Evidence is clear on the benefits of legalising same-sex marriage

PhD Candidate, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University

Disclosure statement

Ryan Anderson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

James Cook University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Emotive arguments and questionable rhetoric often characterise debates over same-sex marriage. But few attempts have been made to dispassionately dissect the issue from an academic, science-based perspective.

Regardless of which side of the fence you fall on, the more robust, rigorous and reliable information that is publicly available, the better.

There are considerable mental health and wellbeing benefits conferred on those in the fortunate position of being able to marry legally. And there are associated deleterious impacts of being denied this opportunity.

Although it would be irresponsible to suggest the research is unanimous, the majority is either noncommittal (unclear conclusions) or demonstrates the benefits of same-sex marriage.

Further reading: Conservatives prevail to hold back the tide on same-sex marriage

What does the research say?

Widescale research suggests that members of the LGBTQ community generally experience worse mental health outcomes than their heterosexual counterparts. This is possibly due to the stigmatisation they receive.

The mental health benefits of marriage generally are well-documented . In 2009, the American Medical Association officially recognised that excluding sexual minorities from marriage was significantly contributing to the overall poor health among same-sex households compared to heterosexual households.

Converging lines of evidence also suggest that sexual orientation stigma and discrimination are at least associated with increased psychological distress and a generally decreased quality of life among lesbians and gay men.

A US study that surveyed more than 36,000 people aged 18-70 found lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals were far less psychologically distressed if they were in a legally recognised same-sex marriage than if they were not. Married heterosexuals were less distressed than either of these groups.

So, it would seem that being in a legally recognised same-sex marriage can at least partly overcome the substantial health disparity between heterosexual and lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons.

The authors concluded by urging other researchers to consider same-sex marriage as a public health issue.

A review of the research examining the impact of marriage denial on the health and wellbeing of gay men and lesbians conceded that marriage equality is a profoundly complex and nuanced issue. But, it argued that depriving lesbians and gay men the tangible (and intangible) benefits of marriage is not only an act of discrimination – it also:

disadvantages them by restricting their citizenship;

hinders their mental health, wellbeing, and social mobility; and

generally disenfranchises them from various cultural, legal, economic and political aspects of their lives.

Of further concern is research finding that in comparison to lesbian, gay and bisexual respondents living in areas where gay marriage was allowed, living in areas where it was banned was associated with significantly higher rates of:

mood disorders (36% higher);

psychiatric comorbidity – that is, multiple mental health conditions (36% higher); and

anxiety disorders (248% higher).

But what about the kids?

Opponents of same-sex marriage often argue that children raised in same-sex households perform worse on a variety of life outcome measures when compared to those raised in a heterosexual household. There is some merit to this argument.

In terms of education and general measures of success, the literature isn’t entirely unanimous. However, most studies have found that on these metrics there is no difference between children raised by same-sex or opposite-sex parents.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association released a brief reviewing research on same-sex parenting. It unambiguously summed up its stance on the issue of whether or not same-sex parenting negatively impacts children:

Not a single study has found children of lesbian or gay parents to be disadvantaged in any significant respect relative to children of heterosexual parents.

Further reading: Same-sex couples and their children: what does the evidence tell us?

Drawing conclusions

Same-sex marriage has already been legalised in 23 countries around the world , inhabited by more than 760 million people.

Despite the above studies positively linking marriage with wellbeing, it may be premature to definitively assert causality .

But overall, the evidence is fairly clear. Same-sex marriage leads to a host of social and even public health benefits, including a range of advantages for mental health and wellbeing. The benefits accrue to society as a whole, whether you are in a same-sex relationship or not.

As the body of research in support of same-sex marriage continues to grow, the case in favour of it becomes stronger.

- Human rights

- Same-sex marriage

- Same-sex marriage plebiscite

Educational Designer

Lecturer, Small Animal Clinical Studies (Primary Care)

Organizational Behaviour – Assistant / Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Apply for State Library of Queensland's next round of research opportunities

Associate Professor, Psychology

Same-sex marriage legalization associated with reduced implicit and explicit antigay bias

Downloadable content.

- Ofosu, Eugene

- Eric Hehman (Supervisor)

- The current research tested whether the passing of government legislation, signaling the prevailing attitudes of the local majority, was associated with changes in citizens’ attitudes. Specifically, with ~1 million responses over a 11-year window, we test whether state-by-state same-sex marriage legislation was associated with decreases in anti-gay implicit and explicit bias. Results across five operationalizations consistently provide support for this possibility. Both implicit and explicit bias were decreasing prior to same-sex marriage legalization, but decreased at a sharper rate following legalization. Moderating this effect was whether states passed legislation locally. While states passing state-level legislation experienced a greater decrease in bias following legislation, states that never passed local legislation demonstrated increased anti-gay bias following federal legalization. Our work highlights how government legislation can inform individuals’ attitudes, even when these attitudes may be deeply entrenched, and socially and politically volatile

- La recherche présente a testé si l’adoption par le gouvernement de lois reflétant l’avis d’une majorité de citoyens, est associée avec des changements d’attitude de citoyen(ne)s. Grâce à 1 million d’observations sur plus de 11 ans, nous avons examiné si la légalisation du mariage gai pour chaque état américain a été associée avec la diminution des préjugés homophobes implicites et explicites. Cinq modèles statistiques appuient fortement notre hypothèse. Bien que les préjugés implicites et explicites étaient en diminution avant la légalisation du mariage homosexuel, les deux types de préjugés ont diminué plus rapidement après. Cet effet était modéré par le pallier de gouvernement ayant mis en œuvre la légalisation. Spécifiquement, les états ayant adopté la légalisation au niveau de l’état ont vu une diminution des deux types de préjugés après la légalisation, tandis que ceux n’ayant pas légalisé le mariage gai au niveau de l’état ont vu une augmentation des préjugés après la légalisation au niveau fédéral. Notre recherche souligne comment les lois gouvernementales peuvent influencer les attitudes individuelles, même quand ces attitudes sont fortement enracinées et sujettes aux débats sociaux

- McGill University

- https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/xg94ht93x

- All items in eScholarship@McGill are protected by copyright with all rights reserved unless otherwise indicated.

- Department of Psychology

- Master of Science

- Theses & Dissertations

| Thumbnail | Title | Date Uploaded | Visibility | Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-03-23 | Public | |||

| 2020-05-04 | Public |

The Anti-Social Effects of Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage: Fact or Fiction?

- Published: 07 November 2020

- Volume 18 , pages 1060–1077, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Laura Langbein ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3899-1543 1 ,

- Brandon Ranallo-Benavidez 2 &

- Jane E. Palmer 3

711 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Introduction

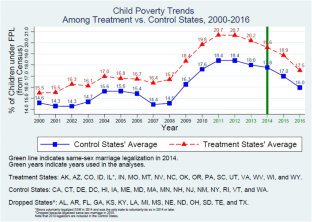

Previous research examines the effects of same-sex marriage on many child and family outcomes, but only a small subset examines the effects of laws on those outcomes. We evaluate the effects of same-sex marriage legalization in the USA on four socio-familial outcomes.

We use currently available public data from the U.S. Census and CDC to analyze changes in state-level legalization of same-sex marriage on rates of child poverty, divorce, marriage, and children living in single-parent households within each state from 2011 to 2016. The estimators use traditional cross-sectional time-series methodologies, along with adjusting for high-dimensional fixed-effects (HDFE) clustering to account for both spatial and temporal dependence of state-time observations.

We find no evidence to validate claims of negative ramifications from same-sex marriage legalization on these outcomes.

With respect to the arguments articulated in Supreme Court amici briefs, we show that assertions of negative social effects of legalized same-sex marriage are largely unsupported.

