Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.2 The Elements of Culture

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish material culture and nonmaterial culture.

- List and define the several elements of culture.

- Describe certain values that distinguish the United States from other nations.

Culture was defined earlier as the symbols, language, beliefs, values, and artifacts that are part of any society. As this definition suggests, there are two basic components of culture: ideas and symbols on the one hand and artifacts (material objects) on the other. The first type, called nonmaterial culture , includes the values, beliefs, symbols, and language that define a society. The second type, called material culture , includes all the society’s physical objects, such as its tools and technology, clothing, eating utensils, and means of transportation. These elements of culture are discussed next.

Every culture is filled with symbols , or things that stand for something else and that often evoke various reactions and emotions. Some symbols are actually types of nonverbal communication, while other symbols are in fact material objects. As the symbolic interactionist perspective discussed in Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” emphasizes, shared symbols make social interaction possible.

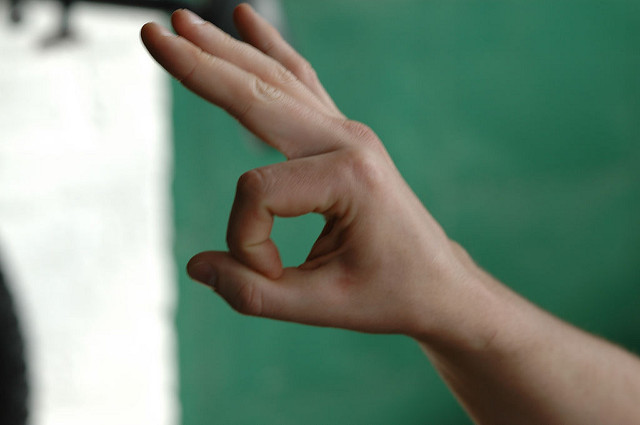

Let’s look at nonverbal symbols first. A common one is shaking hands, which is done in some societies but not in others. It commonly conveys friendship and is used as a sign of both greeting and departure. Probably all societies have nonverbal symbols we call gestures , movements of the hands, arms, or other parts of the body that are meant to convey certain ideas or emotions. However, the same gesture can mean one thing in one society and something quite different in another society (Axtell, 1998). In the United States, for example, if we nod our head up and down, we mean yes, and if we shake it back and forth, we mean no. In Bulgaria, however, nodding means no, while shaking our head back and forth means yes! In the United States, if we make an “O” by putting our thumb and forefinger together, we mean “OK,” but the same gesture in certain parts of Europe signifies an obscenity. “Thumbs up” in the United States means “great” or “wonderful,” but in Australia it means the same thing as extending the middle finger in the United States. Certain parts of the Middle East and Asia would be offended if they saw you using your left hand to eat, because they use their left hand for bathroom hygiene.

The meaning of a gesture may differ from one society to another. This familiar gesture means “OK” in the United States, but in certain parts of Europe it signifies an obscenity. An American using this gesture might very well be greeted with an angry look.

d Wang – ok – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Some of our most important symbols are objects. Here the U.S. flag is a prime example. For most Americans, the flag is not just a piece of cloth with red and white stripes and white stars against a field of blue. Instead, it is a symbol of freedom, democracy, and other American values and, accordingly, inspires pride and patriotism. During the Vietnam War, however, the flag became to many Americans a symbol of war and imperialism. Some burned the flag in protest, prompting angry attacks by bystanders and negative coverage by the news media.

Other objects have symbolic value for religious reasons. Three of the most familiar religious symbols in many nations are the cross, the Star of David, and the crescent moon, which are widely understood to represent Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, respectively. Whereas many cultures attach no religious significance to these shapes, for many people across the world they evoke very strong feelings of religious faith. Recognizing this, hate groups have often desecrated these symbols.

As these examples indicate, shared symbols, both nonverbal communication and tangible objects, are an important part of any culture but also can lead to misunderstandings and even hostility. These problems underscore the significance of symbols for social interaction and meaning.

Perhaps our most important set of symbols is language. In English, the word chair means something we sit on. In Spanish, the word silla means the same thing. As long as we agree how to interpret these words, a shared language and thus society are possible. By the same token, differences in languages can make it quite difficult to communicate. For example, imagine you are in a foreign country where you do not know the language and the country’s citizens do not know yours. Worse yet, you forgot to bring your dictionary that translates their language into yours, and vice versa, and your iPhone battery has died. You become lost. How will you get help? What will you do? Is there any way to communicate your plight?

As this scenario suggests, language is crucial to communication and thus to any society’s culture. Children learn language from their culture just as they learn about shaking hands, about gestures, and about the significance of the flag and other symbols. Humans have a capacity for language that no other animal species possesses. Our capacity for language in turn helps make our complex culture possible.

Language is a key symbol of any culture. Humans have a capacity for language that no other animal species has, and children learn the language of their society just as they learn other aspects of their culture.

Bill Benzon – IMGP3639 – talk – CC BY-SA 2.0.

In the United States, some people consider a common language so important that they advocate making English the official language of certain cities or states or even the whole country and banning bilingual education in the public schools (Ray, 2007). Critics acknowledge the importance of English but allege that this movement smacks of anti-immigrant prejudice and would help destroy ethnic subcultures. In 2009, voters in Nashville, Tennessee, rejected a proposal that would have made English the city’s official language and required all city workers to speak in English rather than their native language (R. Brown, 2009).

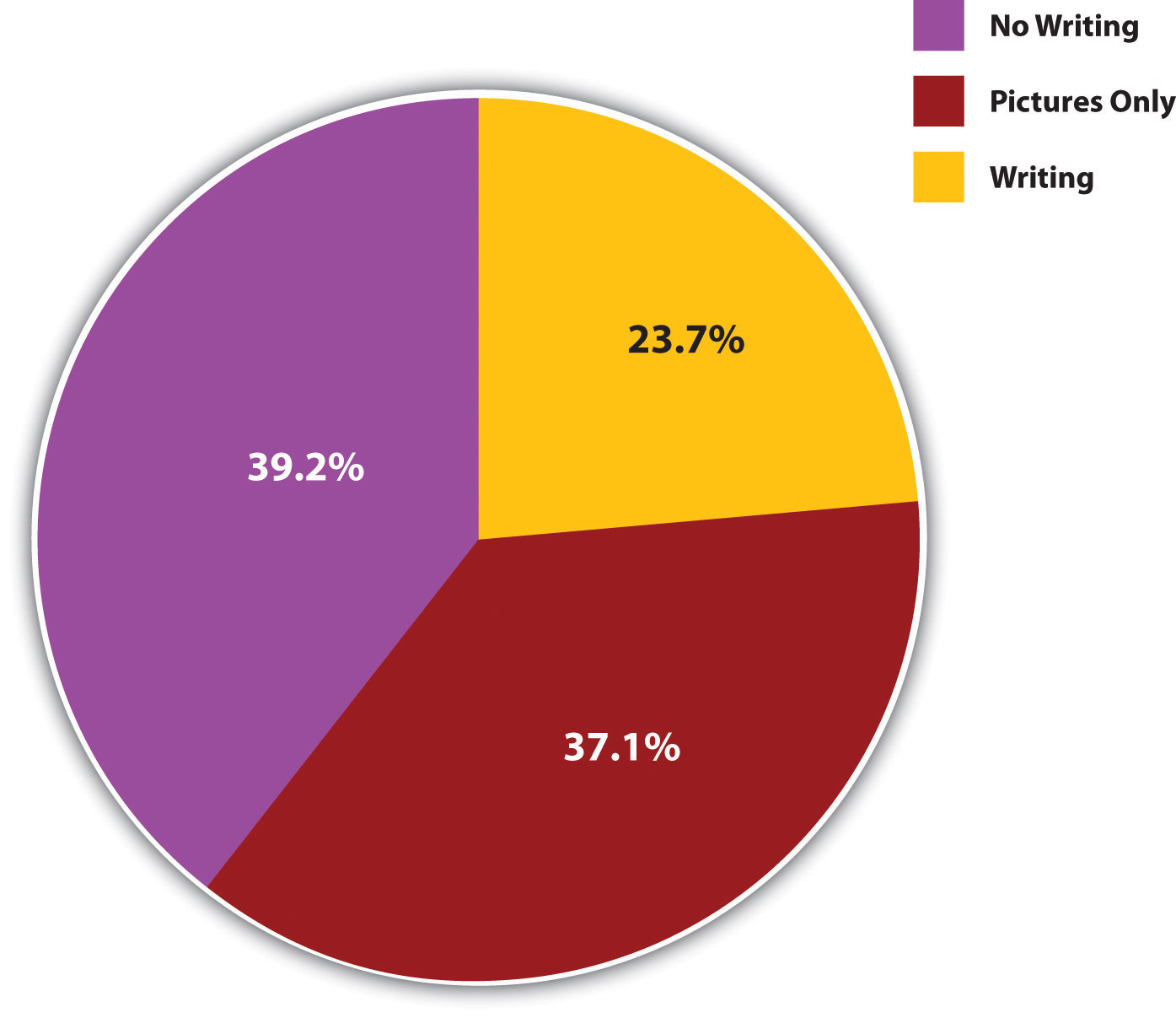

Language, of course, can be spoken or written. One of the most important developments in the evolution of society was the creation of written language. Some of the preindustrial societies that anthropologists have studied have written language, while others do not, and in the remaining societies the “written” language consists mainly of pictures, not words. Figure 3.1 “The Presence of Written Language (Percentage of Societies)” illustrates this variation with data from 186 preindustrial societies called the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample (SCCS), a famous data set compiled several decades ago by anthropologist George Murdock and colleagues from information that had been gathered on hundreds of preindustrial societies around the world (Murdock & White, 1969). In Figure 3.1 “The Presence of Written Language (Percentage of Societies)” , we see that only about one-fourth of the SCCS societies have a written language, while about equal proportions have no language at all or only pictures.

Figure 3.1 The Presence of Written Language (Percentage of Societies)

Source: Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

To what extent does language influence how we think and how we perceive the social and physical worlds? The famous but controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis , named after two linguistic anthropologists, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, argues that people cannot easily understand concepts and objects unless their language contains words for these items (Whorf, 1956). Language thus influences how we understand the world around us. For example, people in a country such as the United States that has many terms for different types of kisses (e.g. buss, peck, smack, smooch, and soul) are better able to appreciate these different types than people in a country such as Japan, which, as we saw earlier, only fairly recently developed the word kissu for kiss.

