Child Growth and Development

(13 reviews)

Jennifer Paris

Antoinette Ricardo

Dawn Rymond

Alexa Johnson

Copyright Year: 2018

Last Update: 2019

Publisher: College of the Canyons

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Joanne Leary, adjunct faculty, North Shore Community College on 6/9/24

Child Growth and Development is a text that can be seamlessly used to accompany any Child Development Course Pre-birth through Adolescence. The material lays the foundation for understanding development along with the many theorists that paved... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Child Growth and Development is a text that can be seamlessly used to accompany any Child Development Course Pre-birth through Adolescence. The material lays the foundation for understanding development along with the many theorists that paved the way to notice how genetics, environment, culture, family and experience impact growth and development.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

This text has an emphasis on object and sound development and best practices to support development.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

Content includes the latest research and best practices in the field. It gives the reader a sense of what is current in the field and notices current trends.

Clarity rating: 5

The Chapters begin with objectives and an introduction and end with a conclusion of key concepts addressed. Within the Chapters are found material bringing the theory and best practice to life.

Consistency rating: 5

The Chapters begin with objectives and an introduction and end with a conclusion of key concepts addressed. Physical Development, Cognitive Development and Social Emotional Development are covered in-depth for each age group. The format becomes predictable and familiar as the Chapters are read.

Modularity rating: 5

Each Chapter follows a familiar pattern. Each developmental domain within each age category has easy to follow information. The book also includes mini-lectures and powerpoint presentations to support the reading material.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The early Chapters are outlined to give background information about the history of Child Development and factors effecting the family before birth. From Chapter 3 through the remainder of the text attention is given chronologically to each age group and developmental domain within each age category through Adolescence.

Interface rating: 5

The organization of the text is both linear and spiraling. Material covered in one Chapter is often seen again in later Chapters with more in-depth information.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

Throughout the text an effort is clearly made to limit educational jargon and keep the language accessible to all readers.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The Chapters include relevant information about current topics, resources and pictures representing the diverse backgrounds of children and families that are in our classrooms and communities.

Child Growth and Development is a text that can be seamlessly used to accompany any Child Development Course Pre-birth through Adolescence. The material lays the foundation for understanding development along with the many theorists that paved the way to notice how genetics, environment, culture, family and experience impact growth and development. The organization of the text is both linear and spiraling. The early Chapters are outlined to give background information about the history of Child Development and factors effecting the family before birth. From Chapter 3 through the remainder of the text attention is given chronologically to each age group and developmental domain within each age category through Adolescence. Physical Development, Cognitive Development and Social Emotional Development are covered in-depth for each age group. The Chapters begin with objectives and an introduction and end with a conclusion of key concepts addressed. Each Chapters also include relevant information about current topics, resources and pictures representing the diverse backgrounds of children and families that are in our classrooms and communities.

Reviewed by Mistie Potts, Assistant Professor, Manchester University on 11/22/22

This text covers some topics with more detail than necessary (e.g., detailing infant urination) yet it lacks comprehensiveness in a few areas that may need revision. For example, the text discusses issues with vaccines and offers a 2018 vaccine... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This text covers some topics with more detail than necessary (e.g., detailing infant urination) yet it lacks comprehensiveness in a few areas that may need revision. For example, the text discusses issues with vaccines and offers a 2018 vaccine schedule for infants. The text brushes over “commonly circulated concerns” regarding vaccines and dispels these with statements about the small number of antigens a body receives through vaccines versus the numerous antigens the body normally encounters. With changes in vaccines currently offered, shifting CDC viewpoints on recommendations, and changing requirements for vaccine regulations among vaccine producers, the authors will need to revisit this information to comprehensively address all recommended vaccines, potential risks, and side effects among other topics in the current zeitgeist of our world.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

At face level, the content shared within this book appears accurate. It would be a great task to individually check each in-text citation and determine relevance, credibility and accuracy. It is notable that many of the citations, although this text was updated in 2019, remain outdated. Authors could update many of the in-text citations for current references. For example, multiple in-text citations refer to the March of Dimes and many are dated from 2012 or 2015. To increase content accuracy, authors should consider revisiting their content and current citations to determine if these continue to be the most relevant sources or if revisions are necessary. Finally, readers could benefit from a reference list in this textbook. With multiple in-text citations throughout the book, it is surprising no reference list is provided.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

This text would be ideal for an introduction to child development course and could possibly be used in a high school dual credit or beginning undergraduate course or certificate program such as a CDA. The outdated citations and formatting in APA 6th edition cry out for updating. Putting those aside, the content provides a solid base for learners interested in pursuing educational domains/careers relevant to child development. Certain issues (i.e., romantic relationships in adolescence, sexual orientation, and vaccination) may need to be revisited and updated, or instructors using this text will need to include supplemental information to provide students with current research findings and changes in these areas.

Clarity rating: 4

The text reads like an encyclopedia entry. It provides bold print headers and brief definitions with a few examples. Sprinkled throughout the text are helpful photographs with captions describing the images. The words chosen in the text are relatable to most high school or undergraduate level readers and do not burden the reader with expert level academic vocabulary. The layout of the text and images is simple and repetitive with photographs complementing the text entries. This allows the reader to focus their concentration on comprehension rather than deciphering a more confusing format. An index where readers could go back and search for certain terms within the textbook would be helpful. Additionally, a glossary of key terms would add clarity to this textbook.

Chapters appear in a similar layout throughout the textbook. The reader can anticipate the flow of the text and easily identify important terms. Authors utilized familiar headings in each chapter providing consistency to the reader.

Modularity rating: 4

Given the repetitive structure and the layout of the topics by developmental issues (physical, social emotional) the book could be divided into sections or modules. It would be easier if infancy and fetal development were more clearly distinct and stages of infant development more clearly defined, however the book could still be approached in sections or modules.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The text is organized in a logical way when we consider our own developmental trajectories. For this reason, readers learning about these topics can easily relate to the flow of topics as they are presented throughout the book. However, when attempting to find certain topics, the reader must consider what part of development that topic may inhabit and then turn to the portion of the book aligned with that developmental issue. To ease the organization and improve readability as a reference book, authors could implement an index in the back of the book. With an index by topic, readers could quickly turn to pages covering specific topics of interest. Additionally, the text structure could be improved by providing some guiding questions or reflection prompts for readers. This would provide signals for readers to stop and think about their comprehension of the material and would also benefit instructors using this textbook in classroom settings.

Interface rating: 4

The online interface for this textbook did not hinder readability or comprehension of the text. All information including photographs, charts, and diagrams appeared to be clearly depicted within this interface. To ease reading this text online authors should create a live table of contents with bookmarks to the beginning of chapters. This book does not offer such links and therefore the reader must scroll through the pdf to find each chapter or topic.

No grammatical errors were found in reviewing this textbook.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

Cultural diversity is represented throughout this text by way of the topics described and the images selected. The authors provide various perspectives that individuals or groups from multiple cultures may resonate with including parenting styles, developmental trajectories, sexuality, approaches to feeding infants, and the social emotional development of children. This text could expand in the realm of cultural diversity by addressing current issues regarding many of the hot topics in our society. Additionally, this textbook could include other types of cultural diversity aside from geographical location (e.g., religion-based or ability-based differences).