In addition to illustrating the gains from HDFE estimators, we conclude that warnings of likely negative effects from same-sex marriage, such as disallowing adoption by same-sex couples, are not credible.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Direct Effects of Legal Same-Sex Marriage in the United States: Evidence From Massachusetts

Legal recognition of same-sex couples and family formation.

On the magnitude, frequency, and nature of marriage dissolution in Italy: insights from vital statistics and life-table analysis

There are extensive discussions that critique (e.g., Marks, 2012 ) and defend the validity (e.g., Amato, 2012 ) of these studies. One major study that found negative impacts of same-sex parents on child outcomes (Regnerus, 2012 ) was criticized when a replication did not come to the same conclusion (Cheng & Powell, 2015 )

Louisiana, Utah, Texas, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and West Virginia (listed here in same order as listed on the legal brief).

In economics, non-price entry barriers (such as refusing to hire based on race or gender) are inefficient: they impose costs not only on the excluded group but also on consumers or employers, while conferring smaller benefits (higher wages) on the privileged group. There are no social benefits.

Considerable research shows that marriage in general benefits both the two parents and the children, partly due to scale economies along with more income. In addition to within family benefits, external benefits of marriage include reduced demand for many social services (e.g, welfare and other income supports; police) that might otherwise be required if there were more single-parent families. See Ribar ( 2015 ); Sawhill and Thomas ( 2005 ); Thomas and Sawhill ( 2002 ); Sawhill and Haskins ( 2016 ); McLanahan and Sawhill ( 2015 ); Zissimopoulos, Karney, and Rauer ( 2015 ).

The early adopter control states include the 2013 legalizers (CA, DE, HI, MD, MN, NJ, NM and RI) and the earliest adopters (MA, 2004; CT, 2008; IO, V, 2009; NH, DC, 2010; NY, 2011; ME, WA, 2012). The treated states, forced to adopt by Windsor (except IL, which voluntarily adopted after Windsor) include OR, ID, MT, WY, NV, UT, AZ, CO, OK, WI, IL, IN, PA, WV, VA, NC, and SC. Omitted states (the late legalizers, forced to legalize by Roe in 2015) include ND, SD, NE, KS, TX, MO, AR, LA, MI, OH, KY, TN, MS, AL, GA, FL)

However, as a robustness check, we also provide a secondary model specification that drops all states from our “control” group which did not have same-sex marriage for multiple years prior to 2014. The results in Tables 1 , 2, 3, and 4 do not change.

Note that Illinois was the only state post- Windsor to voluntarily legalize same-sex marriage.

For ease of interpretation, we use state-year levels in the dependent variables. However, because we use state fixed effects, the focal coefficient B represents the average within state difference in the dependent variable between treatment and control state (Ludwig & Cook, 2000 ); it is not a between state difference. As a robustness check, when we use difference-in-difference estimates of the relation between state-year changes in the policy adoption variable to state-year changes in dependent variables, along with the control variables and state fixed effects, the results do not change appreciably.

The SUR estimates show that the residuals are correlated:

Correlation matrix of residuals:

childpov divorce marriage sglpar

childpov 1.0000

divorce 0.0259 1.0000

marriage − 0.1606 0.5399 1.0000

sglpar 0.3548 0.0124 0.0768 1.0000

Breusch-Pagan test of independence: chi2(6) = 246.067, Pr = 0.0000.

We also estimated an xtreg with state-level fixed effects (Cameron & Trivedi, 2009 ; Wooldridge, 2010 ). Similar to Ludwig and Cook’s ( 2000 ) assessment of the Brady bill, we also performed a specification of ordinary least squares analysis with controls, heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors, and state and year fixed effect regressors. We do not show the results, but they do not differ from the results that we present.

Excluding 2013 legalizing states is a robustness check to provide a model where all the “control” states had same-sex marriage legalization for more than just 1 year. The results do not change.

These findings are robust to replacing rates in the dependent variables with log of rates. Neither the statistical nor substantive results changed. Data available upon request.

Opponents prefigured adverse effects of legalized same-sex marriage; therefore, we used directionally one-sided tests.

Adams, J., & Light, R. (2015). Scientific consensus, the law, and same sex parenting outcomes. Social Science Research, 53 , 300–310.

PubMed Google Scholar

Alabama (2015) http://sblog.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/14-556_State_of_Alabama.pdf .

Allen, D. W. (2006). An economic assessment of same-sex marriage laws. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, 29 (3), 949–980.

Google Scholar

Allen, D. W. (2010). Who should be allowed into the marriage franchise? Drake Law Review, 58 , 1043–1079.

Allen, D. W. (2013). High school graduation rates among children of same-sex households. Review of Economics of the Household, 11 , 635–658.

Allen, D. W., & Price, J. (2015). Same-sex marriage and negative externalities: A critique, replication, and correction of Langbein and Yost. Econ Journal Watch, 12 (2), 142–160.

Amato, P. (2012). The well-being of children with gay and lesbian parents. Social Science Research, 41 (4), 771–774.

American College of Pediatricians, Family Watch International, Marks, L. D., Regnerus, M. D., Sullins, D. P. (2015). Amici curiae brief supporting respondents, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Anderson, R. (2013). Marriage: What it is, why it matters, and the consequences of redefining it . Washington DC: The Heritage Foundation.

Badgett, M., Nezhad, S., Waaldijk, C., & van der Meulen, R. (2014). The 962 relationship between LGBT inclusion and economic development: 963 An analysis of emerging economies . Washington DC: US Agency 964 for International Development & The Williams Institute.

Biblarz, T., & Stacey, J. (2010). How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 72 (1), 3–22.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2011). Robust inference with multiway clustering. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 29 (2), 238–249.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics using stata . College Station: STATA Press.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2010). Microeconomics using Stata . College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Casper, L. M., McLanahan, S. S., & Garfinkel, I. (1994). The gender-poverty gap: What we can learn from other countries. American Sociological Review, 59 (4), 594–605.

Cere, D., & Farrow, D. (2004). Divorcing marriage: Unveiling the dangers in Canada’s new social experiment . Montreal, Ontario: The Institute for the Study of Marriage, Law and Culture.

Chen, W. H., & Corak, M. (2008). Child poverty and changes in child poverty. Demography, 45 (3), 537–553.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cheng, S., & Powell, B. (2015). Measurement, methods, and divergent patterns: Reassessing the effects of same-sex parents. Social Science Research, 52 , 615–626.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66 (4), 848–861.

Cherlin, A. J. (2009). The marriage go-round . New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Chinni, D. (2004). Is the post-election red tinge a mandate? Don’t bet on it. Christian Science Monitor. https://www.csmonitor.com/2004/1104/p09s01-codc.html .

Cohen, L. R., & Wright, J. D. (2011). Research handbook on the economics of family law . Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Correia, S. (2017a). REGHDFE: Stata module for linear and instrumental-variable/GMM regression absorbing multiple levels of fixed effects. Boston, MA: Statistical software components, Boston College Department of Economics. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/ s457874.html .

Correia, S. (2017b). A feasible estimator for linear models with multi-way fixed effects. (working paper). http://scorreia.com/research/hdfe.pdf .

Dao, J. (2004, November). 4 . New York Times: Same-sex marriage issue key to some GOP races https://www.nytimes.com/2004/11/04/politics/campaign/samesex-marriage-issue-key-to-some-gop-races.html .

Dillender, M. (2014). The death of marriage? The effects of new forms of legal recognition on marriage rates in the United States. Demography, 51 , 563–585.

Dinno, A. (2014). Comment on “The effect of same-sex marriage laws on different-sex marriage: Evidence from the Netherlands.”. Demography, 51 , 2343–2347.

Ellis, B. J., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., Pettit, G. S., & Woodward, L. (2003). Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual activity and teenage pregnancy? Child Development, 74 (3), 801–821.

Family Equality Council. (2018). Joint Adoption Law. https://www.familyequality.org/get_informed /resources/equality_maps/joint_adoption_laws/ .

