Case Studies: High-Profile Cases of Privacy Violation

Contributor.

Case Studies: Recent FTC Enforcement Actions - High-Profile Cases of Privacy Violation: Uber, Emp Media, Lenovo, Vizio, VTech, LabMD

Uber Technologies

The scenario: In August 2018, the FTC announced an expanded settlement with Uber Technologies for its alleged failure to reasonably secure sensitive data in the cloud, resulting in a data breach of 600,000 names and driver's license numbers, 22 million names and phone numbers, and more than 25 million names and email addresses.

The settlement: The expanded settlement is a result of Uber's failure to disclose a significant data breach that occurred in 2016 while the FTC was conducting its investigation that led to the original settlement. The revised proposed order includes provisions requiring Uber to disclose any future consumer data breaches, submit all reports for third-party audits of Uber's privacy policy and retain reports on unauthorized access to consumer data. 2

Emp Media Inc. (Myex.com)

The scenario: The FTC joined forces with the State of Nevada to address privacy issues arising from the "revenge" pornography website, Myex.com, run by Emp Media Inc. The website allowed individuals to submit intimate photos of the victims, including personal information such as name, address, phone number and social media accounts. If a victim wanted their photos and information removed from the website, the defendants reportedly charged fees of $499 to $2,800 to do so.

The settlement: On June 15, 2018, the enforcement action brought by the FTC led to a shutdown of the website and permanently prohibited the defendants from posting intimate photos and personal information of other individuals without their consent. The defendants were also ordered to pay more than $2 million. 3

Lenovo and Vizio

The scenario: In 2018, FTC enforcement actions led to large settlements with technology manufacturers Lenovo and Vizio. The Lenovo settlement related to allegations the company sold computers in the U.S. with pre-installed software that sent consumer information to third parties without the knowledge of the users. With the New Jersey Office of Attorney General, the FTC also brought an enforcement action against Vizio, a manufacturer of "smart" televisions. Vizio entered into a settlement to resolve allegations it installed software on its televisions to collect consumer data without the knowledge or consent of consumers and sold the data to third parties.

The settlement: Lenovo entered into a consent agreement to resolve the allegations through a decision and order issued by the FTC. The company was ordered to obtain affirmative consent from consumers before running the software on their computers and implement a software security program on preloaded software for the next 20 years. 4 Vizio agreed to pay $2.2 million, delete the collected data, disclose all data collection and sharing practices, obtain express consent from consumers to collect or share their data, and implement a data security program. 5

The scenario: The FTC's action against toy manufacturer VTech was the first time the FTC became involved in a children's privacy and security matter. The settlement: In January 2018, the company entered into a settlement to pay $650,000 to resolve allegations it collected personal information from children without obtaining parental consent, in violation of COPPA. VTech was also required to implement a data security program that is subject to audits for the next 20 years. 6

The scenario: LabMD, a cancer-screening company, was accused by the FTC of failing to reasonably protect consumers' medical information and other personal data. Identity thieves allegedly obtained sensitive data on LabMD consumers due to the company's failure to properly safeguard it. The billing information of 9,000 consumers was also compromised. The settlement: After years of litigation, the case was heard before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. LabMD argued, in part, that data security falls outside of the FTC's mandate over unfair practices. The Eleventh Circuit issued a decision in June 2018 that, while not stripping the FTC of authority to police data security, did challenge the remedy imposed by the FTC. 7 The court ruled that the cease-and-desist order issued by the FTC against LabMD was unenforceable because the order required the company to implement a data security program that needed to adhere to a standard of "reasonableness" that was too vague. 8

The ruling points to the need for the FTC to provide greater specificity in its cease-and-desist orders about what is required by companies that allegedly fail to safeguard consumer data.

1 15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(1)

2 www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2018/04/uber-agrees-expanded-settlement-ftc-related-privacy-security

3 www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/cases/emp_order_granting_default_judgment_6-22-18.pdf

4 www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2018/01/ftc-gives-final-approval-lenovo-settlement

5 www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2017/02/vizio-pay-22-million-ftc-state-newjersey-settle-charges-it

6 www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2018/01/electronic-toy-maker-vtech-settlesftc-allegations-it-violated

7 The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has rejected this argument. See FTC v. Wyndham Worldwide Corp., 799 F.3d 236, 247-49 (2015).

8 www.media.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/files/201616270.pdf

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

United States

Mondaq uses cookies on this website. By using our website you agree to our use of cookies as set out in our Privacy Policy.

U.S. Government Accountability Office

Data Protection: Actions Taken by Equifax and Federal Agencies in Response to the 2017 Breach

Hackers stole the personal data of nearly 150 million people from Equifax databases in 2017.

How did Equifax, a consumer reporting agency, respond to that event? Equifax said that it investigated factors that led to the breach and tried to identify and notify people whose personal information was compromised.

In addition, three federal agencies that use Equifax services made their own security assessments and modified contracts with Equifax. Moreover, other federal agencies that oversee consumer reporting agencies started investigating Equifax and gave further advice to consumers on how to protect themselves against security breaches.

Hackers can make intrusions into your computer and steal personal information

Photo of a person putting personal information into a computer that could be hacked by an intruder

What GAO Found

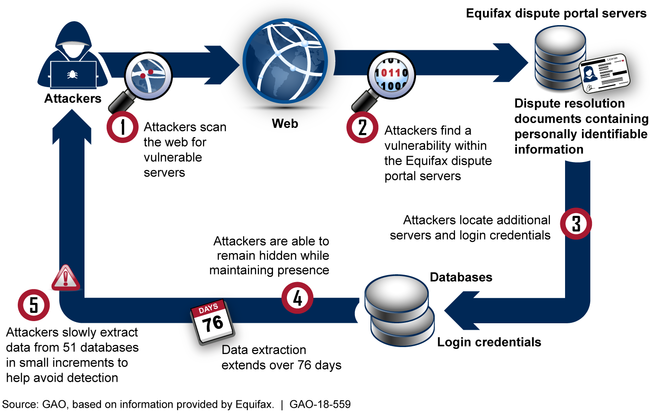

In July 2017, Equifax system administrators discovered that attackers had gained unauthorized access via the Internet to the online dispute portal that maintained documents used to resolve consumer disputes (see fig.). The Equifax breach resulted in the attackers accessing personal information of at least 145.5 million individuals. Equifax's investigation of the breach identified four major factors including identification, detection, segmenting of access to databases, and data governance that allowed the attacker to successfully gain access to its network and extract information from databases containing personally identifiable information. Equifax reported that it took steps to mitigate these factors and attempted to identify and notify individuals whose information was accessed. The company's public filings since the breach occurred reiterate that the company took steps to improve security and notify affected individuals.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Social Security Administration (SSA), and U.S. Postal Service (USPS)—three of the major federal customer agencies that use Equifax's identity verification services—conducted assessments of the company's security controls, which identified a number of lower-level technical concerns that Equifax was directed to address. The agencies also made adjustments to their contracts with Equifax, such as modifying notification requirements for future data breaches. In the case of IRS, one of its contracts with Equifax was terminated. The Department of Homeland Security offered assistance in responding to the breach; however, Equifax reportedly declined the assistance because it had already retained professional services from an external cybersecurity consultant. In addition, the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection and the Federal Trade Commission, which have regulatory and enforcement authority over consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) such as Equifax, initiated an investigation into the breach and Equifax's response in September 2017. The investigation is ongoing.

How Attackers Exploited Vulnerabilities in the 2017 Breach, Based on Equifax Information

Why GAO Did This Study

CRAs such as Equifax assemble information about consumers to produce credit reports and may provide other services, such as identity verification to federal agencies and other organizations. Data breaches at Equifax and other large organizations have highlighted the need to better protect sensitive personal information.

