10 Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

A case study in academic research is a detailed and in-depth examination of a specific instance or event, generally conducted through a qualitative approach to data.

The most common case study definition that I come across is is Robert K. Yin’s (2003, p. 13) quote provided below:

“An empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

Researchers conduct case studies for a number of reasons, such as to explore complex phenomena within their real-life context, to look at a particularly interesting instance of a situation, or to dig deeper into something of interest identified in a wider-scale project.

While case studies render extremely interesting data, they have many limitations and are not suitable for all studies. One key limitation is that a case study’s findings are not usually generalizable to broader populations because one instance cannot be used to infer trends across populations.

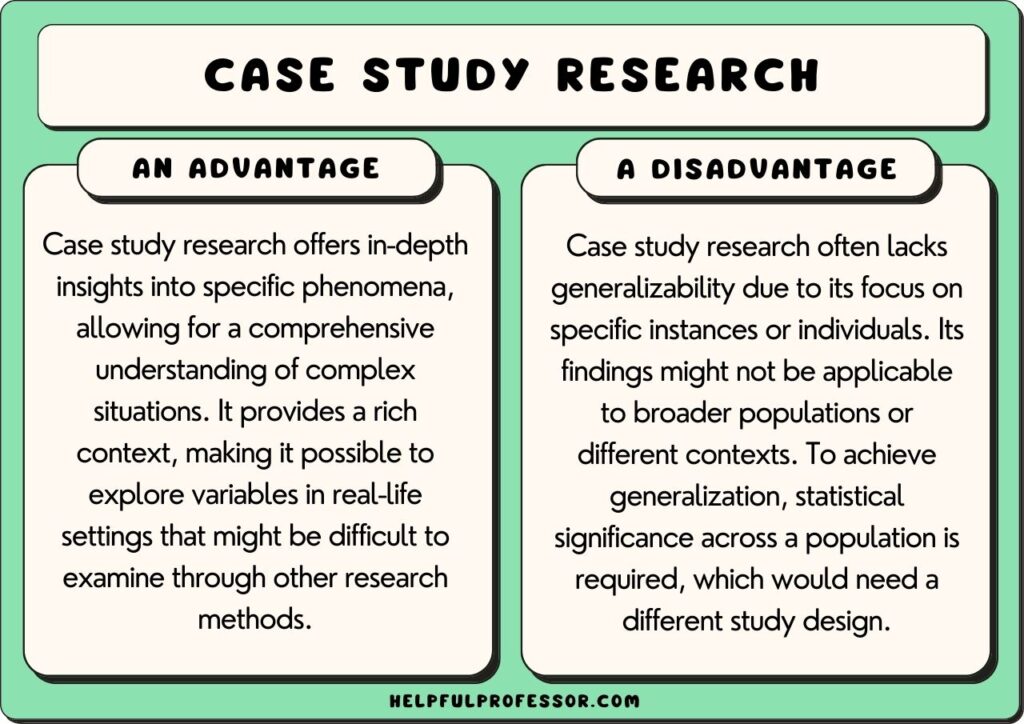

Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

1. in-depth analysis of complex phenomena.

Case study design allows researchers to delve deeply into intricate issues and situations.

By focusing on a specific instance or event, researchers can uncover nuanced details and layers of understanding that might be missed with other research methods, especially large-scale survey studies.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue,

“It allows that particular event to be studies in detail so that its unique qualities may be identified.”

This depth of analysis can provide rich insights into the underlying factors and dynamics of the studied phenomenon.

2. Holistic Understanding

Building on the above point, case studies can help us to understand a topic holistically and from multiple angles.

This means the researcher isn’t restricted to just examining a topic by using a pre-determined set of questions, as with questionnaires. Instead, researchers can use qualitative methods to delve into the many different angles, perspectives, and contextual factors related to the case study.

We can turn to Lee and Saunders (2017) again, who notes that case study researchers “develop a deep, holistic understanding of a particular phenomenon” with the intent of deeply understanding the phenomenon.

3. Examination of rare and Unusual Phenomena

We need to use case study methods when we stumble upon “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017) phenomena that would tend to be seen as mere outliers in population studies.

Take, for example, a child genius. A population study of all children of that child’s age would merely see this child as an outlier in the dataset, and this child may even be removed in order to predict overall trends.

So, to truly come to an understanding of this child and get insights into the environmental conditions that led to this child’s remarkable cognitive development, we need to do an in-depth study of this child specifically – so, we’d use a case study.

4. Helps Reveal the Experiences of Marginalzied Groups

Just as rare and unsual cases can be overlooked in population studies, so too can the experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of marginalized groups.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue, “case studies are also extremely useful in helping the expression of the voices of people whose interests are often ignored.”

Take, for example, the experiences of minority populations as they navigate healthcare systems. This was for many years a “hidden” phenomenon, not examined by researchers. It took case study designs to truly reveal this phenomenon, which helped to raise practitioners’ awareness of the importance of cultural sensitivity in medicine.

5. Ideal in Situations where Researchers cannot Control the Variables

Experimental designs – where a study takes place in a lab or controlled environment – are excellent for determining cause and effect . But not all studies can take place in controlled environments (Tetnowski, 2015).

When we’re out in the field doing observational studies or similar fieldwork, we don’t have the freedom to isolate dependent and independent variables. We need to use alternate methods.

Case studies are ideal in such situations.

A case study design will allow researchers to deeply immerse themselves in a setting (potentially combining it with methods such as ethnography or researcher observation) in order to see how phenomena take place in real-life settings.

6. Supports the generation of new theories or hypotheses

While large-scale quantitative studies such as cross-sectional designs and population surveys are excellent at testing theories and hypotheses on a large scale, they need a hypothesis to start off with!

This is where case studies – in the form of grounded research – come in. Often, a case study doesn’t start with a hypothesis. Instead, it ends with a hypothesis based upon the findings within a singular setting.

The deep analysis allows for hypotheses to emerge, which can then be taken to larger-scale studies in order to conduct further, more generalizable, testing of the hypothesis or theory.

7. Reveals the Unexpected

When a largescale quantitative research project has a clear hypothesis that it will test, it often becomes very rigid and has tunnel-vision on just exploring the hypothesis.

Of course, a structured scientific examination of the effects of specific interventions targeted at specific variables is extermely valuable.

But narrowly-focused studies often fail to shine a spotlight on unexpected and emergent data. Here, case studies come in very useful. Oftentimes, researchers set their eyes on a phenomenon and, when examining it closely with case studies, identify data and come to conclusions that are unprecedented, unforeseen, and outright surprising.

As Lars Meier (2009, p. 975) marvels, “where else can we become a part of foreign social worlds and have the chance to become aware of the unexpected?”

Disadvantages

1. not usually generalizable.

Case studies are not generalizable because they tend not to look at a broad enough corpus of data to be able to infer that there is a trend across a population.

As Yang (2022) argues, “by definition, case studies can make no claims to be typical.”

Case studies focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. They explore the context, nuances, and situational factors that have come to bear on the case study. This is really useful for bringing to light important, new, and surprising information, as I’ve already covered.

But , it’s not often useful for generating data that has validity beyond the specific case study being examined.

