%).

In response, schools have invested in social-emotional learning (SEL) programs and hired additional counselors and social workers. Some districts turned to online platforms such as Class Catalyst and CloseGap that allow students to anonymously report their emotional state on a daily basis, which helps school staff track students’ mental health.

Teachers also have been adapting their expectations of students. Many report assigning less homework and providing students more flexibility to turn in assignments late and retake exams.

Facilitated virtual communication between parents and teachers

The pandemic also radically reshaped parent-teacher communications. Mirroring trends across society, videoconferencing has become a go-to option. Schools use videoconferencing for regular parent-teacher conferences, along with meetings to discuss special education placements and disciplinary incidents. In our national survey, roughly one-half of teachers indicate that they conduct a substantial fraction of parent-teacher conferences online; nearly a quarter of teachers report that most of their interactions with parents are virtual.

In our interviews, teachers and parents gushed about the convenience afforded by videoconferencing, and some administrators believe it has increased overall parent participation. (One administrator observed, “Our attendance rates [at parent-teacher conferences] and interaction with parents went through the roof.”)

An administrator from a low-income district shared the benefits of virtual Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings:

“It’s rare that we have a face-to-face meeting…everything is Docusigned now. Parents love it because I can have a parent that’s working—a single mom that’s working full time—that can step out during her lunch break…[and] still interact with everybody.”

During the pandemic, many districts purchased a technology called Remind that allows teachers to use their personal smartphones to text with parents while blocking their actual phone number. We heard that teachers continue to text with parents, citing the benefits for quick check-ins or questions. Remind and many LMS also have translation capabilities that makes it easier for teachers and parents to overcome language barriers.

Moving forward

The changes described above have the potential to improve student learning and increase educational equity. They also carry risks. On the one hand, the growing use of digital tools to differentiate instruction may close achievement gaps, and the ubiquity of video conferencing could allow working parents to better engage with school staff. On the other hand, the overreliance on digital tools could harm students’ fine motor skills (one teacher remarked, “[T]heir handwriting sucks compared to how it used to be”) and undermine student engagement. Some new research suggests that relying on digital platforms might impede learning relative to the old-fashioned “paper and pencil” approach. And regarding virtual conferences, the superintendent of a small, rural district told us, “There’s a disconnect when we do that…No, I want the parents back in our buildings, I want people back. We’re [the school] a community center.”

Of course, some of the changes we observed may not persist. For example, fewer teachers may rely on digital tools to tailor instruction once the “COVID cohorts” have aged out of the system. As the emotional scars of the pandemic fade, schools may choose to devote fewer resources to SEL programming. It’s important to note, too, that many of the changes we found come from the adoption of new technology, and the technology available to educators will continue to evolve (e.g., with the integration of new AI technologies into personalized tutoring systems). That being said, now that educators have access to more instructional technology and—perhaps more importantly—greater familiarity with using such tools, they might continue to rely on them.

The changes brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic provide a unique opportunity to rethink and improve the structure of K-12 education. While the integration of technology and the focus on social-emotional learning offer promising avenues for enhancing student outcomes, they also require continuous evaluation. Indeed, these changes raise some questions beyond simple cost-benefit calculations. For example, the heightened role of ed tech raises questions about the proper role of the private sector in public education. As teachers increasingly “outsource” the job of instruction to software products, what might be lost?

Educational leaders and policymakers must ensure that these pandemic-inspired changes positively impact learning and address the evolving needs of students and teachers. As we navigate this new educational landscape, the lessons learned from this unprecedented time can serve as a guide for building a more resilient, equitable, and effective educational system for the future.

Beyond technological changes, COVID-19 shifted perspectives about K-12 schooling. A middle-school principal described a new mentality among teachers in her district, “I think we have all become more readily able to adapt…we’ve all learned to assess what we have in front of us and make the adjustments we need to ensure that students are successful.” And a district administrator emphasized how the pandemic highlighted the vital role played by schools:

“…we saw that when students were not in school. From a micro and macro level, the environment that a school creates to support you growing up…we realized how needed this network is…both academically and socially, in growing our citizens up to be productive in the world. And we are happy to have everyone back.”

At the end of the day, this realization may be one of the pandemic’s most enduring legacies.

Related Content

Monica Bhatt, Jonathan Guryan, Jens Ludwig

June 3, 2024

Douglas N. Harris

August 29, 2023

September 27, 2017

Education Access & Equity Education Policy Education Technology K-12 Education

Governance Studies

U.S. States and Territories

Brown Center on Education Policy

Spelman College, Atlanta Georgia

7:00 pm - 12:30 pm EDT

Nicol Turner Lee

August 8, 2024

Online Only

10:00 am - 12:30 pm EDT

Guidance on distance learning

School closures were mandated as part of public health efforts to contain the spread of COVID-19 from February 2020 in most countries. Education systems around the world are facing an unprecedented challenge. Governmental agencies are working with international organizations, private sector partners and civil society to deliver education remotely through a mix of technologies in order to ensure continuity of curriculum-based study and learning for all.

Supporting distance learning during COVID-19

UNESCO has been working to mitigate the impact of education disruption and school closures. In response to the pandemic, UNESCO has produced various distance learning resources to support teachers and policy-makers. The following resources offer best practices, innovative ideas and practical information.

UNESCO is supporting the organization of several workshops based on the publication Ensuring effective distance learning during COVID-19 disruption: guidance for teachers following a call for proposals that attracted almost 200 entries. The first workshop was held online on 20-21 October 2021, sponsored by the Faculty of Specific Education at Alexandria University in Egypt. Organized by Prof. Mona Sharaf Abdelgalil, the session was attended by 211 teachers from different educational departments, including 80% female teachers. The second set of workshops (six in-person, and one hybrid) took place in Zimbabwe from 5 to 24 November 2021, organized by Learning Factory and Mr Addi Mavengere. These workshops reached a total of 95 participants, including 67% female teachers, 64% from rural communities, and 1% with physical impairment. Six other pilot workshops were held in-person in Ethiopia by Mr Inku Fasil, targeting 120 teachers in Bahirdar, Addis Ababa and Adama from 13 November to 2 December 2021.

Case studies

10 recommendations to plan distance learning solutions.

Decide on the use high-technology and low-technology solutions based on the reliability of local power supplies, internet connectivity, and digital skills of teachers and students. This could range through integrated digital learning platforms, video lessons, MOOCs, to broadcasting through radios and TVs.

Implement measures to ensure that students including those with disabilities or from low-income backgrounds have access to distance learning programmes, if only a limited number of them have access to digital devices. Consider temporarily decentralizing such devices from computer labs to families and support them with internet connectivity.

Assess data security when uploading data or educational resources to web spaces, as well as when sharing them with other organizations or individuals. Ensure that the use of applications and platforms does not violate students’ data privacy.

Mobilize available tools to connect schools, parents, teachers and students with each other. Create communities to ensure regular human interactions, enable social caring measures, and address possible psychosocial challenges that students may face when they are isolated.