Family Research Council. (2015). Amicus curiae brief supporting respondents and affirmance, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Felter, C., & Renwick, D. (2019). Same-sex marriage: Global comparisons. Council on Foreign Relations . https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/same-sex-marriage-global-comparisons .

Flouri, E. (2007). Fathering and adolescents’ psychological adjustment: The role of fathers’ involvement, residence and biology status. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34 (2), 152–161.

Flouri, E., & Buchanan, A. (2003). The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. Journal of Adolescence, 26 , 63–78.

Frank, N., Weeden, K., & Baker, K. (2018). What does the scholarly research say about the well-being of children with gay or lesbian parents? Ithaca, NY: Center for Study of Inequality. https://whatweknow.inequality.cornell.edu/topics/lgbt-equality/what-does-the-scholarly-research-say-about-the-wellbeing-of-children-with-gay-or-lesbian-parents/ .

Gallup (2019). Support for gay marriage stable. https://news.gallup.com/ poll/257705/suupport-gay-marriage -stable.aspx.?version=print.

Giddens, A. (1992). The transformation of intimacy: Sexuality, love, and eroticism in modern societies . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Goings, R. B., & Ford, D. Y. (2017). Investigating the intersection of poverty and race in gifted education journals: A 15-year analysis. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62 (1), 25–36.

Goodfriend, M. (1992). Information-aggregation bias. The American Economic Review, 82 (3), 508–519.

Harper, C. C., & McLanahan, S. S. (2004). Father absence and youth incarceration. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14 (3), 369–397.

Hawkins, A. J., & Carroll, J. S. (2015). Beyond the expansion framework: How same-sex marriage changes the institutional meaning of marriage and heterosexual men’s conception of marriage. Ave Maria Law Review, 13 (2), 219–235.

Herek, G. (2006). Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: A social science perspective. American Psychologist, 61 (6), 607–621.

Langbein, L., & Lichtman, A. (1976). Across the great divide: Inferring individual level behavior from aggregate data. Political Methodology, 3 (4), 411–439.

Langbein, L., & Yost Jr., M. A. (2009). Same-sex marriage and negative externalities. Social Science Quarterly, 90 (2), 292–308.

Lerman, R. I. (1996). The impact of the changing U.S. family structure on child poverty and income inequality. Economica, 63 (250), S119–S139.

Lewis, G. B. (2005). Same-sex marriage and the 2004 presidential election. PS: Political Science and Politics, 38 (2), 195–199.

Lichter, D. T., & Crowley, M. L. (2004). Welfare reform and child poverty: Effects of maternal employment, marriage, and cohabitation. Social Science Research, 33 (3), 385–408.

Louisiana, Utah, Texas, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and West Virginia. (2015). Amici curiae brief supporting respondents, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Ludwig, J., & Cook, P. J. (2000). Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady handgun violence prevention act. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284 (5), 585–591.

Manning, W. D., Feltro, M. N., & Lamidi, E. (2014). Child well-being in same-sex parent families: Review of research prepared for American Sociological Association amicus brief. Population Research & Policy Review, 33 (4), 485–502.

Manning, W. D., & Lamb, K. A. (2003). Adolescent well-being in cohabiting, married, and single-parent families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65 , 876–893.

Marks, L. (2012). Same-sex parenting and children’s outcomes: A closer examination of the American Psychological Association’s brief on lesbian and gay parenting. Social Science Research, 41 (4), 735–751.

Marquardt, E. (2006). Between two worlds: The inner lives of children of divorce . New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Marquardt, E. (2010). The kids are not all right. Human Life Review, 36 (3), 113–115.

Marquardt, E., Glenn, N. D., & Clark, K. (2010). My daddy’s name is donor: A new study of young adults conceived through sperm donation. New York, NY: Institute for American Values. http://americanvalues.org/catalog/pdfs/Donor_FINAL.pdf

Masci, D., & DeSilver, D. (2019). A global snapshot of same-sex marriage. Pew Research Center . https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/21/global-snapshot-same-sex-marriage/ .

Masci, D., Sciupac, E., & Lipka, M. (2019). Gay marriage around the world. Pew Research Center: Religion and Public Life . https://www.pewforum.org/fact-sheet/gay-marriage-around-the-world/ .

McLanahan, S., & Sawhill, I. (2015). Marriage and child wellbeing revisited: Introducing the issue. The Future of Children, 25 (2), 3–9.

Meezan, W., & Rauch, J. (2005). Gay marriage, same-sex parenting, and America's children. The Future of Children, 15 (2), 97–115.

Members of the Kentucky General Assembly. (2015). Amici curiae brief supporting respondents, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Murray, C. (2013). Coming apart: The state of white America, 1960–2010 . New York, NY: Crown Forum.

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 (US Supreme Court, 2015). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-556_3204.pdf .

Otter, C. L. (2015). Amici curiae brief, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Posner, R. A. (1973). Economic analysis of law . New York, NY: Little, Brown and Co..

Potter, D. (2012). Same-sex parent families and children’s academic achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74 , 556–571.

Public Religion Research Institute. (n.d.) The American Values Atlas. http://ava.prri.org/home#lgbt/2017/states/lgbt_ssm .

Pujol, J. (2016). The United States safe space campus controversy and the paradox of freedom of speech. Church, Communication and Culture, 1 (1), 240–254.

Regnerus, M. (2012). How different are the adult children of parents who have same-sex relationships? Findings from the new family structures study. Social Science Research, 41 (4), 752–770.

Republican National Convention Committee. (2015). Amicus curiae brief supporting respondents, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Ribar, D. (2015). Why marriage matters for child wellbeing. The Future of Children, 25 (2), 11–27.

Riggle, E., Rostosky, S., & Horne, S. (2010). Psychological distress, well-being, and legal recognition in same-sex couple relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 24 (1), 82–86.

Romaniuc, R. (2016). What makes law change behavior? An experimental study. Review of Law & Economics, 12 (2), 447–475.

Sawhill, I., & Haskins, R. (2016). The decline of the American family: Can anything be done to stop the damage? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 667 (1), 8–34.

Sawhill, I., & Thomas, A. (2005). For love and money? The impact of family structure on family income. The Future of Children, 15 (2), 57–74.

Scholars. (2015). Amici curiae brief supporting respondents and affirmance, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Scholars of Marriage. (2015). Amici curiae brief supporting respondents, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Texas Values. (2015). Amicus curiae supporting respondents, Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S. Ct. 2584.

Thomas, A., & Sawhill, I. (2002). For richer or for poorer: Marriage as an anti-poverty strategy. Journal for Policy Analysis and Management, 21 (4), 587–599.

Trandafir, M. (2014a). The effect of same-sex marriage laws on different-sex marriage: Evidence from the Netherlands. Demography, 51 , 317–340.

Trandafir, M. (2014b). Reply to comment on “The Effect of Same-Sex Marriage Laws on Different-Sex Marriage: Evidence from the Netherlands”. Demography, 51 , 2349–2350.

Trandafir, M. (2015). Legal recognition of same-sex couples and family formation. Demography, 52 , 113–151.

United States v. Windsor, 570 US 744 (2013).

Voss, P. R., Long, D. D., Hammer, R. B., & Friedman, S. (2006). County child poverty rates in the US: A spatial regression approach. Population Research and Policy Review, 25 (4), 369–391.

Wardle, L. D. (2001). Multiply and replenish: Considering same-sex marriage in light of state interests in marital procreation. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, 24 (3), 771–814.

Wardle, L. D. (2007). The fall of marital family stability and the rise of juvenile delinquency. Journal of Law & Family Studies, 10 (2), 83–110.

Wax, A. L. (2007). Engines of inequality: Class, race, and family structure. Family Law Quarterly, 41 (3), 567–599.

