Affiliate Login

- Policy Briefs

- Executive Committee

- Emeriti Faculty

- UC Network on Child Health, Poverty, and Public Policy

- Visting Graduate Scholars

- Media Mentions

- Center Updates

- Contact the Center

- for Research Affiliates

- for Graduate Students

- Visiting Faculty Scholars

- External Opportunities

- The Non-traditional Safety Net: Health & Education

- Labor Markets & Poverty

- Children & Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty

- Immigration & Poverty

- Other Activities

- Past Events

- Policy Briefs Short summaries of our research

- Poverty Facts

- Employment, Earnings and Inequality

- Increasing College Access and Success for Low Income Students

- American Poverty Research

- Profiles in Poverty Research

- Government Agencies

- Other Poverty Centers

Frequently Asked Questions

Faqs on poverty.

Ten Important Questions About Child Poverty and Family Economic Hardship

- Publication Type Report

- Post date December 1, 2009

Download PDF

What is the Nature of Poverty and Economic Hardship in the United States?

- What does it mean to experience poverty?

- How is poverty measured in the United States?

- Are Americans who experience poverty now better off than a generation ago?

- How accurate are commonly held stereotypes about poverty and economic hardship?

How Serious is the Problem of Economic Hardship for American Families?

- How many children in the U.S. live in families with low incomes?

- Are some children and families at greater risk for economic hardship than others?

- What are the effects of economic hardship on children?

Is it Possible to Reduce Economic Hardship among American Families?

- Why is there so much economic hardship in a country as wealthy as the U.S.?

- Why should Americans care about family economic hardship?

- What can be done to increase economic security for America’s children and families?

1. What does it mean to experience poverty?

Families and their children experience poverty when they are unable to achieve a minimum, decent standard of living that allows them to participate fully in mainstream society. One component of poverty is material hardship. Although we are all taught that the essentials are food, clothing, and shelter, the reality is that the definition of basic material necessities varies by time and place. In the United States, we all agree that having access to running water, electricity, indoor plumbing, and telephone service are essential to 21st century living even though that would not have been true 50 or 100 years ago.

To achieve a minimum but decent standard of living, families need more than material resources; they also need “human and social capital.” Human and social capital include education, basic life skills, and employment experience, as well as less tangible resources such as social networks and access to civic institutions. These non-material resources provide families with the means to get by, and ultimately, to get ahead. Human and social capital help families improve their earnings potential and accumulate assets, gain access to safe neighborhoods and high-quality services (such as medical care, schooling), and expand their networks and social connections.

The experiences of children and families who face economic hardship are far from uniform. Some families experience hard times for brief spells while a small minority experience chronic poverty. For some, the greatest challenge is inadequate financial resources, whether insufficient income to meet daily expenses or the necessary assets (savings, a home) to get ahead. For others, economic hardship is compounded by social isolation. These differences in the severity and depth of poverty matter, especially when it comes to the effects on children.

2. How is poverty measured in the United States?

The U.S. government measures poverty by a narrow income standard — this measure does not include material hardship (such as living in substandard housing) or debt, nor does it consider financial assets (such as savings or property). Developed more than 40 years ago, the official poverty measure is a specific dollar amount that varies by family size but is the same across the continental U.S..

According to the federal poverty guidelines, the poverty level is $22,050 for a family of four and $18,310 for a family of three (see table). (The poverty guidelines are used to determine eligibility for public programs. A similar but more complicated measure is used for calculating poverty rates.)

The current poverty measure was established in the 1960s and is now widely acknowledged to be outdated. It was based on research indicating that families spent about one-third of their incomes on food — the official poverty level was set by multiplying food costs by three. Since then, the same figures have been updated annually for inflation but have otherwise remained unchanged.

Yet food now comprises only one-seventh of an average family’s expenses, while the costs of housing, child care, health care, and transportation have grown disproportionately. Most analysts agree that today’s poverty thresholds are too low. And although there is no consensus about what constitutes a minimum but decent standard of living in the U.S., research consistently shows that, on average, families need an income of about twice the federal poverty level to meet their most basic needs.

Failure to update the federal poverty level for changes in the cost of living means that people who are considered poor today by the official standard are worse off relative to everyone else than people considered poor when the poverty measure was established. The current federal poverty measure equals about 31 percent of median household income, whereas in the 1960s, the poverty level was nearly 50 percent of the median.

The European Union and most advanced industrialized countries measure poverty quite differently from the U.S. Rather than setting minimum income thresholds below which individuals and families are considered to be poor, other countries measure economic disadvantage relative to the citizenry as a whole, for example, having income below 50 percent of median.

3. Are Americans who experience poverty now better off than a generation ago?

Material deprivation is not as widespread in the United States as it was 30 or 40 years ago. For example, few Americans experience severe or chronic hunger, due in large part to public food and nutrition programs, such as food stamps, school breakfast and lunch programs, and WIC (the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children). Over time, Social Security greatly reduced poverty and economic insecurity among the elderly. Increased wealth and technological advances have made it possible for ordinary families to have larger houses, computers, televisions, multiple cars, stereo equipment, air conditioning, and cell phones.

Some people question whether a family that has air conditioning or a DVD player should be considered poor. But in a wealthy nation such as the US, cars, computers, TVs, and other technologies are considered by most to be a normal part of mainstream American life rather than luxuries. Most workers need a car to get to work. TVs and other forms of entertainment link people to mainstream culture. And having a computer with access to the internet is crucial for children to keep up with their peers in school. Even air conditioning does more than provide comfort — in hot weather, it increases children’s concentration in school and improves the health of children, the elderly, and the chronically ill.

Consider as well the devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina. Prior to the hurricane, New Orleans had one of the highest child poverty rates in the country — 38 percent (and this figure would be much higher if it included families with incomes up to twice the official poverty level). One in five households in New Orleans lacked a car, and eight percent had no phone service. The pervasive social and economic isolation increased the loss of life from the hurricane and exacerbated the devastating effects on displaced families and children.

Focusing solely on the material possessions a family has ignores the other types of resources they need to provide a decent life for their children — a home in a safe neighborhood; access to good schools, good jobs and basic services; and less tangible resources such as basic life skills and support networks.

4. How accurate are commonly held stereotypes about poverty?

The most commonly held stereotypes about poverty are false. Family poverty in the U.S. is typically depicted as a static, entrenched condition, characterized by large numbers of children, chronic unemployment, drugs, violence, and family turmoil. But the realities of poverty and economic hardship are very different.

Americans often talk about “poor people” as if they are a distinct group with uniform characteristics and somehow unlike the rest of “us.” In fact, there is great diversity among children and families who experience economic hardship. Research shows that many stereotypes just aren’t accurate: a study of children born between 1970 and 1990 showed that 35 percent experienced poverty at some point during their childhood; only a small minority experienced persistent and chronic poverty. And more than 90 percent of low-income single mothers have only one, two, or three children.

Although most portrayals of poverty in the media and elsewhere reflect the experience of only a few, a significant portion of families in America have experienced economic hardship, even if it is not life-long. Americans need new ways of thinking about poverty that allow us to understand the full range of economic hardship and insecurity in our country. In addition to the millions of families who struggle to make ends meet, millions of others are merely one crisis — a job loss, health emergency, or divorce — away from financial devastation, particularly in this fragile economy. A recent study showed that the majority of American families with children have very little savings to rely on during times of crisis. Recently, more and more families have become vulnerable to economic hardship.

