Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Dr. Karen Palmer

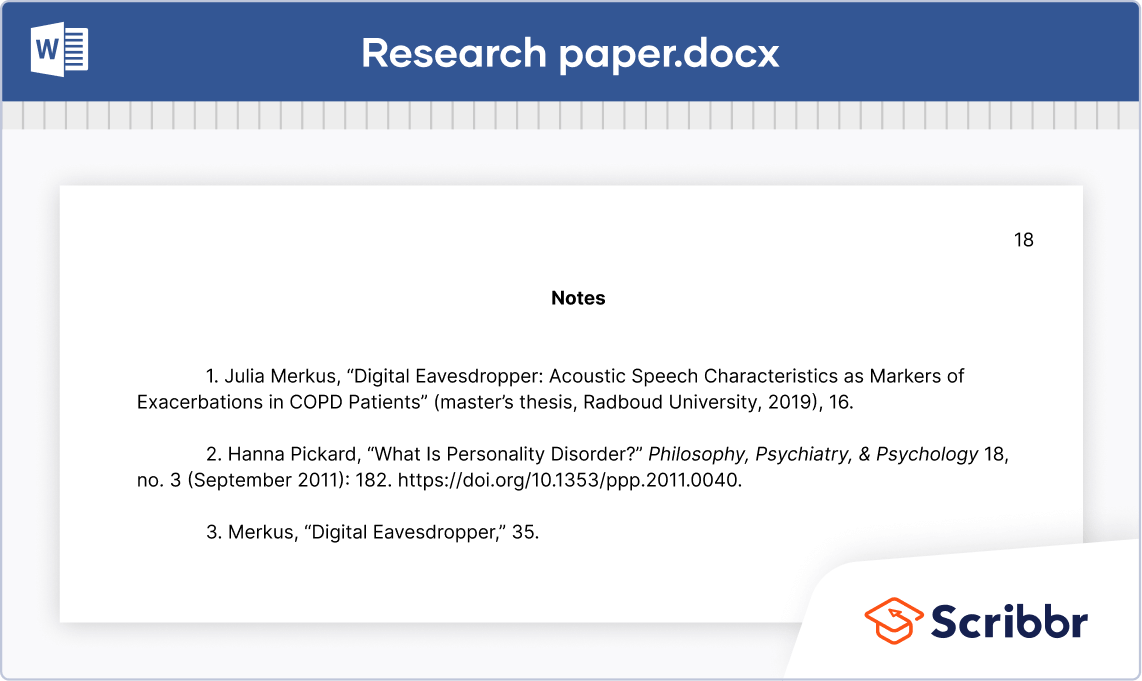

When using research to support your ideas, creating a list of sources is required. No matter what format you are working with (APA, MLA, etc), you will need to create a list of sources at the end of your paper.

Below is a general overview of some of the most common documentation guidelines for creating a list of sources. You can also find the complete instructions for the most common documentation styles at the websites below:

- APA: http://www.apastyle.org

- MLA: http://www.mla.org

- CMS: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org

Some general online searches, especially those conducted on your library databases, are also likely to generate guidelines for a variety of documentation styles. Look for an opportunity to click on a “citation” or “documentation” icon, or ask a member of the library staff for guidance.

You can even get help through the word processing program you typically use. Microsoft Word, for instance, has an entire tab on the taskbar devoted to managing and documenting sources in all three of the styles featured here. Also, don’t forget the free resources that abound on the web from various online writing labs (OWLs) managed by writing programs at colleges and universities across the country.

Citation Machine provides a tool for citing online sources that is particularly helpful.

Developing a List of Sources

Each different documentation style has its own set of guidelines for creating a list of references at the end of the essay (called “works cited” in MLA, “references” in APA, and “bibliography” in CMS).

Source lists should always be in alphabetical order by the first word of each reference, and you should use hanging indentation (with the first line of each reference flush with the margin and subsequent lines indented one-half inch).

- Use the “Insert page” feature to make sure the Works Cited is on its own page at the end of your document. Put your cursor at the end of your paper, then insert a new page. Start typing your list of sources on the new page.

- Center the heading at the top of the page. Follow the guidelines for the documentation style you are using.

- The entire page should be double spaced, just like the rest of your paper.

- Sources should be in alphabetical order.

- Sources should use a Hanging Indent.

Use a Hanging Indent

- Highlight the text you want to format.

- Right click.

- Choose Paragraph.

- Choose Hanging Indent.

1. In your essay rough draft, create a hanging indent.

Additional Resource:

If you don’t know how to cite a certain type of source, please see the OWL at Purdue website: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/resources.html

Attributions

- Overview adapted from “ Chapter 22 ” and licensed under CC BY NC SA .

