Renewable Energy

Renewable energy comes from sources that will not be used up in our lifetimes, such as the sun and wind.

Earth Science, Experiential Learning, Engineering, Geology

Wind Turbines in a Sheep Pasture

Wind turbines use the power of wind to generate energy. This is just one source of renewable energy.

Photograph by Jesus Keller/ Shutterstock

The wind, the sun, and Earth are sources of renewable energy . These energy sources naturally renew, or replenish themselves.

Wind, sunlight, and the planet have energy that transforms in ways we can see and feel. We can see and feel evidence of the transfer of energy from the sun to Earth in the sunlight shining on the ground and the warmth we feel when sunlight shines on our skin. We can see and feel evidence of the transfer of energy in wind’s ability to pull kites higher into the sky and shake the leaves on trees. We can see and feel evidence of the transfer of energy in the geothermal energy of steam vents and geysers .

People have created different ways to capture the energy from these renewable sources.

Solar Energy

Solar energy can be captured “actively” or “passively.”

Active solar energy uses special technology to capture the sun’s rays. The two main types of equipment are photovoltaic cells (also called PV cells or solar cells) and mirrors that focus sunlight in a specific spot. These active solar technologies use sunlight to generate electricity , which we use to power lights, heating systems, computers, and televisions.

Passive solar energy does not use any equipment. Instead, it gets energy from the way sunlight naturally changes throughout the day. For example, people can build houses so their windows face the path of the sun. This means the house will get more heat from the sun. It will take less energy from other sources to heat the house.

Other examples of passive solar technology are green roofs , cool roofs, and radiant barriers . Green roofs are completely covered with plants. Plants can get rid of pollutants in rainwater and air. They help make the local environment cleaner.

Cool roofs are painted white to better reflect sunlight. Radiant barriers are made of a reflective covering, such as aluminum. They both reflect the sun’s heat instead of absorbing it. All these types of roofs help lower the amount of energy needed to cool the building.

Advantages and Disadvantages There are many advantages to using solar energy. PV cells last for a long time, about 20 years.

However, there are reasons why solar power cannot be used as the only power source in a community. It can be expensive to install PV cells or build a building using passive solar technology.

Sunshine can also be hard to predict. It can be blocked by clouds, and the sun doesn’t shine at night. Different parts of Earth receive different amounts of sunlight based on location, the time of year, and the time of day.

Wind Energy

People have been harnessing the wind’s energy for a long, long time. Five-thousand years ago, ancient Egyptians made boats powered by the wind. In 200 B.C.E., people used windmills to grind grain in the Middle East and pump water in China.

Today, we capture the wind’s energy with wind turbines . A turbine is similar to a windmill; it has a very tall tower with two or three propeller-like blades at the top. These blades are turned by the wind. The blades turn a generator (located inside the tower), which creates electricity.

Groups of wind turbines are known as wind farms . Wind farms can be found near farmland, in narrow mountain passes, and even in the ocean, where there are steadier and stronger winds. Wind turbines anchored in the ocean are called “ offshore wind farms.”

Wind farms create electricity for nearby homes, schools, and other buildings.

Advantages and Disadvantages Wind energy can be very efficient . In places like the Midwest in the United States and along coasts, steady winds can provide cheap, reliable electricity.

Another great advantage of wind power is that it is a “clean” form of energy. Wind turbines do not burn fuel or emit any pollutants into the air.

Wind is not always a steady source of energy, however. Wind speed changes constantly, depending on the time of day, weather , and geographic location. Currently, it cannot be used to provide electricity for all our power needs.

Wind turbines can also be dangerous for bats and birds. These animals cannot always judge how fast the blades are moving and crash into them.

Geothermal Energy

Deep beneath the surface is Earth’s core . The center of Earth is extremely hot—thought to be over 6,000 °C (about 10,800 °F). The heat is constantly moving toward the surface.

We can see some of Earth’s heat when it bubbles to the surface. Geothermal energy can melt underground rocks into magma and cause the magma to bubble to the surface as lava . Geothermal energy can also heat underground sources of water and force it to spew out from the surface. This stream of water is called a geyser.

However, most of Earth’s heat stays underground and makes its way out very, very slowly.

We can access underground geothermal heat in different ways. One way of using geothermal energy is with “geothermal heat pumps.” A pipe of water loops between a building and holes dug deep underground. The water is warmed by the geothermal energy underground and brings the warmth aboveground to the building. Geothermal heat pumps can be used to heat houses, sidewalks, and even parking lots.

Another way to use geothermal energy is with steam. In some areas of the world, there is underground steam that naturally rises to the surface. The steam can be piped straight to a power plant. However, in other parts of the world, the ground is dry. Water must be injected underground to create steam. When the steam comes to the surface, it is used to turn a generator and create electricity.

In Iceland, there are large reservoirs of underground water. Almost 90 percent of people in Iceland use geothermal as an energy source to heat their homes and businesses.

Advantages and Disadvantages An advantage of geothermal energy is that it is clean. It does not require any fuel or emit any harmful pollutants into the air.

Geothermal energy is only avaiable in certain parts of the world. Another disadvantage of using geothermal energy is that in areas of the world where there is only dry heat underground, large quantities of freshwater are used to make steam. There may not be a lot of freshwater. People need water for drinking, cooking, and bathing.

Biomass Energy

Biomass is any material that comes from plants or microorganisms that were recently living. Plants create energy from the sun through photosynthesis . This energy is stored in the plants even after they die.

Trees, branches, scraps of bark, and recycled paper are common sources of biomass energy. Manure, garbage, and crops , such as corn, soy, and sugar cane, can also be used as biomass feedstocks .

We get energy from biomass by burning it. Wood chips, manure, and garbage are dried out and compressed into squares called “briquettes.” These briquettes are so dry that they do not absorb water. They can be stored and burned to create heat or generate electricity.

Biomass can also be converted into biofuel . Biofuels are mixed with regular gasoline and can be used to power cars and trucks. Biofuels release less harmful pollutants than pure gasoline.

Advantages and Disadvantages A major advantage of biomass is that it can be stored and then used when it is needed.

Growing crops for biofuels, however, requires large amounts of land and pesticides . Land could be used for food instead of biofuels. Some pesticides could pollute the air and water.

Biomass energy can also be a nonrenewable energy source. Biomass energy relies on biomass feedstocks—plants that are processed and burned to create electricity. Biomass feedstocks can include crops, such as corn or soy, as well as wood. If people do not replant biomass feedstocks as fast as they use them, biomass energy becomes a non-renewable energy source.

Hydroelectric Energy

Hydroelectric energy is made by flowing water. Most hydroelectric power plants are located on large dams , which control the flow of a river.

Dams block the river and create an artificial lake, or reservoir. A controlled amount of water is forced through tunnels in the dam. As water flows through the tunnels, it turns huge turbines and generates electricity.

Advantages and Disadvantages Hydroelectric energy is fairly inexpensive to harness. Dams do not need to be complex, and the resources to build them are not difficult to obtain. Rivers flow all over the world, so the energy source is available to millions of people.

Hydroelectric energy is also fairly reliable. Engineers control the flow of water through the dam, so the flow does not depend on the weather (the way solar and wind energies do).

However, hydroelectric power plants are damaging to the environment. When a river is dammed, it creates a large lake behind the dam. This lake (sometimes called a reservoir) drowns the original river habitat deep underwater. Sometimes, people build dams that can drown entire towns underwater. The people who live in the town or village must move to a new area.

Hydroelectric power plants don’t work for a very long time: Some can only supply power for 20 or 30 years. Silt , or dirt from a riverbed, builds up behind the dam and slows the flow of water.

Other Renewable Energy Sources

Scientists and engineers are constantly working to harness other renewable energy sources. Three of the most promising are tidal energy , wave energy , and algal (or algae) fuel.

Tidal energy harnesses the power of ocean tides to generate electricity. Some tidal energy projects use the moving tides to turn the blades of a turbine. Other projects use small dams to continually fill reservoirs at high tide and slowly release the water (and turn turbines) at low tide.

Wave energy harnesses waves from the ocean, lakes, or rivers. Some wave energy projects use the same equipment that tidal energy projects do—dams and standing turbines. Other wave energy projects float directly on waves. The water’s constant movement over and through these floating pieces of equipment turns turbines and creates electricity.

Algal fuel is a type of biomass energy that uses the unique chemicals in seaweed to create a clean and renewable biofuel. Algal fuel does not need the acres of cropland that other biofuel feedstocks do.

