Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

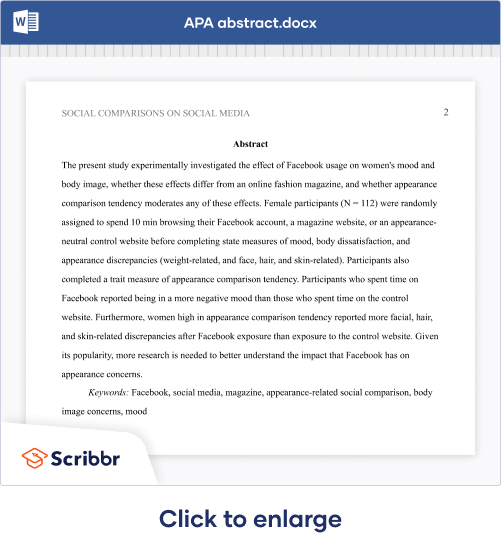

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

Qualitative research methods in medical dissertations: an observational methodological study on prevalence and reporting quality of dissertation abstracts in a German university

Charlotte ullrich.

Department of General Practice and Health Services Research, University of Heidelberg Hospital, INF 130.3, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

Anna Stürmlinger

Michel wensing, associated data.

The data of the repository databank is semi-public and can be accessed from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. A data extraction table is available in App. 2.Competing interests and funding: We have no conflicts of interest to disclose and no funding to report.

Qualitative methods offer a unique contribution to health research. Academic dissertations in the medical field provide an opportunity to explore research practice. Our aim was to assess the use of qualitative methods in dissertations in the medical field.

By means of a methodological observational study, an analysis of all academic medical dissertations’ abstracts between 1998 and 2018 in a repository databank of a large medical university faculty in Germany was performed. This included MD dissertations (Dr. med. (dent.)) and medical science dissertations (Dr. sc. hum.). All abstracts including “qualitativ*” were screened for studies using qualitative research methods. Data were extracted from abstracts using a category grid considering a) general characteristics (year, language, degree type), b) discipline, c) study design (mixed methods/qualitative only, data conduction, data analysis), d) sample (size and participants) and e) technologies used (data analysis software and recording technology). Thereby reporting quality was assessed.

In total, 103 abstracts of medical dissertations between 1998 and 2018 (1.4% of N = 7619) were included, 60 of MD dissertations and 43 of medical sciences dissertations. Half of the abstracts ( n = 51) referred to dissertations submitted since 2014. Most abstracts related to public health/hygiene ( n = 27) and general practice ( n = 26), followed by medical psychology ( n = 19). About half of the studies ( n = 47) used qualitative research methods exclusively, the other half ( n = 56) used mixed methods. For data collection, primarily individual interviews were used ( n = 80), followed by group interviews ( n = 33) and direct observation ( n = 11). Patients ( n = 36), physicians ( n = 36) and healthcare professionals ( n = 17) were the most frequent research participants. Incomplete reporting of participants and data analysis was common ( n = 67). Nearly half of the abstracts ( n = 46) lacked information on how data was analysed, most of the remaining ( n = 43) used some form of content analysis. In summary, 36 abstracts provided all crucial data (participants, sample size,; data collection and analysis method).

A small number of academic dissertations used qualitative research methods. About a third of these reported all key aspects of the methods used in the abstracts. Further research on the quality of choice and reporting of methods for qualitative research in dissertations is recommended.

Qualitative research methods offer a unique contribution to health research, particular for exploration of the experiences of patients, healthcare professionals and others [ 1 – 5 ]. While (general) epidemiology primarily addresses health and healthcare in populations and clinical research concentrates on medical interventions and health prognosis, qualitative research methods focus on different actors’ perspectives, experiences and behaviours in health-related contexts. Qualitative research entails a broad spectrum of methods of data conduction and data analysis: individual interviews illuminate individual perceptions [ 6 ], group interviews deliver insights into shared norms and opinions [ 7 ], direct observations facilitate understandings of behaviours in healthcare practice [ 8 – 10 ] and documents can offer insights into discourses and self-representations [ 11 ]. For data analysis, methods combining inductive and deductive steps are most suitable for exploratory research questions utilizing existing results, theories and concepts [ 12 ]. Given these prospects, little is known on the practice of applying qualitative research methods, especially concerning medicine.

In dissertations, a foundation for future scientific work is laid; therefore, guidance and rigour are of special importance [ 13 ]. Dissertations in medical departments provide a good opportunity to explore research practices of students and young academics. In Germany, about 60% of all graduating medical students complete an academic dissertation [ 14 ], which they usually finish parallel to medical school within a full-time equivalent of about a year [ 15 – 18 ]. As a by-product, medical doctoral students are increasingly among the authors of published research, holding first-authorship in about 25% [ 18 – 20 ].

In Germany, basic scientific training is a required part of the medical curriculum and recent policies put even more emphasis on the development of scientific competencies [ 15 , 21 , 22 ]. National regulations specify scientific competencies giving explicit recommendations for quantitative methods. Medical students have rarely received training in qualitative methods. However, health care professions and qualitative methods share a perspective directed to practice and interactions. Interviews and observations are already commonly used as clinical and diagnostic tools.

In addition to the doctoral degrees for medical and dental graduates (Doctor medicinae (dentariae), Dr. med. (dent.)), students with other disciplinary backgrounds (e.g. natural scientists, psychologists and social scientists) complete dissertations at medical faculties in Germany (often labelled Doctor scientiarum humanarum, Dr. sc. hum. or Doctor rerum medicarum, Dr. rer. medic.). Although regulations differ slightly, the degrees are usually situated within and regulated by the same institutional culture and context (e.g. faculty, department, supervision and aspired publications).

The aim of this study was to understand the current practice of applying qualitative research methods helping identify gaps in reporting and need for guidance. By means of a methodological study – a subtype of observational studies that evaluates the design, analysis of reporting of other research-related reports [ 23 ] – we investigated volume and variety of the use of qualitative research methods in dissertations at a German medical faculty. Hereby we wanted to inform methodological advances to health research and outline implications for medical education in scientific competencies training.

