The New York Times

The learning network | exhibit a: exploring and learning at science museums.

Exhibit A: Exploring and Learning at Science Museums

Teaching ideas based on New York Times content.

- See all in Science »

- See all lesson plans »

Overview | What do science museums have to offer? How can visiting a science museum complement classroom curriculum and reinforce science standards? What can students get out of a trip to a science museum? In this lesson, students reflect on the exhibits, learning experiences and purposes of science museums, then prepare for and visit a local science museum where they engage in an open-ended scavenger hunt. Afterward, they develop scripts for a museum guide to use with visitors or generate ideas for their own science museum.

Materials | Computers with Internet access (optional), copies of the handout.

Warm-Up | Begin by having the class brainstorm a list of places in their community that provide an opportunity to learn about science. Record the list on the board. Students might name science museums, zoos, nature centers, aquariums, science-oriented exhibits at children’s museums and other non-science museums, local colleges or universities, farms, weather stations, state parks, Audubon centers, planetariums, rock formations, rivers and ponds, etc.

Once students have compiled the list, you might review the major disciplines and sub-disciplines of science , and sort the locations by asking: Where would you most likely learn about life science, physical science and earth science? What places might feature, for example, astronomy? Which would most likely focus on environmental science?

Discuss further the purposes of the various sites they listed. Is their primary purpose to teach science, or do they tie science together with another focus, like history or sociology? Are they meant to inspire awe, provide an experience or promote a cause? Ask students to identify trends. For instance, they might realize that their town has many opportunities to explore the life sciences, but few places to learn about physics or chemistry.

Generate further discussion with the following questions:

- What science museums, or science exhibits in other museums, have you visited?

- Which ones are your favorites? Why? What memories come to mind?

- Which are your least favorites? What didn’t you like about these sites or exhibits?

- Which exhibits did you learn the most from? Which, if any, inspired in you a “sense of wonder about the world”? Which inspired a greater understanding of the diversity of life or made you ponder deep questions about human existence?

- Thinking about the science museums you have visited, what would you say are their missions and purposes? Is there any connection between the museums with clear purposes and those that you identified as your favorites?

- Did any allow you to experiment or interact with materials? Did you learn something from these experiences, or were they just for fun?

- In general, what should visitors take away from a visit to a science museum? Are there different answers to this question for children, teenagers and adults? If so, what are they? If not, why not?

At this point you might read aloud the beginning paragraphs from today’s article, which highlight the question of purpose for today’s science museums:

Many science museums, for example, now feature prepackaged touring shows about hit movies to draw in the crowds. (I saw costumes from the “Chronicles of Narnia” films and the stage sets from “Star Trek” films on two separate visits to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.) Otherwise sober institutions present filmic extravaganzas with only the flimsiest relationship to science (an upbeat promotional travelogue about Saudi Arabia is now getting the Imax treatment at Boston’s Museum of Science). But there are also serious inquiries going on in science museums, philosophical goals described in mission papers, conflicting theories about what should happen when visitors arrive. And differences in approaches are astonishing. I have seen meticulous displays explicating the structure of padlocks (London’s Science Museum), a hortatory exhibition of environmental apocalypse (New York’s American Museum of Natural History), a terrarium of dung beetles plowing through waste (New Orleans’s Audubon Insectarium), an array of physics demonstrations in which visitors play with sand, balls, pendulums and bubbles (San Francisco’s Exploratorium), collections of antique bicycles and movie cameras (Berlin’s and Prague’s science museums), and a 50-year-old exhibition in which mathematical principles are portrayed as beautifully as the topological surfaces on display (Boston’s Museum of Science). This antic miscellany is dizzying. But there are lineaments of sustained conflict in the apparent chaos. Over the last two generations, the science museum has become a place where politics, history and sociology often crowd out physics and the hard sciences. There are museums that believe their mission is to inspire political action, and others that seek to inspire nascent scientists; there are even fundamental disagreements on how humanity itself is to be regarded. The experimentation may be a sign of the science museum’s struggle to define itself.

Ask students: How do these descriptions of various science museums and exhibits jibe with your experiences? Which ones would you characterize as crowd-pleasers, designed to attract visitors? Which qualify as “serious inquiries”? Has it been your experience that most science museums give as much attention to “politics, history and sociology” as to hard science, if not more?

Finally, explain that students will reflect on these ideas further as they read the full article and prepare for a visit to a local science museum.

Related | The article “The Thrill of Science, Tamed by Agendas,” part of the 2010 special Museums section , examines the identity crises of modern-day science museums:

A science museum is a kind of experiment. It demands the most elaborate equipment: Imax theaters, NASA space vehicles, collections of living creatures, digital planetarium projectors, fossilized bones. Into this mix are thrust tens of thousands of living human beings: children on holiday, weary or eager parents, devoted teachers, passionate aficionados and casual passers-by. And the experimenters watch, test, change, hoping. … Hoping for what? What are the goals of these experiments, and when do they succeed? Whenever I’m near one of these museological laboratories, I eagerly submit to their probes, trying to find out.

Read the entire article with your class, using the questions below.

Questions | For reading comprehension and discussion:

- How have science museums changed in the last century? How has their purpose or message also changed, if at all?

- What difference does the author point out between the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles and the Rose Center for Earth and Space in New York? In your opinion, which approach is more appropriate for a contemporary science museum and why?

- The author describes Stephen T. Asma’s book, which suggests “a form of self-loathing” found in contemporary natural history museums. Based on your experience in science and natural history museums, does this idea resonate with you and why?

- What type of exhibits does the author hope are part of the future of science museums? Do you agree that this is where science museums should be headed and why or why not?

RELATED RESOURCES

From the learning network.

- Lesson: A World of Art

- Lesson: Bites That Kill: Creating Informative Exhibits on Malaria

- Lesson: Not Bare Bones at All

From NYTimes.com

- Times Topics: Museums

- Article: Wonders of Science at the Golden Gate

- Article: Golfing Through the Stratosphere

Around the Web

- Boston Museum of Science

- The Franklin Institute

- Exploratorium

Activity | This activity is meant to be used in preparation for a class field trip to a local science museum. For help finding a local museum, the Association of Science-Technology Centers provides a searchable database of science centers and museums by country and state.

Below is a template for a handout to lead students through a “scavenger hunt” through the museum they will visit. You will probably want to modify it in a way that meets your curricular focus as well as the specific resources and exhibits available at the science museum your class will visit.

We suggest that you pare down the open-ended suggestions provided to three to five items that you would like students to complete while at the museum, and then add questions that directly link what students are learning in class to the exhibits they will see. You may also, as suggested below, want to give students an opportunity to devise their own prompts in anticipation of their visit.

Museum Scavenger Hunt

Directions:

While at the museum, you will participate in a scavenger hunt to find exhibits or museum experiences to fit each description below. For each prompt, you will:

- Identify the name and location of the exhibit, or portion of the exhibit that fits the description.

- Describe, sketch, collect data or summarize what the exhibit is, what it does, or how you interacted with it.

- Identify three or four science key words connected to the exhibit.

- Explain briefly why you chose this exhibit as an example of the given prompt.

- Something that gives you a “sense of the human capacity to make sense of the world.”

- Something that makes a statement about the significance, or insignificance, of humans on the planet or in the universe.

- An exhibit urging “consciousness change.”