Wax, A. L. (2009). Review: The family law doctrine of equivalence. Michigan Law Review, 107 (6), 999–1017.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross-section and panel data . Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Yancey, G. (2011). Compromising scholarship: Religious and political bias in American higher education . Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

Young, K. K., & Nathanson, P. (2007). Redefining marriage or deconstructing society: A Canadian case study. Journal of Family Studies, 13 , 133–178.

Zissimopoulos, J. M., Karney, B. R., & Rauer, A. J. (2015). Marriage and economic well-being at older ages. Review of the Economics of the Household, 13 , 1–35.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Administration & Policy, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Kerwin Hall, Washington, DC, 20016, USA

Laura Langbein

Department of Political Science, Winthrop University, Rock Hill, SC, USA

Brandon Ranallo-Benavidez

Department of Justice, Law & Criminology, American University, Washington, DC, USA

Jane E. Palmer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Laura Langbein .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Research Involving Human Data

This is an observational study that uses publicly available aggregate data on humans. Specifically, as noted in the abstract of the manuscript, “we use currently available public data from the U.S. Census and CDC to analyze changes in state-level legalization of same-sex marriage on rates of child poverty, divorce, marriage, and children living in single-parent households within each state from 2011 to 2016.”

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Langbein, L., Ranallo-Benavidez, B. & Palmer, J.E. The Anti-Social Effects of Legalizing Same-Sex Marriage: Fact or Fiction?. Sex Res Soc Policy 18 , 1060–1077 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00509-y

Download citation

Accepted : 27 October 2020

Published : 07 November 2020

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00509-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Same-sex marriage

- Socio-familial outcomes

- High-dimensional fixed-effects

- Multi-way clustering

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Last updated 10th July 2024: Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > Law & Social Inquiry

- > Volume 48 Issue 2

- > Same-sex Marriage Legalization and the Stigmas of LGBT...

Article contents

Introduction, the stigmas of unmarried and “unnatural” parenting before the 748 act, the 748 act as stigma cure and catalyst, same-sex marriage legalization and the stigmas of lgbt co-parenting in taiwan.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 September 2022

In 2019, Taiwan became the first country in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage. Celebrated as a victory for global lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights, Taiwan’s 2019 law privileges marriage and biological parent-child ties as the foundation for LGBT family rights and (co-)parental recognition. This article contributes to sociolegal debates about the benefits and limitations of marriage equality by asking how restrictive legal approaches to legitimating LGBT parenthood may harm LGBT families, with consequences both for families ostensibly protected under the new laws and for those denied newly bestowed rights and protections. Drawing from legal and ethnographic research on Taiwan’s same-sex marriage law and the family formation strategies of Taiwanese LGBT parents, we interrogate how marriage equality interacts with related legal domains and prevailing stigmas of illegitimacy, adoption, and homosexuality in Taiwan. Encoded in, and reproduced through, the substance and implementation of law, these stigmas narrow the scope of legal rights and foster potentially discriminatory forms of recognition. The article shows how progressive laws may reduce LGBT family stigma for some, while also creating new stigma interactions that devalue diverse forms of LGBT parenthood.

On May 24, 2017, Taiwan’s Constitutional Court rendered a landmark decision that declared it unconstitutional to deny same-sex couples the freedom to marry. Footnote 1 Two years later, facing the deadline imposed by the court decision, the legislature passed the Act for Implementation of J.Y. Interpretation no. 748 (748 Act), granting same-sex couples the right to register a marriage and allowing stepparent adoption of a same-sex spouse’s biological child. Footnote 2 The 748 Act was celebrated widely as a “first in Asia” and a victory for global lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights (Haynes Reference Haynes 2019 ; L. Kuo Reference Kuo 2019 ). Yet the 748 Act is only one step in efforts to secure a broad range of LGBT rights in Taiwan that protect diverse family forms, intimate relationships, and gender and sexual identities.

The emphasis on marriage equality in LGBT-rights movements worldwide has sparked debates about the consequences of privileging the right to marry. Certainly, many LGBT couples have married once it became legally possible to do so in their jurisdictions, and they enjoy considerable benefits as a result. Nonetheless, some scholars and activists caution that legal marriage falls short of resolving all inequalities and forms of discrimination faced by LGBT couples and families (Bernstein and Taylor Reference Bernstein, Taylor, Bernstein and Taylor 2013 ; Murray Reference Murray 2016 ; Polikoff Reference Polikoff and Carlos 2016 ). Some argue that the focus on LGBT marriage rights glorifies marriage and delegitimizes non marital relationships (Warner Reference Warner 1999 ; Duggan Reference Duggan 2004 ; Strauss Reference Strauss 2018 ), potentially deepening exclusions from core citizenship rights that are mediated through marriage and intersecting structural inequalities (Patton-Imani Reference Patton-Imani 2020 ). Others point to non-US legal contexts that locate dignity not in the marital institution itself but, rather, in the “autonomy to choose whether to marry,” legally recognizing multiple intimate relationship options deserving of respect (Lau Reference Lau 2017 , 2618; Cahn and Carbone Reference Cahn and Carbone 2019 ). Looking beyond marriage to parental rights, legal scholars such as Nancy Polikoff ( Reference Polikoff and Carlos 2016 , 141) caution against the “misleading focus on marriage equality as the way to recognize a child’s two parents.” Douglas NeJaime ( Reference NeJaime 2016 , 1265; emphasis in original), by contrast, contends that marriage equality potentially destabilizes family norms that privilege biological, hetero-gendered parenting and that thereby “constrict familial possibilities for all families , both in and out of marriage” (see also Joslin Reference Joslin 2016 , Reference Joslin 2018 ). NeJaime’s ( Reference NeJaime 2018 , 34) more sanguine assessment of marriage equality’s transformative effects, which he later termed “transformation through assimilation,” rests on the US legal context where same-sex parental rights preceded marital rights and where some states have recognized intentional and functional parenthood principles in both marital and non marital relationships.

This article contributes to sociolegal debates about the benefits and limitations of marriage equality by focusing on the Taiwan case where legal marriage constitutes the foundation for LGBT family rights and (co-)parental recognition. We ask how narrow legal approaches to legitimating LGBT parenthood that privilege marital status and biological parenthood may harm LGBT families, with consequences both for families ostensibly protected under the new laws and for those excluded from newly bestowed rights and protections. We argue that stigma is a key mechanism for producing such harms. Stigmatization functions subtly and explicitly to delegitimize non-normative intimacies and families. Both encoded in, and reproduced through, the substance and implementation of law, stigma narrows how law grants rights and recognition, and it limits the form that such rights take. Inspired by developments in theories of stigma since Erving Goffman’s ( Reference Goffman 1963 ) classic study, we examine how law and stigma interact to generate both symbolic and substantive harms that devalue marked groups (Dowd Reference Dowd 1997 ) or exclude them altogether from the law’s protections (Patton-Imani Reference Patton-Imani 2020 ). Without denying the power of stigma to foster social prejudice and internalized shame, we nonetheless emphasize stigma’s structural origins and effects (Fiske Reference Fiske, Gilbert, Fiske and Lindzey 1998 ; Link and Phelan Reference Link and Phelan 2001 ), drawing attention to how hierarchies of sexual and gendered legitimacy permeate legal categories, modes of recognition, and implementation mechanisms, even in marriage equality laws designed to redress discrimination. In short, stigmas against non-normative families are enacted and reproduced through law in sometimes unexpected ways (Abrams Reference Abrams 2015 ; Robertson Reference Robertson 2015 ). Although legal changes may enable some LGBT families to resist stigma, such laws may simultaneously stigmatize in new ways that harm those whose family-formation strategies and identities remain unprotected by heteronormative legal frameworks.

