- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 03 January 2014

A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers

- Kathryn Oliver 1 ,

- Simon Innvar 2 ,

- Theo Lorenc 3 ,

- Jenny Woodman 4 &

- James Thomas 5

BMC Health Services Research volume 14 , Article number: 2 ( 2014 ) Cite this article

83k Accesses

783 Citations

376 Altmetric

Metrics details

The gap between research and practice or policy is often described as a problem. To identify new barriers of and facilitators to the use of evidence by policymakers, and assess the state of research in this area, we updated a systematic review.

Systematic review. We searched online databases including Medline, Embase, SocSci Abstracts, CDS, DARE, Psychlit, Cochrane Library, NHSEED, HTA, PAIS, IBSS (Search dates: July 2000 - September 2012). Studies were included if they were primary research or systematic reviews about factors affecting the use of evidence in policy. Studies were coded to extract data on methods, topic, focus, results and population.

145 new studies were identified, of which over half were published after 2010. Thirteen systematic reviews were included. Compared with the original review, a much wider range of policy topics was found. Although still primarily in the health field, studies were also drawn from criminal justice, traffic policy, drug policy, and partnership working. The most frequently reported barriers to evidence uptake were poor access to good quality relevant research, and lack of timely research output. The most frequently reported facilitators were collaboration between researchers and policymakers, and improved relationships and skills. There is an increasing amount of research into new models of knowledge transfer, and evaluations of interventions such as knowledge brokerage.

Conclusions

Timely access to good quality and relevant research evidence, collaborations with policymakers and relationship- and skills-building with policymakers are reported to be the most important factors in influencing the use of evidence. Although investigations into the use of evidence have spread beyond the health field and into more countries, the main barriers and facilitators remained the same as in the earlier review. Few studies provide clear definitions of policy, evidence or policymaker. Nor are empirical data about policy processes or implementation of policy widely available. It is therefore difficult to describe the role of evidence and other factors influencing policy. Future research and policy priorities should aim to illuminate these concepts and processes, target the factors identified in this review, and consider new methods of overcoming the barriers described.

Peer Review reports

Despite an increasing body of research on the uptake and impact of research on policy, and encouragement for policymaking to be evidence-informed [ 1 ], research often struggles to identify a policy audience. The research-policy gap’ is the subject of much commentary and research activity [ 2 – 4 ]. Interventions to bridge this gap are the focus of recent systematic reviews [ 5 – 7 ]. To ensure these interventions are appropriately designed and effective, it is important that they address genuine barriers to research uptake, and utilise facilitators which are likely to affect research uptake.

It is now well recognized that policy is determined as much by the decision-making context (and other influences) as by research evidence [ 8 , 9 ]. Policymakers’ perceptions form an important part of this story, but not the whole. Innvaer [ 10 ] aimed to review studies about the health sector, but the influence of the evidence-based policy movement is now recognized to be important across many policy areas. In the UK, with the creation of Clinical Commissioning Groups, Health and Well-Being Boards, and private providers moving into areas traditionally occupied by the NHS, a broader range of policymakers are becoming potential evidence-users’ than ever. Researchers need to take stock of what we know about evidence-based policy, what we don’t know, and what can be done to assist these users.

The last systematic review looking at policymakers’ perceptions about the barriers to, and facilitators of research use was Innvaer [ 10 ]. The findings from this review were corroborated by later research [ 11 , 12 ], but no systematic update has yet been undertaken. In addition to updating this review in the area of policymakers’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to use of evidence in policy, we also wished to include perceptions from other stakeholder groups than policymakers, such as researchers, managers, and other research users. Furthermore, it may be possible to identify factors affecting research use without relying on the perceptions of research participants – for example, ethnographic studies may produce observational data about knowledge exchange. In addition, we acknowledge that interest in using evidence to inform policy has spread beyond the health sector. Therefore, we aimed to update Innvaer [ 10 ] to include studies identifying all barriers and facilitators of the use of evidence in all policy fields.

This review aimed to update and expand Innvaer [ 10 ], and broaden the scope of the review to:

Identify factors which act as barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence in public policy, including factors perceived by different stakeholder groups.

Describe the focus, methods, populations, and findings of the new evidence in this area.

Because this review has a larger scope that Innvaer [ 10 ], caution must be used in drawing direct comparisons; discussed further in the results.

A protocol for the review was developed and sent to an advisory group of senior academics (available from KO) in order to ensure that the methods and search strategies were exhaustive.

To be included, studies had to be:

Primary research (any study design) or systematic reviews categorising, describing or explaining how evidence is used in policymaking. Intervention studies were included.

About policy (defined as decisions made by a state organisation, or a group of state organisations, at a national, regional or conurbation level). Studies of clinical decision-making for individual patients, or protocols for single clinical sites were excluded.

About barriers or facilitators to the use of evidence (relational, organisational, factors related to researchers, policymakers, policy or research directly, or others).

We did not exclude any studies on the basis of population. These criteria are therefore broader than those for Innvaer [ 10 ] by including all study designs, all populations and all policy areas.

The following electronic databases were searched using adapted search strings from Innvaer [ 10 ] from July 2000 (the cut-off point for the earlier review) - September 2012: Medline, Embase, SocSci Abstracts, CDS, DARE, Psychlit, Cochrane Library, NHSEED, HTA, PAIS, IBSS. Searches combined policy’ terms with utilisation/use’ terms in the first instance. The full search strategy is available from the corresponding author on request; sample search available here (Additional file 1 ). Authors in the field were contacted and key websites were hand-searched. In order to pick up a range of study designs and theoretical papers a methodological filter was not applied.

All studies were screened initially on title and abstract. 100 studies were double screened to ensure consistency, and revisions were made to definitions and criteria accordingly. Relevant studies were retrieved and screened on full text by one reviewer.

Studies were stored, screened and keyworded using the EPPI Reviewer software [ 13 ]. Data were extracted on study characteristics, sampling and recruitment, theoretical framework, methods, and results, with all studies being coded by one reviewer, and two reviewers coding 10-25% each (67 studies were double-coded in total). Because we were not aiming to determine the size of an effect, but instead to describe a body of literature, no risk of bias assessment was made. Quality appraisal in this case would have made no difference to this systematic descriptive synthesis.

Studies were keyworded using a data extraction tool which collected information on study characteristics, topic and focus, and theoretical background. Factors which affected evidence use were coded as barriers or facilitators against a pre-defined list of factors, which was iteratively updated as new factors were identified. All studies were therefore coded at least twice, once with the initial tool, and once with the finalised list of factors.

