Critically Thinking About the Slippery Slope "Fallacy"

Why is the slippery slope argument perceived as fallacious.

Posted September 13, 2019 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

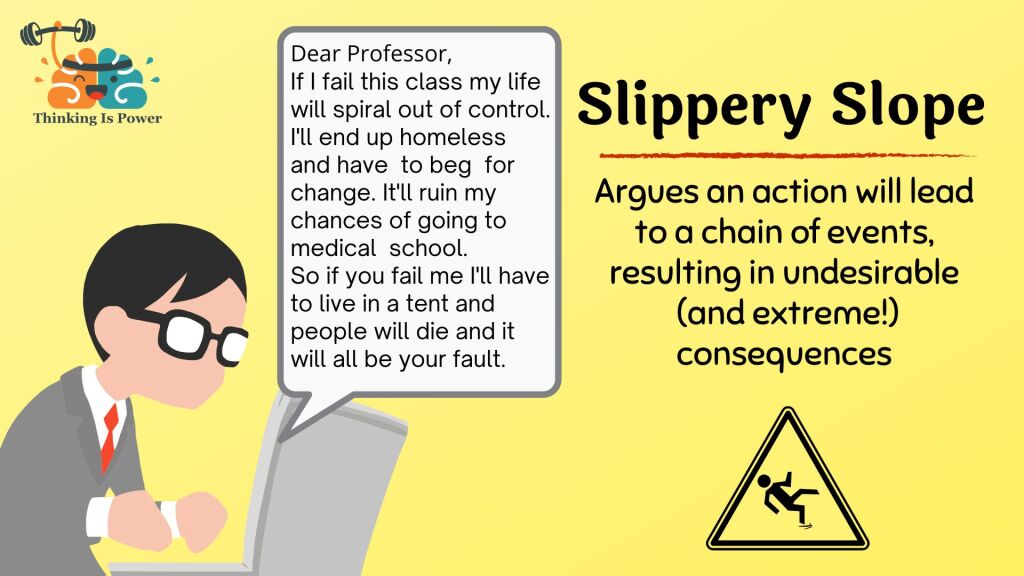

The Slippery Slope Argument is an argument that concludes that if an action is taken, other negative consequences will follow. For example, “If event X were to occur, then event Y would (eventually) follow; thus, we cannot allow event X to happen.”

In recent times, the Slippery Slope Argument (SSA) has been identified as a commonly encountered form of fallacious reasoning . Though the SSA can be used as a method of persuasion , that doesn't necessarily mean it's fallacious. In fact, SSAs are often solid forms of reasoning. Much of it comes down to the context of the argument. For example, if the propositions that make up the SSA are emotionally loaded (e.g. fear -evoking), then it’s more likely to be fallacious. If it’s unbiased, void of emotion , and makes efforts to assess plausibility, then there’s a good chance that it’s a reasonable conjecture.

So, why is the SSA perceived as fallacious?

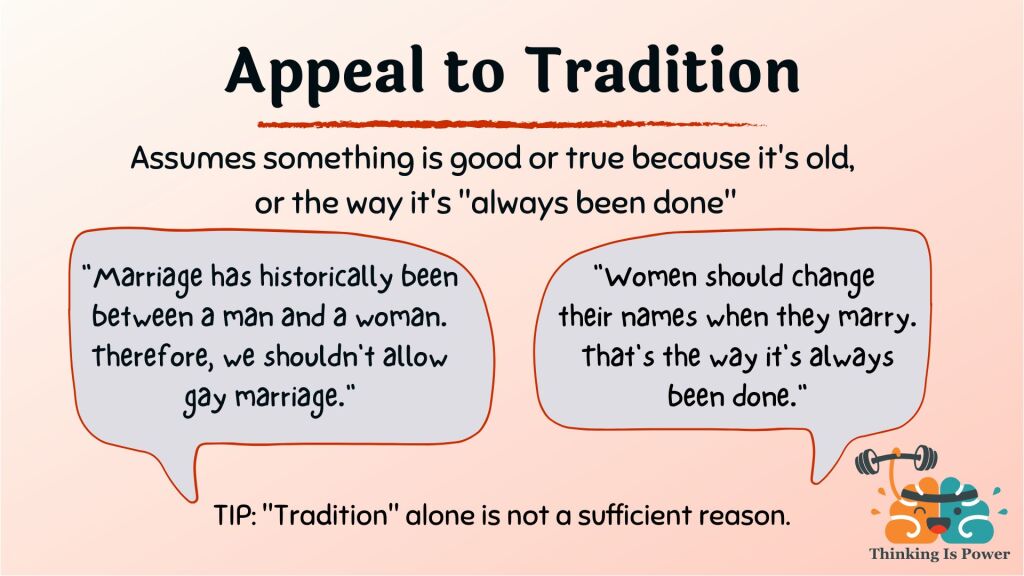

The SSA is perceived as fallacious primarily for reasons of relevance and certainty. With respect to relevance, what can make the SSA fallacious is that it may be used to avoid responding to propositions pertinent to the "here and now" of the argument at hand. It adds a component that isn’t necessarily relevant to the initial argument. For example, back in 2015, Ireland held a referendum regarding gay marriage , where citizens voted to legalise civil marriages between individuals of the same sex . One of the common arguments against the "yes vote" for same-sex marriage was that "if Ireland allowed gay marriage, then the next thing would be to allow same-sex couples to adopt." Regardless of how one felt about the "then" proposition, it was actually irrelevant to the propositions of the argument at hand. Whether or not adoption was legalised "down the road" had no bearing on whether or not two people of the same sex should be able to marry.

It is also worth noting that relevance, in this context, is also impacted upon, to a certain extent, by the acceptability or even desirability of the possible outcome. In the example above, it’s implied that the possibility of adoption by same-sex couples is a bad thing, which of course, not everyone believes. In fact, Ireland legalised adoption by same-sex couples soon after. As the SSA is a method of persuasion, it is by nature, biased — almost like a warning against an outcome the individual making the argument does not want to come to fruition. The interesting thing here is that the initial argument was fallacious in that it was presented in a negative light, much like a traditional SSA: “If event x were to occur, then event y would (eventually) follow; thus, we cannot allow event x to happen.” But, at the same time, the SSA was accurate in that "y" did eventually follow "x." Thus, it can be argued that the status of this argument as fallacious might just boil down to what individuals perceive as an acceptable outcome. However, the acceptability or desirability of the outcome shouldn’t really matter, given that what someone perceives doesn’t affect the likelihood of the conditions within the SSA from happening.

With respect to likelihood and certainty, the SSA is also often perceived as fallacious because it’s not possible for us to see into the future and guarantee that the subsequent event will occur. On the other hand, it’s also difficult to reject the claim for the same reason! But neither point necessarily makes this "if, then" conditional proposition unreasonable to suggest — it just requires assessment of plausibility. For example, as discussed previously, after critically thinking about patterns in human history, it may be possible to assess the plausibility of an event occurring in light of some previous event. If it’s plausible, then this SSA isn’t illogical.

To understand what's meant here by plausibility, it’s important to also understand that the foundation of the SSA is that it’s a conditional proposition, such as "if x, then y." Conditional propositions are commonplace in formal logic and are often logically sound. In some cases, arguments have multiple conditional claims which extend the "slope" — for example, "if x, then y" and "if y, then z." It might even go longer; for example, "if a, then b" and "if b, then c" and "if c, then d." However, in this context, the SSA is only fallacious if the propositions involved are false or implausible.

With that, the degree of plausibility, or even likelihood, of "x" leading to "z" or "a" leading to "d" cannot be assumed without careful consideration of the rest of the connecting conditional claims. If it’s plausible that "a" will eventually lead to "c," that implies that there is a good chance that both "a" will lead to "b" and that "b" will lead to "c." This is a reasonable way of considering conditional arguments, but it’s not entirely accurate because there is an underlying assumption that one will lead to the next and so on. The level of certainty requires thought.

When we consider such arguments in terms of likelihood, we see how we might be prone to overestimating the plausibility of the "event" occurring. For example, imagine that "a" leading to "b" is 90% likely, as are both "b" leading to "c" and "c" leading to "d." Many would be confident in the prospect that "a" would lead to "d" and may even give it a 90% chance of happening. But, this would be incorrect. What’s happening here is that the average across conditional propositions is being used. The reality is that the strength of the chain is weaker than the strength of each condition because it adds extra "if"s which affect the overall probability — thus, making "a" leading to "d" a 73% likelihood. Though 73% may be viewed as plausible, it’s still quite a bit less than 90%, so we need to be careful in our evaluation.

In conclusion, just because an SSA is used doesn’t mean that it’s wrong or fallacious. Sure, it’s commonly used as a method of persuasion; so, it requires evaluation. But, like other forms of argument, if it’s presented in a context that accounts for all available evidence, "for" and "against," so as to present the whole story, then it’s reasonable to consider its plausibility. On the other hand, SSAs can be wrong, unlikely, or emotionally loaded; but, so can other types of arguments. In reality, the only illogical course of action would be to dismiss an SSA without properly evaluating it first. As always, I’m very interested in hearing from any readers who may have any insight or suggestions, particularly perspectives from the field of argumentation!

Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D., is a lecturer at the Technological University of the Shannon in Athlone, Ireland.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Wireless Philosophy

Course: wireless philosophy > unit 1.

- Fallacies: Formal and Informal Fallacies

- Formal and Informal Fallacies

- Fallacies: Fallacy of Composition

- Fallacies: Fallacy of Division

- Division and Composition

- Fallacies: Introduction to Ad Hominem

- Fallacies: Ad Hominem

- Ad Hominem, Part 1

- Ad Hominem, Part 2

- Fallacies: Affirming the Consequent

- Fallacies: Denying the Antecedent

- Denying the Antecedent and Affirming the Consequent

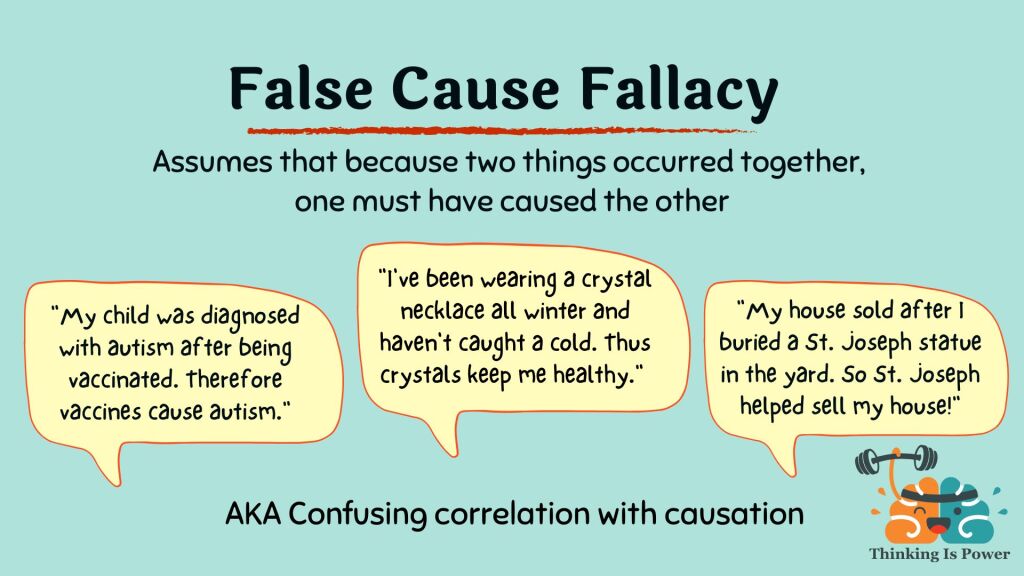

- Fallacies: Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc

- Fallacies: Appeal to the People

- Fallacies: Begging the Question

- Begging the Question

- Fallacies: Equivocation

- Fallacies: Straw Man Fallacy

Fallacies: Slippery Slope

- Fallacies: Red Herring

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Video transcript

Slippery Slope

In Lesson 12, we discussed conditionals, which are one of the ways in which a deductive argument may be framed. Conditionals use an "if-then" premise to lead to a conclusion (example: if you do not pay your electric bill, then your power will be turned off). When a conditional contains a logical fallacy, it is called a slippery slope.