2. Subjectivity in interpretation

Case studies usually (but not always) use qualitative data which helps to get deep into a topic and explain it in human terms, finding insights unattainable by quantitative data.

But qualitative data in case studies relies heavily on researcher interpretation. While researchers can be trained and work hard to focus on minimizing subjectivity (through methods like triangulation), it often emerges – some might argue it’s innevitable in qualitative studies.

So, a criticism of case studies could be that they’re more prone to subjectivity – and researchers need to take strides to address this in their studies.

3. Difficulty in replicating results

Case study research is often non-replicable because the study takes place in complex real-world settings where variables are not controlled.

So, when returning to a setting to re-do or attempt to replicate a study, we often find that the variables have changed to such an extent that replication is difficult. Furthermore, new researchers (with new subjective eyes) may catch things that the other readers overlooked.

Replication is even harder when researchers attempt to replicate a case study design in a new setting or with different participants.

Comprehension Quiz for Students

Question 1: What benefit do case studies offer when exploring the experiences of marginalized groups?

a) They provide generalizable data. b) They help express the voices of often-ignored individuals. c) They control all variables for the study. d) They always start with a clear hypothesis.

Question 2: Why might case studies be considered ideal for situations where researchers cannot control all variables?

a) They provide a structured scientific examination. b) They allow for generalizability across populations. c) They focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. d) They allow for deep immersion in real-life settings.

Question 3: What is a primary disadvantage of case studies in terms of data applicability?

a) They always focus on the unexpected. b) They are not usually generalizable. c) They support the generation of new theories. d) They provide a holistic understanding.

Question 4: Why might case studies be considered more prone to subjectivity?

a) They always use quantitative data. b) They heavily rely on researcher interpretation, especially with qualitative data. c) They are always replicable. d) They look at a broad corpus of data.

Question 5: In what situations are experimental designs, such as those conducted in labs, most valuable?

a) When there’s a need to study rare and unusual phenomena. b) When a holistic understanding is required. c) When determining cause-and-effect relationships. d) When the study focuses on marginalized groups.

Question 6: Why is replication challenging in case study research?

a) Because they always use qualitative data. b) Because they tend to focus on a broad corpus of data. c) Due to the changing variables in complex real-world settings. d) Because they always start with a hypothesis.

Lee, B., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2017). Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications.

Meir, L. (2009). Feasting on the Benefits of Case Study Research. In Mills, A. J., Wiebe, E., & Durepos, G. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (Vol. 2). London: SAGE Publications.

Tetnowski, J. (2015). Qualitative case study research design. Perspectives on fluency and fluency disorders , 25 (1), 39-45. ( Source )

Yang, S. L. (2022). The War on Corruption in China: Local Reform and Innovation . Taylor & Francis.

Yin, R. (2003). Case Study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Number Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Word Games for Kids (Free and Easy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 25 Outdoor Games for Kids

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 50 Incentives to Give to Students

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Case Study Method – 18 Advantages and Disadvantages

The case study method uses investigatory research as a way to collect data about specific demographics. This approach can apply to individuals, businesses, groups, or events. Each participant receives an equal amount of participation, offering information for collection that can then find new insights into specific trends, ideas, of hypotheses.

Interviews and research observation are the two standard methods of data collection used when following the case study method.

Researchers initially developed the case study method to develop and support hypotheses in clinical medicine. The benefits found in these efforts led the approach to transition to other industries, allowing for the examination of results through proposed decisions, processes, or outcomes. Its unique approach to information makes it possible for others to glean specific points of wisdom that encourage growth.

Several case study method advantages and disadvantages can appear when researchers take this approach.

List of the Advantages of the Case Study Method

1. It requires an intensive study of a specific unit. Researchers must document verifiable data from direct observations when using the case study method. This work offers information about the input processes that go into the hypothesis under consideration. A casual approach to data-gathering work is not effective if a definitive outcome is desired. Each behavior, choice, or comment is a critical component that can verify or dispute the ideas being considered.

Intensive programs can require a significant amount of work for researchers, but it can also promote an improvement in the data collected. That means a hypothesis can receive immediate verification in some situations.

2. No sampling is required when following the case study method. This research method studies social units in their entire perspective instead of pulling individual data points out to analyze them. That means there is no sampling work required when using the case study method. The hypothesis under consideration receives support because it works to turn opinions into facts, verifying or denying the proposals that outside observers can use in the future.

Although researchers might pay attention to specific incidents or outcomes based on generalized behaviors or ideas, the study itself won’t sample those situations. It takes a look at the “bigger vision” instead.

3. This method offers a continuous analysis of the facts. The case study method will look at the facts continuously for the social group being studied by researchers. That means there aren’t interruptions in the process that could limit the validity of the data being collected through this work. This advantage reduces the need to use assumptions when drawing conclusions from the information, adding validity to the outcome of the study over time. That means the outcome becomes relevant to both sides of the equation as it can prove specific suppositions or invalidate a hypothesis under consideration.

This advantage can lead to inefficiencies because of the amount of data being studied by researchers. It is up to the individuals involved in the process to sort out what is useful and meaningful and what is not.

4. It is a useful approach to take when formulating a hypothesis. Researchers will use the case study method advantages to verify a hypothesis under consideration. It is not unusual for the collected data to lead people toward the formulation of new ideas after completing this work. This process encourages further study because it allows concepts to evolve as people do in social or physical environments. That means a complete data set can be gathered based on the skills of the researcher and the honesty of the individuals involved in the study itself.

Although this approach won’t develop a societal-level evaluation of a hypothesis, it can look at how specific groups will react in various circumstances. That information can lead to a better decision-making process in the future for everyone involved.

5. It provides an increase in knowledge. The case study method provides everyone with analytical power to increase knowledge. This advantage is possible because it uses a variety of methodologies to collect information while evaluating a hypothesis. Researchers prefer to use direct observation and interviews to complete their work, but it can also advantage through the use of questionnaires. Participants might need to fill out a journal or diary about their experiences that can be used to study behaviors or choices.

Some researchers incorporate memory tests and experimental tasks to determine how social groups will interact or respond in specific situations. All of this data then works to verify the possibilities that a hypothesis proposes.

6. The case study method allows for comparisons. The human experience is one that is built on individual observations from group situations. Specific demographics might think, act, or respond in particular ways to stimuli, but each person in that group will also contribute a small part to the whole. You could say that people are sponges that collect data from one another every day to create individual outcomes.

The case study method allows researchers to take the information from each demographic for comparison purposes. This information can then lead to proposals that support a hypothesis or lead to its disruption.

7. Data generalization is possible using the case study method. The case study method provides a foundation for data generalization, allowing researches to illustrate their statistical findings in meaningful ways. It puts the information into a usable format that almost anyone can use if they have the need to evaluate the hypothesis under consideration. This process makes it easier to discover unusual features, unique outcomes, or find conclusions that wouldn’t be available without this method. It does an excellent job of identifying specific concepts that relate to the proposed ideas that researchers were verifying through their work.

Generalization does not apply to a larger population group with the case study method. What researchers can do with this information is to suggest a predictable outcome when similar groups are placed in an equal situation.

