- About School

- The Founder and History

- School Management

- Accreditations

- Information About The Organisation

- Our partners

- Contact Details

- International Programme

- Russian Programme

- Extracurricular Activities

- Academic Results

- Tuition fees

- Open house days

- Fill out the request for the Russian programme

- Fill out the request form to English National curriculum

- School №1 from 2 to 7 years

- School №2 from 7 to 11 years

- School №3 from 11 to 18 years

- School №5 from 4 to 18 years

- School №7 from 11 to 18 years

- School №9 from 3 to 11 years

- Student Community

- BIS Alumni Community

- Video gallery

- Mass media about us

- Our Schools

- Communities

- +7 (495) 987-44-86

- +7 (495) 426-03-11

- [email protected]

The Russian Educational System vs the British One

In this article let's find out the differences between the Russian educational system and the British one.

Often, open-minded parents look for a replacement for the Russian school system, seeing obvious flaws in it. A good alternative would be a British school. Such education is highly valued in many countries: England occupies the first position in the world’s best universities ranking.

The structure of the educational system

Kindergarten.

The first difference is that a kindergarten in Russia is usually an independent institution, while in the UK, children can go to school from the age of 3. There, several stages of preschool preparation are organised for them, each of them has its own pedagogical goals.

At the British International School , for example, there are 2 groups where we prepare children for basic education: Nursery and Reception. The teachers communicate with the children in English, but just in case there is a Russian-speaking assistant in the class.

Primary And Secondary School

Children are admitted to Russian primary schools from the age of 6-7, while in the UK, children enter the first grade at the age of 5. This is obligatory for everyone.

Secondary education is compulsory in both the Russian and British systems. Pupils at a comprehensive school in Russia can receive a certificate after the 9th grade, whereas in the UK it’s only after the 11th grade. Years 10 and 11 are devoted to studying the IGCSE programme. At the end there are exams. After successfully passing them, an international certificate of secondary education is given. This is the last stage of compulsory general education in the UK.

Pre-University Training

Some schools offer pre-university training in Years 12 and 13. By the way, BIS is the only one in Moscow that offers its students two international programmes to choose from: IB Diploma and A-level . They each last for 2 years and are highly regarded by universities around the world.

Holidays and School Calendar

In a typical Russian school, each academic year consists of 4 quarters of 2–2.5 months. Senior students attend classes 6 days a week, younger students go to school 5 days a week. After each quarter, children go on holiday, which lasts a week-and-a-half. At the end of the year, the longest break is as long as 3 months.

In the UK, they study by trimesters. In the middle of each trimester is a week of rest, or half-term break. There are long holidays between terms: 6 weeks in summer, and 2–3 for Easter and Christmas. Children go to school 5 days a week regardless of age.

Study Load and Programme Slant

In these aspects, the school systems of Russia and the UK differ greatly.

First of all, the British curriculum is structured completely differently. The older the students, the fewer compulsory subjects. From the very beginning, this system helps students to determine their areas of interest and to choose subjects useful for future work. The Russian system is the opposite. In the first grade, only basic subjects are studied, and more new subjects are added every year. The goal of the Russian educational system is to broaden students’ horizons as much as possible, whereas the British one helps to choose the future profession.

The second great difference is the approach to teaching. You can often hear about the individual approach in Russian schools, but it is important to understand that it is hardly possible to implement it there. It is all about the number of students in a class. In Russia, there are 25 and sometimes 30 people. In Great Britain it is 15–20. Therefore, British parents can be sure that their children will definitely be able to receive material adapted to their individual abilities, and the teacher will have enough time for everyone.

In addition, the focus of the educational programme is different. From an early age, the British are brought up to be responsible and independent, while Russian children are brought up to be patient, you cannot say otherwise. In Russia, schoolchildren get a huge number of homework assignments, many of them require learning by heart. In a British school, on the contrary, they encourage children to research, to find information by themselves and to come to conclusions. In the classroom, they discuss - not retell - textbooks. A great deal of time is devoted to creative tasks.

The British International School has been working in Moscow for 30 years and teaches children according to the national curriculum of England. Our experience shows that the British educational system is truly progressive. It gives not only deep academic knowledge, but prepares students for further study, work and adult life.

MORE TO READ:

Benefits of studying at an international school

How to make your child interested in learning English?

Soft skills for children

Email Newsletter

Receive free lesson plans, printables, and worksheets by email:

How Are K-12 Schools Different In Russia (Compared To The U.S.)?

The question on how are K-12 schools different in Russia (Compared to the U.S.) can best be answered by looking at how they are basically structured and identifying their most distinct features. The policies on education of both countries as well as the education system control mechanisms in place at local and federal levels must then be compared. Although the structures of the educational system of both the US are similar in many ways, there are a few peculiarities that distinguish one from the other.

The American Education System

In the United States, there is no such thing as a national school system because the service of providing education to the public is decentralized. The American Constitution grants the exclusive power to craft and implement education policies to each of the states in the union. No national laws are enacted for the purpose of establishing a prescribed curriculum, the recognition of various professions and degrees, the legal status of faculty members and students, or institutional governance. The functions of the U.S. Education Department do not include them.

Creation and administration of education policy starts at the state and spills down to local and institutional levels. This includes laws on school safety and health, formulation of curriculum guidelines, creation and development of public education policies for both primary and secondary levels, appointment of boards and agencies to oversee the administration of public education, and others. The respective state legislature and state boards of education are usually responsible for developing policies on education that are implemented by the states' education departments.

Although state boards of the different states may have a lot of similarities in terms of their functions, and are composed of prominent citizens of the state, they may be formed in various ways. In some states, they are appointed by the governor or the legislative branch. In other states, they are selected by the people through general elections.

State boards in most states are responsible only up to the secondary level, while in some states, the responsibility extends to all levels of education. They perform oversight functions on educational policies. The state board (or the governor) appoints the state superintendent, the highest-ranking education official in the state who manages the day to day activities of the education department.

The Russian Education System

Unlike the U.S., Russia has a centralized education system the direction of which is determined by a specific national policy. Compulsory curriculum guidelines for all public schools are established and implemented by the "Federal Ministry of Education, Science, and Social Development." There are, however, some state-financed experiments that are being introduced such us bi-lingual schools that teach the students' native dialect. These initiatives are appreciated and allowed by the federal governors.

Although there are also government-initiated grants and programs such as those for talented and gifted students as well as those for differently-abled individuals, these efforts pale in comparison to those offered in the U.S. The Russian programs are also sometimes not properly disseminated because of lack of funding. U.S. government initiatives, in contrast are well-funded and popular in terms of information and availments.

Just like in the U.S., school choice is also provided in Russia although the initiative is less popularly known in the former Soviet republic. As opposed to the assignment by local school district on which schools children are placed based on residence, the educational reform on school choice gives parents the freedom for parents to enroll their kids in the school they prefer. Although Russian children are initially assigned the schools they should go to, they are now allowed to enroll elsewhere.

The education systems of both the U.S. and Russia were established based on tradition and historical background which explains some things that are unique in each of them. The systems evolve based on the current needs and conditions.