- An exhibit that gives “a sense of amazement,” awe or wonder “about the world.”

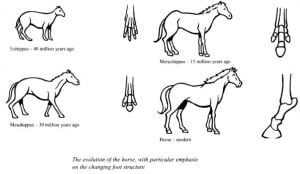

- An exhibit that demonstrates a theory or law you have learned about in class (e.g. Newton’s Laws of Motion, Cell Theory, Theory of Evolution, Atomic Theory, Conservation of Momentum, Boyle’s Law, etc.)

- Something that gives you an idea for an experiment you could conduct at home or in the classroom.

- Something interactive that allows you to experiment and collect data (tell what you did and show data in a table).

- Exhibit that interested you in a topic you weren’t interested in before.

- Exhibit that makes a connection between pop culture and science.

- An exhibit that teaches an important science skill or demonstrates something that scientists do.

- Make your own criteria and fulfill it: An exhibit that ____________________________.

For example, students visiting the Boston Museum of Science might plan to find:

- “Something that gives a sense of amazement about the world” when they visit an exhibit detailing the organization and communication of bees or walk through the butterfly garden .

- “Something interactive that allows you to experiment and collect data” in the Investigate! exhibit, where visitors can design and race their own solar cars.

- “Something that demonstrates the “human capacity to make sense of the world” in the Natural Mysteries exhibit, where they observe and classify specimens from the museum’s collections.

- “Something that demonstrates a theory or law you have learned about in class at the Science in the Park exhibit , where students investigate forces and motion.

Before the visit, provide students with your tailored handout and a map of the museum so that they can plan their visits; they might also peruse the museum’s Web site to aid in their planning. In addition, establish ground rules of the trip and the activity, including how students should work (individually or in pairs or groups) and move through the museum, when and where the class will meet up, expectations for behavior, required learning outcomes, and so on. Make sure students bring the handout and a pen or pencil as they tour the museum so they can record what they see and do under each prompt.

Back in class after the trip, have students share what they selected for each prompt and tell what they learned from the exhibits. As they review the exhibits, have students identify and discuss the purpose of the museum.

Ask: What is the museum’s primary mission? How can you tell? In your opinion, do you think the museum successfully achieves its goals to educate, inform, persuade, inspire scientific endeavors, spark an interest in science, create awe, or another goal? What did you learn from the trip? What connections did you make between what you have learned in class and what you saw in the museum? What feedback and suggestions do you have for the museum? Would you recommend visiting it to others?

Alternate activity: If the class is unable to visit a science museum, you might consider having students conduct this activity virtually. Using the same handout and prompts, and computers with Internet access, students can visit virtual exhibits by the Boston Museum of Science , the collection Resources for Science Learning from the Franklin Institute , online activities from the Science Museum of Minnesota , a digital library and hands-on activities provided by San Francisco’s Exploratorium , Web-based student activities from the National Museum of Natural History or other similar online activities from the Web site of the science museums of your choice.

Going Further | Students do one or both of the following two activities to take this further:

- Students select one of the exhibits they experienced and described on their handout, and write a script that a museum guide or docent might use to explain the exhibit. Scripts should improve the visitor’s experience of the exhibit by including background information, making it more informative, helping visitors understand the science involved or providing examples to explain how the exhibit relates to the greater context of scientific knowledge. Students perform their scripts for the class to recall their experiences at the museum (perhaps using parts of the museum’s Web site as a visual aid) and reinforce their learning of scientific concepts.

- Small groups convene and work together on this prompt: “Imagine that our town is planning to construct a new science museum or renovate an existing science museum, and that you have been asked to provide input into the museum’s focus, mission and plan for exhibits. Discuss the following questions in your group and jot down the ideas you generate: What types of exhibits should be included in the new science museum? How can you incorporate what we have been studying this year into the museum? How can you best use local resources? What should be the main goal or mission of the museum and why? How will you accomplish that goal through your choice of exhibits? What design ideas might you incorporate that would enhance the visitor experience? What can you take away from our recent museum visit to inform your planning?” When groups are ready, have them present their ideas and rationales. Discuss all of the ideas. Where and how do their purposes fit with respect to the broad spectrum of philosophies adopted by other science museums, as described in the article? Could the groups’ ideas be combined to create one museum?

Standards | From McREL , for grades six to 12:

Science 11 – Understands the nature of scientific knowledge. 12 – Understands the nature of scientific inquiry. 13 – Understands the scientific enterprise.

Technology 3 – Understands the relationships among science, technology, society and the individual.

Art Connections 1 – Understands connections among the various art forms and other disciplines.

Visual Arts 3 – Knows a range of subject matter, symbols and potential ideas in the visual arts.

Arts and Communication 1 – Understands the principles, processes and products associated with arts and communication media. 2 – Knows and applies appropriate criteria to arts and communication products. 3 – Uses critical and creative thinking in various arts and communication settings. 4 – Understands ways in which the human experience is transmitted and reflected in the arts and communication. 5 – Knows a range of arts and communication works from various historical and cultural periods.

Working With Others 1 – Contributes to the overall effort of a group. 3 – Works well with diverse individuals and in diverse situations. 4 – Displays effective interpersonal communication skills.

Comments are no longer being accepted.

What's Next

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOK REVIEW

- 21 November 2022

How science museums can use their power

- Anna Novitzky 0

Anna Novitzky is a subeditor team leader at Nature in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A nineteenth-century aircraft on display at the Paris Museum of Arts and Crafts, one of the first public science museums. Credit: CNMages/Alamy

Curious Devices and Mighty Machines: Exploring Science Museums Samuel J. M. M. Alberti. Reaktion (2022)

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 611 , 657-659 (2022)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-03795-1

Related Articles

Brunch with a carnivorous plant

News & Views 03 SEP 24

Man versus horse: who wins?

News & Views 27 AUG 24

The meaning of the Anthropocene: why it matters even without a formal geological definition

Comment 26 AUG 24

Candidate 1143172 cover letter: Junior pot scrubber

Futures 04 SEP 24

Massive Attack’s science-led drive to lower music’s carbon footprint

Career Feature 04 SEP 24

Live music is a major carbon sinner — but it could be a catalyst for change

Editorial 04 SEP 24

Guide, don’t hide: reprogramming learning in the wake of AI

Career Guide 04 SEP 24

What I learnt from running a coding bootcamp

Career Column 21 AUG 24

The Taliban said women could study — three years on they still can’t

News 14 AUG 24

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Postdoctoral Researcher - Neural Circuits Genetics and Physiology for Learning and Memory

A postdoctoral position is available to study molecular mechanisms, neural circuits and neurophysiology of learning and memory.

Dallas, Texas (US)

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Assistant/Associate Professor (Tenure Track) - Integrative Biology & Pharmacology

The Department of Integrative Biology and Pharmacology (https://med.uth.edu/ibp/), McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Scienc...

Houston, Texas (US)

UTHealth Houston

Faculty Positions

The Yale Stem Cell Center invites applications for faculty positions at the rank of Assistant, Associate, or full Professor. Rank and tenure will b...

New Haven, Connecticut

Yale Stem Cell Center

Postdoc/PhD opportunity – Pharmacology of Opioids

Join us at MedUni Vienna to explore the pharmacology of circular and stapled peptide therapeutics targetting the κ-opioid receptor in the periphery.