8. It offers a comprehensive approach to research. Nothing gets ignored when using the case study method to collect information. Every person, place, or thing involved in the research receives the complete attention of those seeking data. The interactions are equal, which means the data is comprehensive and directly reflective of the group being observed.

This advantage means that there are fewer outliers to worry about when researching an idea, leading to a higher level of accuracy in the conclusions drawn by the researchers.

9. The identification of deviant cases is possible with this method. The case study method of research makes it easier to identify deviant cases that occur in each social group. These incidents are units (people) that behave in ways that go against the hypothesis under consideration. Instead of ignoring them like other options do when collecting data, this approach incorporates the “rogue” behavior to understand why it exists in the first place.

This advantage makes the eventual data and conclusions gathered more reliable because it incorporates the “alternative opinion” that exists. One might say that the case study method places as much emphasis on the yin as it does the yang so that the whole picture becomes available to the outside observer.

10. Questionnaire development is possible with the case study method. Interviews and direct observation are the preferred methods of implementing the case study method because it is cheap and done remotely. The information gathered by researchers can also lead to farming questionnaires that can farm additional data from those being studied. When all of the data resources come together, it is easier to formulate a conclusion that accurately reflects the demographics.

Some people in the case study method may try to manipulate the results for personal reasons, but this advantage makes it possible to identify this information readily. Then researchers can look into the thinking that goes into the dishonest behaviors observed.

List of the Disadvantages of the Case Study Method

1. The case study method offers limited representation. The usefulness of the case study method is limited to a specific group of representatives. Researchers are looking at a specific demographic when using this option. That means it is impossible to create any generalization that applies to the rest of society, an organization, or a larger community with this work. The findings can only apply to other groups caught in similar circumstances with the same experiences.

It is useful to use the case study method when attempting to discover the specific reasons why some people behave in a specific way. If researchers need something more generalized, then a different method must be used.

2. No classification is possible with the case study method. This disadvantage is also due to the sample size in the case study method. No classification is possible because researchers are studying such a small unit, group, or demographic. It can be an inefficient process since the skills of the researcher help to determine the quality of the data being collected to verify the validity of a hypothesis. Some participants may be unwilling to answer or participate, while others might try to guess at the outcome to support it.

Researchers can get trapped in a place where they explore more tangents than the actual hypothesis with this option. Classification can occur within the units being studied, but this data cannot extrapolate to other demographics.

3. The case study method still offers the possibility of errors. Each person has an unconscious bias that influences their behaviors and choices. The case study method can find outliers that oppose a hypothesis fairly easily thanks to its emphasis on finding facts, but it is up to the researchers to determine what information qualifies for this designation. If the results from the case study method are surprising or go against the opinion of participating individuals, then there is still the possibility that the information will not be 100% accurate.

Researchers must have controls in place that dictate how data gathering work occurs. Without this limitation in place, the results of the study cannot be guaranteed because of the presence of bias.

4. It is a subjective method to use for research. Although the purpose of the case study method of research is to gather facts, the foundation of what gets gathered is still based on opinion. It uses the subjective method instead of the objective one when evaluating data, which means there can be another layer of errors in the information to consider.

Imagine that a researcher interprets someone’s response as “angry” when performing direct observation, but the individual was feeling “shame” because of a decision they made. The difference between those two emotions is profound, and it could lead to information disruptions that could be problematic to the eventual work of hypothesis verification.

5. The processes required by the case study method are not useful for everyone. The case study method uses a person’s memories, explanations, and records from photographs and diaries to identify interactions on influences on psychological processes. People are given the chance to describe what happens in the world around them as a way for researchers to gather data. This process can be an advantage in some industries, but it can also be a worthless approach to some groups.

If the social group under study doesn’t have the information, knowledge, or wisdom to provide meaningful data, then the processes are no longer useful. Researchers must weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the case study method before starting their work to determine if the possibility of value exists. If it does not, then a different method may be necessary.

6. It is possible for bias to form in the data. It’s not just an unconscious bias that can form in the data when using the case study method. The narrow study approach can lead to outright discrimination in the data. Researchers can decide to ignore outliers or any other information that doesn’t support their hypothesis when using this method. The subjective nature of this approach makes it difficult to challenge the conclusions that get drawn from this work, and the limited pool of units (people) means that duplication is almost impossible.

That means unethical people can manipulate the results gathered by the case study method to their own advantage without much accountability in the process.

7. This method has no fixed limits to it. This method of research is highly dependent on situational circumstances rather than overarching societal or corporate truths. That means the researcher has no fixed limits of investigation. Even when controls are in place to limit bias or recommend specific activities, the case study method has enough flexibility built into its structures to allow for additional exploration. That means it is possible for this work to continue indefinitely, gathering data that never becomes useful.

Scientists began to track the health of 268 sophomores at Harvard in 1938. The Great Depression was in its final years at that point, so the study hoped to reveal clues that lead to happy and healthy lives. It continues still today, now incorporating the children of the original participants, providing over 80 years of information to sort through for conclusions.

8. The case study method is time-consuming and expensive. The case study method can be affordable in some situations, but the lack of fixed limits and the ability to pursue tangents can make it a costly process in most situations. It takes time to gather the data in the first place, and then researchers must interpret the information received so that they can use it for hypothesis evaluation. There are other methods of data collection that can be less expensive and provide results faster.

That doesn’t mean the case study method is useless. The individualization of results can help the decision-making process advance in a variety of industries successfully. It just takes more time to reach the appropriate conclusion, and that might be a resource that isn’t available.

The advantages and disadvantages of the case study method suggest that the helpfulness of this research option depends on the specific hypothesis under consideration. When researchers have the correct skills and mindset to gather data accurately, then it can lead to supportive data that can verify ideas with tremendous accuracy.

This research method can also be used unethically to produce specific results that can be difficult to challenge.

When bias enters into the structure of the case study method, the processes become inefficient, inaccurate, and harmful to the hypothesis. That’s why great care must be taken when designing a study with this approach. It might be a labor-intensive way to develop conclusions, but the outcomes are often worth the investments needed.

Case Study: Types, Advantages And Disadvantages

Case Study: Types, Advantages And Disadvantages

Case study is both method and tool for research. Case study is the intensive study of a phenomenon, but it gives subjective information rather than objective. It gives detailed knowledge about the phenomena and is not able to generalize beyond the knowledge.

Case studies aim to analyze specific issues within the boundaries of a specific environment, situation or organization. According to its design, case study research method can be divided into three categories: explanatory, descriptive and exploratory.

Explanatory case studies aim to answer ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions with little control on behalf of the researcher over occurrence of events. This type of case study focuses on phenomena within the contexts of real-life situations.

Descriptive case studies aim to analyze the sequence of interpersonal events after a certain amount of time has passed. Case studies belonging to this category usually describe culture or sub-culture, and they attempt to discover the key phenomena.

Exploratory case studies aim to find answers to the questions of ‘what’ or ‘who’. Exploratory case study data collection method is often accompanied by additional data collection method(s) such as interviews, questionnaires, experiments etc.

DEFINITION OF CASE STUDY

The case study or case history method is not a newer thing, but it is a linear descendent of very ancient methods of sociological description and generalization namely, the ‘parable’, the ‘allegory’, the ‘story’ and the ‘novel’.