- Content created by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed CC BY NC SA .

The RoughWriter's Guide Copyright © 2020 by Dr. Karen Palmer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

| Summarizing Conclusion | Impact of social media on adolescents’ mental health | In conclusion, our study has shown that increased usage of social media is significantly associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression among adolescents. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the complex relationship between social media and mental health to develop effective interventions and support systems for this vulnerable population. |

| Editorial Conclusion | Environmental impact of plastic waste | In light of our research findings, it is clear that we are facing a plastic pollution crisis. To mitigate this issue, we strongly recommend a comprehensive ban on single-use plastics, increased recycling initiatives, and public awareness campaigns to change consumer behavior. The responsibility falls on governments, businesses, and individuals to take immediate actions to protect our planet and future generations. |

| Externalizing Conclusion | Exploring applications of AI in healthcare | While our study has provided insights into the current applications of AI in healthcare, the field is rapidly evolving. Future research should delve deeper into the ethical, legal, and social implications of AI in healthcare, as well as the long-term outcomes of AI-driven diagnostics and treatments. Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, medical professionals, and policymakers is essential to harness the full potential of AI while addressing its challenges. |

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to write a high-quality conference paper.

How to write a strong conclusion for your research paper

Last updated

17 February 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Writing a research paper is a chance to share your knowledge and hypothesis. It's an opportunity to demonstrate your many hours of research and prove your ability to write convincingly.

Ideally, by the end of your research paper, you'll have brought your readers on a journey to reach the conclusions you've pre-determined. However, if you don't stick the landing with a good conclusion, you'll risk losing your reader’s trust.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper involves a few important steps, including restating the thesis and summing up everything properly.

Find out what to include and what to avoid, so you can effectively demonstrate your understanding of the topic and prove your expertise.

- Why is a good conclusion important?

A good conclusion can cement your paper in the reader’s mind. Making a strong impression in your introduction can draw your readers in, but it's the conclusion that will inspire them.

- What to include in a research paper conclusion

There are a few specifics you should include in your research paper conclusion. Offer your readers some sense of urgency or consequence by pointing out why they should care about the topic you have covered. Discuss any common problems associated with your topic and provide suggestions as to how these problems can be solved or addressed.

The conclusion should include a restatement of your initial thesis. Thesis statements are strengthened after you’ve presented supporting evidence (as you will have done in the paper), so make a point to reintroduce it at the end.

Finally, recap the main points of your research paper, highlighting the key takeaways you want readers to remember. If you've made multiple points throughout the paper, refer to the ones with the strongest supporting evidence.

- Steps for writing a research paper conclusion

Many writers find the conclusion the most challenging part of any research project . By following these three steps, you'll be prepared to write a conclusion that is effective and concise.

- Step 1: Restate the problem

Always begin by restating the research problem in the conclusion of a research paper. This serves to remind the reader of your hypothesis and refresh them on the main point of the paper.

When restating the problem, take care to avoid using exactly the same words you employed earlier in the paper.

- Step 2: Sum up the paper

After you've restated the problem, sum up the paper by revealing your overall findings. The method for this differs slightly, depending on whether you're crafting an argumentative paper or an empirical paper.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

Argumentative papers involve introducing a thesis statement early on. In crafting the conclusion for an argumentative paper, always restate the thesis, outlining the way you've developed it throughout the entire paper.

It might be appropriate to mention any counterarguments in the conclusion, so you can demonstrate how your thesis is correct or how the data best supports your main points.

Empirical paper: Summarize research findings

Empirical papers break down a series of research questions. In your conclusion, discuss the findings your research revealed, including any information that surprised you.

Be clear about the conclusions you reached, and explain whether or not you expected to arrive at these particular ones.

- Step 3: Discuss the implications of your research

Argumentative papers and empirical papers also differ in this part of a research paper conclusion. Here are some tips on crafting conclusions for argumentative and empirical papers.

Argumentative paper: Powerful closing statement

In an argumentative paper, you'll have spent a great deal of time expressing the opinions you formed after doing a significant amount of research. Make a strong closing statement in your argumentative paper's conclusion to share the significance of your work.

You can outline the next steps through a bold call to action, or restate how powerful your ideas turned out to be.

Empirical paper: Directions for future research

Empirical papers are broader in scope. They usually cover a variety of aspects and can include several points of view.

To write a good conclusion for an empirical paper, suggest the type of research that could be done in the future, including methods for further investigation or outlining ways other researchers might proceed.

If you feel your research had any limitations, even if they were outside your control, you could mention these in your conclusion.

After you finish outlining your conclusion, ask someone to read it and offer feedback. In any research project you're especially close to, it can be hard to identify problem areas. Having a close friend or someone whose opinion you value read the research paper and provide honest feedback can be invaluable. Take note of any suggested edits and consider incorporating them into your paper if they make sense.

