45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Human Rights: Samples in 500 and 1500

- Updated on

- Jun 20, 2024

Essay writing is an integral part of the school curriculum and various academic and competitive exams like IELTS , TOEFL , SAT , UPSC , etc. It is designed to test your command of the English language and how well you can gather your thoughts and present them in a structure with a flow. To master your ability to write an essay, you must read as much as possible and practise on any given topic. This blog brings you a detailed guide on how to write an essay on Human Rights , with useful essay samples on Human rights.

This Blog Includes:

The basic human rights, 200 words essay on human rights, 500 words essay on human rights, 500+ words essay on human rights in india, 1500 words essay on human rights, importance of human rights, essay on human rights pdf, what are human rights.

Human rights mark everyone as free and equal, irrespective of age, gender, caste, creed, religion and nationality. The United Nations adopted human rights in light of the atrocities people faced during the Second World War. On the 10th of December 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Its adoption led to the recognition of human rights as the foundation for freedom, justice and peace for every individual. Although it’s not legally binding, most nations have incorporated these human rights into their constitutions and domestic legal frameworks. Human rights safeguard us from discrimination and guarantee that our most basic needs are protected.

Also Read: Essay on Yoga Day

Also Read: Speech on Yoga Day

Before we move on to the essays on human rights, let’s check out the basics of what they are.

Also Read: What are Human Rights?

Also Read: 7 Impactful Human Rights Movies Everyone Must Watch!

Here is a 200-word short sample essay on basic Human Rights.

Human rights are a set of rights given to every human being regardless of their gender, caste, creed, religion, nation, location or economic status. These are said to be moral principles that illustrate certain standards of human behaviour. Protected by law , these rights are applicable everywhere and at any time. Basic human rights include the right to life, right to a fair trial, right to remedy by a competent tribunal, right to liberty and personal security, right to own property, right to education, right of peaceful assembly and association, right to marriage and family, right to nationality and freedom to change it, freedom of speech, freedom from discrimination, freedom from slavery, freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of movement, right of opinion and information, right to adequate living standard and freedom from interference with privacy, family, home and correspondence.

Also Read: Law Courses

Check out this 500-word long essay on Human Rights.

Every person has dignity and value. One of the ways that we recognise the fundamental worth of every person is by acknowledging and respecting their human rights. Human rights are a set of principles concerned with equality and fairness. They recognise our freedom to make choices about our lives and develop our potential as human beings. They are about living a life free from fear, harassment or discrimination.

Human rights can broadly be defined as the basic rights that people worldwide have agreed are essential. These include the right to life, the right to a fair trial, freedom from torture and other cruel and inhuman treatment, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the right to health, education and an adequate standard of living. These human rights are the same for all people everywhere – men and women, young and old, rich and poor, regardless of our background, where we live, what we think or believe. This basic property is what makes human rights’ universal’.

Human rights connect us all through a shared set of rights and responsibilities. People’s ability to enjoy their human rights depends on other people respecting those rights. This means that human rights involve responsibility and duties towards other people and the community. Individuals have a responsibility to ensure that they exercise their rights with consideration for the rights of others. For example, when someone uses their right to freedom of speech, they should do so without interfering with someone else’s right to privacy.

Governments have a particular responsibility to ensure that people can enjoy their rights. They must establish and maintain laws and services that enable people to enjoy a life in which their rights are respected and protected. For example, the right to education says that everyone is entitled to a good education. Therefore, governments must provide good quality education facilities and services to their people. If the government fails to respect or protect their basic human rights, people can take it into account.

Values of tolerance, equality and respect can help reduce friction within society. Putting human rights ideas into practice can help us create the kind of society we want to live in. There has been tremendous growth in how we think about and apply human rights ideas in recent decades. This growth has had many positive results – knowledge about human rights can empower individuals and offer solutions for specific problems.

Human rights are an important part of how people interact with others at all levels of society – in the family, the community, school, workplace, politics and international relations. Therefore, people everywhere must strive to understand what human rights are. When people better understand human rights, it is easier for them to promote justice and the well-being of society.

Also Read: Important Articles in Indian Constitution

Here is a human rights essay focused on India.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. It has been rightly proclaimed in the American Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Created with certain unalienable rights….” Similarly, the Indian Constitution has ensured and enshrined Fundamental rights for all citizens irrespective of caste, creed, religion, colour, sex or nationality. These basic rights, commonly known as human rights, are recognised the world over as basic rights with which every individual is born.

In recognition of human rights, “The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was made on the 10th of December, 1948. This declaration is the basic instrument of human rights. Even though this declaration has no legal bindings and authority, it forms the basis of all laws on human rights. The necessity of formulating laws to protect human rights is now being felt all over the world. According to social thinkers, the issue of human rights became very important after World War II concluded. It is important for social stability both at the national and international levels. Wherever there is a breach of human rights, there is conflict at one level or the other.

Given the increasing importance of the subject, it becomes necessary that educational institutions recognise the subject of human rights as an independent discipline. The course contents and curriculum of the discipline of human rights may vary according to the nature and circumstances of a particular institution. Still, generally, it should include the rights of a child, rights of minorities, rights of the needy and the disabled, right to live, convention on women, trafficking of women and children for sexual exploitation etc.

Since the formation of the United Nations , the promotion and protection of human rights have been its main focus. The United Nations has created a wide range of mechanisms for monitoring human rights violations. The conventional mechanisms include treaties and organisations, U.N. special reporters, representatives and experts and working groups. Asian countries like China argue in favour of collective rights. According to Chinese thinkers, European countries lay stress upon individual rights and values while Asian countries esteem collective rights and obligations to the family and society as a whole.

With the freedom movement the world over after World War II, the end of colonisation also ended the policy of apartheid and thereby the most aggressive violation of human rights. With the spread of education, women are asserting their rights. Women’s movements play an important role in spreading the message of human rights. They are fighting for their rights and supporting the struggle for human rights of other weaker and deprived sections like bonded labour, child labour, landless labour, unemployed persons, Dalits and elderly people.

Unfortunately, violation of human rights continues in most parts of the world. Ethnic cleansing and genocide can still be seen in several parts of the world. Large sections of the world population are deprived of the necessities of life i.e. food, shelter and security of life. Right to minimum basic needs viz. Work, health care, education and shelter are denied to them. These deprivations amount to the negation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Also Read: Human Rights Courses

Check out this detailed 1500-word essay on human rights.

The human right to live and exist, the right to equality, including equality before the law, non-discrimination on the grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth, and equality of opportunity in matters of employment, the right to freedom of speech and expression, assembly, association, movement, residence, the right to practice any profession or occupation, the right against exploitation, prohibiting all forms of forced labour, child labour and trafficking in human beings, the right to freedom of conscience, practice and propagation of religion and the right to legal remedies for enforcement of the above are basic human rights. These rights and freedoms are the very foundations of democracy.

Obviously, in a democracy, the people enjoy the maximum number of freedoms and rights. Besides these are political rights, which include the right to contest an election and vote freely for a candidate of one’s choice. Human rights are a benchmark of a developed and civilised society. But rights cannot exist in a vacuum. They have their corresponding duties. Rights and duties are the two aspects of the same coin.