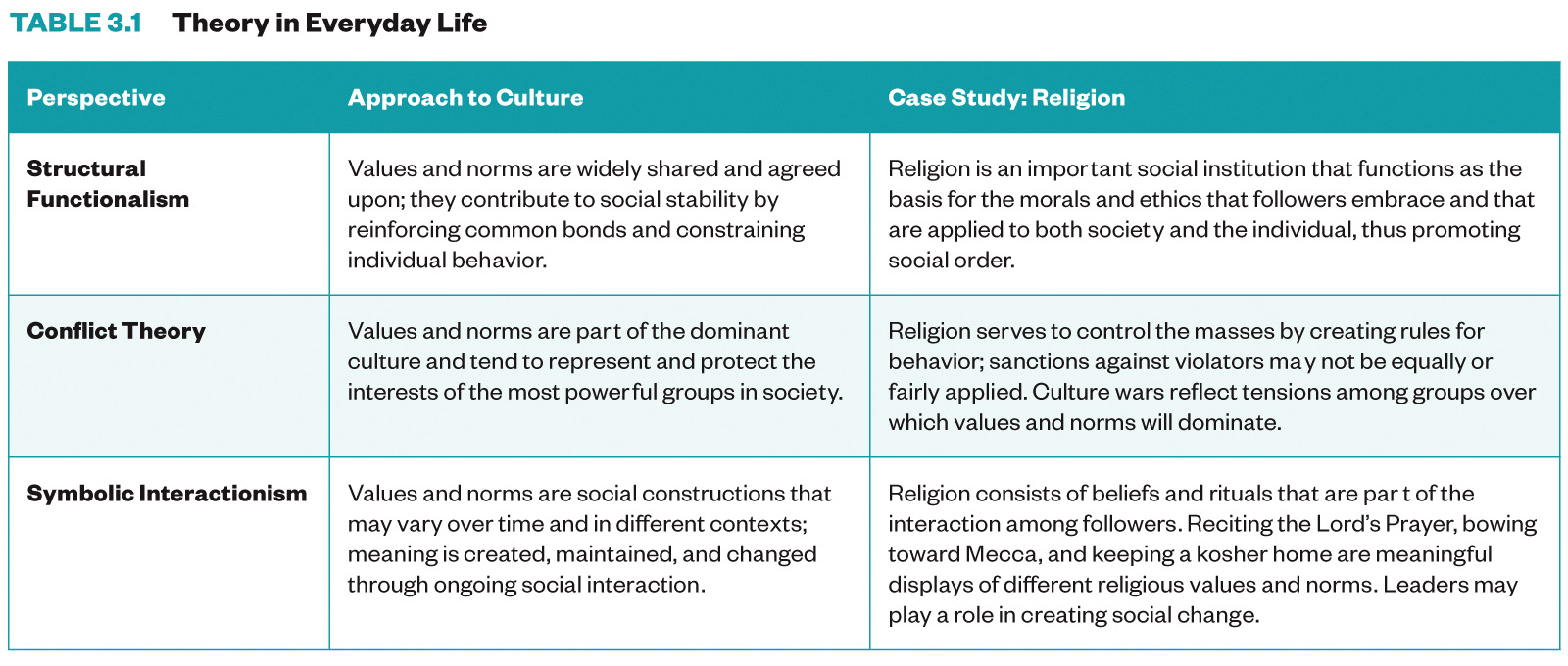

Another illustration of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is seen in sexist language, in which the use of male nouns and pronouns shapes how we think about the world (Miles, 2008). In older children’s books, words like fire man and mail man are common, along with pictures of men in these jobs, and critics say they send a message to children that these are male jobs, not female jobs. If a teacher tells a second-grade class, “Every student should put his books under his desk,” the teacher obviously means students of both sexes but may be sending a subtle message that boys matter more than girls. For these reasons, several guidebooks promote the use of nonsexist language (Maggio, 1998). Table 3.1 “Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives” provides examples of sexist language and nonsexist alternatives.

Table 3.1 Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives

| Term | Alternative |

|---|---|

| Businessman | Businessperson, executive |

| Fireman | Fire fighter |

| Chairman | Chair, chairperson |

| Policeman | Police officer |

| Mailman | Letter carrier, postal worker |

| Mankind | Humankind, people |

| Man-made | Artificial, synthetic |

| Waitress | Server |

| He (as generic pronoun) | He or she; he/she; s/he |

| “A professor should be devoted to his students” | “Professors should be devoted to their students” |

The use of racist language also illustrates the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. An old saying goes, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me.” That may be true in theory but not in reality. Names can hurt, especially names that are racial slurs, which African Americans growing up before the era of the civil rights movement routinely heard. According to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the use of these words would have affected how whites perceived African Americans. More generally, the use of racist terms may reinforce racial prejudice and racial stereotypes.

Sociology Making a Difference

Overcoming Cultural and Ethnic Differences

People from many different racial and ethnic backgrounds live in large countries such as the United States. Because of cultural differences and various prejudices, it can be difficult for individuals from one background to interact with individuals from another background. Fortunately, a line of research, grounded in contact theory and conducted by sociologists and social psychologists, suggests that interaction among individuals from different backgrounds can indeed help overcome tensions arising from their different cultures and any prejudices they may hold. This happens because such contact helps disconfirm stereotypes that people may hold of those from different backgrounds (Dixon, 2006; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2005).

Recent studies of college students provide additional evidence that social contact can help overcome cultural differences and prejudices. Because many students are randomly assigned to their roommates when they enter college, interracial roommates provide a “natural” experiment for studying the effects of social interaction on racial prejudice. Studies of such roommates find that whites with black roommates report lowered racial prejudice and greater numbers of interracial friendships with other students (Laar, Levin, Sinclair, & Sidanius, 2005; Shook & Fazio, 2008).

It is not easy to overcome cultural differences and prejudices, and studies also find that interracial college roommates often have to face many difficulties in overcoming the cultural differences and prejudices that existed before they started living together (Shook & Fazio, 2008). Yet the body of work supporting contact theory suggests that efforts that increase social interaction among people from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds in the long run will reduce racial and ethnic tensions.

Cultures differ widely in their norms , or standards and expectations for behaving. We already saw that the nature of drunken behavior depends on society’s expectations of how people should behave when drunk. Norms of drunken behavior influence how we behave when we drink too much.

Norms are often divided into two types, formal norms and informal norms . Formal norms, also called mores (MOOR-ayz) and laws , refer to the standards of behavior considered the most important in any society. Examples in the United States include traffic laws, criminal codes, and, in a college context, student behavior codes addressing such things as cheating and hate speech. Informal norms, also called folkways and customs , refer to standards of behavior that are considered less important but still influence how we behave. Table manners are a common example of informal norms, as are such everyday behaviors as how we interact with a cashier and how we ride in an elevator.

Many norms differ dramatically from one culture to the next. Some of the best evidence for cultural variation in norms comes from the study of sexual behavior (Edgerton, 1976). Among the Pokot of East Africa, for example, women are expected to enjoy sex, while among the Gusii a few hundred miles away, women who enjoy sex are considered deviant. In Inis Beag, a small island off the coast of Ireland, sex is considered embarrassing and even disgusting; men feel that intercourse drains their strength, while women consider it a burden. Even nudity is considered terrible, and people on Inis Beag keep their clothes on while they bathe. The situation is quite different in Mangaia, a small island in the South Pacific. Here sex is considered very enjoyable, and it is the major subject of songs and stories.

While many societies frown on homosexuality, others accept it. Among the Azande of East Africa, for example, young warriors live with each other and are not allowed to marry. During this time, they often have sex with younger boys, and this homosexuality is approved by their culture. Among the Sambia of New Guinea, young males live separately from females and engage in homosexual behavior for at least a decade. It is felt that the boys would be less masculine if they continued to live with their mothers and that the semen of older males helps young boys become strong and fierce (Edgerton, 1976).

Although many societies disapprove of homosexuality, other societies accept it. This difference illustrates the importance of culture for people’s attitudes.

philippe leroyer – Lesbian & Gay Pride – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Other evidence for cultural variation in norms comes from the study of how men and women are expected to behave in various societies. For example, many traditional societies are simple hunting-and-gathering societies. In most of these, men tend to hunt and women tend to gather. Many observers attribute this gender difference to at least two biological differences between the sexes. First, men tend to be bigger and stronger than women and are thus better suited for hunting. Second, women become pregnant and bear children and are less able to hunt. Yet a different pattern emerges in some hunting-and-gathering societies. Among a group of Australian aborigines called the Tiwi and a tribal society in the Philippines called the Agta, both sexes hunt. After becoming pregnant, Agta women continue to hunt for most of their pregnancy and resume hunting after their child is born (Brettell & Sargent, 2009).

Some of the most interesting norms that differ by culture govern how people stand apart when they talk with each other (Hall & Hall, 2007). In the United States, people who are not intimates usually stand about three to four feet apart when they talk. If someone stands more closely to us, especially if we are of northern European heritage, we feel uncomfortable. Yet people in other countries—especially Italy, France, Spain, and many of the nations of Latin America and the Middle East—would feel uncomfortable if they were standing three to four feet apart. To them, this distance is too great and indicates that the people talking dislike each other. If a U.S. native of British or Scandinavian heritage were talking with a member of one of these societies, they might well have trouble interacting, because at least one of them will be uncomfortable with the physical distance separating them.

Different cultures also have different rituals , or established procedures and ceremonies that often mark transitions in the life course. As such, rituals both reflect and transmit a culture’s norms and other elements from one generation to the next. Graduation ceremonies in colleges and universities are familiar examples of time-honored rituals. In many societies, rituals help signify one’s gender identity. For example, girls around the world undergo various types of initiation ceremonies to mark their transition to adulthood. Among the Bemba of Zambia, girls undergo a month-long initiation ceremony called the chisungu , in which girls learn songs, dances, and secret terms that only women know (Maybury-Lewis, 1998). In some cultures, special ceremonies also mark a girl’s first menstrual period. Such ceremonies are largely absent in the United States, where a girl’s first period is a private matter. But in other cultures the first period is a cause for celebration involving gifts, music, and food (Hathaway, 1997).

Boys have their own initiation ceremonies, some of them involving circumcision. That said, the ways in which circumcisions are done and the ceremonies accompanying them differ widely. In the United States, boys who are circumcised usually undergo a quick procedure in the hospital. If their parents are observant Jews, circumcision will be part of a religious ceremony, and a religious figure called a moyel will perform the circumcision. In contrast, circumcision among the Maasai of East Africa is used as a test of manhood. If a boy being circumcised shows signs of fear, he might well be ridiculed (Maybury-Lewis, 1998).

Are rituals more common in traditional societies than in industrial ones such as the United States? Consider the Nacirema, studied by anthropologist Horace Miner more than 50 years ago (Miner, 1956). In this society, many rituals have been developed to deal with the culture’s fundamental belief that the human body is ugly and in danger of suffering many diseases. Reflecting this belief, every household has at least one shrine in which various rituals are performed to cleanse the body. Often these shrines contain magic potions acquired from medicine men. The Nacirema are especially concerned about diseases of the mouth. Miner writes, “Were it not for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums bleed, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them” (p. 505). Many Nacirema engage in “mouth-rites” and see a “holy-mouth-man” once or twice yearly.

Spell Nacirema backward and you will see that Miner was describing American culture. As his satire suggests, rituals are not limited to preindustrial societies. Instead, they function in many kinds of societies to mark transitions in the life course and to transmit the norms of the culture from one generation to the next.