While this text lacks some of the features I would appreciate as an instructor (e.g., study guides, review questions, prompts for critical thinking/reflection) and it does not contain an index or glossary, it would be appropriate as an accessible resource for an introduction to child development. Students could easily access this text and find reliable and easily readable information to build basic content knowledge in this domain.

Reviewed by Caroline Taylor, Instructor, Virginia Tech on 12/30/21

Each chapter is comprehensively described and organized by the period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped together, they are logically organized and discussed within each chapter. One helpful addition that would largely... read more

Each chapter is comprehensively described and organized by the period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped together, they are logically organized and discussed within each chapter. One helpful addition that would largely contribute to the comprehensiveness is a glossary of terms at the end of the text.

From my reading, the content is accurate and unbiased. However, it is difficult to confidently respond due to a lack of references. It is sometimes clear where the information came from, but when I followed one link to a citation the link was to another textbook. There are many citations embedded within the text, but it would be beneficial (and helpful for further reading) to have a list of references at the end of each chapter. The references used within the text are also older, so implementing updated references would also enhance accuracy. If used for a course, instructors will need to supplement the textbook readings with other materials.

This text can be implemented for many semesters to come, though as previously discussed, further readings and updated materials can be used to supplement this text. It provides a good foundation for students to read prior to lectures.

This text is unique in its writing style for a textbook. It is written in a way that is easily accessible to students and is also engaging. The text doesn't overly use jargon or provide complex, long-winded examples. The examples used are clear and concise. Many key terms are in bold which is helpful to the reader.

For the terms that are in bold, it would be helpful to have a definition of the term listed separately on the page within the side margins, as well as include the definition in a glossary at the end.

Each period of development is consistently described by first addressing physical development, cognitive development, and then social-emotional development.

This text is easily divisible to assign to students. There were few (if any) large blocks of texts without subheadings, graphs, or images. This feature not only improves modularity but also promotes engagement with the reading.

The organization of the text flows logically. I appreciate the order of the topics, which are clearly described in the first chapter by each period of development. Although infancy and toddlerhood are grouped into one period of development, development is appropriately described for both infants and toddlers. Key theories are discussed for infants and toddlers and clearly presented for the appropriate age.

There were no significant interface issues. No images or charts were distorted.

It would be helpful to the reader if the table of contents included a navigation option, but this doesn't detract from the overall interface.

I did not see any grammatical errors.

This text includes some cultural examples across each area of development, such as differences in first words, parenting styles, personalities, and attachments styles (to list a few). The photos included throughout the text are inclusive of various family styles, races, and ethnicities. This text could implement more cultural components, but does include some cultural examples. Again, instructors can supplement more cultural examples to bolster the reading.

This text is a great introductory text for students. The text is written in a fun, approachable way for students. Though the text is not as interactive (e.g., further reading suggestions, list of references, discussion points at the end of each chapter, etc.), this is a great resource to cover development that is open access.

Reviewed by Charlotte Wilinsky, Assistant Professor of Psychology, Holyoke Community College on 6/29/21

This text is very thorough in its coverage of child and adolescent development. Important theories and frameworks in developmental psychology are discussed in appropriate depth. There is no glossary of terms at the end of the text, but I do not... read more

This text is very thorough in its coverage of child and adolescent development. Important theories and frameworks in developmental psychology are discussed in appropriate depth. There is no glossary of terms at the end of the text, but I do not think this really hurts its comprehensiveness.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

The citations throughout the textbook help to ensure its accuracy. However, the text could benefit from additional references to recent empirical studies in the developmental field.

It seems as if updates to this textbook will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement given how well organized the text is and its numerous sections and subsections. For example, a recent narrative review was published on the effects of corporal punishment (Heilmann et al., 2021). The addition of a reference to this review, and other more recent work on spanking and other forms of corporal punishment, could serve to update the text's section on spanking (pp. 223-224; p. 418).

The text is very clear and easily understandable.

Consistency rating: 4

There do not appear to be any inconsistencies in the text. The lack of a glossary at the end of the text may be a limitation in this area, however, since glossaries can help with consistent use of language or clarify when different terms are used.

This textbook does an excellent job of dividing up and organizing its chapters. For example, chapters start with bulleted objectives and end with a bulleted conclusion section. Within each chapter, there are many headings and subheadings, making it easy for the reader to methodically read through the chapter or quickly identify a section of interest. This would also assist in assigning reading on specific topics. Additionally, the text is broken up by relevant photos, charts, graphs, and diagrams, depending on the topic being discussed.

This textbook takes a chronological approach. The broad developmental stages covered include, in order, birth and the newborn, infancy and toddlerhood, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence. Starting with the infancy and toddlerhood stage, physical, cognitive, and social emotional development are covered.

There are no interface issues with this textbook. It is easily accessible as a PDF file. Images are clear and there is no distortion apparent.

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

This text does a good job of including content relevant to different cultures and backgrounds. One example of this is in the "Cultural Influences on Parenting Styles" subsection (p. 222). Here the authors discuss how socioeconomic status and cultural background can affect parenting styles. Including references to specific studies could further strengthen this section, and, more broadly, additional specific examples grounded in research could help to fortify similar sections focused on cultural differences.

Overall, I think this is a terrific resource for a child and adolescent development course. It is user-friendly and comprehensive.

Reviewed by Lois Pribble, Lecturer, University of Oregon on 6/14/21

This book provides a really thorough overview of the different stages of development, key theories of child development and in-depth information about developmental domains. read more

This book provides a really thorough overview of the different stages of development, key theories of child development and in-depth information about developmental domains.

The book provides accurate information, emphasizes using data based on scientific research, and is stated in a non-biased fashion.

The book is relevant and provides up-to-date information. There are areas where updates will need to be made as research and practices change (e.g., autism information), but it is written in a way where updates should be easy to make as needed.

The book is clear and easy to read. It is well organized.

Good consistency in format and language.

It would be very easy to assign students certain chapters to read based on content such as theory, developmental stages, or developmental domains.

Very well organized.

Clear and easy to follow.

I did not find any grammatical errors.

General content related to culture was infused throughout the book. The pictures used were of children and families from a variety of cultures.

This book provides a very thorough introduction to child development, emphasizing child development theories, stages of development, and developmental domains.

Reviewed by Nancy Pynchon, Adjunct Faculty, Middlesex Community College on 4/14/21

Overall this textbook is comprehensive of all aspects of children's development. It provided a brief introduction to the different relevant theorists of childhood development . read more

Overall this textbook is comprehensive of all aspects of children's development. It provided a brief introduction to the different relevant theorists of childhood development .

Most of the information is accurately written, there is some outdated references, for example: Many adults can remember being spanked as a child. This method of discipline continues to be endorsed by the majority of parents (Smith, 2012). It seems as though there may be more current research on parent's methods of discipline as this information is 10 years old. (page 223).

The content was current with the terminology used.

Easy to follow the references made in the chapters.

Each chapter covers the different stages of development and includes the theories of each stage with guided information for each age group.