Liberty never means license. Rights presuppose the rule of law, where everyone in the society follows a code of conduct and behaviour for the good of all. It is the sense of duty and tolerance that gives meaning to rights. Rights have their basis in the ‘live and let live’ principle. For example, my right to speech and expression involves my duty to allow others to enjoy the same freedom of speech and expression. Rights and duties are inextricably interlinked and interdependent. A perfect balance is to be maintained between the two. Whenever there is an imbalance, there is chaos.

A sense of tolerance, propriety and adjustment is a must to enjoy rights and freedom. Human life sans basic freedom and rights is meaningless. Freedom is the most precious possession without which life would become intolerable, a mere abject and slavish existence. In this context, Milton’s famous and oft-quoted lines from his Paradise Lost come to mind: “To reign is worth ambition though in hell/Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven.”

However, liberty cannot survive without its corresponding obligations and duties. An individual is a part of society in which he enjoys certain rights and freedom only because of the fulfilment of certain duties and obligations towards others. Thus, freedom is based on mutual respect’s rights. A fine balance must be maintained between the two, or there will be anarchy and bloodshed. Therefore, human rights can best be preserved and protected in a society steeped in morality, discipline and social order.

Violation of human rights is most common in totalitarian and despotic states. In the theocratic states, there is much persecution, and violation in the name of religion and the minorities suffer the most. Even in democracies, there is widespread violation and infringement of human rights and freedom. The women, children and the weaker sections of society are victims of these transgressions and violence.

The U.N. Commission on Human Rights’ main concern is to protect and promote human rights and freedom in the world’s nations. In its various sessions held from time to time in Geneva, it adopts various measures to encourage worldwide observations of these basic human rights and freedom. It calls on its member states to furnish information regarding measures that comply with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights whenever there is a complaint of a violation of these rights. In addition, it reviews human rights situations in various countries and initiates remedial measures when required.

The U.N. Commission was much concerned and dismayed at the apartheid being practised in South Africa till recently. The Secretary-General then declared, “The United Nations cannot tolerate apartheid. It is a legalised system of racial discrimination, violating the most basic human rights in South Africa. It contradicts the letter and spirit of the United Nations Charter. That is why over the last forty years, my predecessors and I have urged the Government of South Africa to dismantle it.”

Now, although apartheid is no longer practised in that country, other forms of apartheid are being blatantly practised worldwide. For example, sex apartheid is most rampant. Women are subject to abuse and exploitation. They are not treated equally and get less pay than their male counterparts for the same jobs. In employment, promotions, possession of property etc., they are most discriminated against. Similarly, the rights of children are not observed properly. They are forced to work hard in very dangerous situations, sexually assaulted and exploited, sold and bonded for labour.

The Commission found that religious persecution, torture, summary executions without judicial trials, intolerance, slavery-like practices, kidnapping, political disappearance, etc., are being practised even in the so-called advanced countries and societies. The continued acts of extreme violence, terrorism and extremism in various parts of the world like Pakistan, India, Iraq, Afghanistan, Israel, Somalia, Algeria, Lebanon, Chile, China, and Myanmar, etc., by the governments, terrorists, religious fundamentalists, and mafia outfits, etc., is a matter of grave concern for the entire human race.

Violation of freedom and rights by terrorist groups backed by states is one of the most difficult problems society faces. For example, Pakistan has been openly collaborating with various terrorist groups, indulging in extreme violence in India and other countries. In this regard the U.N. Human Rights Commission in Geneva adopted a significant resolution, which was co-sponsored by India, focusing on gross violation of human rights perpetrated by state-backed terrorist groups.

The resolution expressed its solidarity with the victims of terrorism and proposed that a U.N. Fund for victims of terrorism be established soon. The Indian delegation recalled that according to the Vienna Declaration, terrorism is nothing but the destruction of human rights. It shows total disregard for the lives of innocent men, women and children. The delegation further argued that terrorism cannot be treated as a mere crime because it is systematic and widespread in its killing of civilians.

Violation of human rights, whether by states, terrorists, separatist groups, armed fundamentalists or extremists, is condemnable. Regardless of the motivation, such acts should be condemned categorically in all forms and manifestations, wherever and by whomever they are committed, as acts of aggression aimed at destroying human rights, fundamental freedom and democracy. The Indian delegation also underlined concerns about the growing connection between terrorist groups and the consequent commission of serious crimes. These include rape, torture, arson, looting, murder, kidnappings, blasts, and extortion, etc.

Violation of human rights and freedom gives rise to alienation, dissatisfaction, frustration and acts of terrorism. Governments run by ambitious and self-seeking people often use repressive measures and find violence and terror an effective means of control. However, state terrorism, violence, and human freedom transgressions are very dangerous strategies. This has been the background of all revolutions in the world. Whenever there is systematic and widespread state persecution and violation of human rights, rebellion and revolution have taken place. The French, American, Russian and Chinese Revolutions are glowing examples of human history.

The first war of India’s Independence in 1857 resulted from long and systematic oppression of the Indian masses. The rapidly increasing discontent, frustration and alienation with British rule gave rise to strong national feelings and demand for political privileges and rights. Ultimately the Indian people, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, made the British leave India, setting the country free and independent.

Human rights and freedom ought to be preserved at all costs. Their curtailment degrades human life. The political needs of a country may reshape Human rights, but they should not be completely distorted. Tyranny, regimentation, etc., are inimical of humanity and should be resisted effectively and united. The sanctity of human values, freedom and rights must be preserved and protected. Human Rights Commissions should be established in all countries to take care of human freedom and rights. In cases of violation of human rights, affected individuals should be properly compensated, and it should be ensured that these do not take place in future.

These commissions can become effective instruments in percolating the sensitivity to human rights down to the lowest levels of governments and administrations. The formation of the National Human Rights Commission in October 1993 in India is commendable and should be followed by other countries.

Also Read: Law Courses in India

Human rights are of utmost importance to seek basic equality and human dignity. Human rights ensure that the basic needs of every human are met. They protect vulnerable groups from discrimination and abuse, allow people to stand up for themselves, and follow any religion without fear and give them the freedom to express their thoughts freely. In addition, they grant people access to basic education and equal work opportunities. Thus implementing these rights is crucial to ensure freedom, peace and safety.

Human Rights Day is annually celebrated on the 10th of December.

Human Rights Day is celebrated to commemorate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the UNGA in 1948.

Some of the common Human Rights are the right to life and liberty, freedom of opinion and expression, freedom from slavery and torture and the right to work and education.

Popular Essay Topics

We hope our sample essays on Human Rights have given you some great ideas. For more information on such interesting blogs, visit our essay writing page and follow Leverage Edu .

