- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- CME Reviews

- Best of 2021 collection

- Abbreviated Breast MRI Virtual Collection

- Contrast-enhanced Mammography Collection

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Accepted Papers Resource Guide

- About Journal of Breast Imaging

- About the Society of Breast Imaging

- Guidelines for Reviewers

- Resources for Reviewers and Authors

- Editorial Board

- Advertising Disclaimer

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Manisha Bahl, A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article, Journal of Breast Imaging , Volume 5, Issue 4, July/August 2023, Pages 480–485, https://doi.org/10.1093/jbi/wbad028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Scientific review articles are comprehensive, focused reviews of the scientific literature written by subject matter experts. The task of writing a scientific review article can seem overwhelming; however, it can be managed by using an organized approach and devoting sufficient time to the process. The process involves selecting a topic about which the authors are knowledgeable and enthusiastic, conducting a literature search and critical analysis of the literature, and writing the article, which is composed of an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion, with accompanying tables and figures. This article, which focuses on the narrative or traditional literature review, is intended to serve as a guide with practical steps for new writers. Tips for success are also discussed, including selecting a focused topic, maintaining objectivity and balance while writing, avoiding tedious data presentation in a laundry list format, moving from descriptions of the literature to critical analysis, avoiding simplistic conclusions, and budgeting time for the overall process.

- narrative discourse

Society of Breast Imaging members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| May 2023 | 171 |

| June 2023 | 115 |

| July 2023 | 113 |

| August 2023 | 5,013 |

| September 2023 | 1,500 |

| October 2023 | 1,810 |

| November 2023 | 3,849 |

| December 2023 | 308 |

| January 2024 | 401 |

| February 2024 | 312 |

| March 2024 | 415 |

| April 2024 | 361 |

| May 2024 | 306 |

| June 2024 | 283 |

| July 2024 | 309 |

| August 2024 | 126 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2631-6129

- Print ISSN 2631-6110

- Copyright © 2024 Society of Breast Imaging

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Credit: Getty

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

WENTING ZHAO: Be focused and avoid jargon

Assistant professor of chemical and biomedical engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

When I was a research student, review writing improved my understanding of the history of my field. I also learnt about unmet challenges in the field that triggered ideas.

For example, while writing my first review 1 as a PhD student, I was frustrated by how poorly we understood how cells actively sense, interact with and adapt to nanoparticles used in drug delivery. This experience motivated me to study how the surface properties of nanoparticles can be modified to enhance biological sensing. When I transitioned to my postdoctoral research, this question led me to discover the role of cell-membrane curvature, which led to publications and my current research focus. I wouldn’t have started in this area without writing that review.

Collection: Careers toolkit

A common problem for students writing their first reviews is being overly ambitious. When I wrote mine, I imagined producing a comprehensive summary of every single type of nanomaterial used in biological applications. It ended up becoming a colossal piece of work, with too many papers discussed and without a clear way to categorize them. We published the work in the end, but decided to limit the discussion strictly to nanoparticles for biological sensing, rather than covering how different nanomaterials are used in biology.

My advice to students is to accept that a review is unlike a textbook: it should offer a more focused discussion, and it’s OK to skip some topics so that you do not distract your readers. Students should also consider editorial deadlines, especially for invited reviews: make sure that the review’s scope is not so extensive that it delays the writing.

A good review should also avoid jargon and explain the basic concepts for someone who is new to the field. Although I trained as an engineer, I’m interested in biology, and my research is about developing nanomaterials to manipulate proteins at the cell membrane and how this can affect ageing and cancer. As an ‘outsider’, the reviews that I find most useful for these biological topics are those that speak to me in accessible scientific language.

Bozhi Tian likes to get a variety of perspectives into a review. Credit: Aleksander Prominski

BOZHI TIAN: Have a process and develop your style

Associate professor of chemistry, University of Chicago, Illinois.

In my lab, we start by asking: what is the purpose of this review? My reasons for writing one can include the chance to contribute insights to the scientific community and identify opportunities for my research. I also see review writing as a way to train early-career researchers in soft skills such as project management and leadership. This is especially true for lead authors, because they will learn to work with their co-authors to integrate the various sections into a piece with smooth transitions and no overlaps.

