- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Medical Research Paper

Last Updated: August 12, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Chris M. Matsko, MD . Dr. Chris M. Matsko is a retired physician based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. With over 25 years of medical research experience, Dr. Matsko was awarded the Pittsburgh Cornell University Leadership Award for Excellence. He holds a BS in Nutritional Science from Cornell University and an MD from the Temple University School of Medicine in 2007. Dr. Matsko earned a Research Writing Certification from the American Medical Writers Association (AMWA) in 2016 and a Medical Writing & Editing Certification from the University of Chicago in 2017. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 89% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 204,996 times.

Writing a medical research paper is similar to writing other research papers in that you want to use reliable sources, write in a clear and organized style, and offer a strong argument for all conclusions you present. In some cases the research you discuss will be data you have actually collected to answer your research questions. Understanding proper formatting, citations, and style will help you write and informative and respected paper.

Researching Your Paper

- Pick something that really interests you to make the research more fun.

- Choose a topic that has unanswered questions and propose solutions.

- Quantitative studies consist of original research performed by the writer. These research papers will need to include sections like Hypothesis (or Research Question), Previous Findings, Method, Limitations, Results, Discussion, and Application.

- Synthesis papers review the research already published and analyze it. They find weaknesses and strengths in the research, apply it to a specific situation, and then indicate a direction for future research.

- Keep track of your sources. Write down all publication information necessary for citation: author, title of article, title of book or journal, publisher, edition, date published, volume number, issue number, page number, and anything else pertaining to your source. A program like Endnote can help you keep track of your sources.

- Take detailed notes as you read. Paraphrase information in your own words or if you copy directly from the article or book, indicate that these are direct quotes by using quotation marks to prevent plagiarism.

- Be sure to keep all of your notes with the correct source.

- Your professor and librarians can also help you find good resources.

- Keep all of your notes in a physical folder or in a digitized form on the computer.

- Start to form the basic outline of your paper using the notes you have collected.

Writing Your Paper

- Start with bullet points and then add in notes you've taken from references that support your ideas. [1] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- A common way to format research papers is to follow the IMRAD format. This dictates the structure of your paper in the following order: I ntroduction, M ethods, R esults, a nd D iscussion. [2] X Research source

- The outline is just the basic structure of your paper. Don't worry if you have to rearrange a few times to get it right.

- Ask others to look over your outline and get feedback on the organization.

- Know the audience you are writing for and adjust your style accordingly. [3] X Research source

- Use a standard font type and size, such as Times New Roman 12 point font.

- Double-space your paper.

- If necessary, create a cover page. Most schools require a cover page of some sort. Include your main title, running title (often a shortened version of your main title), author's name, course name, and semester.

- Break up information into sections and subsections and address one main point per section.

- Include any figures or data tables that support your main ideas.

- For a quantitative study, state the methods used to obtain results.

- Clearly state and summarize the main points of your research paper.

- Discuss how this research contributes to the field and why it is important. [4] X Research source

- Highlight potential applications of the theory if appropriate.

- Propose future directions that build upon the research you have presented. [5] X Research source

- Keep the introduction and discussion short, and spend more time explaining the methods and results.

- State why the problem is important to address.

- Discuss what is currently known and what is lacking in the field.

- State the objective of your paper.

- Keep the introduction short.

- Highlight the purpose of the paper and the main conclusions.

- State why your conclusions are important.

- Be concise in your summary of the paper.

- Show that you have a solid study design and a high-quality data set.

- Abstracts are usually one paragraph and between 250 – 500 words.

- Unless otherwise directed, use the American Medical Association (AMA) style guide to properly format citations.

- Add citations at end of a sentence to indicate that you are using someone else's idea. Use these throughout your research paper as needed. They include the author's last name, year of publication, and page number.

- Compile your reference list and add it to the end of your paper.

- Use a citation program if you have access to one to simplify the process.

- Continually revise your paper to make sure it is structured in a logical way.

- Proofread your paper for spelling and grammatical errors.

- Make sure you are following the proper formatting guidelines provided for the paper.

- Have others read your paper to proofread and check for clarity. Revise as needed.

Expert Q&A

- Ask your professor for help if you are stuck or confused about any part of your research paper. They are familiar with the style and structure of papers and can provide you with more resources. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Refer to your professor's specific guidelines. Some instructors modify parts of a research paper to better fit their assignment. Others may request supplementary details, such as a synopsis for your research project . Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Set aside blocks of time specifically for writing each day. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Do not plagiarize. Plagiarism is using someone else's work, words, or ideas and presenting them as your own. It is important to cite all sources in your research paper, both through internal citations and on your reference page. Thanks Helpful 4 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178846/

- ↑ http://owl.excelsior.edu/research-and-citations/outlining/outlining-imrad/

- ↑ http://china.elsevier.com/ElsevierDNN/Portals/7/How%20to%20write%20a%20world-class%20paper.pdf

- ↑ http://intqhc.oxfordjournals.org/content/16/3/191

- ↑ http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~bioslabs/tools/report/reportform.html#form

About This Article

To write a medical research paper, research your topic thoroughly and compile your data. Next, organize your notes and create a strong outline that breaks up the information into sections and subsections, addressing one main point per section. Write the results and discussion sections first to go over your findings, then write the introduction to state your objective and provide background information. Finally, write the abstract, which concisely summarizes the article by highlighting the main points. For tips on formatting and using citations, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Joshua Benibo

Jun 5, 2018

Did this article help you?

Dominic Cipriano

Aug 16, 2016

Obiajulu Echedom

Apr 2, 2017

Noura Ammar Alhossiny

Feb 14, 2017

Dawn Daniel

Apr 20, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih clinical research trials and you.

The NIH Clinical Trials and You website is a resource for people who want to learn more about clinical trials. By expanding the below questions, you can read answers to common questions about taking part in a clinical trial.

What are clinical trials and why do people participate?

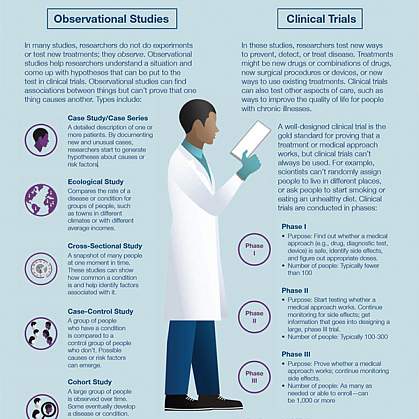

Clinical research is medical research that involves people like you. When you volunteer to take part in clinical research, you help doctors and researchers learn more about disease and improve health care for people in the future. Clinical research includes all research that involves people. Types of clinical research include:

- Epidemiology, which improves the understanding of a disease by studying patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease in specific groups.

- Behavioral, which improves the understanding of human behavior and how it relates to health and disease.

- Health services, which looks at how people access health care providers and health care services, how much care costs, and what happens to patients as a result of this care.

- Clinical trials, which evaluate the effects of an intervention on health outcomes.

