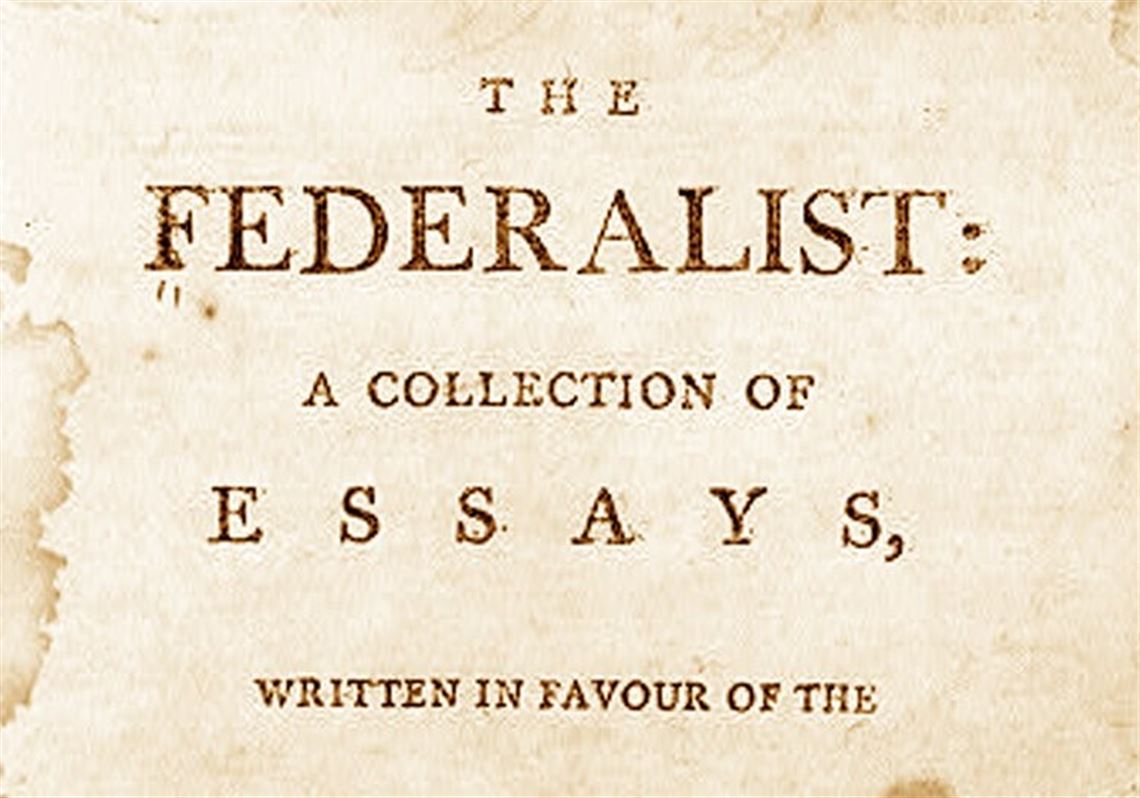

The American Founding Introduction to the Federalist Papers Origin of the FederalistThe 85 essays appeared in one or more of the following four New York newspapers: 1) The New York Journal , edited by Thomas Greenleaf, 2) Independent Journal , edited by John McLean, 3) New York Advertiser , edited by Samuel and John Loudon, and 4) Daily Advertiser , edited by Francis Childs. This site uses the 1818 Gideon edition. Initially, they were intended to be a 20-essay response to the Antifederalist attacks on the Constitution that were flooding the New York newspapers right after the Constitution had been signed in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. The Cato letters started to appear on September 27, George Mason ‘s objections were in circulation and the Brutus Essays were launched on October 18. The number of essays in The Federalist was extended in response to the relentless, and effective, Antifederalist criticism of the proposed Constitution . McLean bundled the first 36 essays together—they appeared in the newspapers between October 27, 1787 and January 8, 1788—and published them as Volume 1 on March 22, 1788. Essays 37 through 77 of The Federalist appeared between January 11 and April 2, 1788. On May 28, McLean took Federalist 37-77 as well as the yet to be published Federalist 78-85 and issued them all as Volume 2 of The Federalist . Between June 14 and August 16, these eight remaining essays— Federalist 78-85—appeared in the Independent Journal and New York Packet . THE STATUS OF THE FEDERALISTOne of the persistent questions concerning the status of The Federalist is this: is it a propaganda tract written to secure ratification of the Constitution and thus of no enduring relevance or is it the authoritative expositor of the meaning of the Constitution having a privileged position in constitutional interpretation? It is tempting to adopt the former position because 1) the essays originated in the rough and tumble of the ratification struggle. It is also tempting to 2) see The Federalist as incoherent; didn’t Hamilton and Madison disagree with each other within five years of co-authoring the essays? Surely the seeds of their disagreement are sown in the very essays! 3) The essays sometimes appeared at a rate of about three per week and, according to Madison , there were occasions when the last part of an essay was being written as the first part was being typed.  - One should not confuse self-serving propaganda with advocating a political position in a persuasive manner. After all, rhetorical skills are a vital part of the democratic electoral process and something a free people have to handle. These are op-ed pieces of the highest quality addressing the most pressing issues of the day.