The formatting of the book makes it reader friendly and easy to follow the content.

Very consistent from chapter to chapter.

Provided a lot of charts and references within each chapter.

Formatted and written concisely.

Included several different references to diversity in the chapters.

There was no glossary at the end of the book and there were no vignettes or reflective thinking scenarios in the chapters. Overall it was a well written book on child development which covered infancy through adolescents.

Reviewed by Deborah Murphy, Full Time Instructor, Rogue Community College on 1/11/21

The text is excellent for its content and presentation. The only criticism is that neither an index nor a glossary are provided. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text is excellent for its content and presentation. The only criticism is that neither an index nor a glossary are provided.

The material seems very accurate and current. It is well written. It is very professionally done and is accessible to students.

This text addresses topics that will serve this field in positive ways that should be able to address the needs of students and instructors for the next several years.

Complex concepts are delivered accurately and are still accessible for students . Figures and tables complement the text . Terms are explained and are embedded in the text, not in a glossary. I do think indices and glossaries are helpful tools. Terminology is highlighted with bold fonts to accentuate definitions.

Yes the text is consistent in its format. As this is a text on Child Development it consistently addresses each developmental domain and then repeats the sequence for each age group in childhood. It is very logically presented.

Yes this text is definitely divisible. This text addresses development from conception to adolescents. For the community college course that my department wants to use it is very adaptable. Our course ends at middle school age development; our courses are offered on a quarter system. This text is adaptable for the content and our term time schedule.

This text book flows very clearly from Basic principles to Conception. It then divides each stage of development into Physical, Cognitive and Social Emotional development. Those concepts and information are then repeated for each stage of development. e.g. Infants and Toddler-hood, Early Childhood, and Middle Childhood. It is very clearly presented.

It is very professionally presented. It is quite attractive in its presentation .

I saw no errors

The text appears to be aware of being diverse and inclusive both in its content and its graphics. It discusses culture and represents a variety of family structures representing contemporary society.

It is wonderfully researched. It will serve our students well. It is comprehensive and constructed very well. I have enjoyed getting familiar with this text and am looking forward to using it with my students in this upcoming term. The authors have presented a valuable, well written book that will be an addition to our field. Their scholarly efforts are very apparent. All of this text earns high grades in my evaluation. My only criticism is, as mentioned above, is that there is not a glossary or index provided. All citations are embedded in the text.

Reviewed by Ida Weldon, Adjunct Professor, Bunker Hill Community College on 6/30/20

The overall comprehensiveness was strong. However, I do think some sections should have been discussed with more depth read more

The overall comprehensiveness was strong. However, I do think some sections should have been discussed with more depth

Most of the information was accurate. However, I think more references should have been provided to support some claims made in the text.

The material appeared to be relevant. However, it did not provide guidance for teachers in addressing topics of social justice, equality that most children will ask as they try to make sense of their environment.

The information was presented (use of language) that added to its understand-ability. However, I think more discussions and examples would be helpful.

The text appeared to be consistent. The purpose and intent of the text was understandable throughout.

The text can easily be divided into smaller reading sections or restructured to meet the needs of the professor.

The organization of the text adds to its consistency. However, some sections can be included in others decreasing the length of the text.

Interface issues were not visible.

The text appears to be free of grammatical errors.

While cultural differences are mentioned, more time can be given to helping teachers understand and create a culturally and ethnically focused curriculum.

The textbook provides a comprehensive summary of curriculum planing for preschool age children. However, very few chapters address infant/toddlers.

Reviewed by Veronica Harris, Adjunct Faculty, Northern Essex Community College on 6/28/20

This text explores child development from genetics, prenatal development and birth through adolescence. The text does not contain a glossary. However, the Index is clear. The topics are sequential. The text addresses the domains of physical,... read more

This text explores child development from genetics, prenatal development and birth through adolescence. The text does not contain a glossary. However, the Index is clear. The topics are sequential. The text addresses the domains of physical, cognitive and social emotional development. It is thorough and easy to read. The theories of development are inclusive to give the reader a broader understanding on how the domains of development are intertwined. The content is comprehensive, well - researched and sequential. Each chapter begins with the learning outcomes for the upcoming material and closes with an outline of the topics covered. Furthermore, a look into the next chapter is discussed.

The content is accurate, well - researched and unbiased. An historical context is provided putting content into perspective for the student. It appears to be unbiased.

Updated and accurate research is evidenced in the text. The text is written and organized in such a way that updates can be easily implemented. The author provides theoretical approaches in the psychological domains with examples along with real - life scenarios providing meaningful references invoking understanding by the student.

The text is written with clarity and is easily understood. The topics are sequential, comprehensive and and inclusive to all students. This content is presented in a cohesive, engaging, scholarly manner. The terminology used is appropriate to students studying Developmental Psychology spanning from birth through adolescents.

The book's approach to the content is consistent and well organized. . Theoretical contexts are presented throughout the text.

The text contains subheadings chunking the reading sections which can be assigned at various points throughout the course. The content flows seamlessly from one idea to the next. Written chronologically and subdividing each age span into the domains of psychology provides clarity without overwhelming the reader.

The book begins with an overview of child development. Next, the text is divided logically into chapters which focus on each developmental age span. The domains of each age span are addressed separately in subsequent chapters. Each chapter outlines the chapter objectives and ends with an outline of the topics covered and share an idea of what is to follow.

Pages load clearly and consistently without distortion of text, charts and tables. Navigating through the pages is met with ease.

The text is written with no grammatical or spelling errors.

The text did not present with biases or insensitivity to cultural differences. Photos are inclusive of various cultures.

The thoroughness, clarity and comprehensiveness promote an approach to Developmental Psychology that stands alongside the best of texts in this area. I am confident that this text encompasses all the required elements in this area.

Reviewed by Kathryn Frazier, Assistant Professor, Worcester State University on 6/23/20

This is a highly comprehensive, chronological text that covers genetics and conception through adolescence. All major topics and developmental milestones in each age range are given adequate space and consideration. The authors take care to... read more

This is a highly comprehensive, chronological text that covers genetics and conception through adolescence. All major topics and developmental milestones in each age range are given adequate space and consideration. The authors take care to summarize debates and controversies, when relevant and include a large amount of applied / practical material. For example, beyond infant growth patterns and motor milestone, the infancy/toddler chapters spend several pages on the mechanics of car seat safety, best practices for introducing solid foods (and the rationale), and common concerns like diaper rash. In addition to being generally useful information for students who are parents, or who may go on to be parents, this text takes care to contextualize the psychological research in the lived experiences of children and their parents. This is an approach that I find highly valuable. While the text does not contain an index, the search & find capacity of OER to make an index a deal-breaker for me.

The text includes accurate information that is well-sourced. Relevant debates, controversies and historical context is also provided throughout which results in a rich, balanced text.

This text provides an excellent summary of classic and updated developmental work. While the majority of the text is skewed toward dated, classic work, some updated research is included. Instructors may wish to supplement this text with more recent work, particularly that which includes diverse samples and specifically addresses topics of class, race, gender and sexual orientation (see comment below regarding cultural aspects).