- Accreditation and Quality

- Mobility Trends

- Enrollment & Recruiting

- Skilled Immigration

- Asia Pacific

- Middle East

- Country Resources

- iGPA Calculator

- Degree Equivalency

- Research Reports

Sample Documents

- Scholarship Finder

- World Education Services

Education System Profiles

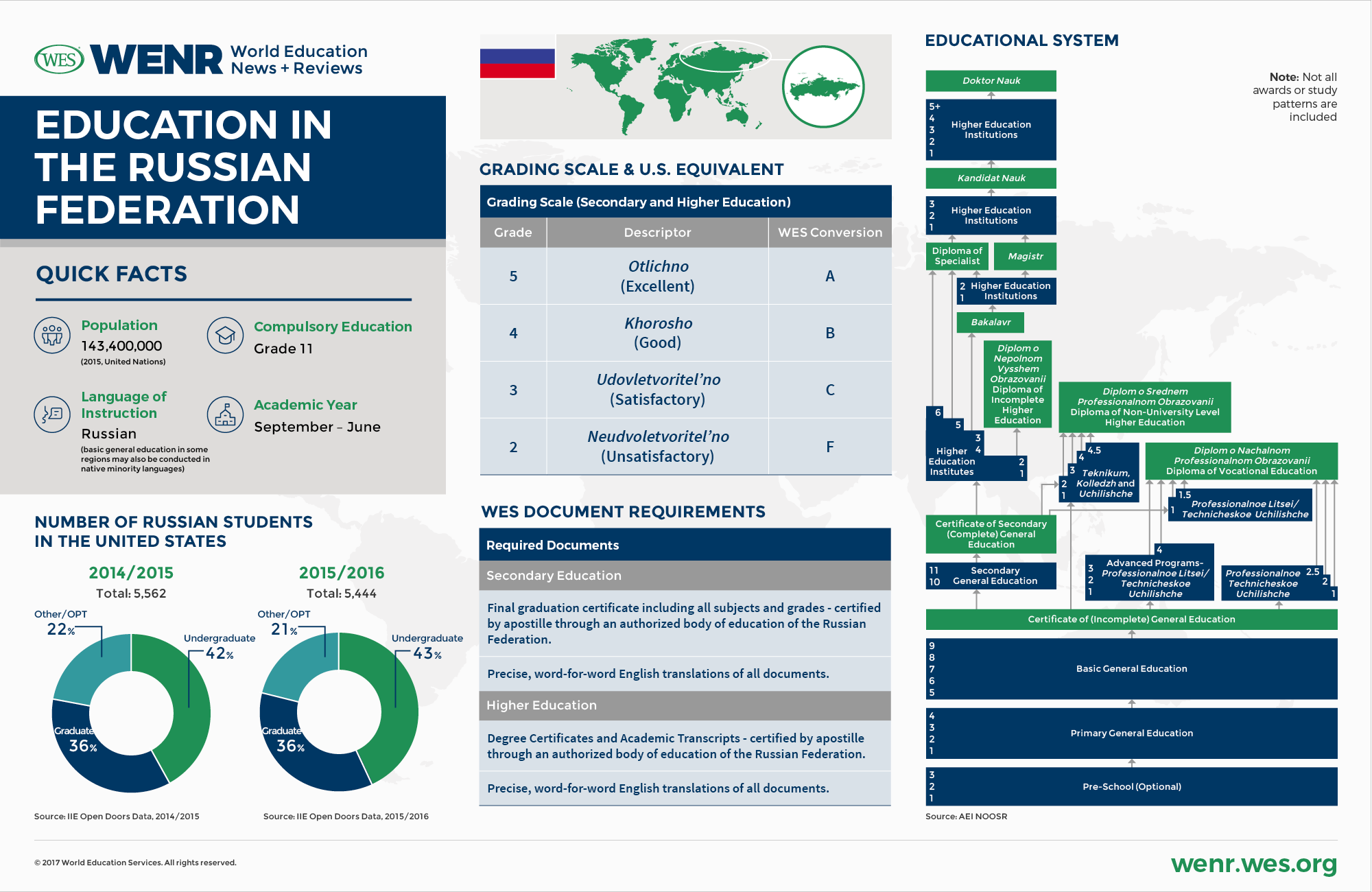

Education in the russian federation.

Elizaveta Potapova, Doctoral Candidate, Central European University, and Stefan Trines, Research Editor, WENR

This article describes current trends in education and international student mobility in the Russian Federation. It includes an overview of the education system (including recent reforms), a look at student mobility into and out of the country, and a guide to educational institutions and qualifications.

The Russian Federation, more commonly and simply known as “Russia,” is a complex, heterogeneous state. Home to some 143.4 million citizens, its population includes a sizable number of ethnic minorities besides the Russian majority. Most citizens consider their mother tongue to be Russian. However, up to 100 other languages, including 35 that are “official,” remain in use. Russia, the largest nation in the world in terms of landmass, shares borders with 14 neighbors: Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, North Korea, and China.

The Federation, like the Soviet Union before it, is a nominally federal system that consists of 85 “federal subjects,” including “republics,” “oblasts” (provinces), “krais” (districts), and “cities of federal importance.” However, Russia is not a truly federal system. Because of the re-centralization of power under the rule of Vladimir Putin, Russia is often referred to as a “quasi-federal” state, or a system that is “ unitary in function .” The autonomy of provinces, republics, districts, and cities of federal importance is limited.

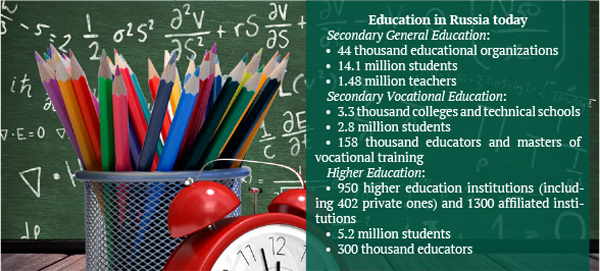

Some 54 percent of 25- to 64-year-old Russians held tertiary degrees as of 2015, making the country one of the most educated in the world. However, its higher education system – especially its universities are in need of modernization , particularly in terms of research, which is deemed to be lagging . As of mid-2017, the country faces a range of pressures that are affecting its education system, especially at the tertiary level. Among these are:

- Economic challenges: In recent years, the Russian government has enacted deep spending cuts across the board. Economic sanctions, deteriorating exchange rates, and a decline in the price of oil , Russia’s main export, have led to severely decreased revenues and tightened governmental spending in multiple sectors. According to government data , federal spending on education decreased by 8.5 percent between 2014 and 2016, from 616.8 billion rubles to 564.3 billion rubles (USD $10 billion).

- Demographic pressures: The number of college- and university-age students in Russia has plummeted in recent years. Today, the country’s demographic crisis is so profound that the Russian parliament radically loosened citizenship requirements in recent months . Population decline has motivated the Russian government to stimulate the immigration of skilled workers and position the country as an international higher education destination. The decline, expected to cut tertiary enrollments by as much as 56 percent between 2008 and 2021, has also played a role in the proposed closure and merger of many universities.

- Lingering corruption: Weak government institutions were a hallmark of the years immediately following the Soviet era. Many forms of systemic corruption went unchecked for years. As of 2017, Russia is ranked 131 st out of 176 countries on the 2016 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index . In 2016, Russia’s general prosecutor recorded 32,824 corruption crimes , and estimated that corruption deprived the government of revenues totaling $USD 1.3 billion in that year alone – likely a lowball estimation, given that officially reported cases only represent a fraction of all instances of corruption. The higher education system is particularly vulnerable to corruption : Instructors at poorly funded universities are routinely underpaid. Ambitious students, meanwhile are seeking academic advancement and, upon graduation, improved employment prospects; many are willing to pay instructors for better grades, revised transcripts, and more. Efforts to stem admissions-related and other forms of corruption are in place, but have so far had mixed results. (See additional detail below.)

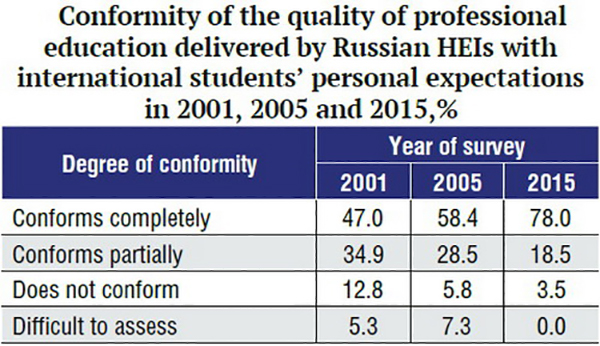

Still, the Russian government has pushed an ambitious higher education agenda focused on improving quality and international standing. The country is seeking to radically enhance the global ranking of its universities by 2020 and to attract substantial numbers of internationally mobile tertiary-level students from around the globe. At the same time, the government has actively sought to send scholars abroad – and incent them to return home as part of a broader effort to modernize the flagging economy.

This article seeks to provide an overview of the education system in Russia, especially at the tertiary level. It provides a broad context for understanding the current state of higher education in Russia; analyzes inbound and outbound mobility trends; provides a brief overview of the education system from the elementary through higher education levels; and addresses issues of quality and accreditation. It also provides a number of sample documents to help credential evaluators and others familiarize themselves with the appearance of authentic academic documents from the federation.

Economic Trends: A Recession Drives A Push for a Modernized Economy

Throughout 2015 and 2016, Russia experienced a recession that can be traced to two primary root causes: Economic sanctions imposed by Western countries in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its military intervention in Ukraine, and the decline of crude oil prices. Oil exports accounted for more than 50 percent of the value of all Russian exports in 2013. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev warned as early as 2009 that Russia needed to reduce its economic dependence on commodities and modernize, and technologically upgrade Russian industries in order to sustain economic growth. The economic fallout of the recent price decline has laid bare the country’s dependence on energy exports, giving new urgency to efforts to modernize the Russian economy.

