- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Why publish with Food Quality and Safety

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Food Quality and Safety

- About Zhejiang University Press

- Editorial Board

- Outstanding Reviewers

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, organic farming process, benefits of organic farming, organic agriculture and sustainable development, status of organic farming in india: production, popularity, and economic growth, future prospects of organic farming in india, conclusions, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

Organic farming in India: a vision towards a healthy nation

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Suryatapa Das, Annalakshmi Chatterjee, Tapan Kumar Pal, Organic farming in India: a vision towards a healthy nation, Food Quality and Safety , Volume 4, Issue 2, May 2020, Pages 69–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/fqsafe/fyaa018

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Food quality and safety are the two important factors that have gained ever-increasing attention in general consumers. Conventionally grown foods have immense adverse health effects due to the presence of higher pesticide residue, more nitrate, heavy metals, hormones, antibiotic residue, and also genetically modified organisms. Moreover, conventionally grown foods are less nutritious and contain lesser amounts of protective antioxidants. In the quest for safer food, the demand for organically grown foods has increased during the last decades due to their probable health benefits and food safety concerns. Organic food production is defined as cultivation without the application of chemical fertilizers and synthetic pesticides or genetically modified organisms, growth hormones, and antibiotics. The popularity of organically grown foods is increasing day by day owing to their nutritional and health benefits. Organic farming also protects the environment and has a greater socio-economic impact on a nation. India is a country that is bestowed with indigenous skills and potentiality for growth in organic agriculture. Although India was far behind in the adoption of organic farming due to several reasons, presently it has achieved rapid growth in organic agriculture and now becomes one of the largest organic producers in the world. Therefore, organic farming has a great impact on the health of a nation like India by ensuring sustainable development.

Food quality and safety are two vital factors that have attained constant attention in common people. Growing environmental awareness and several food hazards (e.g. dioxins, bovine spongiform encephalopathy, and bacterial contamination) have substantially decreased the consumer’s trust towards food quality in the last decades. Intensive conventional farming can add contamination to the food chain. For these reasons, consumers are quested for safer and better foods that are produced through more ecologically and authentically by local systems. Organically grown food and food products are believed to meet these demands ( Rembialkowska, 2007 ).

In recent years, organic farming as a cultivation process is gaining increasing popularity ( Dangour et al. , 2010 ). Organically grown foods have become one of the best choices for both consumers and farmers. Organically grown foods are part of go green lifestyle. But the question is that what is meant by organic farming? ( Chopra et al. , 2013 ).

The term ‘organic’ was first coined by Northbourne, in 1940, in his book entitled ‘Look to the Land’.

Northbourne stated that ‘the farm itself should have biological completeness; it must be a living entity; it must be a unit which has within itself a balanced organic life’( Nourthbourne, 2003 ). Northbourne also defined organic farming as ‘an ecological production management system that promotes and enhances biodiversity, biological cycles and soil biological activity’. According to Winter and Davis (2006) , ‘it is based on minimal use of off-farm inputs and on management practices that restore, maintain and enhance ecological harmony’.

They mentioned that organic produce is not grown with synthetic pesticides, antibiotics, growth hormones, application of genetic modification techniques (such as genetically modified crops), sewage sludge, or chemical fertilizers.

Whereas, conventional farming is the cultivation process where synthetic pesticide and chemical fertilizers are applied to gain higher crop yield and profit. In conventional farming, synthetic pesticides and chemicals are able to eliminate insects, weeds, and pests and growth factors such as synthetic hormones and fertilizers increase growth rate ( Worthington, 2001 ).

As synthetically produced pesticides and chemical fertilizers are utilized in conventional farming, consumption of conventionally grown foods is discouraged, and for these reasons, the popularity of organic farming is increasing gradually.

Organic farming and food processing practices are wide-ranging and necessitate the development of socially, ecologically, and economically sustainable food production system. The International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) has suggested the basic four principles of organic farming, i.e. the principle of health, ecology, fairness, and care ( Figure 1 ). The main principles and practices of organic food production are to inspire and enhance biological cycles in the farming system, keep and enhance deep-rooted soil fertility, reduce all types of pollution, evade the application of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, conserve genetic diversity in food, consider the vast socio-ecological impact of food production, and produce high-quality food in sufficient quantity ( IFOAM, 1998 ).

Principles of organic farming (adapted from IFOAM, 1998 ).

According to the National Organic Programme implemented by USDA Organic Food Production Act (OFPA, 1990), agriculture needs specific prerequisites for both crop cultivation and animal husbandry. To be acceptable as organic, crops should be cultivated in lands without any synthetic pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and herbicides for 3 years before harvesting with enough buffer zone to lower contamination from the adjacent farms. Genetically engineered products, sewage sludge, and ionizing radiation are strictly prohibited. Fertility and nutrient content of soil are managed primarily by farming practices, with crop rotation, and using cover crops that are boosted with animal and plant waste manures. Pests, diseases, and weeds are mainly controlled with the adaptation of physical and biological control systems without using herbicides and synthetic pesticides. Organic livestock should be reared devoid of scheduled application of growth hormones or antibiotics and they should be provided with enough access to the outdoor. Preventive health practices such as routine vaccination, vitamins and minerals supplementation are also needed (OFPA, 1990).

Nutritional benefits and health safety

Magnusson et al. (2003) and Brandt and MØlgaord (2001) mentioned that the growing demand for organically farmed fresh products has created an interest in both consumer and producer regarding the nutritional value of organically and conventionally grown foods. According to a study conducted by AFSSA (2003) , organically grown foods, especially leafy vegetables and tubers, have higher dry matter as compared to conventionally grown foods. Woëse et al. (1997) and Bourn and Prescott (2002) also found similar results. Although organic cereals and their products contain lesser protein than conventional cereals, they have higher quality proteins with better amino acid scores. Lysine content in organic wheat has been reported to be 25%–30% more than conventional wheat ( Woëse et al. , 1997 ; Brandt et al. , 2000 ).

Organically grazed cows and sheep contain less fat and more lean meat as compared to conventional counterparts ( Hansson et al. , 2000 ). In a study conducted by Nürnberg et al. (2002) , organically fed cow’s muscle contains fourfold more linolenic acid, which is a recommended cardio-protective ω-3 fatty acid, with accompanying decrease in oleic acid and linoleic acid. Pastushenko et al. (2000) found that meat from an organically grazed cow contains high amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids. The milk produced from the organic farm contains higher polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E ( Lund, 1991 ). Vitamin E and carotenoids are found in a nutritionally desirable amount in organic milk ( Nürnberg et al. , 2002 ). Higher oleic acid has been found in organic virgin olive oil ( Gutierrez et al. , 1999 ). Organic plants contain significantly more magnesium, iron, and phosphorous. They also contain more calcium, sodium, and potassium as major elements and manganese, iodine, chromium, molybdenum, selenium, boron, copper, vanadium, and zinc as trace elements ( Rembialkowska, 2007 ).

According to a review of Lairon (2010) which was based on the French Agency for food safety (AFSSA) report, organic products contain more dry matter, minerals, and antioxidants such as polyphenols and salicylic acid. Organic foods (94%–100%) contain no pesticide residues in comparison to conventionally grown foods.

Fruits and vegetables contain a wide variety of phytochemicals such as polyphenols, resveratrol, and pro-vitamin C and carotenoids which are generally secondary metabolites of plants. In a study of Lairon (2010) , organic fruits and vegetables contain 27% more vitamin C than conventional fruits and vegetables. These secondary metabolites have substantial regulatory effects at cellular levels and hence found to be protective against certain diseases such as cancers, chronic inflammations, and other diseases ( Lairon, 2010 ).

According to a Food Marketing Institute (2008) , some organic foods such as corn, strawberries, and marionberries have greater than 30% of cancer-fighting antioxidants. The phenols and polyphenolic antioxidants are in higher level in organic fruits and vegetables. It has been estimated that organic plants contain double the amount of phenolic compounds than conventional ones ( Rembialkowska, 2007 ). Organic wine has been reported to contain a higher level of resveratrol ( Levite et al. , 2000 ).

Rossi et al. (2008) stated that organically grown tomatoes contain more salicylic acid than conventional counterparts. Salicylic acid is a naturally occurring phytochemical having anti-inflammatory and anti-stress effects and prevents hardening of arteries and bowel cancer ( Rembialkowska, 2007 ; Butler et al. , 2008 ).