What are clinical trials and why would I want to take part?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Clinical trials can study:

- New drugs or new combinations of drugs

- New ways of doing surgery

- New medical devices

- New ways to use existing treatments

- New ways to change behaviors to improve health

- New ways to improve the quality of life for people with acute or chronic illnesses.

The goal of clinical trials is to determine if these treatment, prevention, and behavior approaches are safe and effective. People take part in clinical trials for many reasons. Healthy volunteers say they take part to help others and to contribute to moving science forward. People with an illness or disease also take part to help others, but also to possibly receive the newest treatment and to have added (or extra) care and attention from the clinical trial staff. Clinical trials offer hope for many people and a chance to help researchers find better treatments for others in the future

Why is diversity and inclusion important in clinical trials?

People may experience the same disease differently. It’s essential that clinical trials include people with a variety of lived experiences and living conditions, as well as characteristics like race and ethnicity, age, sex, and sexual orientation, so that all communities benefit from scientific advances.

See Diversity & Inclusion in Clinical Trials for more information.

How does the research process work?

The idea for a clinical trial often starts in the lab. After researchers test new treatments or procedures in the lab and in animals, the most promising treatments are moved into clinical trials. As new treatments move through a series of steps called phases, more information is gained about the treatment, its risks, and its effectiveness.

What are clinical trial protocols?

Clinical trials follow a plan known as a protocol. The protocol is carefully designed to balance the potential benefits and risks to participants, and answer specific research questions. A protocol describes the following:

- The goal of the study

- Who is eligible to take part in the trial

- Protections against risks to participants

- Details about tests, procedures, and treatments

- How long the trial is expected to last

- What information will be gathered

A clinical trial is led by a principal investigator (PI). Members of the research team regularly monitor the participants’ health to determine the study’s safety and effectiveness.

What is an Institutional Review Board?

Most, but not all, clinical trials in the United States are approved and monitored by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure that the risks are reduced and are outweighed by potential benefits. IRBs are committees that are responsible for reviewing research in order to protect the rights and safety of people who take part in research, both before the research starts and as it proceeds. You should ask the sponsor or research coordinator whether the research you are thinking about joining was reviewed by an IRB.

What is a clinical trial sponsor?

Clinical trial sponsors may be people, institutions, companies, government agencies, or other organizations that are responsible for initiating, managing or financing the clinical trial, but do not conduct the research.

What is informed consent?

Informed consent is the process of providing you with key information about a research study before you decide whether to accept the offer to take part. The process of informed consent continues throughout the study. To help you decide whether to take part, members of the research team explain the details of the study. If you do not understand English, a translator or interpreter may be provided. The research team provides an informed consent document that includes details about the study, such as its purpose, how long it’s expected to last, tests or procedures that will be done as part of the research, and who to contact for further information. The informed consent document also explains risks and potential benefits. You can then decide whether to sign the document. Taking part in a clinical trial is voluntary and you can leave the study at any time.

What are the types of clinical trials?

There are different types of clinical trials.

- Prevention trials look for better ways to prevent a disease in people who have never had the disease or to prevent the disease from returning. Approaches may include medicines, vaccines, or lifestyle changes.

- Screening trials test new ways for detecting diseases or health conditions.

- Diagnostic trials study or compare tests or procedures for diagnosing a particular disease or condition.

- Treatment trials test new treatments, new combinations of drugs, or new approaches to surgery or radiation therapy.

- Behavioral trials evaluate or compare ways to promote behavioral changes designed to improve health.

- Quality of life trials (or supportive care trials) explore and measure ways to improve the comfort and quality of life of people with conditions or illnesses.

What are the phases of clinical trials?

Clinical trials are conducted in a series of steps called “phases.” Each phase has a different purpose and helps researchers answer different questions.

- Phase I trials : Researchers test a drug or treatment in a small group of people (20–80) for the first time. The purpose is to study the drug or treatment to learn about safety and identify side effects.

- Phase II trials : The new drug or treatment is given to a larger group of people (100–300) to determine its effectiveness and to further study its safety.

- Phase III trials : The new drug or treatment is given to large groups of people (1,000–3,000) to confirm its effectiveness, monitor side effects, compare it with standard or similar treatments, and collect information that will allow the new drug or treatment to be used safely.

- Phase IV trials : After a drug is approved by the FDA and made available to the public, researchers track its safety in the general population, seeking more information about a drug or treatment’s benefits, and optimal use.

What do the terms placebo, randomization, and blinded mean in clinical trials?

In clinical trials that compare a new product or therapy with another that already exists, researchers try to determine if the new one is as good, or better than, the existing one. In some studies, you may be assigned to receive a placebo (an inactive product that resembles the test product, but without its treatment value).

Comparing a new product with a placebo can be the fastest and most reliable way to show the new product’s effectiveness. However, placebos are not used if you would be put at risk — particularly in the study of treatments for serious illnesses — by not having effective therapy. You will be told if placebos are used in the study before entering a trial.

Randomization is the process by which treatments are assigned to participants by chance rather than by choice. This is done to avoid any bias in assigning volunteers to get one treatment or another. The effects of each treatment are compared at specific points during a trial. If one treatment is found superior, the trial is stopped so that the most volunteers receive the more beneficial treatment. This video helps explain randomization for all clinical trials .

" Blinded " (or " masked ") studies are designed to prevent members of the research team and study participants from influencing the results. Blinding allows the collection of scientifically accurate data. In single-blind (" single-masked ") studies, you are not told what is being given, but the research team knows. In a double-blind study, neither you nor the research team are told what you are given; only the pharmacist knows. Members of the research team are not told which participants are receiving which treatment, in order to reduce bias. If medically necessary, however, it is always possible to find out which treatment you are receiving.

Who takes part in clinical trials?

Many different types of people take part in clinical trials. Some are healthy, while others may have illnesses. Research procedures with healthy volunteers are designed to develop new knowledge, not to provide direct benefit to those taking part. Healthy volunteers have always played an important role in research.

Healthy volunteers are needed for several reasons. When developing a new technique, such as a blood test or imaging device, healthy volunteers help define the limits of "normal." These volunteers are the baseline against which patient groups are compared and are often matched to patients on factors such as age, gender, or family relationship. They receive the same tests, procedures, or drugs the patient group receives. Researchers learn about the disease process by comparing the patient group to the healthy volunteers.

Factors like how much of your time is needed, discomfort you may feel, or risk involved depends on the trial. While some require minimal amounts of time and effort, other studies may require a major commitment of your time and effort, and may involve some discomfort. The research procedure(s) may also carry some risk. The informed consent process for healthy volunteers includes a detailed discussion of the study's procedures and tests and their risks.

A patient volunteer has a known health problem and takes part in research to better understand, diagnose, or treat that disease or condition. Research with a patient volunteer helps develop new knowledge. Depending on the stage of knowledge about the disease or condition, these procedures may or may not benefit the study participants.