Demographic Trends: Declining Birth Rates Affect the Higher Education System

Demographic trends have had a profound effect on the Russian Federation , not least its university system. The number of secondary school graduates dropped by about 50 percent between 2000/01 and 2014/15, from 1.46 million to 701,400 graduates . The number of students enrolled in tertiary education institutions, likewise, decreased from 7.5 million students in 2008/09 to 5.2 million in 2014/15 and is expected to further decline to approximately 4.2 million students by 2021 . The United Nations estimates that the Russian population will shrink by 10 percent in the next 35 years, from 143.4 million people in 2015 to 128.6 million in 2050 ( medium variant projection , 2015). According to the World Bank, Russia’s labor force shrinks by an estimated one million workers annually due to aging, and that aging will drain pension funds while increasing public debt . Further compounding labor shortages is a net outmigration of scientists and highly skilled workers, even though current outmigration rates remain a far cry from the massive brain drain that Russia experienced shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In the near term, these pressures may ease, at least in the education system. After sharp declines in the 1990s, Russia’s birth rates have, since the 2000s, rebounded , and current increases in fertility rates have given some observers cause for optimism. However, most analysts maintain that current fertility rates remain too low to stem overall population decline, and that demographic pressures remain one of Russia’s biggest economic challenges .

Reforms, Mergers, and University Closures

Declining student enrollments have coincided with a decrease in the number of Russian higher education institutions. In 2012, the government initiated a process of reforms and consolidation that had, by 2017, already reduced the number of institutions by more than 14 percent, from 1,046 accredited tertiary institutions in 2012/13 to 896 in 2016. In 2015, it announced that it intended to close or merge as many as 40 percent of all higher education institutions by the end of 2016, with a particular focus on the private sector. It also intended to reduce the number of branch campuses operated by universities by 80 percent. It is presently unclear, however, to what extent these cuts will go forward. In late 2016, Russia’s newly appointed minister of education suspended the mergers because of resistance from affected universities.

Other objectives included modernization and the effort to shift education and to focus on technical innovation: Simultaneous to the cuts among existing universities, plans were announced to create up to 150 new public universities specializing in technological innovation and high-tech in order to improve Russia’s international competitiveness. In 2012, Russia also established a “Council on Global Competitiveness Enhancement of Russian Universities” and launched the so-called 5/100 Russian Academic Excellence Project , an initiative that provides extensive funding for a group of 21 top universities with the goal of strengthening research and placing five Russian institutions among the top 100 universities in global university rankings by 2020 . The initiative also seeks to shift the mix of students and scholars on Russian campuses, pulling 10 percent of academics and 15 percent of students from abroad .

International Student Mobility

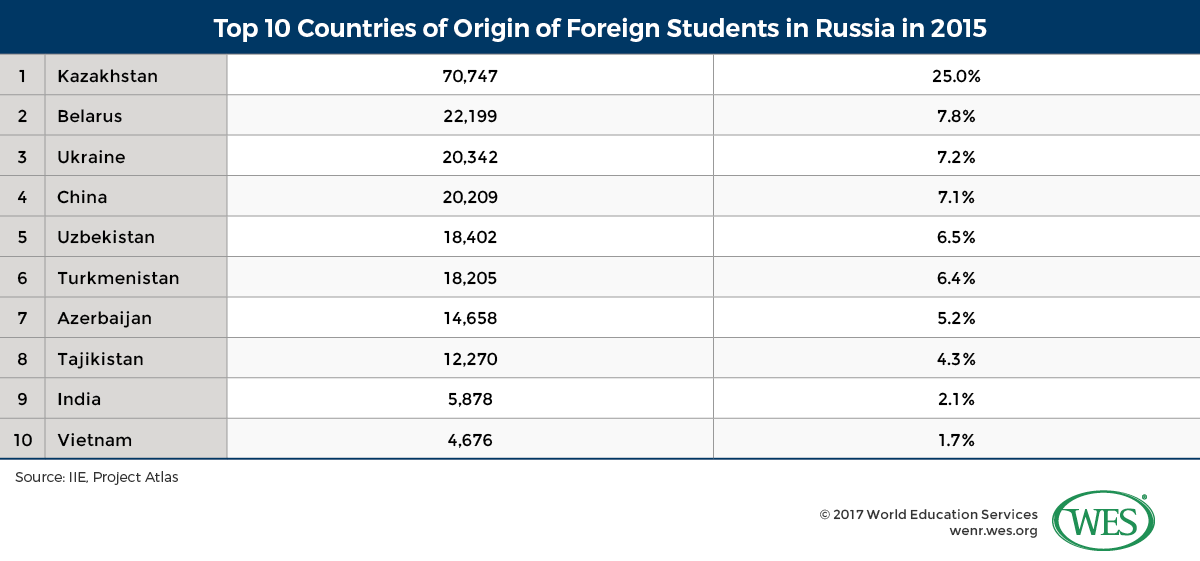

Inbound mobility.

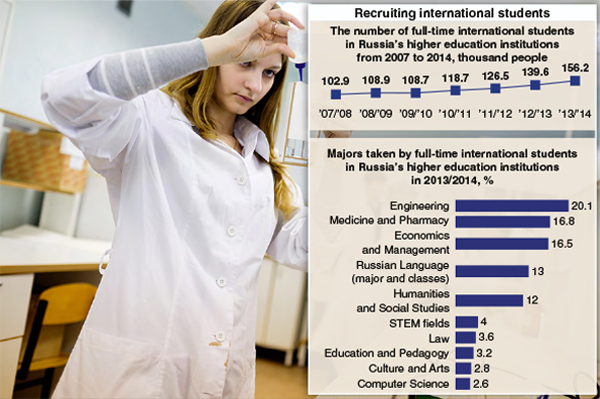

Foreign student quotas are seen as a measure of the effectiveness of higher education institutions, and the Russian government has, as part of its effort to boost the rankings of its universities, made it a priority to boost international enrollments. In 2015, Russia raised the international student quota at Russian universities by 33 percent . It also significantly increased the scholarship funds available to foreign students. That same year, a number of top Russian universities included in a newly-founded Global Universities Association to jointly recruit at least 15,000 international students to Russian annually .

The majority of foreign students in Russia are enrolled in undergraduate programs at public universities. Beyond that, the trends in inbound mobility and the reasons behind them vary, depending on students’ place of origin.

- Former Soviet Republics : Geographic proximity, linguistic and economic ties make Russia the top destination of mobile students in the majority of post-Soviet Republics, where most students speak Russian as a second language. The Russian government encourages regional student exchange in an attempt to expand influence and “soft power” in other former Soviet Republics. Thus, the vast majority of foreign students in Russia, more than 60 percent, come from these countries. The three top sending countries in 2015 were Kazakhstan, which accounted for 25 percent of all students, Belarus (7.8 percent), and Ukraine, accounting for 7.2 percent.

- China: The number of Chinese students enrolled at Russian universities has increased considerably in recent years, and in 2015, China became the fourth-largest sender of international students to Russia, accounting for 7.1 percent of enrollments. Governments on both sides have in recent years taken steps to boost student exchange , and many Russian universities are expanding their recruitment efforts in China. Efforts include dual degree programs and the establishment of Russian language learning centers in China. Russia offers Chinese students a low-cost alternative compared to Western countries like the U.S., and enrollments can be expected to rise in the years ahead. (Geographic proximity is another factor.) At the same time, the inflow of Chinese students is impeded by language barriers, since most education programs in Russia are taught in Russian.

- Other Asian countries : India and Vietnam are other Asian countries that send significant numbers of international students to Russia. Enrollments from outside of Asia, by comparison, are small. European countries (excluding Turkey, Moldova, Ukraine, and Belarus) in 2014 only accounted for about one percent of international degree students in Russia, more than half of them from the Baltic States.

In 2014, students from Africa and the Americas respectively made up only about two percent and less than one percent of the total international student population.

Outbound Mobility

As of 2017, Russia’s government encourages Russian students to further their education abroad. In 2014, the government introduced a Global Education Program that seeks to facilitate human capital development in Russia and remedy shortages of skilled professionals by funding Russian graduate students at 288 selected universities abroad. Some 72 are located in the United States. The program is intended to support up to 100,000 Russian citizens over a time period of ten years and targets master’s and doctoral students in disciplines, such as engineering, basic sciences, medicine, and education. It covers students’ tuition costs and living expenses up to 2.763 million rubles (USD $48,372) annually. At the same time, the government is seeking to curtail outmigration. Grant recipients are required to return to Russia within three years to take up employment in a number of select positions, mostly in the public sector.

As of recently, such scholarship programs appear to be bearing fruit. Between 2008 and 2015, UIS data indicates that the number of outbound Russian degree students increased by 22 percent, from 44,913 to 54,923. This increase in mobility has likely been influenced by the rising cost of education in Russia, as high tuition fees have spurred students’ interest in the comparatively inexpensive universities of Central and Eastern Europe, for instance. The number of Russian applications in the Baltic countries, Poland and the Czech Republic, as well as China and Finland, has reportedly increased by 50 percent in recent years. Given Russia’s population size, however, the overall number of degree students going abroad is still quite small and makes up just about 1 percent of Russia’s 5.2 million tertiary students (2015).

The most popular destination choice among Russian degree students abroad in recent years has been Germany, where 18 percent of outbound students were enrolled in 2015 (UIS). The U.S., the Czech Republic, Great Britain, and France were the next popular choices, accounting for 9 percent, 8 percent, and 7 percent of enrollments, respectively.