Renewable Nations

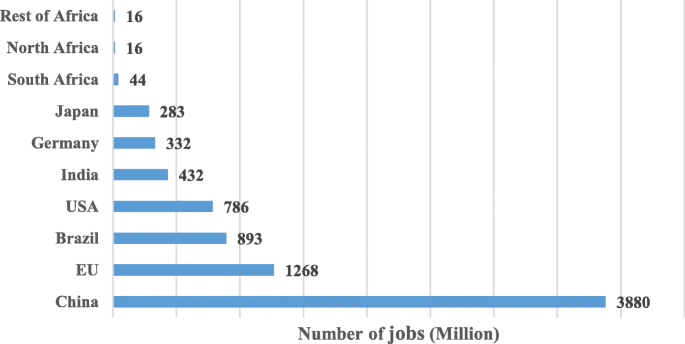

These nations (or groups of nations) produce the most energy using renewable resources. Many of them are also the leading producers of nonrenewable energy: China, European Union, United States, Brazil, and Canada

Articles & Profiles

Media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

June 21, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- News & Updates

The Future of Sustainable Energy

26 June, 2021

Share this on social media:

Building a sustainable energy future calls for leaps forward in both technology and policy leadership. State governments, major corporations and nations around the world have pledged to address the worsening climate crisis by transitioning to 100% renewable energy over the next few decades. Turning those statements of intention into a reality means undertaking unprecedented efforts and collaboration between disciplines ranging from environmental science to economics.

There are highly promising opportunities for green initiatives that could deliver a better future. However, making a lasting difference will require both new technology and experts who can help governments and organizations transition to more sustainable practices. These leaders will be needed to source renewables efficiently and create environmentally friendly policies, as well as educate consumers and policymakers. To maximize their impact, they must make decisions informed by the most advanced research in clean energy technology, economics, and finance.

Current Trends in Sustainability

The imperative to adopt renewable power solutions on a worldwide scale continues to grow even more urgent as the global average surface temperature hits historic highs and amplifies the danger from extreme weather events . In many regions, the average temperature has already increased by 1.5 degrees , and experts predict that additional warming could drive further heatwaves, droughts, severe hurricanes, wildfires, sea level rises, and even mass extinctions.

In addition, physicians warn that failure to respond to this dire situation could unleash novel diseases : Dr. Rexford Ahima and Dr. Arturo Casadevall of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine contributed to an article in the Journal of Clinical Investigation that explained how climate change could affect the human body’s ability to regulate its own temperature while bringing about infectious microbes that adapt to the warmer conditions.

World leaders have accepted that greenhouse gas emissions are a serious problem that must be addressed. Since the Paris Agreement was first adopted in December 2015, 197 nations have signed on to its framework for combating climate change and preventing the global temperature increase from reaching 2 degrees Celsius over preindustrial levels.

Corporate giants made their own commitments to become carbon neutral by funding offsets to reduce greenhouse gases and gradually transitioning into using 100% renewable energy. Google declared its operations carbon neutral in 2017 and has promised that all data centers and campuses will be carbon-free by 2030. Facebook stated that it would eliminate its carbon footprint in 2020 and expand that commitment to all the organization’s suppliers within 10 years. Amazon ordered 100,000 electric delivery vehicles and has promised that its sprawling logistics operations will arrive at net-zero emissions by 2040.

Despite these promising developments, many experts say that nations and businesses are still not changing fast enough. While carbon neutrality pledges are a step in the right direction, they don’t mean that organizations have actually stopped using fossil fuels . And despite the intentions expressed by Paris Agreement signatories, total annual carbon dioxide emissions reached a record high of 33.5 gigatons in 2018, led by China, the U.S., and India.

“The problem is that what we need to achieve is so daunting and taxes our resources so much that we end up with a situation that’s much, much worse than if we had focused our efforts,” Ferraro said.

Recent Breakthroughs in Renewable Power

An environmentally sustainable infrastructure requires innovations in transportation, industry, and utilities. Fortunately, researchers in the private and public sectors are laying the groundwork for an energy transformation that could make the renewable energy of the future more widely accessible and efficient.

Some of the most promising areas that have seen major developments in recent years include:

Driving Electric Vehicles Forward

The technical capabilities of electric cars are taking great strides, and the popularity of these vehicles is also growing among consumers. At Tesla’s September 22, 2020 Battery Day event, Elon Musk announced the company’s plans for new batteries that can be manufactured at a lower cost while offering greater range and increased power output .

The electric car market has seen continuing expansion in Europe even during the COVID-19 pandemic, thanks in large part to generous government subsidies. Market experts once predicted that it would take until 2025 for electric car prices to reach parity with gasoline-powered vehicles. However, growing sales and new battery technology could greatly speed up that timetable .

Cost-Effective Storage For Renewable Power

One of the biggest hurdles in the way of embracing 100% renewable energy has been the need to adjust supply based on demand. Utilities providers need efficient, cost-effective ways of storing solar and wind power so that electricity is available regardless of weather conditions. Most electricity storage currently takes place in pumped-storage hydropower plants, but these facilities require multiple reservoirs at different elevations.

Pumped thermal electricity storage is an inexpensive solution to get around both the geographic limitations of hydropower and high costs of batteries. This approach, which is currently being tested , uses a pump to convert electricity into heat so it can be stored in a material like gravel, water, or molten salts and kept in an insulated tank. A heat engine converts the heat back into electricity as necessary to meet demand.

Unlocking the Potential of Microgrids

Microgrids are another area of research that could prove invaluable to the future of power. These systems can operate autonomously from a traditional electrical grid, delivering electricity to homes and business even when there’s an outage. By using this approach with power sources like solar, wind, or biomass, microgrids can make renewable energy transmission more efficient.

Researchers in public policy and engineering are exploring how microgrids could serve to bring clean electricity to remote, rural areas . One early effort in the Netherlands found that communities could become 90% energy self-sufficient , and solar-powered microgrids have now also been employed in Indian villages. This technology has enormous potential to change the way we access electricity, but lowering costs is an essential step to bring about wider adoption and encourage residents to use the power for purposes beyond basic lighting and cooling.