5. How many children in the US live in families with low incomes?

Given that official poverty statistics are deeply flawed, the National Center for Children in Poverty uses “low income” as one measure of economic hardship. Low income is defined as having income below twice the federal poverty level — the amount of income that research suggests is needed on average for families to meet their basic needs. About 41 percent of the nation’s children — nearly 30 million in 2008 — live in families with low incomes, that is, incomes below twice the official poverty level (for 2009, about $44,000 for a family of four).

Although families with incomes between 100 and 200 percent of the poverty level are not officially classified as poor, many face material hardships and financial pressures similar to families with incomes below the poverty level. Missed rent payments, utility shut offs, inadequate access to health care, unstable child care arrangements, and running out of food are not uncommon for such families.

Low-income rates for young children are higher than those for older children — 44 percent of children under age six live in low-income families, compared to 39 percent of children over age six. Parents of younger children tend to be younger and to have less education and work experience than parents of older children, so their earnings are typically lower.

6. Are some children and families at greater risk for economic hardship than others?

Low levels of parental education are a primary risk factor for being low income. Eighty-three percent of children whose parents have less than a high school diploma live in low-income families, and over half of children whose parents have only a high school degree are low income as well. Workers with only a high school degree have seen their wages stagnate or decline in recent decades while the income gap between those who have a college degree and those who do not has doubled. Yet only 27 percent of workers in the U.S. have a college degree.

Single-parent families are at greater risk of economic hardship than two-parent families, largely because the latter have twice the earnings potential. But research indicates that marriage does not guarantee protection from economic insecurity. More than one in four children with married parents lives in a low-income family. In rural and suburban areas, the majority of low-income children have married parents. And among Latinos, more than half of children with married parents are low income. Moreover, most individuals who experience poverty as adults grew up in married-parent households.

Although low-income rates for minority children are considerably higher than those for white children, this is due largely to a higher prevalence of other risk factors, for example, higher rates of single parenthood and lower levels of parental education and earnings. About 61 percent of black, 62 percent of Latino children and 57 percent of American Indian children live in low-income families, compared to about 27 percent of white children and 31 percent of Asian children. At the same time, however, whites comprise the largest group of low-income children: 11 million white children live in families with incomes below twice the federal poverty line.

Having immigrant parents also increases a child’s chances of living in a low-income family. More than 20 percent of this country’s children — about 16 million — have at least one foreign-born parent. Sixty percent of children whose parents are immigrants are low-income, compared to 37 percent of children whose parents were born in the U.S.

7. What are the effects of economic hardship on children?

Economic hardship and other types of deprivation can have profound effects on children’s development and their prospects for the future — and therefore on the nation as a whole. Low family income can impede children’s cognitive development and their ability to learn. It can contribute to behavioral, social, and emotional problems. And it can cause and exacerbate poor child health as well. The children at greatest risk are those who experience economic hardship when they are young and children who experience severe and chronic hardship.

It is not simply the amount of income that matters for children. The instability and unpredictability of low-wage work can lead to fluctuating family incomes. Children whose families are in volatile or deteriorating financial circumstances are more likely to experience negative effects than children whose families are in stable economic situations.

The negative effects on young children living in low income families are troubling in their own right. These effects are also cause for concern because they are associated with difficulties later in life — dropping out of school, poor adolescent and adult health, poor employment outcomes and experiencing poverty as adults. Stable, nurturing, and enriching environments in the early years help create a sturdy foundation for later school achievement, economic productivity, and responsible citizenship.

Parents need financial resources as well as human and social capital (basic life skills, education, social networks) to provide the experiences, resources, and services that are essential for children to thrive and to grow into healthy, productive adults — high-quality health care, adequate housing, stimulating early learning programs, good schools, money for books, and other enriching activities. Parents who face chronic economic hardship are much more likely than their more affluent peers to experience severe stress and depression — both of which are linked to poor social and emotional outcomes for children.

Is it Possible to Reduce Economic Hardship for American Families?

8. why is there so much economic hardship in a country as wealthy as the u.s..

Given its wealth, the U.S. had unusually high rates of child poverty and income inequality, even prior to the current economic downturn. These conditions are not inevitable — they are a function both of the economy and government policy. In the late 1990s, for example, there was a dramatic decline in low-income rates, especially among the least well off families. The economy was strong and federal policy supports for low-wage workers with children — the Earned Income Tax Credit, public health insurance for children, and child care subsidies — were greatly expanded. In the current economic downturn, it is expected that the number of poor children will increase by millions.

Other industrialized nations have lower poverty rates because they seek to prevent hardship by providing assistance to all families. These supports include “child allowances” (typically cash supplements), child care assistance, health coverage, paid family leave, and other supports that help offset the cost of raising children.

But the U.S. takes a different policy approach. Our nation does little to assist low-income working families unless they hit rock bottom. And then, such families are eligible only for means-tested benefits that tend to be highly stigmatized; most families who need help receive little or none. (One notable exception is the federal Earned Income Tax Credit.)

At the same time, middle- and especially upper-income families receive numerous government benefits that help them maintain and improve their standard of living — benefits that are largely unavailable to lower-income families. These include tax-subsidized benefits provided by employers (such as health insurance and retirement accounts), tax breaks for home owners (such as deductions for mortgage interest and tax exclusions for profits from home sales), and other tax preferences that privilege assets over income. Although most people don’t think of these tax breaks as government “benefits,” they cost the federal treasury nearly three times as much as benefits that go to low- to moderate-income families. In addition, middle- and upper-income families reap the majority of benefits from the child tax credit and the child care and dependent tax credit because neither is fully refundable.

In short, high rates of child poverty and income inequality in the U.S. can be reduced, but effective, widespread, and long-lasting change will require shifts in both national policy and the economy.

9. Why should Americans care about family economic hardship?

In addition to the harmful consequences for children, high rates of economic hardship exact a serious toll on the U.S. economy. Economists estimate that child poverty costs the U.S. $500 billion a year in lost productivity in the labor force and spending on health care and the criminal justice system. Each year, child poverty reduces productivity and economic output by about 1.3 percent of GDP.

The experience of severe or chronic economic hardship limits children’s potential and hinders our nation’s ability to compete in the global economy. American students, on average, rank behind students in other industrialized nations, particularly in their understanding of math and science. Analysts warn that America’s ability to compete globally will be severely hindered if many of our children are not as academically prepared as their peers in other nations.

Long-term economic trends are also troubling as they reflect the gradual but steady growth of economic insecurity among middle-income and working families over the last 30 years. Incomes have increased very modestly for all but the highest earners. Stagnant incomes combined with the high cost of basic necessities have made it difficult for families to save, and many middle- and low-income families alike have taken on crippling amounts of debt just to get by.

Research also indicates that economic inequality in America has been on the rise since the 1970s. Income inequality has reached historic levels — the income share of the top one percent of earners is at its highest level since 1929. Between 1979 and 2006, real after-tax incomes rose by 256 percent for the top one percent of households, compared to 21 percent and 11 percent for households in the middle and bottom fifth (respectively).

Economic mobility—the likelihood of moving from one income group to another—is on the decline in the U.S. Although Americans like to believe that opportunity is equally available to all, some groups find it harder to get ahead than others. Striving African American families have found upward mobility especially difficult to achieve and are far more vulnerable than whites to downward mobility. The wealth gap between blacks and whites — black families have been found to have one-tenth the net worth of white families — is largely responsible.

What all of these trends reveal is that the American Dream is increasingly out of reach for many families. The promise that hard work and determination will be rewarded has become an increasingly empty promise in 21st century America. It is in the best interest of our nation to see that the American Dream, an ideal so fundamental to our collective identity, be restored.

