Case Presentation: A 23-Year-Old With Bipolar Disorder

Gus Alva, MD, DFAPA, presents the case of a 23-year-old female diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder.

EP: 1 . Case Presentation: A 23-Year-Old With Bipolar Disorder

Ep: 2 . clinical impressions from the patient case, ep: 3 . clinical insights regarding the management of bipolar disorder.

Gus Alva, MD, DFAPA: Psychiatric Times presents this roundtable on the management of bipolar disorder, a phenomenal dialogue allowing clinicals a perspective regarding current trends and where we may be headed in the future.

This is an interesting case, as we take a look at this 23-year-old female who first comes in to see her psychiatrist with moderate depressive symptoms. At the time of the interview, her chief complaint included feeling like she’s lacking energy, she’s feeling depressed. She’s also reporting difficulty in paying attention, organizing her day, and accomplishing her tasks at work. Notably these symptoms started abruptly. Three weeks early, prior to that, she had been functioning better than usual, requiring very little sleep and getting more accomplished. Of significance, she reported two brief episodes of depression over the past 2 years. Each lasting about 2 months. And although the patient reported these depressive episodes as coming out of the blue, she learned after consulting with her therapist that they were related to significant psychosocial stress, stemming from the loss of her job and the deaths of 2 uncles, both of which were related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The patient reported that she still finds enjoyment talking to friends and socializing and she has hope of finding a new job and she’s constantly looking.

It’s noteworthy to bear in mind that in her first depressive episode she was treated with methylphenidate 25mg titrated up to 50 m and she stated feeling improved on this does with psychotherapy. Her second depressive episode, her does was bumped up to 100 mg which we saw improvement in depression, but she noted she felt a little activated and had trouble sleeping. With her third depressive episode, the therapist and PCP referred the patient over to a psychiatrist. Of great note should be her past psychological history: she was diagnosed with ADHD in middle school, during which time she responded well to methylphenidate. She continued to do well until her college years at which time she began experiencing difficulty falling asleep as well as irritability. At that time, she discontinued methylphenidate and was psychiatric drug free. She found that practicing mindfulness and yoga on a daily basis helped her residual ADHD symptoms. Of note, she had no history of suicidal thoughts or behavior, self-injurious behaviors, psychiatric hospitalization, or problems with substance abuse. Of note, regarding medical comorbidities, she was diagnosed a year earlier with type 2 diabetes, which was managed with metformin 1000 mg twice daily and her hemoglobin A1C was not poorly controlled. She was also diagnosed with high blood pressure 2 years earlier, that is managed by lisinopril 20 mg once daily. We noted that her BMI is 31, which is indicative of obesity. All other lab values were within normal limit. Significantly, her TSH was in the normal range and her urine toxicology screening was negative. Upon further querying of her family history, her maternal grandmother was diagnosed with a nervous breakdown and spent 2 months in a psychiatric hospital in her 30s. Her mother required little sleep, had a history of impulsive spending, and had a history of starting projects that she didn’t finish. The patient’s paternal uncles had a history of depression as well as alcohol abuse. Upon doing assessments, her PHQ9 is indicative of 18 points and her mood questionnaire she scored an 8.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Evaluating the Efficacy of Lumateperone for MDD and Bipolar Depression With Mixed Features

Blue Light Blockers: A Behavior Therapy for Mania

Efficacy of Modafinil for Treatment of Neurocognitive Impairment in Bipolar Disorder

Blue Light, Depression, and Bipolar Disorder

Securing the Future of Lithium Research

An Update on Early Intervention in Psychotic Disorders

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Sarah (bipolar disorder)

Case study details.

Sarah is a 42-year-old married woman who has a long history of both depressive and hypomanic episodes. Across the years she has been variable diagnoses as having major depression, borderline personality disorder, and most recently, bipolar disorder. Review of symptoms indicates that she indeed have multiple episodes of depression beginning in her late teens, but that clear hypomanic episodes later emerged. Her elevated interpersonal conflict, hyper-sexuality and alcohol use during her hypomanic episodes led to the provisional borderline diagnosis, but in the context of her full history, bipolar disorder appears the best diagnosis. Sarah notes that she is not currently in a relationship and that she feels alienated from her family. She has been taking mood stabilizers for the last year, but continues to have low level symptoms of depression. In the past, she has gone off her medication multiple times, but at present she says she is “tired of being in trouble all the time” and wants to try individual psychotherapy.

- Alcohol Use

- Elevated Mood

- Impulsivity

- Mania/Hypomania

- Mood Cycles

- Risky Behaviors

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. bipolar disorder.

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

- Open access

- Published: 06 November 2018

The challenges of living with bipolar disorder: a qualitative study of the implications for health care and research

- Eva F. Maassen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0211-0994 1 , 2 ,

- Barbara J. Regeer 1 ,

- Eline J. Regeer 2 ,

- Joske F. G. Bunders 1 &

- Ralph W. Kupka 2 , 3

International Journal of Bipolar Disorders volume 6 , Article number: 23 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

19 Citations

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

In mental health care, clinical practice is often based on the best available research evidence. However, research findings are difficult to apply to clinical practice, resulting in an implementation gap. To bridge the gap between research and clinical practice, patients’ perspectives should be used in health care and research. This study aimed to understand the challenges people with bipolar disorder (BD) experience and examine what these challenges imply for health care and research needs.