China, Russia’s neighbor and an increasingly important international education provider, is another notable destination. UIS data, which tracks degree-seeking students only, does not rank China as a top-50 study destination. But China is presently ranked as the number one destination of Russian students if non-degree candidates are included in the count. According to the Project Atlas data , 21.6 percent of outbound Russian students studied in China in 2015, reflecting the strong growth in exchange programs, language training programs, and internships that has accompanied the strengthening of Sino-Russian cooperation in recent years.

Russian student mobility to the U.S. is, by comparison, anything but booming. After peaking at a high of 7,025 students in 1999/2000, the number of students has fluctuated over the past decades. The country has not been among the top 25 sending countries since 2012 (IIE, Open Doors). In 2015/16, 5,444 Russian students were enrolled at U.S. institutions, a decrease of 2.1 percent over 2014/15. In Canada, on the other hand, Russian enrollments have been mostly increasing in recent years – the number of students grew by more than 200 percent between 2006 and 2015, from 1,252 to 3,892 students, according to the data provided by the Canadian government .

Transnational Education: A Different Kind of Internationalization

Compared to countries like China or the United Arab Emirates, Russia is not a major host of foreign universities or branch campuses. The global branch campus directory maintained by the “Cross-Border Education Research Team” (C-BERT) lists only one wholly foreign-owned provider in Russia: the U.S.-based Moscow University Touro . There are a number of other foreign institutions licensed to operate in Russia, such as the “ Stockholm School of Economics Russia ,” as well as transnational partnerships like the “ German-Russian Institute of Advanced Technologies ,” but the overall number of such ventures is still relatively small.

On the other hand, Russia is a major player in transnational education (TNE) in post-Soviet countries, where Russian state universities currently operate 36 branch campuses , most of them located in Armenia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Unlike in countries like Australia or the UK, where TNE is primarily driven by private providers, TNE in Russia is directed by the government and presently pursued vigorously. Despite charges by the previous Minister of Education in 2014 that education at cross-border campuses was of poor quality and should be suspended, President Vladimir Putin in 2015 instead vowed to strengthen TNE in countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), where Russia is already the predominant TNE provider.

One of the reasons the Russian government is pursuing TNE is that international education is a major element in Russia’s soft power strategy in the “near abroad” aimed at fostering “economic, political and socio-cultural integration in the post-Soviet space .” This objective is formalized in the role of a government agency called Rossotrudnichestvo (Federal Agency for the CIS), which was set up to promote Russian higher education abroad, support Russian institutions located in foreign countries, and popularize Russian culture and improve the image of Russia in the CIS.

In Brief: Russia’s System of Education

Administration.

Federal Law №273 on education (2012) provides the core legal framework for the Russian education system. The Federal Ministry of Education is the executive body responsible for the formulation and implementation of education policies at all levels. Under its purview is the Federal Education and Science Supervision Agency, which is tasked with the supervision and quality control of educational institutions. Regional Ministries of Education are responsible for policy implementation at the local level.

General Education

General education in Russia comprises pre-school education, elementary education, lower-secondary, and upper-secondary education. The course of study takes 11 years in a 4+5+2 sequence. Four years of elementary education are followed by five years of lower-secondary education, which are followed by two years of upper secondary schooling. In addition to general academic programs, students can enroll in vocational-technical programs of varying lengths at the upper-secondary level (discussed further below).

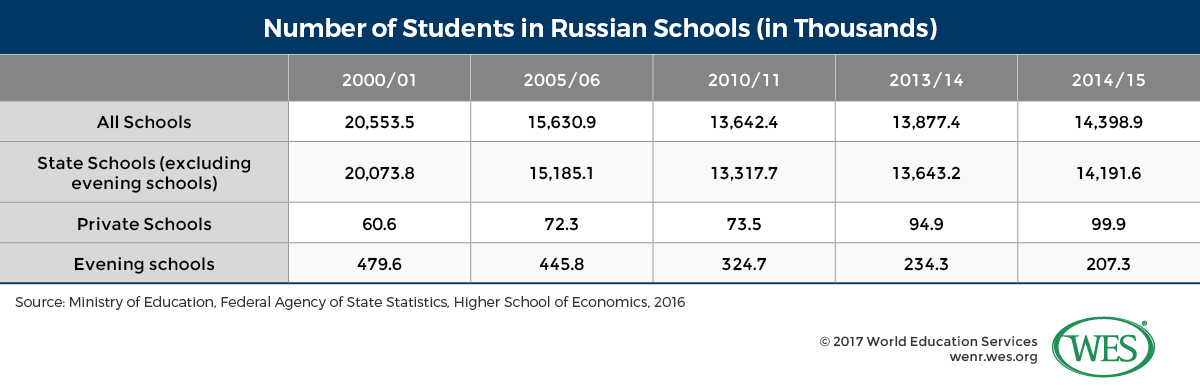

Education has been compulsory until grade 11 since 2007 (until then, it was only compulsory until grade 9), and access to general education is a guaranteed right of every Russian citizen, according to article 43 of the constitution . Schooling is provided free of charge at public schools; private schools are also available, although in limited numbers. Private schools in Russia only reportedly accounted for about 1 percent of all 42,600 schools that existed in Russia in 2015.

The overall number of pupils enrolled in the Russian school system has decreased considerably over the past decades as birth rates have declined. They dropped by more than 32 percent between 2000 and 2013, from 20.5 million to 13.9 million students. Only in the last few years have enrollments started to grow again, reaching 14.6 million students in 2015/2016. The trend has been driven by an increase in birth rates beginning in the 2000s.

Participation and completion rates in general education are high. The net enrollment ratio at the elementary level was 95.2 percent in 2014, according to the World Bank . In 2011, 94 percent of 25-64 year-olds had completed at least upper-secondary education (compared to an average of 75 percent in the OECD and a 60 percent average among G-20 countries). Youth literacy is universal and has held steady at 99.7 percent since 2002, as per UIS data.

Types of Schools: Lyceums, Gymnasiums, Schools for the Gifted and Talented

Most Russian schools incorporate all stages of general education, from elementary to upper-secondary school. However, there are a number of schools that only provide elementary or lower-secondary education, mostly in more rural regions. Other schools only provide upper-secondary education. Evening schools, known as “schools for working youth” in Soviet times, for example, deliver upper-secondary education to students who completed compulsory education (grade 9, until 2007), but want to continue their education or prepare for tertiary education. These schools are attended by both children above the age of 15 and adults who want to further their education.

Other types of schools include lyceums, gymnasiums, schools for the gifted and talented, and general schools. All of these schools teach the general academic core curriculum, but some offer curricular specializations and are more selective. For instance:

- Lyceums offer specialized programs in a variety of disciplines, including sciences, mathematics, or law, and many of these schools are affiliated to universities.

- The gymnasium is a special type of school focusing on education in the humanities, including the study of two foreign languages.

- The schools for the gifted and talented are often associated with conservatories and fine arts universities and specialize in music, ballet, and performing arts, although some schools for gifted and talented children also exist in the sciences .

Education at lyceums, gymnasiums, and other specialized schools is of high quality; these schools are considered to be among the best secondary schools in Russia. An annual ranking of Russian schools conducted by the Ministry of Education included 160 lyceums and 175 gymnasiums among the country’s 500 best schools in 2016. Admission to the schools is typically competitive and may involve entrance examinations. Only about 16 percent of Russian pupils presently attend specialized schools and the availability of these schools tends to be limited in more remote provinces.

Elementary Education

Russian children enter elementary education at six to seven years of age. This stage of education lasts four years and includes instruction in the subjects of Russian language (reading, writing, literature), mathematics, history, natural sciences, arts and crafts, physical education, and a foreign language starting in grade two. Most classes are taught by one primary class teacher for the whole duration of the elementary cycle, although subjects like foreign language, physical education, music, or arts may be taught by specialized teachers. The school year runs from the beginning of September to the beginning of June. Completion of elementary education is a requirement for progression to the lower-secondary cycle, but there is no final centralized state examination as in the other stages of general education.

Lower-Secondary Education (Basic General Education)

Elementary school is followed by five years of lower-secondary education, called “basic general education” in Russia. Classes meet for 34 weeks a year and include 27 to 38 hours of weekly instruction. The federal government sets a general core curriculum of compulsory subjects, but within this framework schools have limited freedom in designing their own curricula at the local level.

Subjects studied in lower-secondary education include Russian language, foreign language, mathematics, social sciences (including history and geography), natural sciences, computer science, crafts (taught separately for girls and boys), physical education, art, and music. Students from Russian republics that have a language other than Russian as their official language have the right to study their native language in addition to Russian and can substitute Russian with their native language in the final graduation examination (a right that is guaranteed as per Russia’s education law).