Patients may volunteer for studies similar to those in which healthy volunteers take part. These studies involve drugs, devices, or treatments designed to prevent,or treat disease. Although these studies may provide direct benefit to patient volunteers, the main aim is to prove, by scientific means, the effects and limitations of the experimental treatment. Therefore, some patient groups may serve as a baseline for comparison by not taking the test drug, or by receiving test doses of the drug large enough only to show that it is present, but not at a level that can treat the condition.

Researchers follow clinical trials guidelines when deciding who can participate, in a study. These guidelines are called Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria . Factors that allow you to take part in a clinical trial are called "inclusion criteria." Those that exclude or prevent participation are "exclusion criteria." These criteria are based on factors such as age, gender, the type and stage of a disease, treatment history, and other medical conditions. Before joining a clinical trial, you must provide information that allows the research team to determine whether or not you can take part in the study safely. Some research studies seek participants with illnesses or conditions to be studied in the clinical trial, while others need healthy volunteers. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are not used to reject people personally. Instead, the criteria are used to identify appropriate participants and keep them safe, and to help ensure that researchers can find new information they need.

What do I need to know if I am thinking about taking part in a clinical trial?

Risks and potential benefits

Clinical trials may involve risk, as can routine medical care and the activities of daily living. When weighing the risks of research, you can think about these important factors:

- The possible harms that could result from taking part in the study

- The level of harm

- The chance of any harm occurring

Most clinical trials pose the risk of minor discomfort, which lasts only a short time. However, some study participants experience complications that require medical attention. In rare cases, participants have been seriously injured or have died of complications resulting from their participation in trials of experimental treatments. The specific risks associated with a research protocol are described in detail in the informed consent document, which participants are asked to consider and sign before participating in research. Also, a member of the research team will explain the study and answer any questions about the study. Before deciding to participate, carefully consider risks and possible benefits.

Potential benefits

Well-designed and well-executed clinical trials provide the best approach for you to:

- Help others by contributing to knowledge about new treatments or procedures.

- Gain access to new research treatments before they are widely available.

- Receive regular and careful medical attention from a research team that includes doctors and other health professionals.

Risks to taking part in clinical trials include the following:

- There may be unpleasant, serious, or even life-threatening effects of experimental treatment.

- The study may require more time and attention than standard treatment would, including visits to the study site, more blood tests, more procedures, hospital stays, or complex dosage schedules.

What questions should I ask if offered a clinical trial?

If you are thinking about taking part in a clinical trial, you should feel free to ask any questions or bring up any issues concerning the trial at any time. The following suggestions may give you some ideas as you think about your own questions.

- What is the purpose of the study?

- Why do researchers think the approach may be effective?

- Who will fund the study?

- Who has reviewed and approved the study?

- How are study results and safety of participants being monitored?

- How long will the study last?

- What will my responsibilities be if I take part?

- Who will tell me about the results of the study and how will I be informed?

Risks and possible benefits

- What are my possible short-term benefits?

- What are my possible long-term benefits?

- What are my short-term risks, and side effects?

- What are my long-term risks?

- What other options are available?

- How do the risks and possible benefits of this trial compare with those options?

Participation and care

- What kinds of therapies, procedures and/or tests will I have during the trial?

- Will they hurt, and if so, for how long?

- How do the tests in the study compare with those I would have outside of the trial?

- Will I be able to take my regular medications while taking part in the clinical trial?

- Where will I have my medical care?

- Who will be in charge of my care?

Personal issues

- How could being in this study affect my daily life?

- Can I talk to other people in the study?

Cost issues

- Will I have to pay for any part of the trial such as tests or the study drug?

- If so, what will the charges likely be?

- What is my health insurance likely to cover?

- Who can help answer any questions from my insurance company or health plan?

- Will there be any travel or child care costs that I need to consider while I am in the trial?

Tips for asking your doctor about trials

- Consider taking a family member or friend along for support and for help in asking questions or recording answers.

- Plan what to ask — but don't hesitate to ask any new questions.

- Write down questions in advance to remember them all.

- Write down the answers so that they’re available when needed.

- Ask about bringing a tape recorder to make a taped record of what's said (even if you write down answers).

This information courtesy of Cancer.gov.

How is my safety protected?

Ethical guidelines

The goal of clinical research is to develop knowledge that improves human health or increases understanding of human biology. People who take part in clinical research make it possible for this to occur. The path to finding out if a new drug is safe or effective is to test it on patients in clinical trials. The purpose of ethical guidelines is both to protect patients and healthy volunteers, and to preserve the integrity of the science.

Informed consent

Informed consent is the process of learning the key facts about a clinical trial before deciding whether to participate. The process of providing information to participants continues throughout the study. To help you decide whether to take part, members of the research team explain the study. The research team provides an informed consent document, which includes such details about the study as its purpose, duration, required procedures, and who to contact for various purposes. The informed consent document also explains risks and potential benefits.

If you decide to enroll in the trial, you will need to sign the informed consent document. You are free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Most, but not all, clinical trials in the United States are approved and monitored by an Institutional Review Board (IRB) to ensure that the risks are minimal when compared with potential benefits. An IRB is an independent committee that consists of physicians, statisticians, and members of the community who ensure that clinical trials are ethical and that the rights of participants are protected. You should ask the sponsor or research coordinator whether the research you are considering participating in was reviewed by an IRB.

Further reading

For more information about research protections, see:

- Office of Human Research Protection

- Children's Assent to Clinical Trial Participation

For more information on participants’ privacy and confidentiality, see:

- HIPAA Privacy Rule

- The Food and Drug Administration, FDA’s Drug Review Process: Ensuring Drugs Are Safe and Effective

For more information about research protections, see: About Research Participation

What happens after a clinical trial is completed?

After a clinical trial is completed, the researchers carefully examine information collected during the study before making decisions about the meaning of the findings and about the need for further testing. After a phase I or II trial, the researchers decide whether to move on to the next phase or to stop testing the treatment or procedure because it was unsafe or not effective. When a phase III trial is completed, the researchers examine the information and decide whether the results have medical importance.

Results from clinical trials are often published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Peer review is a process by which experts review the report before it is published to ensure that the analysis and conclusions are sound. If the results are particularly important, they may be featured in the news, and discussed at scientific meetings and by patient advocacy groups before or after they are published in a scientific journal. Once a new approach has been proven safe and effective in a clinical trial, it may become a new standard of medical practice.

Ask the research team members if the study results have been or will be published. Published study results are also available by searching for the study's official name or Protocol ID number in the National Library of Medicine's PubMed® database .

How does clinical research make a difference to me and my family?

Only through clinical research can we gain insights and answers about the safety and effectiveness of treatments and procedures. Groundbreaking scientific advances in the present and the past were possible only because of participation of volunteers, both healthy and those with an illness, in clinical research. Clinical research requires complex and rigorous testing in collaboration with communities that are affected by the disease. As research opens new doors to finding ways to diagnose, prevent, treat, or cure disease and disability, clinical trial participation is essential to help us find the answers.