Two qualitative studies were used, one to formulate research needs and another to formulate healthcare needs. In both studies focus group discussions were conducted with patients to explore their challenges in living with BD and associated needs, focusing on the themes diagnosis, treatment and recovery.

Patients’ needs are clustered in ‘disorder-specific’ and ‘generic’ needs. Specific needs concern preventing late or incorrect diagnosis, support in search for individualized treatment and supporting clinical, functional, social and personal recovery. Generic needs concern health professionals, communication and the healthcare system.

Patients with BD address disorder-specific and generic healthcare and research needs. This indicates that disorder-specific treatment guidelines address only in part the needs of patients in everyday clinical practice.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a major mood disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of depression and (hypo)mania (Goodwin and Jamison 2007 ). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5 (DSM-5), the two main subtypes are BD-I (manic episodes, often combined with depression) and BD-II (hypomanic episodes, combined with depression) (APA 2014 ). The estimated lifetime prevalence of BD is 1.3% in the Dutch adult population (de Graaf et al. 2012 ), and BD is associated with high direct (health expenditure) and indirect (e.g. unemployment) costs (Fajutrao et al. 2009 ; Michalak et al. 2012 ), making it an important public health issue. In addition to the economic impact on society, BD has a tremendous impact on patients and their caregivers (Granek et al. 2016 ; Rusner et al. 2009 ). Even between mood episodes, BD is often associated with functional impairment (Van Der Voort et al. 2015 ; Strejilevich et al. 2013 ), such as occupational or psychosocial impairment (Huxley and Baldessarini 2007 ; MacQueen et al. 2001 ; Yasuyama et al. 2017 ). Apart from symptomatic recovery, treatment can help to overcome these impairments and so improve the person’s quality of life (IsHak et al. 2012 ).

Evidence Based Medicine (EBM), introduced in the early 1990s, is a prominent paradigm in modern (mental) health care. It strives to deliver health care based on the best available research evidence, integrated with individual clinical expertise (Sackett et al. 1996 ). EBM was introduced as a new paradigm to ‘de - emphasize intuition’ and ‘ unsystematic clinical experience’ (Guyatt et al. 1992 ) (p. 2420). Despite its popularity in principle (Barratt 2008 ), EBM has also been criticized. One such criticism is the ignorance of patients’ preferences and healthcare needs (Bensing 2000 ). A second criticism relates to the difficulty of adopting evidence-based treatment options in clinical practice (Bensing 2000 ), due to the fact that research outcomes measured in ‘the gold standard’ randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) seldom correspond to the outcomes clinical practice seeks and are not responsive to patients’ needs (Newnham and Page 2010 ). Moreover, EBM provides an overview on population level instead of individual level (Darlenski et al. 2010 ). Thus, adopting research evidence in clinical practice entails difficulties, resulting in an implementation gap.

To bridge the gap between research and clinical practice, it is argued that patients’ perspectives should be used in both health care and research. Patients have experiential knowledge about their illness, living with it in their personal context and their care needs (Tait 2005 ). This is valuable for both clinical practice and research as their knowledge complements that of health professionals and researchers (Tait 2005 ; Broerse et al. 2010 ; Caron-Flinterman et al. 2005 ). This source of knowledge can be used in the process of translating evidence into clinical practice (Schrevel 2015 ). Moreover, patient participation can enhance the clinical relevance of and support for research and the outcomes in practice (Abma and Broerse 2010 ). Hence, it is argued that these perspectives should be explicated and integrated into clinical guidelines, clinical practice, and research (Misak 2010 ; Rycroft-Malone et al. 2004 ).

Given the advantages of including patients’ perspectives, patients are increasingly involved in healthcare services (Bagchus et al. 2014 ; Larsson et al. 2007 ), healthcare quality (e.g. guideline development) (Pittens et al. 2013 ) and health-related research (e.g. agenda setting, research design) (Broerse et al. 2010 ; Boote et al. 2010 ; Elberse et al. 2012 ; Teunissen et al. 2011 ). However, patients’ perspectives on health care and on research are often studied separately. We argue that to be able to provide care focused on the patients and their needs, care and research must closely interact.

We hypothesize that the challenges BD patients experience and the associated care and research needs are interwoven, and that combining them would provide a more comprehensive understanding. We hypothesize that this more comprehensive understanding would help to close the gap between clinical practice and research. For this reason, this study aims to understand the challenges people with BD experience and examine what these challenges imply for healthcare and research needs.

To understand the challenges and needs of people with BD, we undertook two qualitative studies. The first aimed to formulate a research agenda for BD from a patient’s perspective, by gaining insights into their challenges and research needs. A second study yielded an understanding of the care needs from a patient’s perspective. In this article, the results of these two studies are combined in order to investigate the relationship between research needs and care needs. Challenges are defined as ‘difficulties patients face, due to having BD’. Care needs are defined as that what patients ‘desire to receive from healthcare services to improve overall health’ (Asadi-Lari et al. 2004 ) (p. 2). Research needs are defined as that what patients ‘desire to receive from research to improve overall health’.

Study on research needs

In this study, mixed-methods were used to formulate research needs from a patient’s perspective. First six focus group discussions (FGDs) with 35 patients were conducted to formulate challenges in living with BD and hopes for the future, and to formulate research needs arising from these difficulties and aspirations. These research needs were validated in a larger sample (n = 219) by means of a questionnaire. We have reported this study in detail elsewhere (Maassen et al. 2018 ).

