Jae DiBello Takeuchi Research & Teaching Projects

- Sep 26, 2023

How to write a 300-word conference presentation abstract

Updated: Nov 8, 2023

I recently participated in a workshop for graduate students preparing abstract proposals for

the 2024 ICJLE (International Conference on Japanese Language Education) conference . During the workshop, I shared some tips that I use when I write abstracts, so I thought it might be helpful to post them here. Note that I’m assuming you have already settled on the topic and the project is underway. If that’s not the case… well, that’s a topic for another blog.

Don’t start by planning to write 300 words. Your goal should not be “write 300 words.” If it is, and you stop at 300 words, or hastily wrap up when you get to that length, you may stop before you’ve included all the necessary elements. Or worse, you may stop writing before you’ve articulated your presentation’s conclusions or contributions.

Although it’s common to think about writing in terms of length, it’s important to ensure that you write through all your key ideas. Have you ever heard the expression “writing is thinking”? This is the idea that writing is not figuring out everything we’re going to say in our heads, and then writing down a bunch of fully formed thoughts. Instead, it is in the act of writing that we figure out what it is we want to say. As Steven Mintz observed, “writing is not simply a matter of expressing pre-existing thoughts clearly. It’s the process through which ideas are produced and refined.”

In drafting your abstract, use the act of writing to articulate and refine your ideas. Write an outline . A good place to start is with a basic outline, which might include: introduction and background, description of the study, preliminary findings, conclusion, and contributions. Now, instead of writing 300 words, your goal becomes writing a few sentences or a short paragraph for each section in the outline.

If you find that you can’t write at least a sentence or two for each section, that means you still have some work to do before you’ll be ready to write the abstract. Maybe you need to do a little more work on previous research literature before you can write the background or contributions. Or perhaps you need to revisit your analysis before you can articulate the preliminary findings. Writing through the outline will help you find these missing pieces.

After you finish writing through each section of the outline, you will have a rough draft of your abstract. Maybe it’s 400 words, or maybe closer to 500 words, that’s ok. This step will help you complete the crucial task of articulating your ideas.

Revisit the evaluation criteria . Before you start editing, take some time to think about how your abstract will be evaluated. Return to the Call for Proposals and see if the evaluation criteria are specified. If so, evaluate your abstract based on that. Read as if you were a reviewer and see how well your draft aligns with the criteria. If the criteria are not listed in the CfP, re-read the conference description, and use this information to review your draft description. It’s safe to assume that abstracts will be evaluated based on how clearly they explain the topic, background, study details (data, methodology), conclusions or findings, and contributions. If this list looks a lot like the outline you wrote in the step above, you’re doing it right!

As you read your draft, ask yourself which sections are unclear, for example, from the perspective of someone who hasn’t read the same research articles you’ve read. Maybe you need to add some definitional information, or there are details missing from the description of your study. As you read, ask yourself “so what? Why does this matter?” If the answer isn’t clear from the information you’ve provided, you need to address that. As you go through this process, you may find you’re adding more to address these missing pieces. Again, that’s ok. Right now, you want to make sure your abstract has all the details it needs to have.

Edit and Cut. Now it’s time to start looking at that word count! If you have 400 words or less, careful editing should easily get you down closer to 300. But if you have 500 words or more, you are going to need to remove entire sentences or whole sections. First, look for redundancy. You may be surprised to find that you’re saying the same thing twice in two different sections – for example, in the introduction and the conclusion. In a 150-page book, repeating something from the introduction when you write the conclusion is ok, since the reader may have forgotten some early details by the time they get to the end. But such repetition isn’t necessary in a 300-word abstract. So identify spots where you are repeating yourself, and start your cutting there.

Next, look for details that aren’t needed for the abstract, and keep only those that are necessary to help the reader understand your project and where it fits in your field. For example, do you have a lot of information in the background section? A lot of literature review details and multiple citations? That’s a good place to start cutting or collapsing. Do you have more details about the study than are needed in an abstract? Cut that, too.

Another detail to pay attention to at this stage is the structure and order in which you introduce ideas. Experiment with moving sentences around to see if there’s a more effective way to present your topic. Check to see if something you have in the conclusion section might actually work better in the introduction section.

While you’re doing all this cutting, be sure to keep earlier drafts and save any of the language you’re cutting. You may find it useful later, for your presentation or an article write-up.

At this point, if you’re still struggling to get the word count down, move on to the next step!

Put it aside before editing again . This step is essential, so be sure to give yourself enough time before the submission deadline. Put your abstract aside and work on something else. You can work on the project or the presentation, but don’t work on the abstract. Come back to it, in a few days or, ideally, in a week. After some time away, return to your abstract and re-read it with fresh eyes. Focus on clarity, structure, and coherence. If it was still too long when you set it aside, this break should help you spot more places to cut.

Polish and submit . At this point, you should have a more refined and concise presentation of your ideas than when you started. If you have time to get feedback from a friend or mentor, great! But if not, the steps I’ve outlined here will have helped you come up with a solid abstract that demonstrates to the reader what your project is and how it will contribute to the conference.

Now submit your abstract and get started on prepping the actual presentation!

- Publications & Writing

Recent Posts

Introducing my book on Native Speaker Bias in Japan

- Search Events

- Subscription

Login/Register

How to Write an Abstract for a Conference: The Ultimate Guide

Are you thinking about attending a conference? If so, you will likely be asked to submit an abstract beforehand. An abstract is an ultra-brief summary of your proposed presentation; it should be no longer than 300 words and contain just the key points of your speech. A conference abstract is also known as a registration prospectus, an information document or a proposal. It is effectively a pitch document that explains why your speech would be of value to the audience at that particular conference – and why they need to hear it from you rather than anyone else! Creating an effective abstract is not always easy, and if this is the first time you have been asked to write one it can feel like quite a challenge. However, don’t panic! This blog post covers everything you need to know about how to write an abstract for a conference – read on to get started now!

