John Dewey on Education: Impact & Theory

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

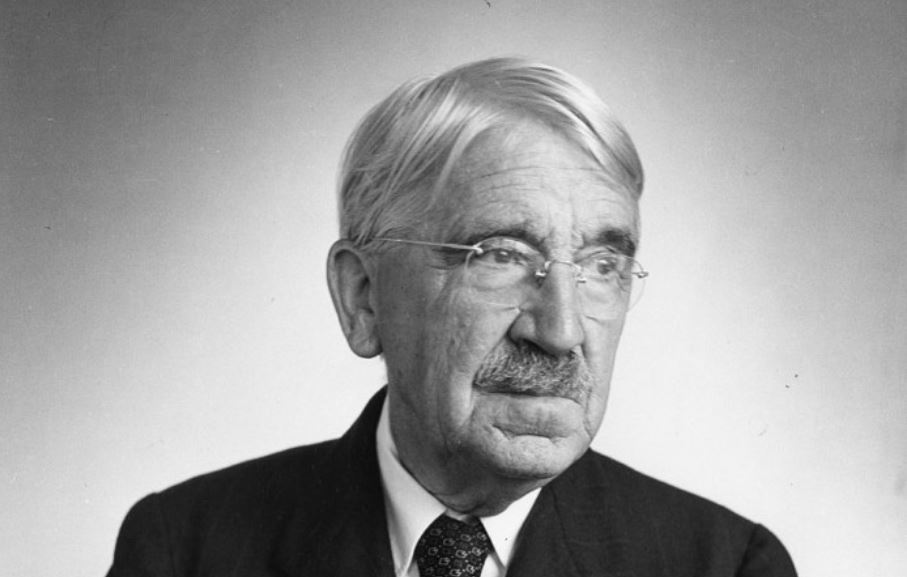

- John Dewey (1859—1952) was a psychologist, philosopher, and educator who made contributions to numerous topics in philosophy and psychology. His work continues to inform modern philosophy and educational practice today.

- Dewey was an influential pragmatist, a movement that rejected most philosophy at the time in favor of the belief that things that work in a practical situation are true, while those that do not are false. This view would go on to influence his educational philosophy.

- Dewey was also a functionalist. Inspired by the ideas of Charles Darwin, he believed that humans develop behaviors as an adaptation to their environment.

- Dewey’s influential education is marked by an emphasis on the belief that people learn and grow as a result of their experiences and interactions with the world. He aimed to shape educational environments so that they would promote active inquiry but did not do away with traditional instruction altogether.

- Outside of education and philosophy, Dewey also devised a theory of emotions in response to Darwin’s ideas. In this theory, he argued that the behaviors that arise from emotions were, at some point, beneficial to the survival of organisms.

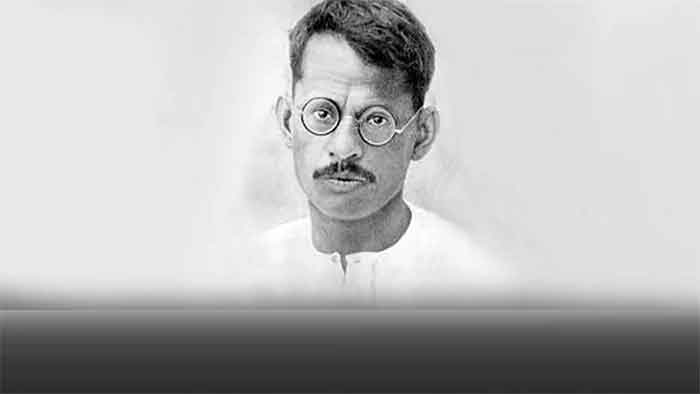

John Dewey was an American psychologist, philosopher, educator, social critic, and political activist. He made contributions to numerous fields and topics in philosophy and psychology.

Besides being a primary originator of both functionalism and behaviorism psychology , Dewey was a major inspiration for several movements that shaped 20th-century thought, including empiricism, humanism, naturalism, contextualism, and process philosophy (Simpson, 2006).

Dewey was born in Burlington, Vermont, in 1859 and began his career at the University of Michigan before becoming the chairman of the department of philosophy, psychology, and pedagogy at the University of Chicago.

In 1899, Dewey was elected president of the American Psychological Association and became president of the American Philosophical Association five years later.

Dewey traveled as a philosopher, social and political theorist, and educational consultant and remained outspoken on education, domestic and international politics, and numerous social movements.

Dewey’s views and writings on educational theory and practice were widely read and accepted. He held that philosophy, pedagogy, and psychology were closely interrelated.

Dewey also believed in an “instrumentalist” theory of knowledge, in which ideas are seen to exist mainly as instruments for creating solutions to problems encountered in the environment (Simpson, 2006).

Contributions to Philosophy and Psychology

Dewey is one of the central figures and founders of pragmatism in America despite not identifying himself as a pragmatist.

Pragmatism teaches that things that are useful — meaning that they work in a practical situation — are true, and what does not work is false (Hildebrand, 2018).

This rejected the threads of epistemology and metaphysics that ran through modern philosophy in favor of a naturalistic approach that viewed knowledge as an active adaptation of humans to their environment (Hildebrand, 2018).

Dewey held that value was not a function of purely social construction but a quality inherent to events. Dewey also believed that experimentation was a reliable enough way to determine the truth of a concept.

Functionalism

Dewey is considered a founder of the Chicago School of Functional Psychology, inspired by Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, as well as the ideas of William James and Dewey’s own instrumental philosophy.

As chair of philosophy, psychology, and education at the University of Chicago from 1894-1904, Dewey was highly influential in establishing the functional orientation amongst psychology faculty like Angell and Addison Moore.

Scholars widely consider Dewey’s 1896 paper, The Reflex Arc Concept in Psychology , to be the first major work in the functionalist school.

In this work, Dewey attacked the methods of psychologists such as Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener, who used stimulus-response analysis as the basis of psychological theories.

Psychologists such as Wund and Titchener believed that all human behaviors could be broken down into a series of fundamental laws and that all human behavior originates as a learned adaptation to the presence of certain stimuli in one’s environment (Backe, 2001).

Dewey considered Wundt and Titchener’s approach to be flawed because it ignored both the continuity of human behavior and the role that adaptation plays in creating it.

In contrast, Dewey’s functionalism sought to consider organisms in total as they functioned in their environment. Rather than being passive receivers of stimuli, Dewey perceived organisms as active perceivers (Backe, 2001).

Chicago School

The Chicago school refers to the functionalist approach to psychology that emerged at the University of Chicago in the late 19th century. Key tenets of functional psychology included:

- Studying the adaptive functions of consciousness and how mental processes help organisms adjust to their environment

- Explaining psychological phenomena in terms of their biological utility

- Focusing on the practical operations of the mind rather than contents of consciousness

Educational Philosophy

John Dewey was a notable educational reformer and established the path for decades of subsequent research in the field of educational psychology.

Influenced by his philosophical and psychological theories, Dewey’s concept of instrumentalism in education stressed learning by doing, which was opposed to authoritarian teaching methods and rote learning.

These ideas have remained central to educational philosophy in the United States. At the University of Chicago, Dewey founded an experimental school to develop and study new educational methods.

He experimented with educational curricula and methods and advocated for parental participation in the educational process (Dewey, 1974).

Dewey’s educational philosophy highlights “pragmatism,” and he saw the purpose of education as the cultivation of thoughtful, critically reflective, and socially engaged individuals rather than passive recipients of established knowledge.