Taiwan’s legal system is deeply heteronormative in orientation, entrenched in sociolegal principles that privilege marriage, “natural” biological reproduction, and patrilineal descent. Given this prevailing legal orientation, we examine the 748 Act’s consequences for diverse ways of becoming or being recognized as a (co-)parent. We argue that the Act, despite its overarching aim of redressing inequality, interacts with related domains of family, adoption, and household registration law to reproduce existing stigmas against non-normative families and create new forms of stigmatization for LGBT parents. Closely attuned to the complex interactions among different legal domains and types of stigma, our analysis interrogates three interacting stigmas prevalent in Taiwan: the stigma of non-marital birth (illegitimacy), non-biological parenthood (adoption), and non-heterosexual identities and intimacies (homosexuality). We document how the stigmas of illegitimacy and adoption emerged first in cases of heterosexual parentage and adoption, how they became associated with the stigma of homosexuality for LGBT parents unable or unwilling to “cover” their sexuality (Yoshino Reference Yoshino 2006 ), and how the 748 Act simultaneously reaffirms and transforms long-standing stigmatization against non-normative parenthood. For instance, although many families benefit from the new legal entitlement to stepparent adoption, parents may simultaneously experience the demand that they marry first, adopt their “own child,” and agree to a parental fitness evaluation as deeply stigmatizing. Others face discriminatory exclusions due to the provisions of the 748 Act itself, its complex interactions with other laws, and how these legal interactions produce and entrench stigmas that LGBT parents themselves sometimes reaffirm as they seek new legal protections. In sum, we show how ostensibly progressive laws may reduce LGBT family stigma for some, while also producing stigmatizing effects that devalue LGBT parenthood and narrow the scope of legally recognizable family formation strategies.

A Note on Legal Context and Methodology

Unlike many countries in North America and Europe, Taiwan offered no options for LGBT co-parental rights before the 748 Act went into effect. Second-parent adoption has never been a legal option in Taiwan, and both stepparent adoption and joint adoption of a nonrelative child were denied to LGBT couples because the adopting parents had to be legally married. Although a LGBT couple might jointly care for their children, only the birth/biological parent or single adoptive parent enjoyed legal parental status. The co-parent could not make medical, financial, or educational decisions on the child’s behalf or claim the child as a dependent for tax or other purposes. Nor did the co-parent have any claim to the child should the legal parent deny access, become incapacitated, or die.

The substantive exclusions faced by LGBT co-parent families were materialized through the administrative legacies of Japanese colonialism and postwar authoritarian rule in Taiwan: the household registration system and national identification (ID) card. Together, these documentation systems have served as the basis for citizenship inclusion and the mechanism for establishing legal spousal or parental status (a birth certificate is required for registering a birth in the household registry, but it does not officially establish legal parentage). Every citizen must be part of a household registry, and every citizen aged fourteen or older is required to obtain a national ID card that includes personal information such as gender, parentage, marital status, spouse’s name, and a unique ID number. Prior to the 748 Act, Taiwan did not acknowledge citizens’ same-sex marriages performed abroad, nor could such couples register a marriage in Taiwan. Taiwan also did not recognize two same-sex parents listed on a birth certificate of a child born abroad either to a surrogate or a lesbian mother. Only the birth mother, biological father, or adoptive parent was able to register the child in the household registry as a single parent whose same-sex couple relationship or co-parenting status was unintelligible to the registry’s heteronormative categories. Put simply, the household registry channeled full citizenship rights exclusively through heterosexual marriage and parental status.

The 748 Act made a limited intervention in this restrictive legal landscape by granting some same-sex couples the right to register a marriage and by creating access to legal co-parentage only for couples that first married and then pursued stepparent adoption of one spouse’s biological child. It denied marriage rights to transnational same-sex couples in which the non-Taiwanese partner hailed from a country that did not recognize same-sex marriage. It also banned joint adoption of a nonrelative child by married same-sex couples, making Taiwan one of only two jurisdictions worldwide to legislate such an exclusion (Lau Reference Lau 2020 ). In short, the 748 Act denied shared parentage to couples unable to marry or without a biological child, and it limited the mechanism for pursuing co-parental rights to stepparent adoption, thereby likening a same-sex union to a subsequent heterosexual marriage that follows upon divorce or death of a previous spouse.

Despite privileging biological children in its narrow recognition of co-parental rights, the 748 Act made no change to the associated laws that restrict LGBT childbearing in the first place. For instance, Taiwan’s 2007 Assisted Reproduction Act limits assisted reproductive technology (ART) access exclusively to infertile, opposite-sex married couples. Footnote 3 To date, lesbians and gay men who desire biological children must travel abroad for costly ART treatment or pursue legally unprotected arrangements at home, such as donor insemination, contractual marriages, or informal surrogacy (surrogacy remains illegal in Taiwan). Lesbian mothers have utilized ART services in Thailand, Cambodia, Japan, the United States, Canada, and Australia, with destinations shifting in response to changing ART access regulations and costs. Gay fathers who seek to conceive through ART face the considerable expense of egg donation and surrogacy, coupled with restrictive laws that limit potential ART destinations. The legal protections for surrogacy in the United States enhance its popularity among those who can afford the high costs, with Thailand and Russia providing cheaper, but legally insecure, options. Overall, the resources required to engage successfully in international ART use place it out of reach for many. By ignoring the exclusionary consequences of unequal ART access in Taiwan, the 748 Act enhanced LGBT parenthood stigma through differential treatment in law (Chen Reference Chen 2019 b).

Our analysis builds collaboratively on our respective research concerning Taiwan’s legalization of same-sex marriage (Chen) and the family formation and recognition strategies of Taiwanese LGBT parents (Friedman). Throughout the article, we also refer to LGBT parents as gay and lesbian or tongzhi parents, the latter term of identification widely used by Chinese-speaking, LGBT communities. In addition to reviewing existing laws, adoption evaluation policies, and court adoption decisions involving heterosexual and LGBT families, Footnote 4 we derive our findings from participant observation and ethnographic interviews with LGBT parents, LGBT rights activists, social workers, and government officials. Our discussion of the 748 Act’s consequences draws primarily from taped interviews with sixty-three LGBT-parent families conducted from July 2017 to July 2020, representing gay fathers (one-third) and lesbian mothers (two-thirds) who became parents before the Constitutional Court decision, in the intervening period before the Act was passed, and after the Act went into effect. During the latter phase, we collected court documents from eleven same-sex stepparent adoption cases, all of which were ultimately approved, two following appeal (as of March 2022, 111 children had been adopted through same-sex stepparent adoption). Footnote 5 Given that these adoption documents are not publicly available and are shared only with the petitioners themselves (who agreed to share them with us), they provide valuable insights into how adoption gatekeepers assessed LGBT parenthood in this new legal domain.

Our interviewees ranged in age from their twenties to fifties, with the majority in their thirties and forties. They clustered primarily in western Taiwan’s urban and peri-urban areas, in communities they characterized along a spectrum from socially liberal to conservative. They hailed from a broad swath of Taiwan’s majority Han society (only a few were Indigenous), with rural and urban family backgrounds that varied by class, geographic locale, ethnic affiliation, and religious orientation. The vast majority had one to two children conceived through intentional childbearing that involved diverse ART strategies, self-insemination, or contractual marriage and reproductive arrangements. The remainder had children in prior heterosexual unions or adopted a nonrelative child. Many resided in two-parent, nuclear households, but others were single parents, had flexible living situations with same-sex partners, or lived with extended kin or hired caregivers who assisted with childcare. Interviews lasted from one to three hours and took place in homes and public spaces (parks, coffee shops, offices, and restaurants) across Taiwan. Repeat interviews and participant observation were conducted with a subset of interviewees. The article integrates insights from ethnographic and legal sources with sociolegal, anthropological, gender, and sexuality scholarship to illuminate how the specific provisions of the 748 Act interact with related legal domains to both reduce and reproduce existing stigmas, generating various forms of recognition, non-recognition, and misrecognition that may create symbolic and substantive harms for LGBT families.