After we have identified the need and purpose of a review article, I will form a team from the researchers in my lab. I try to include students with different areas of expertise, because it is useful to get a variety of perspectives. For example, in the review ‘An atlas of nano-enabled neural interfaces’ 2 , we had authors with backgrounds in biophysics, neuroengineering, neurobiology and materials sciences focusing on different sections of the review.

After this, I will discuss an outline with my team. We go through multiple iterations to make sure that we have scanned the literature sufficiently and do not repeat discussions that have appeared in other reviews. It is also important that the outline is not decided by me alone: students often have fresh ideas that they can bring to the table. Once this is done, we proceed with the writing.

I often remind my students to imagine themselves as ‘artists of science’ and encourage them to develop how they write and present information. Adding more words isn’t always the best way: for example, I enjoy using tables to summarize research progress and suggest future research trajectories. I’ve also considered including short videos in our review papers to highlight key aspects of the work. I think this can increase readership and accessibility because these videos can be easily shared on social-media platforms.

ANKITA ANIRBAN: Timeliness and figures make a huge difference

Editor, Nature Reviews Physics .

One of my roles as a journal editor is to evaluate proposals for reviews. The best proposals are timely and clearly explain why readers should pay attention to the proposed topic.

It is not enough for a review to be a summary of the latest growth in the literature: the most interesting reviews instead provide a discussion about disagreements in the field.

Careers Collection: Publishing

Scientists often centre the story of their primary research papers around their figures — but when it comes to reviews, figures often take a secondary role. In my opinion, review figures are more important than most people think. One of my favourite review-style articles 3 presents a plot bringing together data from multiple research papers (many of which directly contradict each other). This is then used to identify broad trends and suggest underlying mechanisms that could explain all of the different conclusions.

An important role of a review article is to introduce researchers to a field. For this, schematic figures can be useful to illustrate the science being discussed, in much the same way as the first slide of a talk should. That is why, at Nature Reviews, we have in-house illustrators to assist authors. However, simplicity is key, and even without support from professional illustrators, researchers can still make use of many free drawing tools to enhance the value of their review figures.

Yoojin Choi recommends that researchers be open to critiques when writing reviews. Credit: Yoojin Choi

YOOJIN CHOI: Stay updated and be open to suggestions

Research assistant professor, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon.

I started writing the review ‘Biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells and bacteriophages’ 4 as a PhD student in 2018. It took me one year to write the first draft because I was working on the review alongside my PhD research and mostly on my own, with support from my adviser. It took a further year to complete the processes of peer review, revision and publication. During this time, many new papers and even competing reviews were published. To provide the most up-to-date and original review, I had to stay abreast of the literature. In my case, I made use of Google Scholar, which I set to send me daily updates of relevant literature based on key words.

Through my review-writing process, I also learnt to be more open to critiques to enhance the value and increase the readership of my work. Initially, my review was focused only on using microbial cells such as bacteria to produce nanomaterials, which was the subject of my PhD research. Bacteria such as these are known as biofactories: that is, organisms that produce biological material which can be modified to produce useful materials, such as magnetic nanoparticles for drug-delivery purposes.

Synchronized editing: the future of collaborative writing

However, when the first peer-review report came back, all three reviewers suggested expanding the review to cover another type of biofactory: bacteriophages. These are essentially viruses that infect bacteria, and they can also produce nanomaterials.

The feedback eventually led me to include a discussion of the differences between the various biofactories (bacteriophages, bacteria, fungi and microalgae) and their advantages and disadvantages. This turned out to be a great addition because it made the review more comprehensive.

Writing the review also led me to an idea about using nanomaterial-modified microorganisms to produce chemicals, which I’m still researching now.

PAULA MARTIN-GONZALEZ: Make good use of technology

PhD student, University of Cambridge, UK.

Just before the coronavirus lockdown, my PhD adviser and I decided to write a literature review discussing the integration of medical imaging with genomics to improve ovarian cancer management.