Search strategy

Dissertations in the medical field were retrospectively assessed: In a document analysis, all dissertation abstracts at one medical faculty were reviewed. This faculty was chosen as it is one of the oldest and largest medical faculties in Germany, with a strong research tradition and a high dissertation rate among graduating students. All abstracts from 01/01/1998 to 31/12/2018, which were publicly available in the repository databank of the university, were reviewed. This included MD dissertations (Dr. med. (dent.)) and medical science dissertations (Dr. sc. hum.) written in German or English. All types of studies using qualitative research methods, all types of human participants, all types of interventions and all types of measures were eligible. We focused on abstracts, because full text dissertations are not publicly available and are helpful to get an overview of a number of method-related issues. Although serving as a proxy, abstracts should provide a sufficient summary of the dissertation, including crucial information on study design, independently from the full text. In the databank, relevant documents had to be labelled a) “abstract of a medical dissertation” (referring to both degree types). To further identify dissertations using qualitative methods b) the search term “qualitativ*” was used as an inclusion criterium.

Selection and data extraction

All identified abstracts were pre-screened independently by two researchers (AS, LS) and then reviewed by the main research team (KK, AS, CU) excluding abstracts using “qualitativ*” only in respect to non-methods-related issues (e.g. quality of life). Data on a) general characteristics (year, language, degree type), b) discipline, c) study design (mixed methods/qualitative only, data conduction, data analysis), d) sample (size and participants) and e) technologies used (data analysis software and recording technology) (see App. 2) was then extracted independently by two team members (AS, LS) and crossed-checked (KK, CU). Data extraction was initially guided by two widely used reporting guidelines for qualitative health research articles [ 24 , 25 ] and adapted to reflect the abstract format: Abstracts provided comparable information on the set-up of study design and sample. Reporting of results was not assessed due to heterogeneity and briefness. Data extraction forms were piloted and adjusted to inductive findings. Disagreements were discussed, assessed and solved by consensus by the main research team (KK, AS, CU). Extracted data were analysed and reported as absolute and relative frequencies. As all abstracts were available, no further data was obtained from authors.

Search results

Out of a total of 7619 dissertation abstracts, 296 dissertations were initially identified. Of these, 173 abstracts were excluded from the study as “qualitativ*” in these abstracts did not refer to the research method. Additionally, 20 abstracts (12 medicine, 8 medical science) were not further included in the analysis due to an ambiguous and inconclusive use of the label “qualitative methods” and/or restricted comparability with the otherwise pre-dominant interview-based study designs: a) a qualitative research design was stated, but no further information on the approach was given ( n = 7), b) no explicit distinction was made between qualitative research design and a clinical diagnostic approach ( n = 4), c) the qualitative approach comprised of additional free text answers in written questionnaires only ( n = 6), and d) only document analysis or observation was used ( n = 3). In total, 103 abstracts (1.4% of 7619) were included in the analysis.

Low but increasing use

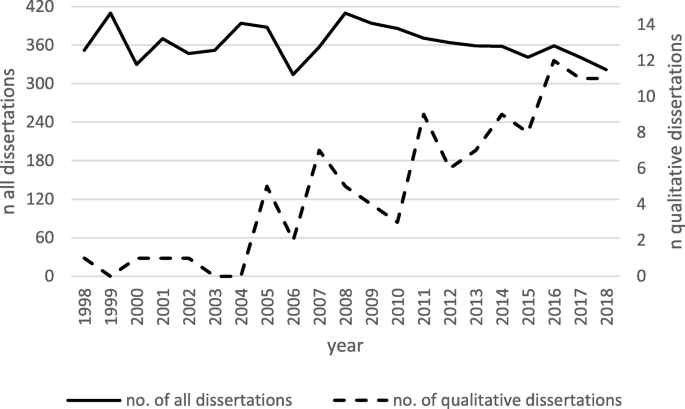

Since 1998, the number of dissertations applying qualitative methods has continually increased while the total number of dissertations remained stable (between n = 314 in 2006 and n = 410 in 1999 and 2008, M (1998–2018) = 362.8, SD = 26.1) (Fig. 1 ). Before 2005 there was yearly not more than one dissertation that used qualitative methods. Since then, the number has steadily raised to more than 10 dissertations per year, equivalent to an increase from 0.28% in 1998 to 3.42% in 2018 of all listed dissertation abstracts per year.

Number of all dissertations and dissertations using qualitative methods per year between 1998 and 2018

General characteristics

Abstracts nearly equally referred to dissertations leading to an MD degree (Dr. med. n = 57, Dr. med. Dent. n = 3) and medical science degree (Dr. sc. hum. n = 43), respectively. The included dissertation abstracts were based in 12 different sub-specialties , most in general practice ( n = 26), in public health and hygiene ( n = 27) and medical psychology ( n = 19); the Dr. med. (dent.) abstracts having a higher share in general practice ( n = 21) and the Dr. sc. hum. abstracts in public health/hygiene ( n = 16) (s. Table 1 ).

Usage of qualitative research design in dissertations at a medical faculty

| Dr. med. (dent.) ( = 60) | Dr. sc. hum. ( = 43) | Total ( = 103) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Health/ Hygiene | 11 (18.3) | 16 (37.2) | 27 (26.2) |

| General Practice | 21 (35.0) | 5 (11.6) | 26 (25.2) |

| Medical Psychology | 7 (11.7) | 12 (27.9) | 19 (18.4) |

| Internal Medicine/ Psychosomatics | 11 (18.3) | 3 (7.0) | 14 (13.6) |

| Health Services Research | 3 (5.0) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (3.9) |

| Psychiatry | 0 (−) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (2.9) |

| Paediatrics | 3 (5.0) | 0 (−) | 3 (2.9) |

| Medical Biometry und Informatics | 0 (−) | 2 (4.7) | 2 (1.9) |

| Others (Anatomy, Gynaecology, History, Neurology, Social Medicine) | 4 (6.7) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (4.9) |

| Mixed Methods Approach | 24 (40.0) | 32 (74.4) | 56 (54.4) |

| Qualitative Approaches only | 36 (60.0) | 11 (25.6) | 47 (45.6) |

| Document analysis | 3 (5.0) | 2 (4.7) | 5 (4.9) |

| Interviews (individual) | 43 (71.7) | 37 (86.0) | 80 (77.7) |

| Group Interviews | 21 (35.0) | 12 (27.9) | 33 (32.0) |

| Observation | 5 (8.3) | 6 (14.0) | 11 (10.7) |

| Questionnaire | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (2.9) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.7) | 4 (9.3) | 5 (4.9) |

