Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

How to Format A College Essay: 15 Expert Tips

College Essays

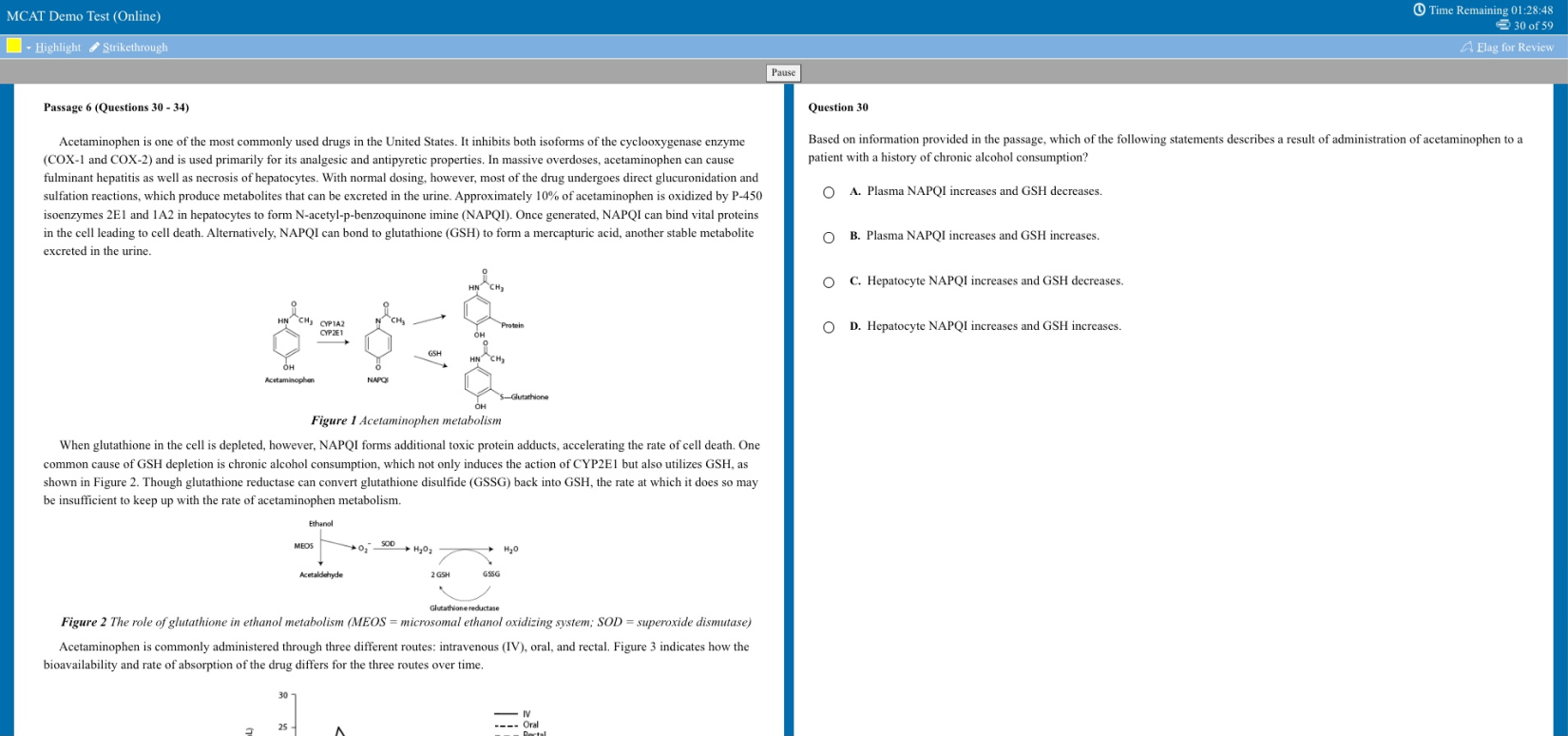

When you're applying to college, even small decisions can feel high-stakes. This is especially true for the college essay, which often feels like the most personal part of the application. You may agonize over your college application essay format: the font, the margins, even the file format. Or maybe you're agonizing over how to organize your thoughts overall. Should you use a narrative structure? Five paragraphs?

In this comprehensive guide, we'll go over the ins and outs of how to format a college essay on both the micro and macro levels. We'll discuss minor formatting issues like headings and fonts, then discuss broad formatting concerns like whether or not to use a five-paragraph essay, and if you should use a college essay template.

How to Format a College Essay: Font, Margins, Etc.

Some of your formatting concerns will depend on whether you will be cutting and pasting your essay into a text box on an online application form or attaching a formatted document. If you aren't sure which you'll need to do, check the application instructions. Note that the Common Application does currently require you to copy and paste your essay into a text box.

Most schools also allow you to send in a paper application, which theoretically gives you increased control over your essay formatting. However, I generally don't advise sending in a paper application (unless you have no other option) for a couple of reasons:

Most schools state that they prefer to receive online applications. While it typically won't affect your chances of admission, it is wise to comply with institutional preferences in the college application process where possible. It tends to make the whole process go much more smoothly.

Paper applications can get lost in the mail. Certainly there can also be problems with online applications, but you'll be aware of the problem much sooner than if your paper application gets diverted somehow and then mailed back to you. By contrast, online applications let you be confident that your materials were received.

Regardless of how you will end up submitting your essay, you should draft it in a word processor. This will help you keep track of word count, let you use spell check, and so on.

Next, I'll go over some of the concerns you might have about the correct college essay application format, whether you're copying and pasting into a text box or attaching a document, plus a few tips that apply either way.

Formatting Guidelines That Apply No Matter How You End Up Submitting the Essay:

Unless it's specifically requested, you don't need a title. It will just eat into your word count.

Avoid cutesy, overly colloquial formatting choices like ALL CAPS or ~unnecessary symbols~ or, heaven forbid, emoji and #hashtags. Your college essay should be professional, and anything too cutesy or casual will come off as immature.

Mmm, delicious essay...I mean sandwich.

Why College Essay Templates Are a Bad Idea

You might see college essay templates online that offer guidelines on how to structure your essay and what to say in each paragraph. I strongly advise against using a template. It will make your essay sound canned and bland—two of the worst things a college essay can be. It's much better to think about what you want to say, and then talk through how to best structure it with someone else and/or make your own practice outlines before you sit down to write.

You can also find tons of successful sample essays online. Looking at these to get an idea of different styles and topics is fine, but again, I don't advise closely patterning your essay after a sample essay. You will do the best if your essay really reflects your own original voice and the experiences that are most meaningful to you.

College Application Essay Format: Key Takeaways

There are two levels of formatting you might be worried about: the micro (fonts, headings, margins, etc) and the macro (the overall structure of your essay).

Tips for the micro level of your college application essay format:

- Always draft your essay in a word processing software, even if you'll be copy-and-pasting it over into a text box.

- If you are copy-and-pasting it into a text box, make sure your formatting transfers properly, your paragraphs are clearly delineated, and your essay isn't cut off.

- If you are attaching a document, make sure your font is easily readable, your margins are standard 1-inch, your essay is 1.5 or double-spaced, and your file format is compatible with the application specs.

- There's no need for a title unless otherwise specified—it will just eat into your word count.