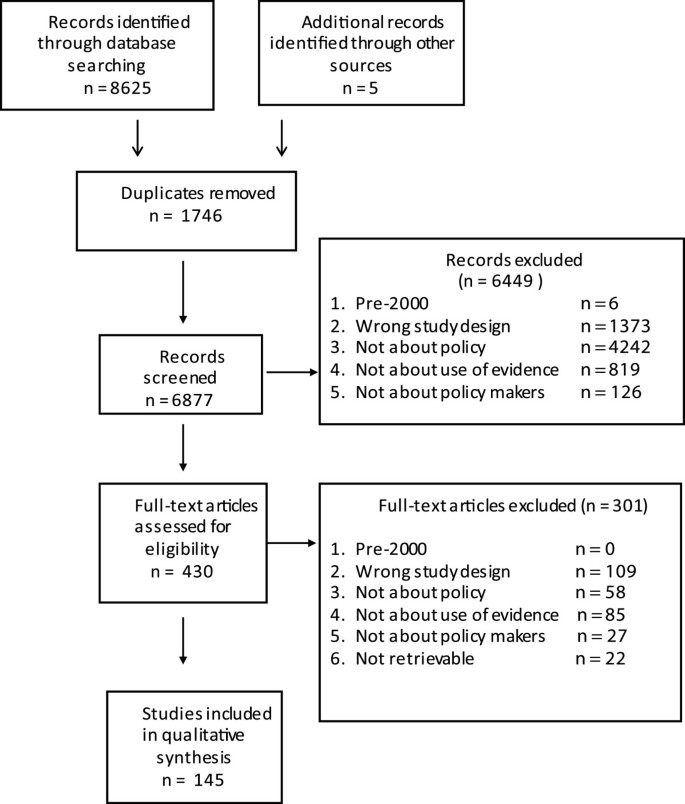

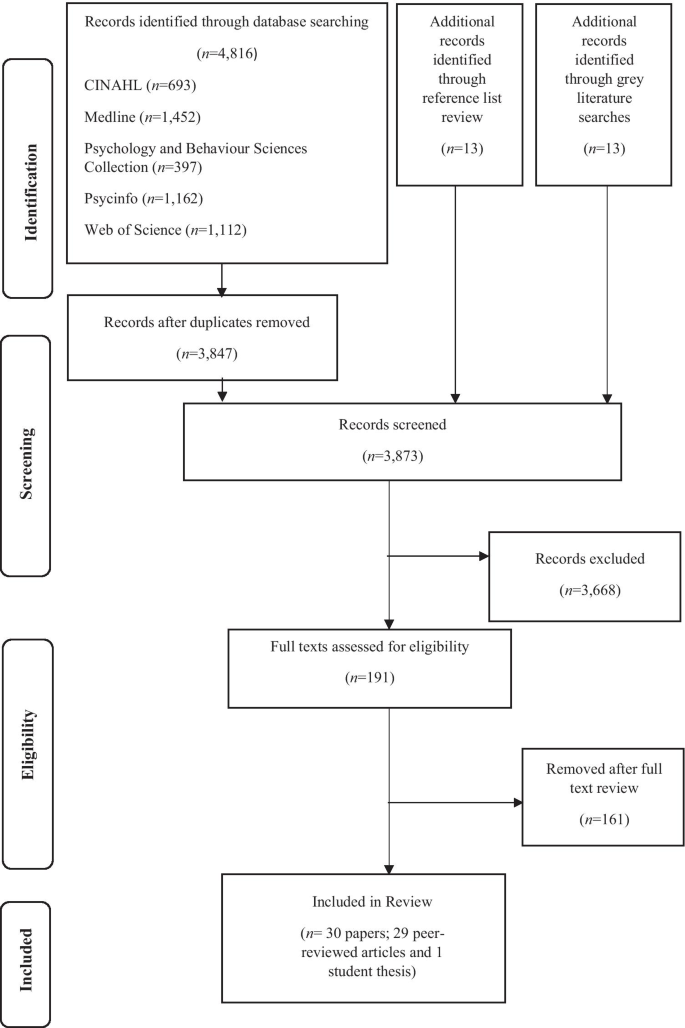

6879 unique records were retrieved, of which 430 were screened on full text. 145 studies were included on full text, of which half were published between September 2010 and September 2012. Figure 1 describes the flow of studies through searching and screening for inclusion.

PRISMA flowchart detailing flow of studies through the review.

Characteristics of included studies

For a full description of the included studies, see Additional file 2 . Studies were undertaken in a wide range of countries (145 studies in over 59 countries,). A significant proportion (n = 33, 23%) were from low- and middle-income countries in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and Central America (n = 32), and several were conducted in Middle-Eastern states (n = 4).

Eleven studies used observational (ethnographic) methods to collect data, and 37 used documentary analysis. However, these represent less than a quarter of included studies, the majority of which were or included semi-structured interviews (n = 79), or included a survey (n = 44). Twelve studies were longitudinal while the rest were cross-sectional. Thirteen systematic reviews and fifty-three case studies were included.

Most studies reported perceptions or experiences of respondents (n = 109; n = 64 respectively), rather than documentary proof or observational results about the use of evidence in policy (n = 14; n = 11 respectively). Evidence’ was defined in 121 studies. Where it was possible to identify what kinds of evidence were being discussed, most focused on the use of research evidence (n = 90) with 33 focusing specifically on systematic reviews. However, 59 studies looked at the use of non-formal evidence, which included local data, surveillance data, personal experience, clinical expertise, or other informal knowledge.

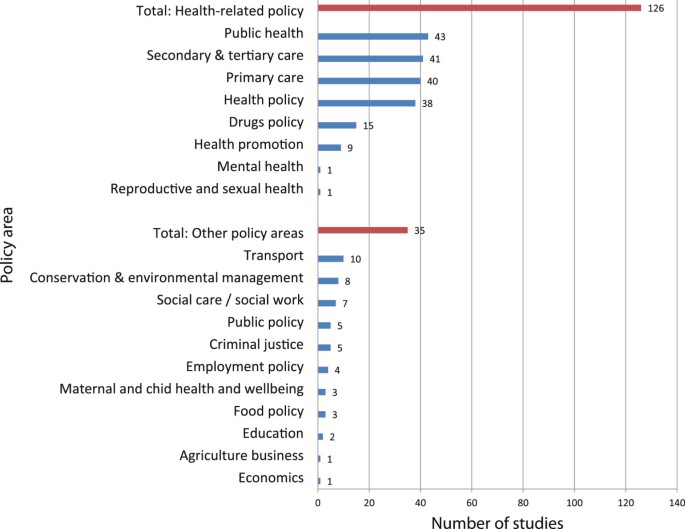

The context of the study was usually non-specific, referring to general policy (n = 84) or practice (n = 37). Changes to specific policy areas or policies were explored in 22 and 14 studies respectively, and information/evidence diffusion in 13. Some studies explicitly set out to look at uptake or adoption of research (n = 41), and others described interventions aiming to increase uptake [ 14 ], or the context after a specific piece of research or policy (such as after the introduction of the 1999 White Paper “Saving Lives: our healthier nation” [ 15 , 16 ]. The vast majority of studies were conducted in health or health-related fields. Most new evidence in the area focused on the health sector, but research was also conducted in areas including traffic [ 17 , 18 ], criminal justice [ 19 – 23 ], drugs policy [ 22 , 24 – 37 ], and environmental conservation [ 20 , 22 , 38 – 42 ] (see Figure 2 ).

Policy focus of study.

Who are these studies written by and for?

137 study reports were written by researchers or people with academic affiliations, with clinical researchers co-authoring a proportion of these (n = 57). Policymakers were credited as authors in 3 studies, [ 25 , 39 , 43 ] and one of those was a governmental report.

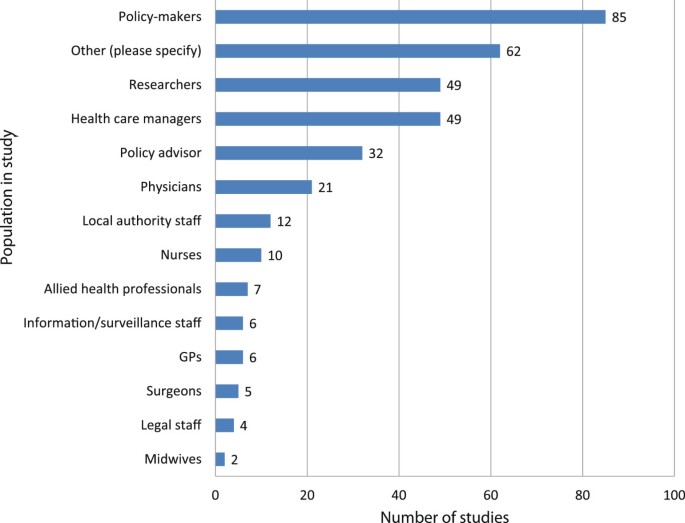

The population samples themselves were predominantly policymakers or advisors (n = 86, n = 32 respectively), health care managers (n = 49), or researchers (49), although many other groups were also included (see Figure 3 ). Where researchers were included in the study population (n = 49), they often outnumbered the policy and practice participants. Other participants included commissioners, health economists, third sector workers, patients, industry and business representatives, and justice and criminal workers. Because it was not always clear who had been involved and what their roles were, it was not possible to give numbers for all these groups. Also included in this other’ category (n = 62) were all documents analysed.

Sample population.

What factors affect use of evidence?

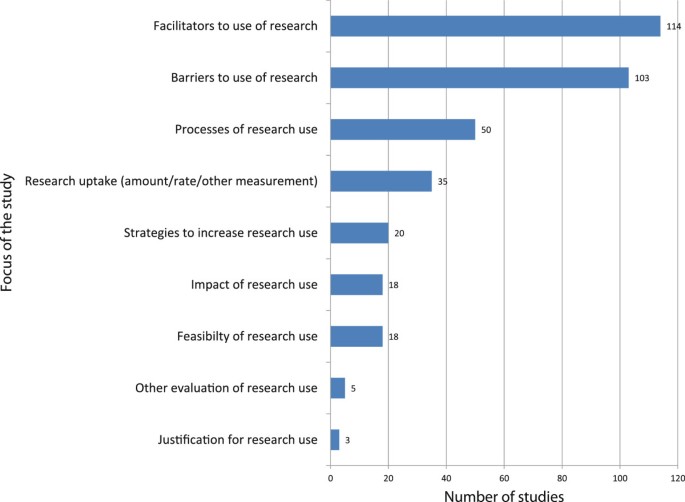

All studies reported either barriers, facilitators, or both, of the use of evidence. Studies also described processes of research use (n = 50), strategies and interventions to increase research use (n = 24), and assessments of the uptake of research (n = 33) (see Figure 4 ).