According to P.V. Young . “A fairly exhaustive study of a person or group is called a life of case history.”

Thus, the case study is more intensive in nature; the field of study is comparatively limited but has more depth in it.

TYPES OF CASE STUDY

Six types of case studies are conducted which are as follows:

Community Studies: The community study is a careful description and analysis of a group of people living together in a particular geographic location in a corporative way. The community study deals with such elements of the community as location, appearance, prevailing economic activity, climate and natural sources, historical development, how the people live, the social structure, goals and life values, an evaluation of the social institutions within the community that meet the human needs etc. Such studies are case studies, with the community serving as the case under investigation.

Casual Comparative Studies: Another type of study seeks to find the answers to the problems through the analysis of casual relationships. What factors seem to be associated with certain occurrences, conditions or types of behaviour? By the methodology of descriptive research, the relative importance of these factors may be investigated.

Activity Analysis: The analysis of the activities or processes that an individual is called upon to perform is important, both in industry and in various types of social agencies. This process of analysis is appropriate in any field of work and at all levels of responsibility. In social system, the roles of superintendent, the principal, the teacher and the custodian have been carefully analyzed to discover what these individuals do and need to be able to do.

Content or Document Analysis: Content analysis, sometimes known as document analysis. Deals with the systematic examination of current records or documents as sources of data. In documentary analysis, the following may be used as sources of data: official records and reports, printed forms, text-books, reference books, letters, autobiographies diaries, pictures, films and cartoons etc . But in using documentary sources, one must bear in mind the fact that data appearing in print is not necessarily trustworthy. This content or document analysis should serve a useful purpose in research, adding important knowledge to a field to study or yielding information that is helpful in evaluating and improving social or educational practices.

A Follow-up Study: A follow-up study investigates individuals who have left an institution after having completed programme, a treatment or a course of study, to know what has been the impact of the institutions and its programme upon them. By examining their status or seeking their opinions, one may get some idea of the adequacy or inadequacy of the institutes programme. Studies of this type enable an institution to evaluate various aspects of its programme in the light of actual results.

Trend Studies: The trend or predictive study is an interesting application of the descriptive method. In essence, it is based upon a longitudinal consideration of recorded data, indicating what has been happening in the past, what does the present situation reveal and on the basis of these data, what will be likely to happen in the future.

Whatever type of case study is to conduct, it’s important to first identify the purpose, goals, and approach for conducting methodologically sound research.

ADVANTAGES OF CASE STUDY

The main points of advantages of case study are given below:

Formation of valid hypothesis: Case study helps in formulating valid hypothesis. Once the various cases are extensively studied and analyze, the researcher can deduce various generalizations, which may be developed into useful hypotheses. It is admitted by all that the study of relevant literature and case study form the only potent sources of hypothesis.

Useful in framing questionnaires and schedules: Case study is of great help in framing questionnaires, schedules or other forms. When a questionnaire is prepared after thorough case study the peculiarities of the group as well as individual units, become known also the type of response likely to be available, liking and aversions of the people. This helps in getting prompt response.

Sampling: Case study is of help in the stratification of the sample. By studying the individual units the researcher can put them in definite classes or types and thereby facilitate the perfect stratification of the sample.

Location of deviant cases: The case study makes it possible to locate deviant cases. There exists a general tendency to ignore them, but for scientific analysis, they are very important. The analysis of such cases is of valuable help in clarifying the theory itself.

Study of process: In cases where the problem under study constitutes a process and not one incident e.g. courtship process, clique formation etc., case study is the appropriate method as the case data is essential for valid study of such problems.

Enlarges experience: The range of personal experience of the researcher is enlarged by the case study on the other hand in statistical methods a narrow range of topics is selected, and the researcher’s knowledge is restricted to the particular aspect only.

Qualitative analysis in actual situation: Case study enables the establishment of the significance of the recorded data when the individual is alive and later on within the life of the classes of individuals. The researcher has the opportunity to come into contact with different classes of people and he is in a position to watch their life and hear their experiences. This provides him with an opportunity to acquire experiences of such life situations which he is never expected to lead.

This discussion highlights the advantages of the case data in social research. Social scientists developed the techniques to make it more perfect and remove the chances of bias.

LIMITATIONS/DISADVANTAGES OF CASE STUDY METHOD

Subjective bias: Research subjectivity in collecting data for supporting or refuting a particular explanation, personal view of investigation influences the findings and conclusion of the study.

Problem of objectivity: Due to excessive association with the social unit under investigation the researcher may develop self-justificatory data which are far from being factual.

Difficulty in comparison: Because of wide variations among human beings in terms of their response and behaviour, attitudes and values, social setting and circumstances, etc., the researcher actually finds it difficult to trace out two social units which are identical in all respects. This hinders proper comparison of cases.

A time, energy and money consuming method: The preparation of a case history involves a lot of time and expenditure of human energy, therefore, there is every possibility that most of the cases may get stray. Due to such difficulties, only a few researchers can afford to case study method.

Time span: Long time span may be another factor that is likely to distort the information provided by the social unit to the researcher.

Unreliable source material: The two major sources of case study are: Personal documents and life history. But in both these cases, the records or the own experience of the social units may not present a true picture. On the contrary, the social unit may try to suppress his unpleasant facts or add colour to them. As a result, the conclusions drawn do not give a true picture and dependable findings.

Scope for wrong conclusions: The case study is laden with inaccurate observation, wrong inferences, faulty reporting, memory failure, repression or omission of unpleasant facts in an unconscious manner, dramatization of facts, more imaginary description, and difficulty in choosing a case typical of the group. All these problems provide the researcher with every possibility of drawing wrong conclusions and errors.

Case studies are complex because they generally involve multiple sources of data, may include multiple cases within a study and produce large amounts of data for analysis. Researchers from many disciplines use the case study method to build upon theory, to produce new theory, to dispute or challenge theory, to explain a situation, to provide a basis to apply solutions to situations, to explore, or to describe an object or phenomenon. The advantages of the case study method are its applicability to real-life, contemporary, human situations and its public accessibility through written reports. Case study results relate directly to the common readers everyday experience and facilitate an understanding of complex real-life situations.

__________________________________________________________________________

Research Methodology Methods and Techniques~C. R. Kothari (p.113) - Link

Fundamental of Research Methodology and Statistics~Yogesh Kumar Singh (Chapter–10: Case Study Method p. 147) - Link

Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches~W. Lawrence Neuman (p.42) - Link

The Basics of Social Research~Earl Babbie (p.280) - Link

Social Science Research Principles, Methods, and Practices~Anol Bhattacherjee (93) - Link

PREPARING A CASE STUDY: A Guide for Designing and Conducting a Case Study for Evaluation Input - Link

A Case in Case Study Methodology - Link

Case Study Method - Link1 & Link 2

Unit-4 Case Study - Link

Case study as a research method - Link

Case_Study~Tanya Sammut-Bonnici and John McGee - Link

Post a Comment

Contact form.

Home » Pros and Cons » 12 Case Study Method Advantages and Disadvantages

12 Case Study Method Advantages and Disadvantages

A case study is an investigation into an individual circumstance. The investigation may be of a single person, business, event, or group. The investigation involves collecting in-depth data about the individual entity through the use of several collection methods. Interviews and observation are two of the most common forms of data collection used.

