- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Studies Review

- About the International Studies Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, what is fieldwork, purpose of fieldwork, physical safety, mental wellbeing and affect, ethical considerations, remote fieldwork, concluding thoughts, acknowledgments, funder information.

- < Previous

Field Research: A Graduate Student's Guide

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ezgi Irgil, Anne-Kathrin Kreft, Myunghee Lee, Charmaine N Willis, Kelebogile Zvobgo, Field Research: A Graduate Student's Guide, International Studies Review , Volume 23, Issue 4, December 2021, Pages 1495–1517, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab023

- Permissions Icon Permissions

What is field research? Is it just for qualitative scholars? Must it be done in a foreign country? How much time in the field is “enough”? A lack of disciplinary consensus on what constitutes “field research” or “fieldwork” has left graduate students in political science underinformed and thus underequipped to leverage site-intensive research to address issues of interest and urgency across the subfields. Uneven training in Ph.D. programs has also left early-career researchers underprepared for the logistics of fieldwork, from developing networks and effective sampling strategies to building respondents’ trust, and related issues of funding, physical safety, mental health, research ethics, and crisis response. Based on the experience of five junior scholars, this paper offers answers to questions that graduate students puzzle over, often without the benefit of others’ “lessons learned.” This practical guide engages theory and praxis, in support of an epistemologically and methodologically pluralistic discipline.

¿Qué es la investigación de campo? ¿Es solo para académicos cualitativos? ¿Debe realizarse en un país extranjero? ¿Cuánto tiempo en el terreno es “suficiente”? La falta de consenso disciplinario con respecto a qué constituye la “investigación de campo” o el “trabajo de campo” ha causado que los estudiantes de posgrado en ciencias políticas estén poco informados y, por lo tanto, capacitados de manera insuficiente para aprovechar la investigación exhaustiva en el sitio con el objetivo de abordar los asuntos urgentes y de interés en los subcampos. La capacitación desigual en los programas de doctorado también ha provocado que los investigadores en las primeras etapas de su carrera estén poco preparados para la logística del trabajo de campo, desde desarrollar redes y estrategias de muestreo efectivas hasta generar la confianza de las personas que facilitan la información, y las cuestiones relacionadas con la financiación, la seguridad física, la salud mental, la ética de la investigación y la respuesta a las situaciones de crisis. Con base en la experiencia de cinco académicos novatos, este artículo ofrece respuestas a las preguntas que desconciertan a los estudiantes de posgrado, a menudo, sin el beneficio de las “lecciones aprendidas” de otras personas. Esta guía práctica incluye teoría y praxis, en apoyo de una disciplina pluralista desde el punto de vista epistemológico y metodológico.

En quoi consiste la recherche de terain ? Est-elle uniquement réservée aux chercheurs qualitatifs ? Doit-elle être effectuée dans un pays étranger ? Combien de temps faut-il passer sur le terrain pour que ce soit « suffisant » ? Le manque de consensus disciplinaire sur ce qui constitue une « recherche de terrain » ou un « travail de terrain » a laissé les étudiants diplômés en sciences politiques sous-informés et donc sous-équipés pour tirer parti des recherches de terrain intensives afin d'aborder les questions d'intérêt et d'urgence dans les sous-domaines. L'inégalité de formation des programmes de doctorat a mené à une préparation insuffisante des chercheurs en début de carrière à la logistique du travail de terrain, qu'il s'agisse du développement de réseaux et de stratégies d’échantillonnage efficaces, de l'acquisition de la confiance des personnes interrogées ou des questions de financement, de sécurité physique, de santé mentale, d’éthique de recherche et de réponse aux crises qui y sont associées. Cet article s'appuie sur l'expérience de cinq jeunes chercheurs pour proposer des réponses aux questions que les étudiants diplômés se posent, souvent sans bénéficier des « enseignements tirés » par les autres. Ce guide pratique engage théorie et pratique en soutien à une discipline épistémologiquement et méthodologiquement pluraliste.

Days before embarking on her first field research trip, a Ph.D. student worries about whether she will be able to collect the qualitative data that she needs for her dissertation. Despite sending dozens of emails, she has received only a handful of responses to her interview requests. She wonders if she will be able to gain more traction in-country. Meanwhile, in the midst of drafting her thesis proposal, an M.A. student speculates about the feasibility of his project, given a modest budget. Thousands of miles away from home, a postdoc is concerned about their safety, as protests erupt outside their window and state security forces descend into the streets.

These anecdotes provide a small glimpse into the concerns of early-career researchers undertaking significant projects with a field research component. Many of these fieldwork-related concerns arise from an unfortunate shortage in curricular offerings for qualitative and mixed-method research in political science graduate programs ( Emmons and Moravcsik 2020 ), 1 as well as the scarcity of instructional materials for qualitative and mixed-method research, relative to those available for quantitative research ( Elman, Kapiszewski, and Kirilova 2015 ; Kapiszewski, MacLean, and Read 2015 ; Mosley 2013 ). A recent survey among the leading United States Political Science programs in Comparative Politics and International Relations found that among graduate students who have carried out international fieldwork, 62 percent had not received any formal fieldwork training and only 20 percent felt very or mostly prepared for their fieldwork ( Schwartz and Cronin-Furman 2020 , 7–8). This shortfall in training and instruction means that many young researchers are underprepared for the logistics of fieldwork, from developing networks and effective sampling strategies to building respondents’ trust. In addition, there is a notable lack of preparation around issues of funding, physical safety, mental health, research ethics, and crisis response. This is troubling, as field research is highly valued and, in some parts of the field, it is all but expected, for instance in comparative politics.

Beyond subfield-specific expectations, research that leverages multiple types of data and methods, including fieldwork, is one of the ways that scholars throughout the discipline can more fully answer questions of interest and urgency. Indeed, multimethod work, a critical means by which scholars can parse and evaluate causal pathways, is on the rise ( Weller and Barnes 2016 ). The growing appearance of multimethod research in leading journals and university presses makes adequate training and preparation all the more significant ( Seawright 2016 ; Nexon 2019 ).

We are five political scientists interested in providing graduate students and other early-career researchers helpful resources for field research that we lacked when we first began our work. Each of us has recently completed or will soon complete a Ph.D. at a United States or Swedish university, though we come from many different national backgrounds. We have conducted field research in our home countries and abroad. From Colombia and Guatemala to the United States, from Europe to Turkey, and throughout East and Southeast Asia, we have spanned the globe to investigate civil society activism and transitional justice in post-violence societies, conflict-related sexual violence, social movements, authoritarianism and contentious politics, and the everyday politics and interactions between refugees and host-country citizens.

While some of us have studied in departments that offer strong training in field research methods, most of us have had to self-teach, learning through trial and error. Some of us have also been fortunate to participate in short courses and workshops hosted by universities such as the Consortium for Qualitative Research Methods and interdisciplinary institutions such as the Peace Research Institute Oslo. Recognizing that these opportunities are not available to or feasible for all, and hoping to ease the concerns of our more junior colleagues, we decided to compile our experiences and recommendations for first-time field researchers.

Our experiences in the field differ in several key respects, from the time we spent in the field to the locations we visited, and how we conducted our research. The diversity of our experiences, we hope, will help us reach and assist the broadest possible swath of graduate students interested in field research. Some of us have spent as little as ten days in a given country or as much as several months, in some instances visiting a given field site location just once and in other instances returning several times. At times, we have been able to plan weeks and months in advance. Other times, we have quickly arranged focus groups and impromptu interviews. Other times still, we have completed interviews virtually, when research participants were in remote locations or when we ourselves were unable to travel, of note during the coronavirus pandemic. We have worked in countries where we are fluent or have professional proficiency in the language, and in countries where we have relied on interpreters. We have worked in settings with precarious security as well as in locations that feel as comfortable as home. Our guide is not intended to be prescriptive or exhaustive. What we offer is a set of experience-based suggestions to be implemented as deemed relevant and appropriate by the researcher and their advisor(s).