Dewey rejected the rote-learning approach driven by a predetermined curriculum, the standard teaching method at the time (Dewey, 1974).

Dewey also rejected so-called child-centered approaches to education that followed children’s interests and impulses uncritically. Dewey did not propose an entirely hands-off approach to learning.

Dewey believed that traditional subjects were important but should be integrated with the strengths and interests of the learner.

In response, Dewey developed a concept of inquiry, which was prompted by a sense of need and was followed by intellectual work such as defining problems, testing hypotheses, and finding satisfactory solutions.

Dewey believed that learning was an organic cycle of doubt, inquiry, reflection, and the reestablishment of one’s sense of understanding.

In contrast, the reflexive arc model of learning popular in his time thought of learning as a mechanical process that could be measured by standardized tests without reference to the role of emotion or experience in learning.

Rejecting the assumption that all of the big questions and ideas in education are already answered, Dewey believed that all concepts and meanings could be open to reinvention and improvement and that all disciplines could be expanded with new knowledge, concepts, and understandings (Dewey, 1974).

Philosophy of Education

Dewey believed that people learn and grow as a result of their experiences and interactions with the world. These compel people to continually develop new concepts, ideas, practices, and understandings.

These, in turn, are refined through and continue to mediate the learner’s life experiences and social interactions. Dewey believed that (Hargraves, 2021):

| Interactions and communications focused on enhancing and deepening shared meanings increase the potential for learning and development. Dewey believed that when students communicate ideas and meanings within a group, they have the opportunity to consider, take on, and work with the perspectives, ideas, and experiences of other students. |

| Shared activities are an important context for learning and development. Dewey valued real-life contexts and problems as educational experiences. He believed that if students only passively perceive a problem and do not experience its consequences meaningfully, emotionally, and reflectively, they are unlikely to adapt and revise their habits or , or will only do so superficially. |

| Students learn best when their interests are engaged: according to Dewey, it is important to develop ideas, activities, and events that stimulate students” interests and to which teaching can be geared. Teaching and lecturing can be appropriate so long as they are geared toward helping students analyze or develop an intellectual insight into a specific and meaningful situation. |

| Learning begins with a student’s emotional response: this spurs further emotional inquiry. Following this belief, Dewey advocated for what he called “aesthetic” experiences: dramatic, compelling, unifying, or transformative experiences that enliven and absorb students. |

| Students should engage in active learning and inquiry: Rather than teaching students to accept any seemingly valid explanations, Dewey believed that education’s purpose is to give students opportunities to discover information and ideas through their own effort in a teacher-structured environment. Students could then put this knowledge to use by defining and solving problems as well as determining the validity and worth of ideas and theories. However, teachers could also provide explicit instruction as appropriate. |

| Inquiry involves students reflecting on their experiences in a way that helps them adapt their habits of action. Dewey believed that experiences should involve transaction: an active phase where a student does something — as well as a phase of “undergoing” — one where a student observes the effect that their action has had. |

| Education is a key way of developing skills for democratic activity: Dewey believed that recognizing and appreciating differences was a vehicle that students could use to expand their experiences and open up new ways of thinking rather than closing off their own beliefs and habits. |

Empirical Validity and Criticism

Despite its wide application in modern theories of education, many scholars have noted the lack of empirical evidence in favor of Dewey’s theories of education directly.

Nonetheless, Dewey’s theory of how students learn aligns with empirical studies that examine the positive impact of interactions with peers and adults on learning (Göncü & Rogoff, 1998).

Researchers have also found a link between heightened engagement and learning outcomes.

This has resulted in the development of educational strategies such as making meaningful connections to students” home lives and encouraging student ownership of their learning (Turner, 2014).

Theory of Emotions

Dewey vs. darwin.

Another influential piece of philosophy that Dewey created was his theory of emotion (Cunningham, 1995).

Dewey reconstructed Darwin’s theory of emotions, which he believed was flawed for assuming that the expression of emotion is separate from and subsequent to the emotion itself.

Darwin also argued that behavior that expresses emotion serves the individual in some way when the individual is in a particular state of mind. These can also cause behaviors that are not useful.

Dewey, however, claimed that the function of emotional behaviors is not to express emotion but to be acts that value someone’s survival. Dewey believed that emotion is separate from other behaviors because it involves an attitude toward an object. The intention of the emotion informs the behaviors that result (Cunningham, 1995).

Dewey also rejected Darwin’s principle that some expressions of emotions can be explained as cases where one emotion can be expressed by actions that are the exact opposite of another.

Dewey again believed that even these opposite behaviors have purposes in themselves (Cunningham, 1995).

Dewey vs. James

Dewey argued against James’s serial theory of emotions, seeing emotion and stimuli as one simultaneous coordinated act.

William James proposed a serial theory of emotion , in which an emotional experience progresses through several sequential stages:

- An object or idea functions as a stimulus

- This stimulus leads to a behavioral response

- The response is then followed by an emotional excitation or affect

An example would be seeing a bear (stimulus), running away (response), and then feeling afraid (emotion).

Dewey, however, argued that emotion and stimulus form a unified, simultaneous act that cannot be separated in this way.

He uses the example of a frightened reaction to a bear to illustrate his point:

- The “bear” itself is constituted by the coordinated sensory excitations of the eyes, touch, etc.

- The feeling of “terror” is constituted by disturbances across glandular, muscular systems.

- Rather than stimulus → response → emotion, these are partial activities within the one act of perceiving the frightening bear and running away in fear.

- The bear object and the fear emotion are two aspects of the total coordinated activity, happening at once.

So, where James treated stimulus, response, and emotion as sequential stages in an emotional episode, Dewey saw them as “minor acts” coming together in a unified conscious experience.

He maintained James was artificially separating elements that occur as part of one ongoing activity of coordination.

The key difference is that Dewey did not believe it was possible to isolate stimulus, response, and affect as self-sufficient events. They exist meaningfully only within the total act – hence why he emphasizes their simultaneity.

Backe, A. (2001). John Dewey and early Chicago functionalism. History of Psychology, 4 (4), 323.

Cunningham, S. (1995). Dewey on emotions: recent experimental evidence. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, 31(4), 865-874.

Dewey, J. (1974). John Dewey on education: Selected writings .

Göncü, A., & Rogoff, B. (1998). Children’s categorization with varying adult support. American Educational Research Journal, 35 (2), 333-349.

Hargraves, V. (2021). Dewey’s educational philosophy .

Hildebrand, D. (2018). John Dewey.

Simpson, D. J. (2006). John Dewey (Vol. 10). Peter Lang.

Turner, J. C. (2014). Theory-based interventions with middle-school teachers to support student motivation and engagement. In Motivational interventions . Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

John Dewey on education; selected writings

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

370 Previews

7 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station54.cebu on March 3, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Why John Dewey’s vision for education and democracy still resonates today

Professor of Political Science, Fordham University

Disclosure statement

Nicholas Tampio does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

John Dewey was one of the most important educational philosophers of the 20th century. His work has been cited in scholarly publications over 400,000 times . Dewey’s writings continue to influence discussions on a variety of subjects, including democratic education , which was the focus of Dewey’s famous 1916 book on the subject. In the following Q&A, Nicholas Tampio, a political science professor and editor of a forthcoming 2024 edition of Dewey’s “Democracy and Education,” explains why Dewey’s work remains relevant to this day.

Why revisit John Dewey’s philosophy on education and democracy now?