The case study method was originally developed in the field of clinical medicine. It has expanded since to other industries to examine key results, either positive or negative, that were received through a specific set of decisions. This allows for the topic to be researched with great detail, allowing others to glean knowledge from the information presented.

Here are the advantages and disadvantages of using the case study method.

List of the Advantages of the Case Study Method

1. it turns client observations into useable data..

Case studies offer verifiable data from direct observations of the individual entity involved. These observations provide information about input processes. It can show the path taken which led to specific results being generated. Those observations make it possible for others, in similar circumstances, to potentially replicate the results discovered by the case study method.

2. It turns opinion into fact.

Case studies provide facts to study because you’re looking at data which was generated in real-time. It is a way for researchers to turn their opinions into information that can be verified as fact because there is a proven path of positive or negative development. Singling out a specific incident also provides in-depth details about the path of development, which gives it extra credibility to the outside observer.

3. It is relevant to all parties involved.

Case studies that are chosen well will be relevant to everyone who is participating in the process. Because there is such a high level of relevance involved, researchers are able to stay actively engaged in the data collection process. Participants are able to further their knowledge growth because there is interest in the outcome of the case study. Most importantly, the case study method essentially forces people to make a decision about the question being studied, then defend their position through the use of facts.

4. It uses a number of different research methodologies.

The case study method involves more than just interviews and direct observation. Case histories from a records database can be used with this method. Questionnaires can be distributed to participants in the entity being studies. Individuals who have kept diaries and journals about the entity being studied can be included. Even certain experimental tasks, such as a memory test, can be part of this research process.

5. It can be done remotely.

Researchers do not need to be present at a specific location or facility to utilize the case study method. Research can be obtained over the phone, through email, and other forms of remote communication. Even interviews can be conducted over the phone. That means this method is good for formative research that is exploratory in nature, even if it must be completed from a remote location.

6. It is inexpensive.

Compared to other methods of research, the case study method is rather inexpensive. The costs associated with this method involve accessing data, which can often be done for free. Even when there are in-person interviews or other on-site duties involved, the costs of reviewing the data are minimal.

7. It is very accessible to readers.

The case study method puts data into a usable format for those who read the data and note its outcome. Although there may be perspectives of the researcher included in the outcome, the goal of this method is to help the reader be able to identify specific concepts to which they also relate. That allows them to discover unusual features within the data, examine outliers that may be present, or draw conclusions from their own experiences.

List of the Disadvantages of the Case Study Method

1. it can have influence factors within the data..

Every person has their own unconscious bias. Although the case study method is designed to limit the influence of this bias by collecting fact-based data, it is the collector of the data who gets to define what is a “fact” and what is not. That means the real-time data being collected may be based on the results the researcher wants to see from the entity instead. By controlling how facts are collected, a research can control the results this method generates.

2. It takes longer to analyze the data.

The information collection process through the case study method takes much longer to collect than other research options. That is because there is an enormous amount of data which must be sifted through. It’s not just the researchers who can influence the outcome in this type of research method. Participants can also influence outcomes by given inaccurate or incomplete answers to questions they are asked. Researchers must verify the information presented to ensure its accuracy, and that takes time to complete.

3. It can be an inefficient process.

Case study methods require the participation of the individuals or entities involved for it to be a successful process. That means the skills of the researcher will help to determine the quality of information that is being received. Some participants may be quiet, unwilling to answer even basic questions about what is being studied. Others may be overly talkative, exploring tangents which have nothing to do with the case study at all. If researchers are unsure of how to manage this process, then incomplete data is often collected.

4. It requires a small sample size to be effective.

The case study method requires a small sample size for it to yield an effective amount of data to be analyzed. If there are different demographics involved with the entity, or there are different needs which must be examined, then the case study method becomes very inefficient.

5. It is a labor-intensive method of data collection.

The case study method requires researchers to have a high level of language skills to be successful with data collection. Researchers must be personally involved in every aspect of collecting the data as well. From reviewing files or entries personally to conducting personal interviews, the concepts and themes of this process are heavily reliant on the amount of work each researcher is willing to put into things.

These case study method advantages and disadvantages offer a look at the effectiveness of this research option. With the right skill set, it can be used as an effective tool to gather rich, detailed information about specific entities. Without the right skill set, the case study method becomes inefficient and inaccurate.

Related Posts:

- 25 Best Ways to Overcome the Fear of Failure

- Monroe's Motivated Sequence Explained [with Examples]

- 21 Most Effective Bundle Pricing Strategies with Examples

- Force Field Analysis Explained with Examples

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

The case study approach

Sarah crowe.

1 Division of Primary Care, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK

Kathrin Cresswell

2 Centre for Population Health Sciences, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Ann Robertson

3 School of Health in Social Science, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

Anthony Avery

Aziz sheikh.

The case study approach allows in-depth, multi-faceted explorations of complex issues in their real-life settings. The value of the case study approach is well recognised in the fields of business, law and policy, but somewhat less so in health services research. Based on our experiences of conducting several health-related case studies, we reflect on the different types of case study design, the specific research questions this approach can help answer, the data sources that tend to be used, and the particular advantages and disadvantages of employing this methodological approach. The paper concludes with key pointers to aid those designing and appraising proposals for conducting case study research, and a checklist to help readers assess the quality of case study reports.

Introduction

The case study approach is particularly useful to employ when there is a need to obtain an in-depth appreciation of an issue, event or phenomenon of interest, in its natural real-life context. Our aim in writing this piece is to provide insights into when to consider employing this approach and an overview of key methodological considerations in relation to the design, planning, analysis, interpretation and reporting of case studies.

The illustrative 'grand round', 'case report' and 'case series' have a long tradition in clinical practice and research. Presenting detailed critiques, typically of one or more patients, aims to provide insights into aspects of the clinical case and, in doing so, illustrate broader lessons that may be learnt. In research, the conceptually-related case study approach can be used, for example, to describe in detail a patient's episode of care, explore professional attitudes to and experiences of a new policy initiative or service development or more generally to 'investigate contemporary phenomena within its real-life context' [ 1 ]. Based on our experiences of conducting a range of case studies, we reflect on when to consider using this approach, discuss the key steps involved and illustrate, with examples, some of the practical challenges of attaining an in-depth understanding of a 'case' as an integrated whole. In keeping with previously published work, we acknowledge the importance of theory to underpin the design, selection, conduct and interpretation of case studies[ 2 ]. In so doing, we make passing reference to the different epistemological approaches used in case study research by key theoreticians and methodologists in this field of enquiry.

This paper is structured around the following main questions: What is a case study? What are case studies used for? How are case studies conducted? What are the potential pitfalls and how can these be avoided? We draw in particular on four of our own recently published examples of case studies (see Tables Tables1, 1 , ,2, 2 , ,3 3 and and4) 4 ) and those of others to illustrate our discussion[ 3 - 7 ].