In this type of fallacy, it is asserted that one event will or might happen, and then, inevitably, another, more serious or drastic, event will occur. The slippery slope does not explain how the first event leads to the other. Often, it leaves out a number of steps between the two events, without saying why they will simply be bypassed. The argument takes the following form:

1. Event A has/will/might occur.

2. Therefore, event B will inevitably occur.

The slippery slope argument makes an opponent's argument seem more extreme. It says that event A will eventually lead to an extreme, unwanted event B. The argument infers that the only way to avoid event B is to not do event A, or even anything at all. The gun lobby uses the slippery slope all the time to argue against any type of gun control. They say that any small measure, such as registration or waiting periods to purchase firearms, will lead to drastic control, or even confiscation of their weapons. Here is another example:

"We have to stop the tuition increase! Today, it's $5,000; tomorrow, they will be charging $40,000 a semester!"

Note that there are many possible steps between event A, the tuition increase, and event B, the charging of $40,000 a semester. An increase could occur every year for ten years or more before there was a jump from five to forty thousand dollars. In addition, tuition might never reach $40,000. This is a slippery slope because one tuition hike to $5,000 does not inevitably lead to a charge of $40,000.

Other examples are listed below. Keep in mind the possible intermediate steps between event A and event B in each, and the likelihood, or unlikelihood, that B will ever be a result of A.

■ Don't let him help you with that. The next thing you know, he will be running your life .

■ You can never give anyone a break. If you do, they will walk all over you.

■ This week, you want to stay out past your curfew. If I let you stay out, next week you'll be gone all night!

Continue reading here: Lesson 9 Persuasion Techniques

Was this article helpful?

Related Posts

- Making Decisions Under Stress

- Venn Diagram - Critical Thinking

- Effective Persuasion Techniques

- Avoid Making Assumptions - Critical Thinking

- Chicken and Egg Confusing Cause and Effect

- Pretest - Critical Thinking

Slippery Slope Fallacy (29 Examples + Definition)

You're here to understand the slippery slope fallacy, and you've come to the right place. This powerful concept can affect your decision-making, your debates, and even your understanding of the world.

A Slippery Slope Fallacy occurs when an argument suggests that a single action or event will lead to a series of other events without providing substantial evidence to support that claim.

We'll explain this subject and provide real-world examples. You'll learn about the psychology that makes these arguments so tempting to believe. By the end, you'll be more discerning and less likely to slide down that proverbial slope.

What is a Slippery Slope Fallacy?

Imagine you're on top of a hill covered in snow. You make a tiny snowball and give it a gentle push downhill. As it rolls, it picks up more snow and becomes a giant snowball, crashing into a house at the bottom.

The slippery slope fallacy is like saying that a small snowball you made must lead to a disaster without any evidence that it actually will. It assumes that one event sets off an unstoppable chain of events, ending in something really bad—or sometimes really good—but doesn't back it up with proof.

In the realm of arguments and debates, a slippery slope is a rhetorical device , which is a tool that debaters use to convince people. It often appears in discussions about law changes, ethics, and social norms.

It's also a logical fallacy , which is are logical error, usually in arguments, that people make, which leads to inconsistent reasoning.

Let's say someone argues that legalizing a minor form of gambling will inevitably lead to rampant addiction and crime. That's a slippery slope fallacy unless they prove that one action will lead to another.

The key takeaway is straightforward: not all initial actions lead to drastic outcomes. Just because an argument might sound compelling doesn't mean it's universally accurate.

When you hear someone use a slippery slope argument, ask for evidence.

Other Names for Slippery Slope Fallacy

- Domino Fallacy

- Thin Edge of the Wedge

- The Camel's Nose

Similar Logical Fallacies

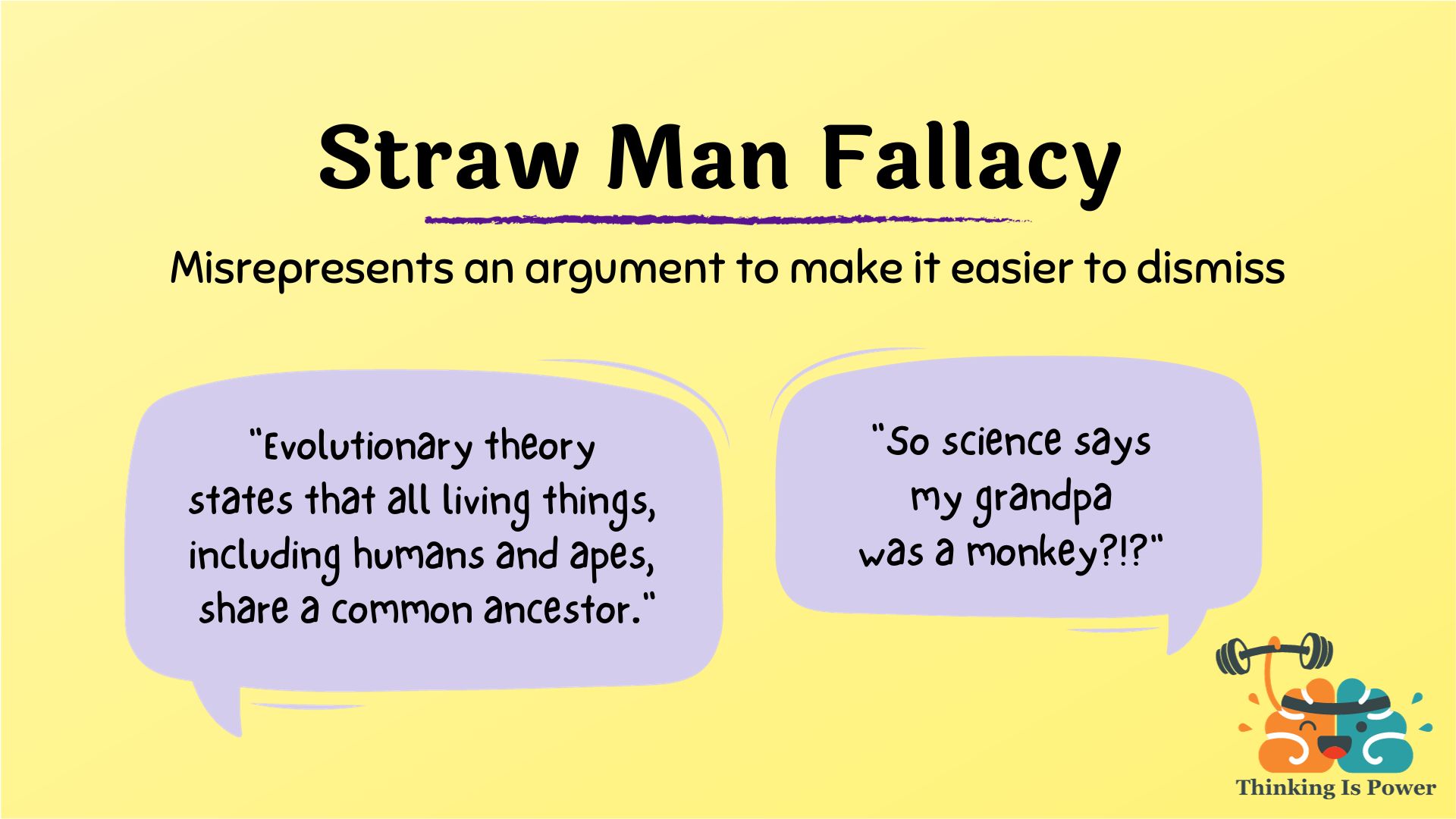

- Straw Man Fallacy - Misrepresenting someone's argument to make it easier to attack.

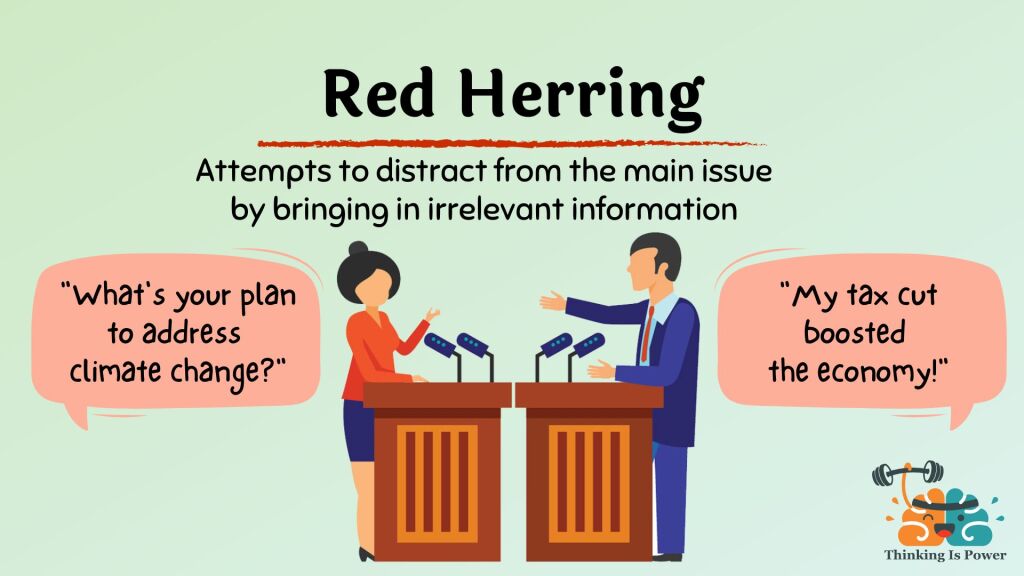

- Red Herring Fallacy - Introducing an irrelevant topic to divert attention from the original issue.

- False Analogy - Comparisons between two things that seem similar but are very different.

- Ad Hominem Attacks - Attacking the person instead of their argument.

- Circular Reasoning - Using the conclusion as the premise, arguing in a circle.

The term "slippery slope" has been around for quite some time, although it's hard to pinpoint its exact origin. It gained prominence in legal and ethical debates, especially those dealing with changes that could have far-reaching consequences.

Some sources trace its modern usage back to the early 20th century. It's an enduring term because it paints a vivid mental picture: once you start sliding down a slope, it's hard to stop. But remember, it's a fallacy if it lacks evidence to support its claims.

29 Examples of Slippery Slope Arguments

1) internet privacy.

"If we allow the government to access our data for national security, soon they'll be spying on our conversations and activities."

This argument assumes that allowing limited government access for a specific reason will automatically spiral into violating personal privacy. Without substantial evidence that this will occur, the argument leans on a slippery slope fallacy.

2) Soft Drinks and Health

"If you start drinking one soda a day, you'll become addicted and eventually suffer from obesity and diabetes."

Here, the argument goes from a single daily soda to extreme health consequences without providing steps or evidence in between. It's a classic example of the slippery slope fallacy.