Study on care needs

This study was part of a nationwide Dutch project to generate a practical guideline for BD: a translation of the existing clinical guideline to clinical practice, resulting in a standard of care that patients with BD could expect. The practical guideline (Netwerk Kwaliteitsontwikkeling GGZ 2017 ) was written by a taskforce comprising health professionals, patients. In addition to the involvement of three BD patients in the taskforce, a systematic qualitative study was conducted to gain insight into the needs of a broader group of patients.

Participants and data collection

To formulate the care needs of people with BD, seven FGDs were conducted, with a total of 56 participants, including patients (n = 49) and caregivers (n = 9); some participants were both patient and caregiver. The inclusion criteria for patients were having been diagnosed with BD, aged 18 years or older and euthymic at time of the FGDs. Inclusion criteria for caregivers were caring for someone with BD and aged 18 years or older. To recruit participants, a maximum variation sampling strategy was used to collect a broad range of care needs (Kuper et al. 2008 ). First, all outpatient clinics specialized in BD affiliated with the Dutch Foundation for Bipolar Disorder (Dutch: Kenniscentrum Bipolaire Stoornissen) were contacted by means of an announcement at regular meetings and by email if they were interested to participate. From these outpatient clinics, patients were recruited by means of flyers and posters. Second, patients were recruited at a quarterly meeting of the Dutch patient and caregiver association for bipolar disorder. The FGDs were conducted between March and May 2016.

The FGDs were designed to address challenges experienced in BD health care and areas of improvement for health care for people with BD. The FGDs were structured by means of a guide and each session was facilitated by two moderators. The leading moderator was either BJR or EFM, having both extensive experience with FGD’s from previous studies. The first FGD explored a broad range of needs. The subsequent six FGDs aimed to gain a deeper understanding of these care needs, and were structured according to the outline of the practical guideline (Netwerk Kwaliteitsontwikkeling GGZ 2017 ). Three chapters were of particular interest: diagnosis, treatment and recovery. These themes were discussed in the FGDs, two in each session, all themes three times in total. Moreover, questions on specific aspects of care formulated by the members of the workgroup were posed. The sessions took 90–120 min. The FGDs were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. A summary of the FGDs was sent to the participants for a member check.

Data analysis

To analyze the data on challenges and needs, a framework for thematic analysis to identify, analyze and report patterns (themes) in qualitative data sets by Braun and Clarke ( 2006 ) was used. First, we familiarized ourselves with the data by carefully reading the transcripts. Second, open coding was used to derive initial codes from the data. These codes were provided to quotes that reflected a certain challenge or care need. Third, we searched for patterns within the codes reflecting challenges and within those reflecting needs. For both challenges and needs, similar or overlapping codes were clustered into themes. Subsequently, all needs were categorized as ‘specific’ or ‘generic’. The former are specific to BD and the latter are relevant for a broad range of psychiatric illnesses. Finally, a causal analysis provided a clear understanding of how challenges related to each other and how they related to the described needs.

To analyze the data on needs regarding recovery, four domains were distinguished, namely clinical, functional, social and personal recovery (Lloyd et al. 2008 ; van der Stel 2015 ). Clinical recovery refers to symptomatic remission; functional recovery concerns recovery of functioning that is impaired due to the disorder, particularly in the domain of executive functions; social recovery concerns the improvement of the patient’s position in society; personal recovery concerns the ability of the patient to give meaning to what had happened and to get a grip on their own life. The analyses were discussed between BR and EM. The qualitative software program MAX QDA 11.1.2 was used (MaxQDA).

Ethical considerations

According to the Medical Ethical Committee of VU University Medical Center, the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act does not apply to the current study. All participants gave written or verbal informed consent regarding the aim of the study and for audiotaping and its use for analysis and scientific publications. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw from the study at any time. Anonymity was ensured.

This section is in three parts. The first presents the participants’ characteristics. The second presents the challenges BD patients face, derived from both studies, and the disorder-specific care and research needs associated with these challenges. The third part describes the generic care needs that patients formulated.

Characteristics of the participants

In the study on care needs, 56 patients and caregivers participated. The mean age of the participants was 52 years (24–75), of whom 67.8% were women. The groups varied from four to sixteen participants, and all groups included men and women. Of all participants 87.5% was diagnosed with BD, of whom 48.9% was diagnosed with BD I. 3.5% was both caregivers and diagnosed with BD. Of 4 patients the age was missing, and from 6 patients the bipolar subtype.