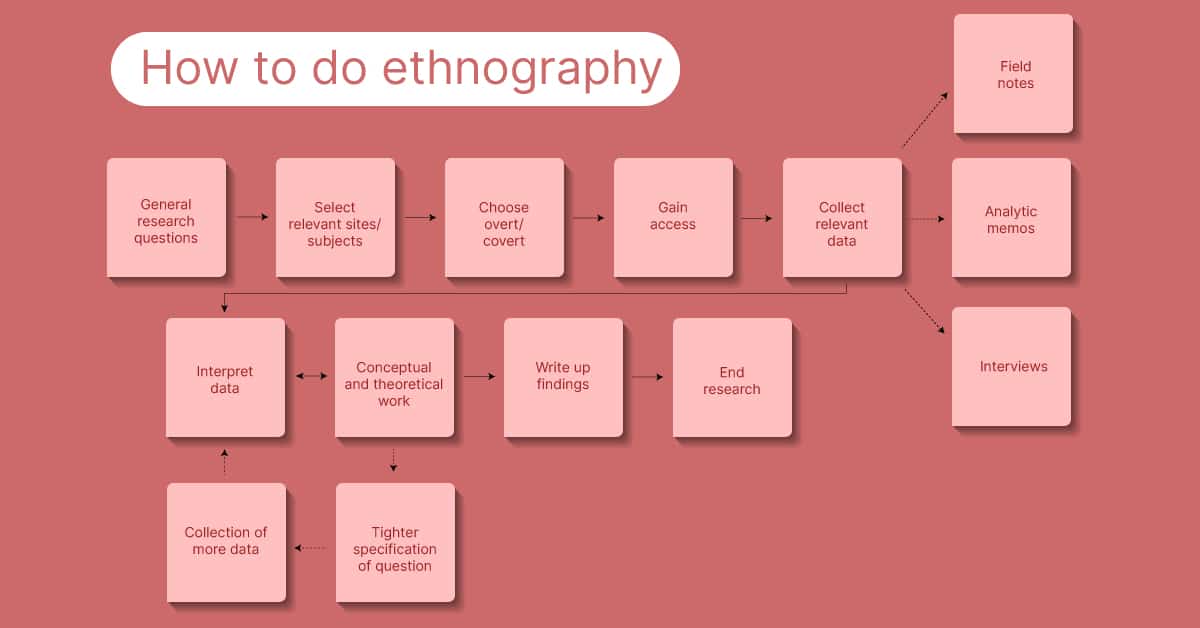

In terms of the types of research and data sources and collection, we have conducted archival research, interviews, focus groups, and ethnographies with diplomats, bureaucrats, military personnel, ex-combatants, civil society advocates, survivors of political violence, refugees, and ordinary citizens. We have grappled with ethical dilemmas, chief among them how to get useful data for our research projects in ways that exceed the minimal standards of human subjects’ research evaluation panels. Relatedly, we have contemplated how to use our platforms to give back to the individuals and communities who have so generously lent us their time and knowledge, and shared with us their personal and sometimes harrowing stories.

Our target audience is first and foremost graduate students and early-career researchers who are interested in possibly conducting fieldwork but who either (1) do not know the full potential or value of fieldwork, (2) know the potential and value of fieldwork but think that it is excessively cost-prohibitive or otherwise infeasible, or (3) who have the interest, the will, and the means but not necessarily the know-how. We also hope that this resource will be of value to graduate programs, as they endeavor to better support students interested in or already conducting field research. Further, we target instructional faculty and graduate advisors (and other institutional gatekeepers like journal and book reviewers), to show that fieldwork does not have to be year-long, to give just one example. Instead, the length of time spent in the field is a function of the aims and scope of a given project. We also seek to formalize and normalize the idea of remote field research, whether conducted because of security concerns in conflict zones, for instance, or because of health and safety concerns, like the Covid-19 pandemic. Accordingly, researchers in the field for shorter stints or who conduct fieldwork remotely should not be penalized.

We note that several excellent resources on fieldwork such as the bibliography compiled by Advancing Conflict Research (2020) catalogue an impressive list of articles addressing questions such as ethics, safety, mental health, reflexivity, and methods. Further resources can be found about the positionality of the researcher in the field while engaging vulnerable communities, such as in the research field of migration ( Jacobsen and Landau 2003 ; Carling, Bivand Erdal, and Ezzati 2014 ; Nowicka and Cieslik 2014 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz 2019 ). However, little has been written beyond conflict-affected contexts, fragile settings, and vulnerable communities. Moreover, as we consulted different texts and resources, we found no comprehensive guide to fieldwork explicitly written with graduate students in mind. It is this gap that we aim to fill.

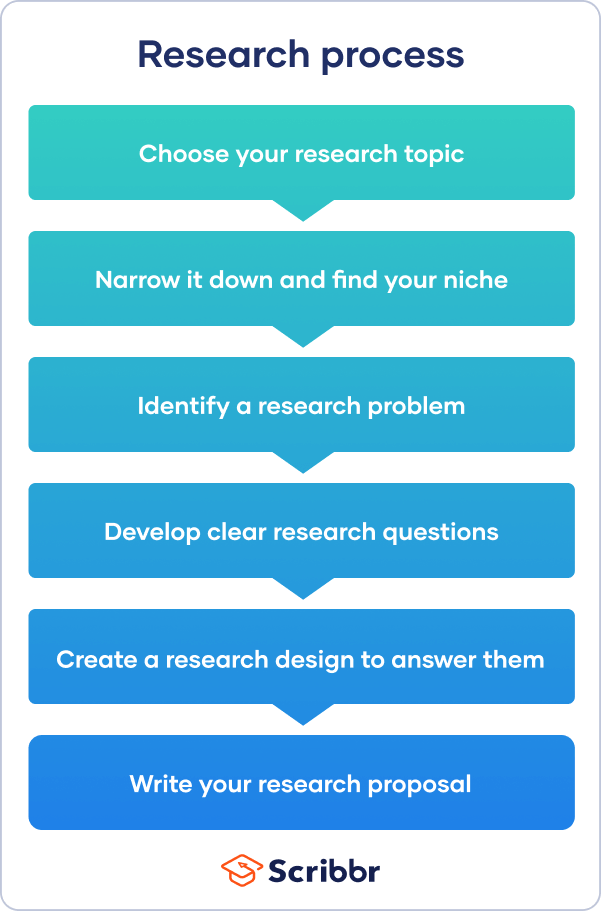

In this paper, we address five general categories of questions that graduate students puzzle over, often without the benefit of others’ “lessons learned.” First, What is field research? Is it just for qualitative scholars? Must it be conducted in a foreign country? How much time in the field is “enough”? Second, What is the purpose of fieldwork? When does it make sense to travel to a field site to collect data? How can fieldwork data be used? Third, What are the nuts and bolts? How does one get ready and how can one optimize limited time and financial resources? Fourth, How does one conduct fieldwork safely? What should a researcher do to keep themselves, research assistants, and research subjects safe? What measures should they take to protect their mental health? Fifth, How does one conduct ethical, beneficent field research?

Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic has impressed upon the discipline the volatility of research projects centered around in-person fieldwork. Lockdowns and closed borders left researchers sequestered at home and unable to travel, forced others to cut short any trips already begun, and unexpectedly confined others still to their fieldwork sites. Other factors that may necessitate a (spontaneous) readjustment of planned field research include natural disasters, a deteriorating security situation in the field site, researcher illness, and unexpected changes in personal circumstances. We, therefore, conclude with a section on the promise and potential pitfalls of remote (or virtual) fieldwork. Throughout this guide, we engage theory and praxis to support an epistemologically and methodologically pluralistic discipline.

The concept of “fieldwork” is not well defined in political science. While several symposia discuss the “nuts and bolts” of conducting research in the field within the pages of political science journals, few ever define it ( Ortbals and Rincker 2009 ; Hsueh, Jensenius, and Newsome 2014 ). Defining the concept of fieldwork is important because assumptions about what it is and what it is not underpin any suggestions for conducting it. A lack of disciplinary consensus about what constitutes “fieldwork,” we believe, explains the lack of a unified definition. Below, we discuss three areas of current disagreement about what “fieldwork” is, including the purpose of fieldwork, where it occurs, and how long it should be. We follow this by offering our definition of fieldwork.

First, we find that many in the discipline view fieldwork as squarely in the domain of qualitative research, whether interpretivist or positivist. However, field research can also serve quantitative projects—for example, by providing crucial context, supporting triangulation, or illustrating causal mechanisms. For instance, Kreft (2019) elaborated her theory of women's civil society mobilization in response to conflict-related sexual violence based on interviews she carried out in Colombia. She then examined cross-national patterns through statistical analysis. Conversely, Willis's research on the United States military in East Asia began with quantitative data collection and analysis of protest events before turning to fieldwork to understand why protests occurred in some instances but not others. Researchers can also find quantifiable data in the field that is otherwise unavailable to them at home ( Read 2006 ; Chambers-Ju 2014 ; Jensenius 2014 ). Accordingly, fieldwork is not in the domain of any particular epistemology or methodology as its purpose is to acquire data for further information.