| Health Care Professionals | 11 (18.3) | 6 (14.0) | 17 (16.5) |

| Patients | 19 (31.7) | 17 (39.5) | 36 (35.0) |

| Physicians | 27 (45.0) | 9 (20.9) | 36 (35.0) |

| Relatives | 4 (6.7) | 3 (7.0) | 7 (6.8) |

| Students | 10 (17) | 1 (2.3) | 11 (10.7) |

| Other | 6 (10) | 10 (23.3) | 16 (15.5) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.7) | 6 (14.0) | 7 (6.8) |

| 2–10 | 6 (10.0) | 4 (9.3) | 10 (9.7) |

| 11–20 | 5 (8.3) | 7 (16.3) | 12 (11.7) |

| 21–30 | 9 (15.0) | 4 (9.3) | 13 (12.6) |

| 31–40 | 5 (8.3) | 3 (7.0) | 8 (7.8) |

| 41–50 | 0 (−) | 3 (7.0) | 3 (2.9) |

| 51–60 | 4 (6.7) | 2 (4.7) | 6 (5.8) |

| > 60 | 2 (3.3) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (2.9) |

| Not reported | 12 (20.0) | 13 (30.2) | 25 (24.3) |

| Not used or unclear | 17 (28.3) | 6 (14.0) | 23 (22.3) |

| 1–5 | 7 (11.7) | 1 (2.3) | 8 (7.8) |

| 6–10 | 4 (6.7) | 4 (9.3) | 8 (7.8) |

| > 10 | 2 (3.3) | 3 (7.0) | 5 (4.9) |

| Not reported | 8 (13.3) | 4 (9.3) | 12 (11.7) |

| Not used or unclear | 39 (65.0) | 31 (72.1) | 70 (68.0) |

| 2–20 | 4 (19.0) | 1 (8.3) | 5 (15.2) |

| 21–40 | 4 (19.0) | 1 (8.3) | 5 (15.2) |

| 41–60 | 3 (14.3) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (12.1) |

| 61–76 | 2 (9.5) | 0 (−) | 2 (6.1) |

| Not reported | 8 (38.1) | 9 (75.0) | 17 (51.5) |

| Audio | 21 (35.0) | 10 (23.3) | 31 (30.1) |

| Video | 5 (8.3) | 1 (2.3) | 6 (5.8) |

| Not reported | 34 (56.7) | 32 (74.4) | 66 (64.1) |

| Content Analysis (without P. Mayring) | 16 (26.7) | 10 (23.3) | 26 (25.2) |

| Content Analysis following P. Mayring | 14 (23.3) | 2 (4.7) | 16 (15.5) |

| Grounded Theory | 1 (1.7) | 4 (9.3) | 5 (4.9) |

| Other | 6 (1.0) | 4 (9.3) | 10 (9.7) |

| Not reported | 23 (38.3) | 23 (53.5) | 46 (44.7) |

| ATLAS.ti | 12 (20.0) | 2 (4.7) | 14 (13.6) |

| MAXQDA | 3 (5.0) | 0 (−) | 3 (2.9) |

| NVivo | 1 (1.7) | 2 (4.7) | 3 (2.9) |

| Other | 2 | 1 (2.3) | 3 (2.9) |

| Not reported | 42 (70.0) | 38 (88.4) | 80 (77.7) |

Most abstracts followed at least roughly the common structure of background, methods, results and conclusion. The length of the abstracts varied between less than one and more than three pages, with most abstracts being one to two pages long; 77 abstracts were written in German and 26 in English.

Study design

About half of the studies used qualitative research methods exclusively ( n = 47; 60% of Dr. med. (dent.) abstracts, 26% of Dr. sc. hum. abstracts), the other half mixed methods ( n = 56; 40% of Dr. med. (dent.) abstracts, 74% of Dr. sc. hum. abstracts; Table Table1). 1 ). Individual interviews were the most common form of data collection ( n = 80), followed by group interviews ( n = 33) and observation ( n = 11). In total, 23 abstracts indicated the use of a combination of different qualitative methods of data conduction, all of these included individual interviews. For documentation/recording, when reported ( n = 37), audio recording was used in most cases ( n = 3).

Little difference regarding method of data conduction were found between pure qualitative and mixed-methods designs. Mixed methods studies rather included physicians ( n = 21) and used predominantly general content analysis ( n = 14), when reported; whereas qualitative studies rather included patients ( n = 28) and used predominantly both content analysis ( n = 14) and content analysis following Mayring ( n = 12). Overall incomplete reporting was more common in mixed-method studies ( n = 41) than qualitative studies ( n = 26, 55.3%) (see App. 2).

Sample size varied widely: Overall, 67 abstracts provided a sample size. Of those, a median number of 29 people (min-max: 2–136) participated in individual and group interviews. Only in Dr. sc. hum. dissertations using mixed methods, lower median sample sizes were reported for the qualitative part (Md = 22, min-max: 6–110; n = 17) compared to dissertations using qualitative methods only (medical science ( n = 7): Md = 31, min-max: 16–50; MD ( n = 29): Md = 29, min-max: 7–136) and Dr. med. (dent.) dissertations with mixed methods (Md = 30, min-max: 2–62; n = 14). In individual interviews, when sample size was reported ( n = 55, 69% of 80), it distributed roughly equally in the ranges of 1–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–50 and above 50 (Md = 25; min-max: 2–110). For the 33 dissertations using group interviews, the number of groups is given in 20 abstracts, the number of participants in 15 abstracts. Between 1 and 24 group interviews were conducted with a median total of 24 participants (min-max: 2–65) (see Table Table1 1 ).

Patients ( n = 36) and physicians ( n = 36) were the overall most frequent research participants , followed by other health care professionals ( n = 17), students ( n = 11) and relatives of patients ( n = 7). Other participants ( n = 16) included: representatives of self-help organizations and other experts, educators such as teachers and policy makers. In 33% ( n = 31) of the abstracts, more than one participant group was included, 6.8% ( n = 7) did not specify research participants. While MD dissertations predominantly included physicians ( n = 27) and patients ( n = 19), Dr. sc. hum. dissertations included mostly patients ( n = 17) and other participants ( n = 10).

Data analysis

For data analysis, if reported ( n = 57), content analyses were the most common used method ( n = 42), including the highly deductive approach formulated by Mayring [ 26 ] ( n = 16), mostly used in MD dissertations ( n = 14). Among other reported methods ( n = 15), grounded theory ( n = 5) was the most common approach; rarely mentioned methods include framework analysis and non-specific analysis combining inductive and deductive approaches. Forty-six abstracts did not provide information on the analysis method used (38.3% of MD abstracts, 53% of medical science abstracts). If reported ( n = 24), ATLAS.ti ( n = 14), MAXQDA ( n = 3) and NVivo ( n = 3) were mentioned most frequently as qualitative data analysis programs.