What Exactly is an Abstract?

As we have already mentioned, an abstract is a super-brief summary of your proposed presentation. An abstract is used in several different fields and industries, but it’s most often found in the worlds of research, academia and business. An abstract allows the reader to get a quick overview of the main points of a longer document, such as a research paper, a dissertation or a business plan. It’s therefore a useful tool for helping people to get up to speed with your work quickly. Abstracts are also used to summarize conference presentations. A conference abstract is effectively a pitch document that explains why your speech would be of value to the audience at that particular conference – and why they need to hear it from you rather than anyone else!

Why is an abstract important?

Conference organizers need to be able to effectively communicate what the event is about, who should attend and what each speaker will be talking about. This can often be challenging when there are hundreds of different speakers and presentations on a wide range of topics. By creating an abstract, you’re helping the event organizers by providing them with a concise overview of your speech. This is useful because it allows the organizers to quickly and easily communicate the key points of your presentation to the rest of the conference team and conference attendees. Conference abstracts are, therefore, essential for pitching your speech to the organizer – and hopefully securing a place on the conference schedule!

How to write an effective abstract?

If you have ever read the abstracts for research papers, you’ll know that they can vary significantly in quality. Some are written in a very engaging, straightforward style that’s easy to understand, whereas others can be overly complex and difficult to comprehend. You want your abstract to be engaging and easy for your readers to understand, so we recommend keeping the following points in mind when you’re writing yours:

– Keep it brief. An abstract should be no longer than 300 words.

– Keep it relevant. An abstract is not a replacement for your actual presentation, so don’t include any information that isn’t relevant to the topic of your speech.

– Keep it accurate. Make sure that everything you include in your abstract is correct – if you get something wrong, you could have to correct it during your presentation!

– Keep it interesting. Your abstract should be engaging and exciting to read.

– Keep it professional. Even though it’s a short piece of writing, your abstract should be written professionally and engagingly.

Final words

As you can see, creating an abstract can be challenging, mainly if this is the first time you have been asked to write one. However, by following the tips and suggestions in this blog post, you should be able to create an effective, engaging and easy-to-understand abstract. With a little preparation, you should be able to create a compelling abstract that will help you get your foot on the conference speaking circuit!

Thank you liked those tips.

Good advice

Write a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Search Blog

Recent posts.

Five Academic Conference Benefits for Graduate Students

Navigating the Future of Education: Academic Conferences as a Hub for Insights, Ideas, and Best Practices

How to Prepare for a Conference: A Checklist of Tips to Make the Most of Your Experience

How a Virtual Conference Can Help You Reach Your Professional Goals

Create an Event Website: A Tutorial to Design.

Important Tips for Writing an Effective Conference Abstract

Academic conferences are an important part of graduate work. They offer researchers an opportunity to present their work and network with other researchers. So, how does a researcher get invited to present their work at an academic conference ? The first step is to write and submit an abstract of your research paper .

The purpose of a conference abstract is to summarize the main points of your paper that you will present in the academic conference. In it, you need to convince conference organizers that you have something important and valuable to add to the conference. Therefore, it needs to be focused and clear in explaining your topic and the main points of research that you will share with the audience.

The Main Points of a Conference Abstract

There are some general formulas for creating a conference abstract .

Formula : topic + title + motivation + problem statement + approach + results + conclusions = conference abstract

Here are the main points that you need to include.

The title needs to grab people’s attention. Most importantly, it needs to state your topic clearly and develop interest. This will give organizers an idea of how your paper fits the focus of the conference.

Problem Statement

You should state the specific problem that you are trying to solve.

The abstract needs to illustrate the purpose of your work. This is the point that will help the conference organizer determine whether or not to include your paper in a conference session.

You have a problem before you: What approach did you take towards solving the problem? You can include how you organized this study and the research that you used.

Important Things to Know When Developing Your Abstract

Do your research on the conference.

You need to know the deadline for abstract submissions. And, you should submit your abstract as early as possible.

Do some research on the conference to see what the focus is and how your topic fits. This includes looking at the range of sessions that will be at the conference. This will help you see which specific session would be the best fit for your paper.

Select Your Keywords Carefully

Keywords play a vital role in increasing the discoverability of your article. Use the keywords that most appropriately reflect the content of your article.

Once you are clear on the topic of the conference, you can tailor your abstract to fit specific sessions.

An important part of keeping your focus is knowing the word limit for the abstract. Most word limits are around 250-300 words. So, be concise.

Use Example Abstracts as a Guide

Looking at examples of abstracts is always a big help. Look at general examples of abstracts and examples of abstracts in your field. Take notes to understand the main points that make an abstract effective.

Avoid Fillers and Jargon

As stated earlier, abstracts are supposed to be concise, yet informative. Avoid using words or phrases that do not add any specific value to your research. Keep the sentences short and crisp to convey just as much information as needed.

Edit with a Fresh Mind

After you write your abstract, step away from it. Then, look it over with a fresh mind. This will help you edit it to improve its effectiveness. In addition, you can also take the help of professional editing services that offer quick deliveries.

Remain Focused and Establish Your Ideas

The main point of an abstract is to catch the attention of the conference organizers. So, you need to be focused in developing the importance of your work. You want to establish the importance of your ideas in as little as 250-300 words.