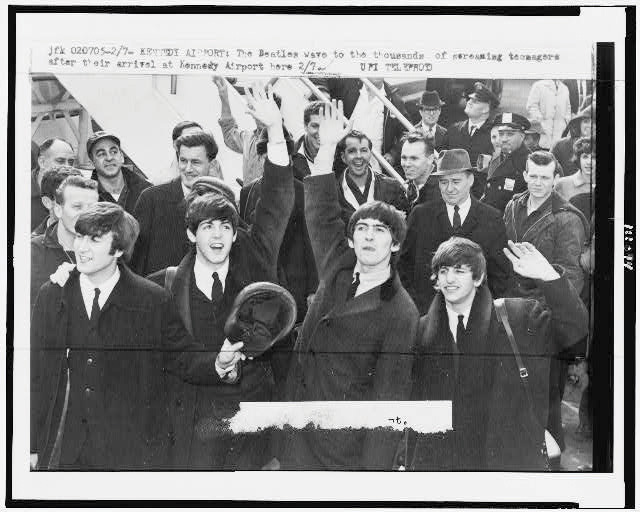

Changing Norms and Beliefs

Our examples show that different cultures have different norms, even if they share other types of practices and beliefs. It is also true that norms change over time within a given culture. Two obvious examples here are hairstyles and clothing styles. When the Beatles first became popular in the early 1960s, their hair barely covered their ears, but parents of teenagers back then were aghast at how they looked. If anything, clothing styles change even more often than hairstyles. Hemlines go up, hemlines go down. Lapels become wider, lapels become narrower. This color is in, that color is out. Hold on to your out-of-style clothes long enough, and eventually they may well end up back in style.

Some norms may change over time within a given culture. In the early 1960s, the hair of the four members of the Beatles barely covered their ears, but many parents of U.S. teenagers were very critical of the length of their hair.

U.S. Library of Congress – public domain.

A more important topic on which norms have changed is abortion and birth control (Bullough & Bullough, 1977). Despite the controversy surrounding abortion today, it was very common in the ancient world. Much later, medieval theologians generally felt that abortion was not murder if it occurred within the first several weeks after conception. This distinction was eliminated in 1869, when Pope Pius IX declared abortion at any time to be murder. In the United States, abortion was not illegal until 1828, when New York state banned it to protect women from unskilled abortionists, and most other states followed suit by the end of the century. However, the sheer number of unsafe, illegal abortions over the next several decades helped fuel a demand for repeal of abortion laws that in turn helped lead to the Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision in 1973 that generally legalized abortion during the first two trimesters.

Contraception was also practiced in ancient times, only to be opposed by early Christianity. Over the centuries, scientific discoveries of the nature of the reproductive process led to more effective means of contraception and to greater calls for its use, despite legal bans on the distribution of information about contraception. In the early 1900s, Margaret Sanger, an American nurse, spearheaded the growing birth-control movement and helped open a birth-control clinic in Brooklyn in 1916. She and two other women were arrested within 10 days, and Sanger and one other defendant were sentenced to 30 days in jail. Efforts by Sanger and other activists helped to change views on contraception over time, and finally, in 1965, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut that contraception information could not be banned. As this brief summary illustrates, norms about contraception changed dramatically during the last century.

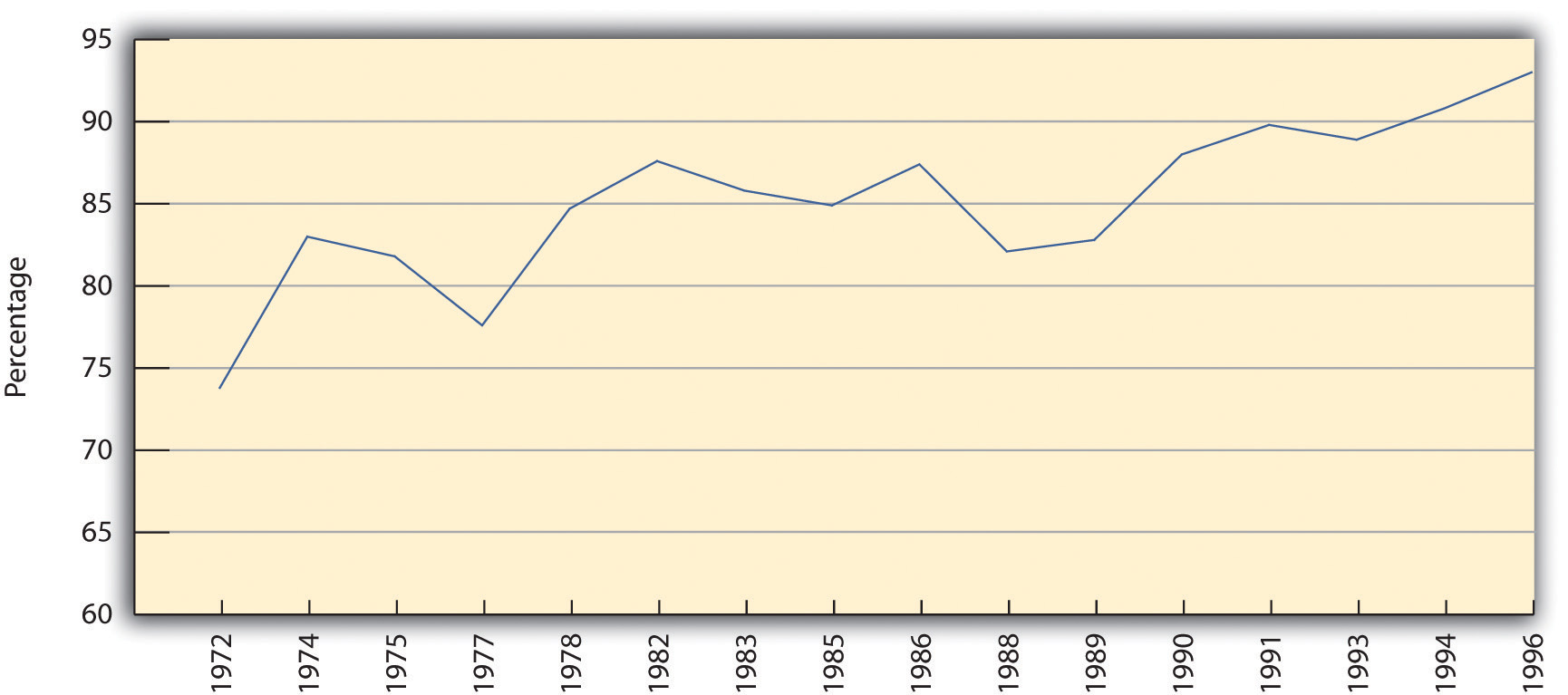

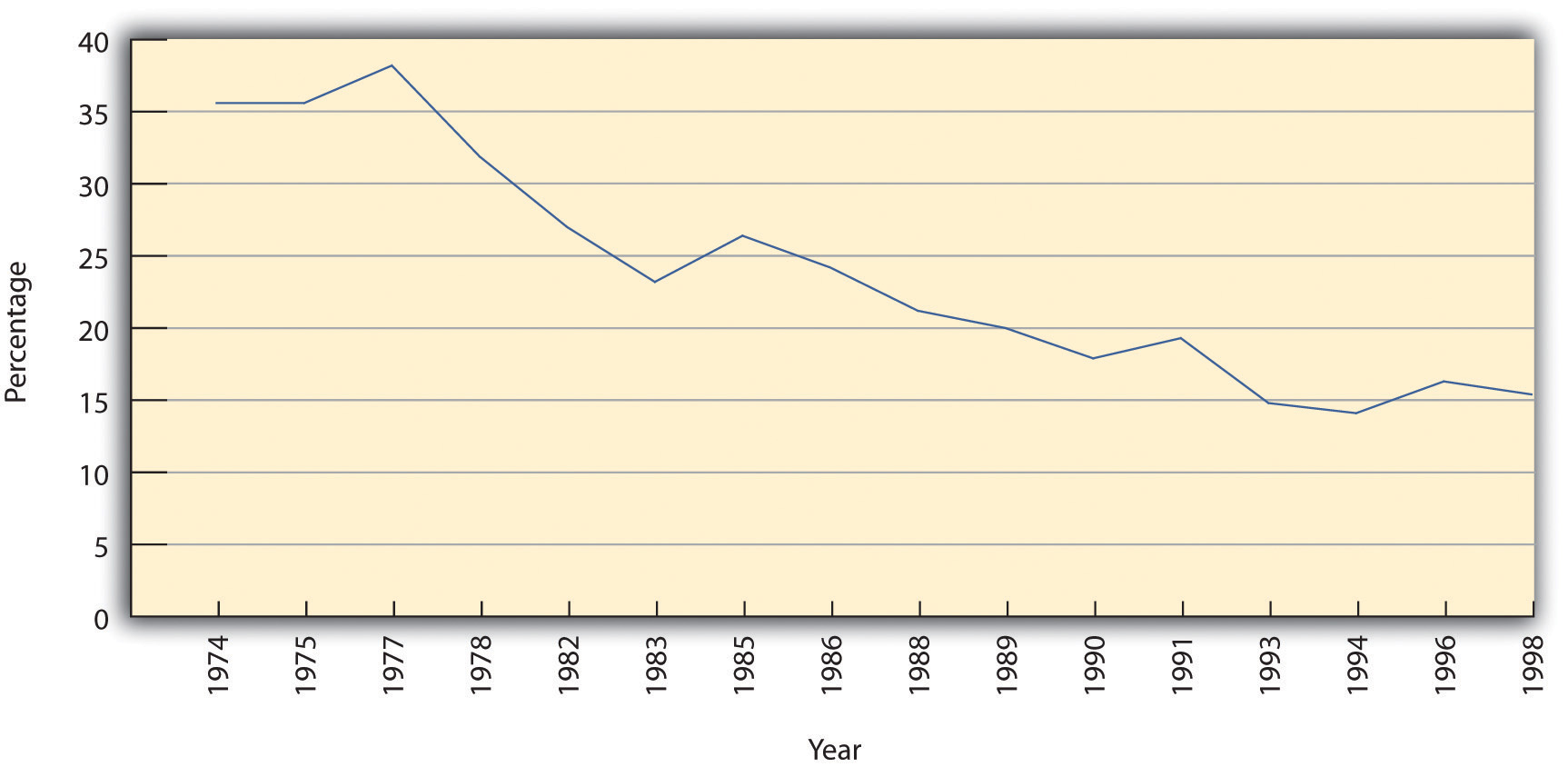

Other types of cultural beliefs also change over time ( Figure 3.2 “Percentage of People Who Say They Would Vote for a Qualified African American for President” and Figure 3.3 “Percentage of People Who Agree Women Should Take Care of Running Their Homes” ). Since the 1960s, the U.S. public has changed its views about some important racial and gender issues. Figure 3.2 “Percentage of People Who Say They Would Vote for a Qualified African American for President” , taken from several years of the General Social Survey (GSS), shows that the percentage of Americans who would vote for a qualified black person as president rose almost 20 points from the early 1970s to the middle of 1996, when the GSS stopped asking the question. If beliefs about voting for an African American had not changed, Barack Obama would almost certainly not have been elected in 2008. Figure 3.3 “Percentage of People Who Agree Women Should Take Care of Running Their Homes” , also taken from several years of the GSS, shows that the percentage saying that women should take care of running their homes and leave running the country to men declined from almost 36% in the early 1970s to only about 15% in 1998, again, when the GSS stopped asking the question. These two figures depict declining racial and gender prejudice in the United States during the past quarter-century.