In summary, 36 abstracts provided all crucial data (participants: sample size, characteristics, i.e. healthcare professional/patient; data collection and analysis method). Thus, 58% ( n = 35) of MD dissertation abstracts and 74% ( n = 32) of Dr. sc. hum. dissertation abstracts had at least one missing information.

The results show a low but increasing use of qualitative research methods in medical dissertations. Abstracts nearly equally referred to dissertations leading to an MD degree and medical science doctorate respectively; half of which were submitted since 2011. Qualitative methods were used in several departments, most frequently in those for general practice, public health and medical psychology mirroring an already known affinity between the objective of certain medical disciplines and perspective qualitative methods [ 27 , 28 ].

About half of the studies used qualitative research methods exclusively, the other half mixed methods: While some differences were found, due to short format and sparse information within the abstract a strict differentiation between qualitative approaches alone and combined quantitative and qualitative designs was not made. Little difference according to degree type was observed. This points to a strong shared dissertation culture, that balances and conceals differences in academic training between medical students and graduates from other, quite diverse, disciplines (e.g. from humanities, natural and social sciences) pursuing a doctorate at a medical faculty.

Limited variety in methods used

The results show a strong preference for certain methods in data conduction, research participants and data analysis: Individual and group interviews were predominant as well as content analysis, especially Mayring’s deductive approach. All in all, a limited use of the broad spectrum of qualitative research methods can be observed. Interviews are important to gain insights on actors’ perspective [ 6 ]; however, they have limited information value when it comes to actual processes and practice of health care. To investigates those, additional direct observation would be suitable [ 8 , 9 ]. In group interviews shared norms and opions can be observed, they are not suitable to capture individual perspectices. Group interviews go along with higher time and efforts regarding scheduling, interview guidance and data analysis [ 7 ]. Within the dissertations, documents are rarely used as data within the dissertations, but could be useful readily available documents.

Included research participants were mostly patients and physicians. This might be due to the research questions posed or the availability of participants. However, to reflect the complexity of health care a higher diversity of research questions, expanding participants (e.g. other health care professionals and caregivers) and based on a thorough knowledge of available methods, including qualitative approaches, might be needed.

As for methods of analysis, the results show a predominant use of a form of content analysis, with a strong affinity to quantitative analysis often limited to description forgoing in-depth analysis. As qualitative methods belong to the interpretative paradigm, most qualitative methodologies emphasize inductive analyses (e.g. Grounded Theory) and/or a combination of induction and deduction [ 12 , 29 ]. By using primarily descriptive content analysis the full potential of qualitative research and depth of the data to gain new a insights are thus neglected. Since knowledge about and application of qualitative methods are not part of the medical curriculum, doctoral students lack training in using qualitative methods and grasping the possibilities these methods convey for in-depth original knowledge.

Incomplete reporting

One fundamental principle of good research practice is accurate reporting. For empirical research, reporting on research design and methods is crucial to ensure comparability and reflect reach of research results. Within medicine and other health sciences, while debated [ 30 ], reporting guidelines are increasingly used to guarantee a basic standard. While qualitative research designs differ from clinical and quantitative designs regarding theoretical and methodological background, study aims and research process, rigorous reporting is a shared standard: this includes reporting on data conduction, sampling, participants and data analysis (e.g. COREQ [ 24 ]).

In our study, incomplete reporting regarding research design and methods was common. Especially, information on methods of data analysis was missing in about half of the abstracts reflecting the limited awareness of the plethora of qualitative analysis methods. Additionally, a third of the abstracts did not provide information on sample size. Although the importance of a “sufficient” sample size is controversially discussed, identifying the sources and putting their contributions into perspective is a paramount characteristic of qualitative research [ 31 – 33 ]. All in all, incomplete reporting was common ( n = 67). Additionally, out of 123 initially identified abstracts, 20 had to be excluded from the analysis as comparability was not given mainly due to the inconclusive use of the term qualitative methods.

Several issues should be considered when interpreting the findings from this study. As a case study at one large faculty, which has a strong research orientation, the generalizability of the findings is uncertain. It seems unlikely that the quality of reporting is better in other medical faculties in Germany, but the prevalence of using qualitative methods might be higher. Character and role of the abstracts might not be as apparent as in journal papers, as they serve as a summary of the dissertation and are listed within the online repository databank only. The relation of reporting quality of those abstracts and the full text dissertation or even publication is unknown. Presentation of results was not assessed as information in abstracts were brief and heterogenous. Additionally, insights are limited by the structure of the repository databank itself, i.e. sub-disciplines are combined that sometimes cover distinct research fields or did evolve as separate specialties. All in all, however, the results mirror the critique on the lack of scientific training in medical education [ 17 , 22 , 34 , 35 ] and the want of sufficient reporting in medicine and health science, irrespective of study design [ 36 ].

While recent policies put a strong emphasis on strengthening scientific competences in medical education in Germany [ 15 , 21 , 22 ], especially MD dissertations are only in some degree comparable to dissertation thesis of other disciplines and medical dissertations internationally: In Germany, about 60% of all graduating medical students complete an academic dissertation [ 14 ], which they usually finish parallel to medical school within a full-time equivalent of about a year [ 15 – 18 ]. Graduate programs that exclusively dedicate 1 year for pursuing a dissertation are still discussed as innovative [ 35 ]. Additionally, the expertise of supervisors was not assessed. In a recent opinion paper, Malterud et al. [ 37 ] called for supervisors and dissertation committees holding corresponding methodological skills and experience as well as an academic consensus regarding scientific rigour to ensure high quality theses using qualitative methods. Missing standards in supervision and reporting might have led to the observed results in our study.

Qualitative research methods offer a unique scientific benefit to health care, including medicine. Our results show that within dissertation research, the number of dissertations applying qualitative methods has continually increased mirroring an overall trend in health research. To improve reach and results, a broader spectrum of qualitative methods should be considered when selecting research designs, including e.g. (direct) observation, document and analysis strategies, that combine inductive and deductive approaches. Same holds true for including a more diverse body of research participants. More broadly, reporting and academic practice should be improved.