Sonal is a creative, enthusiastic writer and editor who has worked extensively for the Study Abroad domain. She splits her time between shooting fun insta reels and learning new tools for content marketing. If she is missing from her desk, you can find her with a group of people cracking silly jokes or petting neighbourhood dogs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

45,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

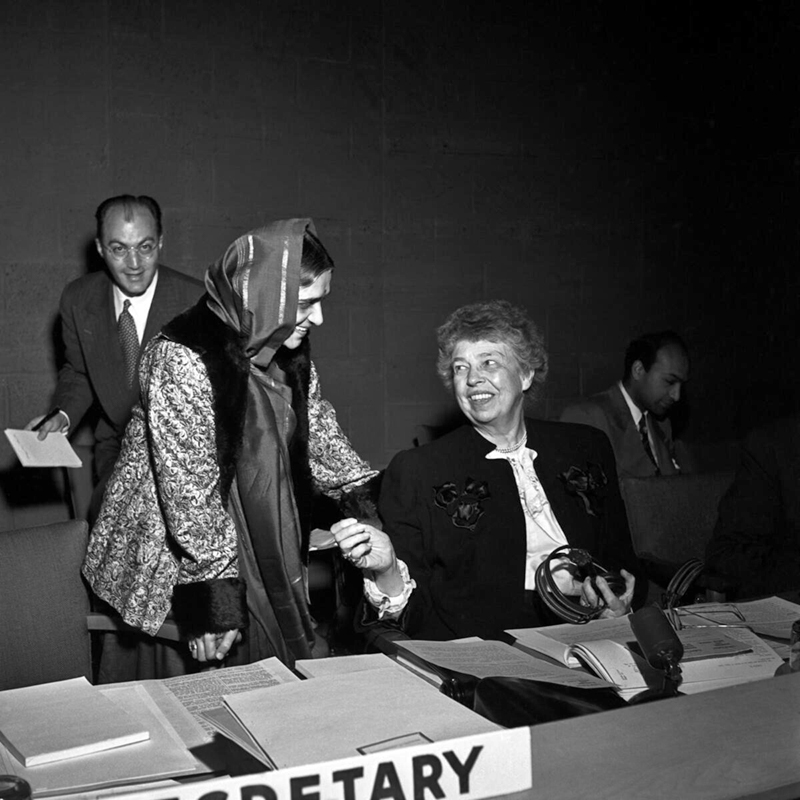

"Why Human Rights?": Reflection by Eleni Christou

This post is the first installment from UChicago Law's International Human Rights Law Clinic in a series titled — The Matter of Human Rights. In this 16-part series, law students examine, question and reflect on the historical, ideological, and normative roots of the human rights system, how the system has evolved, its present challenges and future possibilities. Eleni Christou is a third year in the Law School at the University of Chicago.

Why Human Rights?

By: Eleni Christou University of Chicago Law School Class of 2019

When the term “human rights” is used, it conjures up, for some, powerful images of the righteous fight for the inalienable rights that people have just by virtue of being human. It is Martin Luther King Jr. before the Washington monument as hundreds of thousands gather and look on; it is Nelson Mandela’s long walk to freedom; or a 16-year-old Malala telling her story, so others like her may be heard. But what is beyond these archetypes? Does the system work? Can we make it work better? Is it even the right system for our times? In other words, why human rights?

Human rights are rights that every person has from the moment they are born to the moment they die. They are things that everyone is entitled to, such as life, liberty, freedom of expression, and the right to education, just by virtue of being human. People can never lose these rights on the basis of age, sex, nationality, race, or disability. Human rights offer us a principled framework, rooted in normative values meant for all nations and legal orders. In a world order in which states/governments set the rules, the human rights regime is the counterweight, one concerned with and focused on the individual. In other words, we need human rights because it provides us a way of evaluating and challenging national laws and practices as to the treatment of individuals.

The foundational human right text for our modern-day system is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights . Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in December, 1948, this document lays out 30 articles which define the rights each human is entitled to. These rights are designed to protect core human values and prohibit institutions and practices that are contrary to the enjoyment of the rights. Rights often complement each other, and at times, can be combined to form new rights. For example, humans have a right to liberty, and also a right to be free from slavery, two rights which complement and reinforce each other. Other times, rights can be in tension, like when a person’s right to freedom of expression infringes upon another’s right to freedom from discrimination.

In this post, I’ll provide an example of how the human rights system has been used to do important work. The international communities’ work to develop the law and organize around human rights principles to challenge and sanction the apartheid regime in South Africa provides a valuable illustration of how the human rights system can be used successfully to alleviate state human rights violations that previously would have been written off as a domestic matter.

From 1948 to 1994, South Africa had a system of racial segregation called ‘ apartheid ,’ literally meaning ‘separateness.’ The minority white population was committing blatant human rights violations to maintain their control over the majority black population, and smaller multiethnic and South Asian communities. This system of apartheid was codified in laws at every level of the country, restricting where non-whites could live, work, and simply be. Non-whites were stripped of voting rights , evicted from their homes and forced into segregated neighborhoods, and not allowed to travel out of these neighborhoods without passes . Interracial marriage was forbidden, and transport and civil facilities were all segregated, leading to extremely inferior services for the majority of South Africans. The horrific conditions imposed on non-whites led to internal resistance movements , which the white ruling class responded to with extreme violence , leaving thousands dead or imprisoned by the government.

While certain global leaders expressed concern about the Apartheid regime in South Africa, at first, most (including the newly-formed UN) considered it a domestic affair. However, that view changed in 1960 following the Sharpeville Massacre , where 69 protesters of the travel pass requirement were murdered by South African police. In 1963, the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 181 , which called for a voluntary arms embargo against South Africa, which was later made mandatory. The Security Council condemned South Africa’s apartheid regime and encouraged states not to “indirectly [provide] encouragement . . . [of] South Africa to perpetuate, by force, its policy of apartheid,” by participating in the embargo. During this time, many countries, including the United States, ended their arms trade with South Africa. Additionally, the UN urged an oil embargo, and eventually suspended South Africa from the General Assembly in 1974.

In 1973, the UN General Assembly passed the International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid , and it came into force in 1976. This convention made apartheid a crime against humanity. It expanded the prohibition of apartheid and similar policies outside of the South African context, and laid the groundwork for international actions to be taken against any state that engaged in these policies. This also served to further legitimize the international response to South Africa’s apartheid regime.

As the state-sanctioned violence in South Africa intensified, and the global community came to understand the human rights violation being carried out on a massive scale, countries worked domestically to place trade sanctions on South Africa, and many divestment movements gained popular support. International sports teams refused to play in South Africa and cut ties with their sports federations, and many actors engaged in cultural boycotts. These domestic actions worked in tandem with the actions taken by the United Nations, mirroring the increasingly widespread ideology that human rights violations are a global issue that transcend national boundaries, but are an international concern of all peoples.

After years of domestic and international pressure, South African leadership released the resistance leader Nelson Mandela in 1990 and began negotiations for the dismantling of apartheid. In 1994, South Africa’s apartheid officially ended with the first general elections. With universal suffrage, Nelson Mandela was elected president.