As I was researching the review, I noticed a trend in which some papers were consistently being cited by many other papers in the field. It was clear to me that those papers must be important, but as a new member of the field of integrated cancer biology, it was difficult to immediately find and read all of these ‘seminal papers’.

That was when I decided to code a small application to make my literature research more efficient. Using my code, users can enter a query, such as ‘ovarian cancer, computer tomography, radiomics’, and the application searches for all relevant literature archived in databases such as PubMed that feature these key words.

The code then identifies the relevant papers and creates a citation graph of all the references cited in the results of the search. The software highlights papers that have many citation relationships with other papers in the search, and could therefore be called seminal papers.

My code has substantially improved how I organize papers and has informed me of key publications and discoveries in my research field: something that would have taken more time and experience in the field otherwise. After I shared my code on GitHub, I received feedback that it can be daunting for researchers who are not used to coding. Consequently, I am hoping to build a more user-friendly interface in a form of a web page, akin to PubMed or Google Scholar, where users can simply input their queries to generate citation graphs.

Tools and techniques

Most reference managers on the market offer similar capabilities when it comes to providing a Microsoft Word plug-in and producing different citation styles. But depending on your working preferences, some might be more suitable than others.

Reference managers

Attribute | EndNote | Mendeley | Zotero | Paperpile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cost | A one-time cost of around US$340 but comes with discounts for academics; around $150 for students | Free version available | Free version available | Low and comes with academic discounts |

Level of user support | Extensive user tutorials available; dedicated help desk | Extensive user tutorials available; global network of 5,000 volunteers to advise users | Forum discussions to troubleshoot | Forum discussions to troubleshoot |

Desktop version available for offline use? | Available | Available | Available | Unavailable |

Document storage on cloud | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 300 MB (free version) | Storage linked to Google Drive |

Compatible with Google Docs? | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Supports collaborative working? | No group working | References can be shared or edited by a maximum of three other users (or more in the paid-for version) | No limit on the number of users | No limit on the number of users |

Here is a comparison of the more popular collaborative writing tools, but there are other options, including Fidus Writer, Manuscript.io, Authorea and Stencila.

Collaborative writing tools

Attribute | Manubot | Overleaf | Google Docs |

|---|---|---|---|

Cost | Free, open source | $15–30 per month, comes with academic discounts | Free, comes with a Google account |

Writing language | Type and write in Markdown* | Type and format in LaTex* | Standard word processor |

Can be used with a mobile device? | No | No | Yes |

References | Bibliographies are built using DOIs, circumventing reference managers | Citation styles can be imported from reference managers | Possible but requires additional referencing tools in a plug-in, such as Paperpile |

*Markdown and LaTex are code-based formatting languages favoured by physicists, mathematicians and computer scientists who code on a regular basis, and less popular in other disciplines such as biology and chemistry.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

How to win funding to talk about your science

Career Feature 15 AUG 24

Friends or foes? An academic job search risked damaging our friendship

Career Column 14 AUG 24

‘Who will protect us from seeing the world’s largest rainforest burn?’ The mental exhaustion faced by climate scientists

Career Feature 12 AUG 24

The need for equity in Brazilian scientific funding

Correspondence 13 AUG 24

Canadian graduate-salary boost will only go to a select few

A hike of postdoc salary alone will not retain the best researchers in low- or middle-income countries

Chatbots in science: What can ChatGPT do for you?

Why I’ve removed journal titles from the papers on my CV

Career Column 09 AUG 24

Scientists are falling victim to deepfake AI video scams — here’s how to fight back

Career Feature 07 AUG 24

Postdoctoral Fellow in Epigenetics/RNA Biology in the Lab of Yvonne Fondufe-Mittendorf

Van Andel Institute’s (VAI) Professor Yvonne Fondufe-Mittendorf, Ph.D. is hiring a Postdoctoral Fellow to join the lab and carry out an independent...

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Van Andel Institute

Faculty Positions in Center of Bioelectronic Medicine, School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

SLS invites applications for multiple tenure-track/tenured faculty positions at all academic ranks.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

School of Life Sciences, Westlake University

Faculty Positions, Aging and Neurodegeneration, Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine

Applicants with expertise in aging and neurodegeneration and related areas are particularly encouraged to apply.