Tips for the macro level of your college application essay format :

- There is no super-secret college essay format that will guarantee success.

- In terms of structure, it's most important that you have an introduction that makes it clear where you're going and a conclusion that wraps up with a main point. For the middle of your essay, you have lots of freedom, just so long as it flows logically!

- I advise against using an essay template, as it will make your essay sound stilted and unoriginal.

Plus, if you use a college essay template, how will you get rid of these medieval weirdos?

What's Next?

Still feeling lost? Check out our total guide to the personal statement , or see our step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay .

If you're not sure where to start, consider these tips for attention-grabbing first sentences to college essays!

And be sure to avoid these 10 college essay mistakes .

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Format an Essay

Last Updated: July 29, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Carrie Adkins, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Aly Rusciano . Carrie Adkins is the cofounder of NursingClio, an open access, peer-reviewed, collaborative blog that connects historical scholarship to current issues in gender and medicine. She completed her PhD in American History at the University of Oregon in 2013. While completing her PhD, she earned numerous competitive research grants, teaching fellowships, and writing awards. There are 15 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 91,394 times.

You’re opening your laptop to write an essay, knowing exactly what you want to write, but then it hits you: you don’t know how to format it! Using the correct format when writing an essay can help your paper look polished and professional while earning you full credit. In this article, we'll teach you the basics of formatting an essay according to three common styles: MLA, APA, and Chicago Style.

Setting Up Your Document

- If you can’t find information on the style guide you should be following, talk to your instructor after class to discuss the assignment or send them a quick email with your questions.

- If your instructor lets you pick the format of your essay, opt for the style that matches your course or degree best: MLA is best for English and humanities; APA is typically for education, psychology, and sciences; Chicago Style is common for business, history, and fine arts.

- Most word processors default to 1 inch (2.5 cm) margins.

- Do not change the font size, style, or color throughout your essay.

- Change the spacing on Google Docs by clicking on Format , and then selecting “Line spacing.”

- Click on Layout in Microsoft Word, and then click the arrow at the bottom left of the “paragraph” section.

- Using the page number function will create consecutive numbering.

- When using Chicago Style, don’t include a page number on your title page. The first page after the title page should be numbered starting at 2. [5] X Research source

- In APA format, a running heading may be required in the left-hand header. This is a maximum of 50 characters that’s the full or abbreviated version of your essay’s title. [6] X Research source

- For APA formatting, place the title in bold at the center of the page 3 to 4 lines down from the top. Insert one double-spaced line under the title and type your name. Under your name, in separate centered lines, type out the name of your school, course, instructor, and assignment due date. [8] X Research source

- For Chicago Style, set your cursor ⅓ of the way down the page, then type your title. In the very center of your page, put your name. Move your cursor ⅔ down the page, then write your course number, followed by your instructor’s name and paper due date on separate, double-spaced lines. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Double-space the heading like the rest of your paper.

Writing the Essay Body

- Use standard capitalization rules for your title.

- Do not underline, italicize, or put quotation marks around your title, unless you include other titles of referred texts.

- A good hook might include a quote, statistic, or rhetorical question.

- For example, you might write, “Every day in the United States, accidents caused by distracted drivers kill 9 people and injure more than 1,000 others.”

- "Action must be taken to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving, including enacting laws against texting while driving, educating the public about the risks, and giving strong punishments to offenders."

- "Although passing and enforcing new laws can be challenging, the best way to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving is to enact a law against texting, educate the public about the new law, and levy strong penalties."

- Use transitions between paragraphs so your paper flows well. For example, say, “In addition to,” “Similarly,” or “On the other hand.” [16] X Research source

- A statement of impact might be, "Every day that distracted driving goes unaddressed, another 9 families must plan a funeral."

- A call to action might read, “Fewer distracted driving accidents are possible, but only if every driver keeps their focus on the road.”

Using References

- In MLA format, citations should include the author’s last name and the page number where you found the information. If the author's name appears in the sentence, use just the page number. [18] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For APA format, include the author’s last name and the publication year. If the author’s name appears in the sentence, use just the year. [19] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- If you don’t use parenthetical or internal citations, your instructor may accuse you of plagiarizing.

- At the bottom of the page, include the source’s information from your bibliography page next to the footnote number. [20] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Each footnote should be numbered consecutively.

- If you’re using MLA format, this page will be titled “Works Cited.”

- In APA and Chicago Style, title the page “References.”

- If you have more than one work from the same author, list alphabetically following the title name for MLA and by earliest to latest publication year for APA and Chicago Style.

- Double-space the references page like the rest of your paper.

- Use a hanging indent of 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) if your citations are longer than one line. Press Tab to indent any lines after the first. [23] X Research source

- Citations should include (when applicable) the author(s)’s name(s), title of the work, publication date and/or year, and page numbers.

- Sites like Grammarly , EasyBib , and MyBib can help generate citations if you get stuck.

Formatting Resources

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-englishcomposition1/chapter/text-mla-document-formatting/

- ↑ https://www.une.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/392149/WE_Formatting-your-essay.pdf

- ↑ https://content.nroc.org/DevelopmentalEnglish/unit10/Foundations/formatting-a-college-essay-mla-style.html

- ↑ https://camosun.libguides.com/Chicago-17thEd/titlePage

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/page-header

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/title-page

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/chicago_manual_17th_edition/cmos_formatting_and_style_guide/general_format.html

- ↑ https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/writing-speaking-resources/mla-8-style-format

- ↑ https://cflibguides.lonestar.edu/chicago/paperformat

- ↑ https://www.uvu.edu/writingcenter/docs/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://www.deanza.edu/faculty/cruzmayra/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://monroecollege.libguides.com/c.php?g=589208&p=4073046

- ↑ https://library.menloschool.org/chicago

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Maansi Richard

May 8, 2019

Did this article help you?

Jan 7, 2020

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

What Does an Essay Look Like? Tips and Answers to Succeed

What does an essay look like? At a glance, the answer is obvious. An essay looks like a mere piece of paper (one page or several pages) with an organized text. It’s generally divided into five paragraphs, though there may be more. The essential essay structure includes:

- introduction;

- 2-3 body paragraphs;

- conclusion.

Yet, will this description help you write a good essay? We suppose not because this piece of paper “hides” many secrets inside!

Let our team give you more details and describe what a good essay looks like in reality. We’ll show the inside and out of this academic paper with a few tips on writing it.

📃 What Does an Essay Look Like on the Outside?

First of all, you should know that a good essay should look pretty. How can you do that? By following all the requirements set by your teacher or of a particular formatting style.

- What does an essay look like according to the teacher’s requirements? It is usually a paper with 1-inch margins on all sides typed using a 12 pt. standard font. Standard school and college essays have a five-paragraph format.