In a speech to the UN General Assembly , newly elected Nelson Mandela recognized the role that the UN and individual countries played in the ending of apartheid, noting these interventions were a success story of the human rights system. The human rights values embodied in the UDHR, the ICSPCA, and numerous UN Security Council resolutions, provided an external normative and legal framework by which the global community could identify unlawful state action and hold South Africa accountable for its system of apartheid. The international pressure applied via the human rights system has been considered a major contributing factor to the end of apartheid. While the country has not fully recovered from the trauma that decades of the apartheid regime had left on its people, the end of the apartheid formal legal system has allowed the country to begin to heal and move towards a government that works for all people, one that has openly embraced international human rights law and principles in its constitutional and legislative framework.

This is what a human rights system can do. When state governments and legal orders fail to protect people within their control, the international system can challenge the national order and demand it uphold a basic standard of good governance. Since the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the human rights system has grown, tackled new challenges, developed institutions for review and enforcement, and built a significant body of law. Numerous tools have been established to help states, groups, and individuals defend and protect human rights.

So why human rights? Because the human rights system has been a powerful force for good in this world, often the only recourse for marginalized and minority populations. We, as the global community, should work to identify shortcomings in the system, and work together to improve and fix them. We should not — as the US has been doing under the current administration — selectively withdraw, defund, and disparage one of the only tools available to the world’s most vulnerable peoples. The human rights system is an arena, a language, and a source of power to many around the world fighting for a worthwhile future built on our shared human values.

Related Articles

Pozen center 2022-23 director's report, interracial marriage under attack: thinking the unthinkable, read: "the politics of torture" by kathleen cavanaugh, read "democracies and international law" by tom ginsburg, read "agents of change: political philosophy in practice" by ben laurence.

Join our mailing list to receive a weekly digest of Pozen-related news, opportunities, and events.

© 2023 Pozen Family Center for Human Rights | Accessibility | Colophon

- Support Our Work

- Carr Center Advisory Board

- Global LGBTQI+ Human Rights Program Founders

- Technology & Human Rights

- Racial Justice

- Global LGBTQI+ Human Rights

- Transitional Justice

- Human Rights Defenders

- Reimagining Rights & Responsibilities

- In Conversation

- Justice Matters Podcast

- News and Announcements

- Student Opportunities

- Fellowship Opportunities

Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

The Carr Center for Human Rights Policy serves as the hub of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research, teaching, and training in the human rights domain. The center embraces a dual mission: to educate students and the next generation of leaders from around the world in human rights policy and practice; and to convene and provide policy-relevant knowledge to international organizations, governments, policymakers, and businesses.

About the Carr Center

Since its founding in 1999, the Carr Center has dedicated the last quarter-century to human rights policy.

August 27, 2024 Become a Student Ambassador at the Carr Center

August 01, 2024 Announcing the Carr Center’s 2024–2025 Carr and Racial Justice Fellowship Cohorts Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

July 15, 2024 Announcing the Carr Center’s 2024–2025 “Surveillance Capitalism or Democracy” Fellowship Cohort Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

June 10, 2024 Celebrating Pride Month Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

September 05, 2024 Carr Center Annual Report 2023-24 Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

August 27, 2024 Algorithmic Discrimination in Latin American Welfare States Sebastian Smart

April 10, 2024 Global Anti-Blackness and the Legacy of the Transatlantic Slave Trade Carr Center for Human Rights Policy

April 18, 2024 Fostering Business Respect for Human Rights in AI Governance and Beyond

Moral Universalism and Human Rights as Politics

Michael Ignatieff discusses the state of human rights in the world today, moral universalism, and American exceptionalism.

A New Theory of Systemic Police Terrorism

Charity Clay discusses the importance of Black spaces and place-making and her theory on systemic police terrorism.

See All Justice Matters Episodes

View and listen to all of the Justice Matters podcast episodes in one place.

Dismantling the Global Anti-LGBTQI Movement

Kristopher Velasco, Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Princeton University, discusses the dangers of the global anti-LGBTQI movement.

Racial Justice Without Borders

Desirée Cormier Smith, Special Representative for Racial Equity and Justice for the U.S. State Department, discusses combatting worldwide structural racism, discrimination, and xenophobia.

The Importance of Inclusivity in Business

Jessica Yamoah, CEO and Founder of Innovate Inc., discusses why diversity and inclusion matters at the intersection of business, entrepreneurship, and technology.

Poetry as a Means of Defending Human Rights in Uganda

Danson Kahyana discusses the current political situation and the backlash he has faced in response to his work in Uganda.

Reversing the Global Backlash Against LGBTQI+ Rights

Diego Garcia Blum discusses advocating for the safety and acceptance of LGBTQI+ individuals, as well as the state of anti-LGBTQI+ legislation across the globe.

Reflections on Decades of the Racial Justice Movement

Gay McDougall discusses her decades of work on the frontlines of race, gender, and economic exploitation.

“The Carr Center is building a bridge between ideas on human rights and the practice on the ground—and right now we're at a critical juncture around the world.”

Mathias risse, faculty director.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Origins in ancient Greece and Rome

- Natural law transformed into natural rights

- “Nonsense upon stilts”: the critics of natural rights

- The persistence of the notion

- The nature of human rights: commonly accepted postulates

- Liberté : civil and political rights

- Égalité : economic, social, and cultural rights

- Fraternité : solidarity or group rights

- Liberté versus égalité

- The relevance of custom and tradition: the universalist-relativist debate

- Inherent risks in the debate

- Developments before World War II

- The UN Commission on Human Rights and its instruments

- The UN Human Rights Council and its instruments

- Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Its Optional Protocols

- Other UN human rights conventions and declarations

- Human rights and the Helsinki process

- Human rights in Europe

- Human rights in the Americas

- Human rights in Africa

- Human rights in the Arab world

- Human rights in Asia

- International human rights in domestic courts

- Human rights in the early 21st century

human rights

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- U. S. Department of State - Human Rights

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Human Rights

- The History Learning Site - Human Rights

- Cornell University Law School - Human rights

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Human Rights

- Social Sciences Libretexts - Human Rights

- human rights - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- human rights - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

human rights , rights that belong to an individual or group of individuals simply for being human, or as a consequence of inherent human vulnerability, or because they are requisite to the possibility of a just society. Whatever their theoretical justification, human rights refer to a wide continuum of values or capabilities thought to enhance human agency or protect human interests and declared to be universal in character, in some sense equally claimed for all human beings, present and future.

It is a common observation that human beings everywhere require the realization of diverse values or capabilities to ensure their individual and collective well-being. It also is a common observation that this requirement—whether conceived or expressed as a moral or a legal demand—is often painfully frustrated by social as well as natural forces, resulting in exploitation, oppression, persecution, and other forms of deprivation. Deeply rooted in these twin observations are the beginnings of what today are called “human rights” and the national and international legal processes associated with them.

Historical development

The expression human rights is relatively new, having come into everyday parlance only since World War II , the founding of the United Nations in 1945, and the adoption by the UN General Assembly of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. It replaced the phrase natural rights, which fell into disfavour in the 19th century in part because the concept of natural law (to which it was intimately linked) had become controversial with the rise of legal positivism . Legal positivism rejected the theory, long espoused by the Roman Catholic Church , that law must be moral to be law. The term human rights also replaced the later phrase the rights of Man, which was not universally understood to include the rights of women.