Main barriers and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers.

Studies reported a range of factors which acted as barriers and/or facilitators of evidence use. The most frequently reported barriers were the lack of availability to research, lack of relevant research, having no time or opportunity to use research evidence, policymakers’ and other users not being skilled in research methods, and costs (see Table 1 ). The most frequently reported facilitators also included access to and improved dissemination of research, and existence of and access to relevant research. Collaboration and relationships between policymakers and research staff were all reported as important factors.

To interpret all the factors reported by included studies, the barriers and facilitators were categorised into themes depending on content: Organisations and resources’ , Contact and collaboration’ , Research and researcher characteristics’ , Policymaker characteristics’ , Policy characteristics’ , and Other’ (see Table 2 ). Below, we describe the main barriers and facilitators reported within each theme, and we give some supplementary information not mentioned in the table.

Contact and relationships

Contact, collaboration and relationships are a major facilitator of evidence use, reported in over two thirds of all studies. Timing and opportunity was the most prominent barrier (n = 42) within this theme. Many studies also discussed the role of relationships, trust, and mutual respect. The serendipitous nature of the policy process was emphasised in some studies, which discussed the role of informal, unplanned contact in policy development and in finding evidence.

Organisations and resources

Organisational factors such as lack of access to research, poor dissemination and costs were highly reported factors affecting the use of research. Other barriers were lack of managerial support, professional bodies, material and personnel resources, managerial will and staff turnover. Professional bodies were seen as barriers where useful guidelines were not available, or where they were perceived to be political or biased. In the case of the WHO, it was seen as unreliable, unsupportive, and with dubious claims to be evidence-based’ [ 31 , 44 ]. Other factors mentioned in connection with organisational and resource barriers included poor long term policy planning [ 45 ], inflexible and non-transparent policy processes [ 46 , 47 ] and in developing countries, lack of effective health care systems [ 24 ]. Leadership and authority were reported as facilitators, with emphasis on community leadership [ 48 ] and policy entrepreneurialism of policy champions [ 43 , 49 ].

Among the facilitators under the theme Organisation and Resources , availability, access and dissemination were considered important facilitators, as was managerial support (n = 22).

Research and researcher characteristics

Characteristics of research evidence were widely reported as factors affecting uptake of research, with clarity, relevance and reliability of research findings reported as important factors. The format of research output was also an important factor in uptake. The importance of the research findings themselves was discussed in 19 studies, usually studies describing the uptake of health inequalities research. The quality and authoritativeness of research was clearly a factor in uptake, particularly where other evidence in the area was poor quality [ 50 ].

Emerging as a new stream of research, eleven studies evaluated or described knowledge broker roles or related concepts [ 6 , 35 , 37 , 51 – 57 ] with dedicated dissemination strategies evaluated in 7 studies and mentioned as a facilitator in 43. Incentives to use evidence and client demand for research evidence were described as facilitators in one study each [ 10 , 58 ].

Researchers themselves were described as factors affecting uptake of their research. Having a good understanding of the policy process and the context surrounding policy priorities was supportive of research uptake [ 17 , 18 , 59 – 61 ]. A barrier to uptake was identified where researchers were described as having different priorities from policymakers, with pressure to publish in peer-reviewed journals [ 27 , 62 , 63 ]. Researchers were valued more when it was clear they were non-partisan and producing unbiased results [ 40 , 57 , 64 ], and provision of expert advice was also reported as helpful.

Policymaker characteristics

Policymakers’ characteristics were also reported to play a role in evidence uptake, with their research skills and awareness (or lack of) reported as a barrier in 34 studies. Some studies reported that policymakers’ beliefs about the utility of evidence-use was a major factor in evidence use (barrier: n = 2, facilitator: n = 3), and, in general, personal experiences, judgments, and values were reported as important factors in whether evidence was used. However, these findings were nearly all (91%) based on studies of perceptions, of which half were perceptions of researchers.

Some studies reported that left-leaning, younger and/or female policymakers were more likely to use research evidence [ 65 , 66 ]. Being more highly educated was reported as a barrier [ 67 ], but there was no consensus about the effect of being clinically trained [ 61 , 68 ].

Policy characteristics

Perhaps surprisingly, legal support and the existence of guidelines for the use of evidence were scarcely reported as factors affecting uptake of evidence. The importance and complexity of the policy area was also discussed, especially in comparison with the relative simplicity of clinical problems.

However, competing pressures (economic, political, social, and cultural factors) were seen to impact on the policy process and hinder the development of evidence-based policy. Political pressures, finances, and competing priorities were all discussed (n = 12), with the media (n = 3) vested interest and pressure/lobby groups (n = 3) and unclear decision-making practices (n = 2) also reported as barriers.

Other factors

One study which studied use of evidence in prisons reported potential security breaches from data loss as a potential barrier to evidence use [ 19 ]. Other studies reported consumer-related barriers (such as issues around privacy and choice [ 49 , 55 , 69 ]), differences between types of policymaker (such as civil servants vs. managers) [ 29 , 70 ] and public opinion. External events were reported as a facilitator in one study. The role of local context, contingency, and serendipity in influencing policy processes and outcomes overall emerged as a theme throughout the results.

Comparing with Innvaer (2002): focus of new evidence in the area

There are differences between the reviews (see Table 3 ), in part reflecting the broader inclusion criteria for this update. However, it is clear that interest in studying the use of evidence has spread beyond the health sector, with more attention from other public policy domains. In addition, there is an increase in publications from low-and middle income countries, where the contexts, barriers and pressures on policymakers in these countries are likely to be very different from those in high-income countries. However, the main research methods used by included studies, and the results generated by those methods, are similar. Despite this increase in research attention, there is still a remarkable dearth of reliable empirical evidence about the actual processes and impacts of research and other evidence use in policy.

This systematic review aimed to identify and describe research about the barriers and facilitators of the use of evidence for policy, expanding on and updating Innvaer [ 10 ]. It found that organisational factors, including availability and access to research were considered to be important influences on whether evidence was used in policy, and the quality of the relationship and collaboration between researchers and policymakers to be the single most mentioned facilitator.

The findings of the updated systematic review presented here were consistent with the original review. We can have a high degree of confidence that it is possible to identify factors likely to influence research uptake, as the expanded field of research synthesised here demonstrates. However, it is less clear what we can learn from this research. For example, there was a high degree of consistency in the findings, even though studies from very different contexts were included. It seems plausible that developing countries would have different barriers from wealthy countries; or that criminal justice would have systematically different pressures from health policy. The similarities reported in these studies may be accounted for by the similarity in approach and methods used. Indeed, the impact and contributions of research to policy (and vice versa) are still unclear, with few studies exploring how, when and why different facilitators and barriers come into play during the policymaking process, or developing an understanding of how research impact on policy and populations might be evaluated. However, there are undoubtedly wider questions about how impact may be defined and measured which are, as yet, unanswered. While perceptions and attitudes are of course important to illuminating the policy process, but there are likely to be other ways - for example documentary, historical, ethnographic or network analyses - in which the role of evidence could be, unpicked [ 71 ].

Over a third of the included studies mentioned use of informal evidence such as local data or tacit knowledge. Researchers are starting to recognize that research evidence is just one source of information for policymakers [ 72 ]. Identifying these sources and types of information are a crucial step in describing and ultimately influencing the policy process. However, most studies do not define what they mean by evidence’, hampering attempts to understand the process. Interventions addressing barriers specifically are unlikely to influence policy without a detailed understanding of all these factors.

Studies in this area continue to be mainly written by and for researchers, with a lack of attention given to the policy process or policymakers’ priorities. Most studies asked researchers about their perspectives. Where mixed populations were included, the researchers often outnumbered the other participants. Involving policymakers in designing and writing a study which looks at these issues in conjunction with barriers and facilitators may be fruitful. Until then, it is hard to defend academics from the charge of misunderstanding policy priorities or processes – a charge first made explicit over 20 years ago [ 73 ].

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The review is exhaustive, and we followed a pre-published protocol and rigorous review methods, including the advice of an advisory group (details available from the corresponding author) (see Additional file 3 for a PRISMA checklist report). However, this paper has only counted the frequencies with which factors are mentioned without any weighting. Without more research, it is difficult to say what impact different factors might have.