I think it is time to revisit Dewey’s philosophy about the value of field trips, classroom experiments, music instruction and children playing together on playgrounds. This is especially true after the pandemic when children spent significantly more time in front of screens rather than having whole body experiences.

Dewey’s philosophy of education was that children “learn by doing.” Dewey argued that children learn from using their entire bodies in meaningful experiences. That is why, in his 1916 text, “ Democracy and Education,” Dewey called for schools to be “equipped with laboratories, shops, and gardens.”

Dewey argued that planting seeds, measuring the relationship between Sun, soil, water and plant growth, and then tasting fresh peas made for a seamless transition between childhood curiosity and the scientific way of looking at things. Dewey also encouraged schools to create time for “ dramatizations, plays, and games .”

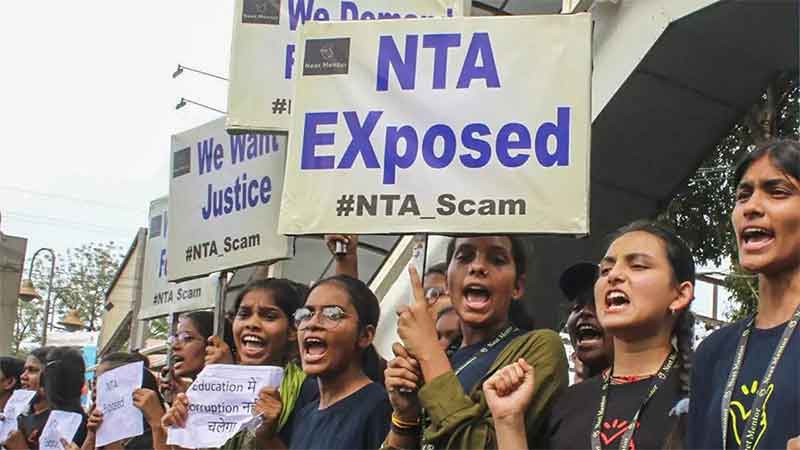

In his 2014 book, “ An Education in Politics: The Origin and Evolution of No Child Left Behind ,” the political scientist Jesse H. Rhodes shows how business groups and certain civil rights groups advocated federal laws that required states to administer high-stakes tests. This focus on tested subjects means that public school students in places such as Texas have less time for arts education.

What role did Dewey see for public schools in preserving democracy?

For Dewey, modern societies can use schools to impart democratic habits in young people from an early age. He argued that the “intermingling in the school of youth of different races, differing religions, and unlike customs creates for all a new and broader environment.” Dewey was writing as millions of European immigrants were arriving in the United States between 1900 and 1915. Dewey believed that schools could teach immigrants what it means to be a citizen and incorporate their experiences into American culture.

Dewey’s view of the schools remains relevant today. In the 2020-21 school year , more than a third of the country’s children attended schools where 75% of the student body is the same race or ethnicity – hardly the ideal conditions for Dewey’s vision of democracy.

Dewey opposed “racial, color, or other class prejudice .” Segregated schools violate Dewey’s ideal of treating all students as possessing intrinsic worth and dignity. Dewey believed that democracy means “that every human being, independent of the quantity or range of his personal endowment, has the right to equal opportunity with every other person for development of whatever gifts he has.” Democratic schools, for Dewey, empower every child to develop their gifts in ways that benefit the community.

How closely does today’s education system resemble Dewey’s vision for education?

I would argue that the education system resembles the vision of modern testing pioneers like Edward Thorndike more than Dewey’s.

Dewey thought that standardized tests serve a small role in education. He believed that “the child’s own instincts and powers furnish the material and give the starting point for all education.” Dewey maintained that teachers need to use student interest as the fuel to propel students to learn math, reading and the scientific method, and standardized tests serve mainly to help the teacher identify where each student “can receive the most help.” In his lifetime, Dewey opposed proponents of intelligence testing, such as Thorndike.

But the testing proponents seem to be winning. According to a 2023 Education Week survey of teachers, nearly 80% feel moderate or large amounts of pressure to have their students perform well on state-mandated standardized tests. According to one principal , “There’s too much pressure put on these kids for testing, and there’s too much testing.”

Dewey’s vision of education is teachers nurturing each child’s passions and not using tests to rank children. For many teachers, U.S. public schools are far from realizing that vision .

How popular are John Dewey’s views today?

Dewey’s ideas were controversial during his lifetime. They remain so to this day.

In 2023, Richard Corcoran, the president of New College of Florida, criticized “ the Dewey school of thought ” for training students to become “widget makers.” According to Corcoran, Dewey thought that “if we can teach (people) just enough skills to get on the assembly line and help us with this Industrial Revolution, everything will be great.” Corcoran is right that Dewey thought that schools should teach children about industry, including with hands-on tasks. But Dewey opposed vocational education that slotted children from a young age into a career path .

“I am utterly opposed,” Dewey explained, “to giving the power of social predestination, by means of narrow trade-training, to any group of fallible men no matter how well-intentioned they may be.” Dewey thought that children could learn about history and economics from using machinery in schools. However, he opposed a two-tiered education system that denied working-class children a well-rounded education or that equated human flourishing with making widgets.

Educators and scholars such as Diane Ravitch , Deborah Meier and Yong Zhao cite Dewey and apply his insights to current education debates. Those debates include topics such as the place of standardized testing in schools, the freedom of the classroom teacher and the need for schools to build trust with families and community members.

Zhao, for instance, argues that Dewey outlined a way to address education inequity that does not rely on closing gaps in test scores. Dewey’s idea, according to Zhao, is that all children should have a chance to express and cultivate individuality, learn through experiences and make “the most of the opportunities of present life.”

Dewey believed that “ democracy is a way of life .” He also believed schools could teach that lesson to young people by allowing people in the school to have a meaningful say in the aims of education. For many people who read Dewey today, his call for democracy in education still resonates.

- Immigration

- Public education

- K-12 education

- Immigrant students

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

Senior Lecturer, Digital Advertising

Service Delivery Fleet Coordinator

Manager, Centre Policy and Translation

Newsletter and Deputy Social Media Producer

The Pedagogy Of John Dewey: A Summary

Dewey believed that learning was socially constructed and that brain-based pedagogy should emphasize active, experiential learning.

John Dewey’s Pedagogy: A Summary

by TeachThought Staff

What did John Dewey believe about education?

What were his views on experiential and interactive learning and their role in teaching and learning?

As always, there’s a lot to understand. John Dewey (1859–1952) developed extraordinarily influential educational and social theories that had a lasting influence on psychology, pedagogy, and political philosophy, among other fields. Stanford University explained that because Dewey “typically took a genealogical approach that couched his own view within the larger history of philosophy, one may also find a fully developed metaphilosophy in his work.”

One way to think of his ideas, then, is unifying and comprehensive, gathering otherwise distinct fields and bringing them together in service of the concept of teaching children how to live better in the present rather than speculatively preparing them for a future we can’t predict.

See also 15 Self-Guided Reading Responses For Non-Fiction Texts

Major Works By John Dewey

My Pedagogic Creed (1897)

The Primary-Education Fetich (1898)

The School and Society The Child and the Curriculum Democracy and Education Schools of Tomorrow (1915)

Experience and Education (1938)

See also John Dewey Quotes About Education, Teaching, And Learning

What Did John Dewey Believe About Teaching And Learning?