10. What can be done to increase economic security for America’s children and families?

A considerable amount of research has been devoted to this question. We know what families need to succeed economically, what parents need to care for and nurture their children, and what children need to develop into healthy, productive adults. The challenge is to translate this research knowledge into workable policy solutions that are appropriate for the US.

For families to succeed economically, we need an economy that works for all — one that provides workers with sufficient earnings to provide for a family. Specific policy strategies include strengthening the bargaining power of workers, expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, and increasing the minimum wage and indexing it to inflation. We also need to help workers get the training and education they need to succeed in a changing workforce. Dealing with low wages is necessary but not sufficient. Low- and middle-income families alike need relief from the high costs of health insurance and housing. Further programs that promote asset building among low-income families with children are also important.

As a nation, we also need to make it possible for adults to be both good workers and good parents, which requires greater workplace flexibility and paid time off. Workers need paid sick time, and parents need time off to tend to a sick child or talk to a child’s teacher. Currently, three in four low-wage workers have no paid sick days.

Despite the fact that a child’s earliest years have a profound effect on his or her life trajectory and ultimate ability to succeed, the U.S. remains one of the only industrialized countries that does not provide paid family leave for parents with a new baby. Likewise, child care is largely private in the U.S. — individual parents are left to find individual solutions to a problem faced by all working parents. Low- and middle-income families need more help paying for child care and more assistance in identifying reliable, nurturing care for their children, especially infants and toddlers.

These are only some of the policies needed to reduce economic hardship, strengthen families, and provide a brighter future for today’s — and tomorrow’s — children. With the right leadership, a strong national commitment, and good policy, it’s all possible.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

100 Questions: identifying research priorities for poverty prevention and reduction

Reducing poverty is important for those affected, for society and the economy. Poverty remains entrenched in the UK, despite considerable research efforts to understand its causes and possible solutions. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with the Centre for Science and Policy at the University of Cambridge, ran a democratic, transparent, consensual exercise involving 45 participants from government, non-governmental organisations, academia and research to identify 100 important research questions that, if answered, would help to reduce or prevent poverty. The list includes questions across a number of important themes, including attitudes, education, family, employment, heath, wellbeing, inclusion, markets, housing, taxes, inequality and power.

Related Papers

Policy & Politics

Justin Keen

Richard J White

This article explores the ways in which young people's decisions about post-compulsory education, training and employment are shaped by place, drawing on case study evidence from three deprived neighbourhoods in England. It discusses the way in which place-based social networks and attachment to place influence individuals' outlooks and how they interpret and act on the opportunities they see. While such networks and place attachment can be a source of strength in facilitating access to opportunities, they can also be a source of weakness in acting to constrain individuals to familiar choices and locations. In this way, 'subjective' geographies of opportunity may be much more limited than 'objective' geographies of opportunity. Hence it is important for policy to recognise the importance of 'bounded horizons'.

Anne Corden , Michael Hirst

Lisa Scullion

J. Poverty Soc. Justice

Toity Deave

Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

Kirsten Besemer

John McKendrick , Stephen Sinclair

Social Policy and Society

Line Nyhagen

John Hills , David Piachaud

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has supported this project as part of its programme of research and innovative development projects, which it hopes will be of value to policy makers, practitioners and service users. The facts presented and views expressed in this report are, however, ...

CASE Papers

Ruth Lister

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Jonathan Bradshaw

Ronald McQuaid

Colin Lindsay

Journal of Policy Analysis and Management

Liam Foster

Alison Garnham

Mark Tomlinson

Cambridge Journal of Economics

Kevin Albertson , Paul Stepney

Serena Romano

Mansel Aylward

Surya Monro

Alex Nunn , Ronald McQuaid , Tim Bickerstaffe

… by National Association of Welfare Rights …

Colin Talbot

GA Williams , Mark Tomlinson

Hilary Stevens

Chris Pittman

Ian Cummins

Information, communication & …

Abigail Davis

… , communication & society

Bryony Beresford

Martin Taulbut

research.dwp.gov.uk

Peter Allmark

Richard Riddell

Glen Bramley

Judy Corlyon

Vanesa Fuertes , Ronald McQuaid

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Shoshana Pollack

alan france

Emma Uprichard

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Poverty and Social Exclusion

Defining, measuring and tackling poverty, latest articles, home page featured articles, buenos aires 2017.

A recent report form the city of Buenos Aires measuring multi-dimensional poverty, using the consensual method, has found that in 2019, 15.3% of households were multi-dimensionally poor, rising to 25.7% for households with children under 18 years of age. The method established will be used to measure nu,ti-dimensional poverty on an ongoing basis.

6th Townsend poverty conference ad

We are now delighted to offer you the presentation slides and video recordings of sessions across the three days, featuring formal presentations, interactive Q&As, networking opportunities and much more.

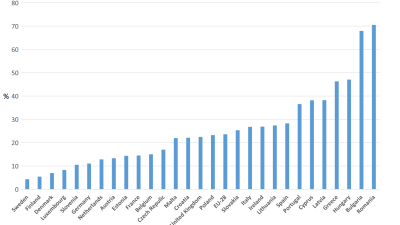

Child deprivation in EU member states, 2018

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Steering Group on Measuring Poverty and Inequality has been tasked with producing a guide on Measuring Social Exclusion which references a lot of our PSE work.

100 questions about poverty

Progress in reducing or preventing poverty in the UK could be helped by the answers to 100 important research questions, according to a new report. The questions have been identified by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and the Centre for Science and Policy at the University of Cambridge, based on an exercise involving 45 participants from government, non-governmental organisations, academia and research. They cover a range of themes, and indicate areas of particular research interest.

Key questions include:

- Attitudes towards poverty – To what extent does stigma contribute to the experience of living in poverty in the UK, and what can be done to address this?

- Education and family – To what extent do families (including extended families) provide the first line of defence against individual poverty, and what are the limits and geographical variations of this support?

- Employment – What explains variation in wages as a share of GDP internationally? What can countries do to combat low pay without causing unemployment in sectors that cannot move abroad?

- Health, well-being and inclusion – What is the nature and extent of poverty among those who do not, or cannot, access the safety net when they need it? What are the health risks associated with poor-quality work (low paid, insecure, poorly regulated etc) for individuals or households in poverty?

- Markets, service and the cost of living – What transport measures and interventions have the greatest negative/positive impact on poverty? What is the impact of up-front charging in public services on people in poverty?

- Place and housing – What is the effect of housing-related welfare changes on people and places in poverty?

- Tax, benefits and inequality – What would the impacts on poverty be of different models of more contributory benefit schemes? How can the effect on poverty of issues of diversity, such as ethnicity, disability, age, gender, sexual orientation or religion, be better understood and addressed? What relevance does inequality in the top half of the income distribution have for the reduction of poverty?

- Policy, power and agency – What forms of institutional structures, processes and reforms enable people living in poverty to hold state and non-state actors to account?

- The bigger picture – What are the most cost-effective interventions to prevent poverty over the life course? What differentiates the effects of poverty on men and women in terms of the impact on both their own quality of life and that of their families? Considering how much money has been spent on poverty alleviation, why has it not had more effect?