- What does an essay look like if it should be arranged according to a format? Depends on the format. MLA and APA are the most popular ones, but there are many more (Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, etc.). Besides, each of them has different editions. Before writing an essay, ensure that you understand what format is required.

| APA Style | MLA Style |

|---|---|

| You have to provide a separate title on the page. Also, remember that a cover page is required in APA style papers. | It is not mandatory to provide a separate title on the page. The cover page is not required, either. |

| Bibliography in APA format is called “References.” | Bibliography in MLA is called “Works Cited.” |

| For the in-text quotation within APA guidelines, a year, a comma after the author’s name, and the page should be included. | For in-text quotations, MLA format does not require a year, a comma after the author’s name, or the page. |

| In APA, heading and subheadings are widely used. | In MLA, headings and subheadings are not used. |

You will also have to set up 1-inch margins, use a 12 pt. font and double spacing throughout the text. However, it is better to get a specific style manual for more details. You can also check our article about MLA or APA styles.

✒️ What Does an Essay Look like on the Inside?

What we mean is how the text itself should be organized. Its content relies on the task given and the paper’s type.

We recommend you follow the instructions and understand clearly what the tutor wants from you regarding the task. If you’re unsure, don’t hesitate to clarify before writing. Checking out some examples of academic essay writing would be helpful too.

The essay type defines the contents of your assignment, considerably affecting the main body of your text. To identify it, make sure you read the task well, and understand what the tutor asked you to do.

In other words:

Not everyone knows that what makes a good essay is how precisely you follow your essay guidelines. First, underline the keywords from your assignment that will help you in doing that. Then, complete the task.

Here is the list of the most common keywords:

- Agree/Disagree. Identify your position and think about a list of arguments that can support your point of view. It can help come up with an essay plan at this point because it will allow you not to deviate from your arguments.

- Analyze. Here, the college instructor or your school teacher wants to test your analytical abilities. They want to see if you can build bridges between the arguments and analyze the relationships between them.

- Compare. This keyword means that you need to demonstrate differences and similarities between problems, ideas, or concepts in your essay.

- Describe/Discuss. On a surface level, to describe is to examine an issue or an object in detail.

- Explain. Similarly, to explain is to tell why the things the way they are.

- Illustrate. Here, your teacher expects you to come up with some great examples to bring the topic alive.

- Interpret. If you find this keyword in your assignment, you should give your understanding of the matter. It should provide some interesting angles of looking at the topic.

- List/State. To write an essay with this keyword in the assignment, make a list of facts or points.

- Summarize. Your essay should focus on the main ideas and problems.

A typical essay structure is split into five paragraphs:

- Introduction: The goal of an introduction is to hook your reader. It sets a tone and prepares for what is yet to come. It is done through your thesis statement. You can start your introduction paragraph with a quote, a short joke, a question, or a historical reference. Don’t try to bring complicated terminology and wording into this part of your essay. Use clear sentences that are engaging and catchy for a high-quality essay introduction.

- Body Paragraphs: Think about this part of your essay as the essay base. Here, you are expected to prove your thesis and find an interesting approach to looking at it. You will have to restate your main idea again, provide evidence that proves it, analyze the evidence, and connect these ideas.

- Conclusion: A conclusion is the last part of your essay, which summarizes the arguments and explains the broader importance of the topic. In a way, a concluding paragraph should answer a “so what?” question. To have a clearer vision of what a conclusion for your essay may look like, you can put its text into a summary machine and see what comes out.

It is a standard structure that allows disclosing a topic properly, logically expressing all your ideas. What does an essay look like if you want to make it original? In this case, it will look like a paper with a couple of pictures, diagrams, or maps.

It is always useful to check some examples before getting down to work. Here you can check how 9th-grade essays should look like.

Thank you for reading this article. We hope you found it useful. Don’t forget to share it with your peers!

References:

- Essay Structure: Elizabeth Abrams, for the Writing Center at Harvard University

- General Essay Writing Tips: Essay Writing Center, International Student

- What is an Essay? How to Write a Good Essay: LibGuides at Bow Valley College

- Academic Essay Structures: Student Support Center Quick Tips, University of Minnesota

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Some students find writing literary analysis papers rather daunting. Yet, an English class cannot go without this kind of work. By the way, writing literary analysis essays is not that complicated as it seems at a glance. On the contrary, this work may be fascinating, and you have a chance...

These days, leadership and ability to work in a team are the skills that everybody should possess. It is impossible to cope with a large educational or work project alone. However, it can also be challenging to collaborate in a team. You might want to elaborate on importance and difficulties...

Racial profiling is not uncommon. It’s incredibly offensive and unfair behavior that causes most of the protests in support of people of color. It occurs when people are suspected of committing a crime based on their skin color or ethnicity. Unfortunately, most people are unaware that racial profiling is an everyday...

Without a doubt, a natural disaster essay is a tough paper to write. To begin with, when people encounter a disaster risk, it’s a tragedy. Emergency situations can affect hundreds, thousands, and millions of people. These are the crises and events that change people’s lives drastically. So, disaster and emergency...

“You are not only responsible for what you say, but also for what you do not say”Martin Luther There are a lot of other good quotations that can serve as a good beginning for your essay on responsibility and provide good ideas for writing.

Exemplification essays, which are also called illustration essays, are considered one of the easiest papers to write. However, even the easiest tasks require some experience and practice. So, if you are not experienced enough in writing exemplification essays, you will face certain challenges.

You push the snooze button once again and finally open your eyes. It is already 8:50, and your classes start at 9. “I’m going to be late again!”— you think, already in full panic mode. In a minute, you rush out the door half-dressed, swallowing your sandwich on the go....

An essay about Harriet Tubman is to focus on the biography and accomplishments of a famous American abolitionist and political activist of the 19th century. Harriet Tubman was born into slavery, escaped it herself, and helped others escape it. She changed many jobs throughout her lifetime, being a housekeeper, a...

What is a documented essay and what is the purpose of it? It is a type of academic writing where the author develops an opinion relying on secondary resources. A documented essay can be assigned in school or college. You should incorporate arguments and facts from outside sources into the...

What is a reflexive essay? If you have just received the assignment and think there is a typo, you’re in the right place. Long story short, no, there is no mistake. You actually need to write a reflexive essay, not a reflective one. The thing is that reflective and reflexive...

Fairies and evil spirits, noble kings and queens, beautiful princesses and brave princes, mysterious castles and abandoned huts somewhere in a thick a wood… This is all about fairy tales. Fairy tales are always associated with childhood. Fairy tales always remind us that love rules the world and the Good...

Subjective or objective essay writing is a common task students have to deal with. On the initial stage of completing the assignment, you should learn how to differentiate these two types of papers. Their goals, methods, as well as language, tone, and voice, are different. A subjective essay focuses on...

I would like an essay to be written for me about Accepting Immigrants as a Citizen

I really don’t understand the connection been a topic and a thesis.

Hey Anna, It’s our pleasure to hear from you. A lot of students have difficulties understanding the connection between a topic and a thesis statement. That’s why we’ve created a super useful guide to cover all your questions. Or, you may want to check out the best examples of thesis statements here . We hope it helps. In case of any questions, do not hesitate to contact us.

Wonder, what does an essay look like! Read the post, and you’ll find the answer to your question and many tips to use in your paper.

It is a common question among first-year students: what does an essay look like and how to write it? You answer all the questions in full! Thank you very much for this!