Total sugar content is more in organic fruits because of which they taste better to consumers. Bread made from organically grown grain was found to have better flavour and also had better crumb elasticity ( BjØrn and Fruekidle, 2003 ). Organically grown fruits and vegetables have been proved to taste better and smell good ( Rembialkowska, 2000 ).

Organic vegetables normally have far less nitrate content than conventional vegetables ( Woëse et al. , 1997 ). Nitrates are used in farming as soil fertilizer but they can be easily transformed into nitrites, a matter of public health concern. Nitrites are highly reactive nitrogen species that are capable of competing with oxygen in the blood to bind with haemoglobin, thus leading to methemoglobinemia. It also binds to the secondary amine to generate nitrosamine which is a potent carcinogen ( Lairon, 2010 ).

As organically grown foods are cultivated without the use of pesticides and sewage sludge, they are less contaminated with pesticide residue and pathogenic organisms such as Listeria monocytogenes or Salmonella sp. or Escherichia coli ( Van Renterghem et al. , 1991 ; Lung et al. , 2001 ; Warnick et al. , 2001 ).

Therefore, organic foods ensure better nutritional benefits and health safety.

Environmental impact

Organic farming has a protective role in environmental conservation. The effect of organic and conventional agriculture on the environment has been extensively studied. It is believed that organic farming is less harmful to the environment as it does not allow synthetic pesticides, most of which are potentially harmful to water, soil, and local terrestrial and aquatic wildlife ( Oquist et al. , 2007 ). In addition, organic farms are better than conventional farms at sustaining biodiversity, due to practices of crop rotation. Organic farming improves physico-biological properties of soil consisting of more organic matter, biomass, higher enzyme, better soil stability, enhanced water percolation, holding capacities, lesser water, and wind erosion compared to conventionally farming soil ( Fliessbach & Mäder, 2000 ; Edwards, 2007 ; Fileβbach et al. , 2007 ). Organic farming uses lesser energy and produces less waste per unit area or per unit yield ( Stolze et al. , 2000 ; Hansen et al. , 2001 ). In addition, organically managed soils are of greater quality and water retention capacity, resulting in higher yield in organic farms even during the drought years ( Pimentel et al. , 2005 ).

Socioeconomic impact

Organic cultivation requires a higher level of labour, hence produces more income-generating jobs per farm ( Halberg, 2008 ). According to Winter and Davis (2006), an organic product typically costs 10%–40% more than the similar conventionally crops and it depends on multiple factors both in the input and the output arms. On the input side, factors that enhance the price of organic foods include the high cost of obtaining the organic certification, the high cost of manpower in the field, lack of subsidies on organics in India, unlike chemical inputs. But consumers are willing to pay a high price as there is increasing health awareness. Some organic products also have short supply against high demand with a resultant increase in cost ( Mukherjee et al. , 2018 ).

Biofertilizers and pesticides can be produced locally, so yearly inputs invested by the farmers are also low ( Lobley et al. , 2005 ). As the labours working in organic farms are less likely to be exposed to agricultural chemicals, their occupational health is improved ( Thompson and Kidwell, 1998 ). Organic food has a longer shelf life than conventional foods due to lesser nitrates and greater antioxidants. Nitrates hasten food spoilage, whereas antioxidants help to enhance the shelf life of foods ( Shreck et al. , 2006 ). Organic farming is now an expanding economic sector as a result of the profit incurred by organic produce and thereby leading to a growing inclination towards organic agriculture by the farmers.

The concept of sustainable agriculture integrates three main goals—environmental health, economic profitability, and social and economic equity. The concept of sustainability rests on the principle that we must meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The very basic approach to organic farming for the sustainable environment includes the following ( Yadav, 2017 ):

Improvement and maintenance of the natural landscape and agro-ecosystem.

Avoidance of overexploitation and pollution of natural resources.

Minimization of the consumption of non-renewable energy resources.

Exploitation synergies that exist in a natural ecosystem.

Maintenance and improve soil health by stimulating activity or soil organic manures and avoid harming them with pesticides.

Optimum economic returns, with a safe, secure, and healthy working environment.

Acknowledgement of the virtues of indigenous know-how and traditional farming system.

Long-term economic viability can only be possible by organic farming and because of its premium price in the market, organic farming is more profitable. The increase in the cost of production by the use of pesticides and fertilizers in conventional farming and its negative impact on farmer’s health affect economic balance in a community and benefits only go to the manufacturer of these pesticides. Continuous degradation of soil fertility by chemical fertilizers leads to production loss and hence increases the cost of production which makes the farming economically unsustainable. Implementation of a strategy encompassing food security, generation of rural employment, poverty alleviation, conservation of the natural resource, adoption of an export-oriented production system, sound infrastructure, active participation of government, and private-public sector will be helpful to make revamp economic sustainability in agriculture ( Soumya, 2015 ).

Social sustainability

It is defined as a process or framework that promotes the wellbeing of members of an organization while supporting the ability of future generations to maintain a healthy community. Social sustainability can be improved by enabling rural poor to get benefit from agricultural development, giving respect to indigenous knowledge and practices along with modern technologies, promoting gender equality in labour, full participation of vibrant rural communities to enhance their confidence and mental health, and thus decreasing suicidal rates among the farmers. Organic farming appears to generate 30% more employment in rural areas and labour achieves higher returns per unit of labour input ( Pandey and Singh, 2012 ).

Organic food and farming have continued to grow across the world. Since 1985, the total area of farmland under organic production has been increased steadily over the last three decades ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ). By 2017, there was a total of 69.8 million hectares of organically managed land recorded globally which represents a 20% growth or 11.7 million hectares of land in comparison to the year 2016. This is the largest growth ever recorded in organic farming ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ). The countries with the largest areas of organic agricultural land recorded in the year 2017 are given in Figure 2 . Australia has the largest organic lands with an area of 35.65 million hectares and India acquired the eighth position with a total organic agriculture area of 1.78 million hectares ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ).

Country-wise areas of organic agriculture land, 2017 ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ).

In 2017, it was also reported that day to day the number of organic produces increases considerably all over the world. Asia contributes to the largest percentage (40%) of organic production in the world and India contributes to be largest number of organic producer (835 000) ( Figures 3 and 4 ).

Organic producers by region, 2017 ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ).

Largest organic producers in the world, 2017 ( Willer and Lernoud, 2017 ).

The growth of organic farming in India was quite dawdling with only 41 000 hectares of organic land comprising merely 0.03% of the total cultivated area. In India during 2002, the production of organic farming was about 14 000 tonnes of which 85% of it was exported ( Chopra et al. , 2013 ). The most important barrier considered in the progress of organic agriculture in India was the lacunae in the government policies of making a firm decision to promote organic agriculture. Moreover, there were several major drawbacks in the growth of organic farming in India which include lack of awareness, lack of good marketing policies, shortage of biomass, inadequate farming infrastructure, high input cost of farming, inappropriate marketing of organic input, inefficient agricultural policies, lack of financial support, incapability of meeting export demand, lack of quality manure, and low yield ( Figure 5 ; Bhardwaj and Dhiman, 2019 ).

Constraints of organic farming in India in the past ( Bhardwaj and Dhiman, 2019 ).

Recently, the Government of India has implemented a number of programs and schemes for boosting organic farming in the country. Among these the most important include (1) The Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana, (2) Organic Value Chain Development in North Eastern Region Scheme, (3) Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana, (4) The mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (a. National Horticulture Mission, b. Horticulture Mission for North East and Himalayan states, c. National Bamboo Mission, d. National Horticulture Board, e. Coconut Development Board, d. Central Institute for Horticulture, Nagaland), (5) National Programme for Organic Production, (6) National Project on Organic Farming, and (7) National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture ( Yadav, 2017 ).

Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) is a method of farming where the cost of growing and harvesting plants is zero as it reduces costs through eliminating external inputs and using local resources to rejuvenate soils and restore ecosystem health through diverse, multi-layered cropping systems. It requires only 10% of water and 10% electricity less than chemical and organic farming. The micro-organisms of Cow dung (300–500 crores of beneficial micro-organisms per one gram cow dung) decompose the dried biomass on the soil and convert it into ready-to-use nutrients for plants. Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana since 2015–16 and Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana are the schemes taken by the Government of India under the ZBNF policy ( Sobhana et al. , 2019 ). According to Kumar (2020) , in the union budget 2020–21, Rs 687.5 crore has been allocated for the organic and natural farming sector which was Rs 461.36 crore in the previous year.