Advancing the Future of Sustainable Energy

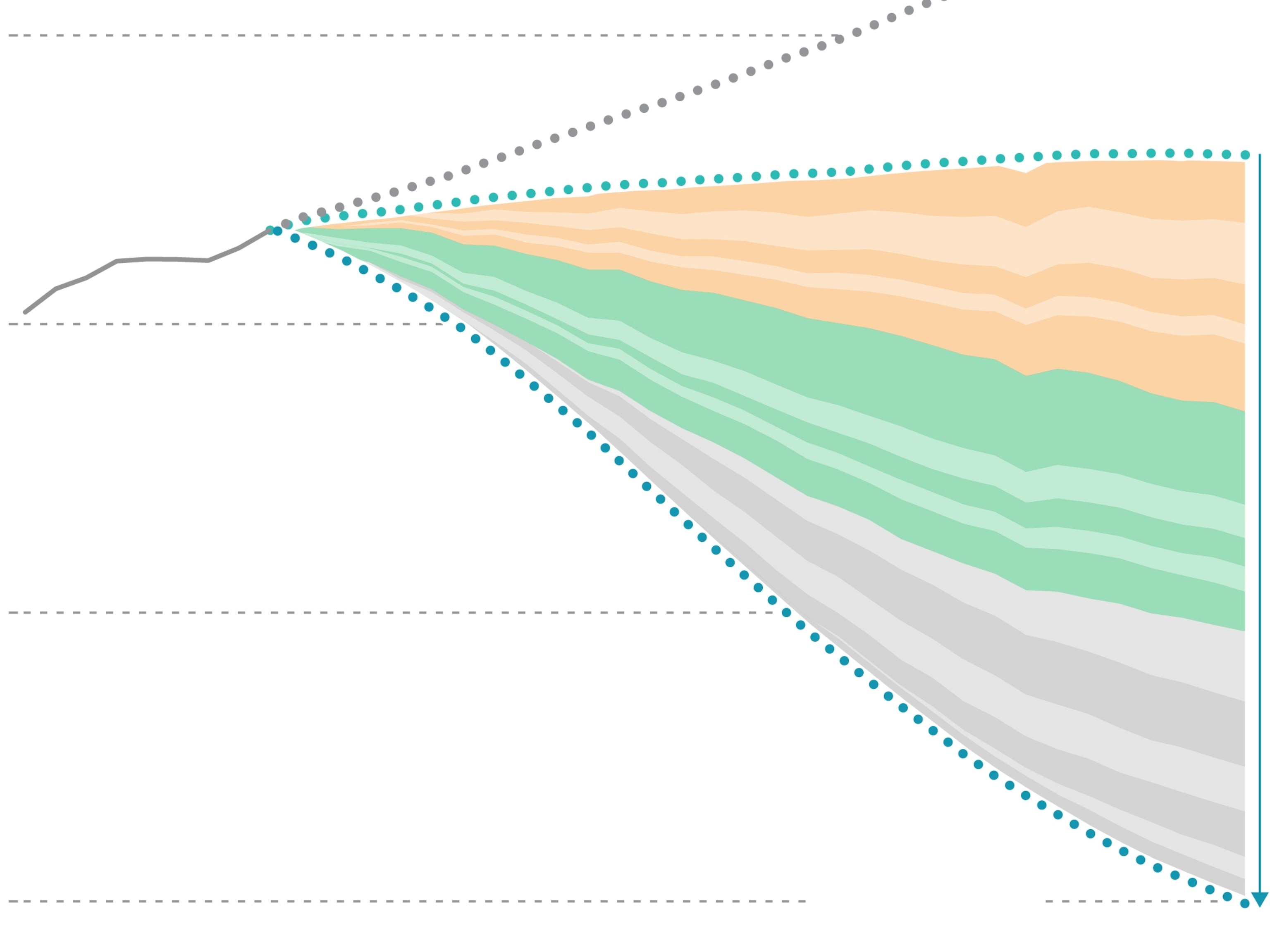

There’s still monumental work to be done in developing the next generation of renewable energy solutions as well as the policy framework to eliminate greenhouse gases from our atmosphere. An analysis from the International Energy Agency found that the technologies currently on the market can only get the world halfway to the reductions needed for net-zero emissions by 2050.

To make it the rest of the way, researchers and policymakers must still explore possibilities such as:

- Devise and implement large-scale carbon capture systems that store and use carbon dioxide without polluting the atmosphere

- Establish low-carbon electricity as the primary power source for everyday applications like powering vehicles and heat in buildings

- Grow the use of bioenergy harnessed from plants and algae for electricity, heat, transportation, and manufacturing

- Implement zero-emission hydrogen fuel cells as a way to power transportation and utilities

However, even revolutionary technology will not do the job alone. Ambitious goals for renewable energy solutions and long-term cuts in emissions also demand enhanced international cooperation, especially among the biggest polluters. That’s why Jonas Nahm of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies has focused much of his research on China’s sustainable energy efforts. He has also argued that the international community should recognize China’s pivotal role in any long-term plans for fighting climate change.

As both the leading emitter of carbon dioxide and the No. 1 producer of wind and solar energy, China is uniquely positioned to determine the future of sustainability initiatives. According to Nahm, the key to making collaboration with China work is understanding the complexities of the Chinese political and economic dynamics. Because of conflicting interests on the national and local levels, the world’s most populous nation continues to power its industries with coal even while President Xi Jinping advocates for fully embracing green alternatives.

China’s fraught position demonstrates that economics and diplomacy could prove to be just as important as technical ingenuity in creating a better future. International cooperation must guide a wide-ranging economic transformation that involves countries and organizations increasing their capacity for producing and storing renewable energy.

It will take strategic thinking and massive investment to realize a vision of a world where utilities produce 100% renewable power while rows of fully electric cars travel on smart highways. To meet the challenge of our generation, it’s more crucial than ever to develop leaders who understand how to apply the latest research to inform policy and who can take charge of globe-spanning sustainable energy initiatives .

About the MA in Sustainable Energy (online) Program at Johns Hopkins SAIS

Created by Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies faculty with input from industry experts and employers, the Master of Arts in Sustainable Energy (online) program is tailored for the demands of a rapidly evolving sector. As a top-11 global university, Johns Hopkins is uniquely positioned to equip graduates with the skills they need to confront global challenges in the transition to renewable energy.

The MA in Sustainable Energy curriculum is designed to build expertise in finance, economics, and policy. Courses from our faculty of highly experienced researchers and practitioners prepare graduates to excel in professional environments including government agencies, utility companies, energy trade organizations, global energy governance organizations, and more. Students in the Johns Hopkins SAIS benefit from industry connections, an engaged network of more than 230,000 alumni, and high-touch career services.

Request Information

To learn more about the MA in Sustainable Energy (online) and download a brochure , fill out the fields below, or call +1 410-648-2495 or toll-free at +1 888-513-5303 to talk with one of our admissions counselors.

Johns Hopkins University has engaged AllCampus to help support your educational journey. AllCampus will contact you shortly in response to your request for information. About AllCampus . Privacy Policy . You may opt out of receiving communications at any time.

* All Fields are Required. Your Privacy is Protected.

Connect with us

- Email: [email protected]

- Local Phone: +1 410-648-2495 (Local)

- Toll-Free Phone: +1 888-513-5303 (Toll-Free)

The round 6 application deadline is August 5, 2024. Apply Now

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What is solar energy?

- How is solar energy collected?

renewable energy

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration - Energy Kids - Energy Sources - Renewable

- Natural Resources Defense Council - Renewable Energy: The Clean Facts

- Energy.gov - Renewable Energy

- United Nations - What is renewable energy?

- World Nuclear Association - Renewable Energy and Electricity

- alternative energy - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- alternative energy - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Recent News

renewable energy , usable energy derived from replenishable sources such as the Sun ( solar energy ), wind ( wind power ), rivers ( hydroelectric power ), hot springs ( geothermal energy ), tides ( tidal power ), and biomass ( biofuels ).

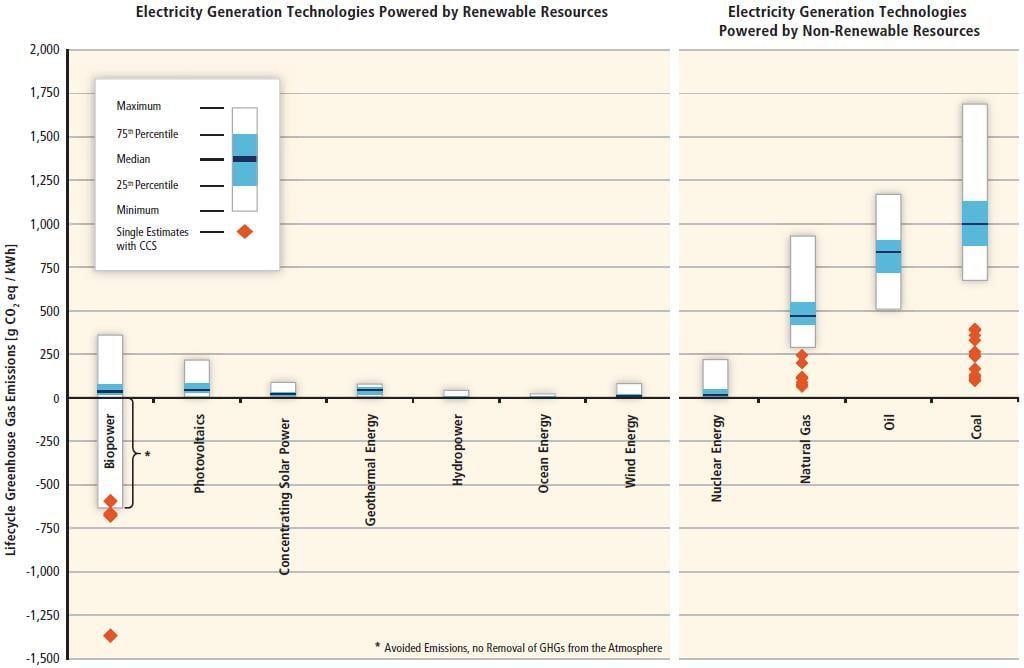

At the beginning of the 21st century, about 80 percent of the world’s energy supply was derived from fossil fuels such as coal , petroleum , and natural gas . Fossil fuels are finite resources; most estimates suggest that the proven reserves of oil are large enough to meet global demand at least until the middle of the 21st century. Fossil fuel combustion has a number of negative environmental consequences. Fossil-fueled power plants emit air pollutants such as sulfur dioxide , particulate matter , nitrogen oxides, and toxic chemicals (heavy metals: mercury , chromium , and arsenic ), and mobile sources, such as fossil-fueled vehicles, emit nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide , and particulate matter. Exposure to these pollutants can cause heart disease , asthma , and other human health problems. In addition, emissions from fossil fuel combustion are responsible for acid rain , which has led to the acidification of many lakes and consequent damage to aquatic life, leaf damage in many forests, and the production of smog in or near many urban areas. Furthermore, the burning of fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide (CO 2 ), one of the main greenhouse gases that cause global warming .