Vienna (AT)

Medical University of Vienna

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Advertisement

Museums as avenues of learning for children: a decade of research

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 27 October 2016

- Volume 20 , pages 47–76, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Lucija Andre ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2125-3264 1 ,

- Tracy Durksen 2 &

- Monique L. Volman 1

65k Accesses

117 Citations

37 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this review, we focus on the museum activities and strategies that encourage and support children’s learning. In order to provide insight into what is known about children’s learning in museums, we examined study content, methodology and the resultant knowledge from the last decade of research. Because interactivity is increasingly seen as essential in children’s learning experiences in a museum context, we developed a framework that distinguishes between three main interactivity types for facilitating strategies and activities in children’s learning: child–adults/peers; child–technology and child–environment. We identify the most promising strategies and activities for boosting children’s learning as situated in overlapping areas of these interactivity types. Specifically, we identify scaffolding as a key to enhanced museum learning. Our review concludes by highlighting research challenges from the last decade and recommendations for practice and future research on how to design, evaluate and guide theoretically-grounded educational programs for children in museums.

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review of the pedagogical roles of technology in ICT-assisted museum learning studies

Designing an Interactive Learning to Enrich Children’s Experience in Museum Visit

Interactive Museums - New Spaces for the Education of Children and Adolescents

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“A museum is an educational country fair” (Semper 1990 , p. 50) that is rich with exciting things for individuals to explore and discover through touch and inquiry. Museums direct learning by providing visitors with unique opportunities to explore various concepts of mathematics, art and social science. As with museum education experts (e.g. Falk and Dierking 2000 ; Falk and Storksdieck 2005 ; Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ; Kelly 2007 ), we recognise the need for a conceptual change from museums as places of education to places for learning. By responding to the needs and interests of visitors, we believe that museums can transform from “being about something to being for somebody” (Weil 1999 , p. 229).

Children’s learning takes place in a range of formal (i.e. traditional classroom) and informal settings (e.g. unstructured and self-paced museum program; Falk and Dierking 2000 ). Generally, learning in museums and other non-school-based environments is referred to as informal or free-choice learning and is qualitatively different learning from that in schools (Falk and Dierking 2000 ). As a result, findings from research in school-based settings are not easily transferable to museums because learning in museums operates in rich and complex sites and focuses on concrete material such as objects and exhibits (Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ).

Although the last three decades of museum research have resulted in significant findings and advances, there are many knowledge gaps about learning in museums. For example, the importance of visitor’s personal context (motivation and experience), social interaction and the museum context are highlighted as important factors in museum learning and meaning making (e.g. Falk and Dierking 2000 ). However, we know very little about children’s learning processes and results from experiences in different museum types, and how their learning can be best guided. Moreover, there is a need to map the appropriate research approaches that would facilitate this goal.

For the purpose of this review, we define museums as informal learning environments as accessible by the public, based on the subjects of science, history, archeology and arts, and involving various objects and exhibits (live and/or simulated) and programs. Consequently, we refer to various types of museum such as: science museums and centres, children’s museums, history and archaeology museums, and art museums/galleries. Interactivity is a focus of this review because it is increasingly seen as essential in children’s learning experiences in a museum context (e.g. Cheng et al. 2011 ; Falk and Storksdieck 2005 ). That is, learning is seen as embedded in the interactive process between children and knowledgeable ones, and media at hand, which makes children’s museum learning both dialogical and hands-on (Henderson and Atencio 2007 ).

Audiences of various ages, including children, visit museums. A bibliographic review by Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri ( 2000 ) focused on a decade (1990–1999) of general museum learning research and highlighted how children’s museum learning was mainly studied in the context of science museums in the United States. Very little was revealed about children’s learning in history and archaeology museums or art galleries, and in other countries. The majority of research in science museums concentrated on exhibits, while learning through participation in educational programs or while using educational materials was scarce. Most of the studies reviewed by Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri used a positivistic approach to learning with an emphasis on testing hypotheses.

Research on child-focused museum programs primarily aimed to understand children’s learning from a theoretical base, used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, and placed learning within the sociocultural context. The effect of interactions with adults on children’s museum experience was highlighted with attention to adult scaffolding as particularly supportive of children’s learning. Overall, Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri ( 2000 ) identified a need for more research into children’s learning across various types of museums. Also, they made a plea for research that makes the study design transparent, by clearly describing the process of museum learning, and how it is the same as or different from learning processes in other sites.

Children represent one of the major museum visitor groups and not just in children’s museums. For example, in the United States, about 80 % of museums provide educational programs for children (Bowers 2012 ) and spend more than $2 billion a year on education activities (American Alliance of Museums 2009 ). Although a surprisingly-high number of museums offer educational programs for children, there is no review focusing mainly on children’s learning within museums. In particular, very little is known about preschool and elementary school-aged children learning in museums. In order to create museum environments that are conducive to children’s learning, there is a growing desire for museum professionals and researchers in museum education to know more about children’s learning in museums. To move this process forward, there is a need to form a foundation based on previous research efforts, identify issues and present directions for future research on children’s museum learning.

This review is, to the best of our knowledge, the first that covers both theoretical and empirical studies about children’s learning in various museums types in the last decade (1999–2012) and across countries. Based on the identified gaps in the research, an agenda for future research into children’s learning in museums is offered. The review is scientifically relevant in two ways: (a) it provides an overview of learning theories and methodologies for studying learning in museums, which can be used by museum researchers and for other informal learning studies and (b) it develops a framework of facilitating strategies and activities for children’s learning in museums. We conclude with practical implications that offer a foundation for museum professionals in designing theoretically-grounded and effective educational programs for this target group of visitors, and help museum educators, teachers and families to facilitate children’s learning in various types of museums.

The overall aim of our review is to provide insight into what is known about children’s learning in museums worldwide over the last decade, while focusing on how learning can best be facilitated. Specifically, we aim to identify what has been studied, how children’s learning in museum has been studied and what knowledge this research has yielded. We focused the analysis of what has been studied about the strategies and activities aimed at facilitating children’s learning in museums. Specified questions were aimed at distinguishing the what (e.g. different strategies and activities) and how of children’s learning in museums. First, however, we want to characterise the research in terms of learning theories that inform the research on children’s learning in museums and the methodological approaches used. By mapping the well-recognised learning theories and research methods, we aim to prepare the ground for further research improvements. To this end, we posed the following research questions:

Which learning theories informed the research?

Which methodological approaches were applied?

Who and what were facilitating the learning?

Which activities and strategies were used to facilitate children’s learning?

What knowledge has the research yielded about children’s learning in museums?

Article selection

We performed the literature search for related articles in February 2012. We initially searched the database of the Web of Science for peer-reviewed theoretical and empirical articles published between 1999 and 2012 and relevant to children’s learning in museums. The reason for starting the search in 1999 was that a comprehensive bibliographic review of research on this topic until 1999 is available (Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ). Articles were included if they were: (a) written in English; (b) published between 1999 and 2012; (c) provided a definition or description of learning in museums within the theoretical, methodological or results sections and (d) focused on preschool or elementary-school visitors under 12 years old (identified as the general age for the start of high school in most of the study populations). We excluded articles on visitors of high-school age because younger children’s museum experiences can be qualitatively different and depend on their development of abstract-level thinking/operations (Van Schijndel et al. 2010 ). We also excluded articles from our review if the focus was on museum curators’ learning or training programs and if articles lacked a clearly-stated theoretical and/or methodological approach. However, because the museum field is developing, in a few cases, we decided to include resources that did not completely match our inclusion criteria, because they could help to answer our research questions.