- Moreover, because Hamilton and Madison parted ways doesn’t mean that they weren’t in fundamental agreement in 1787-1788 about the need for a more energetic form of government. And just because they were written with a certain haste, doesn’t mean that they were unreflective and not well written. Federalist 10 , the most famous of all the essays, is actually the final draft of an essay that originated in Madison ‘s Vices in 1787, matured at the Constitutional Convention in June 1787, and was refined in a letter to Jefferson in October 1787. All of Jay ‘s essays focus on foreign policy, the heart of the Madisonian essays are Federalist 37-51 on the great difficulty of founding, and Hamilton tends to focus on the institutional features of federalism and the separation of powers.

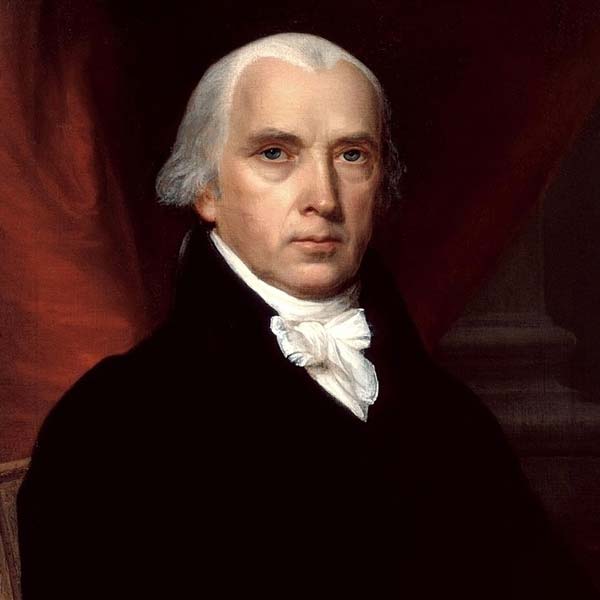

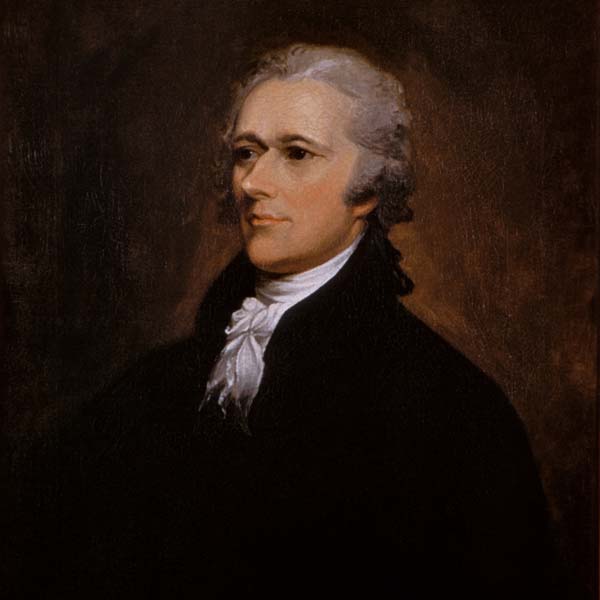

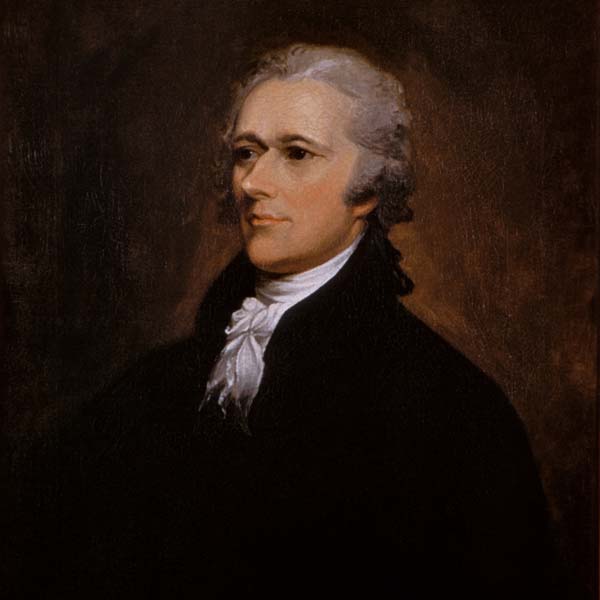

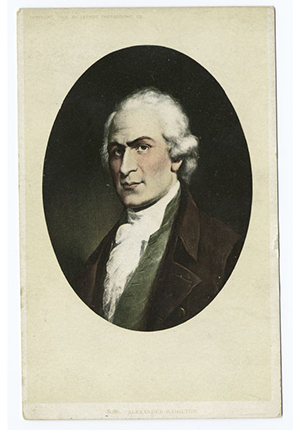

I suggest, furthermore, that the moment these essays were available in book form, they acquired a status that went beyond the more narrowly conceived objective of trying to influence the ratification of the Constitution . The Federalist now acquired a “timeless” and higher purpose, a sort of icon status equal to the very Constitution that it was defending and interpreting. And we can see this switch in tone in Federalist 37 when Madison invites his readers to contemplate the great difficulty of founding. Federalist 38 , echoing Federalist 1 , points to the uniqueness of the America Founding: never before had a nation been founded by the reflection and choice of multiple founders who sat down and deliberated over creating the best form of government consistent with the genius of the American people. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Constitution as the work of “demigods,” and The Federalist “the best commentary on the principles of government, which ever was written.” There is a coherent teaching on the constitutional aspects of a new republicanism and a new federalism in The Federalist that makes the essays attractive to readers of every generation. AUTHORSHIP OF THE FEDERALISTA second question about The Federalist is how many essays did each person write? James Madison —at the time a resident of New York since he was a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress that met in New York— John Jay , and Alexander Hamilton —both of New York wrote these essays under the pseudonym, “Publius.” So one answer to the question is that it doesn’t matter since everyone signed off under the same pseudonym, “Publius.” But given the icon status of The Federalist , there has been an enduring curiosity about the authorship of the essays. Although it is virtually agreed that Jay wrote only five essays, there have been several disputes over the decades concerning the distribution of the essays between Hamilton and Madison . Suffice it to note, that Madison ‘s last contribution was Federalist 63 , leaving Hamilton as the exclusive author of the nineteen Executive and Judiciary essays. Madison left New York in order to comply with the residence law in Virginia concerning eligibility for the Virginia ratifying convention . There is also widespread agreement that Madison wrote the first 13 essays on the great difficulty of founding. There is still dispute over the authorship of Federalist 50-58, but these have persuasively been resolved in favor of Madison . OUTLINE OF THE FEDERALISTA third question concerns how to “outline” the essays into its component parts. We get some natural help from the authors themselves. Federalist 1 outlines the six topics to be discussed in the essays without providing an exact table of contents. The authors didn’t know in October 1787 how many essays would be devoted to each topic. Nevertheless, if one sticks with the “formal division of the subject” outlined in the first essay, it is possible to work out the actual division of essays into the six topic areas or “points” after the fact so to speak.  Martin Diamond was one of the earliest scholars to break The Federalist into its component parts. He identified Union as the subject matter of the first 36 Federalist essays and Republicanism as the subject matter of the last 49 essays. There is certain neatness to this breakdown, and accuracy to the Union essays. The fist three topics outlined in Federalist 1 are: - The utility of the union

- The insufficiency of the present confederation under the Articles of Confederation

- The need for a government at least as energetic as the one proposed.