GAO was asked to report on the major breach that occurred at Equifax in 2017. This report (1) summarizes the events regarding the breach and the steps taken by Equifax to assess, respond to, and recover from the incident and (2) describes actions by federal agencies to respond to the breach. To do so, GAO reviewed documents from Equifax and its cybersecurity consultant related to the breach and visited the Equifax data center in Alpharetta, Georgia, to interview officials and observe physical security measures. GAO also reviewed relevant public statements filed by Equifax. Further, GAO analyzed documents from the IRS, SSA, and USPS, which are Equifax's largest federal customers for identity-proofing services, and interviewed federal officials related to their oversight activities and response to the breach.

Recommendations

GAO is not making recommendations in this report. GAO plans to issue separate reports on federal oversight of CRAs and consumer rights regarding the protection of personally identifiable information collected by such entities. A number of federal agencies and Equifax provided technical comments which we incorporated as appropriate.

Full Report

Gao contacts.

Michael Clements Director [email protected] (202) 512-8678

Nick Marinos Managing Director [email protected] (202) 512-9342

Office of Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek Acting Managing Director [email protected] (202) 512-4800

- Talk to Expert

- Machine Identity Management

- October 20, 2023

- 9 minute read

7 Data Breach Examples Involving Human Error: Did Encryption Play a Role?

Despite an overall increase in security investment over the past decade, organizations are still plagued by data breaches. What’s more, we’re learning that many of the attacks that result in breaches misuse encryption in some way. (By comparison, just four percent of data breaches tracked by Gemalto’s Breach Level Index were “secure breaches” in that the use of encryption rendered stolen data useless). Sadly, it’s often human error that allows attackers access to encrypted channels and sensitive information. Sure, an attacker can leverage “gifts” such as zero-day vulnerabilities to break into a system, but in most cases, their success involves provoking or capitalizing on human error.

Human error has a well-documented history of causing data breaches. The 2022 Global Risks Report released by the World Economic Forum, found that 95% of cybersecurity threats were in some way caused by human error. Meanwhile, the 2022 Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR) found that 82% of breaches involved the human element, including social attacks, errors and misuse.

I think it’s interesting to look at case studies on how human error has contributed to a variety of data breaches, some more notorious than others. I’ll share the publicly known causes and impacts of these breaches. But I’d also like to highlight how the misuse of encryption often compounds the effects of human error in each type of breach.

SolarWinds: Anatomy of a Supersonic Supply Chain Attack

Data breach examples.

Here is a brief review of seven well-known data breaches caused by human error.

1. Equifax data breach—Expired certificates delayed breach detection

In the spring of 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security's Computer Emergency Readiness Team (CERT) sent consumer credit reporting agency Equifax a notice about a vulnerability affecting certain versions of Apache Struts. According to former CEO Richard Smith, Equifax sent out a mass internal email about the flaw. The company’s IT security team should have used this email to fix the vulnerability, according to Smith’s testimony before the House Energy and Commerce Committee. But that didn’t happen. An automatic scan several days later also failed to identify the vulnerable version of Apache Struts. Plus, the device inspecting encrypted traffic was misconfigured because of a digital certificate that had expired ten months previously. Together, these oversights enabled a digital attacker to crack into Equifax’s system in mid-May and maintain their access until the end of July.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: Once attackers have access to a network, they can install rogue or stolen certificates that allow them to hide exfiltration in encrypted traffic. Unless HTTPS inspection solutions are available and have full access to all keys and certificates, rogue certificates will remain undetected.

Impact: The bad actor is thought to have exposed the personal information of 145 million people in the United States and more than 10 million UK citizens. In September 2018, the Information Commissioner’s Office issued Equifax a fine of £500,000, the maximum penalty amount allowed under the Data Protection Act 1998, for failing to protect the personal information of up to 15 million UK citizens during the data breach.

2. Ericsson data breach—Mobile services go dark when the certificate expires

At the beginning of December 2018, a digital certificate used by Swedish multinational networking and telecommunications company Ericsson for its SGSN–MME (Serving GPRS Support Node—Mobility Management Entity) software expired. This incident caused outages for customers of various UK mobile carriers including O2, GiffGaff, and Lyca Mobile. As a result, a total of 32 million people in the United Kingdom alone lost access to 4G and SMS on 6 December. Beyond the United Kingdom, the outage reached 11 countries including Japan.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: Expired certificates do not only cause high-impact downtime; they can also leave critical systems without protection. If a security system experiences a certificate outage , cybercriminals can take advantage of the temporary lack of availability to bypass the safeguards.

Impact: Ericsson restored the most affected customer services over the course of 6 December. The company also noted in a blog post that “The faulty software [for two versions of SGSN–MME] that has caused these issues is being decommissioned.”

3. LinkedIn data breach—Millions miss connections when the certificate expires

On 30 November, a certificate used by business social networking giant LinkedIn for its country subdomains expired. As reported by The Register , the incident did not affect www.linkedin.com, as LinkedIn uses a separate certificate for that particular domain. But the event, which involved a certificate issued by DigiCert SHA2 Secure Server CA, did invalidate us.linkedin.com along with the social media giant’s other subdomains. As a result, millions of users were unable to log into LinkedIn for several hours.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: Whenever certificates expire, it may indicate that overall protection for machine identities is not up to par. Uncontrolled certificates are a prime target for cybercriminals who can use them to impersonate the company or gain illicit access.

Impact: Later in the afternoon on 30 November, LinkedIn deployed a new certificate that helped bring its subdomains back online, thereby restoring all users’ access to the site.

4. Strathmore College data breach—Student records not adequately protected

In August 2018, it appears that an employee at Strathmore secondary college accidentally published more than 300 students’ records on the school’s intranet. These records included students' medical and mental health conditions such as Asperger’s, autism and ADHD. According to The Guardian , they also listed the exposed students’ medications along with any learning and behavioral difficulties. Overall, the records remained on Strathmore’s intranet for about a day. During that time, students and parents could have viewed and/or downloaded the information.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: Encrypting access to student records makes it difficult for anyone who doesn’t have the proper credentials to access them. Any information left unprotected by encryption can be accessed by any cybercriminals who penetrate your perimeter.

Impact: Strathmore’s principal said he had arranged professional development training for his staff to ensure they’re following best security practices. Meanwhile, Australia’s Department of Education announced that it would investigate what had caused the breach.

5. Veeam data breach—Customer records compromised by unprotected database

Near the end of August 2018, the Shodan search engine indexed an Amazon-hosted IP. Bob Diachenko, director of cyber risk research at Hacken.io, came across the IP on 5 September and quickly determined that the IP resolved to a database left unprotected by the lack of a password. The exposed database contained 200 gigabytes worth of data belonging to Veeam, a backup and data recovery company. Among that data were customer records including names, email addresses and some IP addresses.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: Usernames and passwords are a relatively weak way of securing private access. Plus, if an organization does not maintain complete control of the private keys that govern access for internal systems, attackers have a better chance of gaining access.

Impact: Within three hours of learning about the exposure, Veeam took the server offline. The company also reassured TechCrunch that it would “conduct a deeper investigation and… take appropriate actions based on our findings.”