Academic Essay: From Basics to Practical Tips

Has it ever occurred to you that over the span of a solitary academic term, a typical university student can produce sufficient words to compose an entire 500-page novel? To provide context, this equates to approximately 125,000 to 150,000 words, encompassing essays, research papers, and various written tasks. This content volume is truly remarkable, emphasizing the importance of honing the skill of crafting scholarly essays. Whether you're a seasoned academic or embarking on the initial stages of your educational expedition, grasping the nuances of constructing a meticulously organized and thoroughly researched essay is paramount.

Welcome to our guide on writing an academic essay! Whether you're a seasoned student or just starting your academic journey, the prospect of written homework can be exciting and overwhelming. In this guide, we'll break down the process step by step, offering tips, strategies, and examples to help you navigate the complexities of scholarly writing. By the end, you'll have the tools and confidence to tackle any essay assignment with ease. Let's dive in!

Types of Academic Writing

The process of writing an essay usually encompasses various types of papers, each serving distinct purposes and adhering to specific conventions. Here are some common types of academic writing:

.webp)

- Essays: Essays are versatile expressions of ideas. Descriptive essays vividly portray subjects, narratives share personal stories, expository essays convey information, and persuasive essays aim to influence opinions.

- Research Papers: Research papers are analytical powerhouses. Analytical papers dissect data or topics, while argumentative papers assert a stance backed by evidence and logical reasoning.

- Reports: Reports serve as narratives in specialized fields. Technical reports document scientific or technical research, while business reports distill complex information into actionable insights for organizational decision-making.

- Reviews: Literature reviews provide comprehensive summaries and evaluations of existing research, while critical analyses delve into the intricacies of books or movies, dissecting themes and artistic elements.

- Dissertations and Theses: Dissertations represent extensive research endeavors, often at the doctoral level, exploring profound subjects. Theses, common in master's programs, showcase mastery over specific topics within defined scopes.

- Summaries and Abstracts: Summaries and abstracts condense larger works. Abstracts provide concise overviews, offering glimpses into key points and findings.

- Case Studies: Case studies immerse readers in detailed analyses of specific instances, bridging theoretical concepts with practical applications in real-world scenarios.

- Reflective Journals: Reflective journals serve as personal platforms for articulating thoughts and insights based on one's academic journey, fostering self-expression and intellectual growth.

- Academic Articles: Scholarly articles, published in academic journals, constitute the backbone of disseminating original research, contributing to the collective knowledge within specific fields.

- Literary Analyses: Literary analyses unravel the complexities of written works, decoding themes, linguistic nuances, and artistic elements, fostering a deeper appreciation for literature.

Our essay writer service can cater to all types of academic writings that you might encounter on your educational path. Use it to gain the upper hand in school or college and save precious free time.

Essay Writing Process Explained

The process of how to write an academic essay involves a series of important steps. To start, you'll want to do some pre-writing, where you brainstorm essay topics , gather information, and get a good grasp of your topic. This lays the groundwork for your essay.

Once you have a clear understanding, it's time to draft your essay. Begin with an introduction that grabs the reader's attention, gives some context, and states your main argument or thesis. The body of your essay follows, where each paragraph focuses on a specific point supported by examples or evidence. Make sure your ideas flow smoothly from one paragraph to the next, creating a coherent and engaging narrative.

After the drafting phase, take time to revise and refine your essay. Check for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Ensure your ideas are well-organized and that your writing effectively communicates your message. Finally, wrap up your essay with a strong conclusion that summarizes your main points and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

How to Prepare for Essay Writing

Before you start writing an academic essay, there are a few things to sort out. First, make sure you totally get what the assignment is asking for. Break down the instructions and note any specific rules from your teacher. This sets the groundwork.

Then, do some good research. Check out books, articles, or trustworthy websites to gather solid info about your topic. Knowing your stuff makes your essay way stronger. Take a bit of time to brainstorm ideas and sketch out an outline. It helps you organize your thoughts and plan how your essay will flow. Think about the main points you want to get across.

Lastly, be super clear about your main argument or thesis. This is like the main point of your essay, so make it strong. Considering who's going to read your essay is also smart. Use language and tone that suits your academic audience. By ticking off these steps, you'll be in great shape to tackle your essay with confidence.

Academic Essay Example

In academic essays, examples act like guiding stars, showing the way to excellence. Let's check out some good examples to help you on your journey to doing well in your studies.

Academic Essay Format

The academic essay format typically follows a structured approach to convey ideas and arguments effectively. Here's an academic essay format example with a breakdown of the key elements:

Introduction

- Hook: Begin with an attention-grabbing opening to engage the reader.

- Background/Context: Provide the necessary background information to set the stage.

- Thesis Statement: Clearly state the main argument or purpose of the essay.

Body Paragraphs

- Topic Sentence: Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis.

- Supporting Evidence: Include evidence, examples, or data to back up your points.

- Analysis: Analyze and interpret the evidence, explaining its significance in relation to your argument.

- Transition Sentences: Use these to guide the reader smoothly from one point to the next.

Counterargument (if applicable)

- Address Counterpoints: Acknowledge opposing views or potential objections.

- Rebuttal: Refute counterarguments and reinforce your position.

Conclusion:

- Restate Thesis: Summarize the main argument without introducing new points.

- Summary of Key Points: Recap the main supporting points made in the body.

- Closing Statement: End with a strong concluding thought or call to action.

References/Bibliography

- Cite Sources: Include proper citations for all external information used in the essay.

- Follow Citation Style: Use the required citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) specified by your instructor.

- Font and Size: Use a standard font (e.g., Times New Roman, Arial) and size (12-point).

- Margins and Spacing: Follow specified margin and spacing guidelines.

- Page Numbers: Include page numbers if required.

Adhering to this structure helps create a well-organized and coherent academic essay that effectively communicates your ideas and arguments.

Ready to Transform Essay Woes into Academic Triumphs?

Let us take you on an essay-writing adventure where brilliance knows no bounds!

How to Write an Academic Essay Step by Step

Start with an introduction.

The introduction of an essay serves as the reader's initial encounter with the topic, setting the tone for the entire piece. It aims to capture attention, generate interest, and establish a clear pathway for the reader to follow. A well-crafted introduction provides a brief overview of the subject matter, hinting at the forthcoming discussion, and compels the reader to delve further into the essay. Consult our detailed guide on how to write an essay introduction for extra details.

Captivate Your Reader

Engaging the reader within the introduction is crucial for sustaining interest throughout the essay. This involves incorporating an engaging hook, such as a thought-provoking question, a compelling anecdote, or a relevant quote. By presenting an intriguing opening, the writer can entice the reader to continue exploring the essay, fostering a sense of curiosity and investment in the upcoming content. To learn more about how to write a hook for an essay , please consult our guide,

Provide Context for a Chosen Topic

In essay writing, providing context for the chosen topic is essential to ensure that readers, regardless of their prior knowledge, can comprehend the subject matter. This involves offering background information, defining key terms, and establishing the broader context within which the essay unfolds. Contextualization sets the stage, enabling readers to grasp the significance of the topic and its relevance within a particular framework. If you buy a dissertation or essay, or any other type of academic writing, our writers will produce an introduction that follows all the mentioned quality criteria.

Make a Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the central anchor of the essay, encapsulating its main argument or purpose. It typically appears towards the end of the introduction, providing a concise and clear declaration of the writer's stance on the chosen topic. A strong thesis guides the reader on what to expect, serving as a roadmap for the essay's subsequent development.

