The Importance of Cultural Context: Expanding Interpretive Power in Psychological Science

In 1995, psychological scientists Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley made a splash with their influential book Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children , in which they estimated that by age 4, poor children heard 32 million fewer words than wealthy children did. Furthermore, they argued that the number of words children hear early in life predicts later academic outcomes, potentially contributing to socioeconomic educational disparities. Interventions encouraging low-income parents to talk to their children gained traction even at the highest levels of US government. The Obama administration, for example, launched a campaign to raise awareness about the “30-million word gap.”

Twenty-three years after Hart and Risley’s book appeared, however, Douglas E. Sperry (Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College), Linda L. Sperry (Indiana State University), and Peggy J Miller (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) published analyses of five studies that called in question the existence and magnitude of a “word gap”. Using Hart and Risley’s measurement of words spoken to a child by a primary caregiver, Sperry and colleagues found inconsistent support for a word gap among a more diverse sample of wealthy and poor families.

This publication incited widespread debate. Some critiqued Sperry and colleagues’ measurement and conclusions, while others focused on the initial study’s limitations. Many suggested Hart and Risley conflated race and social class, as a majority of the poor families were Black while a majority of the wealthy families were White. Others questioned their methodology, speculating that the anxiety of being observed by educated White researchers could cause poor Black parents to speak less to their children than they normally would. Others argued Hart and Risley’s narrow focus on words spoken by a primary caregiver to a child reflected White, middle-class cultural norms. Children in other cultural contexts hear a great deal of language from other caregivers (e.g., siblings, extended family) and their ambient environments, but Hart and Risley excluded this language. Thus, in cultural contexts in which extended family plays a large role in child rearing, focusing on the primary caregiver’s language may result in an incomplete representation of the richness of a child’s linguistic environment. In fact, using more expansive measurements of words children heard at home, Sperry and colleagues found that children in some lower-income communities heard more words than wealthy children did.

While psychological scientists surely have something to learn from both iterations of the “word gap” study, we have equally as much to learn from the debate itself. The criticisms raised illustrate a problem that we suggest results from a lack of interpretive power in psychological science. Interpretive power refers to the ability to understand individuals’ experiences and behaviors in relation to their cultural contexts. It requires understanding that cognition, motivation, emotion, and behavior are shaped by individuals’ cultural values and norms. The same behavior takes on different meanings in diverse cultural contexts, and different cultural contexts promote divergent normative responses to the same event.

To accurately understand human behavior, psychological scientists must understand the cultural context in which the behavior occurs and measure the behavior in culturally relevant ways. When they lack this interpretive power, they risk drawing inaccurate conclusions about psychological processes and thus building incomplete or misguided theories.

Failures of interpretive power take many forms, including:

- failing to acknowledge that culture shapes psychological processes, even if scientists do not fully understand how;

- failing to consider whether a measure or methodology captures a psychological process as it unfolds for the population studied;

- assuming findings generalize to other cultural contexts unless otherwise demonstrated; and

- not understanding how researchers’ own cultural experiences shape their assumptions, decisions, and conclusions.

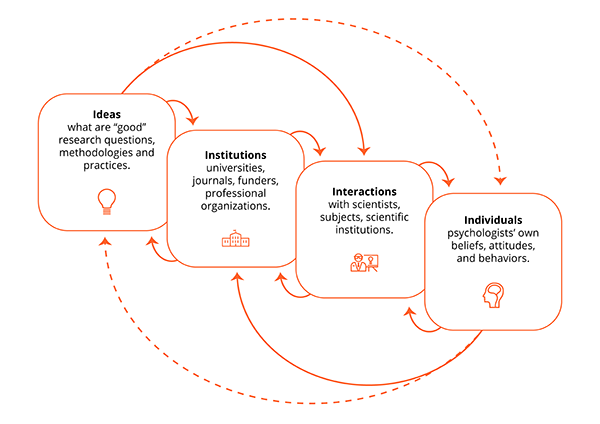

To build stronger theories, psychological scientists can leverage interpretive power. The burden rests not just on individual researchers, but on the field as a whole to implement practices that attend to cultural influences. Using the culture cycle framework, we describe changes at four key levels of psychological science — ideas, institutions, interactions, and individuals — that can help the field build interpretive power

Figure: The Culture Cycle Framework (adapted from Markus & Conner, 2013)

Developing Culture-Conscious Research Questions

One of the key problems underlying psychology’s lack of interpretive power is the fact that a majority of research is conducted by people from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic) contexts and relies on WEIRD samples. Developing interpretive power involves recognizing that many psychological theories describe human behavior in these particular cultural contexts, and that we know less about processes in non-WEIRD contexts. We must embrace the idea that culture shapes human experiences and reject the notion that any one group or context represents “normative” human functioning.

Scientific institutions (e.g., journals, universities, professional organizations) can play a powerful role in promoting attention to culture. For example, journals can showcase research with non-WEIRD samples to communicate the possibilities and importance of conducting research with diverse populations. Journals can also encourage greater transparency regarding studies’ cultural limitations by requiring researchers to specify the cultural contexts from which they recruited subjects and to which they expect findings to generalize. Critically, generalizability should not determine whether research is published. Studies that include small, difficult to recruit, or culturally specific samples should be considered potentially informative so long as they use sound methodologies.

Given that research with non-WEIRD populations is often more expensive and time consuming than research with WEIRD samples, institutions also have a responsibility to support and incentivize non-WEIRD research. Universities can account for the time, expense, and potential impact of non-WEIRD research when making tenure decisions, and professional organizations can create competitive awards to support this work. Perhaps most critically, universities can recruit psychological scientists from diverse backgrounds to join and lead departments.

Cross-cultural interactions also provide an avenue for increasing interpretive power. Both psychological institutions and individual scientists can build trusting, mutually beneficial relationships with diverse communities, many of which the field has historically mistreated, misunderstood, or ignored. In building these relationships, psychological scientists can work to reserve judgment and design research to address the communities’ concerns and needs.

On an individual level, building interpretive power requires exposure to different cultures and perspectives. Seeking diverse collaborators can render more nuanced and informed research questions. APS William James Fellow Hazel Markus and APS Fellow Shinobu Kitayama, for example, generated their influential theory of cultural models of self by comparing their own cultural experiences. Psychological scientists can also engage with the theoretical frameworks and knowledge about non-WEIRD cultures that are abundant in other academic disciplines (e.g., sociology, history, anthropology) to generate more culturally-informed research questions.