Example of a case study investigating the reasons for differences in recruitment rates of minority ethnic people in asthma research[ 3 ]

| Minority ethnic people experience considerably greater morbidity from asthma than the White majority population. Research has shown however that these minority ethnic populations are likely to be under-represented in research undertaken in the UK; there is comparatively less marginalisation in the US. |

| To investigate approaches to bolster recruitment of South Asians into UK asthma studies through qualitative research with US and UK researchers, and UK community leaders. |

| Single intrinsic case study |

| Centred on the issue of recruitment of South Asian people with asthma. |

| In-depth interviews were conducted with asthma researchers from the UK and US. A supplementary questionnaire was also provided to researchers. |

| Framework approach. |

| Barriers to ethnic minority recruitment were found to centre around: |

| 1. The attitudes of the researchers' towards inclusion: The majority of UK researchers interviewed were generally supportive of the idea of recruiting ethnically diverse participants but expressed major concerns about the practicalities of achieving this; in contrast, the US researchers appeared much more committed to the policy of inclusion. |

| 2. Stereotypes and prejudices: We found that some of the UK researchers' perceptions of ethnic minorities may have influenced their decisions on whether to approach individuals from particular ethnic groups. These stereotypes centred on issues to do with, amongst others, language barriers and lack of altruism. |

| 3. Demographic, political and socioeconomic contexts of the two countries: Researchers suggested that the demographic profile of ethnic minorities, their political engagement and the different configuration of the health services in the UK and the US may have contributed to differential rates. |

| 4. Above all, however, it appeared that the overriding importance of the US National Institute of Health's policy to mandate the inclusion of minority ethnic people (and women) had a major impact on shaping the attitudes and in turn the experiences of US researchers'; the absence of any similar mandate in the UK meant that UK-based researchers had not been forced to challenge their existing practices and they were hence unable to overcome any stereotypical/prejudicial attitudes through experiential learning. |

Example of a case study investigating the process of planning and implementing a service in Primary Care Organisations[ 4 ]

| Health work forces globally are needing to reorganise and reconfigure in order to meet the challenges posed by the increased numbers of people living with long-term conditions in an efficient and sustainable manner. Through studying the introduction of General Practitioners with a Special Interest in respiratory disorders, this study aimed to provide insights into this important issue by focusing on community respiratory service development. |

| To understand and compare the process of workforce change in respiratory services and the impact on patient experience (specifically in relation to the role of general practitioners with special interests) in a theoretically selected sample of Primary Care Organisations (PCOs), in order to derive models of good practice in planning and the implementation of a broad range of workforce issues. |

| Multiple-case design of respiratory services in health regions in England and Wales. |

| Four PCOs. |

| Face-to-face and telephone interviews, e-mail discussions, local documents, patient diaries, news items identified from local and national websites, national workshop. |

| Reading, coding and comparison progressed iteratively. |

| 1. In the screening phase of this study (which involved semi-structured telephone interviews with the person responsible for driving the reconfiguration of respiratory services in 30 PCOs), the barriers of financial deficit, organisational uncertainty, disengaged clinicians and contradictory policies proved insurmountable for many PCOs to developing sustainable services. A key rationale for PCO re-organisation in 2006 was to strengthen their commissioning function and those of clinicians through Practice-Based Commissioning. However, the turbulence, which surrounded reorganisation was found to have the opposite desired effect. |

| 2. Implementing workforce reconfiguration was strongly influenced by the negotiation and contest among local clinicians and managers about "ownership" of work and income. |

| 3. Despite the intention to make the commissioning system more transparent, personal relationships based on common professional interests, past work history, friendships and collegiality, remained as key drivers for sustainable innovation in service development. |

| It was only possible to undertake in-depth work in a selective number of PCOs and, even within these selected PCOs, it was not possible to interview all informants of potential interest and/or obtain all relevant documents. This work was conducted in the early stages of a major NHS reorganisation in England and Wales and thus, events are likely to have continued to evolve beyond the study period; we therefore cannot claim to have seen any of the stories through to their conclusion. |

Example of a case study investigating the introduction of the electronic health records[ 5 ]

| Healthcare systems globally are moving from paper-based record systems to electronic health record systems. In 2002, the NHS in England embarked on the most ambitious and expensive IT-based transformation in healthcare in history seeking to introduce electronic health records into all hospitals in England by 2010. |

| To describe and evaluate the implementation and adoption of detailed electronic health records in secondary care in England and thereby provide formative feedback for local and national rollout of the NHS Care Records Service. |

| A mixed methods, longitudinal, multi-site, socio-technical collective case study. |

| Five NHS acute hospital and mental health Trusts that have been the focus of early implementation efforts. |

| Semi-structured interviews, documentary data and field notes, observations and quantitative data. |

| Qualitative data were analysed thematically using a socio-technical coding matrix, combined with additional themes that emerged from the data. |

| 1. Hospital electronic health record systems have developed and been implemented far more slowly than was originally envisioned. |

| 2. The top-down, government-led standardised approach needed to evolve to admit more variation and greater local choice for hospitals in order to support local service delivery. |

| 3. A range of adverse consequences were associated with the centrally negotiated contracts, which excluded the hospitals in question. |

| 4. The unrealistic, politically driven, timeline (implementation over 10 years) was found to be a major source of frustration for developers, implementers and healthcare managers and professionals alike. |

| We were unable to access details of the contracts between government departments and the Local Service Providers responsible for delivering and implementing the software systems. This, in turn, made it difficult to develop a holistic understanding of some key issues impacting on the overall slow roll-out of the NHS Care Record Service. Early adopters may also have differed in important ways from NHS hospitals that planned to join the National Programme for Information Technology and implement the NHS Care Records Service at a later point in time. |

Example of a case study investigating the formal and informal ways students learn about patient safety[ 6 ]

| There is a need to reduce the disease burden associated with iatrogenic harm and considering that healthcare education represents perhaps the most sustained patient safety initiative ever undertaken, it is important to develop a better appreciation of the ways in which undergraduate and newly qualified professionals receive and make sense of the education they receive. | |

|---|---|

| To investigate the formal and informal ways pre-registration students from a range of healthcare professions (medicine, nursing, physiotherapy and pharmacy) learn about patient safety in order to become safe practitioners. | |

| Multi-site, mixed method collective case study. | |

| : Eight case studies (two for each professional group) were carried out in educational provider sites considering different programmes, practice environments and models of teaching and learning. | |

| Structured in phases relevant to the three knowledge contexts: | |

| Documentary evidence (including undergraduate curricula, handbooks and module outlines), complemented with a range of views (from course leads, tutors and students) and observations in a range of academic settings. | |

| Policy and management views of patient safety and influences on patient safety education and practice. NHS policies included, for example, implementation of the National Patient Safety Agency's , which encourages organisations to develop an organisational safety culture in which staff members feel comfortable identifying dangers and reporting hazards. | |

| The cultures to which students are exposed i.e. patient safety in relation to day-to-day working. NHS initiatives included, for example, a hand washing initiative or introduction of infection control measures. | |

| 1. Practical, informal, learning opportunities were valued by students. On the whole, however, students were not exposed to nor engaged with important NHS initiatives such as risk management activities and incident reporting schemes. | |

| 2. NHS policy appeared to have been taken seriously by course leaders. Patient safety materials were incorporated into both formal and informal curricula, albeit largely implicit rather than explicit. | |

| 3. Resource issues and peer pressure were found to influence safe practice. Variations were also found to exist in students' experiences and the quality of the supervision available. | |

| The curriculum and organisational documents collected differed between sites, which possibly reflected gatekeeper influences at each site. The recruitment of participants for focus group discussions proved difficult, so interviews or paired discussions were used as a substitute. | |

What is a case study?