Reporting guidelines can not only help to improve the quality of reporting but also be used as a tool to supervising graduate students steps commonly associated with qualitative research methods. So far, however, reporting guidelines mainly target full and/or published papers. Still, some reporting guidelines for abstracts are already available [ 38 – 41 ], that could be adapted for dissertation research in health science.

In academic practice, skilled supervision alongside transparent and method-appropriate criteria are the precondition for confident and courageous dissertation research that increases understanding and challenges existing knowledge of health care research. Educational programs strengthening research and reporting skills – within and beyond qualitative methods – should be implemented into medical education more profoundly, at the latest in doctoral training.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Laura Svensson for assisting in reviewing the abstracts and data extraction. In addition, we would like to thank the reviewers for their thorough review and constructive comments.

Abbreviations

| COREQ | Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research |

| Dr. med. | Doctor medicinae |

| Dr. med. dent. | Doctor medicinae dentariae |

| Dr. sc. hum. | Doctor scientiarum humanarum |

| MD | Medical Doctor |

Authors’ contributions

CU and KK conceived the idea for this manuscript. CU, KK and AS reviewed, extracted and analyzed the data. KK led the data analysis. CU wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MW provided substantial comments at different stages of the manuscript. CU, KK and MW critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable. In accordance with the scope and design of this study no formal study protocol was written.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Charlotte Ullrich, Email: [email protected] .

Anna Stürmlinger, Email: [email protected] .

Michel Wensing, Email: [email protected] .

Katja Krug, Email: [email protected] .

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Abstract Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide With Tips & Examples

Table of Contents

Introduction

Abstracts of research papers have always played an essential role in describing your research concisely and clearly to researchers and editors of journals, enticing them to continue reading. However, with the widespread availability of scientific databases, the need to write a convincing abstract is more crucial now than during the time of paper-bound manuscripts.

Abstracts serve to "sell" your research and can be compared with your "executive outline" of a resume or, rather, a formal summary of the critical aspects of your work. Also, it can be the "gist" of your study. Since most educational research is done online, it's a sign that you have a shorter time for impressing your readers, and have more competition from other abstracts that are available to be read.

The APCI (Academic Publishing and Conferences International) articulates 12 issues or points considered during the final approval process for conferences & journals and emphasises the importance of writing an abstract that checks all these boxes (12 points). Since it's the only opportunity you have to captivate your readers, you must invest time and effort in creating an abstract that accurately reflects the critical points of your research.

With that in mind, let’s head over to understand and discover the core concept and guidelines to create a substantial abstract. Also, learn how to organise the ideas or plots into an effective abstract that will be awe-inspiring to the readers you want to reach.

What is Abstract? Definition and Overview

The word "Abstract' is derived from Latin abstractus meaning "drawn off." This etymological meaning also applies to art movements as well as music, like abstract expressionism. In this context, it refers to the revealing of the artist's intention.

Based on this, you can determine the meaning of an abstract: A condensed research summary. It must be self-contained and independent of the body of the research. However, it should outline the subject, the strategies used to study the problem, and the methods implemented to attain the outcomes. The specific elements of the study differ based on the area of study; however, together, it must be a succinct summary of the entire research paper.

Abstracts are typically written at the end of the paper, even though it serves as a prologue. In general, the abstract must be in a position to:

- Describe the paper.

- Identify the problem or the issue at hand.

- Explain to the reader the research process, the results you came up with, and what conclusion you've reached using these results.

- Include keywords to guide your strategy and the content.

Furthermore, the abstract you submit should not reflect upon any of the following elements:

- Examine, analyse or defend the paper or your opinion.

- What you want to study, achieve or discover.

- Be redundant or irrelevant.

After reading an abstract, your audience should understand the reason - what the research was about in the first place, what the study has revealed and how it can be utilised or can be used to benefit others. You can understand the importance of abstract by knowing the fact that the abstract is the most frequently read portion of any research paper. In simpler terms, it should contain all the main points of the research paper.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

Abstracts are typically an essential requirement for research papers; however, it's not an obligation to preserve traditional reasons without any purpose. Abstracts allow readers to scan the text to determine whether it is relevant to their research or studies. The abstract allows other researchers to decide if your research paper can provide them with some additional information. A good abstract paves the interest of the audience to pore through your entire paper to find the content or context they're searching for.

Abstract writing is essential for indexing, as well. The Digital Repository of academic papers makes use of abstracts to index the entire content of academic research papers. Like meta descriptions in the regular Google outcomes, abstracts must include keywords that help researchers locate what they seek.

Types of Abstract

Informative and Descriptive are two kinds of abstracts often used in scientific writing.

A descriptive abstract gives readers an outline of the author's main points in their study. The reader can determine if they want to stick to the research work, based on their interest in the topic. An abstract that is descriptive is similar to the contents table of books, however, the format of an abstract depicts complete sentences encapsulated in one paragraph. It is unfortunate that the abstract can't be used as a substitute for reading a piece of writing because it's just an overview, which omits readers from getting an entire view. Also, it cannot be a way to fill in the gaps the reader may have after reading this kind of abstract since it does not contain crucial information needed to evaluate the article.

To conclude, a descriptive abstract is:

- A simple summary of the task, just summarises the work, but some researchers think it is much more of an outline

- Typically, the length is approximately 100 words. It is too short when compared to an informative abstract.

- A brief explanation but doesn't provide the reader with the complete information they need;

- An overview that omits conclusions and results

An informative abstract is a comprehensive outline of the research. There are times when people rely on the abstract as an information source. And the reason is why it is crucial to provide entire data of particular research. A well-written, informative abstract could be a good substitute for the remainder of the paper on its own.

A well-written abstract typically follows a particular style. The author begins by providing the identifying information, backed by citations and other identifiers of the papers. Then, the major elements are summarised to make the reader aware of the study. It is followed by the methodology and all-important findings from the study. The conclusion then presents study results and ends the abstract with a comprehensive summary.

In a nutshell, an informative abstract:

- Has a length that can vary, based on the subject, but is not longer than 300 words.

- Contains all the content-like methods and intentions

- Offers evidence and possible recommendations.

Informative Abstracts are more frequent than descriptive abstracts because of their extensive content and linkage to the topic specifically. You should select different types of abstracts to papers based on their length: informative abstracts for extended and more complex abstracts and descriptive ones for simpler and shorter research papers.

What are the Characteristics of a Good Abstract?

- A good abstract clearly defines the goals and purposes of the study.

- It should clearly describe the research methodology with a primary focus on data gathering, processing, and subsequent analysis.

- A good abstract should provide specific research findings.