The opening paragraph of Federalist 15 summarizes the previous 14 essays and says: “in pursuance of the plan which I have laid down for the pursuance of the subject, the point next in order to be examined is the ‘insufficiency of the present confederation.’” So we can say with confidence that Federalist 1-14 is devoted to the utility of the union. Similarly, Federalist 23 opens with the following observation: “the necessity of a Constitution, at least equally energetic as the one proposed…is the point at the examination of the examination at which we are arrived.” Thus Federalist 15-22 covered the second point dealing with union or federalism. Finally, Federalist 37 makes it clear that coverage of the third point has come to an end and new beginning has arrived. And since McLean bundled the first 36 essays into Volume 1, we have confidence in declaring a conclusion to the coverage of the first three points all having to do with union and federalism. The difficulty with the Diamond project is that it becomes messy with respect to topics 4, 5, and 6 listed in Federalist 1 : 4) the Constitution conforms to the true principles of republicanism , 5) the analogy of the Constitution to state governments, and 6) the added benefits from adopting the Constitution . Let’s work our way backward. In Federalist 85 , we learn that “according to the formal division of the subject of these papers announced in my first number, there would appear still to remain for discussion two points,” namely, the fifth and sixth points. That leaves, “republicanism,” the fourth point, as the topic for Federalist 37-84, or virtually the entire Part II of The Federalist . I propose that we substitute the word Constitutionalism for Republicanism as the subject matter for essays 37-51, reserving the appellation Republicanism for essays 52-84. This substitution is similar to the “Merits of the Constitution ” designation offered by Charles Kesler in his new introduction to the Rossiter edition; the advantage of this Constitutional approach is that it helps explain why issues other than Republicanism strictly speaking are covered in Federalist 37-46. Kesler carries the Constitutional designation through to the end; I suggest we return to Republicanism with Federalist 52 . Finally, to assist the reader in following the argument of The Federalist , I have broken the argument down into seven major parts. This breakdown follows the open ended one provided in Federalist 1 . This can be used in conjunction with the Essay-by-Essay Summary and the actual text of The Federalist . Note: The text of The Federalist used on this site is from the edition reviewed by James Madison and published by Jacob Gideon in 1818. There may be slight variations in language from the essays as originally published.  State: Virginia Age at Convention: 36 Date of Birth: March 16, 1751 Date of Death: June 28, 1836 Schooling: College of New Jersey (Princeton) 1771 Occupation: Politician Prior Political Experience: Lower House of Virginia 1776, 1783-1786, Upper House of Virginia 1778, Virginia State Constitutional Convention 1776, Confederation Congress 1781- 1783, 1786-1788, Virginia House of Delegates 1784-1786, Annapolis Convention Signer 1786 Committee Assignments: Third Committee of Representation, Committee of Slave Trade, Committee of Leftovers, Committee of Style Convention Contributions: Arrived May 25 and was present through the signing of the Constitution. He is best known for writing the Virginia Plan and defending the attempt to build a stronger central government. He kept copious notes of the proceedings of the Convention which were made available to the general public upon his death in 1836. William Pierce stated that “Mr. Madison is a character who has long been in public life; and what is very remarkable every Person seems to acknowledge his greatness. He blends together the profound politician, with the Scholar. … The affairs of the United States, he perhaps, has the most correct knowledge of, of any Man in the Union.” New Government Participation: Attended the ratification convention of Virginia and supported the ratification of the Constitution. He also coauthored the Federalist Papers. Served as Virginia’s U.S. Representative (1789-1797) where he drafted and debated the First Twelve Amendments to the Constitution; ten of which became the Bill of Rights; author of the Virginia Resolutions which argued that the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 were unconstitutional. Served as Secretary of State (1801-1809) Elected President of the United States of America (1809-1817). Biography from the National Archives: The oldest of 10 children and a scion of the planter aristocracy, Madison was born in 1751 at Port Conway, King George County, VA, while his mother was visiting her parents. In a few weeks she journeyed back with her newborn son to Montpelier estate, in Orange County, which became his lifelong home. He received his early education from his mother, from tutors, and at a private school. An excellent scholar though frail and sickly in his youth, in 1771 he graduated from the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), where he demonstrated special interest in government and the law. But, considering the ministry for a career, he stayed on for a year of postgraduate study in theology. Back at Montpelier, still undecided on a profession, Madison soon embraced the patriot cause, and state and local politics absorbed much of his time. In 1775 he served on the Orange County committee of safety; the next year at the Virginia convention, which, besides advocating various Revolutionary steps, framed the Virginia constitution; in 1776-77 in the House of Delegates; and in 1778-80 in the Council of State. His ill health precluded any military service. In 1780 Madison was chosen to represent Virginia in the Continental Congress (1780-83 and 1786-88). Although originally the youngest delegate, he played a major role in the deliberations of that body. Meantime, in the years 1784-86, he had again sat in the Virginia House of Delegates. He was a guiding force behind the Mount Vernon