The text is written in highly accessible language, free of jargon. Of particular value are the many author-generated tables which clearly organize and display critical information. The authors have also included many excellent figures, which reinforce and visually organize the information presented.

This text is consistent in its use of terminology. Balanced discussion of multiple theoretical frameworks are included throughout, with adequate space provided to address controversies and debates.

The text is clearly organized and structured. Each chapter is self-contained. In places where the authors do refer to prior or future chapters (something that I find helps students contextualize their reading), a complete discussion of the topic is included. While this may result in repetition for students reading the text from cover to cover, the repetition of some content is not so egregious that it outweighs the benefit of a flexible, modular textbook.

Excellent, clear organization. This text closely follows the organization of published textbooks that I have used in the past for both lifespan and child development. As this text follows a chronological format, a discussion of theory and methods, and genetics and prenatal growth is followed by sections devoted to a specific age range: infancy and toddlerhood, early childhood (preschool), middle childhood and adolescence. Each age range is further split into three chapters that address each developmental domain: physical, cognitive and social emotional development.

All text appears clearly and all images, tables and figures are positioned correctly and free of distortion.

The text contains no spelling or grammatical errors.

While this text provides adequate discussion of gender and cross-cultural influences on development, it is not sufficient. This is not a problem unique to this text, and is indeed a critique I have of all developmental textbooks. In particular, in my view this text does not adequately address the role of race, class or sexual orientation on development.

All in all, this is a comprehensive and well-written textbook that very closely follows the format of standard chronologically-organized child development textbooks. This is a fantastic alternative for those standard texts, with the added benefit of language that is more accessible, and content that is skewed toward practical applications.

Reviewed by Tony Philcox, Professor, Valencia College on 6/4/20

The subject of this book is Child Growth and Development and as such covers all areas and ideas appropriate for this subject. This book has an appropriate index. The author starts out with a comprehensive overview of Child Development in the... read more

The subject of this book is Child Growth and Development and as such covers all areas and ideas appropriate for this subject. This book has an appropriate index. The author starts out with a comprehensive overview of Child Development in the Introduction. The principles of development were delineated and were thoroughly presented in a very understandable way. Nine theories were presented which gave the reader an understanding of the many authors who have contributed to Child Development. A good backdrop to start a conversation. This book discusses the early beginnings starting with Conception, Hereditary and Prenatal stages which provides a foundation for the future developmental stages such as infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence. The three domains of developmental psychology – physical, cognitive and social emotional are entertained with each stage of development. This book is thoroughly researched and is written in a way to not overwhelm. Language is concise and easily understood.

This book is a very comprehensive and detailed account of Child Growth and Development. The author leaves no stone unturned. It has the essential elements addressed in each of the developmental stages. Thoroughly researched and well thought out. The content covered was accurate, error-free and unbiased.

The content is very relevant to the subject of Child Growth and Development. It is comprehensive and thoroughly researched. The author has included a number of relevant subjects that highlight the three domains of developmental psychology, physical, cognitive and social emotional. Topics are included that help the student see the relevancy of the theories being discussed. Any necessary updates along the way will be very easy and straightforward to insert.

The text is easily understood. From the very beginning of this book, the author has given the reader a very clear message that does not overwhelm but pulls the reader in for more information. The very first chapter sets a tone for what is to come and entices the reader to learn more. Well organized and jargon appropriate for students in a Developmental Psychology class.

This book has all the ingredients necessary to address Child Growth and Development. Even at the very beginning of the book the backdrop is set for future discussions on the stages of development. Theorists are mentioned and embellished throughout the book. A very consistent and organized approach.

This book has all the features you would want. There are textbooks that try to cover too much in one chapter. In this book the sections are clearly identified and divided into smaller and digestible parts so the reader can easily comprehend the topic under discussion. This book easily flows from one subject to the next. Blocks of information are being built, one brick on top of another as you move through the domains of development and the stages of development.

This book starts out with a comprehensive overview in the introduction to child development. From that point forward it is organized into the various stages of development and flows well. As mentioned previously the information is organized into building blocks as you move from one stage to the next.

The text does not contain any significant interface issued. There are no navigation problems. There is nothing that was detected that would distract or confuse the reader.

There are no grammatical errors that were identified.

This book was not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way.

This book is clearly a very comprehensive approach to Child Growth and Development. It contains all the essential ingredients that you would expect in a discussion on this subject. At the very outset this book went into detail on the principles of development and included all relevant theories. I was never left with wondering why certain topics were left out. This is undoubtedly a well written, organized and systematic approach to the subject.

Reviewed by Eleni Makris, Associate Professor, Northeastern Illinois University on 5/6/20

This book is organized by developmental stages (infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence). The book begins with an overview of conception and prenatal human development. An entire chapter is devoted to birth and... read more

This book is organized by developmental stages (infancy, toddler, early childhood, middle childhood and adolescence). The book begins with an overview of conception and prenatal human development. An entire chapter is devoted to birth and expectations of newborns. In addition, there is a consistency to each developmental stage. For infancy, early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence, the textbook covers physical development, cognitive development, and social emotional development for each stage. While some textbooks devote entire chapters to themes such as physical development, cognitive development, and social emotional development and write about how children change developmentally in each stage this book focuses on human stages of development. The book is written in clear language and is easy to understand.

There is so much information in this book that it is a very good overview of child development. The content is error-free and unbiased. In some spots it briefly introduces multicultural traditions, beliefs, and attitudes. It is accurate for the citations that have been provided. However, it could benefit from updating to research that has been done recently. I believe that if the instructor supplements this text with current peer-reviewed research and organizations that are implementing what the book explains, this book will serve as a strong source of information.

While the book covers a very broad range of topics, many times the citations have not been updated and are often times dated. The content and information that is provided is correct and accurate, but this text can certainly benefit from having the latest research added. It does, however, include a great many topics that serve to inform students well.

The text is very easy to understand. It is written in a way that first and second year college students will find easy to understand. It also introduces students to current child and adolescent behavior that is important to be understood on an academic level. It does this in a comprehensive and clear manner.

This book is very consistent. The chapters are arranged by developmental stage. Even within each chapter there is a consistency of theorists. For example, each chapter begins with Piaget, then moves to Vygotsky, etc. This allows for great consistency among chapters. If I as the instructor decide to have students write about Piaget and his development theories throughout the life span, students will easily know that they can find this information in the first few pages of each chapter.

Certainly instructors will find the modularity of this book easy. Within each chapter the topics are self-contained and extensive. As I read the textbook, I envisioned myself perhaps not assigning entire chapters but assigning specific topics/modules and pages that students can read. I believe the modules can be used as a strong foundational reading to introduce students to concepts and then have students read supplemental information from primary sources or journals to reinforce what they have read in the chapter.

The organization of the book is clear and flows nicely. From the table of context students understand how the book is organized. The textbook would be even stronger if there was a more detailed table of context which highlights what topics are covered within each of the chapter. There is so much information contained within each chapter that it would be very beneficial to both students and instructor to quickly see what content and topics are covered in each chapter.

The interface is fine and works well.

The text is free from grammatical errors.