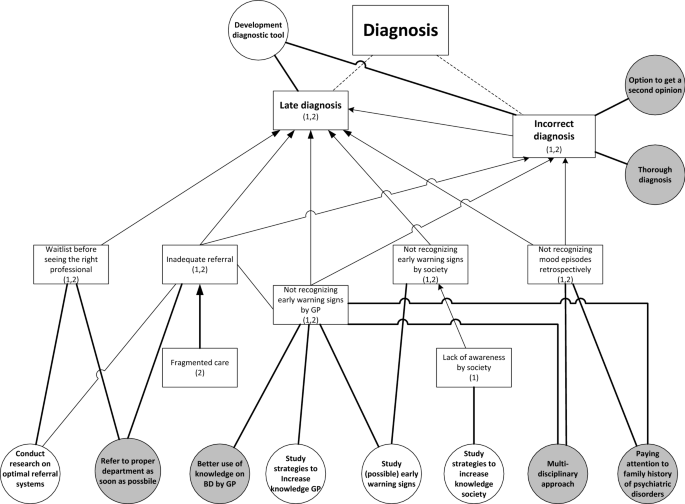

Despite the fact that participants acknowledge the inevitable diagnostic difficulties of a complex disorder like BD, in both studies they describe a range of challenges in different phases of the diagnostic process (Fig. 1 ). Patients explained that the general practitioner (GP) and society in general did not recognize early-warning signs and mood swings were not well interpreted, resulting in late or incorrect diagnosis. Patients formulated a need for more research on what early-warning signs could be and on how to improve GPs’ knowledge about BD. Formulated care needs were associated with GPs using this knowledge to recognize early-warning signs in individual patients. One participant explained that certain symptoms must be noticed and placed in the right context:

Challenges with diagnosis (squares) including relating research needs (white circles) and care needs (grey circles). (1): mentioned in study on research needs; (2): mentioned in study on care needs. Dotted lines: division of challenges into sub challenges. Arrows: causal relation between challenges

I call it, ‘testing overflow of ideas’. [….] When it happens for the first time you yourself do not recognize it. Someone else close to you or the health professional, who is often not involved yet, must signal it. (FG6)

Moreover, these challenges are associated with the need to pay attention to family history and to use a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis to benefit from multiple perspectives. The untimely recognition of early symptoms also results in another challenge: inadequate referral to the right specialized health professional. After referral, people often face a waiting list, again causing delay in the diagnostic process. These challenges result in the need for research on optimal referral systems and the care need for timely referral. One participant described her process after the GP decided to refer her:

But, yes, at that moment the communication wasn’t good at all. Because the general practitioner said: ‘she urgently has to be seen by someone’. Subsequently, three weeks went by, until I finally arrived at depression [department]. And at that department they said: ‘well, you are in the wrong place, you need to go to bipolar [department ]’. (FG1)

The challenge of being misdiagnosed is associated with the need to be able to ask for a second opinion and to have a timely and thorough diagnosis. On the one hand, it is important for patients that health professionals quickly understand what is going on, on the other hand that health professionals take the time to thoroughly investigate the symptoms by making several appointments.

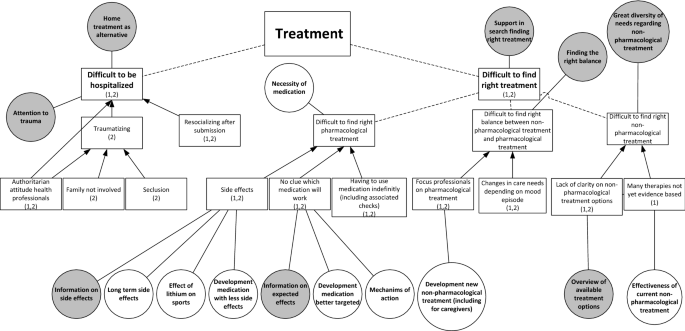

From both studies, two main challenges related to the treatment of BD were derived (Fig. 2 ). The first is finding appropriate and satisfactory treatment. Participants explained that it is difficult to find the right medication and dosage that is effective and has acceptable side-effects. One participant illustrates:

Challenges with treatment (squares) including relating research needs (white circles) and care needs (grey circles). (1): mentioned in study on research needs; (2): mentioned in study on care needs. Dotted lines: division of challenges into sub challenges. Arrows: causal relation between challenges

I think, at one point, we have to choose, either overweight or depressed. (FG1)

Some participants said that they struggle with having to use medication indefinitely, including the associated medical checks. The difficult search for the right pharmacological treatment results in the need for research on long-term side-effects, on the mechanism of action of medicine and on the development of better targeted medication with fewer adverse side-effects. In care, patients would appreciate all the known information on the side-effects and intended effects. One participant explained the importance of being properly informed about medication:

I don’t read anything [about medication], because then I wouldn’t dare taking it. But I do think, when you explain it well, the advantages, the disadvantages, the treatment, the idea behind it, that would help a lot in compliance. (FG1)

A second aspect is the challenge of finding non-pharmacological therapies that fit patients’ needs. They said they and the health professionals often do not know which non-pharmacological therapies are available and effective:

But we found the carefarm ourselves Footnote 1 [….]. You have to search for yourself completely. Yes, I actually hoped that that would be presented to you, like: ‘this would be something for you’. (FG3)

Participants mentioned a variety of non-pharmacological therapies they found useful, namely cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), EMDR, running therapy, social-rhythm training, light therapy, mindfulness, psychotherapy, psychoeducation, and training in living with mood swings. They formulated the care need to receive an overview of all available treatment options in order to find a treatment best suited to their needs. They would appreciate research on the effectiveness of non-pharmacological treatments.

A third aspect within this challenge is finding the right balance between non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment. Participants differed in their opinion about the need for medication. Whereas some participants stated that they need medication to function, others pointed out that they found non-pharmacological treatments effective, resulting in less or no medication use. They explained that the preferred balance can also change over time, depending on their mood. However, they experience a dominant focus on pharmacological treatment by the health professionals. To address this challenge, patients need support in searching for an appropriate balance.