Second, comparative politics and international relations scholars often opine that fieldwork requires leaving the country in which one's institution is based. Instead, we propose that what matters most is the nature of the research project, not the locale. For instance, some of us in the international relations subfield have interviewed representatives of intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), whose headquarters are generally located in Global North countries. For someone pursuing a Ph.D. in the United States and writing on transnational advocacy networks, interviews with INGO representatives in New York certainly count as fieldwork ( Zvobgo 2020 ). Similarly, a graduate student who returns to her home country to interview refugees and native citizens is conducting a field study as much as a researcher for whom the context is wholly foreign. Such interviews can provide necessary insights and information that would not have been gained otherwise—one of the key reasons researchers conduct fieldwork in the first place. In other instances, conducting any in-person research is simply not possible, due to financial constraints, safety concerns, or other reasons. For example, the Covid-19 pandemic has forced many researchers to shift their face-to-face research plans to remote data collection, either over the phone or virtually ( Howlett 2021 , 2). For some research projects, gathering data through remote methods may yield the same if not similar information than in-person research ( Howlett 2021 , 3–4). As Howlett (2021 , 11) notes, digital platforms may offer researchers the ability to “embed ourselves in other contexts from a distance” and glimpse into our subjects’ lives in ways similar to in-person research. By adopting a broader definition of fieldwork, researchers can be more flexible in getting access to data sources and interacting with research subjects.

Third, there is a tendency, especially among comparativists, to only count fieldwork that spans the better part of a year; even “surgical strike” field research entails one to three months, according to some scholars ( Ortbals and Rincker 2009 ; Weiss, Hicken, and Kuhonta 2017 ). The emphasis on spending as much time as possible in the field is likely due to ethnographic research traditions, reflected in classics such as James Scott's Weapons of the Weak , which entail year-long stints of research. However, we suggest that the appropriate amount of time in the field should be assessed on a project-by-project basis. Some studies require the researcher to be in the field for long periods; others do not. For example, Willis's research on the discourse around the United States’ military presence in overseas host communities has required months in the field. By contrast, Kreft only needed ten days in New York to carry out interviews with diplomats and United Nations staff, in a context with which she already had some familiarity from a prior internship. Likewise, Zvobgo spent a couple of weeks in her field research sites, conducting interviews with directors and managers of prominent human rights nongovernmental organizations. This population is not so large as to require a whole month or even a few months. This has also been the case for Irgil, as she had spent one month in the field site conducting interviews with ordinary citizens. The goal of the project was to acquire information on citizens’ perceptions of refugees. As we discuss in the next section, when deciding how long to spend in the field, scholars must consider the information their project requires and consider the practicalities of fieldwork, notably cost.

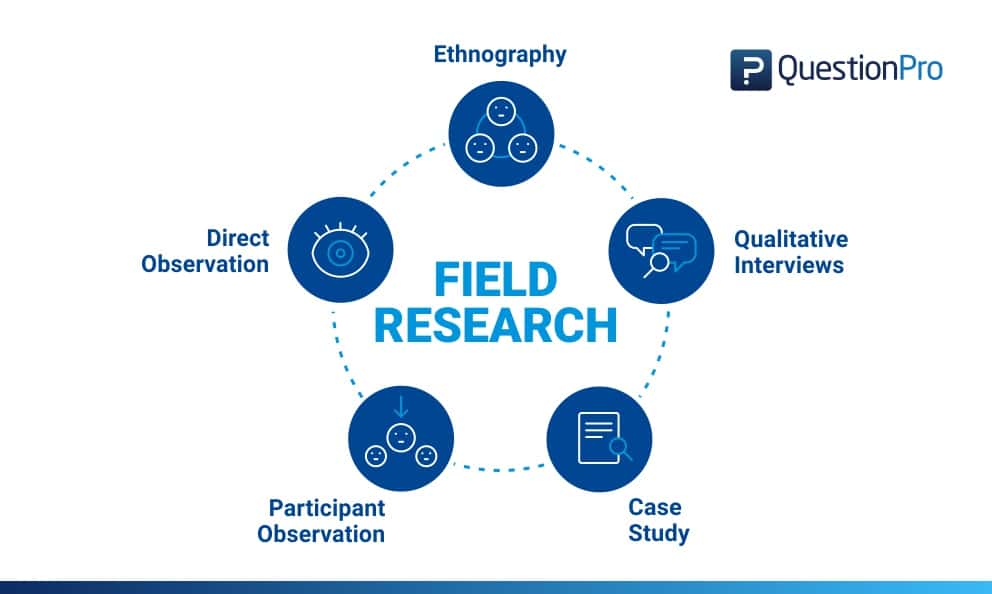

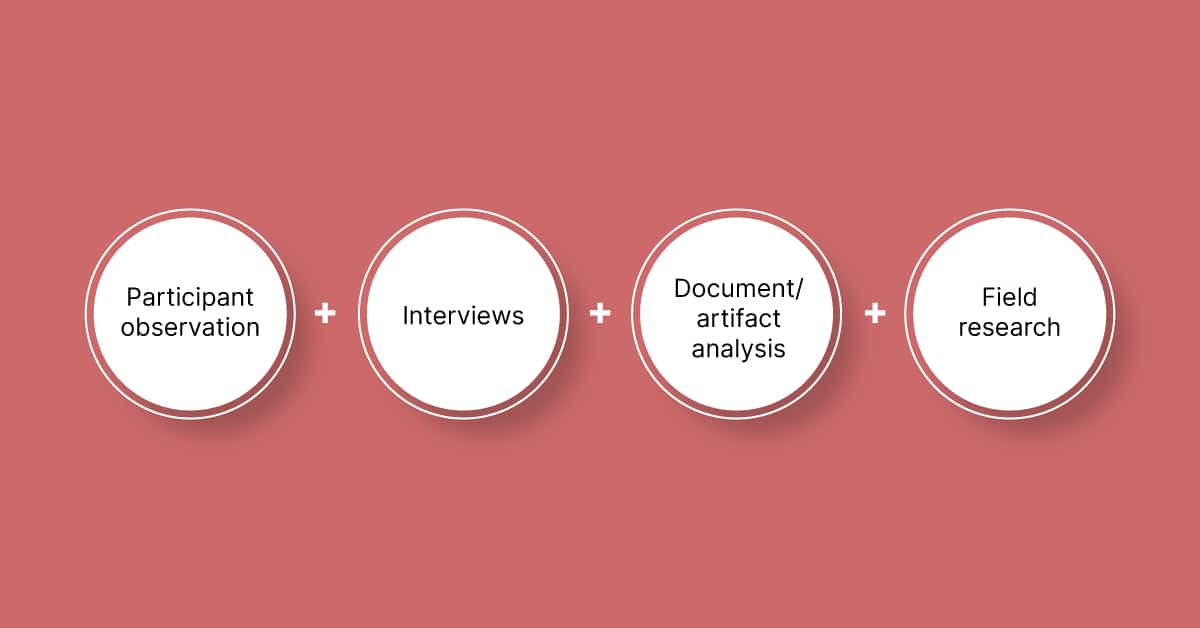

Thus, we highlight three essential points in fieldwork and offer a definition accordingly: fieldwork involves acquiring information, using any set of appropriate data collection techniques, for qualitative, quantitative, or experimental analysis through embedded research whose location and duration is dependent on the project. We argue that adopting such a definition of “fieldwork” is necessary to include the multitude of forms fieldwork can take, including remote methods, whose value and challenges the Covid-19 pandemic has impressed upon the discipline.