What was the pedagogy of John Dewey? Put briefly, Dewey believed that learning was socially constructed, and that brain-based pedagogy (not his words) should place children, rather than curriculum and institutions, at its center. Effective learning required students to use previous (and prevailing) experiences to create new meaning–that is, to ‘learn.’

Most of Dewey’s work is characterized by his views on education itself, including its role in citizenship and democracy. But in terms of pedagogy, he is largely known for his emphasis on experiential learning, social learning, and a basic Constructivist approach to pedagogy, not to mention consistent support for the idea of self-knowledge, inquiry-based learning , and even self-directed learning, saying, “To prepare him for the future life means to give him command of himself” and considered education to be a “process of living and not a preparation for future living.”

Further, his philosophy on pedagogy would align strongly with the gradual release of responsibility model that while still in need of a ‘more knowledgeable other’ (the teacher) would create learning experiences designed to result in the autonomy and self-efficacy of a student as they master content.

What Dewey believed about ‘pedagogy’ depends on what parts of his work you want to unpack, but broadly speaking, he was a constructivist who pushed for a ‘human’ education experience that leveraged communal constructivism and the role of inquiry and curiosity in the active participation of a student in their own education.

Further, his social constructivist theories pre-date those of Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky (who are arguably more well-known for these ideas), and he lamented even around the turn of the century the problems with ‘traditional’ approaches to pedagogy that focused on institutional curriculum, instructional practices, and assessment patterns.

Wikipedia’s entry on Dewey provides a succinct overview of his work: “Dewey continually argues that education and learning are social and interactive processes, and thus the school itself is a social institution through which social reform can and should take place. In addition, he believed that students thrive in an environment where they are allowed to experience and interact with the curriculum, and all students should have the opportunity to take part in their own learning.”

“He argues that in order for education to be most effective, content must be presented in a way that allows the student to relate the information to prior experiences, thus deepening the connection with this new knowledge. In order to rectify this dilemma, Dewey advocated for an educational structure that strikes a balance between delivering knowledge while also taking into account the interests and experiences of the student. He notes that “the child and the curriculum are simply two limits which define a single process. Just as two points define a straight line, so the present standpoint of the child and the facts and truths of studies define instruction” (Dewey, 1902, p. 16). It is through this reasoning that Dewey became one of the most famous proponents of hands-on learning or experiential education….”

Education is a social process. According to the creed, it should not be used for the purposes of preparation for living in the future. Dewey said, “I believe that education, therefore, is a process of living and not a preparation for future living.” We can build a child’s self-esteem in not only the classroom but in all aspects of his or her life.”

TeachThought is an organization dedicated to innovation in education through the growth of outstanding teachers.

PHILO-notes

Free Online Learning Materials

John Dewey’s Philosophy of Education: Key Concepts

John Dewey (1859-1952) was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer who believed that education should be an active, social process that fosters creativity, problem-solving, and critical thinking. Dewey’s philosophy of education is based on the idea that learning should be relevant to students’ lives and experiences, and that students should be actively engaged in the learning process. In this essay, I will explore Dewey’s philosophy of education in depth.

Dewey believed that education is a process of growth and development that starts with the child’s interests and experiences. He argued that education should be designed to promote individual growth and social progress. Dewey saw education as a tool for social reform and believed that it could be used to promote democracy and social justice.

One of Dewey’s key contributions to educational philosophy was his idea of “progressive education.” This approach to education emphasizes student-centered learning, where students are actively engaged in the learning process and teachers act as facilitators rather than instructors. Progressive education is based on the belief that students learn best when they are actively involved in the learning process, and when they are able to connect what they are learning to their own lives and experiences.

According to Dewey, the purpose of education is to prepare students for life in a democratic society. He believed that education should promote social responsibility and that students should be taught to work collaboratively to solve problems and make decisions. Dewey saw education as a way of promoting social equality and believed that all students should have access to high-quality education, regardless of their socio-economic background.

Dewey also believed that education should be holistic and that it should address the intellectual, emotional, and social development of the student. He argued that education should help students to develop a sense of self-awareness, to understand their own emotions and motivations, and to develop empathy and understanding for others.

Another important aspect of Dewey’s philosophy of education is his emphasis on experiential learning. Dewey believed that students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning process, and when they are able to connect what they are learning to real-life experiences. He believed that education should be hands-on and that students should be encouraged to experiment and explore.

In addition to the above, it is important to note that Dewey’s philosophy of education is closely tied to his broader philosophical framework of pragmatism, which emphasizes the practical application of ideas and the importance of experience and experimentation in the pursuit of knowledge. Dewey believed that education should be geared towards helping students develop practical skills and knowledge that they can apply in their daily lives, rather than simply memorizing facts or abstract theories.

One of the key features of Dewey’s pragmatic approach to education is the idea of “learning by doing.” Dewey believed that students learn best when they are actively engaged in the learning process and when they have opportunities to apply what they have learned in real-world contexts. He argued that traditional approaches to education, which rely heavily on lectures and rote memorization, are often ineffective because they do not provide students with opportunities to engage with the material in meaningful ways.

Instead, Dewey believed that education should be focused on helping students develop problem-solving skills and the ability to think critically about the world around them. He argued that by engaging in hands-on activities and experiments, students can learn to analyze and solve real-world problems, which will be more useful to them in the long run than simply memorizing information.

Dewey also believed that education should be tied closely to the needs and interests of individual students. He argued that teachers should work with their students to develop curriculum and learning activities that are tailored to their specific needs and interests, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all approach. This approach, he believed, would help students stay engaged and motivated in the learning process, and would also help them develop a sense of ownership and investment in their education.

Another key feature of Dewey’s pragmatic approach to education is the idea of social learning. Dewey believed that students learn best when they are part of a community of learners who are working together to solve problems and explore new ideas. He argued that schools should be structured in a way that encourages collaboration and social interaction among students, and that teachers should foster a sense of community and shared purpose in their classrooms.

Overall, Dewey’s philosophy of education emphasizes the importance of practical skills, critical thinking, and social learning in the pursuit of knowledge. He believed that education should be geared towards helping students develop the tools and knowledge they need to be active and engaged participants in the world around them, rather than simply passive recipients of information. By emphasizing hands-on learning, individualized curriculum, and social interaction, Dewey believed that education could be transformed into a more effective and meaningful experience for both students and teachers.

John Dewey: Education for Democracy

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 12 September 2023

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Clifford P. Harbour 2

99 Accesses

1 Citations

John Dewey was an American educational thinker who lived during a time of great change. Dewey was trained as a philosopher and worked at major universities. But, he was active off campus and worked as a teacher, speaker, and leader for various community groups and political organizations. Dewey traveled widely and left an extensive body of philosophical writings. By the end of his life, Dewey was regarded not only as a great philosopher but as an important public intellectual. Dewey argued that education, both formal and informal, should be organized to promote individual growth and social growth. These ends were most likely to be achieved when learners worked together and focused on problems important and relevant to their lives. When educational activities and programs were organized accordingly, they had the greatest chance of supporting a progressive democracy where democratic processes and practices pervaded not just political institutions but the social and economic dimensions of life as well.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Benson, L., Harkavy, I. R., & Puckett, J. L. (2007). Dewey’s dream: Universities and democracies in an age of education reform: Civil society, public schools, and democratic citizenship . Temple University Press.

Google Scholar

Boisvert, R. D. (1998). John Dewey: Rethinking our time . State University of New York Press.

Brent, J. (1998). Charles Sanders Peirce: A life . Indiana University Press.

Campbell, J. (1995). Understanding John Dewey . Open Court Publishing Company.