Indian Competence Centre for Organic Agriculture cited that the global market for organically grown foods is USD 26 billion which will be increased to the amount of USD 102 billion by 2020 ( Chopra et al. , 2013 ).

The major states involved in organic agriculture in India are Gujarat, Kerala, Karnataka, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh, and Himachal Pradesh ( Chandrashekar, 2010 ).

India ranked 8th with respect to the land of organic agriculture and 88th in the ratio of organic crops to agricultural land as per Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority and report of Research Institute of Organic Agriculture ( Chopra et al. , 2013 ; Willer and Lernoud, 2017 ). But a significant growth in the organic sector in India has been observed ( Willer and Lernoud, 2017 ) in the last decades.

There have been about a threefold increase from 528 171 ha in 2007–08 to 1.2 million ha of cultivable land in 2014–15. As per the study conducted by Associated Chambers of Commerce & Industry in India, the organic food turnover is increasing at about 25% annually and thereby will be expected to reach USD 1.36 billion in 2020 from USD 0.36 billion in 2014 ( Willer and Lernoud, 2017 ).

The consumption and popularity of organic foods are increasing day by day throughout the world. In 2008, more than two-thirds of US consumers purchased organic food, and more than one fourth purchased them weekly. The consumption of organic crops has doubled in the USA since 1997. A consumer prefers organic foods in the concept that organic foods have more nutritional values, have lesser or no additive contaminants, and sustainably grown. The families with younger consumers, in general, prefer organic fruits and vegetables than consumers of any other age group ( Thompson et al. , 1998 ; Loureino et al. , 2001 ; Magnusson et al. , 2003 ). The popularity of organic foods is due to its nutritional and health benefits and positive impact on environmental and socioeconomic status ( Chopra et al. , 2013 ) and by a survey conducted by the UN Environment Programme, organic farming methods give small yields (on average 20% lower) as compared to conventional farming ( Gutierrez et al. , 1999 ). As the yields of organically grown foods are low, the costs of them are higher. The higher prices made a barrier for many consumers to buy organic foods ( Lairon, 2010 ). Organic farming needs far more lands to generate the same amount of organic food produce as conventional farming does, as chemical fertilizers are not used here, which conventionally produces higher yield. Organic agriculture hardly contributes to addressing the issue of global climate change. During the last decades, the consumption of organic foods has been increasing gradually, particularly in western countries ( Meiner-Ploeger, 2005 ).

Organic foods have become one of the rapidly growing food markets with revenue increasing by nearly 20% each year since 1990 ( Winter and Davis, 2006 ). The global organic food market has been reached USD 81.6 billion in 2015 from USD 17.9 billion during the year 2000 ( Figure 6 ) and most of which showed double-digit growth rates ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ).

Worldwide growth in organic food sales ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ).

India is an agriculture-based country with 67% of its population and 55% of manpower depending on farming and related activities. Agriculture fulfils the basic needs of India’s fastest-growing population accounted for 30% of total income. Organic farming has been found to be an indigenous practice of India that practised in countless rural and farming communities over the millennium. The arrival of modern techniques and increased burden of population led to a propensity towards conventional farming that involves the use of synthetic fertilizer, chemical pesticides, application of genetic modification techniques, etc.

Even in developing countries like India, the demand for organically grown produce is more as people are more aware now about the safety and quality of food, and the organic process has a massive influence on soil health, which devoid of chemical pesticides. Organic cultivation has an immense prospect of income generation too ( Bhardwaj and Dhiman, 2019 ). The soil in India is bestowed with various types of naturally available organic nutrient resources that aid in organic farming ( Adolph and Butterworth, 2002 ; Reddy, 2010 ; Deshmukh and Babar, 2015 ).

India is a country with a concrete traditional farming system, ingenious farmers, extensive drylands, and nominal use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Moreover, adequate rainfall in north-east hilly regions of the country where few negligible chemicals are employed for a long period of time, come to fruition as naturally organic lands ( Gour, 2016 ).

Indian traditional farmers possess a deep insight based on their knowledge, extensive observation, perseverance and practices for maintaining soil fertility, and pest management which are found effective in strengthening organic production and subsequent economic growth in India. The progress in organic agriculture is quite commendable. Currently, India has become the largest organic producer in the globe ( Willer and Lernoud, 2017 , 2019 ) and ranked eighth having 1.78 million ha of organic agriculture land in the world in 2017 ( Sharma and Goyal, 2000 ; Adolph and Butterworth, 2002 ; Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ).

Various newer technologies have been invented in the field of organic farming such as integration of mycorrhizal fungi and nano-biostimulants (to increase the agricultural productivity in an environmentally friendly manner), mapping cultivation areas more consciously through sensor technology and spatial geodata, 3D printers (to help the country’s smallholder), production from side streams and waste along with main commodities, promotion and improvement of sustainable agriculture through innovation in drip irrigation, precision agriculture, and agro-ecological practices. Another advancement in the development of organic farming is BeeScanning App, through which beekeepers can fight the Varroa destructor parasite mite and also forms a basis for population modelling and breeding programmes ( Nova-Institut GmbH, 2018 ).

Inhana Rational Farming Technology developed on the principle ‘Element Energy Activation’ is a comprehensive organic method for ensuring ecologically and economically sustainable crop production and it is based on ancient Indian philosophy and modern scientific knowledge.

The technology works towards (1) energization of soil system: reactivation of soil-plant-microflora dynamics by restoration of the population and efficiency of the native soil microflora and (2) energization of plant system: restoration of the two defence mechanisms of the plant kingdom that are nutrient use efficiency and superior plant immunity against pest/disease infection ( Barik and Sarkar, 2017 ).

Organic farming yields more nutritious and safe food. The popularity of organic food is growing dramatically as consumer seeks the organic foods that are thought to be healthier and safer. Thus, organic food perhaps ensures food safety from farm to plate. The organic farming process is more eco-friendly than conventional farming. Organic farming keeps soil healthy and maintains environment integrity thereby, promoting the health of consumers. Moreover, the organic produce market is now the fastest growing market all over the world including India. Organic agriculture promotes the health of consumers of a nation, the ecological health of a nation, and the economic growth of a nation by income generation holistically. India, at present, is the world’s largest organic producers ( Willer and Lernoud, 2019 ) and with this vision, we can conclude that encouraging organic farming in India can build a nutritionally, ecologically, and economically healthy nation in near future.

This review work was funded by the University Grants Commission, Government of India.

None declared.

Adolph , B. , Butterworth , J . ( 2002 ). Soil fertility management in semi-arid India: its role in agricultural systems and the livelihoods of poor people . Natural Resources Institute , UK .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

AFSSA. ( 2003 ). Report on Evaluation of the nutritional and sanitary quality of organic foods (Evaluation nutritionnelle et sanitaire des aliments issus de l’agriculturebiologique, in French), AFSSA, 164 . http://www.afssa.fr . Accessed 3 August 2018 .

Barik , A. , Sarkar , N . ( 2017 , November 8-11). Organic Farming in India: Present Status, Challenges and Technological Break Through . In: 3rd International Conference on Bio-resource and Stress Management, Jaipur, India.

Bhardwaj , M. , Dhiman , M . ( 2019 ). Growth and performance of organic farming in India: what could be the future prospects? Journal of Current Science , 20 : 1 – 8 .

BjØrn , G. , Fruekidle , A. M . ( 2003 ). Cepa onions ( Allium cepa L) grown conventionally . Green Viden , 153 : 1 – 6 .

Bourn , D. , Prescott , J . ( 2002 ). A comparison of the nutritional value, sensory qualities, and food safety of organically and conventionally produced foods . Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition , 42 : 1 – 34 .

Brandt , D.A. , Brand , T.S. , Cruywagen , C.W . ( 2000 ). The use of crude protein content to predict concentrations of lysine and methionine in grain harvested from selected cultivars of wheat, barley and triticale grown in Western Cape region of South Africa . South African Journal of Animal Science , 30 : 22 – 259 .

Brandt , K. , MØlgaord , J.P . ( 2001 ). Organic agriculture: does it enhance or reduce the nutritional value of plant foods? Journal of Science of Food Agriculture , 81 : 924 – 931 .

