- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Types of Literature Review — A Guide for Researchers

Table of Contents

Researchers often face challenges when choosing the appropriate type of literature review for their study. Regardless of the type of research design and the topic of a research problem , they encounter numerous queries, including:

What is the right type of literature review my study demands?

- How do we gather the data?

- How to conduct one?

- How reliable are the review findings?

- How do we employ them in our research? And the list goes on.

If you’re also dealing with such a hefty questionnaire, this article is of help. Read through this piece of guide to get an exhaustive understanding of the different types of literature reviews and their step-by-step methodologies along with a dash of pros and cons discussed.

Heading from scratch!

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review provides a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge on a particular topic, which is quintessential to any research project. Researchers employ various literature reviews based on their research goals and methodologies. The review process involves assembling, critically evaluating, and synthesizing existing scientific publications relevant to the research question at hand. It serves multiple purposes, including identifying gaps in existing literature, providing theoretical background, and supporting the rationale for a research study.

What is the importance of a Literature review in research?

Literature review in research serves several key purposes, including:

- Background of the study: Provides proper context for the research. It helps researchers understand the historical development, theoretical perspectives, and key debates related to their research topic.

- Identification of research gaps: By reviewing existing literature, researchers can identify gaps or inconsistencies in knowledge, paving the way for new research questions and hypotheses relevant to their study.

- Theoretical framework development: Facilitates the development of theoretical frameworks by cultivating diverse perspectives and empirical findings. It helps researchers refine their conceptualizations and theoretical models.

- Methodological guidance: Offers methodological guidance by highlighting the documented research methods and techniques used in previous studies. It assists researchers in selecting appropriate research designs, data collection methods, and analytical tools.

- Quality assurance and upholding academic integrity: Conducting a thorough literature review demonstrates the rigor and scholarly integrity of the research. It ensures that researchers are aware of relevant studies and can accurately attribute ideas and findings to their original sources.

Types of Literature Review

Literature review plays a crucial role in guiding the research process , from providing the background of the study to research dissemination and contributing to the synthesis of the latest theoretical literature review findings in academia.

However, not all types of literature reviews are the same; they vary in terms of methodology, approach, and purpose. Let's have a look at the various types of literature reviews to gain a deeper understanding of their applications.

1. Narrative Literature Review

A narrative literature review, also known as a traditional literature review, involves analyzing and summarizing existing literature without adhering to a structured methodology. It typically provides a descriptive overview of key concepts, theories, and relevant findings of the research topic.

Unlike other types of literature reviews, narrative reviews reinforce a more traditional approach, emphasizing the interpretation and discussion of the research findings rather than strict adherence to methodological review criteria. It helps researchers explore diverse perspectives and insights based on the research topic and acts as preliminary work for further investigation.

Steps to Conduct a Narrative Literature Review

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-writing-a-narrative-review_fig1_354466408

Define the research question or topic:

The first step in conducting a narrative literature review is to clearly define the research question or topic of interest. Defining the scope and purpose of the review includes — What specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore? What are the main objectives of the research? Refine your research question based on the specific area you want to explore.

Conduct a thorough literature search

Once the research question is defined, you can conduct a comprehensive literature search. Explore and use relevant databases and search engines like SciSpace Discover to identify credible and pertinent, scholarly articles and publications.

Select relevant studies

Before choosing the right set of studies, it’s vital to determine inclusion (studies that should possess the required factors) and exclusion criteria for the literature and then carefully select papers. For example — Which studies or sources will be included based on relevance, quality, and publication date?

*Important (applies to all the reviews): Inclusion criteria are the factors a study must include (For example: Include only peer-reviewed articles published between 2022-2023, etc.). Exclusion criteria are the factors that wouldn’t be required for your search strategy (Example: exclude irrelevant papers, preprints, written in non-English, etc.)

Critically analyze the literature

Once the relevant studies are shortlisted, evaluate the methodology, findings, and limitations of each source and jot down key themes, patterns, and contradictions. You can use efficient AI tools to conduct a thorough literature review and analyze all the required information.

Synthesize and integrate the findings

Now, you can weave together the reviewed studies, underscoring significant findings such that new frameworks, contrasting viewpoints, and identifying knowledge gaps.

Discussion and conclusion

This is an important step before crafting a narrative review — summarize the main findings of the review and discuss their implications in the relevant field. For example — What are the practical implications for practitioners? What are the directions for future research for them?