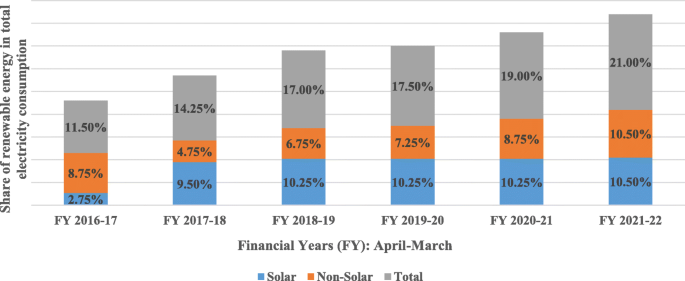

In contrast, renewable energy sources accounted for nearly 20 percent of global energy consumption at the beginning of the 21st century, largely from traditional uses of biomass such as wood for heating and cooking . By 2015 about 16 percent of the world’s total electricity came from large hydroelectric power plants, whereas other types of renewable energy (such as solar, wind, and geothermal) accounted for 6 percent of total electricity generation. Some energy analysts consider nuclear power to be a form of renewable energy because of its low carbon emissions; nuclear power generated 10.6 percent of the world’s electricity in 2015.

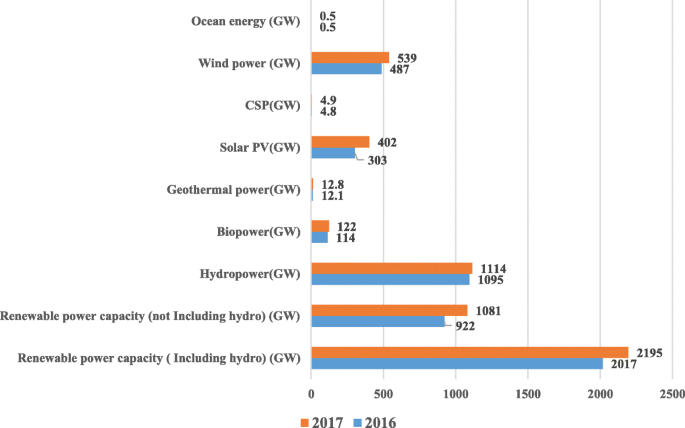

Growth in wind power exceeded 20 percent and photovoltaics grew at 30 percent annually in the 1990s, and renewable energy technologies continued to expand throughout the early 21st century. Between 2001 and 2017 world total installed wind power capacity increased by a factor of 22, growing from 23,900 to 539,581 megawatts. Photovoltaic capacity also expanded, increasing by 50 percent in 2016 alone. The European Union (EU), which produced an estimated 6.38 percent of its energy from renewable sources in 2005, adopted a goal in 2007 to raise that figure to 20 percent by 2020. By 2016 some 17 percent of the EU’s energy came from renewable sources. The goal also included plans to cut emissions of carbon dioxide by 20 percent and to ensure that 10 percent of all fuel consumption comes from biofuels . The EU was well on its way to achieving those targets by 2017. Between 1990 and 2016 the countries of the EU reduced carbon emissions by 23 percent and increased biofuel production to 5.5 percent of all fuels consumed in the region. In the United States numerous states have responded to concerns over climate change and reliance on imported fossil fuels by setting goals to increase renewable energy over time. For example, California required its major utility companies to produce 20 percent of their electricity from renewable sources by 2010, and by the end of that year California utilities were within 1 percent of the goal. In 2008 California increased this requirement to 33 percent by 2020, and in 2017 the state further increased its renewable-use target to 50 percent by 2030.

IEEE Account

- Change Username/Password

- Update Address

Purchase Details

- Payment Options

- Order History

- View Purchased Documents

Profile Information

- Communications Preferences

- Profession and Education

- Technical Interests

- US & Canada: +1 800 678 4333

- Worldwide: +1 732 981 0060

- Contact & Support

- About IEEE Xplore

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- Nondiscrimination Policy

- Privacy & Opting Out of Cookies

A not-for-profit organization, IEEE is the world's largest technical professional organization dedicated to advancing technology for the benefit of humanity. © Copyright 2024 IEEE - All rights reserved. Use of this web site signifies your agreement to the terms and conditions.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

In a World on Fire, Stop Burning Things

On the last day of February, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its most dire report yet. The Secretary-General of the United Nations, António Guterres, had, he said, “seen many scientific reports in my time, but nothing like this.” Setting aside diplomatic language, he described the document as “an atlas of human suffering and a damning indictment of failed climate leadership,” and added that “the world’s biggest polluters are guilty of arson of our only home.” Then, just a few hours later, at the opening of a rare emergency special session of the U.N. General Assembly, he catalogued the horrors of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine , and declared, “Enough is enough.” Citing Putin’s declaration of a nuclear alert , the war could, Guterres said, turn into an atomic conflict, “with potentially disastrous implications for us all.”

What unites these two crises is combustion. Burning fossil fuel has driven the temperature of the planet ever higher, melting most of the sea ice in the summer Arctic, bending the jet stream , and slowing the Gulf Stream. And selling fossil fuel has given Putin both the money to equip an army (oil and gas account for sixty per cent of Russia’s export earnings) and the power to intimidate Europe by threatening to turn off its supply. Fossil fuel has been the dominant factor on the planet for centuries, and so far nothing has been able to profoundly alter that. After Putin invaded, the American Petroleum Institute insisted that our best way out of the predicament was to pump more oil. The climate talks in Glasgow last fall, which John Kerry, the U.S. envoy, had called the “last best hope” for the Earth, provided mostly vague promises about going “net-zero by 2050”; it was a festival of obscurantism, euphemism, and greenwashing, which the young climate activist Greta Thunberg summed up as “blah, blah, blah.” Even people trying to pay attention can’t really keep track of what should be the most compelling battle in human history.

So let’s reframe the fight. Along with discussing carbon fees and green-energy tax credits, amid the momentary focus on disabling Russian banks and flattening the ruble, there’s a basic, underlying reality: the era of large-scale combustion has to come to a rapid close. If we understand that as the goal, we might be able to keep score, and be able to finally get somewhere. Last Tuesday, President Biden banned the importation of Russian oil. This year, we may need to compensate for that with American hydrocarbons, but, as a senior Administration official put it ,“the only way to eliminate Putin’s and every other producing country’s ability to use oil as an economic weapon is to reduce our dependency on oil.” As we are one of the largest oil-and-gas producers in the world, that is a remarkable statement. It’s a call for an end of fire.

We don’t know when or where humans started building fires; as with all things primordial there are disputes. But there is no question of the moment’s significance. Fire let us cook food, and cooked food delivers far more energy than raw; our brains grew even as our guts, with less processing work to do, shrank. Fire kept us warm, and human enterprise expanded to regions that were otherwise too cold. And, as we gathered around fires, we bonded in ways that set us on the path to forming societies. No wonder Darwin wrote that fire was “the greatest discovery ever made by man, excepting language.”

Darwin was writing in the years following the Industrial Revolution, as we learned how to turn coal into steam power, gas into light, and oil into locomotion, all by way of combustion. Our species depends on combustion; it made us human, and then it made us modern. But, having spent millennia learning to harness fire, and three centuries using it to fashion the world we know, we must spend the next years systematically eradicating it. Because, taken together, those blazes—the fires beneath the hoods of 1.4 billion vehicles and in the homes of billions more people, in giant power plants, and in the boilers of factories and the engines of airplanes ships—are more destructive than the most powerful volcanoes, dwarfing Krakatoa and Tambora. The smoke and smog from those engines and appliances directly kill nine million people a year, more deaths than those caused by war and terrorism, not to mention malaria and tuberculosis, together. (In 2020, fossil-fuel pollution killed three times as many people as COVID -19 did.) Those flames, of course, also spew invisible and odorless carbon dioxide at an unprecedented rate; that CO 2 is already rearranging the planet’s climate, threatening not only those of us who live on it now but all those who will come after us.

But here’s the good news, which makes this exercise more than merely rhetorical: rapid advances in clean-energy technology mean that all that destruction is no longer necessary. In the place of those fires we keep lit day and night, it’s possible for us to rely on the fact that there is a fire in the sky—a great ball of burning gas about ninety-three million miles away, whose energy can be collected in photovoltaic panels, and which differentially heats the Earth, driving winds whose energy can now be harnessed with great efficiency by turbines. The electricity they produce can warm and cool our homes, cook our food, and power our cars and bikes and buses. The sun burns, so we don’t need to.