6. Marine Corps data breach—Unencrypted email misfires

At the beginning of 2018, the Defense Travel System (DTS) of the United States Department of Defense (DOD) sent out an unencrypted email with an attachment to the wrong distribution list. The email, which the DTS sent within the usmc.mil official unclassified Marine domain but also to some civilian accounts, exposed the personal information of approximately 21,500 Marines, sailors and civilians. Per Marine Corp Times , the data included victims’ bank account numbers, truncated Social Security Numbers and emergency contact information.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: If organizations are not using proper encryption, cybercriminals can insert themselves between two email servers to intercept and read the email. Sending private personal identity information over unencrypted channels essentially becomes an open invitation to cybercriminals.

Impact: Upon learning of the breach, the Marines implemented email recall procedures to limit the number of email accounts that would receive the email. They also expressed their intention to implement additional security measures going forward.

7. Pennsylvania Department of Education data breach—Misassigned permissions

In February 2018, an employee in Pennsylvania’s Office of Administration committed an error that subsequently affected the state’s Teacher Information Management System (TIMS). As reported by PennLive , the incident temporarily enabled individuals who logged into TIMS to access personal information belonging to other users including teachers, school districts and Department of Education staff. In all, the security event is believed to have affected as many as 360,000 current and retired teachers.

How encryption may become a factor in scenarios like this: I f you do not know who’s accessing your organization’s information, then you’ll never know if it’s being accessed by cybercriminals. Encrypting access to vital information and carefully managing the identities of the machines that house it will help you control access.

Impact: Pennsylvania’s Department of Education subsequently sent out notice letters informing victims that the incident might have exposed their personal information including their Social Security Numbers. It also offered a free one-year subscription for credit monitoring and identity protection services to affected individuals.

How machine identities are misused in a data breach

Human error can impact the success of even the strongest security strategies. As the above attacks illustrate, this can compromise the security of machine identities in numerous ways. Here are just a few:

- SSH keys grant privileged access to many internal systems. Often, these keys do not have expiration dates. And they are difficult to monitor. So, if SSH keys are revealed or compromised, attackers can use them to pivot freely within the network.

- Many phishing attacks leverage wildcard or rogue certificates to create fake sites that appear to be authentic. Such increased sophistication is often required to target higher-level executives.

- Using public-key encryption and authentication in the two-step verification makes it harder to gain malicious access. Easy access to SSH keys stored on computers or servers makes it easier for attackers to pivot laterally within the organization.

- An organization’s encryption is only as good as that of its entire vendor community. If organizations don’t control the keys and certificates that authenticate partner interactions, then they lose control of the encrypted tunnels that carry confidential information between companies.

- If organizations are not monitoring the use of all the keys and certificates that are used in encryption, then attackers can use rogue or stolen keys to create illegitimate encrypted tunnels. Organizations will not be able to detect these malicious tunnels because they appear to be the same as other legitimate tunnels into and out of the organization.

How to avoid data breaches

The best way to avoid a data breach to make sure your organization is using the most effective, up-to-date security tools and technologies. But even the best cybersecurity strategy is not complete unless it is accompanied by security awareness training for all who access and interact with sensitive corporate data.

Because data breaches take many different forms and can happen in a multitude of ways, you need to be ever vigilant and employ a variety of strategies to protect your organization. These should include regular patching and updating of software, encrypting sensitive data, upgrading obsolete machines and enforcing strong credentials and multi-factor authentication.

In particular, a zero-trust architecture will give control and visibility over your users and machines using strategies such as least privileged access, policy enforcement, and strong encryption. Protecting your machine identities as part of your zero trust architecture will take you a long way toward breach prevention. Here are some machine identity management best practices that you should consider:

- Locate all your machine identities. Having a complete list of your machine identities and knowing where they’re all installed, who owns them, and how they’re used will give you the visibility you need to ensure that they are not being misused in an attack.

- Set up and enforce security policies. To keep your machine identities safe, you need security policies that help you control every aspect of machine identities — issuance, use, ownership, management, security, and decommissioning.

- Continuously gather machine identity intelligence. Because the number of machines on your network is constantly changing, you need to maintain intelligence their identities, including the conditions of their use and their environment.

- Automate the machine identity life cycle. Automating he management of certificate requests, issuance, installation, renewals, and replacements helps you avoid error-prone manual actions that may leave your machine identities vulnerable to outage or breach.

- Monitor for anomalous use. After you’ve established a baseline of normal machine identity usage, you can start monitoring and flagging anomalous behavior, which can indicate a machine identity compromise.

- Set up notifications and alerts. Finding and evaluating potential machine identity issues before they exposures is critical. This will help you take immediate action before attackers can take advantage of weak or unprotected machine identities.

- Remediate machine identities that don’t conform to policy. When you discover machine identities that are noncompliant, you must quickly respond to any security incident that requires bulk remediation.

Training your users about the importance of machine identities will help reduce user errors. And advances in AI and RPA will also play a factor in the future. But for now, your best bet in preventing encryption from being misused in an attack on your organization is an automated machine identity management solution that allows you to maintain full visibility and control of your machine identities. Automation will help you reduce the inherent risks of human error as well as maintain greater control over how you enforce security policies for all encrypted communications.

( This post has been updated. It was originally published Posted on October 15, 2020. )

Related posts

- Marriott Data Breach: 500 Million Reasons Why It’s Critical to Protect Machine Identities

- Breaches Are Like Spilled Milk: It Doesn’t Help to Cry

- The Major Data Breaches of 2017: Did Machine Identities Play a Factor?

Machine Identity Security Summit 2024

Help us forge a new era of cybersecurity

☕ We're spilling all the machine identiTEA Oct. 1-3, but these insights are too valuable to just toss in the harbor! Browse the agenda and register now.

- Data Breach

GDPR: Key cases so far

- 7 February 2019

- Data Protection & GDPR

Loretta Maxfield

Google fined by national French data protection regulator

On 21 January, Google LLC (Google’s French arm) was fined €50million by the Commission Nationale de l’information et des Liberties (CNIL) for various failings under GDPR.

The main failing CNIL found was that individuals using Google’s services were not furnished with the requisite “fair processing information” (the information usually provided in privacy notices) by seemingly omitting to inform individuals about why Google processed their personal data how long their data was kept. The ruling also attacked the accessibility of the information saying that although most of the information was there, it was scattered around it site via various different “links”. The second key failing was not meeting the GDPR standard of “consent” when providing personalised advert content. Under GDPR, consent must be sufficiently informed, specific, unambiguous, granular and be gained through a form of active acceptance. In the first instance the CNIL did not consider the consent to be informed enough as it ruled users were not given enough information about what giving their consent would mean in terms of the ad personalisation services Google would then push. The fine was also imposed in light of Google not ensuring that consent met the GDPR threshold through using pre-ticked boxes and not separating out consents for advert personalisation from other processing by Google.

The takeaways for your organisation are to ensure it’s easy for your customers or service users to understand what you do with their data. Privacy notices should be clearly signposted, and be as accurate as possible about what data is collected and why it is used. It also reminds us of the strict threshold consents must reach before they are valid. Businesses are certainly becoming more savvy when it comes to making sure individuals an give consent for different purposes, but it’s not uncommon to still come across the pre-ticked box! If your organisation relies on consent and would like Thorntons to review how you use it, please get in touch and we can give advice on whether you are meeting the GDPR standard.

Marriot International suffer unprecedented data breach

On 19 November last year, Marriott International announced that the personal data of 500 million of its customers had been compromised. The group, which operates hotel chains under the brands W Hotels, Sheraton, and Le Méridien among many others, said that they had reason to believe that certain of their computer systems had been hacked in 2014 which has now led to this breach. The number of people affected, which data relates to customer bookings from 2014 onwards, has now been revised and whilst they still cannot state the exact number, it believes the number of customer records now totals around 383 million. This remains an extremely large number of affected customers, and the hackers were able to access personal details, passport numbers, and in some cases payment information.