Write a cohesive narrative review

Organize the review into coherent sections and structure your review logically, guiding the reader through the research landscape and offering valuable insights. Use clear and concise language to convey key points effectively.

Structure of Narrative Literature Review

A well-structured, narrative analysis or literature review typically includes the following components:

- Introduction: Provides an overview of the topic, objectives of the study, and rationale for the review.

- Background: Highlights relevant background information and establish the context for the review.

- Main Body: Indexes the literature into thematic sections or categories, discussing key findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks.

- Discussion: Analyze and synthesize the findings of the reviewed studies, stressing similarities, differences, and any gaps in the literature.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main findings of the review, identifies implications for future research, and offers concluding remarks.

Pros and Cons of Narrative Literature Review

- Flexibility in methodology and doesn’t necessarily rely on structured methodologies

- Follows traditional approach and provides valuable and contextualized insights

- Suitable for exploring complex or interdisciplinary topics. For example — Climate change and human health, Cybersecurity and privacy in the digital age, and more

- Subjectivity in data selection and interpretation

- Potential for bias in the review process

- Lack of rigor compared to systematic reviews

Example of Well-Executed Narrative Literature Reviews

Paper title: Examining Moral Injury in Clinical Practice: A Narrative Literature Review

Source: SciSpace

You can also chat with the papers using SciSpace ChatPDF to get a thorough understanding of the research papers.

While narrative reviews offer flexibility, academic integrity remains paramount. So, ensure proper citation of all sources and maintain a transparent and factual approach throughout your critical narrative review, itself.

2. Systematic Review

A systematic literature review is one of the comprehensive types of literature review that follows a structured approach to assembling, analyzing, and synthesizing existing research relevant to a particular topic or question. It involves clearly defined criteria for exploring and choosing studies, as well as rigorous methods for evaluating the quality of relevant studies.

It plays a prominent role in evidence-based practice and decision-making across various domains, including healthcare, social sciences, education, health sciences, and more. By systematically investigating available literature, researchers can identify gaps in knowledge, evaluate the strength of evidence, and report future research directions.

Steps to Conduct Systematic Reviews

Source:- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Steps-of-Systematic-Literature-Review_fig1_321422320

Here are the key steps involved in conducting a systematic literature review

Formulate a clear and focused research question

Clearly define the research question or objective of the review. It helps to centralize the literature search strategy and determine inclusion criteria for relevant studies.

Develop a thorough literature search strategy

Design a comprehensive search strategy to identify relevant studies. It involves scrutinizing scientific databases and all relevant articles in journals. Plus, seek suggestions from domain experts and review reference lists of relevant review articles.

Screening and selecting studies

Employ predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to systematically screen the identified studies. This screening process also typically involves multiple reviewers independently assessing the eligibility of each study.

Data extraction

Extract key information from selected studies using standardized forms or protocols. It includes study characteristics, methods, results, and conclusions.

Critical appraisal

Evaluate the methodological quality and potential biases of included studies. Various tools (BMC medical research methodology) and criteria can be implemented for critical evaluation depending on the study design and research quetions .

Data synthesis

Analyze and synthesize review findings from individual studies to draw encompassing conclusions or identify overarching patterns and explore heterogeneity among studies.

Interpretation and conclusion

Interpret the findings about the research question, considering the strengths and limitations of the research evidence. Draw conclusions and implications for further research.

The final step — Report writing

Craft a detailed report of the systematic literature review adhering to the established guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). This ensures transparency and reproducibility of the review process.

By following these steps, a systematic literature review aims to provide a comprehensive and unbiased summary of existing evidence, help make informed decisions, and advance knowledge in the respective domain or field.

Structure of a systematic literature review

A well-structured systematic literature review typically consists of the following sections:

- Introduction: Provides background information on the research topic, outlines the review objectives, and enunciates the scope of the study.

- Methodology: Describes the literature search strategy, selection criteria, data extraction process, and other methods used for data synthesis, extraction, or other data analysis..

- Results: Presents the review findings, including a summary of the incorporated studies and their key findings.

- Discussion: Interprets the findings in light of the review objectives, discusses their implications, and identifies limitations or promising areas for future research.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main review findings and provides suggestions based on the evidence presented in depth meta analysis.

*Important (applies to all the reviews): Remember, the specific structure of your literature review may vary depending on your topic, research question, and intended audience. However, adhering to a clear and logical hierarchy ensures your review effectively analyses and synthesizes knowledge and contributes valuable insights for readers.