Using Culture-Conscious Research Design

In psychological science, hypothesis testing is the gold standard, yet many of our research designs are developed by and tested among people from WEIRD cultural contexts. Furthermore, a priori hypotheses often stem from researchers’ own experiences and thus often regard WEIRD processes. Embracing hypothesis generating methodologies can reduce WEIRD bias in research design. Ethnographic observations, focus groups, case studies, content analyses, and archival analyses all provide means of gaining insight about non-WEIRD cultural contexts that can inspire further experimental work. Leveraging interpretive power in research design means placing greater value on such methodologies.

To a great extent, scientific institutions serve as gatekeepers of “high-quality” research design. Journals, for instance, dictate which methodologies are acceptable for publication, with the most prestigious journals valuing — or even requiring —hypothesis testing. Because WEIRD samples are often most feasible for these designs, non-WEIRD populations and processes remain underrepresented in high-impact journals. To build interpretive power, journals can make space for a wider range of methodologies. They can recognize that, given the dearth of non-WEIRD research, exploratory work is often most helpful in advancing understanding of these cultural contexts. Journals can also make space for non-WEIRD findings that diverge from previous research with WEIRD populations. These findings can be considered not as “failures to replicate”, but as information about how psychological processes might differ cross-culturally.

Interactions with experts inside and outside of the field can also expand psychological scientists’ methodological repertoires and lead to more culture-conscious research design. Disciplines that use information-rich methodologies provide examples of how to thoroughly document qualitative and quantitative non-experimental findings. By drawing inspiration from research that probes different levels of society and uses diverse means of gathering and integrating data, we will find more generative methodologies to build interpretive power in our own field.

Finally, just as psychological scientists conduct a priori statistical power analyses, they can also conduct a priori interpretive power analyses. They can examine whether their methodology has been tested with non-WEIRD populations and learn about the cultural influences likely to shape the processes they study. Simultaneously, researchers can reflect on how their own cultural values and assumptions shape their empirical approach. Many fields encourage positionality statements, wherein researchers describe their own experiences in relation to their subject. This practice can help psychological scientists identify how cultural biases or misunderstandings might enter their research.

Implementing Culture-Conscious Analysis and Interpretation

Many of the statistical analyses psychological scientists use to test hypotheses treat unexplained variance as noise. Some of these variations reflect divergent cultural processes, but they are often averaged out by the majority or dismissed as outliers. Psychological researchers can commit to supplementing these analyses with practices that better illustrate variations and provide opportunities to explore potential cultural influences.

Journals can encourage psychological scientists to explore and report cultural variations. Journals can also encourage researchers to use online supplements to identify outliers and report information that may explain their variation.

Increased cross-lab communication also provides opportunities for better understanding cultural variation. Although any given dataset may include only a handful of participants from a particular culture, researchers exploring similar phenomena can pool data to create larger, more diverse samples for testing hypotheses about how and why psychological phenomena manifest differently across cultures.

Finally, psychological scientists can make a concerted effort to explore variation in their own data. Scatterplots, histograms, and spaghetti plots, for example, illustrate the diversity of effects across subjects. Rather than focusing on average effects, researchers can examine the percentage of participants for whom the hypothesized effect occurred and the percentage for which no effect or an opposite effect occurred. These small changes can elucidate cultural variation.

Stronger Theories, Better Understanding

Debates over “failed replications” such as the “30-million word gap” research can leave psychological scientists feeling anxious and unmotivated. However, they also point to the truth that our science has room for improvement, and they offer important critiques that can help our field grow. By leveraging interpretive power to understand a diversity of human experiences, psychology can build stronger theories and a more comprehensive understanding of human behavior. Perhaps more importantly, we will be better positioned to contribute our expertise to alleviate problems facing communities across the globe.

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children . Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Shankar, M. (2014, June 25). Empowering our children by bridging the word gap . Retrieved from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2014/06/25/empowering-our-children-bridging-word-gap .

Sperry, D. E., Sperry, L. L., & Miller, P. J. (2018). Reexamining the verbal environments of children from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Child Development . doi:10.1111/cdev.13072 [Epub ahead of print]

Brady, L. M., Fryberg, S. A., & Shoda, Y. (2018). Expanding the interpretive power of psychological science by attending to culture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115 (45), 11406-11413. doi:10.1073/pnas.1803526115

Rosebery A. S., Warren B., Tucker-Raymond E. (2016). Developing interpretive power in science teaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53 (10), 1571–1600. doi:10.1002/tea.21267

Markus, H. R., & Conner, A. (2013). Clash! 8 cultural conflicts that make us who we are . New York: Hudson Street Press.

Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33 (2-3), 61-83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98 (2), 224-253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Whitsett, D. D., & Shoda, Y. (2014). An approach to test for individual differences in the effects of situations without using moderator variables. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 50 , 94-104. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2013.08.008

I applaud the authors efforts but they missed step 1: make an anthropologist a part of your research team. We’ve been studying these things and theorizing them for over 100 years. There’s even a subfield of psychological anthropology!

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Authors

Laura Brady, Stephanie Fryberg, and APS Fellow Yuichi Shioda are all research scientists at the University of Washington. They can be reached by contacting [email protected] .

Complexities and Lessons in Researching Culture-Specific Experiences

Gheirat exemplifies a complex, culture-specific experience that requires using culturally sensitive research practices to investigate. Explore these case-specific ideas and solutions for researching phenomena from little-understood and/or studied phenomena.

Silver Linings in the Demographic Revolution

Podcast: In her final column as APS President, Alison Gopnik makes the case for more effectively and creatively caring for vulnerable humans at either end of life.

Communicating Psychological Science: The Lifelong Consequences of Early Language Skills

“When families are informed about the importance of conversational interaction and are provided training, they become active communicators and directly contribute to reducing the word gap (Leung et al., 2020).”

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Speaking, writing and reading are integral to everyday life, where language is the primary tool for expression and communication. Studying how people use language – what words and phrases they unconsciously choose and combine – can help us better understand ourselves and why we behave the way we do.

Linguistics scholars seek to determine what is unique and universal about the language we use, how it is acquired and the ways it changes over time. They consider language as a cultural, social and psychological phenomenon.