Conference (1785), attended the Annapolis Convention (1786), and was otherwise highly instrumental in the convening of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He had also written extensively about deficiencies in the Articles of Confederation. Madison was clearly the preeminent figure at the convention. Some of the delegates favored an authoritarian central government; others, retention of state sovereignty; and most occupied positions in the middle of the two extremes. Madison, who was rarely absent and whose Virginia Plan was in large part the basis of the Constitution, tirelessly advocated a strong government, though many of his proposals were rejected. Despite his poor speaking capabilities, he took the floor more than 150 times, third only after Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson. Madison was also a member of numerous committees, the most important of which were those on postponed matters and style. His journal of the convention is the best single record of the event. He also played a key part in guiding the Constitution through the Continental Congress. Playing a lead in the ratification process in Virginia, too, Madison defended the document against such powerful opponents as Patrick Henry, George Mason, and Richard Henry Lee. In New York, where Madison was serving in the Continental Congress, he collaborated with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in a series of essays that in 1787-88 appeared in the newspapers and were soon published in book form as The Federalist (1788). This set of essays is a classic of political theory and a lucid exposition of the republican principles that dominated the framing of the Constitution. In the U.S. House of Representatives (1789-97), Madison helped frame and ensure passage of the Bill of Rights. He also assisted in organizing the executive department and creating a system of federal taxation. As leaders of the opposition to Hamilton’s policies, he and Jefferson founded the Democratic-Republican Party. In 1794 Madison married a vivacious widow who was 16 years his junior, Dolley Payne Todd, who had a son; they were to raise no children of their own. Madison spent the period 1797-1801 in semiretirement, but in 1798 he wrote the Virginia Resolutions, which attacked the Alien and Sedition Acts. While he served as Secretary of State (1801-9), his wife often served as President Jefferson’s hostess. In 1809 Madison succeeded Jefferson. Like the first three Presidents, Madison was enmeshed in the ramifications of European wars. Diplomacy had failed to prevent the seizure of U.S. ships, goods, and men on the high seas, and a depression wracked the country. Madison continued to apply diplomatic techniques and economic sanctions, eventually effective to some degree against France. But continued British interference with shipping, as well as other grievances, led to the War of 1812. The war, for which the young nation was ill prepared, ended in stalemate in December 1814 when the inconclusive Treaty of Ghent which nearly restored prewar conditions, was signed. But, thanks mainly to Andrew Jackson’s spectacular victory at the Battle of New Orleans (Chalmette) in January 1815, most Americans believed they had won. Twice tested, independence had survived, and an ebullient nationalism marked Madison’s last years in office, during which period the Democratic-Republicans held virtually uncontested sway. In retirement after his second term, Madison managed Montpelier but continued to be active in public affairs. He devoted long hours to editing his journal of the Constitutional Convention, which the government was to publish 4 years after his death. He served as co-chairman of the Virginia constitutional convention of 1829-30 and as rector of the University of Virginia during the period 1826-36. Writing newspaper articles defending the administration of Monroe, he also acted as his foreign policy adviser. Madison spoke out, too, against the emerging sectional controversy that threatened the existence of the Union. Although a slaveholder all his life, he was active during his later years in the American Colonization Society, whose mission was the resettlement of slaves in Africa. Madison died at the age of 85 in 1836, survived by his wife and stepson. Age at Convention: 62 Date of Birth: December 11,1725 Date of Death: October 7, 1792 Schooling: Personal tutors Occupation: Planter and Slave Holder, Lending and Investments, Real Estate Land Speculation, Public Security Investments, Land owner Prior Political Experience: Author of Virginia Bill of Rights, State Lower House of Virginia 1776-1780, 1786-1787, Virginia State Constitutional Convention 1776 Committee Assignments: First Committee of Representation, Committee of Assumption of State Debts, Committee of Trade, Chairman Committee of Economy, Frugality, and Manufactures Convention Contributions: Arrived May 25 and was present through the signing of the Constitution, however he did not sign the Constitution. Initially Mason advocated a stronger central government but withdrew his support toward the end of the deliberations. He argued that the Constitution inadequately represented the interests of the people and the States and that the new government will “produce a monarchy, or a corrupt, tyrannical aristocracy.” William Pierce stated that “he is able and convincing in debate, steady and firm in his principles, and undoubtedly one of the best politicians in America.” He kept notes of the debates at the Convention. New Government Participation: He attended the ratification convention of Virginia where he opposed the ratification of the Constitution. Did not serve in the new Federal Government. Biography from the National Archives: In 1725 George Mason was born to George and Ann Thomson Mason. When the boy was 10 years old his father died, and young George’s upbringing was left in the care of his uncle, John Mercer. The future jurist’s education was profoundly shaped by the contents of his uncle’s 1500-volume library, one-third of which concerned the law. Mason established himself as an important figure in his community. As