- Things to avoid in a research paper conclusion

Keep these aspects to avoid in mind as you're writing your conclusion and refer to them after you've created an outline.

Dry summary

Writing a memorable, succinct conclusion is arguably more important than a strong introduction. Take care to avoid just rephrasing your main points, and don't fall into the trap of repeating dry facts or citations.

You can provide a new perspective for your readers to think about or contextualize your research. Either way, make the conclusion vibrant and interesting, rather than a rote recitation of your research paper’s highlights.

Clichéd or generic phrasing

Your research paper conclusion should feel fresh and inspiring. Avoid generic phrases like "to sum up" or "in conclusion." These phrases tend to be overused, especially in an academic context and might turn your readers off.

The conclusion also isn't the time to introduce colloquial phrases or informal language. Retain a professional, confident tone consistent throughout your paper’s conclusion so it feels exciting and bold.

New data or evidence

While you should present strong data throughout your paper, the conclusion isn't the place to introduce new evidence. This is because readers are engaged in actively learning as they read through the body of your paper.

By the time they reach the conclusion, they will have formed an opinion one way or the other (hopefully in your favor!). Introducing new evidence in the conclusion will only serve to surprise or frustrate your reader.

Ignoring contradictory evidence

If your research reveals contradictory evidence, don't ignore it in the conclusion. This will damage your credibility as an expert and might even serve to highlight the contradictions.

Be as transparent as possible and admit to any shortcomings in your research, but don't dwell on them for too long.

Ambiguous or unclear resolutions

The point of a research paper conclusion is to provide closure and bring all your ideas together. You should wrap up any arguments you introduced in the paper and tie up any loose ends, while demonstrating why your research and data are strong.

Use direct language in your conclusion and avoid ambiguity. Even if some of the data and sources you cite are inconclusive or contradictory, note this in your conclusion to come across as confident and trustworthy.

- Examples of research paper conclusions

Your research paper should provide a compelling close to the paper as a whole, highlighting your research and hard work. While the conclusion should represent your unique style, these examples offer a starting point:

Ultimately, the data we examined all point to the same conclusion: Encouraging a good work-life balance improves employee productivity and benefits the company overall. The research suggests that when employees feel their personal lives are valued and respected by their employers, they are more likely to be productive when at work. In addition, company turnover tends to be reduced when employees have a balance between their personal and professional lives. While additional research is required to establish ways companies can support employees in creating a stronger work-life balance, it's clear the need is there.

Social media is a primary method of communication among young people. As we've seen in the data presented, most young people in high school use a variety of social media applications at least every hour, including Instagram and Facebook. While social media is an avenue for connection with peers, research increasingly suggests that social media use correlates with body image issues. Young girls with lower self-esteem tend to use social media more often than those who don't log onto social media apps every day. As new applications continue to gain popularity, and as more high school students are given smartphones, more research will be required to measure the effects of prolonged social media use.

What are the different kinds of research paper conclusions?

There are no formal types of research paper conclusions. Ultimately, the conclusion depends on the outline of your paper and the type of research you’re presenting. While some experts note that research papers can end with a new perspective or commentary, most papers should conclude with a combination of both. The most important aspect of a good research paper conclusion is that it accurately represents the body of the paper.

Can I present new arguments in my research paper conclusion?

Research paper conclusions are not the place to introduce new data or arguments. The body of your paper is where you should share research and insights, where the reader is actively absorbing the content. By the time a reader reaches the conclusion of the research paper, they should have formed their opinion. Introducing new arguments in the conclusion can take a reader by surprise, and not in a positive way. It might also serve to frustrate readers.

How long should a research paper conclusion be?

There's no set length for a research paper conclusion. However, it's a good idea not to run on too long, since conclusions are supposed to be succinct. A good rule of thumb is to keep your conclusion around 5 to 10 percent of the paper's total length. If your paper is 10 pages, try to keep your conclusion under one page.

What should I include in a research paper conclusion?

A good research paper conclusion should always include a sense of urgency, so the reader can see how and why the topic should matter to them. You can also note some recommended actions to help fix the problem and some obstacles they might encounter. A conclusion should also remind the reader of the thesis statement, along with the main points you covered in the paper. At the end of the conclusion, add a powerful closing statement that helps cement the paper in the mind of the reader.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Writing a Research Paper

This page lists some of the stages involved in writing a library-based research paper.

Although this list suggests that there is a simple, linear process to writing such a paper, the actual process of writing a research paper is often a messy and recursive one, so please use this outline as a flexible guide.