Pros and Cons of Systematic Literature Review

- Adopts rigorous and transparent methodology

- Minimizes bias and enhances the reliability of the study

- Provides evidence-based insights

- Time and resource-intensive

- High dependency on the quality of available literature (literature research strategy should be accurate)

- Potential for publication bias

Example of Well-Executed Systematic Literature Review

Paper title: Systematic Reviews: Understanding the Best Evidence For Clinical Decision-making in Health Care: Pros and Cons.

Read this detailed article on how to use AI tools to conduct a systematic review for your research!

3. Scoping Literature Review

A scoping literature review is a methodological review type of literature review that adopts an iterative approach to systematically map the existing literature on a particular topic or research area. It involves identifying, selecting, and synthesizing relevant papers to provide an overview of the size and scope of available evidence. Scoping reviews are broader in scope and include a diverse range of study designs and methodologies especially focused on health services research.

The main purpose of a scoping literature review is to examine the extent, range, and nature of existing studies on a topic, thereby identifying gaps in research, inconsistencies, and areas for further investigation. Additionally, scoping reviews can help researchers identify suitable methodologies and formulate clinical recommendations. They also act as the frameworks for future systematic reviews or primary research studies.

Scoping reviews are primarily focused on —

- Emerging or evolving topics — where the research landscape is still growing or budding. Example — Whole Systems Approaches to Diet and Healthy Weight: A Scoping Review of Reviews .

- Broad and complex topics : With a vast amount of existing literature.

- Scenarios where a systematic review is not feasible: Due to limited resources or time constraints.

Steps to Conduct a Scoping Literature Review

While Scoping reviews are not as rigorous as systematic reviews, however, they still follow a structured approach. Here are the steps:

Identify the research question: Define the broad topic you want to explore.

Identify Relevant Studies: Conduct a comprehensive search of relevant literature using appropriate databases, keywords, and search strategies.

Select studies to be included in the review: Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, determine the appropriate studies to be included in the review.

Data extraction and charting : Extract relevant information from selected studies, such as year, author, main results, study characteristics, key findings, and methodological approaches. However, it varies depending on the research question.

Collate, summarize, and report the results: Analyze and summarize the extracted data to identify key themes and trends. Then, present the findings of the scoping review in a clear and structured manner, following established guidelines and frameworks .

Structure of a Scoping Literature Review

A scoping literature review typically follows a structured format similar to a systematic review. It includes the following sections:

- Introduction: Introduce the research topic and objectives of the review, providing the historical context, and rationale for the study.

- Methods : Describe the methods used to conduct the review, including search strategies, study selection criteria, and data extraction procedures.

- Results: Present the findings of the review, including key themes, concepts, and patterns identified in the literature review.

- Discussion: Examine the implications of the findings, including strengths, limitations, and areas for further examination.

- Conclusion: Recapitulate the main findings of the review and their implications for future research, policy, or practice.

Pros and Cons of Scoping Literature Review

- Provides a comprehensive overview of existing literature

- Helps to identify gaps and areas for further research

- Suitable for exploring broad or complex research questions

- Doesn’t provide the depth of analysis offered by systematic reviews

- Subject to researcher bias in study selection and data extraction

- Requires careful consideration of literature search strategies and inclusion criteria to ensure comprehensiveness and validity.

In short, a scoping review helps map the literature on developing or emerging topics and identifying gaps. It might be considered as a step before conducting another type of review, such as a systematic review. Basically, acts as a precursor for other literature reviews.

Example of a Well-Executed Scoping Literature Review

Paper title: Health Chatbots in Africa Literature: A Scoping Review

Check out the key differences between Systematic and Scoping reviews — Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

4. Integrative Literature Review

Integrative Literature Review (ILR) is a type of literature review that proposes a distinctive way to analyze and synthesize existing literature on a specific topic, providing a thorough understanding of research and identifying potential gaps for future research.

Unlike a systematic review, which emphasizes quantitative studies and follows strict inclusion criteria, an ILR embraces a more pliable approach. It works beyond simply summarizing findings — it critically analyzes, integrates, and interprets research from various methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, mixed methods) to provide a deeper understanding of the research landscape. ILRs provide a holistic and systematic overview of existing research, integrating findings from various methodologies. ILRs are ideal for exploring intricate research issues, examining manifold perspectives, and developing new research questions.

Steps to Conduct an Integrative Literature Review

- Identify the research question: Clearly define the research question or topic of interest as formulating a clear and focused research question is critical to leading the entire review process.