Wind and solar power are not a replacement for everything, at least not yet. Three billion people still cook over fire daily, and will at least until sufficient electricity reaches them, and perhaps thereafter, since culture shifts slowly. Even then, flames will still burn—for birthday-cake candles, for barbecues, for joints (until you’ve figured out the dosing for edibles)—just as we still use bronze, though its age has long passed. And there are a few larger industries—intercontinental air travel, certain kinds of metallurgy such as steel production—that may require combustion, probably of hydrogen, for some time longer. But these are relatively small parts of the energy picture. And in time they, too, will likely be replaced by renewable electricity. (Electric-arc furnaces are already producing some kinds of steel, and Japanese researchers have just announced a battery so light that it might someday power passenger flights across oceans.) In fact, I can see only one sublime, long-term use for large-scale planned combustion, which I will get to. Mostly, our job as a species is clear: stop smoking.

As of 2022, this task is both possible and affordable. We have the technology necessary to move fast, and deploying it will save us money. Those are the first key ideas to internalize. They are new and counterintuitive, but a few people have been working to realize them for years, and their stories make clear the power of this moment.

When Mark Jacobson was growing up in northern California in the nineteen-seventies, he showed a gift for science, and also for tennis. He travelled for tournaments to Los Angeles and San Diego, where, he told me recently, he was shocked by how dirty the air was: “You’d get scratchy eyes, your throat would start hurting. You couldn’t see very far. I thought, Why should people live like this?” He eventually wound up at Stanford, first as an undergraduate and then, in the mid-nineteen-nineties, as a professor of civil and environmental engineering, by which time it was clear that visible air pollution was only part of the problem. It was understood that the unseen gas produced by combustion—carbon dioxide—posed an even more comprehensive threat.

To get at both problems, Jacobson analyzed data to see if an early-model wind turbine sold by General Electric could compete with coal. He worked out its capacity by calculating its efficiency at average wind speeds; a paper he wrote, published in the journal Science in 2001, showed that you “could get rid of sixty per cent of coal in the U.S. with a modest number of turbines.” It was, he said, “the shortest paper I’ve ever written—three-quarters of a page in the journal—and it got the most feedback, almost all from haters.” He ignored them; soon he had a graduate student mapping wind speeds around the world, and then he expanded his work to other sources of renewable energy. In 2009, he and Mark Delucchi, a research scientist at the University of California, published a paper suggesting that hydroelectric, wind, and solar energy could conceivably supply enough power to meet all the world’s energy needs. The conventional wisdom at the time was that renewables were unreliable, because the sun insists on setting each night and the wind can turn fickle. In 2015, Jacobson wrote a paper for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , showing that, on the contrary, wind and solar energy could keep the electric grid running. That paper won a prestigious prize from the editors of the journal, but it didn’t prevent more pushback—a team of twenty academics from around the country published a rebuttal, stating that “policy makers should treat with caution any visions of a rapid, reliable, and low-cost transition to entire energy systems that relies almost exclusively on wind, solar, and hydroelectric power.”

Time, however, is proving Jacobson correct: a few nations—including Iceland, Costa Rica, Namibia, and Norway—are already producing more than ninety per cent of their electricity from clean sources. When Jacobson began his work, wind turbines were small fans atop California ridgelines, whirligigs that looked more like toys than power sources. Now G.E. routinely erects windmills about three times as tall as the Statue of Liberty, and, in August, a Chinese firm announced a new model, whose blades will sweep an area the size of six soccer fields, with each turbine generating enough power for twenty thousand homes. (An added benefit: bigger turbines kill fewer birds than smaller ones, though, in any event, tall buildings, power lines, and cats are responsible for far more avian deaths.) In December, Jacobson’s Stanford team published an updated analysis , stating that we have ninety-five per cent of the technology required to produce a hundred per cent of America’s power needs from renewable energy by 2035, while keeping the electric grid secure and reliable.

Making clean technology affordable is the other half of the challenge, and here the news is similarly upbeat. In September, after almost fifteen years of work, a team of researchers at Oxford University released a paper that is currently under peer review but which, fifty years from now, people may look back on as a landmark step in addressing the climate crisis. The lead author of the report is Oxford’s Rupert Way; the research team was led by an American named Doyne (pronounced “ dough -en”) Farmer.

Farmer grew up in New Mexico, a precocious physicist and mathematician. His first venture, formed while he was a graduate student at U.C. Santa Cruz, was called Eudaemonic Enterprises, after Aristotle’s term for the condition of human flourishing. The goal was to beat roulette wheels. Farmer wore a shoe (now housed in a German museum) with a computer in its sole, and watched as a croupier tossed a ball into a wheel; noting the ball’s initial position and velocity, he tapped his toe to send the information to the computer, which performed quick calculations, giving him a chance to make a considered bet in the few seconds the casino allowed. This achievement led him to building algorithms to beat the stock market—a statistical-arbitrage technique that underpinned an enterprise he co-founded called the Prediction Company, which was eventually sold to the Swiss banking giant UBS. Happily, Farmer eventually turned his talents to something of greater social worth: developing a way to forecast rates of technological progress. The basis for this work was research published in 1936, when Theodore Wright, an executive at the Curtiss Aeroplane Company, had noted that every time the production of airplanes doubled, the cost of building them fell by twenty per cent. Farmer and his colleagues were intrigued by this “learning curve” (and its semiconductor-era variant, Moore’s Law ); if you could figure out which technologies fit on the curve, and which didn’t, you’d be able to forecast the future.

“It was about fifteen years ago,” Farmer told me, in December. “I was at the Santa Fe Institute, and the head of the National Renewable Energy Lab came down. He said, ‘You guys are complex-systems people. Help us think outside the box—what are we missing?’ I had a Transylvanian postdoctoral fellow at the time, and he started putting together a database—he had high-school kids working on it, kids from St. John’s College in Santa Fe, anyone. And, as we looked at it, we saw this point about the improvement trends being persistent over time.” The first practical application of solar electricity was on the Vanguard I satellite, in 1958—practical if you had the budget of the space program. Yet the cost had been falling steadily, as people improved each generation of the technology—not because of one particular breakthrough or a single visionary entrepreneur but because of constant incremental improvement. Every time the number of solar panels manufactured doubles, the price drops another thirty per cent, which means that it’s currently falling about ten per cent every year.

But—and here’s the key—not all technologies follow this curve. “We looked at the price of coal over a hundred and forty years,” Farmer said. “Mines are much more sophisticated, the technology for locating new deposits is much better. But prices have not come down.” A likely explanation is that we got to all the easy stuff first: oil once bubbled up out of the ground; now we have to drill deep beneath the ocean for it. Whatever the reason, by 2013, the cost of a kilowatt-hour of solar energy had fallen by more than ninety-nine per cent since it was first used on the Vanguard I. Meanwhile, the price of coal has remained about the same. It was cheap to start, but it hasn’t gotten cheaper.

The more data sets that Farmer’s team members included, the more robust numbers they got, and by the autumn of 2021 they were ready to publish their findings. They found that the price trajectories of fossil fuels and renewables are already crossing. Renewable energy is now cheaper than fossil fuel, and becoming more so. So a “decisive transition” to renewable energy, they reported, would save the world twenty-six trillion dollars in energy costs in the coming decades.

This is precisely the opposite of how we have viewed energy transition. It has long been seen as an economically terrifying undertaking: if we had to transition to avoid calamity (and obviously we did), we should go as slowly as possible. Bill Gates, just last year, wrote a book, arguing that consumers would need to pay a “green premium” for clean energy because it would be more expensive. But Emily Grubert, a Georgia Tech engineer who now works for the Department of Energy, has recently shown that it could cost less to replace every coal plant in the country with renewables than to simply maintain the existing coal plants. You could call it a “green discount.”

The constant price drops mean, Farmer said, that we might still be able to move quickly enough to meet the target set in the 2016 Paris climate agreement of trying to limit temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. “One point five is going to suck,” he said. “But it sure beats three. We just need to put our money down and do it. So many people are pessimistic and despairing, and we need to turn that around.”

Numbers like Farmer’s make people who’ve been working in this field for years absolutely giddy. At COP 26, I retreated one day from Glasgow’s giant convention center to the relative quiet of the city’s university district for a pizza with a man named Kingsmill Bond. Bond is an Englishman and a former investment professional, and he looks the part: lean, in a bespoke suit, with a good haircut. His daughter, he said, was that day sitting her exams for Cambridge, the university he’d attended before a career at Citi and Deutsche Bank that had taken him to Hong Kong and Moscow. He’d quit some years ago, taking a cut in pay that he’s too modest to disclose. He’d worked first for the Carbon Tracker Initiative, in London, and now the Rocky Mountain Institute, based in Colorado, two groups working on energy transition.