Westlake Laboratory of Life Sciences and Biomedicine (WLLSB)

Faculty Positions in Chemical Biology, Westlake University

We are seeking outstanding scientists to lead vigorous independent research programs focusing on all aspects of chemical biology including...

Assistant Professor Position in Genomics

The Lewis-Sigler Institute at Princeton University invites applications for a tenure-track faculty position in Genomics.

Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, US

The Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

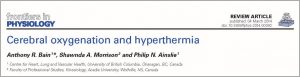

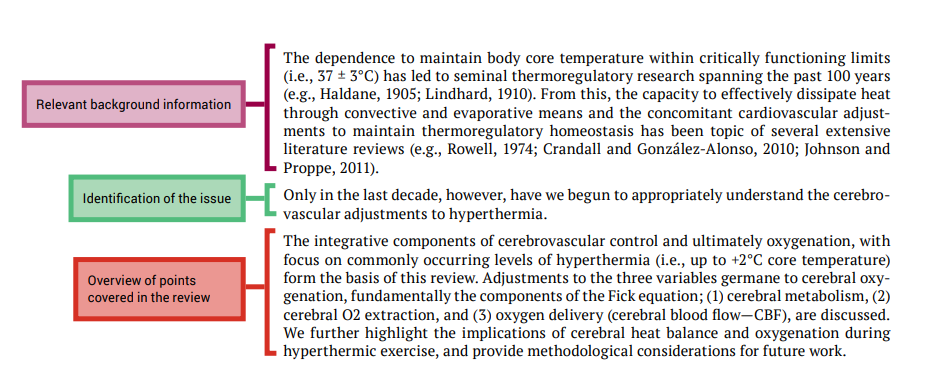

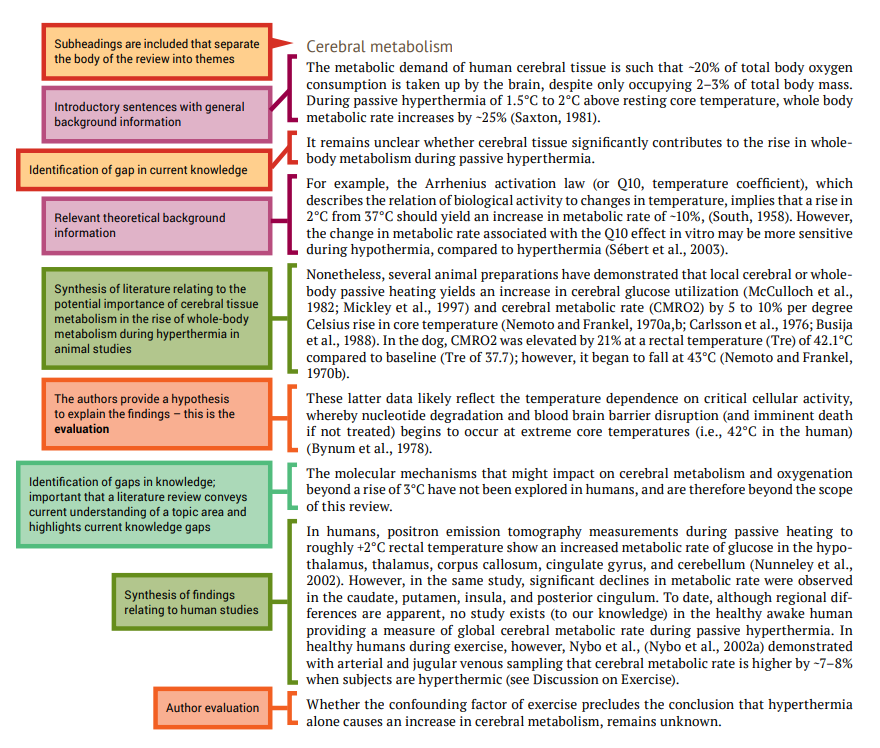