- Literature search strategy: Employ systematic search techniques to locate relevant literature across various databases and sources.

- Evaluate the quality of the included studies : Critically assess the methodology, rigor, and validity of each study by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to filter and select studies aligned with the research objectives.

- Data Extraction: Extract relevant data from selected studies using a structured approach.

- Synthesize the findings : Thoroughly analyze the selected literature, identify key themes, and synthesize findings to derive noteworthy insights.

- Critical appraisal: Critically evaluate the quality and validity of qualitative research and included studies by using BMC medical research methodology.

- Interpret and present your findings: Discuss the purpose and implications of your analysis, spotlighting key insights and limitations. Organize and present the findings coherently and systematically.

Structure of an Integrative Literature Review

- Introduction : Provide an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the integrative review.

- Methods: Describe the opted literature search strategy, selection criteria, and data extraction process.

- Results: Present the synthesized findings, including key themes, patterns, and contradictions.

- Discussion: Interpret the findings about the research question, emphasizing implications for theory, practice, and prospective research.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main findings, limitations, and contributions of the integrative review.

Pros and Cons of Integrative Literature Review

- Informs evidence-based practice and policy to the relevant stakeholders of the research.

- Contributes to theory development and methodological advancement, especially in the healthcare arena.

- Integrates diverse perspectives and findings

- Time-consuming process due to the extensive literature search and synthesis

- Requires advanced analytical and critical thinking skills

- Potential for bias in study selection and interpretation

- The quality of included studies may vary, affecting the validity of the review

Example of Integrative Literature Reviews

Paper Title: An Integrative Literature Review: The Dual Impact of Technological Tools on Health and Technostress Among Older Workers

5. Rapid Literature Review

A Rapid Literature Review (RLR) is the fastest type of literature review which makes use of a streamlined approach for synthesizing literature summaries, offering a quicker and more focused alternative to traditional systematic reviews. Despite employing identical research methods, it often simplifies or omits specific steps to expedite the process. It allows researchers to gain valuable insights into current research trends and identify key findings within a shorter timeframe, often ranging from a few days to a few weeks — unlike traditional literature reviews, which may take months or even years to complete.

When to Consider a Rapid Literature Review?

- When time impediments demand a swift summary of existing research

- For emerging topics where the latest literature requires quick evaluation

- To report pilot studies or preliminary research before embarking on a comprehensive systematic review

Steps to Conduct a Rapid Literature Review

- Define the research question or topic of interest. A well-defined question guides the search process and helps researchers focus on relevant studies.

- Determine key databases and sources of relevant literature to ensure comprehensive coverage.

- Develop literature search strategies using appropriate keywords and filters to fetch a pool of potential scientific articles.

- Screen search results based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Extract and summarize relevant information from the above-preferred studies.

- Synthesize findings to identify key themes, patterns, or gaps in the literature.

- Prepare a concise report or a summary of the RLR findings.

Structure of a Rapid Literature Review

An effective structure of an RLR typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction: Briefly introduce the research topic and objectives of the RLR.

- Methodology: Describe the search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction process.

- Results: Present a summary of the findings, including key themes or patterns identified.

- Discussion: Interpret the findings, discuss implications, and highlight any limitations or areas for further research

- Conclusion: Summarize the key findings and their implications for practice or future research

Pros and Cons of Rapid Literature Review

- RLRs can be completed quickly, authorizing timely decision-making

- RLRs are a cost-effective approach since they require fewer resources compared to traditional literature reviews

- Offers great accessibility as RLRs provide prompt access to synthesized evidence for stakeholders

- RLRs are flexible as they can be easily adapted for various research contexts and objectives

- RLR reports are limited and restricted, not as in-depth as systematic reviews, and do not provide comprehensive coverage of the literature compared to traditional reviews.

- Susceptible to bias because of the expedited nature of RLRs. It would increase the chance of overlooking relevant studies or biases in the selection process.

- Due to time constraints, RLR findings might not be robust enough as compared to systematic reviews.