Next to the challenge of finding appropriate and satisfactory treatment, a second treatment-related challenge is hospitalization. Participants often had a traumatic experience, due to seclusion, the authoritarian attitudes of clinical staff, and not involving their family. Patients therefore found it important to try preventing being hospitalized, for example by means of home treatment, which some participants experienced positively. Despite the challenges relating to hospitalization, participants did acknowledge that in some cases it cannot be avoided, in which case they urged for close family involvement, open communication and being treated by their own psychiatrist. Still, in the study on research needs, hospitalization did not emerge as an important research theme.

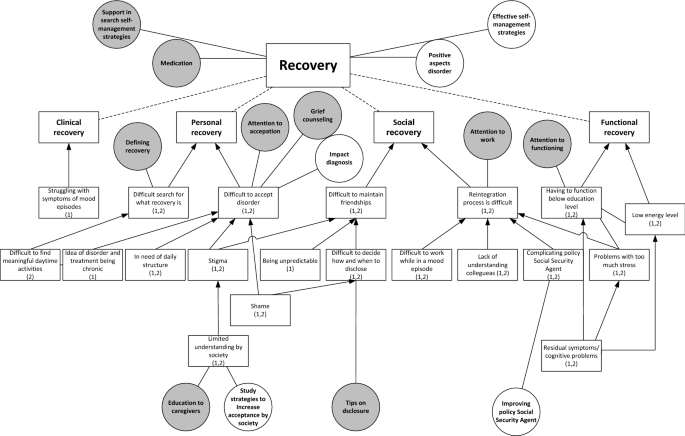

In both studies, participants described challenges in all four domains of recovery: clinical, functional, social and personal (Fig. 3 ). In relation to clinical recovery, participants struggled with the symptoms of mood episodes, the psychosis and the fear of a future episode. In contrast, some participants mentioned that they sometimes miss the hypomanic state they had experienced previously due to effective medical treatment. In the domain of functional recovery, participants contended with having to function below their educational level due to residual symptoms, such as cognitive problems, due to the importance of preventing stress in order to reduce the risk of a new episode, and because of low energy levels. This leads to the care need that health professionals should pay attention to the level of functioning of their patients.

Challenges with recovery (squares) including relating research needs (white circles) and care needs (grey circles). (1): mentioned in study on research needs; (2): mentioned in study on care needs. Dotted lines: division of challenges into sub challenges. Arrows: causal relation between challenges

In the domain of social recovery, participants described challenges with maintaining friendships, due to stigma, being unpredictable and with deciding when to disclose the disorder. The latter resulted in the care need for tips on disclosure. Moreover, patients experienced challenges with reintegration to work, due to colleagues’ lack of understanding, problems with functioning during an episode, the complicating policy of the (Dutch) Employee Insurance Agency Footnote 2 in relation to the fluctuating course of BD and the negative impact of stress. These challenges are associated with the care need that health professionals should pay attention to work and the need for research on how to improve the Social Security Agency’s policy.

For their personal recovery, participants struggled with acceptance of the disorder, due to shame, stigma, having to live by structured rules and disciplines, and the chronic nature of BD. This results in care needs for grief counselling and attention to acceptance and the need for research on the impact of being diagnosed with BD. Limited understanding within society also causes problems with acceptance, corresponding with the care need for education for caregivers and for research on how to increase social acceptance. Another challenge in personal recovery was discovering what recovery means and what constitute meaningful daily activities. Patients appreciated the support of health professionals in this area. One participant described the difficult search for the meaning of recovery:

I have been looking to recover towards the situation [before diagnosis] for a long time; that I could do what I always did and what I liked. But then I was confronted with the fact that I shouldn’t expect that to happen, or only with a lot of effort. (…) Then you start thinking, now what? A compromise. I don’t want to call that recovery, but it is a recovered, partly accepted, situation. But it is not recovery as I expected it to be. (FG5)

In general, participants considered frequent contact with a nurse or psychiatrist supportive, to help them monitor their mood and help them find (efficient) self-management strategies. Most participants appreciated the involvement of caregivers in the treatment and contact with peers.

Generic care needs

We have described BD-specific needs, but patients mentioned also mentioned several generic care needs. The latter are clustered into three categories. The first concerns the health professionals . Participants stressed the importance of a good health professional, who carefully listens, takes time, and makes them feel understood, resulting in a sense of connection. Furthermore, a good health professional treats beyond the guideline, and focuses on the needs of the individual patient. When there is no sense of connection, it should be possible to change to another health professional. The second category concerns communication between the patient and the health professional . Health professionals should communicate in an open, honest and clear way both in the early diagnostic phase and during treatment. Open communication facilitates individualized care, in which the patient is involved in decision making. In addition, participants wanted to be treated as a person, not as a patient, and according to a strength-based approach. The third category concerns needs at the level of the healthcare system . Participants struggled with the availability of the health professionals and preferred access to good care 24/7 and being able to contact their health professional quickly when necessary. Currently, according to the participants, the care system is not geared to the mood swings of BD, because patients often faced waiting lists before they could see a health professional.

Is adequate treatment also having a number from a mental health institution you can always call when you are in need, that you can go there? And not that you can go in three weeks, but on a really short notice. So at least a phone call. (FG3)

Participants were often frustrated by the limited collaboration between health professionals, within their own team, between departments of the organization, and between different organizations, including complementary health professionals. They would appreciate being able to merge their conventional and complementary treatment, with greater collaboration among the different health professionals. Furthermore, they would like continuity of health professionals as this improves both the diagnostic phase and treatment, and because that health professional gets to know the patient.