Source : William Sutherland et al., 100 Questions: Identifying Research Priorities for Poverty Prevention and Reduction , Joseph Rowntree Foundation Links : Report | JRF blog post

Tweet this page

- Help & FAQ

100 Questions: Identifying research priorities for poverty prevention and reduction

William J. Sutherland * , Chris Goulden, Kate Bell, Fran Bennett, Simon Burall, Marc Bush, Samantha Callan, Kim Catcheside, Julian Corner, Conor T. D'Arcy, Matt Dickson, James A. Dolan, Robert Doubleday, Bethany J. Eckley, Esther T. Foreman, Rowan Foster, Louisa Gilhooly, Ann Marie Gray, Amanda C. Hall, Mike Harmer Annette Hastings, Chris Johnes, Martin Johnstone, Peter Kelly, Peter Kenway, Neil Lee, Rhys Moore, Jackie Ouchikh, James Plunkett, Karen Rowlingson , Abigail Scott Paul, Tom A J Sefton, Faiza Shaheen, Sonia Sodha, Jonathan Stearn, Kitty Stewart, Emma Stone, Matthew Tinsley, Richard J. Tomsett, Paul Tyrer, Julia Unwin, David G. Wall, Patrick K A Wollner Show 23 more Show less

- Social Policy and Society

- Centre on Household Assets and Savings Management (CHASM)

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

Reducing poverty is important for those affected, for society and the economy. Poverty remains entrenched in the UK, despite considerable research efforts to understand its causes and possible solutions. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with the Centre for Science and Policy at the University of Cambridge, ran a democratic, transparent, consensual exercise involving 45 participants from government, non-governmental organisations, academia and research to identify 100 important research questions that, if answered, would help to reduce or prevent poverty. The list includes questions across a number of important themes, including attitudes, education, family, employment, heath, wellbeing, inclusion, markets, housing, taxes, inequality and power.

| Original language | English |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 189-205 |

| Number of pages | 17 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 21 |

| Issue number | 3 |

| DOIs | |

| Publication status | Published - Oct 2013 |

- Anti-poverty strategy

- Poverty policy

- Poverty research

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- Sociology and Political Science

- Public Administration

Access to Document

- 10.1332/175982713X671210

Fingerprint

- poverty Social Sciences 100%

- family education Social Sciences 62%

- housing market Social Sciences 55%

- taxes Social Sciences 49%

- non-governmental organization Social Sciences 47%

- inclusion Social Sciences 32%

- economy Social Sciences 29%

- cause Social Sciences 28%

T1 - 100 Questions

T2 - Identifying research priorities for poverty prevention and reduction

AU - Sutherland, William J.

AU - Goulden, Chris

AU - Bell, Kate

AU - Bennett, Fran

AU - Burall, Simon

AU - Bush, Marc

AU - Callan, Samantha

AU - Catcheside, Kim

AU - Corner, Julian

AU - D'Arcy, Conor T.

AU - Dickson, Matt

AU - Dolan, James A.

AU - Doubleday, Robert

AU - Eckley, Bethany J.

AU - Foreman, Esther T.

AU - Foster, Rowan

AU - Gilhooly, Louisa

AU - Gray, Ann Marie

AU - Hall, Amanda C.

AU - Harmer, Mike

AU - Hastings, Annette

AU - Johnes, Chris

AU - Johnstone, Martin

AU - Kelly, Peter

AU - Kenway, Peter

AU - Lee, Neil

AU - Moore, Rhys

AU - Ouchikh, Jackie

AU - Plunkett, James

AU - Rowlingson, Karen

AU - Paul, Abigail Scott

AU - Sefton, Tom A J

AU - Shaheen, Faiza

AU - Sodha, Sonia

AU - Stearn, Jonathan

AU - Stewart, Kitty

AU - Stone, Emma

AU - Tinsley, Matthew

AU - Tomsett, Richard J.

AU - Tyrer, Paul

AU - Unwin, Julia

AU - Wall, David G.

AU - Wollner, Patrick K A

PY - 2013/10

Y1 - 2013/10

N2 - Reducing poverty is important for those affected, for society and the economy. Poverty remains entrenched in the UK, despite considerable research efforts to understand its causes and possible solutions. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with the Centre for Science and Policy at the University of Cambridge, ran a democratic, transparent, consensual exercise involving 45 participants from government, non-governmental organisations, academia and research to identify 100 important research questions that, if answered, would help to reduce or prevent poverty. The list includes questions across a number of important themes, including attitudes, education, family, employment, heath, wellbeing, inclusion, markets, housing, taxes, inequality and power.

AB - Reducing poverty is important for those affected, for society and the economy. Poverty remains entrenched in the UK, despite considerable research efforts to understand its causes and possible solutions. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, with the Centre for Science and Policy at the University of Cambridge, ran a democratic, transparent, consensual exercise involving 45 participants from government, non-governmental organisations, academia and research to identify 100 important research questions that, if answered, would help to reduce or prevent poverty. The list includes questions across a number of important themes, including attitudes, education, family, employment, heath, wellbeing, inclusion, markets, housing, taxes, inequality and power.

KW - Anti-poverty strategy

KW - Poverty policy

KW - Poverty research

KW - UK poverty

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=84891603358&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1332/175982713X671210

DO - 10.1332/175982713X671210

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:84891603358

SN - 1759-8273

JO - Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

JF - Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Child Poverty in the United States: A Tale of Devastation and the Promise of Hope

Alyn t. mccarty.

University of Wisconsin-Madison, Center for Women’s Health and Health Disparities Research

The child poverty rate in the United States is higher than in most similarly developed countries, making child poverty one of America’s most pressing social problems. This article provides an introduction of child poverty in the US, beginning with a short description of how poverty is measured and how child poverty is patterned across social groups and geographic space. I then examine the consequences of child poverty with a focus educational outcomes and child health, and three pathways through which poverty exerts its influence: resources, culture, and stress. After a brief review of the anti-poverty policy and programmatic landscape, I argue that moving forward we must enrich the communities in which poor families live in addition to boosting incomes and directly supporting children’s skill development. I conclude with emerging research questions.

SECTION I: Introduction

In 2014, 15.5 million children—or 21.1% of children under age 18—lived in families with incomes below the federal poverty line, making children the largest group of poor people in the United States ( DeNavas-Walt & Proctor 2015 ). Rates are even higher for the youngest children: 25% of children under age 3 are poor ( Jiang et al. 2015 ). These figures position the US second only to Romania in rankings of child poverty rates among 35 industrialized countries ( Adamson 2012 ).

Poor children in the US face a widening economic chasm between themselves and their more affluent peers ( Autor 2014 ). Income inequality has grown substantially in the last forty years; after decades of decline, income inequality now harkens back to levels similar to those during the Great Depression ( Piketty & Saez 2014 ). What’s more, children from impoverished backgrounds in the US have a tougher time getting out of poverty than children in other similarly developed countries. Rates of social mobility are lower in the United States than most continental European countries ( Bjorklund & Jantti 2009 ; Duncan & Murnane 2011 , pg. 5–6; Hertz et al. 2008 ) and have remained unchanged since 1979 ( Lee & Solon 2009 ).

High rates of child poverty, income inequality, and social immobility motivate a sense of urgency and importance in research and policy focused on poor children and their families. In this article, I review the latest research on child poverty across multiple social and behavioral science disciplines. Together, this work tells two stories: One narrative warns of the long-term negative impacts associated with child poverty, but the other offers hope of resilience through policies and programs designed to reduce child poverty and mitigate its damages.