3) Video Games and Violence

"Playing violent video games will desensitize you to violence, and you'll eventually become aggressive in real life."

This argument suggests that an initial action—playing a violent video game—will lead to extreme real-world consequences. Yet, it doesn't offer concrete evidence to connect these two points, making it a slippery slope fallacy.

4) Legalizing Marijuana

"If we legalize marijuana, then people will start pushing for the legalization of harder drugs like cocaine and heroin."

This argument assumes that legalizing one substance will automatically lead to the push for legalizing all substances, a slippery slope without concrete evidence.

5) Curfew Laws

"If we lift the teenage curfew, our town will become a haven for crime and lawlessness."

This leaps, lifting a single restriction to an extreme scenario of a crime-ridden town without any evidence to support such a claim.

6) Free Speech

"If we allow hate speech under the banner of free speech, it will inevitably lead to the spread of hate crimes and violence."

While the subject is sensitive, claiming that allowing one form of speech will result in violent actions is a slippery slope unless substantial evidence is provided.

7) Employee Benefits

"If we allow employees to work from home, productivity will plummet, and the company will go bankrupt."

This argument jumps from one policy change to a worst-case scenario without offering data or logic to link the two.

8) Plastic Surgery

"If you get one cosmetic procedure, you'll become addicted and end up ruining your natural beauty."

This assumes that one elective procedure will lead to an endless cycle of surgeries without any concrete evidence to prove it.

9) Gun Control

"If we enact even modest gun control measures, it's only a matter of time before all guns are banned."

This argument is a slippery slope, suggesting that a small regulation change will lead to a complete ban without evidence to back it up.

10) Relationships

"If you break up with me, you'll never find someone who treats you as well as I do."

This assumes that one decision—to break up—will lead to a lifetime of unhappiness, a slippery slope without basis.

11) Educational Policies

"If we remove one book from the school library due to inappropriate content, we'll end up censoring all literature that anyone finds offensive."

This argument jumps from a single action to a worst-case scenario without logical steps in between, making it a slippery slope fallacy.

12) Healthcare

"If we implement universal healthcare, the quality of care will decline, and we'll have to ration essential medical supplies."

This claim jumps from implementing a policy to extreme negative outcomes without offering evidence to connect these points.

13) Junk Food Taxes

"If the government starts taxing junk food, what's stopping them from taxing all the food we enjoy until we're only allowed to eat what they deem healthy?"

This argument assumes that one tax change will lead to a cascade of other taxes, affecting personal freedoms—another of conceptual slippery slope arguments without proper evidence.

14) Social Media Censorship

"If we allow social media platforms to remove hate speech, they'll start censoring any opinions they don't agree with."

This argument assumes that taking one moderation action will lead to broad censorship, a slippery slope without concrete evidence.

15) Veganism

"If you become a vegan, you'll eventually become so picky that you won't eat anything but raw vegetables."

Here, the argument makes a huge leap from choosing a vegan lifestyle to eating only raw vegetables without substantiated evidence.

16) Facial Recognition Technology

"If we allow facial recognition technology for security, it'll only be a matter of time before the government uses it to surveil us constantly."

This argument takes the introduction of a technology and jumps to an extreme invasion of privacy without showing the logical steps in between.

17) School Uniforms

"If we implement school uniforms today, tomorrow schools will dictate every aspect of student appearance and behavior."

This example claims that one dress code policy will lead to extreme authoritarian control without supporting evidence.

18) Environmental Policies

"If we ban plastic straws today, we'll be banning all forms of plastic and returning to the Stone Age tomorrow."

Here, the argument leaps from a simple environmental policy to an extreme rollback of modern conveniences without any evidence.

19) Early Relationships

"If you date him/her now, you're setting yourself up for a life of poor relationship choices."

This assumes that one relationship decision will dictate all future relationship decisions, a classic slippery slope fallacy.

20) Body Tattoos

"If you get a small tattoo, you'll end up with your entire body covered in tattoos and regret it later."

This example claims that a single, small action will lead to an extreme outcome without providing any evidence.

21) Digital Payments

"If we move to a cashless society, the government will control every aspect of our financial life."

This argument goes from a change in payment methods to extreme government control without showing logical progression or evidence.

22) School Testing

"If we remove standardized tests, the education system will crumble, and no student will be properly evaluated ever again."

This claim moves from a single policy change to the collapse of an entire system without substantiated evidence, making it a slippery slope fallacy.

23) Automation and Jobs

"If we allow more automation in factories, everyone will lose their jobs, and we'll have mass unemployment."

Here, the argument jumps from technological advancement to societal collapse without providing a concrete link between the two.

24) Online Education

"If we start offering more online classes, soon enough, traditional classrooms will become obsolete, and of course, the quality of education will decline."

This argument leaps from the introduction of online classes to the disappearance of traditional learning spaces and an overall decline in educational quality without solid evidence to support it.

25) Public Transportation

"If the city builds one more bike lane, cars will eventually be banned from the city center altogether."

Here, the argument suggests that adding a single bike lane will lead to a complete ban on cars in the city center without providing proof for such a drastic outcome.

26) Animal Rights

"If you adopt a shelter dog, you'll want to turn your home into an animal sanctuary and get overwhelmed."

This example takes a simple, kind act and turns it into an unsustainable, overwhelming lifestyle change without showing logical steps or evidence.

27) Streaming Services

"If you start subscribing to one streaming service, you'll waste all your money on subscriptions and neglect other responsibilities."

This assumes that subscribing to a single service will lead to financial recklessness and irresponsibility, another slippery slope without supporting facts.

28) Renewable Energy

"If we start relying on solar energy, it's a matter of time before other industries collapse and we face an economic downturn."

The argument jumps from adopting renewable energy to the downfall of other industries and an economic crisis without substantial evidence.

29) Exercise Routine

"If you skip your workout today, you'll lose all motivation and never achieve your fitness goals."

This example takes a single instance of skipping a workout and extends it to a lifetime of fitness failure without concrete proof.

The Psychological Mechanisms Behind It

The slippery slope fallacy often works because it taps into our emotional fears or desires.

Essentially, it plays on the human tendency to imagine worst-case (or best-case) scenarios. It's almost like a mental shortcut, helping us quickly assess a situation without going into the details of logical reasoning.

The appeal to emotion can make these arguments seem strong, even when they lack concrete evidence.

This logical fallacy also relies on another psychological concept called "cognitive ease." Your brain likes things that are easy to process.

When you hear a simple chain of events—"If A happens, then Z will surely happen"—it might feel intuitively right. But remember, feeling right doesn't make it logically right. Your brain may be taking the easy way out, but that can lead you down a slippery path of flawed reasoning.

The Impact of It

Slippery slope fallacies can have real-world consequences.

In politics, for example, they may be used to sway public opinion against a proposed law by predicting catastrophic outcomes.

In personal relationships, they can create unnecessary fear or conflict. Imagine being told that taking a break in a relationship will inevitably lead to a breakup; the emotional weight of such a statement can cause unnecessary strain.

Moreover, when decision-makers fall for this fallacy, they may forego beneficial opportunities. For instance, not adopting new technology for fear of potential, unproven drawbacks can result in missed advancements.

In these ways, the impact of the conceptual slippery slope fallacy is not just theoretical—it can lead to impractical or even damaging decisions.

How to Identify and Counter the Slippery Slope Fallacy

Spotting a slippery slope fallacy involves critical thinking . Listen for an argument that takes you from Point A to Point Z with little or no evidence. If you notice this, ask for the evidence that supports each leap.

Essentially, you're asking for the logical "steps" that take you down this so-called "slope." If these can't be provided, you've identified a causal slippery slope fallacy.

To counter it, request concrete evidence or data that links the initial action to the predicted outcome. Often, the person making the claim will be unable to provide it.

You can also turn the tables by asking how the proposed slippery slope differs from a scenario where no disastrous chain of events occurs. This forces the person to think critically about their argument, potentially revealing its weaknesses.

Remember, not all slippery slopes assume a negative outcome. It might be that such arguments are more convincing because they create positive emotions. The point of them is for the decision maker to shift their attention from the debate to their emotions. Please don't fall for it!

Related posts:

- Logical Fallacies (Common List + 21 Examples)

- Ad Hoc Fallacy (29 Examples + Other Names)

- Genetic Fallacy (28 Examples + Definition)

- Hasty Generalization Fallacy (31 Examples + Similar Names)

- Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy (29 Examples + Description)

Reference this article:

About The Author

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

7 Slippery Slope Fallacy Examples (And How to Counter Them)

There might be affiliate links on this page, which means we get a small commission of anything you buy. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Please do your own research before making any online purchase.

Say you’re debating a friend over the topic of marijuana legalization and they say this:

“If we legalize recreational marijuana, then marijuana will become normalized in public life. If marijuana is normalized, that will make it more likely that children and other impressionable people will partake. Before you know it, everyone will be doing drugs! Therefore, we should not legalize recreational marijuana.”

Now, your spidey senses might be tingling a bit. You can definitely tell something is wrong with the above argument, but you can’t quite put your finger on exactly what.

This argument is an example of a slippery slope fallacy . A slippery slope fallacy is a fallacious pattern of reasoning that claims that allowing some small event now will eventually culminate in a significant and (usually) negative final effect later. Slippery slope arguments are fallacious when the claimed links between the events are unlikely or exaggerated .

The above argument is a slippery slope fallacy because it posits a sequence of events that are weakly connected. In response, you could argue that it’s unlikely legalizing marijuana will make children more likely to use it. After all, there are lots of recreational substances, such as alcohol, that are legal and controlled to stay out of the hands of children and other vulnerable people.

You could also argue that legalizing some substance won’t necessarily make it more popular in the public consciousness. The main point is that slippery slope-style arguments can be evaluated based on the strength of the claimed links between events. If those links are weak, then the argument is likely committing a slippery slope fallacy.

Today, we are going to talk about 7 slippery slope fallacy examples and how to avoid them in your everyday life.

Table of Contents

What is a Slippery Slope Fallacy?

Slippery slope-slope style arguments can are a kind of hypothetical reasoning and are made up of conditional claims:

- If A then B

- If B then C

- If Y then Z

Where A is the first event, Z is the final event, and B-Y are the intermediate links in the chain.

This argument pattern is fallacious when the claimed links between the events in the chain are weak or non-existent. In other words, the argument pattern fails if there is little reason to think that A will lead to B, or that B will lead C, and so on.

To learn more about fallacious arguments, here's an in-depth article about logical fallacies and why it's important to recognize them .

Types of Slippery Slope Arguments

Philosophers have identified 3 major kinds of slippery slope fallacies:

- Causal slippery slope: The idea that a small insignificant event will cause a major significant even down the road.

- Conceptual slippery slope: Claiming there is no meaningful difference between two things if you can go from one to the other via a step of small steps

- Precedential slippery slope: The idea that treating one small thing a certain way will lead to treating a significant thing the same way

It can be difficult to tell the types apart in normal conversation and many commonly encountered slippery slope arguments involve aspects of all three types . Despite their differences, all 3 types of slippery slope arguments share 3 core features:

- A start that seems mild

- An endpoint that is significant or extreme

- A series of small steps to connect one to the other

7 Slippery Slope Examples and Counterarguments

Here are some examples of slippery slope arguments in the wild. You’ll have likely heard some forms of at least one or two arguments below.

Argument : “We cannot allow more taxation, as any taxation incentivizes more taxation, which will inevitably lead to the loss of all private property and tyranny.”

