Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

PhD Work-Life Balance: 5 Tips to Help Students Manage the PhD Workload

The journey toward acquiring a doctoral degree is extremely rewarding, yet, it is perhaps one of the most challenging of all academic journeys. Every young PhD student begins this journey with a lot of enthusiasm and curiosity, harboring a dream of contributing to science and society through a dedicated work plan for PhD. However, on this long journey as a student pursues their PhD, work-life balance goes haywire.

On striving to achieve a PhD work-life balance , students often find themselves perplexed. Eventually the stressors of the PhD workload may create a dent in their dreams as the rough edges of the journey become apparent. Many students take a long time to acknowledge these ‘expectation v/s reality’ issues, and this in turn leads to anxiety, affecting their productivity as well as well-being.

Despite having a work plan for PhD research, it is hard for students, at least in the initial stages, to reconcile with the fact that their work plan for PhD is never as fool proof as the one they envisioned on paper. Experiments may fail, results aren’t always ‘perfect’, and timelines can go haywire if standardization protocols get prolonged. Even after acknowledging these issues, there is the constant pressure of meeting mentor expectations, which can hamper the students’ lifestyle and overall PhD work-life balance. It may lead to long work hours, including night shifts and working over weekends.

For students living away from their home country , maintaining a PhD work-life balance comes with an added challenge of acclimatizing to new cultures. At times, these challenges even adversely affect their mental health giving rise to anxiety issues, burnout, or even imposter syndrome, all of which can hamper their work plan for PhD research and, in turn, their productivity. Although mental health issues are undoubtedly one of the biggest challenges faced by PhD students during their doctoral journey, the impact of poor mental health is unfortunately a largely overlooked topic in academia. 1

While the need of striking a PhD work-life balance is understood by most students, implementing it can be tough, largely due to the limited availability of resources that can guide students toward creating and maintaining an effective work plan for PhD research.

The work plan for PhD varies for each student as it’s tailored to their needs. So, creating a standard schedule sample to manage PhD workload is not advisable. However, here are some tips and advice for PhD students to make this process of creating an optimal PhD student lifestyle for themselves easier and more enjoyable. 2,3

Table of Contents

1. Manage time effectively

To understand how to achieve a PhD work-life balance, students need to consciously identify the time and energy leakages occurring throughout the day . This will help them in identifying the patterns in which they are spending time. Tasks requiring similar mental capabilities can be grouped together during the day, thereby minimizing decision fatigue. Similarly, initiating collaborations and rejecting additional responsibilities can save a considerable amount of time leading to an improved execution of the PhD work plan.

2. Establish a routine

The doctoral journey is a bumpy ride with unpredictable twists and turns. This is the main cause of anxiety in many students since, as human beings, we are wired to function optimally within a regulated and controlled system. While factors such as the PhD workload and work hours cannot be optimized beyond a certain point, the time outside the lab can be managed with more ease. By dedicating sufficient time toward household chores and unwinding activities, and creating a PhD work-life balance, students can develop a sense of security through a sustainable and predictable daily routine. Having a work plan for PhD is good but having a leisure plan is better to help you maintain a healthy PhD student lifestyle that can, in turn, boost productivity at work.

3. Invest in mental and physical well-being

To get the right work plan for PhD, research, identify, acknowledge, and then tackle the stressors that hamper physical and mental well-being. Engaging in physical exercises, thought-journaling, and (if needed) seeking advice from a therapist, preferably someone experienced in advising PhD students, can be some ways to achieve a lifestyle based on PhD work-life balance.

4. Indulge in a hobby

The anxiety of managing the PhD workload can be balanced by pursuing a hobby where the mind is free to explore without any limitations. This can, in turn, lead to enhanced creativity and innovation in ideas at work and help achieve a sustainable PhD work-life balance. An improved PhD student lifestyle can help one flourish.

5. Connect regularly with friends and family

It is impossible for friends and family members to empathize completely with the problems faced during the doctoral journey, especially if they do not share the same love for research. But it is essential to connect with them regularly, as they can provide an objective and impartial lens to work-related problems. This can help in resolving the problems altogether or make the problems seem totally insignificant. Either way, it can help tackle the anxiety associated with failures in executing the work plan for PhD research.

By now it may be clear that in the journey of attaining the right PhD work-life balance, students should make a series of conscious choices and lifestyle changes that need to be made every single day. Exercising these choices is not an easy task, but can be extremely rewarding in terms of reducing anxiety and burnout-related issues, as well as to improve productivity and well-being in the long run.

- Mental health of graduate students sorely overlooked. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01751-z.

- Bartlett, M. J., Arslan, F. N., Bankston, A. & Sarabipour, S. Ten simple rules to improve academic work–life balance. PLOS Comput. Biol. 17 , e1009124 (2021).

- Self-care for the scientist. https://www.apa.org https://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2015/09/matters.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

Research Paper Appendix: Format and Examples

Staff & Students

- Staff Email

- Semester Dates

- Parking (SOUPS)

- For Students

- Student Email

- SurreyLearn

Postgraduate life at Surrey

Discover more about what it's like to be a postgraduate student at surrey., maintaining a work-life balance during your phd.

Being a PhD student can be tough at times. One of the main reasons for this is the pressure in academia to ‘publish or perish’. But it doesn’t have to be this way. I think that by pushing back on the culture of overwork in academia, we can do great research while maintaining our mental wellbeing.

Making space for rest

It’s taken me a few years to fully appreciate how important it is to set clear work boundaries. This has of course been more challenging given the impact of the pandemic and the fact we are working from home more. I find it much easier to ‘switch off’ from work when I’ve had to do my commute home.

I recently made a change to start working in a room that isn’t my bedroom and it’s made such a difference. I now have a much clearer workspace at home which helps me transition into rest time at the end of the day and at the weekends. This means that there’s only one room in the house that I associate with work now which allows me to get ‘in the zone’ and to make that work-life division a bit clearer—work happens in the home office and nowhere else at home.

Communicating boundaries

Communication with your supervisor is one of the key aspects of a successful PhD and work boundaries are something that comes into this too. You may sometimes have to work on the weekends if you have an experiment to do and equipment booked, but I always try to keep my weekends as work-free as I can.

One of the best ways to keep this time as rest time is to not look at or respond to work emails. I use a website blocking app to prevent me from being able to access my emails over the weekend as it’s hard for me to resist the urge to ‘just check it’ in my downtime. My supervisor knows that unless I’m booked in for lab time, I’m not available over the weekend. This helps me truly disconnect for those two days so I can come to my work the next week fully refreshed and ready to go.

Make time for yourself

At the end of the day, the key output of a PhD is the researcher that you become. It may seem like your publications and thesis are the most important thing but to me, it’s all about training to be a good researcher so that I can go on to have a research-focused career. So, it makes no sense to me to complete my PhD but at the expense of my mental wellbeing. I suffer from a few mental illnesses and have done since my teenage years, so I was aware going into my PhD that this was something I needed to be careful about managing. There have been a couple of blips, but on the whole, my mental health is currently better than it has been in many, many years.

Resting when I need to and not overworking is a significant factor in maintaining this. Over the years, it’s become clear that I can’t work to a high standard when I’m in a mental health ‘slump’ and that making time for myself can prevent that. I try to make sure that I use my weekends and evenings to talk to friends and family as well as indulging in my hobbies. My hobbies tend to be fairly relaxing which helps me recharge after a long day of research.

Getting the right balance

Balance is what it all comes down to. I think there is something to the saying ‘work hard, play hard’—by giving it my all during the workday and allowing space for rest outside of that, I’ve been able to cultivate a productive PhD work pattern. This will vary depending on the individual, so I’d encourage you to experiment with what work patterns work best for you. For me, it’s a 9-5ish workday but you may find that working later in the day maximises your productivity. By finding your own work methods, you can thrive as a PGR.