Most students of human rights trace the origins of the concept of human rights to ancient Greece and Rome , where it was closely tied to the doctrines of the Stoics , who held that human conduct should be judged according to, and brought into harmony with, the law of nature . A classic example of this view is given in Sophocles ’ play Antigone , in which the title character, upon being reproached by King Creon for defying his command not to bury her slain brother, asserted that she acted in accordance with the immutable laws of the gods.

In part because Stoicism played a key role in its formation and spread, Roman law similarly allowed for the existence of a natural law and with it—pursuant to the jus gentium (“law of nations”)—certain universal rights that extended beyond the rights of citizenship. According to the Roman jurist Ulpian , for example, natural law was that which nature, not the state, assures to all human beings, Roman citizens or not.

It was not until after the Middle Ages , however, that natural law became associated with natural rights. In Greco-Roman and medieval times, doctrines of natural law concerned mainly the duties, rather than the rights, of “Man.” Moreover, as evidenced in the writings of Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas , these doctrines recognized the legitimacy of slavery and serfdom and, in so doing, excluded perhaps the most important ideas of human rights as they are understood today—freedom (or liberty) and equality .

The conception of human rights as natural rights (as opposed to a classical natural order of obligation) was made possible by certain basic societal changes, which took place gradually beginning with the decline of European feudalism from about the 13th century and continuing through the Renaissance to the Peace of Westphalia (1648). During this period, resistance to religious intolerance and political and economic bondage; the evident failure of rulers to meet their obligations under natural law; and the unprecedented commitment to individual expression and worldly experience that was characteristic of the Renaissance all combined to shift the conception of natural law from duties to rights. The teachings of Aquinas and Hugo Grotius on the European continent, the Magna Carta (1215) and its companion Charter of the Forests (1217), the Petition of Right (1628), and the English Bill of Rights (1689) in England were signs of this change. Each testified to the increasingly popular view that human beings are endowed with certain eternal and inalienable rights that never were renounced when humankind “contracted” to enter the social order from the natural order and never were diminished by the claim of the “ divine right of kings .”

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Human Rights

Human rights are norms that aspire to protect all people everywhere from severe political, legal, and social abuses. Examples of human rights are the right to freedom of religion, the right to a fair trial when charged with a crime, the right not to be tortured, and the right to education. The philosophy of human rights addresses questions about the existence, content, nature, universality, justification, and legal status of human rights. The strong claims often made on behalf of human rights (for example, that they are universal, inalienable, or exist independently of legal enactment as justified moral norms) have frequently provoked skeptical doubts and countering philosophical defenses (on these doubts see Lacroix & Pranchère 2016; Mutua 2002; and Waldron 1987). Reflection on these doubts and the responses that can be made to them has become a sub-field of political and legal philosophy with a very substantial literature (see the extensive Bibliography below). This entry addresses the concept of human rights, the existence and grounds of human rights, the question of which rights are human rights, and relativism about human rights.

1. The General Idea of Human Rights

2.1 how can human rights exist, 2.2 justifications for human rights, 3.1 civil and political rights, 3.2 economic and social rights, 3.3 human rights of women, minorities, and groups, 3.4 new human rights, 4. universal human rights in a world of diverse beliefs and practices, a. books and articles in the philosophy of human rights, b. legal declarations, other internet resources, related entries.

This section attempts to explain the general idea of human rights by identifying four defining features. The goal is to answer the question of what human rights are with a description of the concept rather than with a list of specific rights. Two people can have the same general idea of human rights even though they disagree about which rights are really human rights and even about whether universal human rights are a good idea. The four-part explanation just below attempts to cover all kinds of human rights including both moral and legal human rights as well as old and new human rights (e.g., both Lockean natural rights and contemporary human rights). The explanation anticipates, however, that particular kinds of human rights will have additional features. Starting with this general concept does not commit us to treating all kinds of human rights in a single unified theory (see Buchanan 2013 for an argument that we should not attempt to theorize together universal moral rights and international legal human rights).

Human rights are rights . Lest we miss the obvious, human rights are rights (see Cruft 2012 and the entry on rights ). Rights focus on a freedom, protection, status, immunity, or benefit for the rightholders. Most human rights are claim rights that impose duties or responsibilities on their addressees or dutybearers. The duties associated with human rights often require actions involving respect, protection, facilitation, and provision. Although human rights are usually mandatory in the sense of imposing duties on specified parties, some legal human rights seem to do little more than declare high-priority goals and assign responsibility for their progressive realization. One can argue, of course, that goalish rights are not real rights, but it may be better to recognize that they comprise a weak but useful notion of a right. (See Beitz 2009 for a defense of the view that not all human rights are rights in a strong sense. Also, see Feinberg 1973 for the idea of “manifesto rights” and Nickel 2013 for a discussion of “rightslike goals”.)

Human rights are plural and come in lists . If someone accepted that there are human rights but held that there is only one of them, this might make sense if she meant that there is one abstract underlying right that generates a list of specific rights (see Dworkin 2011 for a view of this sort). But if this person meant that there is just one specific right such as the right to peaceful assembly this would be a highly revisionary view. Some philosophers advocate very short lists of human rights but nevertheless accept plurality (see Ignatieff 2004).

Human rights are universal . All living humans—or perhaps we should say all living persons —have human rights. One does not have to be a particular kind of person or a member of some specific nation or religion to have human rights. Included in the idea of universality is some conception of independent existence. People have human rights independently of whether such rights are present in the practices, morality, or law of their country or culture. This idea of universality needs several qualifications, however. First, some rights, such as the right to vote, are held only by adult citizens or residents and apply only to voting in one’s own country. Second, some rights can be suspended. For example, the human right to freedom of movement may be suspended temporarily during a riot or a wildfire. And third, some human rights treaties focus not on the rights of everyone but rather on the rights of specific groups such as minorities, women, indigenous peoples, and children.

Human rights have high-priority . Maurice Cranston held that human rights are matters of “paramount importance” and their violation “a grave affront to justice” (Cranston 1967: 51, 52). If human rights were not very important norms they would not have the ability to compete with other powerful considerations such as national stability and security, individual and national self-determination, and national and global prosperity. High priority does not mean, however, that human rights are absolute. As James Griffin says, human rights should be understood as “resistant to trade-offs, but not too resistant” (Griffin 2008: 77). Further, there seems to be priority variation among human rights. For example, the right to life is generally thought to have greater importance than the right to privacy; when the two conflict the right to privacy will generally be outweighed.

Let’s now consider four other features or functions that might be added to these four.

Should human rights be defined as inalienable? Inalienability does not mean that rights are absolute or can never be overridden by other considerations. Rather it means that its holder cannot lose it temporarily or permanently by bad conduct or by voluntarily giving it up. It is doubtful that all human rights are inalienable in this sense. One who endorses both human rights and imprisonment as punishment for serious crimes must hold that people’s rights to freedom of movement can be forfeited temporarily or permanently by just convictions of serious crimes. Perhaps it is sufficient to say that human rights are very hard to lose. (For a stronger view of inalienability, see Donnelly 1989 [2020] and Meyers 1985.)