This page last reviewed on October 3, 2022

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

- Education Home

- Medical Education Technology Support

- Graduate Medical Education

- Medical Scientist Training Program

- Public Health Sciences Program

- Continuing Medical Education

- Clinical Performance Education Center

- Center for Excellence in Education

- Research Home

- Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics

- Biomedical Engineering

- Cell Biology

- Genome Sciences

- Microbiology, Immunology, & Cancer Biology (MIC)

- Molecular Physiology & Biological Physics

- Neuroscience

- Pharmacology

- Public Health Sciences

- Office for Research

- Clinical Research

- Clinical Trials Office

- Funding Opportunities

- Grants & Contracts

- Research Faculty Directory

- Cancer Center

- Cardiovascular Research Center

- Carter Immunology Center

- Center for Behavioral Health & Technology

- Center for Brain Immunology & Glia

- Center for Diabetes Technology

- Center for Immunity, Inflammation & Regenerative Medicine

- Center for Membrane & Cell Physiology

- Center for Research in Reproduction

- Myles H. Thaler Center for AIDS & Human Retrovirus Research

- Child Health Research Center (Pediatrics)

- Division of Perceptual Studies

- Research News: The Making of Medicine

- Core Facilities

- Virginia Research Resources Consortium

- Center for Advanced Vision Science

- Charles O. Strickler Transplant Center

- Keck Center for Cellular Imaging

- Institute of Law, Psychiatry & Public Policy

- Translational Health Research Institute of Virginia

- Clinical Home

- Anesthesiology

- Dermatology

- Emergency Medicine

- Family Medicine

- Neurosurgery

- Obstetrics & Gynecology

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopaedic Surgery

- Otolaryngology

- Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation

- Plastic Surgery, Maxillofacial, & Oral Health

- Psychiatry & Neurobehavioral Sciences

- Radiation Oncology

- Radiology & Medical Imaging

- UVA Health: Patient Care

- Diversity Home

- Diversity Overview

- Student Resources

- GME Trainee Resources

- Faculty Resources

- Community Resources

- Getting Started in Clinical Research

Industry-initiated clinical trials

The majority of clinical studies conduced at the SOM are industry-designed and -sponsored Phase 1 to Phase 3 clinical trials, with the ultimate goal of FDA product licensure. The investigator’s role in these studies varies considerably. Most of these studies are multicenter studies that follow a protocol developed by the sponsor with little intellectual input by the investigators. At the other extreme are single site studies where the investigator plays a primary role in the design as well as the execution of the study. The process associated with industry-initiated studies follows this general schema:

- Individual faculty can contact a company directly; alternately, the sponsor or its contract research organization (CRO) will inquire if an investigator wishes to participate in a planned study.

- Because company product development plans are confidential, the PI must sign a confidentiality disclosure agreement (CDA) before being sent a full protocol for consideration. If you receive a CDA, review it and forward it to SOM Grants and Contracts, which negotiates and signs such documents.

- The company will provide a protocol synopsis and a feasibility questionnaire for the faculty to review and complete.

- The company may conduct a preliminary site visit or hold an investigator’s meeting to discuss the project in greater depth.

- The PI must submit the protocol for review and approval by the IRB. If the research is being performed under the auspices of the UVA Cancer Center, its review committee must approve, as well. Please note that a clinical trials agreement with the sponsor may not be signed and recruitment and clinical activities cannot take place prior to IRB approval.

- The sponsor will ask the PI to complete an FDA form 1572 (statement of investigator). By signing this form, the investigator assumes responsibility for all aspects of the conduct of the study at the UVa site. In most cases the sponsor will present a completed form, along with a financial disclosure statement, to the investigator for signature.

- The clinical trials agreement is a binding contract defining the study to be undertaken, remuneration, reporting, intellectual property, confidentiality, publication rights, etc. The Office of Grants and Contracts signs these agreements and can provide a sample agreement. The F&A rate on clinical trials is 25% of total direct costs.

- Representatives of the sponsor hold a study initiation meeting with the PI and his/her team to walk through the study protocol prior to initiation of recruitment. This ensures that the latest, approved versions of protocols, consent forms, and case report forms are understood and used appropriately by all parties.

- Study initiation, conduct, and close-out.

Investigator-initiated clinical research

Initiating one’s own clinical research project provides greater flexibility but comes with greater responsibilities. A brief outline of these, with resources for help on each, follows:

- Funding. NIH and the corporate sector support investigator-initiated protocols. Many clinical research studies can be funded by routine K- or R-series awards. There are special considerations, however, for studies that are defined as clinical trials (see NIH definition ). Some NIH Institutes and Centers fund Clinical Trial Planning Grants (R34) to prepare for Phase III trials. Full trials are funded via a different mechanism, such as a clinical U01. Institutes have varying policies on the investigator-initiated research they will accept. See, for example, NHLBI and NIAID web sites on clinical awards. Industry supports investigator-initiated projects that are in concert with the existing development pathway for one of their products or that test innovative uses of an existing drug.

- Intellectual property. Inventions generated in the course of an investigator-initiated trial are the property of the University and subject to its Patent Policy.

- IND Application and reports to FDA. If the trial involves the administration or implantation of a drug, biologic, or device in a manner or for an indication that is not FDA approved, the PI may have to file and maintain an Investigational New Drug (IND) or Investigational Device Exemption Application (IDE) with the FDA. The Clinical Research Office can assist with assessing the need for an IND/IDE. The faculty sponsor of an IND/IDE is responsible for meeting all monitoring and reporting to the FDA on all studies initiated under that approval. For faculty who sponsor studies at sites other than UVa, the Clinical Research Office can assist with monitoring services at remote sites. The cost of this monitoring must be included in your study budget.

- Publication of the protocol on a public web site. The University requires that corporate sponsors of research contracts publish their clinical trials on a public site such as ClinicalTrials.gov (as does NIH, for trials under its support). Furthermore, U.S. Public Law 110-85 requires that the sponsor of an IND/IDE or PI register all trials of drugs and biologics subject to FDA regulation (other than Phase 1) and trials of devices (except for small feasibility and pediatric postmarket surveillance) and post information on results of those trials. The Clinical Research Office can assist with posting a study on ClinicalTrials.gov . Finally, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors has mandated that all Phase 1 clinical trials published in their journals must be registered at a public site.

- Source of study drug, if an unlicensed product. The mode of manufacture, testing for purity/adherence to specifications, and packaging of drugs, biologics, or devices must be described in the IND/IDE Application. These generally are performed under Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), often by an outside contractor.

- Project management. The PI must develop a Manual of Procedures, study documents (protocol, consent, case report forms), Data Safety Monitoring Committee, reporting procedures for adverse events, etc. These administrative requirements vary depending on whether the clinical research meets the definition of a clinical trial and are even more demanding for multi-center clinical research projects, where several PIs, clinical research coordinators, and IRBs are involved.

Responsibilities in clinical research

The principal investigator is responsible for:.