“Understanding why and how languages differ tells about the range of what is human,” said Dan Jurafsky , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor in Humanities and chair of the Department of Linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford . “Discovering what’s universal about languages can help us understand the core of our humanity.”

The stories below represent some of the ways linguists have investigated many aspects of language, including its semantics and syntax, phonetics and phonology, and its social, psychological and computational aspects.

Understanding stereotypes

Stanford linguists and psychologists study how language is interpreted by people. Even the slightest differences in language use can correspond with biased beliefs of the speakers, according to research.

One study showed that a relatively harmless sentence, such as “girls are as good as boys at math,” can subtly perpetuate sexist stereotypes. Because of the statement’s grammatical structure, it implies that being good at math is more common or natural for boys than girls, the researchers said.

Language can play a big role in how we and others perceive the world, and linguists work to discover what words and phrases can influence us, unknowingly.

How well-meaning statements can spread stereotypes unintentionally

New Stanford research shows that sentences that frame one gender as the standard for the other can unintentionally perpetuate biases.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

Exploring what an interruption is in conversation

Stanford doctoral candidate Katherine Hilton found that people perceive interruptions in conversation differently, and those perceptions differ depending on the listener’s own conversational style as well as gender.

Cops speak less respectfully to black community members

Professors Jennifer Eberhardt and Dan Jurafsky, along with other Stanford researchers, detected racial disparities in police officers’ speech after analyzing more than 100 hours of body camera footage from Oakland Police.

How other languages inform our own

People speak roughly 7,000 languages worldwide. Although there is a lot in common among languages, each one is unique, both in its structure and in the way it reflects the culture of the people who speak it.

Jurafsky said it’s important to study languages other than our own and how they develop over time because it can help scholars understand what lies at the foundation of humans’ unique way of communicating with one another.

“All this research can help us discover what it means to be human,” Jurafsky said.

Stanford PhD student documents indigenous language of Papua New Guinea

Fifth-year PhD student Kate Lindsey recently returned to the United States after a year of documenting an obscure language indigenous to the South Pacific nation.

Students explore Esperanto across Europe

In a research project spanning eight countries, two Stanford students search for Esperanto, a constructed language, against the backdrop of European populism.

Chris Manning: How computers are learning to understand language

A computer scientist discusses the evolution of computational linguistics and where it’s headed next.

Stanford research explores novel perspectives on the evolution of Spanish

Using digital tools and literature to explore the evolution of the Spanish language, Stanford researcher Cuauhtémoc García-García reveals a new historical perspective on linguistic changes in Latin America and Spain.

Language as a lens into behavior

Linguists analyze how certain speech patterns correspond to particular behaviors, including how language can impact people’s buying decisions or influence their social media use.

For example, in one research paper, a group of Stanford researchers examined the differences in how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online to better understand how a polarization of beliefs can occur on social media.

“We live in a very polarized time,” Jurafsky said. “Understanding what different groups of people say and why is the first step in determining how we can help bring people together.”

Analyzing the tweets of Republicans and Democrats

New research by Dora Demszky and colleagues examined how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online in an attempt to understand how polarization of beliefs occurs on social media.

Examining bilingual behavior of children at Texas preschool

A Stanford senior studied a group of bilingual children at a Spanish immersion preschool in Texas to understand how they distinguished between their two languages.

Predicting sales of online products from advertising language

Stanford linguist Dan Jurafsky and colleagues have found that products in Japan sell better if their advertising includes polite language and words that invoke cultural traditions or authority.

Language can help the elderly cope with the challenges of aging, says Stanford professor

By examining conversations of elderly Japanese women, linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto uncovers language techniques that help people move past traumatic events and regain a sense of normalcy.

Planning Effective Communications

Cultural context, culture and communication.

Culture refers to the values, beliefs, attitudes, accepted actions, and general characteristics of a group of people. We often think of culture in terms of nationality or geography, but there are cultures based on age, religion, education, ability, gender, ethnicity, income, and more. Consider cultural contexts as you plan and draft your communications. And realize that your consideration occurs through your own cultural lens.

According to Bovee and Thill:

The interaction of culture and communication is so pervasive that separating the two is virtually impossible. The way you communicate is deeply influenced by the culture in which you were raised. The meaning of words, the significance of gestures, the importance of time and place, the rules of human relationships—these and many other aspects of communication are defined by culture. To a large degree, your culture influences the way you think, which naturally affects the way you communicate both as a sender and receiver….In particular, your instinct is to encode your message using the assumptions of your culture. However, members of your audience decode your message according to the assumptions of their culture. The greater the difference between cultures, the greater the chance for misunderstanding. [1]

Although it may seem that cultural variables are too plentiful to ever master, simply being aware of cultural contexts and trying to develop fuller cultural awareness, as well as fuller self-awareness of your own assumptions and cultural lens, can help you as you analyze communication situations. The video below offers tips intended to help you communicate with more cultural awareness.

One major aspect to consider in your analysis of various national and social cultures is the concept of high-context vs. low-context cultures. High-context cultures, such as those in Asia, Greece, France, Africa, South America, or Southern India (which the narrator describes in the video above), value personal, trusting relationships. In high-context cultures, you might expect discussion of family, health, and other common topics before entering into the topic of a professional discussion. High-context cultures rely on non-verbal communications as well as verbal (e.g., there is a specific physical protocol for presenting business cards in Japan). High-context cultures also emphasize group as opposed to individual work, and members of high-context cultures are often comfortable with physical closeness in face-to-face business situations.

In contrast, low-context cultures, such as those in Northern Europe, Scandinavia, and North America, value directness and task-oriented business relationships. In low-context cultures, you might expect quick focus on the task with relatively little context-setting; the task itself provides the context. Low-context cultures rely on more on verbal communications as well as task-oriented protocol, as opposed to non-verbal communications, in order to move toward goals (e.g., minutes of last meeting, overview of agenda, discussion of agenda items in order, maintaining the time allotted to each item). Low-context cultures also emphasize individual as opposed to group work, and members of low-context cultures usually maintain their physical space in face-to-face business situations.

For an interesting discussion of becoming aware of diverse cultures, which includes examples of high- and low-context cultures, view the following video.