Our five-step review procedure is summarised in Table 1 . Step 1 involved a search of the Web of Science database. Step 2 focused on two leading journals on research and theory in museum education ( Curator: The Museum Journal and Journal of Museum Education ). In Step 3, we examined the results of 264 studies, with 33 deemed to be relevant to this review. Step 4 involved a concurrent search during which we compiled an additional eight articles from leading researchers in the field of museum education, our review of 33 reference lists, and familiar empirical research. Lastly, Step 5 centred on identifying key resources. In total, our review was based on 44 sources (identified in the reference list with an asterisk): 41 peer-reviewed articles, a review (Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ), a doctoral dissertation (Kelly 2007 ), and a book (Falk and Dierking 2000 ). Of the selected articles, we identified articles that were written by the same author/coauthor more than once: Falk (3), Piscitelli (2), Tenenbaum (2) and Weier (2).

Analysis strategy

Our analysis of the 44 sources involved three subsequent rounds. First, we examined the articles in order to develop a general profile of the research on children’s museum learning. This round of analysis was also aimed at identifying the main learning theories (research question 1) and methodological approaches (research question 2) used in research on children’s museum learning. Our interpretations of the theories and/or the methodologies applied in empirical studies were guided by Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri ( 2000 ) and the reviewed theoretical papers. The second round of analysis sought to answer research questions 3 and 4 while contributing to the development of a framework of facilitating strategies and activities. This framework was further developed during several discussions between the first and the third author after a first reading of the articles. We present our framework in the methods section (under Analysis scheme), as it was used to analyse the literature in the third round of analysis and to organise the main part of the review (research questions 3, 4 and 5). In the third round of analysis, the first author used the framework to code the articles. Also the other columns of Table 3 in Appendix were filled. The second author checked the coding and Table 3 for unclear aspects and inconsistencies. If necessary, the original articles were consulted, and Table 3 was complemented or changed. The second author critically reviewed the interpretations as presented in the text.

Analysis scheme

The highlighted value and different forms of interactivity (as the core of a learner’s museum experience) guided our framework development. In fact, interactivity became the focus for our unit of analysis (facilitating strategies and activities in children’s museum learning). It is important to note that, within our framework, we refer to facilitating strategy in a much broader sense than activity. That is, while the latter presents a specific and single activity type or task (e.g. to tell a story), the former comprises a structured or semi-structured combination of different activities (e.g. hands-on, story-telling, explanation) that have a shared learning goal. Table 2 presents the seven descriptors that we used when coding facilitating strategies and activities. Figure 1 displays an illustration of our framework in which we distinguish between three main interactivity types (coded 1 to 3) and four that share qualities of the main types (coded 4 to 7).

The framework of facilitating strategies and activities in children’s learning in museums

In this section, we present an overall profile of the reviewed resources, theoretical perspectives, methodological approaches and information sources used, as well as results based on applying our framework for children’s learning in museums. Because research context has a major effect on the way in which learning is conceived and on the research methodologies chosen (Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ), we present our findings according to type of museum: science museums and centres, children’s museums, natural history museums, and art museums/galleries. (In cases for which the research encompassed more than one museum type, we grouped the research within the science museums and centre type, as this was the most common type.) Findings are presented in narratives and augmented with examples. Table 3 in Appendix presents a systematic overview of the reviewed empirical studies along with methodological characteristics and study design.

Profile of the research

As displayed through Fig. 2 , our review revealed children’s learning in museums as being researched primarily in science museums and centres, followed by history museums (especially natural history museums)—adding up two thirds of the research. In contrast, very few research studies were conducted within children’s and art museums and galleries. The majority of study participants were children older than six years, with much research focusing on 9-years-old and elementary-school students (52.28 %). Out of 44 studies, about half (47.72 %) focused on children (under 9 years old) and took place in Australian and American museums (e.g. Anderson et al. 2002 ; Mallos 2012 ). About two-thirds of the studies reviewed focused on field-trip visits to museums from schools, with less of an emphasis on family learning. However, interactions within parent–child dialogues during a family visit and within whole-class and small-group settings were the focus of the majority of the studies, with peer dialogue interactions studied at a slightly lesser extent (see Table 3 in Appendix). A somewhat surprising finding was how few studies examined children’s exploratory behaviour while learning during a museum program or exhibit.

Percentage of total 44 reviewed sources presented per museum type

Of the 44 articles, more than half were conducted in the US (59.09 %), with the remainder spanning a range of locations (13.63 % in Australia, 9.09 % in the UK, 9.09 % in Europe, 6.81 % in Asia and 2.27 % in Canada). The majority of the research was empirical (31 articles) and cited descriptive or exploratory case studies and surveys (with the exception of one ethnographic study). As well, two action-research studies and 13 experimental studies were included (see “ Appendix ”). The remaining articles were categorised as theoretical (12 resources) or a review (1 article). Most of the descriptive research depicted learning activities, interactive exhibitions, conversations with museum educators or parents and peers (and the roles that they take), as well as children’s interactions and learning experiences with the exhibit or with objects in museums. Most of the theoretical studies (27.27 %) focused on the conceptualisation of the nature of learning in museums (Falk 2004 ; Falk and Dierking 2000 ; Falk and Storksdieck 2005 ), characteristics of learning in museums (e.g. Rennie and Johnston 2004 ) and the design of the research in learning in museums (e.g. Reisman 2008 ).

Theoretical perspectives

In the last decade, constructivism and, in particular, sociocultural theory have greatly impacted children’s programs/exhibition and museum learning research designs (Bamberger and Tal 2007 ; Falk and Storksdieck 2005 ; Martell 2008 ; Rahm 2004 ). Also, researchers have highlighted how the museum environment influences theory choice (Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ). Sociocultural theory extends Vygotsky’s ( 1978 ) concept of learning as a socially-mediated process in which learners are jointly responsible for their learning. Specifically, Vygotsky outlined the idea that human activities are formed by an individual’s historical development and take place in a cultural context through social interactions that are mediated by language and other cultural symbol systems. Vygotsky’s theory highlights the importance of scaffolding when learning—as the temporal verbal and nonverbal guidance provided by adults when assisting children at tasks—in order to help them to move towards understanding, independent learning or task/concept mastery. The importance of guidance was evident in our review (Van Schijndel et al. 2010 ; Wolf and Wood 2012 ) and was provided in a variety of ways (modeling, posing of questions). Several researchers (DeWitt 2008 ; Martell 2008 ; Rahm 2004 ; Zimmerman et al. 2008 ) who used sociocultural theory focused their analyses on parent–child and school–group conversational interactions. For example, Zimmerman et al. ( 2008 ) examined the interweaving role of children’s cognitive resources, social interaction and cultural resources in knowledge construction and meaning-making of the scientific content and practices.