Organize discussions with stakeholders to examine the possible duration of school closures and decide whether the distance learning programme should focus on teaching new knowledge or enhance students’ knowledge of prior lessons. Plan the schedule depending on the situation of the affected zones, level of studies, needs of students needs, and availability of parents. Choose the appropriate learning methodologies based on the status of school closures and home-based quarantines. Avoid learning methodologies that require face-to-face communication.

Organize brief training or orientation sessions for teachers and parents as well, if monitoring and facilitation are needed. Help teachers to prepare the basic settings such as solutions to the use of internet data if they are required to provide live streaming of lessons.

Blend tools or media that are available for most students, both for synchronous communication and lessons, and for asynchronous learning. Avoid overloading students and parents by asking them to download and test too many applications or platforms.

Define the rules with parents and students on distance learning. Design formative questions, tests, or exercises to monitor closely students’ learning process. Try to use tools to support submission of students’ feedback and avoid overloading parents by requesting them to scan and send students’ feedback.

Keep a coherent timing according to the level of the students’ self-regulation and metacognitive abilities especially for livestreaming classes. Preferably, the unit for primary school students should not be more than 20 minutes, and no longer than 40 minutes for secondary school students.

Create communities of teachers, parents and school managers to address sense of loneliness or helplessness, facilitate sharing of experience and discussion on coping strategies when facing learning difficulties.

National distance learning platforms and tools

A collection of national learning platforms and tools from Member States to facilitate the search for resources in one place.

Related items

- Information and communication

Remote Learning During COVID-19: Lessons from Today, Principles for Tomorrow

"Remote Learning During the Global School Lockdown: Multi-Country Lessons” and “Remote Learning During COVID-19: Lessons from Today, Principles for Tomorrow"

WHY A TWIN REPORT ON THE IMPACT OF COVID IN EDUCATION?

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted education in over 150 countries and affected 1.6 billion students. In response, many countries implemented some form of remote learning. The education response during the early phase of COVID-19 focused on implementing remote learning modalities as an emergency response. These were intended to reach all students but were not always successful. As the pandemic has evolved, so too have education responses. Schools are now partially or fully open in many jurisdictions.

A complete understanding of the short-, medium- and long-term implications of this crisis is still forming. The twin reports analyze how this crisis has amplified inequalities and also document a unique opportunity to reimagine the traditional model of school-based learning.

The reports were developed at different times during the pandemic and are complementary:

The first one follows a qualitative research approach to document the opinions of education experts regarding the effectiveness of remote and remedial learning programs implemented across 17 countries. DOWNLOAD THE FULL REPORT

WHAT ARE THE LESSONS LEARNED OF THE TWIN REPORTS?

- Availability of technology is a necessary but not sufficient condition for effective remote learning: EdTech has been key to keep learning despite the school lockdown, opening new opportunities for delivering education at a scale. However, the impact of technology on education remains a challenge.

- Teachers are more critical than ever: Regardless of the learning modality and available technology, teachers play a critical role. Regular and effective pre-service and on-going teacher professional development is key. Support to develop digital and pedagogical tools to teach effectively both in remote and in-person settings.

- Education is an intense human interaction endeavor: For remote learning to be successful it needs to allow for meaningful two-way interaction between students and their teachers; such interactions can be enabled by using the most appropriate technology for the local context.

- Parents as key partners of teachers: Parent’s involvement has played an equalizing role mitigating some of the limitations of remote learning. As countries transition to a more consistently blended learning model, it is necessary to prioritize strategies that provide guidance to parents and equip them with the tools required to help them support students.

- Leverage on a dynamic ecosystem of collaboration: Ministries of Education need to work in close coordination with other entities working in education (multi-lateral, public, private, academic) to effectively orchestrate different players and to secure the quality of the overall learning experience.

- FULL REPORT

- Interactive document

- Understanding the Effectiveness of Remote and Remedial Learning Programs: Two New Reports

- Understanding the Perceived Effectiveness of Remote Learning Solutions: Lessons from 18 Countries

- Five lessons from remote learning during COVID-19

- Launch of the Twin Reports on Remote Learning during COVID-19: Lessons for today, principles for tomorrow

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

MINI REVIEW article

Distance learning in higher education during covid-19.

- 1 Department of Pedagogy of Higher Education, Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University, Kazan, Russia

- 2 Department of Jurisprudence, Bauman Moscow State Technical University, Moscow, Russia

- 3 Department of English for Professional Communication, Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, Moscow, Russia

- 4 Department of Foreign Languages, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia

- 5 Department of Medical and Social Assessment, Emergency, and Ambulatory Therapy, I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), Moscow, Russia

COVID-19’s pandemic has hastened the expansion of online learning across all levels of education. Countries have pushed to expand their use of distant education and make it mandatory in view of the danger of being unable to resume face-to-face education. The most frequently reported disadvantages are technological challenges and the resulting inability to open the system. Prior to the pandemic, interest in distance learning was burgeoning, as it was a unique style of instruction. The mini-review aims to ascertain students’ attitudes about distant learning during COVID-19. To accomplish the objective, articles were retrieved from the ERIC database. We utilize the search phrases “Distance learning” AND “University” AND “COVID.” We compiled a list of 139 articles. We chose papers with “full text” and “peer reviewed only” sections. Following the exclusion, 58 articles persisted. Then, using content analysis, publications relating to students’ perspectives on distance learning were identified. There were 27 articles in the final list. Students’ perspectives on distant education are classified into four categories: perception and attitudes, advantages of distance learning, disadvantages of distance learning, and challenges for distance learning. In all studies, due of pandemic constraints, online data gathering methods were selected. Surveys and questionnaires were utilized as data collection tools. When students are asked to compare face-to-face and online learning techniques, they assert that online learning has the potential to compensate for any limitations caused by pandemic conditions. Students’ perspectives and degrees of satisfaction range widely, from good to negative. Distance learning is advantageous since it allows for learning at any time and from any location. Distance education benefits both accomplishment and learning. Staying at home is safer and less stressful for students during pandemics. Distance education contributes to a variety of physical and psychological health concerns, including fear, anxiety, stress, and attention problems. Many schools lack enough infrastructure as a result of the pandemic’s rapid transition to online schooling. Future researchers can study what kind of online education methods could be used to eliminate student concerns.

Introduction

The pandemic of COVID-19 has accelerated the spread of online learning at all stages of education, from kindergarten to higher education. Prior to the epidemic, several colleges offered online education. However, as a result of the epidemic, several governments discontinued face-to-face schooling in favor of compulsory distance education.

The COVID-19 problem had a detrimental effect on the world’s educational system. As a result, educational institutions around the world developed a new technique for delivering instructional programs ( Graham et al., 2020 ; Akhmadieva et al., 2021 ; Gaba et al., 2021 ; Insorio and Macandog, 2022 ; Tal et al., 2022 ). Distance education has been the sole choice in the majority of countries throughout this period, and these countries have sought to increase their use of distance education and make it mandatory in light of the risk of not being able to restart face-to-face schooling ( Falode et al., 2020 ; Gonçalves et al., 2020 ; Tugun et al., 2020 ; Altun et al., 2021 ; Valeeva and Kalimullin, 2021 ; Zagkos et al., 2022 ).