Counterargument : This causal/precedential slippery slope pattern is commonly seen in arguments about whether we should increase or decrease taxes. This argument can be considered fallacious as there is little reason to think that raising taxes in some areas will cause a spiraling descent into tyranny and communism. After all, taxes and forms of private property have coexisted in pretty much every single society throughout history.

You could also argue that merely raising taxes on some class of individuals does not mean raising taxes on everyone , which is what the fallacious argument claims. The argument is even more unconvincing when you realize that, according to its own logic, we shouldn’t have any taxes whatsoever . That claim is just as unlikely as the claim that we should tax away everyone’s stuff.

2. Marriage

Argument : “Marriage is defined as a man and a woman. If we change the definition to include gay couples then we will soon change it again to cover other things. The next thing you know, we will have people wanting to marry animals and inanimate objects. Therefore, we should not change the definition of marriage.”

Counterargument : This argument combines aspects of a conceptual and precedential slippery slope fallacy. It claims that changing the definition of marriage to include gay couples is no different than changing the definition to allow people to marry animals and objects. The argument leaves out the possibility that there is a reasonable definition that explains why animals and inanimate objects can be excluded from the category of marriage.

For instance, a prerequisite of marriage is that it must take place between two consenting adults. Animals and objects are neither of those things so they can be excluded.

3. Catastrophizing Thoughts

Argument : “If I fail this test, then I will flunk the class. If I flunk the class, I will flunk out of school entirely. If I flunk out entirely then my entire future is ruined and I will never be able to get a good job and provide for a family!”

Counterargument: Pretty much everyone is guilty of “ catastrophizing ” like this sometimes. We tell ourselves that one bad thing will inevitably lead to another and another until our worst nightmares come true.

The key to shaking this kind of causal slippery slope is realizing that it's fallacious! One bad event does not necessarily mean more bad events will happen. And a single bad event is unlikely to lead directly to disastrous consequences.

It may not be true that the future will be like the past; the future could be different. Overcoming these kinds of limiting beliefs is important to navigate the world effectively.

4. Politics

Slippery slope arguments are all over the place in political discussions. Here is one you may have heard recently in the news:

Argument : “If we allow the government to remove Confederate statues from public places, then it’s a short road to the government trying to erase and censor history. Next thing you know, all our history textbooks will be altered to remove the truth. You don’t want the government telling you what to think is true, do you?”

Counterargument : Again, this argument assumes that a small event will have catastrophic consequences down the road. This argument shares features of a causal and precedential slippery slope. Removing statues meant to venerate Confederate generals is not erasing history and is unlikely to cause massive government censorship of history.

Historical facts about the Confederacy are still kept track of in libraries and museums and there is no movement to censor those things. The simple act of removing some historical artifact from a public place does not in itself count as censorship.

5. Healthcare

Argument: “ If we provide free healthcare then where does it stop? Soon people will be asking for free cars, free cell phones, free food, and free everything. The more people get free stuff, the less they will work which will eventually lead to economic ruin.”

Counterargument: This argument has features of a causal and precedential slippery slope. It can be challenged because there is little empirical evidence to support its conclusions.

There are several modern countries with universal healthcare that have healthy economies and don’t have a problem of people wanting too much free stuff. There is actually evidence that universal health care schemes are good for the economy and that welfare programs do not discourage people from looking for work .

6. Euthanasia

Argument : “We should not allow doctors to end the life of terminally ill patients because if we do, it’s not far off from letting doctors euthanize healthy people or people that they believe to be genetically inferior. That's what the Nazis did after all!”

Counterargument: This argument combines aspects of a conceptual, precedential, and causal slippery slope. By using gradated language, it obscures the fact that there is a clear conceptual distinction between voluntary and involuntary euthanasia .

Voluntary euthanasia is carried out under the express wishes of the patient and occurs with their consent. Involuntary euthanasia does not involve the consent of the patient. Involuntary euthanasia is murder and murder is already illegal . Allowing voluntary euthanasia won’t change that.

7. Rules and Exceptions

Argument: “I cannot make an exception for you, or else I would have to make an exception for others in the class. Eventually, I would have to make exceptions for everyone else and then the rules would be utterly meaningless!”

Counterargument: This argument is a precedential slippery slope. It’s fallacious because it treats the issue as if everyone always has to be granted an exception equally. Sometimes exceptions to rules are reasonable and will not set a precedent for disassembling the rules.

Various laws have exceptions but the laws still manage to function. What matters is the reason for granting the exception. In extenuating circumstances, it may be correct to give an exception to some established rules.

Why Are Slippery Slopes Fallacies?

Slippery slope-style arguments are often fallacious, but the reason why they are fallacious differs depending on the kind of slippery slope argument it is.

For Causal Slopes

Causal slippery slopes can be fallacious when there is little evidence to support the idea that one event will cause another and so on. Fallacious causal slippery slope arguments rely on exaggerating the strength or severity of causal connections between events.

Even if some hypothetical sequence of events is possible , the argument is fallacious if it is unlikely that the sequence of events will actually happen. If there is little evidence that the presented causal chain is likely, then the argument is weak.

For Conceptual Slopes

Conceptual slippery slope arguments can be fallacious as they deny that 2 categories of things are different because you can transition from one to the other through a series of small steps. Conceptual slippery slope fallacies ignore the possibility that we can differentiate between things even if they exist on a continuum or spectrum.

A good counterexample to this type of thinking is the category “bald.” There is no definite number of hairs that separates someone from being bald or not bald, but we can recognize clear instances of the two categories. Mr. Clean is bald and Cousin It is not bald. Conceptual slippery slopes share features in common with the continuum fallacy (sometimes called a Sorites fallacy).

For Precedential Slopes

Precedential slippery slope arguments are based on saying that some current behavior or event will set a precedent for future behavior or events. The idea is that if we treat a seemingly small thing a certain way now, we will have to treat a significant thing the same way in the future.

Precedential slippery slope arguments can be fallacious as they ignore the possibility that we can determine when precedent should or should not be followed . They also assume that the beginning and ending positions of the argument are similar enough that precedent would apply between them.

Precedential slippery slopes are usually combined with all-or-nothing thinking and often start by assuming a false dichotomy between two options. Precedential-style slope arguments might be valid in specific contexts (e.g. legal sphere) where precedent plays an integral role in making decisions.

Valid Slippery Slope Arguments

Slippery slope arguments are not inherently fallacious. Sometimes, a slippery slope argument can be an instance of valid reasoning. Consider the following argument:

“We can’t let people throw their trash on the sidewalk because, over time, that could build up to a big public nuisance and health hazard.”

This argument has a slippery slope structure. It claims that allowing some relatively small event (letting people litter) will lead to some larger negative effects (public annoyance and health issues). In this case, the argument is persuasive as there is good reason to believe that things will actually unfold in that manner .

Whether or not a slippery slope-style argument is reasonable depends on a number of factors including the type of slippery slope argument it is and the context of the argument. In some cases, it might not be clear if the argument is fallacious or not.

How to Respond to Slippery Slope Arguments

The exact way to respond to a slippery slope argument depends on the kind of slippery slope it is and what the specifics of the argument are. Here are a few general approaches to keep in mind:

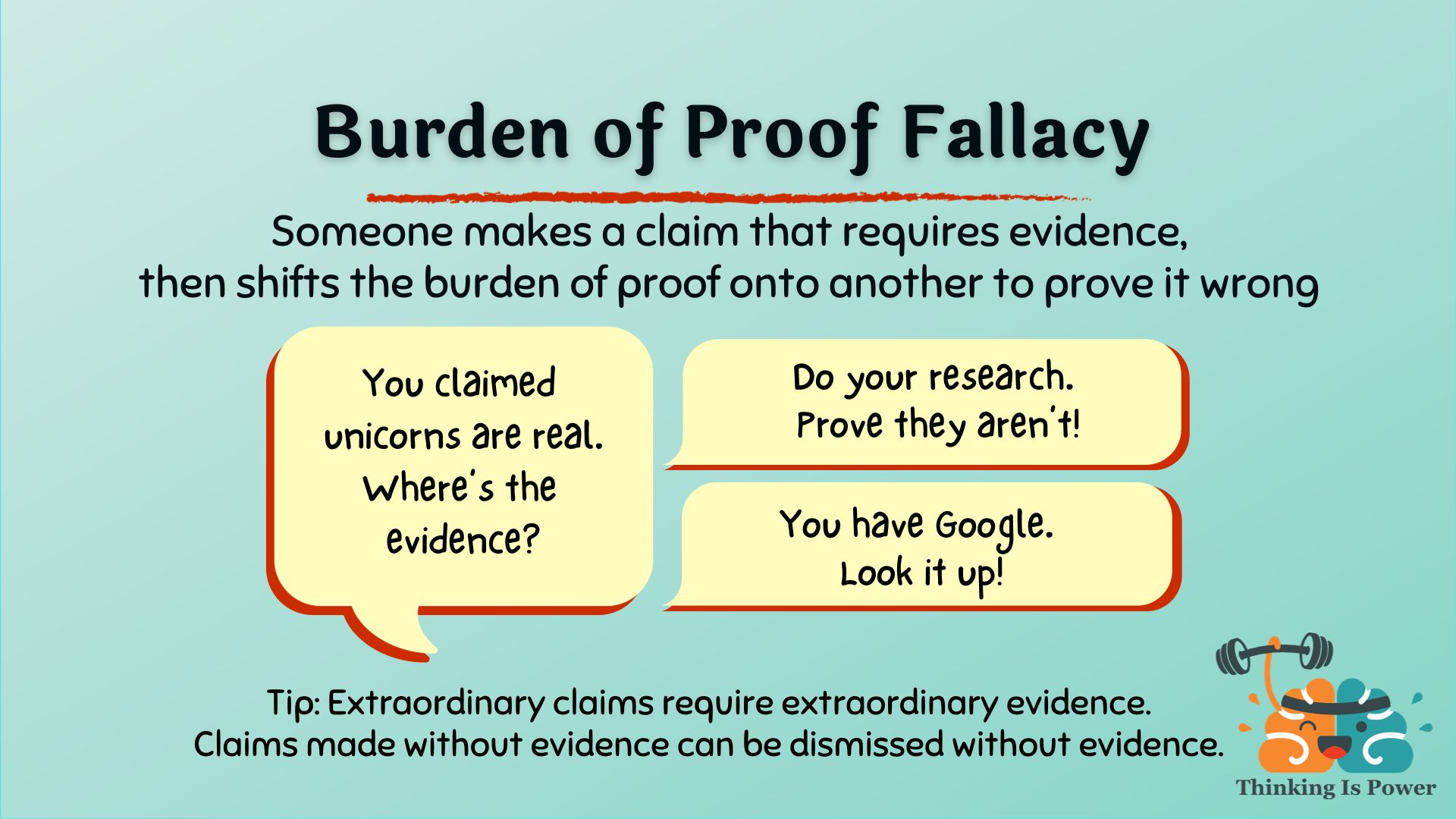

Ask your opponent for justification

If your opponent did not provide any evidence to support their suggested slope, then ask them to justify their view. The burden of proof is on them to make their case.

Highlight missing parts of the chain

Point out how the argument leaves out a lot of events between the first and last points. Pointing out these missing pieces can lessen the bite of the argument.

Emphasize the distance between the start and end

Pointing out a significant difference between the start point and endpoint might give a reason to think it’s justified to treat them in two different ways. Pointing out the distance between the two also makes it easier to see how it's unlikely one will lead to the other.