Discovering, Narrowing, and Focusing a Researchable Topic

- Try to find a topic that truly interests you

- Try writing your way to a topic

- Talk with your course instructor and classmates about your topic

- Pose your topic as a question to be answered or a problem to be solved

Finding, Selecting, and Reading Sources

You will need to look at the following types of sources:

- library catalog, periodical indexes, bibliographies, suggestions from your instructor

- primary vs. secondary sources

- journals, books, other documents

Grouping, Sequencing, and Documenting Information

The following systems will help keep you organized:

- a system for noting sources on bibliography cards

- a system for organizing material according to its relative importance

- a system for taking notes

Writing an Outline and a Prospectus for Yourself

Consider the following questions:

- What is the topic?

- Why is it significant?

- What background material is relevant?

- What is my thesis or purpose statement?

- What organizational plan will best support my purpose?

Writing the Introduction

In the introduction you will need to do the following things:

- present relevant background or contextual material

- define terms or concepts when necessary

- explain the focus of the paper and your specific purpose

- reveal your plan of organization

Writing the Body

- Use your outline and prospectus as flexible guides

- Build your essay around points you want to make (i.e., don’t let your sources organize your paper)

- Integrate your sources into your discussion

- Summarize, analyze, explain, and evaluate published work rather than merely reporting it

- Move up and down the “ladder of abstraction” from generalization to varying levels of detail back to generalization

Writing the Conclusion

- If the argument or point of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to add your points up, to explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction.

- Perhaps suggest what about this topic needs further research.

Revising the Final Draft

- Check overall organization : logical flow of introduction, coherence and depth of discussion in body, effectiveness of conclusion.

- Paragraph level concerns : topic sentences, sequence of ideas within paragraphs, use of details to support generalizations, summary sentences where necessary, use of transitions within and between paragraphs.

- Sentence level concerns: sentence structure, word choices, punctuation, spelling.

- Documentation: consistent use of one system, citation of all material not considered common knowledge, appropriate use of endnotes or footnotes, accuracy of list of works cited.

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

How to Write a Research Paper: Parts of the Paper

- Choosing Your Topic

- Citation & Style Guides This link opens in a new window

- Critical Thinking

- Evaluating Information

- Parts of the Paper

- Writing Tips from UNC-Chapel Hill

- Librarian Contact

Parts of the Research Paper Papers should have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Your introductory paragraph should grab the reader's attention, state your main idea, and indicate how you will support it. The body of the paper should expand on what you have stated in the introduction. Finally, the conclusion restates the paper's thesis and should explain what you have learned, giving a wrap up of your main ideas.

1. The Title The title should be specific and indicate the theme of the research and what ideas it addresses. Use keywords that help explain your paper's topic to the reader. Try to avoid abbreviations and jargon. Think about keywords that people would use to search for your paper and include them in your title.

2. The Abstract The abstract is used by readers to get a quick overview of your paper. Typically, they are about 200 words in length (120 words minimum to 250 words maximum). The abstract should introduce the topic and thesis, and should provide a general statement about what you have found in your research. The abstract allows you to mention each major aspect of your topic and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Because it is a summary of the entire research paper, it is often written last.

3. The Introduction The introduction should be designed to attract the reader's attention and explain the focus of the research. You will introduce your overview of the topic, your main points of information, and why this subject is important. You can introduce the current understanding and background information about the topic. Toward the end of the introduction, you add your thesis statement, and explain how you will provide information to support your research questions. This provides the purpose and focus for the rest of the paper.

4. Thesis Statement Most papers will have a thesis statement or main idea and supporting facts/ideas/arguments. State your main idea (something of interest or something to be proven or argued for or against) as your thesis statement, and then provide your supporting facts and arguments. A thesis statement is a declarative sentence that asserts the position a paper will be taking. It also points toward the paper's development. This statement should be both specific and arguable. Generally, the thesis statement will be placed at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. The remainder of your paper will support this thesis.

Students often learn to write a thesis as a first step in the writing process, but often, after research, a writer's viewpoint may change. Therefore a thesis statement may be one of the final steps in writing.

Examples of Thesis Statements from Purdue OWL

5. The Literature Review The purpose of the literature review is to describe past important research and how it specifically relates to the research thesis. It should be a synthesis of the previous literature and the new idea being researched. The review should examine the major theories related to the topic to date and their contributors. It should include all relevant findings from credible sources, such as academic books and peer-reviewed journal articles. You will want to:

- Explain how the literature helps the researcher understand the topic.

- Try to show connections and any disparities between the literature.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

More about writing a literature review. . .