Commager, H. S. (1950). The American mind: An interpretation of American thought and character since the 1880s . Yale University Press.

Dewey, J. (2008a). Democracy and education. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1899–1924, Volume 9 Democracy and education 1916 . Southern Illinois University Press. (pp. vii–402) (Original work published 1916).

Dewey, J. (2008b). Emerson – The philosopher of democracy. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1899–1924, Volume 3: 1903–1906, Essays (pp. 184–192). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1903).

Dewey, J. (2008c). Human nature and conduct. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1899–1924. Volume 14: 1922, Human nature and conduct (pp. 3–233). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1922).

Dewey, J. (2008d). Individualism, old and new. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The later works of John Dewey, 1925–1953, Volume 5: 1929–1930, Essays, The sources of a science education, individualism, old and new, and construction and criticism (pp. 43–123). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1930).

Dewey, J. (2008e). Logic: The theory of inquiry. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The later works of John Dewey, 1925–1953. Volume 12: 1938, Logic: The theory of inquiry (pp. 3–527). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1938).

Dewey, J. (2008f). From absolutism to experimentalism. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The later works of John Dewey, 1925–1953, Volume 5: 1929–1930, Essays, The sources of a science education, individualism, old and new, and construction and criticism (pp. 147–160). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1930).

Dewey, J. (2008g). The influence of Darwinism on philosophy. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1899–1924. Volume 4: 1907–1909, Essays, Moral principles in education (pp. 3–14). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1909).

Dewey, J. (2008h). Cut-and-try school methods. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1889–1924, Volume 7: Essays, Interest and effort in education (pp. 691–692). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1913).

Dewey, J. (2008i). American education and culture. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1899–1924, Volume 10: 1916–1917, Essays (pp. 196–201). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1916).

Dewey, J. (2008j). Individuality, equality and superiority. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The middle works of John Dewey, 1889–1924, Volume 13: 1921–1922, Essays (pp. 295–300). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1922).

Dewey, J. (2008k). Experience and education. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The later works of John Dewey, 1938–1939, Volume 13: Experience and education, freedom and culture, theory of valuation, and essays (pp. 1–62). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1938).

Dewey, J. (2008l). The public and its problems. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), The later works of John Dewey, 1925–1953, Volume 2 Essays, The public and its problems 1925–1927 (pp. 235–372). Southern Illinois University Press. (Original work published 1927).

Dykhuizen, G. (1973). The life and mind of John Dewey . Southern Illinois University Press.

Fesmire, S. (2003). John Dewey and moral imagination: Pragmatism in ethics . Indiana University Press.

Garrison, J., Neubert, S., & Reich, K. (2016). Democracy and education reconsidered. Dewey after one hundred years . Routledge.

Hansen, D. T. (2006). Dewey’s book of the moral self. In D. T. Hansen (Ed.), John Dewey and our educational prospect: A critical engagement with Dewey’s Democracy and Education (pp. 165–187). State University of New York Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Harbour, C. P. (2015). John Dewey and the future of community college education . Bloomsbury.

Book Google Scholar

Hildebrand, D. L. (2016). The paramount importance of experience and situations in Dewey’s Democracy and Education. Educational Theory, 66 (1–2), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12153

Article Google Scholar

James, W. (2000). Pragmatism and other writings . Penguin.

Knight, L.W. (2005). Citizen: Jane addams and the struggle for democracy . University of Chicago Press.

Martin, J. (2003). The education of John Dewey: A biography . Columbia University Press.

New York Times. (1952, June 2). Dr. John Dewey dead at 92; Philosopher a noted liberal . (pp. 1 & 21). New York Times.

Pappas, G. (2008). John Dewey’s ethics: Democracy as experience . Indiana University Press.

Phillips, D. C. (2016). A companion to John Dewey’s Democracy and Education . University of Chicago Press.

Phillips, D. C. (2022). Can public common schooling save the Republic? In D. C. Berliner & C. Hermanns (Eds.), Public education: Defending a cornerstone of American democracy (pp. 246–256). Teachers College Press.

Putnam, H., & Putnam, R. A. (2017). Pragmatism as a way of life: The lasting legacy of William James and John Dewey . Harvard University Press.

Richardson, R. D. (1996). Emerson: The mind on fire . University of California Press.

Richardson, R. D. (2007). William James: In the maelstrom of American modernism . Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Rockefeller, S. (1994). John Dewey: Religious faith and democratic humanism . Columbia University Press.

Rogers, M. L. (2009). The undiscovered Dewey: Religion, morality, and the ethos of democracy . Columbia University Press.

Roosevelt, A., & Dobbs, Z. (1964). The great deceit . Veritas Foundation.

Rorty, R. (1979). Philosophy and the mirror of nature . Princeton University Press.

Russell, B. (1967). Philosophical essays . Simon & Schuster.

Ryan, A. (1995). John Dewey and the high tide of American Liberalism . Norton.

Waks, L. J. (2020). Chapter 19: Dewey and higher education. In S. Fesmire (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Dewey (pp. 393–410). Oxford University Press.

Waks, L. J., & English, A. R. (Eds.). (2017). John Dewey’s Democracy and Education: A centennial handbook . Cambridge University Press.

West, C. (1989). The American evasion of philosophy: A genealogy of pragmatism . University of Wisconsin Press.

Westbrook, R. B. (1991). John Dewey and American democracy . Cornell University Press.

Further Reading

Fesmire, S. (Ed.). (2019). The Oxford handbook of Dewey . Oxford University Press.

Hickman, L. A., & Alexander, T. M. (Eds.). (1998). The essential Dewey, Volume 1: Pragmatism, education, democracy . Indiana University Press.

Hickman, L. A., & Alexander, T. M. (Eds.). (2009). The Essential Dewey: Volume 2: Ethics, logic, psychology . Indiana University Press.

Hook, S. (2008). John Dewey: An intellectual portrait . Cosimo Inc. (Original work published 1939).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Counseling and Higher Education Department, University of North Texas, Denton, TX, USA

Clifford P. Harbour

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Clifford P. Harbour .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Educational Leadership, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA

Brett A. Geier

Section Editor information

New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA

Azadeh F. Osanloo Professor

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Harbour, C.P. (2023). John Dewey: Education for Democracy. In: Geier, B.A. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Thinkers . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81037-5_85-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81037-5_85-1

Received : 14 May 2023

Accepted : 30 June 2023

Published : 12 September 2023

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-81037-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-81037-5

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

16 minute read

John Dewey (1859–1952)

Experience and reflective thinking, learning, school and life, democracy and education.

Throughout the United States and the world at large, the name of John Dewey has become synonymous with the Progressive education movement. Dewey has been generally recognized as the most renowned and influential American philosopher of education.

He was born in 1859 in Burlington, Vermont, and he died in New York City in 1952. During his lifetime the United States developed from a simple frontier-agricultural society to a complex urban-industrial nation, and Dewey developed his educational ideas largely in response to this rapid and wrenching period of cultural change. His father, whose ancestors came to America in 1630, was the proprietor of Burlington's general store, and his mother was the daughter of a local judge. John, the third of their four sons, was a shy boy and an average student. He delivered newspapers, did his chores, and enjoyed exploring the woodlands and waterways around Burlington. His father hoped that John might become a mechanic, and it is quite possible that John might not have gone to college if the University of Vermont had not been located just down the street. There, after two years of average work, he graduated first in a class of 18 in 1879.