Butler , G. et al. ( 2008 ). Fatty acid and fat-soluble antioxidant concentrations in milk from high- and low-input conventional and organic systems: seasonal variation . Journal Science of Food and Agriculture , 88 : 1431 – 1441 .

Chandrashekar , H.M . ( 2010 ). Changing Scenario of organic farming in India: an overview . International NGO Journal , 5 : 34 – 39 .

Chopra , A. , Rao , N.C. , Gupta , N. , Vashisth , S . ( 2013 ). Come sunshine or rain; organic foods always on tract: a futuristic perspective . International Journal of Nutrition, Pharmacology Neurological Diseases , 3 : 202 – 205 .

Dangour , A.D. , Allen , E. , Lock , K. , Uauy , R . ( 2010 ). Nutritional composition & health benefits of organic foods-using systematic reviews to question the available evidence . Indian Journal of Medical Research , 131 : 478 – 480 .

Deshmukh , M.S. , Babar , N . ( 2015 ). Present status and prospects of organic farming in India . European Academic Research , 3 : 4271 – 4287 .

Edwards , S . ( 2007 ). The impact of compost use on crop yields in Tigray, Ethiopia . In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Organic Agriculture and Food Security . 2–5 May 2007, FAO , Rome [cited on 2013 March 20], pp. 1 – 42 . http://www.ftp.fao.org/paia/organica/ofs/02-Edwards.pdf .

Fileβbach , A. , Oberholzer , H.R. , Gunst , L. , Mäder , P . ( 2007 ). Soil organic matter and biological soil quality indicators after 21 years of organic and conventional farming . Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment , 118 : 273 – 284 .

Fliessbach , A. , Mäder , P . ( 2000 ). Microbial biomass and size—density fractions differ between soils of organic and conventional agricultural system . Soil Biology and Biochemistry , 32 : 757 – 768 .

Food Marketing Institute (FMI) . ( 2008 ). Natural and organic foods . http://www.fmi.org/docs/media-backgrounder/natural_organicfoods.pdf?sfvrsn=2 . Accessed 10 March 2019 .

Gour , M . ( 2016 ). Organic farming in India: status, issues and prospects . SOPAAN-II , 1 : 26 – 36 .

Gutierrez , F. , Arnaud , T. , Albi , M.A . ( 1999 ). Influence of ecologic cultivation on virgin olive oil quality . Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society , 76 : 617 – 621 .

Halberg , N . ( 2008 ). Energy use and green house gas emission in organic agriculture. In: Proceedings of International Conference Organic Agriculture and Climate Change . 17–18 April 2008, ENITA of Clermont , France , pp. 1 – 6 .

Hansen , B. , Alroe , H.J. , Kristensen , E.S. ( 2001 ). Approaches to assess the environmental impact of organic farming with particular regard to Denmark . Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment , 83 : 11 – 26 .

Hansson , I. , Hamilton , C. , Ekman , T. , Forslund , K . ( 2000 ). Carcass quality in certified organic production compared with conventional livestock production . Journal of Veterinary Medicine. B, Infectious Diseases and Veterinary Public Health , 47 : 111 – 120 .

International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) . ( 1998 ). The IFOAM basic standards for organic production and processing . General Assembly , Argentina, November, IFOAM, Germany . Organic Food Production Act of 1990 (U.S.C) s. 2103.

Kumar , V. ( 2020 , February 03). Union Budget 2020– 21 : Big talk on natural farming but no support [Web log post] . https://www.downtoearth.org.in/blog/agriculture/union-budget-2020-21-big-talk-on-natural-farming-but-no-support-69131 . on 28.04.2020

Lairon , D. ( 2010 ). Nutritional quality and safety of organic food. A review . Agronomy for Sustainable Development , 30 : 33 – 41 .

Levite , D. , Adrian , M. , Tamm , L. ( 2000 ). Preliminary results of resveratrol in wine of organic and conventional vineyards, In: Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Organic Viticulture , 25–26 August 2000, Basel, Switzerland , pp. 256 – 257 .

Lobley , M. , Reed , M. , Butler , A. , Courtney , P. , Warren , M . ( 2005 ). Impact of Organic Farming on the Rural Economy in England . Exeter: Centre for Rural Research, Laffrowda House, University of Exeter , Exeter, UK .

Loureino , L.L. , McCluskey , J.J. , Mittelhammer , R.C . ( 2001 ). Preferences for organic, eco-labeled, or regular apples . American Journal of Agricultural Economics , 26 : 404 – 416 .

Lund , P . ( 1991 ). Characterization of alternatively produced milk . Milchwissenschaft—Milk Science International , 46 : 166 – 169 .

Lung , A.J. , Lin , C.M. , Kim , J.M . ( 2001 ). Destruction of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella enteritidis in cow manure composting . Journal of Food Protection , 64 : 1309 – 1314 .

Magnusson , M. K. , Arvola , A. , Hursti , U. K. , Aberg , L. , Sjödén , P. O . ( 2003 ). Choice of organic foods is related to perceived consequences for human health and to environmentally friendly behaviour . Appetite , 40 : 109 – 117 .

Meiner-Ploeger , K . ( 2005 ). Organic farming food quality and human health. In: NJF Seminar , 15 June 2005, Alnarp, Sweden .

Mukherjee , A. , Kapoor , A. , Dutta , S . ( 2018 ). Organic food business in India: a survey of companies . Research in Economics and Management , 3 : 72 . doi: 10.22158/rem.v3n2P72 .

Nourthbourne , C.J. , 5th Lord. ( 2003 ). Look to the Land , 2nd Rev Spec edn. Sophia Perennis , Hillsdale, NY ; First Ed. 1940. J.M. Dent & Sons.

Nova-Institut GmbH . ( 2018 , July 2). High-tech strategies for small farmers and organic farming [press release] . http://news.bio-based.eu/high-tech-strategies-for-small-farmers-and-organic-farming/ . Accessed 28 April 2020 .

Nürnberg , K. et al. ( 2002 ). N-3 fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acids of longissimus muscle in beef cattle . European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology , 104 : 463 – 471 .

Organic Foods Production Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101–624, §§ 2101- 2123, 104 Stat. 3935 (codified at 7 U.S.C.6501–6522).

Oquist , K. A. , Strock , J. S. , Mulla , D. J . ( 2007 ). Influence of alternative and conventional farming practices on subsurface drainage and water quality . Journal of Environmental Quality , 36 : 1194 – 1204 .

Padiya , J. , Vala , N . ( 2012 ). Profiling of organic food buyers in Ahmadabad city: an empirical study . Pacific Business Review International , 5 : 19 – 26 .

Pandey , J. , Singh , A . ( 2012 ): Opportunities and constraints in organic farming: an Indian perspective . Journal of Scientific Research , 56 : 47 – 72 , ISSN: 0447-9483.

Pastushenko , V. , Matthes , H.D. , Hein , T. , Holzer , Z . ( 2000 ). Impact of cattle grazing on meat fatty acid composition in relation to human nutrition. In: Proceedings 13th IFOAM Scientific Conference . pp. 293 – 296 .

Pimentel , D. , Hepperly , P. , Hanson , J. , Douds , D. , Seidel , R . ( 2005 ). Environmental, energetic and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems . Bioscience , 55 : 573 – 582 .

Reddy S.B . ( 2010 ). Organic farming: status, issues and prospects—a review . Agricultural Economics Research Review , 23 : 343 – 358 .

Rembialkowska , E . ( 2000 ). Wholesomeness and Sensory Quality of Potatoes and Selected Vegetables from the organic Farms . Fundacja Rozwoj SGGW , Warszawa .

Rembialkowska , E . ( 2007 ). Quality of plant products from organic agriculture . Journal Science of Food and Agriculture , 87 : 2757 – 2762 .

Rossi , F. , Godani , F. , Bertuzzi , T. , Trevisan , M. , Ferrari , F. , Gatti , S . ( 2008 ). Health-promoting substances and heavy metal content in tomatoes grown with different farming techniques . European Journal of Nutrition , 47 : 266 – 272 .

Sharma A. K , Goyal R. K. ( 2000 ). Addition in tradition on agroforestry in arid zone . LEISA-INDIA , 2 : 19 – 20 .

Shepherd , R. , Magnusson , M. , Sjödén , P. O . ( 2005 ). Determinants of consumer behavior related to organic foods . Ambio , 34 : 352 – 359 .