In 2000, Falk and Dierking applied sociocultural theory to museum learning research to highlight not only what happens during a museum visit, but also the where and with whom . This theoretical milestone centred on the development of the contextual model of learning (CML) as a general framework for learning in museums (see also Falk and Storksdieck 2005 ). The CML identifies 11 factors that influence learning and sorts them into three main contexts: personal, physical and sociocultural. The personal context represents the history that an individual takes into the learning situation of a museum (i.e. individual’s motivation and expectations, prior knowledge and experience, interests and beliefs, and choice and control). The physical context includes: advance organizers, orientation to the physical setting, architecture and physical space, design of the exhibit, and subsequent reinforcing events. On the other hand, the sociocultural context (i.e. within-group social mediation and facilitated mediation by others) involves visitors as part of a social group (e.g. family, school, preschool) that form a community of learners. Socially-mediated learning in museums also occurs through interactions with knowledgeable adults (parents, curators and teachers) using scaffolding strategies during programs/exhibits to maximise children’s learning. Sociocultural theory (as well as a moderate use of constructivism) was also evident in Tenenbaum et al. ( 2004 ) application of Fischer’s skill theory (Fischer and Bidell 1998 ). Here, skills are domain-specific and there is a high degree of variability across tasks and contexts (Fischer and Bidell 1998 ).

Overall, the specific museum environment was found to have an impact on the choice of learning theory (Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri 2000 ). The theory of social practices (a type of sociocultural theory) conceptualises knowledge as practical understanding and ability, with practice being situational ‘doing’ in relation to social and material surroundings (Reckwitz 2002 ). Based on this theory, Wöhrer and Harrasser ( 2011 ) proposed a framework that helps understanding of children’s practices in the context of, and in relation to the setting of, children’s museum. Within this framework is a focus on children’s interactions with technological objects in different settings and through games. Children’s knowledge acquisition was considered to be embedded in their handling of objects and involved task performance.

Additional theories emerged from our review. For example, Milutinović and Gajić’s ( 2010 ) study within the context of art museums/galleries was rich with multisensory experience activities and aligned well with Gardner’s ( 1999 ) theory of multiple intelligences. Another example of theoretically-framed research within children’s museums included exhibits of real-life social and nature environments (e.g. Puchner et al. 2001 ). Such research aligned well with Bandura’s social cognitive theory ( 1986 ) given the focus on learning as a change in mental representations because of experience that could, or could not, be manifested in behaviour.

Methodological approach and information sources

The last decade of research into children’s museum learning is rich with examples of how quantitative and qualitative methods can help to describe facilitating activities and strategies, children’s learning experience, engagement with an exhibit, and assessing learning. For example, we found a number of the studies that used qualitative approaches to provide a more-comprehensive portrayal of children’s museum learning (see “ Appendix ”). Compared with the previous decade, there has also been an increase in longitudinal designs about assessment of learning (e.g. Anderson et al. 2002 , 2008 ; Rahm 2004 ). The findings of this review were in contrast to those of Hooper-Greenhill and Moussouri’s ( 2000 ) review, for which the methodological approach was mainly positivistic and focused on hypothesis testing.

Our review revealed 31 empirical studies whose characteristics and study designs are systematically presented in the “ Appendix ”. Much of the qualitative research performed in museums was classified as descriptive. Often case-study designs (e.g. microanalysis or multiple case studies) or action research designs were used, mainly in art museum/galleries (e.g. Martell 2008 ; Milutinović and Gajić 2010 ). Qualitative data collection included pre/post interviews, field notes and participatory observations of activities and interactions. Reviews of documents such as children’s drawings were used in art museums/galleries and science centres (Martell 2008 ; Milutinović and Gajić 2010 ), whereas worksheet assignments and children’s diaries were used in history and science museums (e.g. Martell 2008 ). The most recommended information source in all types of museums for capturing adult–child, peer–peer and child–object/exhibit interactions, learning experience, and to describe children’s behaviour, were video recordings (for example, see Martell 2008 ).

In science and (natural) history museums, quantitative research methods typically addressed the use and effectiveness of learning activities and strategies or educational programs. Quantitative information sources used in all types of museums research often involved surveys that required children or teacher/parent to answer closed- or open-ended questions (e.g. Bamberger and Tal 2007 ; Murriello and Knobel 2008 ; Zimmerman et al. 2008 ). However, measuring preschool children’s learning in relation to interactivity has proved to be a challenge in museum education research (Van Schijndel et al. 2010 ). Because a focus on children’s verbalisation is best combined with is a focus on their actions, Van Schijndel et al. ( 2010 ) used an exploratory behavioural scale that measures children’s behaviour and the quality of interactions.

All of the reviewed studies were of high quality, particularly with respect to clearly stating the purpose of their study, describing the study setting (e.g. type of the museum, exhibit, educational program and its duration, strategies and activities used) and specifying the people involved (e.g. museum educators, teachers, parents). As museum learning is difficult to measure (Reisman 2008 ), most studies we reviewed benefited from the use of the multiple instruments in assessing children’s learning (e.g. Bamberger and Tal 2007 ; Benjamin et al. 2010 ; Palmquist and Crowley 2007 ). However, we also noted a few methodological shortcomings of the reviewed studies.

When interpreting the study results, we were cognizant of a range of limitations. First, one third of the empirical studies did not cite the number of participants. With the exception of a few studies (see “ Appendix ”), others specified a small sample size ( N < 100) that influenced the power of the study. Second, most of the studies in art and children museums did not report the reliabilities associated with their instruments or coding structures. Science museums and centres, as well as history museums did, but they reported moderate to high reliabilities for the instruments used (α = 0.60 and 0.95). Lastly, studies that primarily relied on the use of subjective measures in the assessment of learning (e.g. interviews and self-reports), could have measurement bias, which can be solved by the use of more objective measures (e.g. knowledge tests).

Overall, the challenge for researchers investigating children’s learning in museums is to account for a multitude of confounding, competing and mutually-influencing factors (e.g. motivation and beliefs, design of the exhibition, social interaction; Falk and Dierking 2000 ). In order to answer this challenge, Reisman ( 2008 ) has argued for the use of design-based research (DBR), including both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies in a complementary way. Although this approach has been primarily used in formal education for creating complex interventions in classroom settings (e.g. Brown 1992 ), it is beginning to be used in science museums for examining the process of learning. Because DBR often combines qualitative and quantitative measures to study learning, it allows observing the system holistically while maintaining awareness of the changes in the learning process, interactions and resulting outcomes (Reisman 2008 ).

Framework of children’s learning in museums

The reviewed studies focused on children’s interactions with adult guides (e.g. curator, parent, teacher, scientist) and technology, accompanied with hands-on activities that facilitated children’s learning. Our review revealed the dominance of facilitating strategies and activities present in seven interactivity types defined in Table 2 : (1) child–adults/peers, (2) child–technology, (3) child–environment, (4) child–environment–adults/peers, (5) child–technology–adults/peers, (6) child–technology–environment and (7) total interaction. What follows is a description of interactivity according to four learning contexts: science museums, children’s museums, (natural) history museums and art museums/galleries.

Science museums

Science museums and centres are valuable resources for first-hand technological exploration that often are not available for students in formal learning settings (Glick and Samarapungavan 2008 ). Moreover, they are considered helpful resources for supporting the inclusion of gifted children, teacher professional development and field trips (Henderson and Atencio 2007 ). During the last decade, the role of museum guide in science museums and centres has become more geared towards interaction with children (Cheng et al. 2011 ). Not surprisingly, the majority of reviewed studies (15) were within the context of science museums. Most of these studies focused on students’ learning during field trips and family visits to the museum, with seven studies on preschool learning. Mainly studies of effectiveness took place within science museums and centres (see “ Appendix ”) and they focused on the effectiveness of interactive exhibitions, museum/school interventions and coaching. Analyses performed in the reviewed studies focused on the extent of exhibit exploration, knowledge and understanding of science concepts and phenomena, and attitudes.