6. The Discussion The purpose of the discussion is to interpret and describe what you have learned from your research. Make the reader understand why your topic is important. The discussion should always demonstrate what you have learned from your readings (and viewings) and how that learning has made the topic evolve, especially from the short description of main points in the introduction.Explain any new understanding or insights you have had after reading your articles and/or books. Paragraphs should use transitioning sentences to develop how one paragraph idea leads to the next. The discussion will always connect to the introduction, your thesis statement, and the literature you reviewed, but it does not simply repeat or rearrange the introduction. You want to:

- Demonstrate critical thinking, not just reporting back facts that you gathered.

- If possible, tell how the topic has evolved over the past and give it's implications for the future.

- Fully explain your main ideas with supporting information.

- Explain why your thesis is correct giving arguments to counter points.

7. The Conclusion A concluding paragraph is a brief summary of your main ideas and restates the paper's main thesis, giving the reader the sense that the stated goal of the paper has been accomplished. What have you learned by doing this research that you didn't know before? What conclusions have you drawn? You may also want to suggest further areas of study, improvement of research possibilities, etc. to demonstrate your critical thinking regarding your research.

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 13, 2024 8:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucc.edu/research_paper

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

Academic integrity and documentation, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

Types of Documentation

Bibliographies and Source Lists

What is a bibliography.

A bibliography is a list of books and other source material that you have used in preparing a research paper. Sometimes these lists will include works that you consulted but did not cite specifically in your assignment. Consult the style guide required for your assignment to determine the specific title of your bibliography page as well as how to cite each source type. Bibliographies are usually placed at the end of your research paper.

What is an annotated bibliography?

A special kind of bibliography, the annotated bibliography, is often used to direct your readers to other books and resources on your topic. An instructor may ask you to prepare an annotated bibliography to help you narrow down a topic for your research assignment. Such bibliographies offer a few lines of information, typically 150-300 words, summarizing the content of the resource after the bibliographic entry.

Example of Annotated Bibliographic Entry in MLA Style

Waddell, Marie L., Robert M. Esch, and Roberta R. Walker. The Art of Styling Sentences: 20 Patterns for Success. 3rd ed. New York: Barron’s, 1993. A comprehensive look at 20 sentence patterns and their variations to teach students how to write effective sentences by imitating good style.

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper

Do not try to “wow” your instructor with a long bibliography when your instructor requests only a works cited page. It is tempting, after doing a lot of work to research a paper, to try to include summaries on each source as you write your paper so that your instructor appreciates how much work you did. That is a trap you want to avoid. MLA style, the one that is most commonly followed in high schools and university writing courses, dictates that you include only the works you actually cited in your paper—not all those that you used.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, assembling bibliographies and works cited.

- If your assignment calls for a bibliography, list all the sources you consulted in your research.

- If your assignment calls for a works cited or references page, include only the sources you quote, summarize, paraphrase, or mention in your paper.

- If your works cited page includes a source that you did not cite in your paper, delete it.

- All in-text citations that you used at the end of quotations, summaries, and paraphrases to credit others for their ideas,words, and work must be accompanied by a cited reference in the bibliography or works cited. These references must include specific information about the source so that your readers can identify precisely where the information came from.The citation entries on a works cited page typically include the author’s name, the name of the article, the name of the publication, the name of the publisher (for books), where it was published (for books), and when it was published.

The good news is that you do not have to memorize all the many ways the works cited entries should be written. Numerous helpful style guides are available to show you the information that should be included, in what order it should appear, and how to format it. The format often differs according to the style guide you are using. The Modern Language Association (MLA) follows a particular style that is a bit different from APA (American Psychological Association) style, and both are somewhat different from the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS). Always ask your teacher which style you should use.

A bibliography usually appears at the end of a paper on its own separate page. All bibliography entries—books, periodicals, Web sites, and nontext sources such radio broadcasts—are listed together in alphabetical order. Books and articles are alphabetized by the author’s last name.

Most teachers suggest that you follow a standard style for listing different types of sources. If your teacher asks you to use a different form, however, follow his or her instructions. Take pride in your bibliography. It represents some of the most important work you’ve done for your research paper—and using proper form shows that you are a serious and careful researcher.

Bibliography Entry for a Book

A bibliography entry for a book begins with the author’s name, which is written in this order: last name, comma, first name, period. After the author’s name comes the title of the book. If you are handwriting your bibliography, underline each title. If you are working on a computer, put the book title in italicized type. Be sure to capitalize the words in the title correctly, exactly as they are written in the book itself. Following the title is the city where the book was published, followed by a colon, the name of the publisher, a comma, the date published, and a period. Here is an example:

Format : Author’s last name, first name. Book Title. Place of publication: publisher, date of publication.

- A book with one author : Hartz, Paula. Abortion: A Doctor’s Perspective, a Woman’s Dilemma . New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1992.