Outline the Structure of Your Essay

Clearly outlining the structure of the essay in the introduction provides readers with a roadmap for navigating the content. This involves briefly highlighting the main points or arguments that will be explored in the body paragraphs. By offering a structural overview, the writer enhances the essay's coherence, making it easier for the reader to follow the logical progression of ideas and supporting evidence throughout the text.

Continue with the Main Body

The main body is the most important aspect of how to write an academic essay where the in-depth exploration and development of the chosen topic occur. Each paragraph within this section should focus on a specific aspect of the argument or present supporting evidence. It is essential to maintain a logical flow between paragraphs, using clear transitions to guide the reader seamlessly from one point to the next. The main body is an opportunity to delve into the nuances of the topic, providing thorough analysis and interpretation to substantiate the thesis statement.

Choose the Right Length

Determining the appropriate length for an essay is a critical aspect of effective communication. The length should align with the depth and complexity of the chosen topic, ensuring that the essay adequately explores key points without unnecessary repetition or omission of essential information. Striking a balance is key – a well-developed essay neither overextends nor underrepresents the subject matter. Adhering to any specified word count or page limit set by the assignment guidelines is crucial to meet academic requirements while maintaining clarity and coherence.

Write Compelling Paragraphs

In academic essay writing, thought-provoking paragraphs form the backbone of the main body, each contributing to the overall argument or analysis. Each paragraph should begin with a clear topic sentence that encapsulates the main point, followed by supporting evidence or examples. Thoroughly analyzing the evidence and providing insightful commentary demonstrates the depth of understanding and contributes to the overall persuasiveness of the essay. Cohesion between paragraphs is crucial, achieved through effective transitions that ensure a smooth and logical progression of ideas, enhancing the overall readability and impact of the essay.

Finish by Writing a Conclusion

The conclusion serves as the essay's final impression, providing closure and reinforcing the key insights. It involves restating the thesis without introducing new information, summarizing the main points addressed in the body, and offering a compelling closing thought. The goal is to leave a lasting impact on the reader, emphasizing the significance of the discussed topic and the validity of the thesis statement. A well-crafted conclusion brings the essay full circle, leaving the reader with a sense of resolution and understanding. Have you already seen our collection of new persuasive essay topics ? If not, we suggest you do it right after finishing this article to boost your creativity!

Proofread and Edit the Document

After completing the essay, a critical step is meticulous proofreading and editing. This process involves reviewing the document for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. Additionally, assess the overall coherence and flow of ideas, ensuring that each paragraph contributes effectively to the essay's purpose. Consider the clarity of expression, the appropriateness of language, and the overall organization of the content. Taking the time to proofread and edit enhances the overall quality of the essay, presenting a polished and professional piece of writing. It is advisable to seek feedback from peers or instructors to gain additional perspectives on the essay's strengths and areas for improvement. For more insightful tips, feel free to check out our guide on how to write a descriptive essay .

Alright, let's wrap it up. Knowing how to write academic essays is a big deal. It's not just about passing assignments – it's a skill that sets you up for effective communication and deep thinking. These essays teach us to explain our ideas clearly, build strong arguments, and be part of important conversations, both in school and out in the real world. Whether you're studying or working, being able to put your thoughts into words is super valuable. So, take the time to master this skill – it's a game-changer!

Ready to Turn Your Academic Aspirations into A+ Realities?

Our expert pens are poised, and your academic adventure awaits!

What Is An Academic Essay?

How to write an academic essay, how to write a good academic essay.

Daniel Parker

is a seasoned educational writer focusing on scholarship guidance, research papers, and various forms of academic essays including reflective and narrative essays. His expertise also extends to detailed case studies. A scholar with a background in English Literature and Education, Daniel’s work on EssayPro blog aims to support students in achieving academic excellence and securing scholarships. His hobbies include reading classic literature and participating in academic forums.

is an expert in nursing and healthcare, with a strong background in history, law, and literature. Holding advanced degrees in nursing and public health, his analytical approach and comprehensive knowledge help students navigate complex topics. On EssayPro blog, Adam provides insightful articles on everything from historical analysis to the intricacies of healthcare policies. In his downtime, he enjoys historical documentaries and volunteering at local clinics.

.webp)

English Composition 1

The proper format for essays.

Below are guidelines for the formatting of essays based on recommendations from the MLA (the Modern Language Association).

- Fonts : Your essay should be word processed in 12-point Times New Roman fonts.

- Double space : Your entire essay should be double spaced, with no single spacing anywhere and no extra spacing anywhere. There should not be extra spaces between paragraphs.

- Heading : In the upper left corner of the first page of your essay, you should type your name, the instructor's name, your class, and the date, as follows: Your Name Mr. Rambo ENG 1001-100 18 January 2022

- Margins : According to the MLA, your essay should have a one-inch margin on the top, bottom, left, and right.

- Page Numbers : Your last name and the page number should appear in the upper right corner of each page of your essay, including the first page, as in Jones 3 . Insert your name and the page number as a "header." Do not type this information where the text of your essay should be.

- Title : Your essay should include a title. The title should be centered and should appear under the heading information on the first page and above the first line of your essay. The title should be in the same fonts as the rest of your essay, with no quotation marks, no underlining, no italics, and no bold.

- Indentation : The first line of each paragraph should be indented. According to the MLA, this indentation should be 1/2 inch or five spaces, but pressing [Tab] once should give you the correct indentation.

Putting all of the above together, you should have a first page that looks like the following:

Copyright Randy Rambo , 2022.