MBA Half-Time: How it is going

My favourite places on campus.

Accessibility | Contact the University | Privacy | Cookies | Disclaimer | Freedom of Information

© University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey, GU2 7XH, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1483 300800

- Essay Topic Generator

- Essay Grader

- Reference Finder

- AI Outline Generator

- Paragraph Expander

- Essay Expander

- Literature Review Generator

- Thesis Generator

- Text Editing Tools

- AI Rewording Tool

- AI Sentence Rewriter

- AI Article Spinner

- AI Grammar Checker

- Spell Checker

- PDF Spell Check

- Paragraph Checker

- Free AI Essay Writer

- Paraphraser

- Grammar Checker

- Citation Generator

- Plagiarism Checker

- AI Detector

- AI Essay Checker

- Proofreading Service

- Editing Service

- AI Writing Guides

- AI Detection Guides

- Citation Guides

- Grammar Guides

- Paraphrasing Guides

- Plagiarism Guides

- Summary Writing Guides

- STEM Guides

- Humanities Guides

- Language Learning Guides

- Coding Guides

- Top Lists and Recommendations

- AI Detectors

- AI Writing Services

- Coding Homework Help

- Citation Generators

- Editing Websites

- Essay Writing Websites

- Language Learning Websites

- Math Solvers

- Paraphrasers

- Plagiarism Checkers

- Reference Finders

- Spell Checkers

- Summarizers

- Tutoring Websites

- Essay Checkers

- Essay Topic Finders

Most Popular

Professors share 5 myths students believe about college, anxiety among students: what do teachers think about it, dorm overbooking and transitional housing: problems colleges are trying to solve, phd work-life balance: tips and successful stories.

Image: freepik.com

Many PhD studetns are curious how to ease their life when writing their thesis and research papers. Today, we are exploring ways of setting successful work-life boundaries during a PhD program . It brings into focus the challenges and triumphs of individuals who have prioritized personal well-being over an accelerated academic pace, advocating for a balanced lifestyle even amidst rigorous research commitments.

Key Takeaways:

- PhD students are establishing work hours to balance study and leisure time.

- Academic success is more about productivity and creativity than long hours.

- The myth of the 24/7 PhD student is being debunked, emphasizing researchers’ well-being.

Work-Life Harmony in the Pursuit of a PhD

In the realm of academia, striving for a work-life balance while pursuing a PhD is a common challenge. Achieving this equilibrium often means setting strict boundaries on work hours, an approach that many students adopt. Yet, the pivotal question remains: can a successful PhD journey be achieved within a “9-5” workday structure?

Many students resonate with the philosophy of treating their PhD like a traditional job . They establish clear working hours—often adhering to a typical Monday to Friday, 8 AM to 4 PM schedule—and maintain this routine, barring a few exceptions when large experiments or looming deadlines require additional hours. During off-hours, they embrace activities that rejuvenate their spirits, such as reading for pleasure, exercising, spending time outdoors, or being with friends.

Some scholars, however, have the flexibility to align their working hours to their optimal productivity periods. They work when they feel most productive, whether it’s over the weekend or on a typical workday. Others meticulously plan their schedules, integrating breaks and personal activities during work hours to maintain their well-being.

A common thread running through these narratives is the significance of maintaining a strict boundary between work and personal time. In fact, many successful PhD students refrain from extending their work hours or weekends, unless driven by sheer personal interest or unavoidable circumstances. They guard their leisure time fiercely, allowing themselves to unplug from their research activities completely.

At the heart of this debate lies a shared belief: the need for a healthy work-life balance in academia. As one student shared:

“Academia is a job. Nothing less and most certainly nothing more.”

This viewpoint counters the widely held notion that academic success necessitates long, grueling hours. According to these scholars, the real key to triumph in academia is not merely the hours put in but the productivity and creativity exhibited during those hours.

One student remarked:

“I am not even sure a PhD would be shorter if you didn’t establish these work-life boundaries, because you’d get burnt out quickly, make stupid mistakes, lose creativity, and potentially need months to recover.”

However, the feasibility of adhering to strict work-life boundaries often depends on the nature of the PhD work and the culture of the institution. In labs with extensive experiments or fields where work cannot be compartmentalized into regular workdays, longer hours are sometimes inevitable.

Nevertheless, the general consensus among these scholars points towards the importance of maintaining a healthy work-life balance during their PhD journey. They utilize various tools, like the Focus To-Do app, to monitor and control their working hours effectively. By observing these boundaries, they have been successful in their academic pursuits without compromising their mental well-being or personal lives.

As one student summarized:

“It’s half luck and half a choice, but I would really encourage you to make that choice if you can! I’m five years into academia…and I’m not burnt out, and have been able to sustain lots of lovely meaningful relationships which remind me there’s life outside of academia!”

Debunking the “Always-on” Culture in Academia

The notion of the 24/7 PhD student, ceaselessly working at their research in a constant state of academic toil, has for a long time been perceived as the ideal within academia. However, this “always-on” culture is increasingly being challenged as not only unrealistic but potentially harmful.

Let’s take the example of a typical PhD student, who might occasionally pull 16-hour workdays to manage experimental work. While this sometimes becomes a necessity, it is far from being a regular or sustainable practice. Instead, sustainable work habits emphasize the importance of balance and the risks associated with burnout.

More and more academics are adopting a results-oriented approach that adjusts to the task demands rather than adhering rigidly to a conventional 9-to-5 structure. The idea of balance isn’t limited to academia. Even entrepreneurs in demanding fields ensure they take time off for vacations and holidays, knowing that a rested mind is often the best dissertation help .

This gradual shift in academic culture reflects a broader trend towards work-life balance across all sectors. Instead of glorifying long hours and weekend work, there’s a growing recognition of the benefits of rest, flexibility, and mental health. The myth of the 24/7 PhD student is slowly eroding, paving the way for a more balanced, humanistic view of academic life that values researchers not just for their intellectual contributions, but also their wellbeing.

Follow us on Reddit for more insights and updates.

Comments (0)

Welcome to A*Help comments!

We’re all about debate and discussion at A*Help.

We value the diverse opinions of users, so you may find points of view that you don’t agree with. And that’s cool. However, there are certain things we’re not OK with: attempts to manipulate our data in any way, for example, or the posting of discriminative, offensive, hateful, or disparaging material.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

More from Student Life

Remember Me

Is English your native language ? Yes No

What is your profession ? Student Teacher Writer Other

Forgotten Password?

Username or Email

Loading metrics

Open Access

Ten simple rules to improve academic work–life balance

Contributed equally to this work with: Michael John Bartlett, Feyza Nur Arslan, Adriana Bankston, Sarvenaz Sarabipour

* E-mail: [email protected] (MJB); [email protected] (SS)

Affiliation Scion, Rotorua, New Zealand

Affiliation Institute of Science and Technology Austria, Klosterneuburg, Austria

Affiliation Future of Research, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, United States of America

Affiliation Institute for Computational Medicine and Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

- Michael John Bartlett,

- Feyza Nur Arslan,

- Adriana Bankston,

- Sarvenaz Sarabipour

Published: July 15, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009124

- Reader Comments

Citation: Bartlett MJ, Arslan FN, Bankston A, Sarabipour S (2021) Ten simple rules to improve academic work–life balance. PLoS Comput Biol 17(7): e1009124. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009124

Editor: Scott Markel, Dassault Systemes BIOVIA, UNITED STATES

Copyright: © 2021 Bartlett et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work was the product of volunteer time and the authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The ability to strike a perceived sense of balance between work and life represents a challenge for many in academic and research sectors around the world. Before major shifts in the nature of academic work occurred, academia was historically seen as a rewarding and comparatively low-stress working environment [ 1 ]. Academics today need to manage many tasks during a workweek. The current academic working environment often prioritizes productivity over well-being, with researchers working long days, on weekends, on and off campus, and largely alone, potentially on tasks that may not be impactful. Academics report less time for research due to increasing administrative burden and teaching loads [ 1 – 3 ]. This is further strained by competition for job and funding opportunities [ 4 , 5 ], leading to many researchers spending significant time on applications, which takes away time from other duties such as performing research and mentorship [ 1 , 2 ]. The current hypercompetitive culture is particularly impactful on early career researchers (ECRs) employed on short-term contracts and is a major driver behind the unsustainable working hours reported in research labs around the world, increases in burnout, and decline in satisfaction with work–life balance [ 6 – 10 ]. ECRs may also find themselves constrained by the culture and management style of their laboratory and principal investigator (PI) [ 11 – 12 ]. Work–life balance can be defined as an individual’s appraisal of how well they manage work- and nonwork-related obligations in ways that the individual is satisfied with both, while simultaneously maintaining their health and well-being [ 13 ]. Increasing hours at work can conflict with obligations outside of work, including but not limited to family care commitments, time with friends, time for self-care, and volunteering and community work. The increasing prevalence of technology that allows work to be out of the office can also exacerbate this conflict [ 14 , 15 ].