Shreck , A. , Getz , C. , Feenstra , G. ( 2006 ). Social sustainability, farm labor, and organic agriculture: findings from an exploratory analysis . Agriculture and Human Values , 23 : 439 – 449 .

Sobhana , E. , Chitraputhira Pillai , S. , Swaminathan , V. , Pandian , K. , Sankarapandian , S . ( 2019 ). Zero Budget Natural Farming. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.17084.46727.

Soumya , K. M . ( 2015 ). Organic farming: an effective way to promote sustainable agriculture development in India . IOSR Journal Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) , 20 : 31 – 36 , e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org .

Stolze , M. , Piorr , A. , Haring , A.M. , Dabbert , S. ( 2000 ). Environmental impacts of organic farming in Europe . Organic Farming in Europe: Economics and Policy . vol. 6 . University of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany . Retrieved on 15 May 2011. http://orgprints.org/8400/1/Organic_Farming_in_Europe_Volume06_The_Environmental_Impacts_of_Organic_Farming_in_Europe.pdf .

Thompson , G.D. , Kidwell , J . ( 1998 ). Explaining the choice of organic procedure: cosmetic defects, prices, and consumer preferences . American Journal of Agricultural Economics , 80 : 277 – 287 .

Van Renterghem , B. , Huysman , F. , Rygole , R. , Verstraete , W . ( 1991 ). Detection and prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in the agricultural ecosystem . Journal of Applied Bacteriology , 71 : 211 – 217 .

Warnick , L. D. , Crofton , L. M. , Pelzer , K. D. , Hawkins , M. J . ( 2001 ). Risk factors for clinical salmonellosis in Virginia, USA cattle herd . Preventive Veterinary Medicine , 49 : 259 – 275 .

Willer , H. , Lernoud , J ., eds. ( 2017 ). The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends . FiBL & IFOAM—Organics International , Bonn.

Willer , H . Lernoud J , eds. ( 2019 ). The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends . Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Frick and IFOAM—Organics International , Bonn . https://www.organicworld.net/yearbook/yearbook-2019.html .

Winter , C.K. , Davis , S.F . ( 2006 ). Organic food . Journal of Food Science , 71 : 117 – 124 .

Woëse , K. , Lange , D. , Boess , C. , Bögl , K.W . ( 1997 ). A comparison of organically and conventionally grown foods—results of a review of the relevant literature . Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture , 74 : 281 – 293 .

Worthington , V . ( 2001 ). Nutritional quality of organic versus conventional fruits, vegetables, and grains . Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine , 7 : 161 – 173 .

Yadav , M . ( 2017 ). Towards a healthier nation: organic farming and government policies in India . International Journal of Advance Research and Development , 2 : 153 – 159 .

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| June 2020 | 203 |

| July 2020 | 463 |

| August 2020 | 2,622 |

| September 2020 | 3,959 |

| October 2020 | 4,612 |

| November 2020 | 4,601 |

| December 2020 | 5,539 |

| January 2021 | 4,939 |

| February 2021 | 5,162 |

| March 2021 | 6,491 |

| April 2021 | 4,831 |

| May 2021 | 5,089 |

| June 2021 | 5,550 |

| July 2021 | 6,397 |

| August 2021 | 6,329 |

| September 2021 | 7,582 |

| October 2021 | 7,378 |

| November 2021 | 8,133 |

| December 2021 | 7,775 |

| January 2022 | 6,877 |

| February 2022 | 6,662 |

| March 2022 | 6,833 |

| April 2022 | 3,874 |

| May 2022 | 4,418 |

| June 2022 | 3,829 |

| July 2022 | 3,175 |

| August 2022 | 2,988 |

| September 2022 | 3,911 |

| October 2022 | 3,639 |

| November 2022 | 4,990 |

| December 2022 | 3,555 |

| January 2023 | 3,556 |

| February 2023 | 2,111 |

| March 2023 | 2,106 |

| April 2023 | 1,945 |

| May 2023 | 1,598 |

| June 2023 | 1,729 |

| July 2023 | 1,703 |

| August 2023 | 1,627 |

| September 2023 | 1,843 |

| October 2023 | 2,691 |

| November 2023 | 2,368 |

| December 2023 | 1,280 |

| January 2024 | 1,156 |

| February 2024 | 1,233 |

| March 2024 | 1,341 |

| April 2024 | 1,253 |

| May 2024 | 1,397 |

| June 2024 | 1,121 |

| July 2024 | 958 |

| August 2024 | 672 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2399-1402

- Print ISSN 2399-1399

- Copyright © 2024 Zhejiang University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sustainable food security in India—Domestic production and macronutrient availability

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Contributed equally to this work with: David Reay, Peter Higgins

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- Hannah Ritchie,

- David Reay,

- Peter Higgins

- Published: March 23, 2018

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193766

- Reader Comments

India has been perceived as a development enigma: Recent rates of economic growth have not been matched by similar rates in health and nutritional improvements. To meet the second Sustainable Development Goal (SDG2) of achieving zero hunger by 2030, India faces a substantial challenge in meeting basic nutritional needs in addition to addressing population, environmental and dietary pressures. Here we have mapped—for the first time—the Indian food system from crop production to household-level availability across three key macronutrients categories of ‘calories’, ‘digestible protein’ and ‘fat’. To better understand the potential of reduced food chain losses and improved crop yields to close future food deficits, scenario analysis was conducted to 2030 and 2050. Under India’s current self-sufficiency model, our analysis indicates severe shortfalls in availability of all macronutrients across a large proportion (>60%) of the Indian population. The extent of projected shortfalls continues to grow such that, even in ambitious waste reduction and yield scenarios, enhanced domestic production alone will be inadequate in closing the nutrition supply gap. We suggest that to meet SDG2 India will need to take a combined approach of optimising domestic production and increasing its participation in global trade.

Citation: Ritchie H, Reay D, Higgins P (2018) Sustainable food security in India—Domestic production and macronutrient availability. PLoS ONE 13(3): e0193766. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193766

Editor: David A. Lightfoot, College of Agricultural Sciences, UNITED STATES

Received: September 13, 2017; Accepted: February 17, 2018; Published: March 23, 2018

Copyright: © 2018 Ritchie et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files, or can be accessed at the UN FAO databases through the following URL: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home .

Funding: The authors received funding from the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) as part of its E3 DTP programme.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations (UN) committed to achieving zero hunger by 2030 as the second of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). An important element of this goal is to end all forms of malnutrition, including agreed targets on childhood stunting and wasting. This represents an important progression beyond the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), where food security was defined and measured solely on the basis of basic energy requirements (caloric intake), and prevalence of underweight children [ 1 ]. This new commitment has significant implications for the focus of research and policy decisions; it requires a broadening of scope beyond the traditional analysis of energy intake, and inclusion of all nutrients necessary for adequate nourishment.