- It presents the principal conclusions of the systematic study.

- It should be concise, clear, and relevant to the field of study.

- A well-designed abstract should be unifying and coherent.

- It is easy to grasp and free of technical jargon.

- It is written impartially and objectively.

What are the various sections of an ideal Abstract?

By now, you must have gained some concrete idea of the essential elements that your abstract needs to convey . Accordingly, the information is broken down into six key sections of the abstract, which include:

An Introduction or Background

Research methodology, objectives and goals, limitations.

Let's go over them in detail.

The introduction, also known as background, is the most concise part of your abstract. Ideally, it comprises a couple of sentences. Some researchers only write one sentence to introduce their abstract. The idea behind this is to guide readers through the key factors that led to your study.

It's understandable that this information might seem difficult to explain in a couple of sentences. For example, think about the following two questions like the background of your study:

- What is currently available about the subject with respect to the paper being discussed?

- What isn't understood about this issue? (This is the subject of your research)

While writing the abstract’s introduction, make sure that it is not lengthy. Because if it crosses the word limit, it may eat up the words meant to be used for providing other key information.

Research methodology is where you describe the theories and techniques you used in your research. It is recommended that you describe what you have done and the method you used to get your thorough investigation results. Certainly, it is the second-longest paragraph in the abstract.

In the research methodology section, it is essential to mention the kind of research you conducted; for instance, qualitative research or quantitative research (this will guide your research methodology too) . If you've conducted quantitative research, your abstract should contain information like the sample size, data collection method, sampling techniques, and duration of the study. Likewise, your abstract should reflect observational data, opinions, questionnaires (especially the non-numerical data) if you work on qualitative research.

The research objectives and goals speak about what you intend to accomplish with your research. The majority of research projects focus on the long-term effects of a project, and the goals focus on the immediate, short-term outcomes of the research. It is possible to summarise both in just multiple sentences.

In stating your objectives and goals, you give readers a picture of the scope of the study, its depth and the direction your research ultimately follows. Your readers can evaluate the results of your research against the goals and stated objectives to determine if you have achieved the goal of your research.

In the end, your readers are more attracted by the results you've obtained through your study. Therefore, you must take the time to explain each relevant result and explain how they impact your research. The results section exists as the longest in your abstract, and nothing should diminish its reach or quality.

One of the most important things you should adhere to is to spell out details and figures on the results of your research.

Instead of making a vague assertion such as, "We noticed that response rates varied greatly between respondents with high incomes and those with low incomes", Try these: "The response rate was higher for high-income respondents than those with lower incomes (59 30 percent vs. 30 percent in both cases; P<0.01)."

You're likely to encounter certain obstacles during your research. It could have been during data collection or even during conducting the sample . Whatever the issue, it's essential to inform your readers about them and their effects on the research.

Research limitations offer an opportunity to suggest further and deep research. If, for instance, you were forced to change for convenient sampling and snowball samples because of difficulties in reaching well-suited research participants, then you should mention this reason when you write your research abstract. In addition, a lack of prior studies on the subject could hinder your research.

Your conclusion should include the same number of sentences to wrap the abstract as the introduction. The majority of researchers offer an idea of the consequences of their research in this case.

Your conclusion should include three essential components:

- A significant take-home message.

- Corresponding important findings.

- The Interpretation.

Even though the conclusion of your abstract needs to be brief, it can have an enormous influence on the way that readers view your research. Therefore, make use of this section to reinforce the central message from your research. Be sure that your statements reflect the actual results and the methods you used to conduct your research.

Good Abstract Examples

Abstract example #1.

Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies.

The abstract:

"Almost all research into the effects of brand placements on children has focused on the brand's attitudes or behavior intentions. Based on the significant differences between attitudes and behavioral intentions on one hand and actual behavior on the other hand, this study examines the impact of placements by brands on children's eating habits. Children aged 6-14 years old were shown an excerpt from the popular film Alvin and the Chipmunks and were shown places for the item Cheese Balls. Three different versions were developed with no placements, one with moderately frequent placements and the third with the highest frequency of placement. The results revealed that exposure to high-frequency places had a profound effect on snack consumption, however, there was no impact on consumer attitudes towards brands or products. The effects were not dependent on the age of the children. These findings are of major importance to researchers studying consumer behavior as well as nutrition experts as well as policy regulators."

Abstract Example #2

Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. The abstract:

"The research conducted in this study investigated the effects of Facebook use on women's moods and body image if the effects are different from an internet-based fashion journal and if the appearance comparison tendencies moderate one or more of these effects. Participants who were female ( N = 112) were randomly allocated to spend 10 minutes exploring their Facebook account or a magazine's website or an appearance neutral control website prior to completing state assessments of body dissatisfaction, mood, and differences in appearance (weight-related and facial hair, face, and skin). Participants also completed a test of the tendency to compare appearances. The participants who used Facebook were reported to be more depressed than those who stayed on the control site. In addition, women who have the tendency to compare appearances reported more facial, hair and skin-related issues following Facebook exposure than when they were exposed to the control site. Due to its popularity it is imperative to conduct more research to understand the effect that Facebook affects the way people view themselves."

Abstract Example #3

The Relationship Between Cell Phone Use and Academic Performance in a Sample of U.S. College Students

"The cellphone is always present on campuses of colleges and is often utilised in situations in which learning takes place. The study examined the connection between the use of cell phones and the actual grades point average (GPA) after adjusting for predictors that are known to be a factor. In the end 536 students in the undergraduate program from 82 self-reported majors of an enormous, public institution were studied. Hierarchical analysis ( R 2 = .449) showed that use of mobile phones is significantly ( p < .001) and negative (b equal to -.164) connected to the actual college GPA, after taking into account factors such as demographics, self-efficacy in self-regulated learning, self-efficacy to improve academic performance, and the actual high school GPA that were all important predictors ( p < .05). Therefore, after adjusting for other known predictors increasing cell phone usage was associated with lower academic performance. While more research is required to determine the mechanisms behind these results, they suggest the need to educate teachers and students to the possible academic risks that are associated with high-frequency mobile phone usage."

Quick tips on writing a good abstract

There exists a common dilemma among early age researchers whether to write the abstract at first or last? However, it's recommended to compose your abstract when you've completed the research since you'll have all the information to give to your readers. You can, however, write a draft at the beginning of your research and add in any gaps later.