Although a breach of this scale is rare, there are various pointers that all organisations can take from this case. Firstly, it’s a reminder to continuously monitor the technical and organisational security measures protecting personal data. Testing and monitoring of your organisation’s security should be subject to regular review. Secondly, it’s a reminder to have in place a practical guide for how to respond to a data breach. As well as having a clear process for how to report and assess breaches internally, your guide should be clear on what kind of breaches should be reported to the ICO, and perhaps statements to release to the media. Lastly, this case is a reminder of conducting regular audits of data held so that your organisation is always aware of how much data it actually holds. Marriott’s reduced forecast of the number of data subjects affected is based on the fact they have now discovered that many of the accounts compromised actually relate to the same individual. If Marriott had an up-to-date list of active customers it potentially could have been able to respond more quickly.

The ICO takes action against organisations for failing to pay the new data protection fee

At the end of September, the ICO announced that it had begun formal enforcement action against organisations for failing to pay the new data protection fee. Since 25th May when GDPR came into force, organisations which are classified as data controllers have been required by the Data Protection (Charges and Information) Regulations 2018 to register with the ICO, and pay the applicable fee. Whilst the specific organisations have not been named, the ICO has confirmed they have issued 900 notices of intent to fine organisations which span “the public and private sector including the NHS, recruitment, finance, government and accounting”. Of those 900, to-date 100 penalty notices have been issued which range from £400 to £4000, although the ICO has confirmed that the maximum could be £4350 depending on aggravating factors. If you are unsure whether your organisation is required to pay a fee, please get in touch and we can advise accordingly.

The ICO issues its first Enforcement Notice for a breach of GDPR

The ICO has issued its first formal notice under the GDPR to AggregateIQ Data Services Ltd (“AIQ”). AIQ, a Canadian company, was involved in targeting political advertising on social media to individuals whose information was supplied to them by various political parties and campaigns (such as Vote Leave, BeLeave, Veterans for Britain, and DUP Vote to Leave).

After an investigation by the ICO, AIQ was found not to have adequately complied with its obligations as a controller under the GDPR by: (1) not processing personal data in a way that the data subjects were aware of, (2) not processing personal data for purposes for which data subjects expected, (3) not having a lawful basis for processing, (4) not processing the personal data in a way in a way which was compatible with the reasons for which it was originally collected, and (5) not issuing the appropriate fair processing information to those individuals (commonly communicated through a privacy notice).

As well as those practical failings, the ICO also considered that it was likely that those individuals whose information was passed to AIQ and used for targeted advertising were likely to cause those individuals damage or distress through not being given the opportunity to understand how their personal information would be used.

The most interesting point about this case is that although the company is based in Canada, the ICO has still exercised its authority over those organisations which process data of those in the UK and ordered that AIQ must now erase all the personal data it holds on individuals in the UK. For a company which mainly deals in data and analytics, this could have a detrimental impact on its business operations in the UK. Although AIQ was passed the personal data from other organisations, this enforcement action demonstrates that it is still AIQ’s responsibility to ensure that their use of the data was not incompatible with any of the purposes for which it was originally intended, and still incumbent on them to ensure individuals were aware of what they were doing with it. In addition, whilst there has been and continues to be a lot of emphasis in the media of the risk of large fines under GDPR, it is notable that no monetary penalty has been issued by the ICO, although the ICO has reserved its ability to do so should AIQ not comply with this notice.

Morrisons held liable for the wrongful acts of its rogue employee by the Court of Appeal (England)

The circumstances of this interesting case centre around an employee whose rogue actions were still considered by the court to be attributable to the employer as a breach of the Data Protection Act 1998. The employee was employed by Morrisons Supermarkets as an internal IT auditor who in 2014, knowingly decided to copy the personal data of around 100,000 of Morrisons’ employees onto a USB stick. At home, the employee then posted the personal data, which included names, addresses and bank details, onto the internet under the name of another Morrisons employee in an attempt to cover his tracks.

In finding that Morrisons was vicariously liable for the actions of the rogue employee, the Court concluded that there was a sufficiently close link between the employee’s job role, and the wrongful action. That the wrongful event occurred outside the workplace was irrelevant, as the Court found that the employee in question was acting “within the field of activities assigned”. Because the employee had access to the compromised personal data in the course of carrying out his role in facilitating payroll, he was specifically entrusted with that kind of information in order to do his job, so the Court decided that there was a sufficient link between the job role and the wrongful disclosure.

The key, striking, message from this case is that it is possible for employers to be held liable for rogue actions taken by its employees. Although this particular employee was obviously not acting within the expected confines of his job role, it is interesting that the Court still determined that employers may be liable for acts that it would normally reasonably consider out of its control. Although this incident occurred in 2014 and therefore decided under the Data Protection Act 1998, this case demonstrates how vital it is that organisations put in place appropriate technical and organisational security measures adequate for the type of data that is being held and also taking into account the risk of disgruntled employees and what they may do with their access to the information. This case also acts as a reminder of ensuring your staff are trained and aware of data protection and the role they personally can play in the protection of data, not just focusing on technical computer security which a lot of organisations pay more attention to. As remarked in this judgment, it also serves as a reminder of having adequate insurance in place in the event of a major data breach.

The ICO receives notification of thousands of breaches

Although organisations could report data breaches to the ICO under the Data Protection Act 1998, you will be aware that under GDPR there is mandatory reporting of breaches to the ICO in cases where there is a “risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals”. The ICO has now reported that it has received notification of more than 8000 breaches in the 6 months since GDPR came into force. Last summer the ICO observed that many breaches that were being reported did not necessarily meet the threshold of risk, however they do welcome the honesty and transparency coming from organisations under legislation which is designed to strengthen rights for individuals.

With breaches requiring to be reported to the ICO within 72 hours of becoming aware, it is vital that mechanisms are in place internally for employees to understand how to report a breach and complete a risk assessment in the appropriate time-frame to assess whether it is reportable. If you would like any help compiling a data breach policy or risk assessment framework tailored to your organisation please get in touch.

Related services

- Data Protection and GDPR

Stay updated

Receive the latest news, legal updates and event information straight to your inbox

About the author

Data Protection & GDPR, Intellectual Property

For more information, contact Loretta Maxfield on +44 1382 346814 .

Make an enquiry

The International Forum for Responsible Media Blog

- Table of Media Law Cases

- About Inforrm

- Search for: Search Button

Top 10 Privacy and Data Protection Cases of 2018: a selection

- Cliff Richard v. The British Broadcasting Corporation [2018] EWHC 1837 (Ch) .

This was Sir Cliff Richard’s privacy claim against the BBC and was the highest profile privacy of the year. The claimant was awarded damages of £210,000. We had a case preview and case reports on each day of the trial and posts from a number of commentators including Paul Wragg , Thomas Bennett ( first and second ), Jelena Gligorijević . The BBC subsequently announced that it would not seek permission to appeal.

- ABC v Telegraph Media Group Ltd [2018] EWCA Civ 2329 .

This was perhaps the second most discussed privacy case of the year. The Court of Appeal allowed the claimants’ appeal and granted an interim injunction to prevent the publication of confidential information about alleged “discreditable conduct” by a high profile executive. Lord Hain subsequently named the executive as Sir Philip Green. We had a case comment from Persephone Bridgman Baker. We also had comments criticising Lord Hain’s conduct from Paul Wragg , Robert Craig and Tom Double .

- Ali v Channel 5 Broadcast ( [2018] EWHC 298 (Ch)) .