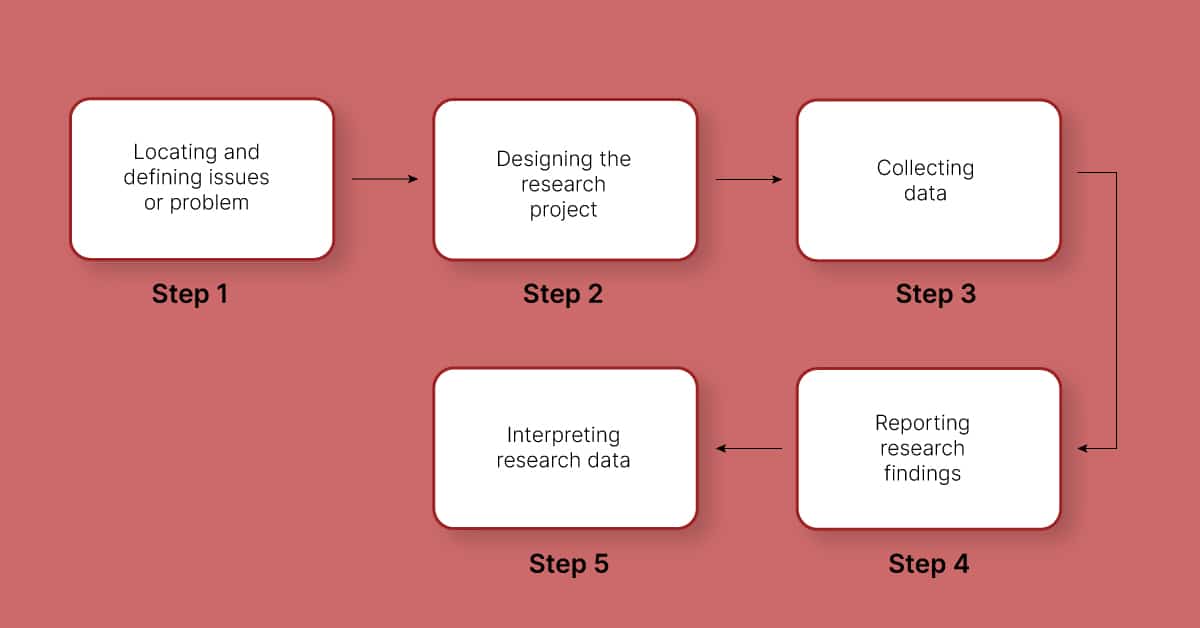

When does a researcher need to conduct fieldwork? Fieldwork can be effective for (1) data collection, (2) theory building, and (3) theory testing. First, when a researcher is interested in a research topic, yet they could not find an available and/or reliable data source for the topic, fieldwork could provide the researcher with plenty of options. Some research agendas can require researchers to visit archives to review historical documents. For example, Greitens (2016) visited national archives in the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States to find historical documents about the development of coercive institutions in past authoritarian governments for her book, Dictators and Their Secret Police . Also, newly declassified archival documents can open new possibilities for researchers to examine restricted topics. To illustrate, thanks to the newly released archival records of the Chinese Communist Party's communications, and exchange of visits with the European communist world, Sarotte (2012) was able to study the Party's decision to crack down on Tiananmen protesters, which had previously been deemed as an unstudiable topic due to the limited data.

Other research agendas can require researchers to conduct (semistructured) in-depth interviews to understand human behavior or a situation more closely, for example, by revealing the meanings of concepts for people and showing how people perceive the world. For example, O'Brien and Li (2005) conducted in-depth interviews with activists, elites, and villagers to understand how these actors interact with each other and what are the outcomes of the interaction in contentious movements in rural China. Through research, they revealed that protests have deeply influenced all these actors’ minds, a fact not directly observable without in-depth interviews.

Finally, data collection through fieldwork should not be confined to qualitative data ( Jensenius 2014 ). While some quantitative datasets can be easily compiled or accessed through use of the internet or contact with data-collection agencies, other datasets can only be built or obtained through relationships with “gatekeepers” such as government officials, and thus require researchers to visit the field ( Jensenius 2014 ). Researchers can even collect their own quantitative datasets by launching surveys or quantifying data contained in archives. In a nutshell, fieldwork will allow researchers to use different techniques to collect and access original/primary data sources, whether these are qualitative, quantitative, or experimental in nature, and regardless of the intended method of analysis. 2

But fieldwork is not just for data collection as such. Researchers can accomplish two other fundamental elements of the research process: theory building and theory testing. When a researcher finds a case where existing theories about a phenomenon do not provide plausible explanations, they can build a theory through fieldwork ( Geddes 2003 ). Lee's experience provides a good example. When studying the rise of a protest movement in South Korea for her dissertation, Lee applied commonly discussed social movement theories, grievances, political opportunity, resource mobilization, and repression, to explain the movement's eruption and found that these theories do not offer a convincing explanation for the protest movement. She then moved on to fieldwork and conducted interviews with the movement participants to understand their motivations. Finally, through those interviews, she offered an alternative theory that the protest participants’ collective identity shaped during the authoritarian past played a unifying factor and eventually led them to participate in the movement. Her example shows that theorization can take place through careful review and rigorous inference during fieldwork.

Moreover, researchers can test their theory through fieldwork. Quantitative observational data has limitations in revealing causal mechanisms ( Esarey 2017 ). Therefore, many political scientists turn their attention to conducting field experiments or lab-in-the-field experiments to reveal causality ( Druckman et al. 2006 ; Beath, Christia, and Enikolopov 2013 ; Finseraas and Kotsadam 2017 ), or to leveraging in-depth insights or historical records gained through qualitative or archival research in process-tracing ( Collier 2011 ; Ricks and Liu 2018 ). Surveys and survey experiments may also be useful tools to substantiate a theoretical story or test a theory ( Marston 2020 ). Of course, for most Ph.D. students, especially those not affiliated with more extensive research projects, some of these options will be financially prohibitive.

A central concern for graduate students, especially those working with a small budget and limited time, is optimizing time in the field and integrating remote work. We offer three pieces of advice: have a plan, build in flexibility, and be strategic, focusing on collecting data that are unavailable at home. We also discuss working with local translators or research assistants. Before we turn to these more practical issues arising during fieldwork, we address a no less important issue: funding.

The challenge of securing funds is often overlooked in discussions of what constitutes field research. Months- or year-long in-person research can be cost-prohibitive, something academic gatekeepers must consider when evaluating “what counts” and “what is enough.” Unlike their predecessors, many graduate students today have a significant amount of debt and little savings. 3 Additionally, if researchers are not able to procure funding, they have to pay out of pocket and possibly take on more debt. Not only is in-person fieldwork costly, but researchers may also have to forego working while they are in the field, making long stretches in the field infeasible for some.

For researchers whose fieldwork involves travelling to another location, procuring funding via grants, fellowships, or other sources is a necessity, regardless of how long one plans to be in the field. A good mantra for applying for research funding is “apply early and often” ( Kelsky 2015 , 110). Funding applications take a considerable amount of time to prepare, from writing research statements to requesting letters of recommendation. Even adapting one's materials for different applications takes time. Not only is the application process itself time-consuming, but the time between applying for and receiving funds, if successful, can be quite long, from several months to a year. For example, after defending her prospectus in May 2019, Willis began applying to funding sources for her dissertation, all of which had deadlines between June and September. She received notifications between November and January; however, funds from her successful applications were not available until March and April, almost a year later. 4 Accordingly, we recommend applying for funding as early as possible; this not only increases one's chances of hitting the ground running in the field, but the application process can also help clarify the goals and parameters of one's research.

Graduate students should also apply often for funding opportunities. There are different types of funding for fieldwork: some are larger, more competitive grants such as the National Science Foundation Political Science Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant in the United States, others, including sources through one's own institution, are smaller. Some countries, like Sweden, boast a plethora of smaller funding agencies that disburse grants of 20,000–30,0000 Swedish Kronor (approx. 2,500–3,500 U.S. dollars) to Ph.D. students in the social sciences. Listings of potential funding sources are often found on various websites including those belonging to universities, professional organizations (such as the American Political Science Association or the European Consortium for Political Research), and governmental institutions dealing with foreign affairs. Once you have identified fellowships and grants for which you and your project are a good match, we highly recommend soliciting information and advice from colleagues who have successfully applied for them. This can include asking them to share their applications with you, and if possible, to have them, another colleague or set of colleagues read through your project description and research plan (especially for bigger awards) to ensure that you have made the best possible case for why you should be selected. While both large and small pots of funding are worth applying for, many researchers end up funding their fieldwork through several small grants or fellowships. One small award may not be sufficient to fund the entirety of one's fieldwork, but several may. For example, Willis's fieldwork in Japan and South Korea was supported through fellowships within each country. Similarly, Irgil was able to conduct her fieldwork abroad through two different and relatively smaller grants by applying to them each year.

Of course, situations vary in different countries with respect to what kinds of grants from what kinds of funders are available. An essential part of preparing for fieldwork is researching the funding landscape well in advance, even as early as the start of the Ph.D. We encourage first-time field researchers to be aware that universities and departments may themselves not be aware of the full range of possible funds available, so it is always a good idea to do your own research and watch research-related social media channels. The amount of funding needed thereby depends on the nature of one's project and how long one intends to be in the field. As we elaborate in the next section, scholars should think carefully about their project goals, the data required to meet those goals, and the requisite time to attain them. For some projects, even a couple of weeks in the field is sufficient to get the needed information.