We hypothesized that research and care needs of patients are closely intertwined and that understanding these, by explicating patients’ perspectives, could contribute to closing the gap between research and care. Therefore, this study aimed to understand the challenges patients with BD face and examine what these imply for both healthcare and research. In the study on needs for research and in the study on care needs, patients formulated challenges relating to receiving the correct diagnosis, finding the right treatment, including the proper balance between non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment, and to their individual search for clinical, functional, social and personal recovery. The formulated needs in both studies clearly reflected these challenges, leading to closely corresponding needs. Another important finding of our study is that patients not only formulate disorder-specific needs, but also many generic needs.

The needs found in our study are in line with the current literature on the needs of patients with BD, namely for more non-pharmacological treatment (Malmström et al. 2016 ; Nestsiarovich et al. 2017 ), timely recognition of early-warning signs and self-management strategies to prevent a new episode (Goossens et al. 2014 ), better information on treatment and treatment alternatives (Malmström et al. 2016 ; Neogi et al. 2016 ) and coping with grief (Goossens et al. 2014 ). Moreover, the need for frequent contact with health professionals, being listened to, receiving enough time, shared decision-making on pharmacological treatment, involving caregivers (Malmström et al. 2016 ; Fisher et al. 2017 ; Skelly et al. 2013 ), and the urge for better access to health care and continuity of health professionals (Nestsiarovich et al. 2017 ; Skelly et al. 2013 ) are confirmed by the literature. Our study added to this set of literature by providing insights in patients’ needs in the diagnostic process and illustrating the interrelation between research needs and care needs from a patient’s perspective.

The generic healthcare needs patients addressed in this study are clustered into three categories: the health professional , communication between the patient and the health professional and the health system. These categories all fit in a model of patient-centered care (PCC) by Maassen et al. ( 2016 ) In their review, patients’ perspectives on good care are compared with academic perspectives of PCC and a model of PCC is created comprising four dimensions: patient, health professional, patient – professional interaction and healthcare organization. All the generic needs formulated in this study fit into these four dimensions. The need to be treated as a person with strengths fits the dimension ‘patient’, and the need for a good health professional who carefully listens, takes time and makes them feel understood, resulting in a good connection with the professional, fits the dimension ‘health professional’ of this model. Furthermore, patients in this study stressed the importance of open communication in order to provide individualized care, which fits the dimension of ‘patient–professional interaction’. The urge for better access to health care, geared to patients’ mood swings and the need for better collaboration between health professionals and continuity of health professionals fits the dimension of ‘health care organization’ of the model. This study confirms the findings from the review and contributes to the literature stressing the importance of a patient-centered care approach (Mills et al. 2014 ; Scholl et al. 2014 ).

In the prevailing healthcare paradigm, EBM, the best available evidence should guide treatment of patients (Sackett et al. 1996 ; Darlenski et al. 2010 ). This evidence is translated into clinical and practical guidelines, which thus facilitate EBM and could be used as a decision-making tool in clinical practice (Skelly et al. 2013 ). For many psychiatric disorders, treatment is based on such disorder - specific clinical and practical guidelines. However, this disease-focused healthcare system has contributed to its fragmented nature Stange ( 2009 ) argues that this fragmented care system has expanded without the corresponding ability to integrate and personalize accordingly. We argue that acknowledging that disorder - specific clinical and practical guidelines address only parts of the care needs is of major importance, since otherwise important aspects of the patients’ needs will be ignored. Because there is an increasing acknowledgement that health care should be responsive to the needs of patients and should change from being disease-focused towards being patient-focused (Mead and Bower 2000 ; Sidani and Fox 2014 ), currently in the Netherlands generic practical guidelines are written on specific care themes (e.g. co-morbidity, side-effects, daily activity and participation). These generic practical guidelines address some of the generic needs formulated by the patients in our study. We argue that in addition to disorder-specific guidelines, these generic practical guidelines should increasingly be integrated into clinical practice, while health professionals should continuously be sensitive to other emerging needs. We believe that an integration of a disorder-centered and a patient-centered focus is essential to address all needs a patient.

Strengths, limitations and future research

This study has several strengths. First, it contributes to the literature on the challenges and needs of patients with BD. Second, the study is conducted from a patient’s perspective. Moreover, addressing this aim by conducting two separate studies enabled us to triangulate the data.

This study also has several limitations. First, this study reflects the challenges, care needs and research needs of Dutch patient with BD and caregivers. Despite the fact that a maximum variation sampling strategy was used to derive a broad range of challenges and needs throughout the Netherlands, the Dutch setting of the study may limit the transferability to other countries. To understand the overlap and differences between countries, similar research should be conducted in other contexts. Second, given the design of the study, we could not differentiate between patients and caregivers since they participated together in the FGDs. More patients than caregivers participated in the study. For a more in-depth understanding of the challenges and needs faced by caregivers, in future research separate FGDs should be conducted. Third, due to the fixed outline of the practical guideline used to conduct the FGDs, only the healthcare needs for diagnosis, treatment and recovery of BD are studied. Despite the fact that these themes might cover a broad range of health care, it could have resulted in overlooking certain needs in related areas of well-being. Therefore, future research should focus on needs outside of these themes in order to provide a complete set of healthcare needs.