The claimants had featured in a “reality TV” programme about bailiffs, “Can’t pay? We’ll Take it Away”. Their claim for misuse of private information was successful and damages of £20,000 were awarded. We had a case comment from Zoe McCallum. An appeal and cross appeal was heard on 4 December 2018 and judgment is awaited.

- NT1 and NT2 v Google Inc [2018] 3 WLR 1165.

This was the first “right to be forgotten” claim in the English Courts – with claims in both data protection and privacy. Both claimants had spent convictions – one was successful and the other not. We had a case preview from Aidan Wills and a comment on the case from Iain Wilson,

- Lloyd v Google LLC [2018] EWHC 2599 (QB) .

This was an attempt to bring a “representative action” in data protection on behalf of all iPhone users in respect of the “Safari Workaround”. The representative claimant was refused permission to serve Google out of the jurisdiction. We had a case comment from Rosalind English. There was a Panopticon Blog post the case. The claimant has been given permission to appeal and it is likely that the appeal will be heard in late 2019.

- TLU v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWCA Civ 2217 .

The Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal in a “data leak” case on the issue of liability to individuals affected by a data leak but not specifically named in the leaked document. We had a case comment from Lorna Skinner and further comment from Iain Wilson. There was also a Panopticon Blog post .

- Stunt v Associated Newspapers [2018] EWCA Civ 170 .

The Court of Appeal referred the question of whether the “journalistic exemption” in section 32(4) of the Data Protection Act 1998 is compatible with the Data Protection Directive and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights to the CJEU. There was a Panopticon Blog post on the case.

- Various Claimants v W M Morrison Supermarkets plc [2018] EWCA Civ 2339 .

The Court of Appeal upheld the decision of Langstaff J that Morrisons were vicariously liable for a mass data breach caused by the criminal act of a rogue employee. We had a case comment from Alex Cochrane. There was a Panopticon Blog post the case.

- Big Brother Watch v. Secretary of State [2018] ECHR 722 .

An important case in which the European Court of Human Rights held that secret surveillance regimes including the bulk interception of external communications violated Articles 8 and 10 of the Convention. We had a post by Graham Smith as to the implications of this decision for the present regime.

- ML and WW v Germany ( [2018] ECHR 554 ).

This was the first case in the European Court of Human Rights on the “right to be forgotten”. This was an application under Article in respect of the historic publication by the media of information concerning a murder conviction. The application was dismissed. We had a case comment from Hugh Tomlinson and Aidan Wills. There was also a Panopticon blog post on the case.

Share this:

Caselaw , Data Protection , Privacy

2018 Top 10 Privacy and Data Protection Cases

January 29, 2019 at 6:25 am

Reblogged this on | truthaholics and commented: “In this post we round up some of the most legally and factually interesting privacy and data protection cases from England and Europe from the past year.”

January 29, 2019 at 9:38 am

Reblogged this on tummum's Blog .

February 2, 2019 at 12:27 am

Very Nice and informative data…keep the good work going on

3 Pingbacks

- Top 10 Privacy and Data Protection Cases of 2020: a selection – Suneet Sharma – Inforrm's Blog

- Top 10 Privacy and Data Protection Cases of 2021: A selection – Suneet Sharma – Inforrm's Blog

- Top 10 Privacy and Data Protection Cases 2022, a selection – Suneet Sharma – Inforrm's Blog

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Contact the Inforrm Blog

Inforrm can be contacted by email [email protected]

Email Subscription

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Sign me up!

Media Law Employment Opportunities

Penningtons Manches Cooper, Paralegal – Commercial Dispute Resolution (Reputation Management & Privacy)

Edwards Duthie Shamash, Media Law Associate, 3 – 5 years PQE

Schillings Senior Associate

Schillings Associate

Good Law Practice, Defamation Lawyer

Brett Wilson, NQ – 4 years’ PQE solicitor

Mishcon de Reya, Associate Reputation Protection, 1-4 PQE

Slateford, NQ – 2 years’ PQE solicitor

- Top 10 Defamation Cases of 2023: a selection - Suneet Sharma

- Case Law: Aaronson v Stones: Libel Trial, truth and the perils of tacking on a public interest defence – Floyd Alexander-Hunt

- Top 10 Defamation Cases 2022: a selection - Suneet Sharma

- Global Freedom of Expression, Columbia University: Newsletter, 12 August 2024

- An exposé of whatever-it-takes culture, Eric Beecher’s The Men Who Killed the News is an idealistic book for the times - Denis Muller

Recent Judgments

- Artificial Intelligence

- Bosnia Herzegovina

- Broadcasting

- Cybersecurity

- Data Protection

- Freedom of expression

- Freedom of Information

- Government and Policy

- Human Rights

- Intellectual Property

- Leveson Inquiry

- Media Regulation

- New Zealand

- Northern Ireland

- Open Justice

- Philippines

- Phone Hacking

- Social Media

- South Africa

- Surveillance

- Uncategorized

- United States

Search Inforrm’s Blog

- Alternative Leveson 2 Project

- Blog Law Online

- Brett Wilson Media Law Blog

- Canadian Advertising and Marketing Law

- Carter-Ruck's News and Insights

- Cearta.ie – The Irish for Rights

- Centre for Internet and Society – Stanford (US)

- Clean up the Internet

- Cyberlaw Clinic Blog

- Cyberleagle

- Czech Defamation Law

- David Banks Media Consultancy

- Defamation Update

- Defamation Watch Blog (Aus)

- Droit et Technologies d'Information (France)

- Fei Chang Dao – Free Speech in China

- Guardian Media Law Page

- Hacked Off Blog

- Information Law and Policy Centre Blog

- Internet & Jurisdiction

- Internet Cases (US)

- Internet Policy Review

- Journlaw (Aus)

- LSE Media Policy Project

- Media Reform Coalition Blog

- Media Report (Dutch)

- Michael Geist – Internet and e-commerce law (Can)

- Musings on Media (South Africa)

- Paul Bernal's Blog

- Press Gazette Media Law

- Scandalous! Field Fisher Defamation Law Blog

- Simon Dawes: Media Theory, History and Regulation

- Social Media Law Bulletin (Norton Rose Fulbright)

- Strasbourg Observers

- Transparency Project

- UK Constitutional Law Association Blog

- Zelo Street

Blogs about Privacy and Data Protection

- Canadian Privacy Law Blog

- Data Matters

- Data protection and privacy global insights – pwc

- DLA Piper Privacy Matters

- Données personnelles (French)

- Europe Data Protection Digest

- Mass Privatel

- Norton Rose Fulbright Data Protection Report

- Panopticon Blog

- Privacy and Data Security Law – Dentons

- Privacy and Information Security Law Blog – Hunton Andrews Kurth

- Privacy Europe Blog

- Privacy International Blog

- Privacy Lives

- Privacy News – Pogo was right

- RPC Privacy Blog

- The Privacy Perspective

Blogs about the Media

- British Journalism Review

- Jon Slattery – Freelance Journalist

- Martin Moore's Blog

- Photo Archive News

Blogs and Websites: General Legal issues

- Carter-Ruck Legal Analysis Blog

- Human Rights in Ireland

- Human Rights Info

- ICLR Case Commentary

- Joshua Rozenberg Facebook

- Law and Other Things (India)

- Letters Blogatory

- Mills and Reeve Technology Law Blog

- Open Rights Group Blog

- RPC's IP Hub

- RPC's Tech Hub

- SCOTUS Blog

- The Court (Canadian SC)