In Section II, I begin by describing how researchers define and measure poverty. Section III offers a descriptive portrait of what child poverty looks like in America today. In Section IV, I review literature on the impact of child poverty educational outcomes and child health. I discuss new types of data and approaches to the study of child poverty that have uncovered nuance in the impact of child poverty. In Section V, I describe three pathways through which poverty exerts its effects on children: resources, culture, and stress. Section VI briefly reviews anti-poverty policies that aim to reduce the rate of child poverty and early childhood interventions that aim to limit its effects. In Section VII, I argue that providing economic benefits to poor families and investing early on in children’s human capital may be more effective if paired with investments in the communities in which poor families live. Finally, in Section VII, I conclude with emerging research questions.

SECTION II: Definition of Poverty & Measurement

Approximately 46.7 million people in the United States live below the poverty line, a rate of 14.8 percent ( DeNavas-Walt & Proctor 2015 ). Of these, 15.5 million—about a third—are children. Children account for about 23 percent of the overall US population, which means that children are overrepresented among the poor ( US Census Bureau 2015 ). Figure 1 shows 2014 poverty rates for children across multiple age groups using data from the American Community Survey. 1 Overall, 21.7% of children are poor. Poverty rates are higher among younger children and lower among older children: approximately 24% of children ages 5 or younger are poor compared to about 18% of youth ages 16 or 17.

Source: Author’s calculations using American Community Survey (ACS) data, 2014.

Accurately measuring child poverty and how it varies over time and place gives us…

Accurately measuring child poverty and how it varies over time and place gives us insight into how rates of child poverty are shaped by economic, demographic, and public policy change ( Cancian & Danziger 2009 ). On its face, measuring poverty should be quite simple. Yet, there is some debate about how best to categorize a family’s poverty status ( Haveman et al. 2015 ). Since the early 1960s, poverty status has been determined by comparing a household’s pre-tax cash income (e.g., wages and salaries) to a threshold that accounts for inflation using the Consumer Price Index. The child poverty rate is the proportion of families with children who have incomes below the threshold. The threshold is anchored at three times the cost of a subsistence food budget. 2 The threshold is adjusted for family size, composition, and age of householder, but it is the same no matter where a person lives in the US.

The official poverty measure is intended to reflect the proportion of the population for whom the resources they share with others in their household are not enough to meet their basic needs ( Haveman et al. 2015 ). However, a number of criticisms of the measure have been raised, revealing the significant shortcomings of the way poverty is officially determined ( Citro & Michael 1995 ). In response to these criticisms, the Census Bureau now reports a supplemental poverty measure (SPM) each year, which (1) takes into account necessary expenses (e.g., taxes and childcare) and cash and in-kind government benefits (e.g., cash welfare, housing subsidies, WIC and SNAP benefits); (2) broadens the definition of household to include foster children and unmarried partners; (3) updates the poverty threshold annually rather than “anchoring” it to a set poverty line; and (4) reflects housing costs reported in the American Community Survey, thus varies by place of residence ( Haveman et al. 2015 ).

For most groups, the SPM rates are higher than official measures; however, for some groups—including children—the SPM rates are lower ( Short 2015 ). The lower SPM child poverty rate largely reflects the impact of government anti-poverty policies, many of which explicitly target families with children such as the Child Tax Credit, school lunch subsidies, and WIC benefits ( Fox et al. 2015 ). According to Short (2015) , the official poverty rate for children under 18 in 2014 was 21.5 percent, which exceeds the 2014 SPM rate of 16.7 percent by about 4.8 percentage points. 3

SECTION III: A PORTRAIT OF CHILD POVERTY IN AMERICA

The burden of child poverty is unequally distributed across population subgroups in the US. In this section, I describe patterns of child poverty in our society, drawing on research that explores the social and economic factors that generate and maintain poverty for some groups more than others, over time, and across geographic space.

The Color of Child Poverty

There are dramatic disparities in child poverty rates by race/ethnicity: in 2014, child poverty rates were highest for children who are non-Hispanic Black or African American (38%), American Indian (36%), or Hispanic or Latino (32%), while rates were lowest for children who are non-Hispanic White (13%) or Asian and Pacific Islander (13%) ( Kids Count 2015 ).

Though rates help us understand the disproportionate burden of child poverty for some racial/ethnic minorities, it is also revealing to examine the total population of children in poverty by race/ethnicity (see Figure 2 ). First, poverty affects all children, regardless of racial/ethnic background. Second, contrary to racialized stereotypes about who is poor in America, there are more non-Hispanic white children in poverty (4.9 million) than non-Hispanic Black or African American children (3.9 million). Third, the majority of children in poverty are of Hispanic origin (5.7 million). Fourth, for each racial/ethnic group, most children in poverty are between 0 and 5 years of age.

High levels of child poverty among Back, American Indian, and Hispanic children…

High levels of child poverty among Black, American Indian, and Hispanic children reflect changes over time in the economy, public policy, and institutional practices that disproportionately affect people of color, such as declining relative wages of less educated men, declining availability of full-time jobs, and rising incarceration rates ( Wilson 1996 ). The disproportionality of poverty by race/ethnicity also reflects past and current discrimination in schooling, housing markets, and labor markets ( Cancian & Danziger 2009 ; Desmond 2016 ; Stokes et al. 2001 ).

Immigration and Child Poverty in the US: A Growing Concern

Immigrant status is also closely associated with poverty. Children of recent immigrants are a rapidly growing share of the child population in the United States: from 2006 to 2011, the number of children with at least one immigrant parent grew by 1.5 million, from 15.7 to 17.2 million ( Hanson & Simms 2014 ). Thus, children of immigrants account for nearly a fourth of all children in the United States. The majority of children of immigrants are Hispanic, and more than 40% have parents from Mexico.

Similar to many racial/ethnic minority groups, immigrant children are disproportionately likely to experience poverty relative to children whose parents were born in the US. In 2009, 18.2% of children with native-born parents were poor compared to 27.2% of children with “established immigrant” parents (i.e., those who have been in the US for more than ten years), and 38.5% of children with parents who recently immigrated to the US (Wight et al. 2011).

Since immigrants represent an increasing share of the US population and poverty rates among the foreign born tend to be high, immigration directly affects the overall child poverty rate ( Raphael & Smolensky 2009 ). Theoretically, immigration could also affect child poverty rates by driving down the wages and employment of native-born workers, though there is little evidence to support this claim ( Raphael & Smolensky 2009 ).

Declining Rates of Marriage and the Growing Burden of Child Poverty

Child poverty rates are substantially higher for children in single-mother families than for those in married-couple families, in part because single-mother families have fewer potential earners, and many have difficulty collecting child support payments from fathers ( Mather 2010 ). In 2014, 30.6% of single mother families were poor, compared with only 6.2% of married families with children ( DeNavas-Walt & Proctor 2015 ).

During the 1970s and 1980s, there was a rapid increase in single-mother families in the US, and rates have remained high since the 1990s; nearly one-fourth of children under 18 live in single-mother families ( Mather 2010 ). 4 Cancian & Reed (2009) note that though women are now less likely to be married than previously, women also tend to have fewer children, are more educated, and are more likely to be working than in the past. The researchers argue that these trends have countervailing influences on the child poverty rate: increased maternal employment has offset the poverty increasing effects of single motherhood. Still, recent changes in family structure have increased the child poverty rate, all else being equal.