Should human rights be defined as minimal rights? A number of philosophers have proposed the view that human rights are minimal in the sense of not being too numerous (a few dozen rights rather than hundreds or thousands), and not too demanding (see Joshua Cohen 2004 and Ignatieff 2004). Their views suggest that human rights are—or should be—more concerned with avoiding the worst than with achieving the best. Henry Shue suggests that human rights concern the “lower limits on tolerable human conduct” rather than “great aspirations and exalted ideals” (Shue 1996: ix). When human rights are modest standards they leave most legal and policy matters open to democratic decision-making at the national and local levels. This allows human rights to have high priority, to accommodate a great deal of cultural and institutional variation among countries, and to leave open a large space for democratic decision-making at the national level. Still, there is no contradiction in the idea of an extremely expansive list of human rights and hence minimalism is not a defining feature of human rights (for criticism of the view that human rights are minimal standards see Brems 2009; Etinson forthcoming; and Raz 2010). Minimalism is best seen as a normative prescription for what international human rights should be. Moderate forms of minimalism have considerable appeal as recommendations, but not as part of the definition of human rights.

Should human rights be defined as always being or “mirroring” moral rights? Philosophers coming to human rights theory from moral philosophy sometimes assume that human rights must be, at bottom, moral rather than legal rights. There is no contradiction, however, in people saying that they believe in human rights, but only when they are legal rights at the national or international levels. As Louis Henkin observed,

Political forces have mooted the principal philosophical objections, bridging the chasm between natural and positive law by converting natural human rights into positive legal rights. (Henkin 1978: 19)

It has also been suggested that legal human rights can be justified without directly appealing to any corresponding moral human right (see Buchanan 2013).

Should human rights be defined in terms of serving some sort of political function? Instead of seeing human rights as grounded in some sort of independently existing moral reality, a theorist might see them as the norms of a highly useful political practice that humans have constructed. Such a view would see the idea of human rights as playing various political roles at the national and international levels and as serving thereby to protect urgent human and national interests. These political roles might include providing standards for international evaluations of how governments treat their people and specifying when use of economic sanctions or military intervention is permissible. This kind of view may be plausible for the very salient international human rights that have emerged in international law and politics in the last fifty years. But human rights can exist and function in contexts not involving international scrutiny and intervention such as a world with only one state. Imagine, for example, that a massive asteroid strike makes New Zealand the only remaining state in existence. Surely the idea of human rights along with many dimensions of human rights practice could continue in New Zealand, even though there would be no international relations, law, or politics (for an argument of this sort see Tasioulas 2012a). And if in the same scenario a few people were discovered to have survived in Iceland and were living without a government or state, New Zealanders would know that human rights governed how these people should be treated even though they were stateless. How deeply the idea of human rights must be rooted in international law and practice should not be settled by definitional fiat. We can allow, however, that the sorts of political functions that Rawls and Beitz describe are typically served by international human rights today.

2 The Existence and Grounds of Human Rights

The most obvious way in which human rights exist is as norms of national and international law. At the international level, human rights norms exist because of treaties that have turned them into international law. For example, the human right not to be held in slavery or servitude in Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights and in Article 8 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights exists because these treaties establish it. At the national level, human rights norms exist because they have—through legislative enactment, judicial decision, or custom—become part of a country’s law. For example, the right against slavery exists in the United States because the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits slavery and servitude. When rights are embedded in international law, we are apt to speak of them as human rights; but when they are enacted in national law we more frequently describe them as civil or constitutional rights.

Although enactment in national and international law is one of the ways in which human rights exist, many have suggested that this is not the only way. If human rights exist only because of enactment, their availability is contingent on domestic and international political developments. Many people have looked for a way to support the idea that human rights have roots that are deeper and less subject to human decisions than legal enactment. One version of this idea is that people are born with rights, that human rights are somehow innate or inherent in human beings (see Morsink 2009). One way that a normative status could be inherent in humans is by being god-given. The American Declaration of Independence claims that people are “endowed by their Creator” with natural rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. On this view, god, the supreme lawmaker, enacted some basic human rights.

Rights plausibly attributed to divine decree must be very general and abstract (life, liberty, etc.) so that they can apply across thousands of years of human history, not just to recent centuries. But contemporary human rights are specific and many of them presuppose contemporary institutions (e.g., the right to a fair trial, the right to social security, and the right to education). Even if people are born with god-given natural rights, we need to explain how to get from those general and abstract rights to the specific rights found in contemporary declarations and treaties.

Attributing human rights to god’s commands may give them a secure status at the metaphysical level, but in a very diverse world it does not make them practically secure. Billions of people today do not believe in the god of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. If people do not believe in god, or in the sort of god that prescribes rights, then if you want to base human rights on theological beliefs you must persuade these people to accept a rights-supporting theological view. This is likely to be even harder than persuading them of human rights. Legal enactment at the national and international levels provides a far more secure status for practical purposes.

Human rights could also exist independently of legal enactment by being part of actual human moralities. All human groups seem to have moralities, that is, imperative norms of behavior backed by reasons and values. These moralities contain specific norms (for example, a prohibition on the intentional murder of innocent persons) and specific values (for example, valuing human life). One way in which human rights could exist apart from divine or human enactment is as norms accepted in almost all actual human moralities. If almost all human groups have moralities containing norms that prohibit murder, for example, these norms could constitute the human right to life.

This view is attractive but has serious difficulties. Although worldwide acceptance of human rights has increased in recent decades (see below section 4. Universal Human Rights in a World of Diverse Beliefs and Practices ), worldwide moral unanimity about human rights does not exist. Human rights declarations and treaties are intended to change existing norms, not just describe an existing moral consensus.

Yet another way of explaining the existence of human rights is to say that they exist most basically in true or justified ethical outlooks. On this account, to say that there is a human right against torture is mainly to assert that there are strong reasons for believing that it is always morally wrong to engage in torture and that protections should be provided against its practice. This approach would view the Universal Declaration as attempting to formulate a justified political morality: that is, as not merely trying to identify a preexisting moral consensus, but trying to create a consensus that could be supported by very plausible moral and practical reasons. This approach requires commitment to the objectivity of such reasons. It holds that just as there are reliable ways of finding out how the physical world works, or what makes buildings sturdy and durable, there are reliable ways of finding out what individuals may justifiably demand of each other and of governments. Even if unanimity about human rights is currently lacking, rational agreement is available to humans if they will commit themselves to open-minded and serious moral and political inquiry. If moral reasons exist independently of human construction, they can—when combined with premises about current institutions, problems, and resources—generate moral norms different from those currently accepted or enacted. The Universal Declaration seems to proceed on exactly this assumption (see Morsink 2009).

One problem with this view is that an existence based on good reasons seems a rather thin form of existence for human rights. But perhaps we can view this thinness as a practical rather than a theoretical problem—that is, as something to be remedied by the formulation and enactment of legal norms. The best form of existence for human rights would combine robust legal existence with the sort of moral existence that comes from being supported by strong moral and practical reasons.

Justifications for human rights should identify plausible starting points for defending the key features of human rights and offer an account of the transition from those starting points to a list of specific rights (see Nickel 2007). Further, justifying international human rights is likely to require additional steps (see Buchanan 2013). These requirements make the construction of a good justification a daunting task.