- The Justice Gap

- UK Human Rights Blog

- UK Supreme Court Blog

Court, Government, Regulator and Other Resource Sites

- Australian High Court

- Canadian Supreme Court

- Commonwealth Legal Information Institute

- Cour De Cassation France

- European Data Protection Board

- Full Fact.org

- German Federal Constitutional Court

- IMPRESS Project

- Irish Supreme Court

- New Zealand Supreme Court

- NSW Case Law

- Press Complaints Commission

- Press Council (Australia)

- Press Council (South Africa)

- South African Constitutional Court

- UK Judiciary

- UK Supreme Court

- US Supreme Court

Data Protection Authorities

- Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (in Spanish)

- BfDI (Federal Commissioner for Data Protection)(in German)

- CNIL (France)

- Danish Data Protection Agency

- Data Protection Authority (Belgium)

- Data Protection Commission (Ireland)

- Dutch Data Protection Authority

- Information Commissioner's Office

- Italian Data Protection Authority

- Scottish Information Commissioner

- Swedish Data Protection Authority

Freedom of Expression Blogs and Sites

- Backlash – freedom of sexual expression

- Council of Europe – Freedom of Expression

- EDRi – Protecting Digital Freedom

- Free Word Centre

- Freedom House Freedom of Expression

- Freedom of Expression Institute (South Africa)

- Guardian Freedom of Speech Page

- Index on Censorship

Freedom of Information Blogs and Sites

- All About Information (Can)

- Campaign for Freedom of Information

- David Higgerson

- FreedomInfo.org

- Open and Shut (Aus)

- Open Knowledge Foundation Blog

- The Art of Access (US)

- The FOIA Blog (US)

- The Information Tribunal

- UCL Constitution Unit – FOI Resources

- US Immigration, Freedom of Information Act and Privacy Act Facts

- Veritas – Zimbabwe

- Whatdotheyknow.com

Inactive and Less Active Blogs and Sites

- #pressreform

- Aaronovitch Watch

- Atomic Spin

- Bad Science

- Banksy's Blog

- Brown Moses Blog – The Hackgate Files

- California Defamation Law Blog (US)

- CYB3RCRIM3 – Observations on technology, law and lawlessness.

- Data Privacy Alert

- Defamation Lawyer – Dozier Internet Law

- DemocracyFail

- Entertainment & Media Law Signal (Canada)

- Forty Shades of Grey

- Greenslade Blog (Guardian)

- Head of Legal

- Heather Brooke

- IBA Media Law and Freedom of Expression Blog

- Information and Access (Aus)

- Informationoverlord

- ISP Liability

- IT Law in Ireland

- Journalism.co.uk

- Korean Media Law

- Legal Research Plus

- Lex Ferenda

- Media Law Journal (NZ)

- Media Pal@LSE

- Media Power and Plurality Blog

- Media Standards Trust

- Nied Law Blog

- No Sleep 'til Brooklands

- Press Not Sorry

- Primly Stable

- Responsabilidad En Internet (Spanish)

- Socially Aware

- Story Curve

- Straight Statistics

- Tabloid Watch

- The IT Lawyer

- The Louse and The Flea

- The Media Blog

- The Public Privacy

- The Sun – Tabloid Lies

- The Unruly of Law

- UK FOIA Requests – Spy Blog

- UK Freedom of Information Blog

Journalism and Media Websites

- Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom

- Centre for Law, Justice and Journalism

- Committee to Protect Journalists

- Council of Europe – Platform to promote the protection of journalism and safety of journalists

- ECREA Communication Law and Policy

- Electronic Privacy Information Centre

- Ethical Journalism Network

- European Journalism Centre

- European Journalism Observatory

- Frontline Club

- Hold the Front Page

- International Federation of Journalists

- Journalism in the Americas

- Media Wise Trust

- New Model Journalism – reporting the media funding revolution

- Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press

- Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism

- Society of Editors

- Sports Journalists Association

- Spy Report – Media News (Australia)

- The Hoot – the Media in the Sub-Continent

Law and Media Tweets

- 1stamendment

- DanielSolove

- David Rolph

- FirstAmendmentCenter

- Guardian Media

- Heather Brooke (newsbrooke)

- humanrightslaw

- Internetlaw

- jonslattery

- Kyu Ho Youm's Media Law Tweets

- Leanne O'Donnell

- Media Law Blog Twitter

- Media Law Podcast

- Siobhain Butterworth

Media Law Blogs and Websites

- 5RB Media Case Reports

- Ad IDEM – Canadian Media Lawyers Association

- Entertainment and Sports Law Journal (ESLJ)

- Gazette of Law and Journalism (Australia)

- International Media Lawyers Association

- Legalis.Net – Jurisprudence actualite, droit internet

- Office of Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression – Inter American Commission on Human Rights

- One Brick Court Cases

- Out-law.com

- EthicNet – collection of codes of journalism ethics in Europe

- Handbook of Reuters Journalism

- House of Commons Select Committee for Culture Media and Sport memoranda on press standards, privacy and libel

US Law Blogs and Websites

- Above the Law

- ACLU – Blog of Rights

- Blog Law Blog (US)

- Chilling Effects Weather Reports (US)

- Citizen Media Law Project

- Courthousenews

- Entertainment and Law (US)

- Entertainment Litigation Blog

- First Amendment Center

- First Amendment Coalition (US)

- Free Expression Network (US)

- Internet Cases – a blog about law and technology

- Jurist – Legal News and Research

- Legal As She Is Spoke

- Media Law Prof Blog

- Media Legal Defence Initiative

- Newsroom Law Blog

- Shear on Social Media Law

- Student Press Law Center

- Technology and Marketing Law Blog

- The Hollywood Reporter

- The Public Participation Project (Anti-SLAPP)

- The Thomas Jefferson Centre for the Protection of Free Expression

- The Volokh Conspiracy

US Media Blogs and Websites

- ABA Media and Communications

- Accuracy in Media Blog

- Columbia Journalism Review

- County Fair – a blog from Media Matters (US)

- Fact Check.org

- Media Gazer

- Media Law – a blog about freedom of the press

- Media Matters for America

- Media Nation

- Nieman Journalism Lab

- Pew Research Center's Project for Excellence in Journalism

- Regret the Error

- Reynolds Journalism Institute Blog

- Stinky Journalism.org

- August 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

© 2024 Inforrm's Blog

Theme by Anders Norén — Up ↑

Discover more from Inforrm's Blog

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

The Privacy Perspective

Legal blogging on the protection of privacy in the 21st century, top 10 privacy and data protection cases 2022.

Inforrm covered a wide range of data protection and privacy cases in 2022. Following my posts in 2018 , 2019 , 2020 and 2021 here is my selection of notable privacy and data protection cases across 2022.

- ZXC v Bloomberg [2022] UKSC 5

This was the seminal privacy case of the year, decided by the UK Supreme Court. It was considered whether, in general a person under criminal investigation has, prior to being charged, a reasonable expectation of privacy in respect of information relating to that investigation.

The case concerned ZXC, a regional CEO of a PLC which operated overseas. An article was published concerning the PLC’s operations for which ZXC was responsible. The article’s was almost exclusively focused on the contents of a letter sent to a foreign law enforcement agency by a UK law enforcement agency, which was investigating the PLC’s activities in the region.

ZXC claimed a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to the fact and details of a criminal investigation into his activities, disclosed by the letter, and that the publication of the article by Bloomberg amounted to a misuse of that private information. He argued that details of the law enforcement’s investigations into him, the fact that it believed that he had committed criminal offences and the evidence that was sought were all private.