The academic system’s focus on publications and securing grant funding and academic positions instead of training, mentoring, and mental health has skewed the system negatively against prioritizing “The whole scientist” [ 5 , 16 ]. Research focused on the higher education sector has revealed that poor work–life balance can result in lower productivity and impact, stifled academic entrepreneurship, lower career satisfaction and success, lower organizational commitment, intention to leave academia, greater levels of burnout, fatigue and decreased social interactions, and poor physical and mental health, which has become increasingly prevalent among graduate students [ 1 , 17 – 22 ]. For instance, a recent international survey of over 2,000 university staff views on work–life balance found that many academics feel stressed and underpaid and struggle to fit in time for personal relationships and family around their ever-growing workloads [ 20 ]. These systemic issues are making it increasingly difficult to maintain an efficient, productive, and healthy research enterprise [ 23 ].

In the academic context, work–life balance needs to be examined with regard to spatial and temporal flexibility, employment practices, and employee habits. The need to improve work–life balance is recognized for researchers at all career stages [ 7 , 22 , 24 , 25 ]. While there is a growing literature providing specific strategies to cope with busy academic life [ 26 – 28 ], collating these disparate advice pieces into a coherent framework is a daunting task and few capture multifaceted advice by ECRs for ECRs. Departments and institutes need to contribute to improving research practices for academics at all levels on the career ladder [ 29 , 30 ]. PIs and mentors can promote healthier environments in their laboratories by respecting boundaries and providing individuals with greater autonomy over their own working schedule [ 11 , 12 , 31 – 33 ]. However, institutions do not typically prioritize work–life balance, leading to the loss of valuable talent in the research pipeline. The power dynamics within academia are evident now more than ever, with ECRs lacking agency at multiple time points and in controlling many aspects of their training. This may be especially true for trainees from underrepresented backgrounds, who face additional hurdles to their professional advancement in the current academic environment while attempting to maintain work–life balance. Furthermore, academia, in general, does not always value the aspects of a researcher’s job that the researcher finds important such as teaching, mentoring, and service. Thus, the experience of individual researchers regarding work–life balance will vary depending on multiple factors [ 34 – 39 ], including personal circumstances and satisfaction with aspects of life outside of work [ 40 ]. It is therefore unlikely that there is a “one size fits all” approach to effectively address work–life balance issues.

In order to support ECRs in maintaining work–life balance, institutions should support individualized strategies that are continually refined during their training. Here, drawing from our discussion as part of the 2019–2020 eLife Community Ambassador program and our experiences as ECRs, we examine the strategies individuals can adapt to strike a healthier balance between the demands of personal life and a career in research.

While many of the challenges junior academics face are systemic problems and will take a while to fix, some level of individual adjustment and planning may help ECRs more immediately and on an individual level. The rules presented here seek to empower ECRs to take action in improving their own well-being, while also providing a call to action for institutions to increase mechanisms of support for their trainees so they can thrive and move forward in their careers.

Rule 1: Long hours do not equal productive hours

One common reason for work–life imbalance is the feeling of lagging behind as a result of the present-day competitive nature of academia. This has led to incorrectly normalized practice of overwork, due to a sense of pressure from colleagues or ourselves, contributing to increasing mental health problems in academia [ 3 , 7 , 9 ]. On the other hand, keeping a balance sets one for higher productivity and creativity [ 41 ] and long-term satisfaction with work [ 17 , 18 ]. It is important to focus on the benefits of work–life balance on overall well-being and to accept that performing research and building a career in academia is a long process. Taking time off should not be associated with a feeling of guilt for not working at that moment. On the contrary, it should be seen as a necessity to have good health, energy, and motivation for the next return to work. A break can result in a boost to your productivity (rate of output) [ 42 ]. Studies show output of working hours to not increase linearly after a threshold and absence of a rest day to decrease output, as long hours result in errors and accidents, as well as fatigue, stress, and sickness [ 43 , 44 ]. It can be challenging to cut down on work hours when you feel that there is so much to get done. We also acknowledge that there are times when putting in long hours may be needed, for example, to meet a deadline; however, keeping this behavior constant might have more disadvantages than advantages in the long term.

Having flexibility in when and where you work can help you manage tasks and feel more balanced. It is important to discuss your needs with people at work and at home, in order to establish expectations and fit your lifestyle.

Rule 2: Examine your options for flexible work practices

Examine your relationship with your work, and try alternative schedules. Review your expected obligations, employer work hour rules, and offered benefits. Where possible, make use of modernization of work tools (such as remote work methods using digital technologies); working time is no longer exclusively based on in-person presence at the workplace, but rather the accomplishment of tasks [ 45 , 46 ]. The virtual office aspect can offer extensive flexibility in terms of time and location of work, reduce time spent traveling and commuting, and allow easier management of schedules and lives. Attending conferences online and giving invited talks, seminars, and interviews virtually can reduce fatigue and increase the time available for activities essential for your well-being [ 47 , 48 ]. Working remotely may not work for all or on many days of a week, but an overall reduction in travel is possible. In some instances, it may be difficult to know beforehand how much time you will be allocating to particular tasks in your new job, also some tasks such as fieldwork or labwork cannot be done remotely. Factor in workplace flexibility policies when looking at employment options and negotiating contracts. At the interview stage, ask your employer and prospective supervisor about flexible hours, options such as compressed workweeks, job sharing, telecommuting, or other scheduling flexibility to work in a way that best fits your efficiency and productivity. The more control you have over where and when you work, the less stressed you are likely to be. Once you know the options available to you, agree on a schedule based on your expectations and needs. Clear agreements on how and when to work are necessary to avoid conflict between work and nonwork obligations [ 45 ], so it is important to effectively communicate agreements with your managers, mentors [ 31 ], supervisors, colleagues, and also with your family. Having said this, in reality, ECRs may not always be able to negotiate salaries and benefits as conditions might be predetermined by an institution, a fellowship, or a PI’s strict expectations. Weigh the pros and cons of nonnegotiable job offers carefully. Remember that some constraints might be relaxed over time as your new employers build trust in you; therefore, continue the communication to find the best arrangements for your work.

As you try to reduce overworking and be more flexible with working arrangements, you will need to be very focused within the time frame that you have available. This is especially important as work–life balance boundaries become blurred if working from home. Setting boundaries is critical to success, as detailed below.