In Taiwan, parenting outside of marriage or through adoption is widely seen as a stigmatized practice whose harms beset both heterosexual and tongzhi parents. Laws and courts have often remedied these stigmas for heterosexual parents by creating a privileged family unit with two, opposite-sex married parents. For LGBT parents before the 748 Act, however, the double stigma of illegitimacy and adoption combined with the stigma of homosexuality to deny their family legitimacy, devaluing their family status and blocking access to the rights and privileges enjoyed by “normative” families. Understanding how sexuality mediated the interacting stigmas of illegitimacy and adoption before the 748 Act will help us understand the Act’s contradictory effects on tongzhi couples’ struggles for legal co-parentage.

The law of legitimacy prevails in Taiwan by dividing children into two unequally valued groups according to their birth mother’s relationship with their biological father. The law affirms that procreation “should” take place within the institution of marriage, and it thereby stigmatizes non-marital children by labeling them as “illegitimate” or “non-marital.” Taiwanese law explicitly identifies illegitimacy with fatherlessness, enabling men to escape the costs of reproducing outside of marriage and creating both symbolic and material harms for the child: an illegitimate child is deemed socially inferior and is legally denied support and inheritance from the biological father. The stigmatization of illegitimacy is enhanced by the comparative “abnormality” of unwed motherhood and fatherlessness. Taiwan’s non-marital birth rate increased only slightly from 2.07 percent in 1990 to 3.83 percent in 2020, an incidence that reflects persistent social preferences for childbearing within marriage (Cheng and Yang Reference Cheng and Yang 2021 ). Footnote 6

Although illegitimacy is defined by family law, its stigma is enacted through interactions between family laws and Taiwan’s household registration law. An “illegitimate” child’s fatherlessness is materialized in the household registry and on the national identity card. Whereas access to information documented in the registry is limited to registry members or a legal party of concern, the information on the national ID is revealed on a daily basis as citizens use it to establish their identity for a wide range of mundane and official purposes. Illegitimacy manifests through the ID entry for a father’s name, which, prior to 2008, publicly circulated the shameful stigma of illegitimacy through the characters “father unknown.” Although the term has since been removed from official documents, the stigma of illegitimacy continues to be reenacted in daily life through the simple dash that now occupies the father’s name slot on the ID. Footnote 7

Heterosexual parents have two options to resolve or conceal the stigma of a non-marital birth. The first option is through the birth mother’s post-birth marriage to the biological father or to a man she claims is the biological father. The second option is paternal acknowledgment without marriage. A birth father can “legitimate” a child without marrying the mother by voluntarily acknowledging the child or by de facto acknowledgment through child support. A single mother can remain unmarried and legitimate her child through forcing the birth father to acknowledge the child, should she be able to prove paternity. Given the heteronormative orientation of Taiwanese society and the prevailing stigmatization of non-marital birth, family members and friends in some instances have agreed to serve as a fake husband or father to protect a child from the harm of illegitimacy, despite the risk of criminal prosecution. Taiwanese courts, like courts in the United States (Maldonado Reference Maldonado 2013 ), have acknowledged “illegitimacy-as-harm” by finding that fatherlessness damages both the mother’s and the child’s reputations. In one case, the court permitted paternity establishment even after the putative father’s death to remedy the child’s many years of suffering. Footnote 8

Adoption provides another resource for heterosexual parents seeking to resolve the stigma of illegitimacy. Yet it bears its own stigma due to its association with infertility, abandonment, divorce, and abuse. Although Taiwanese law no longer distinguishes between an adoptive child and a “natural” child in most circumstances, societal norms devalue adoptive relationships as less authentic and “not natural,” a second-best alternative to create families (Chen and Chen Reference Chen and Chen 2017 ; see also March Reference March 1995 ). The social stigmatization of adoption is enhanced by the low overall adoption rate in Taiwan and the very small number of children available to adopt.

Taiwanese law permits three types of adoption to establish a parental relationship: adoption by a genealogically close blood relative, stepparent adoption, and adoption by a single person or married heterosexual couple who are not the child’s blood relatives. Stepparent and close-relative adoption constitute roughly 80 percent of all adoptions in Taiwan, with stepparent adoption being the most common category (Li, Qiu, and Bai Reference Li, Chin-hui and Li-fang 2017 , 279). Joint adoption of a nonrelative child is an entitlement reserved and mandated for married heterosexual couples only. Footnote 9 Consequently, a married person cannot adopt as a single person, and two unmarried persons cannot jointly adopt a child. Understood this way, adoption law resembles the law of legitimacy by privileging heterosexual marriage and excluding tongzhi couples and all unmarried couples from legitimating a two-parent adoptive family.

Taiwan’s current adoption law requires court intervention and designated roles for adoption agencies and social workers to establish a legal adoptive relationship. A minor’s adoption must be decided according to the “best interests of the child,” a vague principle shot through with gendered ideologies that endorse heteronormative family roles and responsibilities (Fineman Reference Fineman 1995 ; Richman Reference Richman 2009 ; Scott and Emery Reference Scott and Emery 2014 ; Chen Reference Chen 2016 ). Adoption gatekeepers may apply this principle in ways that stigmatize parents as “unfit,” an outcome that potentially besets both heterosexual and LGBT adoptive parents (Richman Reference Richman 2009 , 77). But the two groups face different challenges during the adoption process given its orientation toward ensuring an “ideal” heterosexual co-parenthood.

Two evaluation metrics for parental fitness in heterosexual stepparent adoptions are relevant for comparison with LGBT stepparent adoption in the post-748 Act era. Social workers use marital duration to assess the stability of the couple’s relationship and the likelihood that they will provide a lasting family environment for the child. Footnote 10 Although social workers generally rely on a baseline of two years for this evaluation metric, some courts have approved a shorter marital duration when coupled with premarital cohabitation or a positive assessment of the child’s interaction with the adopting parent. Statistics on approved heterosexual stepparent adoption cases from 2012–17 confirm considerable variation in how this metric is applied: 18.5 percent of couples had been married for less than six months at the time of adoption, 19.6 percent for between six months and one year, 24.2 percent for one to three years, and 15.4 percent for three to six years. Footnote 11 Thus, despite social workers’ emphasis on marital stability, the courts do not appear to set a high bar when it comes to heterosexual couples petitioning for stepparent adoption.

A second parental fitness criterion is the adoptive parents’ willingness to disclose the adoption given a child’s constitutional right to know their familial origins. The working assumption behind the disclosure assessment is that the adoption will otherwise be kept secret, a not unreasonable position given Taiwanese preference for closed adoption and heterosexual stepparents’ general unwillingness to disclose the adoption (Li, Qiu, and Bai Reference Li, Chin-hui and Li-fang 2017 ). Despite disclosure expectations, courts have approved heterosexual stepparent adoption in cases where the adoptive parent was reluctant or even refused to disclose the child’s origins but had established a stable relationship with the child, arguing that approving the adoption was still in the child’s best interest. In other cases, the court approved the adoption but ordered the adopter to receive education on adoption disclosure and to prepare a plan. These outcomes suggest that this parental fitness metric is not a determining factor for courts when approving an adoption that will legitimate the status quo by providing the child with a marital heterosexual family. Educating parents on the merits of disclosure is considered more desirable than rejecting the adoption petition altogether.

For heterosexual parents, therefore, stepparent adoption enables them to cure the stigma of illegitimacy and potentially to conceal the stigma of adoption. Again, the information about one’s parents on personal legal documents contributes to activating or avoiding stigma. In the past, adoption was noted on one’s household registration and national ID card, and an adoptive parent was identified by adding the character “adoptive” to the character for mother or father. Only in 1995 did the government permit heterosexual adoptive parents to conceal the adoptive relationship in their household registry by requesting removal of the “adoptive” character, an option that has since been made automatic with legal amendments that bar its inclusion in the household registry and on the child’s national ID card. By concealing the adoptive relationship in personal legal documents, the amended law aided heterosexual parents who wished to pass as “natural” by covering the adoption and enabling an adopted child to pass as a natural child.