owner of Gunston Hall he was one of the richest planters in Virginia. In 1750 he married Anne Eilbeck, and in 23 years of marriage they had five sons and four daughters. In 1752 he acquired an interest in the Ohio Company, an organization that speculated in western lands. When the crown revoked the company’s rights in 1773, Mason, the company’s treasurer, wrote his first major state paper, Extracts from the Virginia Charters, with Some Remarks upon Them. During these years Mason also pursued his political interests. He was a justice of the Fairfax County court, and between 1754 and 1779 Mason was a trustee of the city of Alexandria. In 1759 he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. When the Stamp Act of 1765 aroused outrage in the colonies, George Mason wrote an open letter explaining the colonists’ position to a committee of London merchants to enlist their support. In 1774 Mason again was in the forefront of political events when he assisted in drawing up the Fairfax Resolves, a document that outlined the colonists’ constitutional grounds for their objections to the Boston Port Act. Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, framed by Mason in 1776, was widely copied in other colonies, served as a model for Jefferson in the first part of the Declaration of Independence, and was the basis for the federal Constitution’s Bill of Rights. The years between 1776 and 1780 were filled with great legislative activity. The establishment of a government independent of Great Britain required the abilities of persons such as George Mason. He supported the disestablishment of the church and was active in the organization of military affairs, especially in the West. The influence of his early work, Extracts from the Virginia Charters, is seen in the 1783 peace treaty with Great Britain, which fixed the Anglo-American boundary at the Great Lakes instead of the Ohio River. After independence, Mason drew up the plan for Virginia’s cession of its western lands to the United States. By the early 1780s, however, Mason grew disgusted with the conduct of public affairs and retired. He married his second wife, Sarah Brent, in 1780. In 1785 he attended the Mount Vernon meeting that was a prelude to the Annapolis convention of 1786, but, though appointed, he did not go to Annapolis. At Philadelphia in 1787 Mason was one of the five most frequent speakers at the Constitutional Convention. He exerted great influence, but during the last two weeks of the convention he decided not to sign the document. Mason’s refusal prompts some surprise, especially since his name is so closely linked with constitutionalism. He explained his reasons at length, citing the absence of a declaration of rights as his primary concern. He then discussed the provisions of the Constitution point by point, beginning with the House of Representatives. The House he criticized as not truly representative of the nation, the Senate as too powerful. He also claimed that the power of the federal judiciary would destroy the state judiciaries, render justice unattainable, and enable the rich to oppress and ruin the poor. These fears led Mason to conclude that the new government was destined to either become a monarchy or fall into the hands of a corrupt, oppressive aristocracy. Two of Mason’s greatest concerns were incorporated into the Constitution. The Bill of Rights answered his primary objection, and the 11th amendment addressed his call for strictures on the judiciary. Throughout his career Mason was guided by his belief in the rule of reason and in the centrality of the natural rights of man. He approached problems coolly, rationally, and impersonally. In recognition of his accomplishments and dedication to the principles of the Age of Reason, Mason has been called the American manifestation of the Enlightenment. Mason died on October 7, 1792, and was buried on the grounds of Gunston Hall.  State: New York (Born in British West Indies, immigrated 1772) Age at Convention: 30 Date of Birth: January 11, 1757 Date of Death: July 12, 1804 Schooling: Attended Kings College (Columbia) Occupation: Lawyer, Public Security Interests, Real Estate, Land Speculation, Soldier Prior Political Experience: Confederation Congress 1782-1783, Represented New York at Annapolis Convention 1786, Lower State Legislature of New York 1787 Committee Assignments: Committee of Rules, Committee of Style Convention Contributions: Arrived May 25, departed June 30, and except for one day, August 13, he was absent until September 6. Upon his return he remained present through the signing of the Constitution. His most important contribution was the introduction and defense of the Hamilton plan on June 18, 1787, that argued neither the Virginia Plan nor the New Jersey Plan were adequate to the task at hand. William Pierce stated that “there is no skimming over the surface of a subject with him, he must sink to the bottom to see what foundation it rests on.” New Government Participation: Attended the New York ratifying convention and supported the ratification of the Constitution. President Washington nominated and the Senate confirmed Hamilton as the Secretary of the Treasury (1789 – 1796). He was the principle author of the Federalist Papers. Biography from the National Archives: Hamilton was born in 1757 on the island of Nevis, in the Leeward group, British West Indies. He was the illegitimate son of a common-law marriage between a poor itinerant Scottish merchant of aristocratic descent and an English-French Huguenot mother who was a planter’s daughter. In 1766, after the father had moved his family elsewhere in the Leewards to St. Croix in the Danish (now United States) Virgin Islands, he returned to St. Kitts while his wife and two sons remained on St. Croix. The mother, who opened a small store to make ends meet, and a Presbyterian clergyman provided Hamilton with a basic education, and he learned to speak fluent French. About the time of his mother’s death in 1768, he became an apprentice clerk at Christiansted in a mercantile establishment, whose proprietor became one of his benefactors. Recognizing