He drew on a napkin excitedly, expounding on the numbers in the Oxford report. We would have to build out the electric grid to carry all the new power, and install millions of E.V. chargers, and so on, down a long list—amounting to maybe a trillion dollars in extra capital expenditure a year over the next two or three decades. But, in return, Bond said, we get an economic gift: “We save about two trillion dollars a year on fossil-fuel rents. Forever.” Fossil-fuel rent is what economists call the money that goes from consumers to those who control the hydrocarbon supply. Saudi Arabia can pull oil out of the ground for less than ten dollars a barrel and sell it at fifty or seventy-five dollars a barrel (or, during the emergency caused by Putin’s war, more than a hundred dollars); the difference is the rent they command. Bond insists that higher projections for the cost of the energy transition—a recent analysis from the consulting firm McKinsey predicted that it would cost trillions more than Farmer’s team did—ignore these rents, and also assume that, before long, renewable energy will veer from the steeply falling cost curve. Even if you’re pessimistic about how much it will cost to make the change, though, it’s clear that it would be far less expensive than not moving fast—that’s measured in hundreds of trillions of dollars but also in millions of lives and whatever value we place on maintaining an orderly civilization.

The new numbers turn the economic logic we’re used to upside down. A few years ago, at a petroleum-industry conference in Texas, the Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, said something both terrible and true: that “no country would find a hundred and seventy-three billion barrels of oil in the ground and leave them there.” He was referring to Alberta’s tar sands, where a third of Canada’s natural gas is used to heat the oil trapped in the soil sufficiently to get it to flow to the surface and separate it from the sand. Just extracting the oil would put Canada over its share of the carbon budget set in Paris, and actually burning it would heat the planet nearly half a degree Celsius and use up about a third of the total remaining budget. (And Canadians account for only about one half of one per cent of the world’s population.)

Even on purely economic terms, such logic makes less sense with each passing quarter. That’s especially true for the eighty per cent of people in the world who live in countries that must import fossil fuels—for them it’s all cost and no gain. Even for petrostates, however, the spreadsheet is increasingly difficult to rationalize. Bond supplied some numbers: Canada has fossil-fuel reserves totalling a hundred and sixty-seven petawatt hours, which is a lot. (A petawatt is a quadrillion watts.) But, he said, it has potential renewable energy from wind and solar power alone of seventy-one petawatt hours a year . A reasonable question to ask Trudeau would be: What kind of country finds a windfall like that and simply leaves it in the sky?

Making the energy transition won’t be easy, of course. Because we’ve been burning fuel to power our economies for more than two hundred years, we have in place long and robust supply chains and deep technical expertise geared to a combustion economy. “We’ve tried to think about possible infrastructure walls that might get in the way,” Farmer said. That’s a virtue of this kind of learning-curve analysis: if renewable energy has overcome obstacles in the past to keep dropping in price, it will probably be able to do so again. A few years ago, for instance, a number of reports said that the windmill business might crash because it was running short of the balsa wood used in turbine blades. But, within a year of the shortages emerging, many of the big windmill makers had started substituting a synthetic foam.

Now the focus is on minerals, such as cobalt, that are used in solar panels and batteries. Late last year, the Times published a long investigation of the success that China has had in cornering the world’s supply of the metal, which is found most abundantly in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Brian Menell, the C.E.O. of TechMet, a supplier of cobalt and other specialty metals, told me, “We run the risk that in five years, the factories for E.V.s will be sitting half idle, because those companies—the Fords and General Motors and Teslas and VWs—will not be able to secure the feedstock to maintain the capacity they’re building now.” But the fact that the Fords and G.M.s are in the hunt means that the political weight for what Menell calls a “massive and coördinated effort by government and end users” is likely to develop. Humans are good at solving the kind of dilemmas represented by scarcity. A Ford spokesman told the Times that the company is learning to recycle cobalt and to develop substitutes, adding, “We do not see cobalt as a constraining issue.”

Harder to solve may be the human-rights challenges that come with new mining efforts, such as the use of so-called “artisanal” cobalt mining, in which impoverished workers pry the metal from the ground with spades, or the plan to build a lithium mine on a site in Nevada that is sacred to Indigenous peoples. But, as we work to tackle those problems, it’s worth remembering that a transition to renewable energy would, by some estimates, reduce the total global mining burden by as much as eighty per cent, because so much of what we dig up today is burned (and then we have to go dig up some more). You dig up lithium once, and put it to use for decades in a solar panel or battery. In fact, a switch to renewable energy will reduce the load on all kinds of systems. At the moment, roughly forty per cent of the cargo carried by ocean-going ships is coal, gas, oil, and wood pellets—a never-ending stream of vessels crammed full of stuff to burn. You need a ship to carry a wind turbine blade, too, if it’s coming from across the sea, but you only need it once. A solar panel or a windmill, once erected, stands for a quarter of a century or longer. The U.S. military is the world’s largest single consumer of fossil fuels, but seventy per cent of its logistical “lift capacity” is devoted solely to transporting the fossil fuels used to keep the military machine running.

Raw materials aren’t the only possible pinch point. We’re also short of some kinds of expertise. Saul Griffith is perhaps the world’s leading apostle of electrification. (His 2021 book is called “ Electrify .”) An Australian by birth, he has spent recent years in Silicon Valley, rallying entrepreneurs to the project of installing E.V. chargers, air-source heat pumps, induction cooktops, and the like. He can show that they save homeowners, landlords, and businesses money; he’s also worked out the numbers to show that banks can prosper by extending, in essence, mortgages for these improvements. But he told me that, to stay within the 1.5 degree Celsius range, “America is going to need a million more electricians this decade.” That’s not impossible . Working as an electrician is a good job, and community colleges and apprenticeship programs could train many more people to become one. But, as with the rest of the transition, it’s going to take leadership and coördination to make it happen.

Change on this scale would be difficult even if everyone was working in good faith, and not everyone is. So far, for instance, the climate provisions of the Build Back Better Act, which would help provide, among many other things, training for renewable-energy installers, have been blocked not just by the oil-dominated G.O.P. but by Joe Manchin , the Democrat who received more fossil-fuel donations in the past election cycle than anyone else in the Senate. The thirty-year history of the global-warming fight is largely a story of the efforts by the fossil-fuel industry to deny the need for change, or, more recently, to insist that it must come slowly.

The fossil-fuel industry wants to be able to keep burning something. That way, it can keep both its infrastructure and its business model usefully employed. It’s like an industry of rational pyromania. A decade or so ago, the thing it wanted to burn next was natural gas. Since it produces less carbon dioxide than coal does, it was billed as the “bridge fuel” that would get us to renewables. The logic seemed sound. But researchers, led by Bob Howarth, at Cornell University, found that producing large quantities of natural gas released large quantities of methane into the atmosphere. And methane (CH 4 ) is, like CO 2 , a potent heat-trapping gas, so it’s become clear that natural gas is a bridge fuel to nowhere—clear, that is, to everyone but the industry. The head of a big gas firm told a conference in Texas last week that he thought the domestic gas industry could be producing for the next hundred years.

Other parts of the industry want to go further back in time and burn wood; the European Union and the United States officially class “biomass burning” as carbon neutral. The city of Burlington, in my home state of Vermont, claims to source all its energy from renewables, but much of its electricity comes from a plant that burns trees. Again, the logic originally seemed sound: if you cut a tree, another grows in its place, and it will eventually soak up the carbon dioxide emitted from that burning the first tree. But, again, “eventually” is the problem . Burning wood is highly inefficient, and so it releases a huge pulse of carbon right now , when the world’s climate system is most vulnerable. Trees that grow back in a few generations’ time will come too late to save the ice caps. The world’s largest wood-burning plant is in England, run by a company called Drax; the plant used to burn coal, and it does scarcely less damage now than it did then. In January, news came that Enviva, a company based in Maryland that is the largest producer of wood pellets in the world, plans to double its output.

Or consider the huge sums of money in the bipartisan infrastructure bill passed last year, which will support another technology called carbon capture. This involves fitting power plants with enough filters and pipes so that they can go on burning coal or gas, but capture the CO 2 that pours out of the smokestacks and pipe it safely away—into an old salt mine, perhaps. (Or, ironically, into a depleted oil well, where it may be used to push more crude to the surface.) So far, these carbon-capture schemes don’t really work—but, even if they did, why spend the money to outfit systems with pipes and filters when solar power is already cheaper than coal power? We will have to remove some of the carbon in the atmosphere, and new generations of direct-air-capture machines may someday play a role, if their cost drops quickly. (They use chemicals to filter carbon straight from the ambient air; think of them as artificial trees.) But using this technology to lengthen the lifespan of coal-fired power plants is just one more gift to a politically connected industry.