Recent attempts to justify human rights offer a dizzying variety of grounds. These include prudential reasons; linkage arguments (Shue 1996); agency and autonomy (Gewirth 1996; Griffin 2008); basic needs (D. Miller 2012); capabilities and positive freedom (Gould 2004; Nussbaum 2000; and Sen 2004) dignity (Gilabert 2018b; Kateb 2011, Tasioulas 2015); and fairness, status equality, and equal respect (Dworkin 2011; Buchanan 2013).

There is a lot of overlap between these approaches, but also important differences that are likely to make them yield different results. For example, an approach framed in terms of agency and autonomy will be more strongly and directly supportive of fundamental freedoms than one framed in terms of basic human needs. Justifications can be based on just one of these types of reasons or be pluralistic and appeal to several. Seeing so much diversity in philosophical approaches to justification may be discouraging (although great disagreement in approaches is common in philosophy) but its good side is that it suggests that there are at least several plausible ways of justifying human rights.

Philosophical justifications for human rights differ in how much credibility they attribute to contemporary lists of human rights, such as the one found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Some take fidelity to contemporary human rights practice as nearly imperative while others prioritize particular normative frameworks even if they can only justify some of the rights in contemporary lists.

Attempting to discuss all of these approaches would be a task for a large book, not an encyclopedic entry. The discussion here is limited to two approaches: agency/autonomy and dignity.

2.2.1 Agency and Autonomy

Grounding human rights in human agency and autonomy has had strong advocates in recent decades (Griffin 2008; Gould 2004). An important forerunner in this area was Alan Gewirth. In Human Rights: Essays on Justification and Application (1982), Gewirth argued that human rights are indispensable conditions of a life as an agent who survives and acts. Abstractly described, the conditions of such a life are basic freedom and well-being. A prudent rational agent who must have freedom and well-being will assert a “prudential right claim” (1982: 31)to them. But, having demanded that others must respect her freedom and well-being, consistency requires her to recognize and respect the freedom and well-being of all other persons, too. She “logically must accept” (1982: 20) that other people as agents have equal rights to freedom and well-being. These two abstract rights work alone and together to generate a list of more determinate human rights of familiar sorts (Gewirth 1978, 1982, 1996). Gewirth’s argument generated a large critical literature (see Beyleveld 1991 and Boylan 1999).

A more recent attempt to base human rights on agency and autonomy is found in James Griffin’s book, On Human Rights (2008). Griffin does not share Gewirth’s goal of providing a logically inescapable argument for human rights, but his overall view shares key structural features with Gewirth’s. These include basing the justification on the unique value of agency and autonomy, postulating some abstract rights, and making place for a right to well-being within an agency-based approach.

In the current dispute between “moral” (or “orthodox”) and “political” conceptions of human rights, Griffin strongly sides with those who see human rights as fundamentally moral rights (on this debate see Liao & Etinson 2012). Their defining role, in Griffin’s view, is protecting people’s ability to form and pursue conceptions of a worthwhile life—a capacity that Griffin variously refers to as “autonomy”, “normative agency”, and “personhood”. This ability to form, revise, and pursue conceptions of a worthwhile life is taken to be of paramount value, the exclusive source of human dignity, and thereby the basis of human rights. Griffin holds that people value this capacity “especially highly, often more highly than even our happiness” (2008: 32 [§2.3])

“Practicalities” also shape human rights in Griffin’s view. He describes practicalities as “a second ground” (2008: 37–39 [§2.5]) of human rights. They prescribe making the boundaries of rights clear by avoiding “too many complicated bends” (2008: 37 [§2.5]), enlarging rights a little to give them safety margins, and consulting facts about human nature and the nature of society. Accordingly, the justifying generic function that Griffin assigns to human rights is protecting normative agency while taking account of practicalities.

Griffin thinks that he can explain the universality of human rights by recognizing that normative agency is a threshold concept—once one is above the threshold one has the same rights as everyone else. One’s degree of agency above the threshold does not matter. There are no “degrees of being a person” (2008: 67 [§3.5]) among competent adults. Treating agency in this way, however, is a normative policy, not just a fact about concepts. An alternative policy is possible, namely proportioning people’s rights to their level of normative agency. This is what we do with children; their rights grow as they develop greater agency and responsibility. To exclude proportional rights, and to explain the egalitarian dimensions of human rights, including their character as universal and equal rights to be enjoyed without discrimination, some additional ground pertaining to fairness and equality seems to be needed.

This last point raises the question of whether agency-based approaches in general can adequately account for the universality, equality, and anti-discriminatory character of human rights. The idea that human rights are to be respected and protected without discrimination seems to be most centrally a matter of fairness rather than one of agency, freedom, or welfare. Discrimination often harms and hinders its victims, but even when it doesn’t it is still deeply unfair. For example, human rights that explicitly refer to fair wages and equal pay for equal work (ICESCR Articles 3 and 7.i) seem to be much more about fairness than about agency, freedom, or welfare—particularly since human rights to a wage that ensures a decent standard of living are often mentioned separately (ICESCR Article 7.ii).

2.2.2 Dignity

Many human rights declarations and treaties invoke human dignity as the ground of human rights. In recent decades numerous books and articles have been published that advocate dignitarian approaches to justifying human rights (for example, Gilabert 2018b; Kateb 2014; McCrudden 2013 and the many essays therein; Tasioulas 2015; Waldron 2012 and 2015). There have also been many critics, including Den Hartogh 2014; Etinson 2020; Green 2010; Macklin 2003; Rosen 2012; and Sangiovanni 2017.

A well-worked out conception of human dignity is likely to have at least three parts. The first describes the nature of human dignity, specifying for example whether it is a kind of value, status, or virtue (see Rosen 2012). The second explains the grounds of human dignity—that is, why, or in virtue of which shared capacities or features we all have the sort of dignity described in the first step. Finally, and third, there is the question of human dignity’s practical requirements, or what is concretely involved in “respecting” it. (See the entry on dignity for a broader discussion.)

Human dignity is often understood as a special worth or status which all human beings share in contrast to other animals (e.g., Kateb 2011). We can call this the “Special Worth Thesis”. Attempts to provide good explanatory grounds for the Special Worth Thesis identify one or more valuable features that all human persons share and that non-human animals mostly do not possess or have at much lower levels. The valuable features identified will presumably once again need to be “threshold concepts”, so that people can vary in how much of the feature or capacity they have without thereby losing, lessening, or increasing their human dignity in comparison to other persons. Human dignity is, after all, supposed to be a strongly egalitarian idea. Plausible candidates for such grounds might include moral abilities (to understand and follow moral values and norms and to reason and act in terms of them); thought, imagination, and rationality; self-consciousness and reflective capacities; and the use of complicated language and technologies, among others.