While the textbook does introduce some multicultural differences and similarities, it does not delve deeply into multiracial and multiethnic issues within America. It also offers very little comment on differences that occur among urban, rural, and suburban experiences. In addition, while it does talk about maturation and sexuality, LGBTQ issues could be more prominent.

Overall I enjoyed this text and will strongly consider using it in my course. The focus is clearly on human development and has very little emphasis on education. However, I intend to supplement this text with additional readings and videos that will show concrete examples of the concepts which are introduced in the text. It is a strong and worthy alternative to high-priced textbooks.

Reviewed by Mohsin Ahmed Shaikh, Assistant Professor, Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania on 9/5/19

The content extensively discusses various aspects of emotional, cognitive, physical and social development. Examples and case studies are really informative. Some of the areas that can be elaborated more are speech-language and hearing... read more

The content extensively discusses various aspects of emotional, cognitive, physical and social development. Examples and case studies are really informative. Some of the areas that can be elaborated more are speech-language and hearing development. Because these components contribute significantly in development of communication abilities and self-image.

Content covered is pretty accurate. I think the details impressive.

The content is relevant and is based on the established knowledge of the field.

Easy to read and follow.

The terminology used is consistent and appropriate.

I think of using various sections of this book in some of undergraduate and graduate classes.

The flow of the book is logical and easy to follow.

There are no interface issues. Images, charts and diagram are clear and easy to understand.

Well written

The text appropriate and do not use any culturally insensitive language.

I really like that this is a book with really good information which is available in open text book library.

Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction to Child Development

- Chapter 2: Conception, Heredity, & Prenatal Development

- Chapter 3: Birth and the Newborn

- Chapter 4: Physical Development in Infancy & Toddlerhood

- Chapter 5: Cognitive Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Chapter 6: Social and Emotional Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood

- Chapter 7: Physical Development in Early Childhood

- Chapter 8: Cognitive Development in Early Childhood

- Chapter 9: Social Emotional Development in Early Childhood

- Chapter 10: Middle Childhood - Physical Development

- Chapter 11: Middle Childhood – Cognitive Development

- Chapter 12: Middle Childhood - Social Emotional Development

- Chapter 13: Adolescence – Physical Development

- Chapter 14: Adolescence – Cognitive Development

- Chapter 15: Adolescence – Social Emotional Development

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn. We will look at how we change physically over time from conception through adolescence. We examine cognitive change, or how our ability to think and remember changes over the first 20 years or so of life. And we will look at how our emotions, psychological state, and social relationships change throughout childhood and adolescence.

About the Contributors

Contribute to this page.

Understanding Growth and Development Patterns of Infants

Authors as published.

Novella Ruffin, Family and Human Development Specialist, Virginia State University

Introduction

The first five years of life are a time of incredible growth and learning. An understanding of the rapid changes in a child’s developmental status prepares parents and caregivers to give active and purposeful attention to the preschool years and to guide and promote early learning that will serve as the foundation for later learning. Understanding child development is an important part of teaching young children.

Developmental change is a basic fact of human existence and each person is developmentally unique. Although there are universally accepted assumptions or principles of human development, no two children are alike. Children differ in physical, cognitive, social, and emotional growth patterns. They also differ in the ways they interact with and respond to their environment as well as play, affection, and other factors. Some children may appear to be happy and energetic all the time while other children may not seem as pleasant in personality. Some children are active while others are typically quiet. You may even find that some children are easier to manage and like than others. Having an understanding of the sequence of development prepares us to help and give attention to all of these children.

- Child Development

Development refers to change or growth that occurs in a child during the life span from birth to adolescence. This change occurs in an orderly sequence, involving physical, cognitive and emotional development . These three main areas of child development involve developmental changes which take place in a predictable pattern (age related), orderly, but with differences in the rate or timing of the changes from one person to another.

Physical Development

Physical development refers to physical changes in the body and involves changes in bone thickness, size, weight, gross motor, fine motor, vision, hearing, and perceptual development . Growth is rapid during the first two years of life. The child’s size, shape, senses, and organs undergo change. As each physical change occurs, the child gains new abilities. During the first year, physical development mainly involves the infant coordinating motor skills. The infant repeats motor actions which serve to build physical strength and motor coordination.

Infants at birth have reflexes as their sole physical ability. A reflex is an automatic body response to a stimulus that is involuntary; that is, the person has no control over this response. Blinking is a reflex which continues throughout life. There are other reflexes which occur in infancy and also disappear a few weeks or months after birth. The presence of reflexes at birth is an indication of normal brain and nerve development. When normal reflexes are not present or if the reflexes continue past the time they should disappear, brain or nerve damage is suspected.

Some reflexes, such as the rooting and sucking reflex, are needed for survival. The rooting reflex causes infants to turn their head toward anything that brushes their faces. This survival reflex helps them to find food such as a nipple. When an object is near a healthy infant’s lips, the infant will begin sucking immediately. This reflex also helps the child get food. This reflex usually disappears by three weeks of age.

The Moro reflex or “startle response” occurs when a newborn is startled by a noise or sudden movement. When startled, the infant reacts by flinging the arms and legs outward and extending the head. The infant then cries loudly, drawing the arms together. This reflex peaks during the first month and usually disappears after two months.

The Palmar grasp reflex is observed when the infant’s palm is touched and when a rattle or another object is placed across the palm. The infant’s hands will grip tightly. This reflex disappears the first three or four months after birth.

The Babinski reflex is present in normal babies of full term birth. When the sole of the infant’s foot is stroked on the outside from the heel to the toe, the infant’s toes fan out and curl and the foot twists in. This reflex usually lasts for the first year after birth.

The Stepping or walking reflex can also be observed in normal full term babies. When the infant is held so that the feet are flat on a surface, the infant will lift one foot after another in a stepping motion. This reflex usually disappears two months after birth and reappears toward the end of the first year as learned voluntary behavior.

Motor Sequence

Physical development is orderly and occurs in predictable sequence. For example, the motor sequence (order of new movements) for infants involves the following orderly sequence:

- Head and trunk control (infant lifts head, watches a moving object by moving the head from side to side- occurs in the first few months after birth.

- Infant rolls over turning from the stomach to the back first, then from back to stomach - four or five months of age.

- Sit upright in a high chair (requires development of strength in the back and neck muscles) - four to six months of age.

- Infant gradually is able to pull self into sitting positions.

- Crawling - occurs soon after the child learns to roll onto the stomach by pulling with the arms and wiggling the stomach. Some infants push with the legs.

- Hitching - infant must be able to sit without support; from the sitting position, they move their arms and legs, sliding the buttocks across the floor.

- Creeping - As the arms and legs gain more strength, the infant supports his weight on hands and knees.

- Stand with help - as arms and legs become stronger.

- Stand while holding on to furniture.

- Walk with help with better leg strength and coordination.

- Pull self up in a standing position.

- Stand alone without any support.

- Walk alone without any support or help.

Changes in physical skills such as those listed above in the motor sequence, including hopping, running, and writing, fall into two main areas of development. Gross motor (large muscle) development refers to improvement of skills and control of the large muscles of the legs, arms, back and shoulders which are used in walking, sitting, running, jumping, climbing, and riding a bike. Fine motor (small muscle) development refers to use of the small muscles of the fingers and hands for activities such as grasping objects, holding, cutting, drawing, buttoning, or writing.