What Is Distance Learning

Britannica defines distance learning as “form of education in which the main elements include physical separation of teachers and students during instruction and the use of various technologies to facilitate student-teacher and student-student communication” ( Simonson and Berg, 2016 ). The subject of distant learning has been studied extensively in the fields of pedagogics and psychology for quite some time ( Palatovska et al., 2021 ).

The primary distinction is that early in the history of distant education, the majority of interactions between professors and students were asynchronous. With the advent of the Internet, synchronous work prospects expanded to include anything from chat rooms to videoconferencing services. Additionally, asynchronous material exchange was substantially relocated to digital settings and communication channels ( Virtič et al., 2021 ).

Distance learning is a fundamentally different way to communication as well as a different learning framework. An instructor may not meet with pupils in live broadcasts at all in distance learning, but merely follow them in a chat if required ( Bozkurt and Sharma, 2020 ). Audio podcasts, films, numerous simulators, and online quizzes are just a few of the technological tools available for distance learning. The major aspect of distance learning, on the other hand, is the detailed tracking of a student’s performance, which helps to develop his or her own trajectory. While online learning attempts to replicate classroom learning methods, distant learning employs a computer game format, with new levels available only after the previous ones have been completed ( Bakhov et al., 2021 ).

In recent years, increased attention has been placed on eLearning in educational institutions because to the numerous benefits that have been discovered via study. These advantages include the absence of physical and temporal limits, the ease of accessing material and scheduling flexibility, as well as the cost-effectiveness of the solution. A number of other studies have demonstrated that eLearning is beneficial to both student gains and student performance. However, in order to achieve the optimum results from eLearning, students must be actively participating in the learning process — a notion that is commonly referred to as active learning — throughout the whole process ( Aldossary, 2021 ; Altun et al., 2021 ).

The most commonly mentioned negatives include technological difficulties and the inability to open the system as a result, low teaching quality, inability to teach applicable disciplines, and a lack of courses, contact, communication, and internet ( Altun et al., 2021 ). Also, misuse of technology, adaptation of successful technology-based training to effective teaching methods, and bad practices in managing the assessment and evaluation process of learning are all downsides of distance learning ( Debeş, 2021 ).

Distance Learning in a Pandemic Context

The epidemic forced schools, colleges, and institutions throughout the world to close their doors so that students might practice social isolation ( Toquero, 2020 ). Prior to the pandemic, demand for distance learning was nascent, as it was a novel mode of education, the benefits and quality of which were difficult to judge due to a dearth of statistics. But, in 2020, humanity faced a coronavirus pandemic, which accelerated the shift to distant learning to the point that it became the only viable mode of education and communication ( Viktoria and Aida, 2020 ). Due to the advancements in digital technology, educators and lecturers have been obliged to use E-learning platforms ( Benadla and Hadji, 2021 ).

In remote education settings for higher education, activities are often divided into synchronous course sessions and asynchronous activities and tasks. In synchronous courses, learners participate in interactive and targeted experiences that help them develop a fundamental grasp of technology-enhanced education, course design, and successful online instruction. Asynchronous activities and tasks, on the other hand, include tests, group work assignments, group discussion, feedback, and projects. Additionally, asynchronous activities and tasks are carried out via interactive video-based activities, facilitator meetings, live webinars, and keynote speakers ( Debeş, 2021 ).

According to Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė (2021) , ICT should be attractive for learners. Additionally, student satisfaction with ODL has a statistically significant effect on their future choices for online learning ( Virtič et al., 2021 ). According to Avsheniuk et al. (2021) , the majority of research is undertaken to categorize students’ views and attitudes about online learning, and studies examining students’ perspectives of online learning during the COVID-19 epidemic are uncommon and few. There is presently a dearth of research on the impact on students when schools are forced to close abruptly and indefinitely and transition to online learning communities ( Unger and Meiran, 2020 ). So that, the mini-review is aimed to examining the students’ views on using distance learning during COVID-19.

In order to perform the aim, the articles were searched through ERIC database. We use “Distance learning” AND “University” AND “COVID” as search terms. We obtained 139 articles. We selected “full text” and “Peer reviewed only” articles. After the exclusion, 58 articles endured. Then content analyses were used to determine articles related to students’ voices about distance learning. In the final list, there were 27 articles ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Countries and data collection tools.

In the study, a qualitative approach and content analyses were preferred. Firstly, the findings related to students’ attitudes and opinions on distance learning were determined. The research team read selected sections independently. Researchers have come to a consensus on the themes of perception and attitudes, advantages of distance learning, disadvantages of distance learning, and challenges for distance learning. It was decided which study would be included in which theme/s. Finally, the findings were synthesized under themes.

Only 3 studies ( Lassoued et al., 2020 ; Viktoria and Aida, 2020 ; Todri et al., 2021 ) were conducted to cover more than one country. Other studies include only one country. Surveys and questionnaires were mostly used as measurement tools in the study. Due to pandemic restrictions, online data collection approaches were preferred in the data collection process.

Students’ views on distance learning are grouped under four themes. These themes are perception and attitudes, advantages of distance learning, disadvantages of distance learning, and challenges for distance learning.

Perception and Attitudes Toward Distance Learning

Students’ attitudes toward distance learning differ according to the studies. In some studies ( Mathew and Chung, 2020 ; Avsheniuk et al., 2021 ), it is stated that especially the students’ attitudes are positive, while in some studies ( Bozavlı, 2021 ; Yurdal et al., 2021 ) it is clearly stated that their attitudes are negative. In addition, there are also studies ( Akcil and Bastas, 2021 ) that indicate that students’ attitudes are at a moderate level. The transition to distance learning has been a source of anxiety for some students ( Unger and Meiran, 2020 ).

When the students’ satisfaction levels are analyzed, it is obvious from the research ( Gonçalves et al., 2020 ; Avsheniuk et al., 2021 ; Bakhov et al., 2021 ; Glebov et al., 2021 ; Todri et al., 2021 ) that the students’ satisfaction levels are high. In some studies, it is pronounced that the general satisfaction level of the participants is moderate ( Viktoria and Aida, 2020 ; Aldossary, 2021 ; Didenko et al., 2021 ) and low ( Taşkaya, 2021 ).

When students compare face-to-face and online learning methods, they state that online learning has opportunities to compensate for their deficiencies due to the pandemic conditions ( Abrosimova, 2020 ) and but they prefer face-to-face learning ( Gonçalves et al., 2020 ; Kaisar and Chowdhury, 2020 ; Bakhov et al., 2021 ). Distance learning is not sufficiently motivating ( Altun et al., 2021 ; Bozavlı, 2021 ), effective ( Beltekin and Kuyulu, 2020 ; Bozavlı, 2021 ), and does not have a contribution to students’ knowledge ( Taşkaya, 2021 ). Distance education cannot be used in place of face-to-face instruction ( Aldossary, 2021 ; Altun et al., 2021 ).