Example of a Well-Executed Rapid Literature Review

Paper Title: What Is the Impact of ChatGPT on Education? A Rapid Review of the Literature

A Summary of Literature Review Types

Literature Review Type | Narrative | Systematic | Integrative | Rapid | Scoping |

Approach | The traditional approach lacks a structured methodology | Systematic search, including structured methodology | Combines diverse methodologies for a comprehensive understanding | Quick review within time constraints | Preliminary study of existing literature |

How Exhaustive is the process? | May or may not be comprehensive | Exhaustive and comprehensive search | A comprehensive search for integration | Time-limited search | Determined by time or scope constraints |

Data Synthesis | Narrative | Narrative with tabular accompaniment | Integration of various sources or methodologies | Narrative and tabular | Narrative and tabular |

Purpose | Provides description of meta analysis and conceptualization of the review | Comprehensive evidence synthesis | Holistic understanding | Quick policy or practice guidelines review | Preliminary literature review |

Key characteristics | Storytelling, chronological presentation | Rigorous, traditional and systematic techniques approach | Diverse source or method integration | Time-constrained, systematic approach | Identifies literature size and scope |

Example Use Case | Historical exploration | Effectiveness evaluation | Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed combination | Policy summary | Research literature overview |

Tools and Resources for Conducting Different Types of Literature Reviews

Online scientific databases.

Platforms such as SciSpace , PubMed , Scopus , Elsevier , and Web of Science provide access to a vast array of scholarly literature, facilitating the search and data retrieval process.

Reference management software

Tools like SciSpace Citation Generator , EndNote, Zotero , and Mendeley assist researchers in organizing, annotating, and citing relevant literature, streamlining the review process altogether.

Automate Literature Review with AI tools

Automate the literature review process by using tools like SciSpace literature review which helps you compare and contrast multiple papers all on one screen in an easy-to-read matrix format. You can effortlessly analyze and interpret the review findings tailored to your study. It also supports the review in 75+ languages, making it more manageable even for non-English speakers.

Goes without saying — literature review plays a pivotal role in academic research to identify the current trends and provide insights to pave the way for future research endeavors. Different types of literature review has their own strengths and limitations, making them suitable for different research designs and contexts. Whether conducting a narrative review, systematic review, scoping review, integrative review, or rapid literature review, researchers must cautiously consider the objectives, resources, and the nature of the research topic.

If you’re currently working on a literature review and still adopting a manual and traditional approach, switch to the automated AI literature review workspace and transform your traditional literature review into a rapid one by extracting all the latest and relevant data for your research!

There you go!

Frequently Asked Questions

Narrative reviews give a general overview of a topic based on the author's knowledge. They may lack clear criteria and can be biased. On the other hand, systematic reviews aim to answer specific research questions by following strict methods. They're thorough but time-consuming.

A systematic review collects and analyzes existing research to provide an overview of a topic, while a meta-analysis statistically combines data from multiple studies to draw conclusions about the overall effect of an intervention or relationship between variables.

A systematic review thoroughly analyzes existing research on a specific topic using strict methods. In contrast, a scoping review offers a broader overview of the literature without evaluating individual studies in depth.

A systematic review thoroughly examines existing research using a rigorous process, while a rapid review provides a quicker summary of evidence, often by simplifying some of the systematic review steps to meet shorter timelines.

A systematic review carefully examines many studies on a single topic using specific guidelines. Conversely, an integrative review blends various types of research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

You might also like

This ChatGPT Alternative Will Change How You Read PDFs Forever!

Smallpdf vs SciSpace: Which ChatPDF is Right for You?

Adobe PDF Reader vs. SciSpace ChatPDF — Best Chat PDF Tools

Literature Review: Types of literature reviews

- Traditional or narrative literature reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic literature reviews

- Annotated bibliography

- Keeping up to date with literature

- Finding a thesis

- Evaluating sources and critical appraisal of literature

- Managing and analysing your literature

- Further reading and resources

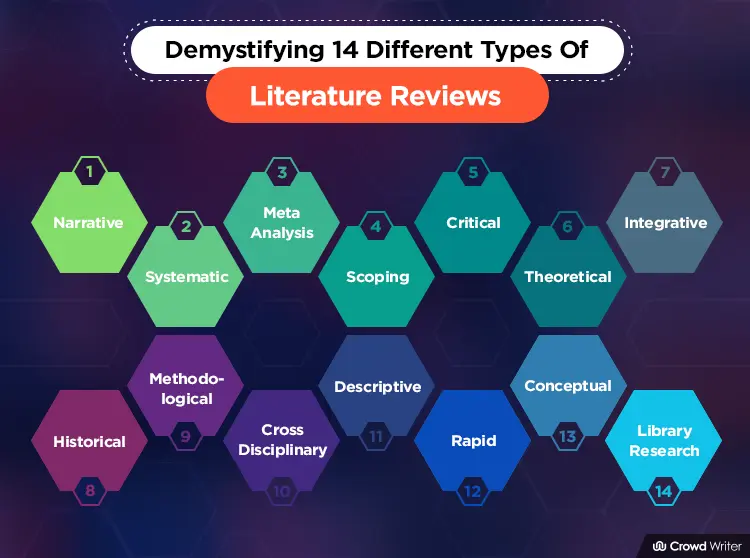

Types of literature reviews

The type of literature review you write will depend on your discipline and whether you are a researcher writing your PhD, publishing a study in a journal or completing an assessment task in your undergraduate study.