Early hand movements in infants are reflex movements. By three to four months, infants are still unable to grasp objects because they close their hands reflexively too early or too late, having no control over these movements. They will swipe at objects. By the age of nine months, infants improve eye-hand coordination which gives them the ability to pick up objects.

Children must have manual or fine motor (hand) control to hold a pencil or crayon in order for them to write, draw, or color. Infants have the fine motor ability to scribble with a crayon by about 16 to 18 months of age when they have a holding grip (all fingers together like a cup). By the end of the second year, infants can make simple vertical and horizontal figures. By two years of age, the child shows a preference for one hand; however, hand dominance can occur much later at around four years of age. By the age of four, children have developed considerable mastery of a variety of grips, so that they can wrap their fingers around the pencil. Bimanual control is also involved in fine motor development, which enables a child to use both hands to perform a task, such as holding a paper and cutting with scissors, and catching a large ball.

At birth, an infant’s vision is blurry. The infant appears to focus in a center visual field during the first few weeks after birth. In infants, near vision is better developed than their far vision. They focus on objects held 8 to 15 inches in front of them. As their vision develops, infants show preference for certain objects and will gaze longer at patterned objects (disks) of checks and stripes than disks of one solid color. Studies also show that infants prefer bold colors to soft pastel colors. They also show visual preference for faces more than objects. By two months of age, an infant will show preference (gaze longer) at a smiling face than at a face without expression.

As infants grow older they are more interested in certain parts of the face. At one month of age, their gaze is on the hairline of a parent or other caregiver. By two months of age, infants show more interest in the eyes of a face. At three months of age, the infant seems very interested in the facial expression of adults. These changes in the infant’s interest in facial parts indicate that children give thought to certain areas of the face that interest them.

Hearing also develops early in life, and even before birth. Infants, from birth, will turn their heads toward a source or direction of sound and are startled by loud noises. The startle reaction is usually crying. Newborns also are soothed to sleep by rhythmic sounds such as a lullaby or heartbeat. Infants will look around to locate or explore sources of sounds, such as a doorbell. They also show reaction to a human voice while ignoring other competing sounds. A newborn can distinguish between the mother’s and father’s voices and the voice of a stranger by three weeks old. At three to six months, vocalizations begin to increase. Infants will increase their vocalizations when persons hold or play with them.

To explore their world, young children use their senses (touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing) in an attempt to learn about the world. They also think with their senses and movement. They form perceptions from their sensory activities. Sensory-Perceptual development is the information that is collected through the senses, the ideas that are formed about an object or relationship as a result of what the child learns through the senses. When experiences are repeated, they form a set of perceptions. This leads the child to form concepts (concept formation) . For example, a child will see a black dog with four legs and a tail and later see a black cat with four legs and a tail and call it a dog. The child will continue to identify the cat as a dog until the child is given additional information and feedback to help him learn the difference between a dog and a cat. Concepts help children to group their experiences and make sense out of the world. Giving young children a variety of experiences helps them form more concepts.

Cognitive Development

Cognitive development refers to the ways children reason (think), develop language, solve problems, and gain knowledge. Identifying colors, completing a maze, knowing the difference between one and many, and knowing how things are similar are all examples of cognitive tasks. Children learn through their senses and through their interactions with people and things in the world. They interact with the world through the senses (see, touch, hear, smell, taste), and construct meaning and understanding of the world. As children gain understanding and meaning of the world, their cognitive development can be observed in the ways they play, use language, interact with others, and construct objects and materials. As children grow and interact with their world, they go through various stages of development. Although the stages are not precisely tied to a particular age, there are characteristics that describe children at different ages.

Sensorimotor Stage

The sensorimotor stage occurs in infancy from birth to about 12 months. Here, infants learn about the world through their senses, looking around constantly, looking at faces of caregivers, responding to smiling faces. Their eyes focus on bright colors and they respond to sounds by looking toward the sound. During this time of sensory learning, infants also show interest in light and movement, such as a mobile above the crib. Infants also begin to recognize their own name in this stage.

Infants also learn through communication. Their initial communication is through crying which is a general cry to bring attention to their needs. Later the cry changes and becomes different and more specific to identify what the baby needs or wants. The cry develops into gestures, and the beginning stages of language such as babbling, then monosyllables such as “ba” and “da” and later to single words put together to make a meaningful sentence. You can observe that infants also communicate through their motor actions. As they grow, they kick and use their arms to reach for people and things that are interesting to them. They respond to voices and seek to be picked up by reaching out. Infants make a very important learning discovery - that through their actions of reaching, making sounds, or crying, they cause others to respond in certain ways. It is very important that parents and other caregivers nurture and respond to the infant’s actions, to hold, carry the infant, sing to the infant, play with the infant, and meet his needs in other responsive and nurturing ways.

As infants continue to interact with their surroundings and make meaning out of their world, they also learn about themselves, their own bodies. Their hands and toes become body objects of interest. They suck on their hands and toes and may seem to be fascinated with their own hands. During this stage of sensory learning, infants reach for, hit at, and grasp objects that are within their reach, such as dangling jewelry and long hair. They also enjoy toys that rattle and squeak and will put any and all things in the mouth. These are all sensory ways that the infant learns; however, we must make sure that the objects are clean and safe for the baby to explore.

As infants master new developments in the motor sequence (creeping and crawling), they learn that they have more control over their world. They are no longer totally dependent on an adult to meet some of their needs. For example, if an infant sees a toy on the floor, or his bottle on a table within reach, he has the motor capacity to move toward it and reach for it. The infant’s increased freedom to move and have toys and objects within reach is very important. The task for adults, parents and other caregivers is to ensure that babies have a safe and clean environment in which they can move about and interact.

Understanding the characteristics of cognitive development gives us knowledge and insights into how children are developing, thinking, and learning. Principles of cognitive development provide us with a basis for understanding how to encourage exploration, thinking, and learning. As parents and caregivers, we can support cognitive development in infants and young children by providing a variety of appropriate and stimulating materials and activities that encourage curiosity, exploration, and opportunities for problem solving.

Object Permanence

Between the age of six to nine months the concept of object permanence develops. This is the infant’s understanding that an object continues to exist even if it is out of the infant’s sight. Prior to this time, the infant’s understanding is “out of sight, out of mind.” Objects cease to exist when the infant does not see them. For example, when an infant plays with a rattle or other toy and a blanket is placed over the rattle, the infant does not search for it because it does not exist in the mind of the infant. When object permanence is developed, the child begins to understand that the rattle is still there even though it is covered, out of sight.

The infant’s understanding of object permanence means that infants are developing memory and goal oriented thinking. Searching under a blanket for a rattle means that the child remembers that the rattle was there. It also means that the infant has a goal of finding the rattle and takes action to find it. Infants during this time will give up searching within a few seconds if they do not find the object.

Also important to object permanence is the understanding that other people exist all the time. Children begin to understand that they can cry not just to get needs met but as a means of calling parents or other caregivers. They know that even if a person is not within their reach or their sight, the person still exists. The cry will call the person to them. Also, crying to call a person is a sign that infants are learning to communicate.