We also reviewed studies that demonstrated the child–environment–adults/peers interactivity type by using different levels of guidance to explore children’s learning (see Bamberger and Tal 2007 ; Rahm 2004 ; Van Schijndel et al. 2010 ). While Van Schijndel et al. ( 2010 ) explored scaffolding, explaining and minimal coaching style on preschool children’s hands-on behaviour, Bamberger and Tal ( 2007 ) inspected three levels of choice activities (free-choice, limited-choice, and no-choice interactivity). Results revealed three key findings: (1) the scaffolding coaching style implied that the guide aroused the child’s investigations to the next level by asking open questions and directing the child’s attention to specific exhibit parts, (2) the explaining coaching style included an exhibit demonstration and its explanation (e.g. causal connections, physical principles) and (3) the minimal coaching style (child–environment interactivity) served as the control condition (the child freely interacted with the exhibit; Van Schijndel et al. 2010 ).

Overall, this selection of findings revealed that different levels of scaffolding and guidance yielded differences in children’s learning. That is, children showed more active manipulation with the exhibit when coached with the scaffolding style, and more exploratory behaviour when coached with the explaining style (Van Schijndel et al. 2010 ). While limited-choice activities yielded the most advantages (e.g. promoted teamwork during problem solving), the no-choice activities allowed students to connect experiences from the visit to their school and non-school knowledge (although strongly dependent on the guide’s teaching skills). As anticipated, the free-choice activities (e.g. pressing buttons, operating objects) resulted in insufficient understanding and frustration (Bamberger and Tal 2007 ). Finally, in the study by Rahm ( 2004 ), the children developed an understanding about the exhibit through parents’ and children’s ‘listening in’ during ongoing conversations, observation and the manipulation of an exhibit (child–environment–adults/peers interactivity). Therefore, we consider that visits to museums that include activities founded on scaffolding, limited choice and encouraging parents–child action and conversations (that externalise children’s meaning-making) are most supportive of children’s learning as they develop their natural curiosity into more substantial learning.

In many science museums and centres, the rapid evolution of information and communication technologies have replaced the role of humans in facilitating children’s learning (Cheng et al. 2011 ; Murriello and Knobel 2008 ; Hsu et al. 2006 ). As a result, multiple and overlapping interactivity types are occurring with child–technology (see Fig. 1 ). For example, Hsu et al. ( 2006 ) demonstrated that a child–technology–environment interaction occurred when mobile phones were employed to help to improve elementary-school children’s learning in a science museum. In this study, the pre-visit learning stage included creation of a learning plan by specifying the student’s subjects of interest, visit date and duration of stay. The onsite-visit learning stage took place during the student’s museum visit, where he/she engaged in the learning activity using a handheld device. Learning was made personal when all the tracked learning behaviour was analysed and results informed recommendations for the student. During the post-visit learning stage, the student was encouraged to continue learning via the Internet after leaving the museum.

With advances in computer technologies and networked learning in science museums, educators and researchers have begun to create the next generation of blended learning environments that are highly interactive, learner-centred, authentic, meaningful and fun. One example of child–technology–adults/peers interactivity that involved an interactive computerised simulation exhibit (a 3D virtual brain tour combined with a video game format; Cheng et al. 2011 ) was found to be highly effective as a teaching and learning tool for improving the neuroscience literacy of elementary-school children. First, the exhibit involved a 3D virtual brain tour for which visitors viewed and manipulated the comparison between a normal and a methamphetamine-impaired virtual brain. Next, visitors played a driving video game that simulated driving skills under methamphetamine-abused conditions. The brain models were presented on displays (viewable by multiple people simultaneously) and children used a video game controller to navigate and manipulate the virtual brain, thereby authoring their own learning experience. While the simulation exhibit environment was effective in promoting children’s understanding and attitudes, children performed better if they had parents’ help (child–technology–adults/peers interaction).

Like Cheng et al. ( 2011 ), Murriello and Knobel’s ( 2008 ) study employed technology in order to increase the nanoscience and nanotechnology understanding of children. During an hour-long experience guided by an actor and facilitators, visitors participated in four interactive-collaborative games and watched two narrated videos. Children recounted the rich learning experience about identifying small-scale length or the concept of tiny particles. By studying an educational multimedia experience (music, images and computer simulation) presented in an attractive, playful and modern environment, Murriello and Knobel ( 2008 ) demonstrated the combination of facilitating strategies and activities of all interaction types.

Children’s museums

According to the Association of Children’s Museums ( 2008 ) children’s museums are places where children, usually under the age of 10 years, learn through play while exploring in environments designed for them. For example, one museum’s slogan of “Hands on, minds on, hearts on!” (Wöhrer and Harrasser 2011 , p. 473) refers to a learning concept involving physical, emotional and intellectual experiences—an often-seen characteristic of learning practices in children’s museums. While our conclusions are limited to our review of six articles, the research conducted in children’s museums appears to centre on defining what early learning looks like and on exploring the role of adults in children’s early learning experiences.

Studies revealed that preschool children’s learning within children’s museums exceeds simple acquisition of facts and disciplinary content knowledge and, instead, extends into developmental areas such as procedural or cause/effect learning (e.g. Puchner et al. 2001 ). Although most of the six reviewed studies focused on describing the facilitation strategies and activities, two studies explored learning gains. The positive effects on children’s learning emerged mainly as an outcome of active adult guidance, which provided evidence of a shifted focus from child-centred to family-centred experiences in museum learning (e.g. Benjamin et al. 2010 ; Freedman 2010 ). Museum professionals realised that, in using child-centered approaches, they had overlooked the critical role of adults as members of the learning group, and that their integration into the learning process can offer the impetus to expand the learning experience beyond the museum (Wolf and Wood 2012 ).

The importance of scaffolding was highlighted in most of the studies as an essential strategy for maximising children’s learning during family or school visits to museums (e.g. Benjamin et al. 2010 ; Puchner et al. 2001 ; Wolf and Wood 2012 ). For example, Wolf and Wood ( 2012 ) present the ‘Kindness tree’ exhibit in the Indianapolis children’s museum as an excellent example of scaffolding use. The exhibit told the story of prejudice and intolerance through the life stories of Anne Frank, Ruby Bridges and Ryan White while encouraging children to have the power to confront intolerance by using their words, actions and voices. Scaffolding occurred when parents read messages about kindness acts from magnetic ‘leaves’ and related those experiences to the child as he/she completed the activity. Scaffolding was more frequent and intensive at exhibits that included activities with clear directions for adults, that were attractive for them (but children had trouble performing correctly on their own) or that invited participation through scripts/labels of the exhibits (Puchner et al. 2001 ). In line with this, Wolf and Wood ( 2012 ) recommended that that content of an exhibition can be scrutinised for potential scaffolding opportunities by determining various levels of content accessibility or providing a learning framework for specific age groups.