Most studies still employ relatively superficial methods such as surveys or short interviews. These were all based on self-reports, however, so given the contentious nature of the topic combined with understandable fear of audit/performance monitoring these results may not be reliable. However, there is some evidence that researchers are employing impact assessment, intervention, or observational studies as well to explore how evidence and policy are related. We were unable to double-screen and double-code all studies due to lack of resources. However, all studies were data-extracted at least twice (once at the beginning, and again with the finalized list of factors which was developed iteratively) so we have confidence in the consistency of approach. No methodological assessment of included studies was undertaken, as this was primarily a descriptive exercise. In addition, the heterogeneity of study designs and the difficulty of comparing quality across these domains limited the usefulness of such an exercise. Quality appraisal would be a valuable step in any in-depth review of a subset of these studies.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Recent systematic reviews in the area have focused on the use of research evidence, [ 74 ] or on the impact of research evidence on policy [ 5 ]. Orton [ 75 ], included in this review, does not include any evaluations of evidence use, ethnographies, or case studies, relying only on self-report questionnaires and interviews to provide the results. Without empirical data exploring access to information and perceived impact [ 74 ], and without investigating the policy process, or testing current theories about knowledge utilization, it is hard to draw useful conclusions. Few studies have systematically appraised the use of evidence in this wider sense.

The reviews all found similar findings with regard to barriers and facilitators of the use of evidence. There still appears to be a need for high-quality, simple, clear and relevant research summaries, to be delivered by known and trusted researchers.

Possible change in future research practice and policymaking

Most studies in this review are descriptive. Because most studies do not go into the content of the facilitators and barriers they identified, we know little about when, why and how the identified barriers and facilitators come into play in the use of evidence in policymaking. Based on this review, future research can use Table 2 to identify themes and factors relevant for their field of research, be it organisations, collaboration, research, researchers, policymakers or policy. Identifying the content and relative importance of these factors and new undiscovered factors in different contexts, at different levels, or in different countries, may contribute to our understanding of evidence use in policy.

One future objective for researchers can be drawn from the results found in Table 1 , namely that four of the five top barriers to the use of evidence is a lack of relevance and importance. If research becomes available, the possibility of increased use improves. If policymakers’ research skills improve, calculations of costs will become more accurate. The natural question is to explore why policymakers do not prioritize overcoming barriers relating to themselves. The barrier called lack of clarity, relevance and reliability of research calls for change in researchers’ objectives and methods, but we need to know what policymakers define as clear, relevant and reliable research, and why and when policymakers will use such research. Of special relevance to this question, is the research on knowledge translation done in the past five to ten years, which formed a new strand of research. This body of work draws on the theory that interpersonal relations are important for knowledge exchange, through employing knowledge brokers or similar. There has also been a growth in resources aimed at helping decision-makers to navigate research evidence, such as Cochrane-produced evidence summaries. These are not only aimed at practitioners within the health field, and the knowledge translation field will hopefully soon make efforts at addressing the broader issues around evidence use in policy more widely to identify underlying mechanisms behind knowledge use.

This review looked for all barriers and facilitators of the used of evidence in policy. Most studies collected research and policy actors’ perceptions about factors affecting the use of research evidence, with a large minority surveying only researchers. Understanding how to alleviate these barriers is hampered by a lack of clarity about how evidence’ is defined by studies, with fewer than half specifying what kinds of information were discussed. Most studies however focused on uptake of research evidence, as opposed to evidence more widely. Research into how to alleviate organisational and resource barriers effectively would be welcomed. Additionally, all such research should be based on an understanding that a broader interpretation of “evidence” than “research-based” evidence is also essential.

Stakeholders perceive relationships to be essential elements of the policy process. However, few studies use dedicated relational methods such as network analysis to study policy communities or the policy process, with a few exceptions [ 75 , 76 ].

Several new strands of research offer encouragement to researchers in the area. Firstly, learning from political sciences and management studies is filtering into the EBP debates, as can be seen from the attention paid to leadership and organisational factors. Research into policy entrepreneurship and knowledge brokerage also formed a significant subset of studies. However, there remains a need for empirical evidence to be generated about the policy process. The barriers and facilitators generated above refer specifically to the use of evidence; however, it is equally possible that similar factors affect the policy process in general (for example, constraints on resources, personnel and costs are likely to affect all policy decisions). Identification and exploration of all factors influencing policy, not just those relating to evidence, should be of interest to researchers; however, this is outside the scope of this review.

Finally, little empirical evidence about the processes or impact of the use of evidence by policy is presented by these studies. Despite the increased amount of research on interventions to increase research use in policy, this is not linked with research about the impact of policy on populations, or of evidence use on population outcomes. Much of the literature is concerned with policymaking; but policymakers’ time is spend on implementation. To justify the continuing rhetoric about the importance of research use, and the ever-increasing amount of research into the area, it is surely essential that we practise what we preach and generate evidence about the process and effectiveness of research use in policy.

“What this paper adds” box

Section 1: what is already known on this subject.

Little is known about the role of research in policymaking. A previous systematic review (Innvaer [ 10 ]) identified the main barriers and facilitators of the use of evidence. Although subsequent reviews have been conducted, they have focused on specific types of evidence, such as economic analyses (Williams) or systematic reviews (Best), or on first-world countries (Orton). Given the explosion of research in the area, an update of the original review was carried out.

Section 2: What this study add

The most often mentioned facilitators of the use of evidence are still reported to be relationships, contact and collaboration, availability and access to research, and relevant, reliable and clear research findings. A lack of relevant, reliable and clear research findings, and poor availability and access to research, are the most often mentioned barriers to policymakers’ use of research.

Research into EBP has spread across a wide range of policy areas and countries, including those from low and middle-income countries. New strands of research focus on knowledge translation, knowledge brokerage, and other interventions to increase uptake of evidence. Little research exists about the process, impact or effectiveness of how, when and why research is used during the policy process.

This study did not require ethics approval.

Data sharing: Full dataset and search strategies are available from Kathryn Oliver at [email protected]. Consent was not obtained as this study had no participants.

Macintyre S, Chalmers I, Horton R, Smith R: Using evidence to inform health policy: case study. BMJ. 2001, 322: 222-225. 10.1136/bmj.322.7280.222.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nutbeam D: Getting evidence into policy and practice to address health inequalities. Health Promot Int. 2004, 19: 137-140.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Oakley A: Evidence-informed policy and practive: challenges for social science. Educational Research and Evidence-Based Practive. Edited by: Hammersley M. 2007, London: SAGE, 91-105.

Google Scholar

Pawson R: Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. 2006, London: Sage Publications Ltd

Book Google Scholar

Boaz A, Baeze J, Fraser A: Effective implementation of research into practice: an overview of systematic reviews of the health literature. BMC Res Notes. 2011, 4.1: 212.

Article Google Scholar

Murthy L, Shepperd S, Clarke M, Garner S, Lavis J, Perrier L, et al: Interventions to improve the use of systematic reviews in decision-making by health system managers, policymakers and clinicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 12: CD009401.

Perrier L, Mrklas K, Lavis J, Straus S: Interventions encouraging the use of systematic reviews by health policymakers and managers: a systematic review. Implementation Sci. 2011, 6: 43-10.1186/1748-5908-6-43.

Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Lemieux-Charles L, Black NA: The impact of context on evidence utilization: a framework for expert groups developing health policy recommendations. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 63: 1811-1824. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.020.

Morrato E, Elias M, Gericke C: Using population-based routine data for evidence-based health policy decisions: lessons from three examples of setting and evaluating national health policy in Australia, the UK and the USA. J Public Health. 2008, 29 (4): 463-471.

Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A: Health policymakers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002, 7: 239-244. 10.1258/135581902320432778.

Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis JL, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E: Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policymaking. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005, 10: 35-48. 10.1258/1355819054308549.

Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson D, O’Flaherty M, Capewell S: The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e21704-10.1371/journal.pone.0021704.

Thomas J, Brunton J: EPPI-Reviewer 3.0: Analysis and Management of Data for Research Synthesis. EPPI-Centre Software. [3.0]. 2006, London: Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, Ref Type: Computer Program

Gagliardi AR, Fraser N, Wright FC, Lemieux-Charles L, Davis D: Fostering knowledge exchange between researchers and decision-makers: exploring the effectiveness of a mixed-methods approach. Health Policy. 2008, 86: 53-63. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.09.002.

Department of Health: Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation. 1999, London: HMSO, Ref Type: Report

Learmonth AM: Utilizing research in practice and generating evidence from practice. Health Educ Res. 2000, 15: 743-756. 10.1093/her/15.6.743.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hinchcliff R, Ivers R, Poulos R, Senserrick T: Utilization of research in policymaking for graduated driver licensing. Am J Public Health. 2010, 100: 2052-2058. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184713.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hinchcliff R, Poulos R, Ivers RQ, Senserrick T: Understanding novice driver policy agenda setting. Public Health. 2011, 125: 217-221. 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.01.001.