his ambition and superior intelligence, they raised a fund for his education. In 1772, bearing letters of introduction, Hamilton traveled to New York City. Patrons he met there arranged for him to attend Barber’s Academy at Elizabethtown (present Elizabeth), NJ. During this time, he met and stayed for a while at the home of William Livingston, who would one day be a fellow signer of the Constitution. Late the next year, 1773, Hamilton entered King’s College (later Columbia College and University) in New York City, but the Revolution interrupted his studies. Although not yet 20 years of age, in 1774-75 Hamilton wrote several widely read pro-Whig pamphlets. Right after the war broke out, he accepted an artillery captaincy and fought in the principal campaigns of 1776-77. In the latter year, winning the rank of lieutenant colonel, he joined the staff of General Washington as secretary and aide-de-camp and soon became his close confidant as well. In 1780 Hamilton wed New Yorker Elizabeth Schuyler, whose family was rich and politically powerful; they were to have eight children. In 1781, after some disagreements with Washington, he took a command position under Lafayette in the Yorktown, VA, campaign (1781). He resigned his commission that November. Hamilton then read law at Albany and quickly entered practice, but public service soon attracted him. He was elected to the Continental Congress in 1782-83. In the latter year, he established a law office in New York City. Because of his interest in strengthening the central government, he represented his state at the Annapolis Convention in 1786, where he urged the calling of the Constitutional Convention. In 1787 Hamilton served in the legislature, which appointed him as a delegate to the convention. He played a surprisingly small part in the debates, apparently because he was frequently absent on legal business, his extreme nationalism put him at odds with most of the delegates, and he was frustrated by the conservative views of his two fellow delegates from New York. He did, however, sit on the Committee of Style, and he was the only one of the three delegates from his state who signed the finished document. Hamilton’s part in New York’s ratification the next year was substantial, though he felt the Constitution was deficient in many respects. Against determined opposition, he waged a strenuous and successful campaign, including collaboration with John Jay and James Madison in writing The Federalist. In 1787 Hamilton was again elected to the Continental Congress. When the new government got under way in 1789, Hamilton won the position of Secretary of the Treasury. He began at once to place the nation’s disorganized finances on a sound footing. In a series of reports (1790-91), he presented a program not only to stabilize national finances but also to shape the future of the country as a powerful, industrial nation. He proposed establishment of a national bank, funding of the national debt, assumption of state war debts, and the encouragement of manufacturing. Hamilton’s policies soon brought him into conflict with Jefferson and Madison. Their disputes with him over his pro-business economic program, sympathies for Great Britain, disdain for the common man, and opposition to the principles and excesses of the French revolution contributed to the formation of the first U.S. party system. It pitted Hamilton and the Federalists against Jefferson and Madison and the Democratic-Republicans. During most of the Washington administration, Hamilton’s views usually prevailed with the President, especially after 1793 when Jefferson left the government. In 1795 family and financial needs forced Hamilton to resign from the Treasury Department and resume his law practice in New York City. Except for a stint as inspector-general of the Army (1798-1800) during the undeclared war with France, he never again held public office. While gaining stature in the law, Hamilton continued to exert a powerful impact on New York and national politics. Always an opponent of fellow-Federalist John Adams, he sought to prevent his election to the presidency in 1796. When that failed, he continued to use his influence secretly within Adams’ cabinet. The bitterness between the two men became public knowledge in 1800 when Hamilton denounced Adams in a letter that was published through the efforts of the Democratic-Republicans. In 1802 Hamilton and his family moved into The Grange, a country home he had built in a rural part of Manhattan not far north of New York City. But the expenses involved and investments in northern land speculations seriously strained his finances. Meanwhile, when Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in Presidential electoral votes in 1800, Hamilton threw valuable support to Jefferson. In 1804, when Burr sought the governorship of New York, Hamilton again managed to defeat him. That same year, Burr, taking offense at remarks he believed to have originated with Hamilton, challenged him to a duel, which took place at present Weehawken, NJ, on July 11. Mortally wounded, Hamilton died the next day. He was in his late forties at death. He was buried in Trinity Churchyard in New York City. State: New York Age at Ratifying Convention: 42 Affiliation: Federalist Nom de Plume: Publius (with Madison and Hamilton) Vote at Ratifying Convention: Yea Date of Birth: December 12, 1745 Date of Death: May 17, 1829 Schooling: King’s College (Columbia) Occupation: Attorney, Judge Prior Political Experience: Delegate to the First Continental Congress, 1774; Delegate to the Second Continental Congress; New York Provincial Congress; Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court, 1777-1778; United States Secretary of Foreign Affairs, 1784-1790 Other Political Activities: Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, 1790-1795; Governor of New York, 1795-1800 If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website. If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked. To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser. Course: US history > Unit 3- The Articles of Confederation