The basic general education stage concludes with a final state examination, called Gosudarstvennaya Itogovaya Attestatsia or GIA. The examination covers mandatory subjects – Russian and mathematics – as well as elective subjects. Students who pass the examination are awarded the Attestat ob osnovnom obschem obrazovanii,’ commonly translated as “ Certificate of Basic Secondary Education ” or “Certificate of Incomplete Secondary Education.”

The certificate enables students to obtain entrance to secondary education, either along a general university-preparatory track or a vocational-technical track.

General Upper-Secondary Education

General upper-secondary education lasts for two years and includes a range of subjects similar to those offered at the lower-secondary stage. It prepares students for the Unified State Examination ( Ediny Gosudarstvenny Examen or EGE), which is a series of standardized examinations conducted in May/June of each year. The EGE functions both as a final graduation examination, as well as an entrance examination for higher education. High EGE scores are important for access to the limited number of tuition-free seats at Russian universities.

The EGE is overseen by the Federal Education and Science Supervision Agency ( Rosobrnadzor ) but administered by local authorities. All students sit for mandatory mathematics and Russian language exams. Since 2015, the exam in mathematics has been split into a “base examination” required for high school graduation, and a more advanced “profile examination” required for university admission. Students who do not wish to go to university can opt to only test in the base exam and Russian language. All students who pass are awarded a Certificate of General Secondary Education ( Attestat o srednem obshchem obrazovanii ) – a final graduation certificate. The certificate also lists the grades for all subjects studied during grades 10 and 11.

Students who fail the exam can sit for it a second time, but if they fail again, they do not qualify for the award of the “ Attestat ,” and only receive a certificate of study from their secondary school. Pass rates, however, are nearly universal. According to a recent report published by Rosobrnadzor , only 1.5 percent of students in 2015, and 0.7 percent of students in 2016 failed to reach the minimum threshold in the mandatory core disciplines, which in 2016 was 27 on a 100 point scale in mathematics, and 24/100 in Russian language .

In addition to the two compulsory subjects, students can elect to be tested in an unlimited number of “profile subjects” for admission into degree programs of their choice. The subject options include physics, chemistry, biology, geography, history, social studies, literature, foreign languages, and computer science.

University Admissions

Until recently, Russia’s universities made independent admissions decisions and did not necessarily factor in EGE performance. In 2009, however, the Russian government decided to make the use of the EGE in admissions mandatory. The impetus was twofold: to fight corruption in academic admissions, and to widen participation in higher education.

Prior to 2009, academic corruption challenges were particularly prevalent in university admissions. According to some reports, the total volume of bribes paid in connection to university admissions in Moscow in 2008 amounted to USD $520 million, with individual students paying bribes as high as $5,000 . The introduction of the EGE sought to take admissions decisions away from the universities, and replace them with objective external criteria.

The EGE also facilitates broader access to higher education. Before the introduction of the EGE, applicants often had to travel to universities across the country to sit for institutional entrance exams – a costly and time-intensive process that has now greatly improved. As per the Russian ENIC/NARIC, the EGE exam is now used in the admission of nearly 100 percent of applicants. Only two elite universities (Moscow State University and St. Petersburg State University) have been exempted and continue to administer their own admissions tests in addition to the EGE.

As of 2015, students could, according to Sergey Kravtsov , the head of the Federal Education and Science Supervision Agency, sit for the EGE examination in 5,700 testing centers throughout Russia, as well as in 52 countries abroad. A reported 584,000 students took the base stage EGE examination in 2016, and 492,000 sat for profile exams.

Upon passing the EGE exams, these students receive a certificate of results. These can be used to can apply to three different study programs at five universities at a time. Admission is competitive and based on test scores in the subjects required for particular degree specializations. Higher scores improve the chances of admission into top universities.

Certain programs that require special creative or physical abilities, for example, in artistic disciplines, sports, or military sciences, may require additional entrance examinations. Foreign students are admitted based on separate institutional admissions requirements, and typically have to take the Test of Russian as a Foreign Language (TORFL).

Academic Corruption in the EGE and Beyond

Russia is afflicted by a widespread culture of academic fraud. The introduction of the centralized EGE exam has reduced the use of direct bribes for university entrance but has reportedly led to significant test-related fraud, including, prior to the test, distribution of exam questions, and after the test, revision of incorrect answers .

Fraud is prevalent in graduate admissions as well. In one notorious example, a senior lecturer at Moscow State University was in 2010 caught accepting a bribe of €35,000 (USD $39,140) to guarantee admission to the faculty of public administration. The sale of fake degrees and the ghost-writing of papers and dissertations constitute another problem. Some experts reportedly claim that as many as 30 to 50 percent of doctoral degrees circulating in certain disciplines like law and medicine may either be fake or based on plagiarism, while other researchers assert that 20 to 30 percent of all Russian dissertations completed since the fall of the Soviet Union were purchased on the black market . The use of such suspect degrees is blatant, and not uncommon among politicians and higher-level civil servants. A 2015 study of the Dissernet Project , an organization dedicated to exposing academic fraud, found that one in nine politicians in the lower house of the Russian parliament had a plagiarized or fake academic degree . In 2006, researchers from the U.S. Brookings Institution analyzed the dissertation of President Vladimir Putin and alleged that it was plagiarized .

Vocational and Technical Education

Russia’s education system includes both secondary-level and post-secondary vocational programs, as well as programs that straddle secondary and higher education. As of the 2012 adoption of Russia’s latest federal education law, all of these programs are now primarily taught at the same types of institutions called technikums ( tehnikum ), and colleges ( kolledzh ). The professional-technical uchilische (PTU) and professional-technical lyceums (PTL) that existed prior to 2012 were largely upgraded to, or merged with, technikums and colleges.

Basic vocational programs at the secondary level are entered on the basis of the Certificate of Basic Secondary Education (grade 9) and are between one and four years in length. Programs have a focus on applied training but may also cover the general secondary education curriculum. Students who have completed general upper-secondary education can enroll in shortened versions of these programs, which are typically one to 1.5 years in length. The final credential is the Diplom o Nachalnom Professionalnom Obrazovanii (Diploma of Vocational Education). It gives access to higher-level vocational education programs and specialized employment, mostly in blue-collar occupations, such as carpentry, tailoring, cookery, or automotive technology. Graduates from programs that include a general secondary education component have the option of sitting for the EGE university entrance exams.

The popularity of basic vocational education declined rapidly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The fact that employment was more or less mandatory during Soviet times meant that 98 percent of graduates from basic vocational programs were employed in the Soviet Union. Today, employment prospects are more precarious. The number of graduates from lower-level vocational programs has declined by 43 percent between 2000 and 2013 alone, from 762,800 to 436,000, as per the statistical data provided by the Russian government.

Advanced vocational programs, referred to as “middle level professional education” in Russia, are considered (non-tertiary) higher education. They typically last two to three years after upper-secondary school (grade 11). Students who have not yet completed upper-secondary education, however, may enter these programs after grade 9 if they meet certain additional admissions requirements. They may, for instance, have to pass admissions tests, and are required to complete the general secondary education curriculum as part of the program. Advanced vocational programs combine applied training with theoretical instruction, and usually require the preparation of a written thesis. The final credential is called Diplom o srednem professionalnom obrazovanii, which can be translated as “Diploma of Middle Level Professional Education.”

The Diploma of Middle Level Professional Education continues to serve an important function in the Russian education system, even though enrollments have begun to decline, if at smaller margins than those in basic vocational education. The credential certifies formal training in a wide range of occupations, ranging from technician to elementary school teacher to accountant. Nurses in Russia, for example, can work after completing mid-level professional education rather than earning a bachelor’s degree, as is required for licensure in the United States.

Mid-level professional education also aligns with tertiary education in that graduates may, on a case-by-case basis, be granted exemptions towards university programs in similar disciplines, and may be allowed to enter directly into the second or third year of bachelor’s programs at some universities.

Tertiary Education

Institutions.

In 2015/16, there were a total of 896 recognized tertiary education institutions in operation in the Russian Federation. Public institutions are categorized into :

- Big multi-disciplinary universities

- Academies specialized in particular professions, such as medicine, education, architecture, or agriculture

- Institutes that (typically) offer programs in singular disciplines, such as music or arts.

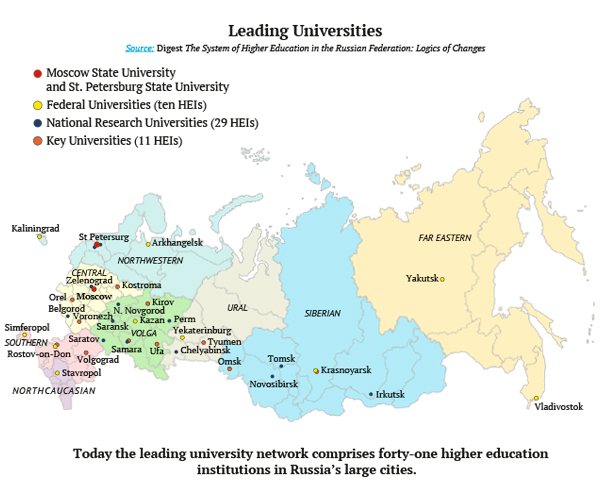

There are 50 specially-funded and research-focused National Research Universities and Universities of National Innovation, as well as nine Federal Universities, which were established to bundle regional education and research efforts and focus on regional socioeconomic needs in more remote parts of Russia.