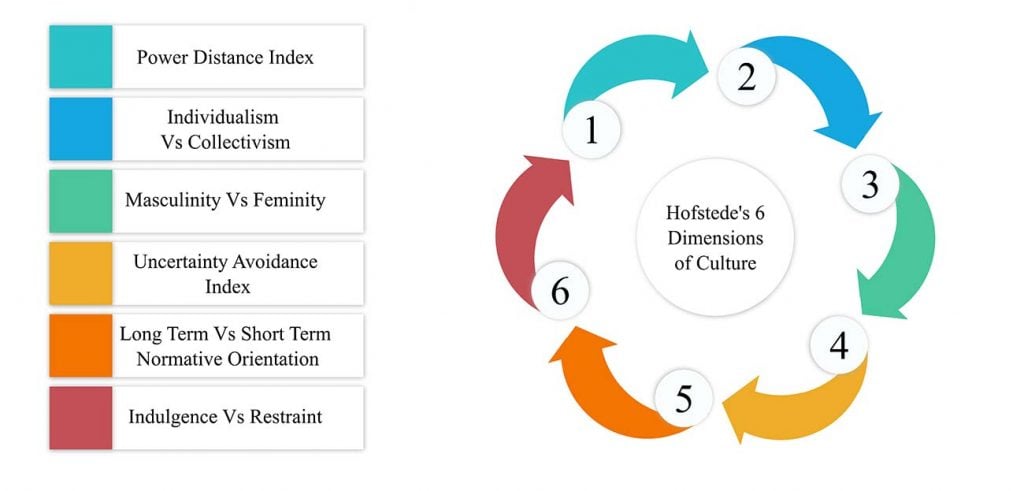

The next video offers additional ways of considering cultural context, in terms of power distance, individualism vs. collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, “masculine” and “feminine” traits, and long-term orientation.

This short video offers a few simple scenarios that deal with cultural context. Pause the video at each multiple-choice question and choose your answer before viewing the explanation.

As you can see, there are many aspects to cultural context to consider when planning professional communications. The main idea in analyzing cultural context is to try to understand the lens through which your audience experiences the communication, to strengthen the focus on creating and receiving a message respectful to the audience.

Applying an Understanding of Culture to Communications

In general, when considering cultural context, consider the following factors as you create communications:

- Amount of Detail Expected – High-context cultures such as Japan, China, and France provide little details in their writing. Since a high-context culture is based on fewer, deeper relations with people, there are many unspoken social rules and understandings within the culture. People in these cultures expect readers to have enough knowledge about the communication before they begin reading. In areas such as instructions, for example, it is assumed that readers have enough background knowledge or experience to avoid detailed explanation of every step or tool used. People in low-context cultures such as the United States, Great Britain, and Germany assume readers know very little before they begin reading. Low-context cultures have a greater number of surface-level relations; rules are more explicitly defined so others know how to behave. People in low-context cultures expect detailed writing that explains the entire process. You should consider the cultural audience for your communication so that they are not insulted by an excess or lack of information.

- Distance Between the Top and Bottom of Organizational Hierarchies – Many organizations in the United States and Western Europe have great distances with many layers between top-level management and low-level workers. When the distance is large, writing to employees above and below tends to be more formal. In cultures where companies are more flatly organized, communication between layers tends to be less formal.

- Individual versus Group Orientation – Many Asian and South American cultures are collectivist, meaning people pursue group goals and pay attention to the needs of the group. In individualistic cultures such as the United States and Northern Europe, people are more interested in personal achievement. Understanding individual vs. group orientation will help you know whether to emphasize “we” or “you/I” in your communications.

- In-person Business Communications – There are several differences that one should be aware of when meeting a colleague with a different cultural background. For instance, some cultures stand very close to each other when talking and some prefer to have distance. Some cultures make eye contact with each other and some find it disrespectful. There are also certain cultures where an employee will not disagree or give feedback to their superior. It is seen as disrespectful. In these cultures, it is usually unacceptable to ask questions.

- Preference for Direct or Indirect Statements – People in the United States and Northern Europe prefer direct communications, while people in Japan and Korea typically prefer indirect communications. When denying a request in the U.S., a writer will typically apologize, but firmly state that request was denied. In Japan, that directness may seem rude. A Japanese writer may instead write that the decision has not yet been made, delaying the answer with the expectation that the requester will not ask again. In Japan, this is viewed as more polite than flatly denying someone; however, in the United States this may give false hope to the requester, and the requester may ask again.

- Basis of Business Decisions – In the United States and Europe, business decisions are typically made with reference to objective points such as cost, feasibility, timeliness, etc. In Arab cultures, business decisions are often made on the basis of personal relationships. As a communicator, you should know if a goal-oriented approach is best, or if a more personable communication would be preferred.

- Interpretation of Images, Gestures, and Words – Words, images, and gestures can mean different things in different cultures. Knowing how images will be interpreted in another culture is crucial before sending documents to unfamiliar audiences. For example, hand gestures are interpreted differently around the world, and graphics showing hands should generally be avoided. Also, religiously affiliated wording can cause offense by readers. “I’ve been blessed to work with you” and comments that lend themselves to religious references should be avoided in the business setting.

Learning About Cultures

Even though it’s important to know as much about your audience as possible before starting a communication, it’s often difficult to determine cultural context: cultural biases, assumptions, and customs. To use a really simple exmaple, professionals in the U.S. write the date with the month, day, and year, but professionals in other countries write a date with the day, month, and year. Not knowing this can cause confusion. Research as many resources as feasible if you know you’ll be communicating with people from specific cultures, since understanding expectations and differences reduces the amount of miscommunication. Your audience will appreciate your knowledge of their customs.

Coworkers are also a great source of intercultural information. People familiar with you and the company provide the best information about your audience’s expectations. If coworkers have previously written to your audience, they may be able to offer insight as to how your writing will be interpreted. Previous communications kept by your company can also be a useful tool for determining how to write to another culture.

Note that there are countless resources dealing with cultural context and communication, from the Peace Corp’s Culture Matters Workbook , to websites such as Syracuse University’s Disability Cultural Center’s Language Guide , to various websites on specific cultures. Research your audience as much as time allows to learn more about their cultural contexts.

- Read a sample letter based on an actual letter sent to a director of an online college program from an organization in Indonesia. What can you determine about the author of the letter? What is the author’s purpose? What parts of the letter help you understand the author’s purpose? Consider how the author’s style of communication is like or unlike business letters that you are familiar with. What specific similarities and/or differences do you observe?

- Then do some brief research on Indonesian culture. If you search the Internet for “doing business in Indonesian culture,” you’ll find multiple short articles. Read one. What are some main characteristics of doing business in this culture that you see exemplified in this letter?