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

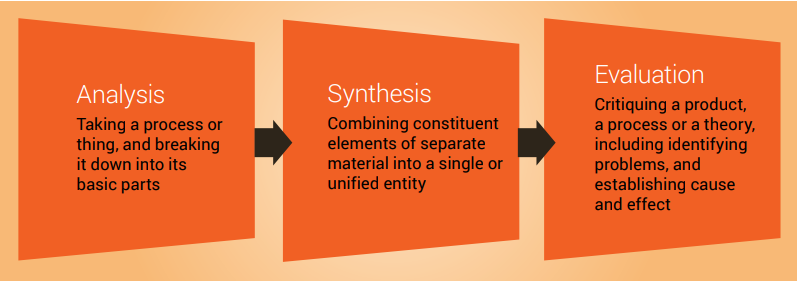

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

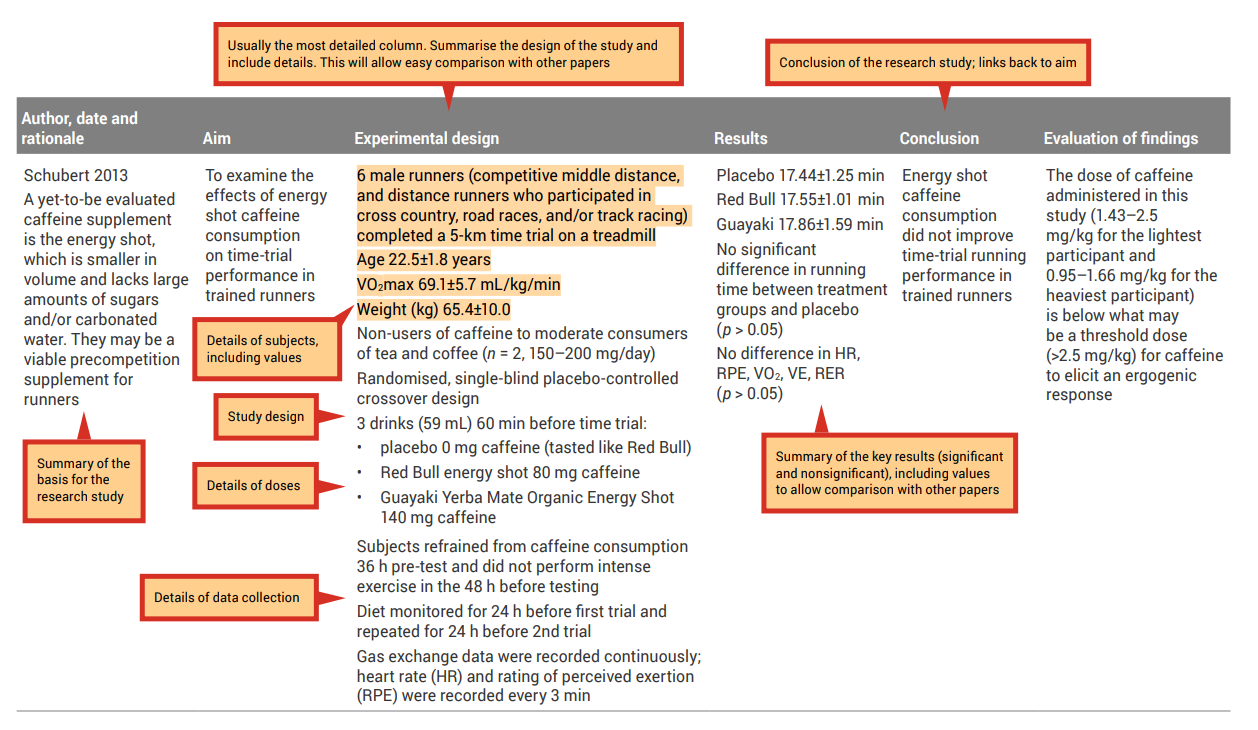

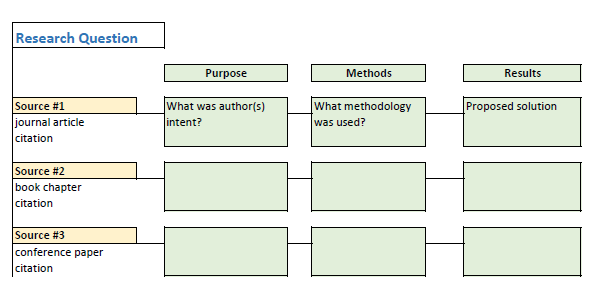

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

| [include details about the authors, date of publication and the rationale for the review] | [summarise the aim of the experiment] | [summarise the experiment design, include the subjects used and experimental groups] | [summarise the main findings] | [summarise the conclusion] | [evaluate the paper’s findings, and highlight any terms or physiology concepts that you are unfamiliar with and should be included in your review] |