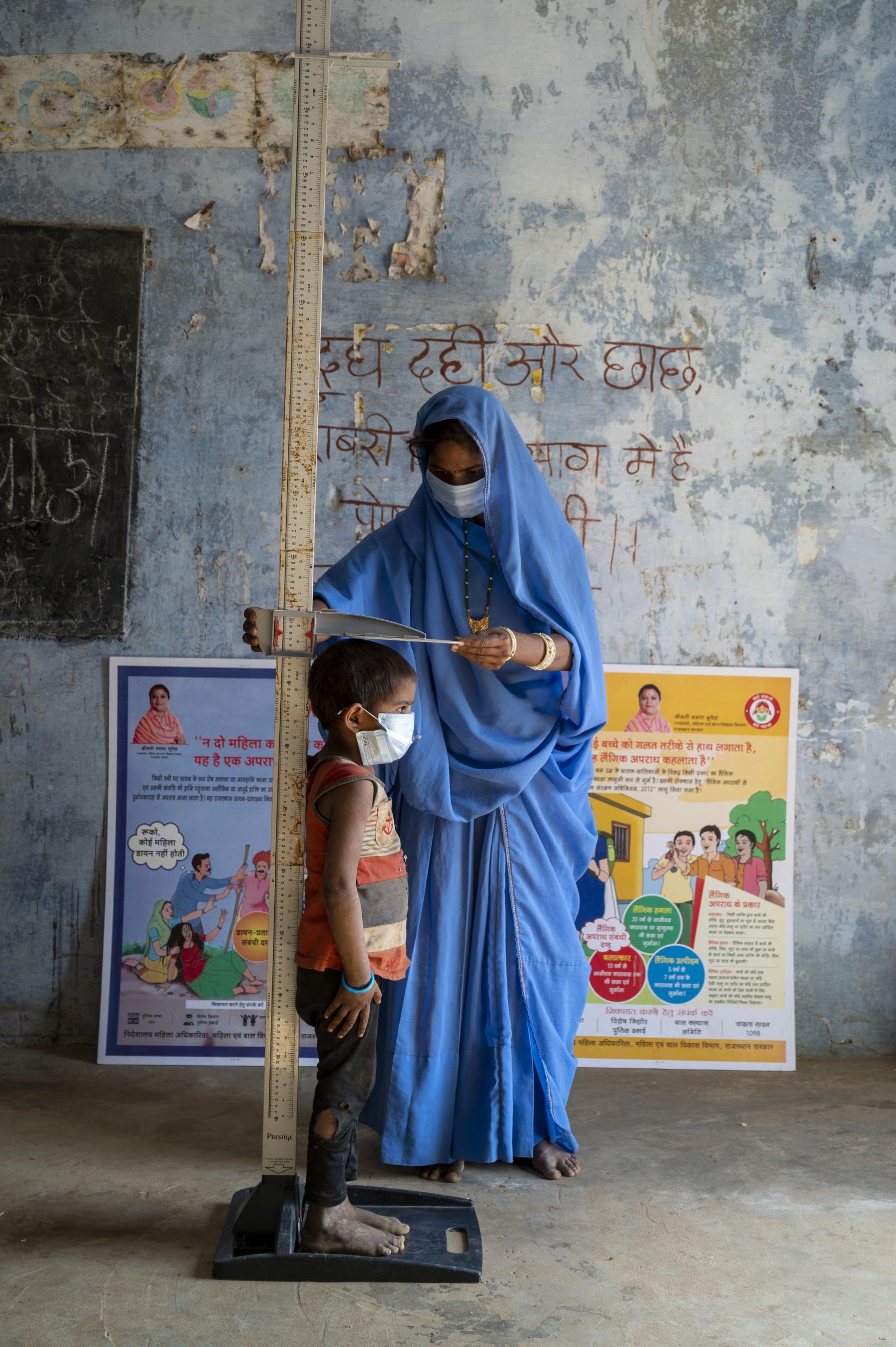

India offers a potentially unique example in the development of models and mechanisms by which nutritional needs can be addressed sustainably. In 2016, India ranked 97 out of 118 on the Global Hunger Index (GHI)—this rates nations’ nutritional status based on indicators of undernourishment, child wasting, stunting and mortality [ 2 ]. Despite ranking above some of the world’s poorest nations, India’s reduction in malnourishment has been slow relative to its recent strong economic growth and puts it behind poorer neighbouring countries [ 3 ]; India has fallen from 80 th to 97 th since 2000.

India’s nutritional problems are extensive. In 2016, 38.7% of children under five were defined as ‘stunted’ (of below average height) [ 2 ], a strong indicator of chronic malnourishment in children and pregnant women, and a largely irreversible condition leading to reduced physical and mental development [ 4 ]. Malnourishment within the adult population is also severe, with approximately 15% of the total population defined as malnourished. The issue of malnutrition in India is complex, and determined by a combination of dietary intake and diversity, disease burden (intensified by poor sanitation and hygiene standards), and female empowerment and education [ 5 ]. Improvements in dietary intake alone will therefore by insufficient to eliminate malnutrition, however it forms an integral component alongside progress in other social and health indicators—particularly sanitation. Quantification of India’s micronutrient and amino acid profiles, and recommendations for addressing these deficiencies have been completed as a follow-up paper (Ritchie et al. in submission) to provide a more holistic overview of its nutritional position.

India’s nutritional and health challenges are likely to be compounded in the coming decades through population growth and resource pressures. Its current population of 1.26 billion is projected to increase to 1.6 billion by 2050, overtaking China as the world’s most populous nation [ 6 ]. India has also been highlighted as one of the most risk-prone nations for climate change impacts, water scarcity, and declining soil fertility through land degradation [ 7 ].

A number of studies have focused specifically on Indian food intake and malnutrition issues from survey assessments at the household level [ 8 ]. The emphasis within India’s agricultural policy and assessment of its success has traditionally been on energy (caloric) intake [ 9 ]. Since the Green Revolution in the 1970s, agricultural policies have been oriented towards a rapid increase in the production of high-yielding cereal crops with a focus to meet the basic calorific needs of a growing population. India has attempted to reach self-sufficiency predominantly through political and investment orientation towards wheat and rice varieties [ 10 ]. While production of staple crops has increased significantly, India’s agricultural policy focus on cereal production raises a key challenge in simultaneously meeting nutritional needs in caloric, high-quality protein and fat intakes. Few studies have addressed the system-wide balance between supply and demand of the three key macronutrients—calories, protein and fat; nor have they assessed the importance of protein quality through digestibility and amino acid scoring. This assessment is particularly significant for India as a result of its extensive and complex malnutrition issues. Whether India is capable of meeting these macronutrient needs in the future through domestic production improvements alone is of prime importance for study, as a result of its growing population and policy orientation towards self-sufficiency.

Improving the availability and access to food at the consumer level requires an understanding of how food is created and lost through its various pathways across the full agricultural supply chain. Here, for the first time, we have attempted to capture this high-level outlook from crop harvesting to residual food availability across the three macronutrient categories.

Mapping the current Indian food system

The Indian food system was mapped from crop production through to per capita food supply using FAO Food Balance Sheets (FBS) from its FAOstats databases [ 11 ]. FBS provide quantitative data (by mass) on production of food items and primary commodities, and their utilisations throughout the food supply chain. Such data are available at national, regional and global levels. Food Balance Sheet data for 2011 have been used, these being from the latest full data-set available. Some aspects of FBS data are available for the years 2012 and 2013, however such data are not complete across all commodities and value chain stages at the time of writing.

Food Balance Sheets provide mass quantities across the following stages of the supply chain: crop production, exports, imports, stock variation, re-sown produce, animal feed, other non-food uses, and food supplied (as kg per capita per year). Data on all key food items and commodities across all food groups (cereals; roots and tubers; oilseeds and pulses; fruit and vegetables; fish and seafood; and meat and dairy) are included within these balances.

While there are uncertainties in FAO data (see Supplementary Information for further discussion on FAO data limitations), FBS provide the only complete dataset available for full commodity chain analysis. Therefore, while not perfect, they provide an invaluable high-level outlook of relative contribution of each stage in the food production and distribution system. As shown in this study (see Results section below), a top-down model using FAO FBS has a discrepancy of <10% with national nutrition survey results at the household level.

FBS do not provide food loss and waste figures by stage in the supply chain. To maintain consistency with FAO literature, food loss figures have therefore been calculated based on South Asian regional percentages within FAO publications [ 12 ]. These percentage figures break food losses down across seven commodity groups and five supply chain stages (agricultural production, postharvest handling and storage, processing and packaging, distribution and consumption). The applied percentage values by commodity type and supply chain stage are provided in S1 Table .

In order to calculate the total nutritional value at each supply chain stage, commodity mass quantities were multiplied by FAO macronutrient nutritional factors [ 11 ]. In this analysis, energy content (kilocalories), protein, and fat supply were analysed. Protein quality is a key concern for India in particular as a result of its largely grain-based diet, with grains tending to have poorer digestibility and amino acid (AA) profiles than animal-based products and plant-based legume alternatives [ 13 ]. To best quantify limitations in protein quality in the Indian diet, protein intakes have therefore been corrected for digestibility using FAO digestibility values [ 14 ].

For consistency, and to provide a better understanding of the food system down to the individual supply level, all metrics have been normalised to average per person per day (pppd) availability using UN population figures and prospects data [ 6 ]. Whilst this provides an average per capita availability value, it does not account for variability in actual macronutrient supply within the population. To help adjust for this, we have also estimated the assumed distribution of supply of each macronutrient using the FAO’s preferred log-normal distribution and India-specific coefficient variation (CV) factor of 0.26 [ 15 ]. Whilst we recognise that food requirements vary between demographics based on age, gender and activity levels, the normalisation of food units to average per capita supply levels is essential in providing relatable measures of food losses within the system, and its measure relative to demographically-weighted average nutritional requirements (as described below) is appropriate in providing an estimation of the risk of malnourishment.