- What specific characteristics of Indonesian culture do you need to know in order to respond appropriately, with this particular cultural context in mind?

- If you were to respond, compose one specific sentence or strategy that you might take, given what you learned from the sample letter and your brief research.

Analyzing Your Own Cultural Lens

In addition to considering characteristics of cultures other than your own, realize that people receive information and make meaning through their own cultural lenses. Your cultural lens is the set of values, expectations, beliefs, actions, etc. with which you are familiar. In fact, you may be so familiar with understanding things through this lens that it’s hard to realize your own assumptions and attitudes. Think of a situation in which you were out of your usual context, e.g., celebrating a holiday with your new partner’s family for the first time, moving to a different city, or even moving from one department to another at your workplace. Experiencing a new situation may have made you more aware of some of your own values, attitudes, and beliefs. When analyzing cultural context, try to develop awareness of your own cultural lens as well as characteristic values, attitudes, and beliefs of other cultures.

For example, look at the images of Indonesia included at the end of the last Try It exercise on this page. Because this text is written from the lens of western, and particularly U.S. culture, and because the purpose of the exercise was to highlight differences in culture, images were chosen that highlighted place differences between Indonesia and the U.S., playing to the cultural lens through which U.S. residents might view Indonesia (e.g., exotic pagoda architecture, hot climate and rice production). Consider how you might have reacted had you viewed these images of contemporary Indonesia at the end of the exercise.

If you’re intrigued by the concept of cultural lens, the following video offers fuller explanation of the concepts of culture, cultural lens, and organizational culture. Note that you do not need to delve this deeply into cultures when you’re doing a situational analysis as a prelude to creating a professional communication; however, the information may interest you.

[1] Bovee, Courtland and John Thill. Business Communication Today. 13th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2016, pgs. 65-66.

- Cultural Context, original material and material adapted from Technical Writing, see attribution below. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Project : Communications for Professionals. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- image of photo montage of diverse faces. Authored by : geralt. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/illustrations/photomontage-faces-photo-album-1514218/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video Cultural Diversity - Tips for Communicating with Cultural Awareness. Provided by : Speakfirst. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDvLk7e2Irc . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- video How Culture Drives Behaviours. Authored by : Julian S. Bourrelle. Provided by : TedTalks. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l-Yy6poJ2zs . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- video International Business - Cross-Cultural Communication. Authored by : Mark Walsh. Provided by : The embodiment channel. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=at7srdUiRfM&t=132s . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : YouTube video

- video Cultural Lens Overview - part I. Authored by : Laura Holyoke. Provided by : Holyoke - AOLL. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OJSIesdTcAk . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- Appreciating Different Cultures, based on WikiBooks Professional and Technical Writing at http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Professional_and_Technical_Writing/Ethics/Cultures. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/technicalwriting/chapter/appreciating-different-cultures/ . Project : Technical Writing. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- image of arm and the word Gestures. Authored by : Val Kerry. Provided by : flickr. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/fXaoJ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- image of two men from different cultures shaking hands. Authored by : Bahrain International Airport. Provided by : flickr. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/guoPub . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- image of pagoda in Indonesia. Authored by : MadebyNastia. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/pagoda-temple-lake-travel-3240169/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of rice farmer in Indonesia. Authored by : 3422763. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/farmer-rice-field-countryside-3900957/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of family on motorbike in Bali, Indonesia. Authored by : keulefm. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/bali-traffic-family-bike-transport-237205/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of beach holiday in Indonesia. Authored by : mrsvickyaltaie . Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/seminyak-bali-indonesia-holiday-2407835/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy

Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Using social media to promote social justice.

Leadership approaches imply different theoretical rationales and components that form the overall management concept. As components that need to be taken into account, Mittal and Elias (2016) consider the variables of content and context. In the first case, situations are identified in which the characteristic signs of leadership appear. The variables of context manifest when a new form of relationship among managers and subordinates arises.

As Bachrach and Mullins (2019) note, the main elements of the global mindset are the three forms of capital – intellectual, psychological, and social. The role of culture is also significant, and Mittal and Elias (2016) mention contingency variables that are included in the theory of contingency leadership. This concept includes those mechanisms that influence such indicators as diligence, productivity, and other aspects of work activity (Bachrach & Mullins, 2019). The role of culture in this theory is high since communication within a contingency approach is an essential attribute of interaction.

In order to evaluate the features of leader-subordinate relationships, it is possible to apply a special model of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. According to Thanetsunthorn and Wuthisatian (2018), these dimensions are power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism, and masculinity. Based on their study, only two components of the model can have the greatest negative effect – power distance and masculinity, “whereas individualism and uncertainty avoidance have no significant impact” (Thanetsunthorn & Wuthisatian, 2018, p. 1139).

For instance, in companies with a vertical management system, the interaction of leaders with subordinates will be less productive if masculine culture is maintained. As Thanetsunthorn and Wuthisatian (2018) remark, uncertainty avoidance is a more useful strategy to communicate effectively. Therefore, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are to be taken into account when discussing the features of leader-subordinate relationships.

The role of social media is significant in addressing the issues of inequality and promoting justice. One of the examples of activities aimed at drawing attention to such problems is the annual organization of a special event dedicated to the struggle for social justice in Canada – Media Democracy Day (MDD). According to Skinner, Hackett, and Poyntz (2015), students from local universities are the most active participants in this event. In the focus of the members of volunteer groups, media-related problems are raised, in particular, racial prejudices and the lack of appropriate support for minorities that are under pressure in social networks.

Another example of such targeted work is the activity conducted by students and having specific ideological overtones. Baker-Bell, Stanbrough, and Everett (2017) note that the involvement of a large number of stakeholders in the dissemination of important information on the need for equality is one of such initiatives. This approach is implemented through social networks successfully enough, and the members of a large community “produce counternarratives, express their opinions, voice their concerns, and locate more reliable news and information about the Black community” (Baker-Bell et al., 2017, p. 137).

This principle of interaction allows students to draw as much attention as possible to the issue under consideration and find ways of conveying their position to the public. In general, social media promotes student activism because this group of the population forms the prevailing number of Internet users, and it is easier for them to discuss particular problems in this environment.