Advantages of Distance Learning

It is mostly cited advantages that distance learning has a positive effect on achievement and learning ( Gonçalves et al., 2020 ; Lin and Gao, 2020 ; Aldossary, 2021 ; Altun et al., 2021 ; Şahin, 2021 ). In addition, in distance learning, students can have more resources and reuse resources such as re-watching video ( Önöral and Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, 2020 ; Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ; Martha et al., 2021 ).

Distance learning for the reason any time and everywhere learning ( Adnan and Anwar, 2020 ; Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ; Todri et al., 2021 ). There is no need to spend money on transportation to and from the institution ( Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ; Nenakhova, 2021 ). Also, staying at home is safe during pandemics and less stressful for students ( Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ).

Challenges and Disadvantages of Distance Learning

Distance learning cannot guarantee effective learning, the persistence of learning, or success ( Altun et al., 2021 ; Benadla and Hadji, 2021 ). Students state that they have more works, tasks, and study loads in the distance learning process ( Mathew and Chung, 2020 ; Bakhov et al., 2021 ; Didenko et al., 2021 ; Nenakhova, 2021 ). Group working and socialization difficulties are experienced in distance learning ( Adnan and Anwar, 2020 ; Bozavlı, 2021 ; Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ). The absence of communication and face-to-face interaction is seen a disadvantage ( Didenko et al., 2021 ; Nenakhova, 2021 ).

It is difficult to keep attention on the computer screen for a long time, so distance-learning negatively affects concentration ( Bakhov et al., 2021 ; Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ). In addition, distance education prompts some physical and psychological health problems ( Kaisar and Chowdhury, 2020 ; Taşkaya, 2021 ).

Devices and internet connection, technical problems are mainly stated as challenges for distance learning ( Abrosimova, 2020 ; Adnan and Anwar, 2020 ; Mathew and Chung, 2020 ; Bakhov et al., 2021 ; Benadla and Hadji, 2021 ; Didenko et al., 2021 ; Lamanauskas and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, 2021 ; Nenakhova, 2021 ; Taşkaya, 2021 ; Şahin, 2021 ). In addition, some students have difficulties in finding a quiet and suitable environment where they can follow distance education courses ( Taşkaya, 2021 ). It is a disadvantage that students have not the knowledge and skills to use the technological tools used in distance education ( Lassoued et al., 2020 ; Bakhov et al., 2021 ; Didenko et al., 2021 ).

The purpose of this study is to ascertain university students’ perceptions about distant education during COVID-19. The study’s findings are intended to give context for developers of distant curriculum and higher education institutions.

According to Toquero (2020) , academic institutions have an increased need to enhance their curricula, and the incorporation of innovative teaching methods and tactics should be a priority. COVID-19’s lockout has shown the reality of higher education’s current state: Progressive universities operating in the twenty-first century did not appear to be prepared to implement digital teaching and learning tools; existing online learning platforms were not universal solutions; teaching staff were not prepared to teach remotely; their understanding of online teaching was sometimes limited to sending handbooks, slides, sample tasks, and assignments to students via email and setting deadlines for submission of completed tasks ( Didenko et al., 2021 ).

It is a key factor that student satisfaction to identify the influencers that emerged in online higher education settings ( Parahoo et al., 2016 ). Also, there was a significant positive relationship between online learning, social presence and satisfaction with online courses ( Stankovska et al., 2021 ). According to the findings, the attitudes and satisfaction levels of the students differ according to the studies and vary in a wide range from positive to negative attitudes.

According to the study’s findings, students responded that while online learning is beneficial for compensating for deficiencies during the pandemic, they would prefer face-to-face education in the future. This is a significant outcome for institutions. It is not desirable for all students to take their courses entirely online. According to Samat et al. (2020) , the one-size-fits-all approach to ODL implementation is inapplicable since it not only impedes the flow of information delivery inside the virtual classroom, but it also has an impact on psychological well-being because users are prone to become disturbed.

In distance learning, students can have more resources and reuse resources such as re-watching videos. So, distance learning has a positive effect on achievement and learning. Alghamdi (2021) stated that over the last two decades, research on the influence of technology on students’ academic success has revealed a range of good and negative impacts and relationships, as well as zero effects and relationship.

The result also shows that distance education prompts some physical and psychological health problems. Due to the difficulty of maintaining focus on a computer screen for an extended period of time, remote education has a detrimental effect on concentration. There is some evidence that students are fearful of online learning in compared to more traditional, or in-person, in-class learning environments, as well as media representations of emergencies ( Müller-Seitz and Macpherson, 2014 ).

Unsatisfactory equipment and internet connection, technical difficulties, and a lack of expertise about remote learning technology are frequently cited as distance learning issues. Due to the pandemic’s quick move to online education, many schools have an insufficient infrastructure. Infrastructure deficiency is more evident in fields that require laboratory work such as engineering ( Andrzej, 2020 ) and medicine ( Yurdal et al., 2021 ).

Conclusion and Recommendation

To sum up, students’ opinions and levels of satisfaction vary significantly, ranging from positive to negative. Distance learning for the reason any time and everywhere learning. Distance learning has a positive effect on achievement and learning. Staying at home is safe during pandemics and less stressful for students. Distance education prompts some physical and psychological health problems such as fear, anxiety, stress, and losing concentration. Due to the pandemic’s quick move to online education, many schools have an insufficient infrastructure. Future researchers can investigate what distance education models can be that will eliminate the complaints of students. Students’ positive attitudes and levels of satisfaction with their distant education programs have an impact on their ability to profit from the program. Consequently, schools wishing to implement distant education should begin by developing a structure, content, and pedagogical approach that would improve the satisfaction of their students. According to the findings of the study, there is no universally applicable magic formula since student satisfaction differs depending on the country, course content, and external factors.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This manuscript has been supported by the Kazan Federal University Strategic Academic Leadership Program.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abrosimova, G. A. (2020). Digital literacy and digital skills in university study. Int. J. High. Educ. 9, 52–58. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v9n8p52

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Adnan, M., and Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: students perspectives. J. Pedagog. Soc. Psychol. 1, 45–51. doi: 10.33902/JPSP.2020261309

Akhmadieva, R. S., Mikhaylovsky, M. N., Simonova, M. M., Nizamutdinova, S. M., Prokopyev, A. I., and Ostanina, S. S. (2021). Public relations in organizations in sportsman students view: development of management tools or healthy and friendly relations formation. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 16, 1272–1279. doi: 10.14198/jhse.2021.16.Proc3.43

Akcil, U., and Bastas, M. (2021). Examination of university students’ attitudes towards e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic process and the relationship of digital citizenship. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 13:e291. doi: 10.30935/CEDTECH/9341

Aldossary, K. (2021). Online distance learning for translation subjects: tertiary level instructors’ and students’ perceptions in Saudi Arabia. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 22:6.