Have you attended a conference as a student? What experiences do you have with conference abstracts? Please share your ideas in the comments. You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to different aspects of research writing, presenting, and publishing answered by our team that comprises subject-matter experts, eminent researchers, and publication experts.

best article to write a good abstract

Excellent guidelines for writing a good abstract.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Trending Now

- Upcoming Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Mastering Research Funding: A step-by-step guide to finding and winning grants

Identifying Relevant Funding Opportunities Understanding the Funder’s Perspective Crafting a Strong Grant Proposal Maximizing Resources…

- Career Corner

Academic Webinars: Transforming knowledge dissemination in the digital age

Digitization has transformed several areas of our lives, including the teaching and learning process. During…

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

Mastering Research Grant Writing in 2024: Navigating new policies and funder demands

Entering the world of grants and government funding can leave you confused; especially when trying…

How to Create a Poster That Stands Out: Tips for a smooth poster presentation

It was the conference season. Judy was excited to present her first poster! She had…

Academic Essay Writing Made Simple: 4 types and tips

The pen is mightier than the sword, they say, and nowhere is this more evident…

Recognizing the Signs: A guide to overcoming academic burnout

Intersectionality in Academia: Dealing with diverse perspectives

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Industry News

- Publishing Research

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

How to Make a Word Presentation: A Step-by-Step Guide

In today’s digital world, presentations have become a fundamental tool for sharing information effectively. when it comes to making impactful presentations, microsoft word offers a user-friendly and versatile solution. in this step-by-step guide, we will walk you through the process of creating a word presentation that captivates your audience. let’s dive in.

Step 1: Planning your Presentation

Before diving into the creation process, it’s crucial to plan your presentation carefully. Consider your audience, the key message you want to convey, and the overall structure of your presentation.

- Create an outline of your presentation, including main points and subtopics;

- Gather and organize your content, such as text, images, and graphs;

- Define the visual style or theme you want to apply;

- Set a timeline and allocate time for researching, creating, and rehearsing your presentation.

Step 2: Open Microsoft Word and Select a Template

Once you have a clear plan in mind, open Microsoft Word on your computer and follow these steps:

- Click on the “File” tab, located in the top left corner;

- Select “New” from the dropdown menu;

- Choose a presentation template that suits your topic and preferences. You can browse through the available templates or search for a specific one using the search bar.

Step 3: Customize the Layout and Design

After selecting a template, it’s time to customize it according to your needs. Word provides various tools to modify the layout, design, and overall appearance of your presentation.

- Click on the placeholders to replace the default text with your own content;

- Modify the font, size, and color of the text to create visual interest;

- Insert or delete additional slides as required;

- Add images, charts, or other visual elements to enhance your message;

- Experiment with different layouts and design options until you achieve the desired look.

Step 4: Polish Your Presentation

Once you’ve customized the layout and design, it’s essential to review and polish your presentation to ensure its coherence and professionalism.

- Review the content for grammar and spelling errors;

- Check the overall flow and logical sequence of information;

- Ensure consistency in the use of fonts, colors, and styles;

- Practice your presentation to identify any areas that need improvement or clarification;

- Edit and refine your slides until you are satisfied with the final result.

Step 5: Save and Share Your Presentation

After perfecting your presentation, it’s time to save it and share it with your audience. Follow these simple steps:

- Click on the “File” tab;

- Select “Save As” from the dropdown menu;

- Choose a location on your computer to save the presentation;

- Enter a descriptive file name and select the desired file format (e.g., .pptx or .pdf);

- Click “Save” to store your presentation.

Creating a Word presentation doesn’t have to be a daunting task. By following this step-by-step guide, you can craft a visually appealing and impactful presentation using Microsoft Word. Remember, careful planning, customization, and diligent polishing are key to creating a successful presentation. Now go ahead and impress your audience with your newfound skills!

How helpful was this article?