Stop the slope in its tracks

Try to find a reason that we can stop the slope in the transition period. There might be a good reason to think the slope will not proceed all the way if there is a principled stopping point. Show how you can prevent the initial event from leading to the final event.

Call out underlying premises

Sometimes a slippery slope is based on false assumptions. Addressing these incorrect assumptions directly might be more helpful than explaining the problem with the slope.

Provide a counterexample

If possible, present a counterexample to show your opponent’s logic is flawed. One way to do this might be to point out how slippery slope arguments can often be applied in both directions of an issue. For example, if your opponent argues that legalizing gay marriage will lead to obscene behavior, you could just as easily claim that restricting gay marriage could lead to restrictions on other kinds of marriage, eventually banning it altogether.

Learn More About Logical Fallacies

- 5 Appeal to Nature Fallacy Examples in Media and Life

- 6 Outcome Bias Examples That Can Negatively Impact Your Decisions

- 7 Self-Serving Bias Examples You See Throughout Life

- 7 Omission Bias Examples That Negatively Impact Your Life

- 6 Authority Bias Examples That Might Impact Your Decisions

- 5 Burden of Proof Fallacy Examples

- 5 Appeal to Tradition Fallacy Examples in Life

- 5 Appeal to Authority Logical Fallacy Examples

- 7 False Cause Fallacy Examples

- 7 Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy Examples

- 7 Appeal to Common Sense Logical Fallacy Examples

- 5 Post Hoc Fallacy Examples (and How to Respond to This Argument)

- Gambler’s Fallacy: 5 Examples and How to Avoid It

- 5 Appeal to Anger Fallacy Examples Throughout Life

- 7 Halo Effect Bias Examples in Your Daily Life

- 7 Poisoning the Well Examples Throughout Your Life

- 7 Survivorship Bias Examples You See in the Real World

- 7 Dunning Kruger Effect Examples in Your Life

- 7 Either Or (“False Dilemma”) Fallacy Examples in Real Life

- 5 Cui Bono Fallacy Examples to Find Out “Who Will Benefit”

- 6 Anchoring Bias Examples That Impact Your Decisions

- 7 Virtue Signaling Examples in Everyday Life

- 7 Cherry Picking Fallacy Examples for When People Ignore Evidence

- 9 Circular Reasoning Examples (or “Begging the Question”) in Everyday Life

- 9 Appeal to Emotion Logical Fallacy Examples

- 9 Appeal to Pity Fallacy (“Ad Misericordiam”) Examples in Everyday Life

- 9 Loaded Question Fallacy Examples in Life and Media

- 9 Confirmation Bias Fallacy Examples In Everyday Life

- 9 Bandwagon Fallacy Examples to Prevent Poor Decisions

- 5 Red Herring Fallacy Examples to Fight Irrelevant Information

- 9 Middle Ground Fallacy Examples to Spot During an Argument

- 5 False Equivalence Examples to Know Before Your Next Argument

- 7 Hasty Generalization Fallacy Examples & How to Respond to Them

- 6 Straw Man Fallacy Examples & How You Can Respond

- 6 False Dichotomy Examples & How to Counter Them

Final Thoughts on Slippery Slope Fallacies

Slippery slope fallacies are fairly common in everyday life and often go undetected. One explanation for our tendency to think in this fallacious manner has to do with how our brains are wired for making predictions . Humans have a natural knack for visualizing lines of possibilities, but this talent can get in the way of our rational faculties. We jump from inference to inference and might not slow down to ask if we are justified in making those inferences.

Fallacious thinking can have serious negative consequences, so educating your critical thinking faculties to recognize fallacies like slippery slopes is an invaluable skill. Like any muscle, the brain needs practice to get stronger. Identifying instances of slippery slope argument in everyday life will help you make more effective decisions, promote self-awareness , and liberate you from constrained thinking habits.

Also, if you're interested in learning about other types of fallacies, here's our in-depth look at the straw man fallacy .

Finally, if you want a simple process to counter the logical fallacies and cognitive biases you encounter in life, then follow this 7-step process to develop the critical thinking skills habit .

Alex Bolano is a freelance writer based out of St. Louis. He holds his MA in Philosophy and writes on topics relating to science, culture, politics, finance, and education. He enjoys playing video games and researching the latest trends in science and technology.

Unit 1: What Is Philosophy?

LOGOS: Critical Thinking, Arguments, and Fallacies

Heather Wilburn, Ph.D

Critical Thinking:

With respect to critical thinking, it seems that everyone uses this phrase. Yet, there is a fear that this is becoming a buzz-word (i.e. a word or phrase you use because it’s popular or enticing in some way). Ultimately, this means that we may be using the phrase without a clear sense of what we even mean by it. So, here we are going to think about what this phrase might mean and look at some examples. As a former colleague of mine, Henry Imler, explains:

By critical thinking, we refer to thinking that is recursive in nature. Any time we encounter new information or new ideas, we double back and rethink our prior conclusions on the subject to see if any other conclusions are better suited. Critical thinking can be contrasted with Authoritarian thinking. This type of thinking seeks to preserve the original conclusion. Here, thinking and conclusions are policed, as to question the system is to threaten the system. And threats to the system demand a defensive response. Critical thinking is short-circuited in authoritarian systems so that the conclusions are conserved instead of being open for revision. [1]

A condition for being recursive is to be open and not arrogant. If we come to a point where we think we have a handle on what is True, we are no longer open to consider, discuss, or accept information that might challenge our Truth. One becomes closed off and rejects everything that is different or strange–out of sync with one’s own Truth. To be open and recursive entails a sense of thinking about your beliefs in a critical and reflective way, so that you have a chance to either strengthen your belief system or revise it if needed. I have been teaching philosophy and humanities classes for nearly 20 years; critical thinking is the single most important skill you can develop. In close but second place is communication, In my view, communication skills follow as a natural result of critical thinking because you are attempting to think through and articulate stronger and rationally justified views. At the risk of sounding cliche, education isn’t about instilling content; it is about learning how to think.

In your philosophy classes your own ideas and beliefs will very likely be challenged. This does not mean that you will be asked to abandon your beliefs, but it does mean that you might be asked to defend them. Additionally, your mind will probably be twisted and turned about, which can be an uncomfortable experience. Yet, if at all possible, you should cherish these experiences and allow them to help you grow as a thinker. To be challenged and perplexed is difficult; however, it is worthwhile because it compels deeper thinking and more significant levels of understanding. In turn, thinking itself can transform us not only in thought, but in our beliefs, and our actions. Hannah Arendt, a social and political philosopher that came to the United States in exile during WWII, relates the transformative elements of philosophical thinking to Socrates. She writes:

Socrates…who is commonly said to have believed in the teachability of virtue, seems to have held that talking and thinking about piety, justice, courage, and the rest were liable to make men more pious, more just, more courageous, even though they were not given definitions or “values” to direct their further conduct. [2]

Thinking and communication are transformative insofar as these activities have the potential to alter our perspectives and, thus, change our behavior. In fact, Arendt connects the ability to think critically and reflectively to morality. As she notes above, morality does not have to give a predetermined set of rules to affect our behavior. Instead, morality can also be related to the open and sometimes perplexing conversations we have with others (and ourselves) about moral issues and moral character traits. Theodor W. Adorno, another philosopher that came to the United States in exile during WWII, argues that autonomous thinking (i.e. thinking for oneself) is crucial if we want to prevent the occurrence of another event like Auschwitz, a concentration camp where over 1 million individuals died during the Holocaust. [3] To think autonomously entails reflective and critical thinking—a type of thinking rooted in philosophical activity and a type of thinking that questions and challenges social norms and the status quo. In this sense thinking is critical of what is, allowing us to think beyond what is and to think about what ought to be, or what ought not be. This is one of the transformative elements of philosophical activity and one that is useful in promoting justice and ethical living.

With respect to the meaning of education, the German philosopher Hegel uses the term bildung, which means education or upbringing, to indicate the differences between the traditional type of education that focuses on facts and memorization, and education as transformative. Allen Wood explains how Hegel uses the term bildung: it is “a process of self-transformation and an acquisition of the power to grasp and articulate the reasons for what one believes or knows.” [4] If we think back through all of our years of schooling, particularly those subject matters that involve the teacher passing on information that is to be memorized and repeated, most of us would be hard pressed to recall anything substantial. However, if the focus of education is on how to think and the development of skills include analyzing, synthesizing, and communicating ideas and problems, most of us will use those skills whether we are in the field of philosophy, politics, business, nursing, computer programming, or education. In this sense, philosophy can help you develop a strong foundational skill set that will be marketable for your individual paths. While philosophy is not the only subject that will foster these skills, its method is one that heavily focuses on the types of activities that will help you develop such skills.

Let’s turn to discuss arguments. Arguments consist of a set of statements, which are claims that something is or is not the case, or is either true or false. The conclusion of your argument is a statement that is being argued for, or the point of view being argued for. The other statements serve as evidence or support for your conclusion; we refer to these statements as premises. It’s important to keep in mind that a statement is either true or false, so questions, commands, or exclamations are not statements. If we are thinking critically we will not accept a statement as true or false without good reason(s), so our premises are important here. Keep in mind the idea that supporting statements are called premises and the statement that is being supported is called the conclusion. Here are a couple of examples:

Example 1: Capital punishment is morally justifiable since it restores some sense of

balance to victims or victims’ families.

Let’s break it down so it’s easier to see in what we might call a typical argument form:

Premise: Capital punishment restores some sense of balance to victims or victims’ families.

Conclusion: Capital punishment is morally justifiable.

Example 2 : Because innocent people are sometimes found guilty and potentially

executed, capital punishment is not morally justifiable.

Premise: Innocent people are sometimes found guilty and potentially executed.

Conclusion: Capital punishment is not morally justifiable.

It is worth noting the use of the terms “since” and “because” in these arguments. Terms or phrases like these often serve as signifiers that we are looking at evidence, or a premise.

Check out another example:

Example 3 : All human beings are mortal. Heather is a human being. Therefore,

Heather is mortal.

Premise 1: All human beings are mortal.

Premise 2: Heather is a human being.

Conclusion: Heather is mortal.

In this example, there are a couple of things worth noting: First, there can be more than one premise. In fact, you could have a rather complex argument with several premises. If you’ve written an argumentative paper you may have encountered arguments that are rather complex. Second, just as the arguments prior had signifiers to show that we are looking at evidence, this argument has a signifier (i.e. therefore) to demonstrate the argument’s conclusion.

So many arguments!!! Are they all equally good?

No, arguments are not equally good; there are many ways to make a faulty argument. In fact, there are a lot of different types of arguments and, to some extent, the type of argument can help us figure out if the argument is a good one. For a full elaboration of arguments, take a logic class! Here’s a brief version:

Deductive Arguments: in a deductive argument the conclusion necessarily follows the premises. Take argument Example 3 above. It is absolutely necessary that Heather is a mortal, if she is a human being and if mortality is a specific condition for being human. We know that all humans die, so that’s tight evidence. This argument would be a very good argument; it is valid (i.e the conclusion necessarily follows the premises) and it is sound (i.e. all the premises are true).

Inductive Arguments : in an inductive argument the conclusion likely (at best) follows the premises. Let’s have an example:

Example 4 : 98.9% of all TCC students like pizza. You are a TCC student. Thus, you like pizza.

Premise 1: 98.9% of all TCC students like pizza

Premise 2: You are a TCC student.