Increasingly, the fossil-fuel industry is turning toward hydrogen as an out. Hydrogen does burn cleanly, without contributing to global warming, but the industry likes hydrogen because one way to produce it is by burning natural gas. And, as Howarth and Jacobson demonstrated in a recent paper, even if you combine burning that gas with expensive carbon capture, the methane that leaks from the frack wells is enough to render the whole process ruinous environmentally, and it makes no sense economically without huge subsidies.

There is another way to produce hydrogen, and, in time, it will almost certainly fuel the last big artificial fires on our planet. Through electrolysis, hydrogen can be separated from oxygen in water. And if the electricity used in the process is renewably produced then this “green hydrogen” would allow countries such as Japan, Singapore, and Korea, which may struggle to find enough space in their landscapes for renewable-energy generation, to power their grids. The Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest, the founder of the Fortescue Metals Group, is proposing to use solar power to produce green hydrogen that he can then ship to those countries. In January, Mukesh Ambani, the head of Reliance Industries and the richest man in India, announced plans to spend seventy-five billion dollars on the technology. Airbus recently predicted that green hydrogen could fuel its long-haul planes by 2035. And the good news—though Doyne Farmer cautions that the data sets are still pretty scanty—is that the electrolyzers which use solar energy to produce hydrogen seem to be on the same downward cost curve as solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries.

The fossil-fuel industry can be relied on to fight these shifts. Last autumn, a utility company in Oklahoma announced that it would charge fourteen hundred dollars to disconnect residential gas lines and move home stoves and furnaces to electricity. Within days, other utilities followed suit. That’s why the climate movement is increasingly taking on the banks that make loans for the expansion of fossil-fuel infrastructure. Last year, the International Energy Agency said that such expansion needed to end immediately if we are to meet the Paris targets, yet the world’s biggest banks, while making noises about “net zero by 2050,” continue to lend to new pipelines and wells. The issue came to the fore earlier this year, when Joe Biden nominated Sarah Bloom Raskin to the position of vice-chair for supervision at the Federal Reserve. “There is opportunity in pre-emptive, early and bold actions by federal economic policy makers looking to avoid catastrophe,” Raskin wrote in 2020. And it’s why certain lawmakers mobilized to stop her nomination . Senator Patrick Toomey, of Pennsylvania, who was the Senate’s sixth-biggest recipient of oil-and-gas contributions during his last campaign, in 2016 (he is not running for reëlection this year), said that Raskin “has specifically called for the Fed to pressure banks to choke off credit to traditional energy companies.” She’s tried, in other words, to extinguish the flames a little—and on Monday, for her pains, Manchin effectively derailed her nomination, saying that he would vote against her, because she “failed to satisfactorily address my concerns about the critical importance of financing an all-of-the-above energy policy.” On Tuesday, she withdrew her nomination .

The shift away from combustion is large and novel enough that it bumps up against everyone’s prior assumptions—environmentalists’, too. The fight against nuclear power, for example, was an early mainstay of the green movement, because it was easy to see that if something went wrong it could go badly wrong. I applauded, more than a decade ago, when the Vermont legislature voted to close the state’s old nuclear plant at the end of its working life, but I wouldn’t today. Indeed, for some years I’ve argued that existing nuclear reactors that can still be run with any margin of safety probably should be, as we’re making the transition—the spent fuel they produce is an evil inheritance for our descendants, but it’s not as dangerous as an overheated Earth, even if the scenes of Russian troops shelling nuclear plants added to the sense of horror enveloping the planet these past weeks. Yet the rapidly falling cost of renewables also indicates why new nuclear plants will have a hard time finding backers; it’s evaporating nuclear power’s one big advantage—that it’s always on. Farmer’s Oxford team ran the numbers. “If the cost of coal is flat, and the cost of solar is plummeting, nuclear is the rare technology whose cost is going up,” he said. Advocates will argue that this is because safety fears have driven up the cost of construction. “But the only place on Earth where you can find the cost of nuclear coming down is Korea,” Farmer said. “Even there, the rate of decline is one per cent a year. Compared to ten per cent for renewables, that’s not enough to matter.”

Accepting nuclear power for a while longer is not the only place environmentalists will need to bend. A reason I supported shutting down Vermont’s nuclear plant was because campaigners had promised that its output would be replaced with renewable energy. In the years that followed, though, advocates of scenery, wildlife, and forests managed to put the state’s mountaintops off limits to wind turbines. More recently, the state’s public-utility commission blocked construction of an eight-acre solar farm on aesthetic grounds. Those of us who live in and love rural areas have to accept that some of that landscape will be needed to produce energy. Not all of it, or even most of it—Jacobson’s latest numbers show that renewable power actually uses less land than fossil fuels, which require drilling fifty thousand new holes every year in North America alone. But we do need to see our landscape differently—as Ezra Klein wrote this week in the Times , “to conserve anything close to the climate we’ve had, we need to build as we’ve never built before.”

Corn fields, for instance, are a classic American sight, but they’re also just solar-energy collectors of another sort. (And ones requiring annual applications of nitrogen, which eventually washes into lakes and rivers, causing big algae blooms.) More than half the corn grown in Iowa actually ends up as ethanol in the tanks of cars and trucks—in other words, those fields are already growing fuel, just inefficiently. Because solar panels are far more efficient than photosynthesis, and because E.V.s are far more efficient than cars with gas engines, Jacobson’s data show that, by switching from ethanol to solar, you could produce eighty times the amount of automobile mileage using an equivalent area of land. And the transition could bring some advantages: the market for electrons is predictable, so solar panels can provide a fairly stable income for farmers, some of whom are learning to grow shade-tolerant crops or to graze animals around and beneath them.

Another concession will strike many environmentalists more deeply even than accepting a degraded landscape, and that’s the notion that reckoning with the climate crisis would force wholesale changes in the way that people live their lives. Remember, the long-held assumption was that renewable energy was going to be expensive and limited in supply. So, it was thought, this would move us in the direction of simpler, less energy-intensive ways of life, something that many of us welcomed, in part because there are deep environmental challenges that go beyond carbon and climate. Cheap new energy technologies may let us evade some of those more profound changes. Whenever I write about the rise of E.V.s, Twitter responds that we’d be better off riding bikes and electric buses. In many ways we would be, and some cities are thankfully starting to build extensive bike paths and rapid-transit lanes for electric buses. But, as of 2017, just two per cent of passenger miles in this country come from public transportation. Bike commuting has doubled in the past two decades—to about one per cent of the total. We could (and should) quintuple the number of people riding bikes and buses, and even then we’d still need to replace tens of millions of cars with E.V.s to meet the targets in the time the scientists have set to meet them. That time is the crucial variable. As hard as it will be to rewire the planet’s energy system by decade’s end, I think it would be harder—impossible, in fact—to sufficiently rewire social expectations, consumer preferences, and settlement patterns in that short stretch.

So one way to look at the work that must be done with the tools we have at hand is as triage. If we do it quickly, we will open up more possibilities for the generations to come. Just one example: Farmer says that it’s possible to see the cost of nuclear-fusion reactors, as opposed to the current fission reactors, starting to come steeply down the cost curve—and to imagine that a within a generation or two people may be taking solar panels off farm fields, because fusion (which is essentially the physics of the sun brought to Earth) may be providing all the power we need. If we make it through the bottleneck of the next decade, much may be possible.

There is one ethical element of the energy transition that we can’t set aside: the climate crisis is deeply unfair—by and large, the less you did to cause it, the harder and faster it hits you—but in the course of trying to fix it we do have an opportunity to also remedy some of that unfairness. For Americans, the best part of the Build Back Better bill may be that it tries to target significant parts of its aid to communities hardest hit by poverty and environmental damage, a residue of the Green New Deal that is its parent. And advocates are already pressing to insure that at least some of the new technology is owned by local communities—by churches and local development agencies, not by the solar-era equivalents of Koch Industries or Exxon.

Advocates are also calling for some of the first investments in green transformations to happen in public-housing projects, on reservations, and in public schools serving low-income students. There can be some impatience from environmentalists who worry that such considerations might slow down the transition. But, as Naomi Klein recently told me, “The hard truth is that environmentalists can’t win the emission-reduction fight on our own. Winning will take sweeping alliances beyond the self-identified green bubble—with trade unions, housing-rights advocates, racial-justice organizers, teachers, transit workers, nurses, artists, and more. But, to build that kind of coalition, climate action needs to hold out the promise of making daily life better for the people who are most neglected right away—not far off in the future. Green, affordable homes and water that is safe to drink is something people will fight for a hell of a lot harder than carbon pricing.”