Anaraki S, Plugge E: Delivering primary care in prison: the need to improve health information. Inform Prim Care. 2003, 11: 191-194.

PubMed Google Scholar

Bédard P, Ouimet M: Cognizance and consultation of randomized controlled trials among ministerial policy analysts. Rev Policy Res. 2012, 29: 625-644. 10.1111/j.1541-1338.2012.00581.x.

Henderson CE, Young DW, Farrell J, Taxman FS: Associations among state and local organizational contexts: Use of evidence-based practices in the criminal justice system. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009, 103 (Suppl 1): S23-S32.

Jennings ET, Hall JL: Evidence-based practice and the use of information in state agency decision making. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2012, 22: 245-266. 10.1093/jopart/mur040.

Stevens A: Telling policy stories: an ethnographic study of the use of evidence in policymaking in the UK. J Soc Policy. 2011, 40: 237-255. 10.1017/S0047279410000723.

Aaserud M, Lewin S, Innvaer S, Paulsen E, Dahlgren A, Trommald M, et al: Translating research into policy and practice in developing countries: a case study of magnesium sulphate for pre-eclampsia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005, 5: 68-10.1186/1472-6963-5-68.

Albert MA, Fretheim A, Maiga D: Factors influencing the utilization of research findings by health policymakers in a developing country: the selection of Mali’s essential medicines. Health Res Policy Syst. 2007, 5: 2-10.1186/1478-4505-5-2.

Bickford J, Kothari A: Research and knowledge in Ontario tobacco control networks. Canadian J Public Health Rev Can Sante Publique. 2008, 99: 297-300.

Burris H, Parkhurst J, Du-Sarkodie Y, Mayaud P: Getting research into policy - herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2) treatment and HIV infection: international guidelines formulation and the case of Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011, 9 (Suppl 1): S5-10.1186/1478-4505-9-S1-S5.

Currie L, Clancy L: The road to smoke-free legislation in Ireland. [References]. Addiction. 2011, 106: 15-24. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03157.x.

Frey K, Widmer T: Revising swiss policies: the influence of efficiency analyses. Am J Eval. 2011, 32: 494-517. 10.1177/1098214011401902.

Greyson DL, Cunningham C, Morgan S: Information behaviour of Canadian pharmaceutical policymakers. Health Info Libr J. 2012, 29: 16-27. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2011.00969.x.

Hutchinson E, Parkhurst J, Phiri S, Gibb DM, Chishinga N, Droti B, et al: National policy development for cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Malawi, Uganda and Zambia: the relationship between context, evidence and links. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011, 9 (Suppl 1): S6-10.1186/1478-4505-9-S1-S6.

Innvaer S: The use of evidence in public governmental reports on health policy: an analysis of 17 Norwegian official reports (NOU). BMC Health Serv Res. 2009, 9: 177-10.1186/1472-6963-9-177.

Kurko T, Silvast A, Wahlroos H, Pietila K, Airaksinen M: Is pharmaceutical policy evidence-informed? A case of the deregulation process of nicotine replacement therapy products in Finland. Health Policy. 2012, 105: 246-255. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.02.013.

Rieckmann TR, Kovas AE, Cassidy EF, McCarty D: Employing policy and purchasing levers to increase the use of evidence-based practices in community-based substance abuse treatment settings: Reports from single state authorities. Eval Program Plann. 2011, 34: 366-374. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.02.003.

Ritter A: How do drug policymakers access research evidence?. Int J Drug Policy. 2009, 20: 70-75. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.11.017.

Rocchi A, Menon D, Verma S, Miller E: The role of economic evidence in Canadian oncology reimbursement decision-making: to lambda and beyond. Value Health. 2008, 11: 771-783. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00298.x.

Wang A, Baerwaldt T, Kuan R, Nordyke R, Halbert R: Payer perspectives on evidence for formulary decision making in the United States. Value Health. 2011, 14: A350.

Carneiro M, Silva-Rosa T: The use of Scientific Knowledge in the Decision Making Process of Environmental Public Policies in Brazil. 2011, Science Communication: Journal of, 10.

Comptroller and Auditor General of the National Audit Office: Getting the Evidence: Using Research in Policymaking. 2003, London: Stationery Office

Deelstra Y, Nooteboom SG, Kohlmann HR, Berg J, Innanen S: Using knowledge for decision-making purposes in the context of large projects in The Netherlands. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2003, 23: 517-541. 10.1016/S0195-9255(03)00070-2.

Ortega-Argueta A, Baxter G, Hockings M: Compliance of Australian threatened species recovery plans with legislative requirements. J Environ Manage. 2011, 92: 2054-2060. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.03.032.

Weitkamp G, Van den Berg AE, Bregt AK, Van Lammeren RJA: Evaluation by policymakers of a procedure to describe perceived landscape openness. J Environ Manage. 2012, 95: 17-28. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.09.022.

Lomas J, Brown A: Research and advice giving: a functional view of evidence-informed policy advice in a canadian ministry of health. Milbank Q. 2009, 87: 903-926. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00583.x.

Bryce J, Victora C, Habicht J, Vaghan J, Black R: The multi-country evaluation of the integrated management of childhood illness strategy: lessons for the evaluation of public health interventions. Am J Public Health. 2004, 20: 94-105.

Hivon ML: Use of health technology assessment in decision making: coresponsibility of users and producers?. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005, 21: 268-275.

Flitcroft K, Gillespie J, Salkeld G, Carter S, Trevena L: Getting evidence into policy: the need for deliberative strategies?. Soc Sci Med. 2011, 72: 1039-1046. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.034.

Galani C: Self-reported healthcare decision-makers’ attitudes towards economic evaluations of medical technologies. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008, 24: 3049-3058. 10.1185/03007990802442695.

Lencucha R, Kothari AR, Hamel N: Extending collaborations for knowledge translation: lessons from the community-based participatory research literature. Evid Policy. 2010, 6: 75.

Brambila C, Ottolenghi E, Marin C, Bertrand J: Getting results used: evidence from reproductive health programmatic research in Guatemala. Health Policy Plan. 2007, 22: 234-245. 10.1093/heapol/czm013.

Hamel N, Schrecker T: Unpacking capacity to utilize research: a tale of the burkina faso public health association. Soc Sci Med. 2011, 72: 31-38. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.051.

Bunn F: Strategies to promote the impact of systematic reviews on healthcare policy: a systematic review of the literature. Evid Policy. 2011, 7: 428.

Campbell D, Donald B, Moore G, Frew D: Evidence check: knowledge brokering to commission research reviews for policyAN - 857120904; 4175308. Evid Policy. 2011, 7: 97-107. 10.1332/174426411X553034.

Dobbins M, Robeson P, Ciliska D, Hanna S, Cameron R, O’ Mara L, et al: A description of a knowledge broker role implemented as part of a randomized controlled trial evaluating three knowledge translation strategies. Implementation Science. 2009, 4.23: 1-16.

El-Jardali F, Lavis JN, Ataya N, Jamal D: Use of health systems and policy research evidence in the health policymaking in eastern Mediterranean countries: views and practices of researchers. Implementation Science. 2012, 7: 2-10.1186/1748-5908-7-2.

Jack SM: Knowledge transfer and exchange processes for environmental health issues in Canadian Aboriginal communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010, 7: 651-674. 10.3390/ijerph7020651.

Jonsson K: Health systems research in Lao PDR: capacity development for getting research into policy and practice. Health Res Policy Syst. 2007, 5.

Ward V, Smith S, House A, Hamer S: Exploring knowledge exchange: a useful framework for practice and policy. Soc Sci Med. 2012, 74: 297-304. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.021.

Williams I, McIver S, Moore D, Bryan S: The use of economic evaluations in NHS decision-making: a review and empirical investigation. Health Technol Assess. 2008, 12: iii-175.

Friese B, Bogenschneider K: The voice of experience: How social scientists communicate family research to policymakers. Family Relations. 2009, 58: 229-243. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00549.x.

Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Macintyre SJ, Graham H, Egan M: Evidence for public health policy on inequalities: 1: the reality according to policymakers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004, 58: 811-816. 10.1136/jech.2003.015289.

Smith K, Joyce K: Capturing complex realities: understanding efforts to achieve evidence-based policy and practice in public health. Evidence and Policy. 2012, 8: 78.