Conclusion: You like pizza. (*Thus is a conclusion indicator)

In this example, the conclusion doesn’t necessarily follow; it likely follows. But you might be part of that 1.1% for whatever reason. Inductive arguments are good arguments if they are strong. So, instead of saying an inductive argument is valid, we say it is strong. You can also use the term sound to describe the truth of the premises, if they are true. Let’s suppose they are true and you absolutely love Hideaway pizza. Let’s also assume you are a TCC student. So, the argument is really strong and it is sound.

There are many types of inductive argument, including: causal arguments, arguments based on probabilities or statistics, arguments that are supported by analogies, and arguments that are based on some type of authority figure. So, when you encounter an argument based on one of these types, think about how strong the argument is. If you want to see examples of the different types, a web search (or a logic class!) will get you where you need to go.

Some arguments are faulty, not necessarily because of the truth or falsity of the premises, but because they rely on psychological and emotional ploys. These are bad arguments because people shouldn’t accept your conclusion if you are using scare tactics or distracting and manipulating reasoning. Arguments that have this issue are called fallacies. There are a lot of fallacies, so, again, if you want to know more a web search will be useful. We are going to look at several that seem to be the most relevant for our day-to-day experiences.

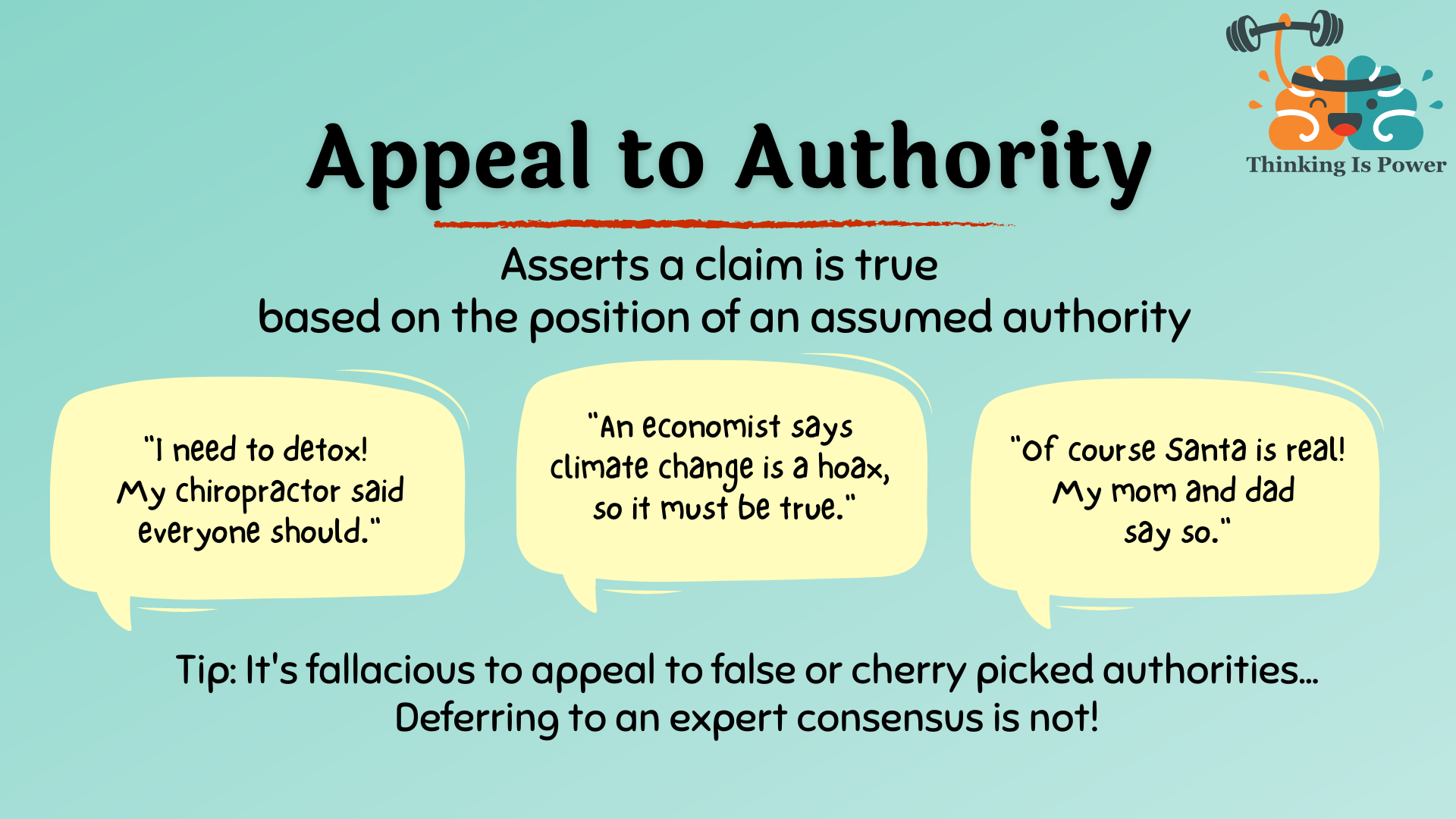

- Inappropriate Appeal to Authority : We are definitely going to use authority figures in our lives (e.g. doctors, lawyers, mechanics, financial advisors, etc.), but we need to make sure that the authority figure is a reliable one.

Things to look for here might include: reputation in the field, not holding widely controversial views, experience, education, and the like. So, if we take an authority figure’s word and they’re not legit, we’ve committed the fallacy of appeal to authority.

Example 5 : I think I am going to take my investments to Voya. After all, Steven Adams advocates for Voya in an advertisement I recently saw.

If we look at the criteria for evaluating arguments that appeal to authority figures, it is pretty easy to see that Adams is not an expert in the finance field. Thus, this is an inappropropriate appeal to authority.

- Slippery Slope Arguments : Slippery slope arguments are found everywhere it seems. The essential characteristic of a slippery slope argument is that it uses problematic premises to argue that doing ‘x’ will ultimately lead to other actions that are extreme, unlikely, and disastrous. You can think of this type of argument as a faulty chain of events or domino effect type of argument.

Example 6 : If you don’t study for your philosophy exam you will not do well on the exam. This will lead to you failing the class. The next thing you know you will have lost your scholarship, dropped out of school, and will be living on the streets without any chance of getting a job.

While you should certainly study for your philosophy exam, if you don’t it is unlikely that this will lead to your full economic demise.

One challenge to evaluating slippery slope arguments is that they are predictions, so we cannot be certain about what will or will not actually happen. But this chain of events type of argument should be assessed in terms of whether the outcome will likely follow if action ‘x” is pursued.

- Faulty Analogy : We often make arguments based on analogy and these can be good arguments. But we often use faulty reasoning with analogies and this is what we want to learn how to avoid.

When evaluating an argument that is based on an analogy here are a few things to keep in mind: you want to look at the relevant similarities and the relevant differences between the things that are being compared. As a general rule, if there are more differences than similarities the argument is likely weak.

Example 7 : Alcohol is legal. Therefore, we should legalize marijuana too.

So, the first step here is to identify the two things being compared, which are alcohol and marijuana. Next, note relevant similarities and differences. These might include effects on health, community safety, economic factors, criminal justice factors, and the like.

This is probably not the best argument in support for marijuana legalization. It would seem that one could just as easily conclude that since marijuana is illegal, alcohol should be too. In fact, one might find that alcohol is an often abused and highly problematic drug for many people, so it is too risky to legalize marijuana if it is similar to alcohol.

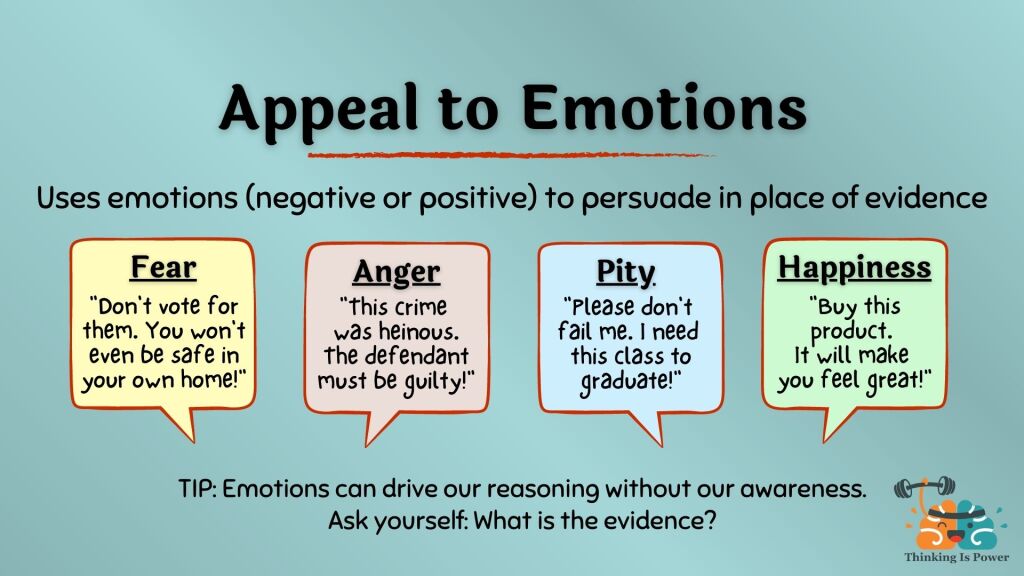

- Appeal to Emotion : Arguments should be based on reason and evidence, not emotional tactics. When we use an emotional tactic, we are essentially trying to manipulate someone into accepting our position by evoking pity or fear, when our positions should actually be backed by reasonable and justifiable evidence.

Example 8 : Officer please don’t give me a speeding ticket. My girlfriend broke up with me last night, my alarm didn’t go off this morning, and I’m late for class.

While this is a really horrible start to one’s day, being broken up with and an alarm malfunctioning is not a justifiable reason for speeding.

Example 9 : Professor, I’d like you to remember that my mother is a dean here at TCC. I’m sure that she will be very disappointed if I don’t receive an A in your class.

This is a scare tactic and is not a good way to make an argument. Scare tactics can come in the form of psychological or physical threats; both forms are to be avoided.