- What was the Articles of Confederation?

- Shays's Rebellion

- The Constitutional Convention

- The US Constitution

The Federalist Papers- The Bill of Rights

- Social consequences of revolutionary ideals

- The presidency of George Washington

- Why was George Washington the first president?

- The presidency of John Adams

- Regional attitudes about slavery, 1754-1800

- Continuity and change in American society, 1754-1800

- Creating a nation

- The Federalist Papers was a collection of essays written by John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton in 1788.

- The essays urged the ratification of the United States Constitution, which had been debated and drafted at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787.

- The Federalist Papers is considered one of the most significant American contributions to the field of political philosophy and theory and is still widely considered to be the most authoritative source for determining the original intent of the framers of the US Constitution.

The Articles of Confederation and Constitutional Convention- In Federalist No. 10 , Madison reflects on how to prevent rule by majority faction and advocates the expansion of the United States into a large, commercial republic.

- In Federalist No. 39 and Federalist 51 , Madison seeks to “lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty,” emphasizing the need for checks and balances through the separation of powers into three branches of the federal government and the division of powers between the federal government and the states. 4

- In Federalist No. 84 , Hamilton advances the case against the Bill of Rights, expressing the fear that explicitly enumerated rights could too easily be construed as comprising the only rights to which American citizens were entitled.

What do you think?- For more on Shays’s Rebellion, see Leonard L. Richards, Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Bernard Bailyn, ed. The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Anti-Federalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle over Ratification; Part One, September 1787 – February 1788 (New York: Penguin Books, 1993).

- See Federalist No. 1 .

- See Federalist No. 51 .

- For more, see Michael Meyerson, Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

Want to join the conversation?- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Federalist papers summaryFederalist papers , formally The Federalist , Eighty-five essays on the proposed Constitution of the United States and the nature of republican government, published in 1787–88 by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay in an effort to persuade voters of New York state to support ratification. Most of the essays first appeared serially in New York newspapers; they were reprinted in other states and then published as a book in 1788. A few of the essays were issued separately later. All were signed “Publius.” They presented a masterly exposition of the federal system and the means of attaining the ideals of justice, general welfare, and the rights of individuals.  The Federalist PapersAppearing in New York newspapers as the New York Ratification Convention met in Poughkeepsie, John Jay, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison wrote as Publius and addressed the citizens of New York through the Federalist Papers. These essays subsequently circulated and were reprinted throughout the states as the Ratification process unfolded in other states. Initially appearing as individual items in several New York newspapers, all eighty-five essays were eventually combined and published as The Federalist . Click here to view a chronology of the Printing and Reprintings of The Federalist . Considerable debate has surrounded these essays since their publication. Many suggest they represent the best exposition of the Constitution to date. Their conceptual design would affirm this view. Others contend that they were mere propaganda to allay fears of the opposition to the Constitution. Regardless, they are often included in the canon of the world’s great political writings. A complete introduction exploring the purpose, authorship, circulation, and reactions to The Federalist can be found here. General Introduction- No. 1 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 27 October 1787

Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence- No. 2 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 31 October 1787