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

| Ping 2010 The effect of chronic caffeine supplementation on endurance performance has been studied extensively in different populations. However, concurrent research on the effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance exercise in hot and humid conditions is unavailable | To determine the effect of caffeine supplementation on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in hot and humid conditions | 9 heat-adapted recreational male runners Age 25.4±6.9 years Weight (kg) 57.6±8.4 Non-users of caffeine (23.7±12.6 mg/day) Randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over design (at least 7 days gap between trials to nullify effect of caffeine) Caffeine (5 mg/kg) or placebo ingested as a capsule one hour before a running trial to exhaustion (70% VO2 max on a motorised treadmill in a heat-controlled laboratory (31 °C, 70% humidity) Diet monitored for 3 days before first trial and repeated for 3 days before 2nd trial (to minimise variation in pre-exercise muscle glycogen) Subjects asked to refrain from heavy exercise for 24 h before trials Subjects drank 3 ml of cool water per kg of body weight every 20 min during running trial to stay hydrated Heart rate (HR), core body temperature and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded at intervals of 10 mins, while oxygen consumption was measured at intervals of 20 min | Mean exhaustion time was 31.6% higher in the caffeine group: • Placebo 83.6±21.4 • Caffeine 110.1±29.3 Running time to exhaustion was significantly higher (p | Ingestion of caffeine improved the endurance running performance, but did not affect heart rate, core body temperature, oxygen uptake or RPE. | The lower RPE during the caffeine trial may be because of the positive effect of caffeine ingestion on nerve impulse transmission, as well as an analgesic effect and psychological effect. Perhaps this is the same reason subjects could sustain the treadmill running for longer in the caffeine trial. |