In the pre-748 Act era, tongzhi co-parents did not face the same stigma of adoption because they were denied access to legal co-parentage through either joint or stepparent adoption. They could only adopt as a single person, ostensibly without regard to sexual orientation. A few successfully navigated the legal availability of single adoption without concealing their identity as transgender or tongzhi. As early as 2001, a Taiwan court approved a trans woman’s adoption petition, and, in 2014, an openly lesbian woman successfully petitioned for adoption (Wang, Hsu, and Ilu Reference Wang, Sen-jer and Hsiu-yi 2017 , 291–92). Yet the determination of the best interests of the child could easily discriminate against single adopters, and single stigma could also stand in for the stigmatization of homosexuality or non-normative gender, conflating marital status and sexual orientation discrimination to create significant barriers for tongzhi seeking to adopt.

An iconic adoption case in 2007 proved how high these adoption barriers were given Taiwan’s heteronormative sociolegal environment. A woman in a lesbian relationship petitioned to adopt her sister’s child as a single adopter, but the court rejected her petition on the basis that the child would be teased, bullied, and discriminated against as a result of the adoptive mother’s sexual orientation (otherwise known as the stigmatization argument). Footnote 12 As Helen Reece ( Reference Reece 1996 , 495–96) forcefully argues in her analysis of early British LGBT adoption cases, the stigmatization argument is flawed because it denies societal responsibility for creating a discriminatory environment and instead puts the burden of redressing potential bullying on the parent(s), thus justifying the court’s adoption denial. When lesbian mothers and gay fathers in the United States began to seek child custody through the courts in the late twentieth century, they rejected the logic of this argument, drawing on the US Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in Palmore v. Sidoti to argue, in some cases successfully, that social prejudice should play no role in custody decisions (Cain Reference Cain 2000 ). Footnote 13 Despite strong criticism of the stigmatization argument from Taiwan’s LGBT community and feminist legal scholars (Chen Reference Chen 2010 ; S. Kuo Reference Kuo 2010 ; Lin Reference Lin 2013 ), it became a recognized legal basis for rejecting subsequent LGBT co-parent adoption petitions (Jin and He Reference Jin and Shi-chang 2015 ).

In a series of pre-748 Act test cases in the mid-2010s, lesbian co-mothers who had conceived via ART abroad or donor insemination in Taiwan applied for stepparent adoption as de facto spouses. Although, as Nancy Polikoff ( Reference Polikoff 2009 , 205–6) argues, stepparent adoption is a poor fit for lesbian co-mothers who “plan for a child together,” these Taiwanese couples were willing to accept this poor fit to legitimate their families. Court after court rejected their claims, however, invoking both the stigmatization argument and judicial restraint (even after JY 748 was announced). Footnote 14 The courts argued that cohabiting tongzhi couples were treated the same as unmarried cohabiting heterosexual couples, ultimately finding that marriage, not heterosexuality, justified stepparent adoption.

Once again, the stigmatization argument worked against tongzhi parents even when they were willing to present themselves as de facto husband and wife for the court. Simply put, adoption as a cure to legitimate parenthood was denied for tongzhi co-parents but allowed for married heterosexual couples to resolve the stigma of illegitimacy. This differential treatment suggests that the stigma of homosexuality was so dominating that courts chose to ignore the stigma of illegitimacy or treat it as irrelevant to tongzhi families. From the courts’ point of view, adoption could cure the stigma of illegitimacy if it produced married, opposite-sex parents, but not if it resulted in two parents of the same sex.

The mixed record of tongzhi parents’ efforts to legitimate their families through adoption in the pre-748 Act era supports Kimberly Richman’s ( Reference Richman 2009 ) thesis that the indeterminacy of family law is a double-edged sword that can be used to pursue progressive goals or enforce bias against LGBT parents. The 748 Act advanced equality by granting legal recognition to some same-sex couples and family units. By creating a narrow path to legal co-parenting rights for LGBT couples, however, the Act established three key differences between LGBT and heterosexual parents: the requirement that marriage precede co-parentage recognition, the limiting of legal co-parentage only to couples with a biological child, and the designation of stepparent adoption as the sole mechanism for establishing co-parental rights. This section addresses each of these differences to examine how they generate discriminatory consequences through renewing intersecting stigmas surrounding illegitimacy, adoption, and homosexuality. Although we acknowledge that the 748 Act resolves the challenges faced by some LGBT families, we address new symbolic and substantive harms experienced by those covered by, and excluded from, the law’s limited protections.

The New Illegitimacy

By making same-sex marriage registration the precondition for legal co-parentage, the 748 Act creates a “new illegitimacy” for LGBT parents by privileging valued marital choices and marginalizing non-marital intimate bonds and family structures (Grossman Reference Grossman 2012 ; Murray Reference Murray 2012 ; Polikoff Reference Polikoff 2012 ). Footnote 15 In Taiwan, moreover, the marital demand has also revitalized the stigma of homosexuality by outing tongzhi parents socially and bureaucratically through the inclusion of a same-gender spouse’s name on their identification documents. When combined with the retention of the qualifying character “adoptive” for tongzhi stepparents only, this documentary treatment affirms how the new illegitimacy in Taiwan is defined by the stigma of homosexuality more than the racialized structural inequalities relevant to analyses of renewed illegitimacy stigmas in the United States: marriage remains “elusive or undesirable for many” (Murray Reference Murray 2012 , 436) through interactions between the 748 Act and Taiwan’s household registration laws and identification policies. Tongzhi parents must weigh the outing of their sexuality against the demand that they “opt in” to same-sex marriage registration before becoming eligible to petition for stepparent adoption. Legitimation as a family comes at a price—no state regulation/intervention, no recognition—but state recognition invites anew the stigma of homosexuality.

As discussed above, non-marital childbearing carries a broad social stigma across Taiwanese society. LGBT parents may themselves internalize the stigma of illegitimacy or may fear its anticipated effects on extended family members or in social or bureaucratic encounters. Many tongzhi parents described how their own parents expressed opposition to their childbearing plans because they were not married, ignoring the presence of their same-sex partner. The gendered dimensions of this opposition functioned differently for gay fathers and lesbian mothers due to societal anxieties about unmarried mothers and familial expectations that sons continue the patrilineal family line—in some instances, regardless of how they did so (Brainer Reference Brainer 2019 ). Gay fathers faced concerns about the child’s “lack” of a mother and a man’s ability to perform childcare that is traditionally gendered female (Boyer Reference Boyer and Rafael 2007 , 230); motherlessness in these cases functioned less as a marker of illegitimacy and more as a potential threat to the child’s well-being. Footnote 16 Intending mothers, on the other hand, experienced moral and social condemnation associated with unmarried pregnancy and their own parents’ anxieties about how a child’s fatherlessness would harm the family’s reputation through the stain of illegitimacy.

For some tongzhi parents, family members’ resistance to their childbearing plans reflects how the stigma of illegitimacy interacts with the stigma attached to homosexuality, creating exclusion from familial support networks that is enhanced by legal discrimination. A’mei, a birth mother who became pregnant before the 748 Act went into effect, related how her father had firmly opposed her plan to have a child together with her girlfriend due to her unmarried status, itself a consequence of the unrecognized standing of LGBT intimate relationships. Father-daughter relations grew so strained that A’mei did not visit her parents throughout her entire pregnancy and felt she could not count on their support when she gave birth. Thinking back on that period, A’mei admitted that she was lucky because the 748 Act went into effect two months before her daughter was born, and she married her partner immediately. “Otherwise, I would have been on my own [at the birth], with no one to sign documents for me or anything else.” A’mei’s father only softened his opposition and visited her once his granddaughter had entered the world. Footnote 17 Although A’mei’s experience attests to the legal and social benefits of same-sex marriage, it also affirms the significance of the child’s birth for prompting greater acceptance from senior generations.