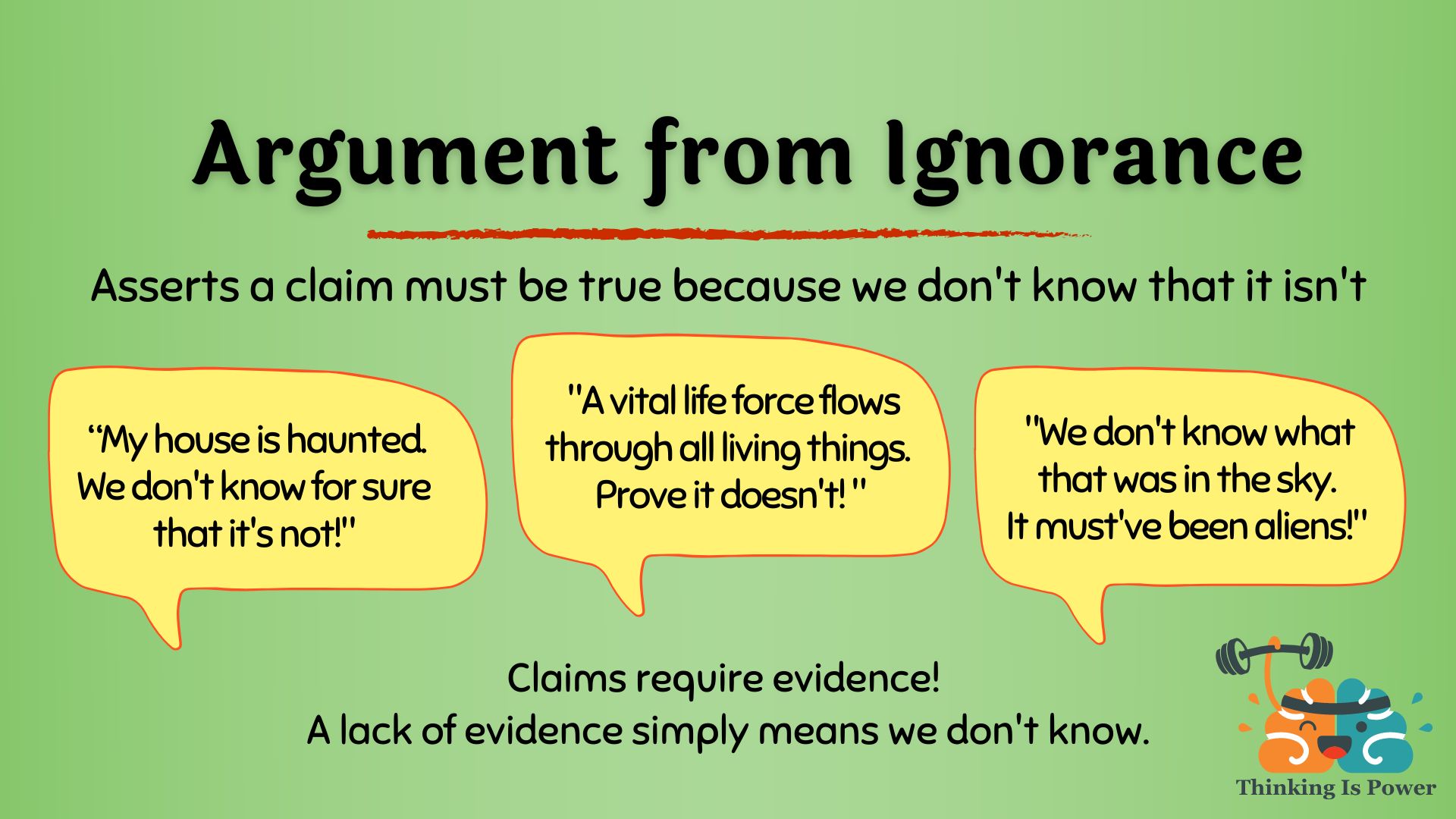

- Appeal to Ignorance : This fallacy occurs when our argument relies on lack of evidence when evidence is actually needed to support a position.

Example 10 : No one has proven that sasquatch doesn’t exist; therefore it does exist.

Example 11 : No one has proven God exists; therefore God doesn’t exist.

The key here is that lack of evidence against something cannot be an argument for something. Lack of evidence can only show that we are ignorant of the facts.

- Straw Man : A straw man argument is a specific type of argument that is intended to weaken an opponent’s position so that it is easier to refute. So, we create a weaker version of the original argument (i.e. a straw man argument), so when we present it everyone will agree with us and denounce the original position.

Example 12 : Women are crazy arguing for equal treatment. No one wants women hanging around men’s locker rooms or saunas.

This is a misrepresentation of arguments for equal treatment. Women (and others arguing for equal treatment) are not trying to obtain equal access to men’s locker rooms or saunas.

The best way to avoid this fallacy is to make sure that you are not oversimplifying or misrepresenting others’ positions. Even if we don’t agree with a position, we want to make the strongest case against it and this can only be accomplished if we can refute the actual argument, not a weakened version of it. So, let’s all bring the strongest arguments we have to the table!

- Red Herring : A red herring is a distraction or a change in subject matter. Sometimes this is subtle, but if you find yourself feeling lost in the argument, take a close look and make sure there is not an attempt to distract you.

Example 13 : Can you believe that so many people are concerned with global warming? The real threat to our country is terrorism.

It could be the case that both global warming and terrorism are concerns for us. But the red herring fallacy is committed when someone tries to distract you from the argument at hand by bringing up another issue or side-stepping a question. Politicians are masters at this, by the way.

- Appeal to the Person : This fallacy is also referred to as the ad hominem fallacy. We commit this fallacy when we dismiss someone’s argument or position by attacking them instead of refuting the premises or support for their argument.

Example 14 : I am not going to listen to what Professor ‘X’ has to say about the history of religion. He told one of his previous classes he wasn’t religious.

The problem here is that the student is dismissing course material based on the professor’s religious views and not evaluating the course content on its own ground.

To avoid this fallacy, make sure that you target the argument or their claims and not the person making the argument in your rebuttal.

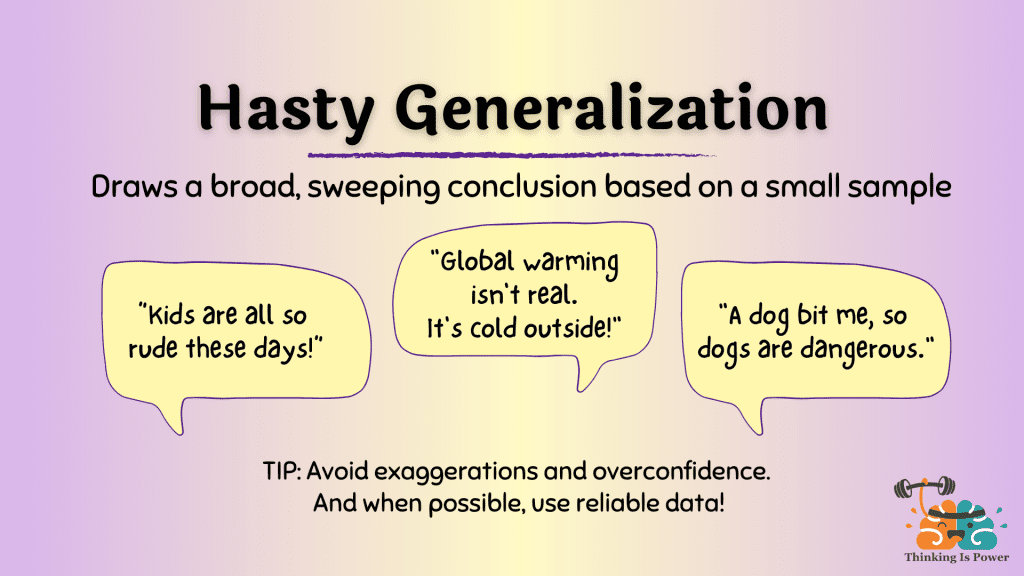

- Hasty Generalization : We make and use generalizations on a regular basis and in all types of decisions. We rely on generalizations when trying to decide which schools to apply to, which phone is the best for us, which neighborhood we want to live in, what type of job we want, and so on. Generalizations can be strong and reliable, but they can also be fallacious. There are three main ways in which a generalization can commit a fallacy: your sample size is too small, your sample size is not representative of the group you are making a generalization about, or your data could be outdated.

Example 15 : I had horrible customer service at the last Starbucks I was at. It is clear that Starbucks employees do not care about their customers. I will never visit another Starbucks again.

The problem with this generalization is that the claim made about all Starbucks is based on one experience. While it is tempting to not spend your money where people are rude to their customers, this is only one employee and presumably doesn’t reflect all employees or the company as a whole. So, to make this a stronger generalization we would want to have a larger sample size (multiple horrible experiences) to support the claim. Let’s look at a second hasty generalization:

Example 16 : I had horrible customer service at the Starbucks on 81st street. It is clear that Starbucks employees do not care about their customers. I will never visit another Starbucks again.

The problem with this generalization mirrors the previous problem in that the claim is based on only one experience. But there’s an additional issue here as well, which is that the claim is based off of an experience at one location. To make a claim about the whole company, our sample group needs to be larger than one and it needs to come from a variety of locations.

- Begging the Question : An argument begs the question when the argument’s premises assume the conclusion, instead of providing support for the conclusion. One common form of begging the question is referred to as circular reasoning.

Example 17 : Of course, everyone wants to see the new Marvel movie is because it is the most popular movie right now!

The conclusion here is that everyone wants to see the new Marvel movie, but the premise simply assumes that is the case by claiming it is the most popular movie. Remember the premise should give reasons for the conclusion, not merely assume it to be true.

- Equivocation : In the English language there are many words that have different meanings (e.g. bank, good, right, steal, etc.). When we use the same word but shift the meaning without explaining this move to your audience, we equivocate the word and this is a fallacy. So, if you must use the same word more than once and with more than one meaning you need to explain that you’re shifting the meaning you intend. Although, most of the time it is just easier to use a different word.

Example 18 : Yes, philosophy helps people argue better, but should we really encourage people to argue? There is enough hostility in the world.

Here, argue is used in two different senses. The meaning of the first refers to the philosophical meaning of argument (i.e. premises and a conclusion), whereas the second sense is in line with the common use of argument (i.e. yelling between two or more people, etc.).

- Henry Imler, ed., Phronesis An Ethics Primer with Readings, (2018). 7-8. ↵

- Arendt, Hannah, “Thinking and Moral Considerations,” Social Research, 38:3 (1971: Autumn): 431. ↵

- Theodor W. Adorno, “Education After Auschwitz,” in Can One Live After Auschwitz, ed. by Rolf Tiedemann, trans. by Rodney Livingstone (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003): 23. ↵

- Allen W. Wood, “Hegel on Education,” in Philosophers on Education: New Historical Perspectives, ed. Amelie O. Rorty (London: Routledge 1998): 302. ↵

LOGOS: Critical Thinking, Arguments, and Fallacies Copyright © 2020 by Heather Wilburn, Ph.D is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Think Critically, Live Honestly

Slippery Slope

Imagine a tiny snowball rolling down a hill, growing into a massive avalanche - that's the essence of a certain reasoning error. It's the unfounded belief that one small action will inevitably trigger a domino effect, leading to a catastrophic outcome, often without any solid evidence or consideration of possible interventions along the way. This dramatic oversimplification, fueled by fear and exaggeration, is a captivating yet flawed way of thinking, as it overlooks the complexity and unpredictability of real-life situations.

- Cause and Effect

- Probability and Possibility

Definition of Slippery Slope

A Slippery Slope is a logical fallacy that assumes a relatively small first step will inevitably lead to a chain of related events culminating in some significant impact, usually negative. This fallacy is often characterized by a lack of evidence that these events are causally linked or that this disastrous outcome is certain to happen. It is based on speculation rather than facts, and it relies on fear and exaggeration to make a point. The argument is flawed because it ignores the possibility that we can stop the progression at any point in the 'slope'. In essence, the Slippery Slope fallacy oversimplifies potential outcomes by suggesting that a single action will necessarily cause a specific, often extreme, result.