With regard to the areas of management and business, this position may be used as one of the samples of career guidance. The leaders of individual organizations can use the principle of disseminating information to the target audience, in particular, subordinates through the modern forms of communication. Business approaches may also imply using online platforms actively for advertising and selling products, which makes the field of social media relevant and meaningful.

Bachrach, D. G., & Mullins, R. (2019). A dual-process contingency model of leadership, transactive memory systems and team performance. Journal of Business Research , 96 , 297-308. Web.

Baker-Bell, A., Stanbrough, R. J., & Everett, S. (2017). The stories they tell: Mainstream media, pedagogies of healing, and critical media literacy. English Education , 49 (2), 130-152.

Mittal, R., & Elias, S. M. (2016). Social power and leadership in cross-cultural context. Journal of Management Development , 35 (1), 58-74. Web.

Skinner, D., Hackett, R., & Poyntz, S. R. (2015). Media activism and the academy, three cases: Media Democracy Day, open media, and NewsWatch Canada. Studies in Social Justice , 9 (1), 86-101. Web.

Thanetsunthorn, N., & Wuthisatian, R. (2018). Cultural configuration models: Corporate social responsibility and national culture. Management Research Review , 41 (10), 1137-1175. Web.

- In Praise of the Incomplete Leader and Ways Women Lead

- Transactional Leadership Style at a Hospital

- Laban Erapu's Views on Naipaul's "Miguel Street"

- Vietnam War in the "Platoon" Movie by Oliver Stone

- Quote from The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Campbell

- Service Leadership Style in Chinese Hotel Business

- Consolidated Products Managers' Leadership Styles

- Leadership Style and Employee Motivation: Burj Al Arab Hotel

- Self-Awareness Importance in Effective Leadership

- Establishing Authority in a Managerial Position

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, June 3). Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-power-and-leadership-in-cross-cultural-context/

"Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context." IvyPanda , 3 June 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/social-power-and-leadership-in-cross-cultural-context/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context'. 3 June.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context." June 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-power-and-leadership-in-cross-cultural-context/.

1. IvyPanda . "Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context." June 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-power-and-leadership-in-cross-cultural-context/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Social Power and Leadership in Cross-Cultural Context." June 3, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/social-power-and-leadership-in-cross-cultural-context/.

Enda's English Notes

Junior and Leaving Cert English Notes

Introduction to the Comparative Course-The Cultural Context

For Leaving Cert English, you will be asked to study three texts as part of your comparative course, under different modes of comparison. Generally, you will study a novel, a play and a film. Your job is to compare the differences and similarities in all three texts under a certain mode, for example, Cultural Context, Literary Genre, Theme or General Vision and Viewpoint.

Cultural Context:

This generally means the ‘world of the text’ in which the characters live. You will be asked to analyse how the characters are affected by the cultural context in each of the texts. A good way to think about the influence of the cultural context of a text is to imagine you can remove the main characters and place them in today’s world and if their lives would be any different. So for example, if a young girl is living in 1960’s Ireland and finds herself pregnant out of wedlock, is she influenced negatively by the cultural context? The answer would undoubtedly be yes and if you took that girl and placed her in Ireland 2020, would she face the same problems? The answer would be no, so we can clearly state that the cultural context affects this young girl negatively.

Generally, we look at cultural context under a number of headings:

- Social Class / Class structure

- The role of men and women

- Attitudes towards family

- The role of religion

- Attitudes towards love and marriage

- Customs and Rituals

- General Values

When you look at a text, you should try to identify the characters attitudes towards these headings. For example, in social class, are people treated better because they have have money and status? Do people with money look down on those who are poor? Is social status more important than happiness to the characters?

When look at the role of men and women, analyse how men and women can be treated differently based on their gender. Is the text set in a patriarchal society? Do the men have chauvinistic beliefs and are women belittled because of their gender? How easy is it for women to get what they want or is their success predicated on decisions made by men?

You should think about the attitudes towards family in the texts by asking how important Family is to the main characters? Is the happiness of their families more important than money or social status or is their family used as a means to further their social standing in the text? Some characters truly value family but in some texts you will see how little family means to the main characters.

Do the characters in your text marry for love or money and security? This is a crucial question when commenting on attitudes towards love and marriage. The cultural context in some texts will dictate that people should marry for security and a chance to enhance your social standing, rather than simply for love. When you are analysing your text, it is always a good idea to think about how different today’s world is or in some cases, how things haven’t changed.

Share this:

One thought on “ introduction to the comparative course-the cultural context ”.

- Pingback: Introduction to the Comparative Course – Enda's English Notes

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory & Examples

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

- Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory, developed by Geert Hofstede, is a framework used to understand the differences in culture across countries.

- Hofstede’s initial six key dimensions include power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity, and short vs. long-term orientation. Later, researchers added restraint vs. indulgence to this list.

- The extent to which individual countries share key dimensions depends on a number of factors, such as shared language and geographical location.

- Hofstede’s cultural dimensions are widely used to understand etiquette and facilitate communication across cultures in areas ranging from business to diplomacy.

History and Overview

Hofstede’s cultural values or dimensions provide a framework through which sociologists can describe the effects of culture on the values of its members and how these values relate to the behavior of people who live within a culture.

Outside of sociology, Hofstede’s work is also applicable to fields such as cross-cultural psychology, international management, and cross-cultural communication.

The Dutch management researcher Geert Hofstede created the cultural dimensions theory in 1980 (Hofstede, 1980).

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions originate from a large survey that he conducted from the 1960s to 1970s that examined value differences among different divisions of IBM, a multinational computer manufacturing company.

This study encompassed over 100,000 employees from 50 countries across three regions. Hoftstede, using a specific statistical method called factor analysis, initially identified four value dimensions: individualism and collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity and femininity.

Later research from Chinese sociologists identified a fifty-dimension, long-term, or short-term orientation (Bond, 1991).

Finally, a replication of Hofstede’s study, conducted across 93 separate countries, confirmed the existence of the five dimensions and identified a sixth known as indulgence and restraint (Hofstede & Minkov, 2010).

Cultural Dimensions

Geert Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory (1980) examined people’s values in the workplace and created differentiation along three dimensions: small/large power distance, strong/weak uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and individualism/collectivism.

Power-Distance Index

The power distance index describes the extent to which the less powerful members of an organization or institution — such as a family — accept and expect that power is distributed unequally.

Although there is a certain degree of inequality in all societies, Hofstede notes that there is relatively more equality in some societies than in others.