Patients and their caregivers face many challenges in living with BD. Our study contributes to the literature on care and research needs from a patient perspective. Needs specific for BD are preventing late or incorrect diagnosis, support in search for individualized treatment, and supporting clinical, functional, social and personal recovery. Generic healthcare needs concern health professionals, communication and the healthcare system. This explication of both disorder-specific and generic needs indicates that clinical practice guidelines should address and integrate both in order to be responsive to the needs of patients and their caregivers.

Care farm: farms that combine agriculture and services for people with disabilities (Iancu 2013 ). These farms are used as interventions in mental care throughout Europe and the USA to facilitate recovery (Iancu et al. 2014 ).

A government agency involved in the implementation of employee insurance and providing labor market and data services.

Abma T, Broerse J. Patient participation as dialogue: setting research agendas. Health Expect. 2010;13(2):160–73.

Article Google Scholar

APA. Beknopt overzicht van de criteria (DSM-5). Nederlands vertaling van de Desk Reference to the Diagnostic Criteria from DSM-5. Amsterdam: Boom; 2014.

Google Scholar

Asadi-Lari M, Tamburini M, Gray D. Patients’ needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:1–15.

Bagchus C, Dedding C, Bunders JFG. “I”m happy that I can still walk’—participation of the elderly in home care as a specific group with specific needs and wishes. Health Expect. 2014;18(6):1–9.

Barratt A. Evidence based medicine and shared decision making: the challenge of getting both evidence and preferences into health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):407–12.

Bensing J. Bridging the gap. The separate worlds of evidence-based medicine and patient-centered medicine. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;39:17–25.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Boote J, Baird W, Beecroft C. Public involvement at the design stage of primary health research: a narrative review of case examples. Health Policy. 2010;95(1):10–23.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Broerse J, Zweekhorst M, van Rensen A, de Haan M. Involving burn survivors in agenda setting on burn research: an added value? Burns. 2010;36(2):217–31.

Caron-Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW, Bunders JFG. The experiential knowledge of patients: a new resource for biomedical research? Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(11):2575–84.

Darlenski RB, Neykov NV, Vlahov VD, Tsankov NK. Evidence-based medicine: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28(5):553–7.

de Graaf R, ten Have M, van Gool C, van Dorsselaer S. Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(2):203–13.

Elberse J, Pittens C, de Cock Buning T, Broerse J. Patient involvement in a scientific advisory process: setting the research agenda for medical products. Health Policy. 2012;107(2–3):231–42.

Fajutrao L, Locklear J, Priaulx J, Heyes A. A systematic review of the evidence of the burden of bipolar disorder in Europe. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5(1):3.

Fisher A, Manicavasagar V, Sharpe L, Laidsaar-Powell R, Juraskova I. A qualitative exploration of patient and family views and experiences of treatment decision-making in bipolar II disorder. J Ment Health. 2017;27(1):66–79.

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-depressive illness: bipolar disorder and recurrent depression. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Goossens P, Knoopert-van der Klein E, Kroon H, Achterberg T. Self reported care needs of outpatients with a bipolar disorder in the Netherlands: a quantitative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;14:549–57.

Granek L, Danan D, Bersudsky Y, Osher Y. Living with bipolar disorder: the impact on patients, spouses, and their marital relationship. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(2):192–9.

Guyatt G, Cairns J, Churchill D, Cook D, Haynes B, Hirsh J, Irvine J, Levine M, Levine M, Nishikawa J, Sackett D, Brill-Edwards P, Gerstein H, Gibson J, Jaeschke R, Kerigan A, Neville A, Panju A, Detsky A, Enkin M, Frid P, Gerrity M, Laupacis A, Lawrence V, Menard J, Moyer V, Mulrow C, Links P, Oxman A, Sinclair J, Tugwell P. Evidence-based medicine: a new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420–5.

Huxley N, Baldessarini R. Disability and its treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(1–2):183–96.

Iancu SC. New dynamics in mental health recovery and rehabilitation. Amsterdam: Vu University; 2013.

Iancu SC, Zweekhorst MBM, Veltman DJ, Van Balkom AJLM, Bunders JFG. Mental health recovery on care farms and day centres: a qualitative comparative study of users’ perspectives. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(7):573–83.

IsHak WW, Brown K, Aye SS, Kahloon M, Mobaraki S, Hanna R. Health-related quality of life in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14(1):6–18.

Kuper A, Lingard L, Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337(7671):687–9.

Larsson IE, Sahlsten MJM, Sjöström B, Lindencrona CSC, Plos KAE. Patient participation in nursing care from a patient perspective: a grounded theory study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21(3):313–20.

Lloyd C, Waghorn G, Williams PL. Conceptualising recovery in mental health. Br J Occup Ther. 2008;71:321–8.

Maassen EF, Schrevel SJC, Dedding CWM, Broerse JEW, Regeer BJ. Comparing patients’ perspectives of “good care” in Dutch outpatient psychiatric services with academic perspectives of patient-centred care. J Ment Health. 2016;26(1):1–11.

Maassen EF, Regeer BJ, Bunders JGF, Regeer EJ, Kupka RW. A research agenda for bipolar disorder developed from a patient’s perspective. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.061 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

MacQueen GM, Young LT, Joffe RT. A review of psychosocial outcome in patients with bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103(3):163–70.