Tongzhi parents who themselves endorse the stigma of illegitimacy may view the marital requirement as an additional tool to protect their children from societal discrimination. Some expecting couples in the pre-748 Act era held unofficial wedding ceremonies prior to a child’s birth to affirm their status as parents prepared to create a family. Footnote 18 The stigmatizing consequences of illegitimacy also appeared in some post-Act stepparent adoption petitions—for instance, two lesbian co-mother couples specifically wrote that stepparent adoption would protect their child from the stigma of “father unknown.” These couples used the 748 Act to legitimate their family by curing the stigma of fatherlessness without the presence of a father, revising the illegitimacy argument so that tongzhi couples could benefit from the destigmatizing effect of legal marriage enjoyed by their heterosexual counterparts. In so doing, however, these couples reaffirmed the concept of “illegitimacy as injury,” deploying a rights-seeking strategy that Polikoff ( Reference Polikoff 2012 , 722) critiques as a “win backwards” for reviving “the discredited distinction between ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ children.”

The “illegitimacy as injury” argument was widely used in the US movement for same-sex marriage and parental rights and was acknowledged in Obergefell v. Hodges , despite criticism from feminist legal scholars (Murray Reference Murray 2012 ; Polikoff Reference Polikoff 2012 , Reference Polikoff and Carlos 2016 ). Footnote 19 Yet it was not as prominent in Taiwan’s marriage equality movement, evidence of divisions within the tongzhi community over prioritizing legal marriage in rights struggles (Liu Reference Liu 2015 ; Lee Reference Lee 2017 ; Chen Reference Chen 2019 a, Reference Chen 2019 b; Ho Reference Ho 2019 ; Kuan Reference Kuan 2019 ). Despite recognizing the social and material value of marriage and intergenerational kinship in Taiwanese society (Chao Reference Chao 2005 ; Hu Reference Hu 2017 ; Brainer Reference Brainer 2019 ), tongzhi remain divided about whether marriage should precede parenting and legal co-parental rights. A 2016 survey found that roughly half of LGBT interviewees believed legal same-sex marriage should come before co-parental adoption, while one-third objected to requiring marriage as the first step (Child Welfare League Foundation 2017 , 23). This diversity of perspectives is reflected in the current marital landscape, where some LGBT parents resist or delay marrying, despite their desire for both partners to enjoy legal recognition as parents. Our interviews suggest that legal co-motherhood is currently more common than legal co-fatherhood, in part a reflection of a higher incidence of co-parenting among lesbian couples and in part, as discussed below, a consequence of the social and professional challenges faced by gay men who openly disclose their sexual orientation. This finding is also consistent with the fact that lesbian marriages have significantly outnumbered gay marriages since the 748 Act’s enactment in 2019. Footnote 20

Tingting, a well-educated, professional lesbian mother from central Taiwan, criticized the tongzhi community for upholding traditional norms that bonded childbearing to marriage. Yet, over the course of two in-depth interviews, Tingting gradually revealed her own ambivalent history of marriage. After Tingting became pregnant through reciprocal in-vitro fertilization (IVF) in Japan, she and her partner traveled to the United States in 2018 to marry and give birth to their son, a decision motivated partly by their desire for his birth certificate to include both of their names. The birth certificate was merely a symbolic statement of their shared parentage, however, for it, like their US marriage, lacked legal validity in Taiwan at the time. Although passage of the 748 Act allowed them finally to register their marriage in Taiwan, the couple had yet to do so even two years later, an outcome that Tingting attributed to mounting tensions in their couple relationship and opposition from her own parents. These challenges had deepened Tingting’s ambivalence about the value of marriage, despite her strong commitment to LGBT family rights and her partner’s parental recognition. Nonetheless, she acknowledged the stigma of her unmarried mother status, having been labeled as a “high risk family” by her local public health bureau because, on paper, she appeared to be a single mother and had failed to follow a regular immunization schedule for her toddler. Footnote 21

Tingting’s example represents a couple with choices, in that she and her partner could marry and embark on the stepparent adoption process if they so chose. Their concerns echo those of other parents who put off marrying to protect their intimate relationship from what they see as legal entanglements that potentially introduce competing interests and calculations into an otherwise emotional bond. Despite acknowledging how this decision has rendered their family vulnerable, such couples prefer to remain “strangers in law” rather than invite the state into their intimate lives, making the so-called “freedom to choose” a Faustian bargain for those profoundly uncertain about the emotional and social costs of state recognition (Patton-Imani Reference Patton-Imani 2020 ; Friedman and Chen Reference Friedman and Chen 2021 ). Footnote 22 Other couples assert that, by requiring marriage as a precondition for co-parental rights, the 748 Act diminishes the value of marriage itself by making it simply one more element that parents must acquire to legitimate their families. One adoptive co-mother made this very point when reflecting on the impact of her marriage: “Speaking honestly, our relationship is the same after marrying, nothing has changed. The benefit of marriage is that I could adopt [my son].” Footnote 23 Using the couple relationship to secure the co-parent’s legal relationship to the child effectively devalues both the parent-child bond and marriage, for neither has legal worth in itself (Polikoff Reference Polikoff 2009 ). As the 2016 survey of LGBT attitudes toward same-sex marriage shows, and interviews with tongzhi parents have confirmed, a significant proportion of parents might be unlikely to marry were it not required for the stepparent adoption process, despite the hard-fought struggle to win marriage rights.

By tethering parental rights to marriage, the 748 Act also affirms how basic citizenship claims are channeled through legal marriage, thereby creating fundamental inequalities for those unable to marry (Patton-Imani Reference Patton-Imani 2020 , 45). The 748 Act’s marital requirement disadvantages couples that feel incapable of exercising their legal right to marry (as opposed to reluctant) and denies core citizenship rights to those formally barred from marrying under the current law. Not only do these two groups experience different degrees of harm, but they also face different temporal horizons of exclusion extending from the denial of basic rights in the present to the potential future risk of parental vulnerability. This future risk is balanced against the more immediate consequences of having one’s sexuality made public by registering a marriage that will be noted in the household registry and on one’s national ID card and potentially reported to one’s workplace. Consequently, LGBT parents who are unable to marry continue to suffer the double stigma of illegitimacy and homosexuality.

Gay fathers predominate among parents who feel unable to marry despite being legally eligible. Gay men are more likely not to be fully out to their family of origin and thus fear the interpersonal, emotional, and, in some cases, financial consequences of being outed to their families once the marriage appears in the family’s household registration (if they have not established a separate registry) and their spouse’s name is added to their national ID card. Initially, a same-sex married couple’s household registration identified their union specifically as a “same-sex marriage,” but the government subsequently removed the term “same-sex” following objections that it violated privacy. Nonetheless, most tongzhi couples emphasized that the spouse’s name alone, by indicating gender, will out them to their families. Such concerns echo long-standing critiques of including marital status on the national ID card that underscore its unjustified invasion of privacy and potential to facilitate marital status discrimination. Although these critiques focused on heterosexual marriage, they suggest how this documentation makes some couples, especially gay men, more vulnerable to existing societal stigmas against homosexuality.

Ming was a thirty-something father of two children biologically related to his partner, James, who conceived through egg donation and surrogacy in the United States. Ming had kept his gay identity, relationship with James, and the children a secret from his parents and brother. Although both partners lived in Taipei, Ming resided with his parents during the week and spent the weekends with James and the children. Ming knew that marrying James would have the “added value” of enabling him to formalize his parental status through adoption, but he hesitated to come out to his mother after keeping his sexuality secret for so long, only doing so almost two years after the 748 Act went into effect. Footnote 24