- A book with two or more authors : Landis, Jean M. and Rita J. Simon. Intelligence: Nature or Nurture? New York: HarperCollins, 1998.

Bibliography Entry for a Periodical

A bibliography entry for a periodical differs slightly in form from a bibliography entry for a book. For a magazine article, start with the author’s last name first, followed by a comma, then the first name and a period. Next, write the title of the article in quotation marks, and include a period (or other closing punctuation) inside the closing quotation mark. The title of the magazine is next, underlined or in italic type, depending on whether you are handwriting or using a computer, followed by a period. The date and year, followed by a colon and the pages on which the article appeared, come last. Here is an example:

Format: Author’s last name, first name. “Title of the Article.” Magazine. Month and year of publication: page numbers.

- Article in a monthly magazine : Crowley, J.E.,T.E. Levitan and R.P. Quinn.“Seven Deadly Half-Truths About Women.” Psychology Today March 1978: 94–106.

- Article in a weekly magazine : Schwartz, Felice N.“Management,Women, and the New Facts of Life.” Newsweek 20 July 2006: 21–22.

- Signed newspaper article : Ferraro, Susan. “In-law and Order: Finding Relative Calm.” The Daily News 30 June 1998: 73.

- Unsigned newspaper article : “Beanie Babies May Be a Rotten Nest Egg.” Chicago Tribune 21 June 2004: 12.

Bibliography Entry for a Web Site

For sources such as Web sites include the information a reader needs to find the source or to know where and when you found it. Always begin with the last name of the author, broadcaster, person you interviewed, and so on. Here is an example of a bibliography for a Web site:

Format : Author.“Document Title.” Publication or Web site title. Date of publication. Date of access.

Example : Dodman, Dr. Nicholas. “Dog-Human Communication.” Pet Place . 10 November 2006. 23 January 2014 < http://www.petplace.com/dogs/dog-human-communication-2/page1.aspx >

After completing the bibliography you can breathe a huge sigh of relief and pat yourself on the back. You probably plan to turn in your work in printed or handwritten form, but you also may be making an oral presentation. However you plan to present your paper, do your best to show it in its best light. You’ve put a great deal of work and thought into this assignment, so you want your paper to look and sound its best. You’ve completed your research paper!

Back to How To Write A Research Paper .

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

APA Formatting and Style Guide (7th Edition)

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

In-Text Citations

Resources on using in-text citations in APA style

Reference List

Resources on writing an APA style reference list, including citation formats

Other APA Resources

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 11. Citing Sources

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A citation is a formal reference to a published or unpublished source that you consulted and obtained information from while writing your research paper. It refers to a source of information that supports a factual statement, proposition, argument, or assertion or any quoted text obtained from a book, article, web site, or any other type of material . In-text citations are embedded within the body of your paper and use a shorthand notation style that refers to a complete description of the item at the end of the paper. Materials cited at the end of a paper may be listed under the heading References, Sources, Works Cited, or Bibliography. Rules on how to properly cite a source depends on the writing style manual your professor wants you to use for the class [e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago, Turabian, etc.]. Note that some disciplines have their own citation rules [e.g., law].

Citations: Overview. OASIS Writing Center, Walden University; Research and Citation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Citing Sources. University Writing Center, Texas A&M University.

Citing Your Sources

Reasons for Citing Sources in Your Research Paper

English scientist, Sir Isaac Newton, once wrote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”* Citations support learning how to "see further" through processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time and the subsequent ways this leads to the devarication of new knowledge.

Listed below are specific reasons why citing sources is an important part of doing good research.

- Shows the reader where to find more information . Citations help readers expand their understanding and knowledge about the issues being investigated. One of the most effective strategies for locating authoritative, relevant sources about a research problem is to review materials cited in studies published by other authors. In this way, the sources you cite help the reader identify where to go to examine the topic in more depth and detail.

- Increases your credibility as an author . Citations to the words, ideas, and arguments of scholars demonstrates that you have conducted a thorough review of the literature and, therefore, you are reporting your research results or proposing recommended courses of action from an informed and critically engaged perspective. Your citations offer evidence that you effectively contemplated, evaluated, and synthesized sources of information in relation to your conceptualization of the research problem.

- Illustrates the non-linear and contested nature of knowledge creation . The sources you cite show the reader how you characterized the dynamics of prior knowledge creation relevant to the research problem and how you managed to identify the contested relationships between problems and solutions proposed among scholars. Citations don't just list materials used in your study, they tell a story about how prior knowledge-making emerged from a constant state of creation, renewal, and transformation.