One worry about the Special Worth Thesis is its self-glorifying character. In claiming special worth we humans seem to excuse our many faults—including a terrible capacity for evil, routinely evidenced in our behavior towards other humans and towards non-human animals (Rosen 2013). Another closely associated and increasingly prominent worry is that the Special Worth Thesis is speciesist, arbitrarily ranking the interests, status, and/or value of human beings above that/those of non-human animals (Kymlicka 2018; Meyer 2001). In the context of these reasonable concerns, it is worth noting that support for, or a belief in, human dignity need not be prejudicial towards non-human animals; one can affirm the dignity of homo sapiens while also affirming the equal dignity of other species and forms of life (Etinson 2020; Gilabert 2018b). The Special Worth Thesis is optional and only defended by some theorists.

What attitudes, actions, policies, and rights follow from the duty or reason to respect human dignity? And are human rights among them? The answer will at least in part depend on what we think human dignity is. If it is a kind of virtue shared or shareable by all persons then its practical requirements will include things like praising and/or admiring those who possess it, and perhaps developing or cultivating “dignitarian” dispositions in one’s own character. If human dignity is, by contrast, a kind of value or worth (as in Immanuel Kant’s famous understanding of dignity as a worth “beyond all price” Kant 1785/1996: 43), then it is something we have reason to protect, promote, preserve, cherish, restore and perhaps even maximize, if possible. The human right to life, and its material conditions, is an intuitive product of human dignity understood in this way. If, on the other hand, we think of human dignity as a kind of legal (Waldron 2012 and 2015), moral (Gilabert 2018b; Lee & George 2008), or social status (Etinson 2020; Killmister 2020), then duties of “respect” more naturally follow.

These options are not mutually exclusive. In principle, human dignity can refer to all of these things: value, status, and virtue. If human dignity yields human rights, however, this is going to depend on exactly how we understand its practical requirements in light of its nature and grounds. This practical elaboration is the workhorse of a conception of human dignity. It normally results in one or more general maxims or guidelines: e.g., not to humiliate or degrade, never to treat persons merely as a means, to treat others in justifiable ways, to avoid severe cruelty, to respect autonomy, etc. The prospect of grounding human rights in human dignity faces critical challenges at this juncture. As we saw in the preceding discussion of agency-based approaches, the more specific and singular one’s dignitarian maxim is, the less plausible it will be as an exhaustive ground for standard lists of human rights in all their variety. On the other hand, a pluralistic set of grounding maxims will make human dignity a better source of human rights, but it is unclear whether in doing so we are simply explaining its implicit content or bringing in other values and norms to fill in its indeterminate scope. This raises the possibility that values and norms such as promoting human welfare; agency/autonomy; and fairness partially constitute the idea of human dignity rather than being derived from it (see Macklin 2003).

3. Which Rights are Human Rights?

This section discusses the question of which rights belong on lists of human rights. The Universal Declaration’s list, which has been very influential, consists of six families:

- Security rights that protect people against murder, torture, and genocide;

- Due process rights that protect people against arbitrary and excessively harsh punishments and require fair and public trials for those accused of crimes;

- Liberty rights that protect people’s fundamental freedoms in areas such as belief, expression, association, and movement;

- Political rights that protect people’s liberty to participate in politics by assembling, protesting, voting, and serving in public office;

- Equality rights that guarantee equal citizenship, equality before the law, and freedom from discrimination; and

- Economic and social rights that require that governments to forbid slavery and forced labor, enforce safe working conditions, ensure to all the availability of work, education, health services, and a standard of living that is adequate.

A seventh category, minority and group rights, has been created by subsequent treaties. These rights protect women, racial and ethnic minorities, indigenous peoples, children, migrant workers, and the disabled. This list of human rights seems normatively diverse: the issues addressed cover include security, liberty, fairness, equality before the law, access to work and good working conditions, unduly cruel treatment, and political participation.

In spite of the ample list above, not every question of social justice or wise governance is a human rights issue. For example, a country could have too many lawyers or inadequate provision for graduate-level education without violating any human rights. Deciding which norms should be counted as human rights is a matter of considerable difficulty. And there is continuing pressure to expand lists of human rights to include new areas. Many political movements would like to see their main concerns categorized as matters of human rights, since this would publicize, promote, and legitimize their concerns at the international level. A possible result of this is “human rights inflation”, the devaluation of human rights caused by producing too much bad human rights currency (see Cranston 1973; Orend 2002; Wellman 1995; Griffin 2008).

One way to avoid rights inflation is to follow Cranston in insisting that human rights only deal with extremely important goods, protections, and freedoms. A supplementary approach is to impose several justificatory tests for specific human rights. For example, it could be required that a proposed human right not only protect some very important good but also respond to one or more common and serious threats to that good (Dershowitz 2004; Donnelly 1989 [2003]; Shue 1996; Talbott 2005), impose burdens on the addressees that are justifiable and no larger than necessary, and be feasible in most of the world’s countries (on feasibility see Gheaus 2022; Gilabert 2009; Nickel 2007; and Richards 2023). This approach restrains rights inflation with several tests, not just one master test.

In deciding which norms should be considered human rights it is possible to make either too little or too much of international documents such as the Universal Declaration and the European Convention. One makes too little of them by proceeding as if drawing up a list of important rights were a new question, never before addressed, and as if there were no practical wisdom to be found in the choices of rights that went into the historic documents. And one makes too much of them by presuming that those documents tell us everything we need to know about human rights. This approach involves a kind of fundamentalism: it holds that when a right is on the official lists of human rights that settles its status as a human right (“If it’s in the book that’s all I need to know”.) But the process of identifying human rights in the United Nations and elsewhere was a political process with plenty of imperfections. There is little reason to take international diplomats as the most authoritative guides to which human rights there are. Further, even if a treaty’s ratification by most countries can settle the question of whether a certain right is a human right within international law, such a treaty cannot settle its weight. The treaty may suggest that the right is supported by weighty considerations, but it cannot make this so. If an international treaty enacted a right to visit national parks without charge as a human right, the ratification of that treaty would make free access to national parks a human right within international law, but it may well fail to persuade us that national park access is important enough to be a genuine human right.

The least controversial family of human rights is civil and political rights. These rights are familiar from historic bills of rights such as the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789) and the U.S. Bill of Rights (1791, with subsequent amendments). Contemporary sources include the first 21 Articles of the Universal Declaration , and treaties such as the European Convention , the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights , the American Convention on Human Rights , and the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights . Some representative formulations follow:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought and expression. This right includes freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing, in print, in the form of art, or through any other medium of one’s choice. ( American Convention on Human Rights , Article 13.1) Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests. ( European Convention , Article 11) No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks. (ICCPR Article 17)

Most civil and political rights are not absolute—they can sometimes be overridden by other considerations. For example, the right to freedom of movement can be restricted by public and private property rights, by restraining orders related to domestic violence, and by legal punishments. Further, after a disaster such as a hurricane or earthquake free movement is often appropriately suspended to keep out the curious, permit access of emergency vehicles and equipment, and prevent looting. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights permits most rights to be suspended during times “of public emergency which threatens the life of the nation” (ICCPR Article 4). But it excludes some rights from suspension including the right to life, the prohibition of torture, the prohibition of slavery, the prohibition of ex post facto criminal laws, and freedom of thought and religion.