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

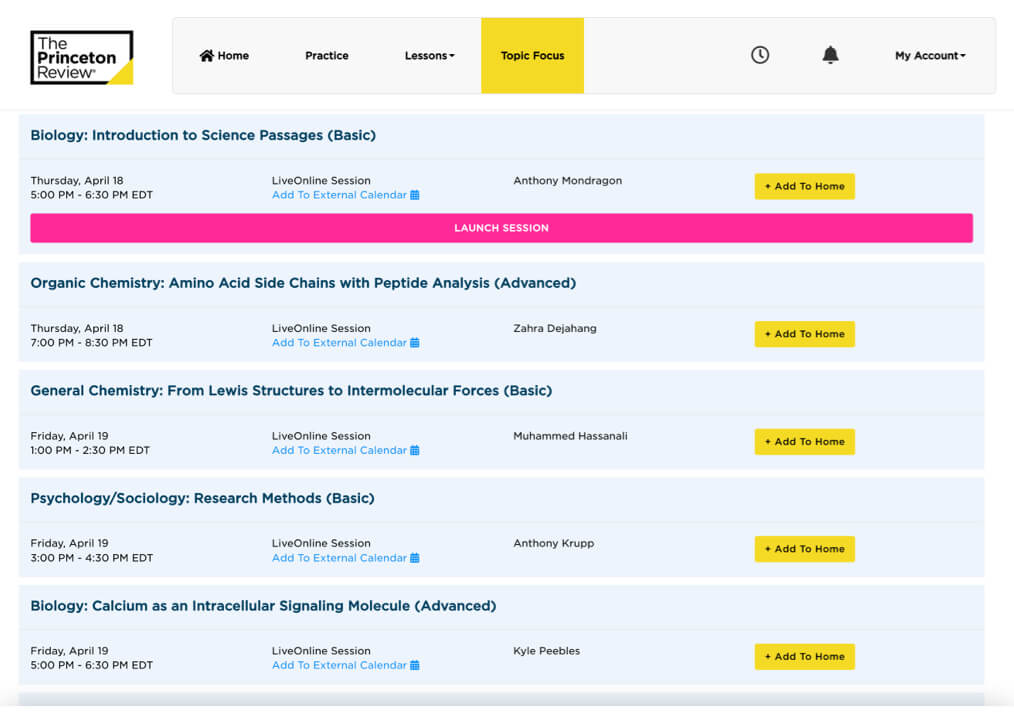

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

We are experiencing sporadically slow performance in our online tools, which you may notice when working in your dashboard. Our team is fully engaged and actively working to improve your online experience. If you are experiencing a connectivity issue, we recommend you try again in 10-15 minutes. We will update this space when the issue is resolved.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., crafting an unforgettable college essay.

Most selective colleges require you to submit an essay or personal statement as part of your application.

It may sound like a chore, and it will certainly take a substantial amount of work. But it's also a unique opportunity that can make a difference at decision time. Admissions committees put the most weight on your high school grades and your test scores . However, selective colleges receive applications from many worthy students with similar scores and grades—too many to admit. So they use your essay, along with your letters of recommendation and extracurricular activities , to find out what sets you apart from the other talented candidates.

Telling Your Story to Colleges

So what does set you apart?

You have a unique background, interests and personality. This is your chance to tell your story (or at least part of it). The best way to tell your story is to write a personal, thoughtful essay about something that has meaning for you. Be honest and genuine, and your unique qualities will shine through.

Admissions officers have to read an unbelievable number of college essays, most of which are forgettable. Many students try to sound smart rather than sounding like themselves. Others write about a subject that they don't care about, but that they think will impress admissions officers.

You don't need to have started your own business or have spent the summer hiking the Appalachian Trail. Colleges are simply looking for thoughtful, motivated students who will add something to the first-year class.

Tips for a Stellar College Application Essay

1. write about something that's important to you..

It could be an experience, a person, a book—anything that has had an impact on your life.

2. Don't just recount—reflect!

Anyone can write about how they won the big game or the summer they spent in Rome. When recalling these events, you need to give more than the play-by-play or itinerary. Describe what you learned from the experience and how it changed you.

Free SAT Practice Tests & Events

Evaluate and improve your SAT score.

3. Being funny is tough.

A student who can make an admissions officer laugh never gets lost in the shuffle. But beware. What you think is funny and what an adult working in a college thinks is funny are probably different. We caution against one-liners, limericks and anything off–color.

4. Start early and write several drafts.

Set it aside for a few days and read it again. Put yourself in the shoes of an admissions officer: Is the essay interesting? Do the ideas flow logically? Does it reveal something about the applicant? Is it written in the applicant’s own voice?

5. No repeats.

What you write in your application essay or personal statement should not contradict any other part of your application–nor should it repeat it. This isn't the place to list your awards or discuss your grades or test scores.

6. Answer the question being asked.

Don't reuse an answer to a similar question from another application.

7. Have at least one other person edit your essay.

A teacher or college counselor is your best resource. And before you send it off, check, check again, and then triple check to make sure your essay is free of spelling or grammar errors.

Read More: 2018-2019 Common Application Essay Prompts (and How to Answer Them)

Test Your College Knowledge

How well do you understand the college admissions process? Find out with our quiz.

Take the Quiz

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

I already know my score.

MCAT Self-Paced 14-Day Free Trial

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

How An Essay Paper Should Look Like

- Author Sandra W.

This Is How An Essay Paper Should Look Like

A basic essay consists of three main parts: introduction, body, and conclusion. This type of format will help you write and organize an essay. However, flexibility is important. While keeping this basic essay format in mind, let the topic and specific assignment guide the writing and organization.

Parts Of An Essay

Introduction

The introduction guides the reader into the paper by introducing the topic. It should begin with a hook that catches the reader’s interest. This hook could be a quote, an analogy, a question, etc. After getting the reader’s attention, the introduction should give some background information on the topic. The ideas within the introduction should be general enough for the reader to understand the main claim and gradually become more specific to lead into the thesis statement.

Thesis Statement

The thesis statement concisely states the main idea or argument of the essay, sets limits on the topic, and can indicate the organization of the essay. The thesis works as a road map for the entire essay, showing the readers what you have to say and which main points you will use to support your ideas.

The body of the essay supports the main points presented in the thesis. Each point is developed by one or more paragraphs and supported with specific details. These details can include support from research and experiences, depending on the assignment. In addition to this support, the author’s own analysis and discussion of the topic ties ideas together and draws conclusions that support the thesis. Transitions

Transitions connect paragraphs to each other and to the thesis. They are used within and between paragraphs to help the paper flow from one topic to the next. These transitions can be one or two words ("first,†"next,†"in addition,†etc.) or one or two sentences that bring the reader to the next main point. The topic sentence of a paragraph often serves as a transition.

The conclusion brings together all the main points of the essay. It refers back to the thesis statement and leaves readers with a final thought and sense of closure by resolving any ideas brought up in the essay. It may also address the implications of the argument. In the conclusion, new topics or ideas that were not developed in the paper should not be introduced.

If your paper incorporates research, be sure to give credit to each source using in-text citations and a Works Cited/References/Bibliography page.

Parts of a Paragraph

In an essay, a paragraph discusses one idea in detail that supports the thesis of the essay. Each paragraph in the body of the paper should include a topic sentence, supporting details to support the topic sentence, and a concluding sentence. The paragraph’s purpose and scope will determine its length, but most paragraphs contain at least two complete sentences.

Topic Sentence

The main idea of each paragraph is stated in a topic sentence that shows how the idea relates to the thesis. Generally, the topic sentence is placed at the beginning of a paragraph, but the location and placement may vary according to individual organization and audience expectation. Topic sentences often serve as transitions between paragraphs.

Supporting Details

Supporting details elaborate upon the topic sentences and thesis. Supporting details should be drawn from a variety of sources determined by the assignment guidelines and genre, and should include the writer’s own analysis.

Concluding Sentence

Each paragraph should end with a final statement that brings together the ideas brought up in the paragraph. Sometimes, it can serve as a transition to the next paragraph.

Recent Posts

- A Sample Essay on Birds 21-08-2023 0 Comments

- Is Homeschooling an Ideal Way... 21-08-2023 0 Comments

- Essay Sample on Man 14-08-2023 0 Comments

- Academic Writing(23)

- Admission Essay(172)

- Book Summaries(165)

- College Tips(312)

- Content Writing Services(1)

- Essay Help(517)

- Essay Writing Help(76)

- Essays Blog(0)

- Example(337)

- Infographics(2)

- Letter Writing(1)

- Outlines(137)

- Photo Essay Assignment(4)

- Resume Writing Tips(62)

- Samples Essays(315)

- Writing Jobs(2)

How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

The important sentence expresses your central assertion or argument

arabianEye / Getty Images

- Writing Research Papers

- Writing Essays

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A thesis statement provides the foundation for your entire research paper or essay. This statement is the central assertion that you want to express in your essay. A successful thesis statement is one that is made up of one or two sentences clearly laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

Usually, the thesis statement will appear at the end of the first paragraph of your paper. There are a few different types, and the content of your thesis statement will depend upon the type of paper you’re writing.