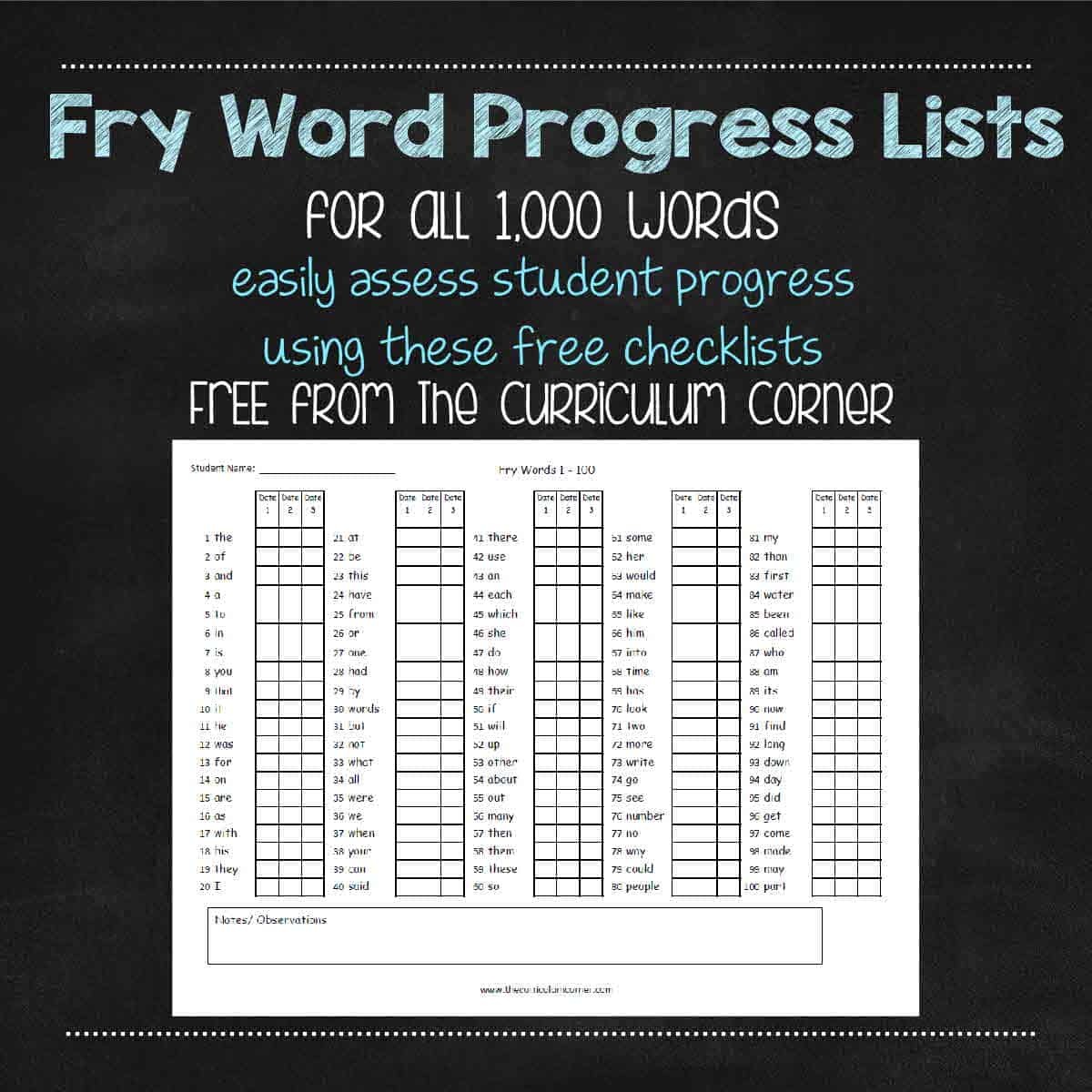

Fry Word PowerPoint

This Fry Word PowerPoint or slide show will help you work on sight words with your students.

This is another free resource for teachers and families from The Curriculum Corner.

We have created these new Fry Word PowerPoints to help you in the classroom.

With many teachers currently working virtually, we know there is a need for new resources to assist you.

What are Fry Words?

If you are new to sight word instruction, start here!

Fry words are a list of 1,000 of the most common words in the English language. They are found on the list from most common to least common.

These 1,000 words are broken down into ten lists.

You can read more about these sight words here: All About Fry Words .

These Fry Word PowerPoint Slides

There are a total of three PowerPoint files for you to download below.

You will find the words in groups of 100.

The PowerPoints cover the first 300 sight words.

The slides will transition every three seconds. You can adjust this as needed.

How Can These Slides be Used?

Assessment These can be used to assess students in person or virtually. Students can read from the slide instead of a smaller list. These slides are great because there is a single word instead of a busy paper with 100 words.

Whole Group Instruction If you like to review sight words as a class, try these slides! You can display the slides on your interactive board so that all students can easily see the words.

These slides are also portable – you can share on your iPad. This might be a great little meaningful time filler in the hallway when you are in the middle of a transition.

Practice Students can read through the words in a small group for a word work center.

You can download these PowerPoint slides here

Looking for other Fry word resources? Try these:

Thank you to Whimsy Clips for the fun sky backgrounds.

As with all of our resources, The Curriculum Corner creates these for free classroom use. Our products may not be sold. You may print and copy for your personal classroom use. These are also great for home school families!

You may not modify and resell in any form. Please let us know if you have any questions.

Wednesday 15th of December 2021

These are great! Thank you!

Elizabeth Altmeier

Sunday 5th of December 2021

Thank you!!!!!!!!

Linda Baird

Monday 18th of October 2021

I really appreciate not having to sit and make up powerpoints with Fry lists. Thank you.

Leticia CORONADO

Tuesday 2nd of March 2021

Tuesday 6th of October 2020

Thank you SO much for sharing so many resources for free! I’m a single mom and new teacher. I can’t afford to buy all of the things I want on TPT. You have helped me sooo much. THANK YOU!!!

- Campus Calendars

- Employment Opportunities

- Majors & Minors

- News & Events

- IT Help Desk

- Mobile Printing

- Directory (Faculty & Staff)

- Offices & Departments

- Map of the Campus

- Visitor Parking

- University Police

Writing Abstracts for a Conference Submission

Identify a conference that fits your research area and topic. Check the deadlines, criteria for submission and acceptance, location, and funding avenues. Once you have decided on an appropriate conference, prepare your research to meet the submission criteria. For example, your conference might ask you to submit an abstract and provide specific guidelines explaining what the criteria for a successful abstract should be in order for it to be accepted at that conference. The next section below will focus on explaining the function and form of an abstract: What is an abstract, how to write an abstract. It will then provide you with NCUR guidelines for a successful abstract and a range of abstract examples from SU students from different majors.

What is an Abstract

What is an Abstract?

- In general, an abstract tells the reader what the research contains. Thus a good abstract should include a clear and brief statement on the purpose of the research, the methods employed, the sample, findings or results, conclusions, and recommendations/ or significance for your field.

- Thus a good abstract is a brief summary (for example, NCUR gives a word limit of 300 words) that introduces the reader to your research study and all its key elements.

Overview: How to Write an Abstract

- After completing your research report, start preparing your abstract. Review your report for its main elements: purpose, research questions, methods, findings or results, conclusions or discussion, and recommendations. Limitations and significance can be included if you have space.

- Now start to write a rough draft of your abstract. It may be over the word limit at this stage. Once you have a rough draft down, go back and edit your abstract for organization, coherence, focus, flow, redundancy, and typos.