Rule 3: Set boundaries to establish your workplace and time

Setting spatial and temporal boundaries around your work is important for focusing on the task in hand and preventing work from taking over other parts of your life. When you are in the office and need to focus, make sure you can work in a quiet place where colleagues are unlikely to distract you. If you work in a shared office space, communicate with those around you to let them know your needs, or if you need complete silence, then consider working in a designated space for focused work. While working from home, some may struggle to disconnect from work, step away from screens, and set clear boundaries between digital and physical settings. Screen time needs to be managed so that remote workers do not blur the lines of work and life, as that can result in discouragement and burnout. Ask your coworkers to not demand your attention toward work after a certain time in the evening. Turn off email notifications outside of working hours. By setting boundaries, you will also set an example for your coworkers and mentees. When working at home, separating your workspaces from relaxation spaces can be helpful. This way, less clutter can decrease your stress levels, and a separated space can help you to draw a line between work and family. Even carving an area on a table dedicated to your work time can help with calm and work–life balance.

In order for your resulting work to be of high quality, diligence is key. In addition to being focused on your task, you should also establish a routine and prioritize your tasks, being able to then gain more control over your time. Learning to say no is also critical. Below we expand on these issues in the context of efficiency and productivity.

Rule 4: Commit to strategies that increase your efficiency and productivity

Many people use to-do lists and outline daily/weekly tasks, defining both work- and nonwork-related obligations that need to be accomplished. For nonwork responsibilities, devise a strategy with your family or those you live with to delegate tasks. Make sure responsibilities at home are clearly outlined and evenly distributed.

- Manage your time. Learning how to effectively manage your time and focus while at work is critical. Set a schedule to help in managing time, and do not forget to include buffer times between your plans, such as a coffee break with colleagues and a walk away from the bench or computer screen, to socialize and rest. Outside of busy periods, try to keep routines of work hours. Try time blocking, for example, check email and other social media (e.g., Slack) messages at specific times of the workday, and, if possible, arrange meetings at concentrated times during the day. This will maximize the amount of deep work that can be done during work hours. Sometimes, multitasking, for instance, running a few experiments at the same time or trying to work in between several meetings, may not result in great outcomes; have realistic plans and monotask if you find it better.

- Minimize decision fatigue. Decision fatigue refers to the deteriorating quality of decisions made by an individual after a long session of decision-making. Decision fatigue depletes self-control, which results in emotional stress, underachievement, lack of persistence, and even failures of task performance [ 49 ]. To reduce this, make the most important decisions first in your workday, and limit and simplify your choices.

- Collaborate. Workplace and home collaborations can take some of the load off and help in managing stress. Adjusting to teamwork or training a student may seem like extra commitments at the beginning, but, in the long run, they can help delegate some of the tasks on your calendar and help maintain a better work–life balance.

- Do not overcommit. Learn to say “no” [ 46 ]. Consider that accepting extra, low-impact tasks will sacrifice your nonwork time and may also take attention off your other important work appointments. Try to drop activities that drain your energy, such as nonessential meetings that do not enhance your life or career, and be efficient within this limited time with set goals.

- Discover your own strategies. Try to figure out what strategies work for you, and apply these to your life. Individuals respond differently to time of the day, physical conditions, and stress. Productivity may come with creative arrangements, and a high degree of organization may not work for everyone. Sometimes, improvisation and flexible schedules might be what you need.

As you begin to make decisions about the best way to manage your time, being strategic is key to prioritizing. You should aim to review your strategy and ability to stick to it often.

Rule 5: Have a long-term strategy to help with prioritization, and review it regularly

Having a long-term strategy that considers what you want to achieve and the timelines needed to get there can help with prioritization and deciding what to take on and what to say no to. This not only includes goals linked to your research career but also what is important to you outside of work, whatever this may be. When managing your work and nonwork tasks, see how well they align with your short- and long-term goals when you are deciding on the time and energy you need to allocate to attain them. With daily tasks, starting each day with the most important task, allocating the most productive hours to important tasks, as well as grouping similar tasks might help increase productivity and efficiency. A long-term look can help justify time spent on particular tasks, such as learning new skills, which might be taking extra time now but would help reduce stress in the long term. It is important to review your strategic goals and how well you are doing regularly, updating your strategy as needed. Consider using weekly time management charts to assess your task delegation retrospectively ( Fig 1 ). Have you been able to reach the goals you set? Did your time get taken up by other tasks? Did you use additional time to meet work goals at the expense of priorities outside of work? Are the goals you have set realistic and achievable, or do you need to make adjustments? If this appears overwhelming remember that your plans do not necessarily need to be detailed, simply keeping track of the hours spent working can be useful [ 26 ]. It is normal for priorities to change over time. Choose mentors that can help you achieve your short- and long-term goals, and consult with them regularly on your work–life balance strategies [ 31 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Dynamic, prospective, or retrospective weekly or monthly time management assessment charts can help researchers with improving their work–life balance by determining exactly how they spend their time. There are 164 hours in a week. Example hour allocation is shown here for academics across career stages [ 50 ]. Hours allocated will vary depending on the researcher’s disciplines (for instance, humanities versus life sciences or engineering) and circumstances such as end or beginning of semester, when approaching a deadline, or when a committee is busiest. Teaching responsibilities include course instruction and administration, including grading and evaluation. Family time includes interacting, dining, and performing housekeeping chores with family members. Research activities include performing research and literature review time. External service may include manuscript or grant reviewing and editorial tasks. Meetings may include lab/group meetings, departmental faculty meetings, or other council meetings. Self-care activities may include attending to one’s hobbies. Internal service includes department and university service. Weekends and public holidays are included in the weeks. Other tasks not included in this chart may be professional development, writing letters of recommendation, advising undergraduate students, faculty and student hiring/recruitment, marketing/public relations, fundraising, phone calls, reception/dinner, commute/travel, scheduling/planning, and reporting. ECR, early career researcher; MLCR, mid- to later career researcher; PI, principal investigator. Figure created using ggplot library in R [ 51 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009124.g001

In order to do your best in life and work, you need to put yourself first. You can do that by paying attention to your eating and sleeping schedule and engaging in activities that will keep you physically healthy and stimulate your mind.

Rule 6: Make your health a priority

You are not only defined by your work. Spending time on self-care and relaxation is a necessity in life to maintain a healthy body and mind, leading to a fulfilling lifestyle. This, in turn, will enable you to achieve peak performance and productivity in the workspace.

- Eat a healthy diet. A balanced diet with emphasis on fresh fruits, vegetables, and lean protein enhances the ability to retain knowledge as well as stamina and well-being. An option could be keeping fruit baskets in your office with your colleagues.

- Get enough sleep. Lack of sleep increases stress, and associated fatigue is linked to poor work–life balance [ 52 ]. One potential way to improve sleep quality is to avoid using personal electronic devices, such as smartphones and tablets, during your personal and other nonwork times, particularly right before going to sleep as screen time is associated with less and poorer quality rest [ 53 , 54 ].

- Prioritize your physical and mental health. Set time aside for individual or group physical activities of your choice. Schedule specific times for social activities and exercise to unwind, by arranging ahead of time with others or signing up to regular classes, making the plans harder to cancel. Using the gym at your workplace during a break can freshen you. Or you can bike or jog to work if safe to have some daily exercise. Equally important is dedicated time for your mental health. Reading a book, listening to music, gardening, many other activities, or if you prefer, regularly talking to a therapist could help you disengage from work, enjoy other aspects of life, rest, process, and recharge.

- Try meditation or mindfulness exercises. Meditation can reduce stress and increase productivity [ 29 ]; it will help you focus your thoughts and develop more self-awareness. If you are aware of when and why you are stressed or exhausted, these feelings become a trigger for you to lean into a boundary such as taking a screen break, going for a walk, or simply resting your eyes for 15 minutes before jumping back into a task or meeting. You can do meditation or yoga at home for short intervals. Do what is realistic for your life at the time and what helps you along.

- Make time for your hobbies and relaxation. Set aside time each day for an activity that you enjoy [ 28 , 55 , 56 ]. Discover activities you can do with your partner, family, or friends—such as hiking, dancing, or taking cooking classes. Listen to your favorite music at work to foster concentration, reduce stress and anxiety, and stimulate creativity [ 57 ].