Google Scholar

Alghamdi, A. (2021). COVID-19 mandated self-directed distance learning: experiences of Saudi female postgraduate students. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 18:014. doi: 10.53761/1.18.3.14

Altun, T., Akyıldız, S., Gülay, A., and Özdemir, C. (2021). Investigating education faculty students’ views about asynchronous distance education practices during COVID-19. Psycho Educ. Res. Rev. 10, 34–45.

Andrzej, O. (2020). Modified blended learning in engineering higher education during the COVID-19 lockdown — building automation courses case study. Educ. Sci. 10:292.

Avsheniuk, N., Seminikhyna, N., Svyrydiuk, T., and Lutsenko, O. (2021). ESP students’ satisfaction with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in ukraine. Arab World Engl. J. 1, 222–234. doi: 10.24093/awej/covid.17

Bakhov, I., Opolska, N., Bogus, M., Anishchenko, V., and Biryukova, Y. (2021). Emergency distance education in the conditions of COVID-19 pandemic: experience of Ukrainian universities. Educ. Sci. 11:364. doi: 10.3390/educsci11070364

Beltekin, E., and Kuyulu, İ (2020). The effect of coronavirus (COVID19) outbreak on education systems: evaluation of distance learning system in Turkey. J. Educ. Learn. 9:1. doi: 10.5539/jel.v9n4p1

Benadla, D., and Hadji, M. (2021). EFL students affective attitudes towards distance e-learning based on moodle platform during the COVID-19 the pandemic: perspectives from Dr. Moulaytahar university of Saida, Algeria. Arab World Engl. J. 1, 55–67. doi: 10.24093/awej/covid.4

Bozavlı, E. (2021). Is foreign language teaching possible without school? Distance learning experiences of foreign language students at Ataturk university during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arab World Engl. J. 12, 3–18. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol12no1.1

Bozkurt, A., and Sharma, R. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to CoronaVirus pandemic. Asian J. Distance Educ. 15:2020.

Debeş, G. (2021). Distance learning in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: advantages and disadvantages. Int. J. Curr. Instr. 13, 1109–1118.

Didenko, I., Filatova, O., and Anisimova, L. (2021). COVID-19 lockdown challenges or new era for higher education. Propós. Represent. 9:e914. doi: 10.20511/pyr2021.v9nspe1.914

Falode, O. C., Chukwuemeka, E. J., Bello, A., and Baderinwa, T. (2020). Relationship between flexibility of learning, support services and students’ attitude towards distance learning programme in Nigeria. Eur. J. Interact. Multimed. Educ. 1:e02003. doi: 10.30935/ejimed/8320

Gaba, A. K., Bhushan, B., and Kant Rao, D. (2021). Factors influencing the preference of distance learners to study through online during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J. Distance Educ. 16:2021.

Glebov, V. A., Popov, S. I., Lagusev, Y. M., Krivova, A. L., and Sadekova, S. R. (2021). Distance learning in the humanitarian field amid the coronavirus pandemic: risks of creating barriers and innovative benefits. Propós. Represent. 9:e1258. doi: 10.20511/pyr2021.v9nspe3.1258

Gonçalves, S. P., Sousa, M. J., and Pereira, F. S. (2020). Distance learning perceptions from higher education students—the case of Portugal. Educ. Sci. 10:374. doi: 10.3390/educsci10120374

Graham, S. R., Tolar, A., and Hokayem, H. (2020). Teaching preservice teachers about COVID-19 through distance learning. Electron. J. Res. Sci. Math. Educ. 24, 29–37.

Insorio, A. O., and Macandog, D. M. (2022). Video lessons via youtube channel as mathematics interventions in modular distance learning. Contemp. Math. Sci. Educ. 3:e22001. doi: 10.30935/conmaths/11468

Kaisar, M. T., and Chowdhury, S. Y. (2020). Foreign language virtual class room: anxiety creator or healer? Engl. Lang. Teach. 13:130. doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n11p130

Lamanauskas, V., and Makarskaitė-Petkevičienė, R. (2021). Distance lectures in university studies: advantages, disadvantages, improvement. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 13:e309. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/10887

Lassoued, Z., Alhendawi, M., and Bashitialshaaer, R. (2020). An exploratory study of the obstacles for achieving quality in distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 10:232. doi: 10.3390/educsci10090232

Lin, X., and Gao, L. (2020). Students’ sense of community and perspectives of taking synchronous and asynchronous online courses. Asian J. Distance Educ. 15, 169–179. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.3881614

Martha, A. S. D., Junus, K., Santoso, H. B., and Suhartanto, H. (2021). Assessing undergraduate students’ e-learning competencies: a case study of higher education context in Indonesia. Educ. Sci. 11:189. doi: 10.3390/educsci11040189

Mathew, V. N., and Chung, E. (2020). University students’ perspectives on open and distance learning (ODL) implementation amidst COVID-19. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 16, 152–160. doi: 10.24191/ajue.v16i4.11964

Müller-Seitz, G., and Macpherson, A. (2014). Learning during crisis as a ‘war for meaning’: the case of the German Escherichia coli outbreak in 2011. Manag. Learn. 45, 593–608.

Nenakhova, E. (2021). Distance learning practices on the example of second language learning during coronavirus epidemic in Russia. Int. J. Instr. 14, 807–826. doi: 10.29333/iji.2021.14347a

Önöral, Ö, and Kurtulmus-Yilmaz, S. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on dental education in cyprus: preclinical and clinical implications with E-learning strategies. Adv. Educ. 7, 69–77.

Palatovska, O., Bondar, M., Syniavska, O., and Muntian, O. (2021). Virtual mini-lecture in distance learning space. Arab World Engl. J. 1, 199–208. doi: 10.24093/awej/covid.15

Parahoo, S. K., Santally, M. I., Rajabalee, Y., and Harvey, H. L. (2016). Designing a predictive model of student satisfaction in online learning. J. Market. High. Educ. 26, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2015.1083511

Samat, M. F., Awang, N. A., Hussin, S. N. A., and Nawi, F. A. M. (2020). Online distance learning amidst COVID-19 pandemic among university students: a practicality of partial least squares structural equation modelling approach. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 16, 220–233.

Simonson, M., and Berg, G. A. (2016). Distance Learning. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Available online at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/distance-learning (accessed November 14, 2011).

Stankovska, G., Dimitrovski, D., and Ibraimi, Z. (2021). “Online learning, social presence and satisfaction among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic,” in Paper Presented at the Annual International Conference of the Bulgarian Comparative Education Society (BCES) , (Sofia), 181–188.