- assuring that the study budget is adequate for the planned studies, including required payments to the Medical Center and providers of the various clinical services;

- obtaining IRB approval of the study protocol prior to initiating research, and any subsequent modifications to the study protocol or forms before initiating any changes in study procedures;

- submitting required progress and adverse event reports to the IRB;

- ensuring that all members of the research team follow Good Clinical Practice (see below) and comply with IRB requirements;

- compliance with federal regulations such as HIPAA, use of hazardous materials, etc.;

- assuring that clinical charges are billed appropriately to third party payors as standard of care or to the study funds as research;

- notifying the IRB and UVA Conflicts of Interest (COI) Committee of existing financial COIs and newly-occurring COIs through the end of the study.

Clinical research coordinators are responsible for:

- managing the conduct of clinical trials, under the direction of the PI;

- maintaining in-depth knowledge of protocol requirements and Good Clinical Practice as set forth by federal regulations;

- sound conduct of the clinical trial per protocol, from recruitment through follow-up;

- meticulous maintenance of accurate and complete documentation (e.g., regulatory documents, signed consent forms, IRB approvals, source documents, drug dispensing and subject logs, and study-related communication);

- organizational management of the trial (e.g., timeliness in completing case report forms, data entry, reporting adverse events [AEs], and managing caseload and study files);

- communication of protocol-related problems to all study staff and PI (e.g., questions regarding the conduct of the clinical trial, possible AEs, or subject compliance);

- professional conduct in the presence of subjects, research staff, sponsors, monitors, auditors, etc.

Preparing budgets and billing for clinical trials

The investigator must recover all study costs. Rarely, due to the scientific importance of a particular study and the existence of local funds to make up the shortfall , an investigator may choose to participate at a financial loss. The Clinical Research Office can assist in the development of study budgets. Its personnel have access to current hospital laboratory charges and knowledge of a variety of costs that may not initially be apparent to new PIs. See their guidance on budgeting for a clinical trial .

The PI must ensure that all billing for costs incurred in the conduct of clinical studies is appropriate and in compliance with relevant laws and regulations. Clinical protocols may include both standard-of-care and experimental activities (i.e., not medically necessary or known to be effective). Standard-of-care procedures may be billed to government or private insurers or to the subject, except when the sponsor has agreed to cover those costs. In general, activities that are purely experimental may not be billed to Medicare, Medicaid, other third party insurers, or the research subject: these are the responsibility of the sponsor. (Rarely, per law or regulation, costs for experimental activities required for a clinical trial may be billed to a third party or to the subject, if they are not reimbursed by the sponsor.)

The Clinical Research Office provides assistance with development of a billing plan delineating which study procedures and interventions are standard-of-care vs. investigational, and who (sponsor, insurer, patient) will be financially responsible for each. In addition, the CTO can assist with properly budgeting for those interventions that will be billed to the study budget.

Development and submission of human use protocols to the IRB

Protocols are submitted to the IRBs via an on-line system . The IRB offers help in protocol development, either directly or through IRB support personnel in the various clinical departments of the School of Medicine.

Training for investigators and clinical research coordinators (CRCs)

The Clinical Research Office conducts continuing education programs for both clinical investigators and CRCs, including an annual series, “brown bag” sessions, mentoring of CRCs , and link to the NIH Clinical Center’s video series, “Introduction to Principles and Practices of Clinical Research.”

Hiring clinical research staff

CRCs and clinical research managers are hired through UVA Human Resources , in the “Health Care Compliance Specialist/Manager” or “Registered Nurse (Inpatient Research)” series, with the assistance of their department HR representative. These positions are described at the HR Web site .

Pharmacy services

The Medical Center’s Investigational Drug Service supports clinical research research (including randomization, blinding, preparation of placebos, storage and inventory of medications, etc.). These services are provided at cost to the investigator.

Biostatistical support

The Division of Biostatistics & Epidemiology (Dept. of Public Health Sciences) can help with study design, development of analytic plans, and analysis of pilot and clinical study data. Contact Dr. Jae Lee (982-1033, [email protected] ) for additional information. The Division also has posted on its Web site a request for biostatistical services form .

Accessing SOM/UVA research core facilities

SOM core facilities provide subsidized services at reasonable cost to University users; for clinical investigators, these might include flow cytometry, DNA sequencing, or the biorepository and tissue research facility. Certain research centers and complex NIH research awards provide additional cores to support patient-oriented research.

Recruiting research subjects

UVA IRBs conform to federal restrictions on what can be included in advertisements.

Quality assurance (QA) and monitoring activities

QA includes the development and maintenance of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for clinical trials, training of clinical research personnel in study methods and regulatory compliance, and assistance in preparing for FDA, sponsor, or internal audits. Monitoring includes the following: tracking of patient accrual; assessment of patient eligibility and evaluability (e.g., completeness and accuracy of study records); reporting of adverse events to IRB and other investigators (PI/CRC responsibility); and interim evaluation of outcome measures and patient safety information (often conducted by an independent Data Safety Monitoring Committee). The majority of these functions are provided by the ClinicalResearch Office to ensure quality of study results, protect subject safety, and to maintain statutory and regulatory compliance.

Environmental health and safety

Use of recombinant DNA or pathogens in clinical research or handling of patient/subject specimens outside of the Medical Center clinical laboratories requires approval of the Institutional Biosafety Committee. Use of biological, chemical, or radioactive hazards in clinical research is overseen by, and requires training administered by and approval of the Office of Environmental Health and Safety .

Responsible conduct of research

In order to ensure that the public can trust research performed by UVA investigators, the highest standards must be maintained by its faculty and staff. See a broader discussion of this topic on this site.

- Good Clinical Practice (GCP). GCP is a broad set of practices required by regulatory agencies (e.g., the FDA and the International Conference on Harmonisation ) to ensure the quality clinical trials data that serve as the basis for licensure of drugs, biologics, and devices. These guidelines include such activities as IRB procedures, minimizing risks to research subjects, investigator and sponsor qualifications and responsibilities, recordkeeping, and so on.

- Authorship and data integrity policies. Refer to the SOM policy on authorship and to the UVA Research Misconduct Policy , which covers data integrity.

- Conflict of interest (COI). Clinical investigators should carefully avoid the appearance of conflict of interest (COI) because of the participation of research subjects and the potential impact of this research on patient care or health policy. Financial interests of study staff or their families must not influence, or appear to influence, the design, conduct or reporting of any clinical research. When submitting a protocol to the IRB or a clinical research proposal to the Office of Grants and Contracts, the PI should notify these offices of any potential financial conflict. Refer to this more detailed description of COI policy and procedures.

- Incentive payments. UVA SOM employees may not accept the following types of incentive payments in the conduct of clinical trials (see SOM Policy, ” Payments for Referring or Enrolling Patients in Clinical Trials “): time/enrollment incentives (bonus for enrollment by a certain date); milestone-based incentives (payment when all forms have been submitted); or enrollment-based incentives (payment for a specific number of patients, rather than flat per-patient remuneration).