While your work is important, you will be much happier if you schedule some social time into your week. This is a simple need, and methods vary from person to person, but the common goal is to increase your sense of connection and belonging, satisfaction with life, and/or energy.

Rule 7: Regularly interact with family and friends

Your work schedule does not need to lead to loss of your personal relationships. Scheduling time off to meet in-person or interact online with your loved ones in advance will make it harder to cancel plans in favor of working longer. As an example of good practice, most parents, even in academia, need to schedule their time around family responsibilities, which actually obliges them to maintain a work–life balance; they typically do not overstay at work every day, take the weekends off, and use annual leave. Meeting with friends and family will provide a chance to reconnect with them and your shared values. If you live in a country different from your family and friends, it is important to keep in touch using online audiovisual call and chat technologies. Other ways to relax include taking walks with loved ones, being out in nature, or playing board games. Social downtime can help replenish a person’s attention and motivation, encourages productivity and creativity, and is essential to both achieve our highest levels of performance and form stable memories in everyday life [ 58 ].

In addition to spending time for yourself and with family and friends, engaging in activities that are important to you, even when these activities are demanding, can bring a needed sense of achievement and satisfaction.

Rule 8: Make time for volunteer work or similar commitments that are important and meaningful to you

Many find additional engagements outside of their day to day jobs both important and rewarding. These activities would not be considered hobbies or relaxation, examples may include volunteering for the local community (e.g., at pet shelters, food banks, and environmental efforts), regional and online communities (e.g., student advocacy groups), time on boards or committees outside of work (e.g., acting as treasurer or secretary of a club), and learning a new language when you have moved to a new place. Many ECRs enjoy taking their work one step forward to volunteer with organizations focused on the societal value or impact of their work. This can help expand your perspective as an ECR working on a particular research topic, by understanding the broader picture of what you are working on and why and giving it a human impact dimension. Others may opt to volunteer in activities that are entirely independent of their research, which can provide opportunities to clear your mind for a good period of time and boost your mood. Although these activities add extra work to your schedule, if they are important to you, then you might find it difficult to find balance without the sense of achievement and reward they bring. However, when under pressure from work and home, finding time for these activities can be challenging—remember that work–life balance needs to be continually reassessed; consider taking a break if you need to and revisiting these extra commitments at a better time.

In addition to advisors and departments, institutions can take measures to support ECRs and provide them with necessary resources to thrive. They should also create a culture where asking for help is encouraged, and support for the well-being of researchers exists at their institution.

Rule 9: Seek out or help create peer and institutional support systems

Support systems are also critical to your success, and building more than one will increase your chances of success and balance overall [ 59 ]. At work, join forces with coworkers who can cover for you—and vice versa—when family conflicts arise. At home, enlist trusted friends and loved ones to pitch in with childcare or household responsibilities when you need to work overtime or travel. Seek support in academic communities and organizations who are working on mental health and well-being. For instance, PhD balance is a community space for academics to learn from shared experiences, to openly discuss and receive help for difficult situations, and to create resources and connect with others [ 60 ]. Dragonfly Mental Health, a nonprofit organization, strives to improve mental health care access and address the unhealthy culture pervading academia [ 61 ]. Everyone may need help from time to time. If life feels too chaotic to manage and you feel overwhelmed, talk with a professional, such as a counselor or other mental health provider. If your employer offers an employee assistance program, take advantage of available services. Joining a support and peer mentorship group, such as graduate, postdoctoral or faculty Slack communities [ 31 ], or working parents seeking and sharing work–life balance strategies, provides at least two key advantages: an opportunity to vent to people who truly understand your experiences and the ability to strategize with a group about how to improve your situation. A combination of these steps will help researchers to improve their work–life balance.

Finally, if your ability to effectively implement the advice in Rules 1 to 8 is constrained by the culture in your lab or pressure from the academic system, seek support from mentors, and advocate for yourself and for the change you would like to see.

Rule 10: Open a dialogue about the importance of work–life balance and advocate for systemic change

Spreading awareness and promoting good practice for managing work–life balance are essential toward shifting the prevailing culture away from current excellence at any cost practices. While major change is only likely to come about with a coordinated shift in the way that research laboratories, institutions, publishers, funders, and governments assess research endeavors at a broadscale, there is much that can be done at smaller scales to improve the culture at institutions and within labs [ 62 ]. Leverage the support of communities that empower ECRs to participate in advocating for the importance of mental well-being in academia through research and programs (see Rule 9). Discussions on work–life balance can also be initiated through seminars and courses. You can ask for, or if you plan to get more involved, organize workshops and training in your institute for ECRs. Another way to encourage collective work–life balance could be to host activities such as family and employee sports, outdoor movies, or picnic events encouraging family-friendly time and team building. Advocate for policies in your workplace that can help reduce conflict between work and other responsibilities, for example, childcare services or pet-friendly workspaces. To advocate at larger scales, you can join graduate/postdoctoral researcher associations, unions, or work councils to actively pursue work–life balance–friendly policies and employment contracts at institutes and through funding agencies. For instance, institutions and funding agencies that do not encourage the traditional gender roles allowing both men and women to take family leave, see better work–life balance, and reduced work–life conflict [ 63 , 64 ]. If the culture in your research lab constrains your ability to manage your work–life balance in a way you find satisfactory, shifting departmental and institutional attitudes and policies can put pressure on PIs to build a more supportive work culture via steps outlined elsewhere [ 11 , 12 , 31 – 33 ]. Although organizational culture cannot be changed overnight, changes in policy can go a long way in creating a culture that aids work–life balance in the academic workplace [ 62 – 64 ].

Conclusions

Most academic jobs come with flexible working hours, which can be advantageous when researchers attempt to balance the competing obligations in their lives. Yet, ECRs typically work significantly longer than the normal working hours of academic employment contracts [ 65 ]. How researchers spend their time has major impacts on their well-being, productivity, and professional scale of impact and those of their mentees, family, colleagues, and institutions in the short and long term. Academic culture has normalized and ignored overworking often at the expense of a social life, or of even greater concern, at the expense of researchers’ health and well-being. It is important for all academic researchers, institutions, and funding agencies to credit service and administrative activities, to acknowledge difficulties in satisfying work- and nonwork-related obligations in academic careers, and support diverse strategies to attain work–life balance [ 29 , 30 ]. It is imperative to examine work–life balance practices by ECRs, suggest improvements, and integrate these into employment and promotion offers. Here, we provided recommendations for ECRs to improve management of the balance between their professional and personal lives, but striking a healthy work–life balance is not a one-shot deal. Managing work–life balance is a continuous process as your family, interests, and work life change. Working long hours does not equate to working better. Regularly examine your priorities—and, if necessary, make changes—to ensure you stay on track. Ultimately, for the benefit of researchers and the important work that they do, both individuals and institutions need to make health and well-being a priority.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Inez Lam of Johns Hopkins University for valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We also thank the facilitators of the 2019–2020 eLife Community Ambassador program.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 16. The Whole Scientist: The Jackson Laboratory. Available from: https://www.jax.org/education-and-learning/education-calendar/2020/11-november/the-whole-scientist-bh

- 20. Bothwell E. Work-life balance survey 2018: long hours take their toll on academics. In: Times Higher Education [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/work-life-balance-survey-2018-long-hours-take-their-toll-academics

- 23. Loissel E, Deathridge J, King SRF, Pérez Valle H, Rodgers PA. Mental Health in Academia. In: collection by eLife [Internet]. eLife. Sciences Publications Limited; 23 Oct 2019 [cited 2020 Jul 21]. Available from: https://elifesciences.org/collections/ad8125f3/mental-health-in-academia https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.52881 pmid:31642808