- Your final version of the abstract should meet all the required word count and compositional criteria, be tightly edited, clear and focused, and without any grammatical errors.

- A good abstract should ultimately reflect all the key elements of your study for the reader and give them a good idea of what you wanted to do, how you did it, what you found, and its significance.

Students submitting NCUR abstracts should:

- Complete **all** required fields on the online submission form

- Submit only one abstract per presentation (the first author/primary presenter can submit this on all co-authors’ behalf).

- Upon submitting, check that you receive a confirmation email from [email protected] . Check that it has not gone to spam.

NCUR Abstracts Guidelines:

- Clearly state the central research question and/or purpose of the project.

- Provide brief, relevant scholarly or research context (no actual citations required) that demonstrates its attempt to make a unique contribution to the area of inquiry.

- Provide a brief description of the research methodology.

- State conclusions or expected results and the context in which they will be discussed.

- Include text only (no images or graphics)

- Be well-written and well-organized. Check for typos—proof-read!

Other formatting guidelines:

- References are allowed within abstracts, but not required.

- Double-check your title: This will appear on the program exactly as you type it.

- Likewise, check the spelling for the names of all authors and co-authors (first name, middle name, last name).

- The form will not process all formatting and special characters (e.g., scientific symbols). Use plain text format for your abstract.

- There is space in the form to include a link to online documentation, formulas, images, music files, etc. in support of your submission. You may use this space to provide a link to a location to view your abstract in its original form.

- It’s a good idea to work on your abstract with your mentor’s support on a word document. Once it is ready to submit, you can copy and paste it on the online form. Don’t wait till the last minute to do so.

- Abstracts are usually 200-300 words long with no paragraph breaks. MAXIMUM LENGTH = 300 WORDS!

Have the following information available when submitting your abstract:

- Name and e-mail address for each faculty mentor and co-author

Jessica Clark, PhD and Chrys Egan, PhD Co-Directors, Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities Email: [email protected] Phone number: 410-677-0083

- Presentation type: oral, poster, visual arts, or performing arts

- Field of study.

Sample NCUR Poster and Oral Abstracts

Robert R. Audley, Amelia Willoughby (Dr. Lucy Morrison), Political Science Department, Salisbury University, 1101 Camden Avenue, Salisbury, MD 21801

From a rally at our nation’s capital, to the words of world leaders, to the thoughts of a survivor, our documentary about genocide in Sudan grew out of a class investigating genocide as a social, political, and humanitarian topic. Are we world citizens or individualists? Our documentary shows these aspects as intrinsically intertwined. Through speeches and interviews, we explore the conflicting arguments of survivors simply asking for help, the pitfalls of political promises not kept, and those in academia asking “What can we really do?” Our documentary entertains arguments in favor of both intervention and isolationism and supports these arguments with interviews from those closest to the conflict, including a survivor from Darfur, nationally known activists, and footage of our President and Secretary of State. President Barack Obama is shown advocating for a cautious approach to the genocide in Darfur, and Hilary Clinton is shown making her first serious speech regarding the issue. Our documentary portrays the limitations of awareness campaigns, political speeches, and academic debates. These only go so far and more tangible outreach must be undertaken to make real change happen. In our presentation, we will outline how we used a class about past genocides as a springboard for composing a documentary that captures the conversation surrounding the current struggle in Darfur, and gives voice to those most closely related to it. We will elaborate on the technical trials, such as editing and compiling footage with Avid software, along with the educational process of contacting interviewees on such a controversial topic, and the ways in which this process shaped our final product.

Velora A. Branch, Matthew J. Copeland, (Chasta L. Parker), Salisbury University, Department of Chemistry, Salisbury, Maryland 21801

Adiponectin (Acrp30) is a protein hormone released from adipocytes that has been shown to have anti-proliferative effects on obesity related cancer cells. Three cellular receptors from the progestin and AdipoQ Receptor (PAQR) family have been identified that can actively bind Acrp30: AdipoR1 and AdipoR2, located on the cell membrane; and AdipoR3 in the Golgi body. Prior research has indicated that AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 are involved in the anti-proliferative effect but there has been minimal research on AdipoR3 (PAQR3). The production of AdipoR3 mRNA in HT-29 human colorectal cancer cells in the presence or absence of Acrp30 was quantified using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). The difference in the abundance of AdipoR3 mRNA can be related to a change in demand for the receptor by the cell, signifying its importance. The mRNA of the cell was extracted, converted to cDNA, and evaluated by qRT-PCR using fluorescent probe primers that emit light in the presence of UV-Vis radiation. The quantity of mRNA originally present is directly related to the intensity of emission. Following this study, a knockdown of AdipoR3 in the cell will be performed using RNA silencing techniques after which the anti-proliferative effect of Acrp30 on HT-29 cells will be reanalyzed. Simultaneously, the growth rate of human cancer cells will be assayed in the presence and absence Acrp30. Preliminary results confirm the anti-proliferative nature of Acrp30 and also indicate altered AdipoR3 mRNA abundance in adiponectin treated colorectal cancer cells. This work was supported by the Henson School of Science, the department of chemistry at Salisbury University as well as the Cort Scholarship.