- Reinforces your arguments . Sources cited in your paper provide the evidence that readers need to determine that you properly addressed the “So What?” question. This refers to whether you considered the relevance and significance of the research problem, its implications applied to creating new knowledge, and its importance for improving practice. In this way, citations draw attention to and support the legitimacy and originality of your own ideas and assertions.

- Demonstrates that you "listened" to relevant conversations among scholars before joining in . Your citations tell the reader where you developed an understanding of the debates among scholars. They show how you educated yourself about ongoing conversations taking place within relevant communities of researchers before inserting your own ideas and arguments. In peer-reviewed scholarship, most of these conversations emerge within books, research reports, journal articles, and other cited works.

- Delineates alternative approaches to explaining the research problem . If you disagree with prior research assumptions or you believe that a topic has been understudied or you find that there is a gap in how scholars have understood a problem, your citations serve as the source materials from which to analyze and present an alternative viewpoint or to assert that a different course of action should be pursued. In short, the materials you cite serve as the means by which to argue persuasively against long-standing assumptions promulgated in prior studies.

- Helps the reader understand contextual aspects of your research . Cited sources help readers understand the specific circumstances, conditions, and settings of the problem being investigated and, by extension, how your arguments can be fully understood and assessed. Citations place your line of reasoning within a specific contextualized framework based on how others have studied the problem and how you interpreted their findings in support of your overall research objectives.

- Frames the development of concepts and ideas within the literature . No topic in the social and behavioral sciences rests in isolation from research that has taken place in the past. Your citations help the reader understand the growth and transformation of the theoretical assumptions, key concepts, and systematic inquiries that emerged prior to your engagement with the research problem.

- Underscores sources that were most important to you . Your citations represent a set of choices made about what you determined to be the most important sources for understanding the topic. They not only list what you discovered, but why it matters and how the materials you chose to cite fit within the broader context of your research design and arguments. As part of an overall assessment of the study’s validity and reliability , the choices you make also helps the reader determine what sources of research may have been excluded.

- Provides evidence of interdisciplinary thinking . An important principle of good research is to extend your review of the literature beyond the predominant disciplinary space where scholars have previously examined a topic. Citations provide evidence that you have integrated epistemological arguments, observations, and/or methodological strategies of other disciplines into your paper, thereby demonstrating that you understand the complex, interconnected nature of contemporary research topics.

- Forms the basis for bibliometric analysis of research . Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative method used, for example, to identify and predict emerging trends in research, document patterns of collaboration among scholars, explore the intellectual structure of a specific domain of research, map the development of research within and across disciplines, or identify gaps in knowledge within the literature. Bibliometrics data can also be used to visually map relationships among published studies. An author's citations to books, journal articles, research reports, and other publications represent the raw data used in bibliometric research.

- Supports critical thinking and independent learning . Evaluating the authenticity, reliability, validity, and originality of prior research is an act of interpretation and introspective reasoning applied to assessing whether a source of information will contribute to understanding the problem in ways that are persuasive and align with your overall research objectives. Reviewing and citing prior studies represents a deliberate act of critically scrutinizing each source as part of your overall assessment of how scholars have confronted the research problem.

- Honors the achievements of others . As Susan Blum recently noted,** citations not only identify sources used, they acknowledge the achievements of scholars within the larger network of research about the topic. Citing sources is a normative act of professionalism within academe and a way to highlight and recognize the work of scholars who likely do not obtain any tangible benefits or monetary value from their research endeavors. Your citations help to validate the work of others.

*Vernon. Jamie L. "On the Shoulder of Giants." American Scientist 105 (July-August 2017): 194.

**Blum, Susan D. "In Defense of the Morality of Citation.” Inside Higher Ed , January 29, 2024.

Aksnes, Dag W., Liv Langfeldt, and Paul Wouters. "Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic Concepts and Theories." Sage Open 9 (January-March 2019): https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019829575; Blum, Susan Debra. My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009; Bretag, Tracey., editor. Handbook of Academic Integrity . Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020; Ballenger, Bruce P. The Curious Researcher: A Guide to Writing Research Papers . 7th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2012; D'Angelo, Barbara J. "Using Source Analysis to Promote Critical Thinking." Research Strategies 18 (Winter 2001): 303-309; Donthu, Naveen et al. “How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines.” Journal of Business Research 133 (2021): 285-296; Mauer, Barry and John Venecek. “Scholarship as Conversation.” Strategies for Conducting Literary Research, University of Central Florida, 2021; Öztürk, Oguzhan, Ridvan Kocaman, and Dominik K. Kanbach. "How to Design Bibliometric Research: An Overview and a Framework Proposal." Review of Managerial Science (2024): 1-29; Why Cite? Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale University; Citing Information. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Harvard College Writing Program. Harvard University; Newton, Philip. "Academic Integrity: A Quantitative Study of Confidence and Understanding in Students at the Start of Their Higher Education." Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (2016): 482-497; Referencing More Effectively. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Using Sources. Yale College Writing Center. Yale University; Vosburgh, Richard M. "Closing the Academic-practitioner Gap: Research Must Answer the “SO WHAT” Question." H uman Resource Management Review 32 (March 2022): 100633; When and Why to Cite Sources. Information Literacy Playlists, SUNY, Albany Libraries.