- 45. Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Making the right moves: a practical guide to scientifıc management for postdocs and new faculty. 2nd ed. 2019. Available from: https://www.hhmi.org/sites/default/files/Educational%20Materials/Lab%20Management/Making%20the%20Right%20Moves/moves2.pdf

- 50. Ziker J. The Long, Lonely Job of Homo Academicus. In: Boise State University [Internet]. 31 Mar 2014 [cited 2020 Oct 18]. Available from: https://www.boisestate.edu/bluereview/faculty-time-allocation/

- 51. Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. 2016. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=XgFkDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR8&ots=spY07U8X3P&sig=Vw5aHFonM3Ee56OTEuWCfgUXA-c#v=onepage&q&f=false

- 58. Jabr F. Why Your Brain Needs More Downtime. In: Scientific American [Internet]. 15 Oct 2013 [cited 2020 Jul 8]. Available from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mental-downtime/

- 59. Supporting the Whole Student: Mental Health and Well-Being in STEMM Undergraduate and Graduate Education. In: The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2020 Jul 6]. Available from: https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/projectview.aspx?key=51350

- 60. PhD Balance: A community empowering graduate students. 2020 [cited 2020 May 29]. Available from: https://www.phdbalance.com/

- 61. Dragonfly Mental Health. [cited 2020 May 29]. Available from: http://dragonflymentalhealth.com/about-us/

Maintaining Work-Life Balance During a PhD

- Katie Baker

- July 31, 2024

After the painstaking process of drafting your research proposal, finding the best university to suit your research needs and enduring the anxiety of the application process, you’re finally a doctoral student staring down the barrel of a multi-year academic marathon.

Many new PhD students make the mistake of treating it as more of a sprint when they embark on their PhD journey, which can last up to four years for full-time students or seven years for part-time students and become overwhelmed, which highlights the importance of keeping a healthy pace, not jumping the gun, and maintaining a healthy work-life balance.

This article will highlight the necessity of ensuring you’re not burning the candle at both ends, provide actionable tips to avoid burnout and offer support suggestions if you feel you can’t cope with the pressures of your academic life. It is important to remember that there is no one-size-fits-all answer on how you should approach your daily, weekly, or even annual schedule. You may find that in the beginning, it is a process of trial and error as you figure out the most effective and productive routine to make the process less of a chore and more of a gratifying pursuit.

The Importance of Maintaining Work-Life Balance During a PhD

Many PhD students struggle to find the balance between academic success and overall well-being, as PhD programs offer degrees of flexibility which are scarcely seen in other walks of academic life.

Unlike taught degrees, with PhDs, there are no lectures, seminars, exams, or essays to plan academic life around; this relative freedom can often lead to blurred lines between work and life and students feeling as though they’re not progressing at the pace they should be as there is still mountains of work to be done by the time you submit your thesis.

Though it is hard to strike an optimal balance between life’s demands, it isn’t impossible to achieve and maintain a healthy work-life balance by setting boundaries, finding effective ways to manage stress and prioritising.

How to Maintain a Work-Life Balance During a PhD

How to Set Work-Life Boundaries

Even if your PhD is your number one priority, it is crucial to set boundaries between your academic and your personal life. Your weekly schedule should always make time for friends and family, engaging in hobbies and taking regular breaks. To set clear boundaries and ensure your time as a PhD student is rewarding, set aside time to focus on your well-being between your study and writing sessions.

Discover Why Prioritisation Is Key

Maintaining a work-life balance during a PhD is more than time management; it is also about managing energy and nurturing the mind as your knowledge advances. You can’t pour from an empty intellectual cup; even if grabbing a coffee with your friends, heading to the gym, or practising mindfulness meditation doesn’t get more words on a page or help you to make a breakthrough with your research, it can be beneficial in the long run. When creating a prioritised schedule, allocate specific blocks of time to your academic tasks and personal activities.

Set Aside Time for Stress Management

During your time as a PhD student, it is crucial to remind yourself that self-care isn’t a luxury; it is a necessity which keeps you orientated towards laying a foundation of good mental and physical health. Whichever stress management technique works for you and provides you with the most respite, always make time for it within your weekly routine. Whether it is venting to your friends, going for a walk, or taking the time to listen to your body and mind before responding with kindness during mindfulness meditation, ensure you have enough stress-eliminating activities in your diary. Never skip on the self-care fundamentals by ensuring you get enough sleep and exercise, and that you follow a diet which gives you the mental energy to tackle your academic workload.

Change Your Perception of Productivity

If you solely measure productivity in terms of work output, you may want to rethink how you perceive productivity, as it is so much more than a measure of hours at the helm; it is about navigating your tasks and schedule with maximum efficiency. A great way to ensure optimal efficiency is by using techniques, such as the Pomodoro Technique, which recommends following 25-minute stints of work with a five-minute break. You might also want to try setting realistic goals and coming up with rewarding ways to celebrate reaching them. This will boost your morale and anchor a sense of achievement.

Know the Signs of Burnout and How to Counteract Them

The most common signs of burnout include feelings of reduced accomplishment, cynicism, irritability, exhaustion, detachment, feeling overwhelmed or fuelled with self-doubt and being more prone to procrastination. In minor cases of burnout, providing enough time for replenishing leisure activities is usually enough to counter the warning signs. In more severe cases of burnout, which leaves you feeling you can’t cope with the stress, communicate this with your PhD supervisor or seek mental health support.

How and When to Seek Help

In 2021, Nature Journal announced anxiety and depression are ‘the norm’ for UK PhD students. In the same year, a band of UK universities, including the University of Sussex, revealed that 42% of PhD students surveyed self-reported mental health issues . Rather than accepting poor mental health as par for the course, it is crucial for students to seek support. Whether that be from a UK counselling service or one of the numerous helplines and organisations dedicated to supporting students.

If you need help cultivating a lifestyle which facilitates academic success without compromising your health or happiness, reach out to your university’s support services, such as wellness programmes or student counselling. Additionally, the charity Student Minds and The National Union of Students (NUS) offer guidance and advice, which is tailor-made for postgraduate students. The British Psychological Society also provides avenues for support for students looking to maintain their mental health during their doctoral studies.

Final Thoughts

By valuing self-care, knowing your limits when it comes to staying productive without overexerting yourself and ensuring there is enough time for rest, relaxation, socialising, and other enjoyable pursuits which leave you energised and academically inspired, it is entirely possible to negate the PhD process with your well-being intact. Always remember that researching and writing your PhD is a journey, it is not just about the destination, as much as your eye wants to remain on the doctoral title prize.

You might also like

The Best London Boroughs for Home Study

Students have much to consider when viewing and moving into their student accommodation. As well as the feel of the home, it is important to

Undergraduate degree vs postgraduate degree: key differences

Going to university and choosing the right educational path are likely going to be some of the most important decisions in your life. This means

Do You Get Paid for a PhD?

Do You Get Paid for a PhD? For many students who don’t have the luxury of never worrying about money, one of the main considerations

Enquire with us

We are here to help and to make your journey to UWS London as smooth as possible. Please use the relevant button below to enquiry about a course you would like to apply, or to clarify any questions you may have about us and our admission’s process. After you submit your enquiry, one of our advisers will get back to you as soon as possible.