Kori L. Asbury, Ryan J. Maluski, (Jonathan Munemo), Economics Department, Salisbury University, Salisbury, MD 21801

The gravity equation, as derived from the physics gravity equation, has been used to explain the value of international economic trade. Additionally, the Index of Intra-Industry Trade explains how much one country can import the same good that it is exporting under perfect competition. Our goal is to test the credibility and functionality of this economic equation, and determine its ability to explain the value and importance of international economic trade. Using historical United States international trade data, we compiled 132 countries that the United States has traded with over a period of the past twenty six years. From this data we were able to calculate the natural log of B, using the gravity term and trade. The natural log of B signifies the magnitude of the relationship between the variables of the gravity equation, including Gross Domestic Product and distance. It has been found that the larger the country’s Gross Domestic Product, or the shorter the distance between two counties, the stronger the trade relationship will be. This in turn, will cause more trade between two countries. From our research, we have found a strong positive correlation in the calculation of the gravity equation, in dealing with the relationship between overall trade relative to distance and Gross Domestic Product. In terms of the Index of Intra-Industry Trade, Gross Domestic Product and distance have little influence on the intra-industry trade value.

Brent A. Alogna (Miguel Mitchell) Department of Chemistry, Salisbury University, Salisbury, MD 21801

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the bacterium responsible for the disease tuberculosis. One class of drugs that show antitubercular properties are promazine-based compounds, which inhibit the type II NADH-menaquinone dehydrogenase (ndh-2) enzyme in the electron transport chain of M. tuberculosis. A triflupromazine derivative with a 4-chlorobenzyl substituent on the non-2-trifluoromethyl phenothiazine base nitrogen has shown the most potency against M. tuberculosis, but it produces a compound with a permanent positive charge, which decreases the oral bioavailability of the compound. In an attempt to increase the oral bioavailability of the drug, while maintaining the antitubercular potency, a demethylated N-4-chlorobenzyl triflupromazine derivative was synthesized. Triflupromazine was demethylated with 1-chloroethyl chloroformate and 1,2-dichloroethane, followed by methanolysis, which produced the desired product in 68-92% yield (3 trials), structure confirmed by its 1H-NMR spectrum. The intermediate of the demethylation process, formed before methanolysis, was also isolated and its structure was tentatively determined by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR. Direct alkylation of demethylated triflupromazine with 4-chlorobenzyl chloride resulted in a demethylated N-4-chlorobenzyl triflupromazine derivative, synthesized with yields of 40.9% and 71.3% respectively. Its structure was confirmed by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and GC-MS. In order to try and make the demethylation process more environmentally friendly, water was substituted for methanol in the demethylation procedure. We were pleased to discover that the same demethylation product was obtained in 52.1% yield. In vitro and in vivo MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) assays of our final compound against M. tuberculosis will be performed at U. Illinois-Chicago's Institute for Tuberculosis Research. The associated bacteriological studies on the demethylated N-4-chlorobenzyl triflupromazine compound in mice should show an increase in the oral bioavailability of the drug, with the same or higher antitubercular potency.

Rebecca Abelman, Diane Davis, Medical Laboratory Science, Salisbury University, Salisbury, MD 21801

Antibiotic-resistant microorganisms are becoming an increasingly important medical issue in the 21st century. With the elevated use of antibiotics and better systems of delivering health care, these bacteria have mutated to survive. The nature of these antibiotic-resistant organisms makes them dangerous not only for the public, but also for the health care workers that come in contact with them on a regular basis. The impact of these bacteria on patient health and safety has been extensively researched, but these studies tend to be patient-focused and often exclude health care workers who come in contact with the microbes daily. They are at high risk from not only patients but also from contaminated objects and surfaces known as fomites. Medical laboratory scientists (MLS) face an unusually high risk due to the amplified organism loads in specimens in microbiology laboratories. Although the increased loads allow for better identification, testing, and manipulation of the organism, they also expose the MLS to very concentrated amounts of hazardous microbes. This inspired me to research Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) in relation to laboratories. I determined the survival rate of VRE broth cultures on common laboratory surfaces, which gave me an indication of the risks associated with unnoticed spills. The four surfaces I tested were floor tiles, glass, melamine countertops, and polyester/cotton laboratory coats. Broth inoculated with a standard amount of CFUs (colony forming units) of Enterococcus faecium was placed on the surfaces and the number of organisms surviving on each surface was checked at timed intervals. BBL CHROMagar® plates for VRE were used to test for the VRE on the fomites. Measuring the survival rate of this organism will contribute to the growing knowledge of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and aid in the protection of laboratory workers and the public alike.

Stacie L. Manger Dr. Haven Simmons Communications Salisbury University 1101 Camden Ave Salisbury, MD 21801

While significant research is devoted to traditional American sports such as baseball, football and basketball, soccer is largely an afterthought. Soccer is arguably the most popular sport globally with millions of ardent followers, but it struggles to compete in the United States. This paper examines the marketing, public relations and crisis communication strategies of professional soccer in America, where Major League Baseball, the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, NASCAR, professional golf and tennis attract more fans and media attention. The MLS (Major League Soccer League) must be innovative and aggressive to survive despite the popularity of American youth soccer. The league has recruited expensive foreign stars such as David Beckham, Guillermo Barros Schelotto and Cuauhtemoc Blanco, for example, but salary disparities remain problematic compared to other professional sports. Beckham's $6.5 annual salary is compared to players making less than six figures. Critics argue the MLS Cup at RFK Stadium in November arrived at a critical juncture for the league. They also wonder whether TV ratings and media coverage have improved enough to bolster a league that is expanding to 18 teams in the next five years. Most people consider the increasing number of team owners in the MLS a positive development. In addition, more stadiums catering exclusively to soccer have been constructed. The researcher weighs these critical factors according to marketing, public relations and crisis management tactics employed by the league, concluding with recommendations for enhancing its reputation and popularity against daunting odds.