Emotional Development/ Social-Emotional Development

The expression of feelings about self, others, and things describe emotional development . Learning to relate to others is social development . Emotional and social development are often described and grouped together because they are closely interrelated growth patterns. Feelings of trust, fear, confidence, pride, friendship, and humor are all part of social-emotional development. Other emotional traits are self concept and self esteem. Learning to trust and show affection to others is a part of social-emotional development. The child’s relationship to a trusting and caring adult is a foundation of emotional development and personality development. Furthermore, when a child has been neglected, rejected, and does not feel secure, he has difficulty developing skills to socialize with others.

Temperament

Children, from birth, differ in the ways they react to their environment. Temperament refers to the quality and degree or intensity of emotional reactions. Passivity, irritability, and activity are three factors that affect a child’s temperament. Passivity refers to how actively involved a child is with his or her environment or surroundings. A passive infant withdraws from or is otherwise not engaged with a new person or event. An active infant does something in response to a new person or event. There is also difference in the level of irritability (tendency to feel distressed) of infants. Some infants may cry easily and be difficult to comfort and soothe even if you hold them. Other infants may rarely cry and are not bothered as much by change. Caring for these infants is usually viewed as easier for adults. Activity levels or levels of movement also vary in infants. Some infants make few movements, are quiet, and when asleep, may hardly move. Other infants constantly move their limbs (arms and legs) and may be restless in sleep.

As caregivers, we need to nurture and give loving attention to all infants regardless of their temperament. We also need to adjust to the temperament of different children. Even very irritable infants can grow to be emotionally happy and well adjusted if caregivers are patient, responsive, and loving in their caregiving ways.

At birth, infants do not show a wide range of emotions. They use movements, facial expressions, and sounds to communicate basic comfort or discomfort. They coo to show comfort and cry to show that they are uncomfortable. In the first few months, infants display a range of emotions as seen through their facial expressions. Happiness is shown when the corners of the mouth are pulled back and the cheeks are raised. The infant will begin to show fear, anger, and anxiety between six and nine months of age. Signs of fear are the open mouth with the corners of the mouth pulled back, wide eyes, and raised eyebrows. By the end of the second year, children have developed many ways to express their emotions.

Socially, young children and particularly infants tend to focus on the adults who are close to them and become bonded to a small group of people early in life- mainly the people who care for them. This forms the basis for attachment which is the strong emotional tie felt between the infant and significant other. The quality of attachments depends upon the adults. When attachments are formed, young infants learn that they can depend on mothers, fathers, caregivers, or older siblings to make them feel better.

Attachment begins early in life and infants show several early attachment behaviors. Behaviors such as cooing, kicking, gurgling, smiling and laughing show that infants care for and respond early to people who are important to them. Crying and clinging are also attachment behaviors of infants which are used to signal others. Infants as early as one month old show signs of attachment in the form of anxiety if they are cared for by an unfamiliar person. They may show distress signs such as irregular sleeping or eating patterns.

Separation Anxiety

Separation anxiety is another attachment behavior of infants. This is when a child shows distress by often crying when unhappy because a familiar caregiver (parent or other caregiver) is leaving. The first signs of separation anxiety appear at about six months of age and are more clearly seen by nine months of age. Separation anxiety is very strong by 15 months of age and begins to gradually weaken around this time also. Parents and other caregivers need to understand and prepare for this attachment behavior (separation anxiety) in children by making transitions easier for the child. Children between the age of 9 and 18 months will usually have a lot of difficulty beginning a child care program. Parents can make the transition easier by bringing the child’s favorite toy or blanket along. It is also important to understand separation anxiety as a normal developmental process in which children are fearful because their familiar caregivers are leaving them. Children beginning a child care program are in an unfamiliar surrounding with unfamiliar people. Children will gradually show less distress as the setting, the people, and routines become more familiar to them.

An understanding of infant growth and development patterns and concepts is necessary for parents and caregivers to create a nurturing and caring environment which will stimulate young children’s learning. The growth and development of infants are periods of rapid change in the child’s size, senses, and organs. Each change brings about new abilities. An infant’s development in motor coordination, forming concepts, learning and using language, having positive feelings about self and others prepares them to build upon new abilities that will be needed for each change in a new stage of development. Caregivers can provide activities and opportunities for infants that encourage exploration and curiosity to enhance children’s overall development.

Related Reading:

Bergen, Doris. 1988. “Stages of Play Development,” Play as a Medium for Learning and Development. Doris Bergen,ed., Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Bowlby, John.1969. Attachment. Attachment and Loss. Vol.I. New York:Basic Books.

Forman, George, and David Kuschner. 1983. The Child’s Construction of Knowledge. Washington, DC:NAEYC..

Greenspan, S. 1997. Growth of the Mind. New York: Addison Wesley.

Lerner, Clair. 2000. The Magic of Everyday Moments. Zero To Three, Washington, DC.

Shore, R. 1997. Rethinking the Brain: New Insights into Early Development. New York: Families and Work Institute.

Sprain, Joan. 1990. Developmentally Appropriate Care: What Does It Mean? National Network for Child Care- NNCC.

Virginia Cooperative Extension materials are available for public use, reprint, or citation without further permission, provided the use includes credit to the author and to Virginia Cooperative Extension, Virginia Tech, and Virginia State University.

Virginia Cooperative Extension is a partnership of Virginia Tech, Virginia State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and local governments. Its programs and employment are open to all, regardless of age, color, disability, sex (including pregnancy), gender, gender identity, gender expression, genetic information, ethnicity or national origin, political affiliation, race, religion, sexual orientation, or military status, or any other basis protected by law.

Publication Date

March 6, 2019

Available As

- Understanding Growth and Development Patterns of Infants (PDF)

Other resources in:

Other resources by:.

- Novella J. Ruffin

Other resources from:

- Virginia State University

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 Chapter 1: Introduction to Child Development

Chapter objectives.

After this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe the principles that underlie development.

- Differentiate periods of human development.

- Evaluate issues in development.

- Distinguish the different methods of research.

- Explain what a theory is.

- Compare and contrast different theories of child development.

Introduction

Welcome to Child Growth and Development. This text is a presentation of how and why children grow, develop, and learn.

We will look at how we change physically over time from conception through adolescence. We examine cognitive change, or how our ability to think and remember changes over the first 20 years or so of life. And we will look at how our emotions, psychological state, and social relationships change throughout childhood and adolescence. 1

Principles of Development

There are several underlying principles of development to keep in mind:

- Development is lifelong and change is apparent across the lifespan (although this text ends with adolescence). And early experiences affect later development.

- Development is multidirectional. We show gains in some areas of development, while showing loss in other areas.

- Development is multidimensional. We change across three general domains/dimensions; physical, cognitive, and social and emotional.

- The physical domain includes changes in height and weight, changes in gross and fine motor skills, sensory capabilities, the nervous system, as well as the propensity for disease and illness.

- The cognitive domain encompasses the changes in intelligence, wisdom, perception, problem-solving, memory, and language.