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

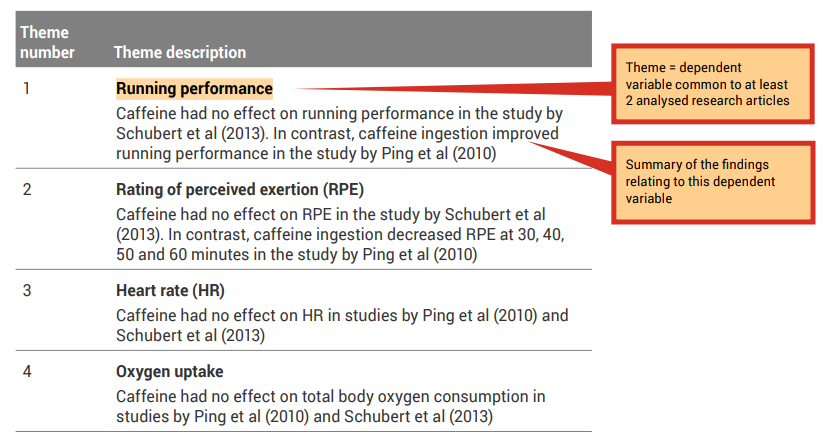

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

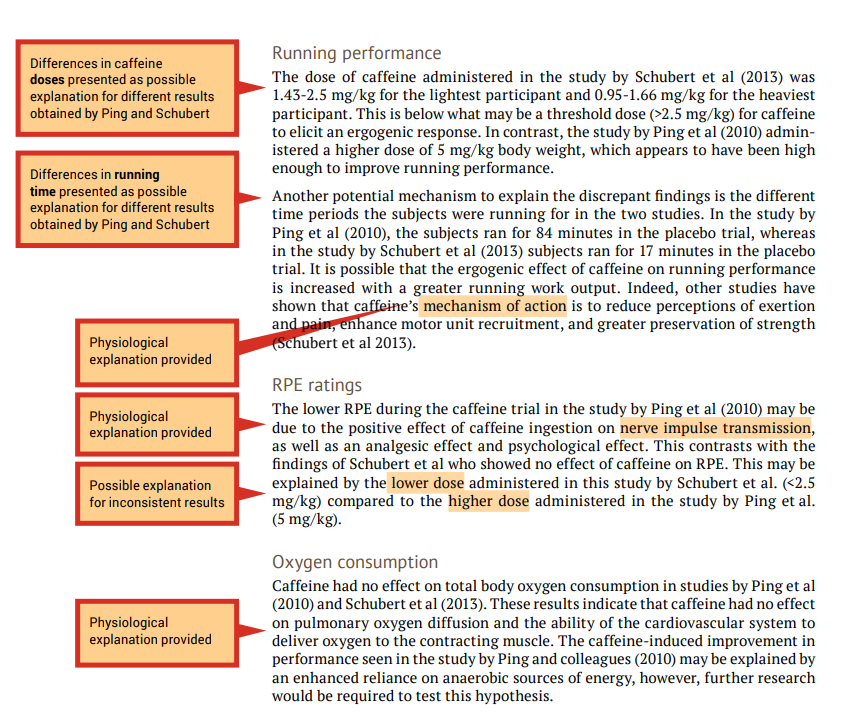

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

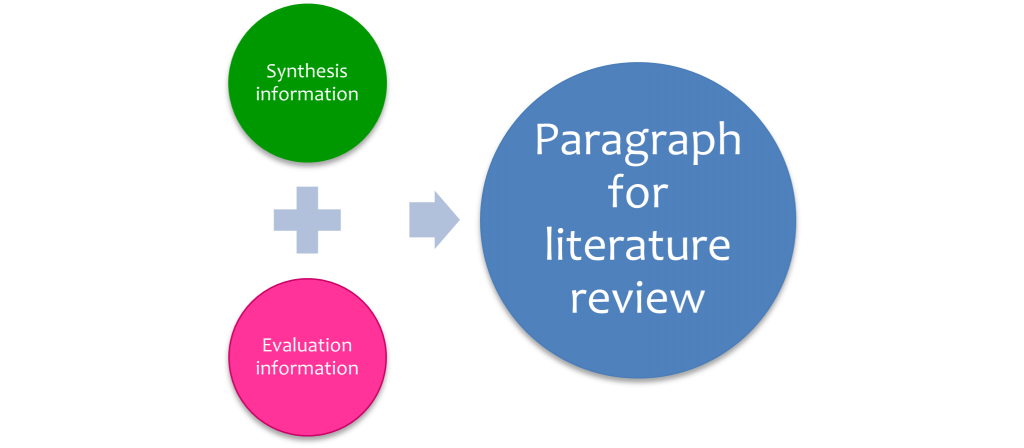

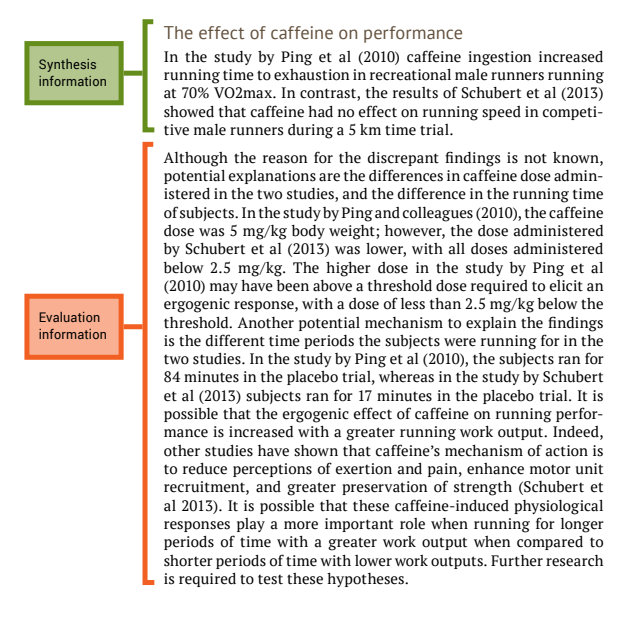

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

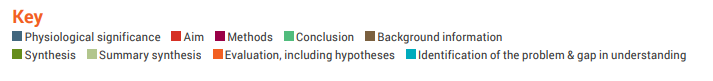

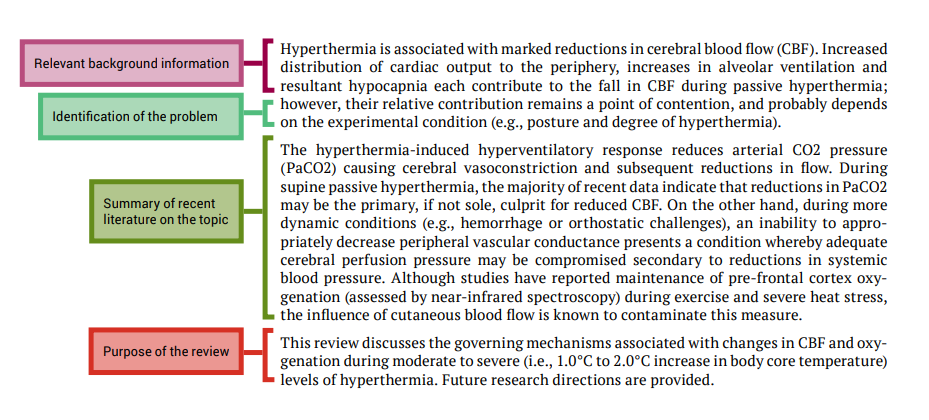

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Scientific Review Article

Affiliation.

- 1 Massachusetts General Hospital, Department of Radiology, Boston, MA, USA.

- PMID: 38416900

- DOI: 10.1093/jbi/wbad028

Scientific review articles are comprehensive, focused reviews of the scientific literature written by subject matter experts. The task of writing a scientific review article can seem overwhelming; however, it can be managed by using an organized approach and devoting sufficient time to the process. The process involves selecting a topic about which the authors are knowledgeable and enthusiastic, conducting a literature search and critical analysis of the literature, and writing the article, which is composed of an abstract, introduction, body, and conclusion, with accompanying tables and figures. This article, which focuses on the narrative or traditional literature review, is intended to serve as a guide with practical steps for new writers. Tips for success are also discussed, including selecting a focused topic, maintaining objectivity and balance while writing, avoiding tedious data presentation in a laundry list format, moving from descriptions of the literature to critical analysis, avoiding simplistic conclusions, and budgeting time for the overall process.