In Depth Explanation

The Slippery Slope fallacy is a fascinating error in reasoning that can be quite captivating to explore. It's like a snowball rolling down a hill, gaining momentum and size as it descends, except in this case, the snowball is an argument, and the hill is a chain of events or consequences. The Slippery Slope fallacy occurs when someone argues that a particular action will inevitably lead to a specific chain of events or outcomes, without providing any substantive evidence to support this claim. Imagine you're standing at the top of a hill. You take a step forward and suddenly, you're sliding uncontrollably down the slope. This is the visual metaphor that underpins the Slippery Slope fallacy. It suggests that one action (the step forward) will inevitably lead to a catastrophic outcome (sliding down the hill), without any chance to stop or change direction. In abstract reasoning, the Slippery Slope fallacy often manifests itself in arguments where the connection between the initial action and the predicted outcome is either weak or non-existent. The person making the argument assumes that because one event follows another, the first event must be the cause of the second. This is a fallacy because it ignores the possibility of other intervening variables or events that could influence the outcome. The logical structure of the Slippery Slope fallacy is fairly straightforward. It begins with an initial action or decision, followed by a series of events or outcomes that are predicted to occur as a direct result of the initial action. The fallacy lies in the assumption that these events will inevitably occur, without any evidence to support this claim. The potential impact of the Slippery Slope fallacy on rational discourse is significant. It can lead to fear-mongering, as people may be swayed by the catastrophic outcomes predicted in the argument, even if there is no evidence to suggest these outcomes will occur. It can also stifle debate and discussion, as it presents the outcome as inevitable, leaving no room for alternative viewpoints or solutions. Understanding the Slippery Slope fallacy is crucial for anyone interested in critical thinking and logical analysis. It's a common error in reasoning that can easily sway public opinion and stifle rational discourse. By recognizing this fallacy, we can challenge unsupported claims and promote more balanced, evidence-based discussions.

Real World Examples

1. Gun Control: A common example of the slippery slope fallacy is often seen in debates about gun control. One side might argue, "If we allow the government to regulate our right to own guns, it won't be long before they come for our other rights. Next, they'll be limiting our freedom of speech, then our right to assemble, and before we know it, we'll be living in a totalitarian state." This argument assumes that one action (regulating gun ownership) will inevitably lead to a series of progressively worse outcomes, without providing any evidence to support this chain of events. 2. Internet Censorship: Another example can be seen in discussions about internet censorship. Someone might argue, "If the government starts censoring the internet, it's only a matter of time before they start controlling everything we see and hear. Soon, they'll be monitoring our personal conversations, tracking our every move, and we'll have no privacy left at all." This argument uses the slippery slope fallacy by suggesting that a single action (internet censorship) will inevitably lead to extreme outcomes, without providing evidence to support this progression. 3. Alcohol Consumption: A parent might tell their teenager, "If you start drinking alcohol, even casually, it will lead to harder drugs. Before you know it, you'll be addicted to heroin and your life will be ruined." This argument commits the slippery slope fallacy by assuming that a single action (drinking alcohol) will inevitably lead to a worst-case scenario (heroin addiction), without any evidence to support this progression. While it's true that some people who drink alcohol also use harder drugs, it's not accurate or fair to suggest that one always leads to the other.

Countermeasures

Countering a slippery slope argument requires a focus on the logical structure of the argument itself. Here are some strategies: 1. Question the Causal Link: Ask for evidence that supports the claim that one event will inevitably lead to the other. This challenges the assumption that a minor action will result in a major, typically negative, outcome. 2. Demand Precision: Request for clarity and specificity about the steps involved in the supposed slope. This can expose gaps or flaws in the argument. 3. Encourage a Balanced View: Promote the consideration of potential positive outcomes or neutral effects, not just negative ones. This can help to counteract the fear-based reasoning often used in slippery slope arguments. 4. Promote Critical Thinking: Encourage the use of critical thinking skills to evaluate the argument. This can help to identify any flaws or biases in the reasoning. 5. Advocate for Reasonable Limits: Argue for the possibility of setting reasonable limits or safeguards to prevent the feared outcome. This can challenge the idea that there are no possible interventions to stop the slide down the slope. 6. Use Counterexamples: While avoiding relying solely on examples, judicious use of counterexamples can be effective. This can demonstrate that the supposed inevitable outcome is not, in fact, inevitable. 7. Challenge Assumptions: Question the underlying assumptions of the argument. This can reveal any biases or prejudices that may be influencing the reasoning. 8. Encourage Empirical Evidence: Ask for empirical evidence to support the claims being made. This can help to ensure that the argument is based on facts, not just speculation or fear. Remember, the goal is not to attack the person making the argument, but to challenge the logic of the argument itself. This approach promotes respectful and productive dialogue.

Thought Provoking Questions

1. Can you identify a situation where you have assumed that a small action or decision would inevitably lead to a significant, usually negative, outcome without concrete evidence to support this belief? 2. Have you ever used fear or exaggeration to emphasize a point, rather than relying on factual evidence? Can you see how this might lead to a slippery slope fallacy? 3. Can you recall a time when you oversimplified potential outcomes by suggesting that a single action would necessarily cause a specific, often extreme, result? How might this have affected your decision-making process? 4. Can you think of an instance where you ignored the possibility of stopping the progression at any point in the 'slope'? How might acknowledging this possibility have changed your perspective or approach?

Weekly Newsletter

Gain insights and clarity each week as we explore logical fallacies in our world. Sharpen your critical thinking and stay ahead in a world of misinformation. Sign up today!

Guide to the Most Common Logical Fallacies

Logical fallacies are flaws in reasoning that weaken or invalidate an argument. Whether they’re used intentionally or unintentionally, they can be quite persuasive. Learning how to identify fallacies is an excellent way to avoid being fooled or manipulated by faulty arguments. It will also help you avoid making fallacious arguments yourself!

Scroll through to learn to identify some of the more common fallacies. Once you can recognize them, you’ll see them everywhere!

A note on how to use this post: This page is a resource of the most common logical fallacies, and is not intended to be read from top to bottom. Feel free to share the graphics to help educate others about errors in reasoning. Hopefully together we can encourage more productive (and logical!) dialogue.

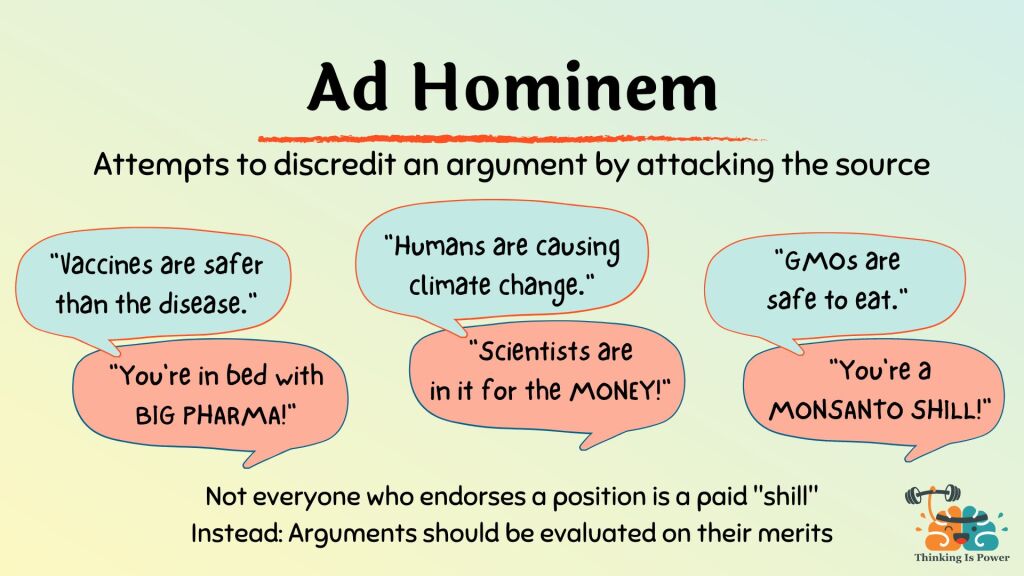

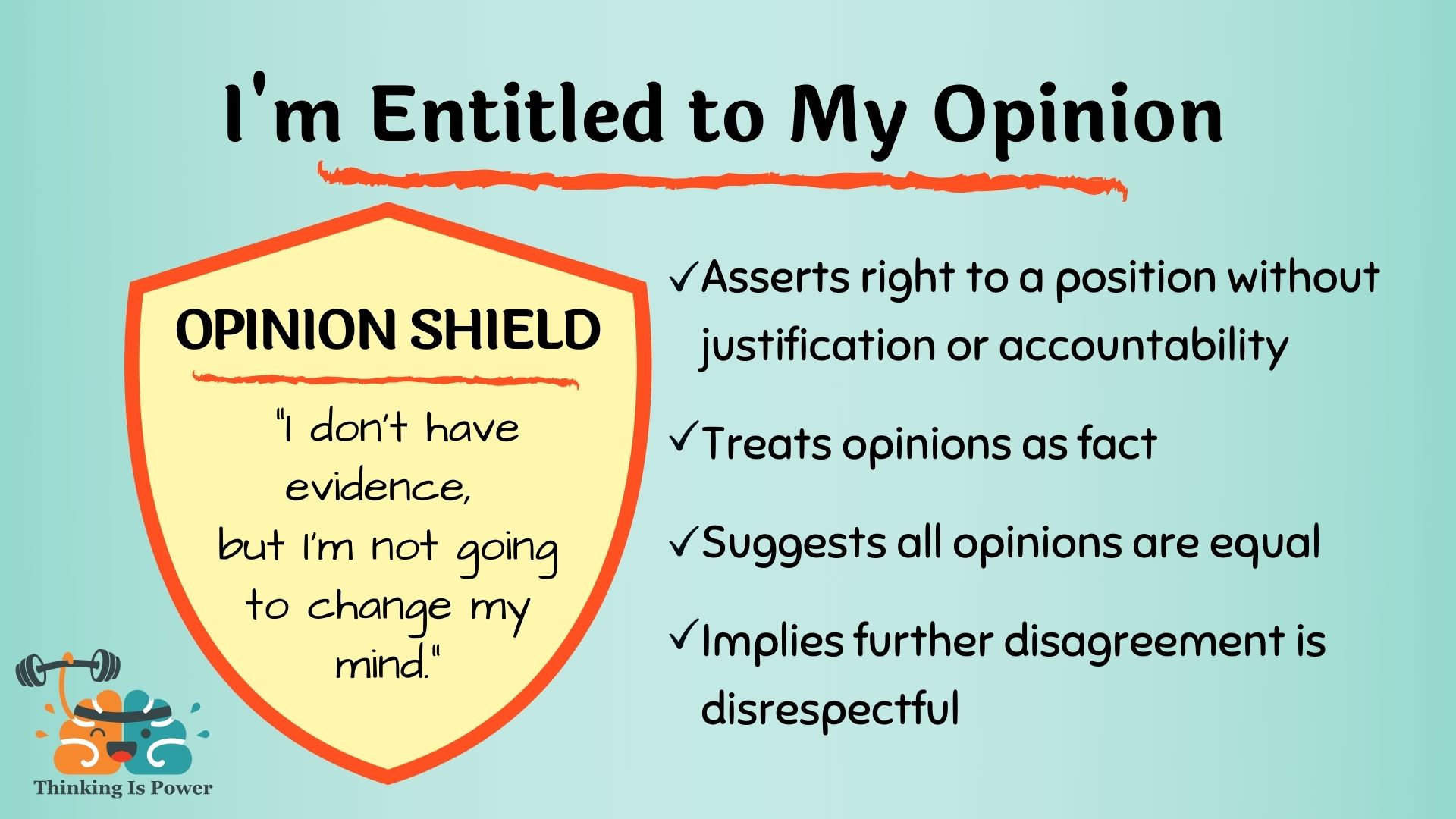

Other names: Personal attack, name-calling

Definition and explanation : Latin for “to the person,” the ad hominem fallacy is a personal attack. Essentially, instead of addressing the substance of an argument, someone is attempting to discredit the argument by attacking the source.