Bunn F, Kendall S: Does nursing research impact on policy? A case study of health visiting research and UK health policy. [References]. J Res Nurs. 2011, 16: 169-191. 10.1177/1744987110392627.

Hyder AA, Corluka A, Winch PJ, El-Shinnawy A, Ghassany H, Malekafzali H, et al: National policymakers speak out: are researchers giving them what they need?. Health Policy Plan. 2011, 26: 73-82. 10.1093/heapol/czq020.

Hird JA: Policy analysis for what? The effectiveness of nonpartisan policy research organizations. Policy Stud J. 2005, 33: 83-105. 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2005.00093.x.

Olson B, Armstrong EP, Grizzle AJ, Nichter MA: Industry’s perception of presenting pharmacoeconomic models to managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003, 9: 159-167.

Brownson RC, Dodson EA, Stamatakis KA, Casey CM, Elliott MB, Luke DA, et al: Communicating evidence-based information on cancer prevention to state-level policymakers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011, 103: 306-316. 10.1093/jnci/djq529.

Larsen M, Gulis G, Pedersen KM: Use of evidence in local public health work in Denmark. Int J Public Health. 2012, 57: 477-483. 10.1007/s00038-011-0324-y.

Dobbins M, Cockerill R, Barnsley J, Ciliska D: Factors of the innovation, organization, environment, and individual that predict the influence five systematic reviews had on public health decisions. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2001, 17: 467-478.

Jewell CJ, Bero LA: “Developing good taste in evidence”: facilitators of and hindrances to evidence-informed health policymaking in state government. Milbank Q. 2008, 86: 177-208. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00519.x.

McDavid JC, Huse I: Legislator uses of public performance reports: Findings from a five-year study. Am J Eval. 2012, 33: 7-25. 10.1177/1098214011405311.

Wieshaar H, Collin J, Smith K, Gruning T, Mandal S, Gilmore A: Global health governance and the commercial sector: a documentary analysis of tobacco company strategies to influence the WHO framework convention on tobacco control. PLoS Med. 2012, 9: e1001249-10.1371/journal.pmed.1001249.

Haynes AS, Gillespie JA, Derrick GE, Hall WD, Redman S, Chapman S, et al: Galvanizers, guides, champions, and shields: the many ways that policymakers use public health researchers. Milbank Q. 2011, 89: 564-598. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00643.x.

Weiss C: The many meanings of research utilisation. Public Adm Rev. 1979, 39: 426-431. 10.2307/3109916.

Orton L: The Use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e21704-10.1371/journal.pone.0021704.

Lewis JM: Being around and knowing the players: networks of influence in health policy. Soc Sci Med. 2006, 62: 2125-2136. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.10.004.

Oliver K, de Vocht F, Money A, Everett MG: Who runs public health? A mixed-methods study combining network and qualitative analyses. J Public Health. 2013, 35: 453-459. 10.1093/pubmed/fdt039.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/2/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank Frank de Vocht for his comments on the manuscript.

This systematic review was not funded, and no funders had input into design or conduct of the review. KO was part-funded by the EU Commission, under the 7th Framework Programme (200802013 DG Research) as part of the EURO-URHIS 2 project (FP7 HEALTH-2, 223711). Theo Lorenc was funded by the NIHR School for Primary Care, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. We received guidance from an advisory group of academics and practitioners, for which we are grateful.

All authors have access to the data and can take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester, Bridgeford Street, M13 9PL, Manchester, UK

Kathryn Oliver

Faculty of Social Sciences, Oslo University College, P.B. 4, St. Olavs Plass, NO-0130, Oslo, Norway

Simon Innvar

Department of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Public Policy (UCL STEaPP), University College London, 66-72 Gower Street, London, WC1E 6EA, UK

Theo Lorenc

MRC Centre of Epidemiology for Child Health, Institute of Child Health, London, WC1N 1EH, UK

Jenny Woodman

University of London, Institute of Education, 20 Bedford Way, London, WC1H 0AL, UK

James Thomas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kathryn Oliver .

Additional information

Competing interests.

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that none of the authors (KO, SI, TL, JW or JT) have no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. All authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

KO designed the study, carried out the searches, screened and data-extracted studies, and prepared the manuscript. She is the guarantor. SI provided the search strings, data-extracted studies, helped to analyse the data and helped prepare the manuscript. TL data-extracted studies, helped to analyse the data and prepared the manuscript. JW screened studies, helped design the scope and helped prepare the manuscript. JT helped to analyse the data and helped prepare the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: sample search strategy.(docx 11 kb), additional file 2: characteristics of included studies.(docx 203 kb), additional file 3: research checklist.(docx 18 kb), authors’ original submitted files for images.

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, authors’ original file for figure 3, authors’ original file for figure 4, rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Oliver, K., Innvar, S., Lorenc, T. et al. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 14 , 2 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

Download citation

Received : 02 July 2013

Accepted : 20 December 2013

Published : 03 January 2014

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Criminal Justice

- Research Evidence

- Knowledge Translation

- Policy Process

- Policy Area

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 28 June 2022

Rapid systematic review to identify key barriers to access, linkage, and use of local authority administrative data for population health research, practice, and policy in the United Kingdom

- Sowmiya Moorthie 1 , 2 ,

- Shabina Hayat 1 ,

- Yi Zhang 3 ,

- Katherine Parkin 1 , 3 ,

- Veronica Philips 4 ,

- Amber Bale 5 ,

- Robbie Duschinsky 3 ,

- Tamsin Ford 6 &

- Anna Moore 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 1263 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2240 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

Improving data access, sharing, and linkage across local authorities and other agencies can contribute to improvements in population health. Whilst progress is being made to achieve linkage and integration of health and social care data, issues still exist in creating such a system. As part of wider work to create the Cambridge Child Health Informatics and Linked Data (Cam-CHILD) database, we wanted to examine barriers to the access, linkage, and use of local authority data.

A systematic literature search was conducted of scientific databases and the grey literature. Any publications reporting original research related to barriers or enablers of data linkage of or with local authority data in the United Kingdom were included. Barriers relating to the following issues were extracted from each paper: funding, fragmentation, legal and ethical frameworks, cultural issues, geographical boundaries, technical capability, capacity, data quality, security, and patient and public trust.

Twenty eight articles were identified for inclusion in this review. Issues relating to technical capacity and data quality were cited most often. This was followed by those relating to legal and ethical frameworks. Issue relating to public and patient trust were cited the least, however, there is considerable overlap between this topic and issues relating to legal and ethical frameworks.

Conclusions

This rapid review is the first step to an in-depth exploration of the barriers to data access, linkage and use; a better understanding of which can aid in creating and implementing effective solutions. These barriers are not novel although they pose specific challenges in the context of local authority data.

Peer Review reports

Data analysis for improving healthcare is established practice in the United Kingdom (UK). However, the era of big data has led to a greater emphasis on harnessing data from a variety of sources for improved healthcare [ 1 , 2 ]. This means that increasingly efforts are being made in the UK to access, link and use healthcare data from different sources, including general practice, hospitals and community health services. The value of this approach is especially pertinent to addressing complex health issues such as mental health, which are impacted by a wide variety of factors and where service provision may span several agencies (e.g. health and social care) and may be outside of traditional healthcare settings (e.g. third sector, schools or the workplace). Thus, addressing and improving services for those experiencing complex health problems can be better informed by analysis of data from a range of local public services such as education and social care. In the UK, these data usually sit within local authorities (LA) which are local government organisations responsible for public services in particular areas.

Improving data access, linkage and integration across LAs and other agencies can contribute to improvements in population health. Analysis of health datasets that are routinely collected in the course of public service delivery are an important resource for population health and epidemiological research. They can enable research and analysis to better understand social and biological determinants of health, as well as mechanisms to intervene, either through service or policy development [ 3 , 4 ].

National policy prioritises appropriate access to, and use of administrative health and LA data [ 5 , 6 , 7 ], beyond population health management, to patients, service providers, academics, industry, and policy makers [ 8 ]. Such access would optimise health and care outcomes [ 9 ], management of integrated pathways [ 10 ], cost-effectiveness [ 11 ], and service user experience and satisfaction [ 12 , 13 ]. Furthermore, achieving this is particularly important as inequality has widened over the past 10 years in the UK, and accelerated during 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic [ 14 , 15 ]. For health inequalities to be addressed, the Marmot report has recommended the creation of linked administrative databases of health, social care, education, and environmental data that are locally embedded, whole-population, patient-level, granular, and geographically-bound [ 15 ].