Preparing to Enter “the field”

It is important to prepare for the field as much as possible. What kind of preparations do researchers need? For someone conducting interviews with NGO representatives, this might involve identifying the largest possible pool of potential respondents, securing their contact information, sending them study invitation letters, finding a mutually agreeable time to meet, and pulling together short biographies for each interviewee in order to use your time together most effectively. If you plan to travel to conduct interviews, you should reach out to potential respondents roughly four to six weeks prior to your arrival. For individuals who do not respond, you can follow up one to two weeks before you arrive and, if needed, once more when you are there. This is still no guarantee for success, of course. For Kreft, contacting potential interviewees in Colombia initially proved more challenging than anticipated, as many of the people she targeted did not respond to her emails. It turned out that many Colombians have a preference for communicating via phone or, in particular, WhatsApp. Some of those who responded to her emails sent in advance of her field trip asked her to simply be in touch once she was in the country, to set up appointments on short notice. This made planning and arranging her interview schedule more complicated. Therefore, a general piece of advice is to research your target population's preferred communication channels and mediums in the field site if email requests yield no or few responses.

In general, we note for the reader that contacting potential research participants should come after one has designed an interview questionnaire (plus an informed consent protocol) and sought and received, where applicable, approval from institutional review boards (IRBs) or other ethical review procedures in place (both at one's home institution/in the country of the home institution as well as in the country where one plans to conduct research if travelling abroad). The most obvious advantage of having the interview questionnaire in place and having secured all necessary institutional approvals before you start contacting potential interviewees is that you have a clearer idea of the universe of individuals you would like to interview, and for what purpose. Therefore, it is better to start sooner rather than later and be mindful of “high seasons,” when institutional and ethical review boards are receiving, processing, and making decisions on numerous proposals. It may take a few months for them to issue approvals.

On the subject of ethics and review panels, we encourage you to consider talking openly and honestly with your supervisors and/or funders about the situations where a written consent form may not be suitable and might need to be replaced with “verbal consent.” For instance, doing fieldwork in politically unstable contexts, highly scrutinized environments, or vulnerable communities, like refugees, might create obstacles for the interviewees as well as the researcher. The literature discusses the dilemma in offering the interviewees anonymity and requesting signed written consent in addition to the emphasis on total confidentiality ( Jacobsen and Landau 2003 ; Mackenzie, McDowell, and Pittaway 2007 ; Saunders, Kitzinger, and Kitzinger 2015 ). Therefore, in those situations, the researcher might need to take the initiative on how to act while doing the interviews as rigorously as possible. In her fieldwork, Irgil faced this situation as the political context of Turkey did not guarantee that there would not be any adverse consequences for interviewees on both sides of her story: citizens of Turkey and Syrian refugees. Consequently, she took hand-written notes and asked interviewees for their verbal consent in a safe interview atmosphere. This is something respondents greatly appreciated ( Irgil 2020 ).

Ethical considerations, of course, also affect the research design itself, with ramifications for fieldwork. When Kreft began developing her Ph.D. proposal to study women's political and civil society mobilization in response to conflict-related sexual violence, she initially aimed to recruit interviewees from the universe of victims of this violence, to examine variation among those who did and those who did not mobilize politically. As a result of deeper engagement with the literature on researching conflict-related sexual violence, conversations with senior colleagues who had interviewed victims, and critical self-reflection of her status as a researcher (with no background in psychology or social work), she decided to change focus and shift toward representatives of civil society organizations and victims’ associations. This constituted a major reconfiguration of her research design, from one geared toward identifying the factors that drive mobilization of victims toward using insights from interviews to understand better how those mobilize perceive and “make sense” of conflict-related sexual violence. Needless to say, this required alterations to research strategies and interview guides, including reassessing her planned fieldwork. Kreft's primary consideration was not to cause harm to her research participants, particularly in the form of re-traumatization. She opted to speak only with those women who on account of their work are used to speaking about conflict-related sexual violence. In no instance did she inquire about interviewees’ personal experiences with sexual violence, although several brought this up on their own during the interviews.

Finally, if you are conducting research in another country where you have less-than-professional fluency in the language, pre-fieldwork planning should include hiring a translator or research assistant, for example, through an online hiring platform like Upwork, or a local university. Your national embassy or consulate is another option; many diplomatic offices have lists of individuals who they have previously contracted. More generally, establishing contact with a local university can be beneficial, either in the form of a visiting researcher arrangement, which grants access to research groups and facilities like libraries or informally contacting individual researchers. The latter may have valuable insights into the local context, contacts to potential research participants, and they may even be able to recommend translators or research assistants. Kreft, for example, hired local research assistants recommended by researchers at a Bogotá-based university and remunerated them equivalent to the salary they would have received as graduate research assistants at the university, while also covering necessary travel expenses. Irgil, on the other hand, established contacts with native citizens and Syrian gatekeepers, who are shop owners in the area where she conducted her research because she had the opportunity to visit the fieldwork site multiple times.

Depending on the research agenda, researchers may visit national archives, local government offices, etc. Before visiting, researchers should contact these facilities and make sure the materials that they need are accessible. For example, Lee visited the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Archives to find the United States’ strategic evaluations on South Korea's dictator in the 1980s. Before her visit, she contacted librarians in the archives, telling them her visit plans and her research purpose. Librarians made suggestions on which categories she should start to review based on her research goal, and thus she was able to make a list of categories of the materials she needed, saving her a lot of her time.

Accessibility of and access to certain facilities/libraries can differ depending on locations/countries and types of facilities. Facilities in authoritarian countries might not be easily accessible to foreign researchers. Within democratic countries, some facilities are more restrictive than others. Situations like the pandemic or national holidays can also restrict accessibility. Therefore, researchers are well advised to do preliminary research on whether a certain facility opens during the time they visit and is accessible to researchers regardless of their citizenship status. Moreover, researchers must contact the staff of facilities to know whether identity verification is needed and if so, what kind of documents (photo I.D. or passport) should be exhibited.

Adapting to the Reality of the Field

Researchers need to be flexible because you may meet people you did not make appointments with, come across opportunities you did not expect, or stumble upon new ideas about collecting data in the field. These happenings will enrich your field experience and will ultimately be beneficial for your research. Similarly, researchers should not be discouraged by interviews that do not go according to plan; they present an opportunity to pursue relevant people who can provide an alternative path to your work. Note that planning ahead does not preclude fortuitous encounters or epiphanies. Rather, it provides a structure for them to happen.

If your fieldwork entails travelling abroad, you will also be able to recruit more interviewees once you arrive at your research site. In fact, you may have greater success in-country; not everyone is willing to respond to a cold email from an unknown researcher in a foreign country. In Irgil's fieldwork, she contacted store owners that are known in the area and who know the community. This eased her process of introduction into the community and recruiting interviewees. For Zvobgo, she had fewer than a dozen interviews scheduled when she travelled to Guatemala to study civil society activism and transitional justice since the internal armed conflict. But she was able to recruit additional participants in-country. Interviewees with whom she built a rapport connected her to other NGOs, government offices, and the United Nations country office, sometimes even making the call and scheduling interviews for her. Through snowball sampling, she was able to triple the number of participants. Likewise, snowball sampling was central to Kreft's recruitment of interview partners. Several of her interviewees connected her to highly relevant individuals she would never have been able to identify and contact based on web searches alone.

While in the field, you may nonetheless encounter obstacles that necessitate adjustments to your original plans. Once Kreft had arrived in Colombia, for example, it transpired quickly that carrying out in-person interviews in more remote/rural areas was near impossible given her means, as these were not easily accessible by bus/coach, further complicated by a complex security situation. Instead, she adjusted her research design and shifted her focus to the big cities, where most of the major civil society organizations are based. She complemented the in-person interviews carried out there with a smaller number of phone interviews with civil society activists in rural areas, and she was also able to meet a few activists operating in rural or otherwise inaccessible areas as they were visiting the major cities. The resulting focus on urban settings changed the kinds of generalizations she was able to make based on her fieldwork data and produced a somewhat different study than initially anticipated.

This also has been the case for Irgil, despite her prior arrangements with the Syrian gatekeepers, which required adjustments as in the case of Kreft. Irgil acquired research clearance one year before, during the interviews with native citizens, conducting the interviews with Syrian refugees. She also had her questionnaire ready based on the previously collected data and the media search she had conducted for over a year before travelling to the field site. As she was able to visit the field site multiple times, two months before conducting interviews with Syrian refugees, she developed a schedule with the Syrian gatekeepers and informants. Yet, once she was in the field, influenced by Turkey's recent political events and the policy of increasing control over Syrian refugees, half of the previously agreed informants changed their minds or did not want to participate in interviews. As Irgil was following the policies and the news related to Syrian refugees in Turkey closely, this did not come as that big of a surprise but challenged the previously developed strategy to recruit interviewees. Thus, she changed the strategy of finding interviewees in the field site, such as asking people, almost one by one, whether they would like to participate in the interview. Eventually, she could not find willing Syrian women refugees as she had planned, which resulted in a male-dominant sample. As researchers encounter such situations, it is essential to remind oneself that not everything can go according to plan, that “different” does not equate to “worse,” but that it is important to consider what changes to fieldwork data collection and sampling imply for the study's overall findings and the contribution it makes to the literature.