A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences. A case study can be defined in a variety of ways (Table (Table5), 5 ), the central tenet being the need to explore an event or phenomenon in depth and in its natural context. It is for this reason sometimes referred to as a "naturalistic" design; this is in contrast to an "experimental" design (such as a randomised controlled trial) in which the investigator seeks to exert control over and manipulate the variable(s) of interest.

Definitions of a case study

| Author | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stake[ ] | (p.237) |

| Yin[ , , ] | (Yin 1999 p. 1211, Yin 1994 p. 13) |

| • | |

| • (Yin 2009 p18) | |

| Miles and Huberman[ ] | (p. 25) |

| Green and Thorogood[ ] | (p. 284) |

| George and Bennett[ ] | (p. 17)" |

Stake's work has been particularly influential in defining the case study approach to scientific enquiry. He has helpfully characterised three main types of case study: intrinsic , instrumental and collective [ 8 ]. An intrinsic case study is typically undertaken to learn about a unique phenomenon. The researcher should define the uniqueness of the phenomenon, which distinguishes it from all others. In contrast, the instrumental case study uses a particular case (some of which may be better than others) to gain a broader appreciation of an issue or phenomenon. The collective case study involves studying multiple cases simultaneously or sequentially in an attempt to generate a still broader appreciation of a particular issue.

These are however not necessarily mutually exclusive categories. In the first of our examples (Table (Table1), 1 ), we undertook an intrinsic case study to investigate the issue of recruitment of minority ethnic people into the specific context of asthma research studies, but it developed into a instrumental case study through seeking to understand the issue of recruitment of these marginalised populations more generally, generating a number of the findings that are potentially transferable to other disease contexts[ 3 ]. In contrast, the other three examples (see Tables Tables2, 2 , ,3 3 and and4) 4 ) employed collective case study designs to study the introduction of workforce reconfiguration in primary care, the implementation of electronic health records into hospitals, and to understand the ways in which healthcare students learn about patient safety considerations[ 4 - 6 ]. Although our study focusing on the introduction of General Practitioners with Specialist Interests (Table (Table2) 2 ) was explicitly collective in design (four contrasting primary care organisations were studied), is was also instrumental in that this particular professional group was studied as an exemplar of the more general phenomenon of workforce redesign[ 4 ].

What are case studies used for?

According to Yin, case studies can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur[ 1 ]. These can, for example, help to understand and explain causal links and pathways resulting from a new policy initiative or service development (see Tables Tables2 2 and and3, 3 , for example)[ 1 ]. In contrast to experimental designs, which seek to test a specific hypothesis through deliberately manipulating the environment (like, for example, in a randomised controlled trial giving a new drug to randomly selected individuals and then comparing outcomes with controls),[ 9 ] the case study approach lends itself well to capturing information on more explanatory ' how ', 'what' and ' why ' questions, such as ' how is the intervention being implemented and received on the ground?'. The case study approach can offer additional insights into what gaps exist in its delivery or why one implementation strategy might be chosen over another. This in turn can help develop or refine theory, as shown in our study of the teaching of patient safety in undergraduate curricula (Table (Table4 4 )[ 6 , 10 ]. Key questions to consider when selecting the most appropriate study design are whether it is desirable or indeed possible to undertake a formal experimental investigation in which individuals and/or organisations are allocated to an intervention or control arm? Or whether the wish is to obtain a more naturalistic understanding of an issue? The former is ideally studied using a controlled experimental design, whereas the latter is more appropriately studied using a case study design.

Case studies may be approached in different ways depending on the epistemological standpoint of the researcher, that is, whether they take a critical (questioning one's own and others' assumptions), interpretivist (trying to understand individual and shared social meanings) or positivist approach (orientating towards the criteria of natural sciences, such as focusing on generalisability considerations) (Table (Table6). 6 ). Whilst such a schema can be conceptually helpful, it may be appropriate to draw on more than one approach in any case study, particularly in the context of conducting health services research. Doolin has, for example, noted that in the context of undertaking interpretative case studies, researchers can usefully draw on a critical, reflective perspective which seeks to take into account the wider social and political environment that has shaped the case[ 11 ].

Example of epistemological approaches that may be used in case study research

| Approach | Characteristics | Criticisms | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involves questioning one's own assumptions taking into account the wider political and social environment. | It can possibly neglect other factors by focussing only on power relationships and may give the researcher a position that is too privileged. | Howcroft and Trauth[ ] Blakie[ ] Doolin[ , ] | |

| Interprets the limiting conditions in relation to power and control that are thought to influence behaviour. | Bloomfield and Best[ ] | ||

| Involves understanding meanings/contexts and processes as perceived from different perspectives, trying to understand individual and shared social meanings. Focus is on theory building. | Often difficult to explain unintended consequences and for neglecting surrounding historical contexts | Stake[ ] Doolin[ ] | |

| Involves establishing which variables one wishes to study in advance and seeing whether they fit in with the findings. Focus is often on testing and refining theory on the basis of case study findings. | It does not take into account the role of the researcher in influencing findings. | Yin[ , , ] Shanks and Parr[ ] |

How are case studies conducted?

Here, we focus on the main stages of research activity when planning and undertaking a case study; the crucial stages are: defining the case; selecting the case(s); collecting and analysing the data; interpreting data; and reporting the findings.

Defining the case

Carefully formulated research question(s), informed by the existing literature and a prior appreciation of the theoretical issues and setting(s), are all important in appropriately and succinctly defining the case[ 8 , 12 ]. Crucially, each case should have a pre-defined boundary which clarifies the nature and time period covered by the case study (i.e. its scope, beginning and end), the relevant social group, organisation or geographical area of interest to the investigator, the types of evidence to be collected, and the priorities for data collection and analysis (see Table Table7 7 )[ 1 ]. A theory driven approach to defining the case may help generate knowledge that is potentially transferable to a range of clinical contexts and behaviours; using theory is also likely to result in a more informed appreciation of, for example, how and why interventions have succeeded or failed[ 13 ].

Example of a checklist for rating a case study proposal[ 8 ]

| Clarity: Does the proposal read well? | |

| Integrity: Do its pieces fit together? | |

| Attractiveness: Does it pique the reader's interest? | |

| The case: Is the case adequately defined? | |

| The issues: Are major research questions identified? | |

| Data Resource: Are sufficient data sources identified? | |

| Case Selection: Is the selection plan reasonable? | |

| Data Gathering: Are data-gathering activities outlined? | |

| Validation: Is the need and opportunity for triangulation indicated? | |

| Access: Are arrangements for start-up anticipated? | |

| Confidentiality: Is there sensitivity to the protection of people? | |

| Cost: Are time and resource estimates reasonable? |

For example, in our evaluation of the introduction of electronic health records in English hospitals (Table (Table3), 3 ), we defined our cases as the NHS Trusts that were receiving the new technology[ 5 ]. Our focus was on how the technology was being implemented. However, if the primary research interest had been on the social and organisational dimensions of implementation, we might have defined our case differently as a grouping of healthcare professionals (e.g. doctors and/or nurses). The precise beginning and end of the case may however prove difficult to define. Pursuing this same example, when does the process of implementation and adoption of an electronic health record system really begin or end? Such judgements will inevitably be influenced by a range of factors, including the research question, theory of interest, the scope and richness of the gathered data and the resources available to the research team.