Finally, there are two National Universities, the prestigious Lomonosov Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University. These well-funded elite institutions have special legal status and are under the direct control of the federal government, which appoints their rectors and approves university charters. Moscow State University is arguably Russia’s most prestigious institution and currently enrolls more than 47,000 students. Modeled after German universities, it was founded in 1755.

Private Universities

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 brought about the de-ideologization of education, and successively replaced the rigid centralization and state planning of the Soviet Union with new paradigms of institutional autonomy, effectiveness, innovation, and internationalization. In contrast to other sectors, the education system, however, was spared the “ shock-therapy ” of economic liberalization, which brought about what has been described as “the most cataclysmic peacetime economic collapse of an industrial country in history.” There was no large-scale privatization of state universities and the overall structure of the education system remained largely intact. Over time, however, Russia has seen the emergence of a healthy private higher education sector following the legalization of private education in 1992.

Private institutions now account for some 366 accredited institutions – just over one-third of all higher education institutions in Russia. The number of students enrolled in these universities has increased considerably over the past decades – between 2000 and 2014 alone the number of students at private universities grew by 88 percent, from 470,600 to 884,700 students .

Today, private universities tend to supplement public education with more specialized niche offerings, rather than compete directly with the bigger state-funded universities. Private enrollments account for only about 16 percent of all tertiary enrollments. And, as demonstrated by prestigious funding projects for state universities, and the closure of private niche universities , the Russian government does presently not prioritize the development of the private sector. Private education, thus, is for the time being expected to primarily gain traction in the “ sphere of non-formal and extra-system education .”

Rankings and International Reputation

The Russian Ministry of Education maintains a webpage dedicated to tracking the progress of Russian universities in global rankings. As of 2016 rankings, the goals of the 5/100 project to place five Russian universities in the top 100 of global rankings still seem distant. Lomonosov Moscow State University was the only Russian university among the top 100 in the most common rankings. It was ranked at 87 th place in the Shanghai ranking (followed by St. Petersburg State University and Novosibirsk State University at 301-400 and 401-500, respectively). In the Times Higher Education Ranking , Lomonosov reached 188 th place in 2016/17 with no other Russian universities among the top 300. In the QS ranking , Russia’s flagship university reached 108 th place followed by St. Petersburg State University ranked at place 258. Of note is also that Russia in 2016 announced that it will launch its own international ranking , including universities from Russia, Japan, China, Brazil, India, Iran, Turkey, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

Funding and Education Spending

As a result, education has become more expensive for many students, even in the public sector. Students with high EGE scores are usually allowed to study for free; however many students pay annual tuition fees averaging 120-140 thousand rubles (USD $2,084 to $2,432) for a bachelor’s degree and 220-250 thousand rubles (USD $3,822-4,343) for a Specialist degree (described in more detail below). Although students can take out low-interest loans, these costs are high considering Russian income levels. Inflation rates of more than 11 percent in 2014 caused many Russian universities to raise tuition fees by significant margins , while the average monthly income simultaneously dropped by 35 percent to USD $558 in 2015.

As noted earlier, federal spending on education decreased by 8.5 percent between 2014 and 2016. This downturn reverses spending increases in previous years. Between 2005 and 2013, overall Russian higher education spending as a percentage of GDP increased from 2.7 percent in 2005 to 3.8 percent in 2013 . In the tertiary sector, spending levels stayed mostly constant between 2005 and 2013, but because the number of students simultaneously declined, the amount spent per student actually rose by 32 percent to $USD 8,483 . This number, however, is still low when compared to the average spending in countries at comparable levels of development, causing observers like the World Bank to recommend that Russia increase education spending and prioritize human capital development in order to ensure sustained and inclusive economic growth.

Quality Assurance: State Accreditation and the Role of the Bologna Process

All higher education institutions in Russia, public or private, must have a state license to deliver education programs. To award nationally recognized degrees, institutions must also obtain state accreditation. The accreditation process is overseen by the Federal Service for Supervision in Education and Science ( Rosobrnadzor) and is based on institutional self-assessments, peer review, and site visits certifying compliance with standards set by Russia’s National Accreditation Agency (subordinated to Rosobrnadzor) .

Accreditation is granted for six-year periods and entitles institutions to award state-recognized diplomas in a set number of disciplines, and to apply for funding by the government. Both the National Accreditation Agency and Rosobrnadzor maintain online databases of accredited institutions and the degree programs they are authorized to offer.

A signatory to the Bologna declarations since 2003, Russia has adopted many of the quality assurance provisions stipulated in the declarations. Internal quality assurance systems have been established at most of Russia’s universities , and there are now at least five independent accreditation agencies operating in Russia. These agencies accredit programs and institutions in disciplines such as engineering and law, but accreditation by these agencies is not mandatory and does not replace existing quality assurance mechanisms, which remain strictly based on institutional accreditation by the government. Accreditation by European agencies, including those registered with the European Quality Assurance Register (EQAR) is presently not recognized by the Russian government.

Threats to Academic Freedom: The Case of the European University in St. Petersburg

Under the rule of Vladimir Putin, Russia has become an increasingly authoritarian country in which the government suppresses journalistic and academic freedoms. Threats to academic freedoms are also on the rise in other European countries like Hungary, where the government is trying to shut down the Central European University founded by U.S. billionaire philanthropist George Soros (see our related article in this month’s issue). In Russia, another Soros-supported Western-style university, the European University in St. Petersburg (EUSP) is facing a similar fate.

EUSP is an internationally renowned private graduate school specializing in social sciences that is regarded as one of Russia’s best universities. Founded in 1994, EUSP received state accreditation in 2004, only to be closed in 2008 in what has been described as a case “ domestic ‘lawfare’ , in which state-run courts enforce political conformity through legal pretexts”. EUSP is known as a liberal-minded institution with foreign board members that teaches Western-style political science. The 2008 closure coincided with the award of a €673,000 EU grant to EUSP to improve election monitoring in Russia, after which Rosobrnadzor inspected and cited the university with technical infractions, followed by temporary closure for not meeting fire-safety standards .

The university was reopened shortly afterward but continued to face difficulties. Passage of Russia’s “ law on undesirable organizations ” forced EUSP to forego foreign funding in 2015. In 2016, Rosobrnadzor launched another wave of inspections, citing the school with 120 violations , including the lack of a fitness room and an information stand against alcoholism, after a conservative Russian politician and a key-author of Russia’s “ gay propaganda law ” had logged a series of complaints , reportedly after hearing that EUSP was teaching inappropriate content in its gender studies curriculum . Other possible reasons suggested by the media involve interests in lucrative construction contracts for the building in which EUSP is housed. In March 2017, EUSP’s license was revoked . Appeals are currently working their way through the courts while the fate of the university remains uncertain.

Tertiary Degree Structure

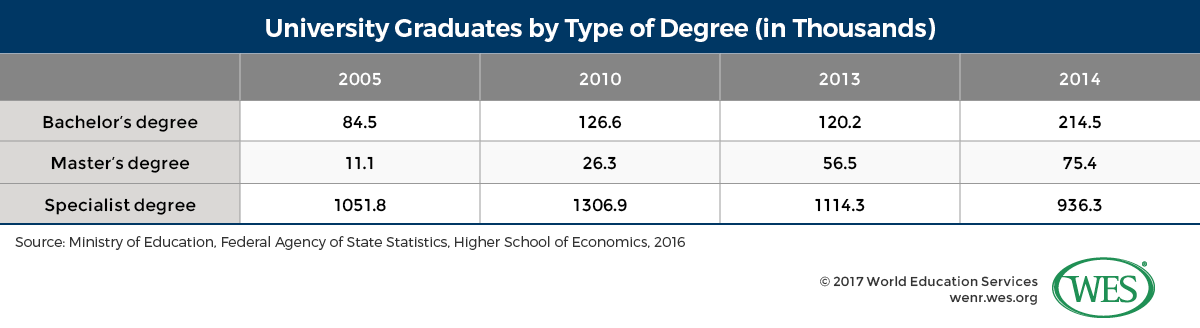

Prior to the introduction of the Bologna three-cycle degree structure in 2003, tertiary education in Russia consisted mainly of long single-cycle degree programs of five to six-year duration leading to the award of a “Diploma of Specialist,” followed by a doctoral research degree called Kandidat Nauk (Candidate of Science). In 2007, the single-cycle Specialist program was replaced with a two-cycle degree system consisting of an undergraduate Bakalavr (Bachelor) degree, and a graduate Magistr (Master) degree in many fields of study. In these fields, Specialist degrees are being phased out, and the last waves of students studying under the old structure are currently reaching graduation. However, implementation of the two-cycle Bakalavr/Magistr system has not been mandated across the board, and long Specialist degrees continue to be awarded in a number of fields, including the professions and technical disciplines. The three degrees still in common circulation are thus:

- Bakalavr : Bakalavr degrees in Russia are always four years in duration (240 ECTS credits). (In other European countries the length of bachelor’s degrees varies between three and four years.) Bakalavr degrees are awarded in a wide variety of disciplines and require completion of a thesis (prepared over a time period of four months) and passing of a final state examination in addition to coursework. Admission is based on EGE results in disciplines related to the major of the program.