- No. 3 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 3 November 1787

- No. 4 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 7 November 1787

- No. 5 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 10 November 1787

Concerning Dangers from Dissensions Between the States- No. 6 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 14 November 1787

- No. 7 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 17 November 1787

- No. 8 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 20 November 1787

- No. 9 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 21 November 1787

The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection- No. 10 (Madison) New York Daily Advertiser , 22 November 1787

The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy- No. 11 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 24 November 1787

The Utility of the Union in Respect to Revenue- No. 12 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 27 November 1787

Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government- No. 13 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 28 November 1787

Objections to the Proposed Constitution from Extent of Territory Answered- No. 14 (Madison) New York Packet , 30 November 1787

The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union- No. 15 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 1 December 1787

- No. 16 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 4 December 1787

- No. 17 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 5 December 1787

- No. 18 (Madison with Hamilton) New York Packet , 7 December 1787

- No. 19 (Madison with Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 8 December 1787

- No. 20 (Madison with Hamilton) New York Packet , 11 December 1787

- No. 21 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 12 December 1787

- No. 22 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 14 December 1787

The Necessity of Energetic Government to Preserve of the Union- No. 23 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 18 December 1787

Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered- No. 24 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 19 December 1787

- No. 25 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 21 December 1787

Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense- No. 26 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 22 December 1787

- No. 27 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 25 December 1787

- No. 28 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 26 December 1787

Concerning the Militia- No. 29 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 9 January 1788

Concerning the General Power of Taxation- No. 30 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 28 December 1787

- No. 31 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 1 January 1788

- Nos. 32–33 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 2 January 1788

- No. 34 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 4 January 1788

- No. 35 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 5 January 1788

- No. 36 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 8 January 1788

The Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government- No. 37 (Madison) New York Daily Advertiser , 11 January 1788

- No. 38 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 12 January 1788

The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles- No. 39 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 16 January 1788

The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined- No. 40 (Madison) New York Packet , 18 January 1788

General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution- No. 41 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 19 January 1788

- No. 42 (Madison) New York Packet , 22 January 1788

- No. 43 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 23 January 1788

Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States- No. 44 (Madison) New York Packet , 25 January 1788

Alleged Danger from the Powers of the Union to the State Governments- No. 45 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 26 January 1788

Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared- No. 46 (Madison) New York Packet , 29 January 1788

Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Powers- No. 47 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 30 January 1788

Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated- No. 48 (Madison) New York Packet , 1 February 1788

Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government- No. 49 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 2 February 1788

Periodic Appeals to the People Considered- No. 50 (Madison) New York Packet , 5 February 1788

Structure of Government Must Furnish Proper Checks and Balances- No. 51 (Madison) New York Independent Journal , 6 February 1788

The House of Representatives- No. 52 (Madison?) New York Packet , 8 February 1788

- No. 53 (Madison or Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 9 February 1788

The Apportionment of Members Among the States- No. 54 (Madison) New York Packet , 12 February 1788

The Total Number of the House of Representatives- No. 55 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 13 February 1788

- No. 56 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 16 February 1788

The Alleged Tendency of the Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many- No. 57 (Madison?) New York Packet , 19 February 1788

Objection That the Numbers Will Not Be Augmented as Population Increases- No. 58 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 20 February 1788

Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members- No. 59 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 22 February 1788

- No. 60 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 23 February 1788

- No. 61 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 26 February 1788

- No. 62 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 27 February 1788

- No. 63 (Madison?) New York Independent Journal , 1 March 1788

- No. 64 (Jay) New York Independent Journal , 5 March 1788

- No. 65 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 7 March 1788

Objections to the Power of the Senate to Set as a Court for Impeachments- No. 66 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 8 March 1788

The Executive Department- No. 67 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 11 March 1788

The Mode of Electing the President- No. 68 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 12 March 1788

The Real Character of the Executive- No. 69 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 14 March 1788

The Executive Department Further Considered- No. 70 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 15 March 1788

The Duration in Office of the Executive- No. 71 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 18 March 1788

Re-Eligibility of the Executive Considered- No. 72 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 19 March 1788

Provision for The Support of the Executive, and the Veto Power- No. 73 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 21 March 1788

The Command of the Military and Naval Forces, and the Pardoning Power- No. 74 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 25 March 1788

The Treaty Making Power of the Executive- No. 75 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 26 March 1788

The Appointing Power of the Executive- No. 76 (Hamilton) New York Packet , 1 April 1788

Appointing Power and Other Powers of the Executive Considered- No. 77 (Hamilton) New York Independent Journal , 2 April 1788

The Judiciary Department- No. 78 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

- No. 79 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Powers of the Judiciary- No. 80 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Judiciary Continued, and the Distribution of the Judicial Authority- No. 81 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Judiciary Continued- No. 82 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

The Judiciary Continued in Relation to Trial by Jury- No. 83 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered- No. 84 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

Concluding Remarks- No. 85 (Hamilton) Book Edition, Volume II, 28 May 1788

Explore the ConstitutionThe constitution. Dive DeeperConstitution 101 course. - The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town HallWatch videos of recent programs. Constitution 101 Curriculum- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets