Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

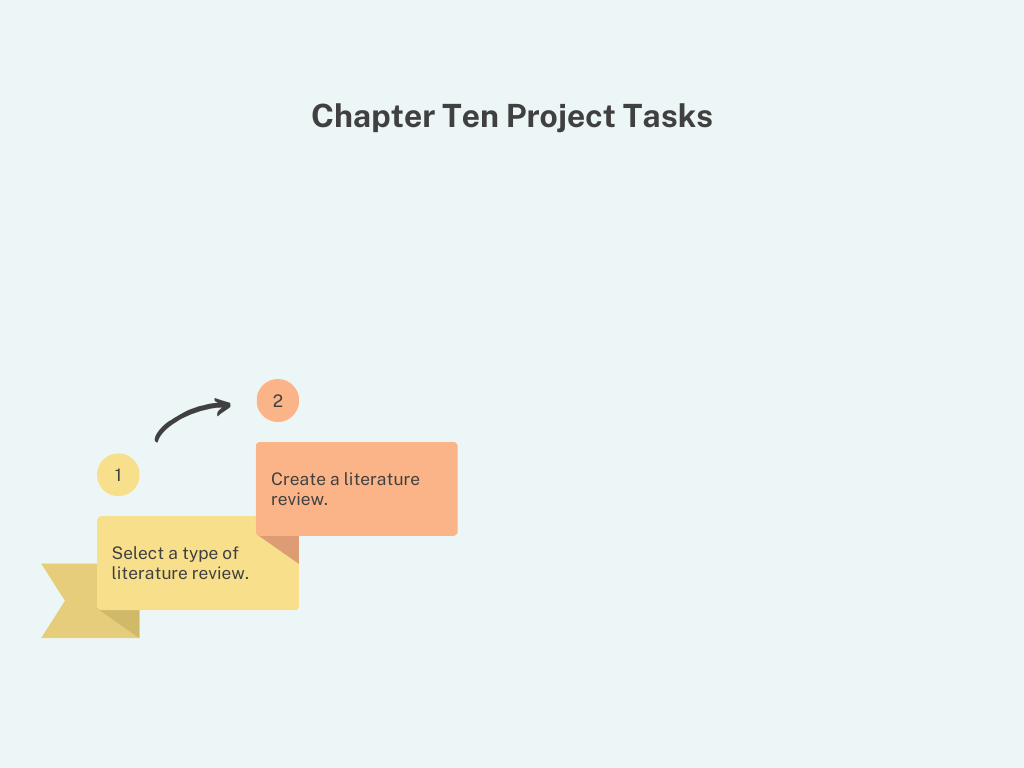

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

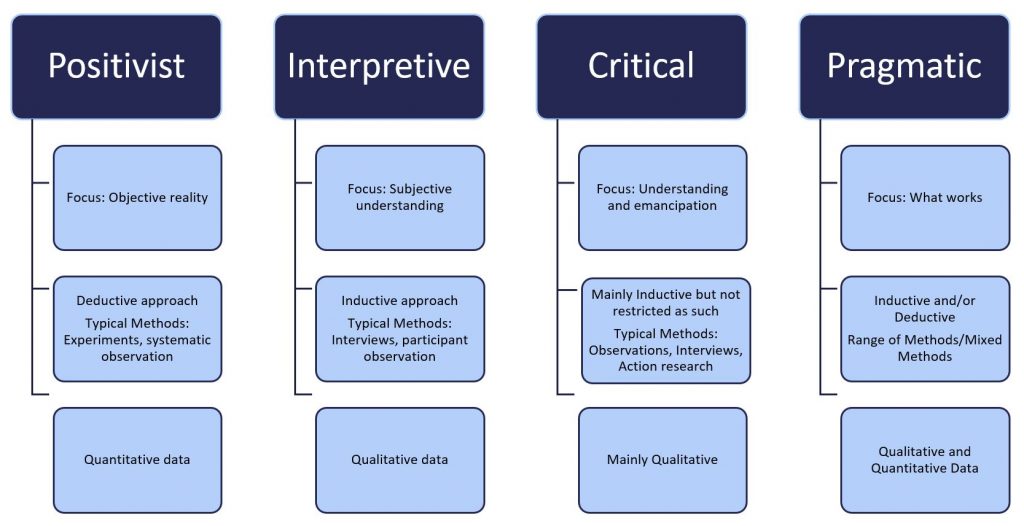

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

When you need an introduction for a literature review

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

What to include in a literature review introduction

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

Examples of literature review introductions

Example 1: an effective introduction for an academic literature review paper.

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.

Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chapters

Numerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers.

Master’s thesis literature review introduction

Phd thesis literature review chapter introduction, phd thesis literature review introduction.

The last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records.

Steps to write your own literature review introduction

Master academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, the best answers to "what are your plans for the future", 10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles, minor revisions: sample peer review comments and examples, sample emails to your thesis supervisor, co-authorship guidelines to successfully co-author a scientific paper, how to select a journal for publication as a phd student.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 2: What is a Literature Review?

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Recognize how information is created and how it evolves over time.

- Identify how the information cycle impacts the reliability of the information.

- Select information sources appropriate to information need.

2.1 Overview of information

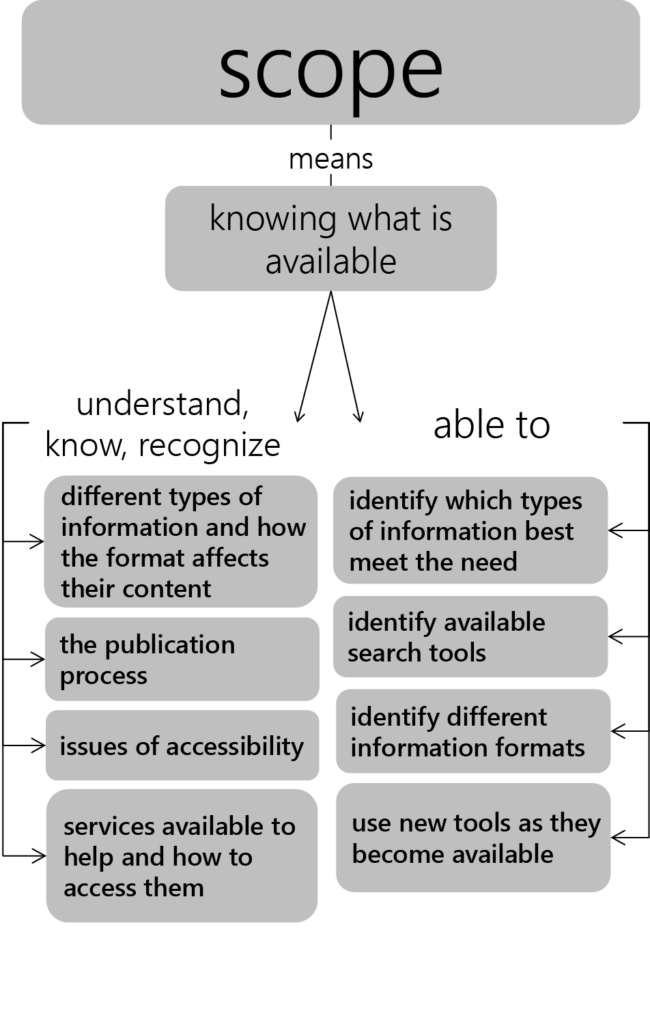

Because a literature review is a summary and analysis of the relevant publications on a topic, we first have to understand what is meant by ‘the literature’. In this case, ‘the literature’ is a collection of all of the relevant written sources on a topic. It will include both theoretical and empirical works. Both types provide scope and depth to a literature review.

2.1.1 Disciplines of knowledge

When drawing boundaries around an idea, topic, or subject area, it helps to think about how and where the information for the field is produced. For this, you need to identify the disciplines of knowledge production in a subject area.

Information does not exist in the environment like some kind of raw material. It is produced by individuals working within a particular field of knowledge who use specific methods for generating new information. Disciplines are knowledge-producing and -disseminating systems which consume, produce and disseminate knowledge. Looking through a course catalog of a post-secondary educational institution gives clues to the structure of a discipline structure. Fields such as political science, biology, history and mathematics are unique disciplines, as are education and nursing, with their own logic for how and where new knowledge is introduced and made accessible.

You will need to become comfortable with identifying the disciplines that might contribute information to any search strategy. When you do this, you will also learn how to decode the way how people talk about a topic within a discipline. This will be useful to you when you begin a review of the literature in your area of study.

For example, think about the disciplines that might contribute information to a the topic such as the role of sports in society. Try to anticipate the type of perspective each discipline might have on the topic. Consider the following types of questions as you examine what different disciplines might contribute:

- What is important about the topic to the people in that discipline?

- What is most likely to be the focus of their study about the topic?

- What perspective would they be likely to have on the topic?

In this example, we identify two disciplines that have something to say about the role of sports in society: allied health and education. What would each of these disciplines raise as key questions or issues related to that topic?

2.1.1.1 Nursing

- how sports affect individuals’ health and well-being

- assessing and treating sports injuries

- physical conditioning for athletes

2.1.1.2 Education

- how schools privilege or punish student athletes

- how young people are socialized into the ideal of team cooperation

- differences between boys’ and girls’ participation in organized sports

We see that a single topic can be approached from many different perspectives depending on how the disciplinary boundaries are drawn and how the topic is framed. This step of the research process requires you to make some decisions early on to focus the topic on a manageable and appropriate scope for the rest of the strategy. ( Hansen & Paul, 2015 ).

‘The literature’ consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation in a field of study. You will find, in ‘the literature,’ documents that explain the background of your topic so the reader knows where you found loose ends in the established research of the field and what led you to your own project. Although your own literature review will focus on primary, peer-reviewed resources, it will begin by first grounding yourself in background subject information generally found in secondary and tertiary sources such as books and encyclopedias. Once you have that essential overview, you delve into the seminal literature of the field. As a result, while your literature review may consist of research articles tightly focused on your topic with secondary and tertiary sources used more sparingly, all three types of information (primary, secondary, tertiary) are critical to your research.

2.1.2 Definitions

- Theoretical – discusses a theory, conceptual model or framework for understanding a problem.

- Empirical – applies theory to a behavior or event and reports derived data to findings.

- Seminal – “A classic work of research literature that is more than 5 years old and is marked by its uniqueness and contribution to professional knowledge.” ( Houser, 4th ed., 2018, p. 112 ).

- Practical – “…accounts of how things are done” ( Wallace & Wray, 3rd ed., 2016, p. 20 ). Action research, in Education, refers to a wide variety of methods used to develop practical solutions. ( Great Schools Partnership, 2017 ).

- Policy – generally produced by policy-makers, such as government agencies.

- Primary – published results of original research studies .

- Secondary – interpret, discuss, summarize original sources

- Tertiary – synthesize or distill primary and secondary sources. Examples include: encyclopedias, directories, dictionaries, handbooks, guides, classification, chronology, and other fact books.

- Grey literature – research and information released by non-commercial publishers, such as government agencies, policy organizations, and think-tanks.

‘The literature’ is published in books, journal articles, conference proceedings, theses and dissertations. It can also be found in newspapers, encyclopedias, textbooks, as well as websites and reports written by government agencies and professional organizations. While these formats may contain what we define as ‘the literature’, not all of it will be appropriate for inclusion in your own literature review.

These sources are found through different tools that we will discuss later in this section. Although a discovery tool, such as a database or catalog, may link you to the ‘the literature’ not every tool is appropriate to every literature review. No single source will have all of the information resources you should consult. A comprehensive literature review should include searches in the following:

- Multiple subject and article databases

- Library and other book catalogs

- Grey literature sources

2.2 Information Cycle

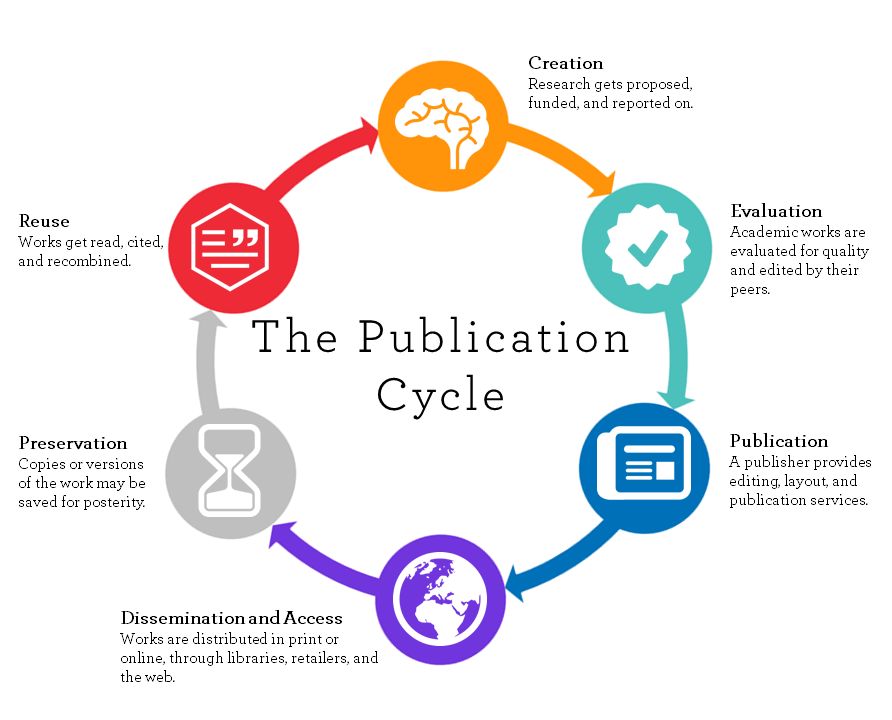

To get a better idea of how the literature in a discipline develops, it’s useful to see how the information publication lifecycle works. These distinct stages show how information is created, reviewed, and distributed over time.

The following chart can be used to guide you in searching literature existing at various stages of the scholarly communication process (freely accessible sources are linked, subscription or subscribed sources are listed but not linked):

| Steps in the Scholarly Communication Process | Publication Cycle | Access Points |

| Research and develop idea | Unpublished documents such as lab notebooks, personal correspondence, graphs, charts, grant proposals, and other ‘grey literature’ | Limited access

(Health Services and Sciences Research Resources) (Database of NIH funded research projects)

|

| Present preliminary findings | Preliminary reports: letters to the editor or journals, brief (short) communication submitted to a primary journal | (limiting search results to Letter under Limits) Web of Science (Science Citation Index) |

| Report research | Conference literature: preprints, conference proceedings | PapersFirst ProceedingsFirst Conference web sites

|

| Research reports: master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, interim or technical reports |

(limiting search results to Technical Report under Limits)

Professional association web sites

| |

| Publish research | Research paper (scholarly journal articles): research papers published in peer-reviewed/refereed journals | CINAHL PsycINFO Web of Science

|

| Popularize research findings | Newspapers, popular magazines, TV news reports, trade publications, web sites | (limiting search results to News and Newspaper Article under Limits) Media outlets Internet search engines |

| Compact and repackage information | Reviews, systematic reviews, guidelines, textbooks, handbooks, yearbooks, encyclopedias | Library Catalogs

|

2.3 Information Types

To continue our discussion of information sources, there are two ways published information in the field can be categorized:

- Articles by the type of periodical in which an article it is published, for example, magazine, trade, or scholarly publications .

- Where the material is located in the information cycle, as in primary, secondary, or tertiary information sources .

2.3.1 Popular, Trade, or Scholarly publications

2.3.1.1 types of periodicals.

Journals, trade publications, and magazines are all periodicals, and articles from these publications they can all look similar article by article when you are searching in the databases. It is good to review the differences and think about when to use information from each type of periodical.

2.3.1.2 Magazines

A magazine is a collection of articles and images about diverse topics of popular interest and current events.

Features of magazines:

- articles are usually written by journalists

- articles are written for the average adult

- articles tend to be short

- articles rarely provides a list of reference sources at the end of the article

- lots of color images and advertisements

- the decision about what goes into the magazine is made by an editor or publisher

- magazines can have broad appeal, like Time and Newsweek , or a narrow focus, like Sports Illustrated and Mother Earth News .

Popular magazines like Psychology Today , Sports Illustrated , and Rolling Stone can be good sources for articles on recent events or pop-culture topics, while Harpers , Scientific American , and The New Republic will offer more in-depth articles on a wider range of subjects. These articles are geared towards readers who, although not experts, are knowledgeable about the issues presented.

2.3.1.3 Trade Publications

Trade publications or trade journals are periodicals directed to members of a specific profession. They often have information about industry trends and practical information for people working in the field.

Features of trade publications:

- Authors are specialists in their fields

- Focused on members of a specific industry or profession

- No peer review process

- Include photographs, illustrations, charts, and graphs, often in color

- Technical vocabulary

Trade publications are geared towards professionals in a discipline. They report news and trends in a field, but not original research. They may provide product or service reviews, job listings, and advertisements.

2.3.1.4 Scholarly, Academic, and Scientific Publications

Scholarly, academic, and scientific publications are a collections of articles written by scholars in an academic or professional field. Most journals are peer-reviewed or refereed, which means a panel of scholars reviews articles to decide if they should be accepted into a specific publication. Journal articles are the main source of information for researchers and for literature reviews.

Features of journals:

- written by scholars and subject experts

- author’ credentials and institution will be identified

- written for other scholars

- dedicated to a specific discipline that it covers in depth

- often report on original or innovative research

- long articles, often 5-15 pages or more

- articles almost always include a list of sources at the end (Works Cited, References, Sources, or Bibliography) that point back to where the information was derived

- no or very few advertisements

- published by organizations or associations to advance their specialized body of knowledge

Scholarly journals provider articles of interest to experts or researchers in a discipline. An editorial board of respected scholars (peers) reviews all articles submitted to a journal. They decide if the article provides a noteworthy contribution to the field and should be published. There are typically few little or no advertisements. Articles published in scholarly journals will include a list of references.

2.3.1.5 A word about open access journals

Increasingly, scholars are publishing findings and original research in open access journals . Open access journals are scholarly and peer-reviewed and open access publishers provide unrestricted access and unrestricted use. Open access is a means of disseminating scholarly research that breaks from the traditional subscription model of academic publishing. It is free of charge to readers and because it is online, it is available at anytime, anywhere in the world, to anyone with access to the internet. The Directory of Open Access Journals ( DOAJ ) indexes and provides access to high-quality, peer-reviewed scholarly articles.

In summary, newspapers and other popular press publications are useful for getting general topic ideas. Trade publications are useful for practical application in a profession and may also be a good source of keywords for future searching. Scholarly journals are the conversation of the scholars who are doing research in a specific discipline and publishing their research findings.

2.3.1.6 Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

Primary sources of information are those types of information that come first. Some examples of primary sources are:

- original research, like data from an experiment with plankton.

- diaries, journals, photographs

- data from the census bureau or a survey you have done

- original documents, like the constitution or a birth certificate

- newspapers are primary sources when they report current events or current opinion

- speeches, interviews, email, letters

- religious books

- personal memoirs and autobiographies

- pottery or weavings

There are different types of primary sources for different disciplines. In the discipline of history, for example, a diary or transcript of a speech is a primary source. In education and nursing, primary sources will generally be original research, including data sets.

Secondary sources are written about primary sources to interpret or analyze them. They are a step or more removed from the primary event or item. Some examples of secondary sources are:

- commentaries on speeches

- critiques of plays, journalism, or books

- a journal article that talks about a primary source such as an interpretation of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, or the flower symbolism of Monet’s water garden paintings

- textbooks (can also be considered tertiary)

- biographies

- encyclopedias

Tertiary sources are further removed from the original material and are a distillation and collection of primary and secondary sources. Some examples are:

- bibliography of critical works about an author

- textbooks (also considered secondary)

A comparison of information sources across disciplines:

| SUBJECT | PRIMARY | SECONDARY | TERTIARY |

| Education | Journal article reporting on quantitative study of after school programs | Article in Teacher Magazine about after school programs | Handbook of afterschool programming ERIC database |

| Nursing | Journal article reporting on a Cclinical trial of a treatment or device | Systematic review of treatment or device, such as those found in the | Encyclopedia of Nursing Research |

| Psychology | Patient notes taken by clinical psychologist | Magazine article about the patient’s psychological condition | Textbook on clinical psychology |

2.4 Information Sources

In this section, we discuss how to find not only information, but the sources of information in your discipline or topic area. As we see in the graphic and chart above, the information you need for your literature review will be located in multiple places. How and where research and publication occurs drives how and where the information is located, which in turn determines how you will discover and retrieve it. When we talk about information sources for a literature review in education or nursing, we generally mean these five areas: the internet, reference material and other books, empirical or evidence-based articles in scholarly, peer-reviewed journals, conference proceedings and papers, dissertations and theses, and grey literature.