A literature review for a subject in an undergraduate degree will not be as comprehensive as the literature review required for a PhD thesis.

An undergraduate literature review may be in the form of an annotated bibliography or a narrative review of a small selection of literature, for example ten relevant articles. If you are asked to write a literature review, and you are an undergraduate student, be guided by your subject coordinator or lecturer.

The common types of literature reviews will be explained in the pages of this section.

- Narrative or traditional literature reviews

- Critically Appraised Topic (CAT)

- Scoping reviews

- Annotated bibliographies

These are not the only types of reviews of literature that can be conducted. Often the term "review" and "literature" can be confusing and used in the wrong context. Grant and Booth (2009) attempt to clear up this confusion by discussing 14 review types and the associated methodology, and advantages and disadvantages associated with each review.

Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26 , 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

What's the difference between reviews?

Researchers, academics, and librarians all use various terms to describe different types of literature reviews, and there is often inconsistency in the ways the types are discussed. Here are a couple of simple explanations.

- The image below describes common review types in terms of speed, detail, risk of bias, and comprehensiveness:

"Schematic of the main differences between the types of literature review" by Brennan, M. L., Arlt, S. P., Belshaw, Z., Buckley, L., Corah, L., Doit, H., Fajt, V. R., Grindlay, D., Moberly, H. K., Morrow, L. D., Stavisky, J., & White, C. (2020). Critically Appraised Topics (CATs) in veterinary medicine: Applying evidence in clinical practice. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7 , 314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00314 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

- The table below lists four of the most common types of review , as adapted from a widely used typology of fourteen types of reviews (Grant & Booth, 2009).

| Identifies and reviews published literature on a topic, which may be broad. Typically employs a narrative approach to reporting the review findings. Can include a wide range of related subjects. | 1 - 4 weeks | 1 | |

| Assesses what is known about an issue by using a systematic review method to search and appraise research and determine best practice. | 2 - 6 months | 2 | |

| Assesses the potential scope of the research literature on a particular topic. Helps determine gaps in the research. (See the page in this guide on .) | 1 - 4 weeks | 1 - 2 | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise, and synthesise research evidence so as to aid decision-making and determine best practice. Can vary in approach, and is often specific to the type of study, which include studies of effectiveness, qualitative research, economic evaluation, prevalence, aetiology, or diagnostic test accuracy. | 8 months to 2 years | 2 or more |

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26 (2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

See also the Library's Literature Review guide.

Critical Appraised Topic (CAT)

For information on conducting a Critically Appraised Topic or CAT

Callander, J., Anstey, A. V., Ingram, J. R., Limpens, J., Flohr, C., & Spuls, P. I. (2017). How to write a Critically Appraised Topic: evidence to underpin routine clinical practice. British Journal of Dermatology (1951), 177(4), 1007-1013. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15873

Books on Literature Reviews

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Traditional or narrative literature reviews >>

- Last Updated: Aug 11, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/review

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Types of Literature Review

There are many types of literature review. The choice of a specific type depends on your research approach and design. The following types of literature review are the most popular in business studies:

Narrative literature review , also referred to as traditional literature review, critiques literature and summarizes the body of a literature. Narrative review also draws conclusions about the topic and identifies gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge. You need to have a sufficiently focused research question to conduct a narrative literature review

Systematic literature review requires more rigorous and well-defined approach compared to most other types of literature review. Systematic literature review is comprehensive and details the timeframe within which the literature was selected. Systematic literature review can be divided into two categories: meta-analysis and meta-synthesis.

When you conduct meta-analysis you take findings from several studies on the same subject and analyze these using standardized statistical procedures. In meta-analysis patterns and relationships are detected and conclusions are drawn. Meta-analysis is associated with deductive research approach.