Figure 3.2 Percentage of People Who Say They Would Vote for a Qualified African American for President

Source: Data from General Social Surveys, 1972–1996.

Figure 3.3 Percentage of People Who Agree Women Should Take Care of Running Their Homes

Source: Data from General Social Surveys, 1974–1998.

Values are another important element of culture and involve judgments of what is good or bad and desirable or undesirable. A culture’s values shape its norms. In Japan, for example, a central value is group harmony. The Japanese place great emphasis on harmonious social relationships and dislike interpersonal conflict. Individuals are fairly unassertive by American standards, lest they be perceived as trying to force their will on others (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). When interpersonal disputes do arise, Japanese do their best to minimize conflict by trying to resolve the disputes amicably. Lawsuits are thus uncommon; in one case involving disease and death from a mercury-polluted river, some Japanese who dared to sue the company responsible for the mercury poisoning were considered bad citizens (Upham, 1976).

Individualism in the United States

American culture promotes competition and an emphasis on winning in the sports and business worlds and in other spheres of life. Accordingly, lawsuits over frivolous reasons are common and even expected.

Clyde Robinson – Courtroom – CC BY 2.0.

In the United States, of course, the situation is quite different. The American culture extols the rights of the individual and promotes competition in the business and sports worlds and in other areas of life. Lawsuits over the most frivolous of issues are quite common and even expected. Phrases like “Look out for number one!” abound. If the Japanese value harmony and group feeling, Americans value competition and individualism. Because the Japanese value harmony, their norms frown on self-assertion in interpersonal relationships and on lawsuits to correct perceived wrongs. Because Americans value and even thrive on competition, our norms promote assertion in relationships and certainly promote the use of the law to address all kinds of problems.

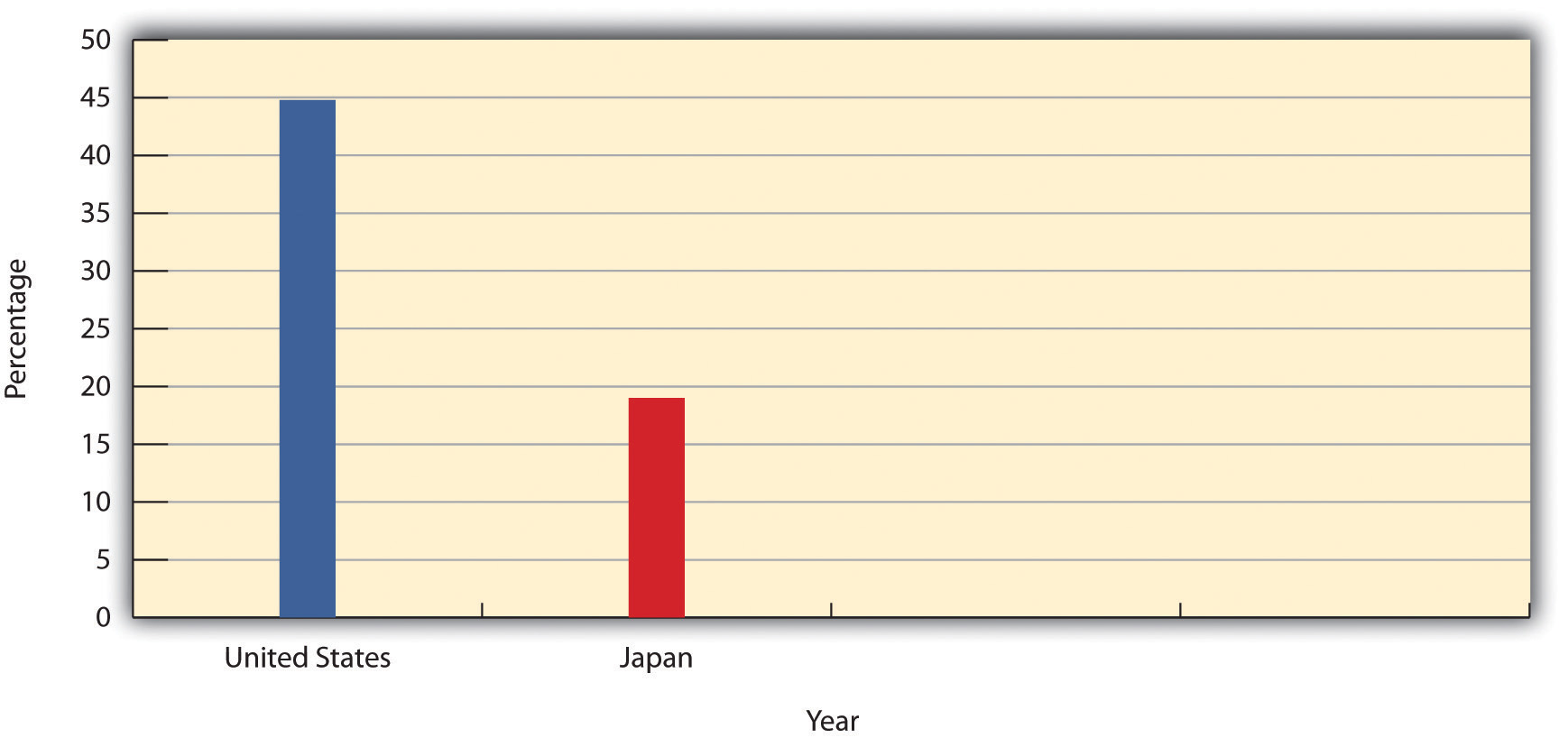

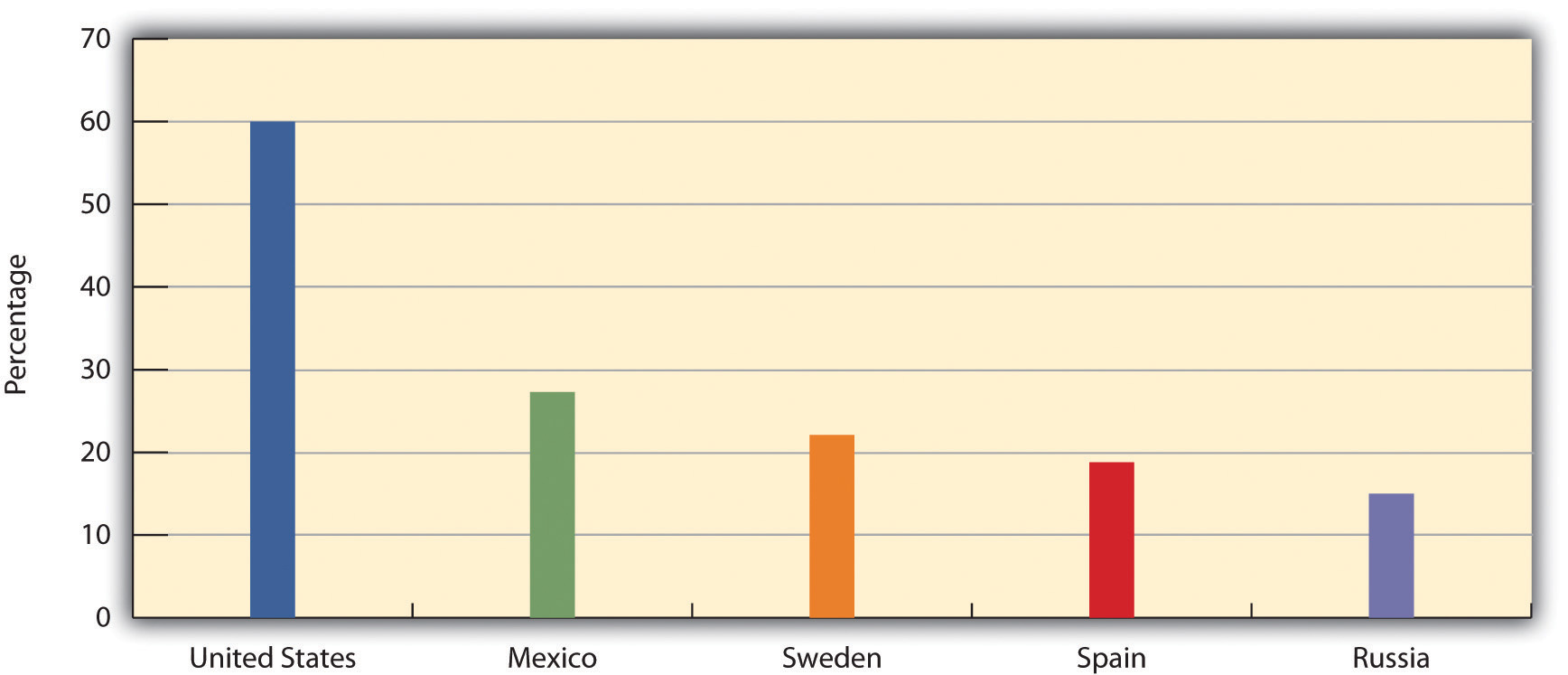

Figure 3.4 “Percentage of People Who Think Competition Is Very Beneficial” illustrates this difference between the two nations’ cultures with data from the 2002 World Values Survey (WVS), which was administered to random samples of the adult populations of more than 80 nations around the world. One question asked in these nations was, “On a scale of one (‘competition is good; it stimulates people to work hard and develop new ideas’) to ten (‘competition is harmful; it brings out the worst in people’), please indicate your views on competition.” Figure 3.4 “Percentage of People Who Think Competition Is Very Beneficial” shows the percentages of Americans and Japanese who responded with a “one” or “two” to this question, indicating they think competition is very beneficial. Americans are about three times as likely as Japanese to favor competition.

Figure 3.4 Percentage of People Who Think Competition Is Very Beneficial

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 2002.

The Japanese value system is a bit of an anomaly, because Japan is an industrial nation with very traditional influences. Its emphasis on group harmony and community is more usually thought of as a value found in traditional societies, while the U.S. emphasis on individuality is more usually thought of as a value found in industrial cultures. Anthropologist David Maybury-Lewis (1998, p. 8) describes this difference as follows: “The heart of the difference between the modern world and the traditional one is that in traditional societies people are a valuable resource and the interrelations between them are carefully tended; in modern society things are the valuables and people are all too often treated as disposable.” In industrial societies, continues Maybury-Lewis, individualism and the rights of the individual are celebrated and any one person’s obligations to the larger community are weakened. Individual achievement becomes more important than values such as kindness, compassion, and generosity.