Key Takeaways: Writing a Thesis Statement

- A thesis statement gives your reader a preview of your paper's content by laying out your central idea and expressing an informed, reasoned answer to your research question.

- Thesis statements will vary depending on the type of paper you are writing, such as an expository essay, argument paper, or analytical essay.

- Before creating a thesis statement, determine whether you are defending a stance, giving an overview of an event, object, or process, or analyzing your subject

Expository Essay Thesis Statement Examples

An expository essay "exposes" the reader to a new topic; it informs the reader with details, descriptions, or explanations of a subject. If you are writing an expository essay , your thesis statement should explain to the reader what she will learn in your essay. For example:

- The United States spends more money on its military budget than all the industrialized nations combined.

- Gun-related homicides and suicides are increasing after years of decline.

- Hate crimes have increased three years in a row, according to the FBI.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increases the risk of stroke and arterial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat).

These statements provide a statement of fact about the topic (not just opinion) but leave the door open for you to elaborate with plenty of details. In an expository essay, you don't need to develop an argument or prove anything; you only need to understand your topic and present it in a logical manner. A good thesis statement in an expository essay always leaves the reader wanting more details.

Types of Thesis Statements

Before creating a thesis statement, it's important to ask a few basic questions, which will help you determine the kind of essay or paper you plan to create:

- Are you defending a stance in a controversial essay ?

- Are you simply giving an overview or describing an event, object, or process?

- Are you conducting an analysis of an event, object, or process?

In every thesis statement , you will give the reader a preview of your paper's content, but the message will differ a little depending on the essay type .

Argument Thesis Statement Examples

If you have been instructed to take a stance on one side of a controversial issue, you will need to write an argument essay . Your thesis statement should express the stance you are taking and may give the reader a preview or a hint of your evidence. The thesis of an argument essay could look something like the following:

- Self-driving cars are too dangerous and should be banned from the roadways.

- The exploration of outer space is a waste of money; instead, funds should go toward solving issues on Earth, such as poverty, hunger, global warming, and traffic congestion.

- The U.S. must crack down on illegal immigration.

- Street cameras and street-view maps have led to a total loss of privacy in the United States and elsewhere.

These thesis statements are effective because they offer opinions that can be supported by evidence. If you are writing an argument essay, you can craft your own thesis around the structure of the statements above.

Analytical Essay Thesis Statement Examples

In an analytical essay assignment, you will be expected to break down a topic, process, or object in order to observe and analyze your subject piece by piece. Examples of a thesis statement for an analytical essay include:

- The criminal justice reform bill passed by the U.S. Senate in late 2018 (" The First Step Act ") aims to reduce prison sentences that disproportionately fall on nonwhite criminal defendants.

- The rise in populism and nationalism in the U.S. and European democracies has coincided with the decline of moderate and centrist parties that have dominated since WWII.

- Later-start school days increase student success for a variety of reasons.

Because the role of the thesis statement is to state the central message of your entire paper, it is important to revisit (and maybe rewrite) your thesis statement after the paper is written. In fact, it is quite normal for your message to change as you construct your paper.

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

- Revising a Paper

- Your Personal Essay Thesis Sentence

- How to Develop a Research Paper Timeline

- Ethos, Logos, Pathos for Persuasion

- How to Narrow the Research Topic for Your Paper

- World War II Research Essay Topics

- What Is a Senior Thesis?

- How to Use Verbs Effectively in Your Research Paper

- When to Cite a Source in a Paper

- Writing an Annotated Bibliography for a Paper

- Finding Trustworthy Sources

- How to Write a 10-Page Research Paper

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- What Is an Autobiography?

- Finding Statistics and Data for Research Papers

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How long is an essay? Guidelines for different types of essay

How Long is an Essay? Guidelines for Different Types of Essay

Published on January 28, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on July 23, 2023.

The length of an academic essay varies depending on your level and subject of study, departmental guidelines, and specific course requirements. In general, an essay is a shorter piece of writing than a research paper or thesis .

In most cases, your assignment will include clear guidelines on the number of words or pages you are expected to write. Often this will be a range rather than an exact number (for example, 2500–3000 words, or 10–12 pages). If you’re not sure, always check with your instructor.

In this article you’ll find some general guidelines for the length of different types of essay. But keep in mind that quality is more important than quantity – focus on making a strong argument or analysis, not on hitting a specific word count.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Essay length guidelines, how long is each part of an essay, using length as a guide to topic and complexity, can i go under the suggested length, can i go over the suggested length, other interesting articles.

| Type of essay | Average word count range | Essay content |

|---|---|---|

| High school essay | 300–1000 words | In high school you are often asked to write a 5-paragraph essay, composed of an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. |

| College admission essay | 200–650 words | College applications require a short personal essay to express your interests and motivations. This generally has a strict word limit. |

| Undergraduate college essay | 1500–5000 words | The length and content of essay assignments in college varies depending on the institution, department, course level, and syllabus. |

| Graduate school admission essay | 500–1000 words | Graduate school applications usually require a longer and/or detailing your academic achievements and motivations. |

| Graduate school essay | 2500–6000 words | Graduate-level assignments vary by institution and discipline, but are likely to include longer essays or research papers. |

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In an academic essay, the main body should always take up the most space. This is where you make your arguments, give your evidence, and develop your ideas.

The introduction should be proportional to the essay’s length. In an essay under 3000 words, the introduction is usually just one paragraph. In longer and more complex essays, you might need to lay out the background and introduce your argument over two or three paragraphs.

The conclusion of an essay is often a single paragraph, even in longer essays. It doesn’t have to summarize every step of your essay, but should tie together your main points in a concise, convincing way.

The suggested word count doesn’t only tell you how long your essay should be – it also helps you work out how much information and complexity you can fit into the given space. This should guide the development of your thesis statement , which identifies the main topic of your essay and sets the boundaries of your overall argument.

A short essay will need a focused, specific topic and a clear, straightforward line of argument. A longer essay should still be focused, but it might call for a broader approach to the topic or a more complex, ambitious argument.

As you make an outline of your essay , make sure you have a clear idea of how much evidence, detail and argumentation will be needed to support your thesis. If you find that you don’t have enough ideas to fill out the word count, or that you need more space to make a convincing case, then consider revising your thesis to be more general or more specific.

The length of the essay also influences how much time you will need to spend on editing and proofreading .

You should always aim to meet the minimum length given in your assignment. If you are struggling to reach the word count:

- Add more evidence and examples to each paragraph to clarify or strengthen your points.

- Make sure you have fully explained or analyzed each example, and try to develop your points in more detail.

- Address a different aspect of your topic in a new paragraph. This might involve revising your thesis statement to make a more ambitious argument.

- Don’t use filler. Adding unnecessary words or complicated sentences will make your essay weaker and your argument less clear.