Selecting the case(s)

The decision on how to select the case(s) to study is a very important one that merits some reflection. In an intrinsic case study, the case is selected on its own merits[ 8 ]. The case is selected not because it is representative of other cases, but because of its uniqueness, which is of genuine interest to the researchers. This was, for example, the case in our study of the recruitment of minority ethnic participants into asthma research (Table (Table1) 1 ) as our earlier work had demonstrated the marginalisation of minority ethnic people with asthma, despite evidence of disproportionate asthma morbidity[ 14 , 15 ]. In another example of an intrinsic case study, Hellstrom et al.[ 16 ] studied an elderly married couple living with dementia to explore how dementia had impacted on their understanding of home, their everyday life and their relationships.

For an instrumental case study, selecting a "typical" case can work well[ 8 ]. In contrast to the intrinsic case study, the particular case which is chosen is of less importance than selecting a case that allows the researcher to investigate an issue or phenomenon. For example, in order to gain an understanding of doctors' responses to health policy initiatives, Som undertook an instrumental case study interviewing clinicians who had a range of responsibilities for clinical governance in one NHS acute hospital trust[ 17 ]. Sampling a "deviant" or "atypical" case may however prove even more informative, potentially enabling the researcher to identify causal processes, generate hypotheses and develop theory.

In collective or multiple case studies, a number of cases are carefully selected. This offers the advantage of allowing comparisons to be made across several cases and/or replication. Choosing a "typical" case may enable the findings to be generalised to theory (i.e. analytical generalisation) or to test theory by replicating the findings in a second or even a third case (i.e. replication logic)[ 1 ]. Yin suggests two or three literal replications (i.e. predicting similar results) if the theory is straightforward and five or more if the theory is more subtle. However, critics might argue that selecting 'cases' in this way is insufficiently reflexive and ill-suited to the complexities of contemporary healthcare organisations.

The selected case study site(s) should allow the research team access to the group of individuals, the organisation, the processes or whatever else constitutes the chosen unit of analysis for the study. Access is therefore a central consideration; the researcher needs to come to know the case study site(s) well and to work cooperatively with them. Selected cases need to be not only interesting but also hospitable to the inquiry [ 8 ] if they are to be informative and answer the research question(s). Case study sites may also be pre-selected for the researcher, with decisions being influenced by key stakeholders. For example, our selection of case study sites in the evaluation of the implementation and adoption of electronic health record systems (see Table Table3) 3 ) was heavily influenced by NHS Connecting for Health, the government agency that was responsible for overseeing the National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT)[ 5 ]. This prominent stakeholder had already selected the NHS sites (through a competitive bidding process) to be early adopters of the electronic health record systems and had negotiated contracts that detailed the deployment timelines.

It is also important to consider in advance the likely burden and risks associated with participation for those who (or the site(s) which) comprise the case study. Of particular importance is the obligation for the researcher to think through the ethical implications of the study (e.g. the risk of inadvertently breaching anonymity or confidentiality) and to ensure that potential participants/participating sites are provided with sufficient information to make an informed choice about joining the study. The outcome of providing this information might be that the emotive burden associated with participation, or the organisational disruption associated with supporting the fieldwork, is considered so high that the individuals or sites decide against participation.

In our example of evaluating implementations of electronic health record systems, given the restricted number of early adopter sites available to us, we sought purposively to select a diverse range of implementation cases among those that were available[ 5 ]. We chose a mixture of teaching, non-teaching and Foundation Trust hospitals, and examples of each of the three electronic health record systems procured centrally by the NPfIT. At one recruited site, it quickly became apparent that access was problematic because of competing demands on that organisation. Recognising the importance of full access and co-operative working for generating rich data, the research team decided not to pursue work at that site and instead to focus on other recruited sites.

Collecting the data

In order to develop a thorough understanding of the case, the case study approach usually involves the collection of multiple sources of evidence, using a range of quantitative (e.g. questionnaires, audits and analysis of routinely collected healthcare data) and more commonly qualitative techniques (e.g. interviews, focus groups and observations). The use of multiple sources of data (data triangulation) has been advocated as a way of increasing the internal validity of a study (i.e. the extent to which the method is appropriate to answer the research question)[ 8 , 18 - 21 ]. An underlying assumption is that data collected in different ways should lead to similar conclusions, and approaching the same issue from different angles can help develop a holistic picture of the phenomenon (Table (Table2 2 )[ 4 ].

Brazier and colleagues used a mixed-methods case study approach to investigate the impact of a cancer care programme[ 22 ]. Here, quantitative measures were collected with questionnaires before, and five months after, the start of the intervention which did not yield any statistically significant results. Qualitative interviews with patients however helped provide an insight into potentially beneficial process-related aspects of the programme, such as greater, perceived patient involvement in care. The authors reported how this case study approach provided a number of contextual factors likely to influence the effectiveness of the intervention and which were not likely to have been obtained from quantitative methods alone.

In collective or multiple case studies, data collection needs to be flexible enough to allow a detailed description of each individual case to be developed (e.g. the nature of different cancer care programmes), before considering the emerging similarities and differences in cross-case comparisons (e.g. to explore why one programme is more effective than another). It is important that data sources from different cases are, where possible, broadly comparable for this purpose even though they may vary in nature and depth.

Analysing, interpreting and reporting case studies

Making sense and offering a coherent interpretation of the typically disparate sources of data (whether qualitative alone or together with quantitative) is far from straightforward. Repeated reviewing and sorting of the voluminous and detail-rich data are integral to the process of analysis. In collective case studies, it is helpful to analyse data relating to the individual component cases first, before making comparisons across cases. Attention needs to be paid to variations within each case and, where relevant, the relationship between different causes, effects and outcomes[ 23 ]. Data will need to be organised and coded to allow the key issues, both derived from the literature and emerging from the dataset, to be easily retrieved at a later stage. An initial coding frame can help capture these issues and can be applied systematically to the whole dataset with the aid of a qualitative data analysis software package.

The Framework approach is a practical approach, comprising of five stages (familiarisation; identifying a thematic framework; indexing; charting; mapping and interpretation) , to managing and analysing large datasets particularly if time is limited, as was the case in our study of recruitment of South Asians into asthma research (Table (Table1 1 )[ 3 , 24 ]. Theoretical frameworks may also play an important role in integrating different sources of data and examining emerging themes. For example, we drew on a socio-technical framework to help explain the connections between different elements - technology; people; and the organisational settings within which they worked - in our study of the introduction of electronic health record systems (Table (Table3 3 )[ 5 ]. Our study of patient safety in undergraduate curricula drew on an evaluation-based approach to design and analysis, which emphasised the importance of the academic, organisational and practice contexts through which students learn (Table (Table4 4 )[ 6 ].