Estimated macronutrient supply has then been compared to recommended intake values. The FAO defines the “Average Daily Energy Requirement” (ADER)—for India’s demographic specifically—as 2269kcal pppd; ADER is defined as the average caloric intake necessary to maintain a healthy weight based on the demographics, occupation, and activity levels of any given population [ 16 ]. Protein requirements can vary between similar individuals; recommended daily amounts (RDA) are therefore typically given as two standard deviations (SD) above the average requirement to provide a safety margin, which some individuals would be at risk of falling below. The World Health Organization (WHO) define a ‘safe’ (recommended) intake in adults of 0.83 grams per kilogram per day (g/kg/d) of body mass for proteins with a digestibility score of 1.0 [ 17 ]. The average vegetarian Indian diet contains lower intakes of animal-based complete proteins; the Indian Institute of Nutrition therefore recommends a higher intake of 1 g/kg/d of total protein for Indians to ensure requirements of high-quality protein are met [ 18 ]. This is equivalent to 55 and 60 grams of protein per day in average adult females and males, respectively based on mean body weight [ 19 ]. Since our analysis attempts to correct for protein digestibility, WHO’s lower safe intake of 0.83g/kg/d would reduce to an equivalent of 50 grams of high-quality protein per day for an average 60 kilogram individual. Consequently in this study we have adopted this RDA value of 50 gpppd.

Dietary fat intake plays a key dietary role in the absorption of essential micronutrients. Several vital vitamins, including vitamin A, D, E and K are fat-soluble—insufficient intake can therefore result in poor micronutrient absorption and utilisation [ 20 ]. Inadequate fat intake can therefore exacerbate the widespread ‘hidden hunger’ (micronutrient deficiency) challenge in India [ 21 ] through poor nutrient absorption. However, daily requirements for fatty acids are less straightforward to determine, relative to energy or protein—there is no widely-agreed figure for total fat requirements for adequate nutrition [ 22 ]. The resolution of food balance sheet data does not allow us to adequately quantity the availability to the level of specific fatty acids. As a result, although we have mapped pathways of total fat availability through the food system in a similar manner to energy and protein, we have not here attempted to quantity the prevalence of potential insufficiency at the household level.

Mapping potential near-term and long-term scenarios

Our initial analysis identified two mechanisms potentially crucial in increasing food availability at the household level: reduction of harvesting, postharvest and distribution losses; and improvements in crop yields. Medium-term (through to 2030) and long-term (2050) scenarios have therefore been mapped based on use of these mechanisms. It should be noted that these scenarios are focused on domestic supply-side measures to enhance food availability as opposed to demand drivers related to consumer preferences. A summary of assumptions used in each scenario in this analysis is provided in S2 Table .

A 2030 baseline scenario (assuming yields stagnate and population growth continues in line with UN projections) and three alternative scenarios to 2030 were analysed:

Scenario 1 (halving food supply chain losses): it was assumed that a significant shift in post-harvest management practices, appropriate refrigeration, and efficient distribution allowed for a halving of food loss percentages at the production, postharvest, processing and distribution stages of the supply chain. This would make its relative losses more in line with those of more developed nations [ 12 ]. In this scenario consumption (household) waste was assumed to remain constant.

Scenario 2 (achieving 50% of attainable yield (AY) across all key crops): the halving of food chain losses in scenario 1 was assumed. In addition, it was assumed that all key crops managed to achieve 50% AY through better agricultural management, irrigation and fertiliser practices. ‘Attainable yield’ is defined as the yield achieved with best management practices including pest, nutrient (i.e. nutrients are not limiting) and water management.

Scenario 3 (achieving 75% AY across all key crops): assumptions as in scenario 2 except an attainment of 75%, rather than 50% AY, has been assumed through crop yield improvements.

Long-term (through to 2050) scenarios were as follows:

Scenario 1 (halving food supply chain losses): the same assumption of halving food loss percentages at the production, postharvest, processing and distribution stages of the supply chain was applied in this scenario. This will require a significant shift in post-harvest management practices, appropriate refrigeration, and efficient distribution, hence 50% reduction represents a magnitude which is more likely to be achieved in this long-term scenario than in the near-term.

Scenario 2 (achieving 75% AY across all key crops): the same assumption of a closure of the yield gap to 75% AY across all crop types, as in the near-term scenario 3, was applied.

Scenario 3 (achieving 90% AY across all key crops): it was assumed that all crop types managed to achieve closure of the yield gap to 90% AY.

To correct for 2030 and 2050 population estimates, all metrics were re-normalised to ‘per person per day’ (pppd) based on a projected Indian population estimate from UN prospects medium fertility scenarios [ 6 ].

To best demonstrate the food production potential of current agricultural support mechanisms, such as governmental policy and subsidy (which largely determine crop choices), the relative allocation of crop production was assumed constant. It was also assumed that production increases were achieved through agricultural intensification alone; this assumption was based on FAOstats data which has shown no increase in agricultural land area over the past decade, indicating a stagnation in agricultural extensification ( http://faostat.fao.org/beta/en/#home ).

Crop yield increases were derived based on closure of current farm yields (FY) to reported attainable yields (AY). FY is defined as the average on-farm yield achieved by farmers within a given region, and AY is defined as the economically attainable (optimal) yield which could be achieved if best practices in water and pest management, fertiliser application and technologies are utilised in non-nutrient limiting conditions). Estimates of crop yield improvements were based on given percentage realisations of maximum attainable yields (AY) attained from published Indian crop-specific figures [ 23 ]. These data are available across all key crop types. Baseline and AY values are provided in S3 Table .

Significant improvements in yield would predominantly be achieved through improved nutrient and water management. In the present study, scenarios were mapped based on achievement of 50% and 75% AY in the near-term. Fifty percent AY should be technically feasible by 2030: many crops have already reached these values, and those which have yet to do so, typically fall short by 3–5% (see S3 Table for baseline, and AY values). Attainment of 75% AY would be highly ambitious in the near-term, representing an increase of >20% in yield. However, 75% AY and higher may be feasible in the long-term if significant investment in agricultural management and best practice were to be realised in this sector.

Our scenarios to 2050 are therefore modelled on the basis of closure of the yield gap to 75% and 90% AY. To assess whether these estimates were realistic, necessary growth rates were cross-checked based on historical yield growth rates in India. Discussion on this comparison and the suitability of attainable yield valuables utilised in this study are available in the Supplementary Discussion.

Climate change impacts on crop yields remain highly uncertain; the importance of temperature thresholds in overall crop tolerance makes yield impacts highly dependent on GHG emission scenarios. This makes it challenging to accurately quantify 2050 climate impacts. As such, we applied average percentage changes in yields of Indian staple crops based on literature review [ 24 ] of field-based observations and climate model results. The studies utilised presented results for a doubling of atmospheric CO 2 from pre-industrial levels. This approximates to a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario for 2050 [ 25 ]. The yield-climate factors applied in this analysis are provided in S4 Table .

It is projected that, through economic growth and shifts in dietary preferences, meat and dairy demand in India will continue to increase through to 2050. It has been assumed that per capita demand in 2050 is in line with FAO projections; this represents an increase in meat from 3.1kg per person per year (2007) to 18.3kg in 2050, and an increase in milk and dairy from 67kg to 110kg per person per year [ 26 ]. We here assume that this increase in livestock production has been met through increased production of crop-based animal feed rather than pasture. The change in macronutrient demand for animal feed was calculated based on energy and protein conversion efficiency factors for dominant livestock types (beef cattle, dairy cattle, ruminants and poultry) [ 27 ].

Our analysis assumes that the per person allocation of crops for resowing and non-food uses, and the relative allocation of land for respective crop selection, is the same as in the initial baseline (2011) analysis.