We should note that conducting interviews is very taxing—especially when opportunities multiply, as in Zvobgo's case. Depending on the project, each interview can take an hour, if not two or more. Hence, you should make a reasonable schedule: we recommend no more than two interviews per day. You do not want to have to cut off an interview because you need to rush to another one, whether the interviews are in-person or remote. And you do not want to be too exhausted to have a robust engagement with your respondent who is generously lending you their time. Limiting the number of interviews per day is also important to ensure that you can write comprehensive and meaningful fieldnotes, which becomes even more essential where it is not possible to audio-record your interviews. Also, be sure to remember to eat, stay hydrated, and try to get enough sleep.

Finally, whether to provide gifts or payments to the subject also requires adapting to the reality of the field. You must think about payments beforehand when you apply for IRB approval (or whatever other ethical review processes may be in place) since these applications usually contain questions about payments. Obviously, the first step is to carefully evaluate whether the gifts and payments provided can harm the subject or are likely to unduly affect the responses they will give in response to your questions. If that is not the case, you have to make payment decisions based on your budget, field situation, and difficulties in recruitment. Usually, payment of respondents is more common in survey research, whereas it is less common in interviews and focus groups.

Nevertheless, payment practices vary depending on the field and the target group. In some cases, it may become a custom to provide small gifts or payments when interviewing a certain group. In other cases, interviewees might be offended if they are provided with money. Therefore, knowing past practices and field situations is important. For example, Lee provided small coffee gift cards to one group while she did not to the other based on previous practices of other researchers. That is, for a particular group, it has become a custom for interviewers to pay interviewees. Sometimes, you may want to reimburse your subject's interview costs such as travel expenses and provide beverages and snacks during the conduct of research, as Kreft did when conducting focus groups in Colombia. To express your gratitude to your respondents, you can prepare small gifts such as your university memorabilia (e.g., notebooks and pens). Since past practices about payments can affect your interactions and interviews with a target group, you want to seek advice from your colleagues and other researchers who had experiences interacting with the target group. If you cannot find researchers who have this knowledge, you can search for published works on the target population to find if the authors share their interview experiences. You may also consider contacting the authors for advice before your interviews.

Researching Strategically

Distinguishing between things that can only be done in person at a particular site and things that can be accomplished later at home is vital. Prioritize the former over the latter. Lee's fieldwork experience serves as a good example. She studied a conservative protest movement called the Taegeukgi Rally in South Korea. She planned to conduct interviews with the rally participants to examine their motivations for participating. But she only had one month in South Korea. So, she focused on things that could only be done in the field: she went to the rally sites, she observed how protests proceeded, which tactics and chants were used, and she met participants and had some casual conversations with them. Then, she used the contacts she made while attending the rallies to create a social network to solicit interviews from ordinary protesters, her target population. She was able to recruit twenty-five interviewees through good rapport with the people she met. The actual interviews proceeded via phone after she returned to the United States. In a nutshell, we advise you not to be obsessed with finishing interviews in the field. Sometimes, it is more beneficial to use your time in the field to build relationships and networks.

Working With Assistants and Translators

A final consideration on logistics is working with research assistants or translators; it affects how you can carry out interviews, focus groups, etc. To what extent constant back-and-forth translation is necessary or advisable depends on the researcher's skills in the interview language and considerations about time and efficiency. For example, Kreft soon realized that she was generally able to follow along quite well during her interviews in Colombia. In order to avoid precious time being lost to translation, she had her research assistant follow the interview guide Kreft had developed, and interjected follow-up questions in Spanish or English (then to be translated) as they arose.

Irgil's and Zvobgo's interviews went a little differently. Irgil's Syrian refugee interviewees in Turkey were native Arabic speakers, and Zvobgo's interviewees in Guatemala were native Spanish speakers. Both Irgil and Zvobgo worked with research assistants. In Irgil's case, her assistant was a Syrian man, who was outside of the area. Meanwhile, Zvobgo's assistant was an undergraduate from her home institution with a Spanish language background. Irgil and Zvobgo began preparing their assistants a couple of months before entering the field, over Skype for Irgil and in-person for Zvobgo. They offered their assistants readings and other resources to provide them with the necessary background to work well. Both Irgil and Zvobgo's research assistants joined them in the interviews and actually did most of the speaking, introducing the principal investigator, explaining the research, and then asking the questions. In Zvobgo's case, interviewee responses were relayed via a professional interpreter whom she had also hired. After every interview, Irgil and Zvobgo and their respective assistants discussed the answers of the interviewees, potential improvements in phrasing, and elaborated on their hand-written interview notes. As a backup, Zvobgo, with the consent of her respondents, had accompanying audio recordings.

Researchers may carry out fieldwork in a country that is considerably less safe than what they are used to, a setting affected by conflict violence or high crime rates, for instance. Feelings of insecurity can be compounded by linguistic barriers, cultural particularities, and being far away from friends and family. Insecurity is also often gendered, differentially affecting women and raising the specter of unwanted sexual advances, street harassment, or even sexual assault ( Gifford and Hall-Clifford 2008 ; Mügge 2013 ). In a recent survey of Political Science graduate students in the United States, about half of those who had done fieldwork internationally reported having encountered safety issues in the field, (54 percent female, 47 percent male), and only 21 percent agreed that their Ph.D. programs had prepared them to carry out their fieldwork safely ( Schwartz and Cronin-Furman 2020 , 8–9).

Preventative measures scholars may adopt in an unsafe context may involve, at their most fundamental, adjustments to everyday routines and habits, restricting one's movements temporally and spatially. Reliance on gatekeepers may also necessitate adopting new strategies, such as a less vehement and cold rejection of unwanted sexual advances than one ordinarily would exhibit, as Mügge (2013) illustratively discusses. At the same time, a competitive academic job market, imperatives to collect novel and useful data, and harmful discourses surrounding dangerous fieldwork also, problematically, shape incentives for junior researchers to relax their own standards of what constitutes acceptable risk ( Gallien 2021 ).

Others have carefully collected a range of safety precautions that field researchers in fragile or conflict-affected settings may take before and during fieldwork ( Hilhorst et al. 2016 ). Therefore, we are more concise in our discussion of recommendations, focusing on the specific situations of graduate students. Apart from ensuring that supervisors and university administrators have the researcher's contact information in the field (and possibly also that of a local contact person), researchers can register with their country's embassy or foreign office and any crisis monitoring and prevention systems it has in place. That way, they will be informed of any possible unfolding emergencies and the authorities have a record of them being in the country.

It may also be advisable to set up more individualized safety protocols with one or two trusted individuals, such as friends, supervisors, or colleagues at home or in the fieldwork setting itself. The latter option makes sense in particular if one has an official affiliation with a local institution for the duration of the fieldwork, which is often advisable. Still, we would also recommend establishing relationships with local researchers in the absence of a formal affiliation. To keep others informed of her whereabouts, Kreft, for instance, made arrangements with her supervisors to be in touch via email at regular intervals to report on progress and wellbeing. This kept her supervisors in the loop, while an interruption in communication would have alerted them early if something were wrong. In addition, she announced planned trips to other parts of the country and granted her supervisors and a colleague at her home institution emergency reading access to her digital calendar. To most of her interviews, she was moreover accompanied by her local research assistant/translator. If the nature of the research, ethical considerations, and the safety situation allow, it might also be possible to bring a local friend along to interviews as an “assistant,” purely for safety reasons. This option needs to be carefully considered already in the planning stage and should, particularly in settings of fragility or if carrying out research on politically exposed individuals, be noted in any ethical and institutional review processes where these are required. Adequate compensation for such an assistant should be ensured. It may also be advisable to put in place an emergency plan, that is, choose emergency contacts back home and “in the field,” know whom to contact if something happens, and know how to get to the nearest hospital or clinic.

We would be remiss if we did not mention that, when in an unfamiliar context, one's safety radar may be misguided, so it is essential to listen to people who know the context. For example, locals can give advice on which means of transport are safe and which are not, a question that is of the utmost importance when traveling to appointments. For example, Kreft was warned that in Colombia regular taxis are often unsafe, especially if waved down in the streets, and that to get to her interviews safely, she should rely on a ride-share service. In one instance, a Colombian friend suggested that when there was no alternative to a regular taxi, Kreft should book through the app and share the order details, including the taxi registration number or license plate, with a friend. Likewise, sharing one's cell phone location with a trusted friend while traveling or when one feels unsafe may be a viable option. Finally, it is prudent to heed the safety recommendations and travel advisories provided by state authorities and embassies to determine when and where it is safe to travel. Especially if researchers have a responsibility not only for themselves but also for research assistants and research participants, safety must be a top priority.