Keywords: manuscript; research; scientific review article; writing.

© Society of Breast Imaging 2023. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected].

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Practical Steps to Writing a Scientific Manuscript. Grimm LJ, Harvey JA. Grimm LJ, et al. J Breast Imaging. 2022 Dec 11;4(6):640-648. doi: 10.1093/jbi/wbac059. J Breast Imaging. 2022. PMID: 38416993

- Rules to be adopted for publishing a scientific paper. Picardi N. Picardi N. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:1-3. Ann Ital Chir. 2016. PMID: 28474609

- Writing a narrative biomedical review: considerations for authors, peer reviewers, and editors. Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Blackmore H, Kitas GD. Gasparyan AY, et al. Rheumatol Int. 2011 Nov;31(11):1409-17. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1999-3. Epub 2011 Jul 29. Rheumatol Int. 2011. PMID: 21800117 Review.

- Tips and tricks for writing a scientific manuscript. Marmotti A, Peretti GM, Mangiavini L, de Girolamo L, Tarella C, Bonasia DE, Mattia S, Tellini A, Bellato E, Agati G, Blonna D, Castoldi F. Marmotti A, et al. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020 Jul-Aug;34(4 Suppl. 3):441-449. Congress of the Italian Orthopaedic Research Society. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2020. PMID: 33261307

- Scientific Publishing in Biomedicine: Information Literacy. Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Kashfi K, Ghasemi A. Bahadoran Z, et al. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Aug 12;20(3):e128701. doi: 10.5812/ijem-128701. eCollection 2022 Jul. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2022. PMID: 36407030 Free PMC article. Review.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.