If you find abstract writing a herculean task, here are the few tips to help you with it:

1. Always develop a framework to support your abstract

Before writing, ensure you create a clear outline for your abstract. Divide it into sections and draw the primary and supporting elements in each one. You can include keywords and a few sentences that convey the essence of your message.

2. Review Other Abstracts

Abstracts are among the most frequently used research documents, and thousands of them were written in the past. Therefore, prior to writing yours, take a look at some examples from other abstracts. There are plenty of examples of abstracts for dissertations in the dissertation and thesis databases.

3. Avoid Jargon To the Maximum

When you write your abstract, focus on simplicity over formality. You should write in simple language, and avoid excessive filler words or ambiguous sentences. Keep in mind that your abstract must be readable to those who aren't acquainted with your subject.

4. Focus on Your Research

It's a given fact that the abstract you write should be about your research and the findings you've made. It is not the right time to mention secondary and primary data sources unless it's absolutely required.

Conclusion: How to Structure an Interesting Abstract?

Abstracts are a short outline of your essay. However, it's among the most important, if not the most important. The process of writing an abstract is not straightforward. A few early-age researchers tend to begin by writing it, thinking they are doing it to "tease" the next step (the document itself). However, it is better to treat it as a spoiler.

The simple, concise style of the abstract lends itself to a well-written and well-investigated study. If your research paper doesn't provide definitive results, or the goal of your research is questioned, so will the abstract. Thus, only write your abstract after witnessing your findings and put your findings in the context of a larger scenario.

The process of writing an abstract can be daunting, but with these guidelines, you will succeed. The most efficient method of writing an excellent abstract is to centre the primary points of your abstract, including the research question and goals methods, as well as key results.

Interested in learning more about dedicated research solutions? Go to the SciSpace product page to find out how our suite of products can help you simplify your research workflows so you can focus on advancing science.

The best-in-class solution is equipped with features such as literature search and discovery, profile management, research writing and formatting, and so much more.

But before you go,

You might also like.

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Dissertation Structure & Layout 101: How to structure your dissertation, thesis or research project.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) Reviewed By: David Phair (PhD) | July 2019

So, you’ve got a decent understanding of what a dissertation is , you’ve chosen your topic and hopefully you’ve received approval for your research proposal . Awesome! Now its time to start the actual dissertation or thesis writing journey.

To craft a high-quality document, the very first thing you need to understand is dissertation structure . In this post, we’ll walk you through the generic dissertation structure and layout, step by step. We’ll start with the big picture, and then zoom into each chapter to briefly discuss the core contents. If you’re just starting out on your research journey, you should start with this post, which covers the big-picture process of how to write a dissertation or thesis .

*The Caveat *

In this post, we’ll be discussing a traditional dissertation/thesis structure and layout, which is generally used for social science research across universities, whether in the US, UK, Europe or Australia. However, some universities may have small variations on this structure (extra chapters, merged chapters, slightly different ordering, etc).

So, always check with your university if they have a prescribed structure or layout that they expect you to work with. If not, it’s safe to assume the structure we’ll discuss here is suitable. And even if they do have a prescribed structure, you’ll still get value from this post as we’ll explain the core contents of each section.

Overview: S tructuring a dissertation or thesis

- Acknowledgements page

- Abstract (or executive summary)

- Table of contents , list of figures and tables

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Literature review

- Chapter 3: Methodology

- Chapter 4: Results

- Chapter 5: Discussion

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Reference list

As I mentioned, some universities will have slight variations on this structure. For example, they want an additional “personal reflection chapter”, or they might prefer the results and discussion chapter to be merged into one. Regardless, the overarching flow will always be the same, as this flow reflects the research process , which we discussed here – i.e.:

- The introduction chapter presents the core research question and aims .

- The literature review chapter assesses what the current research says about this question.

- The methodology, results and discussion chapters go about undertaking new research about this question.

- The conclusion chapter (attempts to) answer the core research question .

In other words, the dissertation structure and layout reflect the research process of asking a well-defined question(s), investigating, and then answering the question – see below.

To restate that – the structure and layout of a dissertation reflect the flow of the overall research process . This is essential to understand, as each chapter will make a lot more sense if you “get” this concept. If you’re not familiar with the research process, read this post before going further.

Right. Now that we’ve covered the big picture, let’s dive a little deeper into the details of each section and chapter. Oh and by the way, you can also grab our free dissertation/thesis template here to help speed things up.

The title page of your dissertation is the very first impression the marker will get of your work, so it pays to invest some time thinking about your title. But what makes for a good title? A strong title needs to be 3 things:

- Succinct (not overly lengthy or verbose)

- Specific (not vague or ambiguous)

- Representative of the research you’re undertaking (clearly linked to your research questions)

Typically, a good title includes mention of the following:

- The broader area of the research (i.e. the overarching topic)

- The specific focus of your research (i.e. your specific context)

- Indication of research design (e.g. quantitative , qualitative , or mixed methods ).

For example:

A quantitative investigation [research design] into the antecedents of organisational trust [broader area] in the UK retail forex trading market [specific context/area of focus].

Again, some universities may have specific requirements regarding the format and structure of the title, so it’s worth double-checking expectations with your institution (if there’s no mention in the brief or study material).

Acknowledgements

This page provides you with an opportunity to say thank you to those who helped you along your research journey. Generally, it’s optional (and won’t count towards your marks), but it is academic best practice to include this.

So, who do you say thanks to? Well, there’s no prescribed requirements, but it’s common to mention the following people:

- Your dissertation supervisor or committee.

- Any professors, lecturers or academics that helped you understand the topic or methodologies.

- Any tutors, mentors or advisors.

- Your family and friends, especially spouse (for adult learners studying part-time).

There’s no need for lengthy rambling. Just state who you’re thankful to and for what (e.g. thank you to my supervisor, John Doe, for his endless patience and attentiveness) – be sincere. In terms of length, you should keep this to a page or less.

Abstract or executive summary

The dissertation abstract (or executive summary for some degrees) serves to provide the first-time reader (and marker or moderator) with a big-picture view of your research project. It should give them an understanding of the key insights and findings from the research, without them needing to read the rest of the report – in other words, it should be able to stand alone .

For it to stand alone, your abstract should cover the following key points (at a minimum):

- Your research questions and aims – what key question(s) did your research aim to answer?

- Your methodology – how did you go about investigating the topic and finding answers to your research question(s)?

- Your findings – following your own research, what did do you discover?

- Your conclusions – based on your findings, what conclusions did you draw? What answers did you find to your research question(s)?