This does not mean that a researcher should be careless in a context they know either. Of course, conducting fieldwork in a context that is known to the researcher offers many advantages. However, one should be prepared to encounter unwanted events too. For instance, Irgil has conducted fieldwork in her country of origin in a city she knows very well. Therefore, access to the site, moving around the site, and blending in has not been a problem; she also has the advantage of speaking the native language. Yet, she took notes of the streets she walked in, as she often returned from the field site after dark and thought she might get confused after a tiring day. She also established a closer relationship with two or three store owners in different parts of the field site if she needed something urgent, like running out of battery. Above all, one should always be aware of one's surroundings and use common sense. If something feels unsafe, chances are it is.

Fieldwork may negatively affect the researcher's mental health and mental wellbeing regardless of where one's “field” is, whether related to concerns about crime and insecurity, linguistic barriers, social isolation, or the practicalities of identifying, contacting and interviewing research participants. Coping with these different sources of stress can be both mentally and physically exhausting. Then there are the things you may hear, see and learn during the research itself, such as gruesome accounts of violence and suffering conveyed in interviews or archival documents one peruses. Kreft and Zvobgo have spoken with women victims of conflict-related sexual violence, who sometimes displayed strong emotions of pain and anger during the interviews. Likewise, Irgil and Willis have spoken with members of other vulnerable populations such as refugees and former sex workers ( Willis 2020 ).

Prior accounts ( Wood 2006 ; Loyle and Simoni 2017 ; Skjelsbæk 2018 ; Hummel and El Kurd 2020 ; Williamson et al. 2020 ; Schulz and Kreft 2021 ) show that it is natural for sensitive research and fieldwork challenges to affect or even (vicariously) traumatize the researcher. By removing researchers from their regular routines and support networks, fieldwork may also exacerbate existing mental health conditions ( Hummel and El Kurd 2020 ). Nonetheless, mental wellbeing is rarely incorporated into fieldwork courses and guidelines, where these exist at all. But even if you know to anticipate some sort of reaction, you rarely know what that reaction will be until you experience it. When researching sensitive or difficult topics, for example, reactions can include sadness, frustration, anger, fear, helplessness, and flashbacks to personal experiences of violence ( Williamson et al. 2020 ). For example, Kreft responded with episodic feelings of depression and both mental and physical exhaustion. But curiously, these reactions emerged most strongly after she had returned from fieldwork and in particular as she spent extended periods analyzing her interview data, reliving some of the more emotional scenes during the interviews and being confronted with accounts of (sexual) violence against women in a concentrated fashion. This is a crucial reminder that fieldwork does not end when one returns home; the after-effects may linger. Likewise, Zvobgo was physically and mentally drained upon her return from the field. Both Kreft and Zvobgo were unable to concentrate for long periods of time and experienced lower-than-normal levels of productivity for weeks afterward, patterns that formal and informal conversations with other scholars confirm to be common ( Schulz and Kreft 2021 ). Furthermore, the boundaries between “field” and “home” are blurred when conducting remote fieldwork ( Howlett 2021 , 11).

Nor are these adverse reactions limited to cases where the researcher has carried out the interviews themselves. Accounts of violence, pain, and suffering transported in reports, secondary literature, or other sources can evoke similar emotional stress, as Kreft experienced when engaging in a concentrated fashion with additional accounts of conflict-related sexual violence in Colombia and with the feminist literature on sexual and gender-based violence in the comfort of her Swedish office. This could also be applicable to Irgil's fieldwork as she interviewed refugees whose traumas have come out during the interviews or recall specific events triggered by the questions. Likewise, Lee has reviewed primary and secondary materials on North Korean defectors in the national archives and these materials contain violent, intense, emotional narratives.

Fortunately, there are several strategies to cope with and manage such adverse consequences. In a candid and insightful piece, other researchers have discussed the usefulness of distractions, sharing with colleagues, counseling, exercise, and, probably less advisable in the long term, comfort eating and drinking ( Williamson et al. 2020 ; see also Loyle and Simoni 2017 ; Hummel and El Kurd 2020 ). Our experiences largely tally with their observations. In this section, we explore some of these in more detail.

First, in the face of adverse consequences on your mental wellbeing, whether in the field or after your return, it is essential to be patient and generous with yourself. Negative effects on the researcher's mental wellbeing can hit in unexpected ways and at unexpected times. Even if you think that certain reactions are disproportionate or unwarranted at that specific moment, they may simply have been building up over a long time. They are legitimate. Second, the importance of taking breaks and finding distractions, whether that is exercise, socializing with friends, reading a good book, or watching a new series, cannot be overstated. It is easy to fall into a mode of thinking that you constantly have to be productive while you are “in the field,” to maximize your time. But as with all other areas in life, balance is key and rest is necessary. Taking your mind off your research and the research questions you puzzle over is also a good way to more fully soak up and appreciate the context in which you find yourself, in the case of in-person fieldwork, and about which you ultimately write.

Third, we cannot stress enough the importance of investing in social relations. Before going on fieldwork, researchers may want to consult others who have done it before them. Try to find (junior) scholars who have done fieldwork on similar kinds of topics or in the same country or countries you are planning to visit. Utilizing colleagues’ contacts and forging connections using social media are valuable strategies to expand your networks (in fact, this very paper is the result of a social media conversation and several of the authors have never met in person). Having been in the same situation before, most field researchers are, in our experience, generous with their time and advice. Before embarking on her first trip to Colombia, Kreft contacted other researchers in her immediate and extended network and received useful advice on questions such as how to move around Bogotá, whom to speak to, and how to find a research assistant. After completing her fieldwork, she has passed on her experiences to others who contacted her before their first fieldwork trip. Informal networks are, in the absence of more formalized fieldwork preparation, your best friend.

In the field, seeking the company of locals and of other researchers who are also doing fieldwork alleviates anxiety and makes fieldwork more enjoyable. Exchanging experiences, advice and potential interviewee contacts with peers can be extremely beneficial and make the many challenges inherent in fieldwork (on difficult topics) seem more manageable. While researchers conducting remote fieldwork may be physically isolated from other researchers, even connecting with others doing remote fieldwork may be comforting. And even when there are no precise solutions to be found, it is heartening or even cathartic to meet others who are in the same boat and with whom you can talk through your experiences. When Kreft shared some of her fieldwork-related struggles with another researcher she had just met in Bogotá and realized that they were encountering very similar challenges, it was like a weight was lifted off her shoulders. Similarly, peer support can help with readjustment after the fieldwork trip, even if it serves only to reassure you that a post-fieldwork dip in productivity and mental wellbeing is entirely natural. Bear in mind that certain challenges are part of the fieldwork experience and that they do not result from inadequacy on the part of the researcher.

Finally, we would like to stress a point made by Inger Skjelsbæk (2018 , 509) and which has not received sufficient attention: as a discipline, we need to take the question of researcher mental wellbeing more seriously—not only in graduate education, fieldwork preparation, and at conferences, but also in reflecting on how it affects the research process itself: “When strong emotions arise, through reading about, coding, or talking to people who have been impacted by [conflict-related sexual violence] (as victims or perpetrators), it may create a feeling of being unprofessional, nonscientific, and too subjective.”

We contend that this is a challenge not only for research on sensitive issues but also for fieldwork more generally. To what extent is it possible, and desirable, to uphold the image of the objective researcher during fieldwork, when we are at our foundation human beings? And going even further, how do the (anticipated) effects of our research on our wellbeing, and the safety precautions we take ( Gifford and Hall-Clifford 2008 ), affect the kinds of questions we ask, the kinds of places we visit and with whom we speak? How do they affect the methods we use and how we interpret our findings? An honest discussion of affective responses to our research in methods sections seems utopian, as emotionality in the research process continues to be silenced and relegated to the personal, often in gendered ways, which in turn is considered unconnected to the objective and scientific research process ( Jamar and Chappuis 2016 ). But as Gifford and Hall-Clifford (2008 , 26) aptly put it: “Graduate education should acknowledge the reality that fieldwork is scholarly but also intimately personal,” and we contend that the two shape each other. Therefore, we encourage political science as a discipline to reflect on researcher wellbeing and affective responses to fieldwork more carefully, and we see the need for methods courses that embrace a more holistic notion of the subjectivity of the researcher.