Şahin, M. (2021). Opinions of university students on effects of distance learning in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. Afr. Educ. Res. J. 9, 526–543. doi: 10.30918/aerj.92.21.082

Tal, C., Tish, S., and Tal, P. (2022). Parental perceptions of their preschool and elementary school children with respect to teacher-family relations and teaching methods during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Pedagog. Res. 7:em0114. doi: 10.29333/pr/11518

Taşkaya, S. M. (2021). Teacher candidates’ evaluation of the emergency remote teaching practices in turkey during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Progress. Educ. 17, 63–78. doi: 10.29329/ijpe.2021.366.5

Todri, A., Papajorgji, P., Moskowitz, H., and Scalera, F. (2021). Perceptions regarding distance learning in higher education, smoothing the transition. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 13:e287. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/9274

Toquero, C. M. (2020). Challenges and opportunities for higher education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: the Philippine context. Pedagog. Res. 5:em0063. doi: 10.29333/pr/7947

Tugun, V., Bayanova, A. R., Erdyneeva, K. G., Mashkin, N. A., Sakhipova, Z. M., and Zasova, L. V. (2020). The opinions of technology supported education of university students. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 15, 4–14. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i23.18779

Unger, S., and Meiran, W. (2020). Student attitudes towards online education during the COVID-19 viral outbreak of 2020: distance learning in a time of social distance. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 4, 256–266. doi: 10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.107

Valeeva, R., and Kalimullin, A. (2021). Adapting or changing: the COVID-19 pandemic and teacher education in Russia. Educ. Sci. 11:408. doi: 10.3390/educsci11080408

Viktoria, V., and Aida, M. (2020). comparative analysis on the impact of distance learning between Russian and Japanese university students, during the pandemic of COVID-19. Educ. Q. Rev. 3:438–446. doi: 10.31014/aior.1993.03.04.151

Virtič, M. P., Dolenc, K., and Šorgo, A. (2021). Changes in online distance learning behaviour of university students during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak, and development of the model of forced distance online learning preferences. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 10, 393–411. doi: 10.12973/EU-JER.10.1.393

Yurdal, M. O., Sahin, E. M., Kosan, A. M. A., and Toraman, C. (2021). Development of medical school students’ attitudes towards online learning scale and its relationship with E-learning styles. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 22, 310–325. doi: 10.17718/tojde.961855

Zagkos, C., Kyridis, A., Kamarianos, I., Dragouni, K E., Katsanou, A., Kouroumichaki, E., et al. (2022). Emergency remote teaching and learning in greek universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: the attitudes of university students. Eur. J. Interact. Multimed. Educ. 3:e02207. doi: 10.30935/ejimed/11494

Keywords : ICT, distance learning, COVID-19, higher education, online learning

Citation: Masalimova AR, Khvatova MA, Chikileva LS, Zvyagintseva EP, Stepanova VV and Melnik MV (2022) Distance Learning in Higher Education During Covid-19. Front. Educ. 7:822958. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.822958

Received: 26 November 2021; Accepted: 14 February 2022; Published: 03 March 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Masalimova, Khvatova, Chikileva, Zvyagintseva, Stepanova and Melnik. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alfiya R. Masalimova, [email protected]

† ORCID: Alfiya R. Masalimova, orcid.org/0000-0003-3711-2527 ; Maria A. Khvatova, orcid.org/0000-0002-2156-8805 ; Lyudmila S. Chikileva, orcid.org/0000-0002-4737-9041 ; Elena P. Zvyagintseva, orcid.org/0000-0001-7078-0805 ; Valentina V. Stepanova, orcid.org/0000-0003-0495-0962 ; Mariya V. Melnik, orcid.org/0000-0001-8800-4628

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Student's perspective on distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of Western Michigan University, United States

Wassnaa al-mawee.

a Department of Computer Science, Western Michigan University, 1903 W. Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5466, USA

Keneth Morgan Kwayu

b Department of Civil and Transportation Engineering, Western Michigan University, 1903 W. Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5466, USA

Tasnim Gharaibeh

As the distance learning process has become more prevalent in the USA due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to understand students’ experiences, perspectives, and preferences. Our study's purpose is to reveal students’ perspectives and preferences on distance learning due to the dramatic change that happened in the education process. Western Michigan University is used as the case study to achieve that purpose. Participants completed an online survey that investigated two measures: distance learning and instructional methods with a set of scales associated with each. Students reported negative experiences of distance learning such as lack of social interaction and positive experiences such as time and location flexibility. These findings may help WMU and higher educational institutions to improve distance learning education.

1. Introduction

The benefits and challenges of distance learning have been a subject of continuous discussion in the past. Of recent, the topic of distance learning has become more relevant and imminent due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 has compelled most of the higher education institutions to shift to either distance learning and/or some form of hybrid teaching model ( Smalley, 2020 ). This has disrupted the natural ecosystem of conventional learning environments where students live and study in close proximity. Challenges that have been raised in the previous studies about distance learning include variation in the quality of educational instructions, students’ unequal access to the essential technologies for distance learning, and technology readiness of students ( Ratliff, 2009 ). For example, one study found that 20% of students reported having issues in accessing essential technology for distance learning such as laptops and high-speed internet ( Gonzales, Calarco, & Lynch, 2018 ). Also, it has been found that students who were already suffering academically in face-to-face instruction are more likely to obtain lower grade points in distance learning ( Xu & Jaggars, 2014 ). Despite the challenges, this sudden and unexpected change in the learning environment offers opportunities for academic institutions to reimage innovative modes of learning that take advantage of the current technologies. Therefore, the challenges and opportunities of shifting from in-person instruction mode to remote/distance instruction mode need a thorough assessment. This study intends to explore the benefits and challenges of distance learning based on student's perspectives. The case study selected 5000 students randomly from all undergraduate and graduate students at Western Michigan University to participate in the survey and we got 420 responses.

2. Related work

Distance education, or remote learning, refers to technology-based teaching in which students during the entire course of learning are physically removed from teachers at a place. It is learning from outside the normal classroom and involves online education ( Lei & Gupta, 2010 ) A distance learning program can be completely distance learning, or a combination of distance learning and traditional classroom instruction (called hybrid) ( Tabor, 2007 ). This form of teaching helps teachers to access a considerably broader audience and facilitates greater versatility in the curriculum for students. Online education is a term under the distance education umbrella. It is education that takes place over the Internet. It is often referred to as “e-learning” in other terms. However, it is just one type of “distance learning”.

Many works and research were made to study the students’ perceptions of distance learning. In one of them, especially related to students’ perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, Aristovnik, Keržič, Ravšelj, Tomaževič, and Umek (2020) introduced a comprehensive and large-scale study of students’ perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on different aspects of their lives on a global level. Their study sample contains 30,383 students enrolled in higher education institutions, who were at least 18 years old from 62 countries, where a multi-lingual web-based comprehensive questionnaire composed of 39 predominantly closed-ended questions was used to collect the data. The questionnaire addressed socio-demographic, geographic, and other characteristics, in addition to the various features and elements of higher education student life, such as online academic work and life, emotional life, social life, personal situations, changing habits, responsibilities, as well as personal thoughts on COVID-19.