Structure and Writing Style

Referencing your sources means systematically showing what information or ideas you acquired from another author’s work, and identifying where that information come from . You must cite research in order to do research, but at the same time, you must delineate what are your original thoughts and ideas and what are the thoughts and ideas of others. Citations help achieve this. Procedures used to cite sources vary among different fields of study. If not outlined in your course syllabus or writing assignment, always speak with your professor about what writing style for citing sources should be used for the class because it is important to fully understand the citation style to be used in your paper, and to apply it consistently. If your professor defers and tells you to "choose whatever you want, just be consistent," then choose the citation style you are most familiar with or that is appropriate to your major [e.g., use Chicago style if you are majoring in history; use APA if its an education course; use MLA if it is literature or a general writing course].

GENERAL GUIDELINES

1. Are there any reasons I should avoid referencing other people's work? No. If placed in the proper context, r eferencing other people's research is never an indication that your work is substandard or lacks originality. In fact, the opposite is true. If you write your paper without adequate references to previous studies, you are signaling to the reader that you are not familiar with the literature on the topic, thereby, undermining the validity of your study and your credibility as a researcher. Including references in academic writing is one of the most important ways to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of how the research problem has been addressed. It is the intellectual packaging around which you present your thoughts, ideas, and arguments to the reader.

2. What should I do if I find out that my great idea has already been studied by another researcher? It can be frustrating to come up with what you believe is a great topic only to find that it's already been thoroughly studied. However, do not become frustrated by this. You can acknowledge the prior research by writing in the text of your paper [see also Smith, 2002], then citing the complete source in your list of references. Use the discovery of prior studies as an opportunity to demonstrate the significance of the problem being investigated and, if applicable, as a means of delineating your analysis from those of others [e.g., the prior study is ten years old and doesn't take into account new variables]. Strategies for responding to prior research can include: stating how your study updates previous understandings about the topic, offering a new or different perspective, applying a different or innovative method of gathering and interpreting data, and/or describing a new set of insights, guidelines, recommendations, best practices, or working solutions.

3. What should I do if I want to use an adapted version of someone else's work? You still must cite the original work. For example, you use a table of statistics from a journal article published in 1996 by author Smith, but you have altered or added new data to it. Reference the revised chart, such as, [adapted from Smith, 1996], then cite the original source in your list of references. You can also use other terms in order to specify the exact relationship between the original source and the version you have presented, such as, "based on data from Smith [1996]...," or "summarized from Smith [1996]...." Citing the original source helps the reader locate where the information was first presented and under what context it was used as well as to evaluate how effectively you applied it to your own research.

4. What should I do if several authors have published very similar information or ideas? You can indicate that the topic, idea, concept, or information can be found in the works of others by stating something similar to the following example: "Though many scholars have applied rational choice theory to understanding economic relations among nations [Smith, 1989; Jones, 1991; Johnson, 1994; Anderson, 2003; Smith, 2014], little attention has been given to applying the theory to examining the influence of non-governmental organizations in a globalized economy." If you only reference one author or only the most recent study, then your readers may assume that only one author has published on this topic, or more likely, they will conclude that you have not conducted a thorough review of the literature. Referencing all relevant authors of prior studies gives your readers a clear idea of the breadth of analysis you conducted in preparing to study the research problem. If there has been a significant number of prior studies on the topic [i.e., ten or more], describe the most comprehensive and recent works because they will presumably discuss and reference the older studies. However, note in your review of the literature that there has been significant scholarship devoted to the topic so the reader knows that you are aware of the numerous prior studies.

5. What if I find exactly what I want to say in the writing of another researcher? In the social sciences, the rationale in duplicating prior research is generally governed by the passage of time, changing circumstances or conditions, or the emergence of variables that necessitate new investigations . If someone else has recently conducted a thorough investigation of precisely the same research problem that you intend to study, then you likely will have to revise your topic, or at the very least, review this literature to identify something new to say about the problem. However, if it is someone else's particularly succinct expression, but it fits perfectly with what you are trying to say, then you can quote from the author directly, referencing the source. Identifying an author who has made the exact same point that you want to make can be an opportunity to validate, as well as reinforce the significance of, the research problem you are investigating. The key is to build on that idea in new and innovative ways. If you are not sure how to do this, consult with a librarian .