There were few jobs for college graduates in Burlington, and Dewey spent three anxious months searching for work. Finally, a cousin who was the principal of a high school in South Oil City, Pennsylvania, offered him a teaching position which paid $40 a month. After two years of teaching high school Latin, algebra, and science, Dewey returned to Burlington to teach in a rural school closer to home.

With the encouragement of H. A. P. Torrey, his former philosophy professor at the University of Vermont, Dewey wrote three philosophical essays (1882a; 1882b; 1883) which were accepted for publication in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, whose editor, William Torrey Harris, hailed them as the products of a first-rate philosophical mind. With this taste of success and a $500 loan from his aunt, Dewey left teaching to do graduate work at Johns Hopkins University. There he studied philosophy–which at that time and place primarily meant Hegelian philosophy and German idealism–and wrote his dissertation on the psychology of Kant.

After he received the doctorate in 1884, Dewey was offered a $900-a-year instructorship in philosophy and psychology at the University of Michigan. In his first year at Michigan, Dewey not only taught but also produced his first major book, Psychology (1887). In addition, he met, wooed, and married Alice Chipman, a student at Michigan who was herself a former schoolteacher. Fatherhood and ten years' teaching experience helped his interest in psychology and philosophy to merge with his growing interest in education.

In 1894 the University of Chicago offered Dewey the chairmanship of the department of philosophy, psychology, and pedagogy. At Chicago he established the now-famous laboratory school (commonly known as the Dewey School), where he scientifically tested, modified, and developed his psychological and educational ideas.

An early statement of his philosophical position in education, My Pedagogic Creed (1897), appeared three years after his arrival at Chicago. Four other major educational writings came out of Dewey's Chicago experience. The first two, The School and Society (1956), which was first published in 1899, and The Child and the Curriculum (1902), were lectures which he delivered to raise money and gain support for the laboratory school. Although the books were brief, they were clear and direct statements of the basic elements of Dewey's educational philosophy and his psychology of learning. Both works stressed the functional relationship between classroom learning activities and real life experiences and analyzed the social and psychological nature of the learning process. Two later volumes, How We Think (1910) and Democracy and Education (1916), elaborated these themes in greater and more systematic detail.

Dewey's work at Chicago was cut short when, without consulting Dewey, Chicago's president, William Rainey Harper, arranged to merge the laboratory school with the university training school for teachers. The merger not only took control of the school from Dewey's hands but changed it from an experimental laboratory to an institution for teacher-training. Dewey felt that he had no recourse but to resign and wrote to William James at Harvard and to James M. Cattell at Columbia University, informing them of his decision. Dewey's reputation in philosophy had grown considerably by this time, and Cattell had little difficulty in persuading the department of philosophy and psychology at Columbia to offer him a position. Because the salary offer was quite low for a man with six children (three more had been born during his ten years at Chicago), arrangements were made for Dewey to teach an additional two hours a week at Columbia Teachers College for extra compensation. For the next twenty-six years at Columbia, Dewey continued his illustrious career as a philosopher and witnessed the dispersion of his educational ideas throughout the world by many of his disciples at Teachers College, not the least of whom was William Heard Kilpatrick.

Dewey retired in 1930 but was immediately appointed professor emeritus of philosophy in residence at Columbia and held that post until his eightieth birthday in 1939. The previous year he had published his last major educational work, Experience and Education (1938). In this series of lectures he clearly restated his basic philosophy of education and recognized and rebuked the many excesses he thought the Progressive education movement had committed. He chastised the Progressives for casting out traditional educational practices and content without offering something positive and worthwhile to take their place. He offered a reformulation of his views on the intimate connection between learning and experience and challenged those who would call themselves Progressives to work toward the realization of the educational program he had carefully outlined a generation before.

At the age of ninety he published his last large-scale original philosophical work, Knowing andthe Known (1949), in collaboration with Arthur F. Bentley.

Experience and Reflective Thinking

The starting place in Dewey's philosophy and educational theory is the world of everyday life. Unlike many philosophers, Dewey did not search beyond the realm of ordinary experience to find some more fundamental and enduring reality. For Dewey, the everyday world of common experience was all the reality that man had access to or needed. Dewey was greatly impressed with the success of the physical sciences in solving practical problems and in explaining, predicting, and controlling man's environment. He considered the scientific mode of inquiry and the scientific systematization of human experience the highest attainment in the evolution of the mind of man, and this way of thinking and approaching the world became a major feature of his philosophy. In fact, he defined the educational process as a "continual reorganization, reconstruction and transformation of experience" (1916, p. 50), for he believed that it is only through experience that man learns about the world and only by the use of his experience that man can maintain and better himself in the world.

Dewey was careful in his writings to make clear what kinds of experiences were most valuable and useful. Some experiences are merely passive affairs, pleasant or painful but not educative. An educative experience, according to Dewey, is an experience in which we make a connection between what we do to things and what happens to them or us in consequence; the value of an experience lies in the perception of relationships or continuities among events. Thus, if a child reaches for a candle flame and burns his hand, he experiences pain, but this is not an educative experience unless he realizes that touching the flame resulted in a burn and, moreover, formulates the general expectation that flames will produce burns if touched. In just this way, before we are formally instructed, we learn much about the world, ourselves, and others. It is this natural form of learning from experience, by doing and then reflecting on what happened, which Dewey made central in his approach to schooling.

Reflective thinking and the perception of relationships arise only in problematical situations. As long as our interaction with our environment is a fairly smooth affair we may think of nothing or merely daydream, but when this untroubled state of affairs is disrupted we have a problem which must be solved before the untroubled state can be restored. For example, a man walking in a forest is suddenly stopped short by a stream which blocks his path, and his desire to continue walking in the same direction is thwarted. He considers possible solutions to his problem–finding or producing a set of stepping-stones, finding and jumping across a narrow part, using something to bridge the stream, and so forth–and looks for materials or conditions to fit one of the proposed solutions. He finds an abundance of stones in the area and decides that the first suggestion is most worth testing. Then he places the stones in the water, steps across to the other side, and is off again on his hike. Such an example illustrates all the elements of Dewey's theoretical description of reflective thinking: A real problem arises out of present experiences, suggestions for a solution come to mind, relevant data are observed, and a hypothesis is formed, acted upon, and finally tested.

For Dewey, learning was primarily an activity which arises from the personal experience of grappling with a problem. This concept of learning implied a theory of education far different from the dominant school practice of his day, when students passively received information that had been packaged and predigested by teachers and textbooks. Thus, Dewey argued, the schools did not provide genuine learning experiences but only an endless amassing of facts, which were fed to the students, who gave them back and soon forgot them.

Dewey distinguished between the psychological and the logical organization of subject matter by comparing the learner to an explorer who maps an unknown territory. The explorer, like the learner, does not know what terrain and adventures his journey holds in store for him. He has yet to discover mountains, deserts, and water holes and to suffer fever, starvation, and other hardships. Finally, when the explorer returns from his journey, he will have a hard-won knowledge of the country he has traversed. Then, and only then, can he produce a map of the region. The map, like a textbook, is an abstraction which omits his thirst, his courage, his despairs and triumphs–the experiences which made his journey personally meaningful. The map records only the relationships between landmarks and terrain, the logic of the features without the psychological revelations of the journey itself.