Poverty of Place: How Child Poverty is Spatially Distributed in the US

In addition to their race/ethnic identification, immigrant status, and their parents’ marital status, where children live can also put them at a greater risk of growing up poor. Though many conceive of poverty as an urban problem, 95 of the 100 counties in the US with the highest child poverty rates are located in rural areas, whereas most counties with the lowest child poverty rates tend to be in wealthy suburbs of large metropolitan areas ( O’Hare & Mather 2008 ). Poverty disproportionately affects children living in rural areas as a result of recent economic changes in rural communities where key industries have disappeared (e.g., family farms) or moved overseas (e.g., textiles manufacturing) ( O’Hare 2009 ; Vernon-Feagans et al. 2012 ). The service sector jobs that have replaced these industries contribute to higher rates of poverty because they are less stable and lower paying, and rural areas have not benefitted from the rise of technology-related companies in the same way as have urban and suburban areas ( O’Hare 2009 ).

Child poverty is also a highly clustered regional phenomenon. The South has a regional poverty rate of over 16%, and there are hotspot clusters of high rates of child poverty in the Mississippi Delta region, the Black Belt, Appalachia, southwest Texas and New Mexico, southern South Dakota, and northern Nebraska ( Voss et al. 2006 ). Regional variation in child poverty can in part be explained by their social and economic contexts. Structural factors such as racial/ethnic composition and industry combine to influence the social processes that generate levels of child poverty in different areas. For example, racial/ethnic composition is more strongly associated with child poverty in farming dependent areas, which in part explains the higher levels of child poverty that are observed in the South ( Curtis et al. 2012 ).

The supplemental child poverty rate varies widely across states, which in large part reflects variation in state anti-poverty policies ( The Anne E Casey Foundation 2015 ). In an analysis of the US Census Bureau Supplementary Poverty Measure Public Use Research files in 2012–2014, The Anne E Casey Foundation (2015) found that federal benefits, which generally do not adjust for differences in costs of living, have a smaller impact on reducing child poverty rates in states where cost of living is high. In addition, though most government benefits are funded at the federal level, states vary with respect to the ins-and-outs of policy implementation, particularly for welfare: income eligibility limits, benefit levels, financial incentives to work, time limits, eligibility requirements for two-parent families, and the stringency of rules that reduce or terminate benefits for families that are non-compliant ( McKernan & Ratcliffe 2006 ; Soss et al. 2001 ). Many of these welfare policy variations are associated with variation in poverty levels by state, making the state that children are raised in particularly consequential for their economic well-being ( McKernan & Ratcliffe 2006 ).

SECTION IV: Consequences of Poverty

The literature on the consequences of child poverty is enormous, and the latest scholarship is increasingly methodologically sophisticated (see recent review by Duncan et al., 2012 ). Recent research has moved away from cross-sectional analyses, which capture a snapshot of children’s lives at one point in time, toward longitudinal analyses, which allow the linking of trajectories of poverty exposures during infancy and early childhood to outcomes across the life course. As such, it is increasingly common for studies to address the dynamics of exposure to poverty, including intensity, timing, and duration (e.g., short term vs. long term poverty). Furthermore, studies are paying increasing attention to the context of children’s lives beyond their families’ own socioeconomic status by explicitly modeling the impact of economic resources of others around them, for example in their schools and neighborhoods.

These new ways of studying the effects of child poverty have revealed that: 1) most differences in outcomes between poor and non-poor children remain after adjusting for potentially confounding factors (i.e., factors other than income that are associated with both poverty and child outcomes); 2) poverty exposure may be especially harmful during early childhood, a period of rapid brain growth and development; 3) the longer a child is exposed to poverty, the greater the risk of negative outcomes; 4) the effects of poverty can accumulate over time or lie dormant for years, only to be revealed in adulthood; and 5) the socioeconomic context of neighborhoods and schools matter for children’s outcomes net of their own family’s resources ( Brooks-Gunn et al. 1993 ; Duncan & Magnuson 2011a ; Duncan et al. 1998 ; Duncan et al. 2010 ; Elder 1985 ; Entwisle et al. 2005 ; Foster & Furstenberg 1999 ; Harding 2003 ; Hertzman 1999 ; Kuh & Shlomo 2004 ; McLeod & Shanahan 1996 ; Ratcliffe & McKernan 2010 ; Sastry & Pebley 2010 ; Turley 2003 ).

In the next few pages, I review literature on two domains of child well-being: academic achievement and child health. Due to lack of space, I do not focus on other outcomes, though they remain the focus of much of the current academic research on the consequences of child poverty across the life course, including learning and developmental delays, criminal activity, teenage childbearing, marriage, and adult health and socioeconomic outcomes ( Brooks-Gunn & Duncan 1997b ; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn 1997 ; Duncan et al. 2010 ; Duncan et al. 2012 ).

A Growing Academic Achievement Gap Between Rich and Poor

One of the most widely studied outcomes of childhood poverty is success in school. The focus on schooling is rooted in the widespread belief that children who do well in school have a better chance of escaping poverty when they are adults. Indeed, education is increasingly necessary for economic wellbeing in the US, in part due to a growing earnings gap between those who are college-educated and those who are not ( Goldin & Katz 2008 ). Success in school also strongly predicts a wide variety of other desired outcomes, such as civic participation, adult health, and life expectancy ( Attewell & Levin 2007 ; Hout 2012 ; van Kippersluis et al. 2011 ). Yet, the challenge of succeeding academically for children living in poverty is a difficult one. Poverty has large and consistent associations with academic outcomes, including achievement on standardized tests, years of completed schooling, and degree attainment ( Bailey & Dynarski 2011 ; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan 1997a ; Duncan & Magnuson 2011b ; Entwisle et al. 2005 ). Differences between poor and non-poor children are observable early on and persist across the school years: gaps in academic achievement are evident in kindergarten, and by age 14, students from the bottom income quintile are a full academic year behind their peers in the top income quintile ( Duncan & Magnuson 2011b ; Duncan & Murnane 2011 ). What’s more, income inequality in academic achievement is getting worse rather than improving over time: the achievement gap between the 90th and 10th percentiles of the income distribution among children born in 2001 is 30–40 percent larger than among children born twenty-five years earlier and is now larger than racial gaps ( Reardon 2011 ). The growing income-achievement gap is driven by a strengthening of the association between family income and children’s academic achievement for families above the median income level, which reflects increasing parental investment in children’s cognitive development among the more economically advantaged ( Reardon 2011 ). 5

Impact of Poverty on the Physical and Mental Health of Children

Poverty is also key social determinant of infant and child health, which can have lasting effects on educational attainment, earnings, and adult health ( Aber et al. 1997 ; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn 1997b ; Wagmiller et al. 2006 ). The central role of poverty in shaping child health is increasingly clear. Recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics released a policy statement and technical report that recognizes this centrality, drawing on research demonstrating a causal relation between early childhood poverty and child health ( Council on Community Pediatrics 2016 ).

For infants, poverty increases the risk of a number of birth outcomes including low birth weight, which is a general indictor of a baby’s in utero environment and development and a precursor to subsequent physical health and cognitive and emotion problems ( Bennett 1997 ; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan 1997b ; Starfield et al. 1991 ). Poverty increases the risk of infant mortality, another widely accepted indicator of the health and well-being of children ( Brooks-Gunn & Duncan 1997b ; Corman & Grossman 1985 ). With an infant mortality rate of 6.1 in 2009, the US lags far behind European countries, ranking last in a comparison of 26 OECD countries ( MacDorman et al. 2014 ). The excess infant mortality rate in the US is largely driven by post-neonatal deaths (those that occur between one month and a year after the birth) among low-income mothers ( Chen et al. forthcoming ).