Other scholars take a less bleak view of industrial society, where they say the spirit of community still lives even as individualism is extolled (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985). In American society, these two simultaneous values sometimes create tension. In Appalachia, for example, people view themselves as rugged individuals who want to control their own fate. At the same time, they have strong ties to families, relatives, and their neighbors. Thus their sense of independence conflicts with their need for dependence on others (Erikson, 1976).

The Work Ethic

Another important value in the American culture is the work ethic. By the 19th century, Americans had come to view hard work not just as something that had to be done but as something that was morally good to do (Gini, 2000). The commitment to the work ethic remains strong today: in the 2008 General Social Survey, 72% of respondents said they would continue to work even if they got enough money to live as comfortably as they would like for the rest of their lives.

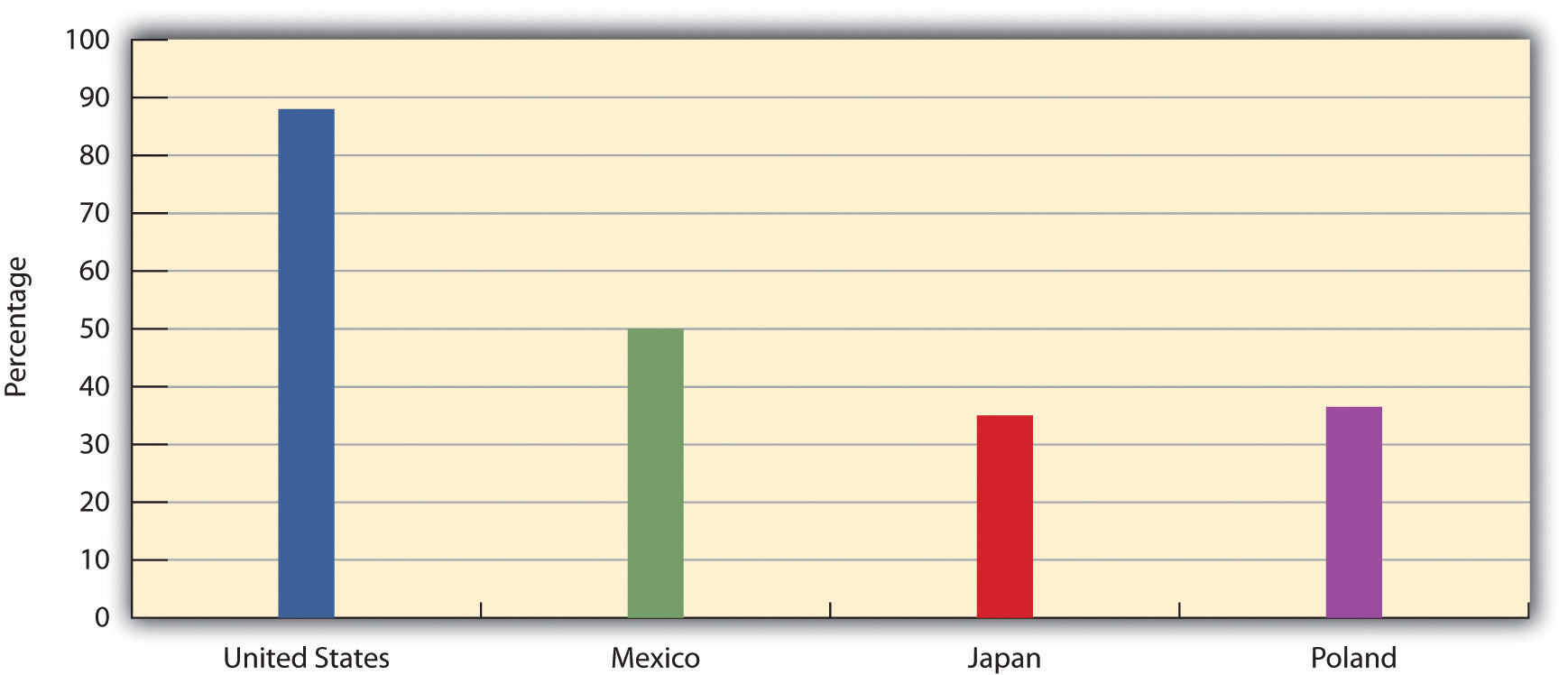

Cross-cultural evidence supports the importance of the work ethic in the United States. Using earlier World Values Survey data, Figure 3.5 “Percentage of People Who Take a Great Deal of Pride in Their Work” presents the percentage of people in United States and three other nations from different parts of the world—Mexico, Poland, and Japan—who take “a great deal of pride” in their work. More than 85% of Americans feel this way, compared to much lower proportions of people in the other three nations.

Figure 3.5 Percentage of People Who Take a Great Deal of Pride in Their Work

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 1993.

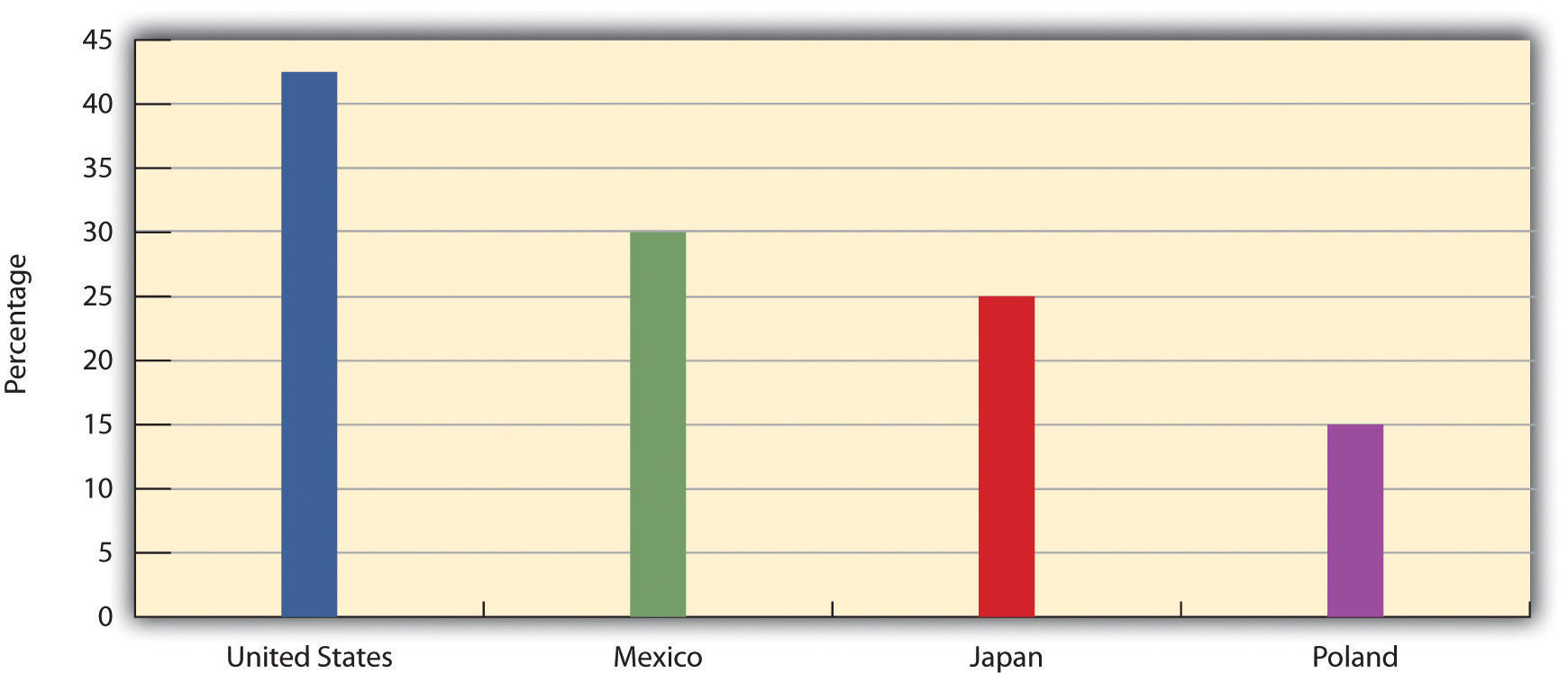

Closely related to the work ethic is the belief that if people work hard enough, they will be successful. Here again the American culture is especially thought to promote the idea that people can pull themselves up by their “bootstraps” if they work hard enough. The WVS asked whether success results from hard work or from luck and connections. Figure 3.6 “Percentage of People Who Think Hard Work Brings Success” presents the proportions of people in the four nations just examined who most strongly thought that hard work brings success. Once again we see evidence of an important aspect of the American culture, as U.S. residents were especially likely to think that hard work brings success.

Figure 3.6 Percentage of People Who Think Hard Work Brings Success

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 1997.