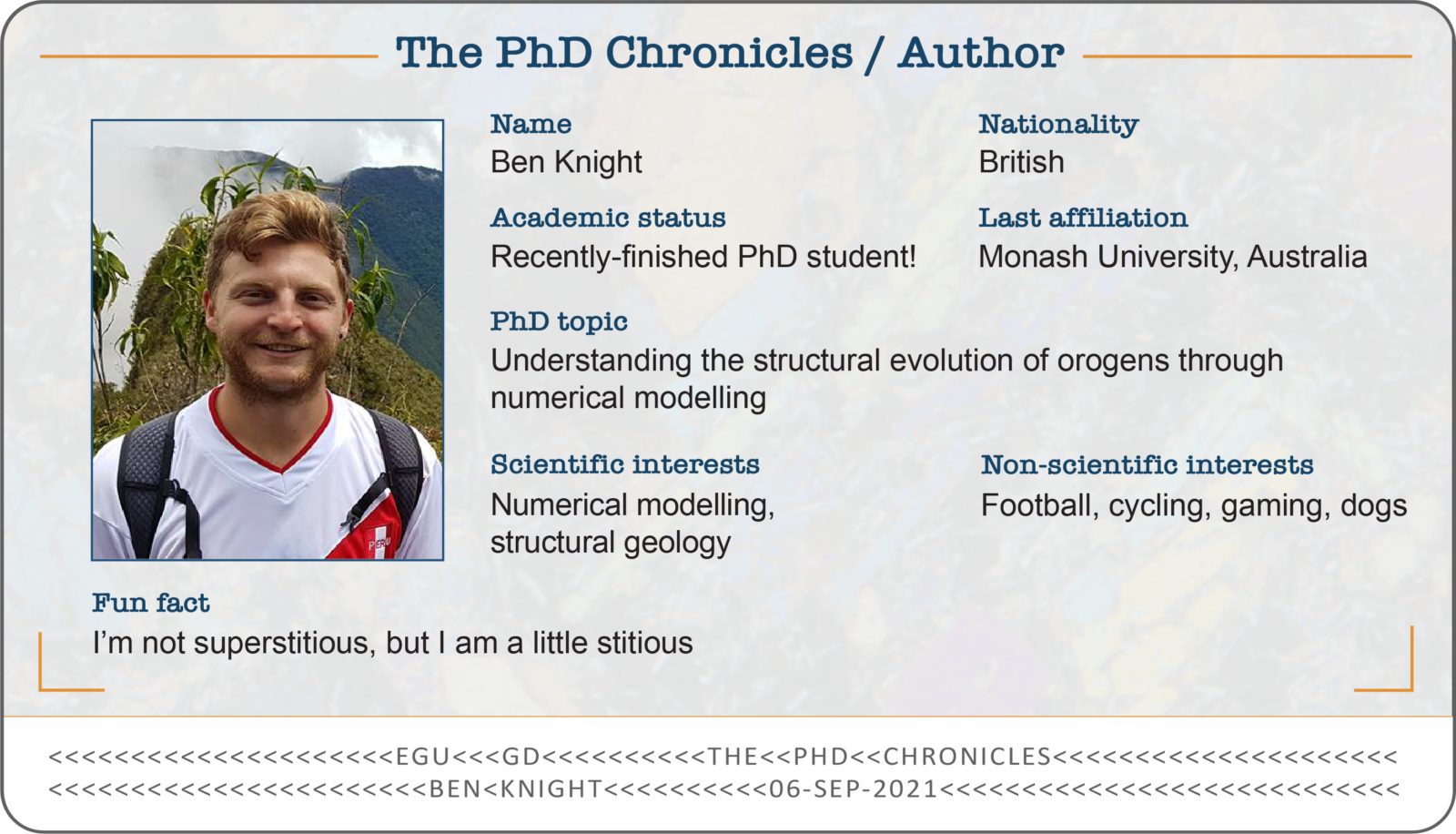

Finding the work-life balance of a PhD

When constant studying started taking a toll on phd student vijay victor’s physical health, he realised he needed to create a better work-life balance.

Vijay Victor

When I decided to do my PhD abroad in Hungary I had a clear idea in mind about my research plan. I started publishing papers even before getting into doctoral school, laying the foundations for my research topic. I published papers in well-indexed journals, exceeding the requirements of our doctoral school in the first four semesters of my PhD – after all, they say hard work pays off.

But sometimes too much hard work can be damaging. Somewhere in this journey, I lost myself in my research.

Being an introvert it was instinctive to me to make excuses to avoid social events, and my hectic workload helped me avoid socialising without any guilt. The graduate life abroad is confined mostly to one’s own room, despite what all the Instagrammed parties and glamorous nights out would have you think.

Occasionally I went swimming with a few close friends, which was the only active exercise I did, and I also loved going for a long walk in the countryside.

But when I had deadlines, I did nothing other than study for days. I think on average I spent 10-12 hours a day studying, reading and writing without even realising it.

There were even times when I felt a sneaky happiness on Friday evenings as I was faced with two whole days to work on my papers without disturbances.

I only realised that I was overworking myself when my body started to respond. My fitness tracker warned me that my average sleeping time of 5 hours 30 minutes was not good enough.

I started getting migraines and they became more frequent. And then I started to have gut problems. This was when I knew I needed to take a break.

I went home after seeking permission from my supervisor (she was very kind and helpful) and got myself thoroughly checked by a physician. After an endoscopy and some blood tests I was told that I had developed a functional gastrointestinal disorder. Fortunately it was at the beginning stage and there was nothing much to worry about.

Some of my friends doing PhDs shared similar stories of health problems. It was bittersweet to know I wasn’t the only one. I had already read about the anxiety and depression issues which graduate students experience, however this was a new revelation to me. To my surprise, in a random Google search at least 10 research studies appeared confirming the relationship between academic stress and gut problems.

Tips for writing a convincing thesis

Research life is entirely different to undergraduate life. My research area is in the field of economics, so I only need my laptop and a quiet space to work and so I do not get the chance to meet colleagues on a daily basis. When the deadlines are so close, stocking fridges and spending days in your room is a story which is familiar to many in grad schools. And often, when you work on more than one paper simultaneously, you have no time for a proper break.

Even after you submit you will have to deal with reviewers comments and corrections. So you have to revise your piece numerous times in order to either get it accepted – which further increases the motivation to write new papers – or it’s rejected, which is upsetting and followed by desperate attempts of trying again. Either way, you are back to square one with a new paper.

Writing research papers is often a tedious, bleak and time consuming process. Sometimes despite the best efforts, you might only have typed two or three paragraphs by the end of the day. This at times could also create a delusion that you are not putting in enough effort.

Some scholars seem to be unable to identify the fine line between a normal and an overwhelming work schedule.

Often we realise too late that it is important to strive for balance first, before aiming for perfection. As my supervisor always says, “there is no finished work in research”. Being a researcher is a lifetime contract and only by making it a part of a healthy lifestyle can one sustain and excel in it.

Read more: What is a PhD? Advice for PhD students

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

PhDLife Blog

Sharing PhD experiences across the University of Warwick and beyond

Adding pauses in your PhD

As with anything, the key to a healthy PhD is an effective work-life balance. It is important to take pauses and breaks during your PhD to avoid burnout and so that you can enjoy what you do rather than viewing it as a liability. Manpreet Kaur discusses how she sprinkles breaks in her weeks and months.

First published on June 23rd, 2021.

I have seen a lot of things on social media about research culture and what does and does not count as good and healthy work-life balance. I definitely imagined myself as one of those PhD students who would completely immerse themselves in their projects. However, I’m slowly realising there is quite a steep learning curve, especially considering that I switched from polymer chemistry to electrochemistry.

Therefore, perhaps my love for my project is looking less like the ‘love at first sight’ of Snow White and more like the slowly developing one of Belle. As I slowly get to grips with the project, I find I enjoy it all the more. But six months into my PhD, I have learnt that there is no set formula to acing the work-life balance. It is all about doing what works for you. So I’ll list some of my strategies here on how to add pauses in your PhD.

Role models

My two big research role models will be the PhD student I worked with during my masters and my current PhD supervisor. Both are very much focussed on doing science because it is fun and exciting to find out new things and both are driven by that enthusiasm rather than by targets of spending 10 hours in the lab every day. I think it is so helpful to find such mentors/role models early on who can help you understand where you are and how you’re doing.