For children, poverty is associated with a number of physical health insults: increased risk of injuries resulting from accidents or physical abuse/neglect; more frequent and severe chronic conditions (e.g., asthma, diabetes, and problems with hearing, vision, and speech); more frequent acute illnesses; poorer nutrition and growth; lower immunization rates or delayed immunization; and increased risk of obesity and its complications ( Aber et al. 1997 ; Starfield 1991 ; Currie & Lin 2007 ; Case et al. 2002 ).

In addition to physical health problems, the disadvantages associated with poverty and economic insecurity can trigger significant mental health problems for children, including ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and mood and anxiety disorders (Costello et al. 2004; Cuellar 2015 ; Perou et al. 2013 ). Mental health problems are more common than physical health problems, and their effects can be more pervasive ( Currie & Stabile 2006 ; Currie 2009 ). Approximately one fourth of youth experience a mental disorder during the past year and about a third across their lifetimes ( Merikangas et al. 2009 ). These problems, which are the dominant cause of childhood disability, can restrict children’s social competence and opportunities to learn ( Delaney & Smith 2012 ; Halfon et al. 2012 ).

Estimates across poverty status for mental disorders combined are not available. But, according to a recent summary of mental health surveillance among children in the US between 2005–2011 by the Center for Disease Control, prevalence rates are higher for children living in poverty compared with non-poor children for ADHD, behavior or conduct disorders, and mood/anxiety disorders ( Perou et al. 2013 ). The only exception to the pattern is among children who have been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders, who are more likely to come from more economically advantaged families.

Beyond The Individual: How Neighborhood Poverty Affects Children

A rising share of US children live in high-poverty neighborhoods, defined as a neighborhood with poverty rates of 30 percent or more: more than 10 percent of US children lived in a high poverty neighborhood in 2010, up from 8.7 percent in 2000, a 25% increase ( Mather & Dupuis 2012 ). There are small but clear negative effects for children of growing up in a poor neighborhood that are beyond the effects of growing up in a poor family (see Sastry 2012 for a summary of this literature). Children growing up in high-poverty neighborhoods are at a higher risk of health problems, teen pregnancy, and dropping out of school ( Shonkoff & Phillips 2000 ; Brooks-Gunn et al. 1993 ). What’s more, the effects of neighborhoods may linger across generations. Many caregivers themselves grew up in the neighborhoods in which they are raising their children ( Sharkey 2008 ), and neighborhood environments experienced over multiple generations of a family influence children’s cognitive ability: exposure to neighborhood poverty over two consecutive generations can reduce a child’s cognitive ability by more than half a standard deviation ( Sharkey & Elwert 2011 ).

Section V: MechanismS of Influence

There are several pathways through which poverty affects children’s outcomes, which have been linked to three main theoretical frameworks: resources, culture, and family and environmental stress ( Duncan et al. 2014 ). This section reviews these frameworks, emphasizing the particular mechanisms that link poverty to child outcomes that each bring to light.

Material and Social Resources

Parents who struggle to make ends meet do not have enough income to fulfill basic material needs for their children, such as food, clothing, adequate and stable housing, and quality educational environments ( Becker 1991 ). Families who are poor also tend to be less socially connected to others, are less emotionally supported, and have more frequent negative social interactions ( Lin 2000 ; Mickelson & Kubzansky 2003 ). Inequality in access to resourceful social networks contributes to—and even reproduces—social inequality (for a review and discussion, see Lin 2000 ; DiMaggio & Garip 2012 ). In some ways, material and social resources work in tandem to disadvantage families in poverty. For example, high rates of mobility in areas of concentrated economic disadvantage erode the social fabric of neighborhoods, a process which has negative consequences for families who are able to stay put ( Jacobs 1961 ). As Desmond (2016) emphasizes in his ethnography Evicted , housing instability and evictions operate as mechanisms that degrade the social connectivity upon which resourceful neighborhoods are built. Evictions are not rare—one in eight families face involuntary moves each year nationwide—and evictions disproportionately affect low-income families with children. Many poor families that are in need of stable social environments to raise their children struggle to maintain stable housing, and are forced to move from place to place when a combination of their good will and financial supports give way to a rental market that profits from tenants’ financial instability ( Desmond 2016 ). Facing eviction, these families are not motivated to invest in their neighborhoods, emotionally or otherwise, and the ties that are formed between those crippled by the weight of their housing situations are often “disposable,” made for the short-term benefits they provide but easily discarded ( Desmond 2012 ). Disposable ties can add stress rather than reduce it, making them ill-suited to rebuff the negative consequences of poverty on child outcomes.

A Renewed Focus on the Culture of Poverty

After a considerable absence from the research agenda of social scientists, the study of culture within poverty scholarship has been reinvigorated. A culture perspective asks questions about how and why people cope with poverty and how they escape it, focusing on individuals’ beliefs, preferences, orientations, and strategies in response to poverty as well as anti-poverty policies and programs ( Small et al. 2010 ). Unlike much of what proceeded it, current culture of poverty scholarship avoids blaming the victim for their problems, rather focusing on why poor people adopt certain frames, values, and repertoires, and how people make meaning of their social status in relation to others ( Small et al. 2010 ).

Central to literature that addresses child poverty from a cultural perspective are studies of how parenting practices operate as a mechanism through which poverty affects children. For example, Lareau (2003) observes families from different class backgrounds with school-aged children in order to understand how social class differences in child-rearing strategies might contribute to stratification processes. She argues that social class position shapes parents’ cultural logics of child-rearing. Middle and upper class families practice “concerted cultivation,” wherein parents actively foster and assess their child’s talents, opinions, and skills. In contrast, working class and poor families are more likely to see the development of their children as an “accomplishment of natural growth,” allowing for unstructured free time socializing with family and community members and teaching children to be deferential and quiet. As a result of these different approaches, Lareau argues that middle-class children exhibit a sense of entitlement that puts them at a distinct advantage within schools and other institutions, while working-class children develop a sense of constraint in relation to schooling and the wider social world and are less adept at responding to school demands and practices. While Lareau’s theory is intuitively appealing, the small scope of her study leaves many questions unanswered. Nonetheless, her study is a primary example of the culture of poverty approach, which highlights parenting practices as key to understanding the mechanism through which poverty impacts children.

The Stress of Poverty

In contrast to the material, social, or cultural pathways that highlight social, cultural and economic factors and how they affect children, the stress pathway turns our focus inside the body. Living in poverty is a stressful, often chaotic experience ( Thompson 2014 ; Vernon-Feagans et al. 2012 ; Evans and Wachs 2010 ). The term “toxic stress” is often used to describe the potential impact on body systems of living in the disorganized, unstable, and unpredictable environments of impoverished families ( Garner & Shonkoff 2012 ). Toxic stress refers to strong, frequent, or prolonged activation of the body’s stress response system ( Thompson 2014 ). In contrast to positive or tolerable stress responses, which refer to more mild and adaptive changes in the body’s stress response system or stronger changes over a short period of time, a toxic stress response can undermine the organization of the brain. In some cases, toxic stress can challenge the body’s ability to respond to subsequent stressors, even those of the positive or tolerable variety ( Ladd et al. 2000 ). This lowered threshold makes some poor children less capable of coping effectively with stress as they age, influences genomic function and brain development, and increases the risk of stress-related physical and mental health problems later in life ( Blair et al. 2011 ; Danese & McEwen 2012 ).