Malmström E, Hörberg N, Kouros I, Haglund K, Ramklint M. Young patients’ views about provided psychiatric care. Nord J Psychiatry. 2016;70(7):521–7.

MaxQDA [Internet]. Available from: https://www.maxqda.com/ . Accessed 2 Aug 2018.

Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1087–110.

Michalak EE, Hole R, Livingston JD, Murray G, Parikh SV, Lapsley S, et al. Improving care and wellness in bipolar disorder: origins, evolution and future directions of a collaborative knowledge exchange network. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2012;6:16.

Mills I, Frost J, Cooper C, Moles DR, Kay E. Patient-centred care in general dental practice—a systematic review of the literature. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(1):64.

Misak CJ. Narrative evidence and evidence-based medicine. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(2):392–7.

Neogi R, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Health-care needs of remitted patients with bipolar disorder: a comparison with schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry. 2016;6(4):431–41.

Nestsiarovich A, Hurwitz NG, Nelson SJ, Crisanti AS, Kerner B, Kuntz MJ, et al. Systemic challenges in bipolar disorder management: a patient-centered approach. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(8):676–88.

Netwerk Kwaliteitsontwikkeling GGZ. Zorgstandaard Bipolaire stoornissen. 2017;1–54.

Newnham EA, Page AC. Bridging the gap between best evidence and best practice in mental health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(1):127–42.

Pittens C, Noordegraaf A, van Veen S, Broerse J. The involvement of gynaecological patients in the development of a clinical guideline for resumption of (work) activities in the Netherlands. Health Expect. 2013;18:1397–412.

Rusner M, Carlsson G, Brunt D, Nyström M. Extra dimensions in all aspects of life—the meaning of life with bipolar disorder. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2009;4(3):159–69.

Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A, Harvey G, Kitson A, McCormack B. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(1):81–90.

Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Gray J, Haynes R, Richardson W. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J. 1996;312(7023):71–2.

Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, Dirmaier J. An integrative model of patient-centeredness—a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e107828.

Schrevel SJC. Surrounded by controversy: perspectives of adults with ADHD and health professionals on mental healthcare. Amsterdam: VU University; 2015.

Sidani S, Fox M. Patient-centered care: clarification of its specific elements to facilitate interprofessional care. J Interprof Care. 2014;28(2):134–41.

Skelly N, Schnittger RI, Butterly L, Frorath C, Morgan C, McLoughlin DM, et al. Quality of care in psychosis and bipolar disorder from the service user perspective. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(12):1672–85.

Stange KC. The problem of fragmentation and the need for integrative solutions. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):100–3.

Strejilevich SA, Martino DJ, Murru A, Teitelbaum J, Fassi G, Marengo E, et al. Mood instability and functional recovery in bipolar disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128(3):194–202.

Tait L. Encouraging user involvement in mental health services. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2005;11(3):168–75.

Teunissen T, Visse M, De Boer P, Abma TA. Patient issues in health research and quality of care: an inventory and data synthesis. Health Expect. 2011;16:308–22.

van der Stel. Het begrip herstel in de psychische gezondheidzorg, Leiden; 2015. p. 1–3.

Van Der Voort TYG, Van Meijel B, Hoogendoorn AW, Goossens PJJ, Beekman ATF, Kupka RW. Collaborative care for patients with bipolar disorder: effects on functioning and quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2015;179:14–22.

Yasuyama T, Ohi K, Shimada T, Uehara T, Kawasaki Y. Differences in social functioning among patients with major psychiatric disorders: interpersonal communication is impaired in patients with schizophrenia and correlates with an increase in schizotypal traits. Psychiatry Res. 2017;249:30–4.

Download references

Authors’ contributions

EFM designed the study, contributed to the data collection, managed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BJR designed the study and contributed to the data collection, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. JFGB contributed to the study design and critical revision of the manuscript. EJR contributed to the study conception and critical revision of the manuscript. RWK contributed to the study design, acquisition of data, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The authors received no financial support for the research.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Athena Institute, Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, VU University Amsterdam, Boelelaan 1085, 1081HV, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Eva F. Maassen, Barbara J. Regeer & Joske F. G. Bunders

Altrecht Institute for Mental Health Care, Nieuwe Houtenseweg 12, 3524 SH, Utrecht, Netherlands

Eva F. Maassen, Eline J. Regeer & Ralph W. Kupka

Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute, Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Psychiatry, De Boelelaan 1117, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Ralph W. Kupka

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eva F. Maassen .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maassen, E.F., Regeer, B.J., Regeer, E.J. et al. The challenges of living with bipolar disorder: a qualitative study of the implications for health care and research. Int J Bipolar Disord 6 , 23 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-018-0131-y

Download citation

Received : 06 June 2018

Accepted : 22 August 2018

Published : 06 November 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-018-0131-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- General Healthcare

- Personal Recovery

- Focus Group Discussions

- Professional-patient Interaction

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Psychiatric Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: The Case of Janice

- Published: February 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Chapter 5 covers the psychiatric treatment of bipolar disorder, including a case history, key principles, assessment strategy, differential diagnosis, case formulation, treatment planning, nonspecific factors in treatment, potential treatment obstacles, ethical considerations, common mistakes to avoid in treatment, and relapse prevention.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.