Also derived from sociocultural theory is the acknowledgement of collaborative verbal parent–child engagement as a potentially powerful mediator of cognitive change. Therefore, it is no surprise that parent–child conversational interactions were highlighted in research on children’s museums research. Benjamin et al. ( 2010 ) elaborated on the effectiveness of open-ended ‘wh’ questions (e.g. What? Why? ) during a child–adults/peers interaction in a museum. Ideally, these questions can reflect and change what is understood by focusing children’s attention on what is available to learn, obstacles and problem-solving strategies. In Benjamin’s study, the conversational instruction coupled with hands-on activities (child–environment–adults/peers), resulted in children’s abilities to report program-related content immediately after the exhibit and again after two weeks.

Guided (either by parent or museum educator) hands-on activities were the leading effective activities for facilitating children’s learning in most children’s museums and a representation of child–environment–adults/peers interactivity. For example, an intervention study (Freedman 2010 ) revealed a significant positive change in children’s knowledge about healthy ingredients after a ‘Healthy pizza kitchen’ program (a presentation followed with a hands-on mock pizzeria exhibit). In this study, Freedman conducted a playful experiments strategy (child–environment and child–environment–adults/peers interactivity) which presented an example of how hands-on activities help to facilitate children’s learning through child–adults/peer and child–environment interaction.

Overall, strategies and activities applied in children’s museums represent the interactivity types child–adults/peers and child–environment, as well as predominantly their overlapping area (child–environment–adults/peers). Despite the positive influence of parental involvement on children’s learning found in children’s museums, Wolf and Wood ( 2012 ) indicated that parents’ beliefs and roles about guiding their children’s learning are often divergent from ideas highlighted by museum professionals and researchers. For example, a lack of understanding of the importance of play for children’s learning, and parents discomfort or hesitation to play in public, lead them to simply watch instead of interact while their children play.

(Natural) history museums

Our review included 11 studies set in historical museums (generally natural museums). Most studies we reviewed described museum learning as meaning-making during a field trip or family visit to a museum, with effectiveness being the focus of examination in five studies (Melber 2003 ; Sung et al. 2010 ; Tenenbaum et al. 2010 ; Wickens 2012 ; Wilde and Urhahne 2008 ). History and archeological museums feature a plethora of information, normally in the form of science specimens and cultural or historical artifacts (Cox-Petersen et al. 2003 ). Historical museums with three-dimensional models or live exhibits can afford children the opportunity to construct richer and more-realistic mental representations relative to traditional digital and pictorial illustrations in textbooks. Furthermore, with access to various historical documents, images and collection items (often unavailable in formal settings as schools), children are not just exposed to primary resources as learning tools, but also to interpretations of the past that guide them through history (Wolberg and Goff 2012 ).

History museums are ideal places for stories to be told and, because storytelling serves as a fundamental way of learning and defining human values and beliefs, interactivity can help to “make connections between museum artifacts and images and visitors’ lives and memories” (Bedford 2001 , p. 30). Dramatic narratives or storytelling were highlighted in all reviewed (natural) history museum papers as having a pivotal role in facilitating children’s learning (e.g. Bowers 2012 ; Hall and Bannon 2006 ; Kelly 2007 ; Tenenbaum et al. 2010 ). By including a role for a knowledgeable adult (or a technological aid) to tell stories, these studies provided examples of two interactivity types (child–adults/peers and child–technology) and the overlapping framework areas (child–environment–adults/peers interactivity and total interactivity).

Wickens ( 2012 ) also described the use of a storytelling activity for preschool children as part of a three-mode structure (story/tour/activity). The three-mode structure strategy was identified in our framework as belonging to the overlapping area of child–environment–adults/peers (see Fig. 1 ) because it combined narratives, hands-on activities, free play, free exploration and guided multisensory experience. Children participated in the interactive story, then moved to the gallery to explore the themes, and returned for the creative activity. Results confirmed that the three-mode structure helped children to feel a sense of comfort because their familiarity with story time and art-making activities helped them to have control during their learning and facilitated learning. Moreover, Hall and Bannon ( 2006 ) found that narratives provided by a computer within an exhibit can also engage children by affording an overall coherence and intelligibility to their museum activities. In their study, exhibit interactivity was examined in two rooms: the study room where children heard stories if they pressed ‘the virtual touch machine’ and the ‘room of opinions’ where children were encouraged to explore clues and develop their own opinions about artifacts through hands-on activities. This particular study design provides an example of the total interactivity type represented through our framework (i.e. the combination of activities from all three main interactivity types, namely, child–adults/peers, child–technology and child–environment).

Inquiry-based activities and conversations at the exhibit or as part of problem-solving with a mobile guide system (MGS) can be positioned in the overlapping areas of our framework (child–environment–adults/peers, child–technology–environment and total interactivity) and were commonly described and highlighted as successful for helping children to gain knowledge and meaning about the past (e.g. studies by Melber 2003 ; Sung et al. 2010 ). For example, the MGS problem-solving strategy designed by Sung et al. ( 2010 ) involved total interactivity. In contrast to the commonly-used audio-visual guiding system that provides only information about each exhibit (via pictures, texts, voice narratives), the MGS offered a problem-solving scenario that guided the learners to look at the exhibits, browse the information on their mobile phone, discuss it with their peers, and solve a series of questions to complete the quests. Because results revealed increased interest and enjoyment during the activity, recommendations include that museum educators and teachers utilise MGS, and that researchers and system developers design more guided-learning activities and systems that constitute problem-solving tasks with inquiries. Limitations include learners being absorbed by amazement about the technological possibilities, the ‘magic’ of the concealed technology (Hall and Bannon 2006 ), rather than on the task-at-hand. Future research could involve how technology can be made less obvious and how concealing technology might influence children’s learning experience (Hall and Bannon 2006 ; Sung et al. 2010 ).

Inquiry was also part of the learning strategy ‘thinking routines’ (child–adults/peers interactivity type)—identified by Wolberg and Goff ( 2012 ) as advantageous in supporting young children’s learning in museums. With this strategy, children were encouraged to see, think and wonder when encountering a new object or image. An important goal of this strategy was to expose students to the language of thinking through guided conversation and questions (posed by both museum educator and children) in order to deepen understanding and gain knowledge. The information gathered by a student did not come just from visual cues within the collections, but also from thoughtful inference, reason and deduction—a strategy that could further enhance children’s learning even within the limited period of a museum visit. By using careful observations and thoughtful interpretations involving an image or artifact, students’ thinking and learning became more visible to themselves, teachers and peers.

Wilde and Urhahne ( 2008 ) found open-ended tasks involving child–adults/peers interactivity to be less successful than closed tasks (or a combination of both) in contributing to knowledge gains and, in particular, less intrinsically motivating for fifth-grade students. The children showed more interest/enjoyment with closed tasks and greater short-term and long-term retention of knowledge (after four weeks) through closed and mixed tasks. On the other hand, children who engaged with open-ended tasks did not show evidence of increased learning and showed less task-related intrinsic motivation. As a result, Wilde and Urhahne recommend a museum visit with more structured tasks and a certain amount of instruction (i.e. closed tasks) for children. Tenenbaum et al. ( 2010 ) emphasised the importance of activities within interactivity types child–environment and child–environment–adults/peers by suggesting that hands-on support for children (e.g. booklets, backpacks with props) through exhibits can enrich their conversations as they require more engagement with the museum exhibit. Overall, Melber ( 2003 ) recommends a combination of hands-on and inquiry-based activities as effective (particularly for gifted elementary school-aged children) at influencing attitudes and understanding of the scientific work. For example, Melber found that children were fascinated by the opportunity to handle objects and to have the time to critically look at and discuss the object’s characteristics with peers and/or curators. In addition, children became aware of the different scientific careers associated with a museum in an engaging and personally-relevant manner.