Amanda J. Baker, (Dr. Gina Bloodworth), Department of Geography and Geosciences, Salisbury University, Salisbury, MD 21801

Monitoring and improving the health of the Chesapeake Bay has been a rising concern over the past 40 years. It has been proven that storm water run-off frequently contains unfiltered pollutants, which have devastating effects on water quality and consequently the quality of life of organisms dependent upon that water. Fluctuations in population and the rapid urban and suburban development occurring in the Chesapeake Bay region from the 1970s to the present day involve the introduction of more impervious surfaces to this watershed basin, increasing the amount of run-off. Best Management Practices (BMPs) for monitoring and controlling storm water have evolved over the decades, for a variety of reasons. This paper will map and examine the connection between rapid urbanization and levels of storm water run-off; from this investigation, a typology of BMPs implemented in the Chesapeake Bay watershed basin will be generated. Finally, the research seeks patterns in the underlying implications of the availability and popularity of select BMPs.

Stephen Abresch, Lucy Morrison, Department of Philosophy, Salisbury University, 1011 Camden Avenue, Salisbury, Md, 21804

This work is an investigation into the experience of repulsion and its greater meaning in better understanding the way in which we are. The intimate relationship between a realization of imperfection and an experience of repulsion is focused on as revealing the true roots of repulsion: the clash of the belief of perfection and the inherent imperfection of human beings. The wisdom that no accurate knowledge of the world is gained before accurate self-knowledge is central to this work, and no self-knowledge is complete lest it understand that evil exists not only in the world, but within us as well. In essence, this paper seeks to understand not only the experience of repulsion in conjunction with an experience of imperfection (whether it be personality flaws, addiction, even physical imperfection) but also why we are so averse to accepting our imperfection in the first place. In investigating this topic I will be examining the experience of Exile and the implications it has for a dialogue on repulsion and taking a look at the modern day leper, the AIDS victim. In addition to these I will be using the works of St. John of the Cross, Richard Rorty, Carl Jung, Elie Wiesel, Rebalye and Jerome Miller to better explicate the relationship between repulsion and human revelation.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

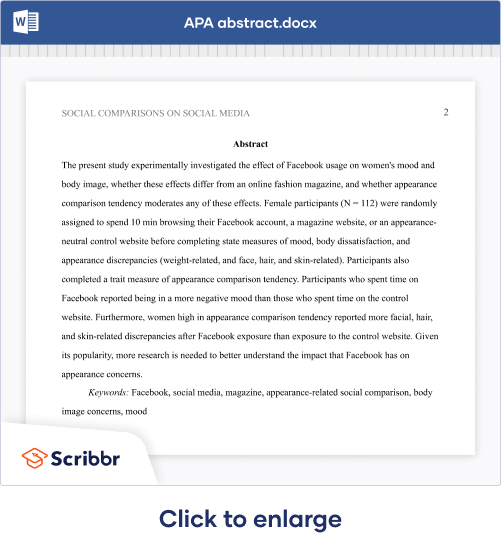

How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples

Published on February 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Eoghan Ryan.

An abstract is a short summary of a longer work (such as a thesis , dissertation or research paper ). The abstract concisely reports the aims and outcomes of your research, so that readers know exactly what your paper is about.

Although the structure may vary slightly depending on your discipline, your abstract should describe the purpose of your work, the methods you’ve used, and the conclusions you’ve drawn.

One common way to structure your abstract is to use the IMRaD structure. This stands for:

- Introduction

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements.

In a dissertation or thesis , include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Abstract example, when to write an abstract, step 1: introduction, step 2: methods, step 3: results, step 4: discussion, tips for writing an abstract, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about abstracts.

Hover over the different parts of the abstract to see how it is constructed.

This paper examines the role of silent movies as a mode of shared experience in the US during the early twentieth century. At this time, high immigration rates resulted in a significant percentage of non-English-speaking citizens. These immigrants faced numerous economic and social obstacles, including exclusion from public entertainment and modes of discourse (newspapers, theater, radio).

Incorporating evidence from reviews, personal correspondence, and diaries, this study demonstrates that silent films were an affordable and inclusive source of entertainment. It argues for the accessible economic and representational nature of early cinema. These concerns are particularly evident in the low price of admission and in the democratic nature of the actors’ exaggerated gestures, which allowed the plots and action to be easily grasped by a diverse audience despite language barriers.

Keywords: silent movies, immigration, public discourse, entertainment, early cinema, language barriers.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You will almost always have to include an abstract when:

- Completing a thesis or dissertation

- Submitting a research paper to an academic journal

- Writing a book or research proposal

- Applying for research grants

It’s easiest to write your abstract last, right before the proofreading stage, because it’s a summary of the work you’ve already done. Your abstract should:

- Be a self-contained text, not an excerpt from your paper

- Be fully understandable on its own

- Reflect the structure of your larger work

Start by clearly defining the purpose of your research. What practical or theoretical problem does the research respond to, or what research question did you aim to answer?

You can include some brief context on the social or academic relevance of your dissertation topic , but don’t go into detailed background information. If your abstract uses specialized terms that would be unfamiliar to the average academic reader or that have various different meanings, give a concise definition.

After identifying the problem, state the objective of your research. Use verbs like “investigate,” “test,” “analyze,” or “evaluate” to describe exactly what you set out to do.

This part of the abstract can be written in the present or past simple tense but should never refer to the future, as the research is already complete.

- This study will investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

- This study investigates the relationship between coffee consumption and productivity.

Next, indicate the research methods that you used to answer your question. This part should be a straightforward description of what you did in one or two sentences. It is usually written in the past simple tense, as it refers to completed actions.

- Structured interviews will be conducted with 25 participants.

- Structured interviews were conducted with 25 participants.

Don’t evaluate validity or obstacles here — the goal is not to give an account of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, but to give the reader a quick insight into the overall approach and procedures you used.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Next, summarize the main research results . This part of the abstract can be in the present or past simple tense.