- Magistr : Magistr degrees are research-oriented graduate degrees that are always two years in length (120 ECTS). Programs conclude with the defense of a thesis and state examination. Admission requires a Bakalavr degree, but universities are free to set additional admission requirements, including entrance examinations and interviews. Bachelor graduates that completed a degree in a different field of study generally have to pass an entrance exam to demonstrate proficiency in the intended area of study. Holders of Specialist degrees are also eligible for admission.

- Specialist Degrees : Specialist programs are at least five years in length and involve state requirements of approximately 8,200 hours of instruction, a thesis, and state examination. Programs lead to the award of the “Diploma of Specialist” and are generally considered to be professionally rather than academically oriented, although the Specialist degree has the same legal standing as the Magistr degree and gives full access to doctoral programs.

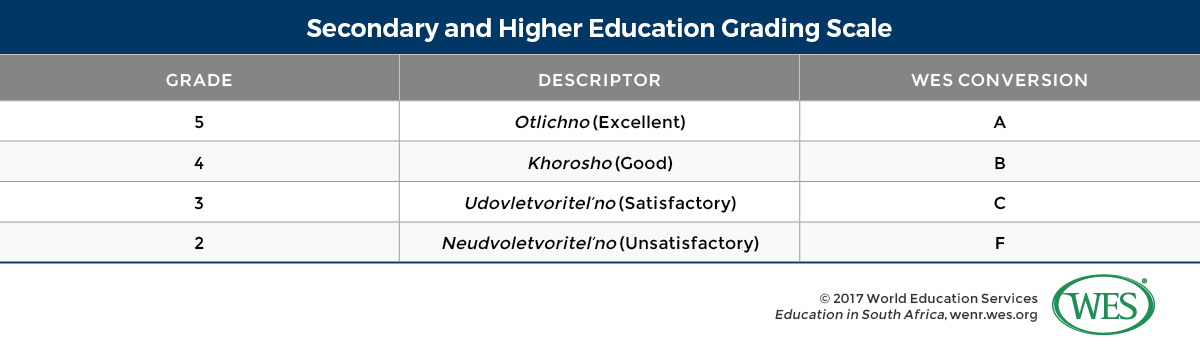

European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) credits are used in Bakalavr and Magistr programs, but, as of now, rarely in Specialist programs. The ECTS grading scale, as well as a new 0-100 grading scale, have been introduced in recent years, but are generally not used on state format academic transcripts, which continue to be issued using the standard 2 to 5 grading scale. Degree programs at both public and private universities conclude with state examinations and the defense of a thesis in front of a State Attestation Commission.

Diploma Supplements existed in Russia prior to the Bologna reforms, and are still issued for all Russian tertiary degrees.

Kandidat Nauk and Doktor Nauk

Students obtain entrance to doctoral research programs – or aspirantura – on the basis of Magistr or Specialist degrees. Doctoral programs are usually three years in length, including lectures and seminars, and independent original research. Upon completion of the study program, doctoral candidates are awarded a diploma of completion of aspirantura . A final Kandidat Nauk degree is conferred only after the public defense of the doctoral dissertation.

Another type of doctoral program, the Doktor Nauk (Doctor of Science), requires additional study beyond the Kandidat Nauk . It is a higher doctorate that entails the completion of another dissertation and takes most candidates anywhere between five and fifteen years to complete. The Doktor Nauk is required to obtain full-tenured professorship in Russia, as well as the prestigious rank of “Professor of the Russian Academy of Sciences.” Full tenure is otherwise only granted to professors with at least 15 years of outstanding teaching service at a university.

Teacher Education

Teacher training in Russia takes place both in post-secondary vocational education and the tertiary education sector, depending on the level. Pre-school and elementary school teachers are commonly trained at pedagogical colleges and are allowed to work as teachers on the basis of the Diploma of Middle Level Professional Education (although pre-school and elementary teacher training programs are also offered at universities). Secondary school teachers, on the other hand, are taught at universities and tertiary-level teacher training institutes. Upper-secondary school teachers are required to have a Specialist (or Magistr ) degree. Programs include academic study in the areas of teaching specialization, pedagogical and methodological subjects, and an in-service teaching internship.

Document Requirements

Russia is a signatory to the Hague Apostille Convention and officially certifies documents for use in other signatory states through government agencies. WES relies on this process in the authentication of academic documents from Russia.

Secondary Education

- Final graduation certificate including all subjects and grades – E.g. Certificate of (Complete) Secondary General Education ( Attestat o Srednem (Polnom) Obshchem Obrazovanii including Prilozhenie or Tabel ) – Certified by apostille through an authorized body of education of the Russian Federation. (See here for a list of appropriate education authorities).

- Precise, word-for-word English translations of all documents

Post-Secondary and Higher Education

- Degree Certificate and Academic Transcript – Certified by apostille through an authorized body of education of the Russian Federation. See here for a list of appropriate education authorities.

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- Attestat o srednem obshchem obrazovanii (Certificate of General Secondary Education)

- Diplom o srednem professionalnom obrazovanii (Diploma of Middle Level Professional Education)

- Diploma of Specialist

- Bakalavr (Bachelor)

- Magistr (Master)

- Kandidat Nauk (Candidate of Sciences)

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of World Education Services (WES).

References [ + ]

| 1 | As a result of the audit, most “inefficient” universities were merged with larger universities, and around half of the branch campuses were closed as per . |

|---|---|

| 2 | Student mobility data from different sources such as UNESCO, the Institute of International Education, and the governments of various countries may be inconsistent, in some cases showing substantially different numbers of international students, whether inbound or outbound, from or in particular countries. This is due to a number of factors, including data capture methodology, data integrity, definitions of ‘international student,’ and/or types of mobility captured (credit, degree, etc.). WENR’s policy is not to favor any given source over any other, but to try and be transparent about what we are reporting, and to footnote numbers that may raise questions about discrepancies. This article includes data reported by multiple agencies. |

| 3 | OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education: Country Background Report for the Russian Federation, , p.112. |

| 4 | It appears that the internship is currently being phased out and no longer a mandatory requirement as of 2017, as per Russian legislation. |

What others are reading What Others Are Reading

Education in the united states of america, education in the philippines, education in india, education in south korea.

Improve your grades with TutorChase

The world’s top online tutoring provider trusted by students, parents, and schools globally.

4.93 /5 based on 486 reviews

Preschool Education in Russia

Preschool education is not mandatory in Russia. However, over 80% of children aged 1-6 attend some form of preschool. The majority of these institutions are state-run and publicly funded, making preschool education either free or low-cost for Russian citizens. Foreign residents in Russia can also access public preschools, although they might need to navigate some additional administrative processes and limited availability. For instance, although public preschools in Moscow are generally available to foreign residents, they may need to fulfill additional proof of residence processes and compete for limited spots in popular areas. Therefore, some foreign residents opt for private or international preschools, which may offer programs better suited to their needs, such as bilingual education or a curriculum aligned with their home country’s education system.

Like elsewhere in the world, the curriculum in Russian preschools is designed to prepare children for not only the academic but also social environment of primary school, thus focusing on socialisation in addition to the development of motor skills, basic numeracy, language and creativity through a variety of activities.

Primary Education in Russia

Primary education in Russia begins at age 7 and lasts for four years, covering grades 1 through 4. This stage focuses on building a solid foundation in core subjects, ensuring that students acquire essential skills in reading, writing and mathematics. For local schools, the curriculum is standardised across the country, with students typically studying the Russian language, mathematics and introductory science.

Primary education in Russia is offered in both public and private schools. Public schools are the most common and are funded by the government, making them free for all students. These schools follow the national curriculum and are accessible to all children. Private schools, on the other hand, charge tuition fees and may offer additional programs, such as bilingual education or specialised subjects. They often have smaller class sizes and more resources, catering to families seeking a different or more tailored educational experience.

Key aspects of primary education in Russia include:

- Class Sizes: Typically, public school classes are relatively small, averaging 20-25 students per class, allowing for individual attention. Private schools often have even smaller classes.