Meta-synthesis, on the other hand, is based on non-statistical techniques. This technique integrates, evaluates and interprets findings of multiple qualitative research studies. Meta-synthesis literature review is conducted usually when following inductive research approach.

Scoping literature review , as implied by its name is used to identify the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a given topic. It has been noted that “scoping reviews are useful for examining emerging evidence when it is still unclear what other, more specific questions can be posed and valuably addressed by a more precise systematic review.” [1] The main difference between systematic and scoping types of literature review is that, systematic literature review is conducted to find answer to more specific research questions, whereas scoping literature review is conducted to explore more general research question.

Argumentative literature review , as the name implies, examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. It should be noted that a potential for bias is a major shortcoming associated with argumentative literature review.

Integrative literature review reviews , critiques, and synthesizes secondary data about research topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. If your research does not involve primary data collection and data analysis, then using integrative literature review will be your only option.

Theoretical literature review focuses on a pool of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. Theoretical literature reviews play an instrumental role in establishing what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

At the earlier parts of the literature review chapter, you need to specify the type of your literature review your chose and justify your choice. Your choice of a specific type of literature review should be based upon your research area, research problem and research methods. Also, you can briefly discuss other most popular types of literature review mentioned above, to illustrate your awareness of them.

[1] Munn, A. et. al. (2018) “Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach” BMC Medical Research Methodology

John Dudovskiy

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Literature Reviews

- Types of reviews

- Getting started

Types of reviews and examples

Choosing a review type.

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

- Meta-analysis

- Systematized

Definition:

"A term used to describe a conventional overview of the literature, particularly when contrasted with a systematic review (Booth et al., 2012, p. 265).

Characteristics:

- Provides examination of recent or current literature on a wide range of subjects

- Varying levels of completeness / comprehensiveness, non-standardized methodology

- May or may not include comprehensive searching, quality assessment or critical appraisal

Mitchell, L. E., & Zajchowski, C. A. (2022). The history of air quality in Utah: A narrative review. Sustainability , 14 (15), 9653. doi.org/10.3390/su14159653

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

"An assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue...using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 100).

- Assessment of what is already known about an issue

- Similar to a systematic review but within a time-constrained setting

- Typically employs methodological shortcuts, increasing risk of introducing bias, includes basic level of quality assessment

- Best suited for issues needing quick decisions and solutions (i.e., policy recommendations)

Learn more about the method:

Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic reviews, 1 (1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries. (2021). Rapid Review Protocol .

Quarmby, S., Santos, G., & Mathias, M. (2019). Air quality strategies and technologies: A rapid review of the international evidence. Sustainability, 11 (10), 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102757

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Developed and refined by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), this review "map[s] out and categorize[s] existing literature on a particular topic, identifying gaps in research literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 97).

Although mapping reviews are sometimes called scoping reviews, the key difference is that mapping reviews focus on a review question, rather than a topic

Mapping reviews are "best used where a clear target for a more focused evidence product has not yet been identified" (Booth, 2016, p. 14)

Mapping review searches are often quick and are intended to provide a broad overview

Mapping reviews can take different approaches in what types of literature is focused on in the search

Cooper I. D. (2016). What is a "mapping study?". Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA , 104 (1), 76–78. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.1.013

Miake-Lye, I. M., Hempel, S., Shanman, R., & Shekelle, P. G. (2016). What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Systematic reviews, 5 (1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x

Tainio, M., Andersen, Z. J., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Hu, L., De Nazelle, A., An, R., ... & de Sá, T. H. (2021). Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence. Environment international , 147 , 105954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105954

Booth, A. (2016). EVIDENT Guidance for Reviewing the Evidence: a compendium of methodological literature and websites . ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1562.9842 .

Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of the 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal , 26(2), 91-108. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

"A type of review that has as its primary objective the identification of the size and quality of research in a topic area in order to inform subsequent review" (Booth et al., 2012, p. 269).

- Main purpose is to map out and categorize existing literature, identify gaps in literature—great for informing policy-making

- Search comprehensiveness determined by time/scope constraints, could take longer than a systematic review

- No formal quality assessment or critical appraisal

Learn more about the methods :

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology , 8 (1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Example :

Rahman, A., Sarkar, A., Yadav, O. P., Achari, G., & Slobodnik, J. (2021). Potential human health risks due to environmental exposure to nano-and microplastics and knowledge gaps: A scoping review. Science of the Total Environment, 757 , 143872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143872

A review that "[compiles] evidence from multiple...reviews into one accessible and usable document" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 103). While originally intended to be a compilation of Cochrane reviews, it now generally refers to any kind of evidence synthesis.