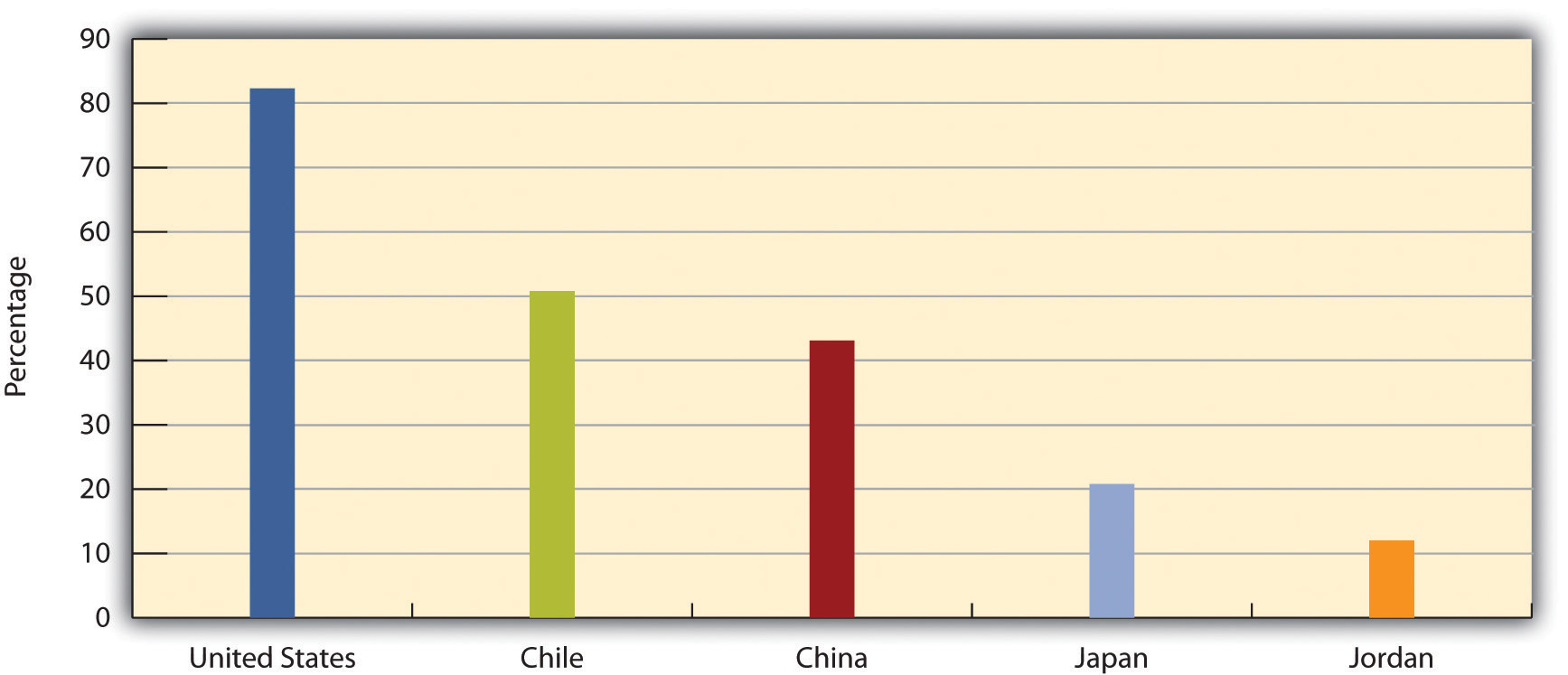

If Americans believe hard work brings success, then they should be more likely than people in most other nations to believe that poverty stems from not working hard enough. True or false, this belief is an example of the blaming-the-victim ideology introduced in Chapter 1 “Sociology and the Sociological Perspective” . Figure 3.7 “Percentage of People Who Attribute Poverty to Laziness and Lack of Willpower” presents WVS percentages of respondents who said the most important reason people are poor is “laziness and lack of willpower.” As expected, Americans are much more likely to attribute poverty to not working hard enough.

Figure 3.7 Percentage of People Who Attribute Poverty to Laziness and Lack of Willpower

We could discuss many other values, but an important one concerns how much a society values women’s employment outside the home. The WVS asked respondents whether they agree that “when jobs are scarce men should have more right to a job than women.” Figure 3.8 “Percentage of People Who Disagree That Men Have More Right to a Job Than Women When Jobs Are Scarce” shows that U.S. residents are more likely than those in nations with more traditional views of women to disagree with this statement.

Figure 3.8 Percentage of People Who Disagree That Men Have More Right to a Job Than Women When Jobs Are Scarce

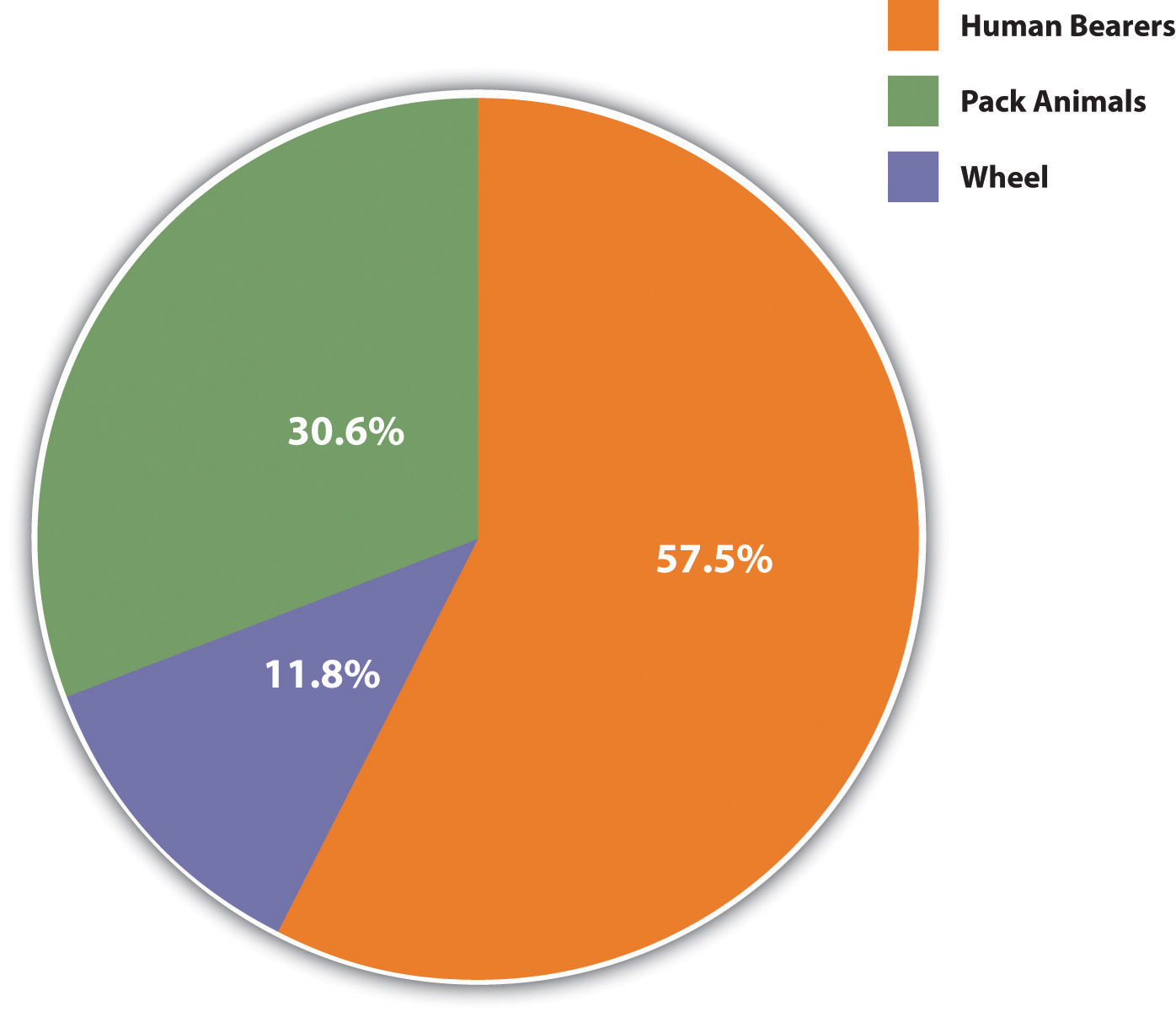

The last element of culture is the artifacts , or material objects, that constitute a society’s material culture. In the most simple societies, artifacts are largely limited to a few tools, the huts people live in, and the clothing they wear. One of the most important inventions in the evolution of society was the wheel. Figure 3.9 “Primary Means of Moving Heavy Loads” shows that very few of the societies in the SCCS use wheels to move heavy loads over land, while the majority use human power and about one-third use pack animals.

Figure 3.9 Primary Means of Moving Heavy Loads

Although the wheel was a great invention, artifacts are much more numerous and complex in industrial societies. Because of technological advances during the past two decades, many such societies today may be said to have a wireless culture, as smartphones, netbooks and laptops, and GPS devices now dominate so much of modern life. The artifacts associated with this culture were unknown a generation ago. Technological development created these artifacts and new language to describe them and the functions they perform. Today’s wireless artifacts in turn help reinforce our own commitment to wireless technology as a way of life, if only because children are now growing up with them, often even before they can read and write.

The iPhone is just one of the many notable cultural artifacts in today’s wireless world. Technological development created these artifacts and new language to describe them and their functions—for example, “There’s an app for that!”

Philip Brooks – iPhone – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Sometimes people in one society may find it difficult to understand the artifacts that are an important part of another society’s culture. If a member of a tribal society who had never seen a cell phone, or who had never even used batteries or electricity, were somehow to visit the United States, she or he would obviously have no idea of what a cell phone was or of its importance in almost everything we do these days. Conversely, if we were to visit that person’s society, we might not appreciate the importance of some of its artifacts.

In this regard, consider once again India’s cows, discussed in the news article that began this chapter. As the article mentioned, people from India consider cows holy, and they let cows roam the streets of many cities. In a nation where hunger is so rampant, such cow worship is difficult to understand, at least to Americans, because a ready source of meat is being ignored.

Anthropologist Marvin Harris (1974) advanced a practical explanation for India’s cow worship. Millions of Indians are peasants who rely on their farms for their food and thus their existence. Oxen and water buffalo, not tractors, are the way they plow their fields. If their ox falls sick or dies, farmers may lose their farms. Because, as Harris observes, oxen are made by cows, it thus becomes essential to preserve cows at all costs. In India, cows also act as an essential source of fertilizer, to the tune of 700 million tons of manure annually, about half of which is used for fertilizer and the other half of which is used as fuel for cooking. Cow manure is also mixed with water and used as flooring material over dirt floors in Indian households. For all of these reasons, cow worship is not so puzzling after all, because it helps preserve animals that are very important for India’s economy and other aspects of its way of life.

According to anthropologist Marvin Harris, cows are worshipped in India because they are such an important part of India’s agricultural economy.

Francisco Martins – Cow in Mumbai – CC BY-NC 2.0.

If Indians exalt cows, many Jews and Muslims feel the opposite about pigs: they refuse to eat any product made from pigs and so obey an injunction from the Old Testament of the Bible and from the Koran. Harris thinks this injunction existed because pig farming in ancient times would have threatened the ecology of the Middle East. Sheep and cattle eat primarily grass, while pigs eat foods that people eat, such as nuts, fruits, and especially grains. In another problem, pigs do not provide milk and are much more difficult to herd than sheep or cattle. Next, pigs do not thrive well in the hot, dry climate in which the people of the Old Testament and Koran lived. Finally, sheep and cattle were a source of food back then because beyond their own meat they provided milk, cheese, and manure, and cattle were also used for plowing. In contrast, pigs would have provided only their own meat. Because sheep and cattle were more “versatile” in all of these ways, and because of the other problems pigs would have posed, it made sense for the eating of pork to be prohibited.

In contrast to Jews and Muslims, at least one society, the Maring of the mountains of New Guinea, is characterized by “pig love.” Here pigs are held in the highest regard. The Maring sleep next to pigs, give them names and talk to them, feed them table scraps, and once or twice every generation have a mass pig sacrifice that is intended to ensure the future health and welfare of Maring society. Harris explains their love of pigs by noting that their climate is ideally suited to raising pigs, which are an important source of meat for the Maring. Because too many pigs would overrun the Maring, their periodic pig sacrifices help keep the pig population to manageable levels. Pig love thus makes as much sense for the Maring as pig hatred did for people in the time of the Old Testament and the Koran.

Key Takeaways

- The major elements of culture are symbols, language, norms, values, and artifacts.

- Language makes effective social interaction possible and influences how people conceive of concepts and objects.

- Major values that distinguish the United States include individualism, competition, and a commitment to the work ethic.

For Your Review

- How and why does the development of language illustrate the importance of culture and provide evidence for the sociological perspective?