Individuals in societies that have a high degree of power distance accept hierarchies where everyone has a place in a ranking without the need for justification.

Meanwhile, societies with low power distance seek to have an equal distribution of power. The implication of this is that cultures endorse and expect relations that are more consultative, democratic, or egalitarian.

In countries with low power distance index values, there tends to be more equality between parents and children, with parents more likely to accept it if children argue or “talk back” to authority.

In low power distance index workplaces, employers and managers are more likely to ask employees for input; in fact, those at the lower ends of the hierarchy expect to be asked for their input (Hofstede, 1980).

Meanwhile, in countries with high power distance, parents may expect children to obey without questioning their authority. Those of higher status may also regularly experience obvious displays of subordination and respect from subordinates.

Superiors and subordinates are unlikely to see each other as equals in the workplace, and employees assume that higher-ups will make decisions without asking them for input.

These major differences in how institutions operate make status more important in high power distance countries than low power distance ones (Hofstede, 1980).

Collectivism vs. Individualism

Individualism and collectivism, respectively, refer to the integration of individuals into groups.

Individualistic societies stress achievement and individual rights, focusing on the needs of oneself and one’s immediate family.

A person’s self-image in this category is defined as “I.”

In contrast, collectivist societies place greater importance on the goals and well-being of the group, with a person’s self-image in this category being more similar to a “We.”

Those from collectivist cultures tend to emphasize relationships and loyalty more than those from individualistic cultures.

They tend to belong to fewer groups but are defined more by their membership in them. Lastly, communication tends to be more direct in individualistic societies but more indirect in collectivistic ones (Hofstede, 1980).

Uncertainty Avoidance Index

The uncertainty avoidance dimension of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions addresses a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity.

This dimension reflects the extent to which members of a society attempt to cope with their anxiety by minimizing uncertainty. In its most simplified form, uncertainty avoidance refers to how threatening change is to a culture (Hofstede, 1980).

A high uncertainty avoidance index indicates a low tolerance for uncertainty, ambiguity, and risk-taking. Both the institutions and individuals within these societies seek to minimize the unknown through strict rules, regulations, and so forth.

People within these cultures also tend to be more emotional.

In contrast, those in low uncertainty avoidance cultures accept and feel comfortable in unstructured situations or changeable environments and try to have as few rules as possible. This means that people within these cultures tend to be more tolerant of change.

The unknown is more openly accepted, and less strict rules and regulations may ensue.

For example, a student may be more accepting of a teacher saying they do not know the answer to a question in a low uncertainty avoidance culture than in a high uncertainty avoidance one (Hofstede, 1980).

Femininity vs. Masculinity

Femininity vs. masculinity, also known as gender role differentiation, is yet another one of Hofstede’s six dimensions of national culture. This dimension looks at how much a society values traditional masculine and feminine roles.

A masculine society values assertiveness, courage, strength, and competition; a feminine society values cooperation, nurturing, and quality of life (Hofstede, 1980).

A high femininity score indicates that traditionally feminine gender roles are more important in that society; a low femininity score indicates that those roles are less important.

For example, a country with a high femininity score is likely to have better maternity leave policies and more affordable child care.

Meanwhile, a country with a low femininity score is likely to have more women in leadership positions and higher rates of female entrepreneurship (Hofstede, 1980).

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Orientation

The long-term and short-term orientation dimension refers to the degree to which cultures encourage delaying gratification or the material, social, and emotional needs of their members (Hofstede, 1980).

Societies with long-term orientations tend to focus on the future in a way that delays short-term success in favor of success in the long term.

These societies emphasize traits such as persistence, perseverance, thrift, saving, long-term growth, and the capacity for adaptation.

Short-term orientation in a society, in contrast, indicates a focus on the near future, involves delivering short-term success or gratification, and places a stronger emphasis on the present than the future.

The end result of this is an emphasis on quick results and respect for tradition. The values of a short-term society are related to the past and the present and can result in unrestrained spending, often in response to social or ecological pressure (Hofstede, 1980).

Restraint vs. Indulgence

Finally, the restraint and indulgence dimension considers the extent and tendency of a society to fulfill its desires.

That is to say, this dimension is a measure of societal impulse and desire control. High levels of indulgence indicate that society allows relatively free gratification and high levels of bon de vivre.

Meanwhile, restraint indicates that society tends to suppress the gratification of needs and regulate them through social norms.

For example, in a highly indulgent society, people may tend to spend more money on luxuries and enjoy more freedom when it comes to leisure time activities. In a restrained society, people are more likely to save money and focus on practical needs (Hofstede, 2011).

Correlations With Other Country’s Differences

Hofstede’s dimensions have been found to correlate with a variety of other country difference variables, including:

- geographical proximity,

- shared language,

- related historical background,

- similar religious beliefs and practices,

- common philosophical influences,

- and identical political systems (Hofstede, 2011).

For example, countries that share a border tend to have more similarities in culture than those that are further apart.

This is because people who live close to each other are more likely to interact with each other on a regular basis, which leads to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures.

Similarly, countries that share a common language tend to have more similarities in culture than those that do not.

Those who speak the same language can communicate more easily with each other, which leads to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures (Hofstede, 2011).

Finally, countries that have similar historical backgrounds tend to have more similarities in culture than those that do not.

People who share a common history are more likely to have similar values and beliefs, which leads, it has generally been theorized, to a greater understanding and appreciation of each other’s cultures.

Applications

Cultural difference awareness.

Geert Hofstede shed light on how cultural differences are still significant today in a world that is becoming more and more diverse.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can be used to help explain why certain behaviors are more or less common in different cultures.

For example, individualism vs. collectivism can help explain why some cultures place more emphasis on personal achievement than others. Masculinity vs. feminism could help explain why some cultures are more competitive than others.

And long-term vs. short-term orientation can help explain why some cultures focus more on the future than the present (Hofstede, 2011).

International communication and negotiation

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can also be used to predict how people from different cultures will interact with each other.

For example, if two people from cultures with high levels of power distance meet, they may have difficulty communicating because they have different expectations about who should be in charge (Hofstede, 2011).

In Business

Finally, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions can be used to help businesses adapt their products and marketing to different cultures.

For example, if a company wants to sell its products in a country with a high collectivism score, it may need to design its packaging and advertising to appeal to groups rather than individuals.

Within a business, Hofstede’s framework can also help managers to understand why their employees behave the way they do.