To give the map to others (as a teacher might) is to give the results of an experience, not the experience by which the map was produced and became personally meaningful to the producer. Although the logical organization of subject matter is the proper goal of learning, the logic of the subject cannot be truly meaningful to the learner without his psychological and personal involvement in exploration. Only by wrestling with the conditions of the problem at hand, "seeking and finding his own way out, does he think …. If he cannot devise his own solution (not, of course, in isolation but in correspondence with the teacher and other pupils) and find his own way out he will not learn, not even if he can recite some correct answer with one hundred percent accuracy" (Dewey 1916, p. 160).

Although learning experiences may be described in isolation, education for Dewey consisted in the cumulative and unending acquisition, combination, and reordering of such experiences. Just as a tree does not grow by having new branches and leaves wired to it each spring, so educational growth does not consist in mechanically adding information, skills, or even educative experiences to students in grade after grade. Rather, educational growth consists in combining past experiences with present experiences in order to receive and understand future experiences. To grow, the individual must continually reorganize and reformulate past experiences in the light of new experiences in a cohesive fashion.

School and Life

Ideas and experiences which are not woven into the fabric of growing experience and knowledge but remain isolated seemed to Dewey a waste of precious natural resources. The dichotomy of in-school and out-of-school experiences he considered especially wasteful, as he indicated as early as 1899 in The School and Society:

From the standpoint of the child, the great waste in the school comes from his inability to utilize the experiences he gets outside the school in any complete and free way within the school itself; while on the other hand, he is unable to apply in daily life what he is learning in school. That is the isolation of the school–its isolation from life. When the child gets into the schoolroom he has to put out of his mind a large part of the ideas, interests and activities that predominate in his home and neighborhood. So the school being unable to utilize this everyday experience, sets painfully to work on another tack and by a variety of [artificial] means, to arouse in the child an interest in school studies …. [Thus there remains a] gapexisting between the everyday experiences of the child and the isolated material supplied in such large measure in the school. (1956, pp. 75–76)

To bridge this chasm between school and life, Dewey advocated a method of teaching which began with the everyday experience of the child. Dewey maintained that unless the initial connection was made between school activities and the life experiences of the child, genuine learning and growth would be impossible. Nevertheless, he was careful to point out that while the experiential familiar was the natural and meaningful place to begin learning, it was more importantly the "intellectual starting point for moving out into the unknown and not an end in itself" (1916, p. 212).

To further reduce the distance between school and life, Dewey urged that the school be made into an embryonic social community which simplified but resembled the social life of the community at large. A society, he reasoned, "is a number of people held together because they are working along common lines, in a common spirit, and with reference to common aims. The common needs and aims demand a growing interchange of thought and growing unity of sympathetic feeling." The tragic weakness of the schools of his time was that they were endeavoring "to prepare future members of the social order in a medium in which the conditions of the social spirit [were] eminently wanting" (1956, pp. 14–15).

Thus Dewey affirmed his fundamental belief in the two-sidedness of the educational process. Neither the psychological nor the sociological purpose of education could be neglected if evil results were not to follow. To isolate the school from life was to cut students off from the psychological ties which make learning meaningful; not to provide a school environment which prepared students for life in society was to waste the resources of the school as a socializing institution.

Democracy and Education

Dewey recognized that the major instrument of human learning is language, which is itself a social product and is learned through social experiences. He saw that in providing a pool of common meanings for communication, the language of each society becomes the repository of the society's ideals, values, beliefs, and accumulated knowledge. To transmit the contents of the language to the young and to initiate the young in the ways of civilized life was for Dewey the primary function of the school as an institution of society. But, he argued, a way of life cannot be transmitted by words alone. Essential to acquiring the spirit of a way of life is immersion in ways of living.

More specifically, Dewey thought that in a democratic society the school should provide students with the opportunity to experience democracy in action. For Dewey, democracy was more than a form of government; it was a way of living which went beyond politics, votes, and laws to pervade all aspects of society. Dewey recognized that every social group, even a band of thieves, is held together by certain common interests, goals, values, and meanings, and he knew that every such group also comes into contact with other groups. He believed, however, that the extent to which democracy has been attained in any society can be measured by the extent to which differing groups share similar values, goals, and interests and interact freely and fruitfully with each other.

A democratic society, therefore, is one in which barriers of any kind–class, race, religion, color, politics, or nationality–among groups are minimized, and numerous meanings, values, interests, and goals are held in common. In a democracy, according to Dewey, the schools must act to ensure that each individual gets an opportunity to escape from the limitations of the social group in which he was born, to come into contact with a broader environment, and to be freed from the effects of economic inequalities. The schools must also provide an environment in which individuals may share in determining and achieving their common purposes in learning so that in contact with each other the students may recognize their common humanity: "The emphasis must be put upon whatever binds people together in cooperative human pursuits … and the fuller, freer, intercourse of all human beings with one another …. [This] ideal may seem remote of execution, but the democratic ideal of education is a farcical yet tragic delusion except as the ideal more and more dominates our public system of education" (Dewey, 1916, p. 98).

Dewey's belief in democracy and in the schools' ability to provide a staging platform for social progress pervades all his work but is perhaps most clearly stated in his early Pedagogic Creed:

I believe that education is the fundamental method of social progress and reform. All reforms which rest simply upon the enactment of law, or the threatening of certain penalties, or upon changes in mechanical or outward arrangements, are transitory and futile …. By law and punishment, by social agitation and discussion, society can regulateand form itself in a more or less haphazard and chance way. But through education society can formulate its own purposes, can organize its own means and resources, and thus shape itself with definiteness and economy in the direction in which it wishes to move …. Educationthus conceived marks the most perfect and intimate union of science and art conceivable in human experience. (1964, pp. 437–438)

Perhaps it was with these ideas in mind that Dewey was prompted to equate education with philosophy, for he felt that a deep knowledge of man and nature was not only the proper goal of education but the eternal quest of the philosopher: "If we are willing to conceive of education as the process of forming fundamental dispositions, intellectual and emotional, toward nature and fellow men, philosophy may even be defined as the general theory of education" (1916, p. 328).

See also: P ROGRESSIVE E DUCATION .

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A RCHAMBAULT , R EGINALD D., ed. 1964. John Dewey on Education. New York: Modern Library.

A RCHAMBAULT , R EGINALD D., ed. 1966. Dewey on Education: Appraisals of Dewey's Influence on American Education. New York: Random House.

C REMIN , L AWRENCE A. 1961. The Transformation of the School: Progressivism in American Education, 1876–1957. New York: Knopf.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1882a. "The Metaphysical Assumptions of Materialism." Journal of Speculative Philosophy 16:208–213.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1882b. "The Pantheism of Spinoza." Journal of Speculative Philosophy 16:249–257.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1883. "Knowledge and the Relativity of Feeling." Journal of Speculative Philosophy 17:56–70.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1887. Psychology. New York: Harper. D EWEY , J OHN . 1902. The Child and the Curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1929. My Pedagogic Creed (1897). Washington, DC: Progressive Education Association.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1933. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process (1910), revised edition. Boston: Heath.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1938. Experience and Education. New York: Macmillan.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1961. Democracy and Education (1916). New York: Macmillan.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1956. The Child and the Curriculum and The School and Society. Chicago: Phoenix.

D EWEY , J OHN . 1960. "From Absolutism to Experimentalism." On Experience, Nature, and Freedom. Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill.

D EWEY , J OHN , and B ENTLEY , A RTHUR F. 1949. Knowing and the Known. Boston: Beacon.