- Some people say the United States is too individualistic and competitive, while other people say these values are part of what makes America great. What do you think? Why?

Axtell, R. E. (1998). Gestures: The do’s and taboos of body language around the world . New York, NY: Wiley.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brettell, C. B., & Sargent, C. F. (Eds.). (2009). Gender in cross-cultural perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brown, R. (2009, January 24). Nashville voters reject a proposal for English-only. The New York Times , p. A12.

Bullough, V. L., & Bullough, B. (1977). Sin, sickness, and sanity: A history of sexual attitudes . New York, NY: New American Library.

Dixon, J. C. (2006). The ties that bind and those that don’t: Toward reconciling group threat and contact theories of prejudice. Social Forces, 84, 2179–2204.

Edgerton, R. (1976). Deviance: A cross-cultural perspective . Menlo Park, CA: Cummings.

Erikson, K. T. (1976). Everything in its path: Destruction of community in the Buffalo Creek flood . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Gini, A. (2000). My job, my self: Work and the creation of the modern individual . New York, NY: Routledge.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, M. R. (2007). The sounds of silence. In J. M. Henslin (Ed.), Down to earth sociology: Introductory readings (pp. 109–117). New York, NY: Free Press.

Harris, M. (1974). Cows, pigs, wars, and witches: The riddles of culture . New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Hathaway, N. (1997). Menstruation and menopause: Blood rites. In L. M. Salinger (Ed.), Deviant behavior 97/98 (pp. 12–15). Guilford, CT: Dushkin.

Laar, C. V., Levin, S., Sinclair, S., & Sidanius, J. (2005). The effect of university roommate contact on ethnic attitudes and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 329–345.

Maggio, R. (1998). The dictionary of bias-free usage: A guide to nondiscriminatory language . Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Maybury-Lewis, D. (1998). Tribal wisdom. In K. Finsterbusch (Ed.), Sociology 98/99 (pp. 8–12). Guilford, CT: Dushkin/McGraw-Hill.

Miles, S. (2008). Language and sexism . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Miner, H. (1956). Body ritual among the Nacirema. American Anthropologist, 58, 503–507.

Murdock, G. P., & White, D. R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8, 329–369.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2005). Allport’s intergroup contact hypothesis: Its history and influence. In J. F. Dovidio, P. S. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 262–277). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Ray, S. (2007). Politics over official language in the United States. International Studies, 44, 235–252.

Schneider, L., & Silverman, A. (2010). Global sociology: Introducing five contemporary societies (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Shook, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Interracial roommate relationships: An experimental test of the contact hypothesis. Psychological Science, 19, 717–723.

Shook, N. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Roommate relationships: A comparison of interracial and same-race living situations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 11, 425–437.

Upham, F. K. (1976). Litigation and moral consciousness in Japan: An interpretive analysis of four Japanese pollution suits. Law and Society Review, 10, 579–619.

Whorf, B. (1956). Language, thought and reality . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Sociology of Culture

Introduction, general overviews.

- Edited Volumes

- Classic Statements

- Contemporary Statements

- Methodology in Cultural Analysis

- The Culture-Structure Connection

- Belief and Cognition

- Symbolism and Ritual

- Categories and Boundaries

- Social Stratification

- Social Networks

- Organizations and Institutions

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Consumer Culture

- Critical Sociology of Knowledge

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Culture and Networks

- Erving Goffman

- Émile Durkheim

- Political Culture

- Popular Culture

- Public Opinion

- Social History

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Global Racial Formations

- Transition to Parenthood in the Life Course

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Sociology of Culture by Brian Steensland LAST REVIEWED: 27 July 2011 LAST MODIFIED: 27 July 2011 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0055

Culture is the symbolic-expressive dimension of social life. In common usage, the term “culture” can mean the cultivation associated with “civilized” habits of mind, the creative products associated with the arts, or the entire way of life associated with a group. Among sociologists, “culture” just as often refers to the beliefs that people hold about reality, the norms that guide their behavior, the values that orient their moral commitments, or the symbols through which these beliefs, norms, and values are communicated. The sociological study of culture encompasses all these diverse meanings of “culture.” Amid this diversity, what unifies the sociology of culture are two core commitments: that the symbolic-expressive dimension of social life is worthy of examination, both for its own sake and because of its impact on other aspects of social life; and that culture can be studied using the methods and analytic tools of sociology. Within the discipline, the sociology of culture emerged as a bounded subfield during the 1980s. Prior to this period, sociological analyses of culture were found mainly in theoretical treatises and in empirical studies of religion, the arts, and the “sociology of knowledge.” Throughout, the sociological study of culture has been oriented by a common set of broad questions: What are the social origins of culture? What cultural patterns are found in various groups and institutions? And what influence does culture have on important aspects of society? Scholarship in the sociology of culture ranges from highly general conceptual arguments to closely observed empirical studies. The readings included here reflect this breadth.

Overviews of the sociology of culture take a variety of forms. Griswold 2008 is a popular introduction to key concepts and debates. It also gives sustained attention to the arts and cultural industries. Battani, et al. 2003 provides broad coverage, with special attention to politics and power dynamics. Smith and Riley 2009 contains the best introduction to general theories of culture and their relations to one another. A recent special volume on cultural sociology, Binder, et al. 2008 , provides an introduction of a different sort. It collects review articles on the intersection between cultural analysis and other topical areas within sociology.

Battani, Marshall, John R. Hall, and Mary Jo Neitz. 2003. Sociology on culture . New York: Routledge.

A broad overview of the sociology of culture with particular emphasis on stratification, modernity, power dynamics, and social change.

Binder, Amy, Mary Blair-Loy, John H. Evans, Kwai Ng, and Michael Schudson, eds. 2008. Cultural sociology and its diversity . Annals of the Academy of Political and Social Science 619. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

A recent collection of papers describing how cultural approaches have been incorporated into a wide range of topical areas in sociology, including the law, education, science, sexuality, economic markets, formal organizations, social movements, popular culture, and race and ethnicity.

Griswold, Wendy. 2008. Cultures and societies in a changing world . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

A clear and concise introduction to the sociological study of culture. Particularly strong on outlining the multiple meanings of “culture” and showing the value of conceptualizing cultural processes using Griswold’s “cultural diamond” analytic framework.

Smith, Philip, and Alexander Riley. 2009. Cultural theory: An introduction . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

An exhaustive yet accessible introduction to cultural theory in its many manifestations. An indispensable guide to complex conceptual terrain.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Causal Inference

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights

- Civil Society

- Cognitive Sociology

- Cohort Analysis

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Conservatism

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Consumption

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Doing Gender

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Globalization

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Economic Sociology

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Family Policies

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender Stratification

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Global Inequalities

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Intersectionalities

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law and Society

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- LGBT Social Movements

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marriage and Divorce

- Marxist Sociology

- Masculinity

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Mathematical Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multilevel Models

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Nationalism

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Panel Studies

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Space

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexual Identity

- Sexualities

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Closure

- Social Construction of Crime

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social Indicators

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Psychology

- Social Theory

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Survey Methods

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Welfare States

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [81.177.182.159]

- 81.177.182.159

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays on the sociology of culture

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

3 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station21.cebu on September 2, 2019

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Essays on the Sociology of Culture

DOI link for Essays on the Sociology of Culture

Get Citation

Karl Mannheim was one of the leading sociologists of the twentieth century. Essays on the Sociology of Culture , originally published in 1956, was one of his most important books. In it he sets out his ideas of intellectuals as producers of culture and explores the possibilities of a democratization of culture. This new edition includes a superb new preface by Bryan Turner which sets Mannheim's study in the appropriate historical and intellectual context and explains why his thought on culture remains essential for students engaged in debates about mass culture, the politics of culture and postmodernity.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter | 13 pages, introduction, part | 75 pages, towards the sociology of the mind, chapter | 11 pages, first approach to the subject, chapter | 34 pages, the false and the proper concepts of history and society, chapter | 23 pages, the proper and improper concept of the mind, chapter | 6 pages, an outline of the sociology of the mind, chapter | 1 pages, recapitulation: the sociology of the mind as an area of inquiry, part | 80 pages, the problem of the intelligentsia, part | 76 pages, the democratization of culture 1, chapter | 4 pages, some problems of political democracy at the stage of its full development, chapter | 72 pages, the problem of democratization as a general cultural phenomenon.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Culture in Sociology (Definition, Types and Features)

Sourabh Yadav (MA)

Sourabh Yadav is a freelance writer & filmmaker. He studied English literature at the University of Delhi and Jawaharlal Nehru University. You can find his work on The Print, Live Wire, and YouTube.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

Culture, as used in sociology, is the “way of life” of a particular group of people: their values, beliefs, norms, etc.

Think of a typical day in your life. You wake up, get ready, and then leave for school or work. Once the day is over, you probably spend your time with family/friends or pursue your hobbies.

Almost every aspect of this—your means of travel, how you behave among your colleagues, or what kind of recreation you prefer—comes under culture. It is something that we acquire socially and plays a huge role in shaping who we are.

Sociologists have come up with various theories about culture (why it exists, how it functions, etc.), which we will discuss later. But before that, let us learn about the concept in more detail and look at some examples.

Sociological Definition of Culture

Edward Tylor defined culture as

“that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” (1871)

Another definition comes from Scott, who sees culture as “all that in human society which is socially rather than biologically transmitted” (2014).

Since the beginning of civilization, humans have lived together in communities and developed common ways of dealing with life (acquiring food, raising children, etc.). These common ways are what make culture.

Culture consists of both intangible and tangible things. The former is known as nonmaterial culture, which includes things like ideas or values of a society. In contrast, material culture has a physical existence, such as a clothing item.

Both nonmaterial and material are linked because physical items often symbolize cultural ideas (Little, 2016). For example, you wear a suit (not a pair of shorts) to a business meeting, which is linked to the workplace values of formality & decorum.

Two of the most important elements of culture are its values & beliefs. Values refer to what a society considers good and just: individuality, for example, is a key value in most Western countries. Beliefs are the convictions that people hold to be true, such as the American belief that hard work can make anybody successful.

Values and beliefs are deeply entrenched in a culture, and going against them can have consequences. These can range from minor cultural sanctions (say being frowned upon) to major legal actions. In contrast, upholding values & beliefs leads to social approval.

Cultural values differ across cultures. The individualism of Western cultures seems solipsistic & arrogant to many Non-Western cultures, who instead value collectivism. Besides such variations, values also evolve with time.

Culture vs Society

The terms “culture” and “society” are often used interchangeably in everyday speech, but they refer to different things.

Society refers to a group of people who live together in a common territory & share a culture. This common territory can be any definable region, say a small neighborhood or a large country.

When we use the term “society”, we are referring to social structures & their organization.

Culture, in contrast, is the “way of life” of a group of people; it consists of values, beliefs, and artifacts.

For example, in the United States, African-Americans have historically been oppressed, and even today, they often do not get equal opportunities. Here, we are talking about social structures, which include race and class.