Current food system pathways

The pathways of macronutrients from crop production to residual food availability are shown for calories, digestible protein and fat in Fig 1A–1C . Across all macronutrients, the relative magnitude of exports, imports and stock variation is small, and approximately balance as inputs and outputs to the food system. This result is in line with India’s orientation towards meeting food demand through self-sufficiency agricultural policies [ 28 , 29 ]. This study’s scenarios are therefore designed to assess whether this same emphasis on self-sufficiency in food supply through to 2050 could be achieved through waste reduction and crop yield improvements alone.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Food pathways in (a) calories; (b) digestible protein; and (c) fat from crop production to residual food availability, normalised to average per capita levels assuming equal distribution. Red bars (negative numbers) indicate food system losses; blue bars indicate system inputs; green bars indicate meat and dairy production; and grey bars indicate macronutrient availability at intermediate stages of the chain.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193766.g001

In 2011, India produced 3159kcal, 72g of digestible protein, and 86g of fat per person per day (pppd) ( Fig 1A–1C ). Across the system, this resulted in average food availability of 2039kcal, 48g digestible protein, and 49g fat pppd; this represents a loss across the food supply system of 35%, 33%, and 43% in calories, digestible protein, and fat respectively.

Our top-down supply model has been cross-checked against India’s National Sample Survey (NSS) data—this reports nutritional intakes bi-annually measured through national household surveys. In its 68 th Round (2011–12) report, the NSS reported average daily intakes of 2206kcal and 2233kcal in urban and rural areas, respectively; 60g of protein in both demographics; and 58g (urban) and 46g (rural) of fat [ 30 ]. Our top-down analysis therefore suggests slightly lower caloric availability than NSS intake figures (but with a discrepancy of <10%); and strong correlation regarding fat intake. Since NSS data reports total protein and take no account of quality or digestibility, our results of digestible protein are not directly comparable. However, with digestibility scores removed, our analysis suggests a total average protein availability of 57g pppd—within 5% of NSS intake results.

Despite the acknowledged uncertainties in FAO FBS datasets (see Supplementary discussion), the strong correlation (within 5–10%) between our top-down supply model and reported household intakes (bottom-up approach) gives confidence in the use of FBS data for high-level food chain analyses such as attempted here.

The largest sources of loss identified in the Indian food system for calories and protein lie in the agricultural production and post-harvest waste stages of the chain, with lower but significant losses in processing and distribution. Consumption-phase losses are comparatively small. Higher losses of fat occur predominantly due to the allocation of oilseed crops for non-food uses; this is in contrast to digestible protein where losses to competing non-food uses are negligible.

In contrast to the average global food supply system, the conversion of crop-based animal feed to meat and dairy produce in India appears comparatively efficient, with an input-output ratio close to one for calories and protein, and an apparent small production of fats [ 31 ]. It is one of the few agricultural systems in the world where the majority of livestock feed demand is met through crop residues, byproducts and pasture lands—its lactovegetarian preferences tend to favour pasture-fed dairy cattle over grain-fed livestock such as poultry (ibid).

Average per capita supply across all macronutrients falls below average per capita minimum requirements. The magnitude of this issue in India emerges via the population-intake distributions. With extension of average macronutrient availability to availability across the population distribution (using a log-normal distribution with CV of 0.26), 66% (826 million) and 56% (703 million) of the population are at risk of falling below recommended energy and protein requirements, respectively.

Potential future pathways

Scenario results for 2030..

Results from scenario analyses for potential food waste reduction and crop yield improvements are summarised in Table 1 . Note that we have assumed no change in income/dietary inequalities, hence the CV in distribution has remained constant.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193766.t001

Under all scenarios, waste or yield improvements fail to keep pace with population growth through to 2030; average per capita caloric, digestible protein and fat availability all fall below the 2011 baseline. Under current levels of dietary inequality, distribution of availability highlights even greater potential malnourishment. The majority (>75%) of the population are at risk of falling below requirements in energy and protein availability in all scenarios. This represents severe malnutrition across India in 2030, even in the case of significant and ambitious yield and efficiency improvements.

Under these scenarios, India would fall far short of reaching the SDG2 target of Zero Hunger by 2030.

Scenario results for 2050.

India’s anticipated population growth, in addition to potential impacts of climate change on crop yields, could have severe implications on household macronutrient supply by 2050. Our 2050 baseline scenario demonstrates these potential impacts, assuming gains in crop yields were to stagnate at current levels. The full supply chain pathways are shown in Fig 2A–2C . Even at the top level of the supply chain (crop production phase) mean provision per person would fall below average requirements in all macronutrients (2198kcal, 49g protein, and 60g fat per person). Although reducing food system losses plays an important role in improving availability at the household level, this result highlights the necessity of also achieving substantial crop yield improvements at the top of the supply chain.

Food pathways in (a) calories; (b) digestible protein; and (c) fat from crop production to residual food availability, normalised to average per capita levels assuming equal distribution under 2050 baseline conditions. Red bars (negative numbers) indicate food system losses; blue bars indicate system inputs; green bars indicate meat and dairy production; and grey bars indicate macronutrient availability at intermediate stages of the chain.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193766.g002

How these variables impact on availability at the household level in our 2050 baseline, and three scenarios is detailed in Table 2 , with baseline distributions provided in Supplementary Fig 1A–1C . As shown, even in the case of scenario 1 (halving of supply chain loss and waste), and scenario 2 (increase to 75% of AY), in 2050 greater than 80% of the population would potentially fall below average requirements in energy and protein. Only in the case of significant yield increases to 90% AY (scenario 3) would projected levels of malnourishment approach current levels. This would still leave 62% and 56% of the population at risk of falling below recommended caloric and protein requirements, respectively.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0193766.t002

Our analysis utilised a framework for evaluation of the whole food system (from crop production through to residual food availability) by normalising to consistent and relatively simplistic metrics (per person per day). This holistic approach is critical for identifying levers within the food system which can be targeted for improvements in food security and efficiency of supply. The basic framework is replicable and could therefore be adapted for analysis of any dietary component (for example, micronutrients or amino acids and at a range of scales (global, regional, or national). This allows for similar analyses to be carried out for any nation, potentially allowing for improved understanding of hotspots in the food system and opportunities for improved efficiency. As such, it could then allow national food strategies to focus on components which are likely to maximise improvements.

Overall, our analyses indicate weaknesses in India’s current reliance on domestic food production. Further calculation, based on FAO FBS, make this explicit: in 2011 India’s population was 17.8% of the global total, yet produced only 10.8%, 9%, and 11.8% of the world’s total calories, digestible protein and fat respectively. Based on calculations using FAOstats global crop production data and nutritional composition factors, in 2011 world crop production totalled 1.34x10 16 kcal; 3.62x10 14 g digestible protein; and 3.33x10 14 g fat. 2011 Indian production amounted to 1.44x10 15 kcal; 3.27x10 13 g digestible protein; and 3.93x10 13 g fat. Even in a highly efficient food system, self-sufficiency is impossible to achieve based on such production levels and the need to provide sufficient nourishment for all. Likewise, even if Indian population figures were to plateau, it is unlikely that domestic production alone would be sufficient to close the current food gap.

Current malnutrition levels—defined here as insufficient macronutrient availability—in India are already high. Sufficient nutrition requires adequate availability and intake of all three macronutrients. Impacts of insufficient protein and energy intake can often be difficult to decouple, and are often termed protein-energy malnourishment (PEM)—PEM has a number of negative consequences including reduced physical and mental development [ 32 ]; increased susceptibility to disease and infection; poorer recovery and increased mortality from disease; and lower productivity [ 33 ]. Our results indicate that India’s self-sufficiency model—a reliance on domestic crop yield increases and waste reduction strategies—will be insufficient to meet requirements across all three macronutrients. Levels of undersupply and consequent malnutrition would show a significant increase in both 2030 and 2050 scenarios.

This has important implications for forward planning to effectively address malnutrition. Policy incentives in Indian agriculture since the Green Revolution have predominantly been focused on achieving caloric food security through increased production of cereals (wheat and rice) [ 9 ]. This has resulted in a heavily carbohydrate-based diet (> 65–70% total energy intake [ 34 ]) which may be significantly lacking in adequate diversity for provision of other important nutrients [ 35 ]. Widespread lactovegetarian preferences have further reduced the scope for dietary diversity [ 36 ].

If trying to address caloric inadequacy alone, efforts to increase output of energy-dense crops (i.e. cereals, roots and tubers) may seem appropriate, and has largely been India’s focus to date [ 8 ]. Our analysis, however, strongly suggests the need to shift dietary composition away from reliance on carbohydrates towards a more diversified intake of protein and fats (with diversification also contributing to a reduction in micronutrient deficiency) [ 37 ]. Forward planning therefore needs to simultaneously address caloric inadequacy and malnourishment through balanced, increased supply and intake of high-quality proteins and fats.