T HOMAS , M ILTON H. 1962. John Dewey: A Centennial Bibliography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

J ONAS F. S OLTIS

Additional topics

- Discourse - CLASSROOM DISCOURSE, COGNITIVE PERSPECTIVE

- Developmental Theory - Cognitive And Information Processing, Evolutionary Approach, Vygotskian Theory - HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Education - Free Encyclopedia Search Engine Education Encyclopedia: Education Reform - OVERVIEW to Correspondence course

Although his name isn’t well known, John Dewey had a deep impact on American thought. He was the last of the great classical pragmatists , the generation of thinkers who developed a distinctly American school of thought rooted in practicality and personal commitment. Appropriately for a philosophical pragmatist, Dewey brought his ideas to the public in an effort to reform American society. He helped establish the anti-racist NAACP in 1910, advocated vigorously for academic freedom, and practical education. Where many countries (then and now) focused their education on rote learning and memorization, Dewey argued that democratic culture required free-thinking citizens and therefore rejected the idea of memorization-based learning.

Born in 1859, Dewey lived until 1952, and so witnessed a profound period of transformation in America. He saw the Civil War, the end of slavery, the rise of industrial inventions like cars and airplanes, then two world wars and the beginnings of the Civil Rights movement. In part thanks to these experiences, his works show a deep understanding of American culture and an equally deep faith in the democratic practices that will, Dewey hopes, continue to improve that culture and pull it into the future.

Dewey was born to a middle-class Vermont family and began his career as a primary school teacher. He never lost his passion for education, but he found that teaching young children did not satisfy his need for intellectual stimulation. He wanted to think philosophically about the goals and practices of education without the distraction of day-to-day classroom management. Scraping together funds, he enrolled in a Ph.D. program at Johns Hopkins University, where he studied Kantian philosophy. After finishing his degree, he was offered an appointment at the University of Chicago, where he continued to publish philosophical essays on logic.

At the same time, he put his philosophy into practice by establishing the University of Chicago Laboratory School, an experimental private school where he could test his ideas on education. It’s a testament to the success of those ideas that the Lab School is today one of the country’s most highly-regarded private schools (ranked 4 th in the nation by the Wall Street Journal). After moving to New York in 1904, Dewey continued his advocacy and reform work. He helped establish the New School, an experimental college that boasts among its alumni major thinkers and artists such as Jack Kerouack, Hannah Arendt, and Ai Weiwei.

Dewey’s Ideas

Dewey wasn’t the inventor of pragmatism , but he was one of a group of philosophers who brought it to prominence. The idea emerged simultaneously from several corners of American intellectual life: from C.S. Peirce and William James at Harvard; Oliver Wendell Holmes at the Supreme Court; and John Dewey at Chicago. In their philosophical and legal writings, all four shared an emphasis on concrete practices over abstract principles. Holmes, for example, argued that judges should take into account the practical consequences of their rulings and not simply adhere dogmatically to abstract principles. Laws are not eternal philosophical truths (if such things even exist) but attempts by people in a particular cultural context to fix particular problems. To apply the law correctly, then, we need to understand how that context and those problems relate to our own.

Similarly, Peirce and James wrote about the importance of practical considerations in considering philosophical propositions. The value of a philosophical proposition, James argued, was its power to affect human behavior. Consider two people with slightly different beliefs about God. If they act the same way, make the same statements, pray the same prayers, and enact the same rituals, then are they really different beliefs at all? James argued that it didn’t make sense to view beliefs as different merely because they have different psychological representations; it’s the effect on behavior that counts.

Dewey took this idea forward in his writings on politics and education. He argued that one of the goals of philosophy was to bolster democratic culture, empowering both reader and writer to further the democratic project. In everything he wrote, his goal was pragmatic: to help craft an understanding of the universe that would be conducive to freedom and equality. Specifically, Dewey argues that modern education needs to dismantle the old dualisms of the past: mind vs. body, culture vs. nature, individual vs. collective, etc. He sees all these dualisms as oversimplifications. In reality what we see are dynamic relationships in which both sides simultaneously support and challenge each other. The mind, for example, is not separate from the body but part of the body. A hungry and sleep-deprived person, for example, will have less mental capacity than one who is well fed and well rested. The body creates the mind. At the same time, mental practices contribute to physical health: think of the placebo effect or the well-known benefits of meditation. Mind and body are one, as are the other sides of the old dualisms. In order to have a functioning democratic society, Dewey argues, we have to help people get past these dualisms.

Accidental inequalities of birth, wealth, and learning are always tending to restrict the opportunities of some as compared with those of others. Only free and continued education can counteract those forces which are always at work to restore, in however changed a form, feudal oligarchy. Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.

Here Dewey sums up a central theme in his writing: the connection between democracy and education. He sees democracy as a fragile project, perpetually in danger of sliding into oligarchy or plutocracy (the absolute rule of the wealthy and powerful). The only way to avoid that fate is to educate each generation so that they are capable of carrying democracy forward. They must learn to think independently, must learn enough history that they can critically evaluate their own place in it, and must learn science so that they can understand their place in the universe and the technologies at work in their society. Education, in other words, isn’t about training individuals to succeed in the economy of a given moment; it’s about training them to uphold the social fabric on which that economy is founded.

In Pop Culture

There’s an episode of The Boondocks where Riley meets an art teacher. In many ways, the art teacher is based on Bob Ross, but there’s a little of John Dewey’s spirit in him as well. Rather than teach Riley mere artistic technique or have him memorize art history, the teacher tries to help Riley cultivate values of positive self-expression that make his street art uplifting and valuable for his community. It’s an idea that resonates with pragmatism: using education as a means to help the student prepare for participation in democratic society. He also helps Riley overcome the socially-constructed dualism between art and vandalism, proving that Riley can make street art that’s just as valuable as any piece hanging in a museum. The art teacher also ends up in a shoot-out with the police, which would have been a little too radical for John Dewey.

a. The value of a philosophical idea was defined by its practical implications

b. The point of education is to support democratic institutions

c. There is no dualism between mind and body

d. All of the above

a. Aristotelianism

b. Empiricism

c. Rationalism

d. Pragmatism

a. The NAACP

b. Harvard University

c. The American Psychological Association

a. The needs of the individual are always in tension with the demands of society

b. The value of a school can be judged by how much money its graduates make

c. Without constant human effort, democracy will always collapse

d. Dewey would have agreed with all of these

John Dewey in the 21st Century: Philosopher and Educational Reformer

“Education is not preparation for life, education is life itself”- John Dewey

John Dewey was an American Philosopher and educator, founder of the philosophical movement known as Pragmatism, a pioneer of functional psychology and a leader of the progressive movement in education in United States. Dewey’s authority on education was evident in his theory about social learning; he believed that school should be representative of a social environment and that students learn best when in natural social settings (Flinders & Thornton, 2013). His ideas impacted education in another facet because he believed that students were all unique learners. He was a advocate of student interests driving teacher instruction (Dewey, 1938). With the current educational focus in the United States being on the implementation of the Common Core standards and passing standardized tests and state exams, finding evidence of John Dewey’s theories in classrooms today can be problematic (Theobald, 2009). Education in most classrooms today is what Dewey would have described as a traditional classroom setting. He believed that traditional classroom settings were not developmentally appropriate for young learners (Dewey, 1938). Although schools, classrooms, and programs that support Dewey’s theories are harder to find in this era of testing, there are some that still do exist. This paper will explore Responsive Classroom, Montessori Schools, Place-Based Education, and Philosophy for Children (P4C), all of which incorporate the theories of John Dewey into their curricular concepts.