Interacting with people in the field is one of the most challenging yet rewarding parts of the work that we do, especially in comparison to impersonal, often tedious wrangling and analysis of quantitative data. Field researchers often make personal connections with their interviewees. Consequently, maintaining boundaries can be a bit tricky. Here, we recommend being honest with everyone with whom you interact without overstating the abilities of a researcher. This appears as a challenge in the field, particularly when you empathize with people and when they share profound parts of their lives with you for your research in addition to being “human subjects” ( Fujii 2012 ). For instance, when Irgil interviewed native citizens about the changes in their neighborhood following the arrival of Syrian refugees, many interviewees questioned what she would offer them in return for their participation. Irgil responded that her primary contribution would be her published work. She also noted, however, that academic papers can take a year, sometimes longer, to go through the peer-reviewed process and, once published, many studies have a limited audience. The Syrian refugees posed similar questions. Irgil responded not only with honesty but also, given this population's vulnerable status, she provided them contact information for NGOs with which they could connect if they needed help or answers to specific questions.

For her part, Zvobgo was very upfront with her interviewees about her role as a researcher: she recognized that she is not someone who is on the frontlines of the fight for human rights and transitional justice like they are. All she could/can do is use her platform to amplify their stories, bringing attention to their vital work through her future peer-reviewed publications. She also committed to sending them copies of the work, as electronic journal articles are often inaccessible due to paywalls and university press books are very expensive, especially for nonprofits. Interviewees were very receptive; some were even moved by the degree of self-awareness and the commitment to do right by them. In some cases, this prompted them to share even more, because they knew that the researcher was really there to listen and learn. This is something that junior scholars, and all scholars really, should always remember. We enter the field to be taught. Likewise, Kreft circulated among her interviewees Spanish-language versions of an academic article and a policy brief based on the fieldwork she had carried out in Colombia.

As researchers from the Global North, we recognize a possible power differential between us and our research subjects, and certainly an imbalance in power between the countries where we have been trained and some of the countries where we have done and continue to do field research, particularly in politically dynamic contexts ( Knott 2019 ). This is why we are so concerned with being open and transparent with everyone with whom we come into contact in the field and why we are committed to giving back to those who so generously lend us their time and knowledge. Knott (2019 , 148) summarizes this as “Reflexive openness is a form of transparency that is methodologically and ethically superior to providing access to data in its raw form, at least for qualitative data.”

We also recognize that academics, including in the social sciences and especially those hailing from countries in the Global North, have a long and troubled history of exploiting their power over others for the sake of their research—including failing to be upfront about their research goals, misrepresenting the on-the-ground realities of their field research sites (including remote fieldwork), and publishing essentializing, paternalistic, and damaging views and analyses of the people there. No one should build their career on the backs of others, least of all in a field concerned with the possession and exercise of power. Thus, it is highly crucial to acknowledge the power hierarchies between the researcher and the interviewees, and to reflect on them both in the field and beyond the field upon return.

A major challenge to conducting fieldwork is when researchers’ carefully planned designs do not go as planned due to unforeseen events outside of our control, such as pandemics, natural disasters, deteriorating security situations in the field, or even the researcher falling ill. As the Covid-19 pandemic has made painfully clear, researchers may face situations where in-person research is simply not possible. In some cases, researchers may be barred entry to their fieldwork site; in others, the ethical implications of entering the field greatly outweigh the importance of fieldwork. Such barriers to conducting in-person research require us to reconsider conventional notions of what constitutes fieldwork. Researchers may need to shift their data collection methods, for example, conducting interviews remotely instead of in person. Even while researchers are in the field, they may still need to carry out part of their interviews or surveys virtually or by phone. For example, Kreft (2020) carried out a small number of interviews remotely while she was based in Bogotá, because some of the women's civil society activists with whom she intended to speak were based in parts of the country that were difficult and/or dangerous to access.

Remote field research, which we define as the collection of data over the internet or over the phone where in-person fieldwork is not possible due to security, health or other risks, comes with its own sets of challenges. For one, there may be certain populations that researchers cannot reach remotely due to a lack of internet connectivity or technology such as cellphones and computers. In such instances, there will be a sampling bias toward individuals and groups that do have these resources, a point worth noting when scholars interpret their research findings. In the case of virtual research, the risk of online surveillance, hacking, or wiretapping may also produce reluctance on the part of interviewees to discuss sensitive issues that may compromise their safety. Researchers need to carefully consider how the use of digital technology may increase the risk to research participants and what changes to the research design and any interview guides this necessitates. In general, it is imperative that researchers reflect on how they can ethically use digital technology in their fieldwork ( Van Baalen 2018 ). Remote interviews may also be challenging to arrange for researchers who have not made connections in person with people in their community of interest.

Some of the serendipitous happenings we discussed earlier may also be less likely and snowball sampling more difficult. For example, in phone or virtual interviews, it is harder to build good rapport and trust with interviewees as compared to face-to-face interviews. Accordingly, researchers should be more careful in communicating with interviewees and creating a comfortable interview environment. Especially when dealing with sensitive topics, researchers may have to make several phone calls and sometimes have to open themselves to establishing trust with interviewees. Also, researchers must be careful in protecting interviewees in phone or virtual interviews when they deal with sensitive topics of countries interviewees reside in.

The inability to physically visit one's community of interest may also encourage scholars to critically reflect on how much time in the field is essential to completing their research and to consider creative, alternative means for accessing information to complete their projects. While data collection techniques such as face-to-face interviews and archival work in the field may be ideal in normal times, there exist other data sources that can provide comparably useful information. For example, in her research on the role of framing in the United States base politics, Willis found that social media accounts and websites yielded information useful to her project. Many archives across the world have also been digitized. Researchers may also consider crowdsourcing data from the field among their networks, as fellow academics tend to collect much more data in the field than they ever use in their published works. They may also elect to hire someone, perhaps a graduate student, in a city or a country where they cannot travel and have the individual access, scan, and send archival materials. This final suggestion may prove generally useful to researchers with limited time and financial resources.

Remote qualitative data collection techniques, while they will likely never be “the gold-standard,” also pose several advantages. These techniques may help researchers avoid some of the issues mentioned previously. Remote interviews, for example, are less time-consuming in terms of travel to the interview site ( Archibald et al. 2019 ). The implication is that researchers may have less fatigue from conducting interviews and/or may be able to conduct more interviews. For example, while Willis had little energy to do anything else after an in-person interview (or two) in a given day, she had much more energy after completing remote interviews. Second, remote fieldwork also helps researchers avoid potentially dangerous situations in the field mentioned previously. Lastly, remote fieldwork generally presents fewer financial barriers than in-person research ( Archibald et al. 2019 ). In that sense, considering remote qualitative data collection, a type of “fieldwork” may make fieldwork more accessible to a greater number of scholars.

Many of the substantive, methodological and practical challenges that arise during fieldwork can be anticipated. Proper preparation can help you hit the ground running once you enter your fieldwork destination, whether in-person or virtually. Nonetheless, there is no such thing as being perfectly prepared for the field. Some things will simply be beyond your control, and especially as a newcomer to field research, and you should be prepared for things to not go as planned. New questions will arise, interview participants may cancel appointments, and you might not get the answers you expected. Be ready to make adjustments to research plans, interview guides, or questionnaires. And, be mindful of your affective reactions to the overall fieldwork situation and be gentle with yourself.

We recommend approaching fieldwork as a learning experience as much as, or perhaps even more than, a data collection effort. This also applies to your research topic. While it is prudent always to exercise a healthy amount of skepticism about what people tell you and why, the participants in your research will likely have unique perspectives and knowledge that will challenge yours. Be an attentive listener and remember that they are experts of their own experiences.

We encourage more institutions to offer courses that cover field research preparation and planning, practical advice on safety and wellbeing, and discussion of ethics. Specifically, we align with Schwartz and Cronin-Furman's (2020 , 3) contention “that treating fieldwork preparation as the methodology will improve individual scholars’ experiences and research.” In this article, we outline a set of issue areas in which we think formal preparation is necessary, but we note that our discussion is by no means exhaustive. Formal fieldwork preparation should also extend beyond what we have covered in this article, such as issues of data security and preparing for nonqualitative fieldwork methods. We also note that field research is one area that has yet to be comprehensively addressed in conversations on diversity and equity in the political science discipline and the broader academic profession. In a recent article, Brielle Harbin (2021) begins to fill this gap by sharing her experiences conducting in-person election surveys as a Black woman in a conservative and predominantly white region of the United States and the challenges that she encountered. Beyond race and gender, citizenship, immigration status, one's Ph.D. institution and distance to the field also affect who is able to do what type of field research, where, and for how long. Future research should explore these and related questions in greater detail because limits on who is able to conduct field research constrict the sociological imagination of our field.

While Emmons and Moravcsik (2020) focus on leading Political Science Ph.D. programs in the United States, these trends likely obtain, both in lower ranked institutions in the broader United States as well as in graduate education throughout North America and Europe.