- The social and emotional domain (also referred to as psychosocial) focuses on changes in emotion, self-perception, and interpersonal relationships with families, peers, and friends.

All three domains influence each other. It is also important to note that a change in one domain may cascade and prompt changes in the other domains.

- Development is characterized by plasticity, which is our ability to change and that many of our characteristics are malleable. Early experiences are important, but children are remarkably resilient (able to overcome adversity).

- Development is multicontextual. 2 We are influenced by both nature (genetics) and nurture (the environment) – when and where we live and our actions, beliefs, and values are a response to circumstances surrounding us. The key here is to understand that behaviors, motivations, emotions, and choices are all part of a bigger picture. 3

Now let’s look at a framework for examining development.

Periods of Development

Think about what periods of development that you think a course on Child Development would address. How many stages are on your list? Perhaps you have three: infancy, childhood, and teenagers. Developmentalists (those that study development) break this part of the life span into these five stages as follows:

- Prenatal Development (conception through birth)

- Infancy and Toddlerhood (birth through two years)

- Early Childhood (3 to 5 years)

- Middle Childhood (6 to 11 years)

- Adolescence (12 years to adulthood)

This list reflects unique aspects of the various stages of childhood and adolescence that will be explored in this book. So while both an 8 month old and an 8 year old are considered children, they have very different motor abilities, social relationships, and cognitive skills. Their nutritional needs are different and their primary psychological concerns are also distinctive.

Prenatal Development

Conception occurs and development begins. All of the major structures of the body are forming and the health of the mother is of primary concern. Understanding nutrition, teratogens (or environmental factors that can lead to birth defects), and labor and delivery are primary concerns.

Figure 1.1 – A tiny embryo depicting some development of arms and legs, as well as facial features that are starting to show. 4

Infancy and Toddlerhood

The two years of life are ones of dramatic growth and change. A newborn, with a keen sense of hearing but very poor vision is transformed into a walking, talking toddler within a relatively short period of time. Caregivers are also transformed from someone who manages feeding and sleep schedules to a constantly moving guide and safety inspector for a mobile, energetic child.

Figure 1.2 – A swaddled newborn. 5

Early Childhood

Early childhood is also referred to as the preschool years and consists of the years which follow toddlerhood and precede formal schooling. As a three to five-year-old, the child is busy learning language, is gaining a sense of self and greater independence, and is beginning to learn the workings of the physical world. This knowledge does not come quickly, however, and preschoolers may initially have interesting conceptions of size, time, space and distance such as fearing that they may go down the drain if they sit at the front of the bathtub or by demonstrating how long something will take by holding out their two index fingers several inches apart. A toddler’s fierce determination to do something may give way to a four-year-old’s sense of guilt for action that brings the disapproval of others.

Figure 1.3 – Two young children playing in the Singapore Botanic Gardens 6

Middle Childhood

The ages of six through eleven comprise middle childhood and much of what children experience at this age is connected to their involvement in the early grades of school. Now the world becomes one of learning and testing new academic skills and by assessing one’s abilities and accomplishments by making comparisons between self and others. Schools compare students and make these comparisons public through team sports, test scores, and other forms of recognition. Growth rates slow down and children are able to refine their motor skills at this point in life. And children begin to learn about social relationships beyond the family through interaction with friends and fellow students.

Figure 1.4 – Two children running down the street in Carenage, Trinidad and Tobago 7

Adolescence

Adolescence is a period of dramatic physical change marked by an overall physical growth spurt and sexual maturation, known as puberty. It is also a time of cognitive change as the adolescent begins to think of new possibilities and to consider abstract concepts such as love, fear, and freedom. Ironically, adolescents have a sense of invincibility that puts them at greater risk of dying from accidents or contracting sexually transmitted infections that can have lifelong consequences. 8

Figure 1.5 – Two smiling teenage women. 9

There are some aspects of development that have been hotly debated. Let’s explore these.

Issues in Development

Nature and nurture.

Why are people the way they are? Are features such as height, weight, personality, being diabetic, etc. the result of heredity or environmental factors-or both? For decades, scholars have carried on the “nature/nurture” debate. For any particular feature, those on the side of Nature would argue that heredity plays the most important role in bringing about that feature. Those on the side of Nurture would argue that one’s environment is most significant in shaping the way we are. This debate continues in all aspects of human development, and most scholars agree that there is a constant interplay between the two forces. It is difficult to isolate the root of any single behavior as a result solely of nature or nurture.

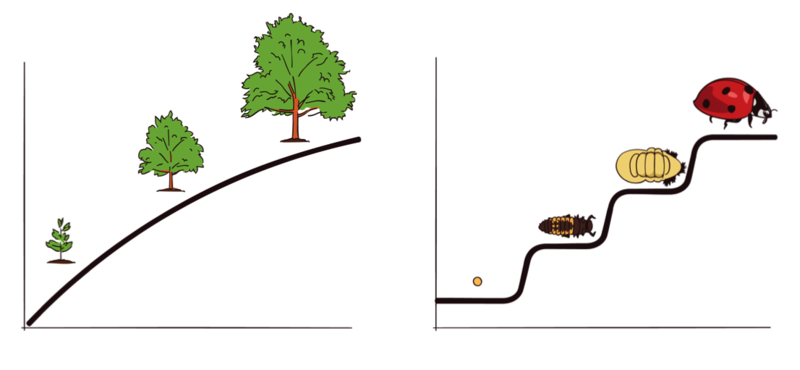

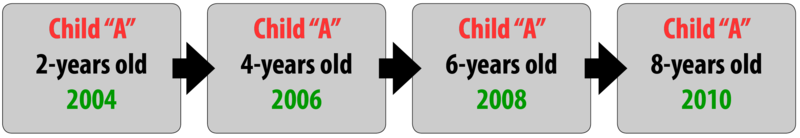

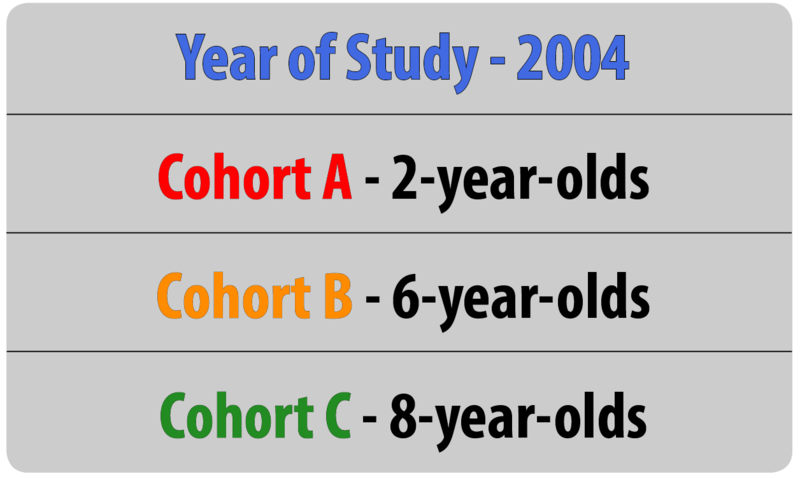

Continuity versus Discontinuity