The World Wide Web can be an excellent place to satisfy some initial research needs.

- It is a good resource for background information and for finding keywords for searching in the library catalog and databases.

- It is a good tool for locating professional organizations and searching for information and the names of experts in a given discipline.

- Google Scholar is a useful discovery tool for citations, especially if you are trying to get the lay of the land surrounding your topic or if you are having a problem with keywords in the databases. You can find some information to refine your search terms. It is NOT acceptable to depend on Google Scholar for finding articles because of the spotty coverage and lack of adequate search features.

2.4.2 Books and Reference Sources

Reference materials and books are available in both print and electronic formats. They provide gateway knowledge to a subject area and are useful at the beginning of the research process to:

- Get an overview of the topic, learn the scope, key definitions, significant figures who are involved, and important timelines

- Discover the foundations of a topic

- Learn essential definitions, vocabulary terms, and keywords you can use in your literature searching strategy

2.4.3 Scholarly Articles in Journals

Another major category of information sources is scholarly information produced by subject experts working in academic institutions, research centers and scholarly organizations. Scholars and researchers generate information that advances our knowledge and understanding of the world. The research they do creates new opportunities for inventions, practical applications, and new approaches to solving problems or understanding issues.

Academics, researchers and students at universities make their contributions to scholarly knowledge available in many forms:

- masters’ theses

- doctoral dissertations

- conference papers

- journal articles and books

- individual scholars’ web pages

- web pages developed by the researcher’s’ home institution (Hansen & Paul, 2015).

Scholars and researchers introduce their discoveries to the world in a formal system of information dissemination that has developed over centuries. Because scholarly research undergoes a process of “peer review” before being published (meaning that other experts review the work and pass judgment about whether it is worthy of publication), the information you find from scholarly sources meets preset standards for accuracy, credibility and validity in that field.

Likewise, scholarly journal articles are generally considered to be among the most reliable sources of information because they have gone through a peer-review process.

2.4.5 Conference Papers & Proceedings

Conferences are a major source of emerging research where researchers present papers on their current research and obtain feedback from the audience. The papers presented in the conference are then usually published in a volume called a conference proceeding. Conference proceedings highlight current discussion in a discipline and can lead you to scholars who are interested in specific research areas.

A word about conference papers: several factors contribute to making these documents difficult to find. It may be months before a paper is published as a journal article, or it may never be published. Publishers and professional associations are inconsistent in how they publish proceedings. For example, the papers from an annual conference may be published as individual, stand-alone titles, which may be indexed in a library catalog, or the conference proceedings may be treated more like a periodical or serial and, therefore, indexed in a journal database.

It is not unusual that papers delivered at professional conferences are not published in print or electronic form, although an abstract may be available. In these cases, the full paper may only be available from the author or authors.

The most important thing to remember is that if you have any difficulty finding a conference proceeding or paper, ask a librarian for assistance.

2.4.6 Dissertations and Theses

Dissertations and theses can be rich sources of information and have extensive reference lists to scan for resources. They are considered gray literature, so are not “peer reviewed”. The accuracy and validity of the paper itself may depend on the school that awarded the doctoral or master’s degree to the author.

2.5 Conclusion

In thinking about ‘the literature’ of your discipline, you are beginning the first step in writing your own literature review. By understanding what the literature in your field is, as well as how and when it is generated, you begin to know what is available and where to look for it.

We briefly discussed seven types of (sometimes overlapping) information:

- information found on the web

- information found in reference books and monographs

- information found in scholarly journals

- information found in conference proceedings and papers

- information found in dissertations and theses

- information found in magazines and trade journals

- information that is primary, secondary, or tertiary.