For example, if a manager is having difficulty getting her employees to work together as a team, she may need to take into account that her employees come from cultures with different levels of collectivism (Hofstede, 2011).

Although the cultural value dimensions identified by Hofstede and others are useful ways to think about culture and study cultural psychology, the theory has been chronically questioned and critiqued.

Most of this criticism has been directed at the methodology of Hofstede’s original study.

Orr and Hauser (2008) note Hofstede’s questionnaire was not originally designed to measure culture but workplace satisfaction. Indeed, many of the conclusions are based on a small number of responses.

Although Hofstede administered 117,000 questionnaires, he used the results from 40 countries, only six of which had more than 1000 respondents.

This has led critics to question the representativeness of the original sample.

Furthermore, Hofstede conducted this study using the employees of a multinational corporation, who — especially when the study was conducted in the 1960s and 1970s — were overwhelmingly highly educated, mostly male, and performed so-called “white collar” work (McSweeney, 2002).

Hofstede’s theory has also been criticized for promoting a static view of culture that does not respond to the influences or changes of other cultures.

For example, as Hamden-Turner and Trompenaars (1997) have envisioned, the cultural influence of Western powers such as the United States has likely influenced a tide of individualism in the notoriously collectivist Japanese culture.

Nonetheless, Hofstede’s theory still has a few enduring strengths. As McSweeney (2002) notes, Hofstede’s work has “stimulated a great deal of cross-cultural research and provided a useful framework for the comparative study of cultures” (p. 83).

Additionally, as Orr and Hauser (2008) point out, Hofstede’s dimensions have been found to be correlated with actual behavior in cross-cultural studies, suggesting that it does hold some validity.

All in all, as McSweeney (2002) points out, Hofstede’s theory is a useful starting point for cultural analysis, but there have been many additional and more methodologically rigorous advances made in the last several decades.

Bond, M. H. (1991). Beyond the Chinese face: Insights from psychology . Oxford University Press, USA.

Hampden-Turner, C., & Trompenaars, F. (1997). Response to geert hofstede. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21 (1), 149.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International studies of management & organization, 10 (4), 15-41.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online readings in psychology and culture, 2 (1), 2307-0919.

Hofstede, G., & Minkov, M. (2010). Long-versus short-term orientation: new perspectives. Asia Pacific Business Review, 16(4), 493-504.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences (Vol. Sage): Beverly Hills, CA.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the mind . London, England: McGraw-Hill.

McSweeney, B. (2002). The essentials of scholarship: A reply to Geert Hofstede. Human Relations, 55( 11), 1363-1372.

Orr, L. M., & Hauser, W. J. (2008). A re-inquiry of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: A call for 21st century cross-cultural research. Marketing Management Journal, 18 (2), 1-19.

Further Information

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological review, 98(2), 224.

- Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychological review, 96(3), 506.

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological bulletin, 128(1), 3.

- Brewer, M. B., & Chen, Y. R. (2007). Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychological review, 114(1), 133.

- Grossmann, I., & Santos, H. (2017). Individualistic culture.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

24 What Is New Historicism? What Is Cultural Studies?

When we use New Historicism or cultural studies as our lens, we seek to understand literature and culture by examining the historical and cultural contexts in which literary works were produced and by exploring the ways in which literature and culture influence and are influenced by social and political power dynamics. For our exploration of these critical methods, we will consider the literary work’s context as the center of our target.

New Historicism is often associated with the work of Stephen Greenblatt , who argued that literature is not a timeless reflection of universal truths, but rather a product of the historical and cultural contexts in which it was produced. Greenblatt emphasized the importance of studying the social, political, and economic factors that shaped literary works, as well as the ways in which those works in turn influenced the culture and politics of their time.

New Historicism also seeks to break down the boundaries between high and low culture, and to explore the ways in which literature and culture interact with other forms of discourse and representation, such as science, philosophy, and popular culture.

One of the key principles of New Historicism is the idea that literature and culture are never neutral or objective, but are always implicated in power relations and struggles. It also emphasizes the importance of the reader or interpreter in shaping the meaning of a text, arguing that our own historical and cultural contexts influence the way we understand and interpret literary works. When using this method, we often talk about cultural artifacts as part of the discourse of their time period.

New Historicism has been influential in a variety of fields, including literary and cultural studies, history, and anthropology. It has been used to analyze a wide range of literary works, from Shakespeare to contemporary novels, as well as other cultural artifacts such as films and popular music.

Cultural studies is an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing literature that emerged in the late 20th century. Unlike traditional literary criticism that focuses solely on the text itself, cultural studies criticism explores the relationship between literature and culture. It considers how literature reflects, influences, and is influenced by the broader cultural, social, political, and historical contexts in which it is produced and consumed.

In cultural studies literary criticism, scholars may examine how literature intersects with issues such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and power dynamics. The goal is to understand how literature participates in and shapes cultural discourses. This approach emphasizes the importance of considering the cultural and social implications of literary texts, as well as the ways in which literature can be a site of contestation and negotiation.

Key concepts in cultural studies literary criticism include hegemony, representation, identity, and the politics of culture. Scholars in this field often draw on a variety of theoretical perspectives, including postcolonial theory, feminist theory, queer theory, and critical race theory, to analyze and interpret literary works in their cultural context. We will explore these approaches to literature in more depth in future parts of the book.

Learning Objectives

- Understand how formal elements in literary texts create meaning within the context of culture and literary discourse. (CLO 2.1

- Using a literary theory, choose appropriate elements of literature (formal, content, or context) to focus on in support of an interpretation (CLO 2.3)

- Emphasize what the work does and how it does it with respect to form, content, and context (CLO 2.4

- Understand how context impacts the reading of a text, and how different contexts can bring about different readings (CLO 4.1)

- Demonstrate through discussion and/or writing how textual interpretation can change given the context from which one reads (CLO 6.2)

- Understand that interpretation is inherently political, and that it reveals assumptions and expectations about value, truth, and the human experience (CLO 7.1)

Scholarship: An Excerpt from the Introduction to Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969)

Michel Foucault, the French philosopher and historian, is widely credited with the ideas about history that led to the development of New Historicism as an approach to literary texts. In this passage, Foucault explains his aims in proposing that history does not consist of stable facts. Understanding Foucault’s approach to history is necessary for understanding the New Historicism critical approach to literature.