Task-based learning

I keep a notebook to write all my tasks I need to do. For every day, I’ll plan in the morning what I want to achieve that day (realistically) and work towards that rather than aiming to come in at 10 and not leaving before 6pm etc. Whether it be experiments I need to run, plan or literature searches, I have all those listed as tasks and try to work to finish them. Sometimes, other things come up during the day that I add to the list after completing them just so I can experience the satisfaction of ticking off another task, but also it means that if I fail to do everything on my list, I know why. That way, I don’t beat myself up about it as I keep track of it all.

Is research 9 to 5?

This is interesting. I wanted to keep it 9 to 5. In the evenings I like reading or painting vignettes or watching comedy on the iPlayer. But I think research is not 9 to 5. Sometimes the book I pick up in the evenings is called ‘Electrode potentials’ and I read it because it is fun. Sometimes, there are papers I read on weekends because I want to. Sometimes, I finish my day at 4pm, wrap up, go home and make a nice curry. I plan my tasks but not my time. I like to keep it a bit spontaneous and make sure I do things not out of a sense of necessity but because I want to and then it means I enjoy it. So, be driven by mood rather than a feeling of ‘I have to’. The best time to take a break is when you think you need to.

Taking time off

My first week of holidays I took off was around Easter, immediately after the Easter shutdown. My siblings had end of term holidays so I had a good two weeks with them to enjoy. We were working on a book chapter in the group at the time, and while the brain said to take time off after the book chapter was sent off (at the end of May), the heart wanted time off in April. I spoke to my supervisor and she had no problem with me taking time off, so off I went home for a fortnight in the middle of a task leaving it all there, signing out of Teams and Outlook and painting and watching Shaun the Sheep episodes with my siblings. It felt radical, but it was pure joy. When I came back, it was a refreshing start and it meant that I once again I felt like I had the energy to read about the material we were writing on. So, there is no ‘right’ time to take time off, in my honest opinion, or you shouldn’t feel the need to wait for a ‘chapter’ or task to end before you take a break. Sometimes, moving away from something and then returning to it can mean we are more productive.

These are some of my strategies. Overall, do what makes you happy and hopefully your research project makes it somewhere on your happy list and then it’s all good. Side note, I’m reading My Kind of Happy by Cathy Bramley. Picked up this book from the supermarket and am absolutely loving it. It is also about a happy list so maybe treat yourself if you want to explore this more?

How do you like to plan breaks in your research? What works best for you? Tweet us at @ResearchEx , email us at [email protected], or leave a comment below.

by Manpreet

Manpreet Kaur is a first year PhD student in the Department of Chemistry. She has been at Warwick since 2016, and did her BSc and MRes here. Her research project focuses on the design of photoelectrocatalytic systems for the synthesis of nitrogen containing compounds. You can follow her on Twitter here and further details about her project and background can be found here .

Share this:

Comments are closed.

Want the latest PhD Life posts direct to your inbox? Subscribe below.

Type your email…

Blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

As a PhD student, I want to limit myself to 40 hrs/week. How to maintain this boundary?

So I am considering a PhD position as it appears one opened up and I was contacted about it by a professor. I'm not desperate to get a PhD. I think it's a nice goal and I am interested in the subject but its completion is not something I am dead set on.

I have read some horror stories about hours worked which I refuse to fall into. I plan on documenting my hours worked and limit it to about 9-5, mon-fri, basically view it as a very poorly paying industry job while maintaining time for personal projects/startup ideas.

So my question is if my advisor starts to get pushy and demand I spend more time working, what's the best way to respectfully maintain my boundaries?

I figure the worst that could happen is my advisor cuts my funding at which point I would terminate. Practically speaking my MS is complete so besides giving me a bad reference there's not a ton that could be done to me.

- work-life-balance

- 6 Many people draw conclusions out of your post like "I am not dedicated to research", "I will under no circumstances work longer then 8 hours", "as soon as I find something better, I will go". Can you comment on them how true or false they are? Also, which country do you want to do the phd in? – user111388 Commented Jul 12, 2020 at 11:23

- 2 My interest in completing the PhD is dependent with how much benefit I gain from it vs doing something else which depends on opportunities available at the given time. Again I think it's a nice goal, probably worth trying but I will continue to also spend time on other things. I live in the US. – FourierFlux Commented Jul 12, 2020 at 15:50

- 6 The best weeks of grad school were the ones where I worked 80 hours because I couldn't stop thinking about the fascinating problem I was solving. I'd wake up in the night with a new idea and start working on it then. Of course, not every week can be that way. – David Ketcheson Commented Jul 13, 2020 at 12:34

- 7 A PhD is an exercise in personal development. If you treat it like a job you can leave at the office, you're only really cheating yourself. You're right that the pay is poor - because the dividends are paid in experience. People work hard at a PhD because you have a limited window of opportunity to make the most of your time there. If you're planning to just treat this like a job, I'd seriously consider just getting a normal job. The pay is better and you don't seem terribly interested in taking advantage of the non-financial incentives that make the PhD worthwhile. – J... Commented Jul 13, 2020 at 12:54

- 3 I strongly disagree that wanting to keep regular hours is missing the point of a PhD. I would actually say the opposite: failing to set boundaries around work during your PhD is a great way to ruin your mental and physical health, can make you susceptible to workplace abuse, and, ironically, will probably make you less productive. I would recommend that OP look into Cal Newport's blog posts on "fixed-schedule productivity" which address this exact issue in the context of graduate school. – Patrick B. Commented Aug 10, 2020 at 19:33

13 Answers 13

First of all, I know many PhD students (also myself) who did exactly that and finished their phd: They worked 40 hours a week (or less), had a "normal life" , knew they would go to industry afterwards and wanted to learn/do research before (and stay connected to the system "university") because they loved uni/studying. It helps that in my country, studying and also titles are traditionally seen as something valuable (so there is no feeling of "only study if this aids you in your future job" in my country). Some students also saw it as a fun experience to live abroad before returning home. For me, it was similar: I didn't want to become a researcher because for me the postdoc life seems horrible -- but one can do a phd realtively risk-free. (Now I teach at university).

It is certainly not possible to work only 40h with all profs/in all subjects. Maybe also not in all countries (in which one do you want to study?) Probably it is also not possible with the most famous universities/professors.

I do recommend you to do good research on your prof what kind of person they are. Is it possible to do this kind of work with them or not?

I do think your attitude "I am not dead set on completing" is great. If the prof makes unreasonable demands (or other things like misconduct), just go. When they suggest longer working hours, tell them you don't want to do this unless absolutely necessary, if they keep insisting, just go. Do keep your eyes open while doing the phd for skills you need in industry.

Note that there are even (incredible) people who finish a PhD and have little kids (and some of them, no partner!)

(Of course, you might have two fewer papers afterwards for a good university career, but as this doesn't seem to be your goal..)

- 32 +1, though I would strengthen "do good research on your prof" to "explicitly discuss expectations and goals with the prof before accepting the position." – cag51 ♦ Commented Jul 10, 2020 at 17:54

- Bear in mind that this "just go" ultimatum is equally likely to be wielded against you. PIs are used to being able to hold completion (and future career / network) over their PhDs, so you will need to mean it when you say this won't work on you – benxyzzy Commented Jul 11, 2020 at 11:38

- 4 @benxyzzy: Yes. But if the professor says "do this bad thing or I kick you out" it is better not work with them. – user111388 Commented Jul 11, 2020 at 13:23

- 5 This is almost word for word what I intended to reply. I was in that exact situation, had great fun with my PhD, had great fun with my friends partying hard, had great fun with my girlfriend to the point of marrying her and had a great time working for a company by the end of my PhD (which lengthened it by a year or so). I left academia after that (a mixture of not wanting to work in a feudal system, attraction to industry and willingness to quit at the top of the fun and to have only great, fondling memories of that extraordinary time in my life) – WoJ Commented Jul 11, 2020 at 14:39