By conceptualizing or scoping how and where the literature of your discipline or topic area is generated, you have started on your way to writing your own literature review.

Finally, remember:

“All information sources are not created equal. Sources can vary greatly in terms of how carefully they are researched, written, edited, and reviewed for accuracy. Common sense will help you identify obviously questionable sources, such as tabloids that feature tales of alien abductions, or personal websites with glaring typos. Sometimes, however, a source’s reliability—or lack of it—is not so obvious…You will consider criteria such as the type of source, its intended purpose and audience, the author’s (or authors’) qualifications, the publication’s reputation, any indications of bias or hidden agendas, how current the source is, and the overall quality of the writing, thinking, and design.” ( Writing for Success, 2015, p. 448 ).

We will cover how to evaluate sources in more detail in Chapter 5.

For each of these information needs, indicate what resources would be the best fit to answer your question. There may be more than one source so don’t feel like you have to limit yourself to only one. See Answer Key for the correct response.

- You are to write a brief paper on a theory that you only vaguely understand. You need some basic information. Where would you look?

- If you heard something on the radio about a recent research involving an herbal intervention for weight loss where could you find the actual study?

- You are going to be doing an internship in a group home for young men. You have heard that one issue that comes up for them is anger. Where would you look for practical interventions to help you manage this problem if it came up?

- You have the opportunity to work on a research project through a grant proposal. You need to justify the research question and show that there is an interest and a need for this research. What resources would you cite in your application?

- You have been assigned a project to find primary sources about classroom discipline used in early 20th-century schools. What primary sources could you use and where would you find them?

- You have an idea for a great thesis but you are afraid that it has been done before. Since you would like to do something original, where could you find out if someone else has done the project?

- There was a post on Facebook that welfare recipients in Arizona were recently tested for drug use with only three in 140,000 having positive results. Where can I find out if this number is accurate?

Test Yourself

Question 1 match the type of periodical to its content.

Trade publication Scholarly journal Magazine

- Contains articles about a variety of topics of popular interest; also contains advertising.

- Has information about industry trends and practical information for professionals in a field.

- Contains articles written by scholars in an academic field and reviewed by experts in that field.

Question 2: Given what you know about information types and sources, put the following information sources in order from the least accurate and reliable to the most accurate and reliable. (1 least accurate/4 most accurate)

- Books and encyclopedias

- News broadcasts and social media directly following an event.

- Analysis of an event in the news media or popular magazine weeks after an event.

- Articles written by scholars and published in a journal.

Question 3: What is information called that is either a diary, a speech, original research, data, artwork, or a religious book.

Question 4: to find the best information in the databases you need to use keywords that are used by the scholars. where do you find out what keywords to try.

- From websites

- In journal articles

- All of the above

Question 5: Which of the following is NOT true about scholarly journals?

- They contain the conversation of the scholars on a particular subject.

- They are of interest to the general public.

- The articles are followed by an extensive reference list.

- They contain reports of original research.

Image Attribution

Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students Copyright © by Linda Frederiksen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 16 July 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