- Compiles evidence from multiple reviews into one document

- Often defines a broader question than is typical of a traditional systematic review

Choi, G. J., & Kang, H. (2022). The umbrella review: a useful strategy in the rain of evidence. The Korean Journal of Pain , 35 (2), 127–128. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2022.35.2.127

Aromataris, E., Fernandez, R., Godfrey, C. M., Holly, C., Khalil, H., & Tungpunkom, P. (2015). Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare , 13(3), 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

Rojas-Rueda, D., Morales-Zamora, E., Alsufyani, W. A., Herbst, C. H., Al Balawi, S. M., Alsukait, R., & Alomran, M. (2021). Environmental risk factors and health: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Dealth , 18 (2), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020704

A meta-analysis is a "technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the result" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 98).

- Statistical technique for combining results of quantitative studies to provide more precise effect of results

- Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching

- Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion criteria

- May be conducted independently or as part of a systematic review

Berman, N. G., & Parker, R. A. (2002). Meta-analysis: Neither quick nor easy. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 2(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-2-10

Hites R. A. (2004). Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the environment and in people: a meta-analysis of concentrations. Environmental Science & Technology , 38 (4), 945–956. https://doi.org/10.1021/es035082g

A systematic review "seeks to systematically search for, appraise, and [synthesize] research evidence, often adhering to the guidelines on the conduct of a review" provided by discipline-specific organizations, such as the Cochrane Collaboration (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 102).

- Aims to compile and synthesize all known knowledge on a given topic

- Adheres to strict guidelines, protocols, and frameworks

- Time-intensive and often takes months to a year or more to complete

- The most commonly referred to type of evidence synthesis. Sometimes confused as a blanket term for other types of reviews

Gascon, M., Triguero-Mas, M., Martínez, D., Dadvand, P., Forns, J., Plasència, A., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2015). Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 12 (4), 4354–4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404354

"Systematized reviews attempt to include one or more elements of the systematic review process while stopping short of claiming that the resultant output is a systematic review" (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 102). When a systematic review approach is adapted to produce a more manageable scope, while still retaining the rigor of a systematic review such as risk of bias assessment and the use of a protocol, this is often referred to as a structured review (Huelin et al., 2015).

- Typically conducted by postgraduate or graduate students

- Often assigned by instructors to students who don't have the resources to conduct a full systematic review

Salvo, G., Lashewicz, B. M., Doyle-Baker, P. K., & McCormack, G. R. (2018). Neighbourhood built environment influences on physical activity among adults: A systematized review of qualitative evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 15 (5), 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050897

Huelin, R., Iheanacho, I., Payne, K., & Sandman, K. (2015). What’s in a name? Systematic and non-systematic literature reviews, and why the distinction matters. https://www.evidera.com/resource/whats-in-a-name-systematic-and-non-systematic-literature-reviews-and-why-the-distinction-matters/

- Review Decision Tree - Cornell University For more information, check out Cornell's review methodology decision tree.

- LitR-Ex.com - Eight literature review methodologies Learn more about 8 different review types (incl. Systematic Reviews and Scoping Reviews) with practical tips about strengths and weaknesses of different methods.

- << Previous: Getting started

- Next: 1. Define your research question >>

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services

- Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

Evidence Synthesis, Systematic Review Services : Literature Review Types, Taxonomies

- Develop a Protocol

- Develop Your Research Question

- Select Databases

- Select Gray Literature Sources

- Write a Search Strategy

- Manage Your Search Process

- Register Your Protocol

- Citation Management

- Article Screening

- Risk of Bias Assessment

- Synthesize, Map, or Describe the Results

- Find Guidance by Discipline

- Manage Your Research Data

- Browse Evidence Portals by Discipline

- Automate the Process, Tools & Technologies

- Adapting Systematic Review Methods

- Additional Resources

Choosing a Literature Review Methodology

Growing interest in evidence-based practice has driven an increase in review methodologies. Your choice of review methodology (or literature review type) will be informed by the intent (purpose, function) of your research project and the time and resources of your team.

- Decision Tree (What Type of Review is Right for You?) Developed by Cornell University Library staff, this "decision-tree" guides the user to a handful of review guides given time and intent.

Types of Evidence Synthesis*

Critical Review - Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or model.

Mapping Review (Systematic Map) - Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature.

Meta-Analysis - Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results.