These are principles that must apply around the world, for basic fairness and because solving the climate crisis in just the U.S. would be the most pyrrhic of victories. (They don’t call it “global warming” for nothing.) In Glasgow, I sat down with Mohamed Nasheed, the former President of the Maldives and the current speaker of the People’s Majlis, the nation’s legislative body. He has been at the forefront of climate action for decades, because the highest land in his country, an archipelago that stretches across the equator in the Indian Ocean, is just a few metres above sea level. At COP 26, he was representing the Climate Vulnerable Forum, a consortium of fifty-five of the nations with the most to lose as temperatures rise. As he noted, poor countries have gone deeply into debt trying to deal with the effects of climate change. If they need to move an airport or shore up seawalls, or recover from a devastating hurricane or record rainfall, borrowing may be their only recourse. And borrowing gets harder, in part, because the climate risks mean that lenders demand more. The climate premium on loans may approach ten per cent, Nasheed said; some nations are already spending twenty per cent of their budgets just paying interest. He suggested that it might be time for a debt strike by poor nations.

The rapid fall in renewable-energy prices makes it more possible to imagine the rest of the world chipping in. So far, though, the rich countries haven’t even come up with the climate funds they promised the Global South more than a decade ago, much less any compensation for the ongoing damage that they have done the most to cause. (All of sub-Saharan Africa is responsible for less than two per cent of the carbon emissions currently heating the earth; the United States is responsible for twenty-five per cent.)

Tom Athanasiou’s Berkeley-based organization EcoEquity, as part of the Climate Equity Reference Project, has done the most detailed analyses of who owes what in the climate fight. He found that the U.S. would have to cut its emissions a hundred and seventy-five per cent to make up for the damage it’s already caused—a statistical impossibility. Therefore, the only way it can meet that burden is to help the rest of the world transition to clean energy, and to help bear the costs that global warming has already produced. As Athanasiou put it, “The pressing work of decarbonization is only going to be embraced by the people of the Global South if it comes as part of a package that includes adaptation aid and disaster relief.”

I said at the start that there is one sublime exception to the rule that we should be dousing fires, and that is the use of flame to control flame, and to manage land—a skill developed over many millennia by the original inhabitants of much of the world. Of all the fires burning on Earth, none are more terrifying than the conflagrations that light the arid West, the Mediterranean, the eucalyptus forests of Australia, and the boreal woods of Siberia and the Canadian north. By last summer, blazes in Oregon and Washington and British Columbia were fouling the air across the continent in New York and New England. Smoke from fires in the Russian far north choked the sky above the North Pole. For people in these regions, fire has become a scary psychological companion during the hot and dry months—and those months stretch out longer each year. The San Francisco Chronicle recently asked whether parts of California, once the nation’s idyll, were now effectively uninhabitable. In Siberia, even last winter’s icy cold was not enough to blot out the blazes; researchers reported “zombie fires” smoking and smoldering beneath feet of snow. There’s no question that the climate crisis is driving these great blazes—and also being driven by them, since they put huge clouds of carbon into the air.

There’s also little question, at least in the West, that the fires, though sparked by our new climate, feed on an accumulation of fuel left there by a century of a strict policy which treated any fire as a threat to be extinguished immediately. That policy ignored millennia of Indigenous experience using fire as a tool, an experience now suddenly in great demand. Indigenous people around the world have been at the forefront of the climate movement, and they have often been skilled early adopters of renewable energy. But they have also, in the past, been able to use fire to fight fire: to burn when the risk is low, in an effort to manage landscapes for safety and for productivity.

Frank Lake, a descendant of the Karuk tribe indigenous to what is now northern California, works as a research ecologist at the U.S. Forest Service, and he is helping to recover this old and useful technology. He described a controlled burn in the autumn of 2015 near his house on the Klamath River. “I have legacy acorn trees on my property,” he said—meaning the great oaks that provided food for tribal people in ages past—but those trees were hemmed in by fast-growing shrubs. “So we had twenty-something fire personnel there that day, and they had their equipment, and they laid hose. And I gave the operational briefing. I said, ‘We’re going to be burning today to reduce hazardous fuels. And also so we can gather acorns more easily, without the undergrowth, and the pests attacking the trees.’ My wife was there and my five-year-old son and my three-year-old daughter. And I lit a branch from a lightning-struck sugar pine—it conveys its medicine from the lightning—and with that I lit everyone’s drip torches, and then they went to work burning. My son got to walk hand-in-hand down the fire line with the burn boss.”

Lake’s work at the Forest Service involves helping tribes burn again. It’s not always easy; some have been so decimated by the colonial experience that they’ve lost their traditions. “Maybe they have two or three generations that haven’t been allowed to burn,” he said. There are important pockets of residual knowledge, often among elders, but they can be reluctant to share that knowledge with others, Lake told me, “fearful that it will be co-opted and that they’ll be kept out of the leadership and decision-making.” But, for half a decade, the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network—organized by various tribes, the Nature Conservancy, and government agencies, including the Forest Service—has slowly been expanding across the country. There are outposts in Oregon, Minnesota, New Mexico, and in other parts of the world. Lake has travelled to Australia to learn from aboriginal practitioners. “It’s family-based burning. The kids get a Bic lighter and burn a little patch of eucalyptus. The teen-agers a bigger area, adults much bigger swaths. I just saw it all unfold.” As that knowledge and confidence is recovered, it’s possible to imagine a world in which we’ve turned off most of the man-made fires, and Indigenous people teach the rest of us to use fire as the important force it was when we first discovered it.

Amy Cardinal Christianson, who works for the Canadian equivalent of the Forest Service, is a member of the Métis Nation. Her family kept trapping lines near Fort McMurray, in northern Alberta, but left them for the city because the development of the vast tar-sands complex overwhelmed the landscape. (That’s the hundred and seventy-three billion barrels that Justin Trudeau says no country would leave in the ground—a pool of carbon so vast the climate scientist James Hansen said that pumping it from the ground would mean “game over for the climate.”) The industrial fires it stoked have helped heat the Earth, and one result was a truly terrifying forest fire that overtook Fort McMurray in 2016, after a stretch of unseasonably high temperatures. The blaze forced the evacuation of eighty-eight thousand people, and became the costliest disaster in Canadian history.

“What we’re seeing now is bad fire,” Christianson said. “When we talk about returning fire to the landscape, we’re talking about good fire. I heard an elder describe it once as fire you could walk next to, fire of a low intensity.” Fire that builds a mosaic of landscapes that, in turn, act as natural firebreaks against devastating blazes; fire that opens meadows where wildlife can flourish. “Fire is a kind of medicine for the land. And it lets you carry out your culture—like, why you are in the world, basically.”

New Yorker Favorites

The hottest restaurant in France is an all-you-can-eat buffet .

How to die in good health .

Was Machiavelli misunderstood ?

A heat shield for the most important ice on Earth .

A major Black novelist made a remarkable début. Why did he disappear ?

Andy Warhol obsessively documented his life, but he also lied constantly, almost recreationally .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Essay on Renewable Energy

Introduction to Renewable Energy

In the quest for a sustainable and environmentally conscious future, adopting renewable energy has emerged as a pivotal solution to mitigate the challenges posed by traditional fossil fuels. Take, for instance, the remarkable growth of solar power in countries like Germany, where the “Energiewende” policy has catapulted them to the forefront of green energy innovation. This transformative journey showcases the potential of harnessing solar energy as an alternative and a cornerstone for economic prosperity, reduced carbon emissions, and heightened energy security. As we delve into the world of renewable energy, it becomes evident that these innovations are key to shaping a cleaner, more resilient global energy landscape.

Importance of Transitioning to Renewable Sources

A sustainable future and resolving numerous global issues depend heavily on the switch to renewable energy sources. This shift is crucial for several reasons:

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

- Environmental Preservation: Fossil fuel combustion contributes significantly to air and water pollution and climate change. Transitioning to renewables reduces greenhouse gas emissions, mitigates environmental degradation, and helps preserve ecosystems.

- Climate Change Mitigation: Renewable energy is a key player in mitigating climate change . Reducing greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide, is crucial to prevent catastrophic outcomes such as extreme weather events and rising sea levels.

- Energy Security: Wind and solar power, as renewable energy sources, provide a diverse and decentralized energy supply. This reduces dependence on finite and geopolitically sensitive fossil fuel reserves, enhancing energy security and resilience.

- Economic Opportunities: The renewable energy sector fosters job creation and economic growth. Investments in clean energy technologies stimulate innovation, create employment opportunities, and contribute to developing a robust and sustainable economy.