Navigating regulatory compliance requirements at UVA

Several committees and offices are charged with compliance oversight of clinical research. In many cases the review process is sequential, with action by one office contingent on prior approval by another. The process can be most efficiently navigated as follows:

1. General requirements that are not protocol-specific:

- Hiring a study coordinator. A well-trained study coordinator is not required for the conduct of clinical research but is strongly recommended. The requirements for regulatory compliance for human subjects research are complex and evolving. A study coordinator can help assure that these requirements are met and appropriate documentation is maintained. The Clinical Research Office can provide on-site mentoring of study coordinators.

- IRB training. All study personnel who will have access to human subjects or to research data from identifiable human subjects must complete the on-line IRB training modules , which may take several hours to complete. This training must be completed before the IRB will approve a study. Incoming faculty may complete this training before arriving at UVA, to expedite subsequent protocol submission.

- Institutional Biosafety Committee training. For studies that will collect or handle specimens from human subjects outside the clinical areas of the Medical Center, faculty and staff must complete appropriate IBC training for bloodborne pathogens . Bloodborne pathogens training for health care personnel provided by the Medical Center is not a substitute for the IBC training module. If biohazardous substances will be shipped, the individual(s) responsible must complete a specific training program on shipping infectious substances .

2. Once the protocol has been developed:

- Budgeting. The investigator is responsible for assuring that the budget is sufficient to fund all study related expenses. Budgets involving patients who may also be receiving non-research related care in the Medical Center or that involve purchase of clinical services from the Medical Center can be particularly challenging. Physician providers cannot negotiate charges for Medical Center procedures . Charges for Medical Center services will be billed to the study, based on a fixed formula for the cost of the service. The Clinical Research Office can help generate an appropriate budget for these services. The PI must also assure the differentiation of standard of care charges (that may be legally charged to third party payors) from study charges that must be funded by the sponsor. The Clinical Research Office can also assist with this aspect of budgeting.

- Initiation of the study agreement for industry sponsors. SOM Grants and Contracts will not sign a study agreement without IRB approval. Negotiating the agreement can be quite time consuming, so it is prudent to start this process early. Initiation of this process requires that you submit a Proposal Approval Sheet , via your department administration, to Grants and Contracts. Although not all the information requested on the form will be known at this point, complete as much as possible. Your Chair’s countersignature on this form indicates his or her commitment to the time and space required to perform the study. The PI also must submit a Conflict of Interest Disclosure form and a Drug Study Questionnaire , if required.

- IBC registration. Your specific protocol must be registered with the IBC if specimens from human subjects will be handled in areas other than designated clinical space (see https://ehs.virginia.edu/Biosafety-IBC.html ). The IRB will not approve a study until the PI has received an approved registration from the IBC.

- Assessment of the need for an IND/IDE. If the sponsor does not already have an IND/IDE or if the study is investigator-initiated, an investigator-initiated IND/IDE will be required if the study uses a drug or device that is not already approved by the FDA or an FDA-approved drug or device in a manner in any way different from its approved use. The Clinical Research Office can help assess the need for an IND/IDE.

3. Navigating the review committees:

- Cancer trials. If the study involves cancer patients, it must be reviewed by the Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee before submission to either the GCRC (if applicable) or the IRB. The committee meets monthly and the protocol must be submitted at least three weeks before the next scheduled meeting. See Protocol Review Committee guidance .

- IRB review. Studies involving human subjects must be approved by the IRB. Protocols must be submitted on forms generated by the IRB Protocol Builder. See IRB guidance . The protocol must be submitted for pre-review at least 5 days before the full submission deadline. IRB meetings are scheduled every two weeks; submission deadlines are approximately 8 days prior to each meeting.

4. Once you have IRB approval:

- Submit the signed IRB approval (Form 310) to Grants and Contracts to allow the study agreement to be signed.

- Post-award Administration

- Contracts and Clinical Trials Agreements

- Intellectual Property (IP) and Entrepreneurial Activities

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Material Transfer Agreements

- Medical Student Research Programs at UVA

- Medical Student Research Symposium

- MSSRP On-Line Preceptor Form

- MSSRP On-Line Student Match Form

- On-line Systems

- Other Medical Student Research Opportunities

- Research: Financial Interest of Faculty

- Review of Proposed Consulting Agreements

- Transfers of NIH/Public Health Service awards

- Unmatched MSSRP projects – 2024

- Research Centers and Programs

- Roles and responsibilities in research administration

- Other Offices Supporting Research

- SBIR and STTR Awards

- Information for students and postdoctoral trainees

- For Research Administrators

- For New Research Faculty

- Funding Programs for Junior Faculty

- NIH for new faculty

- School of Medicine surplus equipment site

- Forms and Documents

- FAQs – SOM offices supporting research

- 2024 Faculty Research Retreat

- Anderson Lecture and Symposia

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to get involved in...

How to get involved in research as a medical student

- Related content

- Peer review

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £50 / $60/ €56 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

Medical Research

How to conduct research as a medical student, this article will address how to conduct research as a medical student, including details on different types of research, how to go about constructing an idea and other practical advice., kevin seely, oms iv.

Student Doctor Seely attends the Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine.

In addition to good grades, test performance, and notable characteristics, it is becoming increasingly important for medical students to participate in and publish research. Residency programs appreciate seeing that applicants are interested in improving the treatment landscape of medicine through the scientific method.

Many medical students also recognize that research is important. However, not all schools emphasize student participation in research or have associations with research labs. These factors, among others, often leave students wanting to do research but unsure of how to begin. This article will address how to conduct research as a medical student, including details on different types of research, how to go about constructing an idea, and other practical advice.

Types of research commonly conducted by medical students

This is not a comprehensive list, but rather, a starting point.

Case reports and case series

Case reports are detailed reports of the clinical course of an individual patient. They usually describe an unusual or novel occurrence or provide new evidence related to a specific pathological entity and its treatment. Advantages of case reports include a relatively fast timeline and little to no need for funding. A disadvantage, though, is that these contribute the most basic and least powerful scientific evidence and provide researchers with minimal exposure to the scientific process.

Case series, on the other hand, look at multiple patients retrospectively. In addition, statistical calculations can be performed to achieve significant conclusions, rendering these studies great for medical students to complete to get a full educational experience.

Clinical research

Clinical research is the peak of evidence-based medical research. Standard study designs include case-controlled trials, cohort studies or survey-based research. Clinical research requires IRB review, strict protocols and large sample sizes, thus requiring dedicated time and often funding. These can serve as barriers for medical students wanting to conduct this type of research. Be aware that the AOA offers students funding for certain research projects; you can learn more here . This year’s application window has closed, but you can always plan ahead and apply for the next grant cycle.

The advantages of clinical research include making a significant contribution to the body of medical knowledge and obtaining an understanding of what it takes to conduct clinical research. Some students take a dedicated research year to gain experience in this area.

Review articles

A literature review is a collection and summarization of literature on an unresolved, controversial or novel topic. There are different categories of reviews, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews and traditional literature reviews, offering very high, high and modest evidentiary value, respectively. Advantages of review articles include the possibility of remote collaboration and developing expertise on the subject matter. Disadvantages can include the time needed to complete the review and the difficulty of publishing this type of research.