SECTION VI: Anti-Poverty Policy and Interventions

It is clear that the consequences of growing up poor are substantial, particularly when children are exposed to conditions associated with poverty early on and for long stretches of time ( Duncan & Magnuson 2011a ). Government policies and early childhood interventions represent society’s response to the burden of child poverty. A comprehensive review of anti-poverty policies is beyond the scope of this review (see Cancian & Danziger 2009 and Haveman et al. 2015 for excellent analyses of anti-poverty efforts over the past 60 years), but the consensus is that anti-poverty policies successfully lift many people out of poverty, especially people with children ( Danziger and Wimer 2014 ; Haveman et al. 2015 ). In particular, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which is an income-based monthly benefit that can be used to purchase food at authorized stores, has become one of the most effective anti-poverty policies, particularly for households with children living in deep poverty ( Bartfeld et al. 2015 ). Yet, economic benefits of current policies constitute proportionately less of their income for poor families now than in prior decades ( Danziger & Danziger 2009 ). The public benefits that remain available to low-income families are mostly concentrated among families with earnings, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC), mostly come in the form of in-kind benefits—like SNAP—rather than cash assistance ( Shaefer et al 2015 ), and often fall very short of full coverage for those in need. For example, Section 8 housing choice vouchers, which guarantee that a family will pay no more than 30 percent of its income for housing, are available only to a third of poor renting families ( Desmond 2016 ).

In addition to anti-poverty policies that supplement income or increase employment for families with children, there are also programs and interventions that help redress the negative effects of poverty on children’s life chances. Rigorous evaluations of a number of famous early childhood programs (e.g., the Perry Preschool program, The Incredible Years, and the Abecedarian project) are often cited as evidence that such programs can at least partially compensate for the disadvantages associated with growing up poor, promoting cognitive skills and non-cognitive traits such as motivation (Cuhna et al. 2006). The positive effects appear to be long-lasting, and early interventions produce larger effects than programs focused on older children. Ultimately, though expensive at the outset, the returns on early investments come in the form of a more productive workforce, a reduction in expensive treatment for mental and physical problems, reduced reliance on public assistance, and less involvement in the criminal justice system ( Heckman et al. 2010 ).

In contrast to small-scale early childhood interventions, Head Start, which is administered by the Administration for Children and Families within the Department of Health and Human Services, serves over 1 million low-income children ages birth to 5 ( Administration for Children and Families 2014 ). Head Start services generally focus on early learning, health and developmental screenings, and strengthening parent-child relationships. Though children who attend Head Start score below norms across developmental areas including language, literacy, and mathematics, at both Head Start entry and exit ( Aikens et al. 2013 ), Head Start is associated with modest improvements in children’s preschool experiences and school readiness in certain areas compared to similarly disadvantaged children who did not attend Head Start ( Puma et al. 2012 ). However, the benefits appear to wane over time.

Another large scale program designed to address the needs of low-income families with children is the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV) ( Michalopoulos et al. 2015 ). MEICHV began as a pilot initiative in the Bush administration and a full fledged program in 2010 as an expansion to the Affordable Care Act. Between 2010 and 2014, it provided $1.5 billion to states for home visiting. For the most part, states used the MIECHV funds to expand the use of four evidence-based home visiting models: Early Head Start – Home Based Program Option; Healthy Families America; Nurse-Family Partnership; and Parents as Teachers. Home visiting programs vary quite a bit, but generally consist of visits from social workers, parent educators, and/or registered nurses to low-income pregnant women and new parents. Participants receive health check-ups and referrals, parenting advice, and guidance with navigating other programs. The duration and frequency of the visits vary depending on the program and age of the child. Some continue until the baby is two years old, others support families until children complete kindergarten. A recent review of 19 home visiting models suggests that home visiting programs have favorable impacts on a number of child outcomes including child health, child development, and school readiness ( Avellar et al. 2015 ). Many of the programs have sustained impacts at least one year after program enrollment.

SECTION VII: A Community approach to combating child poverty

Anti-poverty policy and early childhood interventions are successful, but both typically focus on individual families and children. This focus draws away from the ecological underpinnings of the poverty experience. Multiple ecologies of children’s lives—the variety of institutions with which families interact, the relations among these institutions, and the social networks of families—contribute developmental and educational inequalities among children (e.g., Bronfenbrenner & Morris 1997 ; Coleman 1988 ; Durlauf & Young 2001 ; Gamoran 1992 ; Turley 2003 ; Vandell & Pierce 2002 ). Given evidence of the increasing spatial concentration of poverty and the impact of living in areas of concentrated economic deprivation ( Jargowsky 2013 ; Sastry 2012 ), I argue that child and/or family-centered approaches may be more effective and longer lasting if paired with approaches that directly and purposefully target the communities in which low-income families live, thus in the ecological contexts of poor children.

A community approach should involve both indirect investments through institutions such as stable and affordable housing, schools, and labor markets, and direct investments through programs explicitly designed to strengthen social connectivity among parents. Indeed, a crucial aspect of breaking the cycle of poverty must directly build resourceful social connections among the caregivers of poor children. Resourceful social connections are those that are rich in social resources, like social support (e.g., listening to problems or plans for the future), social control (e.g., maintaining consistent expectations among parents and others within the social network), advice and information (e.g., regarding program eligibility, effectiveness of teachers and other institutional agents), and commonplace reciprocal exchanges (e.g., car pooling, child care) ( Domina 2005 ; Thoits 2011 ; Small 2009 ). As many low-income families know all too well, it takes a lot of effort, energy, and human capital to take advantage of the benefits the state provides ( Edin & Lein 1997 ). Building resourceful social connections within high-poverty neighborhoods can make these tasks less daunting by spreading information about how to determine eligibility, sharing in child care responsibilities, and providing transportation to government agencies, doctors’ offices, school, and other institutions designed to help poor families. Additionally, perhaps by investing in the social resources of communities devastated by high rates of poverty, we can empower residents to fight for policy changes they identify for themselves as immediately warranted.

Sociological research is not unequivocal about the benefits of tight social networks. Similar to the depiction of “disposable ties” describe above, Portes and Landolt (1996) argue that we are remiss when failing to consider the pitfalls of close relationships in areas of concentrated disadvantage. Thus, merely connecting parents to each other may not be enough to benefit children. The quality of those connections is tantamount as well. One example of a community-based program that targets parental social resources for low-income families is Families and Schools Together (FAST). FAST is a multi-family group intervention developed using family stress theory, family systems theory, social ecological theory, and community development strategies ( McDonald and Frey 1999 ). Four randomized controlled trials of the program show that, compared to control groups, FAST participants exhibit reduced aggressive and withdrawal behaviors, increased academic competence, and more developed social skills ( Abt Associates 2001 ; Kratochwill et al. 2004 ; McDonald et al. 2006 ; Gamoran et al. 2012 ). The effect of FAST on child outcomes is mediated in part through its effect on parent social networks ( Turley et al. 2012 ). Parents who participate in FAST are more likely to know other parents in their child’s school, to report that other parents share their expectations for their children, and to participate in reciprocal exchanges with other parents ( Turley et al. 2012 ).

The FAST program and others like it take direct aim at the quantity and quality of parents’ social connections. Social resource interventions may break down insidious hurdles that may be difficult for children from low-income families to overcome than by intervening through income supplementation or skill acquisition alone. Of course, the success of these types of programs will be undercut by the high rates of residential mobility currently experienced in low-income neighborhoods. Thus, indirect investments in social resources, for example through expanding housing vouchers to enable more poor families to pay their rent and avoid eviction ( Desmond 2016 ), should be considered a requisite for a truly enriched community approach to combating child poverty.

SECTION VIII: Emerging research questions