Finally, the Health and Social Care Bill currently being passed in England will create Integrated Care System Partnerships (ICSP). The Bill includes a requirement for all ICSPs to develop cross-system intelligence functions to support operational and strategic decision-making, underpinned by linked data and accessible analytical resources [ 16 ]. Thus, building longitudinal, whole-population, patient-level databases linking social, environment, and health information is a priority to better understand, monitor and enable interventions.

The Cambridge Child Health Informatics and Linked Data (Cam-CHILD) database aims to do this for children’s and young people’s health, by building an anonymized, linked database of health, education, social care and genetic data for the population of Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. This database will be utilised to develop informatics-driven approaches to early identification and intervention for mental health problems in children and young people within the region. Our preliminary analyses of the data requirements for model building indicate a prominent requirement for information relating to social and environmental domains. Many of the required variables are located in existing local authority datasets. However, there are significant barriers to access, linkage and use of this data, with few examples of their routine use to support public health decision making, research, or direct patient care [ 17 ].

Understanding the barriers faced in accessing and linking LA data is an important step towards developing solutions to its more efficient use. Thus, the primary aim of this rapid review was to examine reported barriers to the access, linkage and use of such data. A greater understanding of these barriers is important as we embark on the process of bringing together data from a variety of sources. It will also enable others involved in such initiatives, to develop effective and locally driven solutions for use of local authority data.

Search strategy

This review was conducted using systematic review methods and in accordance with the PRISMA statement where possible [ 18 ]. The protocol was registered on PROSPERO ( www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO , CRD42021245528) in April 2021.

A systematic literature search was conducted of the following databases; Medline (via Ovid), Embase (via Ovid), Cochrane Library, Global Health (via EBSCO host), PsycINFO (via EBSCO host), CINAHL (via EBSCO host), and Informit Health Collection in January 2021. Searches were date limited from January 2010 to January 2021, using the search terms listed in Table 1 and tailoring them for each database (detailed search terms in Additional file 1 ). In addition, the PROSPERO registry was searched for newly registered protocols. All results were limited to the UK regions and English language papers.

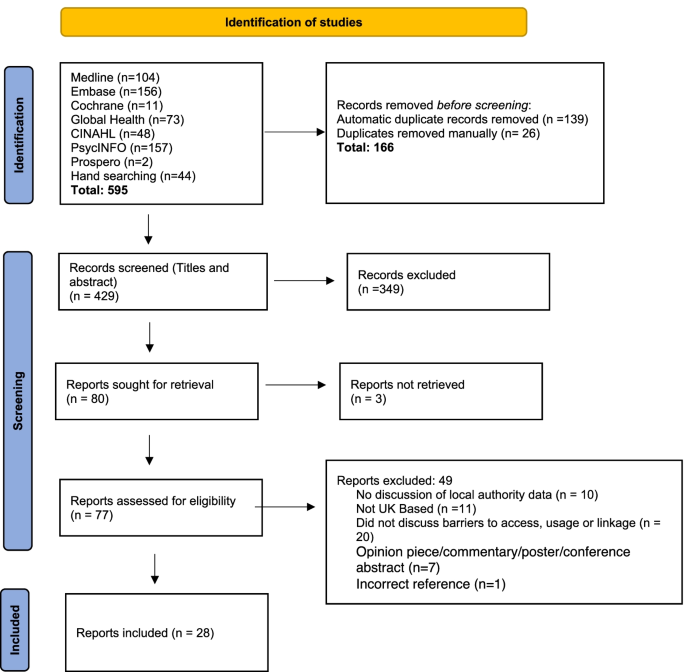

The initial database search revealed 551 records. In addition, 44 papers were identified through other sources (hand-searching references, expert communications and grey literature searches). The grey literature search was conducted using the advanced search function in Google and the search terms listed in Table 1 . The search was customised by restricting to English language pages, in the UK region and in PDF format. Date restrictions were set as for the initial database searches. Potentially relevant records were identified by examining the first five pages of the search results. Following de-duplication, the titles and abstracts of these records were screened by two authors (S.M. and A.M.) separately. Discussion was used to resolve discrepancies and a final list of 81 articles were identified as eligible for full text screening. Fig. 1 shows the search and selection outcomes for each stage of the review process.

PRISMA flow diagram

Given the large proportion of policy papers and grey literature documents, papers were not assessed using traditional quality assurance measures.

Inclusion and data extraction

Five of the authors (S.M., S.H., Y.Z., A.B. and K.P.) assessed full texts of papers for inclusion in the review. Of these papers, 10% ( n = 5) were assessed by all reviewers to ensure a consistent approach to inclusion. Any publications reporting original research related to barriers or enablers of data linkage of or with local authority data in the United Kingdom were included. Research could be either qualitative or quantitative, and from any phase or study design, including grey literature. Publications focused on countries outside the UK, opinion pieces, letters, commentaries and editorials were excluded. Reviewers met regularly to discuss and resolve any uncertainties or disagreements by consensus.

A standardised form was developed for data extraction. Barriers relating to the following issues were extracted from each paper: funding, fragmentation, legal and ethical frameworks, cultural issues, geographical boundaries, technical, capacity, data quality, security, and patient and public trust. These issues were chosen based on our initial scoping work involving preliminary examination of the literature, which indicated these to be the main areas of discussion. Through a more thorough review, our intention was to elicit a more nuanced understanding of how barriers relating to each of these issues were contributing impacting access, linkage and use of LA data. Data on additional issues beyond these was also extracted, if available. For the most part, the issues cited in papers were the same as those identified in our preliminary scoping work. However, we noted that there was considerable inter-relationship and overlap between these issues. Thus, we subsequently collapsed identified barriers into themes to enable better depiction of the main findings. These themes are: technical capability and data quality; legal and ethical frameworks; funding and capacity; cultural factors; data fragmentation plus public and patient trust.

A narrative synthesis approach was taken to data analysis. The extracted data was tabulated under the headings indicated above. The analysis included the extent to which barriers to access, linkage and use of local authority data have been examined, the types of publication reporting on this (e.g. grey literature or peer-reviewed), and the main barriers to access, linkage and use of LA data.

Forty-nine studies were excluded following assessment of full texts. A summary of these articles and reasons for exclusion can be found in Additional file 3 . The lack of information on barriers to access, use or linkage of data was the most frequent reason for exclusion. A total of twenty-eight reports were included in the final review, and Table 2 provides a summary of the characteristics of these reports. Of these, 10 were grey literature and the remainder were academic publications. Most (16 publications) of these covered the entire UK, while 6 focused on Scotland, 1 on Wales, and 5 on England (including 2 on London specifically).

Below we provide a synthesis of our main findings for each grouped theme and Fig. 2 provides a summary of the data that was available relating to each (Additional file 2 has tabulated data). Issues relating to technical capability and data quality were cited most often. This was followed by those relating to legal and ethical frameworks. Issue relating to public and patient trust were cited the least, however, there is considerable overlap between this topic and issues relating to legal and ethical frameworks.

Frequency or reported barriers across citations

Technical capability and data quality issues

Twenty-one papers cited technical constraints in data linkage. These constraints were either due to legacy systems hindering data sharing across organisations, or the absence of secure methods of data transfer, and issues in creating standardised interoperable systems between organisations. The lack of funding and capacity, as discussed further below also influence the ability to create safe, secure and interoperable systems.

Many reports acknowledged the variable quality of data collected by different organisations, [ 5 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 36 ] with the consequences that effective linkage is much harder to achieve [ 38 , 39 ], especially as it is a challenge to understand how data are coded and there is potential for missing or unavailable data [ 20 , 37 ]. Much of local authority data, for example social care data, contain a high proportion of data recorded in an unstructured format [ 38 ]. This serves as an additional challenge to its use, with reports that up to 90% of unstructured data is never analysed [ 21 ]. Standardisation does not address the problem of how to access and use unstructured data.

A few papers explicitly discussed issues relating to bias and inequalities as acting as a barrier to linkage and use of local authority data. These included overrepresentation [ 34 ], as well as underrepresentation of particular groups, for example, women, children, the very elderly, ethnic minorities and those with multiple co-morbidities [ 33 ]. In addition, reports also discussed the potential for explicit consent processes to lead to selection bias [ 3 , 19 ], given differences in which service users are likely to consent to broader use of data [ 19 ].

Legal and ethical frameworks

Both legal frameworks such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and ethical principles govern and impact on data access, linkage and use. Existing legal frameworks are designed to address ethical concerns on data processing and require activities involving data to be ethically reviewed. Thus, it can often be difficult to disentangle ethical and legal frameworks with relation to data protection, leading to discussions on this topic being interconnected. As such, we grouped legal and ethical frameworks together for the purposes of data analysis.