Palmquist and Crowley ( 2007 ) stressed that parents of gifted or ‘expert’ children should be particularly cautious when facilitating their learning. Through family conversation analysis with children (ages 5 and 7 years), Palmquist and Crowley found that, when compared with children of less experience and content knowledge, children developing an “island of expertise” (p. 784) had parents who provided a reduction in active contributions to learning conversations. In fact, children with less experience focused on the features of objects and learned together through conversations with parents. Here we recognise a knowledge gap about how to support and extend learning trajectories in museums and, in particular, how to use the expert knowledge of children as a platform for future learning.

Art museums/galleries

Art museums/galleries are often seen as imposing places that keep a myriad of valuable artworks and objects and that are intolerant for any kind of child-centred exploration (Weier 2004 ). With “ever-present security guards, overwhelming architecture, stillness, quietness, and artworks displayed at adult height” (Weier 2004 , p. 106), latent messages project that children are not welcome. Art museums are unfortunately the most reluctant type of museum to embrace early childhood visitors (Mallos 2012 ) despite how children are naturally attracted to contemporary art—to its abstractions, diversity, scale and experimentation, and by being open-minded and spontaneous in their interpretations. According to Jeffers ( 1999 ), when welcomed and empowered by developmentally-appropriate learning strategies and activities, children can “actively connect” (Jeffers 1999 , p. 50) with the museum and its contents, providing imaginative insights and new perspectives about the artworks.

Of nine reviewed studies, there was only one study of effectiveness (Burchenal and Grohe 2007 ) that assessed the effects of the program on the development of critical thinking skills. Most of the reviewed studies and descriptions of children’s learning in art museums took place in Australia and the UK and were based on the partnership between museum educators, researchers and artists. The museum programs/workshops mainly aimed to facilitate the development of young people’s critical-thinking skills (e.g. Burchenal and Grohe 2007 ; Luke et al. 2007 ). The dominant activity in facilitating children’s learning in art museums/galleries was hands-on activity (see Burchenal and Grohe 2007 ; Krakowski 2012 ; Mallos 2012 ; Milutinović and Gajić 2010 ). As stated by Mallos ( 2012 ), hands-on activities in art museums/galleries encourage children to make connections to ideas or materials with which the artists worked and, by relying on a child’s experience, deepen his/her understanding about the artwork.

In order to understand the work of art and to freely express themselves, children engaged in diverse hands-on activities in the reviewed studies. The program designers often utilised hands-on activities as part of a strategy that can be positioned in the overlapping child–environment–adults/peers area of our framework. For example, Mallos ( 2012 ) described strategies useful for cultivating children’s encounters with art which are very similar to the three-mode strategy ‘Listen, Look & Do’ applied in history museums. Mallos used a ‘three-window approach’ which consisted of: the experiential window, or hands-on approach—inviting children to touch, manipulate or respond using bodily movements; the narrative window—allowing children to experience an object through the medium of story; and the aesthetic window—focusing on having children describe the visual and aesthetic qualities of the object encountered.

In two reviewed studies, the artist (along with the museum educators and parents) played an essential role in facilitating children’s learning. For example, Mallos ( 2012 ) describes how gallery members collaborated with more than 100 local and international contemporary artists to develop and take part in various exhibitions, installations and workshops for families. Weier ( 2004 ) however, suggests that, by allowing children to take the lead (i.e. act as a tour guide for parents or peers), art museums can provide opportunities for self-expression, choice and control during visits. Weier ( 2004 ), also noted that, by allowing young children the opportunity to be tour guides, they can access art on their own level and terms, in contrast to learning an expected set of meanings or accepting another’s interpretation of an artwork as the only possibility. Once children experience a sense of accessibility, enjoyment and motivation when viewing and discussing artworks on their own terms, they are more likely to be ready to have their conversations extended to include visual arts concepts.

By emphasising the role of the adults and peers in guiding children’s learning and their interactions, Weier ( 2004 ) represented the child–adults/peers interactivity area of our framework. The advantage of allowing children to take the lead in museum learning was also supported by the research of Falk and Dierking ( 2000 ) who found that children are more motivated when having choice and control over their museum encounters. Weier ( 2004 ) also underlined the importance of having a supportive and responsive adult (i.e. curator, artist, parent) during child-led tours build on children’s conversations and introduce the language and concepts of the visual arts or the materials used. The information about the artwork should only be used as a trigger for discovery, which assists children to form hypotheses, create stories, build meanings and make connections based on personal experiences and feelings about the work.

Suggestions about introducing visual arts language and concepts at appropriate junctures in the child’s dialogue, using a range of “scaffolding behaviors” (Weier 2000 , p. 1999), include:

focusing children’s attention on a particular aspect of the artwork

asking open-ended questions

providing explanations

recalling facts or experiences to encourage associations

making suggestions; initiating a line of thinking that children can follow

hypothesising (or imagining or wondering) to spark curiosity and encourage further exploration, and

prompting with cues to support divergent thinking; and posing problems (Weier 2000 , 2004 ).

Burchenal and Grohe ( 2007 ) provide one example of prompting through the study of Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS)—a beneficial approach for use in both the classroom and museum settings when seeking to promote the development of critical-thinking skills. By concentrating on conversational interactions between a museum educator and children (child–adults/peers interactivity), VTS starts with questions as prompts for children, encouraging them to provide evidence for their ideas. By carefully observing and discussing works of art, students had the opportunity to apply previous experiences and knowledge to make meaning of artwork on their own terms.

A possible model for the successful integration of multisensory enriched activities in museums is presented by Milutinović and Gajić ( 2010 ) through the six-month educational program ‘Feel the art’ in the Gallery of Matica srpska in Serbia. (The first author of this paper contributed to this program.) With the goal of encouraging children to employ all senses when confronted with artwork, this museum program provides an example of the child–environment–adults/peers type of interactivity identified in our framework. For example, children recognised what, from the paintings, could produce sounds (e.g. sea waves, an erupting volcano, birds, frogs, rustling leaves) and imitated the sounds with musical instruments. Results revealed children’s descriptions of paintings or objects that reflected interest development and the capability to participate in multisensory art activities.

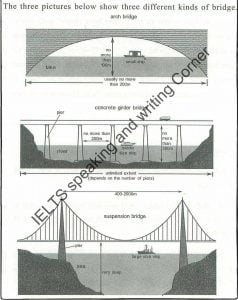

In order to understand artwork, Mallos ( 2012 ) recommends that children are incorporated into the artwork. For example, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s (as cited in Mallos 2012 ) encouraged children to freely ‘obliterate’ a bare environment by sticking dots everywhere. In this way, children could take part in the art-making experience and see themselves through the screen of dots that was the subject of artist’s work. Mallos ( 2012 ) also described an activity in which children were asked to design and construct a bridge with fine pieces of cane and masking tape using artists’ line drawings of various bridges. By this immediate interaction with the museum environment, these activities present an example of the child–environment interactivity.