Under the online academic, as part of the distance learning, work, and life element, an ordinal logistic regression analysis was used to indicate which factors influence the students’ satisfaction with the role of the university. This logistic regression model implemented in Python programming language using libraries Pandas and Numpy which is the same language that they used to prepare, clean, and aggregate their data. The results emphasize that satisfaction with asynchronous online teaching methods such as recorded videos (p<0.001), information on exams oqr the procedure of examination in times of crisis (p<0.001), teaching staff (lecturers), and websites, social media information have a positive effect on students’ satisfaction with the role of the university during the COVID-19 pandemic. The result also showed that the students’ workload was larger or significantly larger in online teaching, in addition to some difficulty in using online teaching platforms ( Aristovnik et al., 2020 ).

On the other hand, to answer the question of how students experience distance learning, Blackmon and Major (2012) introduced an investigation using qualitative research synthesis to collect the data. They ended with 10 studies focusing on online learning. To analyze the data, they summarized the articles and extracted findings. The findings were grouped into student factors that influenced experience and instructor factors that influenced student experience. Students must combine work and families, handle time and devote themselves individually. In the absence of physical copresence, teachers can strive to develop academic relationships with students and to create a sense of community. The balance between student and teacher considerations affects the classroom and student interactions. According to their theoretical framework suggestion, the students are more abstract and understandingly observing their academic experiences. In some situations, students appeared to miss the physical markers and signals that make social interactions easier to discuss. In other situations, some students seemed to succeed in the new environment. Although the student must be responsible, the teacher also has a significant role to do to generate creative online environments that facilitate the delivery and use of new intellectual skills.

Another survey of professors, staff, and students was commissioned by Illinois Community Colleges Online in 2005 to determine the pressing concerns affecting quality, retention, and capacity building related to online learning. About one thousand people from seventeen Illinois community colleges presented data relating to these three problems over six months ( Hutti, 2007 ). Three separate methods were used in the data collection method: an electronic survey of faculty, employees, and students; a focus group including faculty, employees, and students; and interviews with select faculty, employees, and students. The findings of the review of the collected data showed that the consistency benchmarks that were most important and least important for distance learning, especially online learning, were decided by faculty, staff, and students. Using a four-point Likert Scale (Strongly Agree = 4, Agree = 3, Disagree = 2, and Strongly Disagree = 1), all three groups of respondents were asked to rate the importance of each quality benchmark. The top 5 quality benchmarks rated most important based on highest means where technical assistance in course development is available to faculty, a college-wide system (such as Blackboard or WebCT) supports and facilitates the online courses, faculty are encouraged to use technical assistance in course development, faculty give constructive feedback on student assignments and to their questions, and faculty are assisted in the transition from classroom teaching to online instruction ( Hutti, 2007 ).

To focus on a specific level college, Fedynich, Bradley and Bradley (2015) studied the graduate students’ perceptions regarding distance learning using the analysis of an online survey. Their findings indicate that the role of the teacher, the contact between students and with the teacher, and feedback and assessment were identified as being essential to the satisfaction of the students. Other difficulties found included technical support for learners connected to campus services, and the need for differing educational design and implementation to promote the ability of students to study. Students, on the other hand, were highly pleased with the consistency and organization of teaching using the right tools.

In order to find ways to improve and support distance learning, faculty members in the Distance Education Center at the University of West Georgia came together to form the “Online Refresh Faculty Learning Community” (FLC) ( Rath, Olmstead, Zhang, & Beach, 2019 ). They introduced a study conducted at a public comprehensive university located in the northeastern United States. The participants were invited to answer an online survey through Qualtrics that collected quantitative and qualitative data. Coding sheets in Excel and SPSS were used for analyzing quantitative data where qualitative data were analyzed using grounded theory procedures. In the quantitative data, the result under the factor of comfort level using technology showed 55% of participants were extremely comfortable using technology and only 2% were uncomfortable. Under the preferred course modality factor, students preferred the in-person courses followed by the online courses, and at last, the hybrid/blind courses. Four factors were addressed in the qualitative data results, set-up of the course; learner characteristics and sense of course learning; social interactions; and technology issues. Regarding how the course set up by the instructor influenced the perceptions of students about the quality and efficacy of distance learning environments, successful contact was considered as a key to an online course's progress. Next, the clear due dates and understandable instructions on assignments came as important components of the course organization. Under learner characteristics, distance learning works best for the students who demonstrate strong self-regulatory behaviors and managing their time. Also, many students in their study surveyed reported frustration with learning online applications and with the lack of reliability of the internet. On the other hand, their result showed clearly, the social aspect of face-to-face classes is very important and valuable to most students.

Students stated some advantages for distance learning such as saving time, fitting in better with schedules, enabling students to take more courses, self-paced study, time and space flexibility, distance learning course often costs less ( O'Malley & McCraw, 1999 ). The disadvantages of distance learning that were mentioned include the need for consistent access to technology, the absence of face-to-face contact ( Young & Norgard, 2006 ), the feeling of isolation, the challenge to remain focused, and the difficulty of obtaining immediate feedback ( Lei & Gupta, 2010 ; Paepe, Zhu, & Depryck, 2017 ; Venter, 2010 ; Zuhairi, Zuhairi, Wahyono, & Suratinah, 2006 ).

Many recommendations arising from the previous studies include the following suggestions; continue to offer the courses in many formats (in-person and online) to provide a choice for students, continue to offer professional development and training for instructors ( Burns, 2013 ), providing the learners with social support and sufficient motivation, instead of providing only synchronous or only asynchronous practices, using these environments together ( Allen, 2017 ; Cankaya & Yunkul, 2018 ) consider the students who have complex and special needs with special education support, try to open communication channels among administrators, educators, and students and improve mental wellness programs and provide proactive psychosocial help to students ( Allen, 2017 ).

The purpose of the present study was to share information and experiences that can positively impact distance learning in WMU, besides revealing the factors that affect the students’ experience and investigating the impact of student and college characteristics on perceptions of online learning. The study examined two key college characteristics – namely, college-level and college type to reveal the students’ preferences and experiences of distance learning at WMU. The study pursued to address the following explicit research questions:

- 1 What are the WMU students' general perceptions about distance learning?

- 2 What are the significant differences in perceptions of distance learning when comparing different college types?

- 3 How are perceptions of graduate-level students differ from the perceptions of undergraduate-level students of distance learning?

- 4 What are the students’ preferences regarding instructional methods of distance learning?

4.1. Data collection procedure

The survey was administered online through Western Michigan University's official website, Qualtrics. Qualtrics platform is a powerful platform for survey design, and it was available on the WMU official website to all WMU students, faculty, and staff. Informed consent and a link to the survey were distributed to students through the university e-mail. Students were asked to state their perspectives and preferences by choosing one choice in a Likert scale survey. An option is also provided for the subject to input additional comments. Students were able to complete the survey in approximately 10-15 minutes at their own convenience within two weeks. No identifiable private information was obtained from the participants.