At first instance Nicklin J found for the claimant, a finding which was upheld by the Court of Appeal. There were three issues before the UK Supreme Court hearing a further appeal by Bloomberg:

(1) Whether the Court of Appeal was wrong to hold that there is a general rule, applicable in the present case, that a person under criminal investigation has, prior to being charged, a reasonable expectation of privacy in respect of information relating to that investigation.

(2) Whether the Court of Appeal was wrong to hold that, in a case in which a claim for breach of confidence was not pursued, the fact that information published by Bloomberg about a criminal investigation originated from a confidential law enforcement document rendered the information private and/or undermined Bloomberg’s ability to rely on the public interest in its disclosure.

(3) Whether the Court of Appeal was wrong to uphold the findings of Nicklin J that the claimant had a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to the published information complained of, and that the article 8/10 balancing exercise came down in favour of the claimant.

The Court dismissed the appeal on all three grounds. Therefore the precedent is established that there is, as a legitimate starting point, an assumption that there is a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to the facts of and facts of a criminal investigation at a pre-charge stage.

There was an Inforrm case comment on the case , See also Panopticon Blog and 5RB case comment.

- Driver v CPS [ 2022] EWHC 2500 (KB )

My second case also concerns law enforcement investigations, this time the passing of a file from the CPS and the disclosure of that fact to a third party. Whilst the disclosure did not include the name of the claimant, it was found that “personal data can relate to more than one person and does not have to relate exclusively to one data subject, particularly when the group referred to is small.”

In this case, the operation in question, Operation Sheridan, concerned only eight suspects, of which the claimant was one. It should be noted that the claim was one under the Data Protection Act 2018, not the GDPR.

In finding for the claimant on the data protection grounds, but dismissing those for misuse of private information, the Judge made a declaration and awarded £250 damages. It should be noted the “data breach was at the lowest end of the spectrum.”

See Panopticon Blog on case

- AB v Chief Constable of British Transport Police [2022] EWHC 2740 (KB)

The respondent, an individual with autistic spectrum disorder of the Asperger’s type, claimed that retention of his information by the police in relation to 2011 and 2014 accusations that he touched women inappropriately, was unlawful. The respondent stims, rubbing fabric between his fingers. In both cases no prosecution was brought against AB.

The respondent’s claim was based on the fact the data retained was inaccurate and that its retention was a disproportionate inference with his right to respect for his private life under Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights.

In December 2017, Bristol County Council was contacted with safeguarding concerns about AB- in particular, that he was suffering ongoing trauma due to the appellant maintaining ongoing false allegations against him.

As to the claims for inaccuracy “he complained that the records retained by the police inaccurately record that AB put his hands between the legs, and under the dress, of the 2011 complainant. He also implicitly complained that the records of the 2014 incident were inaccurate insofar as they suggested that AB had placed his hand over the complainant’s jeans in the area of her vagina.”

It was found at first instance that the police records were inaccurate, that their retention was a disproportionate interference with AB’s article 8 rights and awarded £15,000 for distress, £15,000 for loss of earnings, and £6,000 for aggravated damages.

It was found that “ the police records in this case are intended to reflect the information that was provided to the police, rather than the underlying facts as to what happened. On this issue I have reached a different conclusion from the judge, with the result that I have concluded that the OSRs are accurate. To this narrow extent, the appeal succeeds. ” [95]

However, the article 8 finding for the claimant was upheld, as was, accordingly, the judge’s declaration that retention was unlawful and the assessment of damages.

- Chief Constable of Kent Police v Taylor [2022] EWHC 737 (QB)

A breach of confidence claim relating to a series of videos which the defendant was provided by Berryman’s Lace Mawer LLP (“BLM”). The videos were said to contain sensitive information in relation to a vulnerable minor, KDI, who was the subject of an anonymity order in civil proceedings. The videos themselves were particularly sensitive, relating to police interviews of KDI in relation to criminal allegations against them.

The claimant sued the CC of Kent Police for damage to his front door which occurred in the course of entering his property to search for child pornography. BLM acted for the CC of Kent Police in relation to this matter. During the course of those proceedings that the defendant was given access to the videos, which were for an unrelated claim.

The defendant refused to delete the videos upon request or to explain his dealings with the videos. He instead demanded payment if thousands of pounds for his cooperation with the requests.

The Judge accordingly ordered the defendant disclose matters in relation to his dealing with the videos, to ensure confidentiality has not been breached. A further, unusual, order was granted for independent permanent deletion of the videos- it should be noted the order considered the defendants privacy in the coruse of such an inpdenendent assessment being undertaken with the judge stating “I have built in a safeguard in the order I propose to make to limit the nature of the independent IT expert’s role to protect Mr Taylor’s privacy interests”.

- Various Claimants v MGN [2022] EWHC 1222 (Ch)

A case concerning the ongoing phone hacking litigation against Mirror Group Newspapers (“MGN”) in which MGN issued and served applications for summary judgment in 23 individual claims. The judge grouped the claims, with this judgment considering six claimants.

It was considered by the judge whether claimants should have been put on notice at various times up until and following the first primary trial in the scandal on 21 May 2015. The judge found that such matters were not “clear-cut” for the purposes of determining whether summary judgment could be entered into; they were more appropriate to be settled at trial. There was a comment on the case on the JMW blog . On 11 August 2022 Andrews LJ refused MGN permission to appeal .

- Brake v Guy [2022] EWCA Civ 235

The claimants appealed an order dismissing their claim for a final injunction and damages for misuse of private information and breach of confidence. The claim was made in relation to a series of emails sent to and received by the first claimant, Mrs Brake, into a business general enquiries email account. The Court reviewed whether “the judge’s evaluation of the evidence which led him to conclude that they had no reasonable expectation of privacy in respect of the contents of the enquiries account and that the information was not imparted to the Guy Parties in circumstances which gave rise to an obligation of confidence.”

Only two of the 3,149 tranche of emails were produced for the judge to consider- he was, understandably, not inclined to accept that there was a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to the emails on the basis of those two emails alone. The burden of proof was considered to be “a very substantial hurdle” which the claimants had “fallen well short of surmounting it”.

The arguments for breach of confidence were advanced on the same grounds and dismissed. The judge concluded “the claimants have put forward no argument before this Court which persuades me that the judge was wrong to conclude that the personal information in the enquiries account was not “imparted in circumstances imparting an obligation of confidence.””

The case is instructive as to the method and approach to be taken when claiming there is a reasonable expectation of privacy or obligation of confidence in relation to a high volume of documents. It also provides a tacit reminder of the difficulties over overcoming first instance privacy decisions on appeal. There was a DLA Piper case comment .

- TU and RE v Google LLC [2022] EUECJ C-460/20

A case concerning two claimants applying for the delisting of search results under Article 17 of the GDPR.

The case is instructive as to the pleading of inaccuracy of data in erasure requests- where it arises and where it does, how such a request should be dealt with:

- The case states at [72 and 73]: “where the person who has made a request for de-referencing submits relevant and sufficient evidence capable of substantiating his or her request and of establishing the manifest inaccuracy of the information found in the referenced content or, at the very least, of a part – which is not minor in relation to the content as a whole – of that information, the operator of the search engine is required to accede to that request for de-referencing. The same applies where the data subject submits a judicial decision made against the publisher of the website, which is based on the finding that information found in the referenced content – which is not minor in relation to that content as a whole – is, at least prima facie, inaccurate” , and

- “By contrast, where the inaccuracy of such information found in the referenced content is not obvious, in the light of the evidence provided by the data subject , the operator of the search engine is not required, where there is no such judicial decision, to accede to such a request for de-referencing. Where the information in question is likely to contribute to a debate of public interest, it is appropriate, in the light of all the circumstances of the case, to place particular importance on the right to freedom of expression and of information” .