Forming an idea

Research can be inspiring and intellectually stimulating or somewhat painful and dull. It’s helpful to first find an area of medicine in which you are interested and willing to invest time and energy. Then, search for research opportunities in this area. Doing so will make the research process more exciting and will motivate you to perform your best work. It will also demonstrate your commitment to your field of interest.

Think carefully before saying yes to studies that are too far outside your interests. Having completed research on a topic about which you are passionate will make it easier to recount your experience with enthusiasm and understanding in interviews. One way to refine your idea is by reading a recent literature review on your topic, which typically identifies gaps in current knowledge that need further investigation.

Finding a mentor

As medical students, we cannot be the primary investigator on certain types of research studies. So, you will need a mentor such as a DO, MD or PhD. If a professor approaches you about a research study, say yes if it’s something you can commit to and find interesting.

More commonly, however, students will need to approach a professor about starting a project. Asking a professor if they have research you can join is helpful, but approaching them with a well-thought-out idea is far better. Select a mentor whose area of interest aligns with that of your project. If they seem to think your idea has potential, ask them to mentor you. If they do not like your idea, it might open up an intellectual exchange that will refine your thinking. If you proceed with your idea, show initiative by completing the tasks they give you quickly, demonstrating that you are committed to the project.

Writing and publishing

Writing and publishing are essential components of the scientific process. Citation managers such as Zotero, Mendeley, and Connected Papers are free resources for keeping track of literature. Write using current scientific writing standards. If you are targeting a particular journal, you can look up their guidelines for writing and referencing. Writing is a team effort.

When it comes time to publish your work, consult with your mentor about publication. They may or may not be aware of an appropriate journal. If they’re not, Jane , the journal/author name estimator, is a free resource to start narrowing down your journal search. Beware of predatory publishing practices and aim to submit to verifiable publications indexed on vetted databases such as PubMed.

One great option for the osteopathic profession is the AOA’s Journal of Osteopathic Medicine (JOM). Learn more about submitting to JOM here .

My experience

As a second-year osteopathic medical student interested in surgery, my goal is to apply to residency with a solid research foundation. I genuinely enjoy research, and I am a member of my institution’s physician-scientist co-curricular track. With the help of amazing mentors and co-authors, I have been able to publish a literature review and a case-series study in medical school. I currently have some additional projects in the pipeline as well.

My board exams are fast approaching, so I will soon have to adjust the time I am currently committing to research. Once boards are done, though, you can bet I will be back on the research grind! I am so happy to be on this journey with all my peers and colleagues in medicine. Research is a great way to advance our profession and improve patient care.

Keys to success

Research is a team effort. Strive to be a team player who communicates often and goes above and beyond to make the project a success. Be a finisher. Avoid joining a project if you are not fully committed, and employ resiliency to overcome failure along the way. Treat research not as a passive process, but as an active use of your intellectual capability. Push yourself to problem-solve and discover. You never know how big of an impact you might make.

Disclaimers:

Human subject-based research always requires authorization and institutional review before beginning. Be sure to follow your institution’s rules before engaging in any type of research.

This column was written from the perspective from a current medical student with the review and input from my COM’s director of research and scholarly activity, Amanda Brooks, PhD.

Related reading:

H ow to find a mentor in medical school

Tips on surviving—and thriving—during your first year of medical school

The DO schools on U.S. News’ best medical schools list for 2024

A life in medicine, in memoriam: july 2024, 2024 presidential inauguration, embracing excellence: 128th aoa president teresa a. hubka, do, calls for a new era of osteopathic medicine, on the frontlines, new documents illuminate the civil war legacy of a.t. still, md, do, going for the gold, pathway to paris: dos prepare to support athletes in summer olympic/paralympic games, more in training.

AOA works to advance understanding of student parity issues

AOA leaders discuss student parity issues with ACGME, medical licensing board staff and GME program staff.

PCOM hosts annual Research Day showcasing scholarly activity across the college’s 3 campuses

Event highlighted research on important topics such as gun violence and COPD.

Previous article

Next article, one comment.

Thanks! Your write out is educative.

Leave a comment Cancel reply Please see our comment policy

- 1-844-994-6376

- [email protected]

The Guide to Becoming a Medical Researcher

- February 1, 2023

Share Post:

As a medical researcher, your job is to conduct research to improve the health status and longevity of the population. The career revolves around understanding the causes, treatments, and prevention of diseases and medical conditions through rigorous clinical investigations, epidemiological studies, and laboratory experiments. As a medical researcher, simply gaining formal education won’t suffice. You also need to hone your communication, critical thinking, decision-making, data collecting, data analyzing and observational skills. These skill sets will enable you to create a competitive edge in the research industry. On a typical day, a medical researcher would be collecting, interpreting, and analyzing data from clinical trials, working alongside engineering, regulatory, and quality assurance experts to evaluate the risk of medical devices, or maybe even preparing and examining medical samples for causes or treatments of toxicity, disease, or pathogens.

How To Become a Medical Research Doctor?

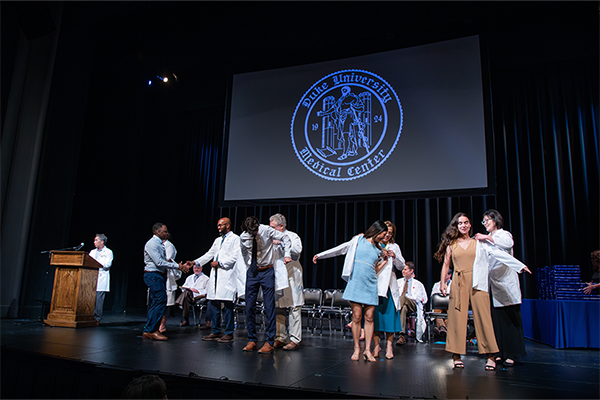

The roadmap to medical research is a bit tricky to navigate, because it is a profession that demands distinctive skills and expertise along with mandatory formal education. If you harbor an interest in scientific exploration and a desire to break new ground in medical knowledge, the first step is to earn a bachelor’s degree in a related field, such as biology, chemistry, or biochemistry. After completing your undergraduate education, you will need to earn a Medical Degree ( MD ) or a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) degree, from a quality institution such as the Windsor university school of Medicine.

After that, the newly minted doctor of medicine (MD) may choose to complete a three-year residency program in a specialty related to medical research, such as internal medicine, pediatrics, or neurology, in addition to a doctor of philosophy (PhD) degree—the part that provides the research expertise. In some medical school programs, students may pursue a dual MD-PhD at the same time, which provides training in both medicine and research. They are specifically designed for those who want to become research physicians. Last but not the least, all physician-scientists must pass the first two steps of the United States Medical Learning Examination (USMLE).