- Daily Structure: The school day usually lasts four to five hours, with students attending classes five days a week.

- Assessment: Students are graded on a 5-point scale, where 5 is "excellent," 4 is "good," 3 is "satisfactory," and 2 is "unsatisfactory." Regular tests and homework assignments contribute to these grades, which reflect the students' understanding and performance in each subject.

- End-of-Stage Evaluation: While there are regular tests and homework throughout the primary years, there are no formal national exams at the end of primary school. Students are promoted to the next grade based on their overall performance throughout the year.

The primary school environment in Russia tends to be more formal and disciplined compared to Western countries. Teachers are highly respected, and there is a strong emphasis on order and adherence to rules. Unlike in some Western systems, where creativity and independent thinking are strongly encouraged from an early age, Russian primary schools often focus more on mastering the basics and developing good study habits. However, the environment is supportive, with teachers playing a crucial role in guiding students through this formative period.

International Education Options in Russia

Due to the limited international recognition of results in state exams, international schools have become more popular for expatriates and internationally-minded families. Russia offers a range of international education options, particularly in major cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg. According to ISC Research, there are over 50 international schools across Russia. These schools have the following characteristics:

- Language of Instruction: English is typically the primary language of instruction, with additional language support offered for non-native speakers.

- Accreditation: These schools are often accredited by international bodies, ensuring that their education standards are recognised globally.

- Tuition fees : International schools in Russia tend to have higher tuition fees compared to local schools, reflecting their specialised curriculums and smaller class sizes.

These schools provide globally recognised programmes such as the following key options:

- International Baccalaureate (IBDP): Available in several schools, offering a globally recognised diploma that is highly regarded by universities worldwide.

- British Curriculum (A-Levels and IGCSE ): Offered in British international schools, these qualifications are essential for students planning to attend universities in the UK and other Commonwealth countries.

- American Curriculum ( SAT Preparation): Some schools and tutors in Russia offer specific preparation for the SAT, focusing on students aiming for American higher education institutions.

This growing interest in international curricula also led to a rise in demand for specialised international curriculum tutors, such as IB tutors , both online and offline. They help students navigate the challenging curriculum. As more Russian students aim for higher education abroad, tutoring provides them with the skills and confidence needed to excel in an international academic environment.

"IB tutoring in Russia combines global standards with the rigour of Russian education, helping students excel academically and develop strong critical thinking skills," says Elena Ivanova, an experienced Physics tutor .

Vocational Education in Russia

Vocational education in Russia provides an option for students who prefer practical training over the traditional academic route. After completing basic general education, students can choose to study specific skills that are directly applicable to various trades and professions instead of further advancing to secondary generla education. They also have the option to choose a few years later, after they complete their secondary general education, to decide whether to go onto higher education or pursue vocational training.

Key aspects of vocational education in Russia include:

- Types of Institutions: Vocational education is provided by colleges (technikum) and vocational schools (uchilishche). These institutions offer programs that range from 2 to 4 years, depending on the field of study and the level of education completed by the student prior to enrollment.

- Curriculum: The curriculum in vocational schools is a blend of theoretical knowledge and hands-on training. Students spend a significant portion of their time working in workshops, laboratories, or real-world environments related to their field of study. Common areas of focus include technical trades (e.g., mechanics, electricians), service industries (e.g., hospitality, tourism), healthcare, and information technology.

- Certification: Upon completion of their vocational education, students receive a diploma or certificate that qualifies them for employment in their chosen field. These qualifications are recognised across Russia and are often highly valued by employers looking for skilled workers.

- Employment Opportunities: Graduates of vocational schools are well-prepared to enter the workforce immediately. Many programs are designed in collaboration with industry partners, ensuring that the skills taught are aligned with current market needs. This practical focus allows graduates to secure jobs more easily compared to their peers who follow a purely academic route.

- Transition to Higher Education: For students who wish to continue their studies, some vocational schools offer pathways to higher education. Graduates can enroll in universities or technical institutes, often receiving credit for the coursework completed during their vocational training.

Vocational education in Russia plays a vital role in the country's economy by providing a skilled workforce ready to meet the demands of various industries. It offers an alternative to the traditional academic path, giving students the opportunity to pursue rewarding careers in a shorter time frame.

Higher Education in Russia: Degrees and Institutions

Higher education in Russia is well-regarded globally, particularly in fields like engineering, natural sciences, and mathematics. The system is divided into several levels, with the most common degrees being the Bachelor’s , Specialist and Master’s degrees.

Key aspects of higher education in Russia include:

- Bachelor’s Degree: Typically a 4-year program, offering fundamental knowledge in a chosen field.

- Specialist Degree: Unique to Russia, this degree usually takes 5-6 years to complete and is more focused than a bachelor’s degree, often required for specialised professions like medicine, law and engineering. However, while the Specialist Degree is widely recognised in Russia and some other countries, it may be less recognised by Western Europe and North America.

- Master’s Degree: A 2-year program following a bachelor’s or specialist degree, allowing for deeper specialisation.

Russia is home to over 700 universities, with institutions like Lomonosov Moscow State University and Saint Petersburg State University consistently ranked among the top in the world. These institutions attract both domestic and international students, offering a diverse range of programmes across various disciplines. According to the Ministry of Education and Science, around 4 million students are currently enrolled in Russian higher education institutions.

Challenges and Strengths of the Russian Education System

The Russian education system is known for its strong emphasis on academic rigour, particularly in STEM subjects, which has historically produced experts in fields like mathematics, engineering, and science. This focus on a solid theoretical foundation is a significant strength, providing students with deep knowledge in core areas. Compared to international curricula like the IBDP, A-Levels, or IGCSE, the Russian system offers a more centralised and uniform approach, ensuring consistency across the country.

However, the system also faces notable challenges:

- Creativity and Innovation: The emphasis on standardisation and rote learning can sometimes limit opportunities for creativity and independent thinking, areas where Western education systems often excel.

- Resource Disparities: There is a significant disparity in resources between urban and rural schools, with the latter often facing outdated facilities and a shortage of qualified teachers.

- Pressure and Stress: The intense competition for university admission, particularly in prestigious institutions, places significant pressure on students, contributing to high levels of stress.

Despite these challenges, the Russian education system remains a robust framework that prepares students well for specialised academic and professional careers. However, there is an ongoing need for reforms to address the balance between academic rigour and fostering innovation and creativity.

Conclusion: The Future of Education in Russia

The Russian education system is known for its structured and disciplined approach, particularly in the early years, contrasting with the more relaxed styles often seen in Western countries. This strict environment helps students build a strong foundation in key subjects like literacy and numeracy. Despite this traditional focus, Russia also offers international education options, especially in cities, providing a diverse and globally relevant learning experience. This blend of discipline and flexibility equips students to succeed both locally and on the global stage.

Can international students study in Russian public schools?

Yes, international students can study in Russian public schools. However, they may need to go through additional administrative processes, such as providing proof of residency or obtaining a study visa. Public schools in Russia are generally open to all children living in the country, including those from foreign families. Russian language proficiency is often required, as the majority of instruction is in Russian. Some schools, particularly in larger cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg, may offer specialised programs or bilingual classes that accommodate non-native speakers. It's advisable for parents to contact the school directly to understand the specific requirements and support available for international students.

Are Russian diplomas recognised internationally?

Russian diplomas, particularly those from accredited universities and recognised institutions, are generally respected and recognised internationally. However, the recognition of a Russian diploma may depend on the country and the specific field of study. For instance, degrees in engineering, medicine, and the sciences are often highly regarded. Some countries might require additional certification or an equivalency evaluation, especially for professional degrees. It's important for students planning to work or continue their studies abroad to check the specific recognition criteria in the destination country. Many Russian universities have partnerships with foreign institutions, which can also facilitate the international recognition of diplomas.

What languages are taught in Russian schools?

Russian is the primary language of instruction in schools across the country. However, students are typically required to learn at least one foreign language, with English being the most commonly taught. Depending on the school and region, other languages such as German, French, Spanish, or Chinese might also be offered. In regions with significant minority populations, local languages may be included in the curriculum as well. The study of foreign languages usually begins in the primary grades and continues through secondary education. Some specialised schools and private institutions may offer advanced or bilingual language programs to further enhance students' language skills.

Is there support for students learning Russian as a second language?

Yes, many Russian schools provide support for students learning Russian as a second language. This is particularly true in schools with a significant number of international or immigrant students. Support can include additional Russian language classes, specialised teachers who focus on helping non-native speakers, and tailored learning materials. In larger cities, some schools offer bilingual programs or international curricula that accommodate students who are not fluent in Russian. These programs aim to integrate students smoothly into the Russian education system while helping them achieve proficiency in the language. Parents should inquire directly with schools about the specific support services available.

How do Russian schools handle extracurricular activities?