For further analysis please see the Panopticon Blog’s excellent analysis of this case .

- SMO v TikTok Inc. [2022] EWHC 489 (QB)

The former Children’s Commissioner of England’s case against Tik Tok for data protection infringements and misuse of private information was discontinued this year. The result was due to the myriad of procedural issues arising in relation to the case including permission to serve out of jurisdiction, extension of time and permission to serve on UK lawyers instead. The case serves as a warning for claimants seeing to issue data protection claims outside of the jurisdiction of ensuring it is done so in proper time and with consideration of matters such as service outside of jurisdiction.

See Panopticon Blog on case and on the discontinuance of the claim .

- Smith & Other v TalkTalk Telecom Group Plc [2022] EWHC 1311 (QB)

A claim under the Data Protection Act 1998 and tort of misuse of private information, following a mass data breach. The case concerned three applications:

- For strike out of the misuse of private information claim and references to unconfirmed breaches in the particulars;

- For permission to amend the particulars of claim in light of the case Warren v DSG Retail Ltd [2021] EWHC 2168 (QB); and

- An application for further information.

The misuse of private information claim was dismissed. Although the claim had been repleaded to focus on “acts” rather than “omissions” (in an attempt to avoid the consequences of the Warren decision), the Judge followed his own decision in Warren, holding that the action was, in substance, a claim in negligence and that creating a situation of vulnerability to third party data theft was not a claim in missue of private information. There was an Inforrm post on the case and a two part discussion of the issues here and here . See also the Panopticon Blog on case .

This case was the final nail in the coffin of mass data breach claims on CFAs supported by ATE insurance (as these are not available in data protection cases). Unless forming part of group litigation, data breach claims are likely to be transferred to the small claims track (see Stadler v Currys Group Limited [2022] EWHC 160 (QB) ).

- Owsianik v. Equifax Canada Co. , 2022 ONCA 813

An appeal arising out of three separate class actions in which the plaintiffs sought to apply the tort of inclusion upon seclusion in “data breach” cases. The Ontario Court of Appeal held that on the facts as pleaded, the defendants did not do anything that could constitute an act of intrusion or invasion into the privacy of the plaintiffs. The intrusions alleged were committed by unknown third-party hackers, acting independently from, and to the detriment of, the interests of the defendants. The defendants’ alleged fault was their failure to protect the plaintiffs by unknown hackers which could not be transformed into an invasion by the defendants of the plaintiffs’ privacy.

This decision in Ontario is consistent with the approach of the English court in Case No.9. There were case comments by Blakes and McCarthy Tetrault.

Share this:

3 thoughts on “ top 10 privacy and data protection cases 2022 ”.

- Pingback: Quotes from caselaw 7: Driver v CPS [2022] EWHC 2500 KB – a departure from the starting point of a reasonable expectation of privacy in criminal investigations pre-charge on “special facts” and low value data breaches – The Privacy

- Pingback: Remote visual support and data privacy compliance | ViiBE

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Reed Smith LLP

10 January 2023 Reed Smith In-depth

Data, distress, and damage: UK data protection and privacy case law in 2022

Authors: Elle Todd Jonathan J. Andrews

Stadler v. Currys Group Limited [2022] EWHC 160 (QB)

This long-running case concerned claims brought against Currys Group Limited (Currys). Currys sold Mr Stadler’s used smart TV to a third party (after he had returned it to Currys without logging out of various installed apps), resulting in a movie being purchased through Mr Stadler’s Amazon Prime account. Despite Currys reimbursing him the balance (£3.49) and giving him a £200 goodwill voucher, Mr Stadler chose to pursue Currys for misuse of private information, breach of confidence, negligence and breaches of the UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA 2018), seeking damages totalling £5,000.

It was held that:

- In line with the decision in Lloyd v. Google that damages for non-trivial breaches were not recoverable under the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA 1998) unless there was proof of material damage (or distress), the same “appeared to apply equally” to equivalent claims under the UK GDPR; and that, per Rolfe & Ors v. Veale Wasbrough Vizards LLP [2021] EWHC 2809, a de minimis threshold needed to be passed before claims for distress alone could be successfully brought. Consequently, these claims were dismissed.

- Following case law such as Warren v. DSG Retail Ltd [2021] EWHC 2168 ( Warren v. DSG ), the High Court was not the appropriate forum for low-value data claims, with Lewis J also criticising attempts to overcomplicate what was at its heart a simple claim in order to justify this.

- Upholding the precedents set in Warren v. DSG , the claims for misuse of private information and breach of confidence were struck out (as these must involve active “use” or “misuse” of information by a defendant, not just omissions), as was the claim for negligence (given that, where statutory duties are in place, there is no need to impose a duty of care).

Key takeaways:

- The judgment provides precedent for applying Lloyd v. Google’s requirements for bringing a successful compensation claim under the DPA 1998 to equivalent claims under the UK GDPR (though unlike Lloyd v. Google, this is not a Supreme Court case and so higher courts could rule otherwise in future).

- The judgment also supports the precedent set by Rolfe & Ors v. Veale Wasbrough Vizards LLP [2021] EWHC 2809 regarding de minimis thresholds for distress claims (as an aside, a similar decision has also been reached preliminarily in the EU by Advocate General Campos Sanchez-Bordona in the CJEU case of UI v. Österreichische Post AG (Case C-300-21) in October 2022, holding that harm alleged in data breach claims must go beyond “mere upset” to be actionable).

- Attempts to ‘augment’ what should be a clear claim for breach of data protection law with various other heads of claim are even less likely to be successful, with multiple decisions now finding against this practice. This also further limits the recovery of after-the-event (ATE) insurance premiums, which had been common for claimants in low-value data claims typically for breach of confidence and misuse of private information claims, to cover their costs and to pressure defendants into settling (and into paying more money to settle) by having to factor in ATE premiums when considering their costs liability – and as such premiums may well no longer be recoverable in such cases, claimants will need to give more thought to purchasing this, which may well reduce the number of similar claims brought in practice.

- Further increases the likelihood of similar claims, which have often recently been commenced in the Media and Communications Claims List of the High Court, instead being allocated/re-allocated to the small claims track of the relevant county court (where it is not generally possible to recover costs).

Bloomberg LP (Appellant) v. ZXC (Respondent) [2022] UKSC 5

In this case, Bloomberg LP (Bloomberg) obtained a confidential letter of request sent to ZXC by a legal enforcement body regarding a criminal investigation and published an article that referred to the fact that information had been requested of ZXC and the issues it was being investigated for. ZXC succeeded in a High Court claim for misuse of private information against Bloomberg, which Bloomberg appealed first to the Court of Appeal (which was dismissed) and then to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court held that ZXC had a reasonable expectation of privacy in a police investigation up to the point of charge and that, in this case, the right to freedom of expression did not outweigh this. Consequently, it found in favour of ZXC’s claim, awarded it £25,000 in damages, and granted an injunction preventing Bloomberg from publishing its article of the information in question further within the jurisdiction.

- Amongst a range of case law this year emphasising the dangers of pursuing claims for misuse of private information without sufficient grounds, this case is a useful reminder that, in the right circumstances, misuse of private information claims can still be successfully brought – and may also require the payment of non-trivial damages sums.

- The Supreme Court also noted (with respect to comments made by the Court of Appeal) that, although information may be both private and confidential, the causes of action for misuse of private information and breach of confidence are distinct. It will be interesting to see how this affects claims in which both heads of claim are pursued (and particularly where both are brought alongside further claims and without clearly differentiating between the grounds for each different head of claim).