4.2. Participants

The participants in this study were 420 undergraduate and graduate students enrolled in different distance learning - education courses during the 2019-2020 academic year at Western Michigan University, the U.S. Of the participants, 251 were female (59.76%), 160 were male (38.10%), and 9 (2.14%) were identified as other, with an age range of 18-55 years and above. In terms of college-level, 72 (17.14%) of participants were freshmen, 57 (13.57%) were sophomores, 74 (17.62%) were juniors, 105 (25.00%) were seniors, 107 (25.48%) were graduate students, and 5 (1.19%) were identified as other. The study considered all 11 colleges at WMU. Most of the participants, 107 (25.48%) from the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS), 22 (5.24%) from College of Aviation (CA), 51 (12.14%) from Haworth College of Business (HCB), 61 (14.52%) from College of Education and Human Development (CEHD), 81 (19.29%) from College of Engineering and Applied Sciences (CEAS), 29 (6.90%) from College of Fine Arts (CFA), 48 (11.43%) College of Health and Human Services (CHHS), 3 (0.71%) from Lee Honors College (LHC), 14 (3.33%) from Graduate College (GC), 0 (0.00%) from Thomas M. Cooley Law School (TMCLS) and Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine, respectively. Tables 1 and and2 depict 2 depict the participants’ gender and age by college level and college type, respectively.

Participants’ gender and age by college level,

| 72 | 57 | 74 | 105 | 107 | 5 | |

| Female | 45 | 31 | 38 | 59 | 75 | 3 |

| Male | 25 | 24 | 35 | 44 | 30 | 2 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| < 24 years old | 70 | 48 | 55 | 80 | 34 | 2 |

| 25-34 years old | 0 | 4 | 14 | 18 | 43 | 1 |

| > 35 years old | 2 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 30 | 2 |

Participants’ gender and age by college type,

| Total | 107 | 22 | 51 | 61 | 81 | 29 | 48 | 3 | 14 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 73 | 5 | 29 | 46 | 25 | 18 | 43 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Male | 29 | 17 | 22 | 14 | 56 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| Other | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Age range | ||||||||||

| < 24 years old | 74 | 19 | 41 | 28 | 63 | 26 | 27 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| 25-34 years old | 20 | 2 | 6 | 19 | 14 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| > 35 years old | 13 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

To assess the sample representativeness, the survey sample size was compared with the total number of students in WMU by college level and age. Out of 22,562 students at WMU, 4802 (21.28%) were graduate students and 17,760 (78.72%) were undergraduate students. The total percentage by college-level aligned well with the survey sample size, whereby out of 420 participants, 107 (25.48%) were graduate students and 313 (74.52%) were graduate students. In terms of age group, most of the WMU students were below 24 years old (75%), followed by 24-34 years (17%) and greater than 34 years (8%). The same pattern was observed in the survey sample size with students below 24 years constituting 69% followed by 24-34 years (19%) and greater than 34 years (12%).

4.3. Measures

The survey incorporated demographic questions, Likert scale questions, and open-end questions. Participants answered five demographic questions regarding gender, age, college level, college type, and department types. Also, they were asked to rate the items using a five-point scale (“Strongly Agree”, “Agree”, “Neutral”, “Disagree”, “Strongly Disagree”). In addition, the participants were asked to input additional comments as open-end questions. The Likert scale and text-based measurements are reconstructed into scales and items as shown in Table 3 and Table 4 , respectively.

Measures for distance learning,

| Distance learning flexibility | Distance learning is effective due to location flexibility (Item 1), Distance learning is effective due to class-time flexibility (Item 2), Distance learning saves your time and effort to reach the campus (Item 3), Distance learning causes spending more time doing your classwork (Item 8), You are keeping up with your schoolwork in distance learning as much as you were in personal learning (Item 10) |

| Distance learning improvement | Distance learning has improved on-campus classes (in-class learning) (Item 4), Distance learning has better instruction (Item 5), With distance learning, you have learned as much as you were before the COVID-19 crisis (Item 9), Distance learning improves your grades vs. personal learning (Item 11) |

| Students interaction and collaboration | Distance learning provides more interaction with the instructor (Item 6), Distance learning provides more interaction with classmates (Item 7) |

| Computer and internet usage | Distance learning is manageable because you have internet access at home (Item 12), You have access to a computer or device (other than a computer) that you can use for distance learning (Item 13) |

| 1. Are you satisfied with the distance learning education provided to you? | |

| 2. Do you prefer to continue distance learning? | |

Measures for instructional methods,

| Instructors | Your instructor has provided you clear instructions for how to access the online instructional materials for your classes (Item 1), Your instructors are available online to you when you need help (Item 2), Your instructors have provided you with different ways to demonstrate your learning online (Item 3), Online contact with your instructor is better than face-to-face (Item 4) |

| Distance learning tools | It is easy to use distance learning tools that WMU/ instructor provides (Item 5), Meeting and learning through WebEx, Zoom, and Microsoft365) are effective (Item 6) |

| Distance learning methods’ preferences | You prefer in-person or hybrid classes over online classes (Item 7), Online classes are a preferable choice due to COVID-19 crises (Item 8), You prefer asynchronous online teaching method (Require no in-person or synchronous online meetings) (Item 9), You prefer synchronous online teaching method (Classes meet exclusively through distance education technologies) (Item 10) |

| 1. What is the best thing about the online teaching? | |

| 2. What is the worst thing about the online teaching? | |

5. Statistical Methods

The distributions of student's responses to distance learning were analyzed using cross-tabulations and statistical tests. The Chi-square test of independence was used to test if there was a significant association between students’ response to the distance learning experience by college level and college type. The Chi-Square test is a non-parametric test, and it is suitable for categorical data analysis to assess the probability of association or independence of facts ( McHugh, 2012 ). It does not impose prior conditions to the data such as equality of variance or residual homoscedasticity ( Pandis, 2016 ). The test measures how much difference exists between the observed counts and the counts that would be expected if there were no relationship at all in the population. In this study, the null hypothesis (H o ) stated that there is no difference in student rating of a given question related to distance learning across college level or college type. The alternative hypothesis (H 1 ) is the inverse of the null hypothesis stating that there is a difference in student ratings by college type or college level. The null hypothesis was rejected if the p -value was less than 0.05. The Chi-square statistics can be computed using Eq. (1 );

whereby, O i j is the observed frequency and E i j is the expected frequency. The computed χ 2 is compared with the critical value obtained from the Chi-square distribution. The degrees of freedom ( df ) for the critical value can be computed as (c-1) (r-1) , where c is the number of columns and r is the number of rows in the contingency table.

The Cramer's V is also used in conjunction with Chi-Squared statistics. It is used to indicate the strength of association between two variables ( Allen, 2017 ). The Cramer's V values range from 0 which corresponds to no association to 1 which corresponds to complete association. It can be computed by taking the square root of the chi-square statics divided by the sample size and normalized by the minimum of rows or columns in the contingency table as shown in Eq. (2 )

whereby χ 2 is the Chi-squared statistics, n is the sample size involved in the test, c is the number of columns and r is the number of rows.

The result section is subdivided into two subsections namely students’ perceptions of distance learning and students’ perception of instructional methods. For each subsection, the students’ rating results are discussed based on college level and college type. Data were analyzed by calculating Chi-square values, , and p-values as discussed in the statistical methods section.

6.1. Students’ perceptions of distance learning