- Our analysis has shown a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis shows a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

- Our analysis showed a strong correlation between coffee consumption and productivity.

Depending on how long and complex your research is, you may not be able to include all results here. Try to highlight only the most important findings that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions.

Finally, you should discuss the main conclusions of your research : what is your answer to the problem or question? The reader should finish with a clear understanding of the central point that your research has proved or argued. Conclusions are usually written in the present simple tense.

- We concluded that coffee consumption increases productivity.

- We conclude that coffee consumption increases productivity.

If there are important limitations to your research (for example, related to your sample size or methods), you should mention them briefly in the abstract. This allows the reader to accurately assess the credibility and generalizability of your research.

If your aim was to solve a practical problem, your discussion might include recommendations for implementation. If relevant, you can briefly make suggestions for further research.

If your paper will be published, you might have to add a list of keywords at the end of the abstract. These keywords should reference the most important elements of the research to help potential readers find your paper during their own literature searches.

Be aware that some publication manuals, such as APA Style , have specific formatting requirements for these keywords.

It can be a real challenge to condense your whole work into just a couple of hundred words, but the abstract will be the first (and sometimes only) part that people read, so it’s important to get it right. These strategies can help you get started.

Read other abstracts

The best way to learn the conventions of writing an abstract in your discipline is to read other people’s. You probably already read lots of journal article abstracts while conducting your literature review —try using them as a framework for structure and style.

You can also find lots of dissertation abstract examples in thesis and dissertation databases .

Reverse outline

Not all abstracts will contain precisely the same elements. For longer works, you can write your abstract through a process of reverse outlining.

For each chapter or section, list keywords and draft one to two sentences that summarize the central point or argument. This will give you a framework of your abstract’s structure. Next, revise the sentences to make connections and show how the argument develops.

Write clearly and concisely

A good abstract is short but impactful, so make sure every word counts. Each sentence should clearly communicate one main point.

To keep your abstract or summary short and clear:

- Avoid passive sentences: Passive constructions are often unnecessarily long. You can easily make them shorter and clearer by using the active voice.

- Avoid long sentences: Substitute longer expressions for concise expressions or single words (e.g., “In order to” for “To”).

- Avoid obscure jargon: The abstract should be understandable to readers who are not familiar with your topic.

- Avoid repetition and filler words: Replace nouns with pronouns when possible and eliminate unnecessary words.

- Avoid detailed descriptions: An abstract is not expected to provide detailed definitions, background information, or discussions of other scholars’ work. Instead, include this information in the body of your thesis or paper.

If you’re struggling to edit down to the required length, you can get help from expert editors with Scribbr’s professional proofreading services or use the paraphrasing tool .

Check your formatting

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation or submitting to a journal, there are often specific formatting requirements for the abstract—make sure to check the guidelines and format your work correctly. For APA research papers you can follow the APA abstract format .

Checklist: Abstract

The word count is within the required length, or a maximum of one page.

The abstract appears after the title page and acknowledgements and before the table of contents .

I have clearly stated my research problem and objectives.

I have briefly described my methodology .

I have summarized the most important results .

I have stated my main conclusions .

I have mentioned any important limitations and recommendations.

The abstract can be understood by someone without prior knowledge of the topic.

You've written a great abstract! Use the other checklists to continue improving your thesis or dissertation.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

An abstract for a thesis or dissertation is usually around 200–300 words. There’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check your university’s requirements.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

The abstract appears on its own page in the thesis or dissertation , after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 18). How to Write an Abstract | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/abstract/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis or dissertation introduction, shorten your abstract or summary, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Write an outline. A good place to start is with a basic outline, which might include: introduction and background, description of the study, preliminary findings, conclusion, and contributions. Now, instead of writing 300 words, your goal becomes writing a few sentences or a short paragraph for each section in the outline.

Presentation. Undergraduate Research Hub. summary of the information in your presentation. A well-prepared abstract enables readers to identify the basic content quickly and accurately, to determine its relevance to their interests or purpose and then to decide whether they want. University of Minnesota. Introduction: (1-3 sentences)

View only. Rec. 1 Fry’s Sight Words 1-300 SIGHT WORD PRACTICE 2 the 3 of 4 and 5 a 6 to. Fry’s Sight Words 1-300 SIGHT WORD PRACTICE. HTML view of the presentation.

An abstract is an ultra-brief summary of your proposed presentation; it should be no longer than 300 words and contain just the key points of your speech. A conference abstract is also known as a registration prospectus, an information document or a proposal.

Formula: topic + title + motivation + problem statement + approach + results + conclusions = conference abstract. Here are the main points that you need to include. Title. The title needs to grab people’s attention. Most importantly, it needs to state your topic clearly and develop interest.

Creating a Word presentation doesn’t have to be a daunting task. By following this step-by-step guide, you can craft a visually appealing and impactful presentation using Microsoft Word. Remember, careful planning, customization, and diligent polishing are key to creating a successful presentation.

How do you squeeze your whole dissertation into a 300-word abstract? Since the abstract will be the first part that people read, it's important to get it rig...

This Fry Word PowerPoint or slide show will help you work on sight words with your students. Free for practice and assessment from The Curriculum Corner.

Thus a good abstract is a brief summary (for example, NCUR gives a word limit of 300 words) that introduces the reader to your research study and all its key elements. Overview: How to Write an Abstract. After completing your research report, start preparing your abstract.

Abstracts are usually around 100–300 words, but there’s often a strict word limit, so make sure to check the relevant requirements. In a dissertation or thesis, include the abstract on a separate page, after the title page and acknowledgements but before the table of contents.