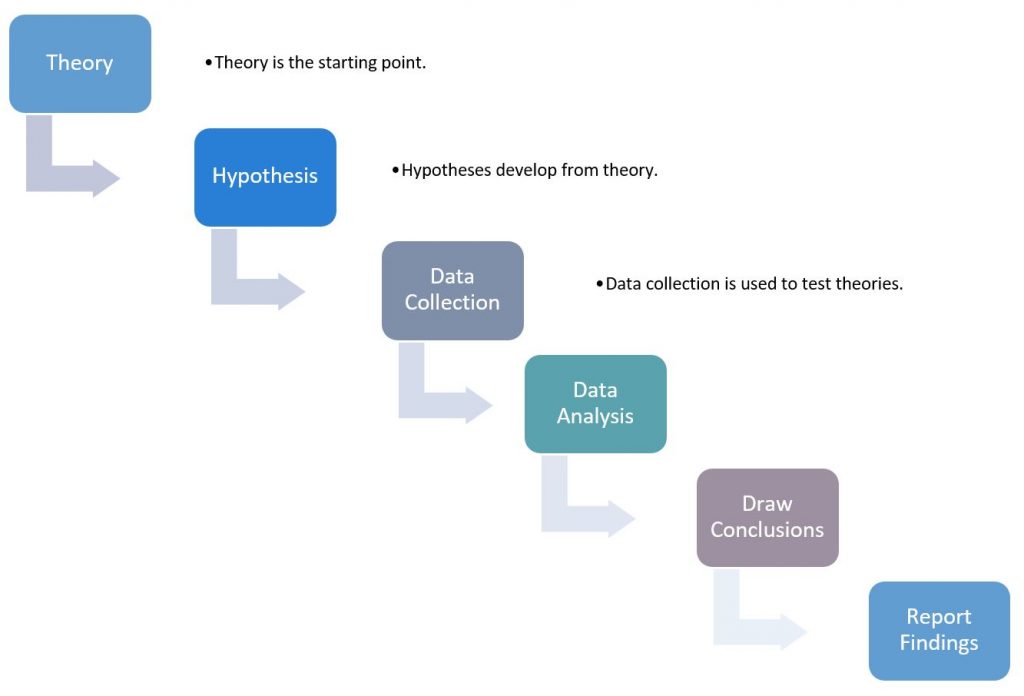

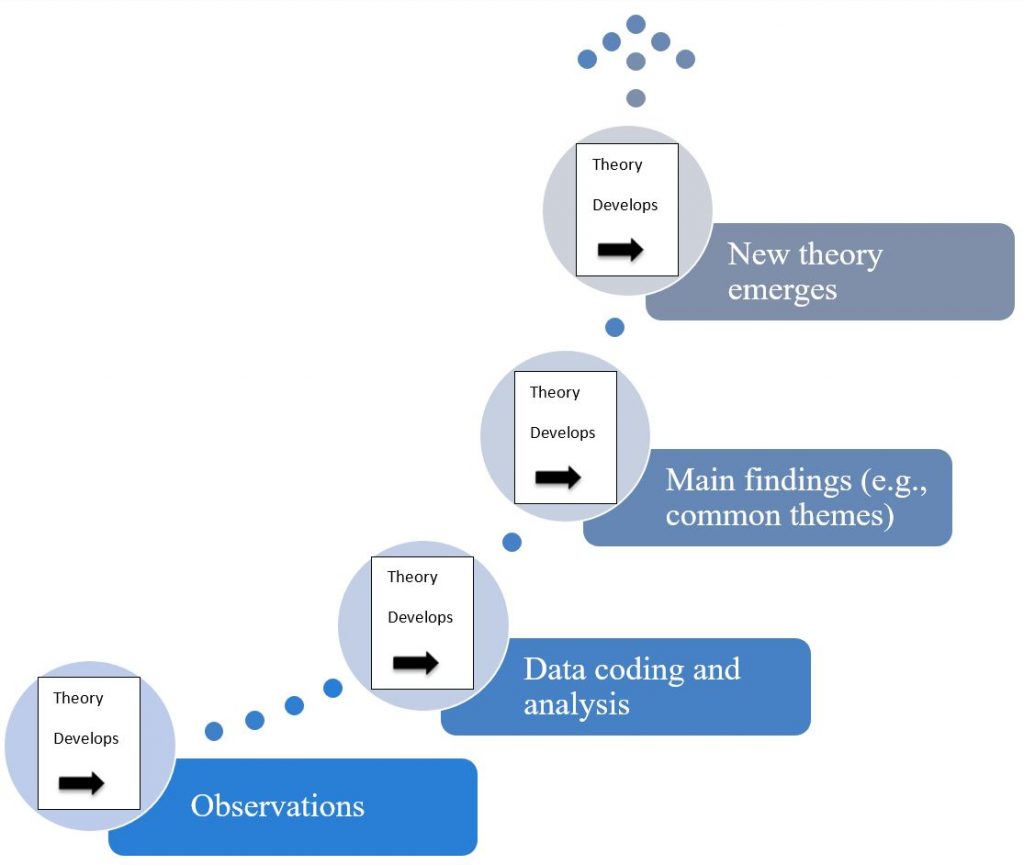

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.