So, in much the same way the dissertation structure mimics the research process, your abstract or executive summary should reflect the research process, from the initial stage of asking the original question to the final stage of answering that question.

In practical terms, it’s a good idea to write this section up last , once all your core chapters are complete. Otherwise, you’ll end up writing and rewriting this section multiple times (just wasting time). For a step by step guide on how to write a strong executive summary, check out this post .

Need a helping hand?

Table of contents

This section is straightforward. You’ll typically present your table of contents (TOC) first, followed by the two lists – figures and tables. I recommend that you use Microsoft Word’s automatic table of contents generator to generate your TOC. If you’re not familiar with this functionality, the video below explains it simply:

If you find that your table of contents is overly lengthy, consider removing one level of depth. Oftentimes, this can be done without detracting from the usefulness of the TOC.

Right, now that the “admin” sections are out of the way, its time to move on to your core chapters. These chapters are the heart of your dissertation and are where you’ll earn the marks. The first chapter is the introduction chapter – as you would expect, this is the time to introduce your research…

It’s important to understand that even though you’ve provided an overview of your research in your abstract, your introduction needs to be written as if the reader has not read that (remember, the abstract is essentially a standalone document). So, your introduction chapter needs to start from the very beginning, and should address the following questions:

- What will you be investigating (in plain-language, big picture-level)?

- Why is that worth investigating? How is it important to academia or business? How is it sufficiently original?

- What are your research aims and research question(s)? Note that the research questions can sometimes be presented at the end of the literature review (next chapter).

- What is the scope of your study? In other words, what will and won’t you cover ?

- How will you approach your research? In other words, what methodology will you adopt?

- How will you structure your dissertation? What are the core chapters and what will you do in each of them?

These are just the bare basic requirements for your intro chapter. Some universities will want additional bells and whistles in the intro chapter, so be sure to carefully read your brief or consult your research supervisor.

If done right, your introduction chapter will set a clear direction for the rest of your dissertation. Specifically, it will make it clear to the reader (and marker) exactly what you’ll be investigating, why that’s important, and how you’ll be going about the investigation. Conversely, if your introduction chapter leaves a first-time reader wondering what exactly you’ll be researching, you’ve still got some work to do.

Now that you’ve set a clear direction with your introduction chapter, the next step is the literature review . In this section, you will analyse the existing research (typically academic journal articles and high-quality industry publications), with a view to understanding the following questions:

- What does the literature currently say about the topic you’re investigating?

- Is the literature lacking or well established? Is it divided or in disagreement?

- How does your research fit into the bigger picture?

- How does your research contribute something original?

- How does the methodology of previous studies help you develop your own?

Depending on the nature of your study, you may also present a conceptual framework towards the end of your literature review, which you will then test in your actual research.

Again, some universities will want you to focus on some of these areas more than others, some will have additional or fewer requirements, and so on. Therefore, as always, its important to review your brief and/or discuss with your supervisor, so that you know exactly what’s expected of your literature review chapter.

Now that you’ve investigated the current state of knowledge in your literature review chapter and are familiar with the existing key theories, models and frameworks, its time to design your own research. Enter the methodology chapter – the most “science-ey” of the chapters…

In this chapter, you need to address two critical questions:

- Exactly HOW will you carry out your research (i.e. what is your intended research design)?

- Exactly WHY have you chosen to do things this way (i.e. how do you justify your design)?

Remember, the dissertation part of your degree is first and foremost about developing and demonstrating research skills . Therefore, the markers want to see that you know which methods to use, can clearly articulate why you’ve chosen then, and know how to deploy them effectively.

Importantly, this chapter requires detail – don’t hold back on the specifics. State exactly what you’ll be doing, with who, when, for how long, etc. Moreover, for every design choice you make, make sure you justify it.

In practice, you will likely end up coming back to this chapter once you’ve undertaken all your data collection and analysis, and revise it based on changes you made during the analysis phase. This is perfectly fine. Its natural for you to add an additional analysis technique, scrap an old one, etc based on where your data lead you. Of course, I’m talking about small changes here – not a fundamental switch from qualitative to quantitative, which will likely send your supervisor in a spin!

You’ve now collected your data and undertaken your analysis, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods. In this chapter, you’ll present the raw results of your analysis . For example, in the case of a quant study, you’ll present the demographic data, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics , etc.

Typically, Chapter 4 is simply a presentation and description of the data, not a discussion of the meaning of the data. In other words, it’s descriptive, rather than analytical – the meaning is discussed in Chapter 5. However, some universities will want you to combine chapters 4 and 5, so that you both present and interpret the meaning of the data at the same time. Check with your institution what their preference is.

Now that you’ve presented the data analysis results, its time to interpret and analyse them. In other words, its time to discuss what they mean, especially in relation to your research question(s).

What you discuss here will depend largely on your chosen methodology. For example, if you’ve gone the quantitative route, you might discuss the relationships between variables . If you’ve gone the qualitative route, you might discuss key themes and the meanings thereof. It all depends on what your research design choices were.

Most importantly, you need to discuss your results in relation to your research questions and aims, as well as the existing literature. What do the results tell you about your research questions? Are they aligned with the existing research or at odds? If so, why might this be? Dig deep into your findings and explain what the findings suggest, in plain English.

The final chapter – you’ve made it! Now that you’ve discussed your interpretation of the results, its time to bring it back to the beginning with the conclusion chapter . In other words, its time to (attempt to) answer your original research question s (from way back in chapter 1). Clearly state what your conclusions are in terms of your research questions. This might feel a bit repetitive, as you would have touched on this in the previous chapter, but its important to bring the discussion full circle and explicitly state your answer(s) to the research question(s).

Next, you’ll typically discuss the implications of your findings . In other words, you’ve answered your research questions – but what does this mean for the real world (or even for academia)? What should now be done differently, given the new insight you’ve generated?

Lastly, you should discuss the limitations of your research, as well as what this means for future research in the area. No study is perfect, especially not a Masters-level. Discuss the shortcomings of your research. Perhaps your methodology was limited, perhaps your sample size was small or not representative, etc, etc. Don’t be afraid to critique your work – the markers want to see that you can identify the limitations of your work. This is a strength, not a weakness. Be brutal!

This marks the end of your core chapters – woohoo! From here on out, it’s pretty smooth sailing.

The reference list is straightforward. It should contain a list of all resources cited in your dissertation, in the required format, e.g. APA , Harvard, etc.