African-American culture has—such as the literary works of Zora Neale Hurston or the jazz music of Duke Ellington—developed in response to these (unfair) social structures. So, both society & culture are mutually connected; neither can exist without the other.

Features of Cultures

The following are 10 key features of culture that we explore in sociology:

- Symbols: Symbols can be words, gestures, or objects that carry particular meanings recognized by those who share the same culture. For instance, the bald eagle functions as a symbol of freedom and authority in American culture .

- Language: Language is a key aspect of culture, as it is the means of communication that conveys cultural heritage and values. For example, the French language, rich in literature and philosophy, reveals much about French culture’s emphasis on art, intellect, and romance.

- Rituals and Traditions: These are practices or ceremonies that are regularly performed in a culture and bear symbolic meaning. An example of a ritual would be Diwali, the festival of lights celebrated by Hindus, symbolizes the spiritual victory of light over darkness, good over evil.

- Norms: Norms are behavioral standards and expectations that culture sets. In British culture, for instance, queueing is a significant societal norm, signifying order and fairness. See: cultural norms .

- Values: These are the learned beliefs that guide individual and collective behavior and decisions, such as respect for human rights evident in many democratic societies. See: cultural values .

- Social Structures: Social structures are the arranged relationships and patterned interactions between members of a culture, like the extended family system prevalent in many Latin American cultures.

- Artifacts: Physical objects or architectural structures that represent cultural accomplishments, such as the Pyramids in Egypt representing ancient Egyptian civilization. See: cultural artifacts .

- Rules and Laws: Codified principles that guide societal behavior. For example, the constitution in the U.S. reflects its cultural emphasis on democracy and individual freedom.

- Religion and Spirituality: Beliefs about a higher power, rituals related to this belief, and moral codes derived from these beliefs. Buddhism, for instance, is a significant part of East Asian cultures.

- Food and Diet: Specific to each culture, these are dietary habits and special cuisines, like the Mediterranean diet filled with seafood, olives, and vegetables, reflecting coastal cultures of Greece and Italy.

Types of Culture in Sociology

- National Culture: This represents the shared customs, behaviors, and artifacts that characterize a nation, for instance, the Brazilian culture marked by energetic music and vibrant festivals.

- Subculture : A cultural group existing within larger cultures distinguished by their unique practices and beliefs. For example, The Amish in the United States have a distinct lifestyle centered around simplicity and community.

- Counterculture : This represents groups that reject mainstream norms and values, seeking to challenge the status quo. The Punk movement of the 1970s in the UK, known for its rebellious attitudes and alternative fashion, is a clear example. Countercultures often cause widespread moral panic among the dominant culture in a society .

- Folk Culture : Traditional, community-based customs representing the shared cultural heritage, such as folk music and folklore of Irish culture.

- Pop Culture : Mainstream trends influenced by mass media, fashion, and celebrities, like K-Pop’s influence on global music and fashion trends.

- High Culture : Artifacts and activities considered ‘refined’ or ‘sophisticated’ by elite society, such as opera and ballet in European cultures (Bourdieu, 2010). This is contrasted to low culture , which represents the culture of the working-class.

- Material Culture : Tangible artifacts of human society like architecture, fashion, or food. The medieval castles peppered throughout France offer insight into its material culture. This is of great concern, for example, to archaeologists.

- Non-Material Culture : Intangible aspects of a culture, such as values and norms. The continued emphasis on politeness in British culture is an example of this. This is of great concern, for example, to sociocultural anthropologists.

- Professional Culture: Standards and behaviors specific to a particular profession. The Hippocratic Oath and an emphasis on patient care are integral to medical culture.

- Organizational Culture: Refers to the shared values, beliefs, and behaviors that form the unique social and psychological environment of an organization. Google’s culture of innovation and employee freedom reflects this.

For More, Read: 17 Types of Culture

Theoretical Approaches to Culture in Sociology

Sociologists have come up with various theories of culture, explaining why and how they exist.

1. Functionalism

Functionalism sees society as a group of elements that function together to maintain a stable whole.

Émile Durkheim, one of the founders of sociology, used an organic analogy to explain this. In a biological creature, all the constituent body parts work together to maintain an organic whole; in the same way, the parts of a society work together to ensure its stability.

Under such a view, culture is something that helps society to exist as a stable entity: cultural norms, for example, guide people’s behavior and ensure that they appropriately. Talcott Parsons said that culture performs “latent pattern maintenance”, meaning that it maintains social patterns of behavior and allows orderly change (Little).

To put it in one sentence, culture ensures that our “way of life” remains stable. Functionalism can provide excellent insights into all cultural expressions, even ones that seem quite irrational. For example, sports in themselves may seem quite “useless”.

What exactly is the point of trying to hit a ball far or kicking one into a net? Functionalists would explain that sports brings people together and creates a collective experience. It provides an outlet for aggressive energies, teaches us the value of teamwork, and of course, makes us physically fit.

Real culture allows a given society to see how far its aspirations lie from its achievements, allowing it to take redressal steps.

Read More about Functionalism in Sociology Here

2. Conflict Theory

Conflict theory focuses on the power relations that exist in society and believes that culture is entrenched in this power play.

These sociologists emphasize the unequal nature of social structures, and how they are related to factors of class, race, gender, etc. For them, culture is another tool for reinforcing and perpetuating these differences.

A key focus of conflict theory is on critiquing “ideology”, which is seen as a set of ideas that support or conceal the existing power relations in society. For example, as we discussed earlier, one of the key beliefs in the United States is the “American Dream”: anyone can work hard to achieve success.

But this belief hardly takes into account larger social factors (historical oppression, generational wealth, etc.). For a white, middle-class man, it may certainly be possible to work hard and achieve incredible success. But for a poor black woman, the American dream is mostly a myth.

Case Study: Conflict Theory and Culture

Conflict Theorists (and some functionalists) argue that there are two types of culture: ideal and real. The ideal culture is the culture that society strives toward – it’s the standard that maintains a goal of society. This is contrasted to real culture , which sociologist Max Weber says is the real-life manifestation of culture. This includes the elements of oppression and inequalities, which ideal culture does not consider. For example, if ideal culture talks about democracy, real culture points out how politics is biased toward privileged people.

3. Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism focuses on face-to-face interactions of individuals and sees culture as an outcome of these.

Such sociologists believe that human interactions are a continuous process of finding meaning from the actions of others and the objects in the environment (Little). All these actions & objects have a “symbolic meaning”.

Culture is how this symbolic meaning is shared and interpreted. Symbolic interactions also believe that our social world is quite dynamic: instead of obsessing over rigid structures, they emphasize how situations and meanings are constantly changing.

For a symbolic interactionist, something as simple as a t-shirt communicates a symbolic meaning. They would argue that clothes do not simply play a “functional” role (protection) but also express something about the wearer.

See Also: Examples of Symbolic Interactionism

Culture includes the values, practices, and artifacts of a group of people; it is our shared “way of life”.

Most human behavior —from what we eat at breakfast to when we go back to sleep—is socially acquired through culture. It gives us a shared sense of “meaning” and guides human behavior, helping to maintain a stable society. However, it is also entrenched in power relations and can both enforce/challenge those relations.

Little, William. (2016). Introduction to Sociology – 1st Canadian Edition . OpenEd.

Murdock, George P. (1949). Social Structure . Macmillan.

Scott, Taylor. (2014). A Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford.

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art, and custom. J. Murray.

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Indirect Democracy: Definition and Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Pluralism (Sociology): Definition and Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Equality Examples

- Sourabh Yadav (MA) #molongui-disabled-link Instrumental Learning: Definition and Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

3.4 Theoretical Perspectives on Culture

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section you should be able to:

- Discuss the major theoretical approaches to cultural interpretation

Music, fashion, technology, and values—all are products of culture. But what do they mean? How do sociologists perceive and interpret culture based on these material and nonmaterial items? Let’s finish our analysis of culture by reviewing them in the context of three theoretical perspectives: functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.

Functionalists view society as a system in which all parts work—or function—together to create society as a whole. They often use the human body as an analogy. Looking at life in this way, societies need culture to exist . Cultural norms function to support the fluid operation of society, and cultural values guide people in making choices. Just as members of a society work together to fulfill a society’s needs, culture exists to meet its members’ social and personal needs.

Functionalists also study culture in terms of values. For example, education is highly valued in the U.S. The culture of education—including material culture such as classrooms, textbooks, libraries, educational technology, dormitories and non-material culture such as specific teaching approaches—demonstrates how much emphasis is placed on the value of educating a society’s members. In contrast, if education consisted of only providing guidelines and some study material without the other elements, that would demonstrate that the culture places a lower value on education.

Functionalists view the different categories of culture as serving many functions. Having membership in a culture, a subculture, or a counterculture brings camaraderie and social cohesion and benefits the larger society by providing places for people who share similar ideas.

Conflict theorists, however, view social structure as inherently unequal, based on power differentials related to issues like class, gender, race, and age. For a conflict theorist, established educational methods are seen as reinforcing the dominant societal culture and issues of privilege. The historical experiences of certain groups— those based upon race, sex, or class, for instance, or those that portray a negative narrative about the dominant culture—are excluded from history books. For a long time, U.S. History education omitted the assaults on Native American people and society that were part of the colonization of the land that became the United States. A more recent example is the recognition of historical events like race riots and racially based massacres like the Tulsa Massacre, which was widely reported when it occurred in 1921 but was omitted from many national historical accounts of that period of time. When an episode of HBO’s Watchmen showcased the event in stunning and horrific detail, many people expressed surprise that it had occurred and it hadn’t been taught or discussed (Ware 2019).

Historical omission is not restricted to the U.S. North Korean students learn of their benevolent leader without information about his mistreatment of large portions of the population. According to defectors and North Korea experts, while famines and dire economic conditions are obvious, state media and educational agencies work to ensure that North Koreans do not understand how different their country is from others (Jacobs 2019).

Inequities exist within a culture’s value system and become embedded in laws, policies, and procedures. This inclusion leads to the oppression of the powerless by the powerful. A society’s cultural norms benefit some people but hurt others. Women were not allowed to vote in the U.S. until 1920, making it hard for them to get laws passed that protected their rights in the home and in the workplace. Same-sex couples were denied the right to marry in the U.S. until 2015. Elsewhere around the world, same-sex marriage is only legal in 31 of the planet’s 195 countries.

At the core of conflict theory is the effect of economic production and materialism. Dependence on technology in rich nations versus a lack of technology and education in poor nations. Conflict theorists believe that a society’s system of material production has an effect on the rest of culture. People who have less power also have fewer opportunities to adapt to cultural change. This view contrasts with the perspective of functionalism. Where functionalists would see the purpose of culture—traditions, folkways, values—as helping individuals navigate through life and societies run smoothly, conflict theorists examine socio-cultural struggles, including the power and privilege created for some by using and reinforcing a dominant culture that sustains their position in society.