- Don’t fixate on an exact number. Your marker probably won’t care about 50 or 100 words – it’s more important that your argument is convincing and adequately developed for an essay of the suggested length.

In some cases, you are allowed to exceed the upper word limit by 10% – so for an assignment of 2500–3000 words, you could write an absolute maximum of 3300 words. However, the rules depend on your course and institution, so always check with your instructor if you’re unsure.

Only exceed the word count if it’s really necessary to complete your argument. Longer essays take longer to grade, so avoid annoying your marker with extra work! If you are struggling to edit down:

- Check that every paragraph is relevant to your argument, and cut out irrelevant or out-of-place information.

- Make sure each paragraph focuses on one point and doesn’t meander.

- Cut out filler words and make sure each sentence is clear, concise, and related to the paragraph’s point.

- Don’t cut anything that is necessary to the logic of your argument. If you remove a paragraph, make sure to revise your transitions and fit all your points together.

- Don’t sacrifice the introduction or conclusion . These paragraphs are crucial to an effective essay –make sure you leave enough space to thoroughly introduce your topic and decisively wrap up your argument.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, July 23). How Long is an Essay? Guidelines for Different Types of Essay. Scribbr. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/length/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, how to conclude an essay | interactive example, how to write a statement of purpose | example, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, what does a good college essay look like.

Can someone help me understand what admissions officers are actually looking for in a college essay? I'm kinda stressing because I want to write something that stands out but still sounds like 'me'. I hear a lot about showing personality and being memorable, but what does that look like in practice? Would really appreciate any tips or examples you guys might share!

Hey there! I totally understand the stress you're feeling - the college essay can seem like a huge task. In essence, admissions officers are looking for an authentic and compelling glimpse into who you are. The key is to share a story or experience that is unique to you, one that showcases your personality, your perspective, and your values. It's not just what you've done, but how you reflect on those experiences and what you've learned from them that counts.

For example, instead of saying you love to volunteer, delve into a specific moment during your volunteering that changed your view on something or helped you grow. The best essays often focus on small, personal stories that highlight bigger truths about you. Remember, the goal is to give them a reason to remember you among the thousands of essays they read. Also, don't shy away from your voice and writing style, as long as it's appropriate and polished; if you're naturally humorous, it's okay to be a bit funny, or if you're a deep thinker, dive into those reflections.

Don't forget, it's always a great idea to have others read your essay - a teacher, mentor, or someone whose writing you admire. They can provide valuable feedback on whether your 'voice' is coming through and if your essay is striking the right note. Best of luck - you've got this!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

What Should a Narrative Essay Format Look Like?

How to Write an Essay on a Challenge

Narrative essays give you the opportunity to write about a moment that shaped your values, molded your beliefs or taught you a valuable lesson. Using storytelling elements like characterization, dialogue and description, a narrative essay dramatizes your experience, much the way a fiction writer uses these devices to unfold a short story. Structure, development and detail are all necessary to developing an effective narrative essay.

A narrative essay begins with an opening that introduces readers to the characters, setting and conflict. Rather than starting with lengthy details or narration, good introductions drop readers in the middle of the action. For example, if you're writing about learning how to ride a bike, you might open with a description of your parents cheering you on as you ride across the yard, then fall over on the sidewalk. This introduction sets up the challenge you faced and generates sympathy in readers, encouraging them to read on.

The Story Arc

In short stories, fiction writers often use the traditional structure of rising action, climactic action and falling action. Because your essay also has a plot, you too will employ these elements. Your essay's action should move toward a significant moment, such as an accomplishment, failure or realization, that encapsulates the importance of your experience. For example, you could expand your bike essay by showing how falling didn't defeat you; you continued to try up to the moment your parents pushed you off, and you finally could ride on your own.

The Story's Vivid World

Without detail your essay will merely summarize your experience, but the sights, sounds and smells that make the memory so vivid can help readers experience the emotions you felt when you lived through it. For example, the essay about learning to ride your bike might describe the scrape of pavement against your knees when you fell, the rich scent of freshly mowed grass and the exhilarating feeling of wind against your face as you achieved your goal of riding a bike.

The Final Moment

A narrative essay's last paragraph should leave readers with an understanding of why this experience was so important to you and how you changed as a result. In the bike-riding essay, you might end with a description of how you rode not just across your family's yard but down the street and toward the next block, the farthest you'd ever been from home alone. This image communicates that learning to ride a bike wasn't just a lesson in perseverance but also a big step toward independence.

Related Articles

How to Write an Autobiography for a College Assignment

How to Write One Well-Developed Narrative Paragraph

How to Write a Narrative Essay

How to Write a Self-Portrait Essay

How to Start a Personal Essay for High School English

What Is the Meaning of the Poem "In the Valley of Cauteretz"?

How to Add Figurative Language to an Essay

- Indiana River State College: Narration Essay Guidelines

- Southeastern Louisiana University: The Descriptive Narrative Essay

- Write Source: Sample Essay: The Climb

Kori Morgan holds a Bachelor of Arts in professional writing and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing and has been crafting online and print educational materials since 2006. She taught creative writing and composition at West Virginia University and the University of Akron and her fiction, poetry and essays have appeared in numerous literary journals.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Two Paths for Jewish Politics

My first and only experience of antisemitism in America came wrapped in a bow of care and concern. In 1993, I spent the summer in Tennessee with my girlfriend. At a barbecue, we were peppered with questions. What brought us south? How were we getting on? Where did we go to church? We explained that we didn’t go to church because we were Jewish. “That’s O.K.,” a woman reassured us. Having never thought that it wasn’t, I flashed a puzzled smile and recalled an observation of the German writer Ludwig Börne: “Some reproach me with being a Jew, others pardon me, still others praise me for it. But all are thinking about it.”

Thirty-one years later, everyone’s thinking about the Jews. Poll after poll asks them if they feel safe. Donald Trump and Kamala Harris lob insults about who’s the greater antisemite. Congressional Republicans, who have all of two Jews in their caucus , deliver lectures on Jewish history to university leaders. “I want you to kneel down and touch the stone which paved the grounds of Auschwitz,” the Oregon Republican Lori Chavez-DeRemer declared at a hearing in May, urging a visit to D.C.’s Holocaust museum. “I want you to peer over the countless shoes of murdered Jews.” She gave no indication of knowing that one of the leaders she was addressing had been a victim of antisemitism or that another was the descendant of Holocaust survivors.

It’s no accident that non-Jews talk about Jews as if we aren’t there. According to the historian David Nirenberg , talking about the Jews—not actual Jews but Jews in the abstract—is how Gentiles make sense of their world, from the largest questions of existence to the smallest questions of economics. Nirenberg’s focus is “anti-Judaism,” how negative ideas about Jews are woven into canons of Western thought. But as I learned that summer in Tennessee, and as we’re seeing today, concern can be as revealing as contempt. Often the two go hand in hand.

Consider the Antisemitism Awareness Act , which the House of Representatives recently passed by a vote of 320–91. The act purports to be a response to rising antisemitism in the United States. Yet the murder of Jews, synagogue shootings, and cries of “Jews will not replace us” are clearly not what the bill is designed to address. Nearly half of Republicans believe in the “great replacement theory,” after all, and their leader draws from the same well .