Use your fellowship years to hone the research skills necessary to carry out independent research. You may also take courses in epidemiology, biostatistics, and other related fields. In order to publish your research in peer-reviewed journals to establish yourself as a medical researcher. To apply for a faculty position at a medical school, research institute, or hospital. To maintain your position as a medical research doctor, you must publish your research and make significant contributions to the field.

How Much Do Medical Researchers Make?

Having a clear idea of what to earn when you become a medical researcher can help you decide if this is a good career choice for you. The salaries of Medical Researchers in the US range from $26,980 to $155,180, with a median salary of $82,240. There is also room for career advancement and higher earning potential as you gain experience.

The Most Popular Careers in Medical Research

- Medical Scientists – conduct research and experiments to improve our understanding of diseases and to develop new treatments. They also develop new medical technologies and techniques.

- Biomedical engineers – design medical devices, such as pacemakers, prosthetics, and imaging machines. They also develop and improve existing medical technologies.

- Clinical Trial Coordinators – oversee and manage clinical trials, which test new drugs and treatments. They are responsible for recruiting participants, collecting and analyzing data, and ensuring the trial is conducted in compliance with ethical standards.

- Medical Laboratory Technicians – analyze bodily fluids and tissues to diagnose diseases and conditions. They perform tests using specialized equipment and techniques, and report results to physicians.

- Biostatisticians – collect statistics to analyze data and test hypotheses in medical research. They design and analyze clinical trials, and use statistical models to understand the causes and effects of diseases.

- Epidemiologists – study the causes, distribution, and control of diseases in populations. They collect and analyze data, and use their findings to develop strategies for preventing and controlling diseases.

- Pathologists – diagnose diseases by examining tissues and bodily fluids. They use microscopes and other diagnostic tools to identify and study the changes in tissues caused by disease.

- Genetic Counselors – help individuals understand and manage the risks associated with inherited genetic disorders. They educate patients about genetic tests and help families make informed decisions about their health.

- Health Services Researchers – study the delivery of healthcare and identify ways to improve it.

- Medical writers – write articles, reports, and other materials related to medical research.

- Microbiologists – study microorganisms, including bacteria and viruses, to understand their behavior and impact on human health.

- Neuroscientists – study the brain and nervous system to understand the underlying causes of neurological conditions.

- Toxicologists – study the effects of toxic substances on living organisms and the environment.

Skills You Need to Become a Medical Researcher?

To be a successful medical scientist, you need a range of soft and hard skills to excel in your work. First things first, medical researchers must be able to analyze data, identify patterns, and draw conclusions from their findings. They must be able to think critically, ask relevant questions, and design experiments to answer those questions. Additionally, you should also have the knack of articulating your findings clearly and effectively, be it writing research papers, grant proposals, or technical reports that are clear, concise, and free from errors.

Medical researchers must be proficient in using various computer programs and software to collect, manage, analyze and interpret research data. They must be able to use laboratory equipment and techniques, as well as statistical analysis software and other tools for data analysis. Since medical research involves precise and meticulous work, so you must also pay close attention to detail to ensure that your findings are accurate and reliable. Not to mention, medical researchers often work in teams, so it pays off if you are good at collaborating with others effectively, sharing ideas, and working together to solve complex problems.

Lastly, medical researchers must have a thorough understanding of regulations and ethical guidelines that govern research, such as obtaining informed consent from study participants, ensuring data confidentiality, and adhering to safety protocols.

Related posts

20 Best Resources to Help you Prepare for the MCAT

How to Become an ENT?

7 days of Mental Wellness Challenge for WUSOM Students

Start online application.

Latest Post

Most viewed.

Preparing for the MCAT is a big deal. With so much riding on your score, it’s essential to have the right resources to help you

If you ever notice any issues with functioning of the related organs such as nose, throat, ear, sinus, head or neck, you go to a specialist

It is no secret that medical education is a time wrought with personal and professional stressors, posing serious challenges to maintaining student wellness. Research shows

Follow us on Twitter

St. Kitts Campus Windsor University School of Medicine 1621 Brighton’s Estate, Cayon St. Kitts, West Indies Call: 1.844.994.6376 Email: [email protected]

U.S. Information Office Royal Medical & Technical Consultants Inc. Suite # 303 20646 Abbey Wood Ct. Frankfort, IL 60423 United States Call: 1 708 235 1940 Email: [email protected]

Copyrights © Windsor University School of Medicine 2024. All rights reserved.

Clinical Research

Graduate Program

The Master of Science in Clinical Research program is designed for early-career health care professionals including physicians, dentists, pharmacists, and nurses. They will explore epidemiology and biostatistics, and learn about decision sciences, applied omics science, and translating innovation into clinical practice.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Renaming of genera Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus to Orthoebolavirus and Orthomarburgvirus, respectively, and introduction of binomial species names within family Filoviridae

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Virology, Philipps-University Marburg, Marburg, Germany.

- 2 The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, TX, USA.

- 3 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA.

- 4 United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD, USA.

- 5 World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 6 Department of Virology, Immunology and Microbiology, Chobanian and Avedisian School of Medicine, National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA.

- 7 Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, Novosibirsk Oblast, Russia.

- 8 Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

- 9 Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Parasitic Diseases, National Institute for Communicable Diseases of the National Health Laboratory Service, Sandringham-Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa.

- 10 CBR Division, Dstl, Porton Down, Salisbury, Wiltshire, UK.

- 11 Division of Global Epidemiology, International Institute for Zoonosis Control, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan.

- 12 National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center, Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD, USA.

- 13 Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick (IRF-Frederick), Division of Clinical Research (DCR), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), B-8200 Research Plaza, Fort Detrick, Frederick, MD, 21702, USA. [email protected].

- PMID: 37537381

- DOI: 10.1007/s00705-023-05834-2

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Filoviridae Study Group continues to prospectively refine the established nomenclature for taxa included in family Filoviridae in an effort to decrease confusion of genus, species, and virus names and to adhere to amended stipulations of the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature (ICVCN). Recently, the genus names Ebolavirus and Marburgvirus were changed to Orthoebolavirus and Orthomarburgvirus, respectively. Additionally, all established species names in family Filoviridae now adhere to the ICTV-mandated binomial format. Virus names remain unchanged and valid. Here, we outline the revised taxonomy of family Filoviridae as approved by the ICTV in April 2023.

© 2023. This is a U.S. Government work and not under copyright protection in the US; foreign copyright protection may apply.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Guide to the Correct Use of Filoviral Nomenclature. Kuhn JH. Kuhn JH. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2017;411:447-460. doi: 10.1007/82_2017_7. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2017. PMID: 28653188 Review.

- ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Filoviridae 2024. Biedenkopf N, Bukreyev A, Chandran K, Di Paola N, Formenty PBH, Griffiths A, Hume AJ, Mühlberger E, Netesov SV, Palacios G, Pawęska JT, Smither S, Takada A, Wahl V, Kuhn JH. Biedenkopf N, et al. J Gen Virol. 2024 Feb;105(2):001955. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001955. J Gen Virol. 2024. PMID: 38305775 Free PMC article.