Nineteen records identified existing ethical and legal frameworks as a barrier, particularly the complexity of the regulatory landscape pertaining to data protection. Notable variation in the processes for information governance and ethical approvals used to manage compliance with regulatory frameworks were reported between regions and organisations, with inconsistencies in both interpretation and operationalisation. Contributing to this, were the different legal provisions applying to various categories of public sector data, often including sensitive personal data, which may be identifiable, pseudonymised or anonymous [ 3 , 21 , 22 ]. Each must be considered differently by the law, and thus by information governance and ethics committees. Furthermore, the purpose of initial data collection often differ by team and organisation, limiting the ways in which it can subsequently be used.

Accessing or sharing of data, even between public agencies is a complex process that requires a clear understanding of legal frameworks that govern data access and use. Extending this to sharing between agencies for alternative uses, such as research, requires significant expertise which is often not available within local authorities [ 5 , 30 , 38 ]. Lack of familiarity with frameworks that must be applied to enable inter-agency sharing and use contributes to a risk-averse approach [ 22 , 23 ] and the lack of capacity and resources available hinder problem solving [ 26 ]. Understandable efforts to ensure privacy, confidentiality and consent often leads to hesitancy or concerns by organisation in sharing data [ 3 , 5 , 17 , 19 , 22 ], and where processes were in place, the approval processes, together with the capacity demands within the systems to process these make data access and linkage too time-consuming and resource intensive, and many projects fail [ 28 , 29 , 30 ] or are prevented from even starting [ 3 , 21 ].

Funding and capacity

Seventeen papers discussed issues related to funding either explicitly or indicated that funding posed a barrier. Reports discussed funding for data linkage initiatives, as well as access to research or strategic funding. In particular, within local authorities the need for funding to build capacity was discussed, for example to upskill staff, and build linked data systems and IT infrastructures, as well as to sustain existing systems [ 21 , 30 , 33 , 38 ].

Twelve reports identified capacity constraints stemming from a lack of personnel in government departments with expertise in addressing data access and creating infrastructure for data management. This included the lack of personnel with the expertise to link data within local authorities, and with expertise across sectors, for example health and social care [ 20 , 41 ]. Linkage across sectors can be particularly challenging and time-consuming. It requires time from those with domain-specific knowledge (e.g. social workers), as well as dedicated informatics expertise. Finding sufficient time for frontline staff to contribute to these projects can be challenging, particularly in an already stretched and busy working environment [ 36 , 41 ]. In addition, the report by the Local Government Association in 2019 [ 38 ] noted that building capacity was hindered by funding cuts to local authorities.

From a research perspective, attempts to create linked datasets were hampered by grant deadlines and high costs associated with accessing data as a result of the many different data access agreements and procedures that need to be navigated [ 28 , 35 , 42 ].

Cultural factors

Sixteen papers discussed cultural factors as a barrier to creating and utilising linked datasets. These include both individual and organisational cultural factors that impact on data access for subsequent use in linkage initiatives. Data are often owned by different organisations, which have different cultures in relation to willingness to share, and attitudes to data linkage and sharing which influence the ease of data access and linkage [ 21 , 23 ]. Specifically, willingness to share data, risk aversion and concerns about data breaches were cited as problematic issues [ 3 , 21 , 22 , 28 , 35 , 38 ]. Variation in interpretation of ethical and legal frameworks, as well as the degree of concern about inadvertently going against them impacted on negotiating access to data and in its subsequent linkage and use. The lack of trust between the different parties involved in initiatives to build linked datasets also contributes to issues [ 3 , 21 , 22 , 28 , 29 , 35 , 38 ].

Relatedly, the lack of a clear vision for use of data, not treating it as an asset and lack of leadership within organisations [ 5 , 21 , 26 , 43 , 44 ] also serve to contribute to cultural barriers. This can lead to uncertainty as to what is permissible or desirable by data holders for safe and appropriate use of data.

Data fragmentation

Fourteen papers discussed data fragmentation and data silos as a barrier to linkage and use of data. The variety of data holders and fragmentation across government departments can contribute to delays in access and use of data [ 26 , 28 , 29 , 38 ]. As noted above, cultural factors may influence individual departments’ or organisations’ interpretation of what is permissible or where responsibilities need to be fulfilled to access data. These in turn influence the practicalities of data access such as the requirement for different permissions between and within organisations that need to be granted [ 3 ]. In addition, organisational silos can lead to a lack of understanding of available data across local authorities [ 23 , 43 ].

Related to data fragmentation across data holders, are data silos created by the use of different IT infrastructures within local authorities [ 17 , 21 , 23 , 26 , 33 , 38 ]. The predominance of bespoke and legacy IT systems has led to data being recorded in specific ways, often unique to teams, in a wide range of formats with different coding systems that are not compatible with each other [ 5 , 21 , 23 ]. Furthermore, changes in coding practices within teams or to care processes over time require frequent local system reconfigurations, which are time-consuming and costly [ 24 , 38 ]. This variety in storage formats leads to difficulties with sharing and linkage even between teams within a council, let alone linkage with other external agencies [ 20 ].

Data can also be fragmented across geographical boundaries such as local authorities, counties or countries in the UK. Differences in institutional digital maturity across these boundaries is problematic [ 3 , 21 , 26 , 32 , 38 ]. The report published in 2012 by the Administrative Data Research UK (ADRUK) noted that addressing this in Scotland and Wales had led to significant gains compared to the rest of the UK enabling a county-wide approach to linkage [ 3 ]. Linking between health and social care is significantly more challenging given the minimal use of the National Health Service NHS number within social care across much of England [ 23 , 31 , 38 ]. While there has been significant progress in some areas in the use of the NHS number [ 38 ], this has predominantly involved adult social care data, where sharing has been of basic core information such as demographics, allocated case worker and information about services accessed by individuals. To address this, there are examples of linkage methods that used alternative methods of matching records, for example based on hashed de-identified personal identifiers such as birth date and postcode [ 25 , 28 , 34 , 39 ]. These methods were shown to be effective for a large proportion of records, but require access either to specialist software, or expensive safe havens that provide linkage services. These approaches require orchestrators to navigate the balance between privacy, confidentiality and scalability [ 5 , 17 ], and all are resource intensive in terms of cost and time.

Furthermore, variable digital maturity can also lead to implementation of different ethical and legal frameworks as a means to accommodate this, which in themselves can act as a barrier to data access by creating different processes for applying for use of data. Finally, geographical differences in IT infrastructure risks introducing significant regional inequality, for example in remote areas with poor connectivity [ 32 ].

Lack of patient and public trust

Ten reports identified lack of patient and public trust as a barrier to access, linkage and use of local authority data. These reports discussed several factors that contribute to erosion of public confidence and trust in the use of data for research. These include heightened public understanding of rights to privacy, concerns around misuse and exploitation of data, access to private information by commercial organisations, and limited control over uses of their data. This combined with negative publicity about some government data programmes such as care.data underpinned concerns around data sharing and linkage [ 27 , 33 ]. Furthermore, one report [ 21 ] cited that there can be a lack of public trust in local authorities to efficiently manage and achieve full potential from their data. This is because individuals are required to provide the same information multiple times, and there is a lack of clarity on the purpose of each point of data collection.

Overall, negative publicity around administrative data, local authorities’ inefficiency in data exploitation, lack of transparency, and not obtaining informed consent may all reduce public trust in those handling the data, hence reducing public support for data access, use and linkage and use, acting as a barrier. This in turn can also indirectly influence the willingness and extent to which local authorities engage in data linkage and sharing initiatives.

Over the past 10 years, there has been a policy push in the UK towards digitisation and the more effective use of data across organisations to improve healthcare. Data held outside of the NHS, within other agencies such as local authorities, can provide important information that can be used to improve health. However, it is apparent from the papers we reviewed that whilst there has been much progress made to achieve the ambition of joint-working, significant barriers still exist in accessing, linking and using data across these sectors. Addressing these barriers is now imperative to aid the move towards creating integrated care systems.

The objective of this review was to gain a better understanding of the key barriers to accessing, linking and using local authority data for population health research, practice and policy using a systematic approach. Examination of the reports included in this review led to the identification of barriers which were grouped into key themes. Consideration of these barriers and the themes together, suggests there are a core set of interlinked, cross-cutting factors which impact on the ability to access, link and use local authority data for population health research, practice and policy. These are trust between different stakeholders; leadership to make the best use of data and capacity to deliver on data-led initiatives. Although these are not novel, nor specific to local authorities, their impact on the identified barriers is particular to the context in which LAs function.